Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate persistence and adherence of oral pharmacotherapy used in the treatment of overactive bladder (OAB) in a real-world setting.

Materials and methods

Systematic literature searches of six electronic publication databases were performed to identify observational studies of patients with OAB treated with antimuscarinics and/or mirabegron. Studies obtaining persistence and adherence data from sources other than electronic prescription claims were excluded. Reference lists of identified studies and relevant systematic reviews were assessed to identify additional relevant studies.

Results

The search identified 3897 studies, of which 30 were included. Overall, persistence ranged from 5% to 47%. In studies reporting data for antimuscarinics and mirabegron (n=3), 1-year persistence was 12%–25% and 32%–38%, respectively. Median time to discontinuation was <5 months for antimuscarinics (except one study (6.5 months)) and 5.6–7.4 months for mirabegron. The proportion of patients adherent at 1 year varied between 15% and 44%. In studies reporting adherence for antimuscarinics and mirabegron, adherence was higher with mirabegron (mean medication possession ratio (MPR): 0.59 vs 0.41–0.53; mean proportion of days covered: 0.66 vs 0.55; and median MPR: 0.65 vs 0.19–0.49). Reported determinants of persistence and adherence included female (sex), older age group, use of extended-release formulation and treatment experience.

Conclusion

Most patients with OAB discontinued oral OAB pharmacotherapy and were non-adherent 1 year after treatment initiation. In general, mirabegron was associated with greater persistence and adherence compared with antimuscarinics. Combined with existing clinical trial evidence, this real-world review merits consideration of mirabegron for first-line pharmacological treatment among patients with OAB.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017059894.

Keywords: overactive bladder, persistence, adherence, antimuscarinics, β3 adrenergic receptor agonists, systematic literature review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic literature review includes data for mirabegron, which was approved in 2013 and not covered in previous systematic reviews examining persistence and adherence to overactive bladder (OAB) medication.

Only observational database studies were included in this study, with the intention to provide a more accurate picture of rates of adherence and persistence to OAB medication, which are generally lower in routine clinical practice compared with randomised clinical trials.

This systematic literature review provides a global picture of adherence and persistence to OAB medication based on the inclusion of data from Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Norway, Spain, the UK and the USA.

Although determinants of persistence and adherence were evaluated in this study, the influence of other factors such as patient expectations, appropriate counselling and patient satisfaction with treatment could not be assessed.

The definitions and calculations of persistence and adherence were not uniform across the literature. These terms were often used interchangeably, limiting the ability to compare across studies.

Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is defined as a condition with characteristic symptoms of urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency incontinence, in the absence of urinary tract infection (UTI) or other obvious pathology.1 OAB affects 11.8%–24.7% of adults in North America and Europe, and the prevalence increases with age.2 In addition to age, risk factors for developing OAB include diabetes, UTIs and obesity.3 4

OAB symptoms are associated with a negative impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and a significant economic burden. Indeed, bothersome OAB symptoms may lead to depression and anxiety, and sleep disturbances, which can adversely affect a patient’s daily, social and professional functioning.5 6 While the cost of pharmaceutical treatment represents only a small fraction of the total therapy cost, the provision of containment products (eg, pads), treatment for clinical depression, nursing home stays and loss of productivity due to work absenteeism are the main cost drivers in OAB.7 8 For example, the total annual cost of OAB was estimated to be US$24.9 billion in the USA in 20079 and €9.7 billion across five European countries (Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the UK) and Canada in 2005.8

Behavioural and lifestyle modifications are routinely the initial treatment strategy for OAB, and pharmacotherapy is recommended only if conservative management is not effective.10 As OAB is a chronic condition, it is important that patients continue with treatment to control symptoms.11 Lack of persistence (time from treatment initiation to discontinuation)12 and adherence (extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of a dosing regimen)12 to medication are considered the leading causes of preventable morbidity in patients with chronic conditions13 14; they are also associated with greater indirect costs.14 Studies have reported that patients compliant and adherent to OAB medication experienced significantly improved urinary symptoms and HRQoL compared with patients who were non-persistent.15 16 Although antimuscarinics are the current mainstay of oral pharmacotherapy, they are often associated with bothersome anticholinergic side effects, such as dry mouth and constipation; tolerability is one of the most common reasons for treatment discontinuation.11 17–20 In a systematic review of antimuscarinic treatment in patients with OAB, rates of discontinuation at 12 weeks ranged from 4% to 31% in clinical trials and 43%–83% in medical claims databases.19

The other class of oral pharmacotherapy approved for the treatment of OAB is β3-adrenergic receptor agonists. Mirabegron is currently the only commercially available agent of this class licensed in countries across Europe, North America and Asia.21–23 Due to mirabegron’s mechanism of action, the incidence of side effects typically reported with antimuscarinic treatment are low with mirabegron and generally similar to placebo,24 which may translate into better treatment persistence.25 26 In addition, results of a recent economic analysis found that increased persistence with mirabegron treatment versus antimuscarinics was associated with reduced healthcare resource use and work hours lost, resulting in lower total costs.27

In general, rates of persistence and adherence with antimuscarinics and mirabegron are typically lower in routine clinical practice compared with interventional clinical trials.11 28 To help identify factors affecting long-term persistence and adherence to OAB pharmacotherapy, a contemporary, comprehensive review of real-world evidence is needed. As mirabegron was a relatively new OAB treatment, it was not included in previous systematic reviews. Therefore, the current analysis aims to systematically review prospective and retrospective observational database studies conducted with antimuscarinics and/or mirabegron to determine the rates and determinants of persistence and adherence.

Methods

This systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted in accordance with guidelines for the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology.29 The protocol for the review was registered a priori with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registered 18 January 2017 with PROSPERO CRD42017059894).

Searches were performed on 27 April 2017 via the following electronic databases: Allied and Complementary Medicine Database; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; MEDLINE; Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects; Health Technology Assessment database; and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database. The search terms were persisten* OR adheren* OR complian* OR discont* OR tolera* OR utili* OR database (Title), AND ‘bladder’ OR ‘overactive bladder’ OR ‘OAB’ OR urin* OR incontinen* (Title), OR oxybutynin OR tolterodine OR fesoterodine OR trospium OR darifenacin OR solifenacin OR propiverine OR imidafenacin OR mirabegron OR flavoxate OR hyoscyamin* OR anticholinerg* OR antimuscarin* (Title).

All search results were exported into EndNote Web (Thomas Reuter, Califonia, USA) bibliography software and duplicates removed electronically and manually. The full electronic search strategy is outlined in the online supplementary information.

bmjopen-2018-021889supp001.pdf (249.1KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: prospective and retrospective observational database studies investigating persistence and adherence to oral medication for the treatment of OAB in adults, conducted in any geographical location and published on any date, within a peer-reviewed source. Exclusion criteria were: abstract unavailable; studies not yet fully completed; randomised controlled trials (RCTs); systematic reviews; narrative literature reviews; conference papers; single case studies/reports; studies investigating OAB medication among only healthy, asymptomatic participants; studies from which oral-only OAB persistence/adherence results cannot be isolated from other results (ie, transdermal patches); and studies containing patients aged <18 years (where the data pertaining to these patients could not be removed from the results) and studies not published in English. Populations with lower urinary tract symptoms due to stress incontinence and benign prostatic hyperplasia were also excluded.

Study selection

Duplicates were removed and title and abstract screenings were performed by two independent researchers (PS and GY). Full-text articles were obtained and studies were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria.30 Any disagreement in study selection was to be resolved through discussion and consultation with another member of the project team (FF) where necessary. During screening, open-label extension studies of RCTs were excluded as the trial designs were unlikely to reflect a real-world setting. Studies using data from hospital records, in addition to large-scale databases, were included provided that persistence and adherence data were determined from prescription claims data rather than extracted from supplemental patient interviews, patient-supplied pill counts or subjective questionnaires. The literature search was supplemented by screening for potential additional relevant studies identified from the reference lists of eligible articles.

Data extraction

Parameters that may affect persistence or adherence were collected, including patient characteristics (age and sex), interventions (initial (index) OAB drug and formulation) and comorbidities. The definitions, outcomes and determinants of treatment persistence and adherence were also collected, where reported. The extracted data were evaluated by one researcher and verified by a second researcher.

Data analysis

A descriptive analysis of extracted results is presented. No meta-analysis was planned due to the expected heterogeneity of reporting methodologies and data across studies.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not directly involved in the conduct of this study.

Results

Brief overview of studies

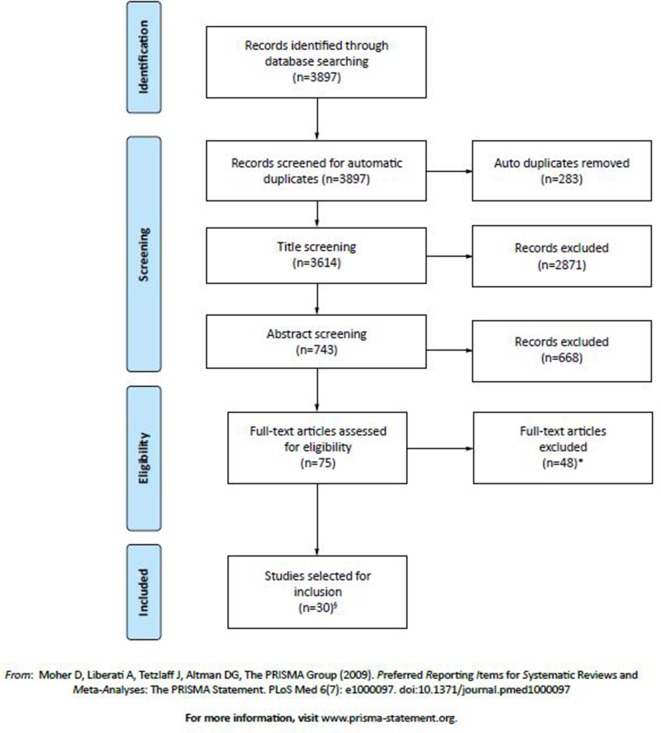

Overall, 3897 articles were identified from the literature search; 3614 were screened for title/abstract and 75 were assessed for eligibility (figure 1). Thirty articles were included in the SLR (see online supplementary table 1), including three identified from reference lists.31–33 The articles described the findings of 28 independent studies. There was nil disagreement between the two independent researchers (PS, GY) during the screening process.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and selection of studies presented in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. *Studies were excluded for the following reasons: outcome measure(s) of persistence and/or adherence, relevant to this systematic review (such as medication possession rate, proportion of days covered, discontinuation rate), were not presented within the full text of the article (n=17); adherence/persistence data were drawn from surveys, interviews or self-reports (n=13); cohort contained a portion of patients under 18 years of age (who could not be removed or isolated from results/data) (n=7); participants had prior awareness/knowledge of partaking in a study related to overactive bladder (OAB) medication (ie, open-label extension to a study or prior written consent) (n=6); a full article text was not available (ie, only a conference abstract) or the full text was not in English (n=4); or non-oral OAB medications were included within the presented results (and could not be removed or isolated from results/data) (n=1). §Three of these studies were identified by reviewing reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic literature reviews.

The data were collected from patients treated in Europe (12 studies) and North America (18 studies) (see online supplementary table 1) and were included in the analysis. The number of participants included in the published studies ranged from 377 to 103 250. Where stated, the mean age of the participants ranged from 44 to 80 years and the duration of follow-up ranged from 6 months to 7 years. Prescribed antimuscarinic interventions for patients with OAB included darifenacin, fesoterodine, flavoxate, hyoscyamine, imipramine, oxybutynin, propiverine, solifenacin, tolterodine and trospium chloride. Mirabegron was prescribed in four studies.18 26 31 34 Uncommon oral interventions included imipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant with an unknown mechanism of action in the context of OAB,35 and bethanechol, a muscarinic receptor agonist.33 The methods used to quantify adherence and persistence differed across the studies (see online supplementary table 1). In general, medication possession rate (MPR) or proportion of days covered (PDC) by prescription were typically used as a measure of adherence to a drug. Persistence was typically defined as the proportion of patients continuing therapy/refilling prescriptions for the follow-up period (without discontinuing the index drug or switching to other OAB drug(s)) and/or the median time to discontinuation (TTD).

bmjopen-2018-021889supp002.pdf (205.1KB, pdf)

Persistence

Overall, persistence rates decreased over time, regardless of agent (see online supplementary table 2).

bmjopen-2018-021889supp003.pdf (304.7KB, pdf)

Antimuscarinic studies

Data for persistence (or discontinuation) at approximately 6 months was available in 14 articles32 33 36–47 which reported data on antimuscarinics only. Yeaw et al was an exception due to the inclusion of bethanechol (a muscarinic receptor agonist), which accounted for <1.5% of the pharmacy claims for OAB medications.33 The proportion of patients persistent at 6 months was <50% except for the studies of Sicras-Mainar et al,42–44 where persistence ranged from 57% to 71%. In addition, two studies reported discontinuation rates of 6%–43% after 1 month of initial treatment.41 47

At 1 year, persistence rates for antimuscarinics across 19 studies ranged from around 5% up to 47%.18 26 33–36 38 40 42 43 45–53 Median TTD was <5 months (30 to 128 days) for all medications across all studies,18 26 32 34 38 48 49 with the exception of Krhut et al 40 (6.5 months). At 2 years, over 75% of patients discontinued treatment.36 38 49–51 Rates of treatment switching were infrequently reported, and where provided, were ≤17% of patients.32 37 39 48 49 51 52

Antimuscarinic and mirabegron studies

In all four studies, a greater proportion of patients persisted with mirabegron compared with antimuscarinics. In one study, persistence rates for tolterodine and mirabegron at 6 months were 19% and 35%, respectively.31 Persistence at 1 year ranged from 8% to 25% for antimuscarinics and from 32% to 38% for mirabegron, as reported in three studies.18 26 34 Where tested inferentially, 1 year persistence was statistically significantly greater with mirabegron compared with antimuscarinics (p<0.0001), with the exception of oxybutynin (p=0.002).18 The risk of discontinuing within 1 year was also greater with antimuscarinics compared with mirabegron (p<0.001).18 26 Overall, mirabegron, solifenacin and fesoterodine were associated with the highest rates of persistence.18 26

Across the four studies, 40%–81% and 83%–96% of the mirabegron and antimuscarinic patient cohorts were treatment naïve, having received no OAB drug for at least 6 months prior to their first index of OAB treatment.18 26 31 34 Studies typically found that treatment-naive patients prescribed mirabegron or antimuscarinics had lower persistence than treatment-experienced patients prescribed the same OAB treatments. In the three studies that assessed persistence in treatment-experienced and treatment-naïve populations, persistence was higher with mirabegron treatment (significantly in two studies) compared with antimuscarinics.18 26 31

Median TTD in the overall study populations was longer with mirabegron (5.6–7.4 months) compared with the assessed antimuscarinics (1.0–3.6 months).18 26 31 34

Adherence

Adherence rates to all OAB medications reduced over time in all studies and varied across studies (see online supplementary table 2).

Antimuscarinic studies

At 1 year, the proportion of adherent patients varied between 1%47 and 36%,48 across those studies that provided these data. Few studies reported adherence beyond 1 year. However, Sears et al reported that 34% of patients were adherent at the end of 3 years,53 which was comparable to the adherence rates reported by some other studies at just 1 year.48 52

Antimuscarinic and mirabegron studies

In the three studies, adherence at 1 year was significantly higher in patients receiving mirabegron compared with antimuscarinics (mean MPR: 0.59 vs 0.41 to 0.53; mean PDC: 0.66 vs 0.55; and median MPR: 0.65 vs 0.19 to 0.49).18 26 34 The proportion of patients adherent at 1 year was also greater with mirabegron compared with antimuscarinics (mean MPR ≥0.80: 43% vs 22%–35%; mean PDC ≥0.80: 44% vs 31%).18 26 Within treatment-naive patients specifically, adherence was greater with mirabegron compared with antimuscarinics, 0.59 vs 0.39–0.51, p values 0.02 to <0.0001).18

Determinants of persistence and adherence

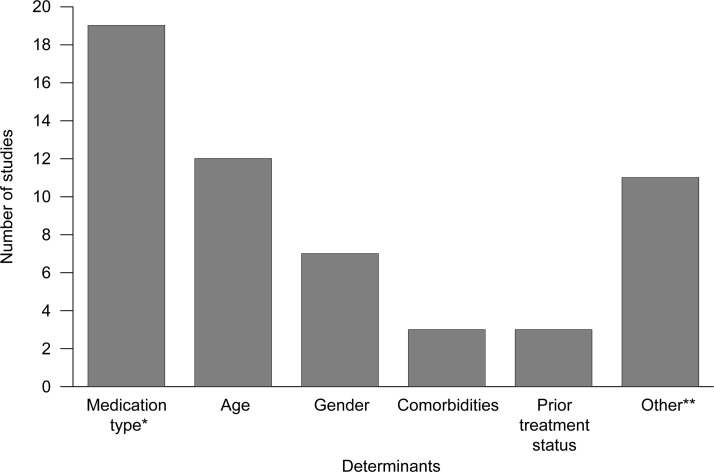

Determinants of persistence and adherence were reported in 24 of the 30 studies. As expected, most studies reported medication type as a determinant of persistence/adherence (figure 2; see online supplementary table 2). In general, persistence and adherence were higher in: older patients compared with younger patients26 31 32 35–39 46 48–50 52 54 55; female patients compared with their male counterparts,32 35 36 39 50 54 55 except in one study53; patients receiving extended-release (ER) formulations compared with immediate-release formulations48 49; and treated patients compared with treatment naive patients (or untreated in the preindex period (6 months or 1 year)).18 26 36 Comorbidities, including diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, dementia, multiple sclerosis and hypertension, were correlated with increased treatment persistence and adherence50 54 55; exceptions were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and migraine.50 55

Figure 2.

Frequency for reported determinants of discontinuation. *In one study, the relationship was not statistically significant. **Includes dose, formulation, race, prior infection, financial burden, prescriber profession, side effects, medication copayment and polypharmacy.

Other reported determinants of favourable persistence and adherence included higher treatment doses36; low daily quantity of tablets37; absence of UTI; higher-baseline OAB costs39; treatment by urologists versus gynaecologists/general practitioners; the absence of side effects (headache, stomach upset and glaucoma)50; White versus Black, Hispanic and Asian patients and patients of other ethnicities35 47; lower medication copayment35; and use of fewer medications.47

Discussion

This systematic review provides an overview of persistence and adherence with oral pharmacotherapies used to treat patients with OAB in real-life clinical practice. A wealth of data were collected from 30 articles, which described 28 observational studies performed in Europe and North America totalling over 500 000 patients. A number of key findings were identified, including greater persistence and adherence with mirabegron versus antimuscarinics,18 26 31 34 in women versus men,32 35 39 54 55 in older versus younger patients,26 31 32 35–39 46 48–50 52 54 55 and in previously treated versus untreated patients.18 26 36

Across the studies, persistence appeared to reduce very quickly after initiation of treatment for all OAB therapies, with low rates (<50%) already evident at 1 month.31 41 47 Longer follow-up periods showed that large proportions of patients discontinued treatment by 1 year (62%–100%)18 26 33 38 45–47 49 50 54 and by the end of 3 years, less than 10% of patients continued on any antimuscarinic.49 These steep reductions in rates of persistence over time were mirrored by the reported adherence rates.

The chronic nature of OAB means that consistent and long-term use of medication is essential to manage OAB symptoms and improve health outcomes. It is therefore important for patients to receive a first-line treatment that has a good efficacy-tolerability profile and evidence of favourable persistence and adherence versus other treatment options. Among the antimuscarinics, solifenacin and fesoterodine were generally associated with better persistence and adherence.18 26 43 52 In studies that assessed both mirabegron and antimuscarinics, persistence in the mirabegron cohorts, including the treatment-naive populations, was statistically significantly greater (p<0.001).18 26 31 Due to the recommended treatment sequence for OAB,10 56 the majority of patients that receive mirabegron are treatment-experienced; however, these studies suggest a benefit of mirabegron treatment regardless of treatment status. Adherence to mirabegron was also greater; however, mean/median MPR values in the overall mirabegron populations did not indicate medication adherence (MPR/PDC<0.80). Although these studies did not directly assess the reason(s) for an observed difference in persistence and adherence with mirabegron versus antimuscarinics, proposed reasons include lower rates of bothersome anticholinergic adverse events, particularly dry-mouth, and unmet expectations of antimuscarinic treatment.18 26 31

It is well established that poor medication persistence and adherence reduces the ability to achieve optimum clinical benefits and limits treatment success, especially for chronic conditions such as OAB.13 14 17 46 The unwillingness of patients to continue to take long-term treatment has been observed across many chronic conditions, with non-adherence to medication observed in ~50% of patients.13 An analysis across six chronic conditions found 1 year persistence and adherence rates to be low for all conditions, and lowest for OAB medications (antimuscarinics),33 suggesting an unmet treatment need. However, this study was performed prior to the availability of mirabegron for use in routine clinical practice, and therefore an updated analysis of persistence in chronic conditions might be warranted.

As alluded to above, persistence and adherence to treatment is expected to improve outcomes for patients with OAB. In two studies, better OAB treatment persistence and adherence were associated with improved clinical outcomes and HRQoL compared with patients who were non-persistent.15 16 These data are consistent with studies describing other chronic diseases, such as diabetes and depression, where good adherence resulted in improved health outcomes14 57 as well as reduced complications and disability, and improved HRQoL and life expectancy.58 Moreover, greater persistence and adherence to treatment for OAB is associated with significantly lower medical, sick leave and short-term disability costs.35 Indeed, economic models based on real-world inputs suggest that improved persistence with mirabegron translates into benefits of reduced healthcare resource use, and lower direct and indirect costs of treatment compared with antimuscarinics.27 59 Additionally, mirabegron is reported to be cost-effective versus six antimuscarinics from commercial and medicare perspectives in the USA, due to fewer projected adverse events and comorbidities, and data suggesting better persistence.60

Independent variables for treatment discontinuation were studied by at least half of the papers included in our literature review, of which sex, age, comorbidities and previous experience of OAB medications were shown to be important factors in more than two studies. Only six studies reported switch rates and although these were low, the treatment strategy of cycling antimuscarinic agents in patients who do not achieve symptom relief is common in clinical practice. Yet, recent analysis of real-world data suggests that switching antimuscarinics may provide suboptimal care.51 In contrast, switching to mirabegron from antimuscarinic therapy has proven beneficial in over 50% of patients with OAB in an observational study.61

This review represents a large pooled analysis of real-world data for persistence and adherence to oral OAB medication across different geographical locations (Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Norway, Spain, the UK and the USA); however, there were no identifiable trends between data and countries. The definitions and calculations of persistence and adherence were not uniform across the literature and the terms were often used interchangeably. This lack of consistency led to some limitations on the ability to compare across studies. Other limitations to performing cross-study comparisons or pooled analyses in this SLR include differences in the individual study populations and/or study designs, resulting in considerable variations between data. For example, the median TTD for oxybutynin ER and tolterodine ER were determined to be 5.1 and 5.5 months, respectively, by one study,49 but only 60 and 56 days, respectively, by another study.18

Furthermore, it is very difficult to capture the specific reasons for treatment discontinuation from prescription-driven or medical claim data rather than patient-derived data.18 The current review excluded data from RCTs to better reflect patient behaviour in the general OAB population in real-life clinical practice.11 Only one paper included in our review reported that antimuscarinic side effects were significantly associated with discontinuation,50 despite reports that such side effects are bothersome and a common reason for discontinuation of antimuscarinic treatment.11 19 28 Additional factors that could not be assessed by our study, but can influence persistence with treatment in OAB patients, are patient expectations, appropriate counselling and patient satisfaction with treatment.11 17 28

In addition to the limitations listed above, it should be noted that Sicras-Mainar et al 42 43 reported data on the same patients (in terms of demographics and the time frame/geographical source). This is also the case for two studies published by Sicras-Mainar et al in 2013 and 2014.62 63 Also, this SLR excluded data on non-oral pharmacotherapies (eg, onabotulinum toxin A) and combination mirabegron plus antimuscarinic therapies, where additional efficacy has been reported compared with the monotherapies.64 Further research on persistence and adherence to these OAB therapies is needed to better evaluate current treatment options. Additional studies are also required to improve our understanding of persistence and adherence in OAB, including qualitative studies to examine the reasons for discontinuation and real-world studies to examine resource use associated with OAB medication in relation to adherence and persistence. As OAB is a chronic disease, clinicians should not only take into consideration the efficacy and side effects of an agent when deciding on treatment options, but also ensure that realistic patient expectations from treatment are set through patient education and counselling. The patient’s lifestyle should also be considered as this is likely to impact adherence and persistence with OAB therapy.

Conclusions

Persistence and adherence were greater with mirabegron compared with antimuscarinics, and appeared to be greater with solifenacin and fesoterodine compared with other antimuscarinics. In addition, greater persistence and adherence were generally observed in patients who were female, older, treatment-experienced and receiving ER formulations. Together with the efficacy and tolerability data from clinical trials, real-world data examined in this review warrant consideration of using mirabegron as first-line oral pharmacotherapy for patients with OAB.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Claire Chinn, PhD, and Kinnari Patel, PhD, of Bioscript Medical.

Footnotes

Contributors: GY, PS, JN, ZH, ES and FF were involved in conceptualisation and design of the study and critical review of the manuscript. FF, PS and GY performed the data extraction. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: The study and medical writing support were supported by Astellas Pharma Global Development.

Competing interests: JN and ES are employed by Astellas Pharma. FF has received a grant from Astellas for study design, data extraction and manuscript development. ZH was an employee of Astellas Pharma when the research was conducted

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The search strategy and all data supporting this study are provided as supplementary information accompanying this paper.

References

- 1. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. . The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2002;21:167–78. 10.1002/nau.10052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eapen RS, Radomski SB. Review of the epidemiology of overactive bladder. Res Rep Urol 2016;8:71–6. 10.2147/RRU.S102441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown JS, McGhan WF, Chokroverty S. Comorbidities associated with overactive bladder. Am J Manag Care 2000;6:S574–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Subak LL, Richter HE, Hunskaar S. Obesity and urinary incontinence: epidemiology and clinical research update. J Urol 2009;182:S2–7. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coyne KS, Payne C, Bhattacharyya SK, et al. . The impact of urinary urgency and frequency on health-related quality of life in overactive bladder: results from a national community survey. Value Health 2004;7:455–63. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.74008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Kopp ZS, et al. . The impact of overactive bladder on mental health, work productivity and health-related quality of life in the UK and Sweden: results from EpiLUTS. BJU Int 2011;108:1459–71. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.10013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Herschorn S. Global perspective of treatment failures. Can Urol Assoc J 2013;7:170–1. 10.5489/cuaj.1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Irwin DE, Mungapen L, Milsom I, et al. . The economic impact of overactive bladder syndrome in six Western countries. BJU Int 2009;103:202–9. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08036.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Onukwugha E, Zuckerman IH, McNally D, et al. . The total economic burden of overactive bladder in the United States: a disease-specific approach. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:S90–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lucas M, Bedretdinova D, Berghmans L, et al. , 2015. European Association of Urology. Guidelines on urinary incontinence http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/20-Urinary-Incontinence_LR1.pdf (Accessed Oct 2016).

- 11. Kim TH, Lee KS. Persistence and compliance with medication management in the treatment of overactive bladder. Investig Clin Urol 2016;57:84–93. 10.4111/icu.2016.57.2.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. . Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008;11:44–7. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown MT, Bussell J, Dutta S, et al. . Medication adherence: truth and consequences. Am J Med Sci 2016;351:387–99. 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization, 2003. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en/ (Accessed Nov 2016).

- 15. Andy UU, Arya LA, Smith AL, et al. . Is self-reported adherence associated with clinical outcomes in women treated with anticholinergic medication for overactive bladder? Neurourol Urodyn 2016;35:738–42. 10.1002/nau.22798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim TH, Choo MS, Kim YJ, et al. . Drug persistence and compliance affect patient-reported outcomes in overactive bladder syndrome. Qual Life Res 2016;25:2021–9. 10.1007/s11136-015-1216-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, et al. . Patient-reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int 2010;105:1276–82. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09036.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chapple CR, Nazir J, Hakimi Z, et al. . Persistence and adherence with mirabegron versus antimuscarinic agents in patients with overactive bladder: a retrospective observational study in UK clinical practice. Eur Urol 2017;72:389–99. 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sexton CC, Notte SM, Maroulis C, et al. . Persistence and adherence in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome with anticholinergic therapy: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract 2011;65:567–85. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02626.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Veenboer PW, Bosch JL. Long-term adherence to antimuscarinic therapy in everyday practice: a systematic review. J Urol 2014;191:1003–8. 10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. European Medicines Agency, 2016. Mirabegron summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002388/WC500137309.pdf (Accessed Dec 2016).

- 22. Food and Drug Administration, 2012. Drug approval package. Myrbetriq (mirabegron) extended release tablets. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2012/202611Orig1s000TOC.cfm

- 23. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, 2017. Betanis. Review of deliberation results. http://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000204240.pdf

- 24. Maman K, Aballea S, Nazir J, et al. . Comparative efficacy and safety of medical treatments for the management of overactive bladder: a systematic literature review and mixed treatment comparison. Eur Urol 2014;65:755–65. 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kobayashi M, Nukui A, Kamai T. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antimuscarinic agents and the selective β3-Adrenoceptor agonist, mirabegron, for the treatment of overactive bladder: which is more preferable as an initial treatment? Low Urin Tract Symptoms 2018;10:158–66. 10.1111/luts.12153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wagg A, Franks B, Ramos B, et al. . Persistence and adherence with the new beta-3 receptor agonist, mirabegron, versus antimuscarinics in overactive bladder: Early experience in Canada. Can Urol Assoc J 2015;9:343–50. 10.5489/cuaj.3098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nazir J, Berling M, McCrea C, et al. . Economic impact of mirabegron versus antimuscarinics for the treatment of overactive bladder in the UK. Pharmacoecon Open 2017;1:25–36. 10.1007/s41669-017-0011-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Basra RK, Wagg A, Chapple C, et al. . A review of adherence to drug therapy in patients with overactive bladder. BJU Int 2008;102:774–9. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07769.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010;8:336–41. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nitti VM, Rovner ES, Franks B, et al. . Persitence with mirabegron versus tolterodine in patients with overactive bladder. Am J Pharm Benefits 2016;8:e25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wagg A, Diles D, Berner T. Treatment patterns for patients on overactive bladder therapy: a retrospective statistical analysis using Canadian claims data. JHEOR 2015;3:43–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yeaw J, Benner JS, Walt JG, et al. . Comparing adherence and persistence across 6 chronic medication classes. J Manag Care Pharm 2009;15:728–40. 10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.9.728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sussman D, Yehoshua A, Kowalski J, et al. . Adherence and persistence of mirabegron and anticholinergic therapies in patients with overactive bladder: a real-world claims data analysis. Int J Clin Pract 2017;71:e12824 10.1111/ijcp.12824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kleinman NL, Odell K, Chen CI, et al. . Persistence and adherence with urinary antispasmodic medications among employees and the impact of adherence on costs and absenteeism. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:1047–56. 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.10.1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brostrøm S, Hallas J. Persistence of antimuscarinic drug use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2009;65:309–14. 10.1007/s00228-008-0600-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Desgagné A, LeLorier J. Incontinence drug utilization patterns in Québec, Canada. Value Health 1999;2:452–8. 10.1046/j.1524-4733.1999.26005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM. Comparative adherence to oxybutynin or tolterodine among older patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012;68:97–9. 10.1007/s00228-011-1090-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ivanova JI, Hayes-Larson E, Sorg RA, et al. . Healthcare resource use and costs of privately insured patients who switch, discontinue, or persist on anti-muscarinic therapy for overactive bladder. J Med Econ 2014;17:741–50. 10.3111/13696998.2014.941066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krhut J, Gärtner M, Petzel M, et al. . Persistence with first line anticholinergic medication in treatment-naïve overactive bladder patients. Scand J Urol 2014;48:79–83. 10.3109/21681805.2013.814707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Perfetto EM, Subedi P, Jumadilova Z. Treatment of overactive bladder: a model comparing extended-release formulations of tolterodine and oxybutynin. Am J Manag Care 2005;11:S150–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Ruiz-Torrejón A, et al. . Impact of loss of work productivity in patients with overactive bladder treated with antimuscarinics in Spain: study in routine clinical practice conditions. Clin Drug Investig 2015;35:795–805. 10.1007/s40261-015-0342-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Ruiz-Torrejón A, et al. . Persistence and concomitant medication in patients with overactive bladder treated with antimuscarinic agents in primary care. An observational baseline study. Actas Urol Esp 2016;40:96–101. 10.1016/j.acuro.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sicras-Mainar A, Rejas-Gutiérrez J, Navarro-Artieda R, et al. . Use of health care resources and associated costs in non-institutionalized vulnerable elders with overactive bladder treated with antimuscarinic agents in the usual medical practice. Actas Urol Esp 2014;38:530–7. 10.1016/j.acuro.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Suehs BT, Davis C, Franks B, et al. . Effect of potentially inappropriate use of antimuscarinic medications on healthcare use and cost in individuals with overactive bladder. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:779–87. 10.1111/jgs.14030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wagg A, Compion G, Fahey A, et al. . Persistence with prescribed antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder: a UK experience. BJU Int 2012;110:1767–74. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11023.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yu YF, Nichol MB, Yu AP, et al. . Persistence and adherence of medications for chronic overactive bladder/urinary incontinence in the california medicaid program. Value Health 2005;8:495–505. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.00041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. D’Souza AO, Smith MJ, Miller LA, et al. . Persistence, adherence, and switch rates among extended-release and immediate-release overactive bladder medications in a regional managed care plan. J Manag Care Pharm 2008;14:291–301. 10.18553/jmcp.2008.14.3.291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gopal M, Haynes K, Bellamy SL, et al. . Discontinuation rates of anticholinergic medications used for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:1311–8. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818e8aa4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kalder M, Pantazis K, Dinas K, et al. . Discontinuation of treatment using anticholinergic medications in patients with urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:794–800. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chancellor MB, Migliaccio-Walle K, Bramley TJ, et al. . Long-term patterns of use and treatment failure with anticholinergic agents for overactive bladder. Clin Ther 2013;35:1744–51. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mauseth SA, Skurtveit S, Spigset O. Adherence, persistence and switch rates for anticholinergic drugs used for overactive bladder in women: Data from the norwegian prescription database. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013;92:n/a–15. 10.1111/aogs.12196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sears CL, Lewis C, Noel K, et al. . Overactive bladder medication adherence when medication is free to patients. J Urol 2010;183:1077–81. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Johnston S, Janning SW, Haas GP, et al. . Comparative persistence and adherence to overactive bladder medications in patients with and without diabetes. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:1042–51. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.03009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pelletier EM, Vats V, Clemens JQ. Pharmacotherapy adherence and costs versus nonpharmacologic management in overactive bladder. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:S108–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Mirabegron for treating symptoms of overactive bladder. 2013.

- 57. Thompson C, Peveler RC, Stephenson D, et al. . Compliance with antidepressant medication in the treatment of major depressive disorder in primary care: a randomized comparison of fluoxetine and a tricyclic antidepressant. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:338–43. 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Anderson BJ, Vangsness L, Connell A, et al. . Family conflict, adherence, and glycaemic control in youth with short duration Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2002;19:635–42. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00752.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hakimi Z, Nazir J, McCrea C, et al. . Clinical and economic impact of mirabegron compared with antimuscarinics for the treatment of overactive bladder in Canada. J Med Econ 2017;20:614–22. 10.1080/13696998.2017.1294595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wielage RC, Perk S, Campbell NL, et al. . Mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder: cost-effectiveness from US commercial health-plan and Medicare Advantage perspectives. J Med Econ 2016;19:1135–43. 10.1080/13696998.2016.1204307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Liao CH, Kuo HC. High satisfaction with direct switching from antimuscarinics to mirabegron in patients receiving stable antimuscarinic treatment. Medicine 2016;95:e4962 10.1097/MD.0000000000004962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sicras-Mainar A, Rejas J, Navarro-Artieda R, et al. . Antimuscarinic persistence patterns in newly treated patients with overactive bladder: a retrospective comparative analysis. Int Urogynecol J 2014;25:485–92. 10.1007/s00192-013-2250-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sicras-Mainar A, Rejas J, Navarro-Artieda R, et al. . Health economics perspective of fesoterodine, tolterodine or solifenacin as first-time therapy for overactive bladder syndrome in the primary care setting in Spain. BMC Urol 2013;13:51 10.1186/1471-2490-13-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Drake MJ, Chapple C, Esen AA, et al. . Efficacy and safety of mirabegron add-on therapy to solifenacin in incontinent overactive bladder patients with an inadequate response to initial 4-week solifenacin monotherapy: a randomised double-blind multicentre phase 3B study (BESIDE). Eur Urol 2016;70:136–45. 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-021889supp001.pdf (249.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-021889supp002.pdf (205.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-021889supp003.pdf (304.7KB, pdf)