Abstract

Objective

To examine audience’s responses to differently framed and formatted persuasive messages in the context of developing depression help-seeking messages.

Design

Cross-sectional followed by 2-month follow-up study.

Setting and participants

A web-based survey was conducted in July 2017 among Japanese adults aged 35–45 years. There were 1957 eligible respondents without psychiatric history. Of these, 1805 people (92.2%) completed the 2-month follow-up questionnaire.

Main outcome measures

Six depression help-seeking messages were prepared with three frames (neutral, loss and gain framed)×2 formats (formatted and unformatted). Participants were asked to rate one of the messages in terms of comprehensibility, persuasiveness, emotional responses, design quality and intended future use. Help-seeking intention for depression was measured using vignette methodology before and after exposure to the messages. Subsequent 2-month help-seeking action for their own mental health (medical service use) was monitored by the follow-up survey.

Results

The loss-framed messages more strongly induced negative emotions (surprise, fear, sadness and anxiety), while the gain-framed messages more strongly induced a positive emotion (happiness). The message formatting applied the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention Clear Communication Index, enhanced the emotional responses and increased the likelihood that the message will be read. The loss-framed formatted message alone had a significantly greater OR of having help-seeking intention for depression compared with the neutral-framed unformatted message as a reference group. All messages had little impact on maintaining help-seeking intention or increasing help-seeking action.

Conclusion

Message framing and formatting may influence emotional responses to the depression help-seeking message, willingness to read the message and intention to seek help for depression. It would be recommendable to apply loss framing and formatting to depression help-seeking messages, to say the least, but further studies are needed to find a way to sustain the effect of messaging for a long time.

Keywords: depression, help-seeking, persuasive message, questionnaire survey

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study represents the first attempt to compare audience’s responses to six depression help-seeking messages with three frames (neutral, loss and gain framed)×2 formats (formatted and unformatted).

The 2-month follow-up survey was conducted to monitor changes in help-seeking intention and action after exposure to the messages.

This study relied on self-reported information. It is almost impossible to eliminate the information bias completely.

The study participants were limited to 35–45 years old selected from a nationwide panel of a research company. It is uncertain whether the messages will work equally well in other age groups or in other settings.

Introduction

Mental disorders are the leading cause of disability worldwide, accounting for 21% of all non-fatal burden.1 Failure and delay in initial treatment contact for mental disorders have been recognised as an important public health problem.2 3 A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that negative attitudes towards mental illness and help seeking are associated with less active help seeking in the general population.4 There is a possibility that interventions for improving people’s attitudes and intentions towards help seeking could facilitate access to mental healthcare, in addition to those targeting people’s behaviours itself.

A number of public health programmes have been launched to eliminate negative attitudes towards mental illness and help seeking to facilitate access to mental healthcare.5 Communication is one of the components necessary for effective public health programme implementation.6 With better information, individuals and communities can make better decisions about their own health. Effective communication produce beneficial changes in people’s behaviours towards health issues.7 8 A systematic review revealed that communicating persuasive messages is effective in improving attitudes towards help seeking for depression.9 Meanwhile, previous studies have suggested that depression help-seeking messages have the potential to backfire; exposure to the messages may result in increased self-stigma and increased reluctance to help seeking (ie, boomerang effect).10 11 Further evidence is needed to identify strategies for successful public health messaging with the aim of promoting access to mental healthcare.

Health communication research has revealed that the effect of persuasive messages can depend on message characteristics. Well known is the framing effect, that is, health messages framed to highlight either the benefits of performing a behaviour (ie, gain framed) or the consequences of not performing a behaviour (ie, loss framed) will lead to different decisions and different health behaviours.12 A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that gain-framed messages are more likely than loss-framed messages to promote prevention behaviours, particularly for skin cancer prevention, smoking cessation and physical activity.13 Meanwhile, the Cochrane Review Group reported that loss-framed messages led to more positive perception of effectiveness than gain-framed messages for screening messages and tended to be more persuasive for treatment messages.14 These results do not unequivocally support the framing effect of health message. There seems to be some contexts in which loss-framed messages are equally or more effective than gain-framed messages. It is uncertain which message frame will more satisfactorily motivate people to seek mental healthcare, loss frame or gain frame.

Reading a message is the first step of the persuasion process. If recipients find difficulty in reading and understanding the given message, it is unlikely to have any persuasive impact. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) proposed a set of evidence-based criteria to plan and assess public health communication materials for diverse audiences, namely the Clear Communication Index.15 On the basis of existing research-based evidence, the index represents the most important items that enhance clarity and aid understanding of public health messages and materials. The six core items applicable to all materials are: (1) include one main message statement, (2) put the main message first, (3) use visual cues to emphasise the main message, (4) include a visual that conveys the main message, (5) include one call to action and 6) use active voice. Previous studies have demonstrated that the materials revised using the Index are rated more favourably than the originals by possible audience members. The application of the index makes it more likely that audience can correctly identify the intended main message and understand the words in the materials.16 17 However, to our knowledge, there have been no attempts to confirm whether health messages designed to conform to the index items function better as a stimulus to change people’s behaviours towards health issues. Moreover, little is known about the interaction between message frame and format. If message format significantly influences the comprehensibility of health message, it is likely to modify the framing effect of health message to some extent.

The objective of this study was to examine whether message framing and formatting are related to persuasive message effectiveness in the context of developing depression help-seeking messages. Although the mechanism of persuasive message effectiveness has not been clearly elucidated, a number of factors can serve to mediate or moderate the effect of persuasive messages. Emotional responses to messages influence perceptions of effectiveness of messages.18 19 Perceived message effectiveness is strongly correlated with and may be causally related to actual message effectiveness.19 20 Intention is the best determinant of behaviour in a wide range of health domains,21 and it has been commonly used as an outcome measure in health communication research.13 We previously found that reading comprehension of health information was significantly associated with recognition of health risk and intention to perform health behaviours.22 On the basis of these findings, the present study compared audience’s responses to six depression help-seeking messages with three frames (neutral, loss and gain framed)×2 formats (formatted and unformatted) in terms of comprehensibility, persuasiveness, emotion, intention and action.

Methods

We launched a research project to develop effective health communication interventions for encouraging help seeking in people at risk of suicide. As the first step in the research project, we developed rating scales for measuring audience’s perceptions of effectiveness of health messages in Japanese people.23 At the second step, we intended to develop effective public health messages that increase people’s help-seeking intentions for depression. We created different kinds of depression help-seeking messages on the basis of our previous findings24 and conducted a web-based survey to rate them by possible audience members. Data from the survey were analysed to achieve the two intended objectives. One was to examine whether message framing and formatting are related to the effectiveness of depression help-seeking messages, as reported in this paper. Another objective was to determine whether the effectiveness of depression help-seeking messages are influenced by audience’s depressive status, as reported elsewhere.25

The study protocol was approved and has been conducted in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects by the Japanese government.

Patient and public involvement

There were no patients involved in the design of the study or the recruitment to and conduct of the study.

Messages

In order to examine the effects of message framing and formatting, six depression help-seeking messages were prepared with three frames (neutral, loss and gain framed)×2 formats (formatted and unformatted). The aim of messaging was to increase people’s help-seeking intentions for depression. The target audience were either depressed or non-depressed people. The messages were designed as print advertisements to be inserted in the form of web-based surveys.

The formatted versions of depression help-seeking messages were shown in online supplementary appendix A. Each message consisted of three parts. The first part was the main message statement. The second part provided information on early signs of depression: depression can be recognised early by mental symptoms such as depressed mood, loss of interest, etc, and physical symptoms such as disturbed sleep, increased fatigue, etc. The last part was the call to action: if you suspect your depression, consult your familiar primary care doctor.

bmjopen-2017-020823supp001.pdf (189KB, pdf)

The three main message statements were selected from the text message list developed by Bell and colleagues26 so as to be matched against the beliefs related to the top three reasons for having no help-seeking intention for depression, respectively24: (1) depression can happen to anyone, (2) depression needs treatment and (3) depression improves with treatment. The first one was neutral framed with additional information on incidence of depression: about 1 out of 15 people experience depression during their lifetime. The second one was loss framed (thereat appeal) with additional information on prognosis of untreated patients: about 80% of untreated patients will not recover. The third one was gain framed (benefit appeal) with additional information on prognosis of treated patients: about 80% of treated patients will recover.

For each of the three differently framed messages, the formatted and unformatted versions were prepared. The formatted (visual) messages were visually designed in accordance with the CDC Clear Communication Index User Guide.15 The unformatted (plain) messages were in plain text without any colours or visuals.

Participants

A web-based survey was conducted in July 2017 among Japanese adults aged 35–45 years. The Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions revealed that people who were feeling stressed or distressed were most frequently observed in the 40–49 age group (58.7% in men and 48.6% in women).27 In addition, the World Mental Health Japan Survey revealed that the 12-month prevalence of mental disorders was significantly higher in the younger age groups.28 Therefore, people aged 35–45 years seemed to be a suitable target for persuasive messages encouraging help-seeking for depression.

Participants in the survey were recruited from an online research panel of a leading research company in Japan (Cross Marketing, Tokyo, Japan). Medical professionals were excluded through a prescreening process. Applicants for participation in the survey were accepted in the order of receipt until the number of participants reached the quotas for gender, area and K6 score (1–4 and ≤5 points). The Japanese version of the six-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) has been established as a screener for depression in Japan.29 A validation study revealed that a K6 score ≥5 is a reasonable cut-off to distinguish between depressed and non-depressed people.30 A total of 2520 responses were obtained over 2 days of recruitment.

A follow-up survey was conducted in September 2017 to monitor subsequent changes in help-seeking intention and action. Of the 2520 participants in the initial survey, 2315 people (91.9%) completed the follow-up questionnaire.

All participants voluntarily agreed to participate in the survey after reading a description of the purpose and procedure of the survey. Consent to participate was implied by the completion and submission of the survey.

Measures

Participants in the initial survey were randomly assigned to one of the six depression help-seeking messages. After they read the message for at least 15 s, they were asked to rate it in terms of comprehensibility, persuasiveness, emotional responses, design quality and intended future use. Help-seeking intention for depression was measured using vignette methodology before and after exposure to the messages. Moreover, participants in the follow-up survey were asked about help-seeking intention for depression and help-seeking action for their own mental health (medical service use) during the 2-month follow-up period.

The web questionnaire forms presented the questions one by one through the operation of a ‘Next’ button. Respondents answered one question per page and could not go back to the previous page.

Comprehensibility

Using the perceived effectiveness rating scales,23 the five items asked how easy or hard the information is to: (1) read, (2) understand, (3) remember, (4) locate important information and (5) keep for future reference. All item scores (range 1–5 points) were averaged to produce the comprehensibility score.

Persuasiveness

Using the perceived effectiveness rating scales,23 the seven items asked to what extent they agree or disagree that the information is: (1) believable, (2) convincing, (3) important to me, (4) help me feel confident about how best to do, (5) would help my family and friends, (6) put thoughts in my mind about wanting to do and (7) agreeable. All item scores (range 1–5 points) were averaged to produce the persuasiveness score.

Emotional responses

Participants were asked ‘when you read the message, to what extent you feel: (1) surprise, (2) anger, (3) fear, (4) sadness, (5) guilt, (6) anxiety and (7) happiness?’.18 19 Response options were from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Design quality

Six items for design quality were derived from the Consumer Information Rating Form developed by Krass and colleagues.31 Participants were asked to rate the message on a five-point scale in terms of (1) organisation, (2) attractiveness, (3) size, (4) tone, (5) helpfulness and (6) spacing. Higher scores indicate higher quality.

Intended future use

Three items for intended future use were derived from the Consumer Information Rating Form developed by Krass and colleagues.31 Participants were asked ‘If you saw the information in a newspaper or magazine, how likely would you [use, read, and keep] it?’. Response options were from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely).

Help-seeking intention

Help-seeking intention for depression was measured using vignette methodology. Participants were presented with a vignette describing a man (or woman) with depression and were then asked ‘If you had health problems right now like Mr. A (or Ms. A), would you see a doctor?’.23–25 Participants answered the question on a four-point scale (certainly yes/probably yes/probably not/certainly not). Those who gave affirmative answers (certainly yes and probably yes) were counted as having a positive help-seeking intention.

Help-seeking intention for depression was measured at three time points: (1) before exposure to the messages in the initial survey, (2) after exposure to the messages in the initial survey and (3) at the follow-up survey. Those who had a positive help-seeking intention at the second point but did not at the first point were counted as developing help-seeking intentions after exposure to the message. Those who had a positive help-seeking intention both at the second and third points were counted as maintaining help-seeking intention.

Help-seeking action

Help-seeking action for their own mental health was measured in the follow-up survey by asking participants whether they had seen a doctor for their mental health problem in the previous 2 months.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Main and interaction effects of frame and format were assessed using two-way analysis of variance. The proportions of people who reported a positive help-seeking intention for depression before and after exposure to the messages were compared using McNemar test. Multiple logistic regression analysis was further conducted to compare the likelihood of having help-seeking intention for depression across the differently framed and formatted messages. OR with 95% CI for help-seeking intention for depression were calculated with adjustment for gender, depressive status and help-seeking intention before exposure the messages. Significant levels were set at p<0.05.

A statistical power analysis was carried out using Cohen’s tables,32 because there was no existing research to indicate a likely effect size. To detect a small-sized difference between independent means (d=0.20), 393 samples in each group give an alpha of 0.05 with a power of 0.80; the necessary sample size was 310 at an alpha of 0.10 and 586 at an alpha of 0.01 with the same power. The number of participants in each group ranged between 267 and 382, which were adequate to detect small effects at an alpha of 0.05.

Results

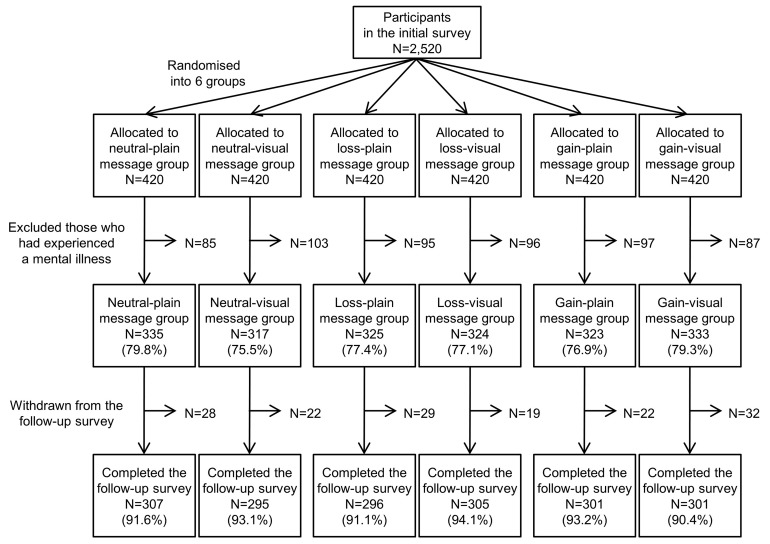

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the study. In the initial survey, 2520 participants were randomly assigned to one of the six message groups. Excluding those who had an experience of receiving treatment for their mental illness, the remaining 1957 participants were included in the study. Of these, 1805 people (92.2%) who completed the follow-up questionnaire were included in the analysis of the follow-up data.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants. Of the 1957 participants, 45.6% had a university degree, 56.3% were married and 60.1% had a full-time job. As a result of the random assignment of participants to six message groups, no significant differences between the message groups were observed in sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| N | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 980 | 50.1% |

| Female | 977 | 49.9% |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 40.9 | (3.0) |

| Education | ||

| Compulsory education/high school | 540 | 27.6% |

| Junior college/vocational school | 524 | 26.8% |

| University or higher | 893 | 45.6% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1101 | 56.3% |

| Unmarried | 767 | 39.2% |

| Divorced/widowed | 89 | 4.5% |

| Occupation | ||

| Full-time job | 1176 | 60.1% |

| Temporary or part-time job | 329 | 16.8% |

| No occupation | 452 | 23.1% |

| Household income* | ||

| <2.0 million yen | 230 | 11.8% |

| 2.0–3.9 million | 394 | 20.1% |

| 4.0–5.9 million | 552 | 28.2% |

| 6.0–7.9 million | 400 | 20.4% |

| 8.0–9.9 million | 205 | 10.5% |

| 10.0+ million | 161 | 8.2% |

| Missing | 15 | 0.8% |

*1 million yen was about US$10 000 at the time of the survey.

Table 2 shows the assessment of the depression help-seeking messages. The comprehensibility and persuasiveness scores showed no significant differences between the frames or between the formats. For the emotional responses, significant main effects of frame were observed in five out of seven items (surprise, fear, sadness, anxiety and happiness). There was a significant effect of format on ‘surprise’ and significant frame×format interaction effects on ‘anxiety’ and ‘happiness’. Compared with the neutral-framed, the loss-framed and gain-framed messages showed significant enhancements of emotional responses to the formatted messages. For the design quality, significant main effects of format were observed in four out of six items (attractiveness, size, helpfulness and spacing). There were significant main effects of frame on three items (attractiveness, tone and helpfulness) but no significant frame×format interaction. For the intended future use, a significant main effect of format was observed in one out of three items (read). There were no significant main effects of frame and no significant frame×format interaction.

Table 2.

Assessment of the depression help-seeking messages

| Message | P values Frame (A) |

Format (B) | A× B | |||||||

| Neutral-plain | Neutral-visual | Loss-plain | Loss-visual | Gain-plain | Gain-visual | |||||

| Comprehensibility | ||||||||||

| Mean | 3.74 | 3.81 | 3.79 | 3.80 | 3.82 | 3.82 | 0.554 | 0.472 | 0.757 | |

| SD | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.78 | ||||

| Persuasiveness | ||||||||||

| Mean | 3.15 | 3.13 | 3.20 | 3.18 | 3.10 | 3.17 | 0.168 | 0.732 | 0.352 | |

| SD | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.64 | ||||

| Emotional responses | ||||||||||

| (1) Surprise | Mean | 2.47 | 2.57 | 2.60 | 2.81 | 2.49 | 2.63 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.636 |

| SD | 1.03 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.10 | 1.02 | ||||

| (2) Anger | Mean | 1.91 | 1.91 | 1.94 | 2.01 | 1.90 | 1.99 | 0.411 | 0.202 | 0.596 |

| SD | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.93 | ||||

| (3) Fear | Mean | 2.51 | 2.43 | 2.55 | 2.64 | 2.22 | 2.41 | <0.001 | 0.163 | 0.061 |

| SD | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.01 | 0.98 | ||||

| (4) Sadness | Mean | 2.44 | 2.43 | 2.53 | 2.61 | 2.24 | 2.38 | <0.001 | 0.124 | 0.413 |

| SD | 1.03 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.95 | ||||

| (5) Guilt | Mean | 2.09 | 2.07 | 2.08 | 2.18 | 2.02 | 2.09 | 0.326 | 0.247 | 0.440 |

| SD | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.86 | ||||

| (6) Anxiety | Mean | 2.63 | 2.50 | 2.59 | 2.74 | 2.34 | 2.45 | <0.001 | 0.370 | 0.035 |

| SD | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 1.03 | ||||

| (7) Happy | Mean | 1.93 | 1.83 | 1.99 | 1.98 | 2.17 | 2.35 | <0.001 | 0.657 | 0.024 |

| SD | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.95 | ||||

| Design quality | ||||||||||

| (1) Organisation | Mean | 3.67 | 3.65 | 3.72 | 3.80 | 3.64 | 3.71 | 0.113 | 0.258 | 0.557 |

| SD | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.87 | ||||

| (2) Attractiveness | Mean | 3.10 | 3.22 | 3.18 | 3.37 | 3.08 | 3.26 | 0.029 | <0.001 | 0.749 |

| SD | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.90 | ||||

| (3) Size | Mean | 3.38 | 3.38 | 3.37 | 3.52 | 3.32 | 3.41 | 0.177 | 0.037 | 0.296 |

| SD | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.86 | ||||

| (4) Tone | Mean | 3.16 | 3.11 | 3.20 | 3.13 | 3.22 | 3.33 | 0.004 | 0.966 | 0.084 |

| SD | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.83 | ||||

| (5) Helpfulness | Mean | 3.38 | 3.36 | 3.39 | 3.57 | 3.37 | 3.48 | 0.048 | 0.019 | 0.109 |

| SD | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.87 | ||||

| (6) Spacing | Mean | 3.35 | 3.50 | 3.26 | 3.56 | 3.24 | 3.52 | 0.633 | <0.001 | 0.220 |

| SD | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.80 | ||||

| Intended future use | ||||||||||

| (1) Read | Mean | 3.17 | 3.23 | 3.28 | 3.28 | 3.12 | 3.36 | 0.286 | 0.016 | 0.052 |

| SD | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.87 | ||||

| (2) Use | Mean | 2.77 | 2.71 | 2.87 | 2.83 | 2.72 | 2.86 | 0.063 | 0.666 | 0.065 |

| SD | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.79 | ||||

| (3) Keep | Mean | 2.36 | 2.34 | 2.38 | 2.48 | 2.34 | 2.46 | 0.332 | 0.142 | 0.332 |

| SD | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.90 | ||||

Table 3 shows the changes in help-seeking intention for depression before and after exposure to the messages. All messages except the neutral-plain message produced significant increase in help-seeking intention. Similar results were obtained when only those who were depressed (K6 score ≥5) were analysed.

Table 3.

Changes in help-seeking intention for depression

| Message | All | P values | Depressed (K6 score≥5) | P values | ||||||

| N | Positive intention | N | Positive intention | |||||||

| Before | After | Change | Before | After | Change | |||||

| Neutral-plain | 335 | 115 | 128 | 0.128 | 142 | 40 | 48 | 0.131 | ||

| 34.3% | 38.2% | +11.3% | 28.2% | 33.8% | +20.0% | |||||

| Neutral-visual | 317 | 116 | 139 | 0.003 | 128 | 34 | 52 | <0.001 | ||

| 36.6% | 43.8% | +19.8% | 26.6% | 40.6% | +52.9% | |||||

| Loss-plain | 325 | 126 | 146 | 0.017 | 130 | 41 | 51 | 0.033 | ||

| 38.8% | 44.9% | +15.9% | 31.5% | 39.2% | +24.4% | |||||

| Loss-visual | 324 | 117 | 151 | <0.001 | 137 | 40 | 56 | 0.003 | ||

| 36.1% | 46.6% | +29.1% | 29.2% | 40.9% | +40.0% | |||||

| Gain-plain | 323 | 117 | 144 | 0.001 | 137 | 36 | 48 | 0.011 | ||

| 36.2% | 44.6% | +23.1% | 26.3% | 35.0% | +33.3% | |||||

| Gain-visual | 333 | 135 | 158 | 0.003 | 150 | 58 | 72 | 0.004 | ||

| 40.5% | 47.4% | +17.0% | 38.7% | 48.0% | +24.1% | |||||

Help-seeking intention for depression was assessed before and after exposure to the messages. McNemar test was used to assess changes in help-seeking intention.

All items were scored on a 1–5-point scale. Two-way analysis of variance was used to assess main and interaction effects of frame and format.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was further conducted to compare the likelihood of having help-seeking intention for depression across the differently framed and formatted messages. The loss-visual message alone had a significantly greater OR of having help-seeking intention for depression compared with the neutral-plain message as a reference group: the adjusted OR (95% CI) of the neutral-visual, loss-plain, loss-visual, gain-plain and gain-visual messages were 1.31 (0.89 to 1.92), 1.29 (0.88 to 1.89), 1.57 (1.07 to 2.29), 1.39 (0.95 to 2.04) and 1.41 (0.97 to 2.06), respectively.

Of the 1805 participants in the follow-up survey, 1141 people had not possessed help-seeking intention before exposure to the messages, and 249 people (21.8%) developed their help-seeking intentions after exposure to the messages. Of these, 143 people (57.4%) maintained their help-seeking intentions up to the follow-up survey. The proportion of participants who maintain their help-seeking intentions was not significantly different across the given messages: the percentages for the neutral-visual, loss-plain, loss-visual, gain-plain and gain-visual messages were 65.7% (23/35), 57.9% (22/38), 48.0% (25/50), 23/44 (52.3%) and 67.5% (27/40), respectively (p=0.423).

Table 4 shows the help-seeking action during the follow-up period. There were 66 people (3.7%) who had seen a doctor for their mental health problem during the follow-up period. The proportion of participants with help-seeking action was not significantly different across the given messages. Similar results were obtained when only those who were depressed (K6 score ≥5) were analysed.

Table 4.

Help-seeking action during the follow-up period

| Message | All | Depressed (K6 score≥5) | ||

| N | Action | N | Action | |

| Neutral-plain | 307 | 12 | 132 | 8 |

| 3.9% | 6.1% | |||

| Neutral-visual | 295 | 12 | 121 | 5 |

| 4.1% | 4.1% | |||

| Loss-plain | 296 | 8 | 120 | 4 |

| 2.7% | 3.3% | |||

| Loss-visual | 305 | 9 | 128 | 6 |

| 3.0% | 4.7% | |||

| Gain-plain | 301 | 14 | 127 | 11 |

| 4.7% | 8.7% | |||

| Gain-visual | 301 | 11 | 141 | 8 |

| 3.7% | 5.7% | |||

| P=0.815 | P=0.516 | |||

Help-seeking action for their own mental health in the previous 2 months was measured in the follow-up survey.

Discussion

This study examined audience’s responses to differently framed and formatted persuasive messages in the context of developing depression help-seeking messages. Although depression help-seeking messages have the potential to backfire,10 11 such boomerang effect was not evident in this study. All messages except the neutral-plain message produced significant increase in help-seeking intention after exposure to the messages. This result supports the effectiveness of communicating persuasive messages for increasing people’s help-seeking intentions for depression. Moreover, multiple logistic regression analysis indicated that the loss-visual message worked better than the other messages. Despite the potential limitations of this study, it would be recommendable to apply loss framing and formatting to depression help-seeking messages.

The three message frames elicited different patterns of emotional responses. The loss-framed messages more strongly induced negative emotions (surprise, fear, sadness and anxiety), while the gain-framed messages more strongly induced a positive emotion (happiness). Previous studies have suggested that emotional responses play a significant role in the persuasion process.18 19 There was no significant difference in persuasiveness; however, the loss-framed and gain-framed messages seemed more likely to bring out the recipients’ help-seeking intentions by inducing emotional responses than the neutral-framed messages.

The formatted messages were judged superior to the unformatted messages in design quality. The formatted messages consequently succeeded in increasing the likelihood that the message will be read. These results support the effectiveness of the CDC Clear Communication Index which helps provide easily understandable health messages and materials.16 17 The significant frame×format interaction effects on ‘anxiety’ and ‘happiness’ indicated that the message formatting enhanced the recipients’ emotional responses, both negative and positive. There was no significant difference in persuasiveness; however, the formatted messages seemed more likely to be perceived as attractive and helpful by the audience and more likely to increase the recipients’ willingness to read than the unformatted messages.

As for the percentage changes in help-seeking intention for depression by message group (table 3), it is hard to say that the loss-framed messages were more effective than the gain-framed messages or vice versa. The loss-plain message showed a smaller percentage increase than the gain-plain message (15.9% vs 23.1%). Meanwhile, the loss-visual message showed a greater percentage increase than the gain-visual message (29.1% vs 17.0%). The respective effects of loss framing and formatting on help-seeking intention were not pre-eminent, but multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that the loss-visual message alone had a significantly greater OR of having help-seeking intention for depression compared with the neutral-plain message as a reference group. Previous studies have not provided a conclusive answer as to which message frame will more satisfactorily motivate people to seek mental healthcare, loss frame or gain frame.13 14 A literature review suggested that adding pictures to written text will increase the likelihood that the text will be read; however, the effects of pictures on comprehension, recall and adherence have not yet been established.33 The results of this study are insufficient to conclude, but it is likely that loss framing and formatting act synergistically to increase help-seeking intention for depression. It would be recommendable to apply loss framing and formatting to depression help-seeking messages, to say the least.

Of those who developed their help-seeking intention after exposure to the messages, 43.6% did not maintain their help-seeking intentions up to the 2-month follow-up survey. The depression help-seeking messages succeeded in possessing help-seeking intention for a short time after exposure, but the effect could not be sustained over time. Moreover, those who had taken help-seeking action during the 2-month follow-up period accounted for 3.7% of the total and for 5.5% of those who were depressed (K6 score ≥5). Seeing a message only once may be insufficient to induce help-seeking action. Although a number of interventions have been conducted to promote access to mental healthcare, very little is known about what interventions increase help-seeking action.9 To our knowledge, there is no successful precedent that proved the effect of public health messaging on help-seeking action. Further studies are needed to find out effective strategies for maintaining help-seeking intention and increasing help-seeking action.

This study provides evidence for the effectiveness of depression help-seeking messages in middle-aged Japanese people. On the contrary, it has a number of potential limitations. First, the web-based survey was self-administered, so that the accuracy of responses would depend on participants’ understanding of the questions and their motivation to answer questions accurately. The understandability of the wording of items was checked prior to the survey. The use of the internet and the provision of anonymity would be expected to elicit more truthful responses, by minimising social desirability pressures.34 However, it is almost impossible to eliminate the information bias completely. Second, the study participants were selected from a nationwide panel of a research company. According to the national census,35 the percentage of the Japanese population aged 35–44 years with university degrees were 22.0% in 2010, considerably lower than that of this study (45.6%). The selection bias may have influenced the results to some extent. Third, the study participants were limited to 35–45 years old. It is uncertain whether the messages will work equally well in other age groups. Moreover, because of cultural differences, the findings from this study may not be applicable to non-Japanese populations. Now we are planning to conduct a population-based interventional study to assess the effectiveness of a public health communication programme using the depression help-seeking messages. We will discuss the channels and activities that will be most likely to successfully reach target audience in the future study.

Conclusion

This study compared audience’s responses to six depression help-seeking messages with three frames (neutral, loss and gain framed)×2 formats (formatted and unformatted). The message formatting applied the CDC Clear Communication Index, enhanced the recipients’ emotional responses and increased the likelihood that the message will be read. Multiple logistic regression analysis indicated that the loss-framed formatted message worked better than the other messages. According to these results, message framing and formatting may influence emotional responses to the depression help-seeking message, willingness to read the message and intention to seek help for depression. It would be recommendable to apply loss framing and formatting to depression help-seeking messages, to say the least, but further studies are needed to find a way to sustain the effect of messaging for a long time.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MS was responsible for the design and conduct of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data and the writing of the article. TY and HY contributed to the data interpretation and discussion of the implications of this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16K09147 and the Uehara Memorial Foundation Research Grant.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the Jikei University School of Medicine and has been conducted in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects by the Japanese Government.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:743–800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G, et al. . Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 2007;6:177–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. . Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet 2007;370:841–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schnyder N, Panczak R, Groth N, et al. . Association between mental health-related stigma and active help-seeking: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2017;210:261–8. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.189464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Henderson C, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G, et al. . help seeking, and public health programs. Am J Public Health 2013;103:777–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frieden TR. Six components necessary for effective public health program implementation. Am J Public Health 2014;104:17–22. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Cancer Institute. Making health communication programs work (Pink Book). https://www.cancer.gov/publications/health-communication (accessed 15 Jul 2018).

- 8. Abroms LC, Maibach EW. The effectiveness of mass communication to change public behavior. Annu Rev Public Health 2008;29:219–34. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, et al. . A systematic review of help-seeking interventions for depression, anxiety and general psychological distress. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:81 10.1186/1471-244X-12-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lienemann BA, Siegel JT, Crano WD. Persuading people with depression to seek help: respect the boomerang. Health Commun 2013;28:718–28. 10.1080/10410236.2012.712091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Niederkrotenthaler T, Reidenberg DJ, Till B, et al. . Increasing help-seeking and referrals for individuals at risk for suicide by decreasing stigma: the role of mass media. Am J Prev Med 2014;47(3):S235–S243. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rothman AJ, Salovey P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: the role of message framing. Psychol Bull 1997;121:3–19. 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gallagher KM, Updegraff JA. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med 2012;43:101–16. 10.1007/s12160-011-9308-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Akl EA, Oxman AD, Herrin J, et al. . Framing of health information messages. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;12:CD006777 10.1002/14651858.CD006777.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Clear Communication Index. http://www.cdc.gov/ccindex (accessed 2017.10.1).

- 16. Baur C, Prue C. The CDC Clear Communication Index is a new evidence-based tool to prepare and review health information. Health Promot Pract 2014;15:629–37. 10.1177/1524839914538969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Porter KJ, Alexander R, Perzynski KM, et al. . Using the clear communication index to improve materials for a behavioral intervention. Health Commun 2018;8:1–7. 10.1080/10410236.2018.1436383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dillard JP, Peck E. Affect and persuasion: Emotional responses to public service announcements. Communication Research 2000;27:461–95. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dillard JP, Shen L, Vail RG. Does perceived message effectiveness cause persuasion or vice versa? 17 Consistent Answers. Hum Commun Res 2007;33:467–88. 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2007.00308.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dillard JP, Weber KM, Vail RG. The relationship between the perceived and actual effectiveness of persuasive messages: A meta-analysis with implications for formative campaign research. J Commun 2007;57:613–31. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00360.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bylund CL, Peterson EB, Cameron KA. A practitioner’s guide to interpersonal communication theory: an overview and exploration of selected theories. Patient Educ Couns 2012;87:261–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Suka M, Odajima T, Okamoto M, et al. . Reading comprehension of health checkup reports and health literacy in Japanese people. Environ Health Prev Med 2014;19:295–306. 10.1007/s12199-014-0392-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suka M, Yamauchi T, Yanagisawa H. Perceived effectiveness rating scales applied to insomnia help-seeking messages for middle-aged Japanese people: a validity and reliability study. Environ Health Prev Med 2017;22:69 10.1186/s12199-017-0676-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Suka M, Yamauchi T, Sugimori H. Help-seeking intentions for early signs of mental illness and their associated factors: comparison across four kinds of health problems. BMC Public Health 2016;16:301 10.1186/s12889-016-2998-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suka M, Yamauchi T, Yanagisawa H. Development of persuasive messages encouraging help-seeking for depression among people with various depressive status. BMC Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bell RA, Paterniti DA, Azari R, et al. . Encouraging patients with depressive symptoms to seek care: a mixed methods approach to message development. Patient Educ Couns 2010;78:198–205. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, 2016. Comprehensive survey of living conditions 2016 (in Japanese) http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa16/ (accessed 22 Apr 2018).

- 28. Ishikawa H, Kawakami N, Kessler RC. World Mental Health Japan Survey Collaborators. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence, severity and unmet need for treatment of common mental disorders in japan: Results from the final dataset of world mental health Japan Survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2016;25:217–29. 10.1017/S2045796015000566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kawakami N, Kondo K, Yanagida K, et al. . Mental health research on the preventive measure against suicide in adulthood Ueda S, Report of the research grant for the implementation of preventive measure based on the current status of suicide from the ministry of health, labour and welfare. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2005:147–57. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sakurai K, Nishi A, Kondo K, et al. . Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011;65:434–41. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Koo MM, Krass I, Aslani P. Evaluation of written medicine information: validation of the consumer information rating form. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:951–6. 10.1345/aph.1K083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–9. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Houts PS, Doak CC, Doak LG, et al. . The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:61173–90. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Joinson A, desirability S. anonymity, and Internet-based questionnaires. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 1999;31:433–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. National Census 2017. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/GL02100104.do?tocd=00200521 (accessed 1 oct 2017). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020823supp001.pdf (189KB, pdf)