Abstract

This study uses 2015-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data to assess prevalence of daily sitting time and weekly leisure-time physical activity among US adults.

High amounts of sedentary behavior and low levels of physical activity are associated with increased risk of premature mortality and some chronic diseases.1 Engaging in high volumes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity may reduce the mortality risk associated with excessive sedentary behavior.1,2 Understanding the combined prevalence of these behaviors could help practitioners determine whether to prioritize interventions targeting sedentary time, physical activity, or both. We examined patterns in joint categories of sitting time and leisure-time physical activity among US adults.

Methods

We used data from the 2015-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a nationally representative survey of the noninstitutionalized, civilian US population.3 NHANES collects health information through in-home interviews and physical examinations. The National Center for Health Statistics research ethics review board approved NHANES. Adult participants (aged ≥18 years) provided written consent. The overall 2015-2016 interview response rate was 61.3%, and there were 5992 adult respondents.

Sedentary behavior was measured as sitting time, defined as daily time spent “sitting at work, at home, getting to and from places, or with friends, including time spent sitting at a desk, traveling in a car or bus, reading, playing cards, watching television, or using a computer” and was assessed with the question “How much time do you usually spend sitting on a typical day?” Reported sitting time was categorized into quartiles of 0 to less than 4 hours, 4 to less than 6 hours, 6 to 8 hours, and more than 8 hours per day.2 Respondents also reported the frequency and duration of moderate- and vigorous-intensity leisure-time physical activity during a typical week. Total leisure-time physical activity was calculated as weekly minutes of moderate-intensity activity plus twice the reported minutes of vigorous-intensity activity and was categorized according to current guidelines as inactive (no moderate- or vigorous-intensity activity), insufficiently active (some activity but not enough to meet sufficiently active definition), sufficiently active (150-300 min/wk), or highly active (>300 min/wk).4

Categorical variables for sitting time and leisure-time physical activity were cross-tabulated to estimate the proportion of adults in each joint category. Estimates were stratified by sex and age category. Analyses were conducted in Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp) using survey commands to account for the sampling design, and full sample interview weights were applied.

Results

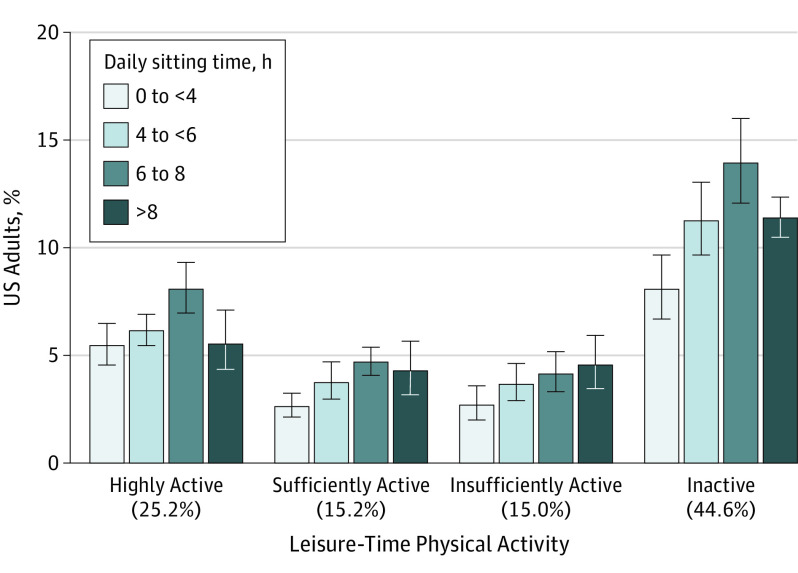

We analyzed data from 5923 adults with complete data (98.8% of total). Overall, 25.7% (95% CI, 23.0%-28.5%) reported sitting for more than 8 hours per day and 44.6% (95% CI, 40.2%-49.0%) were inactive. Across joint categories, the greatest proportion of adults reported sitting for 6 to 8 hours per day and being inactive (13.9%; 95% CI, 12.1%-16.0%), followed by sitting for more than 8 hours per day and being inactive (11.4%; 95% CI, 10.5%-12.4%), and sitting for 4 to less than 6 hours per day and being inactive (11.2%; 95% CI, 9.6%-13.0%) (Figure). The smallest proportions reported sitting for less than 4 hours per day and being sufficiently active (2.6%; 95% CI, 2.1%-3.2%) or sitting for less than 4 hours per day and being insufficiently active (2.7%; 95% CI, 2.0%-3.6%). Patterns were similar by sex (Table). Some differences in the joint distribution of sitting time and leisure-time physical activity were observed between age categories. For example, the joint prevalence of sitting for more than 8 hours per day and being inactive increased with increasing age.

Figure. Joint Distribution of Self-Reported Sitting Time and Leisure-Time Physical Activity Among US Adults, NHANES, 2015-2016.

Data are percentage of US adults who reported each joint category of daily sitting time and leisure-time physical activity. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. NHANES indicates National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Table. Joint Distribution of Self-Reported Sitting Time and Leisure-Time Physical Activity by Sex and Age Category, NHANES, 2015-2016.

| Leisure-Time Physical Activitya | Daily Sitting Time, No. (%) [95% CI]b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to <4 h | 4 to <6 h | 6 to 8 h | >8 h | |

| Sex | ||||

| Men (n = 2858) | ||||

| Inactive | 309 (7.9) [6.5-9.7] | 369 (11.2) [9.3-13.4] | 414 (13.1) [11.3-15.1] | 293 (10.5) [9.1-12.1] |

| Insufficiently active | 74 (2.5) [1.9-3.4] | 87 (3.3) [2.5-4.2] | 99 (3.6) [2.7-4.8] | 89 (4.4) [2.8-6.6] |

| Sufficiently active | 64 (2.3) [1.6-3.2] | 86 (3.2) [2.2-4.5] | 95 (4.4) [3.5-5.6] | 89 (4.6) [2.9-7.0] |

| Highly active | 182 (6.0) [4.6-7.7] | 208 (7.4) [6.3-8.8] | 252 (9.8) [8.3-11.5] | 148 (6.0) [4.4-8.1] |

| Women (n = 3065) | ||||

| Inactive | 373 (8.2) [6.4-10.5] | 409 (11.3) [9.6-13.2] | 501 (14.7) [12.3-17.5] | 350 (12.2) [11.0-13.6] |

| Insufficiently active | 90 (2.8) [2.0-4.0] | 110 (4.0) [2.9-5.6] | 142 (4.7) [3.5-6.3] | 114 (4.7) [3.3-6.5] |

| Sufficiently active | 101 (2.9) [2.3-3.8] | 110 (4.3) [3.2-5.7] | 120 (4.9) [4.0-6.0] | 90 (3.9) [2.8-5.5] |

| Highly active | 141 (5.0) [4.1-6.0] | 137 (4.9) [4.1-5.9] | 161 (6.5) [5.0-8.4] | 116 (5.1) [3.7-7.1] |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18-39 (n = 2208) | ||||

| Inactive | 200 (7.6) [6.1-9.0] | 234 (9.5) [7.3-11.7] | 250 (10.5) [8.7-12.2] | 182 (8.1) [6.8-9.3] |

| Insufficiently active | 48 (2.1) [1.2-2.9] | 66 (3.2) [2.1-4.3] | 83 (3.5) [2.6-4.4] | 78 (4.1) [3.0-5.3] |

| Sufficiently active | 66 (3.1) [2.2-4.0] | 86 (3.9) [2.8-5.1] | 89 (4.7) [3.3-6.1] | 86 (5.0) [3.2-6.7] |

| Highly active | 177 (7.6) [6.0-9.2] | 181 (8.6) [7.7-9.5] | 231 (10.7) [8.9-12.5] | 151 (8.0) [6.2-9.7] |

| 40-64 (n = 2362) | ||||

| Inactive | 329 (9.0) [6.8-11.2] | 320 (11.6) [9.0-14.1] | 366 (14.4) [11.4-17.4] | 267 (12.6) [11.0-14.3] |

| Insufficiently active | 85 (3.6) [2.0-5.1] | 79 (3.1) [1.9-4.2] | 100 (3.8) [2.6-5.1] | 94 (5.7) [3.6-7.9] |

| Sufficiently active | 67 (2.3) [1.4-3.2] | 70 (3.7) [2.3-5.2] | 84 (4.7) [3.9-5.5] | 70 (4.1) [2.4-5.7] |

| Highly active | 103 (4.6) [3.3-5.8] | 105 (4.7) [3.3-6.0] | 128 (7.2) [5.6-8.8] | 95 (5.0) [3.2-6.8] |

| ≥65 (n = 1353) | ||||

| Inactive | 153 (7.0) [5.3-8.7] | 224 (13.7) [11.0-16.5] | 299 (19.5) [16.0-22.9] | 194 (15.1) [12.7-17.6] |

| Insufficiently active | 31 (1.9) [0.5-3.4]c | 52 (5.9) [2.9-9.0] | 58 (6.0) [3.5-8.6] | 31 (2.6) [0.8-4.3]c |

| Sufficiently active | 32 (2.2) [0.7-3.7]c | 40 (3.4) [1.6-5.1] | 42 (4.5) [2.3-6.8] | 23 (3.2) [1.6-4.8] |

| Highly active | 43 (3.3) [2.1-4.5] | 59 (4.6) [2.6-6.7] | 54 (4.8) [3.3-6.4] | 18 (2.1) [1.1-3.2] |

Abbreviation: NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Leisure-time physical activity was assessed with the following questions: (1) “In a typical week, do you do any vigorous-intensity sports, fitness, or recreational activities that cause larger increases in breathing or heart rate like running or basketball for at least 10 minutes continuously [excluding work and transportation activities that have already been mentioned]?” (2) “In a typical week, on how many days do you do vigorous-intensity sports, fitness, or recreational activities?” (3) “How much time do you spend doing vigorous-intensity sports, fitness, or recreational activities on a typical day?” (4) “In a typical week, do you do any moderate-intensity sports, fitness, or recreational activities that cause a small increase in breathing or heart rate such as brisk walking, bicycling, swimming, or golf for at least 10 minutes continuously?” (5) “In a typical week, on how many days do you do moderate-intensity sports, fitness, or recreational activities?” (6) “How much time do you spend doing moderate-intensity sports, fitness, or recreational activities on a typical day?” Total leisure-time physical activity was calculated as weekly minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity plus twice the reported minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity and was categorized according to current guidelines as highly active (>300 min/wk), sufficiently active (150-300 min/wk), insufficiently active (some activity but not enough to meet sufficiently active definition), or inactive (no moderate- or vigorous-intensity activity of ≥10 minutes).

Data are the unweighted number of respondents and percentage estimates weighted using full sample interview weights provided with NHANES data. Daily sitting time was assessed with the following question: “The following question is about sitting at work, at home, getting to and from places, or with friends, including time spent sitting at a desk, traveling in a car or bus, reading, playing cards, watching television, or using a computer. Do not include time spent sleeping. How much time do you usually spend sitting on a typical day?” Reported sitting time was categorized in approximate quartiles of 0 to less than 4, 4 to less than 6, 6 to 8, and more than 8 hours per day.

The relative standard error for this estimated prevalence is greater than 30%, indicating that the estimate is potentially unreliable and should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

These data reveal a substantial prevalence of high sitting time and physical inactivity among US adults: about 1 in 4 sit for more than 8 hours a day, 4 in 10 are physically inactive, and 1 in 10 report both. The limitations of this study include possible bias inherent in self-reported data and that physical activity episodes shorter than 10 minutes may not have been captured.

Both high sedentary behavior and physical inactivity have negative health effects, and evidence suggests that the risk of premature mortality is particularly elevated when they occur together.1,2 Evidence-based strategies to reduce sitting time, increase physical activity, or both would potentially benefit most US adults, particularly older adults. Practitioners can support efforts to implement programs, practices, and policies where adults live, learn, work, and play to help them sit less and spend more time being physically active.1,5,6

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee . 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekelund U, Steene-Johannessen J, Brown WJ, et al. ; Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee; Lancet Sedentary Behaviour Working Group . Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? a harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1302-1310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30370-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics . National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, 2015-2016. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx?BeginYear=2015. Accessed August 1, 2018. [PubMed]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services . Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, Second Edition. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services . Step It Up! The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Walking and Walkable Communities. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services Office of the Surgeon General; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Community Preventive Services Task Force . Built Environment Approaches Combining Transportation System Interventions With Land Use and Environmental Design: Task Force Finding and Rationale Statement. December 2016. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/PA-Built-Environments.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2018.