Abstract

O-linked β-N-acetyl glucosamine modification (O-GlcNAcylation) is a dynamic, reversible posttranslational modification of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins. O-GlcNAcylation depends on nutrient availability and the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP), which produces the donor substrate UDP-GlcNAc. O-GlcNAcylation is mediated by a single enzyme, O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), which adds GlcNAc and another enzyme, O-GlcNAcase (OGA), which removes O-GlcNAc from proteins. O-GlcNAcylation controls vital cellular processes including transcription, translation, the cell cycle, metabolism, and cellular stress. Aberrant O-GlcNAcylation has been implicated in various pathologies including Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, obesity, and cancer. Growing evidences indicate that O-GlcNAcylation plays crucial roles in regulating immunity and inflammatory responses, especially under hyperglycemic conditions. This review will highlight the emerging functions of O-GlcNAcylation in mammalian immunity under physiological and various pathological conditions.

Keywords: Immunity, lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, NF-κB, NFAT, O-GlcNAcylation, OGT, OGA, phosphorylation

Introduction

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) play critical roles in regulating the function of large repertoire of proteins, leading to diverse cellular responses under physiological and pathological conditions. Nearly 200 types of PTMs have been reported and few of them drew attention for extensive studies that revealed their crucial roles in signaling and gene expression viz., phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, sumoylation, ubiquitylation and glycosylation [1]. The most commonly studied glycosylations are N-linked and O-linked glycosylations that are associated with protein secretory pathways. These classical glycosylations occur in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complex, respectively, and form heterogenic complex structures [2]. Until the first report on a unique kind of O-linked glycosylation that occurs in the cytoplasm and nucleus was published in 1984 by Torres and Hart [3], it was thought that glycosylation occurred only in subcellular compartments. While studying the cell surface terminal sugar moieties, Torres et al. discovered that there was a significant amount of terminal N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) that was O-glycosidically linked to intracellular proteins in murine lymphocytes [3]. This study revealed a new kind of posttranslational modification of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins, known as O-GlcNAcylation.

O-GlcNAcylation of transcription factors, mitochondrial proteins, kinases, nuclear proteins, and epigenetic regulators has been shown to play a crucial role in maintaining normal metabolic homeostasis, immune cell maintenance, growth factor signaling, and stem cell biology [4]. Growing evidences suggest a positive correlation between flawed O-GlcNAcylation and diseases such as cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and cardiovascular diseases [5–8]. In 1991, Kearse et al. demonstrated that lymphocyte activation leads to rapid changes in O-GlcNAc modifications of several nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins [9]. Since then, a number of studies have suggested the importance of the O-GlcNAcylation of several cell-signaling proteins involved in regulation of immune functions [10–20]. Suppression of O-GlcNAcylation has been shown to favor activation of the innate immune response [21]. In contrast, elevated O-GlcNAcylation of proteins caused by metabolic stress induced by conditions such as abundance of saturated fat and sugar [11] leads to altered immune cell function and chronic inflammation [20]. Thus, O-GlcNAcylation can have profound effects on the immune system, and may compromise immune responses or lead to hyper responsiveness and sustained inflammation [12–14]. Here, we will summarize the mechanism of O-GlcNAcylation and its implications in various immune functions and immune pathologies.

Dynamics of O-GlcNAcylation

O-GlcNAcylation is the enzymatic addition of an O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc), mostly to the hydroxyl group of a serine and threonine residues in proteins [22, 6]. Similar to phosphate, GlcNAc dynamically modifies serine and threonine residues in target proteins and may compete for binding at the same site where phosphate binds; it may also occur at residues independent of phospho-site. However, unlike negatively charged phosphate groups, the addition of GlcNAc does not alter the charge of the protein that it modifies [23]. O-GlcNAcylation also reportedly occurs at tyrosine and cysteine residues, but knowledge of the physiological functions of these rare non-serine/threonine O-GlcNAcylation is in its infancy [24, 25]. The high-energy compound UDP-GlcNAc serves as the donor substrate for O-GlcNAcylation and is a major product of the Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway (HBP) [26]. The HBP is mainly regulated through the availability of glucose and about 2–5% of glucose entering the cells flows through HBP. Hyperglycemic conditions will result in increased glucose flux through the HBP, leading to increase in UDP-GlcNAc levels and elevated O-GlcNAcylation of substrates [27, 28]. In addition to glucose, other nutrients such as fatty acids, glucosamine, glutamine and uridine also activate the pathway [29]. As such, O-GlcNAcylation acts as a bridge between the metabolic state of a cell and biological signaling events; this has been covered in greater depth in many other reviews [4, 8, 26, 30, 31].

Unlike other post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, which have enzyme families with multiple members dedicated to the fine-tuning of the magnitude and specificity of protein modifications (i.e. kinases, phosphatases, E3 ubiquitin ligases, deubiquitinases), O-GlcNAcylation is catalyzed by the reciprocal activities of only two enzymes: OGT and OGA [6]. While compared to kinases and phosphatases, the study of these two enzymes is comparatively less. Highlighting their biological importance; global knockout of OGT and OGA loss of function yields lethal phenotype in mouse, the former being embryonically lethal [32] and the latter exhibiting perinatal lethality [33]. Conditional deletion of OGT in T cells results in a substantial decrease of T cell numbers in the thymus and periphery, while its deletion in neurons compromises motor function and leads to the death of mice a few days after birth [34]. Conditional deletion of OGA using an oocyte-specific Cre also resulted in perinatal lethality of the animals associated with improper insulin-glucose homeostasis [35].

Currently, there is little known on the exact mechanism by which OGT targets a specific serine and threonine, and more recently, tyrosine [24] and cysteine [25] residues for modification. Knowledge on a motif that results in definitive O-GlcNAcylation at a given site is also limited, although it has been speculated that clustered serines and threonines have a higher chance of being modified than single residues [36]. Computational studies show that targeting by OGT appears to be directed towards intrinsically disordered domains in the substrates [37]. Structural studies using a ternary complex with OGT, UDP, and a peptide substrate showed that OGT first binds UDP-GlcNAc and then interacts with a target protein in order to attach the nucleotide sugar to the hydroxyl group of target amino acids [38] via an ordered bi-bi catalytic mechanism [39]. OGT possesses three splice forms, which alter its cellular localization: nucleocytoplasmic (ncOGT), short (sOGT), and mitochondrial (mOGT), each with slightly different affinities and kinetics attributed to the varied length of their tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) arm [40]. The TPR region of OGT has been shown to form a superhelix [41], which is more than 130 Å in length and roughly 17 Å in width and 25 Å in depth, facilitating interaction with a broad range of substrates [42]. The large concave inner surface of the superhelix contains several asparagine, arginine, and glutamine residues, and it has been shown that a conserved asparagine ladder in this region plays a major role in substrate recognition by OGT [43].

OGA, which removes O-GlcNAc moieties from proteins, is OGT’s counterpart enzyme [44, 45]. It is also a nucleocytoplasmic enzyme with two isoforms: a full-length and a short version (OGA-L and OGA-S, respectively) with differential localization [46]. Both isoforms are capable of hydrolyzing O-GlcNAc from their bonded residues in protein in the nucleus and cytoplasm, albeit with OGA-S doing so less efficiently [47]. Both OGA-L and OGA-S are dependent solely on the presence of the sugar moiety in question and perform this removal with stable kinetics regardless of the protein, in contrast to OGT’s kinetics, which are highly variable depending on the protein target [47]. The long isoform of OGA also contains a histone acetyl transferase (HAT)-like domain in the C-terminus; however, the function of this acetyltransferase activity is yet to be established in physiologically relevant conditions [48–50].

O-GlcNAcylation shares many of its principal characteristics with phosphorylation. Both modifications tend to be occurring rapidly and transiently [51, 52]. Additionally, both modifications have been observed on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues [52, 24]. As a result of having similar molecular targets, there is has been an abundant amount of crosstalk observed between the two modifications, with residues being competitively or adjacently targeted to varying effects [52–56]. This dynamic interplay between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation allows for nutrient-dependent alterations of signaling output, allowing for a striking metabolic effect on well-studied molecular pathways [57, 58].

Role of O-GlcNAcylation in the Immune System

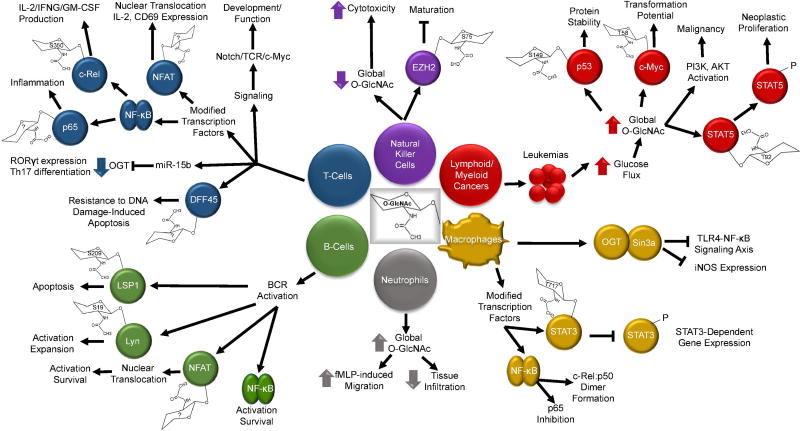

O-GlcNAcylation plays a fundamental role in cellular signal transduction and cellular responses, and several reviews have covered the role of O-GlcNAcylation in various cellular systems [4, 59]. This review is focused on the role of O-GlcNAcylation in the cells involved in innate and adaptive immune responses. The innate immune system constitutes the first line of non-specific defense against invading pathogens and it primarily includes monocytes, macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils. Notably, the role of O-GlcNAcylation in the immune system is evolutionarily conserved, and lack of OGT function has been shown to compromise innate immune response to pathogenic bacteria in Caenorhabditis elegans [60]. The adaptive immune system constitutes the specific defense against a given antigen and is comprised of T and B lymphocytes. Other leukocytes such as natural killer cells [61] and dendritic cells [62] play significant roles both in innate and adaptive immune responses. Protein O-GlcNAcylation has been reported in several of these immune cell types. The metabolic changes and cellular stress that accompany different pathological condition can act as a driving force behind dysregulated O-GlcNAcylation in the immune cells. Here, we will highlight the known functions of O-GlcNAcylation categorized based on the immune cell type it occurs in as well as touch briefly on immune cell malignancy (summarized in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the role of O-GlcNAcylation in the immune system. Model shows the immune cells in which O-GlcNAcylation has been reported, the modified proteins, and their functions. Aberrant O-GlcNAcylation in leukemia and the transcription factors involved in it are also shown. Known O-GlcNAcylation sites are marked inside the O-GlcNAc structure attached to the respective proteins. Phosphorylation (P), Inhibition (⟞), Increase (⬆), Decrease (⬇).

Monocytes and Macrophages

Macrophages and their monocyte precursors are mononuclear, agranular leukocytes that are critical components of the innate immune response, tissue homeostasis, and development. They play key roles in proinflammatory responses and phagocytosis [63]. O-GlcNAcylation in macrophages has been studied the most of all the myeloid-lineage immune cells, but still has not received nearly as much attention as their lymphoid lineage counterparts. OGT can act as a direct transcriptional regulator through its interaction with Ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes such as TET1, TET2 and TET3 [64, 65] as well as via interaction with certain transcription factors, such as the corepressor, mSin3a [66]. Through the interaction with mSin3a, OGT is able to interfere with LPS-driven NF-κB activation and iNOS gene expression in macrophages [67]. O-GlcNAcylation was also shown to regulate the NF-κB subunit c-Rel in microglia, which, similar to resident macrophages, mediate innate immune response in the central nervous system. O-GlcNAcylation drives the formation of the c-Rel-p50 heterodimer, a process that is LPS-sensitive, and a blockade of O-GlcNAcylation was shown to attenuate the activation of c-Rel by LPS and thus iNOS production [68]. Interestingly, the effect of O-GlcNAcylation on c-Rel and p65 was different in microglia, and hyper O-GlcNAcylation was shown to inhibit NF-κB p65 signaling and modulate macrophage polarization, consequently offering neuroprotection in experimental stroke models [69]. Consistent to the inhibitory role of O-GlcNAcylation in p65 activation, studying septic inflammation, Li et al. showed that myeloid specific deletion of OGT results in heightened NF-κB signaling and cytokine production following stimulation by various TLR agonists in macrophages [21]. In line with this, stimulation of TLR4 has been shown to decrease O-GlcNAcylation in macrophages. Additionally, mice with OGT deficient myeloid cells exhibited increased vulnerability to LPS-mediated endotoxin shock and cecal ligation puncture-induced sepsis [21]. These in vivo findings suggest that O-GlcNAcylation, in general, may have an anti-inflammatory role in macrophages. In contrast, Ryu et al. showed that OGT activity is suppressed by S-nitrosylation and LPS activation of macrophages leads to denitrosylation of OGT and enhanced cellular protein O-GlcNAcylation. Experimental inhibition of cellular O-GlcNAcylation results in suppression of LPS-induced macrophage inflammatory response [70]. To add to this paradox, it has also been reported that LPS-induced c-Rel activation decreases under hyperglycemic condition along with its decreased O-GlcNAcylation. Supplementation of glucosamine was found to enhance c-Rel O-GlcNAcylation and binding to the iNOS promoter under low glucose environment, but not under high glucose environments. This is in consistent with the study by Hwang et al. that showed c-Rel O-GlcNAcylation-dependent iNOS production in microglia [68], but adds an additional parameter, the glycemic status of the cell, in dictating O-GlcNAcylation-mediated transcriptional response in macrophages [71].

O-GlcNAcylation has also been shown to be involved in the STAT-signaling pathway in macrophages. O-GlcNAcylation of STAT3 at threonine 717 has been shown to negatively regulate its phosphorylation and STAT3-dependent gene expression. STAT3 O-GlcNAcylation is further regulated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cullin3, which suppresses OGT expression, and nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (NRF2), which has the potential to enhance OGT transcription [72]. The overall effect of STAT3 O-GlcNAcylation seems to increase proinflammatory signaling, which poses targeting of STAT3 O-GlcNAcylation as a potential strategy to control inflammation.

Thus, the current knowledge suggests that the role of O-GlcNAcylation in myeloid cells is complex, having both positive and negative regulatory effects on inflammation. These differential effects may be attributed to factors such as glucose availability, which determines the O-GlcNAcylation status of cellular proteins at the time of insult as well as the availability of UDP-GlcNAc for stimulus-dependent de novo O-GlcNAcylation. Factors such as the difference in the microenvironment of the locus of inflammation (central nervous system v/s large intestine), as well as the type of the key responder molecule that is mainly modified by O-GlcNAcylation (NF-κB v/s STAT) and within the NF-κB family (p65 v/s c-Rel), may largely influence the outcome of O-GlcNAcylation.

Neutrophils

Neutrophils constitute the majority of leukocytes. They are part of the innate immune system and help to fight infection by phagocytosis as well as by releasing antimicrobial factors. Neutrophils are the first responders to reach the site of infection or injury. Directional migration and rapid cellular motility are two key features of neutrophils that enable them to execute their function. Kneass et al. have demonstrated that O-GlcNAcylation plays a crucial role in neutrophil signal transduction in the context of chemotaxis [73]. They showed that elevation of O-GlcNAcylation either by treating cells with glucosamine or PUGNAc (OGA inhibitor), increases both basal and chemotactic peptide formylated Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) induced neutrophil migration [74]. These studies suggest that neutrophils contain active O-GlcNAcylation pathways; however, the exact molecular entities affected by this modification remain unknown. Preliminary evidences presented in this study allude to the involvement of several cellular pathways, including PI3K, Rho family GTPase, Rac, p38 kinase and ERK1/ERK2, in O-GlcNAcylation-dependent regulation of neutrophil function [74].

However, none of these proteins have yet been demonstrated to be O-GlcNAcylated in neutrophils. Thus, O-GlcNAcylation-dependent neutrophil-mediated regulation of innate immune response continues to be a blind spot warranting further investigation. Interestingly, it has been shown that stimulation of neutrophils with the chemotactic agent fMLF results in rapid enhancement of protein O-GlcNAcylation [75]. This shows that O-GlcNAcylation is inducible in neutrophils and may play an essential role in controlling dynamic neutrophil activity. Detailed studies on the role of O-GlcNAcylation in neutrophils may be hampered due to their delicate nature and short ex vivo lifespan [75]. In contrast to the studies correlating O-GlcNAcylation with enhancement of neutrophil directional migration and chemotaxis [74], it has also been suggested that hyper-O-GlcNAcylation may reduce neutrophil accumulation in injured tissue. A study using the trauma-hemorrhage (T-H) model found that tissue myeloperoxidase level, used as a marker of neutrophil infiltration, was significantly elevated in control groups compared to glucosamine or PUGNAc treated groups [76]. Thus, it is imperative to study the dynamics of O-GlcNAcylation in neutrophils using optimal assay methods and multiple mouse models, as well as identifying key O-GlcNAcylated proteins to fully understand the undoubtedly important role O-GlcNAcylation plays in the initial phases of innate immune response and inflammation.

T Cells

T cells are central in cell-mediated immune responses and are part of the adaptive immune system. Of all the immune cells, T cells have been the most extensively studied in relation to O-GlcNAcylation. O-GlcNAcylation was found essential for T cell survival, and conditional deletion of OGT using Lck-Cre in T cells was shown to induce massive apoptosis, decreasing T cell numbers both in the thymus as well as in the periphery [34]. O-GlcNAcylation of key signaling proteins such as Nuclear Factor of Activated T cells (NFAT) and Nuclear Factor kappaB (NF-κB) have been shown to impart significant effects on cellular behavior, fate, and function in T cells [10]. NFAT is a transcription factor that induces several genes critical for T cell development, differentiation, proliferation, and function [77]. It has been shown that T cell receptor (TCR) activation rapidly induces O-GlcNAcylation of NFATc1 in the cytoplasm at 5 minutes after stimulation, and that the O-GlcNAcylated NFAT is observable in the nucleus at later time points [10]. This suggests that O-GlcNAcylation of NFAT may be required for its nuclear translocation; however, additional evidence is required to confirm this, such as identification of O-GlcNAcylation site(s) in NFAT and mutational studies. Further confirming the role of O-GlcNAcylation in T cells, suppression of OGT has been shown to decrease TCR-induced interleukin-2 (IL-2) production as well as expression of the activation marker CD69 [10]. One can thusly speculate that hyper-O-GlcNAcylated NFAT in hyperglycemic conditions could drive pathological over-activation of T lymphocytes.

NF-κB activation also plays an important role in T cells; especially T regulatory (T reg) cell development and T lymphocyte function [78]. Golks et al. showed that, similar to NFAT, suppression of OGT also affects NF-κB activity in T cells; they also demonstrated that NF-κB subunit p65 is modified by O-GlcNAcylation [10]. We focused on studying NF-κB subunit c-Rel and found that hyperglycemic conditions and glucosamine treatment enhances O-GlcNAcylation of c-Rel at serine residue 350 in T cells [79]. This site-specific O-GlcNAcylation of c-Rel was found to enhance its binding at the CD28RE region, which drives expression of proinflammatory molecules such as IL-2, interferon gamma (IFNG), and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). As a result, treatment of T cells with high glucose or PUGNAc was found to increase TCR-induced expression of these genes, and blocking O-GlcNAcylation decreased their expression [79]. Interestingly, quantification of c-Rel O-GlcNAcylation using a mass-tag strategy showed that only a small fraction of c-Rel (about 5%) was O-GlcNAcylated at any given time in T cells. Under hyperglycemic conditions, this pool of O-GlcNAcylated c-Rel increases up to 5-fold, exacerbating the pro-inflammatory activation program downstream of the TCR receptor, which may drive destructive T cell-mediated inflammation [79]. In an earlier study, we found glucose as a necessary nutrient that promoted the survival of double positive (DP) thymocytes [80]. Hyperglycemia was found to activate the induction of NF-κB p65-dependent antiapoptotic genes in DP thymocytes that facilitates their survival, which was observed both in mouse and human thymocytes [80]. NF-κB p65 has been shown to be O-GlcNAcylated at threonine 305, serine 319, threonine 322, serine 337, threonine 352 and serine 374 [81, 82], but which of these sites are modified in T cells remains to be examined. Because hyperglycemia promotes survival of DP thymocytes [80] and enhances cellular O-GlcNAcylation and p65 has been shown to be O-GlcNAcylated in T cells [10], whether p65 O-GlcNAcylation plays a role in induction of NF-κB-dependent antiapoptotic genes in T cells remains an interesting question to be addressed. O-GlcNAcylation may also protect T cells from apoptotic cell death by alternate means. It has been shown that O-GlcNAcylation of DNA Fragmentation Factor 45 (DFF45) confers resistance to its cleavage by caspases during DNA damage-induced apoptosis in T cells and protect from death [83].

Through a proteomic approach, Lund et al. has identified 214 TCR-induced O-GlcNAcylated proteins in T cells. A large number of these O-GlcNAcylated proteins in T cells were associated with RNA metabolism and OGT function was found essential for T cell effector function [17]. In a comprehensive study, Swamy et al. showed that loss of O-GlcNAcylation blocks self-renewal, clonal expansion as well as malignant transformation of T cells [84]. Importantly, this study showed that O-GlcNAcylation is increased in activated T cells, and signaling through Notch, TCR, and c-Myc are involved in O-GlcNAcylation-dependent regulation of T cell development and function. O-GlcNAcylation in T lymphocytes is not only regulated through posttranslational events, but also at posttranscriptional level. In an interesting study, Liu et al. has identified microRNA-15b (miR-15b) as a regulator of OGT expression and suggested a role for O-GlcNAcylation in Th17 cell-dependent autoimmunity. They demonstrated that overexpression of miR-15b blocks Th17 cell differentiation, possibly through blocking OGT expression, and thereby blocks NF-κB O-GlcNAcylation and NF-κB-dependent retinoic acid-related orphan receptor gamma t (RORγt) expression [85]. Thus, it appears that O-GlcNAcylation plays a fundamental role in T lymphocyte biology acting as signal router that wires metabolic cues with T lymphocyte development and activation.

B cells

B cells mediate humoral immunity and are part of the adaptive immune system. Unlike T cells, there is significant paucity of research on the role of O-GlcNAcylation in B cells, with much speculation and correlation being made regarding the impact of hyperglycemia on B cell fate and function. In a proteomic study, Wu et al. showed that there are a substantial number of 313 O-GlcNAcylation-dependent phosphorylation sites on 224 phosphoproteins in B cells that are subjected to modification following BCR activation [16]. This study provides a big picture overview of the essential role of O-GlcNAcylation and its interplay with phosphorylation in regulating B cell fate. They also identified that O-GlcNAcylation of the lymphocyte-specific-protein-1 (LSP1) at serine 209 is required for its phosphorylation at serine 243 and initiation of apoptosis after BCR stimulation. Targeted deletion of OGT from pre-B cells was reported to result in defective B cell receptor (BCR) and B cell activating factor (BAFF) signaling and enhanced apoptosis of mature B cells. Providing mechanistic insight, O-GlcNAcylation of the kinase Lyn at serine 19 was shown to be essential for its interaction with the kinase Syk in the cascade and proper BCR signaling. This study also showed that O-GlcNAcylation in B cells is required for B cell memory as well as antibody production [18]. Similar to T cells, the transcription factors NF-κB and NFAT regulate the expression of several genes necessary to normal B cell survival and function, and are constitutively activated in B cell malignancies [86, 87]. Golks et al. showed that both NF-κB and NFAT are O-GlcNAcylated in B cells, which enhances their transcriptional activity and O-GlcNAcylation was also shown to promote B cell activation [10]. The detection of over 300 O-GlcNAcylated proteins in B cells [16] provides a strong rationale for further detailed studies to understand the role of O-GlcNAcylation in B cells in relation to antibody production, antigen presentation, cytokine expression, and B cell malignancy.

Natural Killer Cells

Natural killer (NK) cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes that function both in innate and adaptive immune responses. NK cells make up a small fraction of total peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and have a small limit of expansion, the combination of which adds up to an investigative hurdle to exploring their biochemistry and proteomics. Yao et al. showed that O-GlcNAcylation decreases during NK cell cytotoxicity and has been suggested to involve in signal transduction in NK cells [88]. The inhibition of histone methyl transferase activity of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) has been shown to enhance the generation of mature NK cells from progenitor cells [89]. An epigenetic role for OGT in O-GlcNAcylation of EZH2 at serine 75 (which is critical for EZH2 protein stability) has been reported, which suggests a link between O-GlcNAcylation and NK cell development and function [90]. These studies point to the idea that dysregulation of O-GlcNAcylation in NK cells may very well impair their ability to guard the body against both foreign pathogens as well as malignant cells.

O-GlcNAcylation in Lymphoid and Myeloid Cancers

Cancers have an altered metabolic profile and most cancers have elevated glycolytic activity [91]. This results in enhanced glucose flux, which in turn will increase HBP activity and O-GlcNAcylation [92]. Thus it is unsurprising that aberrant O-GlcNAcylation has been observed in a number of cancers and is correlated with malignant transformation [93–96]. O-GlcNAcylation has been observed on key tumor suppressors, such as p53 at site S149, which leads to the stabilization of the protein [97]. It has also been reported on certain oncogenes, such as c-Myc at threonine 58, which is a highly mutated residue in lymphomas that is associated with transformation and malignancy [15]. Suppressing O-GlcNAcylation limits oncogenesis, and increase in O-GlcNAcylation through increase in OGT and decrease in OGA function, supports oncogenesis [98]. Here we will briefly cover the current understanding of O-GlcNAcylation’s role in driving immune cell cancers.

The current extent of the research of O-GlcNAcylation in immune cell cancers is largely limited to leukemias. Cellular O-GlcNAcylation significantly increases in Chronic Lymphoid Leukemia (CLL) and is suggested to contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease. Compared to normal circulating B cells, increased O-GlcNAcylation of p53, protein kinase B (AKT), and c-Myc has been observed in CLL cells [99]. Similarly, pre-B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia (preB ALL) cells also display increased O-GlcNAcylation along with upregulated OGT and downregulated OGA expression, as well as enhanced PI3K, AKT, and c-myc activation [100]. Specific O-GlcNAcylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) at threonine 92 has been reported both in CLL and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells. STAT5 O-GlcNAcylation at T92 enhances its tyrosine phosphorylation and promotes neoplastic proliferation of myeloid cells [101]. Although these studies suggest O-GlcNAcylation exerts a pro-oncogenic role in leukemia, in contrast with this, inhibition of OGA was reported to be effective in sensitizing human leukemia cell lines in culture to the chemotherapeutic drug paclitaxel [102]. While this OGA inhibition appears to be promising as a therapy, this also suggests that cycling of O-GlcNAcylation is critical and that arresting proteins in an O-GlcNAcylated state may yield counterproductive outcomes. There is also a study discussing HBP targeting in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) [103], but the identity of specific O-GlcNAcylated protein targets involved in DLBCL remains unknown.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The dynamics of O-GlcNAcylation are linked to glucose metabolism, and its function has important implications in the immune system. Thus, O-GlcNAcylation appears to act as a connecting link between the metabolic status of the cell, especially the glycemic status, and the immune response, and function as a regulator of immunometabolism. The metabolism-dependent regulation of cellular function is a hallmark of cancer cells, described as the Warburg effect, that show increased glucose uptake and enhanced aerobic glycolysis. Several studies show that inflammatory macrophages mediating innate immune response, T cells mediating adaptive immune response, and endothelial cells that modulate the function of immune cells all undergo metabolic reprogramming toward increased glycolysis to favor their function [104]. The increased glucose flux also results in increased O-GlcNAcylation of proteins [92], which wires the effect of metabolic reprogramming into the proliferation of cancer cells or function of the cells in the immune system. Based on the studies conducted so far, it has been established that various proteins, especially transcription factors regulating the immune system such as the NF-κB and NFAT families, as well as proteins in the T cell receptor (TCR), B cell receptor (BCR), and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling cascades, undergo enhanced O-GlcNAcylation under hyperglycemic conditions. This may lead to chronic inflammatory responses in metabolic disorders associated with type 1 and type 2 diabetes as well as obesity. There are also instances where increased O-GlcNAcylation has been demonstrated to be beneficial in minimizing inflammatory responses; for example, Xing et al. demonstrated that increased O-GlcNAcylation inhibits inflammatory and neointimal responses to acute endoluminal arterial injury [11]. Additionally, another study conducted by the same group established that O-GlcNAcylation of NF-κB p65 help suppress TNF-induced inflammatory stress [105]. As such, it is highly desirable to know the specific circumstances and mechanisms through which O-GlcNAc modification acts as promoter or inhibitor of inflammation. These contrasting effects may stem from a cell-type-specific or pathway-specific role of O-GlcNAcylation. It will be informative to examine whether a particular O-GlcNAcylation site in a protein that is modified in one cell type is not modified at that same site in another cell type, or whether a protein functioning in a particular pathway is differentially regulated by O-GlcNAcylation in different cell types. Our study shows that c-Rel is O-GlcNAcylated at serine 350 in lymphocytes, but this modification was hardly detectable in human embryonic kidney 293T cells or mouse embryonic fibroblasts [79]. Similarly, a cell-type-specific role of O-GlcNAcylation has been reported in the regulation of phosphorylation of the AKT and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) kinases. It was shown that O-GlcNAcylation alters phosphorylation of AKT at threonine 308 and 473 residues and GSK-3β at serine 9 residue in human embryonic kidney cell line, HEK293FT, yet not in human hepatocarcinoma cell line, HepG2 [106]. Hence, detailed studies are imperative to decipher the cell-type-specific regulatory role of O-GlcNAcylation in various immune cells.

One of the bottlenecks in hastening O-GlcNAcylation research in mammalian immunity is the limited availability of user-friendly, effective technology ideal for the detection of O-GlcNAcylation site(s) in target proteins. Several approaches and techniques developed by various laboratories have contributed to our current understanding of O-GlcNAcylation. Several antibodies and lectins are available for the initial biochemical detection of O-GlcNAcylated proteins, and labeling approaches using tritiated galactose and Edman sequencing are routinely employed for O-GlcNAc site mapping [23]. Approaches such as click chemistry-based tagging [107], and poly-ethylene-glycol-based mass tagging are also employed for the identification and quantification of the stoichiometry of O-GlcNAcylation [108], respectively. Recent instrumentation advances in mass spectrometry (MS) techniques such as collision-induced dissociation (CID), high-energy collision dissociation (HCD), and electron transfer dissociation (ETD), and their coupling abilities such as CID/ETD-MS/MS or HCD/ETD-MS/MS (along with the use of improvised mass analyzers) as well as high resolution native mass spectrometry are also substantially contributing to O-GlcNAcylation site mapping [54, 36, 109]. As a result of this surge in the development of technologies targeted to identify O-GlcNAcylation, the number of O-GlcNAcylated proteins identified in human cells has increased from few hundreds a decade ago to over 4,000, and this list is growing [23].

It remains rather unclear how negatively charged phosphate competes with uncharged O-GlcNAc moiety for binding to same serine or threonine residue, or how the kinases and OGT win the race to bind to the substrate protein. Is there any minimal structural requirement that constitute the binding site(s) for OGT and OGA? Do OGT and OGA interact directly with the substrate, or do they need any accessory proteins to accomplish cycling of O-GlcNAcylation? How does only a pair of enzymes – OGT and OGA – target thousands of proteins? These are important questions to address in order to understand the molecular mechanisms regulating O-GlcNAcylation. Such knowledge will aid in the design of agents for specific targeting of O-GlcNAcylation-dependent signaling. Because O-GlcNAcylation is directly associated with hyperglycemia, specific targeting of O-GlcNAcylation could be a therapeutic approach to minimize complications associated with conditions such as diabetes and obesity. It will also contribute to design novel strategies to control proliferation of cancer cells, which show enhanced glucose consumption and O-GlcNAcylation.

As discussed above, among all immune cells, O-GlcNAcylation is best studied in T cells. Only a little is known about the role of O-GlcNAcylation in leukocyte trafficking and macrophage function; the rest of its role is almost an enigma in the other components of innate immune system. There are multiple reports on the role of O-GlcNAcylation in signal-transducing molecules including nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2) [110], TGF-beta activated kinase 1 (TAB1) [12], and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV (CaMKIV) [14], among several others, which play key roles in innate and adaptive immune signaling. However, studies showing O-GlcNAcylation-dependent function of these proteins in the immune cells are lacking. There is also an urgent need for studies to understand the role of O-GlcNAcylation in dendritic cells, NKT cells, basophils, eosinophils, mast cells, and innate lymphoid cells to see the big picture role of O-GlcNAcylation in the immune system.

Highlights.

O-GlcNAcylation of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins in immune cells regulates immune response.

O-GlcNAcylation acts as a connecting link between metabolism and immunity.

Targeting O-GlcNAcylation-dependent immune cell signaling may prove effective in treating immune disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the NIH/NIAID grant 1R01AI116730-01A1 to P.R. T.J.D is supported by Dermatology T32 pre-doctoral fellowship, NIH/NIAMS 5T32AR007569-23. We thank Ms. Erin O’Kelly for proofreading the article.

Abbreviations

- GlcNAc

N-acetyl glucosamine

- HBP

Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway

- NF-κB

Nuclear Factor Kappa in B cells

- NFAT

Nuclear Factor of Activated T cells

- O-GlcNAc

O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosamine

- OGA

O-GlcNAcase

- OGT

O-GlcNAc transferase

- PUGNAc

O-(2-Acetamido-2-deoxy-D-glucopyranosylidenamino) N-phenylcarbamate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Duan G, Walther D. The roles of post-translational modifications in the context of protein interaction networks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyons JJ, Milner JD, Rosenzweig SD. Glycans Instructing Immunity: The Emerging Role of Altered Glycosylation in Clinical Immunology. Front Pediatr. 2015;3:54. doi: 10.3389/fped.2015.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres CR, Hart GW. Topography and polypeptide distribution of terminal N-acetylglucosamine residues on the surfaces of intact lymphocytes. Evidence for O-linked GlcNAc. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:3308–3317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bond MR, Hanover JA. A little sugar goes a long way: the cell biology of O-GlcNAc. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:869–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201501101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanover JA. Glycan-dependent signaling: O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. FASEB J. 2001;15:1865–1876. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0094rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart GW, Housley MP, Slawson C. Cycling of O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine on nucleocytoplasmic proteins. Nature. 2007;446:1017–1022. doi: 10.1038/nature05815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefebvre T, Dehennaut V, Guinez C, Olivier S, Drougat L, Mir AM, Mortuaire M, Vercoutter-Edouart AS, Michalski JC. Dysregulation of the nutrient/stress sensor O-GlcNAcylation is involved in the etiology of cardiovascular disorders, type-2 diabetes and Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bond MR, Hanover JA. O-GlcNAc cycling: a link between metabolism and chronic disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2013;33:205–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kearse KP, Hart GW. Lymphocyte activation induces rapid changes in nuclear and cytoplasmic glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1701–1705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golks A, Tran TT, Goetschy JF, Guerini D. Requirement for O-linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase in lymphocytes activation. EMBO J. 2007;26:4368–4379. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing D, Feng W, Not LG, Miller AP, Zhang Y, Chen YF, Majid-Hassan E, Chatham JC, Oparil S. Increased protein O-GlcNAc modification inhibits inflammatory and neointimal responses to acute endoluminal arterial injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H335–342. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01259.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pathak S, Borodkin VS, Albarbarawi O, Campbell DG, Ibrahim A, van Aalten DM. O-GlcNAcylation of TAB1 modulates TAK1-mediated cytokine release. EMBO J. 2012;31:1394–1404. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chikanishi T, Fujiki R, Hashiba W, Sekine H, Yokoyama A, Kato S. Glucose-induced expression of MIP-1 genes requires O-GlcNAc transferase in monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394:865–870. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dias WB, Cheung WD, Wang Z, Hart GW. Regulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV by O-GlcNAc modification. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21327–21337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou TY, Hart GW, Dang CV. c-Myc is glycosylated at threonine 58, a known phosphorylation site and a mutational hot spot in lymphomas. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18961–18965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu JL, Wu HY, Tsai DY, Chiang MF, Chen YJ, Gao S, Lin CC, Lin CH, Khoo KH, Chen YJ, Lin KI. Temporal regulation of Lsp1 O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation during apoptosis of activated B cells. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12526. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lund PJ, Elias JE, Davis MM. Global Analysis of O-GlcNAc Glycoproteins in Activated Human T Cells. J Immunol. 2016;197:3086–3098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu JL, Chiang MF, Hsu PH, Tsai DY, Hung KH, Wang YH, Angata T, Lin KI. O-GlcNAcylation is required for B cell homeostasis and antibody responses. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1854. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01677-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marth JD, Grewal PK. Mammalian glycosylation in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:874–887. doi: 10.1038/nri2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baudoin L, Issad T. O-GlcNAcylation and Inflammation: A Vast Territory to Explore. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:235. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Gong W, Li L, Wen H. Downregulation of the O-GlcNAc signaling promotes activation of the innate immune response in microbial sepsis. The Journal of Immunology. 2017;198:70.78–70.78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart GW, Akimoto Y. The O-GlcNAc Modification. In: Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Freeze HH, Stanley P, Bertozzi CR, Hart GW, Etzler ME, editors. Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor (NY): 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma J, Hart GW. O-GlcNAc profiling: from proteins to proteomes. Clin Proteomics. 2014;11:8. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-11-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jank T, Eckerle S, Steinemann M, Trillhaase C, Schimpl M, Wiese S, van Aalten DM, Driever W, Aktories K. Tyrosine glycosylation of Rho by Yersinia toxin impairs blastomere cell behaviour in zebrafish embryos. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7807. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maynard JC, Burlingame AL, Medzihradszky KF. Cysteine S-linked N-acetylglucosamine (S-GlcNAcylation), A New Post-translational Modification in Mammals. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15:3405–3411. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M116.061549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buse MG. Hexosamines, insulin resistance, and the complications of diabetes: current status. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E1–E8. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00329.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanover JA, Lai Z, Lee G, Lubas WA, Sato SM. Elevated O-linked N-acetylglucosamine metabolism in pancreatic beta-cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;362:38–45. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akimoto Y, Kreppel LK, Hirano H, Hart GW. Hyperglycemia and the O-GlcNAc transferase in rat aortic smooth muscle cells: elevated expression and altered patterns of O-GlcNAcylation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;389:166–175. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teo CF, Wollaston-Hayden EE, Wells L. Hexosamine flux, the O-GlcNAc modification, and the development of insulin resistance in adipocytes. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2010;318:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatham JC, Marchase RB. Protein O-GlcNAcylation: A critical regulator of the cellular response to stress. Curr Signal Transduct Ther. 2010;5:49–59. doi: 10.2174/157436210790226492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chatham JC, Not LG, Fulop N, Marchase RB. Hexosamine biosynthesis and protein O-glycosylation: the first line of defense against stress, ischemia, and trauma. Shock. 2008;29:431–440. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3181598bad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shafi R, Iyer SP, Ellies LG, O'Donnell N, Marek KW, Chui D, Hart GW, Marth JD. The O-GlcNAc transferase gene resides on the X chromosome and is essential for embryonic stem cell viability and mouse ontogeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5735–5739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100471497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang YR, Song M, Lee H, Jeon Y, Choi EJ, Jang HJ, Moon HY, Byun HY, Kim EK, Kim DH, Lee MN, Koh A, Ghim J, Choi JH, Lee-Kwon W, Kim KT, Ryu SH, Suh PG. O-GlcNAcase is essential for embryonic development and maintenance of genomic stability. Aging cell. 2012;11:439–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Donnell N, Zachara NE, Hart GW, Marth JD. Ogt-dependent X-chromosome-linked protein glycosylation is a requisite modification in somatic cell function and embryo viability. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1680–1690. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1680-1690.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keembiyehetty C. Disruption of O-GlcNAc cycling by deletion of O-GlcNAcase (Oga/Mgea5) changed gene expression pattern in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells. Genom Data. 2015;5:30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leney AC, Rafie K, van Aalten DMF, Heck AJR. Direct Monitoring of Protein O-GlcNAcylation by High-Resolution Native Mass Spectrometry. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:2078–2084. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishikawa I, Nakajima Y, Ito M, Fukuchi S, Homma K, Nishikawa K. Computational prediction of O-linked glycosylation sites that preferentially map on intrinsically disordered regions of extracellular proteins. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:4991–5008. doi: 10.3390/ijms11124991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazarus MB, Nam Y, Jiang J, Sliz P, Walker S. Structure of human O-GlcNAc transferase and its complex with a peptide substrate. Nature. 2011;469:564–567. doi: 10.1038/nature09638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kreppel LK, Hart GW. Regulation of a cytosolic and nuclear O-GlcNAc transferase. Role of the tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32015–32022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lazarus BD, Love DC, Hanover JA. Recombinant O-GlcNAc transferase isoforms: identification of O-GlcNAcase, yes tyrosine kinase, and tau as isoform-specific substrates. Glycobiology. 2006;16:415–421. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jinek M, Rehwinkel J, Lazarus BD, Izaurralde E, Hanover JA, Conti E. The superhelical TPR-repeat domain of O-linked GlcNAc transferase exhibits structural similarities to importin alpha. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1001–1007. doi: 10.1038/nsmb833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez-Fleites C, Macauley MS, He Y, Shen DL, Vocadlo DJ, Davies GJ. Structure of an O-GlcNAc transferase homolog provides insight into intracellular glycosylation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:764–765. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine ZG, Fan C, Melicher MS, Orman M, Benjamin T, Walker S. O-GlcNAc Transferase Recognizes Protein Substrates Using an Asparagine Ladder in the Tetratricopeptide Repeat (TPR) Superhelix. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:3510–3513. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b13546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Y, Wells L, Comer FI, Parker GJ, Hart GW. Dynamic O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: cloning and characterization of a neutral, cytosolic beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase from human brain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9838–9845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010420200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wells L, Gao Y, Mahoney JA, Vosseller K, Chen C, Rosen A, Hart GW. Dynamic O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: further characterization of the nucleocytoplasmic beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase, O-GlcNAcase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1755–1761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m109656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Comtesse N, Maldener E, Meese E. Identification of a nuclear variant of MGEA5, a cytoplasmic hyaluronidase and a beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;283:634–640. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen DL, Gloster TM, Yuzwa SA, Vocadlo DJ. Insights into O-linked N-acetylglucosamine ([0–9]O-GlcNAc) processing and dynamics through kinetic analysis of O-GlcNAc transferase and O-GlcNAcase activity on protein substrates. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:15395–15408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.310664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toleman C, Paterson AJ, Whisenhunt TR, Kudlow JE. Characterization of the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domain of a bifunctional protein with activable O-GlcNAcase and HAT activities. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53665–53673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toleman CA, Paterson AJ, Kudlow JE. The histone acetyltransferase NCOAT contains a zinc finger-like motif involved in substrate recognition. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3918–3925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Butkinaree C, Cheung WD, Park S, Park K, Barber M, Hart GW. Characterization of beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase cleavage by caspase-3 during apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23557–23566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804116200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rani L, Mallajosyula SS. Phosphorylation versus O-GlcNAcylation: Computational Insights into the Differential Influences of the Two Competitive Post-Translational Modifications. J Phys Chem B. 2017 doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b08790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hart GW, Slawson C, Ramirez-Correa G, Lagerlof O. Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:825–858. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060608-102511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaasik K, Kivimae S, Allen JJ, Chalkley RJ, Huang Y, Baer K, Kissel H, Burlingame AL, Shokat KM, Ptacek LJ, Fu YH. Glucose sensor O-GlcNAcylation coordinates with phosphorylation to regulate circadian clock. Cell Metab. 2013;17:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z, Udeshi ND, O'Malley M, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Hart GW. Enrichment and site mapping of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine by a combination of chemical/enzymatic tagging, photochemical cleavage, and electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:153–160. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900268-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li X, Lu F, Wang JZ, Gong CX. Concurrent alterations of O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation of tau in mouse brains during fasting. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2078–2086. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tian J, Geng Q, Ding Y, Liao J, Dong MQ, Xu X, Li J. O-GlcNAcylation Antagonizes Phosphorylation of CDH1 (CDC20 Homologue 1) J Biol Chem. 2016;291:12136–12144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.717850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu P, Shimoji S, Hart GW. Site-specific interplay between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation in cellular regulation. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2526–2538. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zeidan Q, Hart GW. The intersections between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: implications for multiple signaling pathways. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:13–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zachara NE, Hart GW. Cell signaling, the essential role of O-GlcNAc! Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:599–617. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bond MR, Ghosh SK, Wang P, Hanover JA. Conserved nutrient sensor O-GlcNAc transferase is integral to C. elegans pathogen-specific immunity. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O'Sullivan TE, Sun JC, Lanier LL. Natural Killer Cell Memory. Immunity. 2015;43:634–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steinman RM. Linking innate to adaptive immunity through dendritic cells. Novartis Foundation symposium. 2006;279:101–109. discussion 109–113, 216-109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ginhoux F, Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen Q, Chen Y, Bian C, Fujiki R, Yu X. TET2 promotes histone O-GlcNAcylation during gene transcription. Nature. 2013;493:561–564. doi: 10.1038/nature11742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bauer C, Gobel K, Nagaraj N, Colantuoni C, Wang M, Muller U, Kremmer E, Rottach A, Leonhardt H. Phosphorylation of TET proteins is regulated via O-GlcNAcylation by the O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT) J Biol Chem. 2015;290:4801–4812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.605881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang X, Zhang F, Kudlow JE. Recruitment of O-GlcNAc transferase to promoters by corepressor mSin3A: coupling protein O-GlcNAcylation to transcriptional repression. Cell. 2002;110:69–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00810-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hwang SY, Hwang JS, Kim SY, Han IO. O-GlcNAc transferase inhibits LPS-mediated expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase through an increased interaction with mSin3A in RAW264.7 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C601–608. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00042.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hwang SY, Hwang JS, Kim SY, Han IO. O-GlcNAcylation and p50/p105 binding of c-Rel are dynamically regulated by LPS and glucosamine in BV2 microglia cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:1551–1560. doi: 10.1111/bph.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.He Y, Ma X, Li D, Hao J. Thiamet G mediates neuroprotection in experimental stroke by modulating microglia/macrophage polarization and inhibiting NF-kappaB p65 signaling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:2938–2951. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16679671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ryu IH, Do SI. Denitrosylation of S-nitrosylated OGT is triggered in LPS-stimulated innate immune response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;408:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hwang JS, Kwon MY, Kim KH, Lee Y, Lyoo IK, Kim JE, Oh ES, Han IO. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated iNOS Induction Is Increased by Glucosamine under Normal Glucose Conditions but Is Inhibited by Glucosamine under High Glucose Conditions in Macrophage Cells. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:1724–1736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.737940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li X, Zhang Z, Li L, Gong W, Lazenby AJ, Swanson BJ, Herring LE, Asara JM, Singer JD, Wen H. Myeloid-derived cullin 3 promotes STAT3 phosphorylation by inhibiting OGT expression and protects against intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2017;214:1093–1109. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kneass ZT, Marchase RB. Neutrophils exhibit rapid agonist-induced increases in protein-associated O-GlcNAc. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45759–45765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kneass ZT, Marchase RB. Protein O-GlcNAc modulates motility-associated signaling intermediates in neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14579–14585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Madsen-Bouterse SA, Xu Y, Petty HR, Romero R. Quantification of O-GlcNAc protein modification in neutrophils by flow cytometry. Cytometry A. 2008;73:667–672. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Not LG, Brocks CA, Vamhidy L, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. Increased O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine levels on proteins improves survival, reduces inflammation and organ damage 24 hours after trauma-hemorrhage in rats. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:562–571. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb10b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Macian F. NFAT proteins: key regulators of T-cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:472–484. doi: 10.1038/nri1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oh H, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB: roles and regulation in different CD4(+) T-cell subsets. Immunol Rev. 2013;252:41–51. doi: 10.1111/imr.12033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ramakrishnan P, Clark PM, Mason DE, Peters EC, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Baltimore D. Activation of the transcriptional function of the NF-kappaB protein c-Rel by O-GlcNAc glycosylation. Sci Signal. 2013;6:ra75. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ramakrishnan P, Kahn DA, Baltimore D. Anti-apoptotic effect of hyperglycemia can allow survival of potentially autoreactive T cells. Cell death and differentiation. 2011;18:690–699. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang WH, Park SY, Nam HW, Kim DH, Kang JG, Kang ES, Kim YS, Lee HC, Kim KS, Cho JW. NFkappaB activation is associated with its O-GlcNAcylation state under hyperglycemic conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17345–17350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806198105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ma Z, Chalkley RJ, Vosseller K. Hyper-O-GlcNAcylation activates nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kappaB) signaling through interplay with phosphorylation and acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:9150–9163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.766568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Johnson B, Opimba M, Bernier J. Implications of the O-GlcNAc modification in the regulation of nuclear apoptosis in T cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Swamy M, Pathak S, Grzes KM, Damerow S, Sinclair LV, van Aalten DM, Cantrell DA. Glucose and glutamine fuel protein O-GlcNAcylation to control T cell self-renewal and malignancy. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:712–720. doi: 10.1038/ni.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu R, Ma X, Chen L, Yang Y, Zeng Y, Gao J, Jiang W, Zhang F, Li D, Han B, Han R, Qiu R, Huang W, Wang Y, Hao J. MicroRNA-15b Suppresses Th17 Differentiation and Is Associated with Pathogenesis of Multiple Sclerosis by Targeting O-GlcNAc Transferase. J Immunol. 2017;198:2626–2639. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Antony P, Petro JB, Carlesso G, Shinners NP, Lowe J, Khan WN. B cell receptor directs the activation of NFAT and NF-kappaB via distinct molecular mechanisms. Exp Cell Res. 2003;291:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pham LV, Tamayo AT, Yoshimura LC, Lin-Lee YC, Ford RJ. Constitutive NF-kappaB and NFAT activation in aggressive B-cell lymphomas synergistically activates the CD154 gene and maintains lymphoma cell survival. Blood. 2005;106:3940–3947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yao AY, Tang HY, Wang Y, Feng MF, Zhou RL. Inhibition of the activating signals in NK92 cells by recombinant GST-sHLA-G1a chain. Cell Res. 2004;14:155–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yin J, Leavenworth JW, Li Y, Luo Q, Xie H, Liu X, Huang S, Yan H, Fu Z, Zhang LY, Zhang L, Hao J, Wu X, Deng X, Roberts CW, Orkin SH, Cantor H, Wang X. Ezh2 regulates differentiation and function of natural killer cells through histone methyltransferase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:15988–15993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521740112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chu CS, Lo PW, Yeh YH, Hsu PH, Peng SH, Teng YC, Kang ML, Wong CH, Juan LJ. O-GlcNAcylation regulates EZH2 protein stability and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1355–1360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323226111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. The Metabolism of Tumors in the Body. The Journal of general physiology. 1927;8:519–530. doi: 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ma Z, Vosseller K. Cancer metabolism and elevated O-GlcNAc in oncogenic signaling. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:34457–34465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.577718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Slawson C, Hart GW. O-GlcNAc signalling: implications for cancer cell biology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:678–684. doi: 10.1038/nrc3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.de Queiroz RM, Carvalho E, Dias WB. O-GlcNAcylation: The Sweet Side of the Cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:132. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chaiyawat P, Netsirisawan P, Svasti J, Champattanachai V. Aberrant O-GlcNAcylated Proteins: New Perspectives in Breast and Colorectal Cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:193. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yang YR, Kim DH, Seo YK, Park D, Jang HJ, Choi SY, Lee YH, Lee GH, Nakajima K, Taniguchi N, Kim JM, Choi EJ, Moon HY, Kim IS, Choi JH, Lee H, Ryu SH, Cocco L, Suh PG. Elevated O-GlcNAcylation promotes colonic inflammation and tumorigenesis by modulating NF-kappaB signaling. Oncotarget. 2015;6:12529–12542. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang WH, Kim JE, Nam HW, Ju JW, Kim HS, Kim YS, Cho JW. Modification of p53 with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine regulates p53 activity and stability. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1074–1083. doi: 10.1038/ncb1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ferrer CM, Lynch TP, Sodi VL, Falcone JN, Schwab LP, Peacock DL, Vocadlo DJ, Seagroves TN, Reginato MJ. O-GlcNAcylation regulates cancer metabolism and survival stress signaling via regulation of the HIF-1 pathway. Mol Cell. 2014;54:820–831. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shi Y, Tomic J, Wen F, Shaha S, Bahlo A, Harrison R, Dennis JW, Williams R, Gross BJ, Walker S, Zuccolo J, Deans JP, Hart GW, Spaner DE. Aberrant O-GlcNAcylation characterizes chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:1588–1598. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang B, Zhou P, Li X, Shi Q, Li D, Ju X. Bitterness in sugar: O-GlcNAcylation aggravates pre-B acute lymphocytic leukemia through glycolysis via the PI3K/Akt/c-Myc pathway. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7:1337–1349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Freund P, Kerenyi MA, Hager M, Wagner T, Wingelhofer B, Pham HTT, Elabd M, Han X, Valent P, Gouilleux F, Sexl V, Kramer OH, Groner B, Moriggl R. O-GlcNAcylation of STAT5 controls tyrosine phosphorylation and oncogenic transcription in STAT5-dependent malignancies. Leukemia. 2017;31:2132–2142. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ding N, Ping L, Shi Y, Feng L, Zheng X, Song Y, Zhu J. Thiamet-G-mediated inhibition of O-GlcNAcase sensitizes human leukemia cells to microtubule-stabilizing agent paclitaxel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;453:392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.09.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pham LV, Bryant JL, Mendez R, Chen J, Tamayo AT, Xu-Monette ZY, Young KH, Manyam GC, Yang D, Medeiros LJ, Ford RJ. Targeting the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway and O-linked N-acetylglucosamine cycling for therapeutic and imaging capabilities in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:80599–80611. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tang CY, Mauro C. Similarities in the Metabolic Reprogramming of Immune System and Endothelium. Front Immunol. 2017;8:837. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xing D, Gong K, Feng W, Nozell SE, Chen YF, Chatham JC, Oparil S. O-GlcNAc modification of NFkappaB p65 inhibits TNF-alpha-induced inflammatory mediator expression in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shi J, Wu S, Dai CL, Li Y, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX. Diverse regulation of AKT and GSK-3beta by O-GlcNAcylation in various types of cells. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2443–2450. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gurcel C, Vercoutter-Edouart AS, Fonbonne C, Mortuaire M, Salvador A, Michalski JC, Lemoine J. Identification of new O-GlcNAc modified proteins using a click-chemistry-based tagging. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry. 2008;390:2089–2097. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-1950-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rexach JE, Rogers CJ, Yu SH, Tao J, Sun YE, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Quantification of O-glycosylation stoichiometry and dynamics using resolvable mass tags. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:645–651. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ma J, Hart GW. Analysis of Protein O-GlcNAcylation by Mass Spectrometry. Current protocols in protein science. 2017;87:24 10 21–24 10 16. doi: 10.1002/cpps.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hou CW, Mohanan V, Zachara NE, Grimes CL. Identification and biological consequences of the O-GlcNAc modification of the human innate immune receptor, Nod2. Glycobiology. 2016;26:13–18. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwv076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]