Abstract

Parkinson's disease (PD) is common, age-dependent neurodegenerative disorder caused by a severe loss of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. Given the projected increase in the number of people with PD over the coming decades, interventions aimed at minimizing morbidity and improve quality of life are crucial. There is currently no fully proven pharmacological therapy that can modify or slow the disease progression. Physical activity (PA) can complement pharmacological therapy to manage the inherent decline associated with the disease. The evidence indicates that upregulation of neurotrophins and nerve growth factors are potentially critical mediators of the beneficial effects associated with PA. Accumulating evidence suggests that patients with PD might benefit from PA in a number of ways, from general improvements in health to disease-specific effects and potentially, disease-modifying effects. Various forms of PA that have shown beneficial effects in PD include – aerobic exercises, treadmill training, dancing, traditional Chinese exercise, yoga, and resistance training. In this review, we explored available research that addresses the impact of exercise and PA on PD. The original articles with randomized control trials, prospective cohort studies, longitudinal studies, meta-analysis, and relevant review articles from 2005 to 2017 were selected for the present review. Many gaps remain in our understanding of the most effective exercise intervention for PD symptoms, the mechanisms underlying exercise-induced changes and the best way to monitor response to therapy. However, available research suggests that exercise is a promising, cost-effective, and low-risk intervention to improve both motor and nonmotor symptoms in patients with PD. Thus, PA should be prescribed and encouraged in all PD patients.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, physical activity, review

INTRODUCTION

The benefits of regular physical activity (PA) are extensive: PA increases survival and prevents people from chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, hypertension, obesity, depression, and osteoporosis. Several biological mechanisms may be responsible for the benefits associated with PA.[1] PA has also been found to influence the brain's neurochemistry and plasticity.[2] The evidence indicates that upregulation of neurotrophins and various nerve growth factors are potentially critical mediators of the beneficial effects associated with PA.[3] In addition, reducing oxidative stress, enhancing energy production, and mitochondrial function also contribute to exercise-induced neuroprotection.[4] The beneficial effects of PA on the central nervous system (CNS) also work through adaptive neuroplasticity.[5] Studies in healthy rodents have shown that regular exercise triggers changes in CNS plasticity which includes synaptogenesis, enhanced glucose utilization, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis.[6] Imaging studies have shown the beneficial effect of exercise in humans. For example, PA-induced increase in the volume of gray and white matter in healthy individuals.[7]

Parkinson's disease (PD) is common, age-dependent neurodegenerative disorder caused by a severe loss of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons.[3] Given the projected increase in the number of people with PD over the coming decades, interventions aimed at minimizing morbidity and improve quality of life are crucial. Although the dopamine replacement therapy is effective for relieving the motor deficits, PD has a progressive course. There is currently no fully proven pharmacological therapy that can modify or slow the disease progression. Thus, finding alternative, nonpharmacotherapies are necessary to delay and slow the dopamine neuron degeneration. PA can complement pharmacological therapy to manage the inherent decline associated with the disease.[8] Accumulating evidence suggests that patients with PD might benefit from PA in a number of ways. PA may lead disease-modifying effects in addition to general improvements in health of PD patients.[9] We, therefore, undertook this review to summarize the effects of PA on people living with PD.

METHODOLOGY

In order to identify relevant English literature, we searched PubMed using mainly a combination of the following keywords – PD, PA, exercise, physiotherapy, physical therapy, rehabilitation, dance, yoga, traditional Chinese exercise, and aerobics. The original articles with randomized control trials, prospective cohort studies, longitudinal studies, meta-analysis, and relevant review articles from 2005 to 2017 were selected for the present review. Important characteristics and outcomes of these studies were extracted and summarized in the present review.

DEFINITION OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

PA is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that result in energy expenditure, which can be measured in kilocalories.[10] The term “exercise” has been used interchangeably with “PA,” since the two share many common elements.[11] Exercise is a subcategory of PA involving planned, structured, repetitive, and purposeful body movements to improve or to maintain one or more components of PA.[10]

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN PARKINSON'S DISEASE: ANIMAL STUDIES

Various studies have revealed PA-related neuroprotection in animal models of Parkinsonism. Neuroprotection in PD is apparently mediated by brain neurotropic factors and neuroplasticity. The detailed discussion of each of these studies goes beyond the scope of this article. There are excellent reviews available on this aspect. The literature may be summarized as follows. PA in Parkinsonian animal models induces brain neurotrophic factor expression, which may mediate neuroprotective effects.[12] The factors include – brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF).[13] Other exercise effects in PD animal models include – enhanced neural progenitor cell proliferation and migration as well as reversal of age-related decline in substantia nigra vascularization, apparently mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor expression.[13,14] All these changes in CNS apparently lead to the neuroprotective effect caused by PA. Although the evidence from animal studies cannot be directly applied to mechanisms in humans, studies have suggested that PD patients would likely experience a meaningful improvement and disease-modifying effect in response to PA.[13]

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN PARKINSON'S DISEASE: EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDIES

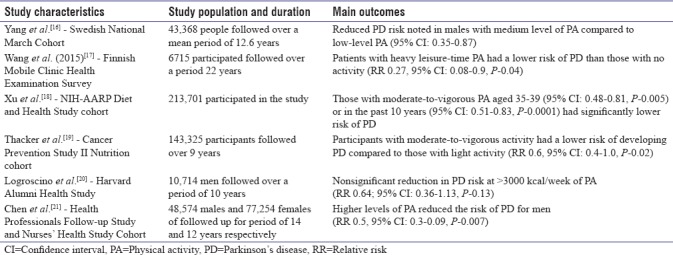

A beneficial relationship between PA and PD was first suggested in 1992, when Sasco and colleagues reported that the risk of PD was reduced in men who played sports in college and adult life.[15] This finding has been replicated in nearly all subsequent epidemiologic studies [Table 1]. For example, among 43,368 participants in the Swedish National March cohort, male participants who spent >6 h per week on household and commuting activity had 43% lower risk of PD compared to those with <2 h per week of such activities.[16] Similarly, risk of PD was reduced who engaged in heavy leisure-time PA in Finnish Mobile Clinic Health Examination Survey.[17]

Table 1.

Epidemiological studies on the role of physical activity in Parkinson’s disease

Two studies suggested that PA may influence PD risk differently for men and women.[16,21] In the “health professionals follow-up and nurses health studies,” higher levels of exercise reduced the risk of PD for men but not for women.[21] Similarly, in the “Swedish National March cohort study,” PA was associated with a decreased PD risk for men, but the benefit was less clear for women.[16] Men and women may have different biological responses to PA.[22] The lack of associations between PA and PD risk in females may be explained by (1) methodological issues like low statistical power resulting from smaller number of female PD subjects and/or (2) females may have physiologically different responses to exercise than males, with a less sustained alteration in metabolic rate and lipid metabolism.[23] Although differential effects in men and women are probable, other large studies found PA to similarly benefit both men and women.[18,19,20] Thus, determining whether PA has different effects in men and women needs further investigation and will be important in developing appropriate interventions.[8] Taken together, these studies provide compelling evidence for an inverse association between PA or exercise and risk of PD.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN PARKINSON'S DISEASE: CLINICAL STUDIES

Motor symptoms

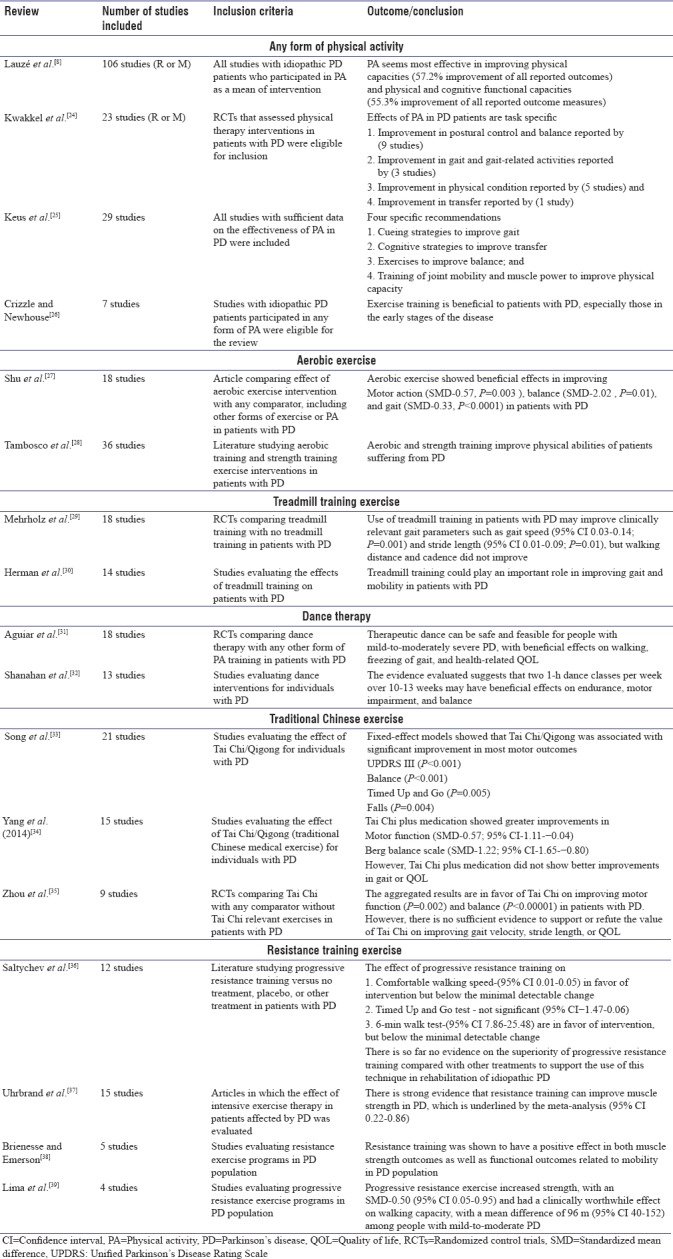

Individuals with PD invariably experience functional decline in a number of motor domains including posture, balance, gait and transfers. Clinical studies have examined effects of various type of exercise on motor features of PD and reported positive results. We have summarized various review articles and meta-analysis demonstrating the effect of PA and specific type of exercise on motor features of PD in Table 2. We identified 19 systematic reviews and meta-analysis from 2005 to 2017.

Table 2.

Summary of reviews and meta-analysis on the effects of physical activity on motor features in Parkinson’s disease

The first systematic review on effectiveness of PA in PD was published in 2001.[40] Since then, many subsequent reviews have followed. Most of these reviews supported the effectiveness of PA for people with PD. PA may help to improve mobility, balance, and well-being in patients with PD.[8,24,25,26]

A systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of aerobic exercise for PD suggested that aerobic exercise significantly improve motor action, balance, and gait including gait velocity, stride/step length, and walking ability in patients with PD.[27,28] The time has come to apply the same standards to exercise as to drugs and to determine the adequate “dose” of aerobic exercise (i.e., frequency, intensity, and duration).

Mehrholz et al.'s review concluded that treadmill training was likely to improve gait, hypokinesia, and showed better safety.[29] Herman's systematic review also suggested that treadmill training should play an important role in improving gait and mobility in the management of patients with PD.[30]

Compared with routine PA, dancing might enhance long-term adherence, compliance, and enjoyment in patients with PD.[31] Evidence is emerging that dancing can be a beneficial form of PA for people with mild-to-moderate PD.[31,32] A recent review by Aguiar et al. showed that therapeutic dancing could be beneficial for improving mobility and balance in people with PD.[31] Furthermore, Dhami et al. hypothesized that rhythmical music used in dancing could activate neurons serving motor control and increase blood flow in regions such as the hippocampus and frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices. This could facilitate neuroplasticity and in turn improve movement, balance, and cognition.[41]

A meta-analysis on the efficacy of Tai Chi in patients with PD suggests that Tai Chi can significantly improve the motor function and balance in patients with PD.[33] A review on the effect of traditional Chinese exercise on PD showed a positive effect of Tai Chi and Qigong exercise in improving motor function and balance in patients with mild-to-moderate PD.[34,35] Thus, there is sufficient evidence from high-quality studies that Tai Chi is safe, feasible, and can improve postural stability in PD. Since long-term longitudinal studies are lacking, the duration of benefit from Tai Chi is unclear.

Yoga is a discipline which dates back to India circa 2000 BC but has only recently gained popularity throughout the Western world. Preliminary results from two reviews suggest that yoga provides modest improvements in functional mobility, balance, upper and lower-limb flexibility and strength. Yoga also helps to reduce the fear of falling. The current evidence suggests that yoga is acceptable, beneficial and safe to PD populations.[25] However, the future trials are needed to determine long-term implications and dosage of yoga therapy (frequency, intensity, and timing) in the PD population.

Progressive resistance training (PRT) is a relatively new intervention for PD. Saltychev et al. emphasized the lack of robust data on the effect of PRT in PD.[36] On the other hand, few studies have shown a positive effect of PRT on muscle strength and mobility in patients with PD.[37,38,39] A combined aerobic and strength exercise intervention was suggested to be even more effective. Thus, to make definite clinical recommendations on the possible use of PRT in PD, further research should focus on larger sample sizes with sufficient follow-up periods. In addition, the safety of PRT in PD population should also be evaluated.

Thus, PA of various types, including aerobics, treadmill training, PRT, dance, Tai Chi and yoga has demonstrated improvement in certain PD motor symptoms. Further studies are warranted to understand which exercise protocol is most beneficial and to determine the adequate “dose” of exercise (i.e., frequency, intensity, and duration) for better gains.

NONMOTOR SYMPTOMS

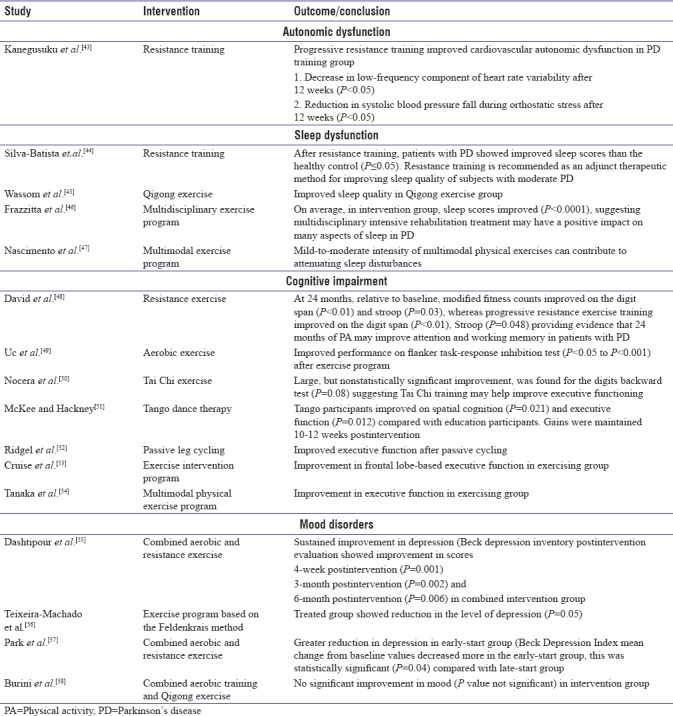

While PD is most commonly associated with motor symptoms, there are numerous nonmotor symptoms associated with the condition such as hyposmia, constipation, cognitive impairment, autonomic dysfunction, sleep disorders, and neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and apathy.[42] These nonmotor symptoms adversely affect the quality of life and can be even more disabling than the motor symptoms. Medications are often inadequately effective and can cause intolerable side effects. There is, therefore, an increased interest in the role of nonpharmacologic therapies to treat nonmotor symptoms in PD. PA has established efficacy for treating nonmotor symptoms in addition to motor symptoms of PD.[42] We have summarized articles addressing the effects of PA on nonmotor features of PD as the primary outcome in Table 3.

Table 3.

Role of physical activity in nonmotor features in Parkinson’s disease

Autonomic dysfunction is common in PD; with the reported prevalence ranging from 14% to 80%.[59] It may include dysregulation of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, urinary, and thermoregulatory systems.[60] Only one study has been published that addressed the effects of PA on cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in PD. In this study, PD participants performing exercise had improved cardiac sympathetic modulation, as measured by heart rate variability and blood pressure response.[43] In patients with PD, autonomic impairment of gastrointestinal and urinary tract is also common. No studies to date have investigated the influence of PA on gastrointestinal and bladder dysfunction as the primary outcome.

Sleep dysfunction is another common nonmotor symptom in PD, affecting up to 98% of patients.[61] PA has shown promise for improving sleep in patients with PD as well. Silva-Batista et al. found PD group undergoing resistance training had significant improvement in sleep quality.[44] The study used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index to assess sleep quality before and after the intervention. Another study used a Qigong exercise intervention in Patients with PD. After 6 months of Qigong exercise intervention, investigator reported improvement in PD sleep scale score in intervention receiving group.[45] Frazzitta et al. and Nascimento et al. found improvement in sleep scores in PD group that participated in a multidisciplinary exercise program.[46,47] Taken together, these studies indicate that many different types of PA can improve subjective sleep quality in PD.

Cognitive impairment significantly affects the quality of life in PD. These impairments remain difficult to manage with current clinical therapies, but exercise has been identified as a possible treatment.[42] The clinical studies showed that various types of exercise, including aerobic, resistance, and dance can improve cognitive function, although the optimal type, amount, mechanisms, and duration of exercise are unclear. A study by David et al. suggested that resistance exercise may benefit cognition in patients with PD.[48] Uc et al. reported improvement in response inhibition test in PD patients who participated in 6-month aerobic exercise program, whereas Nocera et al. reported improvement in executive function after Tai Chi.[49,50] McKee et al. investigated the effects of community-based tango on spatial cognition and disease severity in PD.[51] PD patients with mild-to-moderate disease were assigned to twenty 90-min tango lessons over 12 weeks. Tango participants improved on disease severity, spatial cognition, and executive function compared to control group. Another study examined the effects of passive leg cycling on executive function in PD.[52] Executive function was assessed with trail-making test A and B before and after passive leg cycling. Significant improvements on the trail-making test-B occurred after passive leg cycling. A study by Cruise et al. found improvement in frontal lobe-based executive function in PD patients allocated to an exercise intervention program.[53] Tanaka et al. analyzed the effects of a multimodal physical exercise program on executive functioning.[54] Participants in the exercise group showed improvement in executive function, as measured by the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Regardless of variations in intensity, mode, and duration of exercise program across these studies; they provide a good evidence for the use of PA to improve cognitive function in PD.

Mood disturbance (anxiety, depression, and apathy) develop in many individuals with PD, even in the early stages of the disease, contributing to poorer quality of life and caregiver burden. There is promising evidence that PA may improve mood among adults with neurologic disorders and healthy older adults.[62] The research on the effects of PA on mood in PD is limited.[56,57,58] In a sample of 11 participants with PD, 5 participants completed a 4-week general exercise program and 6 participants completed an exercise-based behavioral treatment. The combined group showed improvement in depression and fatigue at all postintervention assessments, suggesting benefits of both exercise approaches.[55] Teixeira-Machado et al. showed improvement in depression for the PD group who underwent 50 sessions of an exercise program based on the Feldenkrais method.[56] In randomized control trials, individuals with PD were randomized to either an early or late start group exercise program. Participants in the early-start group reported significantly fewer depressive symptoms after 48 weeks relative to the delayed-start group.[57] In general, these studies provide strong rationale for the targeted use of exercise to improve mood in PD. Large longitudinal clinical trials are needed to examine the sustained benefit of PA on mood disorders in PD population.

Although many gaps remain in our understanding of the most effective exercise intervention for nonmotor symptoms in PD, available research suggests that PA is a promising approach to improve nonmotor symptoms in patients with PD.

Most of the animal, epidemiological, and clinical studies have indicated that PA not only has a significant preventive effect on PD but also has therapeutic value. Hence, PA should be promoted in general population and should be an essential component of the treatment for PD.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Epidemiological data indicate that exercise may reduce the risk of developing PD. There is now a convincing body of clinical evidence suggesting that PA is beneficial, cost-effective, and low-risk intervention that improves overall health and provides promise for improving both motor and non-motor symptoms in PD. Furthermore, experimental studies have highlighted the neuroprotective and neurorestorative effects of exercise, but these findings have yet to be translated to the human disease.[9] Thus, exercise should be prescribed and encouraged in all PD patients. When recommending an increase in PA in PD patients, several factors specific to patients with PD should be considered. These factors include motor symptoms, the risk of falls, apathy, fatigue, depression, and cognitive dysfunction. Any of these symptoms can reduce participation in PA and can contribute to a more sedentary lifestyle among patients with PD. Strategies to improve participation include the development of community-based programs and discussing ways to reduce barriers to exercise with the patient and caregiver.[42]

Although most studies suggest that exercise promotes improvements in motor and nonmotor symptoms in PD, many questions remain unanswered. For example, which form of exercise is most effective in reducing PD risk or improving motor and nonmotor symptoms, how frequent exercise should be performed for maximal benefit, and when exercise should start. These and other unanswered questions in combination with the promise of therapeutic efficacy of exercise on the different aspects of motor and nonmotor symptoms in PD make exercise interventions an exciting area of research.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174:801–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Silva PG, Domingues DD, de Carvalho LA, Allodi S, Correa CL. Neurotrophic factors in Parkinson's disease are regulated by exercise: Evidence-based practice. J Neurol Sci. 2016;363:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hou L, Chen W, Liu X, Qiao D, Zhou FM. Exercise-induced neuroprotection of the nigrostriatal dopamine system in Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:358. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petzinger GM, Fisher BE, McEwen S, Beeler JA, Walsh JP, Jakowec MW, et al. Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:716–26. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillman CH, Erickson KI, Kramer AF. Be smart, exercise your heart: Exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:58–65. doi: 10.1038/nrn2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch MA, Farley BG. Exercise and neuroplasticity in persons living with Parkinson's disease. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;45:215–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colcombe SJ, Erickson KI, Scalf PE, Kim JS, Prakash R, McAuley E, et al. Aerobic exercise training increases brain volume in aging humans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:1166–70. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.11.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauzé M, Daneault JF, Duval C. The effects of physical activity in Parkinson's disease: A Review. J Parkinsons Dis. 2016;6:685–98. doi: 10.3233/JPD-160790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speelman AD, van de Warrenburg BP, van Nimwegen M, Petzinger GM, Munneke M, Bloem BR, et al. How might physical activity benefit patients with Parkinson disease? Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:528–34. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100:126–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu PL, Lee M, Huang TT. Effectiveness of physical activity on patients with depression and Parkinson's disease: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahlskog JE. Does vigorous exercise have a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson disease? Neurology. 2011;77:288–94. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225ab66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tajiri N, Yasuhara T, Shingo T, Kondo A, Yuan W, Kadota T, et al. Exercise exerts neuroprotective effects on Parkinson's disease model of rats. Brain Res. 2010;1310:200–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen AD, Tillerson JL, Smith AD, Schallert T, Zigmond MJ. Neuroprotective effects of prior limb use in 6-hydroxydopamine-treated rats: Possible role of GDNF. J Neurochem. 2003;85:299–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasco AJ, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Gendre I, Wing AL. The role of physical exercise in the occurrence of Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:360–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530280040020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang F, Trolle Lagerros Y, Bellocco R, Adami HO, Fang F, Pedersen NL, et al. Physical activity and risk of Parkinson's disease in the swedish national march cohort. Brain. 2015;138:269–75. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang YL, Wang YT, Li JF, Zhang YZ, Yin HL, Han B, et al. Body mass index and risk of Parkinson's disease: A Dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Q, Park Y, Huang X, Hollenbeck A, Blair A, Schatzkin A, et al. Physical activities and future risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;75:341–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ea1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thacker EL, Chen H, Patel AV, McCullough ML, Calle EE, Thun MJ, et al. Recreational physical activity and risk of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:69–74. doi: 10.1002/mds.21772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Logroscino G, Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Lee IM. Physical activity and risk of Parkinson's disease: A prospective cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:1318–22. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.097170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen H, Zhang SM, Schwarzschild MA, Hernán MA, Ascherio A. Physical activity and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2005;64:664–9. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151960.28687.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaHue SC, Comella CL, Tanner CM. The best medicine? The influence of physical activity and inactivity on Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31:1444–54. doi: 10.1002/mds.26728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galassetti PR, Nemet D, Pescatello A, Rose-Gottron C, Larson J, Cooper DM, et al. Exercise, caloric restriction, and systemic oxidative stress. J Investig Med. 2006;54:67–75. doi: 10.2310/6650.2005.05024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwakkel G, de Goede CJ, van Wegen EE. Impact of physical therapy for Parkinson's disease: A critical review of the literature. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(Suppl 3):S478–87. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(08)70053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Practice Recommendations Development Group. Keus SH, Bloem BR, Hendriks EJ, Bredero-Cohen AB, Munneke M, et al. Evidence-based analysis of physical therapy in Parkinson's disease with recommendations for practice and research. Mov Disord. 2007;22:451–60. doi: 10.1002/mds.21244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crizzle AM, Newhouse IJ. Is physical exercise beneficial for persons with Parkinson's disease? Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:422–5. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000244612.55550.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shu HF, Yang T, Yu SX, Huang HD, Jiang LL, Gu JW, et al. Aerobic exercise for Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tambosco L, Percebois-Macadré L, Rapin A, Nicomette-Bardel J, Boyer FC. Effort training in Parkinson's disease: A systematic review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57:79–104. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehrholz J, Friis R, Kugler J, Twork S, Storch A, Pohl M, et al. Treadmill training for patients with Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD007830. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007830.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herman T, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Treadmill training for the treatment of gait disturbances in people with Parkinson's disease: A mini-review. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2009;116:307–18. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0139-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aguiar LP, da Rocha PA, Morris M. Therapeutic dancing for Parkinson's Disease. Int J Gerontol. 2016;10:64–70. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanahan J, Morris ME, Bhriain ON, Saunders J, Clifford AM. Dance for people with Parkinson disease: What is the evidence telling us? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:141–53. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song R, Grabowska W, Park M, Osypiuk K, Vergara-Diaz GP, Bonato P, et al. The impact of tai chi and qigong mind-body exercises on motor and non-motor function and quality of life in Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;41:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Y, Li XY, Gong L, Zhu YL, Hao YL. Tai chi for improvement of motor function, balance and gait in Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou J, Yin T, Gao Q, Yang XC. A meta-analysis on the efficacy of tai chi in patients with Parkinson's disease between 2008 and 2014. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:593263. doi: 10.1155/2015/593263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saltychev M, Bärlund E, Paltamaa J, Katajapuu N, Laimi K. Progressive resistance training in Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e008756. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uhrbrand A, Stenager E, Pedersen MS, Dalgas U. Parkinson's disease and intensive exercise therapy – A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurol Sci. 2015;353:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brienesse LA, Emerson MN. Effects of resistance training for people with Parkinson's disease: A systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:236–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lima LO, Scianni A, Rodrigues-de-Paula F. Progressive resistance exercise improves strength and physical performance in people with mild to moderate Parkinson's disease: A systematic review. J Physiother. 2013;59:7–13. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Goede CJ, Keus SH, Kwakkel G, Wagenaar RC. The effects of physical therapy in Parkinson's disease: A research synthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:509–15. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.22352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dhami P, Moreno S, DeSouza JF. New framework for rehabilitation-fusion of cognitive and physical rehabilitation: The hope for dancing. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1478. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amara AW, Memon AA. Effects of exercise on non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Clin Ther. 2018;40:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanegusuku H, Silva-Batista C, Peçanha T, Nieuwboer A, Silva ND, Jr, Costa LA, et al. Effects of progressive resistance training on cardiovascular autonomic regulation in patients with Parkinson disease: A Randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:2134–41. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silva-Batista C, de Brito LC, Corcos DM, Roschel H, de Mello MT, Piemonte MEP, et al. Resistance training improves sleep quality in subjects with moderate Parkinson's disease. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31:2270–7. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wassom DJ, Lyons KE, Pahwa R, Liu W. Qigong exercise may improve sleep quality and gait performance in Parkinson's disease: A pilot study. Int J Neurosci. 2015;125:578–84. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2014.966820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frazzitta G, Maestri R, Ferrazzoli D, Riboldazzi G, Bera R, Fontanesi C, et al. Multidisciplinary intensive rehabilitation treatment improves sleep quality in Parkinson's disease. J Clin Mov Disord. 2015;2:11. doi: 10.1186/s40734-015-0020-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nascimento CM, Ayan C, Cancela JM, Gobbi LT, Gobbi S, Stella F, et al. Effect of a multimodal exercise program on sleep disturbances and instrumental activities of daily living performance on Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14:259–66. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.David FJ, Robichaud JA, Leurgans SE, Poon C, Kohrt WM, Goldman JG, et al. Exercise improves cognition in Parkinson's disease: The PRET-PD randomized, clinical trial. Mov Disord. 2015;30:1657–63. doi: 10.1002/mds.26291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uc EY, Doerschug KC, Magnotta V, Dawson JD, Thomsen TR, Kline JN, et al. Phase I/II randomized trial of aerobic exercise in Parkinson disease in a community setting. Neurology. 2014;83:413–25. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nocera JR, Amano S, Vallabhajosula S, Hass CJ. Tai chi exercise to improve non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. J Yoga Phys Ther. 2013;3:1208–31. doi: 10.4172/2157-7595.1000137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McKee KE, Hackney ME. The effects of adapted tango on spatial cognition and disease severity in Parkinson's disease. J Mot Behav. 2013;45:519–29. doi: 10.1080/00222895.2013.834288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ridgel AL, Kim CH, Fickes EJ, Muller MD, Alberts JL. Changes in executive function after acute bouts of passive cycling in Parkinson's disease. J Aging Phys Act. 2011;19:87–98. doi: 10.1123/japa.19.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cruise KE, Bucks RS, Loftus AM, Newton RU, Pegoraro R, Thomas MG, et al. Exercise and Parkinson's: Benefits for cognition and quality of life. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;123:13–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanaka K, Quadros AC, Jr, Santos RF, Stella F, Gobbi LT, Gobbi S, et al. Benefits of physical exercise on executive functions in older people with Parkinson's disease. Brain Cogn. 2009;69:435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dashtipour K, Johnson E, Kani C, Kani K, Hadi E, Ghamsary M, et al. Effect of exercise on motor and nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2015;2015:586378. doi: 10.1155/2015/586378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teixeira-Machado L, Araújo FM, Cunha FA, Menezes M, Menezes T, Melo DeSantana J, et al. Feldenkrais method-based exercise improves quality of life in individuals with Parkinson's disease: A controlled, randomized clinical trial. Altern Ther Health Med. 2015;21:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park A, Zid D, Russell J, Malone A, Rendon A, Wehr A, et al. Effects of a formal exercise program on Parkinson's disease: A pilot study using a delayed start design. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:106–11. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burini D, Farabollini B, Iacucci S, Rimatori C, Riccardi G, Capecci M, et al. A randomised controlled cross-over trial of aerobic training versus qigong in advanced Parkinson's disease. Eura Medicophys. 2006;42:231–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ziemssen T, Reichmann H. Treatment of dysautonomia in extrapyramidal disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2010;3:53–67. doi: 10.1177/1756285609348902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Asahina M, Vichayanrat E, Low DA, Iodice V, Mathias CJ. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinsonian disorders: Assessment and pathophysiology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:674–80. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-303135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lees AJ, Blackburn NA, Campbell VL. The nighttime problems of Parkinson's disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1988;11:512–9. doi: 10.1097/00002826-198812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reynolds GO, Otto MW, Ellis TD, Cronin-Golomb A. The therapeutic potential of exercise to improve mood, cognition, and sleep in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31:23–38. doi: 10.1002/mds.26484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]