Abstract

At the 2017 meeting of the Australian Society for Biophysics, we presented the combined results from two recent studies showing how hydronium ions (H3O+) modulate the structure and ion permeability of phospholipid bilayers. In the first study, the impact of H3O+ on lipid packing had been identified using tethered bilayer lipid membranes in conjunction with electrical impedance spectroscopy and neutron reflectometry. The increased presence of H3O+ (i.e. lower pH) led to a significant reduction in membrane conductivity and increased membrane thickness. A first-order explanation for the effect was assigned to alterations in the steric packing of the membrane lipids. Changes in packing were described by a critical packing parameter (CPP) related to the interfacial area and volume and shape of the membrane lipids. We proposed that increasing the concentraton of H3O+ resulted in stronger hydrogen bonding between the phosphate oxygens at the water–lipid interface leading to a reduced area per lipid and slightly increased membrane thickness. At the meeting, a molecular model for these pH effects based on the result of our second study was presented. Multiple μs-long, unrestrained molecular dynamic (MD) simulations of a phosphatidylcholine lipid bilayer were carried out and showed a concentration dependent reduction in the area per lipid and an increase in bilayer thickness, in agreement with experimental data. Further, H3O+ preferentially accumulated at the water–lipid interface, suggesting the localised pH at the membrane surface is much lower than the bulk bathing solution. Another significant finding was that the hydrogen bonds formed by H3O+ ions with lipid headgroup oxygens are, on average, shorter in length and longer-lived than the ones formed in bulk water. In addition, the H3O+ ions resided for longer periods in association with the carbonyl oxygens than with either phosphate oxygen in lipids. In summary, the MD simulations support a model where the hydrogen bonding capacity of H3O+ for carbonyl and phosphate oxygens is the origin of the pH-induced changes in lipid packing in phospholipid membranes. These molecular-level studies are an important step towards a better understanding of the effect of pH on biological membranes.

Keywords: H3O+, Phospholipid bilayers, Hydrogen bonding, Critical packing parameter, Molecular dynamics simulations

Introduction

How lipid bilayers respond to various external factors such as temperature (Basu et al. 2001; Blicher et al. 2009; Veatch and Keller 2005), pressure (Chen et al. 2011; Winter 2001) and salt concentrations (Aroti et al. 2007; Berkowitz and Vácha 2012; Petrache et al. 2006; Song et al. 2014) has been studied extensively over the past decades. In contrast, the effect of pH on the structure of lipid bilayers has been less examined leading to a poor understanding of this effect at a molecular level. Yet pH-induced changes in membranes play a critical role in many biological processes including the stability and integrity of the lysosomal membranes (Carreira et al. 2017), the formation of cholesterol-enriched domains (Redfern and Gericke 2005) and drug partitioning (Krämer et al. 1998; Schaper et al. 2001). Our understanding of pH on biological membranes is also important to comprehending systemic health issues such as inflammation (Kellum et al. 2004), tumour growth (Gerweck and Seetharaman 1996; Kato et al. 2013), ischaemic stroke (Huang and McNamara 2004) and epileptic seizures (Ziemann et al. 2008). pH also plays an important role in understanding how some organisms have adapted to living in extreme pH environments (de Rosa et al. 1983), in the design of acidophilic bacteria for bio-mining and other biotechnology applications (Khaleque et al. 2017).

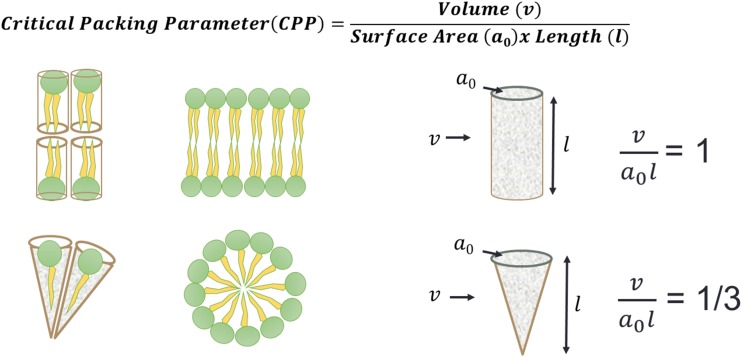

Our previous work explored the effect of the hydronium ion (H3O+) on the lipid packing (Cranfield et al. 2016) in phospholipid bilayers. This work was based on a model proposed by Jacob Israelachvili and colleagues who devised the concept of geometrical constraints that govern the phase behaviour of lipid bilayers and micelles according to a semi-predictive measure called the critical packing parameter (CPP) (Israelachvili et al. 1976). In essence, the geometry of an individual lipid can be described in terms of its volume (v), hydrocarbon–water interfacial area (a0) and chain length (l). When surfactants assemble into a supramolecular phase structure, this geometry dictates that the lipids form a bilayer structure when = 1 and a micelle structure when = 1/3 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The ratio between the lipid volume (v), and the hydrocarbon–water interfacial area (a0) and lipid tail length (l) describes the critical packing parameter (CPP) that dictates the collective properties in the lipid bilayer

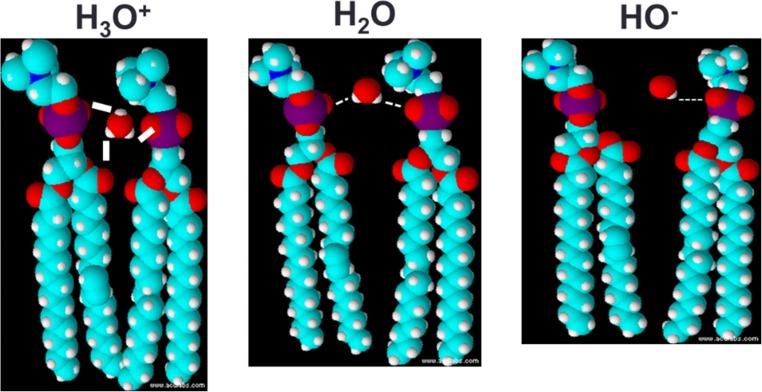

Instead of individual lipids, if the CPP is considered for a lipid bilayer as a whole, then a model can be presented that describes changes in membrane geometry as a result of a weighted CPP (CPPw) (Cranfield et al. 2017). In order for a bilayer structure to be maintained, any changes in the phospholipid headgroup area of the lipids, a0, can be expected to have an effect on the lipid chain length, l, in order that the CPPw maintains a value close to 1. Factors that alter the bridging water molecules between phospholipid headgroups are likely to alter a0. Pearson and Pascher first identified water bridging between phospholipid headgroups via hydrogen bonding in 1979 (Pearson and Pascher 1979). If, instead, there is a greater dissociation of the water molecules such that the local hydronium ion (H3O+) concentration is increased (i.e. the pH is lower), there will be a strengthening of the fleeting hydrogen bonds between the phospholipid phosphates and/or carbonyl groups (Fig. 2) and the overall value for a0 will decrease. In order for a bilayer structure to be maintained (CPPw ~ 1), the lipid tails’ lengths (l) would need to extend.

Fig. 2.

By altering the pH, the strength and number of bridging hydrogen bonds between adjacent lipid headgroups will alter the interfacial surface area of the lipid head groups (a0). The extension of the lipid tails will change as a result (l)

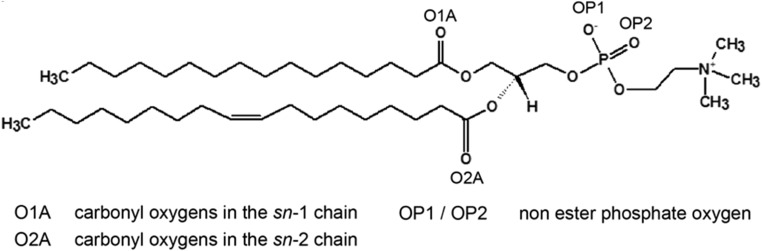

Using tethered bilayer lipid membrane technology in association with electrical impedance spectroscopy and neutron reflectometry, we were able to demonstrate that there is a change in lipid packing as a result of an increase in the concentration of H3O+ and that the membrane thickness did increase marginally, consistent with the change predicted by the CPP model (Cranfield et al. 2016). It was suggested that the variations of water penetration into the bilayer and membrane conductivity observed at low pH were caused by H3O+ ions competing with and disrupting water-bridged intermolecular hydrogen bonds between lipid molecules. It was also hypothesised that the observed decrease in area per lipid was due to an enhanced stability of hydrogen bonds of H3O+ with the phosphate oxygen groups (OP1 and OP2, Fig. 3) and carbonyl oxygens (O1A and O2A) of the sn-1 and sn-2 lipid side chains.

Fig. 3.

Structure of a phospholipid molecule (2-oleoyl-1-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, POPC) showing the hydrogen bonding sites on the carbonyl and phosphate oxygens

To test these hypotheses, we carried out multiple 1-μs-long, unrestrained molecular dynamic (MD) simulations of a fully hydrated POPC (2-oleoyl-1-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) lipid bilayer in the presence of H3O+ ions equivalent to 0.04 M and 0.4 M [H3O+] (three 1-μs simulations of POPC with 0.04 M [H3O+] and 0.4 M [H3O+] each) (Deplazes et al. 2018). At these concentrations, the bulk-phase pH would be equivalent to approximately 1.4 and 0.4, respectively, and thus significantly lower than the pH values used for experiments reported in Cranfield et al., which were carried out at pH 5 (Cranfield et al. 2016). However, a number of experimental and computational studies have suggested that the local concentration of H3O+ ions at the water–lipid interface is significantly higher than that in the bulk water phase (Brändén et al. 2006; Gopta et al. 1999; Heberle et al. 1994; Slevin and Unwin 2000; Mashaghi et al. 2013; Smondyrev and Voth 2002; Wolf et al. 2014; Yamashita and Voth 2010) resulting in differences of up to four pH units.

Simulations were performed using GROMACS version 4.6.7 (Hess et al. 2008), in conjunction with the GROMOS 54A7 force field (Schmid et al. 2011) and parameters for POPC developed by Poger et al. (Poger et al. 2010; Poger and Mark 2009). The hydronium ion was modelled with the excess proton localised on a single water molecule forming a hydronium cation and a geometry similar to that used in previous studies (Bonthuis et al. 2016; Chialvo et al. 2000; Dang 2003; Gertner and Hynes 1998; Kusaka et al. 1998; Urata et al. 2005; Vácha et al. 2007). As a reference, a POPC bilayer simulated in the absence of H3O+ ions from previous studies was used (Poger and Mark 2012; Poger et al. 2010).

Key findings

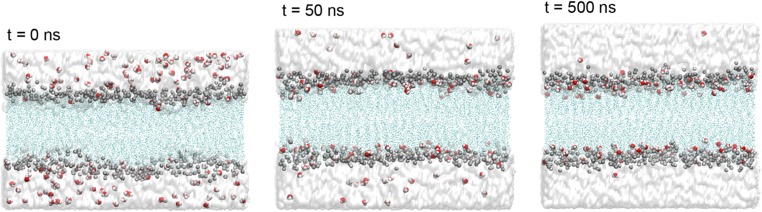

Hydronium ions are attracted to the water–phospholipid interface

The hypothesis that the pH at the water–phospholipid interface is far lower than the bulk solution was supported by the simulations. At the start of the simulations, the H3O+ ions are randomly distributed in the bulk solution. Within the first 100–150 ns of the simulation, the H3O+ migrate to the water–lipid interface. The density profiles obtained from the last 500 ns of the equilibrated systems showed that the H3O+ ions accumulate around the phosphate and carbonyl groups of the phospholipids, as illustrated in Fig. 4. This uneven distribution of H3O+ ions between the water–lipid interface and bulk water means it is not trivial to estimate the ‘actual’ pH in the bathing solution of a membrane. This is further complicated by the existence of layers of ‘interfacial water’ that extend from the lipid headgroup to approximately 1 to 2 nm into bulk water (see reviews by Berkowitz and Vácha 2012; Milhaud 2003; Disalvo 2015 and references therein). Thus, not only is there an uneven distribution of H3O+ ions but the definition of where water can be treated as bulk is hard to define. Analysis of our simulations with 0.4 M [H3O+] suggests that based on the average number of H3O+ ions in bulk (defined as at least 1 nm away from the water–lipid interface), the bulk pH is approximately 2–3 pH units lower than when calculated assuming an even distribution of H3O+ ions in the system.

Fig. 4.

Snapshots from simulations of POPC with 0.4 M [H3O+] illustrating the accumulation of H3O+ ions at the water–lipid interface

Hydronium ions reduce the area per lipid and increase lipid tail length

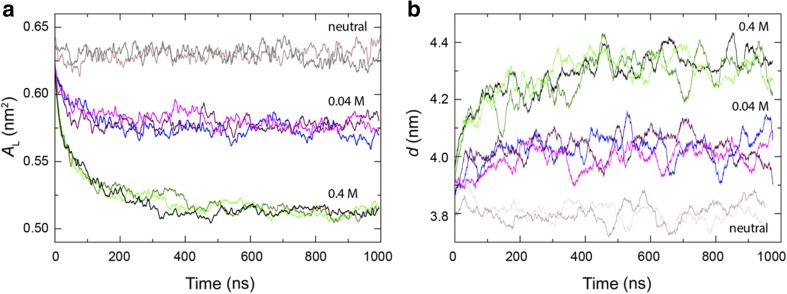

Supporting the data obtained using tethered lipid bilayer membrane technology and neutron diffraction experiments reported previously (Cranfield et al. 2016), the addition of hydronium ions at the interface leads to a reduction in the area per lipid (Fig. 5a) as a result of hydrogen bonding. This is due to the stronger electrostatic interactions of hydroniums compared to water molecules. The CPP model suggests that a reduction in the area per lipid should be accompanied by an increase in the lipid chain length in order to maintain a bilayer structure whereby the CPPw ~ 1. The MD simulations support this CPP model with the overall membrane thickness increasing due to the presence of the hydronium ions (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Area per lipid (AL) and membrane thickness (d) as a function of time from simulations of neutral POPC (grey, brown) and in the presence of 0.04 M [H3O+] (blue, magenta, indigo) and 0.4 M [H3O+] (black, light green, dark green), in agreement with the CPP model and neutron diffraction experiments (Cranfield et al. 2016). Figure reproduced from Deplazes et al. (2018). “The effect of hydronium ions on the structure of phospholipid membranes.” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 20(1): 357–366. Published by the PCCP owner societies

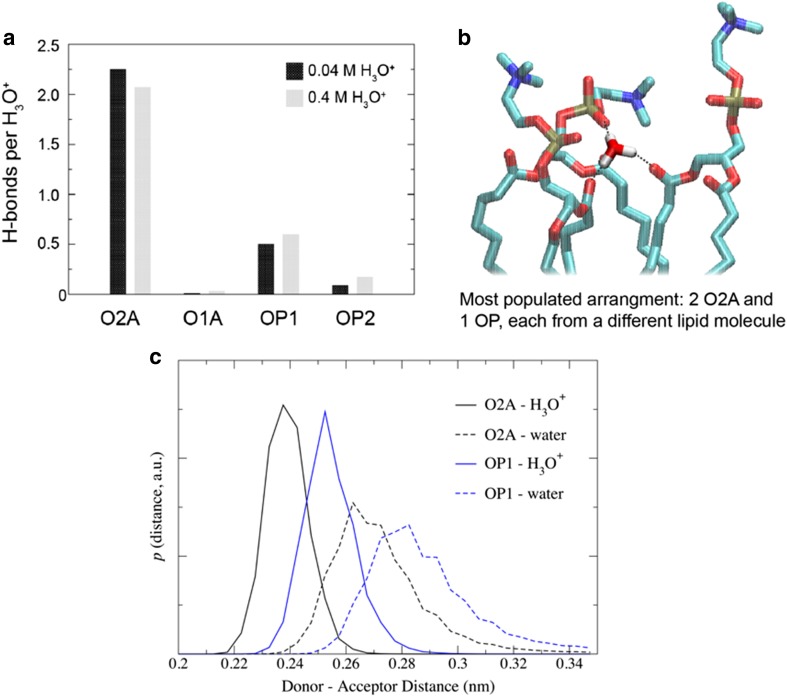

Hydronium ions form strong hydrogen bonds with carbonyl and phosphate lipid oxygens

As illustrated in Fig. 3, POPC has several hydrogen-bonding sites through which it can interact with H3O+. Hydrogen bond analysis from simulations with 0.04 M [H3O+] and 0.4 M [H3O+] showed that the H3O+ ion preferentially interacts with the carbonyl oxygen in the sn-2 chain (O2A), followed by the non-ester phosphate oxygens OP2 and OP1 (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, an analysis of the packing of lipids around the H3O+ ions showed that for the majority of hydrogen bond bridging events, the H3O+ ion is surrounded by two or three lipid molecules. In the most populated arrangement, a H3O+ ion forms hydrogen bonds with the sn-2 carbonyl oxygens (O2A) from two lipids and the non-ester oxygen (OP1) from a third lipid (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, comparison of the distance distributions of the lipid–H3O+ and lipid–water hydrogen bonds showed that the bonds with H3O+ ion are shorter. In addition, estimates of the hydrogen bond lifetimes showed that the lipid–H3O+ bonds are significantly longer-lived than the lipid–water ones.

Fig. 6.

Hydrogen bonding of H3O+ ions. a Histograms of H bonds per H3O+ ions for the different lipid oxygens calculated from simulations of a POPC lipid bilayer in the presence of 0.04 M [H3O+] and 0.4 M [H3O+]. For each oxygen, the number of H bonds was averaged over the last 200 ns of the simulation from the three independent trajectories. b The most common hydrogen bonding networks formed by H3O+ ions and POPC lipids observed in simulations of a POPC lipid bilayer in the presence of 0.04 M [H3O+] and 0.4 M [H3O+] where a H3O+ ion forms hydrogen bonds with two sn-2 carbonyl oxygens (O2A) and one non-ester oxygen (OP1) from three different lipids molecules. Probability distribution of donor–acceptor distances distance for the hydrogen bonds formed by the lipid oxygens O2A and OP1 with the H3O+ ion and water calculated from the last 500 ns of simulations of POPC in the presence of 0.4 M [H3O+]

There are a number of computational and experimental studies that have demonstrated that the structure and dynamics of water at the interface of phospholipid bilayers (and other confined interfaces) deviates from bulk properties (see reviews by Berkowitz and Vácha 2012; Milhaud 2003; Disalvo 2015 and references therein). In addition, our recent work on the analysis of interfacial water suggests that this layer grows thicker in the presence of H3O+ ions (Deplazes et al. 2018, unpublished). Furthermore, not unexpected, the orientation of the water dipoles at the membrane surface is also affected by the H3O+ ions.

Significance

The combined data from the experiments in Cranfield et al. (2016) and Deplazes et al. (2018) provide a molecular-level picture of how the hydrogen bonding network formed by the hydronium ion and surrounding lipids changes the structure of phospholipid membranes. This work also supports the hypothesis that the H3O+ concentration at the lipid–water interface is orders of magnitude lower than that of the bulk electrolyte aqueous solution thus suggesting that the interfacial and bulk pH differ significantly. These findings highlight the significance of the phosphate and carbonyl groups within phospholipids and the mechanisms underlying the sensitivity to hydronium ion concentration in biology. The work also emphasises the importance of understanding the dynamics of water and H3O+ ions at the membrane interface (Gennis 2016; Zhang et al. 2011) and the effect of pH in biological processes in general (Lagadic-Gossman et al. 2004; Krulwich et al. 2011).

Conflict of interest

Evelyne Deplazes declares that she has no conflict of interest. David Poger declares that he has no conflict of interest. Bruce Cornell declares that he has no conflict of interest. Charles G Cranfield declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Aroti A, Leontidis E, Dubois M, Zemb T. Effects of monovalent anions of the hofmeister series on DPPC lipid bilayers part I: swelling and in-plane equations of state. Biophys J. 2007;93:1580–1590. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.094482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu R, De S, Ghosh D, Nandy P. Nonlinear conduction in bilayer lipid membranes – effect of temperature. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 2001;292:146–152. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4371(00)00570-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz ML, Vácha R. Aqueous solutions at the interface with phospholipid bilayers. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:74–82. doi: 10.1021/ar200079x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blicher A, Wodzinska K, Fidorra M, Winterhalter M, Heimburg T. The temperature dependence of lipid membrane permeability, its quantized nature, and the influence of anesthetics. Biophys J. 2009;96:4581–4591. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthuis DJ, Mamatkulov SI, Netz RR. Optimization of classical nonpolarizable force fields for OH− and H3O+ J Chem Phys. 2016;144:104503. doi: 10.1063/1.4942771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brändén M, Sandén T, Brzezinski P, Widengren J. Localized proton microcircuits at the biological membrane–water interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19766–19770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605909103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreira AC, De Almeida RFM, Silva LC. Development of lysosome-mimicking vesicles to study the effect of abnormal accumulation of sphingosine on membrane properties. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3949. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04125-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Poger D, Mark AE. Effect of high pressure on fully hydrated DPPC and POPC bilayers. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:1038–1044. doi: 10.1021/jp110002q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chialvo AA, Cummings PT, Simonson JM. H3O+/Cl− ion-pair formation in high-temperature aqueous solutions. J Chem Phys. 2000;113:8093–8100. doi: 10.1063/1.1314869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cranfield CG, Berry T, Holt SA, Hossain KR, Le Brun AP, Carne S, Al Khamici H, Coster H, Valenzuela SM, Cornell B. Evidence of the key role of H3O+ in phospholipid membrane morphology. Langmuir. 2016;32:10725–10734. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b01988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranfield CG, Henriques ST, Martinac B, Duckworth PA, Craik DJ, Cornell B (2017) Kalata B1 and Kalata B2 have a surfactant-like activity in phosphatidylethanolomine containing lipid membranes. Langmuir [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dang LX. Solvation of the hydronium ion at the water liquid/vapor interface. J Chem Phys. 2003;119:6351–6353. doi: 10.1063/1.1599274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa M, Gambacorta A, Nicolaus B, Grant WD. A C25,C25 diether core lipid from archaebacterial haloalkaliphiles. Microbiology. 1983;129:2333–2337. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-8-2333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deplazes E, Poger D, Cornell B, Cranfield CG. The effect of hydronium ions on the structure of phospholipid membranes. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2018;20:357–366. doi: 10.1039/C7CP06776C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disalvo E. Anibal. Subcellular Biochemistry. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. Membrane Hydration: A Hint to a New Model for Biomembranes; pp. 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennis RB. Proton dynamics at the membrane surface. Biophys J. 2016;110:1909–1911. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertner BJ, Hynes JT. Model molecular dynamics simulation of hydrochloric acid ionization at the surface of stratospheric ice. Faraday Discuss. 1998;110:301–322. doi: 10.1039/a801721b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerweck LE, Seetharaman K. Cellular pH gradient in tumor versus normal tissue: potential exploitation for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1194–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopta OA, Cherepanov DA, Junge W, Mulkidjanian AY. Proton transfer from the bulk to the bound ubiquinone QB of the reaction center in chromatophores of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: retarded conveyance by neutral water. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13159–13164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberle J, Riesle J, Thiedemann G, Oesterhelt D, Dencher NA. Proton migration along the membrane surface and retarded surface to bulk transfer. Nature. 1994;370:379–382. doi: 10.1038/370379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Mcnamara JO. Ischemic stroke. Cell. 2004;118:665–666. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israelachvili JN, Mitchell DJ, Ninham BW. Theory of self-assembly of hydrocarbon amphiphiles into micelles and bilayers. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans. 1976;2(72):1525–1568. doi: 10.1039/f29767201525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Ozawa S, Miyamoto C, Maehata Y, Suzuki A, Maeda T, Baba Y. Acidic extracellular microenvironment and cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:89. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum JA, Song M, Li J. Science review: extracellular acidosis and the immune response: clinical and physiologic implications. Crit Care. 2004;8:331. doi: 10.1186/cc2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaleque HN, Ramsay JP, Murphy RJ, Kaksonen AH, Boxall NJ, Watkin EL. Draft genome sequence of the acidophilic, halotolerant, and iron/sulfur-oxidizing Acidihalobacter prosperus DSM 14174 (strain V6) Genome Announc. 2017;5:e01469–e01416. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01469-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krämer SD, Braun A, Jakits-Deiser C, Wunderli-Allenspach H. Towards the predictability of drug-lipid membrane interactions: the pH-dependent affinity of propranolol to phosphatidylinositol containing liposomes. Pharm Res. 1998;15:739–744. doi: 10.1023/A:1011923103938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krulwich TA, Sachs G, Padan E. Molecular aspects of bacterial pH sensing and homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:330–343. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusaka I, Wang ZG, Seinfeld JH. Binary nucleation of sulfuric acid-water: Monte Carlo simulation. J Chem Phys. 1998;108:6829–6848. doi: 10.1063/1.476097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lagadic-Gossman D, Huc L, Lecureur V. Alterations of intralellular pH homeostastasis in apoptosis: origins and roles. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:953–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashaghi A, Partovi-Azar P, Jadidi T, Anvari M, Jand SP, Nafari N, Tabar MRR, Maass P, Bakker HJ, Bonn M. Enhanced autoionization of water at phospholipid interfaces. J Phys Chem C. 2013;117:510–514. doi: 10.1021/jp3119617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milhaud J. New insights into water-phospholipid model membrane interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1663:19–5.1. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RH, Pascher I. The molecular structure of lecithin dihydrate. Nature. 1979;281:499–501. doi: 10.1038/281499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrache HI, Zemb T, Belloni L, Parsegian VA. Salt screening and specific ion adsorption determine neutral-lipid membrane interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7982–7987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509967103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poger D, Mark AE. On the validation of molecular dynamics simulations of saturated and cis-monounsaturated phosphatidylcholine lipid bilayers: a comparison with experiment. J Chem Theory Comput. 2009;6:325–336. doi: 10.1021/ct900487a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poger D, Mark AE. Lipid bilayers: the effect of force field on ordering and dynamics. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:4807–4817. doi: 10.1021/ct300675z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poger D, van Gunsteren WF, Mark AE. A new force field for simulating phosphatidylcholine bilayers. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:1117–1125. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern DA, Gericke A. pH-dependent domain formation in phosphatidylinositol polyphosphate/phosphatidylcholine mixed vesicles. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:504–515. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400367-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper K-J, Zhang H, Raevsky OA. pH-dependent partitioning of acidic and basic drugs into liposomes—a quantitative structure-activity relationship analysis. Quant Struct-Act Relat. 2001;20:46–54. doi: 10.1002/1521-3838(200105)20:1<46::AID-QSAR46>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid N, Eichenberger AP, Choutko A, Riniker S, Winger M, Mark AE, van Gunsteren WF. Definition and testing of the GROMOS force-field versions 54A7 and 54B7. Eur Biophys J. 2011;40:843–856. doi: 10.1007/s00249-011-0700-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slevin CJ, Unwin PR. Lateral proton diffusion rates along stearic acid monolayers. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:2597–2602. doi: 10.1021/ja993148v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smondyrev AM, Voth GA. Molecular dynamics simulation of proton transport near the surface of a phospholipid membrane. Biophys J. 2002;82:1460–1468. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75500-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Franck J, Pincus P, Kim MW, Han S. Specific ions modulate diffusion dynamics of hydration water on lipid membrane surfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:2642–2649. doi: 10.1021/ja4121692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urata S, Irisawa J, Takada A, Shinoda W, Tsuzuki S, Mikami M. Molecular dynamics simulation of swollen membrane of perfluorinated ionomer. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:4269–4278. doi: 10.1021/jp046434o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vácha R, Buch V, Milet A, Devlin JP, Jungwirth P. Autoionization at the surface of neat water: is the top layer pH neutral, basic, or acidic? Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2007;9:4736–4747. doi: 10.1039/b704491g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veatch SL, Keller SL. Seeing spots: complex phase behavior in simple membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter R. Effects of hydrostatic pressure on lipid and surfactant phases. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;6:303–312. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0294(01)00092-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf MG, Grubmüller H, Groenhof G. Anomalous surface diffusion of protons on lipid membranes. Biophys J. 2014;107:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T, Voth GA. Properties of hydrated excess protons near phospholipid bilayers. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:592–603. doi: 10.1021/jp908768c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Knyazev DG, Vereshaga YA, Ippoliti E, Nguyen TH, Carloni P, Pohl P. Water at hydrophobic interfaces delays proton surface-to-bulk transfer and provides a pathway for lateral proton diffusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;109:9744–9749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121227109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann AE, Schnizler MK, Albert GW, Severson MA, Howard MA, III, Welsh MJ, Wemmie JA. Seizure termination by acidosis depends on ASIC1a. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:816–822. doi: 10.1038/nn.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]