Abstract

Electric field-driven motion of biomolecules is a process essential to many analytics methods, in particular, to nanopore sensing, where a transient reduction of nanopore ionic current indicates the passage of a biomolecule through the nanopore. But before any molecule can be examined by a nanopore, the molecule must first enter the nanopore from the solution. Previously, the rate of capture by a nanopore was found to increase with the strength of the applied electric field. Here, we theoretically show that, in the case of narrow pores in graphene membranes, increasing the strength of the electric field can not only decrease the rate of capture but also repel biomolecules from the nanopore. As the strong electric field polarizes water near and within the nanopore, the high gradient of the field also produces a strong dielectrophoretic force that compresses the water. The pressure difference caused by the sharp water density gradient produces a hydrostatic force that repels DNA or proteins from the nanopore, preventing, in certain conditions, their capture. We show that such local compression of fluid can regulate the transport of biomolecules through nanoscale passages in the absence of physical gates and sort proteins according to their phosphorylated states.

Measurement of DNA transport through nanopores has emerged as a versatile tool for probing nanoscale physics [1–3]. In a typical measurement [4], an external electric field is applied across a thin membrane containing a nanopore to drive a DNA molecule from one side of the membrane to the other, through the nanopore. A prerequisite step to DNA translocation is the capture of DNA by the nanopore. The rate of DNA capture has long been assumed to increase with the strength of the applied electric field [5–9]. As we show below, the rate of DNA capture can exhibit a considerably more complex behavior in the case of narrow pores in 2D membranes.

The probability of DNA entering a nanopore is determined, first and foremost, by the DNA concentration [5, 6] and the nanopore diameter [5, 10]. As nanopore confinement of a polymer comes with an unfavorable entropic cost [11], the capture rate also depends on the length of the DNA polymer [7, 12, 13], the thickness of the insulating membrane [14] and the electrolyte temperature [15, 16]. The capture probability is proportional to how far the electric field extends away from the nanopore, and hence can be manipulated by adjusting the electrolyte concentration [7] or electrically gating the membrane [14]. Governed by both electrostatics and hydrodynamics [8,9, 17], the capture rate can be increased by a hydrostatic pressure gradient [18] or enhanced electro-osmotic flow [19]. The capture rate can be further affected by dielectrophoretic [20, 21], thermophoretic [15, 16] and plasmonic [22] effects.

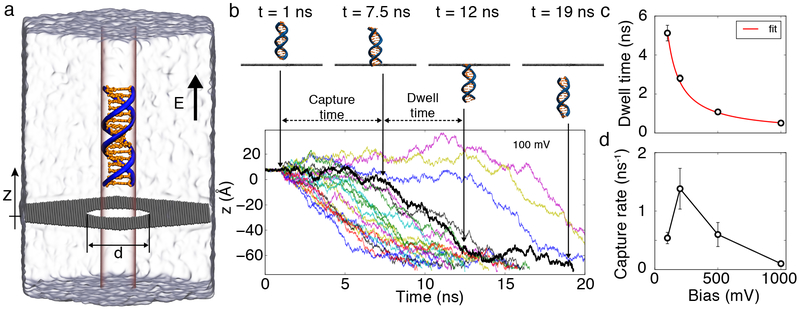

Here, we describe a surprising effect of the electric field strength on the process of DNA and protein capture by narrow pores in atomically-thin membranes. First, we considered a system consisting of a graphene membrane containing a single nanopore [23–25], a fragment of double stranded DNA (dsDNA) placed in front of the nanopore entrance and an electrolyte solution, FIG. 1a. Using the molecular dynamics (MD) method, we simulated an all-atom model of the system under transmembrane biases of different magnitudes [26]. To increase the probability of DNA capture, the DNA molecule was restrained to remain co-axial with the nanopore axis while being free to rotate about its axis and move toward or away from the nanopore, see Supplementary Methods for details, which includes Refs. [27–39].

FIG. 1.

MD simulation of DNA capture and translocation through a graphene nanopore. (a) Simulation setup. A 16 basepair fragment of double stranded DNA (orange and blue) is placed 8 Å away from a 3.5 nm diameter nanopore in a graphene membrane (dark gray) and submerged in a hexagonal prism volume of 1 M KCl electrolyte (semitransparent surface; ions not shown). Phosphorous atoms of the DNA fragment are restrained to a 1.88 nm diameter cylinder coaxial with the nanopore axis; the DNA is free to move along the cylinder and rotate about its axis. An electric field E is applied normal to the membrane. (b) Z-coordinate of the leading base of the DNA fragment in twenty independent MD simulations (each shown using unique color) carried out under a transmembrane bias of 100 mV. The graphene membrane is located at z = 0. Snapshots illustrate the location of the DNA fragment for the highlighted translocation trace (black). For the first 1 ns of each simulation, the z coordinates of the DNA’s phosphorous atoms are restrained to their initial values. (c) The average translocation time versus transmembrane bias, V. Red line shows a 1/V fit. (d) Average capture rate versus transmembrane bias. The average capture rate was computed as the mean of inverse capture times. If a DNA molecule was not captured within 20 ns, the capture time was assumed to be 40 ns, contributing uncertainty to the average capture rate of less than 0.025 ns−1. In panels c and d, the error bars indicate the standard error of mean.

In a typical simulation at a low (100 mV) transmembrane voltage, the DNA molecule was observed to diffuse along the nanopore axis, enter the nanopore, move unidirectionally through the nanopore and, upon exit, diffuse away from the membrane, FIG. 1b and Supplementary Movie 1. Repeating the simulation twenty times at the same transmembrane bias yielded the average time the DNA molecule took to pass through the nanopore—the average translocation time, and the average capture rate defined as the average of the inverse capture time—the time the DNA molecule took to enter the nanopore from the beginning of each simulation, FIG. 1b.

Repeating the simulations at different transmembrane voltages yielded the dependence of the average translocation time and the average capture rate on the transmembrane bias; Supplementary Figure S1 shows permeation traces at all biases. In agreement with previous experimental findings [4, 6, 25], the average translocation time decreases as the inverse of the transmembrane bias, FIG. 1c. The voltage dependence of the capture rate, FIG. 1d, is much more surprising. Increasing the bias from 100 to 200 mV roughly doubled the number of capture events, in broad agreement with previous experimental results [5, 7, 13, 20]. Increasing the bias further to 500 mV decreased the DNA capture rate; the capture rate was close to zero when a 1 V bias was applied. Supplementary Movie 2 illustrates one MD trajectory at 1 V bias: the DNA molecule appears to be repelled from the nanopore entrance despite being drawn toward the nanopore when it is farther away from the membrane. A similar but less pronounced voltage dependence of the capture rate was observed for a shorter (5 bp) fragment of DNA, Supplementary Figure S2 and and S3.

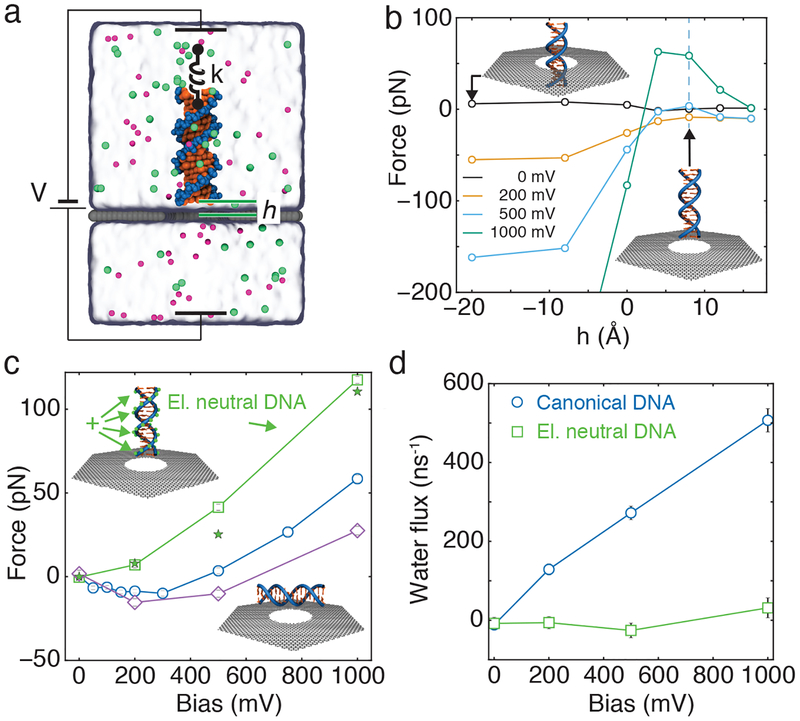

To determine the physical origin of the non-linear dependence of the capture rate, we measured the effective force acting on the DNA molecule as a function of the transmembrane bias, FIG. 2a and Supplementary Movies M3 and M4. As expected, the effective force is zero when no transmembrane bias is applied regardless of whether the DNA is placed in front of the nanopore (h > 0) or threaded through the nanopore (h < 0), FIG. 2b. At 200 mV, the force magnitude monotonically increases as the leading edge of the DNA approaches the nanopore (0 < h < 16 Å), saturating when DNA becomes threaded half-way through the nanopore (−20 A < h < −10 Å); the negative sign of the force indicates a force that pulls DNA through the nanopore. At 500 and 1000 mV, the force behavior is non-monotonic: the force rises as DNA approaches the nanopore before falling sharply as the leading edge of the DNA passes through the plane of the membrane (h = 0). For DNA-membrane distances between 4 and 12 Å, increasing the transmembrane bias changes the sign of the effective force, turning electrophoretic pull on DNA toward the nanopore at smaller biases into repulsion at higher ones. Replotting the effective force as a function of the transmembrane bias for h = 8 Å, blue circles in FIG. 2c, makes this dependence more apparent. The non-monotonic dependence of the effective force indicates the presence of a short-range repulsive force near the nanopore entrance that increases superlinearly with the transmembrane bias.

FIG. 2.

Effective force on DNA. (a) Schematic of MD measurement of the effective force. A DNA molecule is held distance h from the 3.5 nm diameter nanopore in a graphene membrane using harmonic restraints. Steady-state displacement of DNA atoms from their initial coordinates along the nanopore axis reports on the effective force [40]. Each effective force value was determined by averaging over at least three independent simulations each lasting 20 ns. (b) Effective force on DNA held coaxially with a nanopore at different heights relative to the graphene membrane as a function of transmembrane bias; lines are a guide for the eye. Height is defined as the distance between the center of mass of the closest base to the graphene, and the plane of the graphene. The top and bottom insets illustrate systems with h = −20 and h = +8 Å, respectively. Vertical line at h = 8 Å corresponds to data plotted in panel c using blue circles. (c) Effective force versus transmembrane bias for canonical DNA (circles), neutrally charged DNA (squares), horizontally oriented DNA (diamonds) and a theoretical model (stars). All DNA constructs are placed the same distance (h = 8 Å) away from the membrane. (d) Water flux through a 3.5 nm nanopore for canonical and neutrally charged DNA held 8 Å away from the graphene membrane, coaxial with the nanopore, as a function of transmembrane bias.

Repeating the stall force simulations for several nanopore geometries, electrolyte conditions and placements of the DNA molecules with respect to the membrane provided further validation to our observations. Increasing the thickness of the graphene membrane from one to five layers reduced the amplitude but did not eliminate the non-monotonic dependence of the effective force on DNA on bias, Supplementary Figure S4. Increasing the electrolyte concentration from 1 to 2 M or decreasing the pore diameter from 3.5 to 2.9 nm made the non-monotonic dependence slightly more pronounced, Supplementary Figures S5 and S6. Conversely, reducing the ion concentration from 1 M to 200 mM or increasing the pore diameter from 3.5 to 4.9 nm reduced the amplitude of the non-monotonic dependence, Supplementary Figures S5 and S6. Repeating the effective force simulations using weaker restraints, Supplementary Figure S7, or a larger simulation system, Supplementary Figure S8, did not change the effective force values, after taking into account the difference in the spring stretching and the access resistance (Supplementary Note 1, containing Refs. [41–43]), respectively. Finally, placing the DNA parallel to the plane of the graphene membrane did not change the character of the effective force dependence on the transmembrane bias, FIG. 2c, but moderately reduced the amplitude of the non-monotonic effect.

Electro-osmosis is a known determinant of the effective force on DNA in a solid-state nanopore [40, 44–46]. In our systems, however, the non-linear dependence of the effective force on the applied bias does not originate from the electro-osmotic effect. To demonstrate that, we constructed an electrically neutral variant of our DNA molecule by adding one proton worth of electrical charge to each phosphorous atom of the DNA and used it for effective force simulations. The plot of the effective force on the electrically neutral variant of the DNA molecule, FIG. 2c, is a monotonically increasing function of the bias, indicating repulsion from the nanopore at all bias values. In the case of electrically charged (normal) DNA, the average water flux through the nanopore monotonically increases with the bias, illustrating the electro-osmotic effect, FIG. 2d. For the neutral DNA fragment, the flux remains close to zero at all biases. Thus, the electro-osmotic effect does not explain repulsion of DNA from the nanopore.

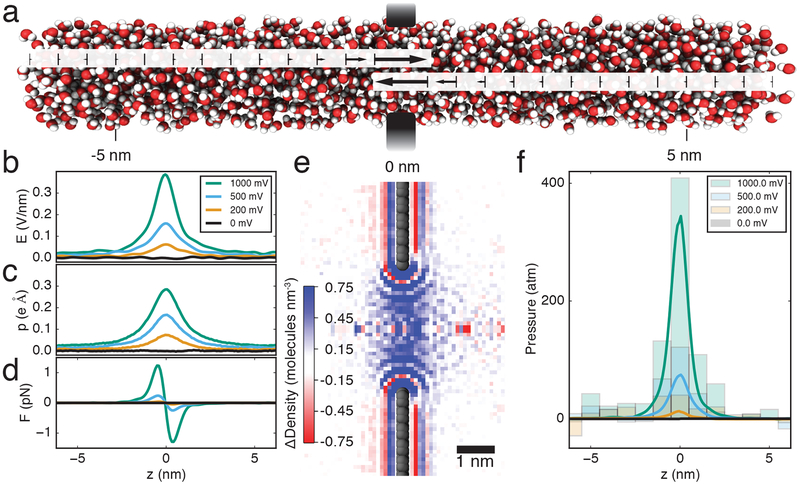

Further analysis identified dielectrophoretic compression of the solvent as the source of the repulsive force. FIG. 3a schematically illustrates the mechanism of the effect. The presence of the nanopore focuses the electric field to the vicinity of the membrane, FIG. 3b. The strong electric field polarizes water near and within the nanopore volume, FIG. 3c. Note that although each water molecule is neutral, it experiences a non-zero net force produced by the spatially varying electric field. The average component of this local dielectrophoretic force on a water molecule along the pore axis Fz(z) = pz(z)dEz(z)/dz, FIG. 3d, is a rapidly varying function of distance. Although both the peak E-field intensity and the local polarization of water increase nearly linearly with the transmembrane bias, Supplementary Figures S9 and S10, the peak dielectrophoretic force increases as its square, Supplementary Figure S11. The force has opposite sign at opposite sides of the membrane, pushing water molecules toward the center of the membrane, compressing the water in the nanopore. The local compression of water in the nanopore is directly confirmed by plotting the average local density difference map, FIG. 3e.

FIG. 3.

Dielectrophoretic pressurization of a graphene nanopore. (a) Schematic illustration of pressure build up caused by dielectrophoresis. The arrows indicate the direction and magnitude of the dielectrophoretic force on water molecules. (b) Electric field strength along the pore axis at several transmembrane biases. For each transmembrane bias, data in panels b–d derive from at least three independent simulations of the open-pore system, each lasting 20 ns. (c) Trajectory- average projection of water dipole moment onto the nanopore axis. (d) Local dielectrophoretic force per water molecule. (e) Map of electrolyte density differential produced by a transmembrane bias. The image shows a cross section of the 3D map obtained by subtracting local electrolyte density maps at 1 and 0 V transmembrane bias; only the region near the nanopore is shown. (f) Local pressure along the nanopore axis. The lines show the pressure values calculated by integration of the force plot (panel d). The bar graph indicates pressure values calculated from the observed changed of water density and the measured water compressibility, Supplementary Figure S12.

The aggregate force on all water molecules creates a pressure in the center of the pore, much like a column of water (all attracted downward by gravity) creates a pressure at the bottom of the column. By integrating this force over all of the water molecules in the column, and dividing by the area of the column, we can estimate the increased pressure in the pore due to the dielectrophoretic force, FIG. 3f. The model predicts a pressure of almost 400 atm at 1 V transmembrane bias in the center of a 3.5 nm pore in a single-layer graphene membrane. Similar local pressure values are obtained when modeling the nanopore system using a continuum approach, Supplementary Note 2, which contains Refs. [47, 48]. Such high local pressure values are not uncommon to nanoscale systems and have been previously found in lipid bilayer membranes [49] and strongly confined liquids [50]. The nanopore volume remained occupied by water at all biases, indicating the lack of voltage-induced dewetting [51]. By determining the compressibility of the electrolyte, Supplementary Figure S12, and computing the local electrolyte density change produced by the transmembrane bias, we obtained an independent estimate of pressure at the center of the nanopore, FIG. 3f, that agrees with the pressure values calculated from the dielectrophoretic effect. Finally, a product of the pressure difference at the DNA ends and the DNA’s cross-section area (490 Å2) provides an independent estimate of the repulsive force on DNA caused by local compression of the electrolyte, filled stars in FIG. 2c, which is in good agreement with the effective force on neutralized DNA directly measured in MD simulations, open squares in FIG. 2c.

The non-monotonic dependence of DNA capture rate on transmembrane bias has thus far eluded experimental observation. In addition to technical difficulties associated with measurements of ionic currents through narrow pores in 2D materials, the bandwidth limitation of the measurement precludes observation of fast DNA translocation events. Indeed, saturation or reduction of the DNA capture rate at high biases could be interpreted as bandwidth-limited decline in detection of successful translocation events [52, 53]. Using non-sticky 2D materials such as boron nitride and less charged biomolecular probes will facilitate experimental observation of the effect.

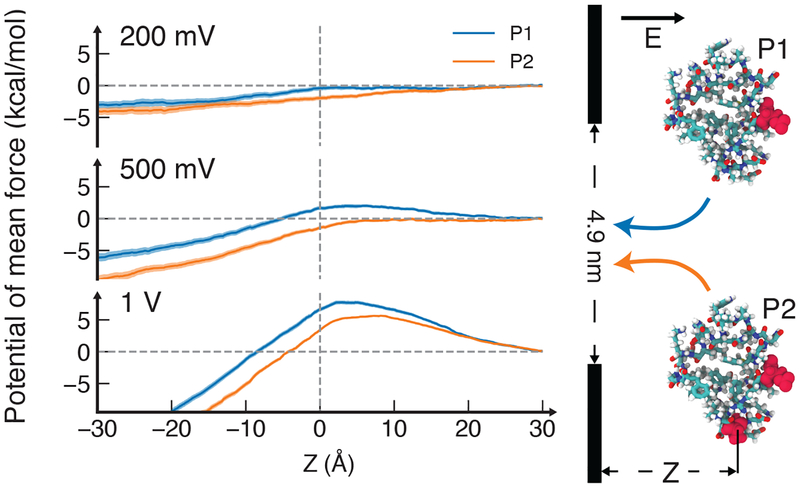

To demonstrate a potential utility of the hydrostatic compression effect, we computed the potential of mean force (PMF) for moving three variants of a villin headpiece protein through graphene nanopores under several transmembrane biases, see Supplemental Material for details of these simulations, which includes Refs. [54, 55]. The PMF for moving an unphosphorylated variant of the protein, Supplementary Figure S13, exhibits a barrier that increases rapidly with the voltage. Similar barriers are observed in the PMFs of both singly and doubly phosphorylated protein at 1V, whereas no such barriers are found at 200 mV, FIG. 4, meaning that, at 200 mV, both proteins can translocate through the nanopore whereas, at 1V, neither protein can. At 500 mV, however, the translocation of doubly phosphorylated protein is unimpeded whereas the singly phosphorylated protein encounters a 2 kcal/mol barrier. Thus, the hydrostatic pressure effect may be used to sort proteins according to their phosphorylation states—common post-translational modifications.

FIG. 4.

Potential of mean force (PMF) of a villin headpiece protein along the symmetry axis of a 4.9 nm diameter nanopore. The PMF was computed for two phosphorylation states of the protein corresponding to the net charge of one (blue, state P1) and three (green, state P2) electrons. Vertical dashed lines schematically illustrate the location of a graphene membrane; horizontal dashed line indicates a 0 kcal/mol value.

In summary, we have shown an unexpected effect of dielectrophoresis on nanopore transport that, instead of promoting DNA capture [20, 21], blocks DNA passage by compressing water in the nanopore. The nanopore dielectric blockade effect could, potentially, be used to sort or filter biomolecules according to their charge-to-volume ratio. On a broader note, our work shows that, despite thirty years of inquiry, the physics of nanopore transport is still full of surprises.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01- GM114204 and R01-HG007406), and through a cooperative research agreement with the Oxford Nanopore Technologies. The authors gladly acknowledge supercomputer time provided through XSEDE Allocation Grant MCA05S028 and the Blue Waters petascale supercomputer system (UIUC).

Contributor Information

James Wilson, Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1110 West Green Street, Urbana, Illinois 61801.

Aleksei Aksimentiev, Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1110 West Green Street, Urbana, Illinois 61801 and Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology.

References

- [1].Dekker C, Nat. Nanotech 2, 209 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zwolak M and Di Ventra M, Rev. Mod. Phys 80, 141 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- [3].Keyser UF, Soc JR. Interf 8, 1369 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kasianowicz JJ, Brandin E, Branton D, and Deamer DW, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 93, 13770 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Henrickson SE, Misakian M, Robertson B, and Kasianowicz JJ, Phys. Rev. Lett 85, 3057 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Meller A, Nivon L, and Branton D, Phys. Rev. Lett 86, 3435 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wanunu M, Morrison W, Rabin Y, Grosberg AY, and Meller A, Nat. Nanotech 5, 169 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Grosberg AY and Rabin Y, J. Chem. Phys 133, 165102 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Muthukumar M, J. Chem. Phys 132, 195101 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Trepagnier EH, Radenovic A, Sivak D, P. GP, and Liphardt J, Nano Lett 7, 2824 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Muthukumar M, Phys. Rev. Lett 86, 3188 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kasianowicz JJ, Brandin E, Branton D, and Deamer DW, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 93, 13770 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Carson S, Wilson J, Aksimentiev A, and Wanunu M, Biophys. J 107, 2381 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Paik K-H, Liu Y, Tabard-Cossa V, Waugh MJ, Huber DE, Provine J, Howe RT, Dutton RW, and Davis RW, ACS Nano 6, 6767 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].He Y, Tsutsui M, Scheicher RH, Bai F, Taniguchi M, and Kawai T, ACS Nano 7, 538 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nicoli F, Verschueren D, Klein M, Dekker C, and Jonsson MP, Nano Lett 14, 6917 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shendruk TN, Hickey OA, Slater GW, and Harden JL, Curr. Opin. Coll. & Interf. Sci 17, 74 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hoogerheide DP, Lu B, and Golovchenko JA, ACS Nano 8, 7384 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].He Y, Tsutsui M, Scheicher RH, Miao XS, and Taniguchi M, ACS Sensors 1, 807 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- [20].Freedman KJ, Otto LM, Ivanov AP, Barik A, Oh S-H, and Edel JB, Nat. Commun 7, 10217 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tian K, Decker K, Aksimentiev A, and Gu L-Q, ACS Nano 11, 1204 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Belkin M, Chao S-H, Jonsson MP, Dekker C, and Aksimentiev A, ACS Nano 9, 10598 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Garaj S, Hubbard W, Reina A, Kong J, Branton D, and Golovchenko JA, Nature 467, 190 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schneider GF, Kowalczyk SW, Calado VE, Pandraud G, Zandbergen HW, Vandersypen LMK, and Dekker C, Nano Lett 10, 3163 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Merchant CA, Healy K, Wanunu M, Ray V, Peterman N, Bartel J, Fischbein MD, Venta K, Luo Z, Johnson ATC, and Drndic M, Nano Lett 10, 2915 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Aksimentiev A, Heng JB, Timp G, and Schulten K, Biophys. J 87, 2086 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, and Schulten K, J. Comput. Chem 26, 1781 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].MacKerell AD Jr., Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL Jr., Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FTK, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE III, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, and Karplus M, J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3586 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wells DB, Belkin M, Comer J, and Aksimentiev A, Nano Lett 12, 4117 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yoo J and Aksimentiev A, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 3, 45 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [31].Miyamoto S and Kollman PA, J. Comput. Chem 13, 952 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- [32].Andersen HC, J. Comput. Phys 52, 24 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- [33].Darden TA, York D, and Pedersen L, J. Chem. Phys 98, 10089 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- [34].Koopman EA and Lowe CP, J. Chem. Phys 124, 204103 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Humphrey W, Dalke A, and Schulten K, J. Mol. Graphics 14, 33 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Aksimentiev A, Brunner R, Cruz-Chu ER, Comer J, and Schulten K, IEEE Nanotechnol. Mag 3, 20 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].van Dijk M and Bonvin AMJJ, Nucleic Acids Res 37, W235 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Aksimentiev A and Schulten K, Biophys. J 88, 3745 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rodnikova M, J. Mol. Liq 136, 211 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- [40].Luan B and Aksimentiev A, Phys. Rev. E 78, 021912 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Roux B, Biophys. J 95, 4205 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hille B, Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol 21, 1 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hall JE, J. Gen. Physiol 66, 531 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ghosal S, Phys. Rev. Lett 98, 238104 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chen Y, Ni Z, Wang G, Xu D, and Li D, Nano Lett 8, 42 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].van Dorp S, Keyser UF, Dekker NH, Dekker C, and Lemay SG, Nat. Phys 5, 347 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gutierrez SA, Bodrenko I, Scorciapino MA, and Ceccarelli M, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 18, 8855 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Booth F, J. Chem. Phys 19, 391 (1951). [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ollila OHS, Risselada HJ, Louhivuori M, Lindahl E, Vattulainen I, and Marrink SJ, Phys. Rev. Lett 102, 078101 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Long Y, Palmer JC, Coasne B, Sliwinska-Bartkowiak M, and Gubbins KE, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 13, 17163 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Strong SE and Eaves JD, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 7, 1907 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Larkin J, Henley RY, Muthukumar M, Rosenstein JK, and Wanunu M, Biophys. J 106, 696 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Mahendran KR, Singh PR, Arning J, Stolte S, Kleinekathofer U, and Winterhalter M, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 22, 454131 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kumar S, Rosenberg JM, Bouzida D, Swendsen RH, and Kollman PA, J. Comput. Chem 13, 1011 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- [55].Grossfield A, “WHAM: the weighted histogram analysis method, version 2.0.9,” http://membrane.urmc.rochester.edu/content/wham.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.