Abstract

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a side effect of antipsychotic medications used to treat schizophrenia (SCZ) and other mental health disorders. No study has previously used pyrosequencing to quantify DNA methylation levels of the DLGAP2 gene; while the quantitative methylation levels among CpG sites within a gene may be correlated. To deal with the correlated measures among three CpG sites within the DLGAP2 gene, this study analyzed DNA methylation levels of the DLGAP2 gene using a linear mixed model (LMM) in a Chinese sample consisting of 35 SCZ patients with TD, 35 SCZ without TD (NTD) and 34 healthy controls (HCs) collected in Beijing, China. The initial analysis using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test revealed that three groups (TD, NTD and HC) had significant differences in DNA methylation level for CpG site 2 (p = 0.0119). Furthermore, the average methylation levels among the three CpG sites showed strong correlations (all p values < 0.0001). In addition, using the LMM, three groups had significant differences in methylation level (p = 0.0027); while TD, NTD and TD + NTD groups showed higher average methylation levels than the HC group (p = 0.0024, 0.0151, and 0.0007, respectively). In conclusion, the LMM can accommodate a covariance structure. The findings of this study provide first evidence of DNA methylation levels in DLGAP2 associated with SCZ with TD in Chinese population. However, TD just showed borderline significant differences to NTD in this study.

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) has a prevalence of approximately 1% worldwide and represents a major public health concern. SCZ is known to be a multifactorial disorder, by the contribution of multiple susceptibility genes, which may interact with epigenetic processes and environmental factors, with a heritability between 60 and 80%1–6. Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a side effect of antipsychotic medications which are used to treat SCZ and other mental health disorders. The prevalence of TD in SCZ can range from 20% to 50%7,8. It has been proposed that the occurrence of TD may be the result of the interactions between genetics, environment, and epigenetics8–11.

Epigenetic changes affect gene expression and function by mechanisms other than those from changes in the DNA sequence; whereas DNA methylation is an important epigenetic modification and involves the addition of a methyl group at the 5th carbon of cytosines preceding guanines (CpG dinucleotides). DNA methylation has been shown to regulate gene expression when implicated in SCZ12–16 and TD17. Pyrosequencing offers a robust, versatile platform yielding rapid quantitative analysis of DNA methylation levels and providing information on the methylation status of single CpG sites18–20.

The DLGAP2 gene (also known as DAP2, SAPAP2, C8orf68, and ERICH1-AS1) is located at 8p23.3 and is highly expressed in the striatum and may play a role in the molecular organization of synapses and in neuronal cell signaling21,22. Recently, DLGAP2 was found to be associated with SCZ23,24 and several single nucleotide variations in DLGAP2 have been reported in SCZ patient cohorts25,26. More recently, a review has focused on the direct and indirect role of the DLGAP family on SCZ as well as other brain diseases27. Regarding methylation, the DLGAP2 gene revealed differences in methylation status when SCZ patients with healthy controls13,14. However, no study has used pyrosequencing to quantify DNA methylation levels of the DLGAP2 gene; in addition, no study has examined the methylation of DLGAP2 gene in TD. Furthermore, the DNA methylation levels using pyrosequencing among CpG sites within a gene may be correlated28. Mixed models (also known as multilevel models or hierarchical models) including both fixed effects and random effects have been developed to deal with correlated data29–33. However, few studies have been found to use mixed models in methylation analysis34–37. In addition, no study has been found to study DNA methylation of DLGAP2 gene in SCZ or TD within the Chinese sample. Therefore, this study sought to quantify DNA methylation levels of DLGAP2 gene in SCZ with or without TD using pyrosequencing and to deal with the possible correlations among 3 CpG sites within the DLGAP2 gene using a linear mixed model (LMM) in a Chinese population.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The demographic and DNA methylation levels among the three groups (TD, NTD and HC) were summarized in Table 1. There were no statistical significances in age (p = 0.993) and sex composition (p = 0.983) among the three groups; whereas there were significant differences in the DNA methylation levels in site 2 and the average of three CpG sites among three groups using GLM (p = 0.0307 and 0.0465, respectively).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of patients and controls.

| Variable | TD group (n = 35) | NTD group (n = 35) | HC group (n = 34) | χ2/F value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/Female | 20/15 | 20/15 | 19/15 | 0.0148 | 0.993 |

| Age (year) | 45.1 ± 12.2 | 44.7 ± 11.2 | 44.4 ± 11.6 | 0.02 | 0.983 |

| DLGAP2 Site 1 | 91.9 ± 2.6 | 91.9 ± 2.0 | 90.4 ± 7.0 | 1.29 | 0.280 |

| DLGAP2 Site 2 | 74.7 ± 4.6 | 73.4 ± 5.0 | 70.8 ± 8.4 | 3.61 | 0.0307 |

| DLGAP2 Site 3 | 94.2 ± 1.3 | 94.3 ± 1.1 | 93.4 ± 4.0 | 1.81 | 0.169 |

| DLGAP2 Average | 86.9 ± 1.6 | 86.5 ± 1.8 | 84.9 ± 6.0 | 3.16 | 0.0465 |

Abbreviations: TD = schizophrenia patients with tardive dyskinesia (TD), NTD = schizophrenia patients without TD, HC = healthy controls, χ2 value is based on the chi-square test, F value is based on the generalized linear model.

Kruskal-Wallis test

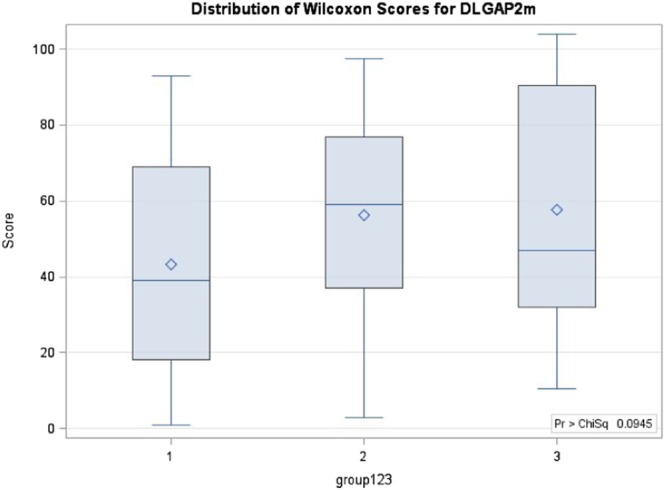

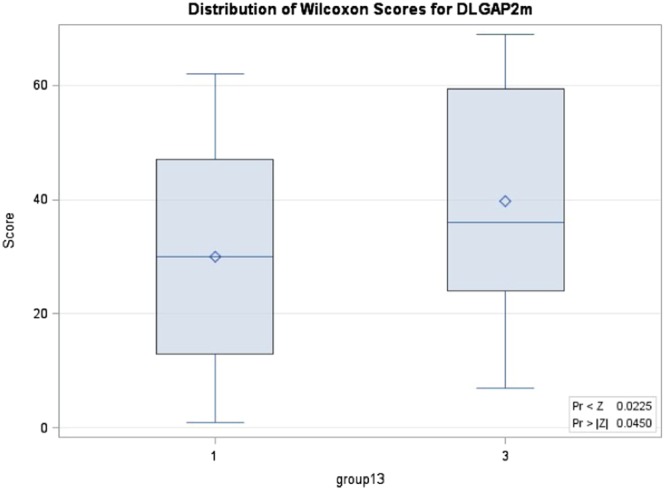

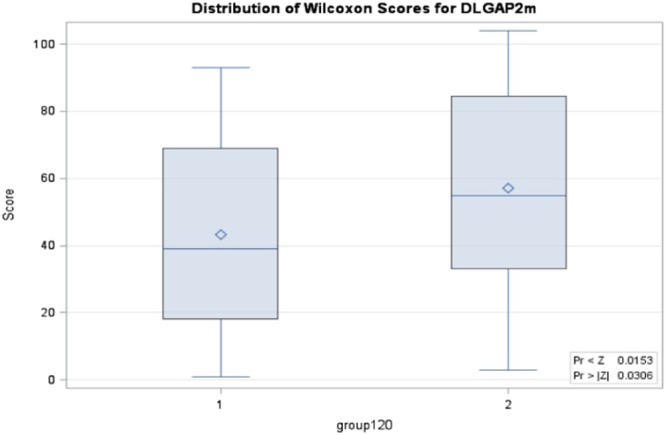

The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed that the three groups had significant differences in DNA methylation level for CpG site 2 (p = 0.0119) and borderline differences for the average DNA methylation level of 3 CpG sites (p = 0.0945) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Furthermore, the Wilcoxon test showed that one-sided p values when comparing the methylation level in site 2 of TD, NTD and ND + NTD with HC group were 0.0038, 0.0252 and 0.0038, respectively; while TD also revealed borderline significance comparing with NTD (p = 0.0559). For CpG site 3, the comparison of TD and ND + NTD groups with the HC group were significant (one-sided p = 0.0161 and 0.0195, respectively). In addition, comparing the average methylation levels of TD, NTD and ND + NTD groups with the HC group, the one-sided p values were 0.0225, 0.0409 and 0.0153, respectively (Table 2, Figs 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Kruskal-Wallis test of methylation levels in DLGAP2 gene.

| Test | Group | Scores/χ2/p value | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KW test | ||||||

| TD | mean score | 57.8 | 62.7 | 58.8 | 57.7 | |

| NTD | 53.0 | 53.3 | 54.7 | 56.2 | ||

| HC | 46.6 | 41.2 | 43.7 | 43.3 | ||

| TD vs NTD vs HC | χ2 | 2.39 | 8.86 | 4.59 | 4.72 | |

| p value | 0.302 | 0.0119 | 0.101 | 0.0945 | ||

| Wilcoxon test | ||||||

| TD vs HC | p value (one-sided) | 0.0716 | 0.0038 | 0.0161 | 0.0225 | |

| p value (two-sided) | 0.143 | 0.0076 | 0.0322 | 0.0450 | ||

| NTD vs HC | p value (one-sided) | 0.17 | 0.0252 | 0.0758 | 0.0409 | |

| p value (two-sided) | 0.34 | 0.0504 | 0.152 | 0.0818 | ||

| TD + NTD vs HC | p value (one-sided) | 0.0828 | 0.0038 | 0.0195 | 0.0153 | |

| p value (two-sided) | 0.1626 | 0.0076 | 0.0389 | 0.0306 | ||

| TD vs NTD | p value (one-sided) | 0.229 | 0.0559 | 0.307 | 0.428 | |

| p value (two-sided) | 0.469 | 0.110 | 0.614 | 0.855 | ||

Abbreviations: TD = schizophrenia patients with tardive dyskinesia (TD), NTD = schizophrenia patients without TD, HC = healthy controls, KW test refers to Kruskal-Wallis test for comparison of 3 groups, mean score is based on the rank, χ2 is based on the chi-square test for the KW test, one sided and two-sided p values are based on the Wilcoxon test for comparison of 2 groups.

Figure 1.

Wilcoxon scores for the average methylation of 3 sites for DLGAP2 gene when comparison of TD vs NTD vs HC. 1 refers to HC, 2 refers to NTD, 3 refers to TD.

Figure 2.

Wilcoxon scores for the average methylation of 3 sites for DLGAP2 gene when comparison of TD with HC. 1 refers to HC, 3 refers to TD. P value of 0.0225 is based on one-side test and 0.0450 is based on two-side test.

Figure 3.

Wilcoxon scores for the average methylation of 3 sites for DLGAP2 gene when comparison of TD + NTD with HC. 1 refers to HC, 2 refers to TD + NTD. P value of 0.0153 is based on one-side test and 0.0306 is based on two-side test.

Correlation analysis

Table 3 shows that there were significant correlations among the DNA methylation levels of 3 CpG sites and the average of 3 CpG sites (all p values < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Correlation analysis.

| Variable | DLGAP2 Site 1 | DLGAP2 Site 2 | DLGAP2 Site 3 | DLGAP2 Average | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLGAP2 Site 1 | 1.000 | 0.480**** | 0.896**** | 0.858**** | −0.161 |

| DLGAP2 Site 2 | 1.000 | 0.495**** | 0.855**** | 0.207* | |

| DLGAP2 Site 3 | 1.000 | 0.848**** | −0.173 | ||

| DLGAP2 Average | 1.000 | 0.0142 |

Abbreviations: *Refers to p < 5% in Persona correlation analysis, ****refers to p < 0.0001 in Persona correlation analysis.

Linear mixed model analysis

Random effect test results are presented in Table 4. Using the default model (the covariance structure is variance components) in the LMM30, the three CpG sites showed significant differences for all comparisons (all p values of random effects were <0.0001) in Table 4. Furthermore, the 3 groups had significant difference in DNA methylation level (p = 0.0027); while CpG sites 1 and 2 showed significant lower DNA methylation levels than in CpG site 3 (t test in Table 5). In addition, TD, NTD and ND + NTD groups showed significant differences from the HC group (p = 0.0042, 0.0151, and 0.0007, respectively) in Table 5.

Table 4.

Random effects using linear mixed models.

| Cov Parm | Estimate | SE | Z value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site for TD vs. NTD vs HC | 0.00309 | 0.000248 | 12.49 | <0.0001 |

| Site for TD vs HC | 0.00387 | 0.000381 | 10.17 | <0.0001 |

| Site for NTD vs HC | 0.00375 | 0.000369 | 10.17 | <0.0001 |

| Site for TD + NTD vs HC | 0.00310 | 0.000248 | 12.49 | <0.0001 |

| Site for TD vs NTD | 0.00166 | 0.000162 | 10.25 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: TD = schizophrenia patients with tardive dyskinesia (TD), NTD = schizophrenia patients without TD, HC = healthy controls, Cov Parm = Covariance Parameter, SE = Standard Error, Z value and p value are based on the Z test for the random effect in the linear mixed models.

Table 5.

Fixed effects using linear mixed models.

| Group | Num DF | Den DF | F/t value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD vs. NTD vs HC | 2 | 101 | 6.26 | 0.0027 |

| Site | 2 | 206 | 871.4 | <0.0001 |

| Site 1 vs 3 | −6.20 | <0.0001 | ||

| Site 2 vs 3 | −38.5 | <0.0001 | ||

| TD vs HC | 1 | 67 | 8.78 | 0.0042 |

| Site | 2 | 136 | 457.74 | <0.0001 |

| Site 1 vs 3 | −4.51 | <0.0001 | ||

| Site 2 vs 3 | −28.16 | <0.0001 | ||

| NTD vs HC | 1 | 67 | 6.22 | 0.0151 |

| Site | 2 | 136 | 501.15 | <0.0001 |

| Site 1 vs 3 | −4.73 | <0.0001 | ||

| Site 2 vs 3 | −29.48 | <0.0001 | ||

| TD + NTD vs HC | 1 | 102 | 12.18 | 0.0007 |

| Site | 2 | 206 | 870.49 | <0.0001 |

| Site 1 vs 3 | −6.20 | <0.0001 | ||

| Site 2 vs 3 | −38.83 | <0.0001 | ||

| TD vs NTD | 1 | 68 | 0.62 | 0.436 |

| Site | 2 | 138 | 1050.4 | <0.0001 |

| Site 1 vs 3 | −6.74 | <0.0001 | ||

| Site 2 vs 3 | 2 | 138 | −42.63 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: TD = schizophrenia patients with tardive dyskinesia (TD), NTD = schizophrenia patients without TD, HC = healthy controls, Num DF refers to the number of degrees of freedom in the model, Den DF refers to the number of degrees of freedom associated with the model errors, F/t value and p value are based on the linear mixed models.

Discussion

In this study, we performed pyrosequencing analysis to determine DLGAP2 gene promoter methylation levels among TD, NTD and HC groups. Both the non-parametric method and LMM revealed significant increases of DNA methylation in TD and NTD groups compared with healthy controls. However, TD showed only borderline significant differences to NTD in CpG site 2 using the Wilcoxon rank test. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the quantitative DNA methylation levels using pyrosequencing in DLGAP2 gene of TD compared to NTD and healthy controls.

Wockner et al.13 performed a genome-wide DNA methylation analysis on post-mortem human brain tissue from 24 patients with SCZ and 24 unaffected controls using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 Bead Chip. They found that the M value = 0.324 (the log2 ratio of the intensities of methylated probe versus unmethylated probe) with p = 0.00035985 (adjusted p = 0.04194) for the DLGAP2 gene as stated in Table S113. Another study reported that DLGAP2 showed a DNA methylation change of −1.13 with p = 4.59 × 10−5 in SCZ14. In the present study we confirmed that SCZ (NTD group) has significant increased DNA methylation levels compared to healthy controls using pyrosequencing. We further added that TD has significant increased DNA methylation levels compared to healthy controls using pyrosequencing. However, TD showed only borderline significant differences to NTD in CpG site 2 in the DLGAP2 using the Wilcoxon rank test.

Previous studies have shown that DLGAP2 may play a role in the molecular organization of synapses and in neuronal cell signaling21. Another study found DLGAP2 is highly expressed in the striatum; however, Dlgap2 is the only Dlgap that is not expressed in the cerebellum and in the thalamus22. Furthermore, genetic association studies have shown that polymorphism in DLGAP2 has been associated with SCZ as well as other brain diseases25–27. However, no study has been found to quantify DNA methylation levels of the DLGAP2 gene using pyrosequencing in NTD and to examine the methylation of DLGAP2 gene in TD. Previous studies suggested that the occurrence of TD may be the result of the interactions between genetics, environment, and epigenetics8–11. Furthermore, it is proposed that antipsychotics are epigenetic modifiers with widespread effects on site-specific and global DNA methylation38. Recently, Zhang et al. (2018) reported the preliminary DNA methylation profiles in SCZ with TD by using methylated DNA immunoprecipitation coupled with next-generation sequencing in a case-control design in a Chinese sample17 and found that 161 genes were specific to TD group; however, the DLGAP2 gene was not reported. The present study provided the first evidence of the DNA methylation levels of the DLGAP2 gene associated with pathogenesis of TD.

Pyrosequencing allows the simultaneous analysis of several CpG sites up to 100 bp amplicon length and offers a robust, versatile platform yielding rapid quantitative results18–20. Previous studies have used the t-test or ANOVA39–41 or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test42–44 to evaluate the differences of DNA methylation levels in single CpG site or the average of several sites among groups. However, the DNA methylation levels among CpG sites within a gene may be correlated28. Our present study also revealed that there were significant correlations among the methylation percentages of 3 CpG sites and the average of 3 CpG sites (p < 0.0001) (Table 3). Ignoring the correlation among sites may cause bias in the relationship. The LMM has been proposed to analyze correlated quantitative data30,31,33; however, only a few studies have used LMM in the analysis of DNA methylation levels34–37. In the present study, we used the LMM to deal with the correlated structures among 3 CpG sites within the DLGAP2 gene and found that the differences in DNA methylation levels among 3 groups were stronger using LMM than using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (Tables 2 and 5).

This study has several strengths. First, we performed the first quantitative analysis of DNA methylation levels of the DLGAP2 gene in SCZ with TD using pyrosequencing. Second, the present study attempted to use LMM in analysis of correlated DNA methylation levels within a gene. However, this study also has some limitations. First, DNA methylation has tissue specificity; however, it is difficult to sample brain tissues for researches on the central nervous system diseases, the biological samples selected here were peripheral blood. Second, we studied limited sites of DLGAP2 methylation (only 3 CpG sites). Third, the sample size is relatively small. We used PROC MIXED in SAS 9.4 to compute power for the three independent groups45,46. Based on our sample size of 104 individuals, the power to detect the difference among overall means for 3 CpG sites could reach 50%; while the power could reach 97% when we just considered CpG site 2. We considered complex designs including random and fixed effects in the LMMs (Tables 4 and 5), the power would then be higher45.

In conclusion the LMM can be used to deal with complex relationships in DNA methylation levels among CpG sites. This study showed increased DNA methylation levels of the DLGAP2 gene in both TD and NTD patients compared to control individuals. However, TD showed only borderline significant differences to NTD in CpG site 2 using the Wilcoxon rank test. Further studies will be essential to examine age, gender and racial effects using LMM and large sample. In addition, further functional analysis of methylation level of these 3 CpG sites of DLGAP2 gene may help to better understand the mechanisms of this gene on the development of SCZ and TD.

Methods

The Chinese sample

This methylation study consists of 35 SCZ patients with TD, 35 SCZ non-TD (NTD) patients and 35 healthy controls (HCs). 70 patients with SCZ were recruited from December 2016 to August 2017 in Beijing HuiLongGuan Hospital (Beijing, China). SCZ was diagnosed using DSM-IV. Clinical diagnoses of TD were confirmed by two highly experienced psychiatrists according to the criteria of Schooler and Kane47. Inclusion criteria for TD group include having ages between 18 and 40 years old; with Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) scored larger than 3 in at least one part or at least 2 in two or more parts. The same criteria were used for NTD group except that AIMS = 0. Patients with any of the following situation were excluded: (1) severe physical or organic encephalopathy; (2) drug or alcohol abuse history (except tobacco); (3) pregnant or lactating women; (4) administration of neurotrophic agents or free radical metabolism drugs within 12 weeks prior to participation; (5) meeting other mental illness diagnosis of DSM-IV Axis I. 35 healthy controls demographically matched for age, sex, and education were enrolled at the same period from the local community.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the individuals were of the Han Chinese ethnicity and live in Beijing. All subjects in the methylation study gave informed consent and were given written instructions to fast overnight before the venous blood sampling. Ethical approval for the methylation study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Beijing HuiLongGuan Hospital. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

DNA extraction and pyrosequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted using a standard genomic DNA sample kit (Illumina) with the concentration and purity detected by NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, USA), and integrity tested using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Pyrosequencing (Pyro-Seq) was used to quantify one or more methylation sites. Pyrosequencing was performed for all the study samples on a PyroMark Q96 ID using Pyro Mark Gold reagents (Qiagen). Primers for DLGAP2, targeting 3 CpGs in the gene promoter, were generated according to Pyro Mark Assay Design software version 2.0 (Qiagen). Primer sequences are listed in Figure S1. Pyromark Q96 ID version 1.0.9 software was used to generate and automatically analyze pyrograms resulting from sequencing onto the PyroMark Q96 ID system. This study includes 3 CpG sites in the DLGAP2 gene. Quantitative methylation results were considered both as percentage of individual CpG sites and as average of the methylation percentage of the 3 investigated CpGs (Figure S2). After quality control, our final sample size consisted of 35 SCZ with TD, 35 SCZ without TD and 34 controls.

Descriptive statistics

The chi-square (χ2) test was used to analyze the gender differences across TD, NTD and HC groups. The age and the differences in the percentage of methylation among TD, NTD and HCs for each CpG site and the average of the methylation percentage of the 3 investigated CpGs were compared using the F test in a generalized linear model (GLM).

Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test

The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was initially used to compare the ranks of the DNA methylation levels for each CpG site and the average of the 3 CpGs among TD, NTD and HC groups. Then the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the observations from any of two groups.

Correlation analysis

Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to test for correlation in methylation percentages among the 3 CpG sites, the average of the 3 CpG sites and age.

Linear mixed models (LMM)

We considered the possible correlations among CpG sites within a gene, then the linear mixed model (LMM) was used30,31,33,48. The LMM included group as the fixed effect and sites as the random effect and was used to examine the DNA methylation differences among groups (1). The PROC MIXED procedure in SAS 9.4 was used to deal with the correlated measures.

| 1 |

where, Yit is the value of the outcome for individual i at site t, μt is an intercept varying with site, xit is a vector of site-varying variables, zi is a vector of site-invariant variables such as gender and race; αi denotes the random effects with each having a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and constant variance, and β are fixed effects. εij is a random distribution term. i = 1, …, Ij is level-1 individual i indicator, and t = 1, 2, 3 is the level-2 indicator such as 3 sites of CpG. Z test was used to examine the random effect; while F test was used to compare DNA methylation levels among groups and t test was used to compare the site effect. Before conducting analysis using LMMs, we performed log transformation of the DNA methylation levels.

All above analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Beijing Liuhe Huada Gene Technology Co LTD for their experiment assistances. The methylation study was supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation [7151005] and the National Science Foundation of China [81771452].

Author Contributions

Y.L., J.H., H.A., F.D.Y. and Y.T. led the study, participated in the planning and management of the project. Y.L., J.H., F.D.Y., Z.W., S.T. and S.C. designed the study and collected the data. Y.L., H.A., Z.W., S.T. and S.C. recruited patients and controls and performed clinical assessment. Y.L., K.S.W., P.Z., N.W. and Y.T. undertook the statistical analysis, interpreted the data and results, managed the literature searches and drafted part of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. All authors approve of the manuscript’s submission.

Availability of Data and Materials

The methylation data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yanli Li and Kesheng Wang contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Kesheng Wang, Email: wangk@etsu.edu.

Yunlong Tan, Email: yltan21@126.com.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-35718-4.

References

- 1.Cannon TD, Kaprio J, Lonnqvist J, Huttunen M, Koskenvuo M. The genetic epidemiology of schizophrenia in a Finnish twin cohort. A population-based modeling study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1998;55:67–74. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PF, Kendler KS, Neale MC. Schizophrenia as a complex trait: evidence from a meta-analysis of twin studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60:1187–1192. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Schizophrenia genetics: uncovering positional candidate genes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;14:512–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll LS, Owen MJ. Genetic overlap between autism, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Genome Med. 2009;1:102. doi: 10.1186/gm102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein P, et al. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet. 2009;373:234–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gejman PV, Sanders AR, Duan J. The role of genetics in the etiology of schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Clin. North. Am. 2010;33:35–66. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarsy D, Lungu C, Baldessarini RJ. Epidemiology of tardive dyskinesia before and during the era of modern antipsychotic drugs. J. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2011;100:601–616. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52014-2.00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correll CU, Kane JM, Citrome LL. Epidemiology, Prevention, and Assessment of Tardive Dyskinesia and Advances in Treatment. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2017;78:1136–1147. doi: 10.4088/JCP.tv17016ah4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Csoka AB, Szyf M. Epigenetic side-effects of common pharmaceuticals: a potential new field in medicine and pharmacology. Med. Hypotheses. 2009;73:770–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HJ, Kang SG. Genetics of tardive dyskinesia. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2011;98:231–64. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381328-2.00010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanning RK, Zai CC, Müller DJ. Pharmacogenetics of tardive dyskinesia: an updated review of the literature. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17:1339–51. doi: 10.2217/pgs.16.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishioka M, Bundo M, Kasai K, Iwamoto K. DNA methylation in schizophrenia: progress and challenges of epigenetic studies. Genome Med. 2012;4(12):96. doi: 10.1186/gm397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wockner LF, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of human brain tissue from schizophrenia patients. Transl. Psychiatry. 2014;4:e339. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hannon E, et al. An integrated genetic-epigenetic analysis of schizophrenia: evidence for co-localization of genetic associations and differential DNA methylation. Genome Biol. 2016;17:176. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1041-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SA, Huang KC. Epigenetic profiling of human brain differential DNA methylation networks in schizophrenia. BMC Med. Genomics. 2016;9(Suppl 3):68. doi: 10.1186/s12920-016-0229-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pries LK, Gülöksüz S, Kenis G. DNA Methylation in Schizophrenia. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017;978:211–236. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-53889-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang P, Li YL, An HM, Tan YL. Preliminary construction of DNA methylation profiles of schizophrenia patients with tardive dyskinesia. Chin. J. Psychiatry. 2018;51:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tost J, Gut IG. DNA methylation analysis by pyrosequencing. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2265–75. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikeska T, Felsberg J, Hewitt CA, Dobrovic A. Analysing DNA methylation using bisulphite pyrosequencing. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;791:33–5. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-316-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fakruddin M, Chowdhury A. Pyrosequencing-An alternative to traditional Sanger sequencing. Am. J. Biochem. Biotech. 2012;8:14–20. doi: 10.3844/ajbbsp.2012.14.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranta S, et al. Positional cloning and characterisation of the human DLGAP2 gene and its exclusion in progressive epilepsy with mental retardation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;8:381–384. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welch JM, Wang D, Feng G. Differential mRNA expression and protein localization of the SAP90/PSD-95-associated proteins (SAPAPs) in the nervous system of the mouse. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;472:24–39. doi: 10.1002/cne.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Havik B, et al. The complement control-related genes CSMD1 and CSMD2 associate to schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;70:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ripke S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:969–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li JM, et al. Exonic resequencing of the DLGAP3 gene as a candidate gene for schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2013;208:84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li JM, et al. Role of the DLGAP2 gene encoding the SAP90/PSD-95-associated protein 2 in schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen AH, Rasmussen HB, Silahtaroglu A. The DLGAP family: neuronal expression, function and role in brain disorders. Mol. Brain. 2017;10(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s13041-017-0324-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kottaridi C, et al. A Pyrosequencing Assay for the Quantitative Methylation Analysis of GALR1 in Endometrial Samples: Preliminary Results. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015:756359. doi: 10.1155/2015/756359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B, Lingsma HF, Steyerberg EW, Lesaffre E. Logistic random effects regression models: a comparison of statistical packages for binary and ordinal outcomes. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011;11:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell, B. A., Ene, M., Smiley, W. & Shonenberger, J. A. A multilevel primer using SAS® PROC MIXED. SAS Global Forum 2013 Proceedings (2013).

- 31.West Brady, Welch Kathleen, Gałecki Andrzej. Linear Mixed Models. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ene, M., Leighton, E. A., Blue, G. L. & Bell, B. A. Multilevel Models for Categorical Data Using SAS® PROC GLIMMIX: The Basics. SAS Global Forum 2015, Dallas, Texas, 2015. Available at http://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings15/3430-2015.pdf (2015).

- 33.Wang KS. Linear and non-linear mixed models in longitudinal studies and complex survey data. J. Biom. Biostat. 2016;7(2):e290. doi: 10.4172/2155-6180.1000290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li-Tempel T, et al. The cardiovascular and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis response to stress is controlled by glucocorticoid receptor sequence variants and promoter methylation. Clin. Epigenetics. 2016;8:12. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0180-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandaviya PR, et al. Genetically defined elevated homocysteine levels do not result in widespread changes of DNA methylation in leukocytes. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0182472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coker ES, Gunier R, Huen K, Holland N, Eskenazi B. DNA methylation and socioeconomic status in a Mexican-American birth cohort. Clin. Epigenetics. 2018;10:61. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0494-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neven KY, et al. Placental promoter methylation of DNA repair genes and prenatal exposure to particulate air pollution: an ENVIRONAGE cohort study. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(4):e174–e183. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ovenden ES, McGregor NW, Emsley RA, Warnich L. DNA methylation and antipsychotic treatment mechanisms in schizophrenia: Progress and future directions. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;81:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JU, Sul HJ, Son JW. Promoter Methylation of CDKN2A, RARβ, and RASSF1A in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma: Quantitative Evaluation Using Pyrosequencing. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2012;73:11–21. doi: 10.4046/trd.2012.73.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoon HY, et al. DNA methylation of GSTP1 in human prostate tissues: pyrosequencing analysis. Korean J. Urol. 2012;53(3):200–5. doi: 10.4111/kju.2012.53.3.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu K, et al. Methylation of S100A8 is a promising diagnosis and prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:56798–56810. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vasiljević N, et al. Absolute quantitation of DNA methylation of 28 candidate genes in prostate cancer using pyrosequencing. Dis. Markers. 2011;30:151–61. doi: 10.1155/2011/157829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bihl MP, Foerster A, Lugli A, Zlobec I. Characterization of CDKN2A(p16) methylation and impact in colorectal cancer: systematic analysis using pyrosequencing. J. Transl. Med. 2012;10:173. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sparrow S, et al. Epigenomic profiling of preterm infants reveals DNA methylation differences at sites associated with neural function. Transl. Psychiatry. 2016;6:e716. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.High, R. An introduction to statistical power calculations for linear models with SAS 9.1. https://www.lexjansen.com/pnwsug/2007/Robin%20High%20-%20Statistical%20Power%20Calculations%20for%20Linear%20Models.pdf (2007).

- 46.Kononoff PJ, Hanford KJ. Technical note: estimating statistical power of mixed models used in dairy nutrition experiments. J. Dairy Sci. 2006;89:3968–71. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schooler NR, Kane JM. Research diagnoses for tardive dyskinesia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1982;39:486–487. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290040080014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bing, D. & He, X. Linear Mixed Models in Clinical Trials using PROC MIXED. https://www.lexjansen.com/pharmasug/2010/SP/SP07.pdf (2010)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The methylation data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.