Abstract

Introduction

In long-term care (LTC), it is unclear which qualitative instruments are most effective and useful for monitoring the quality of the care relationship from the client’s perspective. In this paper, we describe the research design for a study aimed at finding and optimising the most suitable and useful qualitative instruments for monitoring the care relationship in LTC.

Methods and analysis

The study will be performed in three organisations providing care to the following client groups: physically or mentally frail elderly, people with mental health problems and people with intellectual disabilities. Using a participatory research method, we will determine which determinants influence the quality of a care relationship and we will evaluate up to six instruments in cooperation with client-researchers. We will also determine whether the instruments (or parts thereof) can be applied across different LTC settings.

Ethics and dissemination

This study protocol describes a participatory research design for evaluating the quality of the care relationship in LTC. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre decided that formal approval was not needed under the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act. This research project will result in a toolbox and implementation plan, which can be used by clients and care professionals to measure and improve the care relationship from the client’s perspective. The results will also be published in international peer-reviewed journals.

Keywords: quality in health care, qualitative research, care relationship, participatory research, client perspective, long-term care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study will result in useful optimised instruments for care organisations and client councils to collect information and feedback from clients on care relationships in long-term care.

The participation of client-researchers in the research teams will improve the validity and relevance of the research project and support for it.

The success of the study will depend on the willingness of client-researchers and care organisations to be involved in and contribute to the study.

The success of the implementation will depend on the willingness of care organisations to use the optimised qualitative instruments and the degree of support from national stakeholders.

Introduction

In long-term care, the relationship between clients and care professionals is seen as fundamental for the delivery of high-quality care. This importance is related to the longer period of care provision and the chronic health conditions of clients.1 Long-term care consists of ‘a range of services and assistance for people who, as a result of mental and/or physical frailty and/or disability over an extended period of time, depend on help with their daily living activities and/or need permanent nursing care’.2 A good care relationship between a client and a professional requires an equal relationship in which the professional provides care with dignity and sensitivity to the client’s wishes.3 It allows clients to express any questions or complaints they may have about the care given. This open environment has not yet been achieved in all organisations, according to a recent Dutch study.3 Another study shows that care professionals believe they listen to the needs of clients and offer care in a person-centred manner, but entrenched habits and time pressure mean that opportunities for person-centred communication are often missed.4 Worldwide, there is a drive to redress the imbalance in care from an ethos that is medically dominated, disease orientated and often fragmented to one that is relationship focused.5

Monitoring the quality of the care relationship between a client and a professional should be set up from the client’s perspective. Clients have unique experiential knowledge providing valuable insights into the quality of everyday care and care relationships that are missed otherwise. Care providers, clients and family perceive different determinants as influencing the closeness of the care relationship between the client and care professional. McGilton and Boscart1 showed that care professionals in elderly care felt that close relationships were primarily about feeling connected with the resident. Family members focused primarily on the actions staff took to present a caring attitude. Residents on the other hand felt that close relationships included staff acting as their confidants. By focusing on client experiences, a more comprehensive evaluation of clients’ experiences of the care provided and areas for improvement is generated.6 However, little research in long-term care has focused on the client’s perspective on these relationships.1

An excellent way to include the clients’ perspective is by carrying out participatory research. In participatory research, clients are invited to become part of a research team.7–10 This empowers the clients and improves the validity and relevance of the research project.11 Clients’ involvement can also lead to broader support for the outcomes of the research project and related quality improvement initiatives among clients and care professionals.12 Clients can be involved in several stages of a research project: in preparatory activities or in data collection by actively helping conduct interviews or focus groups.13 14 Client-researchers can also be involved in the data analysis14 or have an advisory role, for example, from the design phase onwards, by constructing the research design, a topic list or by attending steering group meetings.10 13

Clients’ experiences with the quality of a care relationship can be explored using qualitative instruments.15 One advantage of qualitative research is that it aims to understand social phenomena in natural settings, giving due emphasis to the meanings, experiences and wishes of people.16 Qualitative procedures give clients freedom to respond, allowing direct expression of their own concerns rather than those of the researchers.17 As a result, qualitative research can tackle aspects of complex behaviours, attitudes and interactions that are not amenable to quantitative research.16 It has also been shown that care organisations can translate qualitative results more easily into improvement actions, as such results are capable of including the nuances and complexity of care practices.18 19

In Western countries, a shift can be seen in long-term care practice from focusing on solely quantitative instruments to using qualitative instruments for measuring quality.17 For example, interview instruments such as narrative sensibility and storytelling,20 21 focus groups22–25 and observational instruments26–29 are used to improve the relationship between client and care professional and to encourage clients or their relatives to provide feedback. Corresponding to this trend, there is a call for qualitative instruments in the Netherlands that can be used in daily practice to hear clients’ experiences of their care relationship. However, it is not clear whether existing qualitative instruments are useful and effective for monitoring and improving the care relationship from a client’s perspective in long-term care and whether they focus on the important determinants of a good care relationship. Some determinants of a good quality care relationship might differ between client groups, as may the preferred instrument for evaluating the relationship. At the same time, we expect that there will also be general determinants that influence the quality of a care relationship in all LTC settings, such as trust or communications skills.

Aim

The aim of the present paper is to describe the research design of the study. It is a participatory study aimed at finding and optimising qualitative instruments for evaluating care relationships in long-term care from the client’s perspective. This project seeks to answer the following research questions:

What determinants influence the quality of the care relationship in long-term care for the various client groups, according to both clients and care professionals?

What qualitative instruments can be used for monitoring and improving the relationship between clients and care professionals from a client’s perspective?

Which qualitative instruments or parts thereof can be used across client groups and how?

How can the most suitable qualitative instruments be used by the various user groups (such as care professionals, care organisations, client councils and health insurance companies) to improve the quality of the care relationship?

The purpose of the first research question is to understand the determinants that influence the quality of the care relationship in long-term care. The second and third research questions are aimed at evaluating qualitative instruments to ascertain whether they are useful for evaluating the quality of individual care relationships in long-term care across client groups. This research project will result in a toolbox that can be used by professionals and clients to measure and improve the quality of the care relationships in long-term care. The results of this study will be published in peer-reviewed international journals and presented at several congresses, preferably at the annual conference of the international Collaboration for Participatory Health Research and the International Conference on Communication in Healthcare.

Methods and analysis

Setting and participants

The study will take place in the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, long-term care is provided primarily to three client groups: (1) physically or mentally frail older adults, (2) people with mental health problems and (3) people with an intellectual, physical or sensory disability. Our study focuses on these three client groups. However, as regards the third group (people with a disability), we only aim to include clients with intellectual disabilities, as this is by far the largest group of clients with a disability receiving long-term care in the Netherlands. Three Dutch care organisations are willing to be involved in this multicentre study. Each of the three care organisations delivers care to one of the three client groups: one care organisation provides care to physically or mentally frail older adults, another care organisation provides mental healthcare and the third organisation focuses on people with an intellectual disability. A convenience sampling technique was used. To make sure that we can reach a diverse group of clients, we have selected care organisations that provide care to a large client population with a diversity of recurring care needs, that deliver both inpatient and outpatient care and that comprise multiple locations. The three care organisations provide care to more than 2000 clients and have more than 2000 care employees. If one of the care organisations withdraws later on, we will invite another care organisation to become part of the research project.

Respondents and client-researchers

Clients will be involved as client-researchers and respondents in the different phases. Inclusion criteria for both groups are described in table 1. Clients who have at least weekly recurring contact with a care professional and receive care for at least 3 months in/from long-term care organisations will be included. Physically or mentally frail older adults are clients who may need assistance due to somatic complaints or may suffer from mental decline because of dementia. Persons with mental health problems are clients who may suffer from a personality disorder, schizophrenia or an anxiety disorder. An intellectual disability may be caused by chromosome abnormalities or by a brain injury. We will focus on care relationships between clients and care professionals who take care of clients directly, those who see clients most often to provide assistance, supporting care and physical care, for instance, care aides, personal carers and different categories of nurses. Clients will be included if they receive care at least once a week. We will not focus on professionals who are further removed from providing recurrent physical and supporting care, such as clinicians, psychiatrists and general practitioners. Also, clients receiving acute healthcare are outside the scope of this study. Moreover, caregivers who provide informal care will not be included.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for clients as respondents and client-researchers

| Respondents | Client-researchers | |

| 18 years or older (no upper limit) | X | X |

| Currently a client of residential elderly care and home care, mental healthcare or disabled care | X | X |

| Receiving care for at least 3 months | X | X |

| Receiving care at least once a week | X | |

| Able to communicate verbally in Dutch | X | X |

| Able to generalise from their own experiences | X | |

| Able to hold a conversation without the assistance of a close relative or friend | X | |

| Able to read and write at a basic level | X | |

| Has a fairly stable health situation | X | |

| Able to travel short distances | X |

Different inclusion criteria will apply for clients as respondents and client-researchers, as participating client-researchers need to have more skills for active participation. It is important to realise that the client-researchers may not be fully representative of the target group of respondents.

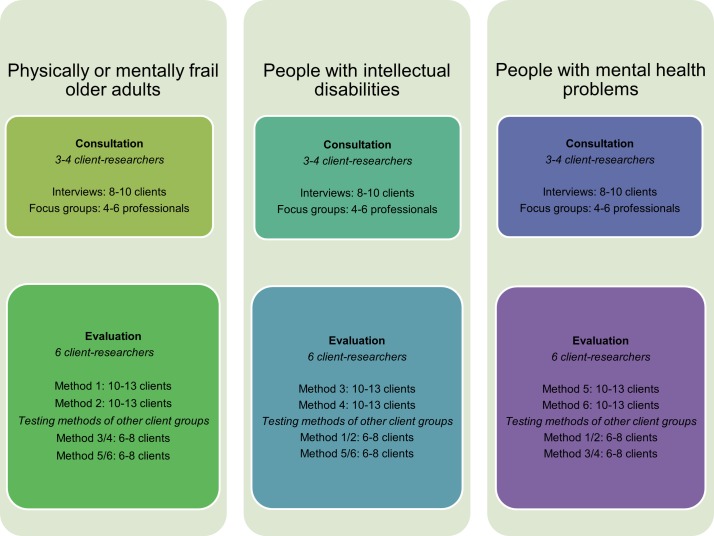

Patient and public involvement

This study is participatory research: having clients participate in this study as client-researchers will help us counteract the social distance between clients and researchers. Gradations of client participation are often described using a participation ladder (see figure 1). The participation levels in Arnstein’s frequently used Participation Ladder are manipulation, therapy, informing, consultation, placation, partnership, delegated power and client control.30 In this study, we are aiming for the ‘partnership’ participation level. Client-researchers will be asked to be involved in preparation activities such as developing the design of the study, formulating a definition of a high-quality care relationship and drafting the topic list for interviews and focus groups and selection of the qualitative instruments that will be tested. Moreover, client-researchers will help in the interviews, focus groups and instrument testing. Some of the client-researchers will also be involved in the selection and invitation of respondents. As members of the research team, client-researchers will be involved in the analysis stage as well: in work meetings, the results of interviews, focus groups and instrument evaluation will be summarised and discussed. At the end of the research, client-researchers can help in the dissemination phase of the research. Earlier studies show there are several barriers for participatory research,10 and sharing responsibilities is not always easy for researchers.31 Studies underline the importance of starting the research process in a really open and flexible way to enable true client participation, empowerment and a valuable collaboration process.10 32 The intensity and manner of participation will be agreed in a group meeting with the client-researchers of each client group. To ensure meaningful cooperation between client-researchers and researchers, we will provide training and an introduction at the start of the research, create a safe working environment and make basic agreements for our cooperation with the client-researchers at the start. During the research phases, we will regularly discuss the conditions for cooperation within the research team. Furthermore, we will communicate in a clear manner, tailored to the literacy and coping level of the client-researchers. Moreover, we will have a researcher available for questions continuously, and we will take the availability of client-researchers into account when planning meetings. Client-researchers will receive an allowance for their contribution, depending on the amount of time invested, not exceeding the maximum payment allowed for those receiving long-term care benefit. Client-researchers will always be able to quit or call off participation during the research process. We added a step halfway through the study in which we will evaluate the process so far with client-researchers and ask them whether they want to continue.

Figure 1.

Ladder of participation (Arnstein).30

Five phases of selection and development of a qualitative instrument

This research consists of five different phases that will take place during the period 2016–2019 (see figure 2): (1) preparation: inviting and selecting client-researchers and a literature study; (2) consultation: individual interviews and focus groups on the determinants of the quality of the care relationship according to clients and care professionals; (3) selection of the most promising qualitative instruments; (4) evaluation: selected qualitative instruments will be tested and evaluated within one client group, with the best qualitative instruments then being tested and evaluated in the other two groups; and (5) dissemination: formulating an implementation plan for the most suitable qualitative instruments.

Figure 2.

Phases of the study.

Supervisory committee

A supervisory committee will supervise the research project from start to finish. A delegation consisting of several stakeholders in long-term care will be invited to be on the supervisory committee. The stakeholders involved are representatives of care providers and branch organisations, client (council) organisations with a nationwide scope, contact persons at the care organisations in the study and health insurers. The committee will monitor the research process according to the project plan and give advice on the content of the study related to national developments. Eight meetings are planned, and members of the supervisory committee can be asked for further input by email if needed. The researchers, including two professors, will attend the meetings.

Preparation

The first phase of this study is the two-part preparation of the research.

Inviting and selecting client-researchers

The invitation of client-researchers will start on a small scale from a personal approach, in cooperation with client council members and care professionals. An individual acquaintance meeting will be held with every client who shows interest in participating. We aim to have three or four client-researchers from each client group. See table 1 for the inclusion criteria. The selected client-researchers will be offered training to prepare for and practice the qualitative interview technique. The training will be provided by the Nivel researchers in two interactive workshops. The topics covered by the training will be tuned to the needs and literacy of client-researchers. In the training, the distribution of tasks and responsibilities will be discussed and established. Tasks and responsibilities will depend on someone’s capacities, capabilities and wishes.

Literature review

Three literature reviews will be conducted:

A systematic review to gain an understanding of determinants influencing the quality of the care relationship.

A scoping review to identify existing qualitative instruments that measure the quality of the relationship between clients and care professionals in the Netherlands.

A scoping review to collect best practices of client participation in long-term care research to determine a participation strategy for client-researchers.

The literature review will include scientific databases such as MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO, and grey literature. For the first review (A), a systematic search strategy will be drawn up. If necessary, a librarian will be consulted during this process. Eligible articles need to be written in English and published in the last 12 years (between 2006 and 2018) due to time constraints. A preselection will be made by one researcher who will screen the titles of all articles. All abstracts then will be screened and assessed by two researchers. If they rate an abstract differently, consensus will be reached in a discussion between the two researchers. If necessary, a third researcher will be involved. Subsequently, two researchers will assess the included articles by reading the full texts. Again, consensus will be reached in a discussion between them if they rate papers differently. If necessary, a third researcher will be involved. The quality of the paper will be rated for all articles included using the criteria of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.33 34

For the second and third review (B and C), we will also carry out a grey literature search in addition to the scientific literature search. Articles eligible for selection need to be written in English or Dutch and published between 2006 and 2018.

Products of the preparation:

Established cooperation with three care organisations and cooperation with three or four client-researchers in each organisation.

A systematic review article of the literature regarding determinants influencing the quality of the care relationship.

An overview of existing qualitative instruments in long-term care in the Netherlands.

Consultation

In the consultation phase, the results from the first (systematic) literature search into determinants of the quality of the care relationship will be supplemented with information from clients involved as respondents and care professionals. In each care organisation, clients will be interviewed individually in semistructured, face-to-face interviews until saturation occurs. It is expected that saturation will occur when we have interviewed 8–10 clients in each care organisation, but it is difficult to determine the saturation point in advance as one size does not fit all in qualitative research.35 Clients who meet the inclusion criteria (see table 1) will be approached by the client-researchers together with the researcher. We will work with a convenience sample to include clients who are willing and able to participate. Even so, we will aim for as much variation as possible in terms of relevant client characteristics such as gender, age, ethnicity and whether they receive care as an inpatient or outpatient.

Interviews will take place in the client’s home or in a meeting room at the care organisation. Depending on the concentration span of each client, interviews will take approximately 30 min. Clients will be asked to give informed consent prior to the start of the interview. In some instances the legal representatives of persons with intellectual disabilities will be asked for permission first. It will be the responsibility of the researcher to make sure the informed consent form is signed. In interviews, we will adopt a ‘process consent’ approach, meaning that we constantly observe during the interview whether consent is still present by paying attention to verbal and non-verbal indications of reluctance or hesitation to participate.36

Additionally, four to six care professionals from each organisation will be invited for a focus group meeting. As with client respondents, we will work with a convenience sample to include professionals who are willing and able to participate. The care professionals will be selected and invited in close cooperation with the care organisation. The focus groups will take about 2 hours and will take place in a meeting room at the care organisation. A topic list will be drawn up in advance to guide the group discussions in a semistructured manner.

The data collection and analysis will be conducted by the research team, consisting of one researcher and three or four client-researchers from each care organisation. The focus groups and interviews will be audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim by an independent transcription agency and analysed in three phases: open coding, axial coding and selective coding.15 The data analysis method is inspired by Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis, which places the clients’ experiences and the meaning they assign to those experiences at the core.37 A portion of the interviews will be analysed by two researchers. If these researchers disagree on the interpretation of a fragment, they will try to reach consensus by discussion. If they do not reach consensus, a third researcher will be consulted. After the construction of the final coding tree, the remaining interviews will be analysed by the first author. The main findings will be discussed by the entire research team in work meetings. The transcripts will be analysed using the qualitative software programme MAXQDA.

Product of consultation

Overview of determinants influencing the quality of the care relationship in the three client groups.

Selection of up to six instruments

Based on the overview of existing qualitative instruments in the Netherlands, the research teams and supervisory committee will select the two most promising qualitative instruments for each client group. The selection will be based on the available information about issues such as corroboration, the fit of the purposes for which the information provided can be used, clear structure, usability of instruments in various client groups, validity and reliability, implementation information and the extent to which clients are involved in applying instruments. The supervisory committee will have input in the formulation of criteria for the assessment and selection of the qualitative instruments. The instruments may include individual interviews, observations, focus groups or combinations thereof. This information will be presented to the supervisory committee using the Delphi method.38 For the selection of instruments, the supervisory committee may be supplemented with other stakeholders, such as representatives of the cooperating care organisations.

Products of the selection:

Overview of assessed qualitative instruments for evaluating the care relationship.

Two instruments per client group that will be evaluated.

Evaluation of qualitative instruments

The purpose of the systematic review and consultation phase is to understand the determinants that influence the quality of the care relationship in long-term care. In the evaluation phase, the selected instruments will be reviewed to ascertain whether they are useful for evaluating the quality of individual care relationships in long-term care. This evaluation phase will consist of three parts.

Adapting the items in the selected instruments

The selected qualitative instruments might need some adaptions in order to be useful for the purpose of this study: to create insight into the experienced quality of the care relationship from a client perspective. Some instruments may have a broader focus on quality of life and quality of care. Therefore, the determinants of the care relationship quality that emerge from the consultation of clients and professionals and the systematic review will be incorporated in additional items if the instrument does not yet cover all relevant determinants of the quality of care relationships. The instrument might also need to be adjusted to be suitable for the participation of client-researchers. For example, the instructions may need to be rewritten using easier words, and the training might have to be adapted to their level of literacy. Furthermore, the selected instruments will be adjusted to suit the specific client group if the instrument is normally used for another client group.

Evaluation of the instruments in one client group

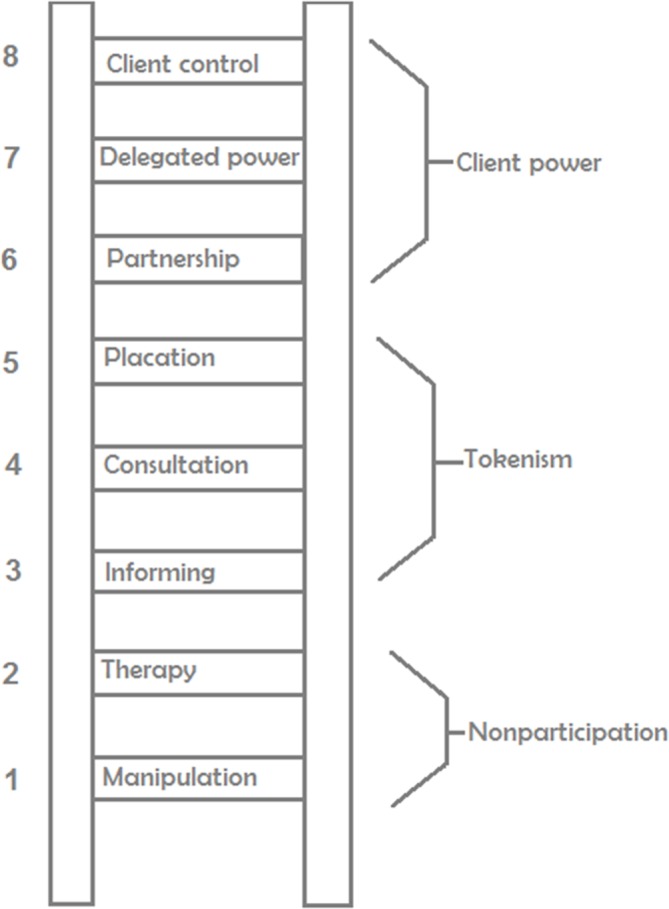

Each instrument will be tested with at least 10 clients and an expected maximum of 13 clients from one of the client groups (see figure 3). It is expected that saturation will occur after this number of clients. The respondents in the evaluation phase will not necessarily be the same respondents as in the consultation phase; it is likely that most respondents will only participate in one phase of this study. We will use the same evaluation criteria as used in the selection phase of the qualitative instruments, supplemented by criteria such as generalisability to other client groups, and information needed for applying the instrument as a client and care professional.

Figure 3.

Research respondents.

Evaluation of the instruments in other client groups

Next, the most promising instrument for each client group will be cross-tested in the other two client groups with six to eight clients. If no instrument appears to be suitable for all three client groups, we will investigate whether there are common elements in the qualitative instruments that can be used in more than one client group. In the case of equal suitability, instruments with generic elements will be preferred over instruments that are solely applicable to one specific client group. This evaluation will lead to a new ranking based on a summary judgement of each qualitative instrument in which the advantages and disadvantages are listed as well as the conditions necessary for successful implementation. These results will be presented to the supervisory committee.

The qualitative instruments will be applied and evaluated with the help of six client-researchers from each client group. In addition, we will include at least 32 clients from each care organisation as respondents in the whole evaluation. They will be approached by their daily care professionals, client-researcher or the client council, who will ask them to take part in the study. A convenience sample technique will be used to include clients who meet the inclusion criteria and are willing and able to participate. Nevertheless, we will aim for as much variation as possible with regard to relevant client characteristics such as gender, age, ethnicity and inpatient or outpatient care.

Products of the evaluation:

Selection of the qualitative instruments that were evaluated as best.

Dissemination

In close cooperation with the client-researchers and participating care organisations, we will develop a toolbox including an implementation plan and the (adjusted) qualitative instruments for measuring and improving the quality of the care relationship for each client group in long-term care. The implementation plan will focus on implementing the qualitative instruments that were selected at the end of the evaluation phase. The toolbox will include a training module to let clients and healthcare providers apply the instrument, plus guidance for the analysis and use of results for improving the care relationship. The toolbox will also describe the levels at which the results of the instrument are expected to be useful, such as the individual care relationship, reflection at the team level or at the organisational level of a care organisation.

We will also examine whether the results of the qualitative instruments can be used for other purposes, such as healthcare procurement by health insurers and monitoring for external accountability on quality measurement and improvement, primarily by the National Health Care Institute. Several meetings will be held with stakeholders, the research team and care organisations in order to disseminate and discuss the results of the project and the implementation plan. Moreover, we will look for opportunities to present the research findings and research products such as the toolbox to interested care organisations and client councils. Client-researchers will be asked to share their experiences by copresenting at various platforms. In this way, they will have an essential role in the implementation and application of the qualitative instruments. The owner of the qualitative instrument will remain responsible for further implementation and dissemination. The National Health Care Institute may also play a role in the dissemination of the instrument.

Product of the dissemination:

Toolbox including the optimised qualitative instruments to measure and improve the quality of the care relationship for each client group in long-term care and the implementation plan.

Recommendations based on external verification of the toolbox.

Ethics

Participants will receive verbal and written information about the research. Participants will provide written informed consent, and process consent will also be used in the interviews with clients.36

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

Prior work has documented the importance of the care relationship for clients in long-term care.1 4 39 In practice, there is a lack of qualitative instruments for evaluating or monitoring the care relationship. We will carry out a study to find and optimise the most suitable qualitative instruments for monitoring the quality of care relationships in long-term care from a client’s perspective. The aim of the present paper is to describe the research design of this study. Due to the differences between client groups in long-term care, it is possible that different instruments will fit each group best. This study will result in a toolbox containing an implementation plan and the optimised qualitative instruments.

Clients will participate in this participatory study as client-researchers. We are therefore working closely with client-researchers in activities such as conducting interviews, preparation activities and analysis. According to Roberts,40 participatory research is more time-consuming than conventional research methods. It takes time to achieve the desired level of trust in a community, and extra time is also needed for the joint process for thinking about the research results. This extra time will be taken into account in the time schedule of this study. In order to create support in the environment and thereby increase the probability of participation by clients, client-researchers, care organisations, client councils and client organisations will cooperate in this study. Their willingness to join is an important prerequisite for the performance of this research. The study depends on the close cooperation of client-researchers, and it is therefore important to work together in an equal, respectful, attentive and open way.40 41 Lessons learnt in previous participatory research will be used to prevent repetition of avoidable errors, such as tokenism, client-researchers facing difficult situations, experienced workload and protoprofessionalisation.32 42 A scoping review will be conducted for this purpose. In order to make the project practically feasible, we will exclude some specific groups in long-term care, such as people with physical or sensory disabilities or people receiving palliative care.

If client-researchers in care organisations carry out one of the optimised instruments from the toolbox, it will provide useful information and feedback for clients and care professionals on the care relationship in long-term care. This makes the research project practically relevant. Nevertheless, this study risks being overshadowed by the everyday demands that care organisations face, which precludes implementation of the selected instrument on a large scale. The likelihood of successful implementation will depend on the willingness of organisations to change their instruments for measuring the quality of the care relationship and the degree of support from national stakeholders. Moreover, the willingness and enthusiasm of client-researchers to be involved in the performance of the instruments will be essential for the implementation and application of the qualitative instruments. The participatory research design and involvement of the supervisory committee will increase the probability that the most preferred instruments will be implemented and disseminated in the field.

The qualitative and participatory research method was chosen to study the experiences of participants and interactions between respondents and client-researchers in natural settings. The research relies heavily on the observational and interviewing skills of researchers and client-researchers and reflectivity on ‘our’ perspectives on the findings. In qualitative research, studying the perspectives of multiple stakeholders and interpreting the results with different client-researchers and researchers is likely to result in an increased understanding of complex phenomena such as care relationships between clients and professionals. This will diminish possible limitations inherently attached to the qualitative research method.16 43 Also, this research takes place on a small scale in three care organisations focused on three client groups within their own contexts. The generalisability to other client groups in other care settings, such as clients with a severe intellectual disability or dementia, may be limited.

From a quantitative design point of view, this study protocol may be interpreted as limited because some details are still left open. To make client participation meaningful, we feel it is not good to define every detail on beforehand to be able to make decisions during the process as well. Therefore, the global structure and decision moments of the research process are described, but at the same time space is left open so that some aspects can be filled in later on. This is not unusual in qualitative research.

Conclusion

In long-term care, care relationships are seen as a fundamental element in the delivery of high-quality care.4 44–46 However, good care relationships have not yet been set up everywhere. It is therefore important that clients, client-researchers, care professionals, client councils and care organisations determine areas in which improvement of the care relationship is possible. As far as we are aware, this will be the first study to use a participatory research design to represent the client perspective in the selection and optimisation of qualitative instruments for monitoring care relationships. Scientific articles will be published to expand scientific knowledge on care relationships in long-term care. This approach allows participatory research to link the practical and scientific purposes. Support for the set of qualitative instruments developed will be generated through the meetings of the supervisory committee and the involvement of client-researchers and care organisations.

Practice implications

The study will result in a toolbox with qualitative instruments that can be used for effective evaluation of the quality of a care relationship. Clients, client councils and care organisations can use the toolbox to monitor the care relationship in a structured way from a client perspective. More generally, the content of this paper may serve as a guideline for developing other studies with the combined purpose of practical outcomes and sharing empirical evidence.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to, reviewed and approved the article drafts and final manuscript. AS was responsible for writing the manuscript, and MH, NB, KL and SvD read several versions of the manuscript and provided their feedback and suggestions regularly.

Funding: This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) (grant number 516012506, 2016).

Disclaimer: The funding organisation played no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, nor in writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Medical Ethics Committee of the Radboud university medical center was asked whether their approval of the study was required under the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. McGilton KS, Boscart VM. Close care provider-resident relationships in long-term care environments. J Clin Nurs 2007;16:2149–57. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Commission spCe. Adequate social protection for long-term care needs in an ageing society. Luxembourg: European Union, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bomhoff M, Paus N, Friele R. Niets te klagen: onderzoek naar uitingen van ongenoegen in verzorgings-en verpleeghuizen, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Savundranayagam MY. Missed opportunities for person-centered communication: implications for staff-resident interactions in long-term care. Int Psychogeriatr 2014;26:645–55. 10.1017/S1041610213002093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCormack B, McCance T. Person-centred nursing: theory and practice: John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open 2013;3:e001570 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blumenthal DS, DiClemente RJ. Community-based participatory health research: issues, methods, and translation to practice: Springer Publishing Company, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hitchen S, Watkins M, Williamson GR, et al. Lone voices have an emotional content: focussing on mental health service user and carer involvement. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2011;24:164–77. 10.1108/09526861111105112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gillard S, Simons L, Turner K, et al. Patient and public involvement in the coproduction of knowledge: reflection on the analysis of qualitative data in a mental health study. Qual Health Res 2012;22:1126–37. 10.1177/1049732312448541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Backhouse T, Kenkmann A, Lane K, et al. Older care-home residents as collaborators or advisors in research: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2016;45:337–45. 10.1093/ageing/afv201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ismail S. Participatory health research: international observatory on health research systems: Rand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vennik F. Interacting patients: the construction of active patientship in quality improvement initiatives, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hitchen SA, Williamson GR. A stronger voice. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2015;28:211–22. 10.1108/IJHCQA-10-2014-0101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nierse CJ, Schipper K, van Zadelhoff E, et al. Collaboration and co-ownership in research: dynamics and dialogues between patient research partners and professional researchers in a research team. Health Expect 2012;15:242–54. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00661.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boeije HR. Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: denken en doen: Boom Koninklijke Uitgevers, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ 1995;311:42–5. 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perreault M, Pawliuk N, Veilleux R, et al. Qualitative assessment of mental health service satisfaction: strengths and limitations of a self-administered procedure. Community Ment Health J 2006;42:233–42. 10.1007/s10597-005-9028-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zuidgeest M, Luijkx KG, Westert GP, et al. Legal rights of client councils and their role in policy of long-term care organisations in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:11 10.1186/1472-6963-11-215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Batterink M. Het in beeld brengen van kwaliteit van leven in de sector Verpleging en Verzorging: Inventarisatie van het gebruik van methoden die kwaliteit van leven in beeld brengen. Significant 2015:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beuthin RE. Cultivating a narrative sensibility in nursing practice. J Holist Nurs 2015;33:98–102. 10.1177/0898010114536633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heliker D. Enhancing relationships in long-term care: through story sharing. J Gerontol Nurs 2009;35:43–9. 10.3928/00989134-20090428-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosen T, Lachs MS, Bharucha AJ, et al. Resident-to-resident aggression in long-term care facilities: insights from focus groups of nursing home residents and staff. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1398–408. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01808.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Munn JC, Dobbs D, Meier A, et al. The end-of-life experience in long-term care: five themes identified from focus groups with residents, family members, and staff. Gerontologist 2008;48:485–94. 10.1093/geront/48.4.485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Larkin M, Boden ZV, Newton E. On the brink of genuinely collaborative care: experience-based co-design in mental health. Qual Health Res 2015;25:1463–76. 10.1177/1049732315576494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jongebreur W, Schipper M, Vunderink L, et al. Het in beeld brengen van kwaliteit van leven in de geestelijke gezondheidszorg: Inventarisatie van het gebruik van methoden die kwaliteit van leven meten in de langdurige geestelijke gezondheidszorg. Significant 2015:1–63. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brooker D. Dementia care mapping: a review of the research literature. Gerontologist 2005;45 Spec No 1:11–18. 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Turjamaa R, Hartikainen S, Kangasniemi M, et al. Living longer at home: a qualitative study of older clients’ and practical nurses’ perceptions of home care. J Clin Nurs 2014;23:3206–17. 10.1111/jocn.12569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zijlmans L. Knowing me, knowing you: on staff supporting people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nijhof E, Vunderink L. Het in kaart brengen van de kwaliteit van bestaan in de gehandicaptenzorg en -ondersteuning: Inventarisatie van instrumenten die worden gebruikt. Significant 2015:1–77. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arnstein SR. A ladder of citizen participation. The City Reader 2015:279. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bindels J, Baur V, Cox K, et al. Older people as co-researchers: a collaborative journey. Ageing Soc 2014;34:951–73. 10.1017/S0144686X12001298 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Armstrong N, Herbert G, Aveling EL, et al. Optimizing patient involvement in quality improvement. Health Expect 2013;16:e36–47. 10.1111/hex.12039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:47–53. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2011. Proposal: a mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report 2015;20:1408. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dewing J. Participatory research A method for process consent with persons who have dementia. Dementia 2007;6:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith JA. Qualitative psychology: a practical guide to research methods: Sage, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Linstone HA, Turoff M. The Delphi method, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abma TA, Oeseburg B, Widdershoven GA, et al. The quality of caring relationships. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2009;2:39–45. 10.2147/PRBM.S4617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Roberts L. Community-based participatory research for improved mental healthcare: a manual for clinicians and researchers: Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes: John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shaw I. How lay are lay beliefs? Health 2002;6:287–99. 10.1177/136345930200600302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. The Lancet 2001;358:483–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Andersen EA. Care aides’ perceptions and experiences of their roles and relationships with residents in long-term care settings. Canada: University of Alberta, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ahlström G, Wadensten B. Encounters in close care relations from the perspective of personal assistants working with persons with severe disability. Health Soc Care Community 2010;18:180–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00887.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brown Wilson CR. Exploring relationships in care homes: a constructivist inquiry. Sheffield: University of Sheffield, 2007:1. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.