Key Points

Question

Is an exercise regimen adjuvant to compression associated with increased venous leg ulcer healing compared with compression alone?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis including 5 randomized clinical trials comprising 190 patients with venous leg ulceration, exercise was associated with increased healing rates by 14 additional cases per 100 patients in exercise groups compared with control groups. Progressive resistance exercise plus prescribed physical activity was associated with increased healing by 27 additional cases per 100 patients in exercise groups compared with control groups.

Meaning

Daily sets of heel raises plus physical activity (eg, walking at least 3 times per week) may be an effective adjuvant to compression for treating venous leg ulceration.

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 5 clinical trials examines the association of different exercise interventions with venous leg ulceration healing when used as an adjuvant to any form of compression.

Abstract

Importance

Exercise is recommended as an adjuvant treatment for venous leg ulceration (VLU) to improve calf muscle pump function. However, the association of exercise with VLU healing has not been properly aggregated, and the effectiveness of different exercise interventions has not been characterized.

Objective

To summarize the association of different exercise interventions with VLU healing when used as an adjuvant to any form of compression.

Data Sources

The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and SCOPUS databases were searched through October 9, 2017.

Study Selection

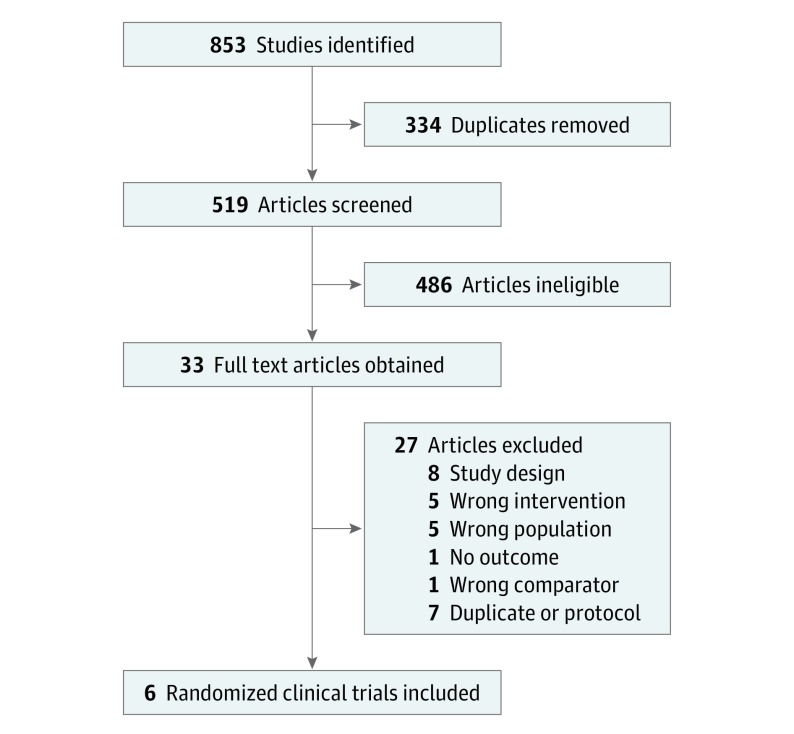

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of any exercise compared with no exercise in participants with VLU were included, where compression was used as standard therapy and a healing outcome was reported. Independent title screening and full text review by 2 authors (A.J., J.S.) with appeal to a third author (J.P.) if disagreement was unresolved. Of the 519 articles screened, a total of 6 (1.2%) studies met the inclusion criteria for systematic review, including 5 for meta-analysis.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Independent quality assessment for Cochrane risk of bias and data extraction by 2 authors with appeal to third author if disagreement unresolved (PRISMA). Data pooled using fixed effects model.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The a priori primary outcome was any healing outcome (proportion healed, time to healing, or change in ulcer area). Secondary outcomes (adverse events, costs, and health-related quality of life) were only collected if a primary outcome was reported.

Results

Six RCTs were identified and 5 (190 participants) met inclusion criteria for meta-analysis. The exercise interventions were progressive resistance exercise alone (2 RCTs, 53 participants) or combined with prescribed physical activity (2 RCTs, 102 participants), walking only (1 RCT, 35 participants), or ankle exercises (1 RCT, 40 participants). Overall, exercise was associated with increased VLU healing at 12 weeks although the effect was imprecise (additional 14 cases healed per 100 patients; 95% CI, 1-27 cases per 100; P = .04). The combination of progressive resistance exercise plus prescribed physical activity appeared to be most effective, again with imprecision (additional 27 cases healed per 100 patients; 95% CI, 9-45 cases per 100; P = .004).

Conclusions and Relevance

The evidence base may now be sufficiently suggestive for clinicians to consider recommending simple progressive resistance and aerobic activity to suitable patients with VLU while further research is produced.

Introduction

Venous leg ulceration (VLU) is the most severe presentation of chronic venous insufficiency. About 1% of the population will develop VLU,1 and prevalence rises with age.2 Projected increases in the very old suggest the incidence of VLU will increase. Venous leg ulcerations have considerable impacts on patients; increased pain, impaired sleep, and reduced mobility are common,3,4,5,6,7 while socializing is avoided to reduce the risk of injury,8 and work capacity is impaired.9,10 Patients report feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness.3,7,10,11,12 Participants in VLU trials also report much reduced health-related quality of life at baseline compared with population norms.13 Exercises can improve calf muscle function and ankle joint range of motion in patients with VLU.14,15,16 Guidelines for treating VLU have included recommendations on exercise to improve function,17,18,19 but effects on VLU healing are yet to be determined. The need for further research has been highlighted.20

There have been 2 previous reviews of exercise for VLU, but 1 review included any type of quantitative study to April 2014, did not assess studies for risk of bias, and used a narrative approach to synthesizing results.20 The second review was more recent,21 albeit with the search only up to early 2017, did not limit outcomes to ulcer healing, and included a trial where one-third of participants did not have an ulcer at baseline.22 Therefore, we aimed to summarize the association of exercise interventions with venous leg ulcer healing when used as an adjuvant to any form of compression compared with compression alone.

Methods

Search Strategy

Keyword searches specific to the target databases were developed. Cochrane Controlled Trial Register, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and SCOPUS databases were searched to October 9, 2017. No date or language restrictions were applied to the searches. Reference lists of the included studies were reviewed for additional studies.

Inclusion Criteria

Only parallel-group randomized clinical trials or studies described as randomized clinical trials were included. All participants must have had a current venous leg ulcer at randomization, unless data was reported separately for those with VLU and those with other ulcers. The case definition for VLU need not have been described. Any exercise intervention designed to improve calf muscle function, ankle rotation, or general fitness was eligible, but the exercise must have been used in conjunction with compression therapy (any bandaging system or hosiery) and the trials must have reported a measure of venous ulcer healing. Authors were contacted from potentially relevant articles that did not report a healing outcome to explore whether the healing data could be provided. If articles did report a healing outcome, data on other measures were collected.

Study Selection, Quality Assessment, and Data Extraction

Two of the authors (A.J., J.S.) independently screened titles and abstracts using Covidence (https://www.covidence.org). Where the authors disagreed, consensus discussion was weighted toward retrieval. Full-text papers were obtained from electronic journals and reviewed in Covidence with reasons for exclusion assessed for consensus. The 2 authors (A.J., J.S.) then independently assessed the trials using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias assessments, with disagreements resolved by discussion and appeal to third author (J.P.) if necessary. We did not assess trials on performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel) because it is not possible to blind people to exercise interventions. Data extraction was conducted independently with consensus obtained by discussion. Where necessary, additional information was sought from trial registers, published protocols, or directly from authors.

Exercise or physical activity was categorized on the basis of whether the intervention was limited to a specific type of exercise or combined activity (eg, resistance exercise and physical activity). The exercise regimen was considered to be progressive if it met one of the following approaches to progression: increased load, increased repetitions, increased repetition speed, decreased rest periods between repetitions, or increased volume of total workload.23

Data Synthesis

Where source data was missing for dichotomous healing outcomes in the published articles, we assumed the ulcer state was unhealed at end point and used the number randomized as the denominator to ensure all studies were pooled using intention-to-treat analyses. Data were analyzed using RevMan statistical software (version 5.3, Cochrane) and a fixed effects model in the absence of important statistical heterogeneity. We reported risk difference (RD) as it is likely to be better understood by clinicians and we used GRADE to assess the quality of the evidence for the overall result. Where the numbered analyzed differed from the number randomized, we evaluated the sensitivity of the analysis to inclusion of missing data. This review was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/). The Review Protocol is available in Supplement 1.

Results

Eight hundred fifty-three titles were obtained from searches (Figure 1).24,25,26,27,28,29 Five studies met the inclusion criteria,24,25,26,27,28 and 1 study was potentially relevant but did not publish healing outcomes.30 We contacted the corresponding author who confirmed healing outcomes had been collected, and provided us with a prepublication copy of a second article. We have used that article as the primary reference.29 Therefore 6 studies have been included in this review.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram .

Six randomized clinical trials were selected as meeting the inclusion criteria from the 853 citations identified.

Description of Included Studies

Two trials were conducted in Australia and the United Kingdom and 1 each in Ireland and New Zealand (Table). Two hundred thirty patients participated in the trials, 112 (48.7%) in an exercise arm and 118 (51.3%) in the control arm. Participant ages ranged from a median age of 54 years in 1 trial24 to a mean age of 72 years in 2 trials.25,27 Most participants were women (103, 54%) and ulcer area ranged from a median of 2.4 cm2 to a mean of 7.5 cm2.25,29 Baseline ulcer area was imbalanced in favor of the control group in 3 trials,24,26,27 and the intervention group in 2 trials.25,28 Two trials were not registered25,29 and 2 trials were funded by public good funders,24,28 whereas 4 trials had no external funding.

Table. Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Study | Characteristics (IG vs CG) | Intervention | Frequency, Duration | Outcomes Reported in Trial | Funding, Trial Registration | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jull et al, 200924; New Zealand; home-based; unsupervised; 2-arm parallel group RCT |

No., 40; IG, 21; CG, 19; age, 54.6 years vs 53.3 yearsa; female, 16 vs 11; ABI, 1.1 vs 1.1a; ulcer area, 3.4 vs 3.1 cm2b |

Progressive resistance exercise in addition to compression: 3 sets of heel raises at 80% participant's maximum, represcribed by nurse at 3, 6, and 9 weeks after randomization. Compression type: multilayer bandaging (not specified) or hosiery. |

Alternate days; 12 weeks. |

Complete healing (proportion) at 12 weeks; time to complete healing; change in ulcer area; calf muscle pump function (air plethysmography); adverse events. |

Health Research Council of New Zealand. Austalia New Zealand Clinical Trials Register: ANZCTRN 12606000491561. |

Median ulcer area larger at baseline in exercise group than control group. Meets ACSM criteria for progressive exercise. |

| Meagher et al, 201225; Ireland; home-based; unsupervised; 2-arm parallel group RCT |

No., 35; IG, 18; CG, 17; age, 66.0 years vs 78.0 yearsb; female: 12 vs 13; ABI, 1.17 vs 1.0a; ulcer area (patients with area <10cm2): 17 vs 11 |

Prescribed walking with target of 10 000 steps per day. Compression type: not specified. |

Daily; 12 weeks. |

Complete healing at 12 weeks | None. Not registeredc |

More participants with ulcer area >10 cm2 in control group than exercise group. |

| O'Brien et al, 201326; Australia; home-based; unsupervised; 2-arm parallel group RCT |

No., 13; IG, 6; CG, 7; age, 66.0 years vs 63.6 yearsa; female, 3 vs 2; ABI, 1.05 vs 1.05a; ulcer area, 5.1 vs 3.2 cm2a |

Progressive resistance exercise in addition to compression: 3 sets of 10 then 15, then 20, then 25 repetitions of seated heel raises, progressing to standing heel raises and then 1-legged heel raises (with progression to next level on successful completion of current level for 3 days. Compression type: multilayer (not specified). |

Three times daily; 12 weeks. |

Complete healing at 12 weeks; calf muscle pump function (air plethysmography). |

Queensland University of Technology. Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Register: ACTRN 12611000469910 |

Mean baseline ulcer area greater in exercise than control group. Meets ACSM criteria for progressive exercise. |

| O'Brien et al, 201727; Australia; home-based; unsupervised; 2-arm parallel group RCT |

No., 63; IG, 31; CG, 32; age, 71.3 years vs 71.7 yearsa; female, not reported by group; ABI, not reported; ulcer area: 8.8 vs 6.0 cm2a |

Progressive resistance exercise and walking in addition to compression: 3 sets of 10 then 15, then 20, then 25 reptitions of seated heel raises, progressing to standing heel raises and then 1-legged heel raises (with progression to next level on successful completion of current level for 3 days. Thirty minutes walking 3 times per week. Compression type: not specified (53% in compression >30 mm Hg). |

Three times daily for PRE and 3 times weekly for walking. | Complete healing at 12 weeks; health-related quality of life (SF-8). |

Queensland University of Technology. Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Register: ACTRN 12612000475842 |

Mean baseline ulcer area greater in exercise than control group. Meets ACSM criteria for progressive exercise. |

| Klonizakis et al, 201728; England; gym-based; supervised; 2-arm parallel group RCT |

No., 39; IG, 18; CG, 21: age, 65.4 years vs 61.9 yearsa; female, 9 vs 7; ABI, 1.0 vs 1.1a; ulcer area, 4.9 vs 5.7 cm2b |

Resistance, aerobic and flexibility exercises in addition to compression: Resistance exercises predominantly bodyweight exercises with and without dumbells eg, calf raises and partial squats (2-3 sets of 10-15 repetitions), flexibility focused on ankle joint function and aerobic exercise consisted of 30 minutes treadmill and/or cycling depending on preference. Compression type: not specified. |

Three times per week. | Complete healing at 12 weeks, 6 months and 12 months; time to complete healing; health-related quality of life (EQ5D, VEINES-QOL); costs; adverse events. |

National Institute for Health Research. Current Controlled Trials: ISRCTN10205425 |

Meets ACSM criteria for progressive exercise. |

| Mutlak et al, 201829; home-based; unsupervised; 4-arm parallel group RCT (only pertinent 2 arms included herein) |

No., 40; IG, 20; CG, 20; age, 62.2 years vs 69.2 yearsa; female, 10 vs 10; ABI, not reported; ulcer area: 2.4 vs 2.5 cm2b |

Ten dorsiflexions hourly for every waking hour in addition to compression. Compression type: not specified |

Daily. | Change in ulcer area at 12 weeks. | Hammersmith Hospital. Not registered |

Ulcer area measured as maximum length times maximum width of reference ulcer. |

Abbreviations: ABI, Ankle-Brachial Index; ACSM, Americain College of Sports Medicine, CG, control group; EQ5D, EuorQol 5 D instrument; IG, intervention group; PRE, progressive resistance exercise; QOL, quality of life; RCT, randomized clinical trial; SF-8, Short Form 8 Question Instrument.

Mean.

Median.

Information provided by corresponding author.

The setting for the intervention for 5 trials was unsupervised and home-based whereas 1 trial was gym-based and supervised.28 Four trials met the American College of Sports Medicine definition for progressive resistance exercise, either in isolation,24,26 or in conjunction with prescribed periods of physical activity.27,28 One trial reported multilayer bandaging or hosiery was used,24 another trial reported multilayer bandaging was used,26 and a third reported the proportion of patients who wore compression systems producing greater than 30 mm Hg pressure at the ankle.27 All trials reported outcomes at 12 weeks, and 1 trial followed up with reporting outcomes at 6 and 12 months.28

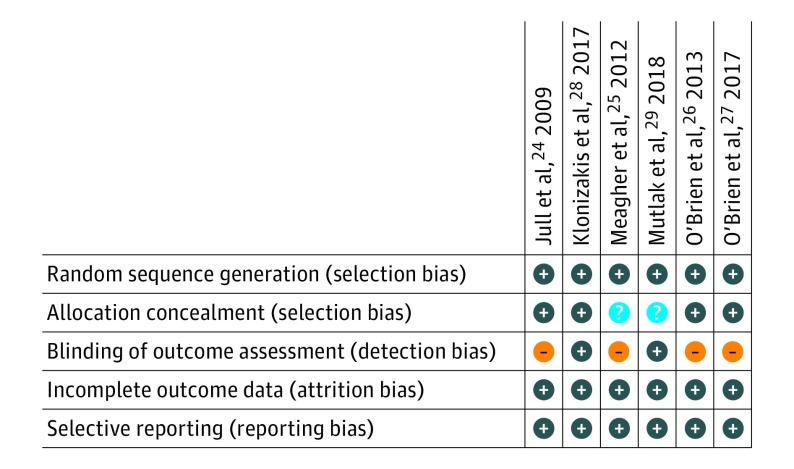

Risk of Bias Assessments

All the studies provided sufficient information to be judged on risk of bias from either the published article, published protocol, trial registry, or contact with the author (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Risk of Bias Summary by Trial and Type of Bias .

All trials were at low risk of bias for sequence generation (selection bias), attrition bias, and reporting bias. Two of 6 trials were at unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment (selection bias) whereas 4 of 6 trials were at high risk of detection bias.

Sequence Generation

All trials were judged to be at low risk of selection bias on sequence generation. Computer-generated random numbers were used in 5 trials and shuffling of sealed envelopes in 1 trial.25

Allocation Concealment

Sealed envelopes were used in 5 trials and central randomization in the sixth trial.28 Two trials did not report the opacity or numbering of the envelopes, but email contact with the authors confirmed the envelopes were sealed and opaque, although not sequentially numbered.25,29 We judged these 2 trials to be at unclear risk of bias, whereas the remaining trials were judged to be at low risk of bias.

Outcome Assessor Blinding

Four trials were judged to be at high risk of detection bias on outcome assessor blinding because they were all open-label trials. A fifth trial used photographs and a blinded assessor for confirmation of healing and was judged to be at low risk of detection bias.28 Email contact with the author of the sixth trial confirmed that the outcome assessor taking measurements for calculating ulcer area was blinded to the treatment and this trial was also judged to be at low risk of bias.29

Incomplete Outcome Data

Three trials either included loss to follow up as treatment failures in intention-to-treat analyses or reported data on all participants.24,25,29 The other 3 trials excluded participants from the analyses, but the missing participants could be included in the denominator as treatment failures as per intention-to-treat analysis.31 Therefore we have judged all the trials to be at low risk of attrition bias.

Selective Outcome Reporting

All trials were judged to be at low risk of reporting bias. Four of the trials were registered and 2 trials also published protocol papers. Authors of the remaining 2 trials provided information via email.

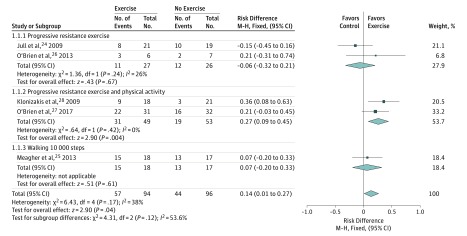

Exercise and Ulcer Healing

Five trials (190 participants) reported proportion of participants healed at 12 weeks and could be combined for an overall estimate of effect (Figure 3).24,25,26,27,28,29 The sixth trial reported median change in ulcer area and could not be included in the meta-analysis.29 The pooled risk difference for any type of exercise from the 5 trials was an added 14 cases healed per 100 patients at 12 weeks (RD, 14%; 95% CI, 1%-27%; P = .04). Statistical heterogeneity was nonsignificant (P = .17) and moderate (I2 = 38%). The finding was robust to sensitivity analysis using the number analyzed in the trials rather than the number randomized (RD, 14%; 95% CI, 0%-27%; P = .04). The GRADE criteria suggested the quality of the evidence be downgraded from high- to low-quality evidence on the basis of 2 factors; imprecision of treatment effect and study limitations (absence of blinding in most trials and unclear allocation concealment in 2 trials).

Figure 3. Forest Plot of the Association of Adjuvant Exercise vs No Exercise With Venous Leg Ulcer Healing.

Overall the effect of adjuvant exercise is to increase healing rates at 12 weeks. Progressive resistance exercise plus physical activity had the strongest association with healing.

Progressive Resistance Exercise

Two trials (53 participants) used unsupervised progressive resistance exercise (heel raises) using the participants' body weight to provide increases in load.24,26 One trial (40 participants) prescribed 3 sets of heel raises on alternate days, with the number of repetitions at 80% of the participant's maximum number of heel raises at each review (baseline and 3, 6, and 9 weeks after randomization).24 The second trial (13 participants) prescribed 3 sets of repetitions (sets of 10, then 15, then 20, then 25 repetitions) of seated heel raises, followed by 2-legged heel raises and then 1-legged heel raises, with progress dependent on successful completion of the previous level for 3 days.26 Neither trial found a significant effect on healing, with more healed ulcers in the control group in 1 trial,24 and more healed ulcers in the intervention group in the other trial.26 The pooled risk difference for progressive resistance exercise was a nonsignificant 6 fewer cases healed per 100 patients at 12 weeks (RD, −6%; 95% CI, −32% to 21%; P = .67). Statistical heterogeneity was nonsignificant (P = .24), but borderline moderate (I2 = 26%). One trial had removed 2 participants in the control group in the analysis.26 The finding was robust to sensitivity analysis using the number analyzed in the trials rather than the number randomized (RD, −9%; 95% CI, −36% to 18%; P = .50).

Progressive Resistance Exercise With Prescribed Physical Activity

Two trials (102 participants) used progressive resistance exercise with prescibed periods of physical activity. One trial (63 participants) used 3 sets of repetitions (sets of 10, then 15, then 20, then 25 repetitions) of seated heel raises, followed by 2-legged heel raises and then 1-legged heel raises, with progress dependent on successful completion of the previous level for 3 days.27 In addition to the progressive resistance exercise participants were prescribed walking 30 minutes per day 3 times per week. The second trial (39 participants) was conducted in exercise facilities and used supervised progressive resistance exercise (calf raises and partial squats with or without weights) and 30 minutes of aerobic exercise (treadmill and/or cycling) 3 times per week, as well as flexibility exercises focused on the ankle joint.28 One trial found a nonsignificant increase in ulcer healing at 12 weeks,27 whereas the second trial found a significant increase in ulcer healing at 12 weeks. The pooled risk difference for progressive resistance exercise was an 27 cases healed per 100 patients at 12 weeks (RD, 27%; 95% CI, 9%-45%; P = .004). Statistical heterogeneity was nonsignificant (P = .42) and unimportant (I2 = 0%). One trial removed 2 participants in each group from their analysis,27 whereas the second trial removed 1 participant from the exercise group in their report.28 The finding was robust to sensitivity analysis using the number analyzed in the trials rather than the number randomized (RD, 29%; 95% CI, 11%-47%; P = .002).

Walking 10 000 Steps

One trial (35 participants) prescribed daily walking with a target of 10 000 steps per day as the intervention in addition to compression.25 The risk difference for prescribed walking was a nonsignificant 7 additional cases healed per 100 patients at 12 weeks (RD, 7%; 95% CI, −20% to 33%; P = .61).

Ankle Exercises

One trial (40 participants) prescribed 10 dorsiflexions per waking hour.29 This trial randomized participants to 1 of 4 arms, but only the compression and exercise arm vs the compression arm is reported here. The trial reported median ulcer area at 12 weeks with a statistically significant median change of 1.67 cm2 in the intervention arm and no change in median ulcer area in the control group.

Adverse Events

Two trials reported adverse events. One trial reported all-cause adverse events with 57 events being reported by 19 participants in the exercise group and 26 events reported by 13 participants in the control group.24 If only the first event of a type was included (excluding multiples of the same event category for an individual patient), 38 events were reported by intervention participants and 26 by usual care participants (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.95-1.85). The second trial reported 2 nonserious adverse events related to exercise (increased ulcer exudate) and no adverse events in the usual care group.28

Health-Related Quality of Life

Two trials reported results on health-related quality of life. One trial used EuroQol-5D and VEINES-QOL at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months,28 but no between-group analysis was conducted. A second trial reported the Physical and Mental Component Summary Scale scores from SF-8 by group at baseline and 12 weeks,27 but found no significant difference between the groups.

Costs

One trial reported costs from health services and patient perspectives.28 The cost per patient to the health services was ₤1423 for the exercise group and ₤2299 for the usual care group, giving a cost saving per patient ₤875 in annual health care costs. The cost to the patient was ₤114 for the exercise group and ₤175 for the usual care group, giving a cost saving per patient ₤61 in annual costs.

Discussion

Our review has added 2 trials to the summarized evidence base.28,29 Prescribing exercise for treating VLU may have an added beneficial effect when used in addition to compression and it appears that the combination of progressive resistance exercises and aerobic activity may be the most effective form of exercise regimen. The evidence base remains limited in terms of the numbers of participants randomized and definitive trials are still required. However, the evidence may now be sufficient to suggest clinicians and suitable patients could consider simple progressive resistance exercises, such as heel raises, and 30 minutes walking at least 3 times per week; adherence to such a regimen suggests that for every 4 patients treated with prescribed exercise plus compression, 1 more patient might heal than if using compression alone. Even if this evidence is found to be incorrect in the future, it is unlikely that such an approach will disadvantage patients, given the benefits of physical activity32 and the impact of prolonged inactivity on function.33,34,35

This review is the first to specifically focus on complete VLU healing and the first review to attempt to summarize the evidence by type of exercise as described by the American College of Sports Medicine.23 Earlier reviews have had a more limited set of trials to summarize, leading 1 review to include observational evidence.20 The second review did have 4 of the trials we included,21 but categorized 1 of the trials as only having a resistance exercise component rather than the exercise and physical activity component.27 Furthermore, that review also included a trial that recruited participants with both open and recently closed ulcers.22 The review authors appear to have used all the participants, including the third that did not have an open ulcer at baseline, when calculating the proportion of patients healed. These errors will have led to inaccuracies in the treatment effects.

Both previous reviews have concluded more evidence is needed, as do we. One possibly important question for future research is to determine the extent to which an exercise regimen should be supervised. Supervised exercise is that which is monitored during the performance of the exercise, but only 1 trial in the current evidence base used such an approach.28 The remaining trials all used home-based approaches, with the progression either supported by reassessment and represcription,24 or systematised with the participants progressing when they determined they met the criterion for progression,26,27 or the trials did not have a progressive element.25,29 Such approaches are more scalable, assuming that clinicians could monitor progress to some degree through normal contacts with the patients. The relative merits of supervised vs home-based exercise regimens are untested, suggesting an opportunity for a noninferiority trial. There also remains sufficient uncertainty about the effect of resistance exercise plus an aerobic activity to merit a definitive trial.

Limitations

This review is subject to several limitations. First, we did not assess for publication bias because the low power of such tests with a small number of trials will not indicate presence or absence of publication bias.36 However, we did not limit our searches, have used databases that included unpublished trials, and searched reference lists of included studies and previous reviews for relevant published or unpublished trials. Second, all the included trials were small with associated risks of imprecision and only 2 studies used outcome assessor blinding; lack of blinding has been shown to overestimate treatment effects.37 However, we have couched our interpretation in cautious terms consistent with low-quality evidence. Third, some studies had missing data that we have imputed as treatment failures. We tested the effect of imputing the data by conducting sensitivity analyses using the data reported by the trials and our findings were robust to these analyses.

Conclusions

The evidence base for incorporating exercise into VLU treatment is growing and may be sufficiently suggestive for clinicians to consider recommending simple progressive resistance and aerobic exercise to suitable patients.

eAppendix. A protocol for a systematic review of exercise as adjuvant treatment for venous leg ulceration

Review Data.

References

- 1.Petherick ES, Pickett KE, Cullum NA. Can different primary care databases produce comparable estimates of burden of disease: results of a study exploring venous leg ulceration. Fam Pract. 2015;32(4):374-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker N, Rodgers A, Birchall N, Norton R, MacMahon S. Leg ulcers in New Zealand: age at onset, recurrence and provision of care in an urban population. N Z Med J. 2002;115(1156):286-289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charles H. The impact of leg ulcers on patients’ quality of life. Prof Nurse. 1995;10(9):571-572, 574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walshe C. Living with a venous leg ulcer: a descriptive study of patients’ experiences. J Adv Nurs. 1995;22(6):1092-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofman D, Ryan TJ, Arnold F, et al. . Pain in venous leg ulcers. J Wound Care. 1997;6(5):222-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krasner D. Painful venous ulcers: themes and stories about living with the pain and suffering. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 1998;25(3):158-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas V. Living with a chronic leg ulcer: an insight into patients’ experiences and feelings. J Wound Care. 2001;10(9):355-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyland ME, Ley A, Thomson B. Quality of life of leg ulcer patients: questionnaire and preliminary findings. J Wound Care. 1994;3(6):294-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callam MJ, Harper DR, Dale JJ, Ruckley CV. Chronic leg ulceration: socio-economic aspects. Scott Med J. 1988;33(6):358-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips T, Stanton B, Provan A, Lew R. A study of the impact of leg ulcers on quality of life: financial, social, and psychologic implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(1):49-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chase SK, Melloni M, Savage A. A forever healing: the lived experience of venous ulcer disease. J Vasc Nurs. 1997;15(2):73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebbeskog B, Ekman S-L. Elderly persons’ experiences of living with venous leg ulcer: living in a dialectal relationship between freedom and imprisonment. Scand J Caring Sci. 2001;15(3):235-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jull A, Muchoney S, Parag V, Wadham A, Bullen C, Waters J. Impact of venous leg ulceration on health-related quality of life: A synthesis of data from randomized controlled trials compared to population norms. Wound Repair Regen. 2018. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang D, Vandongen YK, Stacey MC. Effect of exercise on calf muscle pump function in patients with chronic venous disease. Br J Surg. 1999;86(3):338-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padberg FT Jr, Johnston MV, Sisto SA. Structured exercise improves calf muscle pump function in chronic venous insufficiency: a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(1):79-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies JA, Bull RH, Farrelly IJ, Wakelin MJ. A home-based exercise programme improves ankle range of motion in long-term venous ulcer patients. Phlebology. 2007;22(2):86-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Australian Wound Management Association Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guideline for the Prevention and Management of Venous Leg Ulcers. Canberra: Australian Wound Management Association and NZ Wound Care Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Donnell TF Jr, Passman MA, Marston WA, et al. ; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Venous Forum . Management of venous leg ulcers: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(2)(suppl):3S-59S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franks PJ, Barker J, Collier M, et al. . Management of patients with venous leg ulcer: challenges and current best practice. J Wound Care. 2016;25(6)(suppl 6):S1-S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yim E, Kirsner RS, Gailey RS, Mandel DW, Chen SC, Tomic-Canic M. Effect of physical therapy on wound healing and quality of life in patients with venous leg ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(3):320-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith D, Lane R, McGinnes R, et al. . What is the effect of exercise on wound healing in patients with venous leg ulcers? A systematic review. Int Wound J. 2018;15(3):441-453. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinen M, Borm G, van der Vleuten C, Evers A, Oostendorp R, van Achterberg T. The Lively Legs self-management programme increased physical activity and reduced wound days in leg ulcer patients: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(2):151-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraemer WJ, Adams K, Cafarelli E, et al. ; American College of Sports Medicine . American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(2):364-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jull A, Parag V, Walker N, Maddison R, Kerse N, Johns T. The prepare pilot RCT of home-based progressive resistance exercises for venous leg ulcers. J Wound Care. 2009;18(12):497-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meagher H, Ryan D, Clarke-Moloney M, O’Laighin G, Grace PA. An experimental study of prescribed walking in the management of venous leg ulcers. J Wound Care. 2012;21(9):421-422, 424-426, 428 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Brien J, Edwards H, Stewart I, Gibbs H. A home-based progressive resistance exercise programme for patients with venous leg ulcers: a feasibility study. Int Wound J. 2013;10(4):389-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Brien J, Finlayson K, Kerr G, Edwards H. Evaluating the effectiveness of a self-management exercise intervention on wound healing, functional ability and health-related quality of life outcomes in adults with venous leg ulcers: a randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2017;14(1):130-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klonizakis M, Tew GA, Gumber A, et al. . Supervised exercise training as an adjunct therapy for venous leg ulcers: a randomized controlled feasibility trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1072-1082. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mutlak O, Aslam M, Standfield N. The influence of exercise on ulcer healing in patients with chronic venous insufficiency. Int Angiol. 2018;37(2):160-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mutlak O, Aslam M, Standfield NJ. An investigation of skin perfusion in venous leg ulcer after exercise. Perfusion. 2018;33(1):25-29. doi: 10.1177/0267659117723699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? survey of published randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1999;319(7211):670-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fletcher GF, Ades PA, Kligfield P, et al. ; American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention . Exercise standards for testing and training: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(8):873-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyd CM, Ricks M, Fried LP, et al. . functional decline and recovery of activities of daily living in hospitalized, disabled older women: The Women's Health and Aging Study I. JAGS. 2009;57(10):1757-1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kortebein P, Symons TB, Ferrando A, et al. . Functional impact of 10 days of bed rest in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(10):1076-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornette P, Swine C, Malhomme B, Gillet JB, Meert P, D’Hoore W. Early evaluation of the risk of functional decline following hospitalization of older patients: development of a predictive tool. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(2):203-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hróbjartsson A, Thomsen ASS, Emanuelsson F, et al. . Observer bias in randomised clinical trials with binary outcomes: systematic review of trials with both blinded and non-blinded outcome assessors. BMJ. 2012;344:e1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. A protocol for a systematic review of exercise as adjuvant treatment for venous leg ulceration

Review Data.