Abstract

Circulating monocytes can compete for virtually any tissue macrophage niche and become long-lived replacements that are phenotypically indistinguishable from their embryonic counterparts. As the factors regulating this process are incompletely understood, we studied niche competition in the brain by depleting microglia with >95% efficiency using Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice and monitored long-term repopulation. Here we show that the microglial niche is repopulated within weeks by a combination of local proliferation of CX3CR1+F4/80lowClec12a– microglia and infiltration of CX3CR1+F4/80hiClec12a+ macrophages that arise directly from Ly6Chi monocytes. This colonization is independent of blood brain barrier breakdown, paralleled by vascular activation, and regulated by type I interferon. Ly6Chi monocytes upregulate microglia gene expression and adopt microglia DNA methylation signatures, but retain a distinct gene signature from proliferating microglia, displaying altered surface marker expression, phagocytic capacity and cytokine production. Our results demonstrate that monocytes are imprinted by the CNS microenvironment but remain transcriptionally, epigenetically and functionally distinct.

Brain microglial cells can be replenished by blood-derived monocytes, but many aspects of this repopulation remain unclear. Here the authors show that the brain microglial niche can be replaced both by proliferating, residential microglia as well as differentiated Ly6Chi monocytes, with the latter having overlapping but distinct characteristics.

Introduction

All organs in the body house resident macrophage populations with duties that are tailored to the function of that organ. For example, brain microglia promote neuronal wiring, splenic red pulp macrophages (RPM) eliminate dying erythrocytes in the spleen and alveolar macrophages recycle surfactant in the lung. It is now well-recognized that the majority of these tissue macrophages are derived from embryonic precursors that self-maintain throughout adulthood1–4 rather than from continuous monocyte input, as was previously suggested5. During development of the embryo, tissues are seeded with successive waves of hematopoietic precursors from the yolk sac and fetal liver1,6–8, which following birth are displaced by BM-derived monocytes in some organs9–14. Furthermore, upon infection or injury, circulating blood monocytes can give rise to long-lived replacements of macrophages in many organs including the heart15, liver16, lung17, and brain18,19. The final macrophage composition can thus be heterogeneous across organs, and this has complicated recent attempts to assign macrophage nomenclature based on their ontogeny20. Whether the ontogeny of resident macrophage populations ultimately dictates functionality is not well understood and may vary depending on the circumstances generating the macrophage21.

The diversity of tissue macrophage populations has been proposed to be the result of exposure to specialized microenvironments8,22–25. Significant reprogramming of macrophage precursors transplanted into adult tissue microenvironments has been demonstrated24,26,27, arguing for an imprinting capacity of the macrophage niche as was recently proposed28. Peripheral myeloid cells that colonize the microglial niche adopt microglia-like morphology29,30, display ATP-sensing capacity29, can promote repair following cranial irradiation19 and require TGF-β signaling for functional integration into the central nervous system (CNS)31. However, to what degree monocytes become imprinted by the microglial niche and what factors regulate this imprinting remain unknown.

In this study, we develop a novel strategy to efficiently deplete microglia, and observe competitive repopulation giving rise to a permanent mosaic of myeloid cells derived both from proliferating microglia and from brain-engrafting Ly6Chi monocytes. We provide evidence of niche imprinting, as monocyte-derived macrophages adopt both microglia gene expression and epigenetic profiles. However, monocyte-derived macrophages display a unique gene signature, giving rise to a distinct surface marker phenotype and functional profile. Our results demonstrate that both niche imprinting and myeloid origin define macrophage identity within the CNS, and this may have implications for understanding macrophage biology, disease, and therapy.

Results

Microglial depletion-repopulation in Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+

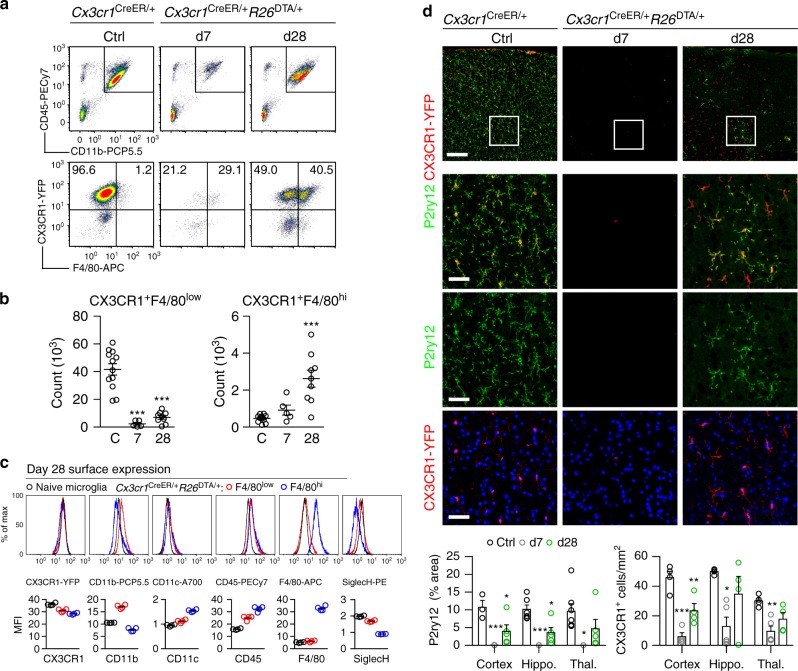

In order to make the CNS myeloid niche available we aimed to efficiently deplete microglia. To achieve both fast and efficient depletion we elected to breed mice with tamoxifen (TAM)-inducible Cre under the microglia-expressed CX3CR1-promoter (Cx3cr1CreER-EYFP mice)32 with R26DTA/+ mice33, which results in intracellular diphtheria toxin A (DTA) expression upon Cre recombination. TAM administration to Cx3r1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice resulted in ~95% loss of CD11b+CD45+Ly6C–Ly6G–CX3CR1+ microglia by day 7 (Fig. 1a, b, gating strategy Supplementary Fig. 1). We confirmed this high efficiency of depletion by immunohistochemistry using microglia-specific34 P2ry12 and CX3CR1-YFP antibodies (Fig. 1d), as well as by loss of expression of the key microglial transcripts P2ry12, Cx3cr1, and Siglech (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of depletion and repopulation of microglia in Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice. a Dot plots detailing depletion and repopulation of microglia in Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice on the indicated days after TAM administration. Top panel is gated on live singlet cells. Bottom panel is gated on CD11b+CD45+Ly6C–Ly6G–. b Quantification of CX3CR1+F4/80low and CX3CR1+F4/80hi populations by flow cytometry. n = 12, 5, 9 mice, mean ± s.e.m. ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison test. Data are pooled from three separate experiments. The experiment was repeated twice for each time point. c Surface expression by flow cytometry on repopulated F4/80low and F4/80hi cells at day 28 compared to naive microglia. Gated on CD11b+CD45+Ly6C–Ly6G–. n = 4 mice/group. Lines represent mean values. The experiment was performed twice. d Quantification of P2ry12 and CX3CR1-YFP staining in the indicated brain regions. Representative images are from the cortex. n = 3–7 mice/group, mean ± s.e.m. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison test. Scale bar top panel 200 µm, bottom three panels 50 µm. Hippo. Hippocampus. Thal. Thalamus

We analyzed additional groups of mice at day 28, and as expected from previous reports,29,30,35 we detected repopulation of the CX3CR1+ compartment. Flow cytometric analyses revealed two distinct populations within the CX3CR1+ gate that differentially expressed the F4/80 antigen (Fig. 1a), and this was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Supplementary Fig. 2B). The surface phenotype of the CX3CR1+F4/80low population overlapped with microglia from control mice, whereas the CX3CR1+F4/80hi population expressed higher levels of CD45 and lower levels of Siglec H (Fig. 1c). Siglec H has previously been suggested to be specifically expressed by microglia36. Importantly, the appearance of the F4/80hi population was not transient, since they remained 12 weeks after TAM administration (Supplementary Fig. 2D) and retained their surface marker phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 2E). In further support of repopulation by two distinct types of microglia we observed that the homogenous distribution of CX3CR1+P2ry12+ microglia in control brains was replaced by day 28 with pockets of CX3CR1+P2ry12+ and CX3CR1+P2ry12– microglia-like cells (Fig. 1d). The P2ry12 antibody has been proposed to only label microglia and not peripherally-derived myeloid cells34 and we observed that F4/80hi parenchymal macrophages were indeed P2ry12– (Supplementary Fig. 2C). qPCR analysis of whole brain further confirmed gradual increases in P2ry12, Cx3cr1 and Siglech expression from days 7 to 28 (Supplementary Fig. 2A).

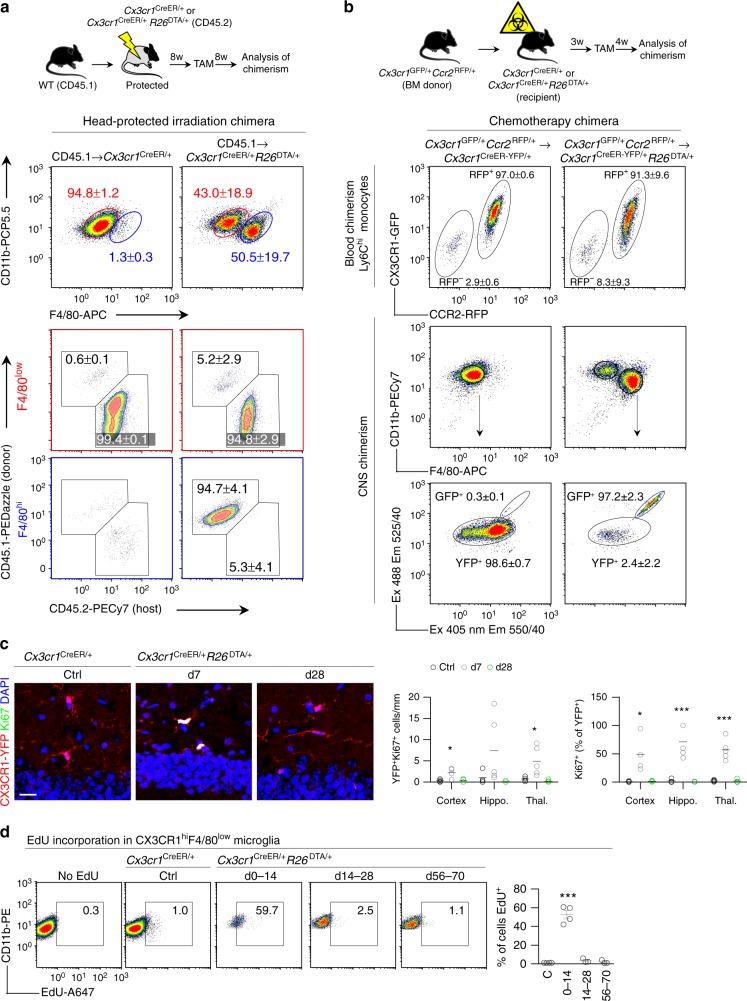

Local proliferation and infiltration repopulate the niche

Based on these data we hypothesized that the F4/80low cells represented CNS-resident microglia that had expanded following depletion and that F4/80hi cells were peripherally derived. To more conclusively address the origin of CNS-repopulating F4/80low and F4/80hi microglial cells we irradiated Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ and control Cx3cr1CreER/+ mice (CD45.2) and reconstituted them with congenic (CD45.1) BM. To limit the effects of irradiation on the ability of microglia to repopulate the niche30,37 we protected the head from irradiation. After 8 weeks of reconstitution we administered TAM and analyzed the chimeras after a further 8 weeks. Head-protected CD45.1 → Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ chimeras displayed frequencies of F4/80low and F4/80hi cells that were similar to those in non-irradiated mice (Fig. 2a). Using this system we could thus demonstrate that F4/80low cells were completely host (CD45.2)-derived and that F4/80hi cells were completely donor (CD45.1)-derived (Fig. 2a). To control for irradiation-induced damage we used a chemotherapy regimen to achieve myeloablation, a strategy that has previously been reported to lead to almost complete donor chimerism without spontaneously inducing CNS myeloid engraftment38,39. We thus produced Cx3cr1GFP/+Ccr2RFP/+ → Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ chimeras where donor and host CX3CR1+ cells could be differentiated by GFP and YFP expression, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3). Using this experimental setup we found that after depletion of microglia, practically all F4/80hi cells were GFP+ (Fig. 2b), confirming their peripheral origin.

Fig. 2.

Repopulating microglia have dual origins. a Analysis of chimerism in F4/80low and F4/80hi populations in CD45.1 chimeras. Top panel gated on CD11b+F4/80+Ly6C–Ly6G–. Bottom panels gated on F4/80low and F4/80hi as indicated. Percentages are mean ± s.d. of n = 5 mice/group. The experiment was performed twice. b Analysis of chimerism in Cx3cr1GFP/+Ccr2RFP/+ → Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ chimeras that had received busulfan chemotherapeutic for myeloablation. Successful separation of GFP+ and YFP+ populations is demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 3. Blood is gated on CD11b+Ly6G–CD115+Ly6Chi and CNS is gated on CD11b + Ly6C–. Values in plots are mean ± s.d of n = 4 and six mice. The experiment was performed once. c Quantification of CX3CR1-YFP+Ki67+ proliferating microglia in the indicated brain regions. Representative images are from the hippocampus. n = 4–5 mice/group. Lines represent mean values. ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison test. Scale bar 20 μm. d Proliferation in repopulating F4/80low microglia assessed by EdU. EdU was administered in the drinking water for 14 days during the indicated time periods after TAM. Control mice were given EdU days 0–14 after TAM. Gated on CD11b+Ly6C–Ly6G–CX3CR1+F4/80low. n = 3–4 mice/group, the experiment was performed twice. Lines represent mean values. ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison test

These results supported our hypothesis of a dual origin of CNS repopulating macrophages and further suggested the involvement of a combination of local microglial proliferation and infiltration of BM-derived precursors in order to repopulate the niche. This was supported by high frequencies of Ki67+ microglia at day 7 and their absence at day 28 (Fig. 2c). To conclusively address whether the F4/80low population arose by microglial proliferation in response to depletion we administered EdU during the repopulation phase, which confirmed a burst of proliferation in F4/80low microglia during days 0–14 (Fig. 2d).

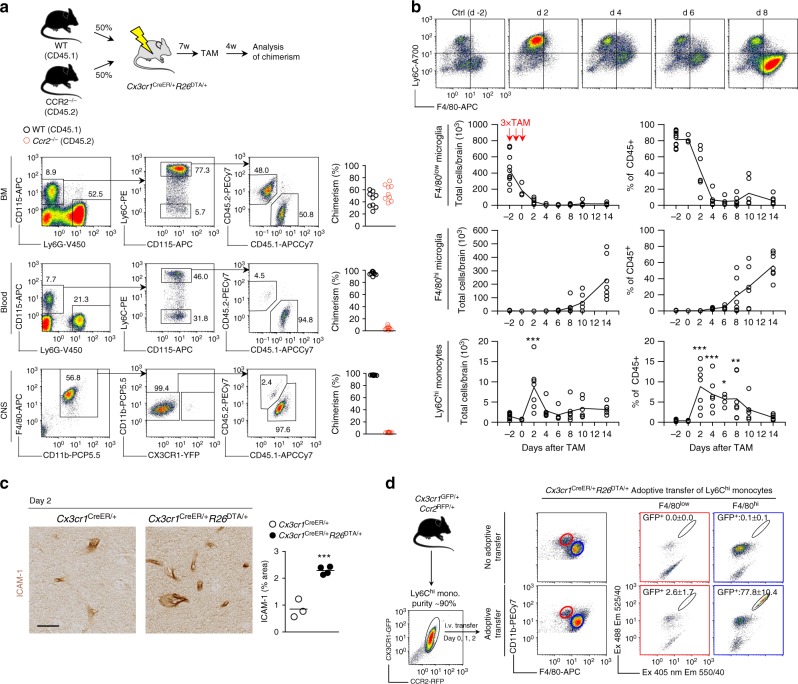

BM-derived microglial replacements are Ly6Chi monocytes

While Ly6Chi monocytes can act as precursors of many peripheral macrophage populations21, BM-derived microglia have been proposed to arise from myeloid progenitors without passing through a monocyte intermediate30,40. Furthermore, it has been suggested that blood brain barrier (BBB) disruption is a prerequisite for brain colonization by peripheral myeloid cells41. Our experiments using head protection and chemotherapy-induced myeloablation demonstrated that brain irradiation was not required for niche competition by peripheral precursors. In addition, we did not detect disruption of the BBB as a consequence of microglial depletion (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Instead, we recorded increased mRNA levels in the CNS of the chemokine receptor Ccr2 and of the monocyte chemoattractants Ccl2, Ccl3, Ccl4, and Ccl5 at day 7 (Supplementary Fig. 4B), suggesting chemotactic recruitment of Ly6Chi monocytes. In addition, we detected elevated mRNA levels of several other cytokines and chemokines at day 7, but most were back to baseline by day 14 (Supplementary Fig. 4C). This was accompanied by astrocytosis, as evidenced by both increased Gfap mRNA expression (Supplementary Fig. 4D) and GFAP immunostaining (Supplementary Fig. 2E).

To address the importance of Ly6Chi monocyte release from the BM we produced WT:Ccr2−/− → Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mixed BM chimeras (Fig. 3a) that lack CCR2–/– monocytes in the circulation (ref. 42 and Fig. 3b). We observed that the CNS F4/80hi compartment was exclusively repopulated by WT cells (Fig. 3a), demonstrating a crucial role of CCR2 in this process. Consistent with this observation, a time course experiment encompassing depletion/repopulation revealed a wave of Ly6Chi monocytes entering the brain that peaked at day 2 after TAM, prior to the establishment of the F4/80hi macrophage pool (Fig. 3b). At the peak of monocyte infiltration into the CNS we observed vascular activation in the brain, as evidenced by increased ICAM-1 staining (Fig. 3c). This suggested that peripherally derived macrophages could enter the CNS through the vasculature. Furthermore, Iba-1 staining did not reveal obvious infiltrates in meninges or choroid plexus, arguing against these anatomical areas as major infiltration sites (Supplementary Fig. 5A).

Fig. 3.

F4/80hi macrophages are derived from CCR2+Ly6Chi monocytes. a Analysis of BM, blood and CNS chimerism in WT:Ccr2–/– → Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ competitive chimeras. In all organs gated on live singlet cells. n = 9 mice. The experiment was performed twice. b Kinetic analysis of Ly6Chi monocytes in relation to F4/80low microglia and F4/80hi macrophages in the CNS during depletion in Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice. Representative flow cytometry plots are gated on CD11b+CD45hiLy6G– cells. Ly6Chi, F4/80low, and F4/80hi gated as indicated in Supplementary Fig. 1. Data is from two pooled experiments. n = 12, 3, 7, 6, 5, 7, 6, 7 mice/time point. Connecting lines represent mean values. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison test. c Activation of the cerebral vasculature as assessed by ICAM-1 staining on day 2 after TAM administration. Quantification was performed in the thalamus on n = 3 and 4 mice/group and 3 sections/mouse. Scale bar 25 µm. Lines represent mean values. ***p < 0.001 by Student’s unpaired two-tailed t-test. d Analysis of reconstitution of the F4/80low and F4/80hi compartments after adoptive transfer of 1.7–3.0 × 106 Ly6Chi monocytes/day from Cx3cr1GFP/+Ccr2RFP/+ mice into microglia-depleted Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice on days 0, 1, and 2 after TAM administration. Gated on CD11b + Ly6C–. Analysis of CNS was performed day 14 after TAM administration. Successful separation of GFP and YFP signals is demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 3. Values are mean ± s.d of 4 mice/group. The experiment was performed once

CCR2 is not an exclusive marker for Ly6Chi monocytes and can also be expressed on myeloid precursors and stem cells. However, we did not detect increased numbers of c-kit+ progenitor cells in either the CNS (Supplementary Fig. 5B) or the blood (Supplementary Fig. 5C), arguing against repopulation from BM-derived stem cell/progenitors43. Furthermore, we did not detect changes in neutrophils or lymphocyte numbers in the CNS following depletion (Supplementary Fig. 5D-E). More importantly however, adoptive transfer of purified Ly6Chi monocytes from Cx3cr1GFP/+Ccr2RFP/+ mice into microglia-depleted Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice during the peak of monocyte entry into the brain (days 0, 1, and 2) resulted in specific reconstitution of >70% of the F4/80hi compartment without contributing to the F4/80low microglial pool (Fig. 3d). Collectively, our results suggested a sequence of events whereby the remaining microglia proliferate extensively in order to refill the niche following depletion. Monocytes simultaneously infiltrate the brain and give rise to F4/80hi macrophages.

To address whether Ly6Chi monocytes enter in one wave or continuously infiltrate the brain, we administered EdU at different time points following depletion. CNS-retrieved Ly6Chi monocytes were consistently ~80% EdU+. When EdU was given during days 0–14 after TAM, the F4/80hi macrophages were also ~80% EdU+. However, when EdU is administered during days 14–28 or days 56–80 after TAM, EdU incorporation into the F4/80hi pool was not different from controls (Supplementary Fig. 5F). This indicates that F4/80hi macrophages are generated from Ly6Chi monocytes entering the brain directly following depletion.

Taken together, our data imply that in Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice the availability of an empty niche allows circulating monocytes to infiltrate the brain and to give rise to long-lived microglia-like cells.

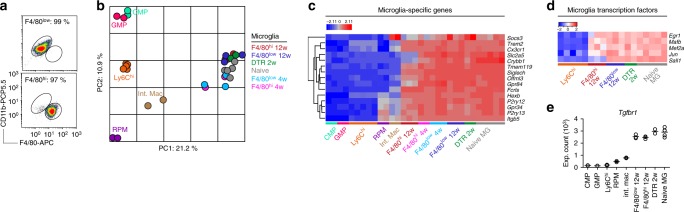

Engrafting macrophages adopt TGF-β driven transcription

Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice thus represent a useful tool to study the impact of the CNS microenvironment on peripherally-derived macrophages. To investigate whether monocyte-derived macrophages adopted microglia gene expression in the microglial niche, we depleted microglia and profiled the transcriptomes of sorted F4/80low and F4/80hi populations (Fig. 4a) after 4 and 12 weeks. In parallel we sorted Ly6Chi monocytes, common myeloid progenitors (CMP) and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMP) from the BM, as well as splenic RPM and intestinal macrophages from naive mice for comparison. Hierarchical clustering of the 1000 most variable genes in the dataset separated samples according to tissue origin (Supplementary Fig. 6). Principal component analysis (PCA) based on all genes similarly organized all CNS macrophages into one cluster (Fig. 4b) including F4/80low and F4/80hi subsets as well as naive microglia and recently proliferated microglia sorted from Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTR/+ mice, which express the diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR)30,32. This indicated a closer relationship between F4/80hi macrophages and microglia compared to their BM precursors or other tissue macrophages, which clustered separately. This was further substantiated by the fact that F4/80hi macrophages expressed several genes that have previously been described to be microglia-specific44,45 (Fig. 4c), including Fcrls, P2ry12, P2ry13, Siglech, Olfml3, and Tmem119. In addition, several transcription factors that are associated with microglia homeostasis46 were detected in F4/80hi macrophages, including Egr1, Mafb, Mef2a, and Jun, with the exception of Sall1 (ref. 37) (Fig. 4d). Several of these genes are induced by TGF-β signaling34 and we have recently demonstrated that abrogation of TGF-β signaling in monocyte-derived macrophages results in fatal demyelinating disease31. Consistently, we observed high levels of Tgfbr1 expression in both F4/80low and F4/80hi populations, which were similar to levels in naive microglia (Fig. 4e). These results indicate that monocytes adopted key microglia-specific genes subsequent to CNS engraftment.

Fig. 4.

Gene expression profile of repopulating microglia/macrophages. a FACS purities of sorted F4/80low and F4/80hi populations. b PCA of microarray expression profiles. n(biological + technical) = 2 GMP, 2 CMP, 3 + 2 Ly6Chi, 2 RPM, 2 int. mac, 3 + 2 naive microglia, 2 DTR, 3 F4/80low 4w, 3 F4/80low 12w, 2 F4/80hi 4w, 3 F4/80hi 12w. Naive microglia were sorted from Cx3cr1CreER/+ mice that received TAM. DTR microglia were sorted from Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTR/+ mice 14 days after DT administration. F4/80low and F4/80hi subsets in Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice were sorted 4 and 12 weeks after TAM administration. RPM, int. mac, CMP, GMP, and Ly6Chi monocytes were sorted from naive mice. Int. mac. intestinal macrophage. Sorting strategies are detailed in the Methods section. Each sample represents pools of 2–5 mice. c Heat map (z-scores) of expression profiles of 15 microglia-specific genes. d Heat map (z-scores) of expression profiles of microglia-specific transcription factors. e Microarray expression counts of Tgfbr1. Lines represent mean values

Repopulating cells differ transcriptionally and functionally

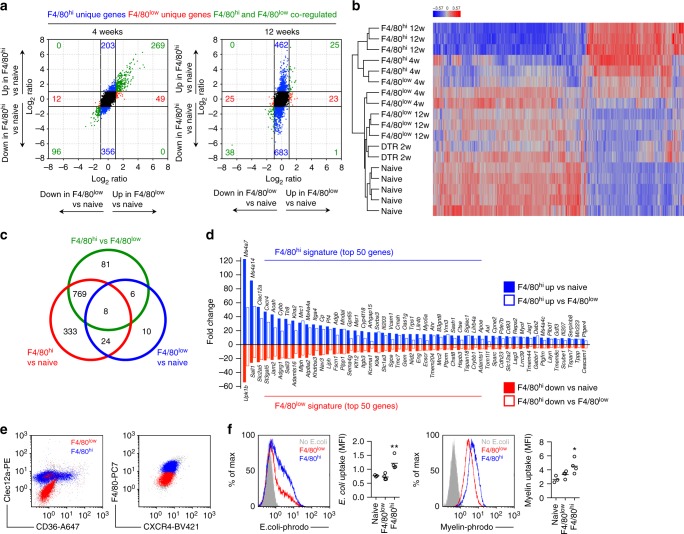

Comparison of the transcriptomes of naive microglia with other populations resulted in 4967 differentially expressed genes (>2 fold both directions, adj. p < 0.05) with Ly6Chi monocytes, 5240 with RPMs and 4370 with intestinal macrophages, respectively. F4/80low microglia 4 weeks after TAM administration differentially expressed 361 genes compared to naive microglia, and only 56 genes differed after 12 weeks (Fig. 5a). For F4/80hi macrophages the corresponding numbers were 886 and 1173, respectively (Fig. 5a). This indicated that after repopulation the F4/80low transcriptome is affected, but almost returns to baseline within 12 weeks. Conversely, F4/80hi macrophages do not completely adopt the naive microglia transcriptome. This was further supported by visualization of the genes that were differentially expressed in F4/80hi macrophages compared to naive microglia (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Monocyte-derived macrophages are transcriptionally and functionally distinct from resident and proliferating microglia. a FC/FC plots comparing differential gene expression in F4/80low and F4/80hi subsets with naive microglia, respectively, after 4 and 12 weeks. b Heat map (z-scores) of 1137 genes differentially expressed (>2 fold change both directions, adj. p < 0.05) between naive microglia and F4/80hi 12 week subsets. c Venn diagram of differential gene expression between naive microglia, F4/80low and F4/80hi subsets at 12 weeks. d F4/80hi and F4/80low gene signature; Top 50 up/down-regulated genes in F4/80hi macrophages compared to both naive microglia and F4/80low microglia at 12 weeks. e Clec12a, CD36, CXCR4 surface expression in F4/80low and F4/80hi subsets analyzed by flow cytometry. Gated on CX3CR1hiCD11b+ cells from Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice > 5 weeks after TAM. f Phagocytosis of pHrodo Red E. coli microparticles and pHrodo Red-labeled myelin in CD11b-enriched CNS cells, stained with F4/80 to gate on CX3CR1+F4/80low (red) and CX3CR1+F4/80hi (blue) subsets in Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice 5 weeks after TAM. Naive CX3CR1+F4/80low microglia were used as control. Lines represent mean values. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by Student’s paired two-tailed t-test (comparing F4/80low and F4/80hi)

To further control for the inflammatory environment occurring as a result of depletion we also compared the transcriptomes of repopulated F4/80low and F4/80hi macrophages at 12 weeks directly, these cells being sorted from the same brains and thus exposed to the same cytokine environment. This analysis revealed that of the 850 genes differentially expressed between F4/80low and F4/80hi macrophages, 769 were also differentially expressed between F4/80hi macrophages and naive microglia (Fig. 5c). Among the genes most importantly downregulated in F4/80hi macrophages compared to both naive and repopulated F4/80low microglia (Fig. 5d), we identified two Spalt-like transcription factors (Sall3 and Sall1), confirming previous reports of their specific expression in microglia24,25,34,37. Furthermore, Upk1b, Slc2a5, St3gal5, Jam2, Adgrg1 were other genes that were highly downregulated in F4/80hi macrophages (Fig. 5d). Among the genes most prominently upregulated in F4/80hi macrophages compared to both naive and repopulated F4/80low microglia (Fig. 5d), we identified C-type lectins (Clec12a, Clec4n, Mrc1) and scavenger receptors (Msr1, Cd36). Furthermore, we observed high expression of cell adhesion molecules associated with transendothelial migration (Itga4, Vcam1, Itgal), which concords with the vascular activation observed in microglia-depleted brains (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, transcription factors normally associated with monocyte development and monocyte-derived tissue macrophages (Ahr, Tfec, Runx3, Spic)24,47,48 were more highly expressed in F4/80hi macrophages. Notably, several members of the Ms4a cluster located on chromosome 19 (Ms4a7, Ms4a14, Ms4a4a, Ms4a4c, Ms4a6c, Ms4a6b) were also upregulated.

To assess if the unique gene signature in monocyte-derived macrophages resulted in functional changes, we first confirmed increased surface protein expression of Clec12a, CD36, and CXCR4 on F4/80hi macrophages compared to F4/80low microglia using flow cytometry (Fig. 5e). We next examined phagocytic capacity, since F4/80hi macrophages expressed higher levels of scavenger receptors. We observed increased uptake of both E. coli microparticles as well as fluorescently-labelled myelin by F4/80hi macrophages compared to in both naive and repopulated F4/80low microglia (Fig. 5f). Finally, we assessed their inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production capacity. Ex vivo isolated F4/80hi macrophages secreted similar or lower levels of TNF, CCL3, CCL4 or CCL5 without stimulation or following LPS stimulation compared to F4/80low microglia sorted in parallel (Supplementary Fig. 7). We did not detect production of IL-1β, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-γ or CCL2 under these conditions. Our results thus far demonstrated that monocyte-derived macrophages could adopt key components of the microglia transcriptome, but retained large transcriptional and functional differences, even after long-term integration into the CNS.

Monocyte-derived macrophages adopt microglia DNA methylome

Epigenetic reprogramming has been demonstrated in macrophages transplanted into a new tissue microenvironment24. Furthermore, specific DNA methylation changes occur during hematopoiesis and guide myeloid lineage-specific differentiation49. To investigate whether DNA methylation changes occurred in monocyte-derived macrophages we probed the DNA methylome using methylation microarrays. We and others have demonstrated that this technique can be reliably used to probe up to 19,420 CpG sites in the mouse genome50,51. We sorted F4/80low and F4/80hi macrophages after 4 and 7 weeks, respectively, and compared their DNA methylomes to naive microglia as well as to BM progenitors and RPMs. Unbiased analysis of all CpG sites organized samples into two major clusters, one containing myeloid progenitors and RPMs, the other containing all CNS-derived samples (Supplementary Fig. 8A). Detailed analysis of the CNS cluster revealed that F4/80low microglia clustered closely with naive microglia, demonstrating that their DNA methylation profile is largely conserved during repopulation (Supplementary Fig. 8A, B). Consistently, we observed only 139 differentially methylated sites between naive microglia and F4/80low microglia at 7 weeks (adj. p < 0.05). For F4/80hi macrophages and Ly6Chi monocytes these numbers were 879 and 2081 differentially methylated sites, respectively. Analysis of the most variable sites in the dataset revealed that F4/80hi macrophages adopted a methylation profile distinct from both BM progenitors and their F4/80low counterparts as these three groups occupied the extremes of a multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot visualizing the differences in the dataset (Supplementary Fig. 8B). Contrasting the DNA methylation profiles of these groups using a stringent p-value (p < 0.001) revealed 1486 sites that were differentially methylated between all groups. Visualization of these CpG sites demonstrated that F4/80hi macrophages adopted an intermediate methylation profile between Ly6Chi monocytes and F4/80low microglia (Supplementary Fig. 8C). These results are consistent with the interpretation that monocyte-derived macrophages partly adopted the DNA methylation profile of microglia following CNS niche colonization.

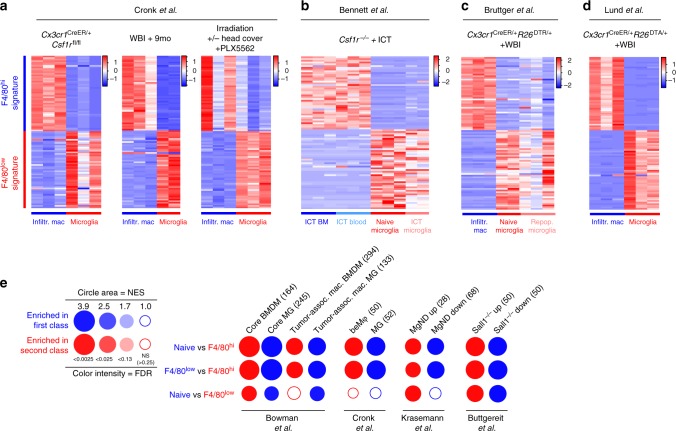

Engrafting macrophages adopt a conserved gene signature

To investigate whether our transcriptomic profiles were biased by our DT-mediated depletion system, we compared our F4/80low and F4/80hi signatures to recently published datasets comparing CNS-engrafting macrophages and microglia. Cronk et al.52 recently demonstrated that peripheral macrophages engraft the brain as a consequence of impaired microglial self-renewal, using Cx3cr1CreER/+Csf1rfl/fl mice. The authors used two additional models to at least partly replace the microglial pool with peripheral macrophages: whole-body irradiation followed by 9 month recovery, or a combination of the CSF1R antagonist PLX5562 and whole-body irradiation. We determined that our F4/80hi gene signature was highly expressed in peripherally-derived macrophages but not locally derived microglia in all three models, and that the opposite was true for our F4/80low gene signature (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Monocyte-derived macrophages adopt a conserved gene signature associated with neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. a–d Expression (z-scores) of the F4/80low and F4/80hi gene signatures from Fig. 5d in published datasets. These studies were chosen because they compared the transcriptomic profiles of CNS-infiltrating macrophages with resident microglia, with or without microglial depletion. Normalized RNA-seq expression counts were used to plot the data. WBI whole body irradiation. ICT intracerebral transplantation. e Gene set enrichment analysis visualized using BubbleGum. Color indicates the cell subset showing enrichment, and the size and color of circles represent enrichment score and significance, respectively. Numbers in parentheses denote the number of genes in the gene set. BMDM bone-marrow derived macrophage MgND neurodegeneration-associated microglia

In another recent study Bennett et al.53 used intracerebral transplantation (ICT) of microglia or peripheral immune cells into the empty microglial niche in Csf1r–/– mice, demonstrating that only cells of yolk sac origin would adopt bona fide microglial gene expression. We determined that the F4/80hi gene signature was highly expressed in microglia-like cells derived from intracerebrally transplanted BM or blood, but not in intracerebrally transplanted microglia (Fig. 6b). Conversely, the F4/80low gene signature was highly expressed in intracerebrally transplanted microglia, but not in blood or BM-derived microglia-like cells (Fig. 6b).

Taken together these results are consistent with the idea that monocyte-derived macrophages adopt a unique and reliable gene signature as a consequence of encountering the CNS microenvironment. In further support of this conclusion, our F4/80hi and F4/80low gene signatures were conserved in engrafting macrophages and naive microglia reported in two additional studies, one by Bruttger et al.30 (Fig. 6c) and one by ourselves31 (Fig. 6d), both using irradiation combined with microglia depletion.

Next we performed gene set enrichment analysis on the transcriptomic profiles of F4/80low and F4/80hi macrophages and naive microglia and visualized their pairwise comparisons using BubbleGum54. We initially focused on studies comparing brain-engrafting macrophages with microglia. Overall, the gene sets identified in brain-engrafting macrophages were highly enriched in F4/80hi macrophages, and gene sets identified in CNS resident microglia were enriched in F4/80low and naive microglia (Fig. 6e). This analysis used gene sets from a study comparing the transcriptomic profiles of peripherally-derived and microglia-derived tumor-associated macrophages in glioma55, as well as the signature genes in peripherally-derived macrophages (beMφ-50) and microglia (Mg-52) described by Cronk et al.52 (Fig. 6e). In addition, F4/80hi macrophages displayed enrichment of a common gene signature identified in microglia isolated from mouse models of AD, ALS, and MS, termed neurodegeneration-associated microglia (MGnD)56 (Fig. 6e). Furthermore, genes differentially expressed in Sall1 deficient microglia37 were also highly enriched in F4/80hi macrophages (Fig. 6e), which was of interest since F4/80hi macrophages did not express Sall1. Taken together our analysis demonstrates that the F4/80low and F4/80hi gene signatures are conserved across several experimental systems and are unlikely to be biased by our microglia depletion system.

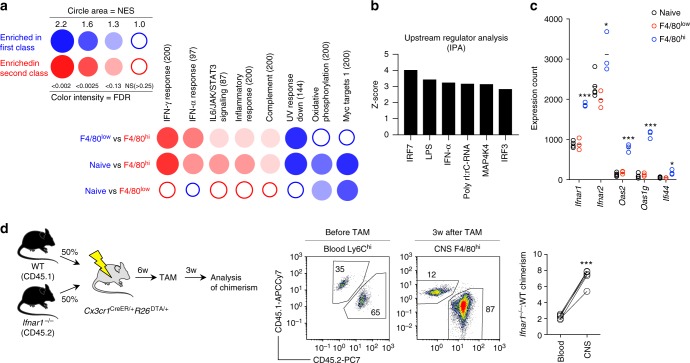

Type I IFNs regulate macrophage phenotype and colonization

To further probe potential regulators of peripheral macrophage engraftment, we performed gene set enrichment analysis on the transcriptional profile of F4/80low and F4/80hi macrophages. We tested for enrichment of the hallmark gene sets, which are 50 well-defined gene sets that convey specific biological states or processes57 and used BubbleGum to visualize the results. This analysis demonstrated that responses to IFN-γ and to IFN-α were the most significantly enriched biological processes in F4/80hi macrophages (Fig. 7a). This result was further supported by ingenuity pathway analysis performed on the genes differentially expressed in F4/80hi macrophages (>2 fold change both directions compared to F4/80low microglia, adj. p < 0.05), which predicted several molecules related to interferon (IFN) signaling (IRF7, IRF3, IFN-α) to most potently affect the F4/80hi gene signature (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, F4/80hi macrophages expressed higher levels of the receptors for type I IFNs, Ifnar1, and Ifnar2, as well as several IFN stimulated genes, including Oas1g and Oas2 and Ifi44 (Fig. 7c). These analyses identified type I IFNs as a possible microenvironmental factor shaping F4/80hi macrophages. CNS-derived type I IFNs have been demonstrated to regulate infiltrating macrophages during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis58. We thus asked whether type I IFNs regulate colonization of the microglial niche by monocyte-derived macrophages. To test this experimentally we produced Ifnar1−/−:WT → Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ competitive chimeras, which resulted in approximately 65/35% (Ifnar1–/–:WT) chimerism in blood Ly6Chi monocytes. We then depleted microglia using TAM administration and analyzed chimerism in the F4/80hi compartment after 3 weeks. We observed that Ifnar1–/– cells had a competitive advantage over WT cells in repopulating the F4/80hi compartment, resulting in approximately 85/15% (Ifnar1–/–:WT) chimerism (Fig. 7d). This indicates that type I IFNs have an inhibitory effect on microglial niche colonization.

Fig. 7.

Type I IFNs regulate niche colonization. a Analysis of enrichment of hallmark gene sets visualized using BubbleGum. Color indicates the cell subset showing enrichment, and the size and color of circles represent enrichment score and significance, respectively. b Top activated upstream regulators using ingenuity pathway analysis. c Microarray expression counts of type I IFN receptors and response genes. Lines represent mean values. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 by Student’s unpaired two-tailed t-test comparing F4/80low and F4/80hi. d Analysis of chimerism in WT:Ifnar1–/– competitive chimeras before TAM administration (blood) or 3 weeks after TAM (CNS). Blood is gated on CD11b+SSClowLy6Chi monocytes and CNS on CD11b+F4/80hi. n = 4 mice. The experiment was performed once. ***p < 0.001 by Student’s paired two-tailed t-test

Discussion

Microglia are derived from yolk-sac progenitors that arise early during embryogenesis and that colonize the primitive brain1. The formation of the BBB is believed to halt any further colonization of the brain by primitive macrophages during embryogenesis. It is now established that microglia self-maintain throughout adulthood with little or no input from peripheral precursors1–3, this occurring as a stochastic process of microglial proliferation59,60. During certain conditions, however, as demonstrated herein and by others29,30,52, myeloid cells can colonize the brain and give rise to long-lived microglia-like cells. Understanding how monocytes take over the microglia niche is not only of biological importance but also of therapeutic interest, since replacement of mutant microglia with wild-type BM-derived cells has been proposed for neurological disorders such as ALS61,62 and Nasu-Hakola disease63. The current study was undertaken to characterize this process and its underlying mechanisms.

In this paper we report that after depletion of microglia using Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice, the microglial niche is simultaneously repopulated by a combination of surviving resident microglia and CNS-infiltrating monocytes. While previous reports have described microglial proliferation or peripheral myeloid cell engraftment to occur as a consequence of microglia depletion29,30,35,52,64–66, our report is the first that demonstrates that these processes can occur simultaneously and cooperatively to repopulate an empty microglial niche, effectively showing that these processes are not mutually exclusive. Using head-shielded chimeras and adoptive transfer, we could demonstrate that brain irradiation or stem cell release into the circulation were not prerequisites for peripheral macrophage repopulation in our model. Furthermore, monocyte engraftment occurred without BBB breakdown. However, the absence of microglia caused a transient cytokine storm which likely led to the observed vascular activation, coinciding with Ly6Chi monocyte entry into the CNS. Future studies should address the importance of this inflammation in attracting monocytes into the CNS.

The fact that proliferating microglia and engrafting macrophages adopted distinct surface marker expressions (F4/80low and F4/80hi, respectively) could be utilized to sort these populations and perform transcriptional, epigenetic, and functional profiling. One obvious benefit of our experimental paradigm is that we could thus control for the effect of the CNS environment during depletion/repopulation, since F4/80low and F4/80hi cells were sorted from the same brains. Consequently, our first observation was that the global gene expression profile of CNS-engrafting macrophages was more similar to microglia than to other tissue-resident macrophages or their Ly6Chi monocyte precursors. Consistent with this we observed upregulation of microglia-specific genes including P2ry12, Fcrls, Siglech, and Tmem119 in monocyte-derived macrophages, as well as microglia-expressed transcription factors Mafb and Mef2a. In addition, we observed a similar trend for the DNA methylation profile. In concordance with a recent proposal,28 we interpret this as imprinting of monocyte-derived macrophages by the microglial niche. Importantly, however, Sall1, a transcription factor regulating microglia identity37 was not expressed in monocyte-derived macrophages, whose transcriptional profile displayed enrichment of genes expressed in Sall1–/– microglia. Enforced expression of Sall1 in CNS-engrafting macrophages would be an important experiment to address the requirement for Sall1 expression in coordinating the bona fide microglia gene expression program.

Our F4/80low and F4/80hi gene signatures consistently overlapped with the published transcriptional profiles of microglia and engrafting macrophages across several models of microglia depletion, ruling out the possibility that they were biased by the nature of our microglia depletion model. Rather, the conserved gene signature observed in F4/80low and F4/80hi subsets instead indicates that these gene sets represent fixed ontogeny-dependent expression programs. We consistently observed a high similarity between our F4/80hi gene signature and that described in microglia-like cells derived from intracerebral transplantation of cells of hematopoietic stem cell origin into an empty microglial niche53, including high expression of Ms4a7, Clec12a, and Apoe. This was in contrast to cells of yolk-sac origin53, which displayed higher expression of microglia-specific genes, including Sall1, Sall3, and Slc2a5.

Why do monocyte-derived macrophages not fully adopt the microglia gene expression program despite being situated in the same organ space? One possibility is that microglial education occurring during development46,67 induces a transcriptional and epigenetic program not obtainable by monocyte-derived macrophages that enter the adult brain. Alternatively, monocytes may contain unique epigenetic programming from the BM. In concordance with this notion we observed that the DNA methylation pattern of monocyte-derived macrophages was frozen between BM and microglia states. Interestingly, Lavin et al. have demonstrated considerable variation in the ability of BM-derived transplants to recover tissue macrophage-specific chromatin states. Depending on the tissue, transplant-derived macrophages isolated from the liver, spleen, lung or peritoneum adopted 47–92% of tissue-specific enhancer regions24. Such variability could potentially explain why monocytes do not fully adopt microglia gene expression, which contrasts to monocytes repopulating Kupffer cell68 or alveolar macrophage26 niches following experimental depletion.

Finally, to identify potential regulators of monocyte engraftment and repopulation we performed gene set enrichment and ingenuity pathway analyses, which identified a robust IFN signature in monocyte-derived macrophages. Importantly, type I IFNs regulate the phenotype of both CNS resident and infiltrating myeloid cells. Exaggerated type I IFN signaling in microglia leads to their activation and engulfment of synapses, manifesting as neurological symptoms in lupus-prone mice69. However, local production of type I IFNs in the CNS suppress autoimmune neuroinflammation by modulating CNS engrafting macrophages58. We used a competitive chimera approach to address the requirement for IFNAR signaling in monocyte-derived macrophages in repopulating the microglial niche, and demonstrated that type I IFNs impair this process. Interestingly, this contrasts with our recent observation that TGF-β signaling promotes microglia niche colonization31. Future studies should aim to identify the crucial microenvironmental factors shaping CNS engrafting monocytes and how they may be manipulated in order for monocytes to completely adopt microglia identity.

Methods

Mice

All mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at Karolinska Institutet, in accordance with national animal care guidelines. All animal experiments were approved by the appropriate ethical review board (Stockholms djurförsöksetiska nämnd). Cx3cr1CreER-EYFP, R26DTR, R26DTA, CD45.1 were originally obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Cx3cr1GFP/+Ccr2RFP/+, and Ccr2–/– (RFP/RFP) mice were a gift from Klas Blomgren at Karolinska Institutet. Ifnar1–/– were originally obtained from Ulrich Kalinke. Experiments were started when mice were 6–12 weeks.

In vivo treatments

Tamoxifen administration: Tamoxifen (TAM; Sigma) was suspended in corn oil at 75 °C and 5 mg (200 µl) was unless otherwise specified administered subcutaneously (s.c.) on three consecutive days.

Diphtheria toxin administration: Microglia were depleted in Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTR/+ by two subcutaneous doses of 5 mg TAM separated by 48 h followed 3 weeks later by three daily doses of 25 ng/g diphtheria toxin, given intraperitoneally.

EdU administration: Mice were fed for 2 weeks with EdU in drinking water (0.2 mg/ml + 1% sucrose) from days 0–14 or 14–28 after TAM injections. The solution was protected from light at all times and changed once per week. EdU was detected by flow cytometry according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen).

Evans Blue administration: To assess BBB integrity mice were injected i.p with 200 μl 2% Evan’s Blue solution (Sigma). Twenty-four hours later mice were perfused and brains collected, weighed and homogenized in 1 ml 3.05 M trichloroacetic acid. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 × g and the supernatant mixed 1:3 with 95% ethanol. Samples were excited at 625 nm and emission read at 680 nm using a Glomax fluorescence plate reader.

Generation of BM chimeras

Mice were irradiated with 9.5 Gray using an X-RAD 320 irradiation source (0.95Gray/minute) with a 20 × 20 cm irradiation field. Head protection was accomplished by retaining mice under isofluorane anaesthesia and placing the head (from the neck up) outside the field of irradiation. Mice were monitored throughout the irradiation period to make sure the heads stayed outside the field (the irradiation source is equipped with a lamp to visualize the irradiation field). Mice were reconstituted on the same day with 2–5 × 106 BM cells by tail vein injection. Mice were considered reconstituted and used for experiments 6–8 weeks later. Head-protected mice generally resulted in 50–80% chimerism.

Chemotherapy

Myeloablation using chemotherapy was performed by administering 20 mg/kg Busulfan (Sigma) by i.p. injection on three consecutive days. Busulfan was solubilized in DMSO and diluted to 5 mg/ml in PBS. On the fourth day 12–14 × 106 BM cells were given by tail vein injection. This procedure resulted in 80–98% chimerism.

Adoptive transfer

Ly6Chi monocytes were isolated with ~90% purity using negative selection MACS beads (monocyte isolation kit, Miltenyi) from the femurs and tibias of Cx3cr1GFP/+ Ccr2RFP/+ mice. 1.7–3.0 × 106 cells/day were transferred by tail vein injection into Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTA/+ mice on day 0, 1, and 2 after TAM. Mice were sacrificed on day 14 for analysis of reconstitution.

Preparation of single cell suspensions

Mice were sacrificed by injecting 100 µl pentobarbital (i.p.). When applicable, blood was collected from the right ventricle prior to perfusion. Mice were perfused with ice- cold PBS and organs dissected. CNS cells were prepared by enzymatic digestion using Collagenase D (1 mg/ml, Roche) and DNAse I (0.2 mg/ml, Roche) or Neural Tissue Dissociation Kit T (Miltenyi Biotec). Myelin was removed using 38% Percoll.

Samples of 100–200 μl blood were collected into tubes containing EDTA, lysed in ACK buffer and centrifuged. The pellet was resuspended in PBS and used for staining. Spleen cell suspensions were prepared by mechanical dissociation in PBS using 40 μm strainers. BM cells were prepared by flushing femurs with PBS. Spleen and BM preparations were treated with ACK buffer to lyse RBCs. Cell suspensions from the lamina propria of the small intestine were prepared by mechanical dissociation followed by enzymatic digestion using DNAse and Liberase. Cells were then purified using a 40/60% Percoll gradient and isolated at the interphase. Cells were counted using a Scepter counter (Millipore) or by flow cytometry using CountBright absolute counting beads (Thermo Fisher).

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were plated in 96-well V-bottom plates and stained at 4 °C. Dead cells were removed using LIVE/DEAD Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen). The following antibodies were used: CD3 (17A2, Biolegend), CD11b (M1/70, Biolegend), CD11c (N418, Biolegend), CD16/32 (93, Biolegend), CD34 (HM34, Ebioscience), CD36 (MF3, Bio-Rad), CD45 (30F11, Biolegend), CD45.1 (A20, Biolegend), CD45.2 (104, Biolegend), CD115 (AFS98, Biolegend), CD206 (MR5D3, BD), B220 (RA3-6B2, Biolegend), c-kit (ACK2, Biolegend), Clec12a (5D3CLEC12A, Biolegend), CXCR4, (2B11, BD), F4/80 (BM8, Biolegend), Ly-6C (HK1.4, Biolegend), Ly-6G (1A8, BD Biosciences), MHCII (M5/114.15.2, Biolegend), NK1.1 (PK136, BD Biosciences). Sca-1 (D7, Biolegend), Siglec H (551, Biolegend), TER119, (TER-119, Biolegend). Cells were acquired using a Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and analyzed using Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter). GFP and YFP signals in chemotherapy and adoptive transfer experiments were separated by exciting GFP using the 405-nm violet laser using the 550/40-nm emission filter.

Cell sorting

Cells were sorted using a BD influx cell sorter using the following sorting strategies. F4/80low microglia (CD11b+CX3CR1hiF4/80low), F4/80hi macrophages (CD11b+CX3CR1hiF4/80hi), Naive microglia and Cx3cr1CreER/+R26DTR/+ (DTR) microglia (CD11b+CX3CR1hi) with >97% purity. CMP (Lin–ckit+sca1–CD34+CD16/32int), GMP (Lin–ckit+sca1–CD34+CD16/32hi), cMoP (Lin–ckit+CD115+Ly6C+CD11b–), Ly6Chi monocytes were sorted from BM using the monocyte isolation kit (BM, Miltenyi Biotec) with ~95% purity. Spleen RPMs were sorted based on their superparamagnetic properties using MACS columns with ~95% purity or further FACS sorted (Dead-CD45+F4/80hi). Intestinal macrophages were pre-sorted using CD11b-beads (Miltenyi) and then as CX3CR1hiCD64+MHCII+.

Microarray analysis

For RNA preparation cells were sorted into a solution of RNA later (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA was prepared using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). RNA quality and integrity was assessed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent). All samples included had high quality (RIN = 7–10). cDNA preparation, hybridization and scanning were performed at the Array and Analysis Facility, Science for Life Laboratory at Uppsala Biomedical Center (BMC). 0.5–10 ng of total RNA from each sample was used to generate amplified and biotinylated sense-strand cDNA from the entire expressed genome according to the GeneChip WT Pico Reagent Kit User Manual (Affymetrix). GeneChip Mouse Gene 2.1 ST Arrays were hybridized for 16 h in a 45 °C incubator, washed and stained and finally scanned at the GeneTitan Multi-Channel Instrument, according to the GeneTitan Instrument User Guide for Expression Arrays Plates (Affymetrix).

Bioinformatic analyses

PCA and heatmaps were produced using Partek Genomics Suite (Partek).

Gene Set Enrichment analysis was performed and visualized using BubbleGum using standard settings. Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA, Qiagen) was used to analyze upstream regulators.

DNA methylation analysis

DNA was prepared using QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen). DNA methylation analysis was performed using Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip (Illumina) with ≥250 ng input DNA at the Bioinformatics and Expression Analysis (BEA) core facility, Karolinska Institutet. EPIC probes (50-mer oligonucleotides) were mapped to GRCm38/mm10 using Bismark (version 0.14.5) with default settings. A total of 19,420 probes were identified as unique hits (conserved between human and mouse) and used for downstream analysis. Data was analyzed using the ChAMP package, probes were filtered for mapping probes with 17,633 probes passing detection cutoff, and subsequently SWAN normalized. Differential probes were identified using Limma (p < 0.01) and clustering was preformed using PCA analysis.

qPCR

Hemibrains or coronal brain sections were homogenized in RLT-buffer (Qiagen) containing beta-mercaptoethanol (14.3 M, 10 µl/ml, Sigma) and RNA prepared using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). qPCR was performed with SYBR green reaction (Bio-Rad). All expression levels are reported relative to Hprt or Hprt and Gapdh. Primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry

PBS-perfused brains were immersion-fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h, then sucrose protected (20%) for at least 24 h and then embedded in OCT cryomount (Histolab) and frozen in isopentane. Sections were stained using the following antibodies: Iba-1 (Wako), F4/80-biotin (Cl:A3-1, AbD Serotec), GFP (Abcam, ab13970), GFAP (Abcam, ab7260), Ki67 (Abcam, ab15580), P2ry12 (generated by Dr. O. Butovsky), ICAM-1 (Abcam, ab119871). P2ry12-staining and CX3CR1+/Ki67+ cell counting was performed Pannoramic viewer and Histoquant software (3D histech).

Ex vivo experiments

Phagocytosis: Phagocytosis was assessed in F4/80low and F4/80hi cells by pre-sorting CNS cells using CD11b-microbeads (Miltenyi) and staining with F4/80 and CD11b antibodies. Cells were then incubated 1 h with pHrodo Red E. coli microbeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or pHrodo Red-labeled myelin. Myelin was isolated from mouse brains/spinal cords using a sucrose gradient and labeled with pHrodo Red according to manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cytokine secretion: Sorted microglia were cultured overnight in DMEM containing 10% FCS ± 100 ng/ml LPS (E. coli O111:B4, Sigma). Culture supernatants were analyzed for levels of TNF, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-12p70, CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5 in two multiplex-panels using cytometric bead array (CBA) according to manufacturer’s instructions (BD biosciences).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Annika van Vollenhoven for FACS sorting. We thank Elisabeth Qvist for animal care-taking and Michelle Gustafsson for performing tail vein injections. We would like to acknowledge the Array and Analysis Facility, Science for Life Laboratory at Uppsala Biomedical Center (BMC) for performing microarray analysis. DNA methylation analysis was performed at the Bioinformatics and Expression Analysis core facility, Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge. Figures containing mice graphics (Figs. 2, 3 and 7) were produced using Servier Medical Art (http://smart.servier.com/). This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation (Alzheimerfonden, R.A.H.), the Swedish Research Council (R.A.H. and M.J.), the Swedish Brain Foundation (Hjärnfonden, R.A.H.), Alltid Litt Sterkere (R.A.H.) and a fellowship from the Margaretha af Ugglas Foundation (L.K.).

Author contributions

H.L. conceived the study with R.A.H., X.M.Z., and R.P. H.L., R.P., R.A.H., X.M.Z., O.B. designed experiments. H.L., M.P., R.P., D.G., and X-M.Z. performed most experiments and analyzed the data. Additional experiments/data analysis or design were performed by: J.H. (flow cytometry) L.K. (DNA methylation) E.E., M.N., M.J. (bioinformatic analyses) A.E., E.N., A.K.Ö. (Ifnar1 experiments). H.L. wrote the paper which all co-authors edited.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Microarray and DNA methylation array raw data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus data repository under accession number GSE121409 and GSE121483, respectively. A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file. The source data underlying Figs. 5d, 6a–e, 7a, b are provided as source data files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-07295-7.

References

- 1.Ginhoux F, et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz C, et al. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2012;336:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashimoto D, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013;38:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yona S, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Furth R, et al. The mononuclear phagocyte system: a new classification of macrophages, monocytes, and their precursor cells. Bull. World Health Organ. 1972;46:845–852. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoeffel G, et al. C-Myb+erythro-myeloid progenitor-derived fetal monocytes give rise to adult tissue-resident macrophages. Immunity. 2015;42:665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez Perdiguero E, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature. 2015;518:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature13989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mass E, et al. Specification of tissue-resident macrophages during organogenesis. Science. 2016;353:aaf4238–aaf4238. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamoutounour S, et al. Origins and functional specialization of macrophages and of conventional and monocyte-derived dendritic cells in mouse skin. Immunity. 2013;39:925–938. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bain CC, et al. Constant replenishment from circulating monocytes maintains the macrophage pool in the intestine of adult mice. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:929–937. doi: 10.1038/ni.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldmann T, et al. Origin, fate and dynamics of macrophages at central nervous system interfaces. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:797–805. doi: 10.1038/ni.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molawi K, et al. Progressive replacement of embryo-derived cardiac macrophages with age. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:2151–2158. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mossadegh-Keller N, et al. Developmental origin and maintenance of distinct testicular macrophage populations. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:2829–2841. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immunity. 2016;44:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heidt T, et al. Differential contribution of monocytes to heart macrophages in steady-state and after myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 2014;115:284–295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blériot C, et al. Liver-resident macrophage necroptosis orchestrates type 1 microbicidal inflammation and type-2-mediated tissue repair during bacterial infection. Immunity. 2015;42:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machiels B, et al. A gammaherpesvirus provides protection against allergic asthma by inducing the replacement of resident alveolar macrophages with regulatory monocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:1310–1320. doi: 10.1038/ni.3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mildner A, et al. Microglia in the adult brain arise from Ly-6ChiCCR2+monocytes only under defined host conditions. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1544–1553. doi: 10.1038/nn2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietrich J, et al. Bone marrow drives central nervous system regeneration after radiation injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2018;128:281–293. doi: 10.1172/JCI90647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guilliams M, et al. Dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages: a unified nomenclature based on ontogeny. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:571–578. doi: 10.1038/nri3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonnardel J, Guilliams M. Developmental control of macrophage function. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018;50:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue-specific signals control reversible program of localization and functional polarization of macrophages. Cell. 2014;157:832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosas M, et al. The transcription factor Gata6 links tissue macrophage phenotype and proliferative renewal. Science. 2014;344:645–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1251414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavin Y, et al. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell. 2014;159:1312–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gosselin D, et al. Environment drives selection and function of enhancers controlling tissue-specific macrophage identities. Cell. 2014;159:1327–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van de Laar L, et al. Yolk sac macrophages, fetal liver, and adult monocytes can colonize an empty niche and develop into functional tissue-resident macrophages. Immunity. 2016;44:755–768. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takata K, et al. Induced-pluripotent-stem-cell-derived primitive macrophages provide a platform for modeling tissue-resident macrophage differentiation and function. Immunity. 2017;47:183–198. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guilliams M, Scott CL. Does niche competition determine the origin of tissue-resident macrophages? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17:451–460. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varvel NH, et al. Microglial repopulation model reveals a robust homeostatic process for replacing CNS myeloid cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:18150–18155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210150109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruttger J, et al. Genetic cell ablation reveals clusters of local self-renewing microglia in the mammalian central nervous system. Immunity. 2015;43:92–106. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lund H, et al. Fatal demyelinating disease is induced by monocyte-derived macrophages in the absence of TGF-β signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0091-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parkhurst CN, et al. Microglia promote learning-dependent synapse formation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Cell. 2013;155:1596–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu S, Wu Y, Capecchi MR. Motoneurons and oligodendrocytes are sequentially generated from neural stem cells but do not appear to share common lineage-restricted progenitors in vivo. Development. 2006;133:581–590. doi: 10.1242/dev.02236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butovsky O, et al. Identification of a unique TGF-β–dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;17:131–143. doi: 10.1038/nn.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elmore MRP, et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor signaling is necessary for microglia viability, unmasking a microglia progenitor cell in the adult brain. Neuron. 2014;82:380–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiu IM, et al. A. Cell Rep. 2013;4:385–401. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buttgereit A, et al. Sall1 is a transcriptional regulator defining microglia identity and function. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:1397–1406. doi: 10.1038/ni.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lampron A, Lessard M, Rivest S. Effects of myeloablation, peripheral chimerism, and whole-body irradiation on the entry of bone marrow-derived cells into the brain. Cell Transplant. 2012;21:1149–1159. doi: 10.3727/096368911X593154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis CAB, et al. Myelosuppressive conditioning using busulfan enables bone marrow cell accumulation in the spinal cord of a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, McNagny KM, Rossi FMV. Infiltrating monocytes trigger EAE progression, but do not contribute to the resident microglia pool. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:1142–1149. doi: 10.1038/nn.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waisman Ari, Ginhoux Florent, Greter Melanie, Bruttger Julia. Homeostasis of Microglia in the Adult Brain: Review of Novel Microglia Depletion Systems. Trends in Immunology. 2015;36(10):625–636. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holtman IR, et al. Induction of a common microglia gene expression signature by aging and neurodegenerative conditions: a co-expression meta-analysis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2015;3:31. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0203-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Si Y, Tsou CL, Croft K, Charo IF. CCR2 mediates hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell trafficking to sites of inflammation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:1192–1203. doi: 10.1172/JCI40310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wes PD, Holtman IR, Boddeke EWGM, Möller T, Eggen BJL. Next generation transcriptomics and genomics elucidate biological complexity of microglia in health and disease. Glia. 2015;64:197–213. doi: 10.1002/glia.22866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crotti A, Ransohoff RM. Microglial physiology and pathophysiology: insights from genome-wide transcriptional profiling. Immunity. 2016;44:505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matcovitch-Natan O, et al. Microglia development follows a stepwise program to regulate brain homeostasis. Science. 2016;353:aad8670–aad8670. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hettinger J, et al. Origin of monocytes and macrophages in a committed progenitor. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:821–830. doi: 10.1038/ni.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haldar M, et al. Heme-mediated SPI-C induction promotes monocyte differentiation into iron-recycling macrophages. Cell. 2014;156:1223–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ji H, et al. Comprehensive methylome map of lineage commitment from haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2010;467:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nature09367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong NC, et al. Exploring the utility of human DNA methylation arrays for profiling mouse genomic DNA. Genomics. 2013;102:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Needhamsen M, et al. Usability of human Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip for mouse DNA methylation studies. BMC Bioinforma. 2017;18:486. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1870-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cronk JC, et al. Peripherally derived macrophages can engraft the brain independent of irradiation and maintain an identity distinct from microglia. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215:1627–1647. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bennett FC, et al. A combination of ontogeny and CNS environment establishes microglial identity. Neuron. 2018;98:1170–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spinelli L, Carpentier S, Montanana Sanchis F, Dalod M, Vu Manh TP. BubbleGUM: automatic extraction of phenotype molecular signatures and comprehensive visualization of multiple Gene Set Enrichment Analyses. BMC Genom. 2015;16:814. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bowman RL, et al. Macrophage ontogeny underlies differences in tumor-specific education in brain malignancies. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2445–2459. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krasemann S, et al. The TREM2-APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity. 2017;47:566–581. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liberzon A, et al. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prinz M, et al. Distinct and nonredundant in vivo functions of IFNAR on myeloid cells limit autoimmunity in the central nervous system. Immunity. 2008;28:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Askew K, et al. Coupled proliferation and apoptosis maintain the rapid turnover of microglia in the adult brain. Cell Rep. 2017;18:391–405. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tay TL, et al. A new fate mapping system reveals context-dependent random or clonal expansion of microglia. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:793–803. doi: 10.1038/nn.4547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beers DR, et al. Wild-type microglia extend survival in PU.1 knockout mice with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2006;103:16021–16026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee JC, et al. Replacement of microglial cells using Clodronate liposome and bone marrow transplantation in the central nervous system of SOD1G93A transgenic mice as an in vivo model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;418:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cartier N, Lewis CA, Zhang R, Rossi FMV. The role of microglia in human disease: therapeutic tool or target? Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:363–380. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1330-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prokop S, et al. Impact of peripheral myeloid cells on amyloid-β pathology in Alzheimer’s disease-like mice. J. Exp. Med. 2015;212:1811–1818. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang Y, et al. Repopulated microglia are solely derived from the proliferation of residual microglia after acute depletion. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:530–540. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang Y, et al. Dual extra-retinal origins of microglia in the model of retinal microglia repopulation. Cell Discov. 2018;4:431. doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0011-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thion MS, et al. Microbiome influences prenatal and adult microglia in a sex-specific manner. Cell. 2018;172:500–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scott CL, et al. Bone marrow-derived monocytes give rise to self-renewing and fully differentiated Kupffer cells. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10321. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bialas AR, et al. Microglia-dependent synapse loss in type I interferon-mediated lupus. Nature. 2017;546:539–543. doi: 10.1038/nature22821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Microarray and DNA methylation array raw data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus data repository under accession number GSE121409 and GSE121483, respectively. A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file. The source data underlying Figs. 5d, 6a–e, 7a, b are provided as source data files.