Abstract

Deregulation of muscle mitochondrial biogenesis may explain the altered mitochondrial properties associated with aging. Maintenance of the mitochondrial network requires the continuous incorporation of nascent proteins into their subcompartments via the protein import pathway. We examined whether this pathway was impaired in muscle of aged animals, focusing on the subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar mitochondrial populations. Our results indicate that the import of proteins into the mitochondrial matrix was unaltered with age. Interestingly, import assays supplemented with the cytosolic fraction illustrated an attenuation of protein import, and this effect was similar between age groups. We observed a 2.5-fold increase in protein degradation in the presence of the cytosolic fraction obtained from aged animals. Thus, the reduction of mitochondrial content and/or function observed with aging may not rely on altered activity of the import pathway but rather on the availability of preproteins that are susceptible to elevated rates of degradation by cytosolic factors.

Keywords: Mitochondrial biogenesis, Aging, Protein degradation, Chaperones, Protein import machinery

MITOCHONDRIA conduct vital functions in the cell, contributing to calcium homeostasis (1), cholesterol and heme synthesis (2,3), apoptosis (4), and the provision of ATP (5). As such, these organelles provide skeletal muscle with the ability to metabolize substrates, generate energy for locomotion, and provoke cell death. Interestingly, mitochondrial dysfunction, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations, and apoptosis are observed themes in the pathophysiology of aging in skeletal muscle (6–8), connecting the loss of muscle mass (ie, sarcopenia) with mitochondrial dysfunction. Studies reveal an inverse relationship between mitochondrial biogenesis and aging such that as an individual increases in age, mitochondrial content decreases (9–14). Mitochondrial biogenesis refers to the expansion of the existing organelle reticulum, leading to increases in mitochondrial volume and/or improvements in mitochondrial function within the cell (15). This process requires contributions from the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes, necessitating coordinated communication so that multisubunit protein complexes are properly assembled. Because the mitochondrial genome encodes only 13 proteins involved with the electron transport chain, the nuclear genome must account for the remainder (16). Proteins encoded by nuclear DNA are synthesized in the cytosol and are subsequently imported into the mitochondrion via the protein import machinery (PIM) (17). Protein import requires the assistance of cytosolic chaperones, such as heat-shock protein (Hsp) 70, Hsp90, and mitochondrial import stimulation factor (MSF), which bind to and unfold the preprotein (18–20) and direct it to the translocases of outer membrane (TOM) complex of the mitochondrion. Once associated with TOM complex receptors (ie, Tom70, Tom20, and Tom22), the preprotein can be further directed and assembled into one of the four subcompartments of the organelle (21–23).

Matrix-destined proteins contain N-terminal presequences that serve as mitochondrial targeting signals. These presequences direct the preproteins to a specialized network of translocases located in the inner membrane referred to as the Tim23 translocase complex (24). Preproteins are guided into the matrix with the assistance of the presequence translocase–associated motor (PAM) complex, consisting of Pam16, Pam17, Pam18, Tim44, Mge1, and mitochondrial heat-shock protein 70 (mtHsp70) (25–27). The preprotein is then processed to its mature form once inside the matrix by mitochondrial processing peptidase and refolded by the chaperonins Hsp10 and Hsp60. Considering the sheer number of mitochondrial proteins that must be imported, processed, and assembled into the mitochondrion by the PIM, the import pathway appears to serve as a mechanism to regulate the mitochondrial content and function to match the energy needs of skeletal muscle cells. A great deal of research has been devoted to studying this pathway in yeast and plant mitochondria, with a relatively small amount of work focused on mammalian tissues (28–32). Previous research from our laboratory suggests that the protein import pathway may be affected by the aging process such that the rate of preprotein import into cardiac mitochondria was elevated in aged when compared with young animals (33). In addition, the protein expression of cytosolic chaperones was elevated in aged animals. However, whether these alterations in the import of matrix-destined proteins as well as the expression of PIM components also occur within skeletal muscle has not yet been established, particularly within the subsarcolemmal (SS) and intermyofibrillar (IMF) mitochondrial subfractions. Because of the reduced mitochondrial content evident in aging muscle, we hypothesized that this import pathway would be impaired and contributed to the dysfunction of the organelle within this tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Fischer 344 × Brown Norway hybrid (F344BN) rats were studied at 6 months (young) and 35–38 months (aged) of age. These rats are ideal for the investigation of age-related decrements in muscle mass and function as they display a higher resistance to age-related pathologies; have a longer life span compared with other strains; and, most importantly, demonstrate decreases in muscle mass, average fiber cross-sectional area, and peak isometric tetanic tension (34). The animals were anaesthetized with a ketamine and xylazine cocktail (0.2 mL/100 g weight), and the tibialis anterior (TA) and extensor digitorum longus muscles were excised from the hind limb for cytosolic and mitochondrial fractionation and electron microscopy, respectively. For import assays supplemented with the cytosolic fraction, we utilized male Sprague–Dawley rats ranging from 300 to 350 g (2–3 months of age). Thus, for each import assay, the mitochondria were obtained from the same animal in order to evaluate the effect of the cytosolic fraction on precursor ornithine carbamoyltransferase (pOCT) import.

Cytosolic Fractionation and Mitochondrial Isolation

The mitochondria corresponding to the young and aged F344BN and young Sprague–Dawley rats were isolated as described previously (35). The TA muscle was cleaned of connective tissue and fat, minced briefly, weighed, and then homogenized. The SS and IMF mitochondrial subfractions were obtained by differential centrifugation, and the resulting pellets were resuspended in a medium containing 100 mM KCl, 10 mM 3-N-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid, and 0.2% bovine serum albumin. Freshly isolated mitochondria were used for in vitro protein import assays, and aliquots of mitochondrial extracts were stored at −20°C for immunoblotting analyses. To obtain the cytosolic fraction, the supernate was removed after the final centrifugation used to isolate the SS mitochondria and centrifuged at 100,000g for 1 hour at 4°C. The supernate was concentrated in an ultrafiltration cell with a molecular weight cutoff at 10 kDa (Amicon, Beverly, MA) to a volume of <1 mL. The cytosolic fraction was stored at −20°C for import, degradation, and immunoblotting analyses. The protein concentration values of isolated mitochondria and cytosolic fractions were determined using the Bradford method (36).

Electron Microscopy

Muscles were excised and cut at mid-belly to obtain 2- to 3-mm serial sections. Muscle samples were incubated on ice for 1 hour in 3.0% glutaraldehyde buffered with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate. Sections were then washed three times in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer before being postfixed for 1 hour in 1% osmium tetroxide and in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate at room temperature. Muscle sections were then dehydrated by washes with 30%, 50%, 80%, and 100% ethanol, then in ethanol–propylene oxide for 1 hour, followed by 100% propylene oxide for 1 hour. Subsequently, muscle sections were left overnight in a propylene oxide–epon resin mixture in a glass dessicator. Groups of muscle fibers were then dissected from the sections, embedded in fresh resin, and incubated at 60°C for 48 hours. Ultrathin sections (60 nm) were cut, collected on copper grids, and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Electron micrographs were obtained using a Philips EM201 electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR).

DNA Isolation and In Vitro Transcription

The plasmids containing the full-length cDNAs encoding pOCT and precursor malate dehydrogenase (pMDH) were isolated from bacteria using an alkaline lysis method. The cDNAs resulting from this preparation were linearized with SacI (pOCT) and BamHI (pMDH) at 37°C for 2 hours. Plasmid DNA was extracted with phenol and precipitated in ethanol overnight at −80°C. DNA, at a final concentration of 0.8 μg/μL, was transcribed with SP6 RNA polymerase, ribonucleoside triphosphate substrates, and the cap analog m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G at 40°C for 90 minutes. The messenger RNA (mRNA) was extracted with phenol and precipitated in ethanol at −80°C overnight. mRNA pellets were resuspended in sterile distilled water and adjusted to a final concentration of 2.8 μg/μL. Aliquots were stored at −20°C for in vitro translation assays.

In Vitro Translation and Protein Import

The pOCT and pMDH mRNAs were translated and labeled with the use of a rabbit reticulocyte lysate system in the presence of [35S]-methionine. Freshly isolated SS and IMF mitochondria and the translated radiolabeled precursor proteins were equilibrated separately at 30°C for 10 minutes. The translated precursor proteins were added to the mitochondrial samples and incubated at 30°C to initiate the protein import reaction. Equal aliquots of the import reaction were withdrawn at 0, 5, 10, and 20 minutes to determine basal pOCT and pMDH import rates of the young and aged animals. Final import reactions consisted of 25 μg of mitochondria and 12 μL of the lysate containing the radiolabeled precursor proteins. For import reactions containing the cytosolic fraction, the translation products were preincubated with 0 (control), 7.5, or 15 μg of cytosol for 10 minutes at 30°C before the addition of freshly isolated IMF mitochondria to initiate the import reaction. Mitochondria were then recovered by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion for 15 minutes at 4°C. Pellets were resuspended, lysed, and then separated using either 8% (ornithine carbamoyltransferase) or 12% (malate dehydrogenase) sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). After electrophoresis, gels were boiled for 5 minutes in 5% trichloracetic acid, rinsed for 30 seconds in distilled water, followed by rinsing in 10 mM Tris (5 minutes) and 1 M sodium salicylate (30 minutes). Gels were subsequently dried for approximately 1 hour at 80°C and exposed overnight to a Kodak Phosphor screen (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Total intensities were quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississinga, Canada). For import assays without the cytosolic fraction, import was expressed as the percent of processed mature protein (mOCT and mMDH) per minute relative to the total protein available. In the presence of the cytosolic fraction from either young or aged animals, the extent of import was measured as the percent of processed mature protein (mOCT) relative to the total protein available.

Degradation of pOCT

Radiolabeled pOCT was incubated with cytosol isolated from young and aged animals for 120 minutes at 30°C. At 0-, 30-, and 120-minute time points, equal aliquots were withdrawn and placed on ice to establish time- and age-dependent degradation of pOCT. The final reaction contained 2.5 μL of the lysate containing the radiolabeled precursor proteins and 150 μg of cytosolic proteins. Samples were then prepared for SDS-PAGE and subjected to autoradiography. Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was employed to obtain total intensities, and the extent of degradation was measured by comparison to the time-matched control condition where equal volumes of vehicle were incubated with pOCT. Slopes corresponding to these data were compared to determine the effect of age on pOCT degradation rates.

Immunoblotting

Cytosolic and mitochondrial extracts (25–35 μg of protein) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk for 1 hour and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies directed against Tim23 (1:250), Hsp60 (1:1,000), mtHsp70 (1:1,000), adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT; 1:7,500), Hsp70 (1:1,000), Hsp90 (1:1,000), MSF-L (1:2,500), and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:2,000). Membranes were probed with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated rabbit, mouse, or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies. Proteins were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit and quantified densitometrically using SigmaGel software (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). Loading in the mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions was corrected by the total intensities of corresponding ANT and GAPDH, respectively. Antibodies were acquired from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) (GAPDH) and Stressgen Bioreagents (Victoria, Canada) (mtHsp70, Hsp60, Hsp70, and Hsp90). Antibodies for ANT and MSF-L were obtained from Dr. K. B. Freeman (McMaster University, Ontario, Canada) and Dr. K. Mihara (Kyushu University), respectively.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SEM. GraphPad Prism 4 computer software was used to perform statistical analyses. The two-way analysis of variance was used to analyze all import assays and PIM protein expression. The unpaired Student's t test was used for the analyses of protein expression of basal cytosolic chaperones and degradation assays.

RESULTS

Muscle and Body Mass and Mitochondrial Yield

Aged animals were heavier than young animals, as expected, but muscle mass was significantly reduced in the aged animals, presenting evidence of sarcopenia (Table 1). Indeed, the TA muscle mass per unit of body mass in aged animals was only 49% (p < .05) of that found in the young animals. The yield of extractable mitochondria did not differ between aged and young animals.

Table 1.

Animal and Body Weights and Mitochondrial Yield in Young and Old Animals

| TA Muscle Weight (g) | BW (g) | TA/BW × 1,000 | SS Yield (mg/g) | IMF Yield (mg/g) | |

| Young (n = 12) | 0.81 ± 0.02 | 381.91 ± 10.99 | 2.12 ± 0.03 | 1.84 ± 0.13 | 2.70 ± 0.20 |

| Old (n = 12) | 0.53 ± 0.03* | 520.33 ± 14.73* | 1.03 ± 0.06* | 2.02 ± 0.23 | 3.05 ± 0.23 |

Notes: Yields are expressed in milligram mitochondrial protein per gram wet muscle weight. Values are mean ± SEM. BW = body weight; IMF = intermyofibrillar; SS = subsarcolemmal; TA = tibialis anterior.

Significantly different from young animals (p < .05).

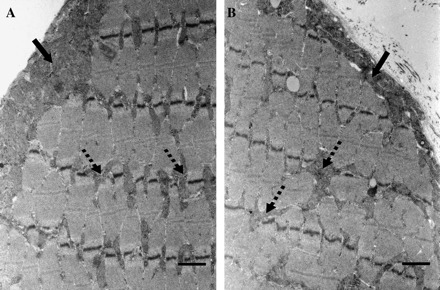

Mitochondrial Content Is Altered With Age in Both Subfractions

We employed transmission electron microscopy to directly assess changes in mitochondrial content occurring in response to age. We observed a modest reduction in the thickness of the SS mitochondrial layer in aged compared with young animals (Figure 1A vs Figure 1B, filled arrows). We also observed that the IMF mitochondrial network from aged animals appeared to be sparse and irregularly distributed among the myofibrils compared with the more regular spacing observed in the muscle of young animals (Figure 1A vs Figure 1B, dashed arrows). These data corroborate our previously observed decrement in total mitochondrial content measured using biochemical indices (9).

Figure 1.

Effect of age on extensor digitorum longus mitochondrial content. Muscles were obtained from young (A) and aged (B) animals. Subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar mitochondrial populations (dark gray areas) are located below the sarcolemmal membrane (filled arrows) and between the myofibrils (dashed arrows). All images were taken at the same magnification and are representative of data acquired from five young and five senescent animals. Scale bar located at the lower right of each picture represents 1 μm.

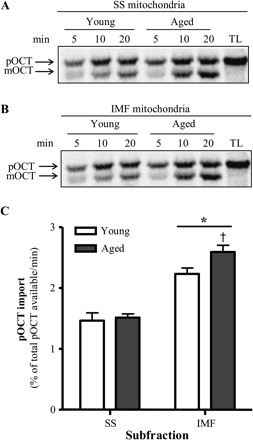

Import of Preproteins Into SS and IMF Mitochondria Is Not Reduced With Age

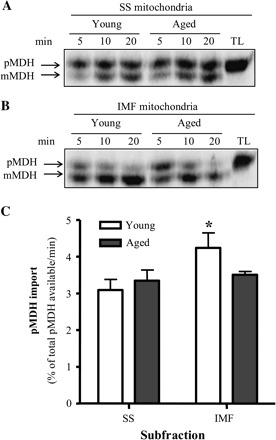

Autoradiograms illustrating the extent of pOCT protein import into IMF and SS mitochondria isolated from young and aged animals are shown in Figure 2. Protein import into SS mitochondria was not significantly different between age groups (Figure 2A and C). Surprisingly, the import of pOCT was modestly higher (16%; Figure 2B and C, p < .05) in IMF mitochondria isolated from aged when compared with young animals. Similar to our previous report (37), protein import was approximately 53% and 72% greater in IMF mitochondria (Figure 2C, p < .05) than in SS mitochondria isolated from young and aged animals, respectively. Autoradiograms illustrating the extent of pMDH protein import into IMF and SS mitochondria isolated from young and aged animals are shown in Figure 3. There was no effect of age on the import of pMDH into either the SS or the IMF mitochondria (Figure 3A–C). The import of pMDH was 37% higher in IMF mitochondria when compared with SS mitochondria; however, this effect was only seen in young animals (Figure 3C, p < .05).

Figure 2.

Effect of age on precursor ornithine carbamoyltransferase (pOCT) import in subsarcolemmal (SS) and intermyofibrillar (IMF) mitochondria. Representative autoradiograms from (A) SS and (B) IMF mitochondrial protein import assays. Upper band represents preprotein OCT (pOCT), and the lower band represents the mature form of OCT (mOCT). Lanes: time course of pOCT import. TL, 5 μL of translated product not incubated with mitochondria. (C) Graphical representation of experiments conducted in SS and IMF skeletal muscle mitochondria isolated from young and aged animals (n = 7–12; *p < .05 vs SS and †p < .05 vs young IMF).

Figure 3.

Effect of age on precursor malate dehydrogenase (pMDH) import in subsarcolemmal (SS) and intermyofibrillar (IMF) mitochondria. Representative autoradiograms from (A) SS and (B) IMF mitochondrial protein import assays. Upper band represents preprotein MDH (pMDH), and the lower band represents the mature form of MDH (mMDH). Lanes: time course of pMDH import. TL, 5 μL of translated product not incubated with mitochondria. (C) Graphical representation of experiments conducted in SS and IMF skeletal muscle mitochondria isolated from young and aged animals (n = 4; *p < .05 vs SS).

Components Involved in the Preprotein Import Pathway Are Not Affected By Age

Tim23, mtHsp70, and Hsp60 are PIM components, which are intimately involved in the translocation and processing of matrix-destined proteins. Representative immunoblots of these proteins are shown in Figure 4A. Quantification of repeated experiments revealed that there were no significant changes in the expression of Tim23, mtHsp70, or Hsp60 in SS or IMF mitochondria in response to age (Figure 4B) when compared with young animals. However, mtHsp70 and Hsp60 content was significantly lower in the IMF compared with the SS mitochondrial subfraction.

Figure 4.

Effect of age on the protein expression of mitochondrial protein import machinery components. (A) Representative Western blots of Tim23, heat-shock protein (Hsp) 60, and mitochondrial heat-shock protein 70 (mtHsp70) content in subsarcolemmal (SS) and intermyofibrillar (IMF) mitochondria isolated from young and aged animals. All blots were corrected for loading using adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT). (B) Graphical representation of experiments using 35 μg of mitochondrial protein per lane (n = 5; *p < .05).

Cytosolic Chaperone Expression Is Affected By Age

Cytosolic chaperones facilitate the import of proteins containing presequence and internal mitochondrial targeting signals. We hypothesized that the expression of Hsp70, Hsp90, and MSF-L in skeletal muscle would be affected by age. Representative immunoblots of these chaperones are shown in Figure 5A. Quantification of experiments revealed that the expression of MSF-L was 2.1-fold higher (p < .05) and Hsp90 was 1.6-fold higher in cytosol isolated from aged when compared with young animals (Figure 5B). There was no significant age-dependent effect on the protein expression of Hsp70.

Figure 5.

Effect of age on chaperone protein expression. (A) Representative Western blots of heat-shock protein (Hsp) 70, Hsp90, and mitochondrial import stimulation factor (MSF)-L content in the cytosolic fractions isolated from skeletal muscle of young (Y) and aged (A) animals. All blots were corrected for loading using glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). (B) Graphical representation of experiments using 30 μg of cytosolic protein per lane (n = 7–10; *p < .05).

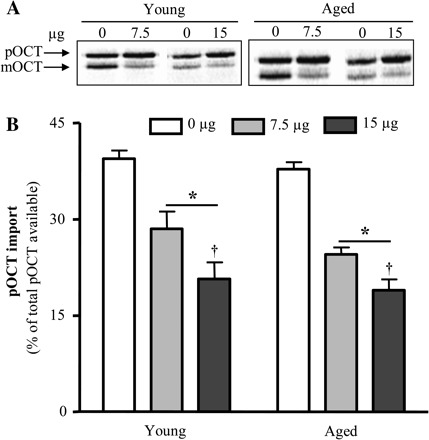

Import of pOCT Is Reduced in the Presence of the Cytosolic Fraction

The elevated expression of chaperones may be an indication that the protein import process is enhanced in aged animals. We have previously reported that factors present in the cytosolic fraction can influence the rate of protein import measured in vitro (28,32). To evaluate these in the context of aging, we measured protein import into mitochondria obtained from a neutral source, muscle from male Sprague–Dawley rats, in the presence and absence of cytosolic fractions isolated from muscle of young and aged animals. Representative autoradiograms and quantification of repeated experiments are shown in Figure 6A. The addition of 7.5 and 15 μg of cytosolic protein isolated from skeletal muscle of young animals resulted in 28% and 47% decreases, respectively, in pOCT import into IMF mitochondria when compared with control (Figure 6B, p < .05). There was no effect of cytosolic fraction on the availability of the precursor protein for import as the pOCT levels remained unaffected with this incubation time frame. The addition of similar amounts of cytosolic protein, isolated from aged animal muscle, resulted in similar 35% and 50% decreases, respectively, in pOCT import into IMF mitochondria when compared with control (Figure 6B, p < .05). Thus, there was no significant effect of age on the inhibitory effect of cytosol on protein import into the matrix.

Figure 6.

Influence of the cytosolic fraction on the import of precursor ornithine carbamoyltransferase (pOCT). (A) Representative autoradiogram of a 20-minute protein import assay. Radiolabeled pOCT (12 μL) and intermyofibrillar mitochondria (25 μg) from Sprague–Dawley rats were supplemented with the addition of 0, 7.5, or 15 μg of the cytosolic fraction. Cytosolic fractions were isolated from the skeletal muscle of young and aged animals. (B) Graphical representation of experiments (n = 6–9; *p < .05 vs 0 μg and †p < .05 vs 7.5 μg).

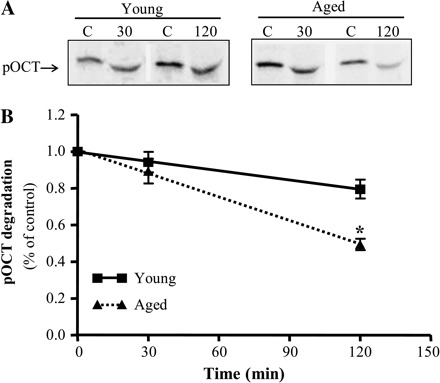

Degradation of pOCT By Cytosolic Proteins Is Dependent On Age

To understand why the presence of the cytosolic fraction did not increase protein import, even in the presence of elevated levels of cytosolic chaperones in aged muscle, we aimed to determine whether pOCT was sensitive to degradation factors found in the cytosol from young and aged skeletal muscle. pOCT was incubated with cytosolic fractions for up to 120 minutes to assess the extent of degradation. The presence of high levels of cytosolic proteins during electrophoresis altered the mobility of the pOCT band slightly, as shown in the representative autoradiograms shown in Figure 7A. However, quantification of experiments revealed a 2.5-fold greater rate of pOCT degradation in the cytosol obtained from aged when compared with young animals (Figure 7B and C, p < .05).

Figure 7.

The effect of age on precursor ornithine carbamoyltransferase (pOCT) degradation. (A) Representative autoradiogram illustrating the degradation of pOCT by the addition 150 μg of the cytosolic fraction for 30 or 120 minutes obtained from young and aged animals. The different mobility of the pOCT in the lanes is likely a function of the presence of cytosolic protein (vs the absence in control [C] lanes in which only buffer was added) in the electrophoresed samples. (B) Graphical quantification of experiments represented as a percent of control (0 μg of cytosolic proteins; C, n = 6–9; *p < .05). Equation for the linear functions: solid line = 1.01–0.0017 (time), r = .66; dashed line = 1.01–0.0043 (time), r = .87; *p < .05, slope of aged vs young degradation lines.

DISCUSSION

Adverse and widespread reductions in muscle function and quality are age-related phenomena collectively known as sarcopenia. Proposed mechanisms of sarcopenia include denervation of muscle fibers via degeneration of the α-motoneuron, decreased satellite cell number, reduced regenerative capacity, decreased protein synthesis, and diminished levels of circulating hormones (38–42). However, recent associations among elevated mitochondrial dysfunction, mtDNA mutations, and mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in sarcopenic skeletal muscle fibers have lent support to an important role for mitochondria in contributing to this loss of muscle mass. Decreases in mitochondrial content and function are evident in aged skeletal muscle (9,12,14,43,44). This may be caused by an impairment of the mechanisms responsible for maintaining or augmenting mitochondrial content and function, otherwise known as mitochondrial biogenesis. The biogenesis of mitochondria is achieved through the increased transcription and translation of mitochondrial proteins that are encoded by both the nuclear and the mitochondrial genomes. Additionally, the incorporation of new proteins into the appropriate organelle compartment is mediated by a highly specialized series of complexes, cumulatively referred to as the mitochondrial protein import pathway (PIM). Because of the importance of this pathway in mediating the translocation of approximately 1,500 proteins, it plays a key role in the overall synthesis of the mitochondrial network. Impaired import of new proteins may lead to faulty multisubunit complex assembly resulting in defective mitochondria that are inefficient in producing ATP, have enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and are more susceptible to apoptosis (9,45–49). Evidence suggests that these are characteristics of mitochondria from aging muscle, which could contribute substantially to the sarcopenia of aging. Thus, we investigated whether skeletal muscle undergoing sarcopenia would exhibit decrements in the mitochondrial protein import pathway.

We have recently reported that aged animals exhibit declines in muscle mass and peak tetanic force, confirming the extent of sarcopenia in our aged animals (9). As shown in the present study, electron microscopy verified that mitochondrial content and distribution were reduced in aged when compared with young animals, and this is matched by a decrease in biochemical markers, such as cytochrome c oxidase (9). Despite these decrements in mitochondrial content, our data reveal that the import of new proteins into the matrix remains intact with age. We have recently reported a similar finding on the import of proteins into the mitochondrial outer membrane of aged animals (50). Interestingly, we noticed a modest age-dependent increase in pOCT import in IMF mitochondria, an effect that has been previously reported in cardiac mitochondria (33). Within mitochondria, several factors may affect protein import into the organelle. These include (a) the PIM components, (b) the rate of ATP synthesis, and (c) the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δχ) (32,38,51). Coincident with the similar rates of protein import between young and aged animals, our analyses revealed that the content of selected PIM components (Tim23, mtHsp70, and Hsp60) was not affected by age. Thus, the age-dependent elevation of pOCT import in IMF mitochondria is not mediated by alterations in these proteins, although the expression of other components (ie, the Tom and Pam complexes) could be altered in response to age. The rate of ATP synthesis, as reflected by State 3 and State 4 respiration, is greater in IMF mitochondria compared with the corresponding SS subfraction, which could account for the differential rates in protein import measured between these organelle subfractions (35,38). Although we have shown that respiration rates in the presence of glutamate and ADP were unaffected by age (9), mitochondria from aged animals displayed significantly lower respiratory control ratios than in young animals (9), indicating a modest degree of uncoupling. This could lead to a reduction in membrane potential (Δχ), which serves to drive the positively charged N-terminus of the preprotein toward the negatively charged matrix environment. Indeed, we observed an age-associated 50% decrease of the Δχ in the SS mitochondria in these aged animals, whereas the Δχ was unchanged with age in the IMF subfraction (9). However, the import of matrix proteins was not reduced in SS or IMF mitochondria from aged animals. Thus, we presume that the Δχ remained sufficiently high to support the insertion of proteins into the matrix compartment in this subfraction. We aim to examine the degree of uncoupling necessary to influence the rate of import into the matrix compartment in future experiments.

In vivo, mitochondrial preproteins interact with cytosolic chaperones that primarily mediate the unfolding and transport of newly synthesized proteins. Thus, within the intact cell, another locus of regulation on protein import lies within the cytosol. We therefore investigated whether the content of selected cytosolic chaperones was altered during senescence. Our observations indicate that the expression of MSF-L and Hsp90 was elevated in aged animals, suggesting that the capacity for cytosol-mediated precursor protein movement toward the organelle is augmented with age. When considered alongside the maintained rate of protein import in mitochondria from aged animals, these data indicate the possibility of a compensatory upregulation in protein import in aged animals in the context of the intact cell. However, when we reconstituted the cellular environment consisting of mitochondria and cytosolic fractions, we observed that there was an impairment of pOCT import in both young and aged animals. This did not appear to be a result of reduced precursor protein availability because the level of pOCT observed in the import reaction remained unchanged within this time frame. Thus, we assume that the cytosolic fraction contains a number of both stimulatory (ie, chaperones) and inhibitory factors, which serve to modulate the import process, and that under the conditions employed, the degree of inhibitory influence exceeded the possible stimulatory effect of the chaperones and that this was unaffected by age. These inhibitory factors likely promote the refolding or aggregation of precursor proteins, making them less competent for import. Interestingly, we have noted that the presence of cytosolic fractions appears to stimulate the import of proteins into the outer membrane (Joseph and colleagues, unpublished data), indicating a compartment-specific effect of the cytosolic fraction.

The final content of mitochondrial proteins within the organelle is also a function of the degradation rate of mitochondrial proteins. We noted that the degradation of nascent pOCT was time dependent and proceeded at a greater rate in the cytosolic fraction obtained from aged animals. Degradation of mitochondrial precursor proteins in the cytosol could be mediated by ROS-induced oxidative modifications and by the ubiquitin–proteasome system (52–55). This could contribute to the inhibition of protein import observed in the presence of cytosol and would attenuate the potential benefit of the higher chaperone expression observed in aged animals.

In summary, our data indicate that while mitochondrial biogenesis declines with senescence, the import of matrix proteins into isolated mitochondria remains unaffected with age. Thus, the decrement in mitochondrial content with age is not a result of a diminished capacity for protein import as determined in vitro. However, further investigation is required to determine whether mitochondrial–cytosolic interactions could attenuate protein import with senescence, possibly in a mitochondrial compartment–specific manner (eg, matrix vs outer membrane), leading to an overall decline in mitochondrial biogenesis with age. Our partial reconstitution of the cellular environment has revealed that other posttranslational modifications of precursor proteins, upstream of their interaction with mitochondrial import machinery components, may be accelerated in aged animals. The enhanced degradation of nascent preproteins could reduce protein import in vivo and may serve as a potential cause for the decline in mitochondrial content and function associated with the sarcopenia of aging.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. K. B. Freeman (McMaster University, Ontario, Canada) for providing the ANT antibody, Dr. K. Mihara (Kyushu University) for providing the MSF-L antibody, Dr. G. C. Shore (McGill University, Montreal, Canada) for supplying the pOCT (pSPO19) vector, and Dr. A. Strauss (Washington University, St. Louis, MO) and Dr. R. M. Payne (Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN) for supplying the MDH (pGMDH) vector. We would like to thank Karen Rethoret for her technical assistance in preparing muscle samples for electron microscopy. D.A.H. holds a Canada Research Chair in Cell Physiology.

References

- 1.Khodorov B, Pinelis V, Vergun O, Storozhevykh T, Vinskaya N. Mitochondrial deenergization underlies neuronal calcium overload following a prolonged glutamate challenge. FEBS Lett. 1996;397:230–234. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontenay M, Cathelin S, Amiot M, Gyan E, Solary E. Mitochondria in hematopoiesis and hematological diseases. Oncogene. 2006;25:4757–4767. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poderoso C, Converso DP, Maloberti P, et al. A mitochondrial kinase complex is essential to mediate an ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation of a key regulatory protein in steroid biosynthesis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Primeau AJ, Adhihetty PJ, Hood DA. Apoptosis in heart and skeletal muscle. Can J Appl Physiol. 2002;27:349–395. doi: 10.1139/h02-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saraste M. Oxidative phosphorylation at the fin de siecle. Science. 1999;283:1488–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiken J, Bua E, Cao Z, et al. Mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations and sarcopenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;959:412–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bua E, McKiernan SH, Aiken JM. Calorie restriction limits the generation but not the progression of mitochondrial abnormalities in aging skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2004;18:582–584. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0668fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herbst A, Pak JW, McKenzie D, Bua E, Bassiouni M, Aiken JM. Accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations in aged muscle fibers: evidence for a causal role in muscle fiber loss. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:235–245. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chabi B, Ljubicic V, Menzies KJ, Huang JH, Saleem A, Hood DA. Mitochondrial function and apoptotic susceptibility in aging skeletal muscle. Aging Cell. 2008;7:2–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conley KE, Marcinek DJ, Villarin J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and age. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10:688–692. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f0dbfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HC, Wei YH. Role of mitochondria in human aging. J Biomed Sci. 1997;4:319–326. doi: 10.1007/BF02258357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menshikova EV, Ritov VB, Fairfull L, Ferrell RE, Kelley DE, Goodpaster BH. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial content and function in aging human skeletal muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:534–540. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reznick RM, Zong H, Li J, et al. Aging-associated reductions in AMP-activated protein kinase activity and mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab. 2007;5:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Short KR, Bigelow ML, Kahl J, et al. Decline in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function with aging in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5618–5623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501559102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hood DA, Irrcher I, Ljubicic V, Joseph AM. Coordination of metabolic plasticity in skeletal muscle. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:2265–2275. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez-Moreno MA, Bornstein B, Petit N, Garesse R. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial biogenesis: towards four decades of mitochondrial DNA research. Mol Genet Metab. 2000;71:481–495. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hood DA, Adhihetty PJ, Colavecchia M, et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis and the role of the protein import pathway. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(1):86–94. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihara K, Omura T. Cytoplasmic chaperones in precursor targeting to mitochondria: the role of MSF and hsp 70. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6(3):104–108. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)81000-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mihara K, Omura T. Cytosolic factors in mitochondrial protein import. Experientia. 1996;52:1063–1068. doi: 10.1007/BF01952103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young JC, Hoogenraad NJ, Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones Hsp90 and Hsp70 deliver preproteins to the mitochondrial import receptor Tom70. Cell. 2003;112:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan NC, Likic VA, Waller RF, Mulhern TD, Lithgow T. The C-terminal TPR domain of Tom70 defines a family of mitochondrial protein import receptors found only in animals and fungi. J Mol Biol. 2006;358:1010–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lister R, Whelan J. Mitochondrial protein import: convergent solutions for receptor structure. Curr Biol. 2006;16(6):R197–R199. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perry AJ, Hulett JM, Likic VA, Lithgow T, Gooley PR. Convergent evolution of receptors for protein import into mitochondria. Curr Biol. 2006;16:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Laan M, Rissler M, Rehling P. Mitochondrial preprotein translocases as dynamic molecular machines. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:849–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frazier AE, Dudek J, Guiard B, et al. Pam16 has an essential role in the mitochondrial protein import motor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;11:226–233. doi: 10.1038/nsmb735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutu DP, Guiard B, Chacinska A, et al. Mitochondrial protein import motor: differential role of Tim44 in the recruitment of Pam17 and J-complex to the presequence translocase. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2642–2649. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Dudek J, Guiard B, Pfanner N, Rehling P, Voos W. The presequence translocase-associated protein import motor of mitochondria. Pam16 functions in an antagonistic manner to Pam18. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38047–38054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craig EE, Chesley A, Hood DA. Thyroid hormone modifies mitochondrial phenotype by increasing protein import without altering degradation. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C1508–C1515. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.6.C1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon JW, Rungi AA, Inagaki H, Hood DA. Effects of contractile activity on mitochondrial transcription factor A expression in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:389–396. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoogenraad NJ, Ward LA, Ryan MT. Import and assembly of proteins into mitochondria of mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1592:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komiya T, Mihara K. Protein import into mammalian mitochondria. Characterization of the intermediates along the import pathway of the precursor into the matrix. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22105–22110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi M, Chesley A, Freyssenet D, Hood DA. Contractile activity-induced adaptations in the mitochondrial protein import system. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1380–C1387. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.5.C1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig EE, Hood DA. Influence of aging on protein import into cardiac mitochondria. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2983–H2988. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.6.H2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blough ER, Linderman JK. Lack of skeletal muscle hypertrophy in very aged male Fischer 344 × Brown Norway rats. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1265–1270. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.4.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cogswell AM, Stevens RJ, Hood DA. Properties of skeletal muscle mitochondria isolated from subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar regions. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:C383–C389. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.2.C383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zor T, Selinger Z. Linearization of the Bradford protein assay increases its sensitivity: theoretical and experimental studies. Anal Biochem. 1996;236:302–308. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi M, Hood DA. Protein import into subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar skeletal muscle mitochondria. Differential import regulation in distinct subcellular regions. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27285–27291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans WJ. Protein nutrition, exercise and aging. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23(suppl 6):601S–609S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nair KS. Aging muscle. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:953–963. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Proctor DN, Balagopal P, Nair KS. Age-related sarcopenia in humans is associated with reduced synthetic rates of specific muscle proteins. J Nutr. 1998;128(suppl 2):351S–355S. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.2.351S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugiura M, Kanda K. Progress of age-related changes in properties of motor units in the gastrocnemius muscle of rats. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1357–1365. doi: 10.1152/jn.00947.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verdijk LB, Koopman R, Schaart G, Meijer K, Savelberg HH, van Loon LJ. Satellite cell content is specifically reduced in type II skeletal muscle fibers in the elderly. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E151–E157. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00278.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker DJ, Betik AC, Krause DJ, Hepple RT. No decline in skeletal muscle oxidative capacity with aging in long-term calorically restricted rats: effects are independent of mitochondrial DNA integrity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:675–684. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.7.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumaran S, Panneerselvam KS, Shila S, Sivarajan K, Panneerselvam C. Age-associated deficit of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle: role of carnitine and lipoic acid. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;280:83–89. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-8234-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bevilacqua L, Ramsey JJ, Hagopian K, Weindruch R, Harper ME. Effects of short- and medium-term calorie restriction on muscle mitochondrial proton leak and reactive oxygen species production. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E852–E861. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00367.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Capel F, Buffiere C, Patureau Mirand P, Mosoni L. Differential variation of mitochondrial H2O2 release during aging in oxidative and glycolytic muscles in rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tonkonogi M, Fernstrom M, Walsh B, et al. Reduced oxidative power but unchanged antioxidative capacity in skeletal muscle from aged humans. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446(2):261–269. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hiona A, Leeuwenburgh C. The role of mitochondrial DNA mutations in aging and sarcopenia: implications for the mitochondrial vicious cycle theory of aging. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marzetti E, Lawler JM, Hiona A, Manini T, Seo AY, Leeuwenburgh C. Modulation of age-induced apoptotic signaling and cellular remodeling by exercise and calorie restriction in skeletal muscle. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joseph AM, Ljubicic V, Adhihetty PJ, Hood DA. Biogenesis of the mitochondrial Tom40 channel in skeletal muscle from aged animals and its adaptability to chronic contractile activity [PhD dissertation] Toronto, Canada: York University; 2008. p. 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mokranjac D, Neupert W. Energetics of protein translocation into mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:758–762. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muratori M, Marchiani S, Criscuoli L, et al. Biological meaning of ubiquitination and DNA fragmentation in human spermatozoa. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2007;63:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Basoah A, Matthews PM, Morten KJ. Rapid rates of newly synthesized mitochondrial protein degradation are significantly affected by the generation of mitochondrial free radicals. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:6511–6517. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wright G, Terada K, Yano M, Sergeev I, Mori M. Oxidative stress inhibits the mitochondrial import of preproteins and leads to their degradation. Exp Cell Res. 2001;263:107–117. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sutovsky P, Van Leyen K, McCauley T, Day BN, Sutovsky M. Degradation of paternal mitochondria after fertilization: implications for heteroplasmy, assisted reproductive technologies and mtDNA inheritance. Reprod Biomed Online. 2004;8(1):24–33. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60495-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]