Abstract

We determined the complete genome sequence of a sacbrood virus (SBV) infecting Indian honey bee (Apis cerana indica) from Tamil Nadu, India named as AcSBV-IndTN1. The genome of AcSBV-IndTN1 comprised of 8740 nucleotides, encoding a single large ORF containing 2849 amino acids flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions. Results of phylogenetic tree analysis based on complete genomes of SBV isolates indicated that the virus isolates from India isolated from the Asiatic honey bee A. cerana (AcSBVs) formed a separate group along with six Vietnam isolates and three Chinese isolates. The AcSBV-IndTN1 isolate showed closer genetic relationship with other isolates from India. The second major group had both AcSBVs and AmSBVs (virus isolated from European honey bee, Apis mellifera SBV) of Korea, China and Vietnam. The third and a distantly related group had AmSBVs of Australia, UK, USA and Korea. The results obtained from phylogenetic analysis were further supported with evolutionary distance analysis. AcSBV-IndTN1 isolate open reading frame had 95–99% amino acid sequence similarity with other Indian isolates and 92–96% with AcSBVs and AmSBVs of other geographical locations. In addition, sequence difference count matrix ranged from 154 to 907 nt among all the SBV isolates. This suggests that the virus isolates have evolved significantly in different geographical locations but isolates on different hosts in a given location/country are closely related. The high similarity in the genome among the AcSBV and AmSBV isolates indicate possible cross-infections and recombination of SBV isolates in Asian continent where both the honey bee species are reared in close proximity. Gene flow between SBV population indicating that an infrequent gene flow occur between them. The pattern of molecular diversity in SBV population revealed that the occurrence of recent population expansion of SBV. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report of the complete nucleotide sequence of AcSBV from Tamil Nadu, India. This study provided an opportunity to establish the molecular evolution of SBV isolates and shall be useful in the development of diagnostics and effective disease control strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13337-018-0490-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Sacbrood virus (SBV), Apis cerana indica, Reverse transcriptase polymerase-chain reaction, Complete genome, Honey bee

Introduction

Apis cerana indica Fab., has been one of the important domesticated species utilized for commercial beekeeping in India. Among the honey bee (Order: Hymenoptera and Family: Apidae) viruses, the sacbrood virus (SBV) is one of the most severe threats to the health of A. cerana and Apis mellifera [3]. SBV is a picorna-like virus and belongs to the genus Iflavirus in the family Iflaviridae [6] with a single stranded positive sense RNA genome of approximately 8.8 kb [19]. SBV particles are 28–30 nm in diameter and non-enveloped. AcSBV disease was first observed in 1976 in Thailand on A. cerana causing 100% mortality [2]. In India, this disease first appeared in 1978 in North India and had virtually wiped out colonies of A. cerana indica [22]. The AcSBV is popularly known as the Thai sacbrood virus (TSBV) as it was believed to be introduced from Thailand into India. During 1991–1992, the catastrophic outbreak of the SBV disease resulted in the destruction of more than 90% of the then existing bee colonies in the South India causing a drastic drop in the honey production [5]. This disease has since then been a reason for colony loss in regions wherever A. cerana indica is reared. This virus causes quick dwindling and sometimes even perishing of the bee colonies. The disease spreads and becomes serious because of crowding, social insect interactions, mutual grooming, food sharing, exchange and communication [15]. Reverse transcriptase polymerase-chain reaction (RT-PCR) has been proved to be a sensitive molecular method to detect SBV directly in samples of diseased honey bees and their brood [1]. Partial sequences have been determined for some Indian isolates [18], but report on a complete genome sequence was lacking. Here, we report the complete genome of AcSBV isolate collected from Tamil Nadu state of India to compare with other isolates to know the evolutionary history of the virus. This information will assist in the development of molecular diagnostic tests and effective disease management strategies.

Materials and methods

Sample collection, RNA isolation and sequencing

The infected honey bee prepupae were collected from A. cerana indica colonies at the Apiary of Department of Agricultural Entomology, TNAU, Coimbatore and stored at − 20 °C until used for the studies. Healthy prepupae were also used as control. The total RNA was isolated from infected prepupae samples as per the method described [1]. First strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from extracted RNA using a RevertAidTM First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA with an oligo(dT) primer according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nine sets of primer pair were designed based on the sequence of the SBV-UK genome and used to amplify overlapping PCR products of complete genome of SBV (Table 1). The resulting cDNA (2 μl) was amplified in 25 μl reaction mixture. PCR amplification was performed in a Veriti 96 well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, USA). The amplification conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 49–53 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s and a final extension of 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified RT-PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis through 1.5% agarose gels, and the gel was documented. The amplified products were purified using a GenElute Gel Extraction Kit (Sigma Aldrich, USA), quantified and cloned into the pTZ57R/T cloning vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two clones of each PCR product were sequenced in both directions.

Table 1.

List of primer sequences used for AcSBV genome sequencing primers designed in the study to synthesis whole genome of AcSBV through RT-PCR

| Primer code | Sequence (5′–3′) | Position |

|---|---|---|

| AcSBV1 FP | GGTGCTTCGAGATTTACTTTGACGG | 1–21 |

| AcSBV2 RP | TAAGGCCACCGGATTTACTCGCAT | 1520–1543 |

| AcSBV3 FP | CTGGATCAATTGGGCCGAAGT | 1399–1420 |

| AcSBV4 RP | CATTCTAGAAGGCGGCATTATAGGT | 2557–2581 |

| AcSBV5 FP | GCGTAGACCAGTATTGTTGTT | 2494–2512 |

| AcSBV6 RP | TACCTGATTTCCCTCATCGT | 3150–3169 |

| AcSBV7 FP | CTCTGATGAGCACGCTCGAGTTCA | 3100–3123 |

| AcSBV8 RP | AGCACTGGACTGAGGAACAGTCA | 4122–4144 |

| AcSBV9 FP | CGGATGCTCAGCTTATTACCACAG | 4008–4031 |

| AcSBV10 RP | CAAACGCAAAGATCCCACTTCAG | 4899–4912 |

| AcSBV11 FP | CTAAGGAATGGTTGGTGGCGAAGT | 4800–4823 |

| AcSBV12 RP | AGTAATTTCCCTCTCTCGCATC | 5794–5815 |

| AcSBV13 FP | ATGTGGCTCGCTCTCTGATGCG | 5778–5805 |

| AcSBV14 RP | CCTCCTTAATGGCACGCACA | 6532–6551 |

| AcSBV15 FP | ATGGGACAGTGGCTTTATTACC | 6501–6522 |

| AcSBV16 RP | CTACATAAGGAAAACCCGCACT | 7499–7520 |

| AcSBV17 FP | TGAAACCCTTGGTGGTGAAACC | 7401–7422 |

| AcSBV18 RP | AACCAATATAGCATATATGAGACC | 8706–8729 |

Sequence analysis

The sequences were analyzed using BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information, USA) to identify related sequences and aligned using CLUSTALW [24]. Sequence identity matrix and sequence difference count matrix were calculated using Bioedit program version 7.05 [9]. Multiple alignments were used to infer the phylogenies and the evolutionary distance with the maximum-likelihood (ML) method implemented in MEGA 7 [12]. To obtain the ML tree topologies, 1000 bootstrap replicates were performed for each dataset. The details on information on the virus isolates which were subjected to phylogenetic analysis are given in the Table 2. The AcSBV-IndTN1 sequence determined in this study has been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under accession no. KX663835 and used as a reference sequence for analysis. Ka/Ks value was calculated using the DnaSP version 5.10 [14] to analyze synonymous and non-synonymous mutations at nt level, which really affect the amino acid (aa) sequences of the protein. Genetic differentiation between the SBV populations was examined by three permutation-based statistical tests, Ks*, Z, and Snn [11]. The level of gene flow between populations were measured by estimating Fixation index (FST), Tajima’s D, Fu and Li’s D, Fu and Li’s F tests, haplotype and nucleotide diversity using DnaSP version 5.10 [14].

Table 2.

Analysis of evolutionary distance, Ka/Ks ratio, and per cent sequence identity and sequence difference count matrix of open reading frame of AcSBVIndTN1 isolate with other SBV isolates

| S. nos. | Isolate | Accession number | Evolutionary distance | Ka | Ks | Ka/ks | NT identity (%) | Sequence different count matrix | AA identity (%) | Sequence different count matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AcSBV-IndII2 | JX270795 | 0.029 | 0.0298 | 0.0238 | 1.2521 | 97 | 248 | 98 | 69 |

| 2 | AcSBV-IndK1A | JX270796 | 0.031 | 0.0294 | 0.0382 | 0.7696 | 97 | 265 | 97 | 75 |

| 3 | AcSBV-IndK5B | JX270797 | 0.034 | 0.0321 | 0.0396 | 0.8106 | 97 | 286 | 98 | 71 |

| 4 | AcSBV-IndK3A | JX270798 | 0.043 | 0.0374 | 0.0610 | 0.6131 | 95 | 394 | 97 | 96 |

| 5 | AcSBV-IndS2 | JX270799 | 0.050 | 0.0474 | 0.0597 | 0.7939 | 95 | 450 | 95 | 134 |

| 6 | AcSBV-IndII9 | JX270800 | 0.018 | 0.0181 | 0.0159 | 1.1383 | 98 | 154 | 99 | 34 |

| 7 | AcSBV-IndII10 | JX194121 | 0.038 | 0.0383 | 0.0346 | 1.1069 | 96 | 320 | 97 | 97 |

| 8 | AcSBV-Kor | HQ322114 | 0.083 | 0.0796 | 0.0866 | 0.9191 | 92 | 709 | 95 | 147 |

| 9 | AcSBV-VietSBM2 | KC007374 | 0.057 | 0.0531 | 0.0688 | 0.7718 | 94 | 508 | 96 | 109 |

| 10 | AcSBV-ChiFZ | KM495267 | 0.078 | 0.0747 | 0.0827 | 0.9032 | 92 | 692 | 94 | 170 |

| 11 | AcSBV-ChiSXnor | KJ000692 | 0.075 | 0.0725 | 0.0789 | 0.9188 | 93 | 641 | 95 | 149 |

| 12 | AcSBV-ChiBJ2012 | KF960044 | 0.077 | 0.0742 | 0.0813 | 0.9126 | 92 | 657 | 94 | 164 |

| 13 | AcSBV-ChiCQA | KC285046 | 0.079 | 0.0767 | 0.0827 | 0.9274 | 90 | 857 | 92 | 217 |

| 14 | AmSBV-UK | AF092924 | 0.104 | 0.1022 | 0.1012 | 1.0098 | 90 | 855 | 95 | 135 |

| 15 | AmSBV-Kor21 | JQ390591 | 0.108 | 0.1015 | 0.1187 | 0.8550 | 90 | 889 | 95 | 155 |

| 16 | AmSBV-Kor19 | JQ390592 | 0.086 | 0.0818 | 0.0954 | 0.8574 | 91 | 738 | 95 | 155 |

| 17 | AmSBV-Kor1 | KP296800 | 0.106 | 0.1007 | 0.1124 | 0.8959 | 90 | 873 | 95 | 153 |

| 18 | AmSBV-Kor2 | KP296801 | 0.086 | 0.0827 | 0.0903 | 0.9158 | 92 | 726 | 95 | 151 |

| 19 | AcSBV-Kor3 | KP296802 | 0.081 | 0.0789 | 0.0818 | 0.9645 | 92 | 698 | 95 | 146 |

| 20 | AcSBV-Kor4 | KP296803 | 0.085 | 0.0820 | 0.0859 | 0.9545 | 91 | 729 | 95 | 147 |

| 21 | AcSBV-VietLD | KJ959613 | 0.066 | 0.0632 | 0.0722 | 0.8753 | 96 | 568 | 96 | 116 |

| 22 | AcSBV-VietHYnor | KJ959614 | 0.084 | 0.0804 | 0.0898 | 0.8953 | 91 | 733 | 95 | 148 |

| 23 | AcSBV-Viet1 | KM884990 | 0.084 | 0.0814 | 0.0868 | 0.9377 | 91 | 732 | 95 | 148 |

| 24 | AcSBV-Viet2 | KM884991 | 0.084 | 0.0814 | 0.0875 | 0.9302 | 91 | 734 | 95 | 149 |

| 25 | AcSBV-Viet3 | KM884992 | 0.085 | 0.0822 | 0.0853 | 0.9636 | 91 | 737 | 95 | 155 |

| 26 | AmSBV-Viet4 | KM884993 | 0.082 | 0.0790 | 0.0869 | 0.9090 | 92 | 719 | 95 | 141 |

| 27 | AcSBV-Viet5 | KM884994 | 0.087 | 0.0828 | 0.0937 | 0.8836 | 91 | 754 | 94 | 162 |

| 28 | AmSBV-Viet6 | KM884995 | 0.067 | 0.0647 | 0.0733 | 0.8826 | 93 | 583 | 96 | 124 |

| 29 | AcSBV-VietBP | KX668139 | 0.072 | 0.0701 | 0.0742 | 0.9447 | 93 | 618 | 95 | 154 |

| 30 | AcSBV-VietNA | KX668140 | 0.070 | 0.0662 | 0.0816 | 0.8112 | 93 | 622 | 95 | 135 |

| 31 | AcSBV-VietBG | KX668141 | 0.073 | 0.0702 | 0.0767 | 0.9152 | 93 | 639 | 95 | 148 |

| 32 | AcSBV-ChiCQ1 | KJ716805 | 0.081 | 0.0789 | 0. 0812 | 0.9716 | 90 | 816 | 94 | 180 |

| 33 | AcSBV-ChiCQB | KJ716806 | 0.080 | 0.0774 | 0.0826 | 0.9370 | 91 | 809 | 94 | 184 |

| 34 | AmSBV-CRBrno | KY273489 | 0.106 | 0.1054 | 0.0979 | 1.0766 | 90 | 868 | 95 | 140 |

| 35 | AmSBV-USMD1 | MG545286 | 0.109 | 0.1046 | 0.1148 | 0.9111 | 90 | 896 | 95 | 145 |

| 36 | AmSBV-USMD2 | MG545287 | 0.109 | 0.1045 | 0.1146 | 0.9118 | 90 | 894 | 95 | 146 |

| 37 | AmSBV-Aus1 | KY887697 | 0.110 | 0.1051 | 0.1169 | 0.8990 | 89 | 907 | 95 | 154 |

| 38 | AmSBV-Aus2 | KY887698 | 0.109 | 0.1041 | 0.1161 | 0.8966 | 90 | 900 | 95 | 155 |

| 39 | AmSBV-AusS3 | KY887699 | 0.110 | 0.1056 | 0.1160 | 0.9103 | 89 | 907 | 95 | 151 |

| 40 | AmSBV-AusWA2 | KY465671 | 0.109 | 0.1032 | 0.1181 | 0.8738 | 90 | 897 | 95 | 153 |

| 41 | AmSBV-AusWA1 | KY465672 | 0.105 | 0.0996 | 0.1137 | 0.8759 | 90 | 873 | 95 | 149 |

| 42 | AmSBV-AusVN3 | KY465673 | 0.110 | 0.1048 | 0.1189 | 0.8814 | 90 | 898 | 95 | 154 |

| 43 | AmSBV-AusVN2 | KY465674 | 0.104 | 0.0982 | 0.1131 | 0.8682 | 90 | 861 | 95 | 152 |

| 44 | AmSBV-AusVN1 | KY465675 | 0.109 | 0.1038 | 0.1159 | 0.8955 | 90 | 901 | 95 | 156 |

| 45 | AmSBV-AusTAS | KY465676 | 0.105 | 0.0993 | 0.1130 | 0.8787 | 90 | 872 | 95 | 153 |

| 46 | AmSBV-AusSA | KY465677 | 0.104 | 0.0981 | 0.1123 | 0.8735 | 90 | 853 | 95 | 149 |

| 47 | AmSBV-AusQLD | KY465678 | 0.109 | 0.1030 | 0.1162 | 0.8864 | 90 | 890 | 95 | 154 |

| 48 | AmSBV-AusNT | KY465679 | 0.101 | 0.0973 | 0.1038 | 0.9373 | 90 | 835 | 95 | 146 |

| 49 | CSBV-ChiJL | KU574661 | 0.077 | 0.0749 | 0.0788 | 0.9505 | 92 | 676 | 95 | 153 |

| 50 | CSBV-ChiSXYL | KU574662 | 0.078 | 0.0747 | 0.0807 | 0.9256 | 92 | 652 | 95 | 137 |

| 51 | CSBV-ChiLN | HM237361 | 0.070 | 0.0685 | 0.0695 | 0.9856 | 93 | 633 | 94 | 176 |

| 52 | SBV-Chi | AF469603 | 0.072 | 0.0691 | 0.0758 | 0.9116 | 93 | 626 | 94 | 163 |

AcSBV, A cerana Sacbrood virus; AmSBV, A mellifera Sacbrood virus; CSBV, Chinese Sacbrood virus; Aus, Australia; Chi, China; CR, Czech Republic; Ind, India; Kor, Korea; Viet, Vietnam; UK, United Kingdom; US, United states

Results and discussion

Nucleotide and amino acid analysis

The complete genome of AcSBV-IndTN1 comprised of 8740 nucleotides (nt), encoding a single large open reading frame (ORF) contained 2849 amino acids (aa) flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). The GC content of AcSBV-IndTN1 genome was 40.7 while AT content was 59.3% with AT/GC ratio of 1.459. The AcSBV-IndTN1 ORF region shared 95–98% nt similarity with other Indian isolates and 89–96% nt identity with isolates from other countries. AcSBV-IndTN1 isolate had 95–99% aa sequence similarity with other Indian isolates and 92–96% with the isolates from other countries (Table 2). The deduced aa sequences for part of the VP1 protein in the eight Indian SBVs and forty-five SBVs from other countries were aligned (supplementary Fig. 1). Among Indian isolates, except for IndS2 and IndK3A isolates, all the AcSBV Indian isolates including isolate generated in this study lacked 10 continuous aa Sequence difference count matrix was ranged 154–907 nt among the SBV isolates used in this study (Table 2). A maximum of 907 nt differences was noticed in AmSBV-AUSS3 isolate while 154 nt difference was observed in AcSBv-IndII9 isolate. Further, protein sequence difference count matrix ranged from 34 to 217 aa for ORF. A minimum of 34 aa and maximum of 157 aa difference was noticed in IndII9 and ChiCQA isolates of AcSBV. Among the Indian isolates, a maximum of 134 aa difference was recorded in IndS2 isolates.

The isolate AcSBV-IndII9 had an evolutionary distance of 0.018 from the reference sequence (Table 2). Between the SBV isolates, the value of an evolutionary distance ranged from 0.018 to 0.110. Among AcSBV isolates, the Indian isolate (AcSBV-IndII9) and Vietnam isolate (AcSBV-Viet5) showed evolutionary distance of 0.018 and 0.087 respectively. The Korean AcSBV isolates had an evolutionary distance ranged 0.081–0.085. Among AcSBV-Vietnam isolates, the nearest isolate VietSBM2 and farthest isolate Viet5 showed an evolutionary distance of 0.057 and 0.087. In case of the Chinese isolates, CSBV-ChiLN isolate had minimum evolutionary distance (0.070) and AcSBV-ChiCQ1 isolate had maximum evolutionary distance of 0.081. The absolute values of an evolutionary distance between or within AmSBV isolates were recorded to be 0.067 for AmSBV-Viet 6 and 0.110 for AmSBV-AUS1, S3 and VN3. AmSBV isolates viz., USMD1, USMD2, AUS2, AUSWA2, AUSVN1 and AUSQLD had same value of evolutionary distance (0.109) from the reference sequence whereas AmSBV isolates belonging to Korea i.e., Kor19 and Kor2 showed 0.086 distance and Kor21 recorded the highest value of 0.108 compared to reference sequence. Isolates of Viet 4 and Viet 6 showed evolutionary distance of 0.082 and 0.067. The ratio of non-synonymous (Ka) to synonymous (Ks) nucleotide substitution rates (Ka/Ks) was calculated to understand the nt change, which affects the aa sequence of the protein. The values of Ka and Ks ranged from 0.0181 to 0.1056 and 0.0159 to 0.1189, respectively. Isolates AmSBV-AUSS3 and AmSBV-AUSVN3 had the highest Ka and Ks values (Table 2). In case of Indian isolates, the value of Ka/Ks ranged from 0.6131 to 1.2521. The isolates AcSBV-IndII2, IndII9, IndII10, AmSBV-UK and AmSBV-CRBrno had comparatively higher Ka/Ks values ranging 1.0098–1.2521 probably owing to high mutations both in nucleotide and protein level when compared to the reference isolate.

Phylogenetic analysis

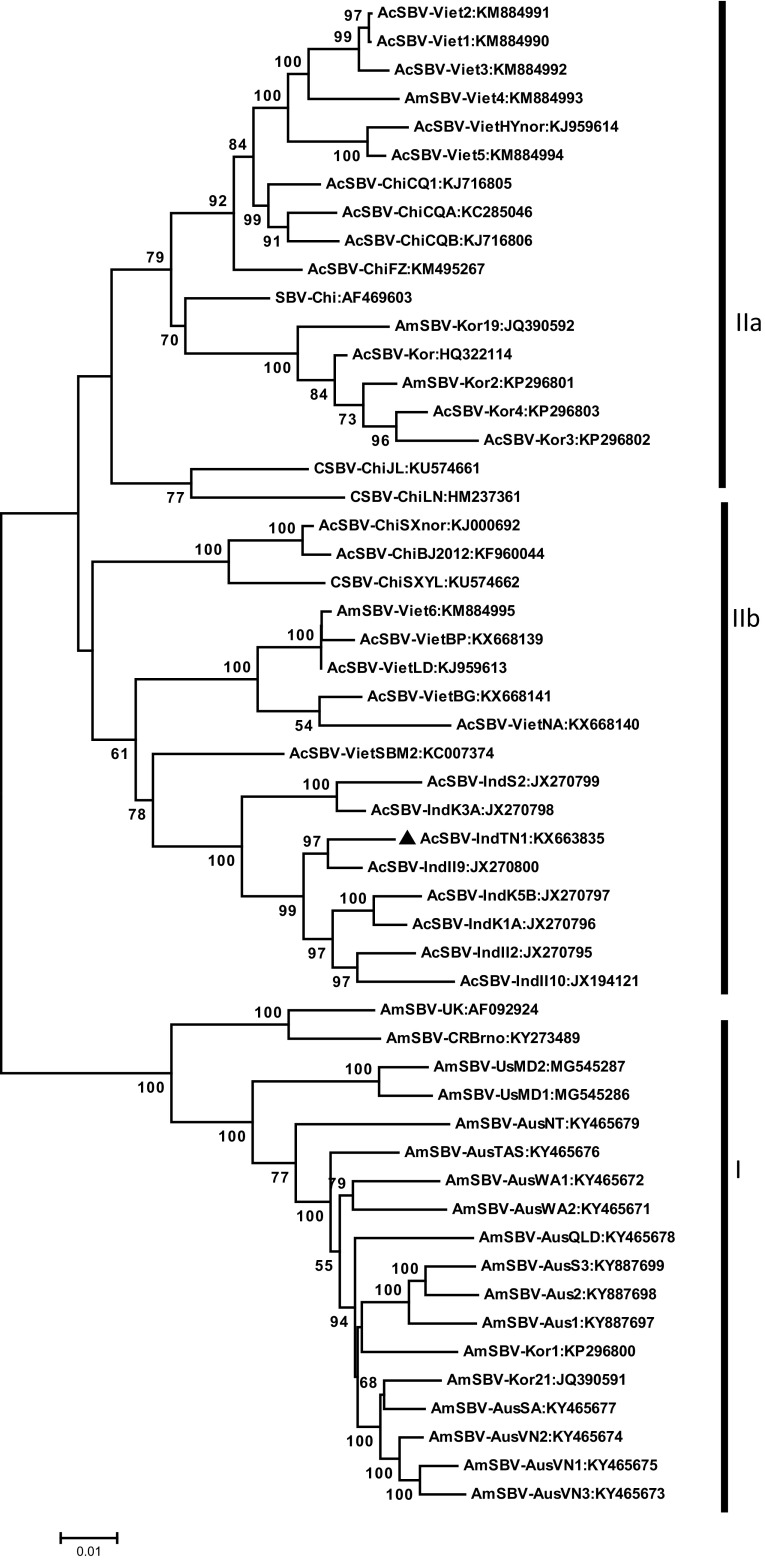

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the complete genome sequences of AcSBV-IndTN1 and the previously reported complete SBV genome nt sequences from other countries retrieved from NCBI Genbank. The phylogenetic tree diverged into two main branches (Fig. 1). In the first main branch, except AmSBV-Viet6 and Viet-4, AmSBV-Kor2 and Kor-19, all other AmSBV isolates from Australia, Czech Republic, United Kingdom and United states were clustered together and formed as one group (I). The second main branch subdivided into two sub branches. Most of the isolates belong to Korea, Vietnam, China are grouped into sub branch IIa. AcSBV-IndTN1 and all the seven complete genome sequences of Indian isolates (unpublished) along with five Vietnam isolates (VietSBM2, VietNA, VietBG, VietBP, VietLD) and three Chinese isolates (ChiSXnor, ChiSXYL, ChiBJ2012) were grouped together to form a sub-branch IIb. The AcSBV-IndTN1 isolate showed closer genetic relationship with other isolates from India. This data reinforces the finding that SBV can cross-infect between A. cerana and A. mellifera species [7, 13, 21]. The Korean isolates were more diverse and were distantly related to Indian isolates. The phylogenetic analysis clearly grouped the isolates based on geographical locations rather than the host on which they were found. For instance, the AcSBV-VietLD was close in genetic makeup with AmSBV-Viet6 which was recorded on different hosts but close geographic location. Similarly, AcSBV-Viet1 to Viet3 were closely related to AmSBV-Viet4 which have different host insects. The close genetic relationship of SBV isolates in a geographic location irrespective of the host insect, highlights the possibility of cross infection of SBV isolates between A. cerana indica and A. mellifera and the management criteria to be followed to keep the disease under check. The high similarity between the AcSBV-IndS2 and the AmSBV-IndHP isolates may be due to the cross-infections. Similar cross-infection has been reported by Li et al. [13]. The phylogenetic variation is consistent with nucleotide similarity among the isolates.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of nucleotide sequence of complete genome of SBV isolates from different regions using MEGA 7.0 software. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. Bootstrap scores above 50% (1000 replicates) are placed at the tree nodes. The scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. For the detailed of isolates, refer Table 2

Population dynamics

Genetic differentiation between populations was examined by three permutation-based statistical tests, Ks*, Z, and Snn [11]. These statistical tests revealed a higher divergence between the Indian isolates and the subpopulations from the Australia, China, Korea, Vietnam and USA (Table 3). FST values among all the isolates were above 0.33, indicating an infrequent geneflow occurring between them. The pattern of molecular diversity was evaluated using Tajima’s D, Fu, and Li’s D* and F* statistical tests at segregating sites, and haplotype and nucleotide diversity at all sites (Table 4). These statistics are expected to have negative values for background selection, genetic hitchhiking, and demographic expansion which also indicate that a population has maintained low frequency polymorphism [10, 23]. Except the isolates of India and USA, all other groups across the world, had negative values of Tajima’s D, Fu, and Li’s D* and F*, indicating that the population expansion of SBV was a recent phenomenon. The haplotype diversity values of all geographic location pairs were equal to one, while the nucleotide diversity values were low (Table 4). Overall, the deviations of the ORF from the neutral equilibrium were analyzed, within/between geographical groups, the results of which were consistent with a model of recent population expansion.

Table 3.

Genetic differentiation measurement for host and geography of SBV population

| Isolates | Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ks* (P value) | Z (P value) | Snn (P value) | FST | Nm | |

| All AcSBV and all AmSBV | 6.134112 (0.0000) | 350.47143 (0.0000) | 0.85417 (0.0000) | 0.34276 | 0.48 |

| Indian AcSBV and other AmSBV | 6.01090 (0.0000) | 138.72120 (0.0000) | 0.96667 (0.0000) | 0.50538 | 0.24 |

| India and Aus | 5.62117 (0.0000) | 46.81189 (0.0000) | 1.00000 (0.0000) | 0.66567 | 0.13 |

| India and China | 5.83538 (0.0000) | 37.63124 (0.0010) | 1.00000 (0.0010) | 0.40213 | 0.37 |

| India and other CSBV | 5.79238 (0.0020) | 18.57440 (0.0020) | 1.0000 (0.0090) | 0.32965 | 0.51 |

| India and Korea | 5.79894 (0.0000) | 32.84091 (0.0000) | 1.00000 (0.0000) | 0.45083 | 0.30 |

| India and US | 5.65358 (0.0180) | 14.46429 (0.0180) | 1.00000 (0.0720) | 0.74581 | 0.09 |

| India and Vietnam | 5.77774 (0.0000) | 57.57190 (0.0000) | 1.00000 (0.0000) | 0.40626 | 0.37 |

| India and all others | 6.25862 (0.0000) | 595.54594 (0.0000) | 1.0000 (0.0000) | 0.34997 | 0.46 |

Ks*, Z, and Snn represent the most powerful sequence-based statistical tests for genetic differentiation and are recommended for use in cases of high mutation rate and small sample size [11]. The Z statistic value results from ranking distances between all pairs of sequences. Snn the frequency with which the nearest neighbors of sequences are found in the same locality; FST, coefficient of gene differentiation or fixation index, which measures inter-population diversity; Nm can be interpreted as the effective number of migrants exchanged between demes per generation

Table 4.

Neutrality tests, haplotype, and nucleotide diversity of SBV population

| Host and geography | Tajima’s D | Fu and Li’s D | Fu and Li’s F | Haplotype diversity | Nucleotide diversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | − 0.75177 | − 0.81112 | − 0.9446 | 1.000 | 0.07711 |

| India and CZ | − 0.97406 | − 0.98500 | − 1.10488 | 1.000 | 0.04971 |

| India and Vietnam | − 0.05609 | − 0.10154 | − 0.10246 | 1.000 | 0.05982 |

| India and US | − 0.27790 | 0.33689 | 0.20656 | 1.000 | 0.05948 |

| India and UK | − 0.95882 | − 0.96735 | − 1.08569 | 1.000 | 0.04947 |

| India AcSBV and all AmSBV | − 0.73071 | − 0.90271 | − 1.00068 | 1.000 | 0.07368 |

| India and Korea | − 0.24809 | 0.05296 | − 0.03671 | 1.000 | 0.00675 |

| India and CSBV | − 0.82193 | − 0.78566 | − 0.90779 | 1.000 | 0.00512 |

| India and China | − 0.54423 | − 0.45027 | − 0.55615 | 1.000 | 0.06069 |

| India and Aus | − 0.13926 | − 0.59369 | − 0.53195 | 1.000 | 0.06837 |

Tajima’s D test compares the nucleotide diversity with the proportion of polymorphic sites which are expected to be equal under selective neutrality. Fu and Li’s D* test is based on the differences between the numbers of singletons (mutations appearing only once among the sequences) and the total number of mutations. Fu and Li’s F* test is based on the differences between the number of singletons and the average number of nucleotide differences between pairs of sequences

Naturally, viruses infecting and circulating in the honeybee populations for a long time can lead to an exchange of viruses among the host populations, and as a consequence, the viruses have evolved more or less independently. Both mutation and recombination are important forces driving the evolution of honey bee RNA viruses [16, 17], but their relative contribution to SBV evolution remains unexplored. This hypothesis of cross infection has also been addressed in several previous studies [4, 7, 8, 13, 20, 25]. SBVs attacking honey bees of a geographic region are more closely related with one another than with other geographic locations irrespective of the host insects A. mellifera and A. cerana indica. This finding assumes significance since in India, different bee species are reared in the same apiary and there is possibility of cross infection by SBV isolates. Hence, it is imperative to keep the two species of bees separately in different apiaries separated by a safe isolation distance of at least a few kilometres to prevent accidental cross infection of drones of either species that freely move between the colonies as well as foraging workers that visit the same flowers.

In conclusion, we report that complete genome of SBV isolate infecting A. cerana from Tamil Nadu, India has been sequenced and compared with 52 complete genome isolates from India and other countries. The nt and aa diversity ranged from 89 to 98% and 92 to 99% respectively. We observed an infrequent geneflow between the isolates used in this study. Further we prepared a model of recent population expansion of SBV isolates as they lack nt diversity within the groups. Since cross-infection of SBV between A. melifera and A. cerana is highly suspected, we recommend that the rearing them in separate apiaries with safe isolation distance.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1. Multiple sequence comparison of all the SBV isolates using aligned VP1 sequences. For the detailed of isolates, refer Table 2 (TIFF 3237 kb)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Department of Agricultural Entomology, TNAU, Coimbatore for extending support in terms of apiary facilities and the Director, ICAR—National Research Centre for Banana, Trichy, India for providing virology laboratory facilities for virus isolation, purification and further molecular studies.

Funding

This publication was made possible through funding from Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, India. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

M. R. Srinivasan, Phone: +91 422 6611214, Email: mrsrini@tnau.ac.in

R. Selvarajan, Phone: 0091-431-2618125, Email: selvarajanr@gmail.com

References

- 1.Aruna R, Srinivasan MR, Selvarajan R. Comparison of genomic RNA sequences of different isolates of Thai Sacbrood virus disease attacking Indian honey bee, Apis cerana indica Fab. in Tamil Nadu by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction method. J Entomol Res. 2016;40:117–122. doi: 10.5958/0974-4576.2016.00022.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey L, Carpenter JM, Woods RD. A strain of Sacbrood virus from Apis cerana. J Invertebr Pathol. 1982;39:264–265. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(82)90027-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YP, Pettis JS, Collins A, Feldlaufer MF. Prevalence and transmission of honeybee viruses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:606–611. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.606-611.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choe SE, Nguyen LT, Noh JH, Kweon CH, Reddy KE, Koh HB, Chang KY, Kang SW. Analysis of the complete genome sequence of two Korean Sacbrood viruses in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Virology. 2012;432:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devanesan S, Jacob A. Thai Sacbrood virus disease of Asian Honey bee Apis cerana indica Fab., in Kerala, India. In: Proceedings of 37th international APIC congress, 28 Oct–1 Nov 2001, Durban, South Africa. 2001. ISBN: 0-620-27768-8.

- 6.Ghosh RC, Ball BV, Willcocks MM, Carter MJ. The nucleotide sequence of Sacbrood virus of the honey bee: an insect picorna like virus. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1514–1549. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-6-1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gong HR, Chen XX, Chen YP, Hu FL, Zhang JL, Lin ZG, Yu JW, Zheng HQ. Evidence of Apis cerana Sacbrood virus Infection in Apis mellifera. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82(8):2256–2262. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03292-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grabensteiner E, Ritter W, Carter MJ, Davison S, Pechhackar H. Sacbrood virus of the honeybee (Apis mellifera): rapid identification and phylogenetic analysis using reverse transcriptase-PCR. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:93–104. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.1.93-104.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. In: Nucleic acids symposium series, vol. 41; 1999. p. 95–98.

- 10.Hey J, Harris E. Population bottlenecks and patterns of human polymorphism. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:1423–1426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson RR. A new statistic for detecting genetic differentiation. Genetics. 2000;155:2011–2014. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Zeng Z, Wang Z. Phylogenetic analysis of the honeybee Sacbrood virus. J Apic Sci. 2016;60(1):31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphic data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Zhang Y, Yan X, Han R. Prevention of Chinese Sacbrood virus infection in Apis cerana using RNA interference. Curr Microbiol. 2010;61:422–428. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9633-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore J, Jironkin A, Chandler D, Burroughs N, Evans DJ, Ryabov EV. Recombinants between Deformed wing virus and Varroa destructor virus-1 may prevail in Varroa destructor-infested honeybee colonies. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:156–161. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.025965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palacios G, Hui J, Quan PL, Kalkstein A, Honkavuori KS, Bussetti AV, Conlan S, Evans J, Chen YP, Vanengeldrop D, Efrat H, Pettis J, Foxter DC, Holmes EC, Briese T, Lipkin WI. Genetic analysis of Israel acute paralysis virus: distinct clusters are circulating in the United States. J Virol. 2008;82:6209–6217. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00251-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rana R, Rana BS, Kaushal N. D Kumar, Priyanka K, Rana K, Azharkhan M, Gwande SJ, Sharma HK. Identification of sacbrood virus disease in honeybee, Apis mellifera L. by using ELISA and RTPCR techniques. Ind. J Biotechnol. 2011;10:274–284. doi: 10.3923/biotech.2011.274.279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy KE, Yoo MS, Kim YH, Kim NH, Ramya M, Jung HN, Thao LETB, Lee HS, Kang SW. Homology differences between complete Sacbrood virus genomes from infected Apis mellifera and Apis cerana honeybees in Korea. Virus Genes. 2016;52:281–289. doi: 10.1007/s11262-015-1268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy KE, Thu HT, Yoo MS, Ramya M, Reddy BA, Lien NTK, Quyen DV. Comparative genomic analysis for genetic variation in Sacbrood virus of Apis cerana and Apis mellifera honeybees from different regions of Vietnam. J Insect Sci. 2017;17:1–7. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iex077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts JMK, Anderson DL. A novel strain of Sacbrood virus of interest to world apiculture. J Invertebr Pathol. 2014;118:71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah FA, Shah TA. Thai sacbrood disease of Apis cerana. Ind Bee J. 1988;50:110–112. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia X, Zhou B, Wei T. Complete genome of Chinese Sacbrood virus from Apis cerana and analysis of the 3C-like cysteine protease. Virus Genes. 2015;50:277–285. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1. Multiple sequence comparison of all the SBV isolates using aligned VP1 sequences. For the detailed of isolates, refer Table 2 (TIFF 3237 kb)