Significance

Cellulosomes are large, multienzyme complexes that efficiently degrade plant cell walls. Their central building blocks are cohesin modules that serve as attachment sites for enzymes. We study the dynamic structural organization by investigating a dyad of cohesin modules connected by a flexible linker using a combination of single-molecule FRET experiments and molecular dynamics simulations. We show that cohesin modules engage in intermodular interactions on the submillisecond timescale, which persist in the presence of the catalytic modules of the cellulosome. We propose that cohesin–cohesin interactions are important for the fine-tuning of the structure of cellulosomes for precise positioning of the catalytic enzymes, while their structural flexibility is facilitated by the flexible linkers.

Keywords: single molecule, fluorescence, FRET, molecular dynamics, conformational dynamics

Abstract

Efficient degradation of plant cell walls by selected anaerobic bacteria is performed by large extracellular multienzyme complexes termed cellulosomes. The spatial arrangement within the cellulosome is organized by a protein called scaffoldin, which recruits the cellulolytic subunits through interactions between cohesin modules on the scaffoldin and dockerin modules on the enzymes. Although many structural studies of the individual components of cellulosomal scaffoldins have been performed, the role of interactions between individual cohesin modules and the flexible linker regions between them are still not entirely understood. Here, we report single-molecule measurements using FRET to study the conformational dynamics of a bimodular cohesin segment of the scaffoldin protein CipA of Clostridium thermocellum. We observe compacted structures in solution that persist on the timescale of milliseconds. The compacted conformation is found to be in dynamic equilibrium with an extended state that shows distance fluctuations on the microsecond timescale. Shortening of the intercohesin linker does not destabilize the interactions but reduces the rate of contact formation. Upon addition of dockerin-containing enzymes, an extension of the flexible state is observed, but the cohesin–cohesin interactions persist. Using all-atom molecular-dynamics simulations of the system, we further identify possible intercohesin binding modes. Beyond the view of scaffoldin as “beads on a string,” we propose that cohesin–cohesin interactions are an important factor for the precise spatial arrangement of the enzymatic subunits in the cellulosome that leads to the high catalytic synergy in these assemblies and should be considered when designing cellulosomes for industrial applications.

Cellulose from plant cell walls is the most abundant source of renewable carbon (1). As the world reserve of fossil fuels is being depleted, the conversion of plant biomass into bioethanol is a promising approach to solve the global energy problem. The efficient degradation of plant cell wall material, however, remains a challenge due to the hydrolytic stability of cellulosic polysaccharides (2–4). In nature, aerobic bacteria and fungi secrete specialized enzymes to break down cellulose into oligosaccharides. In contrast, anaerobic bacteria utilize a cell-attached extracellular megadalton multienzyme complex, called the cellulosome, to efficiently degrade plant cell walls (5–7). The spatial proximity of cellulases and hydrolases within the cellulosome results in its highly synergetic catalytic activity (8).

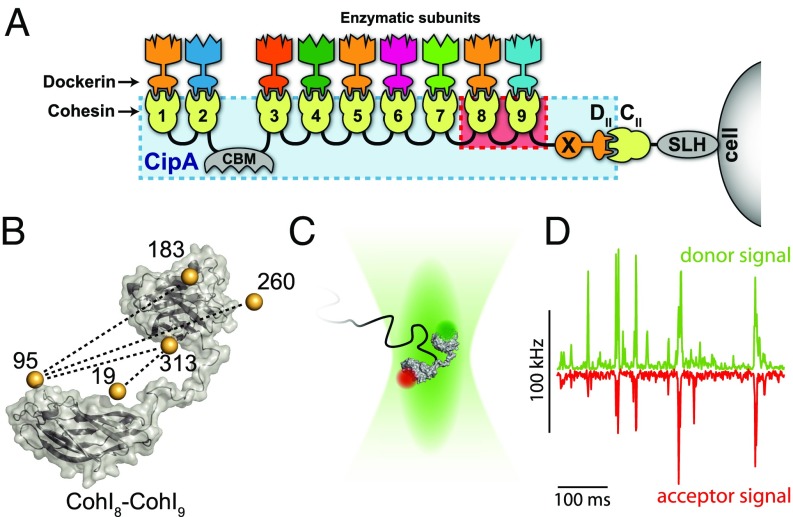

The cellulosome of the thermophilic anaerobe Clostridium thermocellum contains the extracellular scaffoldin protein CipA that mediates the cell–substrate interactions via the cellulose-binding module (CBM) (Fig. 1A) (9–12). Cell wall attachment is achieved through the binding of a type II dockerin (DocII) module in CipA to a type II cohesin (CohII) module in a cell surface-associated protein linked to the cell through a surface layer homology domain (SLH). An X module adjacent to the DocII module has been shown to have an important function for the binding interaction (13). CipA contains a linear array of nine type I cohesin (CohI) modules with the CBM located between CohI 2 and 3. Each CohI module acts as an attachment site for various cellulose-processing enzymes, which bind with high affinity through their type I dockerin (DocI) modules (14–16). The interactions between the CipA CohI and the enzyme-borne DocI modules of different enzymes are nonspecific and thus allow for variability in the composition of the catalytic subunits (17, 18).

Fig. 1.

Structure of the cellulosome of C. thermocellum. (A) The cellulosome complex is composed of the scaffoldin protein (CipA, blue box) that is anchored to the cell surface and the cellulose, offering binding sites for cellulose-processing enzymes. Surface attachment occurs through a surface layer homology domain (SLH) linked to a type II cohesin module (CII), that interacts with a type II dockerin module (DII) connected to an X module (X) at the C terminus of CipA. Binding to cellulose occurs via the cellulose-binding module (CBM). CipA contains nine type I cohesin modules (1–9) that can each bind to a type I dockerin module on different cellulose-processing enzymes. In this work, the CohI8–CohI9 fragment of CipA is studied (highlighted in red). (B) Atomistic model of the CohI8–CohI9 fragment defined from a homology model. Bronze spheres indicate the average fluorophore positions determined from geometrical calculations of the accessible volume (36). Dashed lines show the labeling combinations investigated by smFRET. (C) In the experiment, fluorescently labeled molecules are measured as they freely diffuse through the confocal volume. (D) Single-molecule events result in coinciding bursts of fluorescence in the donor and acceptor detection channels.

Previous X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy studies revealed the structure of many individual components of the cellulosome (19, 20). However, due to the inherently dynamic quaternary structure of the cellulosome (21, 22), the precise arrangement of the components linked by the scaffoldin protein remains poorly understood. Low-resolution structural methods such as small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) have revealed a dynamic picture of different artificial (23) and natural scaffoldin (24–26) fragments. Additional structural insights were obtained by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) on a fragment of CipA consisting of three consecutive CohI modules, which in contrast showed a compacted structure with outward-pointing catalytic domains (27). The C. thermocellum scaffoldin segments are connected by flexible linkers that are 20–40 residues long and rich in proline and threonine residues. These intercohesin linkers were found to be predominantly disordered by molecular-dynamics (MD) (28) and SAXS (24–26) studies, but were proposed to adopt a predominantly extended structure based on recent NMR data (29). The structural flexibility may be essential for the efficient access to the crystalline cellulose substrate within the heterogeneous environment of the plant cell wall containing hemicellulose, lignin, and pectin components. The connection of cohesins by linkers has been reported to enhance the catalytic activity in minicellulosome model systems by a factor of ∼2; however, contradictory results have been obtained regarding the effect of linker length and composition (23, 30).

To directly measure the dynamics of scaffoldin and thereby investigate the role dynamics play for the cellulosome, we investigated the conformational dynamics of a tandem fragment of CipA consisting of the cohesin I modules 8 and 9 connected by the 23-residue-long WT linker (Fig. 1A, red square, and Fig. 1B) using single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET). The CohI8–CohI9 fragment underwent transitions between compacted and extended structures on the millisecond timescale. Quantitative information about the interconversion rates was obtained from dynamic photon distribution analysis (dynamic PDA) (31, 32) and filtered fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (fFCS) (33). The effect of the linker on the structural dynamics was probed by shortening of the linker peptide, and the influence of the CohI–DocI interactions was investigated using the enzymes Cel8A and Cel48S. We also complemented the experimental data with all-atom MD simulations to gain further insights into possible intercohesin binding modes on the atomic level.

Results and Discussions

smFRET Identifies Interactions in the CohI8–CohI9 Fragment.

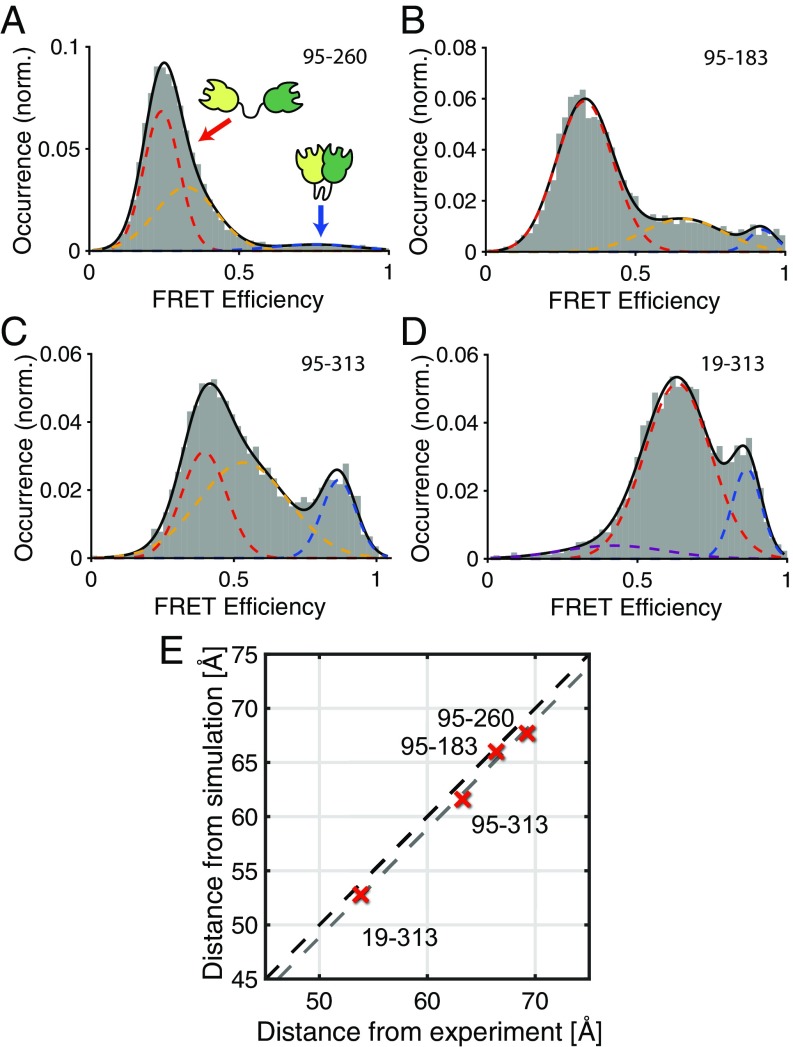

We investigated the intermodular distance fluctuations of the CohI8–CohI9 fragment from CipA using a smFRET analysis (34). In this method, fluorescently labeled single molecules are measured at picomolar concentrations in solution as they diffuse through the observation volume of a confocal fluorescence microscope on the timescale of ∼1 ms (Fig. 1 C and D). For every single-molecule event, the efficiency of energy transfer from a donor fluorophore to an acceptor fluorophore reports on the interdye distance and thus the conformation of the molecule. In contrast to ensemble methods, which report an average value, smFRET is particularly suited to study the conformational heterogeneity of biomolecules by measuring intramolecular distances one molecule at a time. smFRET experiments were performed for different constructs probing a total of four distances between the CohI modules. For fluorescent labeling, we introduced cysteines at positions 19, 95, 183, 260, and 313 in the CohI8–CohI9 fragment to obtain the four combinations of labeling positions 19–313, 95–313, 95–183, and 95–260 (Fig. 1B). The attachment sites of the fluorophores were chosen outside of the dockerin-binding interface (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) (35). For each CohI8–CohI9 mutant, these positions were stochastically labeled with the dyes Atto532 and Atto647N. No local influence of the labeling position on the photophysical properties of either fluorophore was observed, allowing quantitative analyses without the necessity for site-specific labeling. The results of the smFRET experiments are shown in Fig. 2 A–D. The molecule-wise FRET efficiency histograms are shown together with the fit to three-component Gaussian distributions. All constructs showed a major FRET population with low-to-intermediate FRET efficiency (red dashed lines) and a high FRET efficiency population (E > 0.8, blue dashed lines). An intermediate FRET efficiency population (yellow dashed lines) connects the two populations. In construct 19–313, no intermediate population was detected by the analysis, but rather a small low FRET efficiency population was observed (purple dashed line).

Fig. 2.

Conformations of the investigated CohI8–CohI9 fragment. (A–D) SmFRET efficiency histograms for different combinations of labeling positions as indicated in Fig. 1B. Respective residues were mutated to cysteines, and labeling was performed stochastically with the dyes Atto532 and Atto647N. Histograms were fit using three Gaussian distributions, revealing low (red), medium (yellow), and high (blue) FRET efficiency populations. In the 19–313 construct (D), no medium-FRET efficiency population is observed, but an additional low-FRET efficiency population is detected (purple). (E) A comparison of the measured and simulated distances for the different constructs. A linear correlation is observed between the distances determined from the main population (dashed red lines in A–D) of the smFRET experiments and from rigid-body torsion-angle MD simulations. The experimental FRET efficiencies were converted into distances using a Förster radius of 59 Å. The black dashed line indicates a linear correlation, while the gray dashed line indicates linear correlation with an offset of 1.1 Å, as determined from the average deviation between experimental and theoretical distances.

To estimate expected FRET efficiencies of the dynamic, noninteracting CohI8–CohI9 fragment for all tested mutants, we performed simplified MD simulations in the absence of solvent, treating the CohI modules as rigid bodies. Under the conditions of the simulation, indeed no stable interactions occurred between the CohI modules, as is evident from the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the MD trajectory, which shows vanishing correlation after ∼100 ps (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). From the simulation, average FRET efficiency values are extracted using accessible volume calculations to determine sterically accessible positions for the dyes at every time step (36). We obtained good agreement between smFRET results for the low-FRET conformation and the simulated MD data (R2 > 0.98; Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Table S1) with an average deviation of 1.1 Å. The discrepancy is within the absolute experimental error one would expected for smFRET measurements (37). The good agreement between smFRET results and the MD data suggests that the “open” conformation, characterized by the absence of long-lived interactions between the CohI modules, corresponds to the dominant CohI8–CohI9 conformation.

Since previous studies revealed a highly dynamic structure for the related CohI1–CohI2 fragment (26), we expected all CohI8–CohI9 mutants to show a FRET efficiency distribution with a single peak for all constructs, as would be expected from fast dynamic averaging over many conformations on the timescale of diffusion through the confocal volume of ∼1 ms. The existence of a high FRET efficiency population in all four constructs suggests specific interactions between the two CohI modules that persist on the millisecond timescale. The observation of a characteristic bridge between the high FRET efficiency (“closed”) population and the low-to-intermediate FRET efficiency (“open”) conformation is additionally indicative of dynamic interconversion between the states. For the 19–313 construct, no intermediate FRET efficiency population is detected, likely because the difference between the FRET efficiencies of the open (E ∼ 0.6) and closed (E ∼ 0.9) is not large enough to resolve the conformational dynamics. The rigid-body MD simulations showed no stable interactions between the CohI modules and thus sampled the dynamic state of CohI8–CohI9, agreeing well with the experimentally determined distances of the main population.

The CohI8–CohI9 Fragment Shows Conformational Dynamics on the Millisecond Timescale.

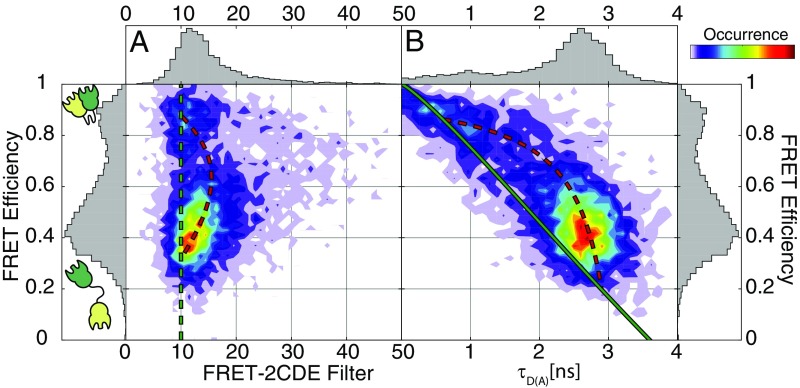

To further investigate the conformational dynamics of CohI8–CohI9, we employed the FRET-2CDE filter that identifies FRET fluctuations based on anticorrelated changes of the donor and FRET-sensitized acceptor signals (Fig. 3A) (38). The FRET-2CDE filter is defined such that a value of 10 signifies no dynamics, while any larger values indicate the presence of conformational transitions on the timescale between 0.1 and 10 ms. The 2D plot of FRET efficiency against FRET-2CDE filter (Fig. 3A) revealed a systematic deviation from the static line at a value of 10 for the FRET-2CDE filter for single-molecule events with intermediate FRET efficiency. We also examined the fluorescence lifetime of the donor fluorophore to further investigate the dynamics of the CohI8–CohI9 construct (Fig. 3B) (32). The lifetime of the donor fluorophore offers an independent readout of the FRET efficiency. In a plot of the FRET efficiency against the donor fluorescence lifetime, one can define a static FRET line (green line in Fig. 3B) that single-molecule events showing no conformational dynamics will lie on. A systematic shift toward longer fluorescence lifetimes results when conformational transitions occur during a single-molecule event. In the case of a two-state dynamic system, the dynamic FRET line can be calculated by considering all mixtures of the two states (dashed red line in Fig. 3B). The data clearly showed a systematic deviation from the static FRET line that could be explained by two-state conformational dynamics with lifetime values for the donor fluorophore of 0.6 and 2.9 ns for the two conformations. The same qualitative result was obtained for all four constructs (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 and Table S2). Interestingly, the low-FRET state was also shifted from the dynamic FRET line, although it showed a value around 10 for the FRET-2CDE filter. Since the FRET-2CDE filter relies on a kernel density estimator, effectively smoothing over a finite time window (here 100 µs), it is not sensitive to faster fluctuations. The lifetime-based readout, however, is independent of the timescale of the dynamics, since it only relies on the mixing of different conformations during a single-molecule event. This suggests that the extended state is highly dynamic on the microsecond timescale, faster than the averaging window of 100 µs chosen for the calculation of the FRET-2CDE filter. As a control, we measured a construct where both the donor and acceptor dyes were placed on the CohI9 module (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). As expected, the control construct showed a single population and exhibits no deviation from the static FRET line.

Fig. 3.

Identification of conformational dynamics in the CohI8–CohI9 construct 95–313. (A) Two-dimensional histogram of the FRET-2CDE filter versus FRET efficiency. Values larger than 10, visible for events with intermediate-to-high FRET efficiency, indicate dynamics within the burst. (B) Two-dimensional histogram of the donor lifetime versus FRET efficiency. A systematic shift from the static FRET line (green) is observed, consistent with the presence of conformational dynamics. Additionally, the low-to-intermediate FRET efficiency species at ∼40% also deviates from the static FRET line, indicating fast dynamics on the microsecond timescale. The dynamic behavior can be described theoretically using the dynamic FRET line (dashed red line). The start and end points were extracted from fluorescence decay analysis of all molecules using a biexponential model function (SI Appendix, Table S2).

The qualitative assessment of the conformational dynamics in CohI8–CohI9 confirms the hypothesis of a compacted state, which is in dynamic equilibrium with an open, flexible state or family of states. Additional information is obtained about the timescales of the dynamic processes. Transition to and from the compacted state occur on the millisecond timescale, while the open state exhibits fast fluctuations on the microsecond timescale. In the following sections, we focus on the characterization and quantification of the dynamics.

PDA Quantifies the Dynamics Between Open and Closed States.

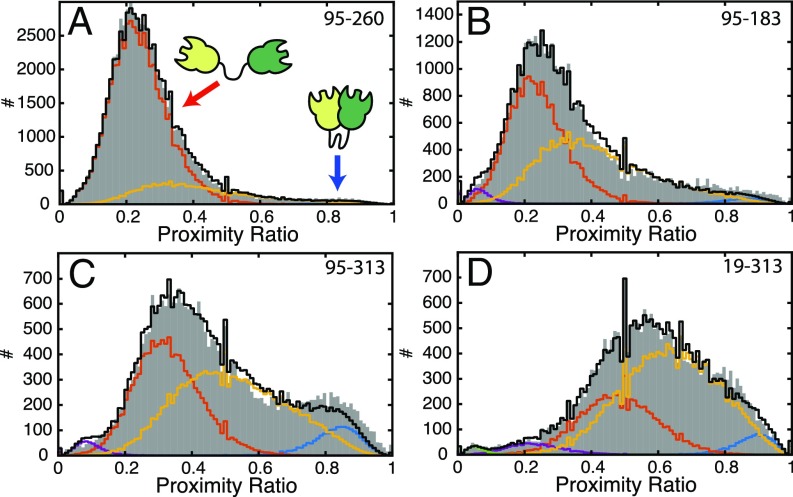

To quantify the timescale of the dynamics, we utilized additional analysis methods. First, we focus on the millisecond dynamics between the open and closed states. PDA is a powerful tool to disentangle the contributions of photon shot noise to the width of the observed FRET efficiency distribution, from physically relevant factors such as static conformational heterogeneity (31). In its simplest form, PDA assumes a Gaussian distribution of distances that is transformed using the known photon statistics of the measurement and the experimental correction factors to obtain the corresponding shot-noise limited proximity ratio (PR) histogram. PDA can also be used to describe the effect of conformational dynamics on the observed PR histogram (32). By sectioning the photon counts into equal time intervals, the resulting PR histogram can be described analytically using a two-state kinetic model, whereby each individual state’s heterogeneity is described by a distribution of distances. To increase the robustness of the analysis, each dataset was processed using different time window sizes (0.25, 0.5, and 1 ms) and globally fit with respect to the interdye distances and kinetic rates.

We performed dynamic PDA of all different constructs (Fig. 4 and Table 1). In addition to the two interconverting species, a static low-FRET population was needed to account for the contributions of small amounts (1–5%) of low-FRET efficiency species likely caused by acceptor blinking. The kinetic model was successful in describing the observed distributions of FRET efficiencies in all cases (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). While for the 19–313 construct no intermediate-FRET population was detected from the analysis of the FRET efficiency distribution (Fig. 2D), the global dynamic PDA was successful in recovering kinetic information for this construct (Fig. 4D). In all constructs, the extended state was more populated than the closed state, suggesting a fast rate of opening and a slower rate of contact formation. This is confirmed by the extracted rates for closing of koc = 0.5 ± 0.3 ms−1 and opening of kco = 2.0 ± 0.4 ms−1, corresponding to dwell time of ∼2 ms in the open state and ∼0.5 ms in the closed state. The determined center distances from PDA are in good agreement with the previous analysis of the FRET efficiency histograms, deviating by less than 3 Å (Table 1 and SI Appendix, Table S1).

Fig. 4.

Dynamic photon distribution analysis (PDA) of the WT CohI8–CohI9 fragment. To investigate the timescale of the indicated dynamics, PR histograms for constructs 95–260 (A), 95–183 (B), 95–313 (C), and 19–313 (D) were fit using dynamic PDA. Shown are the data for a time window size of 1 ms. The PRs (uncorrected FRET efficiency) are shown as gray bars and the dynamic PDA fits are shown as black lines. In addition, the low (red)- and high (blue)-FRET efficiency populations and the population of molecules showing interconversion during the observation time (yellow) are indicated. Additional static low-FRET efficiency populations are shown in purple and green. See SI Appendix, Fig. S5, for the global fit of the data using time windows of = 0.25, 0.5, and 1 ms.

Table 1.

Dynamic PDA of the different CohI8–CohI9 constructs with WT linker, Δ17 linker, and Δ11 linker

| Construct | 95–260 | 95–183 | 95–313 | 19–313 |

| WT linker | ||||

| Rclosed, Å | 40.2 ± 0.6 | 40.7 ± 1.0 | 41.3 ± 0.8 | 39.7 ± 1.0 |

| Ropen, Å | 69.4 ± 0.1 | 68.6 ± 0.3 | 62.8 ± 0.3 | 55.6 ± 0.6 |

| kclosed → open, ms−1 | 2.09 ± 0.10 | 2.39 ± 0.13 | 1.41 ± 0.09 | 1.92 ± 0.17 |

| kopen → closed, ms−1 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 0.57 ± 0.05 | 0.87 ± 0.13 |

| Δ11 linker | ||||

| Rclosed, Å | — | 40.0 ± 0.6 | 39.1 ± 1.6 | 38.5 ± 0.7 |

| Ropen, Å | — | 66.0 ± 0.2 | 62.6 ± 0.3 | 54.7 ± 0.3 |

| kclosed → open, ms−1 | — | 1.94 ± 0.10 | 2.14 ± 0.14 | 1.79 ± 0.23 |

| kopen → closed, ms−1 | — | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.67 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.06 |

| Δ17 linker | ||||

| Rclosed, Å | — | 42.9 ± 0.5 | 41.4 ± 0.5 | — |

| Ropen, Å | — | 66.2 ± 0.3 | 66.1 ± 0.3 | — |

| kclosed → open, ms−1 | — | 1.39 ± 0.22 | 1.93 ± 0.23 | — |

| kopen → closed, ms−1 | — | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | — |

The average interdye distances in the closed and open states, Rclosed and Ropen, and the interconversion rates, kclosed → open and kopen → closed are given. Construct 95–260 with the Δ11 linker showed artifacts in the measurement and was thus excluded from the analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Errors are given as 95% confidence intervals as determined from the curvature of the -surface.

Correlation Analysis Identifies a Second Kinetic State on the Microsecond Timescale.

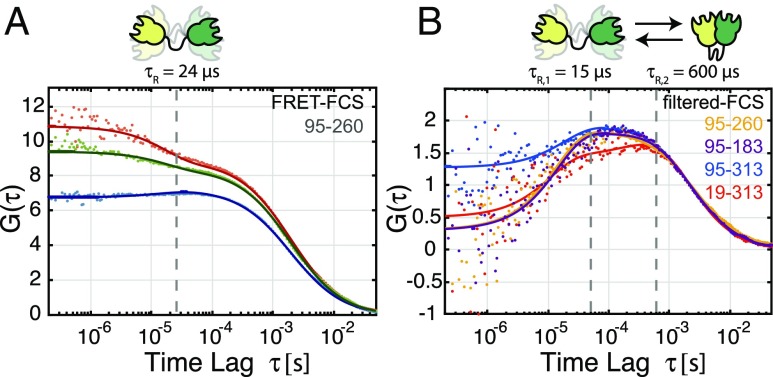

Second, we looked for conformational dynamics on the microsecond timescale. To this end, we applied FCS (39, 40). As a first step, we calculated the autocorrelation and cross-correlation functions of the donor fluorescence and the FRET-induced acceptor signal. In the presence of conformational dynamics, the FRET fluctuations cause an anticorrelation contribution to the cross-correlation function and matching positive contributions to the autocorrelation functions. Representative autocorrelation and cross-correlation functions for construct 95–260 are shown in Fig. 5A and for all constructs in SI Appendix, Fig. S6. From the FRET-FCS analysis, we obtained a kinetic relaxation time of 24 ± 7 µs across all four constructs (Table 2). To obtain a more detailed picture of these fast dynamics, we applied fFCS (33, 41). fFCS uses the lifetime, anisotropy, and color information available for each photon to assign statistical weights (or filters) with respect to two or more defined species (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). To define the open and closed conformation, the characteristic patterns were determined from the measurement directly by pooling data from the low- or high-FRET efficiency events (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B). The inclusion of additional dimensions and the application of statistical weighting in fFCS leads to increased contrast in comparison with the FRET-FCS analysis. The fFCS cross-correlation functions for the four constructs are shown in Fig. 5B. Fitting with a single kinetic term revealed systematic deviations in the residuals, prompting us to include a second kinetic term (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). The extracted timescales of the two terms are 15 ± 4 and 600 ± 200 µs for the fast and slow components, respectively (Table 2). The timescale of the slow component overlapped with the timescale of diffusion (∼1–2 ms), resulting in the relatively high uncertainty. The amplitude of the fast term was significantly higher, contributing to 72 ± 8% of the observed dynamics. Because the relaxation time of the slow component agrees well with that determined from the dynamic-PDA analysis (), we assign the slow component to the previously described slow transition between the open and closed state. The fast component identified by fFCS consequently corresponds to the dynamics of the freely fluctuating open state that occur on the timescale of ∼15 µs.

Fig. 5.

FCS analysis of conformational dynamics. (A) FRET-FCS reveals a bunching term in the donor fluorescence and FRET-induced acceptor fluorescence autocorrelation curves (green and red curves, respectively), as well as a corresponding anticorrelation term in the cross-correlation function (blue curve). A global analysis reveals dynamics with a timescale of 24 ± 7 µs. Data are shown for the 95–260 construct. (B) The fFCS cross-correlation functions are shown for the constructs 95–260 (yellow), 95–183 (purple), 95–313 (blue), and 19–313 (red). fFCS enhances the contrast of the kinetic contributions to the correlation function. The species cross-correlation curves for the four constructs show similar timescale of dynamics, revealing two terms, one at 15 ± 4 µs and a second at 600 ± 200 µs with contributions of 76 ± 4% and 24 ± 4%, respectively.

Table 2.

Species-selective FCS analysis of the different CohI8–CohI9 constructs with WT linker, Δ11 linker, and Δ17 linker

| FRET-FCS | fFCS | Dynamic PDA | ||||

| Construct | , µs | , µs | , % | , µs | , % | , µs |

| WT linker | 24 ± 7 | 15 ± 4 | 72 ± 8 | 600 ± 200 | 28 ± 8 | 410 ± 80 |

| Δ11 linker | 30 ± 14 | 10 ± 6 | 68 ± 4 | 350 ± 200 | 32 ± 4 | 420 ± 60 |

| Δ17 linker | 15 ± 2 | 11 ± 3 | 77 ± 15 | 440 ± 260 | 23 ± 15 | 550 ± 130 |

The average and SD of the relaxation times, , and relative amplitudes, , of independent analyses of the different labeling positions are listed here for the various linker constructs. All three correlation functions in FRET-FCS or four correlation functions in fFCS were globally fit as described in the main text. Relative amplitudes were determined based on amplitudes of the kinetic terms in the species cross-correlation functions. For comparison, the relaxation times from dynamic PDA, calculated by , are given. For the Δ11 linker, the construct 95–260 was excluded due to dye artifacts (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). For the Δ17 linker, constructs 95–313 and 95–163 were measured. For detailed results of the FCS analysis of the different constructs, see SI Appendix, Table S3.

Our observation of a highly dynamic structure in the open state is in agreement with previous studies on artificial chimeric minicellulosomes (23) or the CipA fragments CohI1–CohI2 and CohI2–CBM–CohI3 in complex with the enzyme Cel8A (26). On the other hand, a cryo-EM study on the fragment CohI3–CohI4–CohI5 in complex with Cel8A revealed predominantly compacted structures showing direct interactions between the cohesin modules with outward-pointing enzymes (27), similar to the compacted state observed here. The report of a small fraction of complexes in extended conformations in that study additionally supports our observation of a dynamic equilibrium between extended and compacted structures. Cohesin–cohesin interactions were also observed in the crystal structure of the C-terminal fragment of CipA, CohI9–X–DocII, in complex with a CohII module, showing homodimerization mediated by intermolecular contacts between the CohI9 modules (42), and in the crystal structure of a CohII dyad from Acetivibrio cellulolyticus (43).

Shortening of the Linker Has a Minor Effect on the Observed Dynamics.

After having characterized the structure and dynamics of the WT-linker CohI8–CohI9 fragment, we turned to investigate the role of the linker by designing constructs with shortened linkers. The WT linker is 23 residues long and is mainly composed of polar and aliphatic amino acids with a high content of threonine (39%) and proline (22%) residues (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). We deleted 11 residues from the center of the linker, shortening it to 12 residues without significantly altering the peptide properties (Δ11 linker; SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The dynamic behavior detected for the WT linker persists in the Δ11 linker constructs (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). However, construct 95–260 in combination with the Δ11 linker showed dye-related artifacts in the pulsed interleaved excitation (PIE)–multiparameter fluorescence detection (MFD) analysis and was thus excluded from the discussion (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). We again performed dynamic PDA to quantify the dynamics and interdye distance distributions (see Fig. 6A and Table 1 for construct 95–313, and SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S11, for all constructs). No significant distance change was detected for the closed conformation. Surprisingly, also no significant shift to shorter distances was evident for the open conformation, although construct 95–183 showed a minor contraction from 69 to 66 Å (Fig. 6B and Table 1). The dynamic interconversion rates of the Δ11 linker constructs exhibited no major change with respect to the WT linker with an opening rate of 2.0 ± 0.2 ms−1 and a closing rate of 0.5 ± 0.2 ms−1. As before, we performed a fFCS analysis (Table 2). In contrast to the dynamic PDA, the correlation analysis detects increased interconversion rates for the Δ11 linker constructs. The slow component showed a relaxation time of 350 ± 200 µs (averaged over all constructs), in good agreement with the dynamic timescale detected by dynamic PDA of 420 ± 60 µs for the Δ11 linker construct, but faster than what we obtained from the correlation analysis for the WT linker (600 ± 200 µs). For the Δ11 linker, the dynamics in the open conformation showed similar interconversion rates (relaxation time of 10 ± 6 µs) compared with the timescales in the WT-linker constructs (relaxation time of 15 ± 4 µs). To test whether further shortening of the linker peptide would disrupt the interactions, we measured the constructs 95–183 and 95–313 with a six-residue-long linker (Δ17 linker). Still, no large change was observed for the average distance of the open conformation with respect to the WT linker (Fig. 6B, Table 1, and SI Appendix, Fig. S11). CohI8–CohI9 remained dynamic with the Δ17 linker; however, a depopulation of the interacting state is apparent (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S11). The kinetic analysis revealed that, while the opening rate remains approximately constant, the closing rate is decreased by a factor of 2–3 (Table 1), indicating that the steric restriction caused by the shortened linker increases the barrier for the formation of intermodular contacts. The fluctuations in the open state remained on similar timescales as observed for the WT and Δ11 linker (relaxation time of 11 ± 3 µs; Table 2). Complete removal of the linker of construct 95–183 resulted in a single low-FRET state with no detectable dynamics, abolishing the interaction (SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S11).

Fig. 6.

The effect of linker shortening and enzyme binding on the dynamics of CohI8–CohI9. (A) Dynamic photon distribution analyses (PDAs) of the 95–313 construct with WT linker, Δ11 and Δ17 linkers, and WT linker with addition of the cellulosomal enzymes Cel8A and Cel48S. The smFRET histograms of the PRs (uncorrected FRET efficiencies) are plotted as gray bars, and the dynamic-PDA fits are shown as black lines. In addition, the low (red)- and high (blue)-FRET efficiency populations and the population of molecules showing interconversion during the observation time (yellow) are shown. Additional static low-FRET efficiency populations are shown in purple. (B) Comparison of the interdye distances of the open conformation (red in A) for the different constructs with WT linker, in the presence of the cellulosomal enzymes Cel8A and Cel48S and for the Δ11 and Δ17 linker constructs.

In summary, the effect of the Δ11 linker on the conformational states and dynamics of CohI8–CohI9 seems to be minor. As expected, the closed conformation was not affected by the linker length. However, shortening of the linker also had no significant effect on the average distance of the open conformation for both the Δ11 and Δ17 linkers, suggesting that the linker is not fully extended in the WT CohI8–CohI9, but assumes a more compacted structure due to the observed cohesin–cohesin interactions or via the formation of secondary structure. This is consistent with the results of a SAXS study where the linker length of a chimeric cohesin tandem construct (Scaf4) was systematically varied from 4 to 128 residues (23), revealing that the maximum extension of the construct plateaued already at a linker length of 39 residues. A recent NMR study of the isolated CohI5 module with its 24-residue-long linker of similar composition reported a rigid and extended structure of the linker (29). The absence of a second CohI module in that study further indicates that cohesin–cohesin or cohesin–linker interactions may be responsible for the observed compaction of the structure. Interestingly, the stability of the cohesin–cohesin interactions was not affected by the linker length, as the interconversion rates between compacted and extended structures showed no significant change. On the other hand, shortening of the linker overall resulted in reduced rates of contact formation.

Dockerin Binding Shifts the Conformational Space Toward the Extended State.

The primary in vivo function of the CohI modules is the binding of cellulose-processing enzymes. We investigated the influence of the cellulosomal enzymes Cel8A and Cel48S on the conformational dynamics of CohI8–CohI9. Both enzymes bind with high affinity to a CohI module through their respective DocI modules with KD values in the range of 10 nM (14). We first confirmed that Cel8A and Cel48S bind to CohI8–CohI9 under the experimental conditions using FCS (SI Appendix, Fig. S12A). We determined KD values of 4 nM for Cel8A and 14 nM for Cel48S (SI Appendix, Fig. S12B). In the presence of binding partners, the dynamic behavior of CohI8–CohI9 persisted (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). The dynamic PDAs of CohI8–CohI9 in the presence of Cel8A and Cel48S are shown in Fig. 6A for the 95–313 construct. The results for all four constructs are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S14 and Table S4, and summarized in Fig. 6B. For construct 95–313 (Fig. 6A), the average distance in the extended conformation increases from 63 Å in the absence of binding partners to 73 and 69 Å in the presence of Cel8A and Cel48S, respectively. This extension of the open state was consistently observed for all constructs (Fig. 6B). Averaged over all constructs, no significant shift of the dynamic equilibrium toward the extended state was observed, with average rates of opening and closing of 1.9 ± 1.5 and 0.5 ± 0.3 ms−1 for Cel8A and 1.7 ± 0.6 and 0.5 ± 0.1 ms−1 for Cel48S, similar to the rates observed in the absence of binding partners of 2.0 ± 0.4 and 0.5 ± 0.3 ms−1.

In summary, the interaction of CohI8–CohI9 with the cellulosomal enzymes Cel8A and Cel48S resulted in an extension of the open state, while leaving the conformational dynamics largely unaffected. The observed dynamic structure of the CohI8–CohI9 fragment in complex with Cel8A is supported by SAXS studies on CohI1–CohI2 with the same enzyme (26) and enzyme-bound hybrid minicellulosomes (23), which identified a dynamic and extended structure. Likewise, the fragment CohI3–CohI4–CohI5 in complex with Cel8A has been observed to adopt both extended and compacted structures mediated by cohesin–cohesin interactions (27). The persistence of the compacted conformation in the presence of cohesin–dockerin interactions implies that the dockerin-binding interfaces on the cohesins are not involved in cohesin–cohesin interactions.

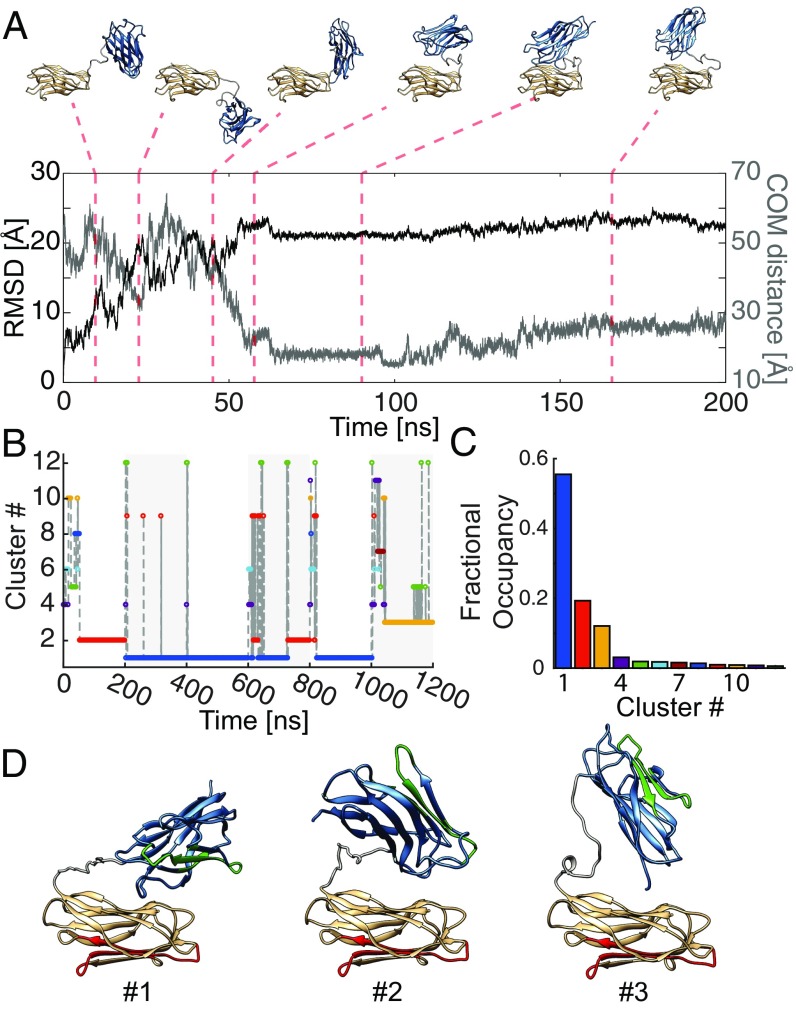

All-Atom MD Simulations Provide an Atomistic Picture of the Interactions.

From the smFRET experiments, we could identify a compacted state of the CohI8–CohI9 fragment. To complement the FRET information provided by the four distances, we performed all-atom MD simulations of CohI8–CohI9 in explicit solvent (Materials and Methods). In total, six trajectories of 200-ns length were simulated from the extended starting configuration, resulting in a different evolution of the system despite the use of identical starting coordinates as evidenced by the RMSD of the trajectories (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). A detailed display of one of the MD runs is given in Fig. 7A and in Movie S1. Snapshots of the trajectory are displayed at the indicated time points above the graph. For the first 50 ns of the simulation, the protein sampled many different open structures without forming intermodular contacts. The two modules then contacted each other and form a stable interaction after ∼60 ns, which persisted for the rest of the simulation, showing little additional change in the RMSD (black line in Fig. 7A). As a second parameter for investigating the cohesin–cohesin interactions, we computed the center-of-mass (COM) distance between the two modules (gray line). The COM distance contains more specific information about the interaction between the two modules, revealing a slow conformational readjustment from 100 ns until the end of the simulation. During this period, the modules stay in contact but perform a twisting motion with respect to each other, transitioning from a collinear to a perpendicular orientation. Similar behavior of intermodular docking during the first half of the simulation was observed for all repeats (SI Appendix, Fig. S16). In some cases, detachment of the modules was observed, persisting for only ∼10 ns. To obtain an overview of the sampled stable configurations of CohI8–CohI9, we performed a global cluster analysis over all six trajectories (Fig. 7 B and C). The conformational landscape is dominated by three main clusters, accounting for ∼85% of the trajectories (Fig. 7D). Clusters 1 and 2 were found in multiple trajectories, whereas cluster 3 is unique to trajectory 6. The first cluster adopted a structure showing a perpendicular orientation of the modules. The second and third largest clusters both showed structures where one module contacts the other in a “heads-down” orientation, however showing opposite orientation of the top module between cluster 2 and 3. We also performed individual cluster analyses for each trajectory (SI Appendix, Fig. S17). Each trajectory was dominated by one or two clusters that accounted for at least 50% of the trajectory. The structures for all major clusters are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S18, for a complete picture of all stable conformations adopted during the simulation. It should be noted that the identified binding modes here are different from the cohesin–cohesin interaction previously observed in crystals (42). To compare the MD simulations with our experimental results on the closed state of CohI8–CohI9, we determined FRET-average distances from the MD trajectories as described before for the open state (SI Appendix, Table S5). Given the high FRET efficiency of the closed state and thus increased uncertainty of the experimentally determined distances, we find reasonable agreement; however, the MD-derived distances are consistently larger than the experimental distances by ∼8 Å on average. A possible reason could be transient dye–dye interactions that might occur at the short interdye distances, resulting in deviations of the experimentally derived distances (44).

Fig. 7.

All-atom MD simulations of the CohI8–CohI9 fragment. (A) A representative trajectory of a 200-ns MD simulation. (Top) Snapshots at the indicated time points of the trajectory. Starting from an extended configuration, the two modules (bronze, CohI8; blue, CohI9) come into close contact after ∼60 ns. After the initial contact formation, only minor movements occur without dissociation. (Bottom) The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) with respect to the starting structure plateaus after ∼60 ns. Analogously, the center-of-mass (COM) distance between the two modules indicates a close contact. From 100 ns onward, slight structural rearrangements in the compacted form are evident. See Movie S1 for an animation of the trajectory. (B) A cluster analysis of all six MD simulations of 200 ns each was performed to obtain global structures of the compacted conformation (shading indicates the individual trajectories). Trajectories 2, 3, 4, and 5 are dominated by cluster 1. (C) Fractional occupancy of the individual clusters. The top three clusters constitute over 80% of the global trajectory. (D) The average structures of clusters 1–3. Regions colored in green and red indicate the binding interfaces for DocI modules as given in SI Appendix, Fig. S1 (35).

The Intermodular Interaction Is Characterized by a Variety of Different Binding Modes.

The experimental results of cohesin–cohesin interactions raised the questions whether specific interactions are present, and what role the cohesin–dockerin binding interfaces play. Overall, the simulations showed a variety of binding modes. While the global cluster analysis revealed three predominant structures, each of the individual clusters still exhibits some degree of internal variance, indicated by average pairwise RMSD distances within the clusters of 7–8 Å and SDs of the RMSD of 2.5–4 Å. This suggests that a multitude of different binding modes are present, and the interaction between the modules is not dominated by one specific conformation. To further investigate the cohesin–cohesin interactions, we quantified the number of intermodular contacts formed per residue. Intriguingly, arginine 6 in CohI8 is found to be involved in intermodular contacts in all three major clusters (SI Appendix, Fig. S19 A–C). Indeed, in the simulations, the observed conformational space changed significantly when R6 is replaced by a glycine, leading to less frequent formation of stable cohesin–cohesin interactions (SI Appendix, Figs. S19 D and E and S20). In construct 95–260, T260 was mutated to a cysteine, placing the fluorescent label in direct vicinity of Q195 and E261. In the experiments, this construct showed the lowest population of the closed state (Fig. 4) due to a reduced rate of closing of 0.14 ms−1 compared with 0.5–0.9 ms−1 for the other constructs (Table 1), indicating that cohesin–cohesin interactions are hindered in this construct. To further test our hypothesis, we performed experiments on R6G mutants of the constructs 95–183, 95–313, and 19–313 (SI Appendix, Fig. S19 F–K and Table S6). While a slight depopulation of the interacting state was observed for construct 19–313, no clear change is observed for the other two constructs. This indicates that the intermodular contacts are not dominated by a single specific interaction with the arginine at position 6. Rather, this suggests that many residues in the region are involved in stabilizing the interaction, as supported by the results from the simulation of the R6G mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S19E). Based on the high sequence conservation between the different type I cohesins (SI Appendix, Fig. S21), other cohesin pairs may exhibit similar intermodular interactions, which potentially serve as a mechanism to fine-tune the quaternary structure of the scaffoldin.

We further tested the stability of the intermodular contacts with respect to salt and denaturant. Even at high salt concentrations above 1 M NaCl, the interactions persisted (SI Appendix, Fig. S22A), indicating that the interaction is not governed by electrostatics. As cellulosomal subunits and their individual component parts (notably, cohesin and dockerin modules) are known to be remarkably stable to heat, mechanical forces, and denaturing agents, such as guanidine, urea, and SDS (45–49), we could use mild denaturing conditions to investigate the role of hydrogen bonding without denaturing the protein. In the presence of 500 mM GuHCl (SI Appendix, Fig. S22B), we indeed did observe a decrease in the strength of the interaction, suggesting that hydrogen bonding is important.

With respect to the enzymatic activity of the cellulosome, it is important to consider the formation of cohesin–cohesin interactions in the context of the accessibility of the dockerin-binding sites. To this end, we colored the residues that have previously been identified to be involved in contacts to DocI modules in Fig. 7D and in SI Appendix, Fig. S18, in red and green (see SI Appendix, Fig. S1, for the colored residues) (35). Interestingly, the DocI-binding surfaces on the CohI modules are mostly unobstructed by the cohesin–cohesin interaction in all stable structures. Hence, the binding of enzymes to the cohesins is not expected to be hindered by cohesin–cohesin interactions. Likewise, the dockerin–cohesin interaction should not interrupt the formation of compacted structures, as is confirmed by our experimental results. Regarding the intermodular linker, we observed no significant formation of stable secondary structure or long-lived interactions within the linker or between the linker and the cohesin domains. In agreement with the experimental data, the linker was rarely extended and often assumed compacted conformations.

In summary, the MD simulations reveal that CohI8–CohI9 consistently adopts compacted conformations that are stable on the timescale of the simulations (200 ns). A multitude of different binding modes were identified, indicating that the interaction between the modules is not dominated by one specific conformation. In these stable conformations, the dockerin-binding interfaces of the cohesins are exposed to the solvent and thus accessible for enzyme binding. This suggests that cohesin–cohesin interactions and dockerin binding are not mutually exclusive.

Conclusions

Herein, we characterized the conformational dynamics of CohI8–CohI9 as a minimal tandem subunit of the scaffoldin protein. Our results show that CohI8–CohI9 transitions on the millisecond timescale between a flexible extended family of structures and compacted states mediated by cohesin–cohesin interactions. The conformational states and dynamic equilibrium are not influenced by shortening of the intercohesin linker. Addition of DocI-containing enzymes preserved the conformational dynamics but showed a higher cohesin–cohesin distance in the extended state. MD simulations identified potential binding modes for the cohesin–cohesin interaction. All stable conformations identified from the MD simulations showed no obstruction of the cohesin–dockerin binding interfaces.

By probing the structural dynamics using four different FRET sensors, we could obtain a detailed understanding of the conformational space of the CohI8–CohI9 fragment. In principle, the different FRET sensors should yield identical results for the kinetic rates. While we obtained good agreement between the different constructs for most parameters, we also observed some deviations. For example, construct 95–260 showed a significantly reduced transition rate to the closed conformation compared with the other constructs. Based on the MD simulations, we could show that this deviation is likely caused by the close proximity of residue T260 to residues involved in the formation of intermodular contacts. Thus, our study also highlights the importance of testing different labeling position in smFRET experiments to ensure that the fluorescent labeling does not drastically alter the properties of the biomolecule or interfere with its function.

To understand the origin of synergistic effects in cellulosomes, it is essential to obtain a detailed global picture of the structural organization and interactions of the individual functional modules. Our study suggests that cohesin–cohesin interactions might play an essential role for the precise spatial arrangement of the various enzymes. The structure of the cellulosome is inherently dynamic and needs to adapt to changing environments to ensure efficient access of the catalytic units to the crystalline cellulose within the complex mesh of hemicellulose, lignin, and pectin. As such, the flexibility of the scaffoldin protein provided by the intercohesin linkers is essential for its structural variability. Once the structural rearrangement is completed, however, cohesin–cohesin interactions may be essential for bringing the catalytic subunits into close contact again to provide the high cellulolytic activity through proximity-induced synergistic effects.

Cohesin–cohesin interactions are also an important factor to be considered in the design of artificial minicellulosomes for industrial applications. These designer cellulosomes are often chimeras of CohI modules from different organisms to allow control of the enzyme composition through orthogonal cohesin–dockerin interactions. Our results indicate that, in addition to the choice of enzymes, the compatibility of the applied cohesin modules and the flexibility of the linker should be considered to maximize the synergistic effects.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression, Purification, and Fluorescent Labeling.

Protein expression and purification were performed as described previously (50). Proteins contained a His6 tag for purification that was not removed. For fluorescent labeling, protein solutions were adjusted to 50 µM and oxygen was removed from the buffer (PBS). Labeling was performed at 10-fold molar excess of the dyes Atto532 and Atto647N (ATTO-TEC) for 3 h at room temperature in the presence of 1 mM TCEP. Unreacted dye was removed by ultrafiltration.

smFRET Measurements.

smFRET experiments were performed using a custom-built setup as described previously (34) that combines PIE (40) with MFD (51). With MFD-PIE, it is possible to determine the FRET efficiency, labeling stoichiometry, fluorescence lifetime, and anisotropy for both donor and acceptor fluorophores for every molecule. Labeled CohI8–CohI9 constructs were diluted to a concentration of ∼100 pM in buffer containing 25 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM CaCl2 at pH 7.25. Unlabeled Cel8A or Cel48S was added at concentrations of 50 nM. Excitation powers of 100 µW were used for both donor and acceptor lasers (as measured at the back aperture of the objective). Bursts were identified using a sliding time window burst search using a time window of 500 µs and a count rate threshold of 10 kHz (52). Filtering of photobleaching and blinking events was achieved through the ALEX-2CDE filter with an upper limit of 10 (38). Further selection of double-labeled molecules was performed using the stoichiometry parameter with a lower limit of 0.45 and an upper limit of 0.80. Accurate FRET efficiencies were calculated based on the intensities in the donor and FRET channels using correction factors for spectral cross talk () of 0.02 and direct excitation of the acceptor fluorophore () of 0.06. Differences in the detection efficiencies and quantum yields of the donor and acceptor fluorophores were accounted for using a -factor of 0.66. The accurate FRET efficiency is then given by the following (34, 53):

| [1] |

where , , and are the background-corrected photon counts in the donor channel after donor excitation, the acceptor channel after donor excitation (FRET signal), and the acceptor channel after acceptor excitation, respectively. Burstwise fluorescence lifetimes of the donor and acceptor fluorophore were determined using a maximum-likelihood estimator approach (34, 54). For the static FRET lines, the donor lifetime in the absence of the acceptor was determined using donor-only molecules from the measurements selected by a stoichiometry threshold (S > 0.98). Contributions of fast linker fluctuations to the static FRET line were accounted for using a Förster radius, R0, of 59 Å and an apparent linker flexibility of 5 Å (32). All data analysis was performed using the open-source software package PAM written in MATLAB (55).

Dynamic PDA.

For the PDA (31, 56), photon counts from selected single-molecule events were rebinned to equal time bins of 0.25-, 0.5-, and 1-ms length, and histograms of the proximity ratio (PR)were computed. The PR is calculated from the raw photon counts in the donor and FRET channels () by the following:

| [2] |

In dynamic PDA, the mixing of states during the fixed observation time as a function of interconversion rates can be solved analytically to describe the dynamic contribution to the observed PR histogram (32). Due to the dynamic interconversion between different states, the shape of the PR histogram changes depending on the time bin size. The data were fit using a two-state dynamic model with the addition of one or two minor static low-FRET states. The width of the respective distance distributions, , was globally fixed at a fraction of the interdye distance, . The proportionality factor was determined from measurements of static double-labeled double-stranded DNA molecules, and thus only accounts for apparent broadening of the distance distribution due to acceptor photophysics (57). This assumption reduces the number of free fit parameters significantly and is justified because no static broadening of the FRET efficiency distribution due to conformational heterogeneity is expected for the studied system. For each dataset, all fit parameters were globally optimized using the PR histograms obtained for the three different time bin lengths (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Species-Selective FCS.

Species-selective fluorescence correlation functions were determined as follows: For every burst, photons in a time window of 50 ms around the edges of the burst were added. If another single-molecule event was found in the time window, the respective burst was excluded. Correlation functions were calculated for every individual burst and averaged to obtain the species correlation function (58, 59).

For fFCS analysis (33), microtime patterns for the low- and high-FRET efficiency species were obtained from subpopulations of the experiments directly using FRET efficiency thresholds (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). Donor and FRET-induced acceptor decays were stacked, and filters were generated separately for the parallel and perpendicular detection channels (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 B–D), which were cross-correlated to circumvent the dead time of the TCSPC hardware and detectors. In this way, the fFCS correlation functions can be calculated down to a limit of 40 ns given our hardware configuration.

FRET-FCS and fFCS curves were fit to a standard single-component diffusion model with up to two kinetic terms, given by the following:

| [3] |

| [4] |

is the diffusion part of the correlation function, where is the average particle number in the confocal volume, is a geometric factor that accounts for the Gaussian shape of the observation volume, is the diffusion time, and is the ratio of the axial and lateral size of the confocal volume. The amplitudes of the kinetic terms are given by and the relaxation times by . For FRET-FCS, the three correlation functions (donor × donor, FRET × FRET, and donor × FRET) were fit using a single kinetic term by globally linking the parameters of the diffusion term and the relaxation time of the kinetic term , and letting the amplitude of the kinetic term assume negative values for the cross-correlation function. For fFCS, the four correlation functions between the two species A and B (A × A, A × B, B × A, B × B) were fit using two kinetic terms by globally linking the parameters of the diffusion term (with exception of the particle number ) and the relaxation times of the kinetic terms , and letting the amplitudes of the kinetic terms for the cross-correlation functions assume negative values.

MD Simulations.

A homology model for the two CohI modules was built using SWISS-MODEL (60–63) based on the crystal structures of CohI9 [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 3KCP] (42) for the CohI9 module, and the crystal structure of CohI7 (PDB ID code 1AOH) (64) for the CohI8 module, with sequence similarities of 98.68% and 95.83%, respectively. Torsion-angle rigid-body MD simulations were performed using the crystallography and NMR system (CNS) (65–68). After addition of the linker peptide and relaxation of the structure, an 80-ns trajectory of the dimer was simulated at 300 K with a time step of 5 fs, treating the cohesin modules as rigid bodies while leaving the covalent bonds in the linker free to rotate. Since the aim of the simulation was to determine equilibrium distances of the extended state, no explicit solvent is included. Every 10 ps, possible positions of the fluorophores were determined using accessible volume (AV) calculations with standard parameters for Atto647N using the FPS software package (36). From the accessible volumes, expected average FRET efficiencies, , are calculated at every time step, , by averaging over all possible combinations of donor and acceptor positions using a Förster radius of 59 Å. The FRET efficiencies, , are averaged over all time steps and converted back to distances, yielding the FRET-averaged expected distances of the simulation. Error bars are determined by bootstrapping.

All-atom MD simulations were performed with the AMBER16 MD package using the ff14SB force field (69). The molecule was solvated in a preequilibrated box of TIP3P water using a truncated octahedron geometry with a minimum distance between solute and the periodic boundaries of 2 nm. The charge of the system was neutralized by addition of 23 sodium ions. Two additional sodium and chloride ions were added, resulting in an excess salt concentration of 2 mM. Initial energy minimization of the extended starting structure was performed using the steepest descent method for 10 steps followed by 190 steps using the conjugate gradient method. For equilibration, the system was heated to 298 K over 50,000 steps with a step size of 2 fs at constant volume, and subsequently run for 50,000 additional steps at 298 K with pressure scaling enabled. Individual MD runs were performed for at least 100 ns at 2-fs step size using the NPT ensemble with the Monte Carlo barostat. Trajectories were written at a resolution of 10 ps. The individual trajectories were obtained using the same equilibrated starting structure with random assignment of the initial velocities. On a single Nvidia GTX 1080 Ti GPU, the simulation typically ran at 50 ns a day. Analysis of the MD trajectories was performed using the cpptraj utility of the AMBER16 software package (70). Clustering was performed using the hierarchical agglomerative algorithm using the average-linkage criterion and a cluster number of 12. Structural figures were generated using University of California, San Francisco, Chimera (71).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alvaro H. Crevenna for help with obtaining homology models for the simulations and Sigurd Vogler for performing initial experiments. A.B. and D.C.L. gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through Grants SFB1035 (Projects A11), and support from the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität through the Center for NanoScience and the BioImaging Network. Y.B. is the incumbent of Beatrice Barton Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1809283115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brett CT, Waldron KW. Physiology and Biochemistry of Plant Cell Walls. 2nd Ed Chapman & Hall; London: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren RA. Microbial hydrolysis of polysaccharides. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:183–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Himmel ME, Bayer EA. Lignocellulose conversion to biofuels: Current challenges, global perspectives. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20:316–317. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jordan DB, et al. Plant cell walls to ethanol. Biochem J. 2012;442:241–252. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doi RH, Kosugi A. Cellulosomes: Plant-cell-wall-degrading enzyme complexes. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:541–551. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontes CMGA, Gilbert HJ. Cellulosomes: Highly efficient nanomachines designed to deconstruct plant cell wall complex carbohydrates. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:655–681. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-091208-085603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert HJ. Cellulosomes: Microbial nanomachines that display plasticity in quaternary structure. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:1568–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fierobe H-P, et al. Degradation of cellulose substrates by cellulosome chimeras. Substrate targeting versus proximity of enzyme components. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49621–49630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207672200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Béguin P, Alzari PM. The cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum. Biochem Soc Trans. 1998;26:178–185. doi: 10.1042/bst0260178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayer EA, Morag E, Lamed R. The cellulosome—a treasure-trove for biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 1994;12:379–386. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamed R, Setter E, Kenig R, Bayer EA. The cellulosome—a discrete cell surface organelle of Clostridium thermocellum which exhibits separate antigenic, cellulose-binding and various cellulolytic. Biotechnol Bioeng Symp. 1983;13:163–181. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tormo J, et al. Crystal structure of a bacterial family-III cellulose-binding domain: A general mechanism for attachment to cellulose. EMBO J. 1996;15:5739–5751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoeler C, et al. Mapping mechanical force propagation through biomolecular complexes. Nano Lett. 2015;15:7370–7376. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvalho AL, et al. Evidence for a dual binding mode of dockerin modules to cohesins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3089–3094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611173104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salamitou S, et al. Recognition specificity of the duplicated segments present in Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelD and in the cellulosome-integrating protein CipA. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2822–2827. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2822-2827.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stahl SW, et al. Single-molecule dissection of the high-affinity cohesin–dockerin complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:20431–20436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211929109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lytle B, Myers C, Kruus K, Wu JH. Interactions of the CelS binding ligand with various receptor domains of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosomal scaffolding protein, CipA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1200–1203. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1200-1203.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaron S, Morag E, Bayer EA, Lamed R, Shoham Y. Expression, purification and subunit-binding properties of cohesins 2 and 3 of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00074-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith SP, Bayer EA. Insights into cellulosome assembly and dynamics: From dissection to reconstruction of the supramolecular enzyme complex. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith SP, Bayer EA, Czjzek M. Continually emerging mechanistic complexity of the multi-enzyme cellulosome complex. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;44:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayer EA, Lamed R. Ultrastructure of the cell surface cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum and its interaction with cellulose. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:828–836. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.3.828-836.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayer F, Coughlan MP, Mori Y, Ljungdahl LG. Macromolecular organization of the cellulolytic enzyme complex of Clostridium thermocellum as revealed by electron microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2785–2792. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.12.2785-2792.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molinier A-L, et al. Synergy, structure and conformational flexibility of hybrid cellulosomes displaying various inter-cohesins linkers. J Mol Biol. 2011;405:143–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammel M, Fierobe H-P, Czjzek M, Finet S, Receveur-Bréchot V. Structural insights into the mechanism of formation of cellulosomes probed by small angle X-ray scattering. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55985–55994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408979200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Currie MA, et al. Scaffoldin conformation and dynamics revealed by a ternary complex from the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:26953–26961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.343897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Currie MA, et al. Small angle X-ray scattering analysis of Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome N-terminal complexes reveals a highly dynamic structure. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:7978–7985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.408757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.García-Alvarez B, et al. Molecular architecture and structural transitions of a Clostridium thermocellum mini-cellulosome. J Mol Biol. 2011;407:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Różycki B, Cazade P-A, O’Mahony S, Thompson D, Cieplak M. The length but not the sequence of peptide linker modules exerts the primary influence on the conformations of protein domains in cellulosome multi-enzyme complexes. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2017;19:21414–21425. doi: 10.1039/c7cp04114d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galera-Prat A, Pantoja-Uceda D, Laurents DV, Carrión-Vázquez M. Solution conformation of a cohesin module and its scaffoldin linker from a prototypical cellulosome. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018;644:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vazana Y, et al. A synthetic biology approach for evaluating the functional contribution of designer cellulosome components to deconstruction of cellulosic substrates. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:182. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antonik M, Felekyan S, Gaiduk A, Seidel CAM. Separating structural heterogeneities from stochastic variations in fluorescence resonance energy transfer distributions via photon distribution analysis. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:6970–6978. doi: 10.1021/jp057257+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalinin S, Valeri A, Antonik M, Felekyan S, Seidel CAM. Detection of structural dynamics by FRET: A photon distribution and fluorescence lifetime analysis of systems with multiple states. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:7983–7995. doi: 10.1021/jp102156t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Felekyan S, Kalinin S, Sanabria H, Valeri A, Seidel CAM. Filtered FCS: Species auto- and cross-correlation functions highlight binding and dynamics in biomolecules. ChemPhysChem. 2012;13:1036–1053. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kudryavtsev V, et al. Combining MFD and PIE for accurate single-pair Förster resonance energy transfer measurements. ChemPhysChem. 2012;13:1060–1078. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carvalho AL, et al. Cellulosome assembly revealed by the crystal structure of the cohesin-dockerin complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13809–13814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1936124100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalinin S, et al. A toolkit and benchmark study for FRET-restrained high-precision structural modeling. Nat Methods. 2012;9:1218–1225. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hellenkamp B, et al. 2017. Precision and accuracy of single-molecule FRET measurements–A worldwide benchmark study. arXiv:1710.03807v2.

- 38.Tomov TE, et al. Disentangling subpopulations in single-molecule FRET and ALEX experiments with photon distribution analysis. Biophys J. 2012;102:1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.11.4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Felekyan S, Sanabria H, Kalinin S, Khnemuth R, Seidel CAM. Analyzing Förster resonance energy transfer with fluctuation algorithms. Methods Enzymol. 2013;519:39–85. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405539-1.00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müller BK, Zaychikov E, Bräuchle C, Lamb DC. Pulsed interleaved excitation. Biophys J. 2005;89:3508–3522. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.064766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kapusta P, Wahl M, Benda A, Hof M, Enderlein J. Fluorescence lifetime correlation spectroscopy. J Fluoresc. 2007;17:43–48. doi: 10.1007/s10895-006-0145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adams JJ, et al. Insights into higher-order organization of the cellulosome revealed by a dissect-and-build approach: Crystal structure of interacting Clostridium thermocellum multimodular components. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:833–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noach I, et al. Modular arrangement of a cellulosomal scaffoldin subunit revealed from the crystal structure of a cohesin dyad. J Mol Biol. 2010;399:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Fiori N, Meller A. The effect of dye-dye interactions on the spatial resolution of single-molecule FRET measurements in nucleic acids. Biophys J. 2010;98:2265–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lamed R, Setter E, Bayer EA. Characterization of a cellulose-binding, cellulase-containing complex in Clostridium thermocellum. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:828–836. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.2.828-836.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morag E, Bayer EA, Lamed R. Unorthodox intrasubunit interactions in the cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1992;33:205–217. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karpol A, et al. Structural and functional characterization of a novel type-III dockerin from Ruminococcus flavefaciens. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Slutzki M, et al. Intramolecular clasp of the cellulosomal Ruminococcus flavefaciens ScaA dockerin module confers structural stability. FEBS Open Bio. 2013;3:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galera-Prat A, Moraïs S, Vazana Y, Bayer EA, Carrión-Vázquez M. The cohesin module is a major determinant of cellulosome mechanical stability. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:7139–7147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vazana Y, Moraïs S, Barak Y, Lamed R, Bayer EA. Interplay between Clostridium thermocellum family 48 and family 9 cellulases in cellulosomal versus noncellulosomal states. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3236–3243. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00009-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eggeling C, et al. Data registration and selective single-molecule analysis using multi-parameter fluorescence detection. J Biotechnol. 2001;86:163–180. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(00)00412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nir E, et al. Shot-noise limited single-molecule FRET histograms: Comparison between theory and experiments. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:22103–22124. doi: 10.1021/jp063483n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee NK, et al. Accurate FRET measurements within single diffusing biomolecules using alternating-laser excitation. Biophys J. 2005;88:2939–2953. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.054114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maus M, et al. An experimental comparison of the maximum likelihood estimation and nonlinear least-squares fluorescence lifetime analysis of single molecules. Anal Chem. 2001;73:2078–2086. doi: 10.1021/ac000877g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schrimpf W, Barth A, Hendrix J, Lamb DC. PAM: A framework for integrated analysis of imaging, single-molecule, and ensemble fluorescence data. Biophys J. 2018;114:1518–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalinin S, Felekyan S, Antonik M, Seidel CAM. Probability distribution analysis of single-molecule fluorescence anisotropy and resonance energy transfer. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:10253–10262. doi: 10.1021/jp072293p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalinin S, Sisamakis E, Magennis SW, Felekyan S, Seidel CAM. On the origin of broadening of single-molecule FRET efficiency distributions beyond shot noise limits. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:6197–6206. doi: 10.1021/jp100025v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eggeling C, Fries JR, Brand L, Günther R, Seidel CA. Monitoring conformational dynamics of a single molecule by selective fluorescence spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1556–1561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laurence TA, et al. Correlation spectroscopy of minor fluorescent species: Signal purification and distribution analysis. Biophys J. 2007;92:2184–2198. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Biasini M, et al. SWISS-MODEL: Modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W252–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guex N, Peitsch MC, Schwede T. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: A historical perspective. Electrophoresis. 2009;30(Suppl 1):S162–S173. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kiefer F, Arnold K, Künzli M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D387–D392. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: A web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tavares GA, Béguin P, Alzari PM. The crystal structure of a type I cohesin domain at 1.7 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:701–713. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brünger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the crystallography and NMR system. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brunger AT, Strop P, Vrljic M, Chu S, Weninger KR. Three-dimensional molecular modeling with single molecule FRET. J Struct Biol. 2011;173:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Choi UB, et al. Single-molecule FRET-derived model of the synaptotagmin 1-SNARE fusion complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Case DA, et al. AMBER 2017. University of California; San Francisco: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roe DR, Cheatham TE., 3rd PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: Software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9:3084–3095. doi: 10.1021/ct400341p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.