Abstract

Background: Childhood obesity prevention interventions have engaged coalitions in study design, implementation, and/or evaluation to improve research outcomes; yet, no systematic reviews have been conducted on this topic. This mixed methods review aims to characterize the processes and dynamics of coalition engagement in community-based childhood obesity prevention interventions.

Methods: Data Sources: Studies extracted from Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science; complementary original survey and interview data among researchers of included studies. Eligible Studies: Multisetting community-based obesity prevention interventions in high-income countries targeting children 0–12 years with anthropometric, behavioral, or environmental/policy outcomes. The Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Conceptual Model was used as an overarching framework.

Results: Thirteen studies met inclusion criteria. Elements of CBPR were evident across all studies with community engagement in problem identification (n = 7), design/planning (n = 11), implementation (n = 12), evaluation (n = 4), dissemination (n = 2), and sustainability (n = 10) phases. Five studies reported favorable intervention effects on anthropometric (n = 4), behavioral (n = 1), and/or policy (n = 1) outcomes; descriptive associations suggested that these studies tended to engage community members in a greater number of research phases. Researchers involved in 7 of 13 included studies completed a survey and interview. Respondents recalled the importance of group facilitation, leadership, and shared understanding to multisector coalition work. Perceived coalition impacts included community capacity building and intervention sustainability.

Conclusions: This review contributes to a deeper understanding of intervention processes and dynamics within communities engaged in childhood obesity prevention. Future research should more rigorously assess and report on coalition involvement to assess the influence of coalitions on multiple outcomes, including child weight status.

Keywords: : childhood obesity prevention, community-based interventions, community coalitions, partnership dynamics, systematic review

Community-based interventions are an important strategy for preventing childhood obesity.1–7 Interest to intervene in this setting is driven in part by the desire to have a large-scale impact on multiple sectors8,9 and the perceived importance of tailoring intervention design to context.10 Community coalitions—defined as groups of leaders and stakeholders from diverse organizations, settings, and sectors working collectively on a common objective (sometimes referred to as steering committees, task forces, advisory boards, etc.)11,12—can help achieve large-scale interventions within the local context.

Coalitions may serve as a body to activate and empower community stakeholders and bolster cross-sector collaboration to design, implement, evaluate, and sustain interventions that leverage community assets, leadership, expertise, cultural norms, and systems infrastructure.11–17 These features could be considered mechanisms to achieve desired community-level health outcomes and/or outcomes in themselves.18

However, despite national and international organizations' recommendations to involve community coalitions in obesity prevention efforts,4,5 little empirical evidence has documented contributions of coalitions to intervention processes and childhood obesity outcomes. This review aims to (1) characterize the processes and dynamics of coalition engagement in community-based childhood obesity prevention interventions, and (2) identify gaps in the literature and recommendations for future investigation and reporting of community-engaged approaches to childhood obesity prevention.

Methods

This research was guided by PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses)19,20 and the Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Conceptual Model: a framework to understand factors related to community coalition work, such as local context and structural (e.g., diversity and formal agreements), relational (e.g., trust and flexibility), and individual (e.g., values and motivation) partnership dynamics that may influence multiple outcomes.21–23 The review was registered with the PROSPERO register of systematic reviews (#42017067822; www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO).

Information Sources and Search Strategies

The research team compiled search terms based on literature and content expertise (Table 1). Detailed search terms are available in Supplementary Appendix A (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/chi). Initial database searches included Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science, completed on October 2, 2015. Searches were updated on January 5, 2017 [timeline extension to accommodate substudy (see Substudy: Survey and Interview Data Collection section below)]. Citations from three relevant systematic reviews were also searched.3,13,24

Table 1.

Summary of Database Search Strategy

| Topics | Example keywords |

|---|---|

| Obesity | Adiposity, body mass index, overweight, obesity |

| Community based | Community, stakeholder, collaboration, CBPR, coalition, task force |

| Prevention | Prevent |

| Participant age | Child, pediatric, infant, toddler, preschool |

| Study design | NOT: cross-sectional or qualitative |

Detailed search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science available in Supplementary Appendix A.

CBPR, Community-Based Participatory Research.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies were published in English since 1990, described multisetting community-based interventions conducted in high-income countries,25 targeted children aged 0–12 years, reported anthropometric, behavioral, or environmental/policy outcomes, and engaged a community coalition in the research process. Studies with older children were included if ages 0–12 years were also represented. Articles with the following characteristics were excluded: reviews, reports, book chapters, observational and qualitative studies, pilot and program evaluation studies not powered to detect change, and focus on treating children with overweight or obesity.

Study Selection

A.R.K. and a trained research assistant screened the study titles. Next, two researchers independently screened each article abstract. E.H. or A.T. was consulted to resolve discrepancies. Finally, A.R.K. and a research assistant read the full text of included articles. To help confirm the presence or absence of coalition involvement, complementary peer-reviewed articles (protocols and process evaluation papers) and/or official reports of studies (e.g., for studies funded by government), if available, were reviewed.

Data Extraction

For each included study, two researchers independently extracted data, including location, study name and years, research/evaluation design, sample (size, age), intervention features (scope, duration), study phases with participatory community engagement (problem identification, design and planning, implementation, evaluation, dissemination, sustainability),26 coalition description, and primary outcome. Discrepancies were reviewed as a team. If study authors did not state the primary outcome in any associated article, the funding source and/or clinicaltrials.gov were used to source this information. Frequencies and means [± standard deviation (SD)] were calculated in Excel to explore associations between the number and type of participatory study phases by intervention results (positive, mixed, null, and negative). Studies with dual primary outcomes (e.g., BMI and physical activity) were categorized as having “positive,” “null,” or “negative” results if both outcomes fell in the same category; otherwise, studies were categorized as having “mixed” results.

Substudy: Survey and Interview Data Collection

All included studies lacked some level of detail on the coalition's involvement. To address this gap, the principal investigators or senior researchers (“researchers”) of those studies were recruited to complete a survey and interview. Multisite or multicountry studies were excluded from the substudy because of anticipated difficulty of asking one respondent to recall coalition-related information across multiple geographies. In one case, a study participant was also the systematic review principal investigator (C.D.E.; participation approved by the Tufts University Institutional Review Board).

Online survey

Informed by the CBPR Conceptual Model21–23 and gaps in the published literature, the research team created a 28-item web-based survey (Qualtrics) to assess history and context (n = 2 items), partnership dynamics (n = 13), intervention and research processes (n = 11), and impact and sustainability outcomes (n = 2) of community coalitions (Supplementary Appendix B). Items were generated by the research team. Surveys were programmed individually to include the relevant study name and coalition name. Question types varied, including categorical select one or select all that apply items with options, where applicable, to include “Other” open-ended responses or indicate “I'm not sure” to minimize guessing; a 4-point scale to rate coalition activities as a major function, minor function, intended as a function but not carried out, and not intended as a function; and a 10-point scale to estimate levels of knowledge and engagement of coalitions, respectively, about childhood obesity prevention efforts at the intervention beginning and end.

Phone interview

Four semistructured interview questions were developed by the research team to elicit additional information about the domains described above, with probes addressing coalition leadership, group dynamics, facilitators and barriers to coalition involvement, and perceived impact on intervention outcomes. Interview guides were populated with participants' survey responses to facilitate discussion (Supplementary Appendix C).

Procedures

Researchers' contact information (email and/or telephone) was acquired through existing professional relationships and the Internet. Email or telephone recruitment occurred between April and May 2017. Participants completed the Qualtrics survey between April and June 2017 and a follow-up phone interview conducted by E.H. or A.T. (April–July 2017). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim; transcripts were complemented by interviewer notes. Human subject procedures were approved by the Tufts University Institutional Review Board. Elements of informed consent were provided upon recruitment and survey and interview initiation.

Data analysis

Survey and interview data were analyzed in aggregate. Findings were interpreted based on four CBPR Conceptual Model domains: history and context, coalition partnership dynamics, intervention and research process, impact and sustainability outcomes.21–23 Survey data were analyzed using Qualtrics and Excel to calculate frequencies and means (±SD). Open-ended responses were recoded and categorized when possible. Interview data were analyzed with inductive and deductive thematic analysis and guided by the CBPR Conceptual Model.21–23 A.R.K., A.T., and C.F. generated an initial structural codebook using two transcripts over two rounds of iterative coding. A.R.K. independently coded all interview transcripts and made codebook modifications. A.T. reviewed this work and discussed further modifications with A.R.K., adapting ∼20% of the codebook structure. All researchers contributed to thematic analysis and selection of representative quotes. Themes were organized into a visual guiding framework to facilitate analysis and interpretation.

Results Synthesis

All available data were analyzed for common themes using qualitative synthesis.

Results

Study Selection

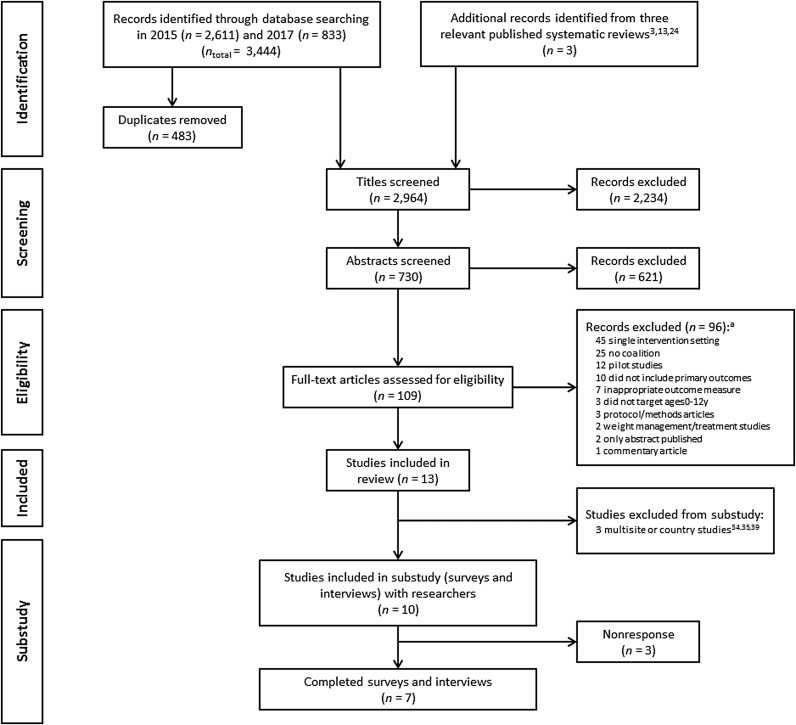

The study selection process is given in Figure 1 with 2964 records identified and 109 full-text articles screened for eligibility. Thirteen studies met all the inclusion criteria and were included in the review.27–39

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of study selection and overview of substudy with surveys and interviews. aSum of excluded articles exceeds 96 because of some records meeting multiple exclusion criteria. PRISMA, preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Study Characteristics: Published Literature

Table 2 includes study descriptions extracted from the published literature. Studies were conducted between 1999 and 2016 in the United States (n = 8),27–34 Europe (n = 2),35,39 and Australia (n = 3).36–38 Intervention durations ranged from 6 months to 5 years. There was one randomized controlled trial,30 nine nonrandomized controlled trials,27,29,31–33,36–39 two pre-post nonexperimental designs,28,35 and one nonexperimental design with postdata collection only.34

Table 2.

Study Characteristics of 13 Studies Included in the Systematic Review, Organized by Primary Outcome, Results, and Alphabetized by Study Name; Data from Published Peer-Reviewed Literature and Reports

| Citations | Location | Study name (years) | Research/evaluation design | Sample size (intervention, control) | Target age (baseline mean ± SD) | Intervention length | Intervention description | Study phases with participatory community engagement26 | Coalition description | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome: anthropometrics | ||||||||||

| Positive results | ||||||||||

| Bell et al.51 and Sanigorski et al.38 | Barwon South West region, Victoria, Australia | Be Active Eat Well (2002–2006) | Nonrandomized controlled design | 1001, 1183 (consented to participate) | 4–12 years Intervention: 8.2 ± 2.3 years Control: 8.3 ± 2.2 years |

3 years | Capacity building intervention to promote healthy eating, physical activity, and decreased screen time in schools (e.g., nutrition policies, walking school buses) and in the community (e.g., social marketing, community events, restaurants) | □ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation ☑ Evaluation □ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

Stakeholders supported capacity building process and served on various groups (Steering, Local Implementation, Management, and Reference Committees).51 Representation included healthcare, local government, and a local neighborhood renewal organization38 | Relative to controls, BMI z-score significantly decreased by 0.11 units in the intervention group from baseline to follow-up38 |

| Chomitz et al.28 | Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States | Healthy Living Cambridge Kids (2003–2007) | Pre-post design with longitudinal cohort |

Eligible: 3561, N/A (school data, no consent) Analytic sample: 1858, N/A |

K-5th grade (∼5–11 years) 7.7 ± 1.8 years |

3 years | CBPR “grassroots” environmental and policy intervention to promote child healthy weight and fitness in schools (e.g., expanded physical education, gardens), at home (e.g., annual BMI and fitness reports), and in the community (e.g., city-wide policies, family nights) | ☑ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation ☑ Evaluation ☑ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

Healthy Children Task Force representation included researchers, schools, healthcare, public health, local government, community organizations, and parents. The task force convened in 1990 to promote children's health and began prioritizing healthy eating, healthy weights, physical activity, and fitness in 2000. Members were involved in formative work (e.g., fundraising, piloting interventions) and stayed engaged in all other phases of the research. | BMI z-score significantly decreased by 0.04 units from baseline to follow-up |

| Martinie et al.59 and Benjamin Neelon et al.27 | Mebane, North Carolina, United States | Mebane on the Move (2011–2012) | Pre-post natural experiment with comparison community | 64, 40 (consented to participate) | 5–11 years Intervention: 7.8 ± 1.8 years Control: 8.3 ± 1.9 years |

6 months | Environmental change intervention to promote physical activity before and after school (e.g., walking and running clubs), at home (e.g., portable play equipment), and in the community (e.g., installation of sidewalks, crosswalks, and walking trails) | ☑ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

The community-driven intervention was funded, planned, and implemented by a group of community members with representation from local business, schools, government, and health sectors. The group approached university researchers to be an evaluation partner27,59 | Relative to controls, BMI z-score significantly decreased by 0.5 units in the intervention group from baseline to follow-up.27 |

| Economos et al.29,52 | Greater Boston area, Massachusetts, United States | Shape Up Somerville: Eat Smart, Play Hard™ (2002–2005) | Nonrandomized controlled design | 631, 1065 (consented to participate) | 1st–3rd grade (∼6–9 years) Total sample: 7.6 ± 1.0 years |

2 school years | CBPR environmental change intervention to promote healthy eating and physical activity access and availability before, during, and after school, at home, and in the community (e.g., restaurants, media) | ☑ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation ☑ Evaluation ☑ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

Community Advisory Council membership was informed by existing relationships and by engaging community members in formative work (focus groups and key informant interviews). Multiple sectors were involved in intervention implementation (e.g., parents, teachers, foodservice, local government, healthcare)29 | Relative to controls, BMI z-score significantly decreased by 0.10 units in the intervention community from baseline to year 1 follow-up29 and by 0.06 units from baseline to year 2 follow-up52 |

| Mixed results | ||||||||||

| de Groot et al.53 and de Silva-Sanigorski et al.36 | Geelong, Victoria, Australia | Romp & Chomp (2004–2008) | Nonrandomized controlled design with pre-post cross-sectional evaluation |

2 year-old-sample: Pre: 1587, 17,732 Post: 1611, 21,911 3.5 year-old-sample: Pre: 1191, 14,647 Post: 1239, 19,050 (data from state health service) |

0–5 years Evaluation: 2 and 3.5 years |

4 years | Capacity building53 and environmental (policy, sociocultural, physical) change intervention to promote healthy eating and active play in early education and care settings | ☑ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

Community stakeholders were consulted on intervention development and a management committee supervised implementation. The committee represented academia, healthcare, local government, early education, recreation, local health department, and oral health.36 |

2 year-old-sample: Relative to controls, no significant intervention effect on BMI z-score. 3.5 year-old-sample: Relative to controls, BMI z-score significantly decreased by 0.04 units in the intervention group from baseline to follow-up.36 |

| Null results | ||||||||||

| Pettman et al.37,54 | Greater Adelaide area, South Australia, Australia | Eat Well Be Active Community Programs (2006–2009) | Nonrandomized controlled design with pre-post cross-sectional evaluation |

4–5 year-old-sample: Pre: 464, 541 Post: 455, 789 (data from state health service) 10–12 year-old-sample: Pre: 836, 790 Post: 590, 608 (consented, with measures) |

0–18 years Evaluation: 4–5 and 10–12 years |

3 years | Community development and capacity building intervention to promote healthy eating and physical activity via 6 strategies (professional development, policy, infrastructure, programs and resources, promotion, and community development) across multiple settings (e.g., child care, health, recreation) | ☑ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation ☑ Evaluation □ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

3 age-specific Local Action Groups in each intervention community (under 5 s, primary school, youth) gave input on local contexts and ideas for intervention components54 | Relative to controls, no significant intervention effect on BMI z-score in either age group37 |

| Gantner and Olson55 and Olson et al.32 | Upstate New York State, United States | Healthy Start Partnership (2005–2009) | Nonrandomized controlled design with two nonconcurrent cohorts (controls recruited first and not exposed to intervention) |

Recruited during pregnancy: 276, 219 Infant analytic sample: 257, 207 |

0–7 months (mean not reported) | 4 years | Community-based environmental change interventions to promote healthy pregnancy weight gain, postpartum weight loss, and infant growth. Interventions were delivered within and across counties and largely focused on the social environment (e.g., social marketing campaign). Targeted behaviors included healthy eating, breastfeeding, and physical activity | □ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

The Healthy Start Partnership was convened by university researchers in 2005. Representation included nutrition, public health, maternal and child health, hospitals, and community-based organizations with 58 total partners (majority mid-level professionals). Partners met by county and regionally to exchange information and build capacity to develop and implement obesity prevention interventions. | Relative to controls, no significant intervention effect on infant rapid weight gain (defined by weight-for-length z-score trajectories)32 |

| de la Torre et al.56 and Sadeghi et al.33 | Central Valley, California, United States | Niños Sanos, Familia Sana (2011–2016) | Quasi-experimental controlled design (communities randomly selected after key stakeholders agreed to participate) | 378, 217 (consented, with baseline measures) | 3–8 years Intervention: 6.1 ± 1.3 years Control: 6.1 ± 1.2 years |

3 years | CBPR behavioral intervention among Mexican-origin children and their families to promote healthy eating and physical activity in schools and in the community (e.g., Family Nights, community events). Families received monthly vouchers to purchase fruits and vegetables | □ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination □ Sustainability |

University researchers convened Community Advisory Councils in both intervention and control communities to monitor progress and give input on implementation factors.33 The councils met quarterly and included representation from local government, schools, faith-based organizations, and healthcare (including community health workers, or promotores, to aid with recruitment and implementation)56 | Year 1 results: Relative to controls, no significant intervention effect on BMI z-score33 (results from years 2–3 were not published at the time of this review) |

| Gomez et al.57,a and Gomez Santos et al.35 | 10 municipalities, Spain | Programa Thao-Salud Infantil (2007–2011) | Pre-post design with longitudinal cohort | Analytic sample: 6697, N/A (eligible sample size not reported) | 3–12 years (mean not reported) | 4 years | EPODE49 community-based intervention to promote healthy lifestyles among children and families (i.e., healthy eating, physical activity, adequate sleep, and quality of life). The intervention includes multiple health promotion activities in multiple municipal settings (e.g., schools, food markets, healthcare) | □ Problem identification □ Design and planning ☑ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

In each municipality, program implementation was led by a multidisciplinary team (Thao local team) with stakeholder representation from local government, healthcare, schools, sports, libraries, social services, media, and food markets. Local project managers were selected by local government leaders57 | From baseline to follow-up, prevalence of overweight and obesity increased from 27.3% to 28.3%.35 (statistical significance not reported) |

| Eisenmann et al.60 and Gentile et al.30 | Lakeville, Minnesota and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, United States | Switch® what you Do, View, and Chew (2005–2006) | Randomized controlled design with pre, post, and 6-month follow-up | 670, 653 (consented to participate) | 3rd–5th grade (∼8–11 years) Total sample: 9.6 ± 0.9 years |

8 months | Behavioral and environmental change intervention to decrease screen time (primary behavioral outcome) and promote physical activity and fruit and vegetable intakes in schools, among families, and in the community (e.g., messaging campaign to build public awareness) | □ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

In 2004, a coalition was convened “to give the project high visibility, and to advocate for and sustain the project (page 6).” Representation included community leaders from school, healthcare, government, business, and religious sectors60 | Relative to controls, no significant intervention effect on BMI z-score30 |

| Negative results | ||||||||||

| De Henauw et al.39 and Pigeot et al.58 | Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Spain, and Sweden | IDEFICS (2007–2010) | Nonrandomized, controlled design in each country | 8482, 7746 (consented, with no missing data) | 2–9.9 years Intervention: 6.1 ± 1.8 years Control: 6.0 ± 1.8 years |

2 years | Promoted healthy diet, reduced screen time, increased physical activity, more family time, and sleep duration in schools (e.g., installation of water fountains), at home (e.g., messaging and education), and in the community (e.g., infrastructure changes to promote safe outdoor play). Interventions developed centrally and then adapted and translated for each community58 | □ Problem identification □ Design and planning ☑ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination □ Sustainability |

In each community, local program managers worked with local intervention program committees to implement the intervention. Implementation was supported by community platforms (representation from local government, public health, and other health stakeholders) and school platforms (representation from teachers and parents).58 | Prevalence of overweight and obesity increased in intervention (19.0–23.6%) and control (18.0–22.9%) groups from baseline to follow-up. No significant difference between groups39 |

| Gombosi et al.31 | North-central Pennsylvania, United States | Tioga County Fit for Life Project (1999–2004) | Nonrandomized controlled design | Eligible: 4804, not reported (school data, no consent) | K-8th grade (5–14 years) (mean not reported) | 5 years | Multicomponent intervention to promote nutrition and physical activity in schools, among families (e.g., occupational health fairs), in the broader community (e.g., Family Fun Days), and healthy eating in restaurants | ☑ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning □ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination □ Sustainability |

The Fit for Life task force formed in 1997 and served as an advisory board for the intervention. Representation included healthcare, public schools, and private schools. The task force developed goals and helped plan the school-based intervention curriculum | Prevalence of overweight and obesity increased across all grades (intervention effect relative to control group not reported). |

| Primary outcome: behavior | ||||||||||

| Positive results | ||||||||||

| Martinie et al.59 and Benjamin Neelon et al.27 | Mebane, North Carolina, United States | Mebane on the Move (2011–2012) | Pre-post natural experiment with comparison community | 64, 40 (consented to participate) | 5–11 years Intervention: 7.8 ± 1.8 years Control: 8.3 ± 1.9 years |

6 months | Environmental change intervention to promote physical activity before and after school (e.g., walking and running clubs), at home (e.g., portable play equipment), and in the community (e.g., installation of sidewalks, crosswalks, and walking trails) | ☑ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

The community-driven intervention was funded, planned, and implemented by a group of community members with representation from local business, schools, government, and health sectors. The group approached university researchers to be an evaluation partner27,59 | Relative to controls, intervention children significantly increased moderate-to-vigorous and vigorous physical activity by 1.3 and 0.8 minutes/hour, respectively, from baseline to follow-up (assessed by accelerometry)27 |

| Mixed results | ||||||||||

| Eisenmann et al.60 and Gentile et al.30 | Lakeville, Minnesota and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, United States | Switch what you Do, View, and Chew (2005–2006) | Randomized controlled design with pre, post, and 6-month follow-up | 670, 653 (consented to participate) | 3rd–5th grade (∼8–11 years) Total sample: 9.6 ± 0.9 years |

8 months | Behavioral and environmental change intervention to decrease screen time (primary behavioral outcome) and promote physical activity and fruit and vegetable intakes in schools, among families, and in the community (e.g., messaging campaign to build public awareness) | □ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

In 2004, a coalition was convened “to give the project high visibility, and to advocate for and sustain the project (page 6).” Representation included community leaders from school, healthcare, government, business, and religious sectors60 | Relative to controls, intervention children had significantly lower parent-reported screen time postintervention (Cohen's d = 1.26) and at 6-months follow-up (d = 1.38) (effect size ∼2 hours/week). Child-reported screen time findings were not statistically significant30 |

| Primary outcome: environment and policy | ||||||||||

| Positive results | ||||||||||

| Subica et al.34,61 | Communities in 16 states, United States | Communities Creating Healthy Environments Initiative (2009–2014) | Postintervention evaluation | 21 organizations and tribal nations representing communities of color (grantees), N/A | All children (age not specified) | 3 years | Community organizing health promotion interventions to advocate for environment and policy change related to children's healthy food and safe recreation access among African American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian American, and American Indian/Alaskan Native communities | ☑ Problem identification ☑ Design and planning ☑ Implementation □ Evaluation □ Dissemination ☑ Sustainability |

Grantees raised issue awareness and advocated for change by mobilizing coalitions, creating new stakeholder alliances and partnerships, and building local capacity and leadership through youth and resident engagement | 72 policy winsb (per grantee, mean 3.43 ± 1.78; range 1–8) related to healthy food access, recreation, healthcare, clean environments, affordable housing, and safe neighborhoods34 |

The article narrative includes citations for studies' primary outcomes paper, whereas this table includes additional citations if applicable (e.g., process evaluation article that includes information about the coalition's involvement). Mebane on the Move and Switch what you Do, View, and Chew had primary anthropometric and behavioral outcomes and therefore these studies are presented twice in the table; study characteristics (e.g., location, intervention description, and coalition description) are included in both anthropometric and behavior sections for ease of interpretation.

Protocol for a separate 2-year school-based evaluation of Programa Thao-Salud Infantil that includes information about the coalition.

Policy wins definition: “concrete, quantifiable movements toward improving local environments and policies to support children's healthy eating and active living that were directly traceable to grantees' CCHE interventions and obtained during or within 6 months postintervention.” (page 918).34

EPODE, Ensémble Prevenons l'Obesité des Enfants (Together Let's Prevent Childhood Obesity); IDEFICS, Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFects In Children and infantS; Niños Sanos, Familia Sana: Healthy Children, Healthy Family; Programa Thao-Salud Infantil: Thao-Child Health Programme; N/A, not applicable.

Most studies included anthropometric primary outcomes (n = 12), including BMI z-score,27–30,33,36–38 overweight and obesity prevalence,31,35,39 and infant rapid weight gain.32 Two studies had anthropometric and behavioral primary outcomes, each with assessments of BMI z-score in addition to physical activity27 and screen time,30 respectively. One study assessed policy outcomes.34

Three studies reported using a CBPR approach28,29,33 and two studies reported participatory community engagement in all study phases.28,29 Table 3 shows the frequency of community-engaged study phases presented alongside study results (positive, mixed, null, and negative). Across the 13 included studies, community members engaged in an average 3.5 ± 1.6 phases, including problem identification (n = 7),27–29,31,34,36,37 design and planning (n = 11),27–34,36–38 implementation (n = 12),27–30,32–39 evaluation (n = 4),28,29,37,38 dissemination (n = 2),28,29 and sustainability (n = 10).27–30,32,34–38 Descriptive associations suggested that the five studies with positive findings on BMI z-score,28,29,38 BMI z-score and physical activity,27 and policy change34 tended to engage community members in more phases (4.8 ± 1.1),27–29,34,38 than studies with mixed (n = 2; 3.5 ± 0.7),30,36 null (n = 4; 3.0 ± 1.4),32,33,35,37 and negative results (n = 2; 1.5 ± 0.7).31,39

Table 3.

Community-Engaged Research Phases Presented Alongside Study Results

| Positive results (n = 5) | Mixed results (n = 2) | Null results (n = 4) | Negative results (n = 2) | All studies (n = 13) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research phases | Counts | ||||

| Problem identification | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Design and planning | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 11 |

| Implementation | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 12 |

| Evaluation | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Dissemination | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Sustainability | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Average number of phases (SD) | 4.8 (1.1) | 3.5 (0.7) | 3.0 (1.4) | 1.5 (0.7) | 3.5 (1.6) |

Data from published peer-reviewed literature and reports of 13 studies included in the systematic review are given.

SD, standard deviation.

Substudy: Surveys and Interviews

Studies and participants

Ten of 13 studies included in the review were eligible for the substudy,27–33,36–38 with three multisite studies excluded.34,35,39 Of the 10 researchers recruited, seven participated in the survey (4–23 minutes to complete) and interview (20–35 minutes) and three did not respond to recruitment efforts. Data were collected an average of 9 years (median: 9 years; range: 5–12 years) after the interventions concluded. Respondents' coalition roles included chair/leader (n = 4), member (n = 3), researcher/evaluator (n = 2), observer (n = 1), and meeting facilitator (n = 1). Three respondents reported dual roles of chair/leader and member.

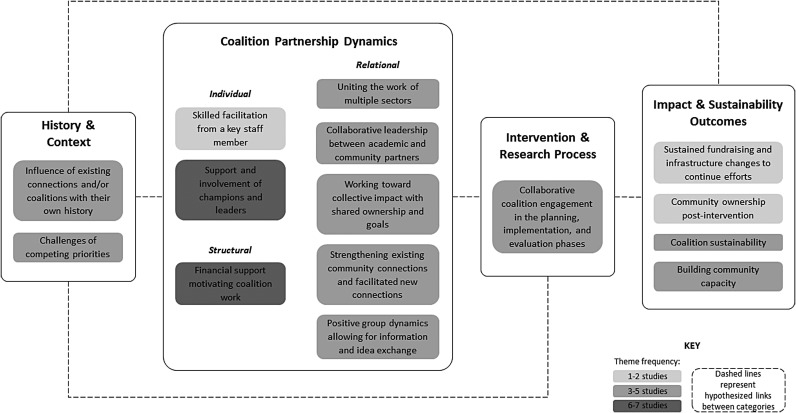

Figure 2 illustrates aggregated interview findings with 15 emergent themes presented as a guiding framework. Representative quotes for select themes are included in the narrative hereunder.

Figure 2. Qualitative interview themes, interpreted by the CBPR Conceptual Model.21–23 Data from interviews administered between April and July 2017: researchers (n = 7) of studies included in the systematic review. CBPR, Community-Based Participatory Research.

History and context

Survey respondents reported various reasons for having the coalition involved in the study, with project design/planning (n = 5) and implementation (n = 4) as the most common. Interviewees cited the importance of existing coalitions and community connections. One respondent explained:

It became very clear that in many of these smaller communities, all these folks had a history of interaction. You know, they've been on the job for a long time. And, they had ways of doing things that we probably weren't very much going to influence. There was history there.

Further, interviewees recalled challenges about competing priorities:

Yeah, I mean just some competing priorities in the community. So, you know, there were people working on elder services, and suicide prevention, you know really important things. But, it was hard to initially get people to understand how this could fit together and competition within a community always exists when there are limited resources… So, that's always a barrier doing community work.

Coalition partnership dynamics

Group dynamics were influenced by a variety of factors:

-

(i)

Coalition size and meeting frequency. Survey respondents reported varying coalition sizes: 5–10 (n = 3), 16–20 (n = 2), >20 members (n = 2). Meeting frequency varied: monthly (n = 2), every other month (n = 2), quarterly (n = 2), and unsure (n = 1). Most respondents estimated that about three-fourths of members attended each meeting (n = 5).

-

(ii)

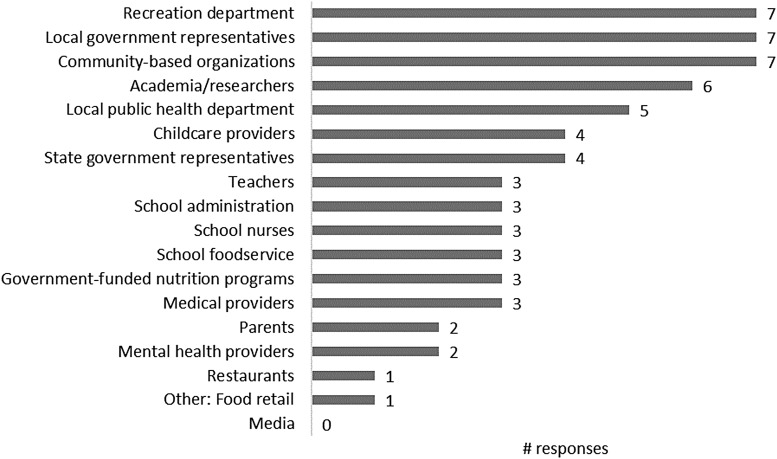

Membership. All survey respondents reported coalition representation from community-based organizations, recreation departments, and local government, with a total of 18 groups/sectors cited across studies (Fig. 3). Three respondents recalled that coalition membership changed throughout the study, with members leaving and being added. When asked to characterize the coalition composition, all respondents reported that coalitions represented various sectors or settings involved in the project. One respondent stated that ‘member demographics represented the target population.’

-

(iii)

Structural dynamics. Structural dynamics were influenced by financial support that progressed and motivated coalition efforts. Three of seven survey respondents recalled that coalitions had formal agreements (e.g., subcontracts and memorandums of understanding) to solidify the research partnership. Members of only one coalition received explicit monetary support (e.g., stipends and gift cards) to incentivize involvement.

-

(iv)

Individual dynamics. Interview participants recalled the importance of (a) community champions and leaders that garnered support for childhood obesity prevention efforts, and (b) key actors that coordinated and motivated intervention components, such as staff members skilled in facilitation:

Figure 3. Groups or sectors represented in community coalitions. Data from online survey administered between April and June 2017: researchers (n = 7) of studies included in the systematic review.

The nature of the coordinator was critically important, and having a good facilitating person with strong kind of community-building expertise.

-

(v)

Relational dynamics. Interviewees emphasized the importance of collaborative leadership between academic and community partners involved in the research, and further, the ability to strengthen existing connections and facilitate new connections. This contributed to collective impact with shared ownership and goals across settings and sectors:

The group dynamics were interesting in that everybody was actually committed to the cause, to the eventual objective. They saw it was a problem, they saw it was sitting in their area, that they had a role, that they wanted to see something done collectively. So, I think there was a coherence around what we were trying to achieve… I think in the end it was that, um, that common vision, I guess, and that energy that went towards, that carried it through all of the back and forth.

I remember we did have a lot of logos banging into each other, and they all wanted their little piece and their area and their objective… we kind of found ways where they can add things to the total and that the total becomes more than the sum of the parts was, I think, a part of the strategy.

This common vision and commitment may have facilitated knowledge sharing among coalition members. One respondent explained:

I think generally speaking, it was a pretty interactive group. They didn't just sit and listen, they were exchanging ideas and information, and I think generally speaking it was positive.

Survey respondents estimated that from 1 to 10, on average, coalition knowledge about childhood obesity prevention increased from intervention beginning [5.4 ± 2.1 (range: 3.0–9.0)] to end [8.7 ± 0.9 (8.0–10.0)]. Respondents also recalled increases in coalition engagement with the issue [5.9 ± 3.0 (2.0–10.0) to 8.7 ± 1.0 (7.0–10.0)].

Intervention and research process

Respondents emphasized coalition members' roles in the planning, implementation, and evaluation phases of the research. Major coalition functions frequently cited in the survey included networking (n = 6), priority decision-making (n = 6), and local public policy advocacy (n = 5). Common minor coalition functions included data collection (n = 4) and disseminating research findings (n = 4).

As explained by one interviewee, coalition study involvement was critical for adapting interventions to fit local contexts:

It meant that the intervention itself was tailored and we didn't miss the mark. And before we put any intervention out and rolled out any sort of intervention, we knew it was going to work because we talked it through with a number of really key and motivated providers in that area. And they were able to fine-tune it for us.

Impact and sustainability outcomes

All survey respondents reported that main achievements of coalitions included capacity building for the town/city and organizations involved (Fig. 4). Six of seven respondents recalled the coalition influencing social change about childhood obesity. Sentiments about sustained community ownership and capacity building were also expressed in interviews:

Figure 4. Main achievements of coalitions. Data from online survey administered between April and June 2017: researchers (n = 7) of studies included in the systematic review.

I think that the capacity-building was really huge. I think that particularly given the time and space, the fact that we were able to find secure funding and actually see projects and policies implemented in real time was huge… people were empowered to make changes, and they did.

Interview respondents recalled the importance of fundraising and infrastructure changes to sustain intervention efforts:

There were some things institutionalized within the town and the city as a result of the work: a walkability coordinator that became a permanent position, the [intervention] coordinator, and then the Mayor instituting a benefit for city employees around wellness and nutrition and fitness.

Interviewees also addressed coalition sustainability. Some respondents reported that coalitions continued to meet postintervention, whereas others viewed the coalition as a shorter term strategy to enhance study implementation:

These [coalitions] are really useful while a project is active, and they generally don't survive afterward because they don't have that facilitator anymore, but I don't think that means that they weren't useful… because I don't think that is part of the strategy that needs to be sustainable. I think it did its purpose: it helped with the planning and the intervention and the roll out of the project. It did its role and it did what it needed to do. So, I didn't actually need to see those groups being sustainable in their own right. I think what needs to be sustainable is the strategies you put in place and the actions that were in the ground.

When asked how important the coalition was to the study's success, all survey respondents selected the highest category, “extremely important”, from the five-point scale.

Discussion

Elements of CBPR were evident in each of the 13 community-based obesity prevention interventions included in the systematic review.27–39 Community engagement was most frequent in the intervention design/planning27–34,36–38 and implementation27–30,32–39 phases. Five interventions reported favorable findings related to anthropometric, behavioral, or environmental/policy outcomes;27–29,34,38 associations suggested that these interventions tended to have a higher level of community engagement compared with studies with mixed, null, or negative findings. Survey and interview results revealed a variety of individual and group-level attributes that influenced coalition work, including facilitation skills, leadership, and knowledge about childhood obesity prevention, exchange of information and ideas, and shared vision. Respondents perceived coalitions as extremely important to studies' successes, independent of research outcomes. Success may have been attributed to roles of coalitions in building community capacity and sustaining childhood obesity prevention efforts. Quotes from the interviews presented previously also highlight the role of coalitions in effectively tailoring and translating evidence-based intervention strategies to local context. Overall, results emphasize the dynamism of community coalitions and varied contributions to childhood obesity prevention intervention studies.

In 2016, Ewart-Pierce et al. summarized findings from 14 multilevel, multicomponent childhood obesity prevention interventions and concluded this approach holds promise in impacting child behavior and biology.24 The authors stated that “engaging various stakeholders” (page 362) was concomitant with the multifaceted approach, but provided little discussion of the mechanisms and contributions of stakeholder involvement. Current review findings contribute to this gap by providing detailed information about community engagement processes and dynamics. Findings offer support for stakeholder engagement in multisetting community interventions, but as described below, also elucidate the need for further research.

Using a CBPR framework, this research provides insight to contextual factors, coalition group dynamics, intervention processes, and perceived impacts of coalitions involved in childhood obesity prevention efforts. Findings are supported by a 2015 review by van der Kleij et al. reporting that successful implementation of multisector childhood obesity interventions require collaborative partnerships and human capital.13 By integrating review findings with original data collected in the substudy, the current research provides insight to factors that facilitate or inhibit implementation efforts.

Owing to eligibility criteria and search timing, some relevant studies were not included in this review (e.g., cited40–43 and discussed below). In a pilot Head Start intervention, parents and other community representatives served on an advisory board—“an intervention in of itself” (page 3)—aiming to empower members to address childhood obesity.44 Furthermore, relevant published protocols include the Ecological Model of Childhood Overweight study that engages coalitions in “Community Coaching” interventions to improve healthy eating and physical activity environments,45 and the Canadian Sustainable Childhood Obesity Prevention through Community Engagement initiative that investigates the impact of a multisetting CBPR intervention on childhood obesity outcomes.46

This review included the Spanish EPODE intervention, Programa Thao-Salud Infantil,35 but not other EPODE research [e.g., VIASANO47 (Belgium), OPAL48 (South Australia)], as these studies did not meet eligibility criteria during the latest database searches. Utilizing a local steering committee, EPODE's overarching community engagement approach leverages community connections, holds decision-making power, and implements intervention components.49

This study was challenged by the limited information available in the peer-reviewed literature about community coalitions engaged in childhood obesity prevention interventions. To address this gap, researchers should consider publishing greater detail about coalition involvement, perhaps in Supplementary Data if article word limits are prohibitive. Furthermore, rigorous research is needed, particularly studies examining how coalitions influence intervention processes (e.g., participant recruitment and retention and implementation), community-level change, and individual-level outcomes related to obesity risk, and to characterize how coalitions engage in different types of community-based studies (e.g., efficacy vs. effectiveness trials). By understanding such mechanisms, researchers and community partners can strengthen intervention design, implementation, evaluation, and sustainability by coordinating efforts within and across sectors, leveraging existing resources, and responding to local contexts.8,10 New, sensitive, and valid measurement tools and mechanistic models are likely needed to gain new insights into this understudied area, with the aim to understand why interventions do or do not succeed and what approaches may curb childhood obesity rates.50

Study strengths include rigorous search strategies in three electronic databases at two time points. To address the limited coalition information available in the published literature, review findings were complemented with original survey and interview data from intervention researchers. Because of the emphasis on coalition involvement, appraisal of study quality as traditionally assessed in reviews of controlled trials (e.g., bias, research design, and blinding) was deemed outside this research scope.

Several study limitations should be considered. To minimize heterogeneity, included interventions were conducted in high-income countries25 that targeted children aged 0–12 years: an important life stage for obesity prevention. These criteria may limit generalizability to interventions in developing nations and among adolescents. Findings were not summarized quantitatively because of the small number of included studies and variability in study design and outcomes. The review was not designed to compare intervention effectiveness with and without coalitions or to understand potential confounding factors (e.g., influence of coalitions on participant retention or intervention dose); therefore, only associations can be cited and conclusions about impact of coalitions on intervention outcomes cannot be made. As demonstrated by the limited information available in the peer-reviewed literature about community coalitions, included studies may be subject to selection bias despite the comprehensive database search terms used (Supplementary Appendix A). Some studies were not represented in the substudy because of a priori exclusion of multisite studies34,35,39 and nonresponse. Responses were perceptions of one intervention researcher and may reflect recall inaccuracies, although questions were designed to minimize guessing. The decision to invite researchers (vs. researchers and/or coalition members) to participate in the substudy was informed by feasibility concerns of acquiring current contact information of community members who historically served on coalitions and the desire to maximize data collected from one type of perspective, allowing for comparisons across studies.

Conclusions

Communities play a critical role in curbing the global childhood obesity epidemic.6,7 This systematic review examined how community coalitions engaged in 13 multisetting community-based interventions. Overall findings revealed leadership roles of coalitions in building relationships, structures, and capacity to implement strategies that promote children's healthy behaviors and weight trajectories. Further research is required to evaluate the impact of community coalitions on intervention implementation processes and child weight outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Amy LaVertu for helping to develop the database search strategies, and Sarah Andrus, Michelle Borges, and Brittany Peats for assisting with the searches and data extraction. The authors are grateful to the study participants who generously contributed their time and invaluable insights. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NHLBI and OBSSR, R01HL115485) and the Brookings Institution. The funders were not involved in the study conception, research design, data collection, analysis, manuscript writing, or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The views expressed in this article do not necessary represent the views of the US Government, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist. C.D.E. participated in the substudy as principal investigator of one of the studies included in the systematic review. The Tufts University Institutional Review Board approved her participation upon expectation of unbiased responses.

References

- 1. The National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine, Health and Medicine Division. Driving Action and Progress on Obesity Prevention and Treatment: Proceedings of a Workshop. National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGuire S. Institute of Medicine. 2012. Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: Solving the weight of the nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; Adv Nutr 2012;3:708–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bleich SN, Segal J, Wu Y, et al. Systematic review of community-based childhood obesity prevention studies. Pediatrics 2013;132:e201–e210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Population-Based Approaches to Childhood Obesity Prevention. Geneva, Switzerland, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khan LK, Sobush K, Keener D, et al. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2009;58:1–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bleich SN, Vercammen KA, Zatz LY, et al. Interventions to prevent global childhood overweight and obesity: A systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:332–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jernigan J, Kettel Khan L, Dooyema C, et al. Childhood obesity declines project: Highlights of community strategies and policies. Child Obes 2018;14(S1):S32–S39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Economos CD, Hammond RA. Designing effective and sustainable multifaceted interventions for obesity prevention and healthy communities. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017;25:1155–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. IOM (Institute of Medicine). Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gillman MW, Hammond RA. Precision treatment and precision prevention: Integrating “below and above the skin”. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:9–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Butterfoss FD, Goodman RM, Wandersman A. Community coalitions for prevention and health promotion. Health Educ Res 1993;8:315–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Butterfoss FD, Goodman RM, Wandersman A. Community coalitions for prevention and health promotion: Factors predicting satisfaction, participation, and planning. Health Educ Q 1996;23:65–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van der Kleij R, Coster N, Verbiest M, et al. Implementation of intersectoral community approaches targeting childhood obesity: A systematic review. Obes Rev 2015;16:454–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Economos C, Blondin S. Obesity interventions in the community: Engaged and participatory approaches. Curr Obes Rep 2014;3:199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zakocs RC, Edwards EM. What explains community coalition effectiveness?: A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 2006;30:351–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Woulfe J, Oliver TR, Zahner SJ, Siemering KQ. Multisector partnerships in population health improvement. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7:A119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roussos ST, Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu Rev Public Health 2000;21:369–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wendel ML, Burdine JN, McLeroy KR, et al. Community capacity: Theory and application. In: DiClemente R, Crosby R, Kegler M. (eds), Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research, 2nd ed. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, 2009, pp. 277–302 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, et al. What predicts outcomes in CBPR? In: Meredith Minkler NW. (ed), Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes, 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, 2008, pp. 371–388 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health 2010;100 Suppl 1:S40–S46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research. CBPR Model. Available at https://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cpbr-project/cbpr-model.html Last accessed December4, 2017

- 24. Ewart-Pierce E, Mejía Ruiz MJ, Gittelsohn J. “Whole-of-community” obesity prevention: A review of challenges and opportunities in multilevel, multicomponent interventions. Curr Obes Rep 2016;5:361–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. The World Bank Group. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519%20-%20High_income Last accessed September26, 2017

- 26. Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, et al. Community-based participatory research: Lessons learned from the Centers for Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect 2005;113:1463–1471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Benjamin Neelon SE, Namenek Brouwer RJ, Ostbye T, et al. A community-based intervention increases physical activity and reduces obesity in school-age children in North Carolina. Child Obes 2015;11:297–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chomitz VR, McGowan RJ, Wendel JM, et al. Healthy Living Cambridge Kids: A community-based participatory effort to promote healthy weight and fitness. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18 Suppl 1:S45–S53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Goldberg JP, et al. A community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: Shape up somerville first year results. Obesity 2007;15:1325–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gentile DA, Welk G, Eisenmann JC, et al. Evaluation of a multiple ecological level child obesity prevention program: Switch what you do, view, and chew. BMC Med 2009;7:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gombosi RL, Olasin RM, Bittle JL. Tioga County fit for life: A primary obesity prevention project. Clin Pediatr 2007;46:592–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Olson CM, Baker IR, Demment MM, et al. The healthy start partnership: An approach to obesity prevention in young families. Fam Community Health 2014;37:74–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sadeghi B, Kaiser LL, Schaefer S, et al. Multifaceted community-based intervention reduces rate of BMI growth in obese Mexican-origin boys. Pediatr Obes 2017;12:247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Subica AM, Grills CT, Villanueva S, Douglas JA. Community organizing for healthier communities: Environmental and policy outcomes of a national initiative. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:916–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gomez Santos SF, Estevez Santiago R, Palacios Gil-Antunano N, et al. Thao-Child Health Programme: Community based intervention for healthy lifestyles promotion to children and families: results of a cohort study. Nutr Hosp 2015;32:2584–2587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. de Silva-Sanigorski AM, Bell AC, Kremer P, et al. Reducing obesity in early childhood: Results from Romp & Chomp, an Australian community-wide intervention program. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:831–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pettman T, Magarey A, Mastersson N, et al. Improving weight status in childhood: Results from the eat well be active community programs. Int J Public Health 2014;59:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sanigorski AM, Bell AC, Kremer PJ, et al. Reducing unhealthy weight gain in children through community capacity-building: Results of a quasi-experimental intervention program, Be Active Eat Well. Int J Obes 2008;32:1060–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. De Henauw S, Huybrechts I, De Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. Effects of a community-oriented obesity prevention programme on indicators of body fatness in preschool and primary school children. Main results from the IDEFICS study. Obes Rev 2015;16 Suppl 2:16–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Choudhry S, McClinton-Powell L, Solomon M, et al. Power-up: A collaborative after-school program to prevent obesity in African American children. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2011;5:363–373 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Samuels SE, Craypo L, Boyle M, et al. The California Endowment's Healthy Eating, Active Communities program: A midpoint review. Am J Public Health 2010;100:2114–2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berge JM, Jin SW, Hanson C, et al. Play it forward! A community-based participatory research approach to childhood obesity prevention. Fam Syst Health 2016;34:15–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Johnson-Shelton D, Moreno-Black G, Evers C, Zwink N. A community-based participatory research approach for preventing childhood obesity: The communities and schools together project. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2015;9:351–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Davison KK, Jurkowski JM, Li K, et al. A childhood obesity intervention developed by families for families: Results from a pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peters P, Gold A, Abbott A, et al. A quasi-experimental study to mobilize rural low-income communities to assess and improve the ecological environment to prevent childhood obesity. BMC Public Health 2016;16:376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Amed S, Naylor PJ, Pinkney S, et al. Creating a collective impact on childhood obesity: Lessons from the SCOPE initiative. Can J Public Health 2015;106:e426–e433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vinck J, Brohet C, Roillet M, et al. Downward trends in the prevalence of childhood overweight in two pilot towns taking part in the VIASANO community-based programme in Belgium: Data from a national school health monitoring system. Pediatr Obes 2016;11:61–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bell L, Ullah S, Olds T, et al. Prevalence and socio-economic distribution of eating, physical activity and sedentary behaviour among South Australian children in urban and rural communities: Baseline findings from the OPAL evaluation. Public Health 2016;140:196–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Borys JM, Le Bodo Y, Jebb SA, et al. EPODE approach for childhood obesity prevention: Methods, progress and international development. Obes Rev 2012;13:299–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Korn AR, Hennessy E, Hammond RA, et al. Development and testing of a novel survey to assess Stakeholder-driven Community Diffusion of childhood obesity prevention efforts. BMC Public Health 2018;18:681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bell AC, Simmons A, Sanigorski AM, Kremer PJ, Swinburn BA. Preventing childhood obesity: the sentinel site for obesity prevention in Victoria, Australia. Health Promotion International 2008;23:328–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Must A, et al. Shape Up Somerville two-year results: a community-based environmental change intervention sustains weight reduction in children. Preventive Medicine 2013;57:322–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. de Groot FP, Robertson NM, Swinburn BA, de Silva-Sanigorski AM. Increasing community capacity to prevent childhood obesity: challenges, lessons learned and results from the Romp & Chomp intervention. BMC Public Health 2010;10:522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pettman T, McAllister M, Verity F, et al. Eat Well Be Active Community Programs Final Report. SA Health, Adelaide; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gantner LA, Olson CM. Evaluation of public health professionals' capacity to implement environmental changes supportive of healthy weight. Evaluation and Program Planning 2012;35:407–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. de la Torre A, Sadeghi B, Green RD, et al. Ninos Sanos, Familia Sana: Mexican immigrant study protocol for a multifaceted CBPR intervention to combat childhood obesity in two rural California towns. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gomez SF, Casas R, Palomo VT, Martin Pujol A, Fito M, Schroder H. Study protocol: effects of the THAO-child health intervention program on the prevention of childhood obesity - the POIBC study. BMC Pediatrics 2014;14:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pigeot I, Baranowski T, De Henauw S, and the IDEFICS Intervention Study Group, on behalf of the IDEFICS consortium. The IDEFICS intervention trial to prevent childhood obesity: design and study methods. Obes Rev 2015;16 Suppl 2:4–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Martinie A, Brouwer RJ, Neelon SE. Mebane on the move: a community-based initiative to reduce childhood obesity. North Carolina Medical Journal 2012;73:382–383 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Eisenmann JC, Gentile DA, Welk GJ, et al. SWITCH: rationale, design, and implementation of a community, school, and family-based intervention to modify behaviors related to childhood obesity. BMC Public Health 2008;8:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Subica AM, Grills CT, Douglas JA, Villanueva S. Communities of Color Creating Healthy Environments to Combat Childhood Obesity. Am J Public Health 2016;106:79–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.