This cohort study investigates trends in patterns of care for low-acuity patients with acute conditions from 2008 to 2015 using data from a large commercial health plan in the United States.

Key Points

Question

How have patterns of care for low-acuity patients with acute conditions changed over time among a commercially insured population?

Findings

In this cohort study of data from a large commercial health plan from 2008 to 2015, emergency department visits per enrollee for the treatment of low-acuity conditions decreased by 36%, whereas utilization of non–emergency department acute care venues increased by 140%. There was a net increase in overall utilization of acute care venues for the treatment of low-acuity conditions and in associated spending.

Meaning

Between 2008 and 2015, there were substantial shifts at which venue Americans received acute care for low-acuity conditions.

Abstract

Importance

Over the past 2 decades, a variety of new care options have emerged for acute care, including urgent care centers, retail clinics, and telemedicine. Trends in the utilization of these newer care venues and the emergency department (ED) have not been characterized.

Objective

To describe trends in visits to different acute care venues, including urgent care centers, retail clinics, telemedicine, and EDs, with a focus on visits for treatment of low-acuity conditions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study used deidentified health plan claims data from Aetna, a large, national, commercial health plan, from January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2015, with approximately 20 million insured members per study year. Descriptive analysis was performed for health plan members younger than 65 years. Data analysis was performed from December 28, 2016, to February 20, 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Utilization, inflation-adjusted price, and spending associated with visits for treatment of low-acuity conditions. Low-acuity conditions were identified using diagnosis codes and included acute respiratory infections, urinary tract infections, rashes, and musculoskeletal strains.

Results

This study included 20.6 million acute care visits for treatment of low-acuity conditions over the 8-year period. Visits to the ED for the treatment of low-acuity conditions decreased by 36% (from 89 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 57 visits per 1000 members in 2015), whereas use of non-ED venues increased by 140% (from 54 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 131 visits per 1000 members in 2015). There was an increase in visits to all non-ED venues: urgent care centers (119% increase, from 47 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 103 visits per 1000 members in 2015), retail clinics (214% increase, from 7 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 22 visits per 1000 members in 2015), and telemedicine (from 0 visits in 2008 to 6 visits per 1000 members in 2015). Utilization and spending per person per year for low-acuity conditions had net increases of 31% (from 143 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 188 visits per 1000 members in 2015) and 14% ($70 per member in 2008 to $80 per member in 2015), respectively. The increase in spending was primarily driven by a 79% increase in price per ED visit for treatment of low-acuity conditions (from $914 per visit in 2008 to $1637 per visit in 2015).

Conclusions and Relevance

From 2008 to 2015, total acute care utilization for the treatment of low-acuity conditions and associated spending per member increased, and utilization of non-ED acute care venues increased rapidly. These findings suggest that patients are more likely to visit urgent care centers than EDs for the treatment of low-acuity conditions.

Introduction

Acute care, treatment for new health problems, can occur by appointment or be unscheduled, and acute care visits comprise over one-third of all ambulatory care delivered in the United States.1,2 Over the past 2 decades, several alternatives to the emergency department (ED) have emerged for acute, unscheduled care. The rapid expansion of urgent care centers, retail clinics, and direct-to-consumer telemedicine may be driven by shifts in patient expectations, poor access to care at traditional physician outpatient practices, and longer wait times and higher costs in the ED.1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11

Despite significant interest in these new non-ED care venues, earlier work has evaluated only selected venues.1,3,4,12,13,14,15,16 There has been no description of overall trends in care patterns for acute, unscheduled care at the population level. In addition, little is known about the association of changes in acute care delivery with patient out-of-pocket costs, price per visit, or spending at the population level. Given the high cost of ED visits and the fact that aggregate spending on emergency care is estimated to be 5% to 10% of national health expenditures, many health plans have created incentives for patients to receive care at non-ED care venues instead of at the ED.17,18,19

We describe trends in the utilization and cost of urgent care centers, retail clinics, telemedicine, and EDs over the 8-year period from 2008 to 2015 using claims data from a large national commercial health plan. We focused on a set of low-acuity conditions that can generally be managed at any of these venues.

Methods

Study Population

We performed descriptive analyses of deidentified claims data from Aetna, a large, national, commercial health plan, from January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2015, with approximately 20 million insured members per study year. The data included basic demographic information, diagnosis and billing codes, place-of-service codes, price, national provider identifiers (NPIs), and tax identification numbers (TINs) for the servicing and billing provider. We included all members 0 to 64 years of age with medical coverage in each year (female sex, 56.0%; mean [SD] age, 29.9 [17.7] years). We excluded members 65 years or older because of concerns regarding concurrent enrollment in Medicare. The study was judged to be exempt from review by the Harvard Medical School Institutional Review Board, Boston, Massachusetts.

Identifying Visits to Acute Care Venues

To identify visits to the relevant care sites, we used a combination of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) place-of-service codes,20 the health plan’s own location variable (ED, inpatient hospital, clinic, office, home, outpatient, or short procedure unit), organizational NPIs, TINs, and Current Procedural Terminology codes.

We classified urgent care center and retail clinic visits as those with CMS place-of-service codes 20 and 17, respectively, or as visits having organizational NPIs and TINs for the top commercial urgent care center and retail clinic operators (a list of these is provided in eAppendix A in the Supplement).21,22 We classified telemedicine visits as those with Current Procedural Terminology code 99444 (e-visits, online evaluation and management by a physician or other qualified health care professional) or with an NPI or TIN for a top telemedicine company (eAppendix A in the Supplement).23 To identify ED visits, we used the health plan–defined location of ED or CMS place-of-service code 23. To ensure that we were not counting multiple claims from the same visit as multiple visits, we only counted 1 visit per patient at a given site of care on a given day. More detailed information on identifying acute care venues is available in the eMethods in the Supplement. We did not include primary care visits in this analysis because the majority of such visits are scheduled and provided for only patients who are established at a practice, and the focus of this study was unscheduled care.1

Low-Acuity Conditions

To assess a more comparable set of visits, we focused on visits for a set of low-acuity conditions, such as bronchitis, urinary tract infection, rash, and muscle strains, that were previously identified as conditions that could be managed at urgent care centers and retail clinics.9,24 Telemedicine providers also manage many of these conditions.25,26,27,28 We acknowledge that not all of these conditions can be managed at all of the care sites; for example, muscle strains are commonly managed at urgent care centers but not at retail clinics. These conditions were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9), and ICD-9 codes were translated into International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes using 2015 General Equivalence Mappings (a list of ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes is provided in eAppendix B in the Supplement).29 In subanalyses, we also examined the overall use of these venues regardless of the types of condition treated.

Patient Characteristics

For each visit, we captured several patient characteristics, including age (stratified as 0-17, 18-44, and 45-64 years), sex, diagnostic cost group risk score, median household income, and rurality. The diagnostic cost group scores were used as a marker of health risk. They are calculated on the basis of ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes and other enrollment and claims data, with higher scores indicating higher predicted spending.30 A concurrent risk score was calculated for each member yearly on the basis of claims from that calendar year. If the member did not have any claims for that year, the score was based on their age and sex, and if the member was not enrolled for the entire year, the score was adjusted according to the eligible period of enrollment. Median household income was determined by zip code from US census data and placed in quartiles based on all enrolled members. Rurality was also assessed by zip code using the 4-tier rural-urban commuting area classification (scheme 1: urban core, suburban, large rural, or small town/rural).31,32

Statistical Analysis

We estimated utilization of urgent care centers, retail clinics, telemedicine, and EDs as visits per 1000 members per calendar year for low-acuity conditions overall and also stratified by age group (0-17, 18-44, and 45-64 years) and diagnostic cost group score (<0.5, 0.5-0.99, 1-3, and >3). We examined the change in the rate of visits for treatment of low-acuity conditions by condition in 2008 vs 2015.

We measured the mean price per visit as the allowed costs for all services at a given site of care on a given day. The allowed cost is the sum of the amount paid by the health plan and by the patient in out-of-pocket costs (coinsurance, co-payment, and deductible). We calculated the mean price per visit by summing all allowed costs. We also measured the average spending per member for each visit for treatment of a low-acuity condition at each venue per year. We adjusted for inflation using consumer price indexes for medical care and report all values in 2015 US dollars. When we calculated utilization and spending for a year, we weighted by member-months of enrollment to address differing lengths of enrollment.

To explore whether the changes in the number of ED visits may be associated with patients seeking care at non-ED acute care venues instead, we used a weighted linear regression model to examine the association between the change in ED use for treatment of low-acuity conditions and the change in use of non-ED venues for treatment of low-acuity conditions across hospital referral regions, using an average of the number of enrollees in 2010 and 2015 in each hospital referral region as a weight. We used member zip codes to assign each visit to 1 of 306 hospital referral regions, which represent regional health care markets for tertiary care as described by the Dartmouth Atlas Project.33 We used 2010 as the baseline year because zip codes were missing in a random fashion for approximately 20% of enrollees in 2008 and 2009.

All analyses were done in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Data were analyzed from December 28, 2016, to February 20, 2018. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Of the 42.8 million acute care visits during the study period, 20.6 million visits (48%) were for low-acuity conditions. Visits associated with low-acuity diagnosis codes accounted for the following percentages of all visits: ED, 38.4% in 2008 and 28.8% in 2015; urgent care center, 71.5% in 2008 and 65.4% in 2015; retail clinic, 61.8% in 2008 and 57.9% in 2015; and telemedicine, 68.7% in 2015 (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Comparison of Patient Characteristics at Different Acute Care Venues

Compared with patients who used the ED, patients who used non-ED acute care venues for treatment of low-acuity conditions were more likely to be female (54.4% vs 58.8%-68.6% of visits across different sites), and this variable did not change significantly during the 8-year study period (Table and eTable 2 in the Supplement). Compared with those who used the ED for treatment of low-acuity conditions, patients who used non-ED acute care venues were more likely to have a lower risk score (lower risk score indicates healthier condition; patients with diagnostic cost group score <0.5, 25.3% for EDs vs 42.6%-47.3% for non-ED acute care venues). Across all venues, the number of patients with diagnostic cost group scores less than 0.5 decreased from 2008 to 2015, and this change was greatest for patients who visited EDs (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Patients who used the ED had lower median household incomes compared with patients who used non-ED acute care venues (patients in lowest quartile of household income, 30.8% for EDs vs 7.1%-20.0% for non-ED acute care venues). Patients with ED and telemedicine visits for low-acuity conditions were more likely to live in rural areas (10.1% and 11.7%, respectively) compared with those who used urgent care centers (5.2%) and retail clinics (2.2%). All differences were statistically significant (P < .001).

Table. Selected Characteristics of US Commercial Health Care Plan Members Younger Than 65 Years Who Sought Treatment for Low-Acuity Conditions, 2015.

| Characteristic | Emergency Department Visits (n = 877 618) | Urgent Care Center Visits (n = 1 580 998) | Retail Clinic Visits (n = 339 040) | Telemedicine Visits (n = 90 849) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 31.0 (18.6) | 31.2 (17.3) | 32.3 (16.1) | 36.5 (15.0) |

| Female sex, % | 54.4 | 58.8 | 64.6 | 68.6 |

| Diagnostic cost group score, %a | ||||

| <0.5 | 25.3 | 43.1 | 47.3 | 42.6 |

| 0.5-0.99 | 20.6 | 22.2 | 21.6 | 21.5 |

| 1-3 | 28.0 | 23.4 | 21.9 | 24.9 |

| >3 | 26.1 | 11.3 | 9.1 | 11.0 |

| Median household income quartile, %b | ||||

| 1 | 30.8 | 20.0 | 12.2 | 7.1 |

| 2 | 25.9 | 26.8 | 20.5 | 28.6 |

| 3 | 22.7 | 28.3 | 30.2 | 21.4 |

| 4 | 20.6 | 24.9 | 37.1 | 42.9 |

| RUCA, % | ||||

| Urban | 81.6 | 87.1 | 91.3 | 76.9 |

| Suburban | 8.2 | 7.7 | 6.5 | 11.4 |

| Large rural | 6.1 | 3.7 | 1.6 | 7.1 |

| Small town/rural | 4.0 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 4.6 |

Abbreviation: RUCA, rural-urban commuting area.

Higher diagnostic cost group score indicates higher health risk and higher predicted spending.

Quartiles derived from median household income for all enrolled members on the basis of zip code from US census data, from 1 (lowest) to 4 (highest).

Trends in Utilization of Acute Care Venues

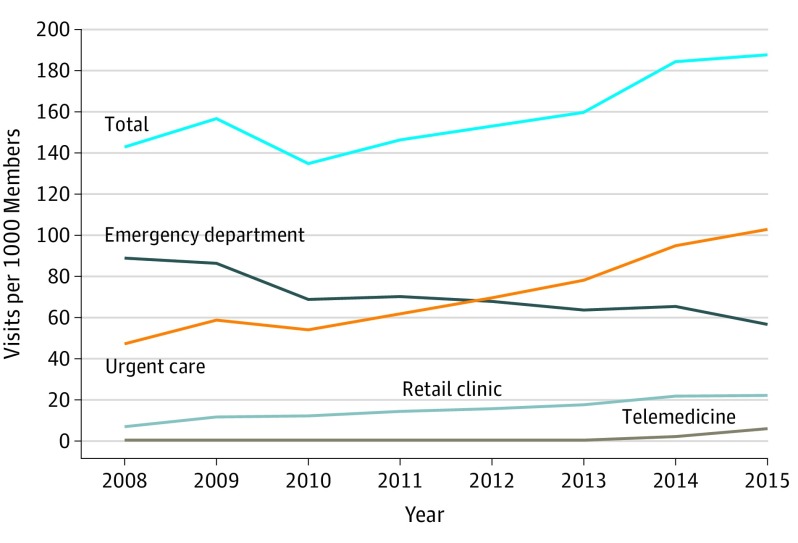

From 2008 to 2015, across all acute care venues, use of acute care venues for treatment of low-acuity conditions increased by 31%, from 143 to 188 visits per 1000 members (Figure 1). In 2009, there was an increase in the use of acute care venues for treatment of low-acuity conditions that corresponded to the timing of the H1N1 influenza pandemic. During the 8-year study period, there was a 140% increase in the use of non-ED acute care venues for the treatment of low-acuity conditions (from 54 to 131 visits per 1000 members). Urgent care centers experienced a 119% increase in visits for the treatment of low-acuity conditions, from 47 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 103 visits per 1000 members in 2015; retail clinics experienced a 214% increase, from 7 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 22 visits per 1000 members in 2015; and telemedicine experienced an increase from 0 visits in 2008 to 6 visits per 1000 members in 2015. In contrast, there was a 36% decrease in ED visits for these conditions (from 89 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 57 visits per 1000 members in 2015). The percentage of all visits associated with treatment of low-acuity conditions that occurred in the ED decreased from 62% in 2008 to 30% in 2015.

Figure 1. Visits to Acute Care Venues for Treatment of Low-Acuity Conditions.

In 2009, there was a large increase in the number of members seeking treatment for influenza and other viral illnesses that corresponded with the H1N1 influenza pandemic.

The number of visits increased for all low-acuity conditions during the study period, with the greatest increase seen among patients with respiratory conditions. The one exception was musculoskeletal conditions, including sprains, contusions, and fractures (eTable 3 and eAppendix B in the Supplement). This overall increase was primarily associated with the increase in utilization of urgent care centers, which have overtaken EDs as the most common treatment venue for most low-acuity conditions according to our data.

Across different age strata (0-17, 18-44, and 45-64 years), there was a similar increase from 2008 to 2015 in visits to urgent care centers and a decrease in visits to EDs for treatment of low-acuity conditions (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Across different risk score strata, the decrease in ED visits associated with low-acuity conditions was greatest among healthier patients (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

In subanalyses that examined all conditions regardless of acuity, overall utilization of acute care venues increased by 30%, from 309 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 401 visits per 1000 members in 2015 (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). There was a substantial increase in utilization of urgent care centers (138% increase; from 66 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 157 visits per 1000 members in 2015), retail clinics (245% increase; from 11 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 38 visits per 1000 members in 2015), and telemedicine (from 0 visits in 2008 to 9 visits per 1000 members in 2015). In contrast, there was a decrease in ED utilization (14% decrease; from 231 visits per 1000 members in 2008 to 198 visits per 1000 members in 2015).

Costs and Spending for Low-Acuity Conditions

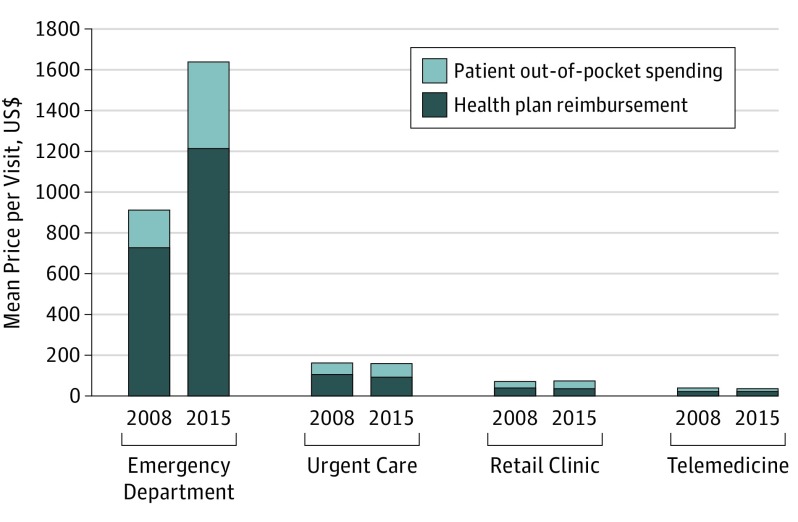

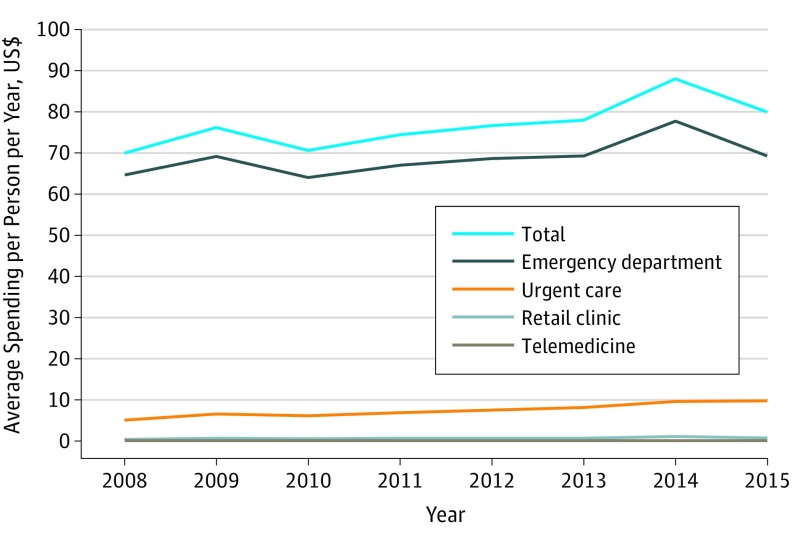

From 2008 to 2015, inflation-adjusted prices per visit for treatment of low-acuity conditions were stable for urgent care centers ($165 per visit in 2008; $162 per visit in 2015), retail clinics ($74 per visit in 2008; $75 per visit in 2015), and telemedicine ($40 per visit in 2008; $39 per visit in 2015) (Figure 2). In contrast, the price per ED visit for treatment of low-acuity conditions increased by 79%, from $914 per visit in 2008 to $1637 per visit in 2015. The increase in price per ED visit was in part associated with a shift toward billing of higher-complexity visits (the fraction of visits billed as highest complexity 99284 or 99285 increased from 26.2% to 39.8% during this period). Out-of-pocket costs for ED visits for treatment of low-acuity conditions increased by 125%, from a mean of $187 per visit in 2008 to $422 per visit in 2015, whereas out-of-pocket costs for urgent care centers ($59 to $66), retail clinics ($34 to $37), and telemedicine ($16 to $14) were nearly unchanged. Average overall spending per member for low-acuity conditions increased by 14% from 2008 to 2015 (from $70 to $80 per member per year) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Mean Price per Visit to an Acute Care Venue for Treatment of Low-Acuity Conditions, 2008 vs 2015.

Spending is adjusted for inflation and represents 2015 US dollars.

Figure 3. Average Spending per Person per Year for Visits to Acute Care Venues for Treatment of Low-Acuity Conditions by Venue.

Spending is adjusted for inflation and represents 2015 US dollars. Spending includes health plan reimbursement and patient out-of-pocket spending.

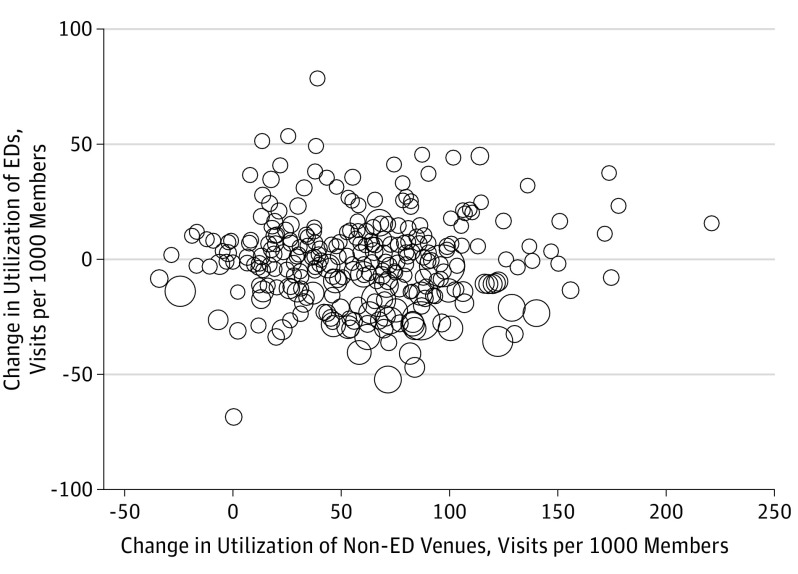

Change in Utilization for ED vs Non-ED Visits Across Geographic Regions

Across hospital referral regions, changes in ED use for the treatment of low-acuity conditions during this period had a small negative association with changes in non-ED use for treatment of low-acuity conditions (β = −0.08; 95% CI, −0.13 to −0.03; P = .004) (Figure 4). Changes in ED use for treatment of low-acuity conditions had a stronger negative association with changes in use of urgent care centers for treatment of low-acuity conditions (β = −0.15; 95% CI, −0.20 to −0.10; P < .001) (eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

Figure 4. Association Between Change in Utilization of Emergency Departments (EDs) vs Non-ED Acute Care Venues for the Treatment of Low-Acuity Conditions by Hospital Referral Region, 2010-2015.

Size of dots corresponds with number of enrollees.

Discussion

From 2008 to 2015, we found substantial shifts in the venues where people received care for low-acuity conditions, with large decreases in ED utilization and a substantial increase in utilization of urgent care centers. Retail clinic and telemedicine utilization also increased substantially during this time, but their use compared with the use of urgent care centers and EDs remained low. Overall, across all acute care venues, the number of visits and spending associated with low-acuity conditions increased by 31% and 14%, respectively.

The observed increase in visits for treatment of low-acuity conditions was primarily associated with an increase in visits to urgent care centers, which are now the acute care site at which low-acuity conditions are most commonly treated. Although other researchers have highlighted the increase in the use of urgent care centers, to our knowledge, our study is the first to characterize trends in utilization.5,6 Possible reasons for this recent increase include an increasing number of clinics, familiarity and acceptance of urgent care centers as credible alternative venues for unscheduled care for acute conditions, the ability of urgent care centers to treat a wider range of conditions than retail clinics or telemedicine, greater convenience with shorter wait times than EDs, and lower out-of-pocket costs for consumers.8,9,10,11 Of note, among a population of patients with commercial insurance, we found that patients with higher incomes were more likely to use non-ED acute care venues, whereas those with lower incomes were more likely to go to the ED. Factors such as transportation and availability of alternative options might influence differences in care patterns.34,35,36

There was a 36% decrease in ED visits per person for treatment of low-acuity conditions and a 14% decrease in overall ED visits. This decrease among those with private insurance is similar to that in a recent government report (which reported a 10% decrease in the number of visits) and a recent industry report (which reported a 2% decrease in the number of visits).16,37 The reasons for decreasing ED use in our study population may overlap with factors driving the popularity of urgent care centers that are discussed above, including increasing out-of-pocket ED costs, inconvenience, and long ED wait times.

The idea of substituting more expensive ED visits with visits to lower-priced non-ED venues has garnered wide interest among health plans and policy makers.19,38,39,40 We found a modest association between decreasing ED use and increasing non-ED use across regions. An earlier study found no association between retail clinic density and ED visit volume overall but a slight association among the privately insured.24 Earlier studies of the association between urgent care center density and ED visit volume produced mixed results: a study of a single urgent care center and a single ED noted a reduction in ED visits, although another study found no association between urgent care center density and ED visit volume.41,42 Our work adds to that literature and indicates that, at a national level, visits to non-ED acute care venues, in particular visits to urgent care centers, may have replaced a small proportion of ED visits. The increase in overall utilization may reflect the woodwork effect—where people who would not otherwise seek care come out of the woodwork to get care—and may indicate that the convenience of these new care venues is associated with increases in the number of patients who seek care.5,25,43

Although more patients are going to lower-priced non-ED venues, spending for low-acuity conditions increased by 14% (from $70 per member in 2008 to $80 per member in 2015). Although the absolute increase of $10 per member is small, this represents an increase of $200 million for the health plan when applied to its 20 million members. We found that the increased spending was primarily associated with an increase in ED prices, which increased by 87% during the study period, whereas prices at non-ED venues for treatment of low-acuity conditions were stable. The magnitude of the increase in ED prices is consistent with that in other work, which has reported an increase in ED prices of 85%.37 Reasons for the rapid increase in ED prices may include treatment of sicker patients; an increase in the provision of high-acuity ED care; upcoding (using a code for a provided service that is higher than what was performed to increase profitability); greater provider consolidation among hospitals as well as among emergency medicine physicians, which facilitates more market power; and greater use of guidelines and protocols that may increase potentially unnecessary testing.44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51

Limitations

Our study has several key limitations. First, we did not include office-based visits. We recognize that a large portion of care for low-acuity conditions occurs during office-based visits, but because physician offices have primarily scheduled visits for established patients in the practice, we chose not to include them in our analysis.1 However, we were not able to account for the small fraction of primary care visits that may be unscheduled. Primary care utilization per capita is decreasing, and this factor could potentially offset some of the overall increase that we found in yearly spending per person for low-acuity conditions.52 Second, our analyses focused only on individuals with private insurance who are younger than 65 years, and trends in use among the uninsured and Medicare and Medicaid populations are different.16,53 Of note, ED use per capita is increasing among the Medicare and Medicaid populations, and these government insurers do not cover care at all non-ED acute care venues.54,55 Third, we may be underestimating the increase in use of urgent care centers and retail clinics because we were not able to identify all of them using our criteria. In our data, we also were not able to distinguish between freestanding EDs and traditional EDs.56 Fourth, our use of diagnosis codes to identify visits for the treatment of low-acuity conditions may not be capturing all such visits because of changes to billing patterns, and some visits that are not truly for the treatment of low-acuity conditions may be misclassified, particularly ED visits.36,57,58 Finally, we focused on utilization and spending and cannot comment on differences in quality of care or patient satisfaction across the different care venues.

Conclusions

During the 8-year period from 2008 to 2015, there were shifts in venues where enrollees of a commercial health plan received acute care for low-acuity conditions. There was a doubling of urgent care center utilization for low-acuity conditions along with a decrease in ED utilization, and urgent care centers provided a majority of on-demand care for low-acuity conditions at the end of the study period. Although utilization of retail clinics and telemedicine increased, these settings continued to represent a low proportion of visits. These findings suggest that visits to non-ED venues may be replacing some ED visits, but overall use of acute care venues for treatment of low-acuity conditions and associated spending continue to increase.

eMethods 1. Identifying visits to acute care venues

eTable 1. Proportion of total visits with low-acuity diagnosis codes by venue, 2008 vs 2015

eTable 2. Selected characteristics of US commercial health care plan members less than 65 years of age who sought treatment for low-acuity conditions, 2008 and 2015

eTable 3. Change in visits per 1000 members by venue and by category of low-acuity condition from 2008 to 2015

eFigure 1. Visits to acute care venues for treatment of low-acuity conditions by age, 2008-2015

eFigure 2. Visits to acute care venues for treatment of low-acuity conditions by diagnostic cost group score, 2008-2015

eFigure 3. Visits to acute care venues for all conditions, 2008-2015

eFigure 4. Association between change in utilization of emergency department (ED) vs urgent care centers for the treatment of low-acuity conditions by hospital referral region, 2010-2015

eAppendix A. Tax identification numbers (TINs) and organizational national provider identifiers (NPIs) for urgent care centers, retail clinics, and telemedicine

eAppendix B. ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for conditions treated in urgent care centers and retail clinics

References

- 1.Pitts SR, Carrier ER, Rich EC, Kellermann AL. Where Americans get acute care: increasingly, it’s not at their doctor’s office. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1620-1629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pines JM, Lotrecchiano GR, Zocchi MS, et al. A conceptual model for episodes of acute, unscheduled care. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(4):484-491.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra A, Lave JR. Visits to retail clinics grew fourfold from 2007 to 2009, although their share of overall outpatient visits remains low. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(9):2123-2129. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashwood JS, Reid RO, Setodji CM, Weber E, Gaynor M, Mehrotra A. Trends in retail clinic use among the commercially insured. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(11):e443-e448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yee T, Lechner AE, Boukus ER. The surge in urgent care centers: emergency department alternative or costly convenience? Res Brief. 2013;(26):1-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinick RM, Betancourt RM. California HealthCare Foundation. No Appointment Needed: The Resurgence of Urgent Care Centers in the United States. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstein RS, Lopez AM, Joseph BA, et al. Telemedicine, telehealth, and mobile health applications that work: opportunities and barriers. Am J Med. 2014;127(3):183-187. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patwardhan A, Davis J, Murphy P, Ryan SF. After-hours access of convenient care clinics and cost savings associated with avoidance of higher-cost sites of care. J Prim Care Community Health. 2012;3(4):243-245. doi: 10.1177/2150131911436251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinick RM, Burns RM, Mehrotra A. Many emergency department visits could be managed at urgent care centers and retail clinics. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1630-1636. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gindi RM, Black LI, Cohen RA. Reasons for emergency room use among U.S. adults aged 18-64: national health interview survey, 2013 and 2014. Natl Health Stat Report. 2016;(90):1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehrotra A. The convenience revolution for treatment of low-acuity conditions. JAMA. 2013;310(1):35-36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blue Cross Blue Shield. Retail clinic visits increase despite use lagging among individually insured Americans. https://www.bcbs.com/the-health-of-america/reports/retail-clinic-visits-increase-despite-use-lagging-among-individually. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- 13.Watts SH, David Bryan E, Tarwater PM. Changes in insurance status and emergency department visits after the 2008 economic downturn. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(1):73-80. doi: 10.1111/acem.12553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimada SL, Hogan TP, Rao SR, et al. Patient-provider secure messaging in VA: variations in adoption and association with urgent care utilization. Med Care. 2013;51(3)(suppl 1):S21-S28. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182780917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997-2007. JAMA. 2010;304(6):664-670. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore BJ, Stocks C, Owens PL Trends in emergency department visits, 2006–2014: statistical brief #227. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb227-Emergency-Department-Visit-Trends.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 17.Lee MH, Schuur JD, Zink BJ. Owning the cost of emergency medicine: beyond 2%. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(5):498-505.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.New England Healthcare Institute A Matter of Urgency: Reducing Emergency Department Overuse. http://www.nehi.net/publications/6-a-matter-of-urgency-reducing-emergency-department-overuse/view. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- 19.Anthem.com. Finding the Right Medical Care When It’s Not an Emergency. https://www.anthem.com/blog/member-news/finding-the-right-care-when-not-an-emergency/. Accessed January 31, 2018.

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Place of Service Code Set. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/coding/place-of-service-codes/place_of_service_code_set.html. Published November 17, 2016. Accessed April 25, 2017.

- 21.Urgent Care Association of America (UCAOA) Industry FAQs. http://www.ucaoa.org/?page=IndustryFAQs&hhSearchTerms=%22faq%22. Accessed June 10, 2017.

- 22.Merchant Medicine The ConvUrgentCare(R) Report, U.S. Walk-In Clinic Market Report: Less Robust but Still Growing; 2017. https://www.merchantmedicine.com/products/. Accessed June 30, 2018.

- 23.Rol J. 17 Best Telemedicine Companies. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/best-telemedicine-companies. Published October 27, 2015. Accessed June 10, 2017.

- 24.Martsolf G, Fingar KR, Coffey R, et al. Association between the opening of retail clinics and low-acuity emergency department visits. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(4):397-403.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashwood JS, Mehrotra A, Cowling D, Uscher-Pines L. Direct-to-consumer telehealth may increase access to care but does not decrease spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(3):485-491. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uscher-Pines L, Mehrotra A. Analysis of Teladoc use seems to indicate expanded access to care for patients without prior connection to a provider. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(2):258-264. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehrotra A, Paone S, Martich GD, Albert SM, Shevchik GJ. Characteristics of patients who seek care via eVisits instead of office visits. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(7):515-519. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2012.0221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albert SM, Shevchik GJ, Paone S, Martich GD. Internet-based medical visit and diagnosis for common medical problems: experience of first user cohort. Telemed J E Health. 2011;17(4):304-308. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CMS.gov 2015-ICD-10-CM-and-GEMs. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/coding/icd10/2015-icd-10-cm-and-gems.html. Published September 29, 2014. Accessed May 2, 2017.

- 30.Ash AS, Ellis RP, Pope GC, et al. Using diagnoses to describe populations and predict costs. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;21(3):7-28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rural Health Data: Washington State Department of Health. https://www.doh.wa.gov/ForPublicHealthandHealthcareProviders/RuralHealth/DataandOtherResources/RuralHealthData. Accessed November 30, 2017.

- 32.Washington State Department of Health Guidelines for Using Rural-Urban Classification Systems for Community Health Assessment. https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/1500/RUCAGuide.pdf. Published October 27, 2016. Accessed November 30, 2017.

- 33.Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Data by Region. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/region/. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 34.Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(7):1196-1203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Billings J, Anderson GM, Newman LS. Recent findings on preventable hospitalizations. Health Aff (Millwood). 1996;15(3):239-249. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.15.3.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uscher-Pines L, Pines J, Kellermann A, Gillen E, Mehrotra A. Deciding to visit the emergency department for non-urgent conditions: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(1):47-59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kennedy K, Hargraves J ER Spending Increased 85%, Driven by Price Increases for the Most Severe Cases (2009-2015). Healthy Bites: Health Care Cost Institute. http://www.healthcostinstitute.org/healthy-bytes/. Published December 4, 2017. Accessed December 5, 2017.

- 38.Diverting Non-Urgent Emergency Room Use Can it Provide Better Care and Lower Costs? Hearing before the Subcommittee on Primary Health and Aging of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions: United States Senate; May 11, 2011. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-112shrg81788/html/CHRG-112shrg81788.htm. Accessed January 31, 2018.

- 39.Reducing Non-Urgent Emergency Services An Innovations Exchange Learning Community. AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange. https://innovations.ahrq.gov/learning-communities/reducing-non-urgent-emergency-services. Accessed January 31, 2018.

- 40.Mann C. Reducing Nonurgent Use of Emergency Departments and Improving Appropriate Care in Appropriate Settings. Center for Medicaid & CHIP Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2014. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib-01-16-14.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2018.

- 41.Merritt B, Naamon E, Morris SA. The influence of an urgent care center on the frequency of ED visits in an urban hospital setting. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18(2):123-125. doi: 10.1016/S0735-6757(00)90000-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alghamdi K, Zocchi M, Frohna WJ, Pines JM. The 2013 dip: factors influencing falling emergency department visits and inpatient admissions in District of Columbia and Maryland. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(6):897-901. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashwood JS, Gaynor M, Setodji CM, Reid RO, Weber E, Mehrotra A. Retail clinic visits for low-acuity conditions increase utilization and spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(3):449-455. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsia RY. Increasing care intensity at emergency department visits in California, 2002–2009. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1811-1819. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunt CS. CPT fee differentials and visit upcoding under Medicare Part B. Health Econ. 2011;20(7):831-841. doi: 10.1002/hec.1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ibrahim AM, Dimick JB, Sinha SS, Hollingsworth JM, Nuliyalu U, Ryan AM. Association of coded severity with readmission reduction after the hospital readmissions reduction program. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):290-292. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murray R. Hospital Charges And The Need For A Maximum Price Obligation Rule For Emergency Department & Out-Of-Network Care. Health Affairs. May 2013. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20130516.031255/full/. Accessed January 17, 2018.

- 48.Kleiner SA, White WD, Lyons S. Market power and provider consolidation in physician markets. Int J Health Econ Manag. 2015;15(1):99-126. doi: 10.1007/s10754-014-9160-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vogt WB, Town R How Has Hospital Consolidation Affected the Price and Quality of Hospital Care? February 2006. https://folio.iupui.edu/handle/10244/520. Accessed February 5, 2018. [PubMed]

- 50.Muhlestein DB, Smith NJ. Physician consolidation: rapid movement from small to large group practices, 2013-15. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1638-1642. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Derlet RW, McNamara RM, Plantz SH, Organ MK, Richards JR. Corporate and hospital profiteering in emergency medicine: problems of the past, present, and future. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(6):902-909. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Health Care Cost Institute. 2016. Health Care Cost and Utilization Report. http://www.healthcostinstitute.org/report/2016-health-care-cost-utilization-report/. Accessed May 4, 2018.

- 53.Hsia RY, Brownell J, Wilson S, Gordon N, Baker LC. Trends in adult emergency department visits in California by insurance status, 2005-2010. JAMA. 2013;310(11):1181-1183. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.228331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rudavsky R, Pollack CE, Mehrotra A. The geographic distribution, ownership, prices, and scope of practice at retail clinics. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(5):315-320. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-5-200909010-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas L, Capistrant G State Telemedicine Gaps Analysis: Coverge & Reimbursement. American Telemedicine Association; 2017. http://www.americantelemed.org/policy-page/state-telemedicine-gaps-reports. Accessed May 4, 2018.

- 56.Sullivan AF, Bachireddy C, Steptoe AP, Oldfield J, Wilson T, Camargo CA Jr. A profile of freestanding emergency departments in the United States, 2007. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(6):1175-1180. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.02.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mistry RD, Brousseau DC, Alessandrini EA. Urgency classification methods for emergency department visits: do they measure up? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(12):870-874. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31818fa79d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raven MC, Lowe RA, Maselli J, Hsia RY. Comparison of presenting complaint vs discharge diagnosis for identifying “nonemergency” emergency department visits. JAMA. 2013;309(11):1145-1153. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Identifying visits to acute care venues

eTable 1. Proportion of total visits with low-acuity diagnosis codes by venue, 2008 vs 2015

eTable 2. Selected characteristics of US commercial health care plan members less than 65 years of age who sought treatment for low-acuity conditions, 2008 and 2015

eTable 3. Change in visits per 1000 members by venue and by category of low-acuity condition from 2008 to 2015

eFigure 1. Visits to acute care venues for treatment of low-acuity conditions by age, 2008-2015

eFigure 2. Visits to acute care venues for treatment of low-acuity conditions by diagnostic cost group score, 2008-2015

eFigure 3. Visits to acute care venues for all conditions, 2008-2015

eFigure 4. Association between change in utilization of emergency department (ED) vs urgent care centers for the treatment of low-acuity conditions by hospital referral region, 2010-2015

eAppendix A. Tax identification numbers (TINs) and organizational national provider identifiers (NPIs) for urgent care centers, retail clinics, and telemedicine

eAppendix B. ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for conditions treated in urgent care centers and retail clinics