Abstract

The expedient assembly of complex, natural product-like small molecules can deliver new chemical entities with the potential to interact with biological systems and inspire the development of new drugs and probes for biology. Diversity-oriented synthesis is a particularly attractive strategy for the delivery of complex molecules in which the 3-dimensional architecture varies across the collection. Here we describe a folding cascade approach to complex polycyclic systems bearing multiple stereocentres mediated by reductive single electron transfer (SET) from SmI2. Simple, linear substrates undergo three different folding pathways triggered by reductive SET. Two of the radical cascade pathways involve the activation and functionalization of otherwise inert secondary alkyl and benzylic groups by 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (HAT). Combination of SmI2, a privileged reagent for cascade reactions, and 1,5-HAT can lead to complexity-generating radical sequences that unlock access to diverse structures not readily accessible by other means.

Diversity-oriented synthesis is a valuable strategy to construct complex molecules of medicinal interest. Here, the authors show a folding cascade strategy to convert linear substrates into polycyclic compounds with multiple stereocentres by combining the reductive chemistry of SmI2 with 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer.

Introduction

The synthesis of complex small molecules that can interact with biological systems is of paramount importance in science. Advances in the field can lead to new therapeutic agents and probes for molecular biology that allow intricate biological processes to be unravelled1,2. Target-oriented synthesis, medicinal and combinatorial chemistry, and diversity-oriented synthesis are the main strategies used to gain access to collections of complex small molecules3. While the first two approaches target defined structure space of known biological relevance, diversity-oriented synthesis attempts to deliver a diverse range of molecular architectures than can give access to unexplored activity and the promise of greater potency4–9. These products often possess unique three-dimensional (3D) shapes10–14 that can enhance their interaction with biological targets, in contrast to more traditional medicinal chemistry scaffolds that are two dimensional15–17.

A main goal of diversity-oriented approaches is to concomitantly access structurally complex molecules and skeletal diversity18. In this regard, cascade processes that convert simple starting materials into complex products, in one pot, are ideal19–22. Furthermore, approaches in which the presence of a particular group in a substrate can direct the reaction down one of several pathways, the so-called substrate-based approaches, are highly desirable tools for accessing skeletal diversity23.

Recent studies in the field of radical chemistry have shown the great potential of open shell intermediates, generated selectively under mild conditions, for use in cascade processes in which complex polycyclic systems bearing multiple stereocentres are formed in a single operation24–26. Of particular interest are radical processes that exploit hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) to functionalise remote, inert C–H bonds27–29. In the context of complexity generation, HAT processes allow radicals to be relocated to sites at which new bond-forming events can take place, thus extending reaction cascades30. While recent reports in the field of diversity-oriented synthesis have utilised radical reactions to access diverse molecular space31–34, the exploitation of HAT in such processes remains largely unexplored.

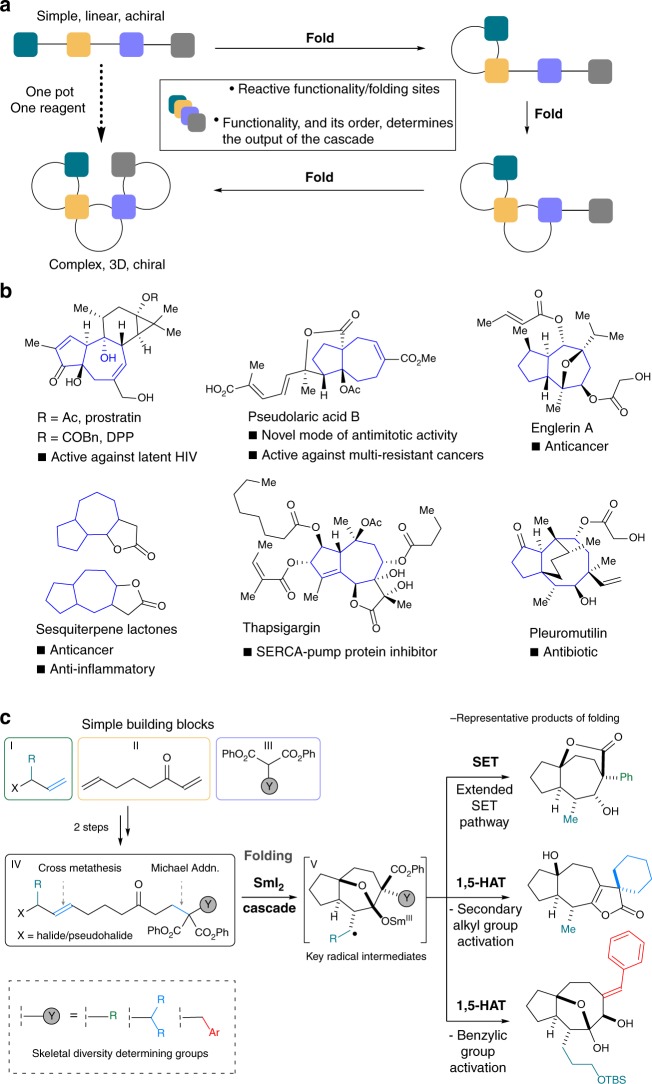

Herein we present a folding cascade approach in which simple, linear starting materials are converted to complex 3D polycyclic architectures through the sequential action of a single reagent on functional groups arranged in the substrate to be folded (Fig. 1a).18–20 In particular, using the reductive single electron transfer (SET) reagent samarium diiodide (SmI2)35–38 in folding cascades, radical (and anionic) character is generated at various points during the one-pot/one-reagent folding process and utilised for selective carbon–carbon bond formation. In our substrate-based approach, skeletal diversity is achieved by the formation of different polycyclic ring systems, quaternary centres, and spirocyclic functionalities, accompanied by the generation of up to five stereocentres. The four distinct scaffolds generated resemble those found in many complex and biologically active natural products (Fig. 1b). The starting materials IV to be folded are typically accessed in modular fashion from terminal alkenes I bearing allylic functionality X, keto diene building block II, and diphenoxy malonates III, in two steps (Michael addition and alkene cross-metathesis). In particular, malonates III contain groups that determine the course of the folding cascades. Depending on the nature of the group Y, key radical intermediates V can follow three distinct pathways to generate four types of complex scaffold. Two of the folding pathways involve 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), an important process that has rarely been exploited in the chemistry of SmI239–41 or in diversity-oriented synthesis (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

A folding cascade approach that delivers polycyclic architectures and the samarium(II) folding cascade approach. The folding cascade approach, examples of biologically active natural products bearing [5,7] and [5,8] fused bicyclic motifs, and a samarium(II)-mediated, one-pot cascade reaction enabling access to these architectures, are shown. a Folding cascade approaches convert simple, linear starting materials to complex 3D polycyclic architectures through the sequential action of a single reagent on functional groups arranged in the substrate to be folded. b Biologically relevant natural products possessing multiple stereocentres and sites of oxygenation, and [5,7] or [5,8] ring systems include prostratin, pseudolaric acid B, englerin A, sesquiterpene lactones such as thapsigargin, and pleuromutilin. c This work involves the development of a one-pot approach to complex polycyclic architectures from simple starting materials. The approach exploits samarium(II) folding cascades featuring 1,5-HAT functionalisation of tertiary and benzylic C–H bonds

Results

Samarium(II) folding cascades involving an extended SET pathway

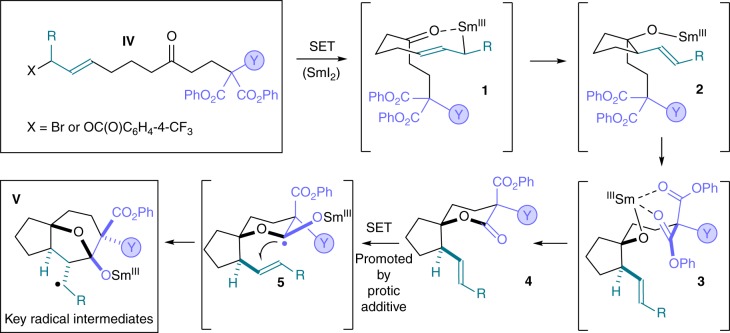

The mechanistic platform upon which our SmI2-mediated folding radical cascades are built involves a Barbier cyclisation–lactonisation–lactone radical cyclisation sequence to generate key radical intermediates V with high diastereocontrol (Fig. 2). Allyl samariums 1 are initially formed by reduction of the allylic halide/pseudohalide moiety (X = Br or OC(O)C6H4-4-CF3) and undergo diastereoselective addition to the ketone carbonyl to give samarium alkoxides 2. Diastereoselective lactonisation via transition structure 3 establishes a α-all-carbon quaternary stereocentre and gives lactones 4. The addition of a protic additive to the reaction vessel activates SmI242,43 and switches on the next stage of the sequence: SET reduction of the lactone carbonyl in 4 gives ketyl radicals 5 and 5-exo-trig radical cyclisation generates the key radicals V44.

Fig. 2.

Mechanistic platform for the radical folding cascades. A mechanism for the common stages of the samarium(II) folding cascades and the formation of the key radical intermediates V is shown. The sequence commences with an intramolecular, samarium(II)-mediated Barbier reaction to give alkoxides 2 which yield 4 after diastereoselective lactonisation. Addition of water then triggers lactone radical cyclisations involving radicals 5

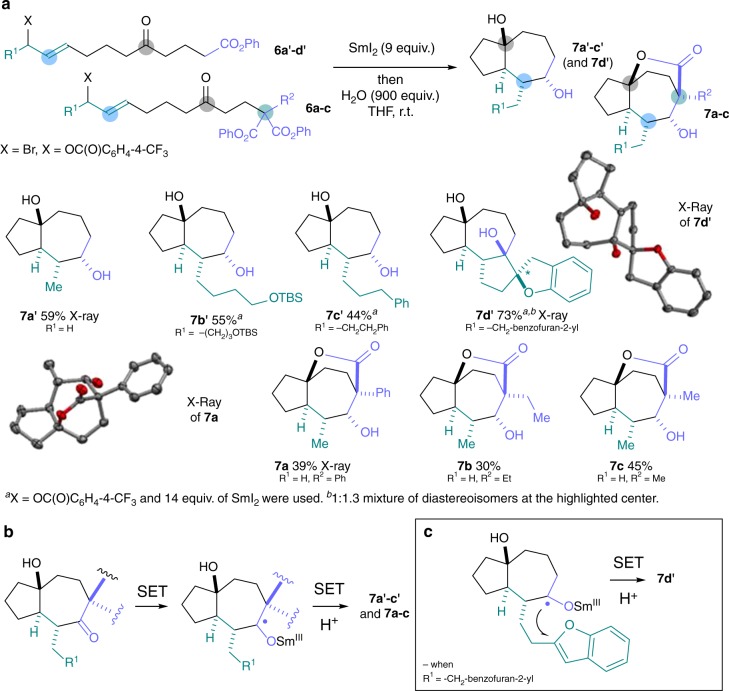

Initially, substrates were designed to follow an extended SET pathway in which radicals V were reduced further and the anions protonated by the H2O additive (Fig. 3a). Subsequent opening of the hemiketal in the products and SET reduction of the resulting ketones gave secondary alcohols 7a’–c’ and 7a–7c from the folding of simple substrates with complete diastereocontrol (Fig. 3b). Alternatively, the ketyl radical intermediates formed in the ketone reduction can be trapped by a pendant heteroarene to forge spirocyclic scaffold 7d’ (Fig. 3c). Notably, linear starting materials 6a–6c, prepared from diphenylmalonate building blocks III, underwent lactonisation in the final stage of the cascade process to deliver bridged lactone products 7a–7c. All products from this extended SET pathway were obtained in moderate to good overall isolated yield (30–73%) and as single diastereoisomers (with the exception of 7d’). Notably, up to 5 contiguous stereocentres and 3 rings are formed in the folding cascades.

Fig. 3.

Folding radical cascades following extended SET pathways. Samarium(II) folding cascades involving an extended SET pathway from key radical intermediates V are shown. a Folding of the substrates 6a’–d’ allowed access to diols 7a’–d’ bearing up to five new stereocentres. The use of malonate-derived substrates 6a–6c allowed the synthesis of complex lactones 7a–7c. b The formation of products involves SET reduction of the carbonyl and diastereoselective protonation to give diols 7a’–c’. In the case of products 7a–c, the alcohol formed in the last step undergoes lactonisation. c The formation of product 7d’ involves a dearomatising radical cyclisation of the samarium(II) ketyl radical intermediate formed upon ketone reduction

Samarium(II) folding cascades involving 1,5-HAT from a secondary centre

To extend the radical cascades and to functionalise otherwise unreactive substrate sites during folding, we sought to relocate the radicals in V using intramolecular HAT, and to trap the new radicals, thus accessing diverse structures. Crucially, HAT processes have little precedent in the chemistry of SmI2 as radical intermediates are typically reduced rapidly to the corresponding carbanions45. We reasoned that careful substrate design could lead to radical intermediates V in which the radical centre was sufficiently close to the site of abstraction for the rate of 1,5-HAT to outcompete the usual radical reduction and protonation that dominates SmI2 chemistry. The proposed 1,5-HAT pathway was explored using malonate components III bearing secondary alkyl groups possessing tertiary C–H bonds β- to the ester carbonyls. Pleasingly, simple substrates 6d–j underwent radical folding cascades to give complex tricyclic lactones 7d–j in good overall yield and as single diastereoisomers (Fig. 4a). Notably, malonate substrates 6e–h containing carbo- and heterocyclic motifs, conveniently introduced using a suitably substituted malonate component III, delivered lactone products bearing carbo- and hetero-spirocyclic rings 7e–h.

Fig. 4.

Folding radical cascades involving 1,5-HAT and activation of a secondary alkyl group. A samarium(II) folding cascade involving 1,5-HAT activation of secondary alkyl groups in key radical intermediates V is shown. a Scope of the samarium(II) folding cascade involving activation of a secondary alkyl group by 1,5-HAT to give products 7d–j. b The mechanism of folding involves 1,5-HAT in key radical intermediates V to give 9. A 1,2-ester shift then generates radical intermediates 10 that, after hemiketal opening and SET reduction, give samarium(III) enolates 12. The final products 7d–j are obtained by lactonisation of enolates 12

The mechanism of the folding cascades involving 1,5-HAT from a secondary alkyl group is shown in Fig. 4b. After the initial Barbier cyclisation – lactonisation – lactone cyclisation sequence (see Fig. 2), 1,5-HAT in radical 8 activates the secondary alkyl group in the malonate unit and radicals 9 are formed. Crucially, reduction of tertiary radicals 9 to the corresponding anions is slower than intramolecular radical addition and the radicals undergo 1,2-migration of the ester group46 to give stabilised radicals 11 after hemiketal collapse. Subsequent SET gives samarium enolates 1247 that undergo lactonisation. As proposed, the facile nature of the 1,5-HAT process, relative to reduction of 8 to the corresponding anions, is likely the result of the proximity of the radicals in V, formed from the diastereoselective lactonisation–lactone cyclisation sequence, to the alkyl sidechain located α to the ester (Fig. 4b).

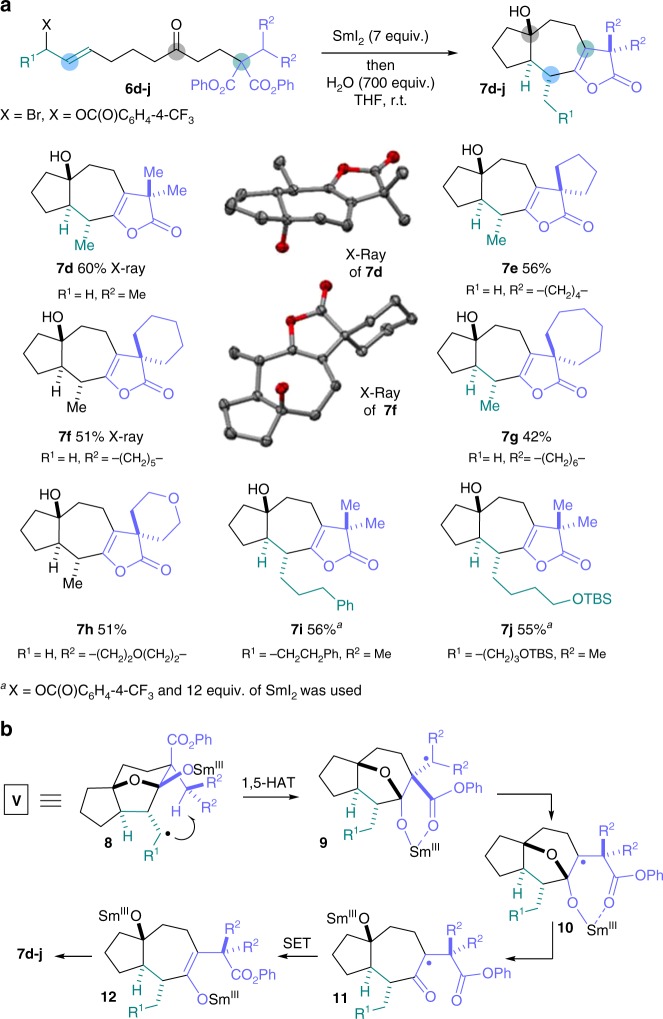

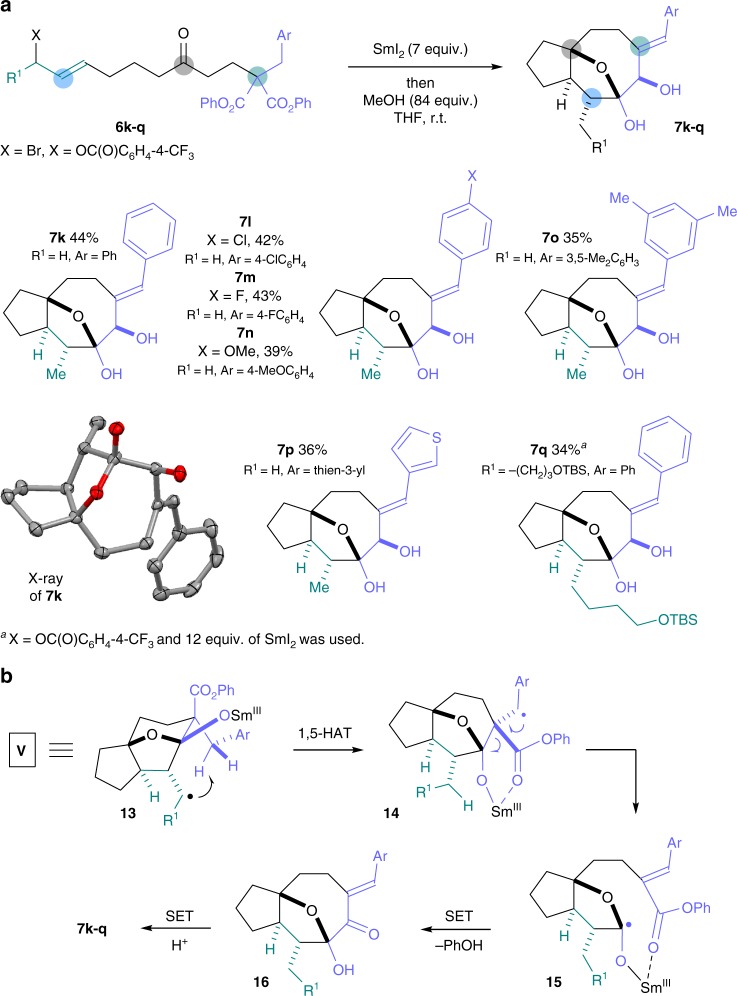

Samarium(II) folding cascades involving 1,5-HAT from a benzylic centre

Building on the successful use of 1,5-HAT to activate secondary alkyl groups in the folding cascades, we proposed that remote activation of a benzylic position could lead to alternative product architectures. Benzyl-containing substrates 6k–q were prepared using suitably substituted malonates III in two steps. Exposure of 6k–q to SmI2 delivered 5,8-carbocylic cascade products 7k–q as single diastereoisomers in moderate yield. Notably, the folding cascades feature five bond-forming events and establish five new contiguous stereocentres. In this case it was found that MeOH, and not H2O, was the optimal protic additive for use in conjunction with SmI248–50. This may be due to the particular conformation of lactone intermediates 4 (Fig. 2; when Y = CH2Ar) and promotion of lactone carbonyl reduction by coordination of SmI2 to the alpha ester group, thus negating the need for water activation of the reagent.51

Importantly, the reductive SET conditions were also shown to be compatible with the presence of halide (formation of 7l and 7m), methoxy (formation of 7n), and heteroaryl substituents (formation of 7p). The carbon-halogen bonds in 7l and 7m provide useful handles for further functionalisation of the cascade products (Fig. 5a). The mechanism of the folding cascade is set out in Fig. 5b. After the initial Barbier cyclisation–lactonisation–lactone cyclisation sequence (see Fig. 2), 1,5-HAT in key radical intermediates 13 allows activation of the benzylic position to give radicals 14. In contrast to the pathway involving tertiary radicals 9, the benzylic radicals 14 undergo fragmentation, presumably promoted by the formation of an alkene that is in conjugation with the aromatic ring and the ester carbonyl. The resultant ketyl-type radicals 15 undergo acyloin-type cyclisation to deliver ketones 16 that are then diastereoselectively reduced (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Folding radical cascades involving 1,5-HAT and activation of a benzylic group. A samarium(II) folding cascade involving activation of benzylic groups by 1,5-HAT in key radical intermediates V is shown. a The scope of the samarium(II) folding cascades involving benzylic group activation by 1,5-HAT to give products 7k–q. b The mechanism of folding involves 1,5-HAT in key radical intermediates V to give 14 and subsequent fragmentation to give ketyl-type radicals 15. Intramolecular acyloin reaction then delivers 16 that undergo diastereoselective reduction to give products 7k–q

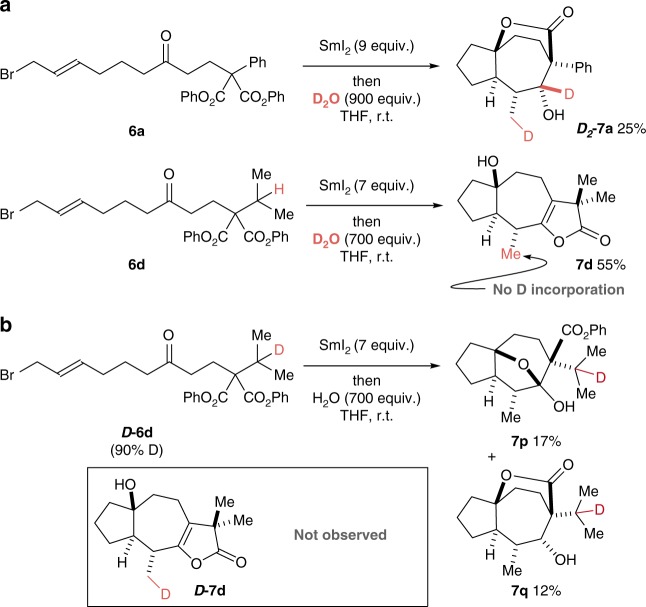

Mechanistic experiments

Mechanistic experiments involving a labelled additive and substrate have been used to probe the HAT pathways (Fig. 6). We first confirmed that a substrate lacking a substituent capable of HAT, substrate 6a, undergoes cascade cyclisation to give labelled product, D2-7a, when exposed to SmI2 and D2O (rather than H2O)52. This observation is consistent with radicals V being reduced and the resulting organosamariums protonated when HAT processes are not in operation. Furthermore, when substrate 6d, bearing an iso-propyl substituent capable of undergoing HAT, was exposed to identical SmI2 and D2O conditions, no deuterium incorporation in the methyl group of product 7d was observed. This suggests that the primary radical intermediate (cf. V) is not quenched by reduction/protonation but is instead quenched by intramolecular HAT.

Fig. 6.

Mechanistic studies. Mechanistic studies involving the use of a labelled additive and a labelled substrate are shown. a, Reaction with SmI2–D2O resulted in the formation of deuterated product D2-7a. This observation supports the operation of the extended SET mechanistic pathway when 1,5-HAT in V is not possible. Treatment of substrate 6d with SmI2–D2O resulted in the formation of non-deuterated product 7d. This reaction outcome supports the operation of a mechanism involving activation of a secondary alkyl group by 1,5-HAT. b, Use of deuterated substrate D-6d in the reaction resulted in the formation of products 7p and 7q (product D-7d was not formed): The presence of deuterium in D-6d blocked 1,5-HAT and redirected folding

To provide further support for 1,5-HAT, labelled substrate D-6d was prepared in which the tertiary hydrogen atom implicated in the HAT processes was exchanged for deuterium. Notably, upon treatment with SmI2 and H2O, cyclisation cascade products 7p and 7q (29%), rather than labelled 7d, were isolated. As 1,5-deuterium transfer is known to be slower than 1,5-HAT53, the deuterium atom in D-6d blocks the final stages of the folding cascade and redirects the process. It is known that deuterium can be used as a ‘protecting group’ to prevent HAT processes and thus the outcome of the reaction of D-6d lends further support to the importance of such a process in the folding cascades54.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed a folding cascade approach to complex polycyclic architectures bearing multiple stereocentres mediated by reductive SET from SmI2. The simple, linear substrates for folding are prepared in a modular, two-step synthesis and straightforward variation of substrate structure leads to three different folding pathways that deliver very different molecular architectures. Two of the folding pathways involve the use of 1,5-HAT to activate and functionalise otherwise inert secondary alkyl and benzylic groups in the substrates. Notably, 1,5-HAT is scarcely seen in the chemistry of SmI2 and rarely exploited and our studies suggest that the incorporation of 1,5-HAT in synthetic methods involving the SET reagent SmI2 can now be considered. In the context of diversity-oriented synthesis, the incorporation of 1,5-HAT processes in radical carbon–carbon bond-forming cascades has the potential to generate complexity and unlock access to diverse molecular structures in the search for new bioactive natural product-like compounds.

Methods

General experimental and characterization

Supplementary Figures 1–82 for the nuclear magnetic resonance spectra, Supplementary Tables 1–6 for X-ray crystallographic data, and Supplementary Methods giving full experimental details and the characterization of compounds are given in the Supplementary Information.

Cascade involving an extended SET pathway

To a solution of SmI2 (9.00 mL, 0.90 mmol, 0.1 M in tetrahydrofuran (THF)), under nitrogen, δ-keto ester 6a’–c’ or 6a–c (0.11 mmoL) in THF (0.70 mL) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture stirred for 14 h at room temperature. After that time, degassed H2O (2.20 mL, 122 mmoL) was added and the reaction was stirred at the same temperature for 24 h before being quenched with air, followed by saturated aqueous Rochelle’s salt and saturated aqueous sodium thiosulphate. The aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O (3 × 15 mL) and the combined organic layers were washed with brine (15 mL), dried over MgSO4, concentrated in vacuo, and purified by column chromatography eluting with EtOAc/hexane (5:95), to give compound 7a’–c’ or 7a–c.

Cascade involving 1,5-HAT and activation of a secondary alkyl group

To a solution of SmI2 (7.00 mL, 0.70 mmoL 0.1 M in THF), under nitrogen, malonate 6d–j (0.10 mmoL) in THF (0.70 mL) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture stirred for 14 h at room temperature. After that time, degassed H2O (1.26 mL, 70.0 mmol) was added and the reaction was stirred at the same temperature for 24 h before being quenched with air, followed by saturated aqueous Rochelle’s salt and saturated aqueous sodium thiosulfate. The aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O (3 × 15 mL) and the combined organic layers were washed with brine (15 mL), dried over MgSO4, concentrated in vacuo, and purified by column chromatography eluting with EtOAc/hexane (5:95), to give compound 7d–j.

Cascade involving 1,5-HAT and activation of a benzylic group

To a solution of SmI2 (7.00 mL, 0.70 mmoL, 0.1 M in THF), malonate 6k–q (0.10 mmoL) in THF (0.70 mL) was added dropwise under nitrogen and stirred for 14 h at room temperature. After that time, degassed MeOH (340 µL, 8.4 mmol) was added and the reaction was stirred at the same temperature for 48 h before being quenched with air followed by saturated aqueous Rochelle's salt and saturated aqueous sodium thiosulfate. The aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O (3 × 15 mL) and the combined organic layers were washed with brine (15 mL), dried over MgSO4, concentrated in vacuo, and purified by column chromatography eluting with Et2O/pentane (20:80), to give compound 7k–q.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the EPSRC (DTA Studentship to M.P.P.; Postdoctoral Fellowship to to X.J.-B. (EP/L00125X/1); Established Career Fellowship to D.J.P. (EP/M005062/1)), CONACyT, México (PhD Scholarship No. 510789 to M.H.G.-C.), and Erasmus+ (placement for P.L.).

Author contributions

M.P.P. and D.J.P. conceived the study and co-wrote the manuscript. M.P.P. designed and performed experiments, and M.H.G.-C., P.L., and X.J.-B. performed experiments.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for 7a’, 7d’, 7a, 7d, 7f, and 7k have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers CCDC 1825583 and 1825585-89. These data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-07194-x.

References

- 1.Schreiber SL. Target-oriented and diversity-oriented organic synthesis in drug discovery. Science. 2000;287:1964–1969. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan DS. Diversity-oriented synthesis: exploring the intersections between chemistry and biology. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:74–84. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0705-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’ Connor CJ, Beckmann HSG, Spring DR. Diversity-oriented synthesis: producing chemical tools for dissecting biology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:4444–4456. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35023h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato N, et al. Diversity-oriented synthesis yields novel multistage antimalarial inhibitors. Nature. 2016;538:344–349. doi: 10.1038/nature19804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galloway WRJD, Isidro-Llobet A, Spring DR. Diversity-oriented synthesis as a tool for the discovery of novel biologically active small molecules. Nat. Commun. 2010;1:1–13. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibbeson BM, et al. Diversity-oriented synthesis as a tool for identifying new modulators of mitosis. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3155. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karageorgis G, Warriner S, Nelson A. Efficient discovery of bioactive scaffolds by activity-directed synthesis. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:872–876. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, et al. Diversity-oriented synthesis as a strategy for fragment evolution against GSK3β. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:852–856. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas GL, et al. Anti-MRSA agent discovery using diversity-oriented synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:2808–2812. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patil NT, Shinde VS, Sridhar B. Relay catalytic branching cascade: a technique to access diverse molecular scaffolds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:2251–2255. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossmann A, Bartlett S, Janecek M, Hodgkinson JT, Spring DR. Diversity-oriented synthesis of drug-like macrocyclic scaffolds using an orthogonal organo- and metal catalysis strategy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:13093–13097. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizoguchi H, Oikawa H, Oguri H. Biogenetically inspired synthesis and skeletal diversification of indole alkaloids. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:57–64. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Echemendía R, et al. Highly stereoselective synthesis of natural-product-like hybrids by an organocatalytic/multicomponent reaction sequence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:7621–7625. doi: 10.1002/anie.201412074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lachkar D, et al. Unified biomimetic assembly of voacalgine A and bipleiophylline via divergent oxidative couplings. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:793–798. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliver DW, Malan SF. Medicinal chemistry of polycyclic cage compounds in drug discovery research. Med. Chem. Res. 2008;17:137–151. doi: 10.1007/s00044-007-9044-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockdale TP, Williams CM. Pharmaceuticals that contain polycyclic hydrocarbon scaffolds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:7737–7763. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00477A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovering F, Bikker J, Humblet C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:6752–6756. doi: 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke MD, Schreiber SL. A planning strategy for diversity-oriented synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:46–58. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolaou KC, Edmonds DJ, Bulger PG. Cascade reactions in total synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:7134–7186. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morton D, Leach S, Cordier C, Warriner S, Nelson A. Synthesis of natural-product-like molecules with over eighty distinct scaffolds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:104–109. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu W, Khedkar V, Baskar B, Schürmann M, Kumar K. Branching cascades: a concise synthetic strategy targeting diverse and complex molecular frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6900–6905. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Castro M, et al. De novo branching cascades for structural and functional diversity in small molecules. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6516. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burke MD. Generating diverse skeletons of small molecules combinatorially. Science. 2003;302:613–618. doi: 10.1126/science.1089946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plesniak MP, Huang HM, Procter DJ. Radical cascade reactions triggered by single electron transfer. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017;1:77. doi: 10.1038/s41570-017-0077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kern N, Plesniak MP, McDouall JJW, Procter DJ. Enantioselective cyclizations and cyclization cascades of samarium ketyl radicals. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:1198–1204. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keylor MH, et al. Synthesis of resveratrol tetramers via a stereoconvergent radical equilibrium. Science. 2016;354:1260–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.aaj1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu JCK, Rovis T. Amide-directed photoredox-catalysed C–C bond formation at unactivated sp3 C–H bonds. Nature. 2016;539:272–275. doi: 10.1038/nature19810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi GJ, Zhu Q, Miller DC, Gu CJ, Knowles RR. Catalytic alkylation of remote C–H bonds enabled by proton-coupled electron transfer. Nature. 2016;539:268–271. doi: 10.1038/nature19811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dauncey EM, Morcillo SP, Douglas JJ, Sheikh NS, Leonori D. Photoinduced remote functionalisations by iminyl radical promoted C−C and C−H bond cleavage cascades. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:744–748. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shu W, Lorente A, Gómez-Bengoa E, Nevado C. Expeditious diastereoselective synthesis of elaborated ketones via remote Csp3–H functionalization. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:13832. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamago S, Miyazoe H, Nakayama T, Miyoshi M, Yoshida J. A diversity-oriented synthesis of α-amino acid derivatives by a silyltelluride-mediated radical coupling reaction of imines and isonitriles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:117–120. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L, et al. Radical aryl migration enables diversity-oriented synthesis of structurally diverse medium/macro- or bridged-rings. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuznetsov DM, Kutateladze AG. Step-economical photoassisted diversity-oriented synthesis: sustaining cascade photoreactions in oxalyl anilides to access complex polyheterocyclic molecular architectures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:16584–16590. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b07598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, et al. A radical cascade enabling collective syntheses of natural products. Chem. 2017;2:803–816. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szostak M, Fazakerley NJ, Parmar D, Procter DJ. Cross-coupling reactions using samarium(II) iodide. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:5959–6039. doi: 10.1021/cr400685r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molander GA. Application of lanthanide reagents in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 1992;92:29–68. doi: 10.1021/cr00009a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kagan HB. Twenty-five years of organic chemistry with diiodosamarium: an overview. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:10351–10372. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2003.09.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beemelmanns C, Reissig HU. Samarium diiodide induced ketyl-(het)arene cyclisations towards novel N-heterocycles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:2199. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00116c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murakami M, Hayashi M, Ito Y. Generation and alkylation of carbanions α to the nitrogen of amines by a new metallation procedure. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:793–794. doi: 10.1021/jo00029a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hölemann A, Reissig HU. Samarium diiodide-induced couplings of carbonyl compounds with methoxyallene leading to 4-hydroxy 1-enol ethers. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1463–1466. doi: 10.1021/ol0342251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hölemann A, Reißig HU. Regioselective samarium diiodide induced couplings of carbonyl compounds with 1,3-diphenylallene and alkoxyallenes: a new route to 4-hydroxy-1-enol ethers. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:5493–5506. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Just-Baringo X, Procter DJ. Sm(II)-mediated electron transfer to carboxylic acid derivatives: development of complexity generating cascades. ACC Chem. Res. 2015;48:1263–1275. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamochi Y, Kudo T. Novel reduction of carboxylic acids, esters, amides and nitriles using samarium diiodide in the presence of water. Chem. Lett. 1993;22:1495–1498. doi: 10.1246/cl.1993.1495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parmar D, et al. Reductive cyclization cascades of lactones using SmI2−H2O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2418–2420. doi: 10.1021/ja1114908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasegawa E, Curran DP. Rate constants for the reactions of primary alkyl radicals with SmI2 in THF/HMPA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:1717–1720. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)60760-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karl CL, Maas EJ, Reusch W. Acyl rearrangements in radical reactions. J. Org. Chem. 1972;37:2834–2840. doi: 10.1021/jo00983a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rudkin IM, Miller LC, Procter DJ. Samarium enolates and their applications in organic synthesis. Organomet. Chem. 2008;34:19–45. doi: 10.1039/b606111g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chopade PR, Prasad E, Flowers RA. The role of proton donors in SmI2-mediated ketone reduction: new mechanistic insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:44–45. doi: 10.1021/ja038363x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keck GE, Wager CA. The first directed reduction of β-alkoxy ketones to anti 1,3-diol monoethers: identification of spectator and director alkoxy groups. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2307–2309. doi: 10.1021/ol006072c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hutton TK, Muir KW, Procter DJ. Switching between novel samarium(II)-mediated cyclizations by a simple change in alcohol cosolvent. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4811–4814. doi: 10.1021/ol0358399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szostak M, Spain M, Choquette KA, Flowers RA, II, Procter DJ. Substrate-directable electron transfer reactions. dramatic rate enhancement in the chemoselective reduction of cyclic esters using SmI2–H2O: mechanism, scope, and synthetic utility. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:15702. doi: 10.1021/ja4078864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szostak M, Spain M, Procter DJ. Selective synthesis of α,α-dideuterio alcohols by the reduction of carboxylic acids using SmI2 and D2O as deuterium source under SET conditions. Org. Lett. 2014;16:5052–5055. doi: 10.1021/ol502404e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeZutter CB, Horner JH, Newcomb M. Rate constants for 1,5- and 1,6-hydrogen atom transfer reactions of mono-, di-, and tri-aryl-substituted donors, models for hydrogen atom transfers in polyunsaturated fatty acid radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:1891–1896. doi: 10.1021/jp710750f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wood ME, Bissiriou S, Lowe C, Windeatt KM. Investigations into the effectiveness of deuterium as a ‘protecting group’ for C–H bonds in radical reactions involving hydrogen atom transfer. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:3048. doi: 10.1039/b810018g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for 7a’, 7d’, 7a, 7d, 7f, and 7k have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers CCDC 1825583 and 1825585-89. These data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information file.