Abstract

Refractoriness to ruxolitinib in patients with myelofibrosis (MF) was associated with clonal evolution; however, whether genetic instability is promoted by ruxolitinib remains unsettled. We evaluated the mutation landscape in 71 MF patients receiving ruxolitinib (n = 46) and hydroxyurea (n = 25) and correlated with response. A spleen volume response (SVR) was obtained in 57% and 12%, respectively. Highly heterogenous patterns of mutation acquisition/loss and/or changes of variant allele frequency (VAF) were observed in the 2 patient groups without remarkable differences. In patients receiving ruxolitinib, driver mutation type and high-molecular risk profile (HMR) at baseline did not impact on response rate, while HMR and sole ASXL1 mutations predicted for SVR loss at 3 years. In patients with SVR, a decrease of ≥ 20% of JAK2V617F VAF predicted for SVR duration. VAF increase of non-driver mutations and clonal progression at follow-up correlated with SVR loss and treatment discontinuation, and clonal progression also predicted for shorter survival. These data indicate that (i) ruxolitinib does not appreciably promote clonal evolution compared with hydroxyurea, (ii) VAF increase of pre-existing and/or (ii) acquisition of new mutations while on treatment correlated with higher rate of discontinuation and/or death, and (iv) reduction of JAK2V617F VAF associated with SVR duration.

Introduction

Ruxolitinib is a JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of intermediate and high-risk patients with primary (PMF) and post-polycythemia vera (PPV-MF) and post-essential thrombocythemia (PET-MF) myelofibrosis1,2. Long-term follow-up studies have confirmed its efficacy in inducing rapid improvements in splenomegaly, disease-associated symptomatology and overall quality of life3, while the impact on overall survival3–7 remains debated7–9. Furthermore, a true disease-modifying effect is questioned, since only a minority of the patients experience significant molecular responses and reduction of bone marrow fibrosis10,11. In spite of rapid, sometimes dramatic, clinical benefits, at least 50% of the patients become overtly refractory to ruxolitinib or experience progressively increase of spleen volume or reappearance of symptoms, necessitating soon or later discontinuation of therapy. In the COMFORT-I and COMFORT-II phase 3 trials, discontinuation due to loss of response, disease progression and treatment-related adverse events involved ≈50% of the patients at 3 years and 75% at 5 years12–15. Discontinuation of ruxolitinib because of loss of response was associated with dismal outcome among 107 patients enrolled in a phase 1/2 study, with median survival after discontinuation of only 14 months16. Managing patients who fail ruxolitinib therapy may be challenging especially when stem cell transplantation is not feasible, and options include alternative JAK inhibitor therapy, alone or in combination, in the setting of clinical trials, novel agents, splenectomy, other palliative approaches17.

There is yet no mechanistic explanation for the development of resistance to ruxolitinib18. Advocated mechanisms include reactivation of JAK/STAT signaling by JAK heterodimer formation19, protective effects of cytokines20,21, incomplete target inhibition by type I JAK inhibitor as is ruxolitinib21, while acquired activating JAK2 mutations have been described in cell lines but not yet reported in patients22,23.

To date few studies have investigated the molecular variable that may be associated with response and durability of response to ruxolitinib. We reported that type of driver mutations and presence of HMR mutations at baseline, were indifferent as regards the obtainment of clinical responses (SVR and symptomatic improvement) at week 24 and week 48 in the COMFORT-II trial24. On the other hand, it was suggested that a JAK2V617F variant allele frequency (VAF) > 50% was associated with greater likelihood of SVR25. On the other hand, in a series of a long-term treated patients included in a phase 1/2 trial and analyzed by NGS panel of 28 non-driver recurrently mutated genes, the number of non-driver mutations at baseline had an impact on SVR; patients with 2 or less mutations had nine-fold higher odds of achieving SVR than those with 3 or more mutations, who also had shorter time to discontinuation of therapy26. A shorter time to treatment failure was also noticed in a study of 100 patients, including 23 treated with momelotinib, in association with an HMR profile and presence of ASXL1 and EZH2 mutations27. More recently, among 86 patients receiving ruxolitinib for a median of 79 months, clonal evolution, hallmarked by acquisition of new mutations under treatment, was associated with significantly shorter survival after therapy discontinuation compared to patients without clonal evolution16.

The purpose of our study was to analyze first, whether attainment and duration of clinical responses in patients with MF receiving ruxolitinib in a real-life setting was associated with unique mutation landscape at baseline and/or changes of mutation profile and VAF at follow-up, and whether clonal evolution might be attributed directly to selective pressure induced by ruxolitinib on pre-existing clones and/or through the facilitation of emergence of new mutated clones, in comparison with standard therapy represented by hydroxyurea.

Materials and methods

Patients

Seventy-one patients (42 with PMF, 29 with PPV/PET-MF) in active follow-up at our Institution were included. Diagnosis of PMF fulfilled the 2016 revised World Health Organization (WHO) criteria28,29 while criteria of the International Working group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT) were used for the diagnosis of PPV-MF and PET-MF30. Twenty-five patients (19 PMF, 6 PPV/PET-MF) were treated with hydroxyurea (HU) and 46 (23 PMF, 23 PPV/PET-MF) with ruxolitinib in a real-life setting. The study inclusion criteria for patients receiving ruxolitinib and HU were: (1) to have been treated continuously with the drug for at least 1 year and (2) to have stored a “baseline” blood sample (at the time of treatment start) and a “follow-up” sample collected at least one year later that, for patients who discontinued, was coincident with treatment discontinuation. Patients treated with HU were randomly selected from our database to match, in terms of diagnosis, clinical characteristics and follow-up criteria, the patients receiving ruxolitinib; all included patients had to be DIPSS intermediate-2/high risk and have a baseline spleen that was palpable at > 5 cm from the left costal margin (LCM). The dose of HU was according to clinical practice and according to the label for ruxolitinib; both drugs were titrated depending on clinical and hematologic criteria and toxicity. There was no hold of treatment in either group during the study period. All patients provided written informed consent to participate to the study, sponsored by AGIMM (AIRC- Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative) and supported by MYNERVA (Myeloid Neoplasms Research Venture-AIRC) project; the study was approved by local Ethical Committee.

Definitions of clinical response and outcome

Response of symptoms or splenomegaly was according to the IWG-MRT/ELN criteria31. A spleen response was adjudicated in case a spleen extending 5 to 10 cm from the LCM at baseline became no palpable or a spleen that was > 10 cm decreased by ≥ 50%. A symptoms response was considered in case of a > 50% reduction of the MPN-SAF Total Symptom Score (MPN-SAF TSS)32. Time to clinical response and to response loss was calculated from baseline to the date of achieving or loosing, respectively, the above criteria of spleen and/or symptoms response. Overall survival was calculated from the first day of treatment to the last follow-up or death. Time to discontinuation was calculated from the date of treatment start to the date of therapy discontinuation.

Methods

All patients were annotated for driver mutations and an additional panel of 24 “myeloid” genes by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). Mutational analysis was performed on high-quality DNA obtained from density gradient-purified granulocytes from peripheral blood. Samples were collected before starting HU/ruxolitinib therapy (baseline) and at different time points thereafter; the last available sample (“follow-up” -FU- sample for the purpose of this study) was collected at least one year later for patients who were still receiving the drug (in case of patients with sustained response), or at therapy discontinuation for patients who discontinued because of no response/loss of response.

JAK2V617F and MPL W515 L/K mutations were detected by real time (RT)-qPCR33,34 and high-resolution melting analysis (HRMA)35 followed by bidirectional Sanger sequencing36, respectively. CALR mutations were identified by bidirectional sequencing and capillary electrophoresis (CE) and classified as type 1/like or type 2/like, as described37,38. CALR amplification was carried out with a 6-FAM-labeled forward primer followed by fragment analysis on a ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyser (GeneMapper Software 4.1; Applied Biosystems, Forest City, CA, USA). All samples with an additional peak to the wild-type one were further evaluated by direct Sanger sequencing. The level of detection was < 0.1% for JAK2V617F mutations and 1% for MPLW515 mutations using RT-qPCR and HRMA, respectively, and 1% by capillary electrophoresis for CALR mutations.

High molecular risk mutations (HMR; ASXL1, EZH2, SRSF2, IDH1, IDH2) and other myeloid-neoplasm associated gene mutations (CBL, C-KIT, CSF3R, CUX1, DNMT3A, ETNK1, IKZF1, KRAS, NFE2, NRAS, PTPN11, RUNX1, SETBP1, SH2B3, SF3B1, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, ZRSR2), as well as the entire coding regions of JAK2 and MPL, were evaluated by using a custom panel for NGS on Ion Torrent PGM platform (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachussets, USA). NGS raw reads were aligned against the GRCh38/hg38 using NextGENe® software 2.4.2 for variants call with a variant allele frequency (VAF) threshold of ≥ 2%, in case of previously unreported mutations, and ≥ 1% for known hotspots, and depth of coverage of at least 100 × (SoftGenetics, LLC, State College, PA). Mutations in the exonic regions were filtered by available databases (dbSNP, COSMIC, 1000 genome, ExAC); protein function predictor algorithms (Polyphen2, SIFT, MutationTester, FATHMM, Gerp) were used to predict functional relevance of mutations, and only indels and pathogenetic variants were considered. An HMR category was defined by the presence of ≥ 1 of HMR genes mutations; patients lacking these mutations were defined at “low molecular risk” (LMR). For the analysis, we recorded any modification of VAF, either decreasing or increasing, that had a magnitude of at least 20% compared to baseline. Mutations were defined “acquired” in case of de novo detection ( ≥ 2% VAF) and “lost” in case the VAF of a mutation detected became less than 0.1%.

Statistical analysis

Best overall response of splenomegaly was adjudicated at any time while the patients was on continuous drug administration using the IWG-MRT/ELN revised criteria31; assessment at 24 and 48 weeks was also performed, as in the COMFORT trials. Response of symptoms was annotated at any time point between baseline and 48 weeks. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables were compared using Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Comparison of response to ruxolitinib across molecular categories was tested for homogeneity of distributions using chi-square test. Survival time estimates, including survival curves by response status, were obtained with the Kaplan-Meier method; the hazard ratio (HR) was determined using a Cox proportional hazards model. All P values are 2-tailed and were considered significant when P < .05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.25 (IBM).

Results

Patients’ characteristics at baseline

Patients’ characteristics at baseline are reported in Table 1; forty-six patients received ruxolitinib (ruxo-patients) and 25 patients received hydroxyurea (HU-patients). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding main clinical and laboratory parameters (Table 1), a part for a greater proportion of patients with larger ( > 10 cm from LCM) splenomegaly among the ruxo-patients compared to HU-patients (76.1% vs. 40.0%; P < .0001). The median follow-up duration from the initiation of therapy was 3.4 years (range, 1.0–7.4; P = .981) in patients receiving ruxolitinib and 2.9 years (range, 1.0–11.1) in HU-patients. The proportion of study patients who had a follow-up sample collected at > 5 years of treatment was 36.0% and 34.8% for ruxolitinib and HU, respectively (P = .897). Over the study period, 11 of 46 (23.9%%) ruxo-patients discontinued therapy for loss of response, 1 patient (2.2%) progressed to acute leukemia and 20 patients (43.5%) died; fifteen patients (32.6%) were still receiving ruxolitinib at latest follow-up. In the HU group, 10 patients (40.0%) died during the follow-up, one (4.0%) of which had progressed to acute leukemia, while 15 (60%) were still on therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and hematologic characteristics of study patients stratified according to the treatment

| Variables | Ruxo-patients (N = 46) | HU-patients (N = 25) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis, n.(%) | |||

| PMF | 23 (50.0) | 19 (76.0) | .050 |

| PPV-MF | 16 (35.0) | 2 (8.0) | |

| PET-MF | 7 (15.0) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Follow-up from the start of treatment, y: median (range) | 3.4 (1.0–7.4) | 2.9 (1.0–11.1) | .981 |

| Time from diagnosis to treatment | 1.1 (0.3.6) | 2.8 (0–3.7) | .743 |

| Males, n (%) | 22 (48.0) | 15 (60.0) | .232 |

| Age, y; median (range) | 63.4 (35.0–81.0) | 66.9 (43.0–88.0) | .087 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L; median (range) | 107 (70–140) | 99 (89–109) | .912 |

| Leukocytes, x109/L; median (range) | 13.3 (3.0–103.0) | 11.8 (5.8–14.0) | .917 |

| Platelets, x109/L; median (range) | 333 (52–750) | 433 (227–1378) | .090 |

| Circulating blasts ≥ 1%; n (%) | 12 (26.1) | 7 (28.0) | .993 |

| Constitutional symptoms; n (%) | 43 (93.5) | 21 (84.0) | .558 |

| Splenomegaly > 10 cm from LCM; n (%) | 35 (76.1) | 10 (40.0) | <.0001 |

| Patients with cytogenetic information; N = (% of total) | 42 (91.3) | 21 (84.0) | .202 |

| Abnormal cytogenetics | 19 (45.2) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Unfavorable karyotype | 4 (9.5) | 2 (9.5) | |

| DIPSS | |||

| Intermediate-2 | 40 (86.9) | 20 (80.0) | .441 |

| High | 6 (13.1) | 5 (20.0) | |

Note: Unfavorable karyotype indicates any of the following: + 8, –7/7q–, i(17q), inv(3), –5/5q, 12p–, or 11q23 rearrangements. DIPSS, Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System. DIPSS uses five independent predictors of inferior survival: age > 65 years, hemoglobin < 10 g/dL, leukocytes > 25 × 109/L, circulating blasts ≥ 1%, constitutional symptoms, resulting in four (low, intermediate-1, intermediate-2 and high) risk categories

Mutation landscape at baseline

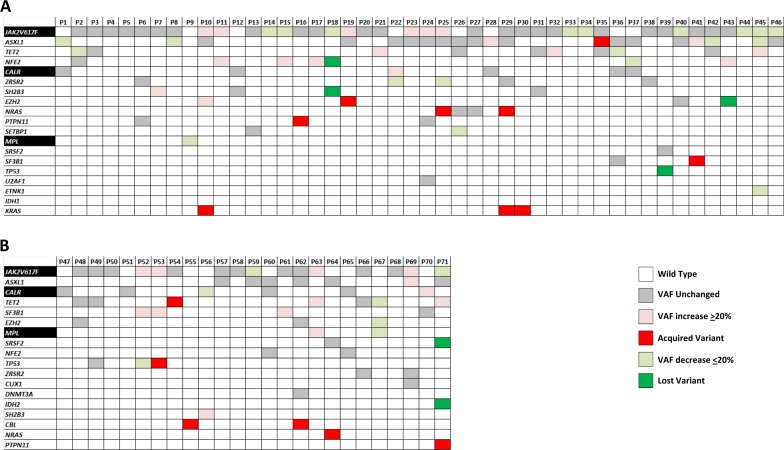

The mutation landscape of patients at baseline is shown in Fig. 1. A JAK2V617F mutation was found in 54 patients (76.0% of total; 82.6% of ruxo-patients and 64% of HU-patients), CALR mutation in 12 (16.9%; 13% of ruxo-patients and 24% of HU-patients), of which 10 (83%) were Type 1 and 2 (17%) Type 2, MPL mutations in 3 patients (1 in the ruxo-group and 2 in the HU-group); 1 patient in each cohort was triple negative. Non-driver mutations represented at > 5% in the series were ASXL1 (36.6%; 41.3% of ruxo-patients and 28.0% of HU-patients), TET2 (22.5%; 21.7% of ruxo-patients and 24.0% of HU-patients), NFE2 (12.6; 15.2% of ruxo-patients and 8.0% of HU-patients), ZRSR2 (11.7%; 11.6% of ruxo-patients and 11.8% of HU-patients), EZH2 (8.5%; 6.5% of ruxo-patients and 12.0% of HU-patients), SF3B1 (7.0%; 2.2% of ruxo-patients and 16.0% of HU-patients), SH2B3 (7.0%; 8.7% of ruxo-patients and 4.0% of HU-patients). Mutations of TP53 were found in 3 patients (4.2%), 2 of whom were in the HU-group. No mutation was found in CBL, C-KIT, CSF3R, CUX1, DNMT3A, IKZF1, RUNX1, IDH2. Considering all non-driver mutated genes evaluated, a total of 54 patients (76%) showed at least one somatic variant: 36 in the ruxo-group (78.3%) and 18 (72.0%) in the HU-group; 2 or more mutations were found in 19 ruxo-patients (41.3%) and 9 HU-patients (36.0%); 3 or more mutations were harbored by 4 ruxo-patients (8.7%) and 2 HU-patients (8.0%). A total of 30 patients (42.2%) were considered at high-molecular risk (HMR), including 21 in the ruxo-group (45.6%) and 9 (36.0%) in the HU group; 2 or more HMR mutations were found in 5 patients (7.0%), of which 2 in the ruxo-group (8.0%) and 3 in HU-patients (12%). With the limitation of small numbers, we compared rate of non-driver mutations in patients with PMF vs. PPV/PET MF. A total of 78.6% of PMF vs. 72% of PPV/PET MF patients had ≥ 1 mutation (p = 0.58), and 40.5% of PMF vs. 44.8% of PPV/PET-MF were HMR+.

Fig. 1. Landscape plot of mutations in the study population.

Each column represents an individual patient. a: ruxolitinib treated patients; b: HU-treated patients. color code: gray indicates a mutation detected at baseline that remained unchanged at the latest follow-up sample; pink colour indicates a mutation whose VAF increased of at least 20% compared to baseline; red colour indicates a newly acquired mutation at follow-up; light green colour indicates a mutation whose VAF decreased of at least 20% compared to baseline; green colour indicates a mutation that, while detected at baseline, was no longer detected in the follow-up sample

Mutation landscape at follow-up sample

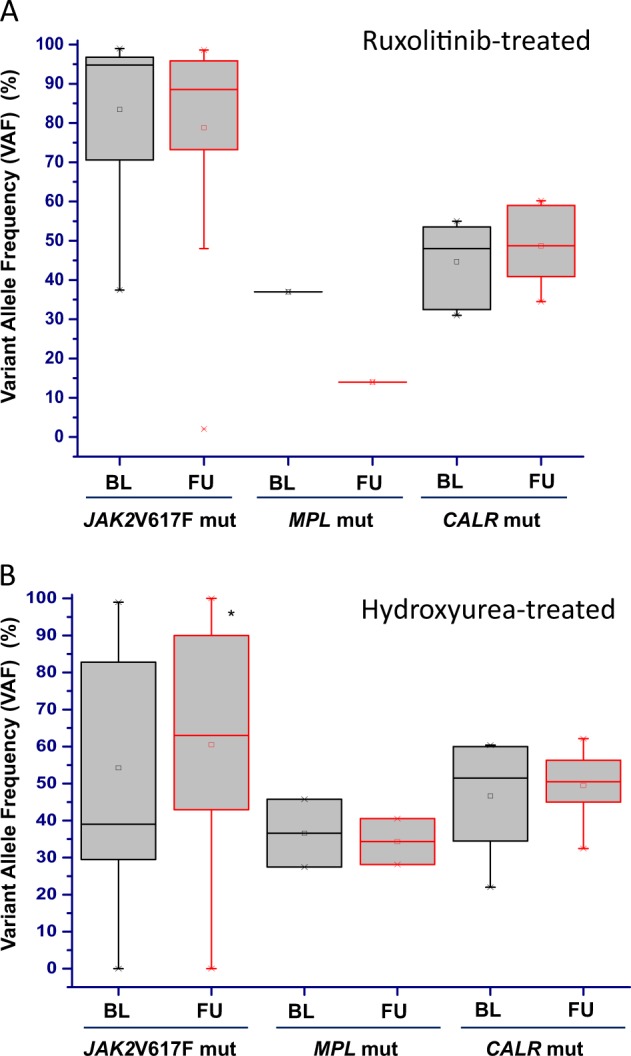

In the follow-up sample of patients receiving ruxolitinib, a change, either increase or decrease (see Materials and Methods for definition) of the VAF of any mutation (driver and non-driver) detected at baseline was detected in 41.3% and 34.8%, respectively (Fig. 1, panel A). Concerning driver mutations (Fig. 2, panel A), the JAK2V617F VAF overall decreased from 83.4 ± 19.3% to 78.8 ± 25.3% (P = .43): in detail, the VAF increased in 6 patients (15%; median increase + 27%, range + 20% to + 50%) and decreased in 9 (23%; median −39%, range −21 to −62%); CALR VAF showed a slight, not significant increase from 44.7 ± 10.6% to 48.7 ± 10.3% (P = .52): in detail it increased by 32% in 1 patient and remained unchanged in 5 patients; in the one MPL mutated patient, the VAF decreased from 37 to 14% (−38%). As regards non-driver mutations (Fig. 1, panel A), the VAF overall increased in the follow-up sample in 11 patients (24% of all mutated patients) by a median value of 104%, ranging from + 20% to + 480%, compared to baseline one. The involved genes were NFE2 (number of variants = 4), TET2 (number of variants = 3), ASXL1 (number of variants = 2), SH2B3 and EZH2 (one variant each). On the contrary, the VAF decreased in 10 patients (22%) by a median of 30% (−23% to −69%); the involved genes were ASXL1 (number of variants = 4), TET2 and ZRSR2 (2 variants each), NFE2, SETBP1, and ETNK1 (1 variant each). Four mutations detected at baseline in 3 patients (6.5%; Fig. 1, panel A), involving EZH2, NFE2, SH2B3, and TP53, were no longer detected in the follow-up sample. Conversely, acquisition of a new mutation was observed in 8 cases (17.4%; Fig. 1, panel A), involving EZH2, SF3B1, ASXL1, PTPN11 (one each), NRAS (2 cases), and KRAS (3 cases), in one case concurrently with acquisition of a NRAS mutation. Of note, acquisition of novel mutations was observed only in JAK2V617F mutated patients compared to no CALR mutated patients.

Fig. 2. Changes of driver mutation variant allele frequency (VAF) over study period.

The VAF of the JAK2V617F, MPLW515x and CALR driver mutation was measured in samples collected at baseline (BL) and at the latest available follow-up (FU) in patients receiving ruxolitinib (a) and hydroxyurea (b)

Among patients receiving HU, an increase or a decrease of the VAF of any baseline mutation (driver and non-driver) was detected in 20.8% and 33.3%, respectively (Fig. 1, panel B). Concerning the driver mutations (Fig. 2, panel B), the JAK2V617F VAF overall increased from 54.2 ± 20.3% to 60.5 ± 22.7% (P = .59), in detail, the VAF increased in 4 patients (16%, range + 33% to + 88%) and decreased in 2 patients by 41% and 63%, respectively. In CALR and MPL mutated patients the VAF increased in 1 case and decreased in 1 case each (Fig. 2, panel B). As regards non-driver mutation (Fig. 1, panel B), the VAF overall increased in 7 patients (28% of all mutated patients) by a median + 94.9% (range + 22.8% to + 174%) in the follow-up sample compared to baseline one; the involved genes were SF3B1 and TET2 (number of variants = 2), ASXL1 and SH2B3, (1 variant each). On the contrary, the VAF decreased in 2 patients (8%), the genes involved were TP53 (−65%) and TET2 (−50%). One patient showed disappearance of baseline mutation in SRSF2 and IDH1 (VAF of 6.3% and 8.2%, respectively), while acquisition of new mutation at follow-up sample occurred in 6 patients (24%); involved genes were TET2, TP53, NRAS, PTPN11 and CBL (in 2 patients) (Fig. 1, panel B). Acquisition of novel mutation was observed in four JAK2V617F mutated patients and in 2 triple negative patients, compared to no patients with CALR mutation.

Clonal progression occurred in 21.4% of PMF vs. 17.2% of PPV/PET MF (P = .66).

Correlation of mutation landscape at baseline with clinical response

Among patients receiving ruxolitinib, response of symptoms and splenomegaly (by IWG-MRT/ELN criteria31) was achieved by 78 and 57% of the patients after a median of 2.0 months (range, 1–37 months) and 5.8 months, respectively (range, 1–49 months); of these, 11 (31%) and 12 (30.8%) patients lost clinical response after a median of 2.4 years (range, 0.5–5.2) for symptoms and 1.8 years for SVR (range, 0.7–5.0). Since in the HU group only 1 (4%) and 3 (12%) patients had achieved symptoms and spleen response, respectively, at any time during follow-up, further analysis was restricted to patients treated with ruxolitinib.

We found no difference in the proportion of patients with JAK2V617F mutation vs. patients with CALR mutation who achieved either a spleen or symptom response, confirming previous reports; a SVR and/or a symptom response was obtained by 54.1% and 86.0% of JAK2V617F mutated patients compared to 66.7% and 60.0% of CALR mutated patients. There was also no difference in terms of SVR and/or a symptom response among patients with a JAK2V617F VAF greater or lower than 50%.

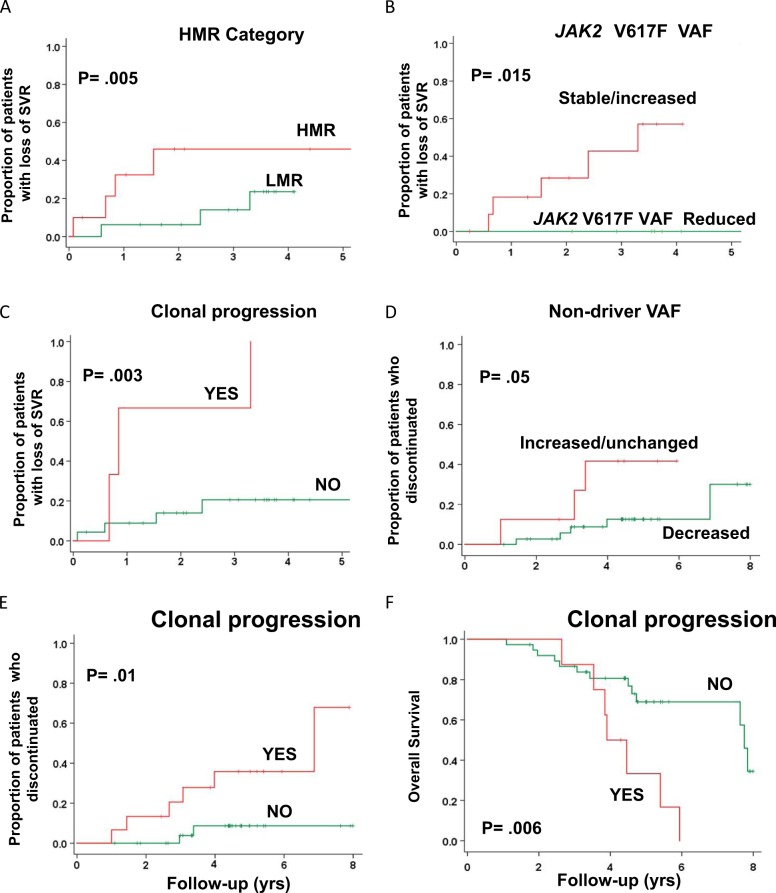

Presence of an HMR status at baseline did not affect the likelihood of obtaining SVR or symptom response, as we previously reported24. A spleen response was obtained by 42.9% of HMR patients compared to 44.0% of the LMR counterpart at 24 weeks, and 42.8% compared to 56.0% at 48 weeks; the best overall spleen response rate was 51% and 64%, respectively. The rate of symptoms response was 68.4% in HMR patients compared to 64.0% in un-mutated patients at 24 weeks, and 73.7% compared to 76.0% at 48 weeks. On the other hand, baseline HMR status was significantly associated with loss of SVR, with a HR of 3.6 (95%CI, 12.0–16.7; P = .005) compared to LMR patients (Fig. 3, panel A); at 3 years, 14% of LMR patients had lost spleen response compared to 46% of the HMR category (P = .005). There was no difference in rate of symptom response depending on HMR vs. LMR status.

Fig. 3. Correlation of mutation profile, at baseline and during follow-up, with maintenance of spleen volume response, treatment duration and outcome in patients receiving ruxolitinib.

Kaplan-Meyer estimates of the proportion of patients treated with ruxolitinib who presented loss of spleen response, according to IWG-MRT criteria, are shown in panels a–d in relation to: a HMR status at baseline (a); modifications of JAK2 V617F VAF at latest follow-up compared to baseline (b); clonal progression, considered as the appearance of a novel somatic variant in the follow-up sample (c); modifications of the VAF of any non-driver mutation al follow-up sample compared to baseline (d). Kaplan-Meyer estimates of the proportion of patients who discontinued ruxolitinib in relation to acquisition of clonal progression at follow-up sample are shown in e. f shows Kaplan-Meyer estimates of overall survival, measured from therapy initiation in patients treated with ruxolitinib depending on the acquisition of clonal progression in the follow-up sample

We also analyzed the impact of sole ASXL1 mutations at baseline, the most frequently mutated gene, on response. Presence of ASXL1 mutation at baseline did not impact on the rate of spleen or symptom response. A spleen response was obtained by 47.4% of ASXL1- mutated patients compared to 40.7% of the un-mutated counterpart at 24 weeks, and 47.0% compared to 51.9% at 48 weeks. Symptoms response was achieved by 64.7% of ASXL1 mutated patients compared to 66.7% at 24 weeks, and 70.6% compared to 77.8% at 48 weeks. Furthermore, presence of sole ASXL1 mutation was associated with a significantly shorter duration of spleen volume reduction; the probability of maintaining a spleen response at 3 years among ASXL1 mutated patients was 33% compared to 87% of un-mutated patients (P = .009).

Impact of clonal evolution at follow-up on clinical response

A decrease of the JAK2V617F VAF at any time point during treatment was significantly associated with maintenance of SVR (P = .015); in fact, none of the 7 patients who showed decrease of ≥ 20% from baseline JAK2V617F VAF lost SVR compared to 6 out of 13 (46.1%) who showed stable or increased JAK2V617F VAF (HR = 61.8, 95% CI 1.01–870.2; Fig. 3, panel B). Similar analysis could not be done for CALR mutated patients, owing that there was no significant modification of CALR VAF during follow-up.

We found that loss of SVR was significantly associated with clonal progression, ie the acquisition of ≥ 1 novel mutation in any non-driver genes during follow-up; all patients with SVR loss during follow-up had evidence of clonal progression compared to 21% who lost SVR without having clonal progression (P = .006). Patients with clonal progression had median duration of SVR of 10 months (range, 8.4–13.0 month) compared to not-reached in patients without clonal progression (HR 7.2, 95% CI, 1.6–33.0; P = .003) (Fig. 3, panel C). A greater rate of therapy discontinuation due to SVR loss was found in patients showing VAF increase of any baseline mutation; at 4 years of treatment, the proportion of patients who discontinued ruxolitinib was 36% among those with VAF increase compared to 9% in those where VAF remained stable or decreased (HR 6.1, 95% CI 1.2–30.5; P = .01; Fig. 3, panel D). Clonal progression was also associated with a higher rate of treatment discontinuation (38% vs. 13% for those without clonal progression; P = .05), accounting for an HR of 3.9 (95%CI, 1.1–17.3; P = .01) (Fig. 3 panel E).

We did not find any impact of modifications of VAF of JAK2V617F and other non-driver mutations on survival whilst acquisition of clonal progression at any study time point was associated with shorter overall survival; the median OS was 3.9 years (range, 3.1–4.6) compared to 7.7 years (7.5–8.0) for patients without clonal progression (HR = 3.6, 95%CI 1.4–9.7; P = .006; Fig. 3 panel F). As many as 87.5% of patients with clonal progression documented at any study time point died compared to 34% of those without clonal progression (P = .006).

Discussion

Results of current study confirm and extend previous reports on the impact of driver39,40 and non-driver24,26,27 baseline mutations, and of mutations acquired while on treatment (clonal progression)16, on response to treatment and response duration in patients with myelofibrosis receiving ruxolitinib. For the first time, our study included a control group of matched patients treated with hydroxyurea, that highlighted that MF is hallmarked by highly dynamic mutation landscape that is largely treatment-independent, since modifications of mutation profile during follow-up were substantially similar in patients receiving ruxolitinib or hydroxyurea. These findings, while indicating that clonal progression is not facilitated by ruxolitinib itself but is intrinsically associated to the disease, may have practical relevance as concerns safety issues of ruxolitinib, particularly in the light of recent demonstration of aggressive B-cell lymphomas developing in ruxo-treated patients, that were shown to stem from B-cell clones pre-existing in the bone marrow41. We acknowledge that one limitation of the study is the limited number of patients in the hydroxyurea group, that might warrant confirmation in larger series. Of note, progression to PPV-MF and to acute leukemia in PV and MF patients receiving ruxolitinib was not increased compared to controls3,4,14. However, acquisition of new mutations while on ruxolitinib has relevant clinical correlates, since it was associated with higher rate of discontinuation due to resistance to treatment and death.

Ruxolitinib has limited effects on JAK2V617F VAF in both MF10,15 and PV42, although some patients may present sustained decrease, irrespective of initial level10; complete molecular remissions are exceptional43. Short-term SVR occurs independent of changes in JAK2V617F VAF15; however, we report the novel observation that patients with JAK2V617F VAF reductions ≥ 20% from baseline have significantly greater likelihood to maintain sustained SVR. On the other hand, unlike previous report25, we observed no impact of baseline JAK2V617F VAF on SVR. An additional finding, that deserves validation in larger series, was that clonal progression virtually segregated with patients harboring JAK2V617F mutation, and was not observed in CALR mutated patients. This may have to do with the increased genomic instability that characterizes cells expressing mutated JAK244, showing enhanced frequency of spontaneous homologous recombination events, DNA double strand breaks45, high levels of NHE-146 and deamidate Bcl-xL47, that are possibly mediated by increased reactive oxygen species (ROS)48,49.

Overall, findings from this study add novel information on the impact of baseline and on-treatment acquired genomic alterations on the clinical response in patients with MF receiving ruxolitinib, further highlighting the complexity of genomic landscape of these patients. The ultimate goal of this kind of studies is to identify a molecular profile at baseline that might guide decision regarding initiation of therapy with ruxolitinib;50 although presence of some molecular assets at baseline argue against a long-term likelihood to maintain SVR (current study and16,24,26,27), the large majority of patients obtain rapid clinical improvements, that are not otherwise achieved with other agents, making use of ruxolitinib a reasonable upfront strategy in symptomatic patients. Conversely, detection of specific molecular assets might be useful in counseling for an earlier shift from ruxolitinib to experimental therapies and/or stem cell transplantation. Probably the most relevant variable impacting on long-term maintenance of SVR to ruxolitinib, as well as on survival in patients who discontinue16, is the development of clonal progression while on treatment; serial assessment of mutation profile would be required to define whether the individual has manifested or not clonal progression, that is practically cumbersome50. All together, these particular observations might advocate for the prospective use of extensive genotyping in patients receiving ruxolitinib; however, we believe that further information are needed before this approach may be recommended in daily practice, also considering that alternative therapeutic options to ruxolitinib, outside clinical trials, in non-transplant eligible patients are very few and largely unsatisfactory17.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by AIRC 5x1000 call “Metastatic disease: the key unmet need in oncology” to MYNERVA project, #21267 (MYeloid NEoplasms Research Venture AIRC). A detailed description of the MYNERVA project is available at http://www.progettoagimm.it. Supported also by AIRC Investigator Grant 2014 #15967 and Progetto Ministero della Salute grant No. GR-2011-02352109 to PG and by Regione Toscana, ITT project 2013, CUP: B16D14001130002.

Conflict of interest

A.M.V. was involved in clinical trials with ruxolitinib, participated to advisory boards and speaker bureau for Novartis, and received institutional research grants from Novartis. All remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Alessandro M. Vannucchi, Paola Guglielmelli.

References

- 1.Verstovsek S, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:799–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison C, et al. JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:787–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verstovsek S, et al. Long-term survival in patients treated with ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis: COMFORT-I and -II pooled analyses. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017;10:156. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0527-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vannucchi AM, et al. A pooled analysis of overall survival in COMFORT-I and COMFORT-II, 2 randomized phase 3 trials of ruxolitinib for the treatment of myelofibrosis. Haematologica. 2015;100:1139–1145. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.119545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison CN, et al. Long-term findings from COMFORT-II, a phase 3 study of ruxolitinib vs best available therapy for myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2017;31:775. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cervantes F, Pereira A. Does ruxolitinib prolong the survival of patients with myelofibrosis? Blood. 2017;129:832–837. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-731604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Passamonti F, Maffioli M. The role of JAK2 inhibitors in MPN seven years after approval. Blood. 2018;131:2426–2435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-01-791491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbui T, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia. 2018;32:1057–1069. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0077-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchetti M, et al. Which patients with myelofibrosis should receive ruxolitinib therapy? ELN-SIE evidence-based recommendations. Leukemia. 2017;31:882–888. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deininger M, et al. The effect of long-term ruxolitinib treatment on JAK2p.V617F allele burden in patients with myelofibrosis. Blood. 2015;126:1551–1554. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-635235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kvasnicka HM, et al. Long-term effects of ruxolitinib versus best available therapy on bone marrow fibrosis in patients with myelofibrosis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018;11:42. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0585-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verstovsek S, et al. Three-year efficacy, overall survival, and safety of ruxolitinib therapy in patients with myelofibrosis from the COMFORT-I study. Haematologica. 2015;100:479–488. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.115840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cervantes F, et al. Three-year efficacy, safety, and survival findings from COMFORT-II, a phase 3 study comparing ruxolitinib with best available therapy for myelofibrosis. Blood. 2013;122:4047–4053. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-485888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verstovsek S, et al. Long-term treatment with ruxolitinib for patients with myelofibrosis: 5-year update from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 COMFORT-I trial. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017;10:55. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0417-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison CN, et al. Long-term findings from COMFORT-II, a phase 3 study of ruxolitinib vs best available therapy for myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2016;30:1701–1707. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newberry KJ, et al. Clonal evolution and outcomes in myelofibrosis after ruxolitinib discontinuation. Blood. 2017;130:1125–1131. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-783225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pardanani A, Tefferi A. How I treat myelofibrosis after failure of JAK inhibitors. Blood. 2018;132:492–500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-02-785923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer SC. Mechanisms of Resistance to JAK2 Inhibitors in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North. Am. 2017;31:627–642. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koppikar P, et al. Heterodimeric JAK-STAT activation as a mechanism of persistence to JAK2 inhibitor therapy. Nature. 2012;489:155–159. doi: 10.1038/nature11303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalota A, Jeschke GR, Carroll M, Hexner EO. Intrinsic Resistance to JAK2 Inhibition in Myelofibrosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:1729–1739. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer Sara C, et al. CHZ868, a Type II JAK2 Inhibitor, Reverses Type I JAK Inhibitor Persistence and Demonstrates Efficacy in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deshpande A, et al. Kinase domain mutations confer resistance to novel inhibitors targeting JAK2V617F in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2012;26:708–715. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weigert O, et al. Genetic resistance to JAK2 enzymatic inhibitors is overcome by HSP90 inhibition. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:259–273. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guglielmelli P, et al. Impact of mutational status on outcomes in myelofibrosis patients treated with ruxolitinib in the COMFORT-II Study. Blood. 2014;123:2157–2160. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-536557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barosi G, et al. JAK2(V617F) allele burden 50% is associated with response to ruxolitinib in persons with MPN-associated myelofibrosis and splenomegaly requiring therapy. Leukemia. 2016;30:1772–1775. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel KP, et al. Correlation of mutation profile and response in patients with myelofibrosis treated with ruxolitinib. Blood. 2015;126:790–797. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-633404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiegel JY, et al. Impact of genomic alterations on outcomes in myelofibrosis patients undergoing JAK1/2 inhibitor therapy. Blood Adv. 2017;1:1729–1738. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017009530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbui T, Thiele J, Vannucchi AM, Tefferi A. Rationale for revision and proposed changes of the WHO diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia and primary myelofibrosis. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e337. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swerdlow S. H., et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. (IARC, Lyon, 2017).

- 30.Barosi G, et al. Proposed criteria for the diagnosis of post-polycythemia vera and post-essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis: a consensus statement from the international working group for myelofibrosis research and treatment. Leukemia. 2008;22:437–438. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tefferi A, et al. Revised response criteria for myelofibrosis: International Working Group-Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT) and European LeukemiaNet (ELN) consensus report. Blood. 2013;122:1395–1398. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-488098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emanuel RM, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) symptom assessment form total symptom score: prospective international assessment of an abbreviated symptom burden scoring system among patients with MPNs. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:4098–40103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lippert E, et al. The JAK2-V617F mutation is frequently present at diagnosis in patients with essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera. Blood. 2006;108:1865–1867. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-013540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pancrazzi A, et al. A sensitive detection method for MPLW515L or MPLW515K mutation in chronic myeloproliferative disorders with locked nucleic acid-modified probes and real-time polymerase chain reaction. J. Mol. Diagn. 2008;10:435–441. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.080015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pietra D, et al. Deep sequencing reveals double mutations in cis of MPL exon 10 in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. 2011;96:607–611. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.034793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guglielmelli P, et al. Anaemia characterises patients with myelofibrosis harbouring Mpl mutation. Br. J. Haematol. 2007;137:244–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tefferi A, et al. CALR vs JAK2 vs MPL mutated or triple-negative myelofibrosis: clinical, cytogenetic and molecular comparisons. Leukemia. 2014;28:1472–1477. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guglielmelli P, et al. Validation of the differential prognostic impact of type 1/type 1-like versus type 2/type 2-like CALR mutations in myelofibrosis. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e360. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verstovsek S, et al. The clinical benefit of ruxolitinib across patient subgroups: analysis of a placebocontrolled, Phase III study in patients with myelofibrosis. Br. J. Haematol. 2013;161:508–516. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guglielmelli P, et al. Ruxolitinib is an effective treatment for CALR-positive patients with myelofibrosis. Br. J. Haematol. 2015;173:938–940. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porpaczy E, et al. Aggressive B-cell lymphomas in patients with myelofibrosis receiving JAK1/2 inhibitor therapy. Blood. 2018;132:694–706. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-810739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vannucchi AM, et al. Ruxolitinib reduces JAK2p.V617F allele burden in patients with polycythemia vera enrolled in the RESPONSE study. Ann. Hematol. 2017;96:1113–1120. doi: 10.1007/s00277-017-2994-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pieri L, et al. JAK2V617F complete molecular remission in polycythemia vera/essential thrombocythemia patients treated with ruxolitinib. Blood. 2015;125:3352–3353. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-624536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vainchenker W, Kralovics R. Genetic basis and molecular pathophysiology of classical myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2017;129:3146–3158. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-10-695940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plo I, et al. JAK2 stimulates homologous recombination and genetic instability: potential implication in the heterogeneity of myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2008;112:1402–1412. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dawson MA, et al. JAK2 phosphorylates histone H3Y41 and excludes HP1alpha from chromatin. Nature. 2009;461:819–822. doi: 10.1038/nature08448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao J, Sun BK, Erwin JA, Song JJ, Lee JT. Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X chromosome. Science. 2008;322:750–756. doi: 10.1126/science.1163045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahn JS, et al. JAK2V617F mediates resistance to DNA damage-induced apoptosis by modulating FOXO3A localization and Bcl-xL deamidation. Oncogene. 2016;35:22353–2246. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marty C, et al. A role for reactive oxygen species in JAK2 V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm progression. Leukemia. 2013;27:2187–2195. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vannucchi AM, Guglielmelli P. Traffic lights for ruxolitinib. Blood. 2017;130:1075–1076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-795880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]