Abstract

The appearance of voltage-gated, sodium-selective channels with rapid gating kinetics was a limiting factor in the evolution of nervous systems. Two rounds of domain duplications generated a common 24 transmembrane segment (4 × 6 TM) template that is shared amongst voltage-gated sodium (Nav1 and Nav2) and calcium channels (Cav1, Cav2, and Cav3) and leak channel (NALCN) plus homologs from yeast, different single-cell protists (heterokont and unikont) and algae (green and brown). A shared architecture in 4 × 6 TM channels include an asymmetrical arrangement of extended extracellular L5/L6 turrets containing a 4-0-2-2 pattern of cysteines, glycosylated residues, a universally short III-IV cytoplasmic linker and often a recognizable, C-terminal PDZ binding motif. Six intron splice junctions are conserved in the first domain, including a rare U12-type of the minor spliceosome provides support for a shared heritage for sodium and calcium channels, and a separate lineage for NALCN. The asymmetrically arranged pores of 4x6 TM channels allows for a changeable ion selectivity by means of a single lysine residue change in the high field strength site of the ion selectivity filter in Domains II or III. Multicellularity and the appearance of systems was an impetus for Nav1 channels to adapt to sodium ion selectivity and fast ion gating. A non-selective, and slowly gating Nav2 channel homolog in single cell eukaryotes, predate the diversification of Nav1 channels from a basal homolog in a common ancestor to extant cnidarians to the nine vertebrate Nav1.x channel genes plus Nax. A close kinship between Nav2 and Nav1 homologs is evident in the sharing of most (twenty) intron splice junctions. Different metazoan groups have lost their Nav1 channel genes altogether, while vertebrates rapidly expanded their gene numbers. The expansion in vertebrate Nav1 channel genes fills unique functional niches and generates overlapping properties contributing to redundancies. Specific nervous system adaptations include cytoplasmic linkers with phosphorylation sites and tethered elements to protein assemblies in First Initial Segments and nodes of Ranvier. Analogous accessory beta subunit appeared alongside Nav1 channels within different animal sub-phyla. Nav1 channels contribute to pace-making as persistent or resurgent currents, the former which is widespread across animals, while the latter is a likely vertebrate adaptation.

Keywords: sodium channels, calcium channels, auxiliary beta subunits, evolution, ion selectivity, NALCN, patch clamp electrophysiology, U12-type splice site

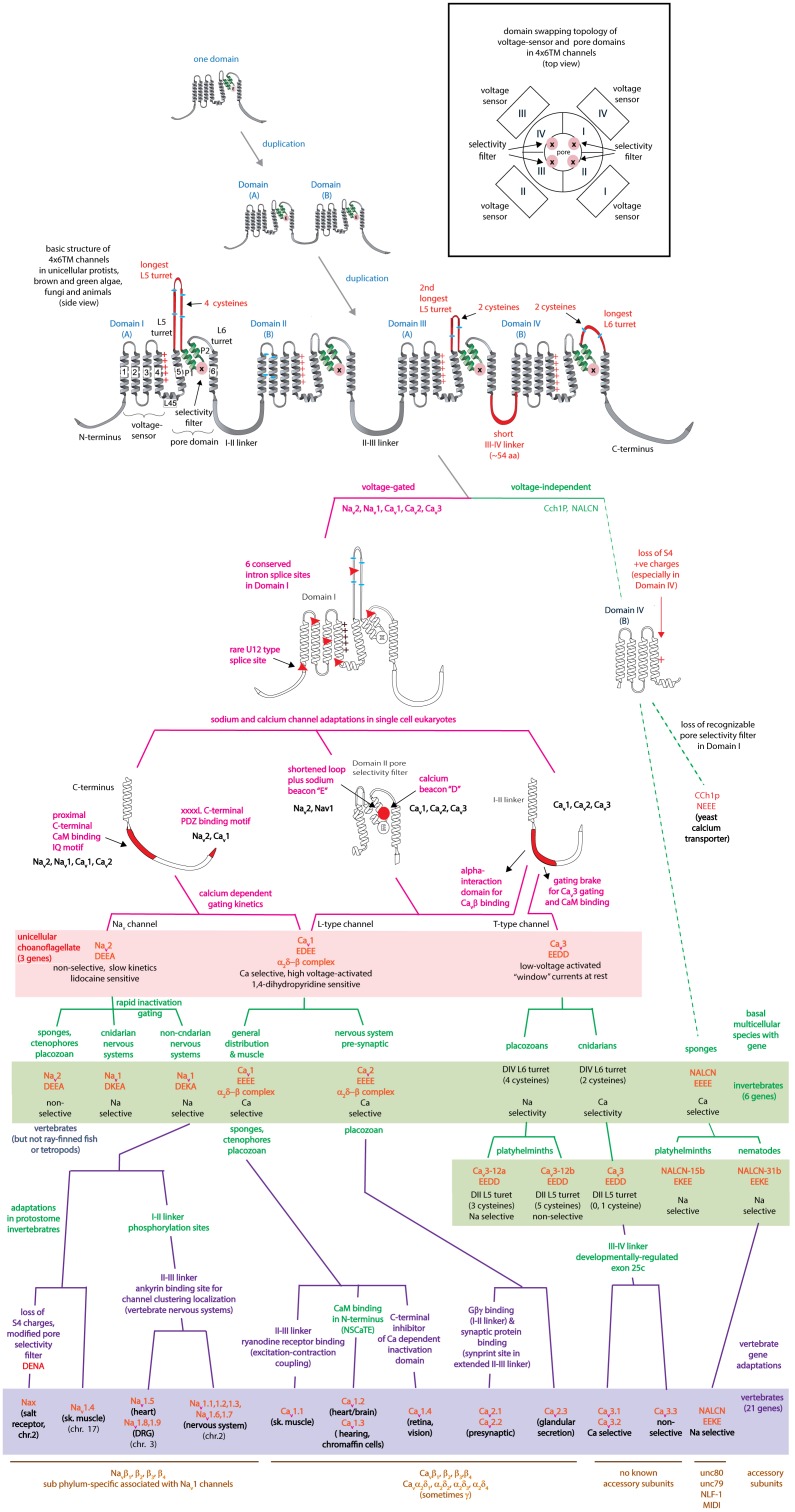

Introduction to the Superfamily of 4 × 6 Tm Voltage-Gated Cation Channels

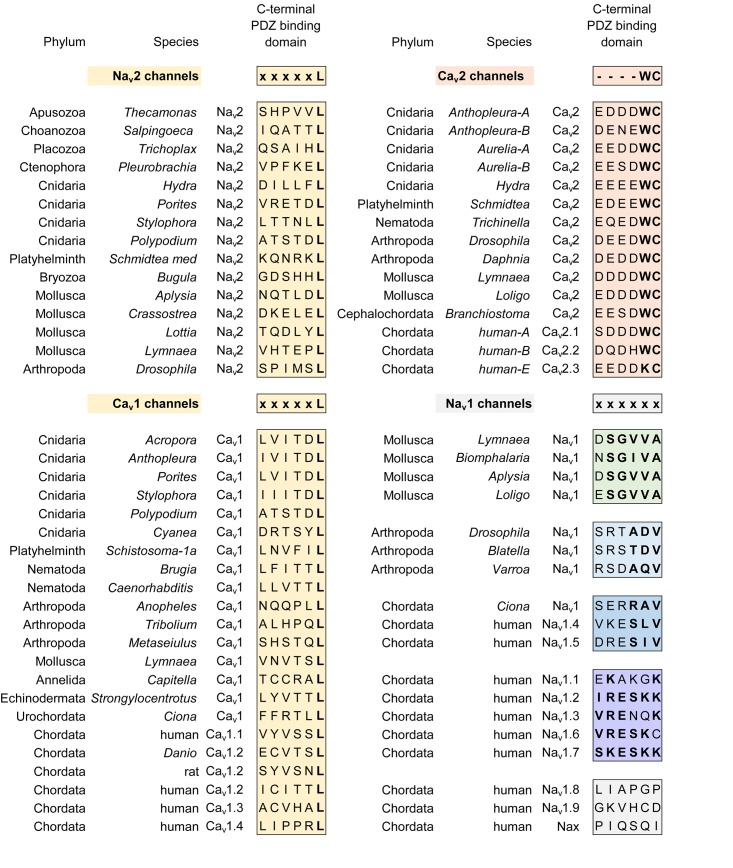

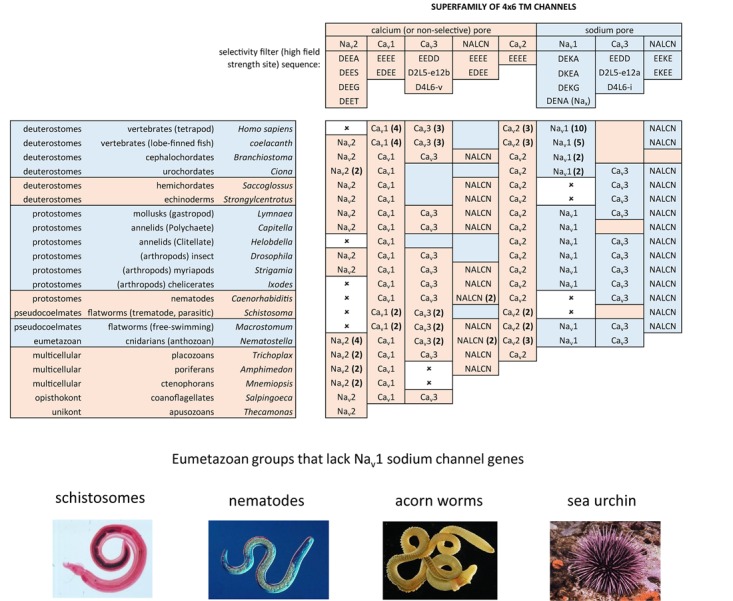

The superfamily of voltage-gated cation channels containing 24 transmembrane segments are classified as sodium-selective, calcium-selective, or non-selective channels that span the plasma membrane. Their gene numbers, their expression patterns and functions have been reported in differing body plans that range from single cell eukaryotes, to invertebrates, to the greatest gene complexity of ion channel isoforms in vertebrates. There are twenty-one mammalian genes : Ten are sodium channel (SCNxA) genes coding for Nav1.1 to Nav1.9 (Catterall et al., 2005a), expressing mostly sodium-selective currents and Nax (Noda and Hiyama, 2015); Ten are calcium channel (CACNA1x) genes, coding for Cav1.1 to Cav1.4, Cav2.1 to Cav2.3, and Cav3.1 to Cav3.3 (Catterall et al., 2005b), that generate mostly calcium-selective channel currents (Figure 1). NALCN is a unique, orphan, leak channel gene within the superfamily of voltage-gated cation channels (Cochet-Bissuel et al., 2014; Figure 1) but are poorly understood, because its ion channel characteristics have not been identified and validated by in vitro expression (Senatore et al., 2013; Senatore and Spafford, 2013; Boone et al., 2014). Here, we start by exploring the features in key extant life forms which provide insights into the evolutionary history of the voltage-gated, sodium-selective channels. The most basal life form for appearance of voltage-gated sodium channel classes is in the single cell eukaryotes (Zakon, 2012). Prokaryotes have representative ion channels for potassium- (Doyle et al., 1998) and sodium-selective (Yue et al., 2002) pores, which provides insights into the selectivity mechanisms of eukaryotic 4 × 6 TM channels.

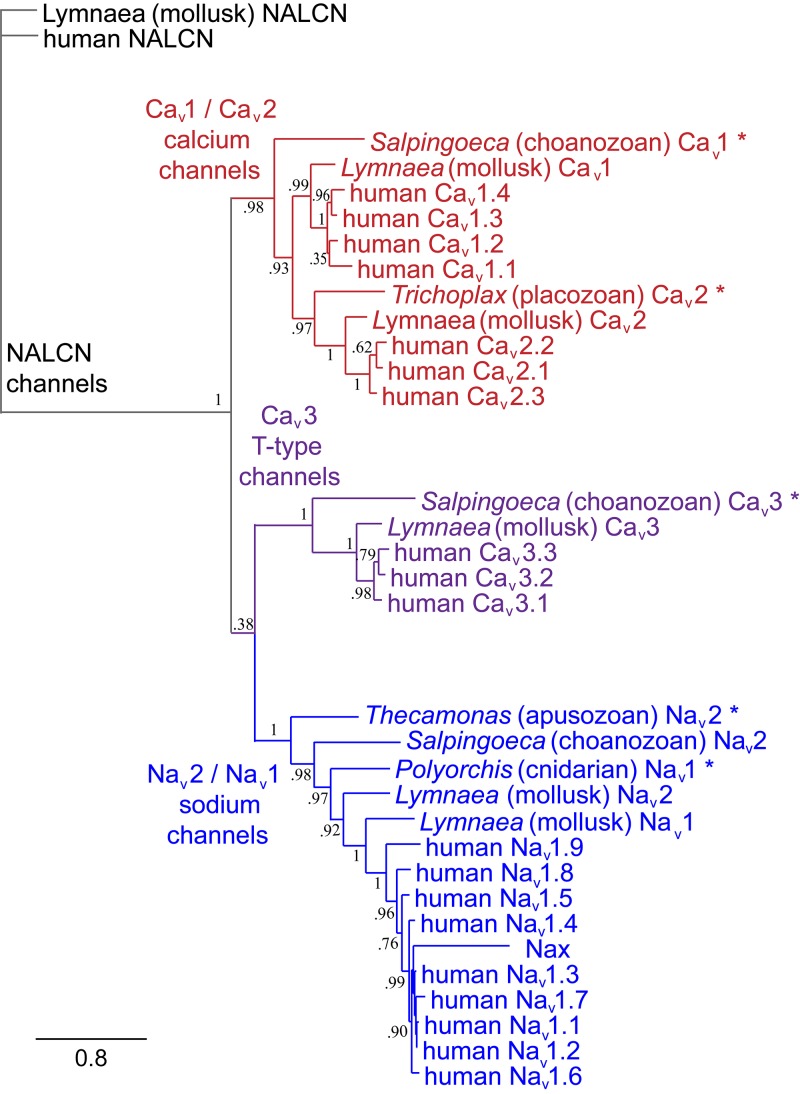

FIGURE 1.

Gene tree of 4 × 6 TM (TM = transmembrane) voltage-gated sodium channel α subunits (Nav1 and Nav2), calcium channel α1 subunits (Cav1, Cav2, and Cav3) and NALCN. Included in the multiple alignment are the 21 human homologs and the 6 homologs from representative protostome invertebrate, pulmonate snail, Lymnaea stagnalis. Basal genes of each class (indicated in bold and ∗) including apusozoan, Thecamonas trahens (Nav2), single cell choanoflagellate, Salpingoeca rosetta (Cav1 and Cav3), placozoan, Trichoplax adhaerens (Cav2), and cnidarians (hydrozoan jellyfish), Polyorchis penicillatus (Nav1). More distant Na Leak Conductance channel (NALCN) serve as the out-group for the phylogenetic tree. Bootstrap values are shown at the nodes. Notably weak branch strength is in the positioning for Cav3 T-type channels which is relatively equidistant from sodium channels and other calcium channels. The gene tree illustrate the close kinship amongst Nav2 and Nav1 channels and between Cav1 and Cav2 channels. Amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE 3.7 (Edgar, 2004) within EMBL-EBI web interface (Chojnacki et al., 2017). Gene trees were constructed in PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., 2010) using Phylogeny.fr web interface (Dereeper et al., 2008).

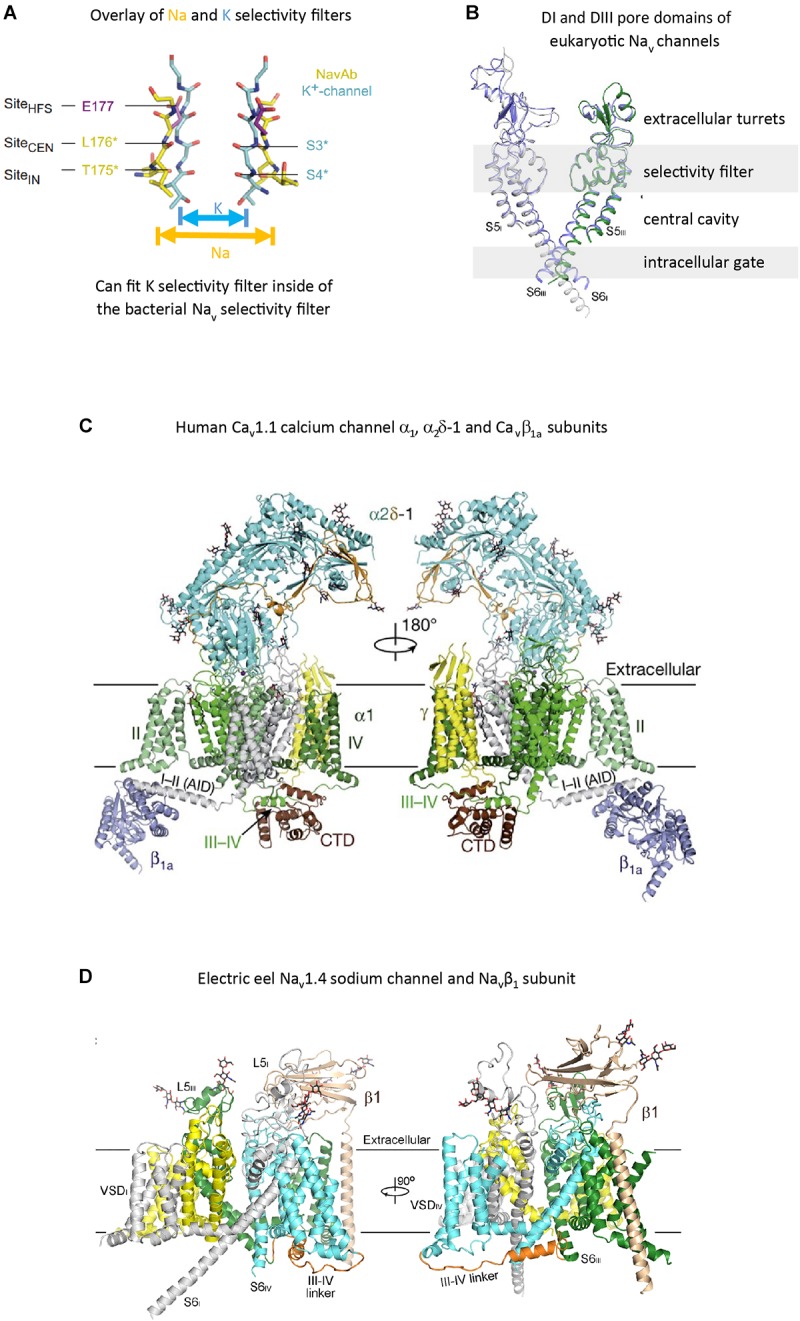

Potassium-Selective, Voltage-Gated Channels Share a Common Pore Structure in Bacteria and Eukaryotes

The voltage-gated (K+, Ca2+, and Na+) channels consist of two semi-autonomous domains, a pore domain that provides an aqueous pathway for ion selection through the plasma membrane, and a voltage-sensor domain, that transduces pore gate movements (opening/closing events), based on changes to the state of the membrane electric field. There are two major templates for the pore domain that first appear in bacterial representatives, one that is a highly selective pore domain for potassium ions (Doyle et al., 1998) and a different pore domain that is selective for sodium ions (Payandeh et al., 2011). The overall structure of pore domains consist of two transmembrane helices (the so-called S5–S6 segments in voltage-gated channels), with an intervening Pore- (P-) loop, that forms a pore lining border that resembles an inverted teepee, including a descending pore helix from the end of S5 and an ascending loop to the end of S6 (Kim and Nimigean, 2016; Figure 2). At the base of the inverted teepee between the pore helices is a pore-selectivity filter that ascends to form the most constricted point of access of ions, between the outer vestibule facing the wide, extracellular milieu above, and the more expansive aqueous lake within the membrane channel below (Kim and Nimigean, 2016) (Figures 3A,B). The first of the high resolution structures of the potassium selective pore is KcSA, a pore only protein isolated from the bacteria, Streptomyces lividans (Doyle et al., 1998). The signature sequence of the potassium selective pore is the five amino acid residues: T(V/I)GYG contributed by each of four subunits forming identical quadrants contributing to the pore lining selectivity filter. The side chains residues face outwards, and the pore-lining backbone carbonyls form an octet of oxygens, serving to accommodate four dehydrated potassium ions, occupied in every other position (1 and 3 or 2 and 4) at one time in potassium channels (Doyle et al., 1998; Figure 3A). The K channel pore achieves an exclusive K ion selectivity because only the K channel will shed its hydration shell, for optimized, energetically favorable binding conditions within the pore selectivity filter, and passage through by electrochemical force generated by a transmembranal ion gradient (Doyle et al., 1998). Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic potassium-selective channels share the same signature, selectivity filter of T(V/I)GYG residues (Kim and Nimigean, 2016).

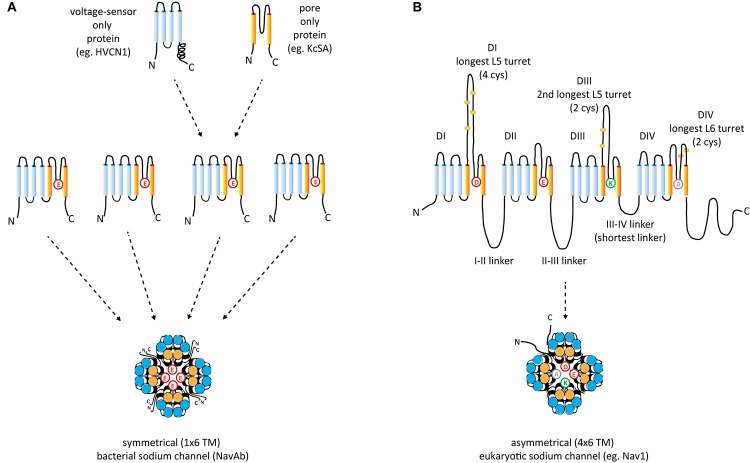

FIGURE 2.

Structural comparisons between (A) symmetrical, 1 × 6 TM (TM = transmembrane) homotetrameric, bacterial Na channels consisting of four repeat subunit (B) asymmetrical, eukaryotic four domain calcium and sodium channels consisting of 24 transmembrane segments (4 × 6 TM). Each of the four sodium and calcium channel domains consist of a voltage-sensor domain of four transmembrane segments, S1–S4 (blue), akin to voltage sensor only protein (e.g., HVCN1) and a pore domain, S5–S6 (orange), resembling the size of the two membrane segments of the inward rectifying K channels (e.g., KcsA). A dramatic difference between the 1 × 6 TM bacterial sodium channels and 4 × 6 TM calcium and sodium channels are the larger sizes of extracellular turrets rising before the pore selectivity filter, especially L5I and L5III which range from 40 to 105 amino acids long. The longest extracellular turret in Domain IV in 4 × 6 TM channels is always the extracellular turret rising after the pore selectivity filter (L6IV), while L5IV (the extracellular loop just before the pore selectivity filter) is always short. Comparatively speaking, 1 × 6 TM channels all possess short extracellular turrets of 10–15 amino acids long. Eight core, conserved cysteines populate the L5I - L5II - L5III - L6IV extracellular turrets in a 4-0-2-2 configuration in all eukaryotic 4 × 6 TM channels. Also novel are singleton N- and C-termini, and cytoplasmic linkers, of which the III-IV linker is almost always 53–57 amino acids long in eukaryotic 4 × 6 TM channels.

FIGURE 3.

High resolution structures of pore selectivity filters, a pore domain and full length voltage gated calcium and sodium channels. (A) Overlay of the structure of the pore selectivity filter of bacterial KcsA potassium channel (Doyle et al., 1998) and bacterial sodium channel NavAb (Payandeh et al., 2012). Only two subunits are shown for clarity. Backbone carbonyls in the selectivity filter are red. The narrower pore selectivity filter for potassium ions fits within the broader selectivity filter for sodium (or calcium) ions. (B) Overlay of Domain I and III pores of arthropod Nav1 and electric eel Nav1.4. Key amino acid side chain residues of the selectivity filter project into the pore center to regulate ion passage through sodium and calcium channels pores. Long extensive extracellular turrets rising from segment 5 to the pore selectivity filter, and shorter extensions from the pore selectivity filter to segment 6 project rise above the membrane, serving as a first contact for incoming ions and drugs, before passing through the selectivity filter below. (C) α1 subunit of the human Cav1.1 calcium channel, illustrating the extended extracellular turret loops of L5I, L5III, L6IV and the intracellular globular domain formed by the III-IV linker and the proximal C-terminal Domain (CTD) containing the calmodulin binding IQ motif. The proximal C-terminus omitted in the right panel to better illustrate the III–IV linker. Accessory α2Δ-1 and β1A subunits are illustrated with the pore-forming α1 subunit. Potential Ca2+ ions in the selectivity filter vestibule are illustrated as green spheres. (D) The structure of the electric eel Nav1.4 (each domain individually colored) and β1(wheat colored) complex, with glycosyl moieties shown as black sticks. The short cytoplasmic III-IV linker (orange color) regulates fast inactivation of Nav1 channels. (A) reproduced from Payandeh, et al (2011). Nature, 10:475(7356):353-8 with permission. (B,D) reproduced from Yan et al. (2017). (C) reproduced from J Wu et al. (2016).

The Four Domains of Eukaryotic Cav and Nav Channels has Resemblances With the Single Domain of the Bacterial Nav Channel

The overall structure for the sodium-selective pore in eukaryotes approximates the unique dimensions of a sodium-selective channel pore identified in bacteria, exemplified by NavAb, the first bacterial sodium channel resolved by X-ray crystallography, isolated from Arcobacter butzleri (Payandeh et al., 2011). The pore selectivity filter is a broader and shorter conduit for ion passage across the membrane, such that one can fit the K ion-selective pore between the dimensions of the bacterial or eukaryotic Na -selective pore (Payandeh et al., 2011; Figures 3A,B). There is an additional pore helix ascending from the ion selectivity filter (P2 helix) in both bacteria sodium channels (Payandeh et al., 2011) and eukaryotic sodium and calcium channels (Wu et al., 2016), in addition to the descending pore helix leading to the ion selectivity filter (P1 helix, also shared in potassium channels), generating a wider and more structured outer vestibule facing the channel exterior.

The equivalent of the potassium channel’s signature residues of the pore selectivity filter is TLESWSM in the bacteria sodium channel (Figure 3A), where the negatively charged carboxylates side chain of the glutamate residue (E) faces towards the pore center (rather than away from the pore center of the K selective pore), creating a highly electronegative, high field strength (HFS) site, contributed by the four glutamates (EEEE) in identical position (Payandeh et al., 2011). At this most constricted width of the Na ion selective pore, is a 4.6 × 4.6 angstrom square HFS site, that is large enough to accommodate a sodium ion with two planar waters of hydration (Payandeh et al., 2011; Figure 3A). This contrasts with the narrow ion traversing pathway where all waters are stripped from the potassium ion before entering the pore selectivity filter (Figure 3A).

Potassium-selective pores can be voltage-gated with addition of N-terminally attached voltage-sensor domains, consisting of four (S1–S4) segments (Groome, 2014). The voltage-sensor is optional in potassium channels, and can operate as a semi-autonomous unit. An example of voltage-sensor only proteins are the voltage-gated proton channels that allow proton transport into phagosomes via the voltage sensor (e.g., human HVCN1) (Takeshita et al., 2014; Figure 2A). All eukaryotic sodium and calcium channels possess voltage-sensor domains like the voltage-gated potassium channel, where the S4 segments have a variable number (4–8) positive charged residues (lysine or arginine) every third amino acid, forming a highly charged side of an alpha helix (Groome, 2014). S4 segments respond to membrane potential changes, by movement of their positive charged residues along negatively charged, counter-charges formed by S1–S3 segments, transducing the mechanical coupling of an amphipathic S4–S5 helix to pore gating movements that lead to iris-like, occlusion or widening of the pore helical bundle formed by the distal ends of S6 segments (Groome, 2014).

Tracing of Domain Duplications to Generate the Four Domain Cav and Nav Channels From a Single Domain Ancestor

Sodium and calcium channels only exist in as voltage-gated channels subunits with voltage-sensors and pore domains (6TM, TM = TransMembrane) fused together, unlike potassium channels which can exist as pore-only proteins (Figure 2A). The 1 × 6 TM bacterial sodium channels have been identified in proteobacteria and actinobacteria, but also have spread to eukaryotes, including diatoms, which they likely have received by horizontal gene transfer from bacteria (Verret et al., 2010).

Typical eukaryotic calcium and sodium channels are always approximately four times the equivalency in size of 1 × 6 TM prokaryotic sodium channels and voltage-gated potassium channels (Figure 2B). The closest homolog to the prokaryotic 1 × 6 TM Na-selective channels are the eukaryotic transient receptor potential (TRP) family of channels, whose members are usually non-selective or sodium selective channels, with exceptions, such as Catsper1 with an electronegative HFS sites which are key for conferring a calcium-selectivity (Wu et al., 2010; Figure 4). Two domain TPC channels are sodium-selective in mammals, but TPC homologs in basal representatives such as Salpingoeca rosetta resemble calcium-selective channels with a glutamate or aspartate in Domains I or II of the HFS site of the pore selectivity filter (Figure 4). The example of differing ion selectivities in TPC channels is suggestive of experimentation between sodium and calcium selective pores in possible two domain channel ancestors to eukaryotic 4 × 6 TM channels (Peng et al., 2015). As expected from a two domain intermediate that duplicated into a four domain channel such as 4 × 6 TM channels (Strong et al., 1993), the first domain of TPC is more similar to Domain I and III of 4 × 6 TM channels and the second domain of TPC is more similar to Domain II and IV of 4 × 6 TM channels (Rahman et al., 2014).

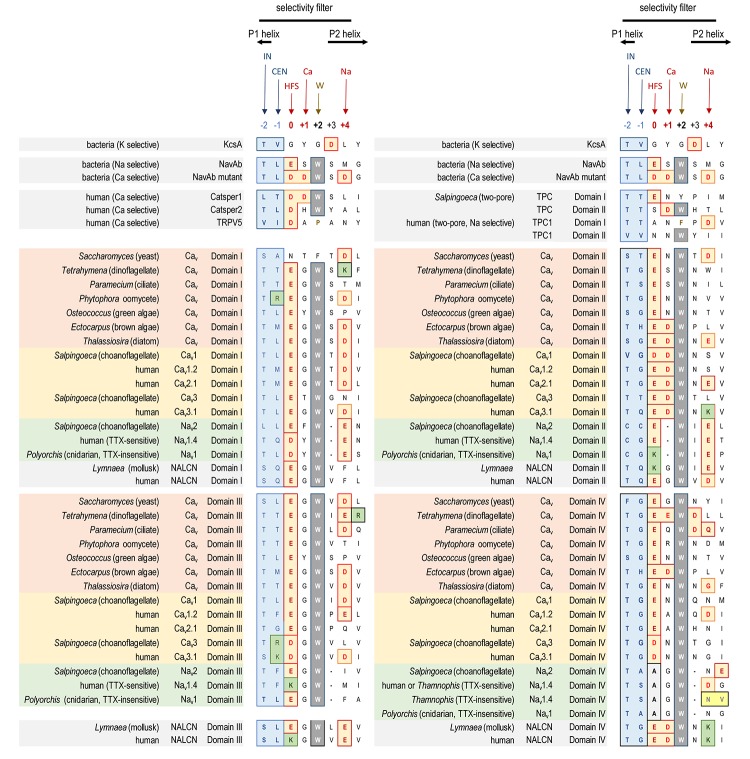

FIGURE 4.

Alignment of amino acid sequences contributing to the pore selectivity filters in representative calcium, sodium and NALCN channel homologs from single cell protists, yeast, algae, invertebrate and human, as well as 2 × 6 TM TPC channels, 1 × 6 TM channels (TRP, Catsper, and bacterial Na), and 1 × 2 TM channels (bacterial K). The pores of 4 × 6 TM channels from brown and green algae, yeast, single-cell choanoflagellates, cnidarian and mollusks are illustrated alongside human representatives, to illustrate the relationship of pore selectivity filters in different life forms. The selectivity filter is flanked by a descending P1 helix and ascending P2 helix. Residues contributing to the central (CEN) and inner (IN) sites of the selectivity filter are highlighted blue. Negative charged residues contributing to the selectivity filters (HFS sites), and to the ring of outer carboxylates are a red/brown color. A positively charged lysine residue (green color) populate the HFS site in Domain II or III of all Nav1 channels. The aspartate (D) residue in Domain II at the Ca site, next to the HFS site, is conserved in Cav1, Cav2 and Cav3 channels. Nav2 and Nav1 channels are shortened in the pore selectivity filter in Domain II and lack the Ca site altogether. Instead, a glutamate (E) residue is conserved at the Na site (HFS+4) in Domain II of Nav2 and Nav1 channels. Exceptionally conserved tryptophans (W site) form inter-repeat hydrogen bonds that stabilize the pore loop region. Outer ring carboxylates (Na site, especially in Domain IV) contribute to TTX sensitivity, which when altered lowers TTX insensitivity. Note the amino acid changes (yellow colored residues) in Domain IV of the TTX-sensitive hNav1.4 and TTX-low sensitive channels from garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) that adapts to feed on TTX-ladened newts by neutralizing a negative charge at the Na site. Bacterial Na channel, NavAb becomes calcium-selective with aspartate (D) substitutions at the HFS, Ca and Na sites. Amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE 3.7 (Edgar, 2004) within EMBL-EBI web interface (Chojnacki et al., 2017).

Evidence in Genomic Structure for a Common Calcium and Sodium Channel Template

All the 4 × 6 TM channels of the superfamily of Cav and Nav channels appear to derive from the same stem eukaryotic channel with a fundamentally shared template. There is evidence in a shared genomic structure: Sodium channels (Nav2 and Nav1) and calcium channels (Cav1, Cav2, and Cav3) in animals possess five common splice site locations in the first of four domains, including each of the first four transmembrane segments (S1–S4) of Domain I of the voltage-sensor domain (D1S1, D1S2, D1S3, and D1S4) and two splice site locations in the pore loop (S5–S6) of Domain I (DIS5-D1S6) (Figure 5). The D1S1 splice site is conserved in almost all known calcium and sodium channels (Spafford et al., 1999) and is a highly rare, unconventional, U12- type (AT-AC) splice site that representing just 700-800 putative genes (or ∼4%) of total genes in mammalian genomes (Parada et al., 2014; Figure 6). The exception in the conservation of splice sites in Domain I is that the 6th splice site in the D1 pore loop is lacking in Cav3 channels (Figure 5). A shared genomic structure in the first of four domain may indicate constraints on the structural divergence of the first domain shared between four domain calcium and sodium channels. These six conserved splice sites are not present in NALCN channels (Figure 5), including the unconventional, U12- type splice site governed by the minor spliceosome shared in homologous position of D1S1 (Figure 5). The lack of conservation of intron splice sites reflects the weaker evolutionary link between NALCN from the cluster of more closely related families of eukaryotic voltage-gated calcium and sodium channels.

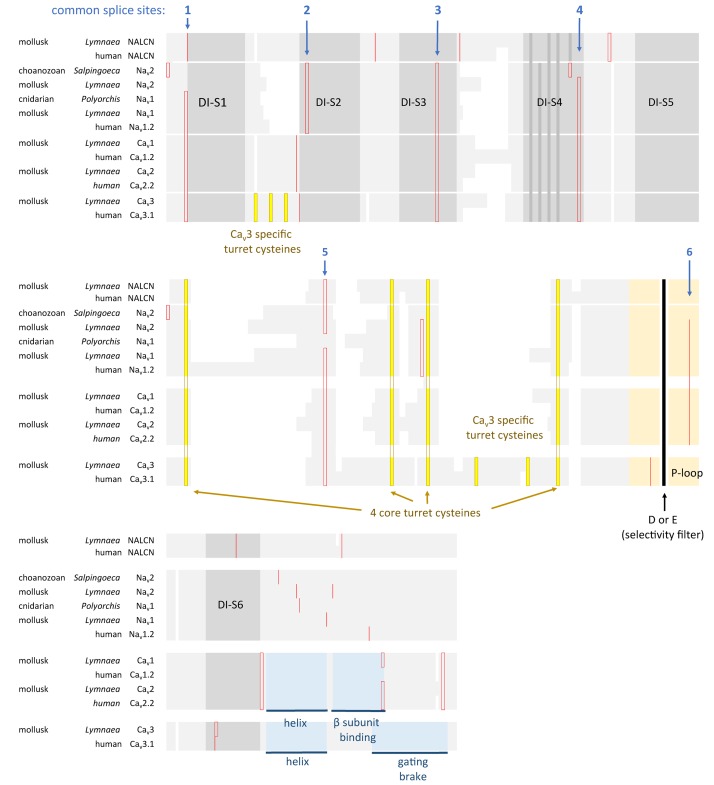

FIGURE 5.

Amino acid alignment of the first domain of representative 4 × 6 TM channels illustrating the conservation of six intron splice sites (red vertical lines) in voltage-gated calcium (Cav1, Cav2, and Cav3) and sodium (Nav1 and Nav2) channels. Conserved placement of intron splice junctions (red vertical lines) span each transmembrane segment of the voltage-sensor domain (D1S1, D1S2, D1S3, and D1S4) and two in the pore loop of Domain I (DIS5-D1S6). The sixth splice site is lacking in Cav3 channels. NALCN lacks all of these splice sites, supporting a more distant relationship for NALCN compared to the eukaryotic calcium and sodium channels. The six membrane spanning helices S1–S6 are indicated in gray shading, with the High Field Strength (HFS) site (D or E) indicated by black vertical line surrounded by the rest of the pore loop region (light orange shading). Darker gray shading in S4 indicate the positions of positive charges serving the voltage-sensor domain. Four cysteine residues are conserved in the extracellular turret (L5) of all 4 × 6TM channels, and the location of two extra cysteines in L5 and S1–S2 are only found in Cav3 T-type channels. Cysteine residues are indicated in a bright yellow color. Illustrated in blue color is a rigid, helix in the proximal I-II cytoplasmic linker, upstream of an accessory CaVβ subunit binding site in Cav1 and Cav2 channels, and the “gating brake” of Cav3 channels which harbors a nano-molar affinity binding site for calmodulin. Genes in the alignment include NALCN, sodium channels (Nav2 and Nav1) and calcium channels (Cav1, Cav2, and Cav3) from human representatives, as well as protostome invertebrate, pond snail L. stagnalis, and basally branching species from single cell choanoflagellate, S. rosetta, placozoan, Trichoplax adhaerens, and cnidarians: Nematostella vectensis (sea-anemone) and Polyorchis penicillatus (hydrozoan jellyfish). Amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE 3.7 (Edgar, 2004) within EMBL-EBI web interface (Chojnacki et al., 2017).

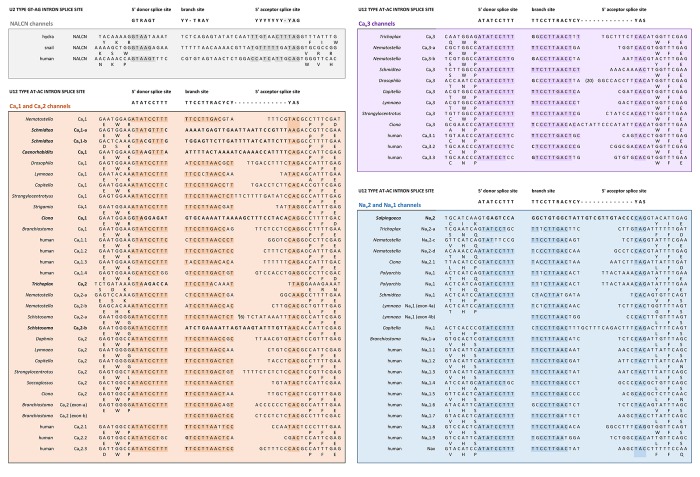

FIGURE 6.

Conservation of a very rare U12 type intron splice site in Domain 1, segment 1 of Nav2, Nav1, Cav1, Cav2, and Cav3 channels, but not NALCN channels. Exceptionally rare U12-type splice site represent just 700–800 putative genes (or ∼4%) of total genes in mammalian genomes. Consensus 5′ donor splice site (ATATCCTTT), branch site (TTCCTTRACYCY) and 5′ acceptor splice site (YAS) recognition sequences of minor U12-type spliceosome varies from conventional major U2-type spliceosome recognition sequences with consensus 5′ donor splice site (GTRAGT), branch site (YY-TRAY) and 5′ acceptor splice site (YYYYYYY-YAG). NALCN has a variable intron splice junction in this region, with resemblances to the major U2-type spliceosome recognition sequence. DNA sequences were aligned using MUSCLE 3.7 (Edgar, 2004) within EMBL-EBI web interface (Chojnacki et al., 2017).

A Common Asymmetrical 4 × 6 Tm Channel Structure is Shared Amongst Most Groups of Eukaryotes

Eukaryotic 4 × 6 TM channels adopted a particular asymmetrical, architecture followed domain duplication which generated the four domain channel. The signature, asymmetrical structure is common to all known cation channels including sodium, calcium and NALCN channels in animals, including Nav2, Cav1, and Cav3 homologs in the single cell choanoflagellate, S. rosetta, voltage-gated cation channels from other protists (e.g., dinoflagellates, ciliates, oomycetes, and diatoms), yeast calcium channel (e.g., Cch1p) (Locke et al., 2000), as well as species of brown and green algae (chlorophytes and prasinophytes) (Figure 7). Major eukaryotic groups lacking the 4 × 6 TM channel structure are the embryophytes (the land plants) and red algae (Verret et al., 2010). Ancestors to the land plants appeared to have purged the eukaryotic 4 × 6 TM channels, alongside key components of the animal toolkit for cation influx across the plasma membrane which includes the IP3 receptors, ATP-gated purinergic receptors, the cys-loop superfamily of ligand-gated ion channels and TRP channels (Edel et al., 2017). A single two-domain, TPC1 homolog is retained in land plants as it relates to comparable signaling across internal membrane compartments of plant vacuoles and animal organelles (Hedrich and Marten, 2011).

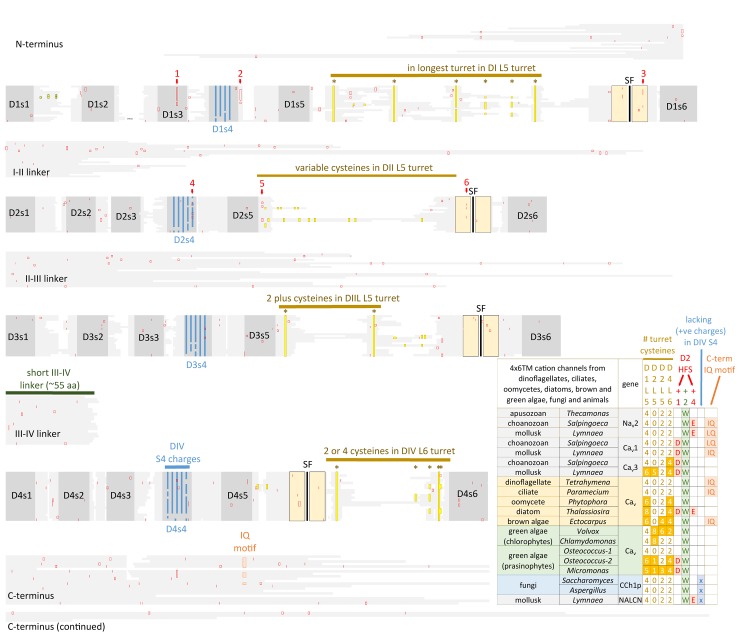

FIGURE 7.

Alignment of 4 × 6 TM cation channel representatives illustrating a shared fundamental architecture of asymmetrically arranged extracellular and intracellular regions from single cell protists (choanoflagellates, dinoflagellates, oomycetes, and ciliates), green algae (chlorophytes and prasinophytes), brown algae, yeast, and Nav2, Nav1, Cav1, Cav2, and Cav3 channels from protostome invertebrate (pond snail, L. stagnalis). A concerted evolutionary change to a common asymmetrical architecture of 4 × 6 TM cation channels contrasts with the pseudo-symmetry of cyclic nucleotide-gated potassium channel (CNGK) channels which contain four nearly identical domains chained together. Long extensive extracellular turrets prior to the pore selectivity filter (SF) include L51, L5III and more rarely L5II and a longer turret after the SF in L6IV, as well as a 4-0-2-2 framework of core cysteines populating L5I-L5II-L5III-L6IV extracellular turrets in 4 × 6 TM channels. L5IV extracellular turret is always short in 4 × 6 TM channels. The cytoplasmic III-IV linkers are always short (∼53–57 amino acids) compared in contrast to more variable I-II linker, II-III linkers, and N- and C-termini in 4 × 6 TM cation channels. Intron splice sites are indicated by red vertical lines. Dinoflagellate, ciliate, oomycete, diatom, green and brown algae channels illustrated in the figure all possess a conserved HFS site resembling an animal calcium channel (EEEE). Notably lacking in most of these protist channels is the conservation in the pore selectivity filter of Domain II of a “calcium beacon” aspartate (D) (HFS+1) omni-present in animal calcium channels, or a “sodium beacon” glutamate (HFS+4) omni-present in animal sodium channels, and a C-terminal IQ motif. A tryptophan ring at HFS+2 is present in all four domains of all channels except Domain I of Cch1p. A notable absence of S4 charges is found for yeast Cch1p and NALCN. Amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE 3.7 (Edgar, 2004) within EMBL-EBI web interface (Chojnacki et al., 2017).

Organization of Pore and Voltage Sensor Domains in four Domain Cation Channels

Generation of the four pores and voltage-sensor domains after domain duplication, provided opportunity for divergence and specialization of the four individual domains of 4 × 6 TM channels. This is evident in studies assessing the relative contribution of voltage-sensor domains in Nav1 channels for example, where the first three of four domains appear to be faster in gating charge movement, and are necessary and sufficient to regulate channel opening, while the fourth domain is slower to mobilize and contributes more to the refractory, inactivated state of the channel after prolonged channel opening (Capes et al., 2013).

Associated structural changes for the coordinated movements of individual domains for channel gating include a unique “domain swapping” topology found in 1x6TM (Doyle et al., 1998; Payandeh et al., 2011) and 4 × 6 TM (Wu et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2017) voltage-gated cation channels, where voltage sensor modules are rotated clockwise with respect to pore modules of each domain. The voltage sensor module of Domain I, for instance, surrounds the Domain II pore. The domain swapping arrangement is lacking in many potassium channel classes [e.g., Eag1 (Whicher and MacKinnon, 2016), CNG (Li et al., 2017), HCN (Lee and MacKinnon, 2017) Slo1 (Tao et al., 2017) and Slo2.2 (Hite and MacKinnon, 2017)], and lacking in some TRP channels like TRPV6 while present in other TRP channels (e.g., TRPV1 and TRPV2) (Singh et al., 2017). The absence of a domain swapping topology correlates with an S4-S5 linker that is too short to accommodate the swapping of voltage-sensor and pore domains. The longer S4-S5 linkers supports a rotary coupling of interlocked pore domains for more concerted actions in gated pore movements within voltage-gated cation channels (Bagneris et al., 2015).

Conservation of Positioning of Cysteines and Patterns of Extracellular Turret Sizes Within Eukaryotic 4 × 6 Tm Channels

There is a specific asymmetrical pattern of long (15–105 aa) extracellular turrets shared in the pore domains of all animal calcium, sodium and NALCN channels, and more broadly with most eukaryotic lifeforms (outside of land plants and red algae), including yeast, ciliates, dinoflagellates, oomycetes, diatoms and brown and green (chorophytes and prasinophytes) algae (Figures 2, 7). Bacterial sodium and potassium channels possess extracellular L5 and L6 turrets that are always short (10–15 aa) in length (Stephens et al., 2015; Figures 2, 7). 4 × 6 TM channels possess a rising extracellular turret from the S5 transmembrane helix (dubbed L5) before the pore selectivity filter, and a second shorter extracellular turret after the pore before S6 transmembrane helix (dubbed L6) (Figures 2, 3C,D, 7; Stephens et al., 2015). The longest L5 extracellular turret is in Domain I (ranging from 60 to 105 aa). L5 in Domain III possess the second longest turret (ranging from 40 to 60 aa), while Domain II and IV turrets are the shortest L5 extracellular turrets (15–30 aa) in size. The longest and most variable L6 extracellular turret amongst 4 × 6 TM channels is contained in Domain IV, with L6 extracellular turrets being shorter and less variable in Domains I, II and III. Populated within the four turret domains is a fundamental set of eight conserved cysteines that are present in all 4x6 TM channels: two in L5I, two in L5III and two in L6IV (Figure 7; Stephens et al., 2015). The extended extracellular turrets appear to form intra-loop disulphide bonds which stabilize the structure as a “windowed dome” of interlocked extracellular loops in the human Cav1.1 calcium channel (Figure 3C; Wu et al., 2016) or electric eel Nav1.4 sodium channel complex (Figure 3D; Yan et al., 2017), resolved in the cryo- electron microscopy of channel protein nanoparticles. L5 turrets of Domains I, II and III (i.e., L5I, L5II, and L5III) as well as L5 and L6 turrets of Domains III and IV, respectively, form highly negatively charged vestibules above the pore selectivity filter that serves as an electro-attractant for cation passage before reaching the selectivity filter below (Figures 3D,E). The eight conserved cysteines in extracellular turrets appear to be necessary for proper folding of 4 × 6 TM channels, as mutations of these conserved cysteines prevents their ion channel expression (Karmazinova et al., 2010). Varying from this conserved set of 8 extracellular turret cysteines in 4 × 6 TM channels are additional 1 to 3 cysteines in L5II of Nav1 channels in vertebrates only (Stephens et al., 2015). Cav3 T-type channels, but not Cav1 or Cav2 channels, possess extra cysteines – more than double the number beyond the core 8 cysteines in L5I (+2), L5II (from 0 to +5), L5IV (+2), L6IV (0 to +2), and S1-S2 in Domain I (+3) (Senatore et al., 2014). The positioning of numbers of cysteines and size of L5II and L6IV turrets is exploited to generate a variable ion selectivity from calcium to highly sodium selectivity, available in most invertebrates Cav3 (T-type) channels by alternative splicing (Senatore et al., 2014).

A Ubiquity in the Sugar Coating of the Extracellular Surface of Voltage-Gated Cation Channels at Glycosylated Amino Acid Residues

The external surface of voltage-gated channels are coated with (glycans) sugar groups, by an enzymatic, co- and post-translational process fundamentally critical for the proper folding and functional expression of voltage-gated ion channels (Baycin-Hizal et al., 2014). N-linked glycosylation involves sugars attached to the nitrogen atom of an asparagine amino-acid side chains (Mellquist et al., 1998) and is the most common form of glycosylation (Apweiler et al., 1999). O-linked glycosylation has a more promiscuous consensus binding site to different possible oxygen atoms of nascent proteins (Van den Steen et al., 1998), but has been reported for Nav1 channels (Ednie et al., 2015).

Glycosylation sites are enriched in the vicinity of the conserved cysteines on the longest L5I and second longest L5III extracellular loops of 4 × 6 TM voltage-gated cation channels. Electron microscopy structures of frozen sodium channel nano-particles resolves 20 and 16 sugars, incorporated into seven glycosylation sites on insect Nav1 (Shen et al., 2017) and electric eel Nav1.4 (Yan et al., 2017) sodium channels, with four and three glycosylation sites contained in L5I and L5III extracellular loops, respectively. While there are a conserved positioning of cysteines in extracellular loops, putative locations of glycosylation sites are not fundamentally shared between sodium and calcium channel families. Individual sodium (Nav2/Nav1), calcium channel (Cav1/Cav2) or T-type (Cav3) channel genes can highly vary in their density of glycosylation sites. An often cited example of enrichment is in mammalian Nav1.4 sodium channel, which possesses four extra glycosylation site harbored in a unique ∼36 amino acid fragment added to the L5I extracellular loop compared to non-mammalian, but vertebrate (e.g., eel) Nav1.4 (Bennett, 2002). Each sugar moiety contains a terminal sialic acid in N-glycosylation sites, contributing to the total electro-negativity of channel surface charge, with consequences to channel gating in biasing the voltage sensors by surface charge screening (Ednie and Bennett, 2012). The high electro-negativity due to glycosylation appears to reaches a saturation in mammalian Nav1.4, so that additional sialic acids contributed by the two known glycosylation sites of co-expressed mammalian beta subunit (Navβ1, 25 kDa), influence channel gating on the more weakly glycosylated mammalian sodium channels (Nav1.2, Nav1.5, and Nav1.7) but not on channel gating of the heavily, saturated Nav1.4 channel with glycosylation sites (Johnson et al., 2004). The longest extracellular loops (L5I and L5III) of the pore-forming α1 subunit (∼170 kDa) of Cav1 and Cav2 channels are preoccupied in cradling a large, mostly extracellular α2 subunit (∼150 kDa) (Leung et al., 1987). Almost all of the glycosylation sites (15 out of 16) in the resolved structure of the mammalian Cav1.1 channel complex are associated with the α2 subunit, with a single glycosylation site contained in L5I extracellular loop of the pore forming α1 subunit of Cav1.1 (Wu et al., 2016). Cav3 T-type channels resemble Nav sodium channels in lacking association with a large accessory subunit, and appear to possess more secondary structure with greater potential variations for glycosylation in their longer (L5I and L5III) as well as L6IV extracellular loops like the Nav channels (Lazniewska and Weiss, 2017).

The High Field Strength (Hfs) Site of the Pore Selectivity Filter Define the Sodium or Calcium Ion Selectivity in Eukaryotic Voltage-Gated Channels

A critical feature that emerges from the structural asymmetry in eukaryotic 4 × 6 TM channels is a highly changeable ion selectivity that ranges from highly calcium-selective channels (like Cav1/Cav2 channels) and highly sodium-selective channels (like Nav1 channels). The 4 × 6 TM calcium and sodium channels are at least a thousand-fold and ten-fold more selective for their particular cation, respectively, amongst competing native cations (e.g., Ca2+, Na+, and K+) (Hille, 1972; Hille, 2001; Finol-Urdaneta et al., 2014). The high calcium or sodium selectivity is largely converted by a singular, determinative residue at the most constricted point of the funnel-like pore known as the HFS site of the pore selectivity filter (Heinemann et al., 1992; Schlief et al., 1996). The HFS site is a negatively charged carboxylate, derived from a glutamate residue in the bacterial sodium channel pore of NavAb of TLESWSM (Yue et al., 2002). The equivalent HFS site in eukaryotic calcium-selective channels is contributed by different amino acids from Domains I, II, III and IV, forming a ring of electronegative, glutamate residues configured as “EEEE” in Cav1 and Cav2 channels (Figure 8). The HFS site of sodium-selective channels are always differentiated with a positively charged lysine (K) residue configured in the third domain as “DEKA” in most Nav1 channels (Noda et al., 1984).

FIGURE 8.

Illustration of the distribution of HFS site sequences in NALCN, sodium channels (Nav2 and Nav1) and calcium channels (Cav1, Cav2, and Cav3) in different animals groups, as well as single cell eukaryotes Thecamonas (apusozoan) and Salpingoeca (choanoflagellate) (Top panel). Illustrations of animals (images imported from Wikipedia) lacking Nav1 channel genes (Bottom panel). Lifeforms with calcium-selective pores (shaded orange color) include HFS site sequences mostly of negatively charged glutamate (E) or aspartate (D) residues: DEEA, DEES, DEEG, DEET, EEEE, EDEE, NEEE, while sodium-selective pores (shaded blue color) have a lysine (K) residue in Domains II (EKEE and DKEA) or a lysine residue in Domain III (EEKE, DEKA, and DEKG). Cav3 T-type calcium channels have a selectivity filter of EEDD and may be calcium or non-selective channels (shaded orange color), with high sodium selectivity engendered in invertebrate Cav3 channels by alternative splicing of exon 12a coding for a novel L5II turret (shaded blue color). Greater sodium selectivity also involves a D4L6i extracellular turret found in invertebrates instead of the D4L6v turret found in cnidarians and vertebrates. Numbers in brackets next to the gene indicate the number of gene isoforms (2, 3, 4, 5, or 10) that have been identified in a species, outside of one. An () indicates loss of gene in the indicated species. Amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE 3.7 (Edgar, 2004) within EMBL-EBI web interface (Chojnacki et al., 2017).

Native bacterial channels are not known to possess calcium-selective channels, but such a channel can be artificially created by engineering symmetrical rings of negatively charged carboxylates from aspartates (TLDDWSD from TLESWSM) at twelve amino acid positions in the pore, spanning the HFS site glutamate residue, and downstream amino acids dubbed “Ca”, (position +1) and “Na”, (position +4). (NavAb mutant, Figure 4; Tang et al., 2014). The “Ca” and “Na” positions contribute to the outermost vestibule of the re-entrant pore selectivity filter, where they appear to be engineered to serve as potential “beacons” for attracting “Ca” or “Na” ions to the eukaryotic pore.

The Uniquely Asymmetrical Pore Selectivity Filter Define the Sodium Ion Selectivity in Eukaryotic Voltage-Gated Channels

Molecular dynamics modeling illustrate how sodium selectivity is conserved in eukaryotic 4 × 6 TM channels involving four key amino acid residues (Zhang et al., 2018). The “Na beacon” position in Domain II (HFS+4) is always a glutamate residue (E) in known Nav2 and Nav1 channels, where it is optimally positioned in the outer vestibule to attract incoming cations (Zhang et al., 2018). The “Na beacon” relays incoming cations to the aspartate residue (DEKA) of the HFS in Domain I and then to the glutamate residue (DEKA) of the HFS site of Domain II, in a set of likely side-chain swinging transitions between these three negatively charged carboxylate residues in the pore selectivity filter (Zhang et al., 2018). The omnipresent, positively charged lysine residue of Nav1 channels of the HFS site (DEKA) protrudes into the spacious central cavity, repulsing the positive cations to the opposite side wall of the pore, where the ions are funneled, sequentially to the negatively charged (D and E) side chains of the HFS site (DEKA and DEKA) of the pore selectivity filter (Zhang et al., 2018). A critical structural deviation only found in Nav2 and Nav1 channels is a shortening of the selectivity filter in the second domain (Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2012), bringing the “Na beacon” residue in closer proximity to the other carboxylate site chains of the HFS site (D and E) residues required for coordination and selective passage of Na+ ions through the Nav1 channel pore (Shen et al., 2017). Homologous positioning of the pore selectivity filters and the Na site of 4 × 6 TM sodium channels are not easy to translate into sequence alignments with calcium channels or bacterial sodium channels. A single gap in amino acid sequence is inserted into multiple sequence alignments to convey this discrepancy for the 4 × 6 TM sodium channel pores (see Figure 4; Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2018).

Known variations in the HFS site of the pore selectivity filter of Nav1 channels including substitution of the 4th position from alanine (DEKA) to glycine (DEKG) identified in flatworm Nav1 channels (Jeziorski et al., 1997) and many alternative isoforms of duplicated Nav1 genes in teleost fish (Jost et al., 2008). The 4th position of the HFS site is not involved in coordinating ion selectivity, as predicted by modeling (Shen et al., 2017) and experimental evidence (Wu et al., 2013). The HFS lysine residue is relocated from Domain III (DEKA) in most metazoans to Domain II (DKEA) in cnidarians. The HFS site variation likely reflects a mirror imaging of selectivity filters swapped between Domain III and Domain II in cnidarian Nav1 channels without major consequences to their sodium selectivity (Spafford et al., 1998; Figure 8). Indeed, native sodium currents in cnidarians highly resemble mammalian Nav1 currents with a similar profile of ion selectivity for monovalent and divalent ions, suggesting that the cnidarian pore containing a DKEA HFS likely confers a similarly high sodium selectivity as the DEKA configuration of vertebrate Nav1 channels (Grigoriev et al., 1996; Spafford et al., 1996). The molecular constituents necessary for these channels to generate a high sodium selectivity hasn’t been assessed in cnidarian Nav1 channels, because these channels do not generate expressible ion currents in vitro, like other non-pancrustacean, invertebrate Nav1 channels (Schlief et al., 1996; Gur Barzilai et al., 2012).

The replacement of a positively charged lysine residue in the HFS site of Domain II or III with a negatively charged glutamate residue as DEEA differentiate the Nav2 channels, which are always lacking in sodium ion selectivity (Zhou et al., 2004). Nav2 channels otherwise closely resemble the Nav1 channels in structure and are distributed in genomes from single cell eukaryotes and multicellular animals including vertebrates, but not including ray-finned fish or tetrapods, like mammals (Zakon et al., 2017; Figure 8). Molecular modeling suggest a much wider and accommodating “DEEA” pore for Na+, K+, and Ca2+ ions in the absence of a protruding positively charged lysine residue, funneling ions to the side wall containing the carboxylate (D and E) side chains of the HFS site in Nav2 channels (Shen et al., 2017). Substitution of small amino acids (glycine, DEEG; serine, DEES; threonine, DEET) for the alanine in the 4th position of the “DEEA” HFS site occurs in Nav2 channels (Moran et al., 2015) in a homologous position as Nav1 channel substitutions in the 4th position of the HFS site. The omni-presence of the “Na beacon” in Domain II and the first and second position of “DE” within the HFS, reflects a common mode of ion selectivity for Nav2 and Nav1 channels, outside the uniquely protruding, positively charged lysine residue in the HFS site, which is required for limiting ion selectivity to sodium ions for Nav1 channels.

A More Symmetrical Pore Selectivity Filter is Present in Calcium-Selective, Voltage-Gated Channels

A uniquely, more symmetrical, pore selectivity filter is shared amongst calcium channels, compared to 4 × 6 TM sodium channels. An aspartate (D) residue is ubiquitously located in the “Ca” position (HFS+1) of calcium channels (Cav1, Cav2, and Cav3) (Figure 8) and dubbed a “Ca beacon” for its position just above the HFS site, in an opportune position to attract incoming calcium ions to the pore selectivity filter below (Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2011). The “Ca beacon” is located in the vicinity of the outer pore of Domain II as the “Na beacon” of sodium channels (Figure 4; Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2011). 4 × 6 TM calcium channels vary from 4 × 6 TM sodium channels in possess a pseudo-symmetry of their pore selectivity filters, more resembling the four-fold symmetry of bacterial 1 × 6 TM sodium channels. Calcium channels lack the shortened pore selectivity filter for Domain II found in sodium channels, and bear a more symmetrical, electro-negative ring of glutamate residues in the HFS site, configured as “EEEE” in Cav1 and Cav2 channels (Figure 8). The only known deviation of the “EEEE” configuration of the HFS site is the basal Cav1 homolog isolated from S. rosetta, which retains a high calcium selective, even though the carboxylate side chain in Domain II is shortened by one carbon chain as “EDEE” (Mehta, 2016).

Orphan Gene Nalcn Possesses Pore Selectivity Filters That Resemble Calcium and Sodium Channels

NALCN channels are usually a single representative in most animal groups, and possess variable HFS sites that resemble calcium channels “EEEE” (or rarely “EDEE”) or can resemble Nav1 sodium channels with a positively charged lysine (K) residue in Domain II or Domain III as EKEE or EEKE, respectively (Figure 8; Senatore et al., 2013). Many invertebrates groups possess a flexibility in generating alternative pores which resemble calcium- or sodium-selective NALCN channels specialized for different tissues (Senatore et al., 2013). A duplication of Exon 15 coding for region spanning the selectivity filter residue in Domain II of NALCN creates alternative calcium-selective (EEEE) and sodium-selective (EKEE) pores in the Platyhelminthes (flatworms) and protostomes of the lophotrochozoan lineage (mollusks and annelids), and non-chordate deuterostomes (echinoderms and hemichordates) (Figure 8; Senatore et al., 2013). A separate duplication event in Exon 31 of the Ecdysozoan lineage creates different alternative calcium-selective (EEEE) and sodium-selective (EEKE) NALCN pores that are retained in myriapods (includes centipedes, millipedes) and chelicerates (includes Arachnids like mites and ticks) (Figure 8; Senatore et al., 2013). NALCN channels are well described as a cation leak conductance that play roles in generating rhythmic behaviors in invertebrates and vertebrates (Cochet-Bissuel et al., 2014), while also highly curious channels in retaining both calcium selective and sodium selective pore structures in many non-vertebrates (Senatore et al., 2013).

Cav3 T-Type Channels have a Calcium-Like Pore Selectivity Filter That Can Generate High Calcium or Sodium Selectivity by Alternative Extracellular Loops Coding for L5Ii and L6Iv

Cav3 T-type channels have a HFS site in the selectivity filter that resembles calcium channels (EEEE), but notably different, and universally EEDD, shortened in carbon chains of the carboxylate side chain residues (glutamate (E) to aspartate (D) in Domains III and IV) compared to Cav1 and Cav2 channels (Perez-Reyes et al., 1998). The most calcium-selective, Cav3 T-type channel, Cav3.1, is more sodium permeable (∼1 Na+ per 5 Ca2+) (Shcheglovitov et al., 2007; Senatore et al., 2014) than Cav1 and Cav2 calcium channels (∼1 Na+ per 1,000 Ca2+), suggesting that the HFS site of EEDD and other contributing pore selectivity filter residues, support a less calcium selective pore in Cav3 T-type channels. Invertebrates generate a high sodium selectivity in their Cav3 T-type channels resembling Nav1 channels through alternative splicing of a novel cysteine-enriched L5II extracellular turret coded in exon 12 (Senatore et al., 2014).

Summary of Configurations of HFS Sites That Generate Sodium or Calcium Selective Pores

Nav, Cav and NALCN channels possess a universal set of HFS site configurations with calcium- or non-selective pores with electronegative residues in Domains II and III (EEEE, EDEE, EEDD, DEEA, DEES, DEEG, and DEET) and sodium-selective pores with a lysine in Domains II (DKEA, DKEG, and EKEE) or Domain III (DEKA and EEKE). More variable HFS pores are found in the 4 × 6 TM representatives outside of the animal/fungi supergroup of Unikonts (lifeforms with one flagella), such as diatoms, brown algae, oomycetes, cilates and dinoflagellates, and within branches of the Bikonts (lifeforms with two flagella), such as the green algae (chlorophytes and prasinophytes) (Verret et al., 2010). Approximately half of these non-animal representatives possess a HFS site resembling a calcium-selective pore (NEEE, EEEE, DDDD, and EEDE) (e.g., see representatives in Figure 7) and the rest of the pores are characterized by a pattern that represents experimentation and divergence. These pores may resemble a sodium-selective channel DDKD or possess HFS sites that are unlike any animal representative (e.g., RSDD, RADD, SESE, TDEE, and TEND) (Verret et al., 2010).

Importance of Specific Asymmetrically Arranged Residues in the Selectivity Filter for Pore Binding Ttx Binding

The outermost position “Na” (HFS site +4) is populated to form a negative-charged ring in the uppermost pore in many of the pore domains of eukaryotic sodium and calcium channels (Shen et al., 2018; Figure 4). The negatively charged aspartate (D) of the “Na” site in Domain IV is a frequently altered residue in animals adapted for resistance to pore-blocking, Nav1 channel toxin tetrodotoxin (TTX) (see TTX insensitive Nav1.4, Figure 4; Feldman et al., 2012). TTX is a bacterial toxin produced commonly by Vibrio alginolyticus which exists symbiotically within many discovered hosts, including notably pufferfish and many other fish species, tubellarian flatworms, blue-ringed octopus, western newt, toads, sea stars, angelfish, polyclad flatworms, Chaetognath arrow worms, nemertean ribbon worms and xanthid horseshoe crabs (Chau et al., 2011). A striking example of adaptation in the sodium channel pore is illustrated in the TTX-resistance of garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis) in districts where toxic prey newts (Taricha granulosa) are present, but not in the same species of garter snake in neighboring districts where these newts are absent (Geffeney et al., 2005). Similar residue changes in the “Na” position also provides for resistance to the analog saxitoxin (STX), contributing to the paralytic shellfish toxin, produced in toxic algal blooms in marine environments (Terlau et al., 1991). The many marine invertebrates that are completely resistant to TTX or STX, can comes at a cost of a lowered sodium ion selectivity in their Nav1 sodium channels (Grigoriev et al., 1996). TTX is a primary tool for the discrimination of Nav1 channels currents in doses ranging from the nanomolar to micromolar concentrations (Toledo et al., 2016). Nonetheless, the outer pore-blocking mechanism of TTX or STX or the micro-conotoxins (μ-CTXs) from venomous cone snails, is more the exception than the rule to how animal toxins regulate Nav1 channels. The vast majority of animal toxins are gating modifiers which take advantage of the greater structural variance outside of the outer pore of different Nav1 channels (Kalia et al., 2015). Another form of blockade are the frequency-, use- or state-dependent drugs that inhabit the aqueous vestibule within the channel pore, at higher affinities in particular channel states, such as when the inactivation gate is closed (Hille, 2001). Nav1 channels possess a much smaller aqueous vestibule within the pore for harboring drugs (e.g., local anesthetics like lidocaine) (Shen et al., 2017) compared to Cav1 channels which possess a more accommodating pocket within the pore for harboring drugs (e.g., nifedipine, verapamil, diltiazem) (Wu et al., 2016). Both the bacterial Nav channels and eukaryotic Nav and Cav channels possess side-portals or “fenestrations” between domains, providing an access pathway of small hydrophobic drugs to the inside of the pore without required passage through the pore selectivity filter during channel pore opening (Catterall and Swanson, 2015).

Origin of Nav2 Channels in Single Cell Eukaryotes

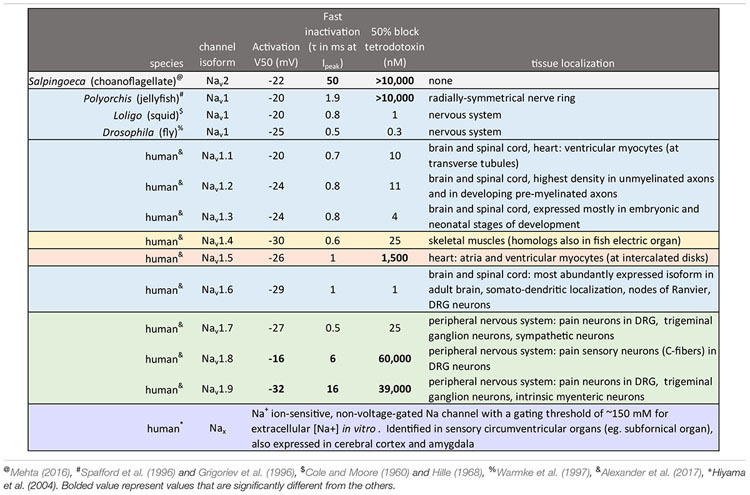

Single cell eukaryotes, like diatoms generate an animal-like, rapid action potential spike of a few ms in length from a resting membrane potential of ∼-68 mV (Taylor, 2009). The action potential in diatoms is generated with a fast inward current carried by sodium and calcium ions, peaking at -∼ 20 mV, and recovering quickly from inactivation (τ = ∼7 ms) (Taylor, 2009). While diatoms functionally generate an animal-like sodium and calcium current (Figure 9A), structurally it can only be derived from a 1x6TM bacterial sodium channel gene or a 4 × 6 TM template with an architecture distantly resembling calcium channels from animals (Verret et al., 2010; Figure 7). The diatoms belong to the Heterokonts (multiple different shaped flagella), which are separate from the Unikonts (single or no flagella), which are the lineage which includes the animals. The most basal extant representative of a recognizable homolog to animal genes is a 4 × 6 TM Nav2 homolog found in an apusozoan, represented by Thecamonas trahens (Figures 1, 8; Cai, 2012). Apusozoans are Unikonts that lies outside the Opisthokonts (bearing a posterior flagella) that includes the choanoflagellates, animals and fungi (Cavalier-Smith and Chao, 2010). Choanoflagellates (posterior flagella; possessing ciliated collars like sponge choanocytes) are closer relatives to the animals and fungi than the apusozoans. Choanoflagellates are represented by S. rosetta which possess a Nav2 homolog, SroNav2 (Mehta, 2016), but also have expressible homologs for Cav1 and Cav3 channels too (Figure 1). Expression of SroNav2 channel from this extant representative of an earliest branching single-celled organism, reveals a non-selective ion channel, equally passing Na+, K+, or Ca2+ ions, and also possesses extremely slow gating kinetics (Figure 9A; Mehta, 2016). Gating of a typical sodium channel from the classical squid giant axon is akin to mammalian neurons is rapid, enabling action potential spikes of 1–2 ms in length (Figure 9A; Hodgkin and Huxley, 1952). SroNav2 is more than tenfold slower, taking more than 10 ms to fully activate, with a slow inactivation decay (τ of >50 ms), requiring ∼ more than 1/2 s to completely inactivate, and ∼12 s to fully recover from inactivation in a whole cell patch clamp recording of currents recorded in HEK293T cell lines (Mehta, 2016).

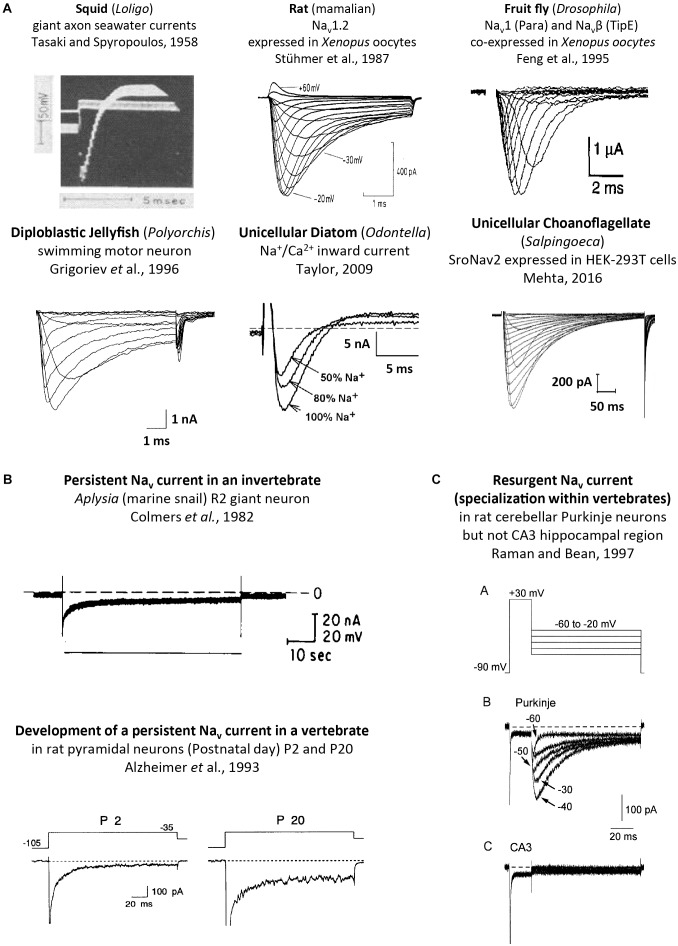

FIGURE 9.

Sodium ion containing currents recorded in voltage-clamp studies of cells or expressed genes derived from single cell eukaryotes, invertebrates and vertebrates. (A) Squid, rat, fruit fly, jellyfish, diatom and choanoflagellates, reproduced with permission from Tasaki and Spyropoulos (1958), Stühmer et al. (1987), Feng et al. (1995), Grigoriev et al. (1996), Taylor (2009), Mehta (2016). (B) Persistent sodium currents in both invertebrates (top panel) and vertebrate neurons (bottom panel), reproduced with permission from Colmers et al. (1982) and Alzheimer et al. (1993), respectively. (C) Resurgent sodium currents, a property associated only with particular vertebrate neurons, reproduced with permission from Raman and Bean (1997).

Nav2 Channels have Functions Associated With Olfactory Sensing in Invertebrates

Nav2 homologs have also been recorded from arthropods such as cockroach (Zhou et al., 2004), honeybee (Gosselin-Badaroudine et al., 2016) and fruit fly (Zhang et al., 2011) as well as sea anemone (a cnidarian) (Gur Barzilai et al., 2012), the latter of which has four Nav2 channel homologs. Single Nav2 channel homologs have been identified in vertebrates species, including cartilaginous fish (Australian ghostshark), lobed-finned fish (coelacanth), and jawless fish (lampreys) (Zakon et al., 2017). All expressed Nav2 homologs possess slow gating kinetics, and are non-selective channels passing calcium and sodium ions (Gosselin-Badaroudine et al., 2016). The Nav2 channel from honeybee is unique in generating mostly a calcium current, contributed by a smaller-sized sodium current (Gosselin-Badaroudine et al., 2016). The honeybee Nav2 channel may be mostly a calcium current but does not possess the nearly exclusive (1,000:1) calcium over sodium ion selectivity characteristic of Cav1 or Cav2 calcium channels (Hille, 2001).

Nav2 channels are represented from single cell choanoflagellates to vertebrates mostly as a single gene, but it is not a required gene in every species. Nav2 channel genes appear to be completely lacking in yeast, flatworms, nematodes, chelicerates (within the arthropods) and clitellates (within the annelids), and also lacking in many vertebrates, including ray-finned fishes and tetropods, including mammals (Figure 8). The absence of either sodium (Nav2 and Nav1) channel genes in different animal species is in contrast with calcium channels (Cav1, Cav2, and Cav3) which are omni-present, and not known to be secondarily lost in any animal group.

A possible function associated with Nav2 channels has been inferred from gene knockdowns in fruit fly (Drosophila), which possess a diminished ability to smell (Kulkarni et al., 2002), and a hyperkinetic mobility that is intensified by heat shock and starvation (Zhang et al., 2013). Nav2 channels have increased in gene number beyond a single homolog in urochordates such as Ciona intestinalis (two genes) ctenophores, sponges and placozoans (two genes), and as many as four genes in anthozoan or scyphozoan cnidarians (Figure 8). The diversification of Nav2 channels particularly within animals lacking true nervous systems (ctenophores, sponges and placozoans) or possessing vestigial nervous systems (tunicates), is suggestive of an expansion of roles for Nav2 filling of niches in the absence of animals with a mature nervous system. All vertebrate Nav2 channels identified in non-teleost fish, for example are only expressed outside of the nervous system (Zakon et al., 2017).

Requirements for Nervous Systems was the Impetus for the Appearance and Retention of Nav1 Channels in Eu-Metazoans

Unicellular organisms (yeast, protozoans) and the earliest diverging multicellular animals, such as ctenophores (comb jellies), sponges and placozoans (Trichoplax adhaerens) lack Nav1 channels (Figure 8). These early branching lifeforms such as sponges (Leys, 2015) or placozoans (Senatore et al., 2017) have a “toolkit” of many of the building blocks for nervous systems, without possessing eu-metazoan nervous tissue. Ctenophores have a nervous system, but are lacking most of the classical transmitter receptors and ion channels, and other neuronal elements common to the eu-metazoan nervous system template (Moroz and Kohn, 2016). Inward currents generating membrane excitability containing calcium ions as a charge carrier is limited because of competing roles of calcium ions as an exquisitely sensitive intracellular messenger. Calcium ions are toxic to cells when levels rise too high and calcium ions have a propensity to precipitate with phosphate (as bone matrix) (Hille, 2001). Free concentrations of intracellular calcium is necessarily kept at very low (nM) within cells by intracellular calcium buffering, compartmental storage of calcium in intracellular organelles, and extrusion to the cell exterior (Hille, 2001). Sodium ions are relatively inert, maintained at high (mM) concentrations within cells, and serves as a major ion in generating osmotic pressure (Hille, 2001) and as a workhorse in the secondary active transport of hydrogen ions or amino acids (Hille, 2001). A key step in the appearance of nervous systems, was the amino acid changes in the HFS site and surrounding residues, allowing for the sodium-selectivity of Nav1 channels, and an ability to exploit the steep, calcium ion free electro-chemical gradient, for generating rapid, mostly inert, action potential spikes along nervous tissue.

Singleton Nav1 Channels in Invertebrate Species are Functionally Limited to Nervous Systems

The cnidarians are the simplest eu-metazoans with Nav1 channel genes and they also are the simplest organism to possess a true nervous systems (Spafford et al., 1998). Cnidarians have a simple body plan of two germ layers (diploblastic), are lacking a coelom, and are radially symmetrical animals without cephalization (a brain localized in the anterior position) (Zapata et al., 2015). The Nav1 sodium channels in these basal species possess motor neurons which regulate the pulsating contractions of the jellyfish bell during swimming, are almost indistinguishable from those of the giant axons of the Atlantic squid or frog sciatic nerve, in their rapid millisecond gating and high sodium selectivity (Grigoriev et al., 1996). Sodium-selective Nav1 channels remain as a singleton gene in most invertebrates with functional currents limited in detection to nervous tissue, and lacking in functional protein expression in heart muscle or striated (skeletal-like) muscle or glands. mRNA coding for invertebrate Nav1 channels can be detected outside the nervous system, e.g., (Hong and Ganetzky, 1994; Gosselin-Badaroudine et al., 2015), but sodium currents have never been resolved outside the nervous system in known protostome invertebrates from the diverse lophotrochozoans to the ecdysozoans, e.g., (Hagiwara et al., 1964; Mounier and Vassort, 1975; Salkoff and Wyman, 1983; Brezina et al., 1994; Collet and Belzunces, 2007; Senatore et al., 2014). The primary expression of Nav1 sodium channel, “para” is in insect nervous systems, where Drosophila flies with Para locus mutations exhibit a temperature-sensitive paralyzes from nerve conduction blockade (Loughney et al., 1989). A niche left from a lack of Nav1 sodium channels outside of the nervous system can be filled with a sodium-selective Cav3 T-type channel isoform, generated by the unique alternative splicing in the extracellular turret upstream of the Domain II pore in most invertebrates (Senatore et al., 2014). Presence of an alternative 12a exon engenders Cav3 T-type channels with sodium selectivity (Figure 8), and is the only splice isoform found in the molluscan heart. The exon 12a containing T-type sodium channel isoform is almost ubiquitously present isoform in all eu-metazoans with organ-containing body cavities (coelomates), including some flatworms (pseudocoelomates) (Senatore et al., 2014).

Vertebrates underwent an expansion of Nav1 channel gene numbers to ten alongside the dramatic changes in body plan that include a greater sophistication of tissues, with different Nav1.x isoforms expressed at high density in particular tissues such as brain (e.g., Nav1.6), heart (e.g., Nav1.5) and skeletal muscle (Nav1.4) (Zakon et al., 2017).

Nav1 Channels are Lost in Many Invertebrate Groups, Compared to an Apparent Ubiquity in the Retention of Nalcn and Calcium Channel Genes

A loss of Nav1 sodium channel genes is also common in non-vertebrate animals. For example, Nav1 sodium channels are present in free living flatworms (e.g., Schmidtea mediterranea) but are lacking in parasitic flatworms (Schistosoma). Nav1 channels are also lacking in nematodes, approximately half of animals in this phyla which are parasitic (Zhang, 2013; Figure 8). Nematodes lack both Nav2 and Nav1 channels, and possess simple, vestigial nervous systems that may related to their often obligate parasitism of host species (Zhang, 2013; Figure 8). All-or-none action potentials of body wall muscles requires inward Na+ influx in nematodes (Liu et al., 2011), but it is likely derived from other sources such as sodium-selective Cav3 T-type channels, in lieu of Nav2 and Nav1 channels (Senatore et al., 2014). Deuterostomes such as the echinoderms (e.g., Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) and their relatives the hemichordates (e.g., Saccoglossus kowalevskii) have sparse, radially symmetrical nervous systems and also lack Nav1 channel genes (Figure 8). In comparison, genes coding for all three calcium channels (Cav1, Cav2, Cav3) and NALCN is present in every known extant, eu-metazoan to date (Senatore et al., 2016), while the rise and fall of Nav1 channel genes (from zero to ten) appears to relate to a species’ necessity for sodium dependent action potentials, a vital feature of metazoan nervous systems (Figure 8).

Nav2 Channels Differ from Nav1 Channels in Lacking Elements for Sodium Ion Selectivity and Fast Gating

The heritage of the first Nav1 channels emerging from Nav2 channel common ancestors is evident in the shared genomic structures of Nav1 and Nav2 channel genes. 20 intron splice sites are homologously shared in Nav1 and Nav2 channels, and these are all the intron splice sites spanning the conserved pore and voltage sensor domains (Figure 10). The same conservation of intron splice sites is paralleled within the calcium channel family, where Cav1 and Cav2 channels possess 31 shared intron splice sites. Both the Nav1 and Cav2 channels emerged from primordial Nav2 and Cav1 channel ancestors under a selection pressure for the evolution of specialized nervous tissue. Emergent roles of Nav1 and Cav2 channels appeared for fast conduction along nerve axons, and secretion of neurotransmitters between nerve synapses, respectively. The pairs of ion channel homologs in the most basal extant organisms known including Nav2/Nav1 in cnidarians (Gur Barzilai et al., 2012), or Cav1/Cav2 channels in placozoan, Trichoplax adhaerens (Senatore et al., 2016), are not easily distinguished from each other, as one would expect in extant organisms which are phylogenetically closer to the common ancestor containing the first Nav1 channels or Cav2 channels.

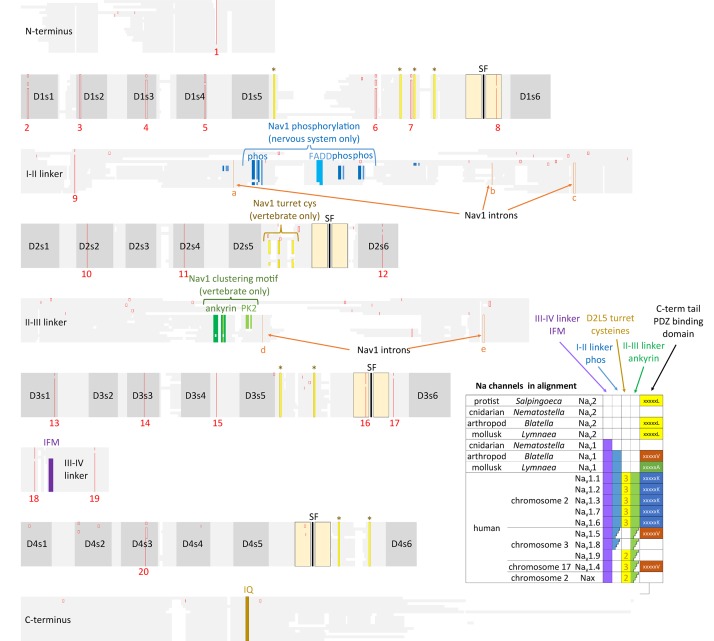

FIGURE 10.

Amino acid alignments illustrating the conservation of twenty intron splice sites (red vertical lines) shared between Nav2 channels and Nav1 channels. The close kinship between the Nav2 channel class only found in non-vertebrates and the classical Nav1 channels is evident in the shared genomic structure. Nav1 differ primarily from Nav2 channels in containing three additional intron splice sites (a–c) in the I-II linker and two splice sites (d,e) in the II-III linker. Extra exons in the I-II linker provides exons coding for conserved phosphorylation sites within invertebrate Nav1 and vertebrate homologs (Nav1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.6, and 1.7) expressed in central nervous systems. Vertebrate, but not invertebrate Nav1 channel homologs contain three extra L5II turret cysteines, and an ankyrin binding site that contribute to the localized clustering of Nav1 channels in vertebrate Axon Initial Segments and nodes of Ranvier (Hill et al., 2008). Nav1 channels possess an IFM motif and surrounding residues within the III-IV linker which contribute to the fast inactivation (West et al., 1992). Nav2 and Nav1 channels possess a conserved proximal C-terminus containing an IQ motif required for calmodulin binding (Ben-Johny et al., 2014, 2015). Different C-terminal motifs containing PDZ binding domains are possessed in sodium channels. Amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE 3.7 (Edgar, 2004) within EMBL-EBI web interface (Chojnacki et al., 2017).

A defining feature that ubiquitously separates Nav1 and Nav2 channels is the lysine residue in Domain II (cnidarians) and III (all others metazoans) of the HFS site in the selectivity filter that confers the high sodium selectivity of Nav1 channels (Heinemann et al., 1992; Schlief et al., 1996). With substitution of the glutamate residue for a lysine residue DKEA or DEKA HFS site in Nav1 for the glutamate (E) in the DEEA selectivity filter of Nav2 channel of single-cell choanoflagellate, S. rosetta, the Nav2 channel transforms from being non-selective for calcium and sodium ions to exclusively selective for sodium ions (Mehta, 2016), resembling the Nav1 channels found in animals with nervous systems.

Nav1 Channels Expanded in Gene Numbers in Vertebrates to Fill Novel Tissue Niches

Sodium channels expanded from one gene (the condition in invertebrates) to ten vertebrate genes by gene duplication (Figure 1), and this heritage can be traced by their linkage to HOX (homeotic) developmental genes (Lopreato et al., 2001). Vertebrate sodium channels Nav1.1, Nav1.2, Nav1.3 and Nav1.7, are expressed primarily in central and peripheral nervous systems and are coded on human chromosome number 2 (linked to HOX D gene) (Lopreato et al., 2001). Nav1.6 is the primary sodium channel found in vertebrate myelinated axons at Nodes of Ranvier, is coded on chromosome number 12, and is linked to HOX C gene (Lopreato et al., 2001). Nav1.8 and Nav1.9 are expressed in dorsal root ganglia, and Nav1.5 is primarily expressed in heart muscles (Lopreato et al., 2001). Nav1.5, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 are clustered on chromosome 3, linked to Hox A (Lopreato et al., 2001). Nav1.4 is specialized to vertebrate skeletal muscle, and is found on chromosome 17, linked to Hox B (Lopreato et al., 2001). A tenth vertebrate sodium channel, Nax, (located on chromosome 2) is the most diverged in sequence, is lacking voltage-sensitive gating and plays a likely role as a putative salt sensor in the subfornical organ (Noda and Hiyama, 2015).

Specializations Within Cytoplasmic Regions (Linkers And Termini) of Four Domain Channels are Not Evident in Cngk Channels

A consequence of chaining of domains together in the four domain structure of the 4 × 6 TM channels is that it generates opportunities for divergence and specialization within the differing voltage-sensor and pore domains. It creates unique extensions of differing extracellular turrets or intracellular linkers linking the four domains, and a trimming down to singleton, asymmetrically arranged, amino- and carboxyl-termini in 4 × 6 TM channels compared to the four N- and C- terminal tails in the repeating four subunits composing the 1x6TM potassium channels (Long et al., 2005) or bacterial sodium channels (Payandeh et al., 2011) or (Figure 2). Cyclic nucleotide-gated potassium channel (CNGK) channels are a 4 × 6 TM channel representative amongst the potassium channel superfamily. CNGK channels lack the uniquely different extracellular turret extensions in differing domains or asymmetrical intracellular linkers between domains that are characteristic of 4 × 6 TM sodium or calcium or NALCN channels (Bonigk et al., 2009). CNGK channels possess a pseudo-symmetry of four nearly identically repeating domains, linked together by equally short and repeating, cytoplasmic linkers and extracellular regions. There is a similarly positioned cyclic nucleotide binding domain (CNBD) within each of their four domains [Bonigk et al., 2009; Fechner et al., 2015]. The CNGK channels appears to be ancient like the lineage of 4 × 6 TM calcium channels with representatives in single cell choanoflagellates (Fechner et al., 2015), in marine invertebrates (Bonigk et al., 2009) and in vertebrates (fish) (Fechner et al., 2015). There appears to be no obvious adaptations or specializations in the four domains of CNGK channel homologs, despite their apparent ancient history. CNGK channels contain four repeating subunits linked together, but only the sodium, calcium and NALCN channel lineage adopted a particular asymmetrical architecture.

The III-IV Linker and Proximal C-Terminal IQ Domain Represent a Globular Domain Which Regulates Calcium- and Voltage-Sensitive Gating

The most constrained of the cytoplasmic linkers is the III-IV linker which is always shorter than the I-II and II-III linkers in 4 × 6 TM channels (Figure 2B), and limited in size to mostly 53 to 57 amino acids (Stephens et al., 2015). The exception is the unusual optional splicing of inserts (e.g. exon 25C) in invertebrate and vertebrate Cav3 T-type calcium channels (Senatore and Spafford, 2012). Also highly conserved is a calcium-calmodulin binding IQ domain within the first 155 aa downstream of the proximal C-terminus in Cav1, Cav2, Nav1 and Nav2 channels, but is absent in Cav3 T-Type channels or NALCN channels (Figures 7, 10). The calmodulin binding in the C-terminus puts a calcium ion sensor within the pathway of calcium entry through the channel pore of calcium channels (Lee et al., 1985; Zuhlke et al., 1999) and resides in a similar position in sodium channels (Mori et al., 2000; Potet et al., 2009; Sarhan et al., 2009) to potentially regulate channel gating. The conserved III-IV linker and the C-terminal domain join to form a globular domain in the cryo-electron microscopy of single calcium channel (Wu et al., 2015, 2016) and sodium channel (Shen et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2017) nanoparticles.

The globular domain formed by the III-IV linker and proximal C-terminus generates a qualitatively different regulation of gating in different calcium and sodium channels, based on sequence differences. A highly conserved IQ motif among L-type channels contributes to a canonical calcium-sensitive inactivation shared amongst invertebrate Cav1 and vertebrate Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels (Taiakina et al., 2013). This conservation extends to single cell protozoans, including Paramecium L-type currents which possesses a calcium-calmodulin dependent inactivation (Brehm et al., 1980). A less conserved proximal C-terminal IQ motif engenders a calcium-dependent facilitation of vertebrate Cav2.1 and Cav2.2 channels involving calmodulin kinase activation (Christel and Lee, 2012). A calcium dependent facilitation and relief of G-protein βγ subunit inhibition by repetitive nerve activity are uniquely featured in vertebrate synaptic Cav2 calcium channels (Zamponi and Currie, 2013), and such modulation is lacking in homologous invertebrate Cav2 channels (Dunn et al., 2018). Invertebrates Cav2 channels are regulated by G-protein coupled receptor signaling that involves a non-voltage dependent form of regulation of activity involving phosphorylation by SRC kinase (Dunn et al., 2018) or cAMP dependent protein kinase A (Huang et al., 2010).

All sodium channels have a highly conserved proximal C-terminal IQ motif, including Nav2 channels in single cell, choanoflagellate Nav2 (Figure 10; Mehta, 2016). The proximal C-terminal IQ motif contributes to a calcium-sensitive regulation that is variable amongst different vertebrate Nav1 channels (Mori et al., 2000; Potet et al., 2009; Sarhan et al., 2009), with a potential secondary binding site for calmodulin in the III-IV linker (Sarhan et al., 2009, 2012). Cav3 T-Type channels differ from other calcium and sodium channels in possessing an equivalent high affinity binding site for calmodulin at their unique “gating brake” located in the proximal I-II linker at homologous location where the accessory Cavβ subunits normally associate with Cav1 and Cav2 channels (Chemin et al., 2017).

Fast, Voltage-Sensitive Gating is Contributed by the Iii-Iv Linker in Nav1 Channels

Nav1 sodium channels are differentiated from calcium channels in possessing a very rapid gating that is required for generating high frequency trains of action potential spikes milliseconds in length, observed in nervous systems (Hodgkin and Huxley, 1952). Faster sodium channel gates contribute to a faster overshooting action potential, while slower and higher voltage-activated calcium channels contribute to a plateau potential following the overshoot, such as in the vertebrate ventricular action potential (Hille, 2001).

A key player which differentiates fast Nav1 channel gating is in the III-IV linker (Ulbricht, 2005) (Figure 10). Glycine residues flanking the III-IV linker create a flexible hinge, permitting movement of the III-IV linker, and rapid inactivation, within milliseconds of sodium channel opening (Kellenberger et al., 1997). A key “IFM” motif in the center of the III-IV linker, serves as a critical “latch” for the “hinged lid” (West et al., 1992), The IFM motif forms a plug inserting in the corner surrounded by the outer S4-S5 and inner S6 segments in repeats III and IV in three dimensional structure, indicating a likely allosteric blocking mechanism for fast inactivation gating in Nav1 channels (Yan et al., 2017). The “IFM” motif, and its surrounding conserved sequence of the III-IV linker is absent in Nav2 channels, and appears to be a critical structural feature responsible for the slower inactivation gating of Nav2 channels in choanoflagellates, according to our mutagenesis studies (Mehta, 2016). Other fine tuning for fast channel gating in Nav1 channels include likely changes to the speed of voltage-sensor gating charge movements and the coupling efficiency of the voltage-sensors to pore gates (Capes et al., 2013), as well as roles for the proximal C-terminus which includes a calcium sensor in a calmodulin-binding IQ motif (Christel and Lee, 2012), found in sodium and calcium channels.

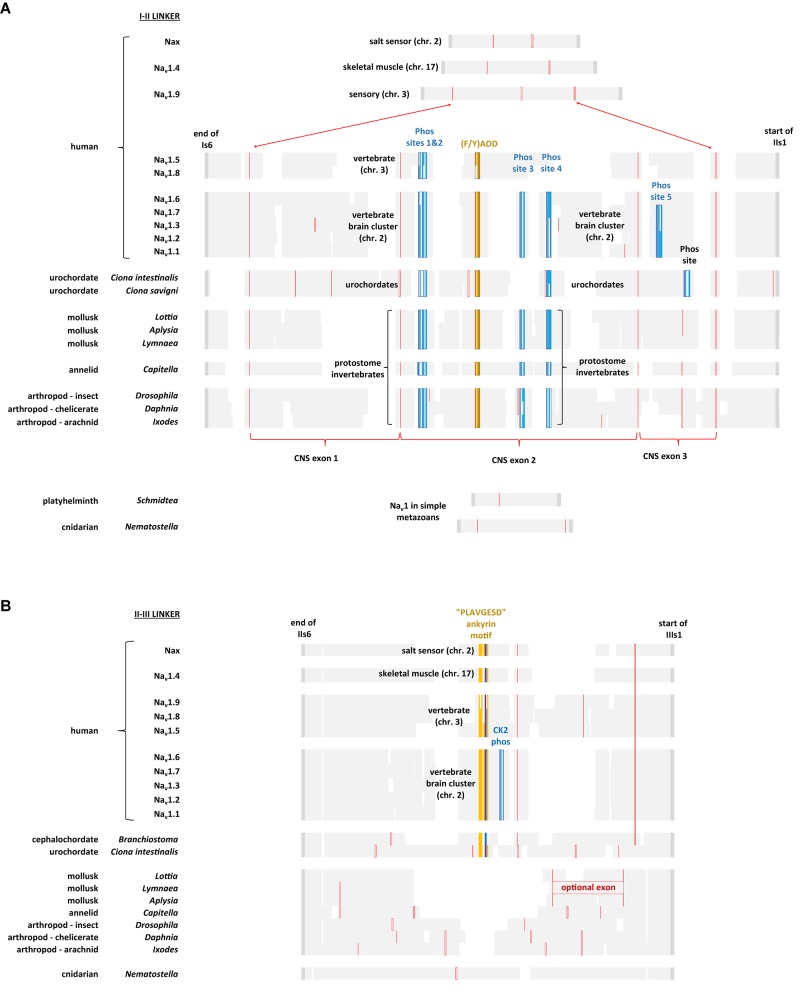

Nav1 Channels from Protostome Invertebrates and Those Expressed in Vertebrate Nervous Systems Share Protein Kinase Phosphorylation Sites in the I-II Linker

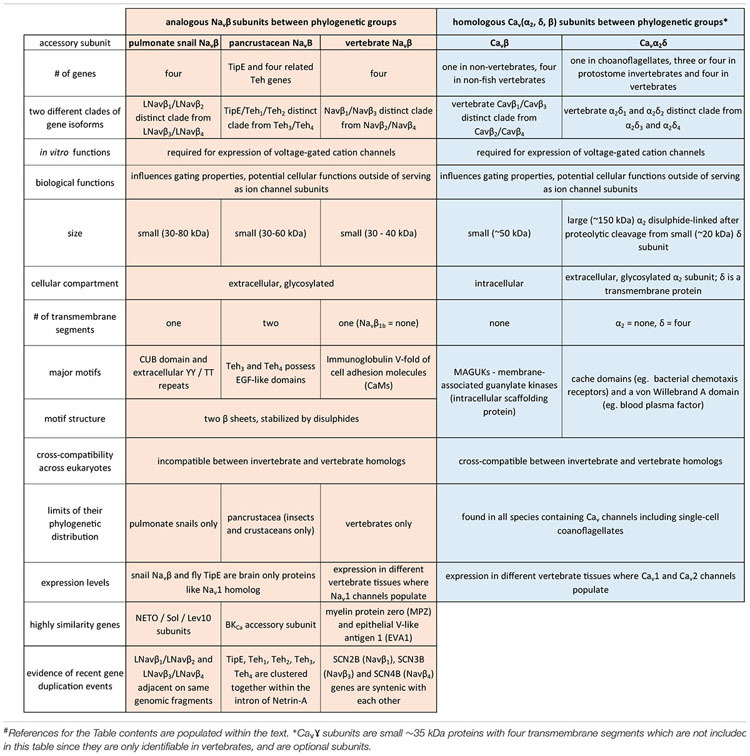

The region of greatest sequence divergence between Nav2 and Nav1 channels is in the cytoplasmic I-II and II-III linkers, and these differences appear to relate to the increasing specialization of Nav1 channels for more sophisticated signaling, that reaches its apex in vertebrate tissues (Figures 10, 11). Cytoplasmic regions linking the four domains created in the first 4 × 6 TM channels, diverged and specialized for the more complex and diverse tissue environments for different genes isoforms as numbers grew from singleton gene homologs of the simplest single cell organisms to the ten sodium and ten calcium channel genes available in the vertebrate body plan.

FIGURE 11.