BACKGROUND

Although significant improvements in childhood cancer treatment have reduced pediatric cancer death rates by nearly 70% over the past four decades, cancer remains the leading cause of death from disease among children and adolescents in the United States.1 With the onset of illness, families must initiate a number of changes in family routines, structure, and functioning, including redistribution of roles and responsibilities among family members. A parent’s ability to cope with the demands associated with their child’s medical and emotional needs is critically important to maintain family functioning, equilibrium and stability over time.2

The distinction between being a single parent (e.g., unmarried/unpartnered), and a ‘lone parent’ (i.e., one who feels alone when caring for a child with cancer, regardless of marital/partnership status) has received little attention. Feeling alone, whether married/partnered or not, is often related to physical separation during hospitalizations, distance from home, family disruption or dysfunction, poor communication or cooperation within the parents’ relationship, and different coping styles between partners3. Better understanding of the experience of the ‘lone’ parent may allow for more accurate identification of parents who are at psychosocial risk.

A Lone Parent Study Group (LPSG),4 consisting of nationally recognized experts in psychosocial aspects of pediatric cancer, designed and conducted an exploratory multi-institutional study of parents of children diagnosed with cancer. Our aims for the current analysis, which highlights key outcomes from the study, were to: (1) characterize parents who perceive themselves to be lone parents or non-lone parents in caring for their child with cancer, and (2) explore and compare lone versus non-lone parents’ perceptions of support and capacity to meet the needs of their child(ren).

METHODS

Design

The study was approved by the IRBs at all 10 participating sites. During routine clinic visits, parents were recruited and asked to complete the Parent Questionnaire (PQ). The study was completed in one visit (<45 mins).

Study Participants

Eligible participants were English or Spanish speaking primary caregivers of children ages 1 to 18 years who were 6–18 months post diagnosis with any malignancy and whose child was still undergoing treatment.

Measures

Parent Questionnaire (PQ):

The PQ was created by the LPSG investigators. A lone parent was defined by an affirmative answer to the question, “When it comes to caring for your child with cancer, do you feel like a single parent?” (those answering “sometimes” or “no” are considered “non-lone” parents regardless of marital status). The PQ assessed the following categories: 1) demographics; 2) perceptions of emotional, financial and logistical support; and 3) ability to meet their children’s basic and emotional needs both before and after the cancer diagnosis.

Analysis

This study is exploratory and intended to provide an overall profile of “lone parents” who care for chronically ill children; data presented are descriptive. Comparisons between lone and non-lone parents are made using chi-square analyses for categorical variables and independent t-tests for continuous variables.

RESULTS

Demographics and Outcomes

N=269, Demographic information is described in Table 1.

Table 1:

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

| Demographic Variable | Lone Parent 29.4% (79) |

Non-Lone Parent 70.6% (190) |

|---|---|---|

| Parent Genderns | ||

| Female | 88.9% (71) | 80.4% (152) |

| Male | 10.1% (8) | 19.6% (37) |

| Parent relationship (mother, father, etc)ns |

||

| Biological mother | 87.3% (69) | 77.9% (148) |

| Biological father | 10.1% (8) | 19.5% (37) |

| Adoptive mother | 0.0% (0) | 1.6% (3) |

| Foster mother | 1.3% (1) | 0.0% (0) |

| Stepmother | 1.3% (1) | 0.5% (1) |

| Other | 0.0% (0) | 0.5% (1) |

| Marital Status3 | ||

| Single | 63.3% (50) | 8.9% (17) |

| Not single | 36.7% (29) | 91.1% (173) |

| Child Agens | 8.7 years (range 1–17) | 7.5 years (range 1–18) |

| Work Statusns | ||

| Part time | 7.6% (6) | 18.4% (35) |

| Full time | 92.4% (73) | 81.1% (154) |

| Stay at home parent | 0.0% (0) | 0.5% (1) |

| Job changesns | ||

| No change | 34.6% (27) | 34.0% (64) |

| Work fewer hours | 14.1% (11) | 23.9% (45) |

| Work more hours | 2.6% (2) | 4.3% (8) |

| On leave/quit/fired | 35.8% (28) | 27.6% (52) |

| Other | 12.8% (10) | 10.1% (19) |

| Household income3 | ||

| Under $24k | 60.8% (48) | 34.2% (65) |

| $24k+ | 39.2% (31) | 65.8% (125) |

| Number of individuals living in home |

||

| Adultsns | Mean = 1.6 | Mean = 1.9 |

| Childrenns | Mean = 2.1 | Mean = 2.2 |

| Caregiving for other individualsns |

||

| Yes | 14.3% (11) | 13.8% (25) |

| No | 85.7% (66) | 6.2% (156) |

1p<.05, 2p<.01,

p<.001,

non-significant

Marital and Parenting Status

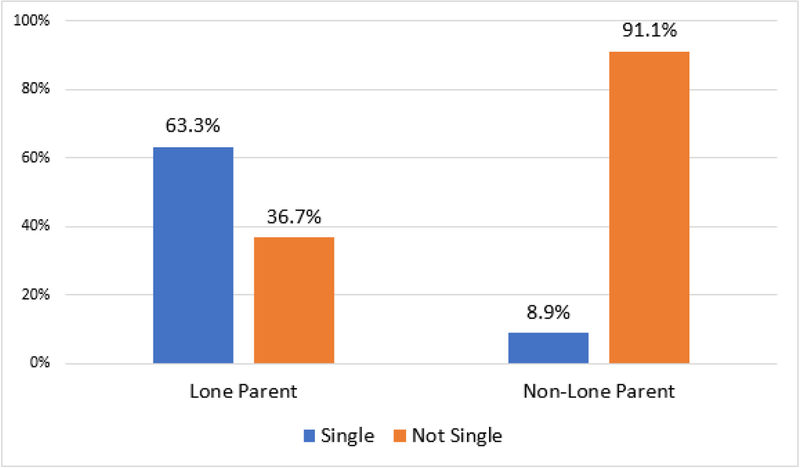

Twenty percent of the sample described themselves as single, with 5% reporting they had a partner they did not live with. The remaining 75% of partipants identified as married or living with a partner. Twenty-nine percent reported being a lone parent, and 71% reported being non-lone. Thirty-seven percent (36.7%) of lone parents identified as not single and 8.9% of non-lone parents identified as single (Figure 1). Of the lone parents, 38.0% said they felt burdened by the responsibility of caring for their ill child.

Figure 1.

Marital Status vs. Parenting Status

Income and Financial Concerns

Sixty-one percent of lone parents had an annual household income under $24,000 versus 34.2% of non-lone parents (p<.001, Table 1). Forty-nine percent of lone parents report ‘a lot’ of financial concerns, vs. 27.1% of non-lone parents (p<.01). Over half of lone parents (57.9%) indicated ‘not having enough money to live on while caring for their sick child’, vs. 38.6% of non-lone parents (p<.01). There were no significant differences between lone and non-lone parents ‘in having someone to turn to for financial support’ (51.9% and 57.4%, respectively).

Perception of Support

Thirty-four percent of lone parents reported having ‘a lot’ of emotional support, vs. 63.5% of non-lone parents (χ2=20.4, p<.001). Twenty-two percent of lone parents reported that they have ‘a lot’ of child care support vs. 50.5% of non-lone parents (χ2=21.6, p<.001). Lone parents are also less likely to report having someone they can ‘really talk to when they are upset’ (71.4% vs. 91.5%, χ2=17.9, p<.001). There were no significant differences between lone and non-lone parents in ‘having someone to turn to for childcare support’ (72.7% vs. 78.1%, χ2=.87, ns).

Ability to Meet Children’s Needs

Lone parents (vs. non-lone) reported lower ability to meet the basic needs of both their child with cancer (72.2% vs 85.2%, χ2=6.3, p<.05) and their other children (42.6% vs. 73.0%, χ2=17.9, p<.001) following diagnosis. While there were no differences between lone and non-lone parents in meeting the emotional needs of their child with cancer post-diagnosis (75.9% vs. 79.4%, χ2=.38, ns), they did report lowered ability to meet their other children’s emotional needs post-diagnosis (33.9% vs. 64.2%, χ2=16.7, p<.001). There were no significant differences between lone and non-lone parents in meeting their children’s basic or emotional needs prior to diagnosis.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the unique needs of parents who feel alone in caring for their child with cancer, over a third of which are not demographically single. Lone parents of children with cancer have greater financial and emotional support needs than non-lone parents and a more difficult time meeting their children’s needs after the diagnosis of cancer. Therefore, if we characterize parents on self-reported marital status alone, we are missing a cohort of parents experiencing additional burdens. Earlier findings from this study reported higher global distress in lone versus non-lone parents of children with cancer and other chronic illnesses, whereas these same differences were not seen when comparing demographically single to not single.5 Additionally, more lone parents than non-lone parents report the quality of their relationship with their ill child’s siblings as having gotten worse since their child’s diagnosis,3 placing siblings at risk for not having their needs met. These cumulative findings suggest that a parent who self-identifies as ‘lone’ is at greater psychosocial risk than some single parents with good support systems, possibly playing a role in how the lone parent functions under stress. To identify these at-risk parents, providers should specifically inquire about perception of lone parenting as part of ongoing assessments of parent and family functioning. This information can facilitate appropriate triage of targeted interventions.

Limitations include the cross-sectional design; longitudinal research will help determine the impact of lone parenting on parental and child health outcomes. We evaluated parents whose child was 6–18 months postdiagnosis, which does not encompass the high-stress periods of time at diagnosis or transition off treatment.6 Future studies may consider gathering input from both members of demographically partnered couples in order to assess more objectively the amount of support being provided to each other, alongside perceptions of being lone. Future research should also examine treatment intensity, family rituals and cohesion,7 and the role of cumulative life stresses on lone parenting with more robust measures.8 A strength of the study was inclusion of parents at 10 pediatric cancer centers and the high response rate (>90%).

In summary, by inquiring on self-reported marital status alone, we potentially miss a cohort of parents experiencing additional burdens. Lone parenting is characterized by low household income and increased financial concerns, lower levels of emotional and child care support, lowered ability to meet their childrens basic and emotional needs, and feeling burdened by the responsibility of caring for their sick child. While demographically single parents may share many of these traits, over one third of lone parents in this study reported not being demographically single. Future research could focus on better delineating these differences and how perceptions may change over time. We recommend that providers consistently inquire whether the parents perceive themselves to be parenting their ill child on their own.

KEY POINTS.

Caring for a child with cancer is a highly stressful experience.

Many parents feel alone in caring for their child with cancer, placing additional burden on family functioning.

The current study sought to describe the experience of parents who feel alone in caring for their child with cancer.

The experience of feeling alone in caring for a child with cancer was not restricted to those who were demographically single.

Lone parents report less financial and emotional support than non-lone parents and greater difficulty in meeting the needs of their child with cancer and their other children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the support and study contributions of the Lone Parent Study Group: David Elkin, PhD, University of Mississippi Medical Center; Sarah Friebert, MD, Akron Children’s Hospital; Julia Kearney, MD, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; Mary Jo Kupst, PhD, Medical College of Wisconsin; Avi Madan Swain, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham; Larry L. Mullins, PhD, Oklahoma State University; Andrea Farkas Patenaude, PhD†, Dana Farber Cancer Institute; and Sean Phipps, PhD, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Sandra Sherman-Bien, PhD, Miller Children’s Hospital.

This work is supported [in part] by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Mental Health intramural programs of the National Institutes of Health. The Andre Sobel River of Life Foundation contributed the gift cards for the study participants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1002/pon.4871

Deceased 29 January 2018

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors have declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Schoors M, Caes L, Verhofstadt LL, Goubert L, Alderfer MA. Systematic review: Family resilience after pediatric cancer diagnosis. J Pediatr Psychol 2015; 40(9): 856–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiener L, Viola A, Kearney J, et al. Impact of Caregiving for a Child with Cancer on Parental Health Behaviors, Relationship quality and spiritual faith: Do lone parents fare worse? J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2016; 33(5): 378–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown R, Wiener L, Kupst MJ, et al. Single parenting and children with chronic illness: An understudied phenomenon. J Pediatr Psychol 2008; 33(4): 408–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiener L, Pao M, Battles H, et al. Socio-environmental factors associated with lone parenting chronically ill children. J Child Health Care 2013; 42:264–280. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffey-Lind EC, O’Holleran E, Healey M, Vettese M, Diller L, Park ER. Transitioning to survivorship: a pilot study. J. Pediatric Oncol Nurs 2006; 23(6): 335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos S, Crespo C, Canavarro MC, Kazak AE. Family rituals and quality of life in children with cancer and their parents: The role of family cohesion and hope. J Pediatr Psychol 2015; 40 (7): 664–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granek L, Rosenberg-Yunger ZRS, Dix D, Klaassen RJ, Sung L, Cairney J, Klassen AF. Caregiving, single parents and cumulative stresses when caring for a child with cancer. Child Care Health Dev 2014; 40 (2): 184–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]