Abstract

Purpose

Both epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) and chemotherapy are widely applied for the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with EGFR mutations, and the combination of EGFR-TKIs and chemotherapy has been used for advanced NSCLC patients; however, little is known about the efficacy of the direct comparison among them.

Patients and methods

The demographic and clinical characteristics of 92 patients harboring advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutation were retrospectively reviewed. We evaluated the effects of EGFR-TKIs, chemotherapy, and EGFR-TKIs plus chemotherapy on advanced NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations, and the efficacy of combination of chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs vs chemotherapy or EGFR-TKIs alone in advanced NSCLC patients was evaluated.

Results

The statistical results showed that the intercalated combination of EGFR-TKIs plus chemotherapy significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS; HR, 1.76; 95% CI 1.03–3.01; P=0.036; median, 20.5 vs 16 months) compared with EGFR-TKI monotherapy, but no difference in overall survival (OS) was observed between these two groups (HR, 1.52; 95% CI 0.81–2.83; P=0.19; median, 36 vs 29 months). However, patients who received the combination of chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs had longer PFS (HR, 2.78; 95% CI 1.57–4.93; P<0.0001; median, 20.5 vs 12 months) as well as OS (HR, 2.86; 95% CI 1.56–5.27; P=0.001; median, 36 vs 18 months) than those who received chemotherapy alone. Toxicities were mild among the three treatment groups. Rash and diarrhea were common adverse events (AEs) in the EGFR-TKI group, anemia and nausea in the chemotherapy group, and anemia and diarrhea in the combination group.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the combination of chemotherapy with EGFR-TKIs as first-line treatment has a significant effect on PFS in patients with advanced NSCLC whose tumors harbor activating EGFR mutations. The combination treatment had more toxicity, but was clinically manageable.

Keywords: non-small-cell lung cancer, epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, chemotherapy, adjuvant therapy, retrospective study

Introduction

Although significant progress was made in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the past 2 decades, current standard chemotherapy options for advanced NSCLC seem to have reached a plateau in terms of efficacy.1,2 Therefore, new therapeutic options are necessary.

Targeted therapies are actively being developed to improve efficacy in selected patient populations. EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs), such as erlotinib or gefitinib, have been found to induce marked clinical improvement in patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC. Many randomized trials showed that first-line EGFR-TKIs are superior to standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with EGFR mutations, which has been developed and considered as the standard treatment for patients with EGFR mutant tumors.3–7 Despite the benefits of EGFR-TKIs in the treatment of NSCLC patients with an EGFR mutation, the prognosis of advanced NSCLC remains poor. To achieve better survival benefit for advanced NSCLC patients, the addition of EGFR inhibitors to standard chemotherapy has become the new focus and was used in clinical treatment, but the results of many studies have been controversial. Most previous clinical trials showed no significant improvement of survival by combining EGFR-TKIs and chemotherapy in unselected advanced NSCLC patients.8–12 By contrast, other clinical trials showed the superior efficacy of the combination of chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs over chemotherapy alone.13–15 Whether the combination of EGFR-TKIs and chemotherapy mode is superior to EGFR-TKIs alone or chemotherapy alone in advanced NSCLC remains controversial.

Based on the abovementioned clinical trial results, we retrospectively evaluated to verify whether the intercalated combination of chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs is superior to chemotherapy alone or EGFR-TKIs alone in the treatment of advanced NSCLC. Otherwise, all the participants in this study had the positive EGFR mutation gene, and this can eliminate the intergroup difference.

Patients and methods

Patients’ characteristics

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 92 patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC in Tangdu Hospital (Xi’an, China) from January 2010 to December 2014. Criteria for use of patients’ data included the provision of signed informed consent for EGFR mutation analysis, a diagnosis of stage IIIb or IV or recurrent NSCLC with a proven EGFR mutation. The study was approved by the review board of the Fourth Military Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to testing. Other inclusion criteria were having adequate hematological function, liver or renal function, and weight loss ≤5% over the previous 3 months. Patients were excluded when they had previous chemotherapy, biologic therapy, immunologic therapy, thoracic irradiation, or incomplete resection of the tumor (patients who had undergo sleeve or wedge resection of the lung tumor were not included in this study). Patients with a history of cardiac disease, prior malignancy, active infection, and coexisting serious unstabilized disease also were ineligible. Tumor histology was classified by the criteria of the third WHO/International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC). Tumor stages were determined using version 7 of the IASLC. The histological subtypes of all patients were reassessed by at least two pathologists.

Treatment

Patients with advanced NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations were assigned to three treatment groups. The EGFR-TKI group consisted of 31 patients treated with EGFR-TKIs as a single agent (22 patients received erlotinib 150 mg per day and nine patients received gefitinib 250 mg per day). The chemotherapy group consisted of 29 patients who received chemotherapy as a single agent (docetaxel 75 mg/m2 plus cisplatin 75 mg/m2 every 21 days for four cycles). The combination group consisted of 32 patients who received chemotherapy (docetaxel 75 mg/m2 plus cisplatin 75 mg/m2 day 1, every 21 days for four cycles) with intercalated EGFR-TKIs (24 patients received erlotinib 150 mg per day and eight patients received gefitinib 250 mg per day). Patients continued to receive EGFR-TKIs or chemotherapy until progression or unacceptable toxicity or death.

EGFR mutation analysis

EGFR mutation testing was performed using an amplified refractory mutation system (ARMS), following the protocol of the AmoyDx EGFR Gene Mutation Detection Kit (Amoy Diagnostics, Xiamen, China), which covers 29 EGFR mutation hotspots from exons 18–21. The assay was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the MX3005P (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) real-time PCR system. The results were analyzed according to the criteria defined by the manufacturer’s instructions. Positive results were defined as Ct (sample) – Ct (control) < Ct (cutoff).

Assessments

Follow-up information was collected every 2 months during the first 6 months after treatment, then every 3 months between 6 and 36 months, and thereafter every 6 months until death. Follow-up examinations involved patients who had a history of cardiac diseases and who underwent, physical examination, hematology, postoperative computed tomography (CT) of the chest, biochemistry, a chest radiograph, upper abdomen, and adverse events (AEs). All AEs were recorded and graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0.

Statistical analyses

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of EGFR-TKI, chemotherapy, and their combination in patients with advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutations. The characteristics of patients were analyzed with the ANOVA test among the three groups. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were defined as the time from assignment to time of death from any cause and time of documented local or distant recurrence of the initial cancer, respectively. The probability of PFS or OS was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. HRs and 95% CIs were estimated by Cox regression. All hypothesis tests were two-sided. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

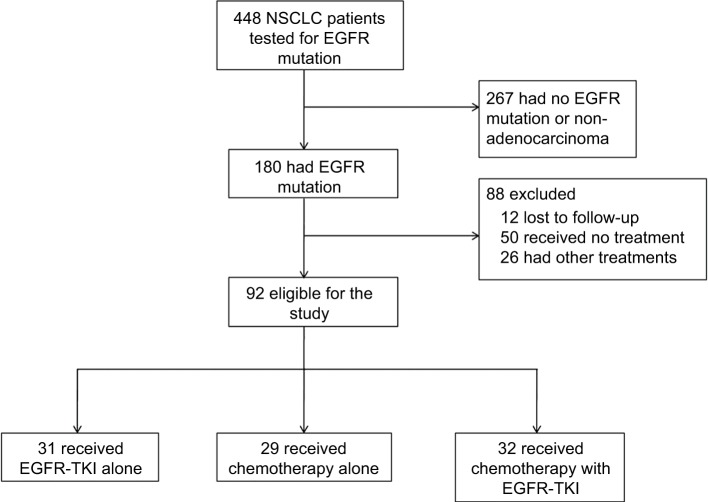

From January 2010 to December 2014, 336 patients with advanced stage were tested for EGFR mutation. Of these patients, 165 had EGFR mutation. After screening, 73 patients were excluded. The remaining 92 patients with advanced stage harboring EGFR mutation were enrolled into the study (Figure 1). A summary of patient baseline characteristics was well balanced across the treatment groups (Table 1). According to patients’ characteristics, 57 (62%) of the patients were female, and the median age was 55 (range, 37–77) years in the EGFR-TKI group, 53 (range, 36–76) years in the chemotherapy group, and 57 (range, 36–79) years in the EGFR-TKI with chemotherapy group. Sixty-nine (75%) of the patients were non-smokers. The most common histology type was adenocarcinoma (91%). Most patients had a performance status of 0 or 1 (76%).

Figure 1.

Scheme for screening and analysis of patients.

Abbreviations: NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Table 1.

Basic clinical characteristics of patients

| Characteristics | EGFR-TKI group | Chemotherapy group | Chemotherapy–EGFR-TKI group |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (years) | |||

| Median | 55 (37–77) | 53 (36–76) | 57 (36–79) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 18 | 20 | 19 |

| Male | 13 | 9 | 13 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Non-smoker | 18 | 24 | 27 |

| Smokera | 13 | 5 | 5 |

| ECOG score | |||

| 0–1 | 24 | 18 | 28 |

| 2–3 | 7 | 11 | 4 |

| Stage of disease | |||

| IIIB | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| IV | 27 | 25 | 27 |

| Histological subtype | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 30 | 24 | 30 |

| Non-adenocarcinoma | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Mutation types | |||

| Exon 19 | 18 | 11 | 20 |

| Exon 21 | 12 | 11 | 10 |

| Others | 1 | 7 | 2 |

Note:

A person who smoked more than 100 cigarettes in his/her past history was defined as an ever smoker.

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

The intercalated combination of chemotherapy and EGFR TKIs versus chemotherapy alone

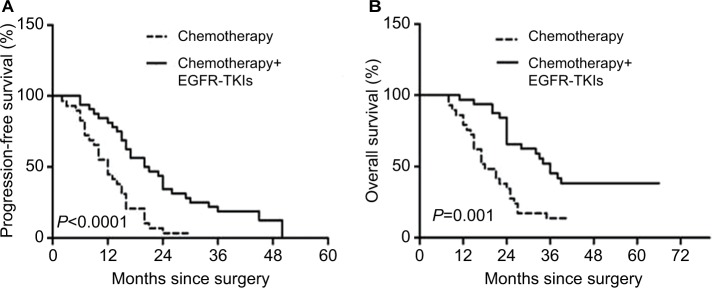

A clinical benefit analysis was performed in 61 patients in the combination group and the chemotherapy group. As compared with the chemotherapy group, patients of the combination group had longer PFS (HR, 2.78; 95% CI 1.57–4.93; P<0.0001; median, 20.5 vs 12 months), and there was a significant difference in OS (HR, 2.86; 95% CI 1.56–5.27; P=0.001; median, 36 vs 18 months) (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B).

Abbreviation: TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

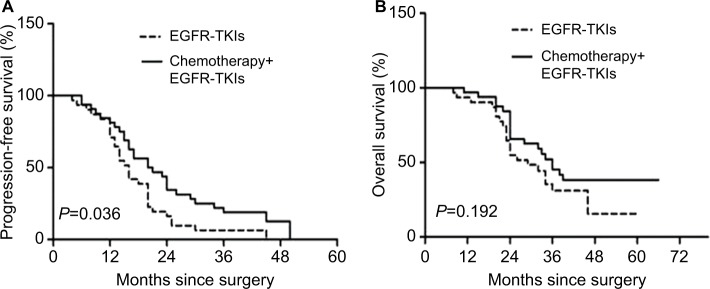

The intercalated combination of chemotherapy and EGFR TKIs versus EGFR TKI monotherapy

Sixty-three patients were included in the clinical benefit analysis, which compared the combination group with the EGFR-TKI group. There was a significant difference in PFS in the combination group when compared with the EGFR-TKI group (HR, 1.76; 95% CI 1.03–3.01; P=0.036; median, 20.5 vs 16 months), but no difference in OS was observed between these two groups (HR, 1.52; 95% CI 0.81–2.83; P=0.19; median, 36 vs 29 months) (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B).

Abbreviation: TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

We used Cox multivariate regression analysis to determine factors influencing survival. The results showed that the combination group treatment was an independent prognostic factor (Table 2). In addition, EGFR mutations were divided into exon 19 deletions, exon 21 mutations, and other mutations. We also found no significant difference in PFS (P=0.06) or OS (P=0.20) for mutations on different exons.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazard model for PFS and OS

| Variables | PFS

|

OS

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 1.252 (0.816–1.920) | 0.304 | 1.147 (0.704–1.868) | 0.583 |

| Sex | 1.112 (0.717–1.724) | 0.634 | 1.187 (0.717–1.965) | 0.506 |

| Smoking history | 0.616 (0.375–1.010) | 0.055 | 0.667 (0.393–1.134) | 0.135 |

| Stage of disease | 0.423 (0.210–0.853) | 0.016 | 0.487 (0..210–1.130) | 0.094 |

| Histological subtype | 0.509 (0.220–1.175) | 0.114 | 0.477 (0.191–1.191) | 0.113 |

| ECOG score | 0.576 (0.352–0.943) | 0.028 | 0.692 (0.398–1.203) | 0.192 |

| EGFR-TKIs plus chemotherapy/chemotherapy | 2.785 (1.574–4.931) | 0.000 | 2.862 (1.556–5.267) | 0.001 |

| EGFR-TKIs plus chemotherapy/EGFR-TKIs | 1.767 (1.038–3.008) | 0.036 | 1.516 (0.812–2.829) | 0.192 |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Comparison of EGFR TKI exposure time

We divided EGFR TKI exposure time into three periods (Table 3). In the EGFR-TKI group, the median PFS in the three groups was 13, 15, and 18 months, respectively. Although patients who received adjuvant EGFR-TKIs for more than 18 months had longer PFS than those who did not, no significant difference in median PFS (P=0.15) was noted in the EGFR-TKI group. In the combination group, the median PFS in the three groups was 17, 22.5, and 24 months, respectively. No statistical significance in median PFS (P=0.54) was noted among these three groups.

Table 3.

Comparisons of EGFR-TKI exposure time

| Months | EGFR-TKI, n (%) | Chemotherapy + EGFR-TKI, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| t>18 | 16 (51.61) | 16 (50) |

| 12< t ≤18 | 9 (29.03) | 7 (21.87) |

| 6< t ≤12 | 6 (19.35) | 9 (28.13) |

Abbreviation: TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Safety

The patients who received at least one dose of treatment were included in the safety analysis. Most AEs were clinically manageable. The most commonly reported AEs of any grade were anemia, rash, neutropenia, nausea, appetite, and diarrhea (Table 4). Rash (25.8%) and diarrhea (32.2%) were more common AEs in the EGFR-TKI group, while anemia (37.9%) and nausea (41.4%) were more common in the chemotherapy group and diarrhea (34.3%) and anemia (37.5%) were more common in the combination group. Most reported AEs were grade 1/2; however, grade 3/4 AEs were 6.5% in the EGFR-TKI group, 17.2% in the chemotherapy group, and 15.6% in the combination group. There was no treatment-related death in the three groups.

Table 4.

Most commonly reported adverse events

| Variables | EGFR-TKI group (N=31) | Chemotherapy group (N=29) | EGFR-TKIs plus chemotherapy group (N=32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade ≥3 | All grades | Grade ≥3 | All grades | Grade ≥3 | |

| Leukopenia | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 7 (24.1) | 1 (3.4) | 5 (15.6) | 0 (0) |

| Neutropenia | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 9 (31) | 1 (3.4) | 6 (18.7) | 1 (3.1) |

| Anemia | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 11 (37.9) | 1 (3.4) | 12 (37.5) | 1 (3.1) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (20.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| Rash | 8 (25.8) | 1 (3.2) | 9 (31) | 0 (0) | 9 (28.1) | 1 (3.1) |

| Diarrhea | 10 (32.2) | 1 (3.2) | 6 (20.7) | 0 (0) | 11 (34.3) | 1 (3.1) |

| Nausea | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (41.4) | 1 (3.4) | 10 (31.2) | 0 (0) |

| Vomiting | 4 (12.9) | 0 (0) | 5 (17.2) | 1 (3.4) | 4 (12.5) | 0 (0) |

| Cough | 6 (19.4) | 0 (0) | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (9.37) | 0 (0) |

| Fatigue | 6 (19.4) | 0 (0) | 8 (27.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (21.8) | 0 (0) |

| Appetite | 5 (16.1) | 0 (0) | 10 (34.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (15.6) | 1 (3.1) |

| Constipation | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Abbreviation: TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Discussion

Over the last decade, major progress has been made in systemic therapies to improve the length of good-quality survival in patients with advanced NSCLC. Chemotherapy has been the standard treatment for NSCLC. Furthermore, TKI therapy has brought major progress in the treatment of patients selected with a molecular marker for their oncogene addiction. Single agent of EGFR-TKIs, either erlotinib or gefitinib, has been demonstrated to be superior to chemotherapy and recommended by NCCN guideline for first-line treatment for EGFR mutation-positive patients.9,12,16,17 In recent years, the success of immunotherapy has highlighted the potential of immune-based therapeutic approaches for NSCLC.18,19 Moreover, the inhibition of the EGFR, such as cetuximab, is a new strategy in the treatment of various solid tumors.

The recent breakthroughs with EGFR-TKIs in the NSCLC seem to be the way forward, but patients inevitably developed resistance to these EGFR inhibitors and present a considerable challenge to optimal clinical advancement. EGFR inhibition was reported to promote epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), increase the number of cancer-associated fibroblasts, and activate Notch expression.20 Recently, some studies showed a direct correlation between EGFR and Notch signaling pathways in multiple types of cancers.21–23 However, EGFR resistance mechanism is extremely complex and need further research. So researchers attempted to improve the efficacy by adding other adjuvant therapies to the treatment regimen or seek new treatment methods.

This study demonstrated that the combination group prominently increased the survival benefit of the treatment of advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutation. Compared with the chemotherapy group, the combination group significantly improved OS and PFS in advanced NSCLC patients with EGFR mutation. The median PFS (20.5 vs 12 months) and OS (36 vs 18 months) of the patients in the combination group were nearly doubled than in the chemotherapy group. Several prospective randomized trials have previously examined the benefit of combining chemotherapy and an EGFR TKI. In unselected patients with advanced NSCLC, Phase III trials have found the combination of TKI and platinum-based chemotherapy to be not better than first-line chemotherapy alone.8,13,14 This may be caused by several factors, one possible mechanism for the failure to significantly benefit from small-molecule TKIs was that patients were not screened and selected for their capability to derive clinical efficacy from EGFR inhibitors, in addition to other factors including type and sequence of administration of the agents, as well as study design. In some other studies,16,24 researchers who were concerned about antagonism between the combination of chemotherapy and EGFR inhibition proposed that pharmacodynamic separation of chemotherapy and erlotinib might improve the effectiveness of the combination. The study by Aerts et al25 was different from this study in that combination chemotherapy planed up to four cycles followed by erlotinib maintenance monotherapy until disease progression. This study revealed that the combination regimen significantly prolonged the median OS compared with erlotinib alone (8.7 vs 5.5 months; P=0.02) but not the median PFS (7.2 vs 4.9 months; P=0.10). But there are insufficient data at present to determine the best approach for this combinatorial strategy, and randomized studies have not provided a clear path for development yet. Therefore, more research studies are required to gain a clear understanding of the reasons.

As shown, the results presented in this study are also consistent with some newer data, which reported that the combination treatment enhances the activity over a single agent. In a recent meta-analysis that compared TKIs plus platinum-based doublet chemotherapy (PBDC) with PBDC alone, the results showed that the combined regimen marginally improved the PFS compared with PBDC alone.26 Pawel et al27 demonstrated that compared with tri-weekly pemetrexed alone, combination with daily 150 mg of erlotinib significantly improved both the median PFS (3.2 vs 2.9 months; P<0.01) and OS (11.8 vs 7.8 months; P=0.019). In FASTACT-II,15 PFS was significantly prolonged with chemotherapy plus erlotinib vs chemotherapy plus placebo (7.6 vs 6.0 months; P<0.0001), and median OS for patients in the chemotherapy plus erlotinib and chemotherapy plus placebo groups was 18.3 and 15.2 months, respectively (P=0.042). A meta-analysis demonstrated that in chemotherapy plus EGFR-TKIs there was significant improvement in OS and PFS compared with chemotherapy alone in advanced NSCLC patients with EGFR mutation-positive tumor.28 These findings demonstrated that the EGFR mutation status may serve as a biomarker to identify patients who can benefit the most from the combination therapy. In other words, these data also demonstrate that intercalated therapy is the most effective combinatorial strategy for NSCLC patients with EGFR mutation, especially those who have little benefit from EGFR-TKI monotherapy.

One major differentiator in this study is the three-group design that allows the comparison of the combination not only vs chemotherapy but also vs the EGFR-TKIs. This study demonstrated that the intercalated EGFR TKI in combination with chemotherapy demonstrated improvements in PFS but not in OS compared with EGFR TKI alone. This finding is supported by the results from some randomized trials. In a randomized study, the median PFS was significantly longer with gefitinib plus pemetrexed than gefitinib alone (18.0 vs 14.0 months; P<0.05), but median OS was similar between the two groups (34.0 vs 32.0 months; P>0.05).29 The system assessment study by Yan et al30 showed that compared with EGFR-TKI monotherapy, the intercalated combination of chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs seemed to be superior to EGFR-TKIs alone in terms of PFS (P=0.004). Another study suggested that East Asian patient treatment with pemetrexed and erlotinib combination experienced a longer median PFS compared with erlotinib or pemetrexed alone (P=0.004 vs erlotinib; P=0.001 vs pemetrexed).31 In an open-label, randomized, Phase II study, PFS was significantly longer with pemetrexed plus gefitinib than with gefitinib alone in patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC with activating EGFR mutations (15.8 vs 10.9 months; P=0.029).32 These data indicate that in selected patients EGFR-TKIs plus chemotherapy may prolong PFS. However, study about the combination of EGFR-TKIs with chemotherapy compared with EGFR-TKIs alone is very few at present and remains to be confirmed.

Although there were no statistical significant differences in PFS and OS in different EGFR TKI exposure time either in the EGFR-TKI group or in the combination group, patients who received EGFR-TKIs for more than 18 months were found to have a slightly longer PFS and OS. However, study about the comparison of the duration of EGFR TKI treatment is required to build a database and remains to be confirmed.

Toxicities related to three groups were mild and well tolerated. As expected, reported AEs in the combination group were similar to those observed in the EGFR-TKI group and the chemotherapy group, with little additive toxicity. The most common AEs were skin/subcutaneous and gastrointestinal disorders. However, of those related AEs, most could be managed and no patient withdrew as a result of related AEs in the three groups. The serious AE rate was low among study groups.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the combination of EGFR TKI with chemotherapy treatment significantly improved OS and PFS compared with chemotherapy alone for advanced NSCLC patients harboring EGFR mutations and significantly improved PFS compared with EGFR-TKI monotherapy. In other words, these data demonstrate that intercalated therapy is the most effective combinational strategy. However, there were several limitations to this study. The sample size of patients was small. Also, this was a retrospective study based on the data of a previous clinical trial. To obtain more convincing data, additional studies are required to evaluate the clinical value of such intercalated combination in patients with EGFR mutations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xin Yin for his help to conduct this study. Finally, we would like to thank all members of our research team, who collaborated to ensure the study proceeded smoothly.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Park K, Goto K. A review of the benefit-risk profile of gefitinib in Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(3):561–573. doi: 10.1185/030079906X89847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Spanish Lung Cancer Group in collaboration with Groupe Français de Pneumo-Cancérologie and Associazione Italiana Oncologia Toracica Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. West Japan Oncology Group Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(2):213–222. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CK, Brown C, Gralla RJ, et al. Impact of EGFR inhibitor in non-small cell lung cancer on progression-free and overall survival: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(9):595–605. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herbst RS, Prager D, Hermann R, et al. TRIBUTE Investigator Group TRIBUTE: a phase III trial of erlotinib hydrochloride (OSI-774) combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):5892–5899. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auliac JB, Chouaid C, Greillier L, et al. GFPC team Randomized open-label non-comparative multicenter phase II trial of sequential erlotinib and docetaxel versus docetaxel alone in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of first-line chemotherapy: GFPC 10.02 study. Lung Cancer. 2014;85(3):415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jänne PA, Wang X, Socinski MA, et al. Randomized phase II trial of erlotinib alone or with carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients who were never or light former smokers with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: CALGB 30406 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2063–2069. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatzemeier U, Pluzanska A, Szczesna A, et al. Phase III study of erlotinib in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Tarceva Lung Cancer Investigation Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1545–1552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbst RS, Giaccone G, Schiller JH, et al. Gefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial--INTACT 2. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(5):785–794. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DH, Lee JS, Kim SW, et al. Three-arm randomised controlled phase 2 study comparing pemetrexed and erlotinib to either pemetrexed or erlotinib alone as second-line treatment for never-smokers with non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(15):3111–3121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao YY, Zhan P, Yuan DM, et al. Chemotherapy plus multitargeted antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors or chemotherapy alone in advanced NSCLC: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(2):151–159. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu YL, Lee JS, Thongprasert S, et al. Intercalated combination of chemotherapy and erlotinib for patients with advanced stage non-small-cell lung cancer (FASTACT-2): a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(8):777–786. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giaccone G, Herbst RS, Manegold C, et al. Gefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial–INTACT 1. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(5):777–784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riely GJ, Rizvi NA, Kris MG, et al. Randomized phase II study of pulse erlotinib before or after carboplatin and paclitaxel in current or former smokers with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(2):264–270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bansal P, Osman D, Gan GN, Simon GR, Boumber Y. Recent advances in immunotherapy in metastatic NSCLC. Front Oncol. 2016;6:239. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manegold C, Dingemans AC, Gray JE, et al. The potential of combined immunotherapy and antiangiogenesis for the synergistic treatment of advanced NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(2):194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitz S, Bindea G, Albu RI, Mlecnik B, Machiels JP. Cetuximab promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cancer associated fibroblasts in patients with head and neck cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(33):34288–34299. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arasada RR, Amann JM, Rahman MA, Huppert SS, Carbone DP. EGFR blockade enriches for lung cancer stem-like cells through Notch3-dependent signaling. Cancer Res. 2014;74(19):5572–5584. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espinoza I, Miele L. Notch inhibitors for cancer treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;139(2):95–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu Hu S, Li WT, et al. Antagonism of EGFR and Notch limits resistance to EGFR inhibitors and radiation by decreasing tumor-initiating cell frequency. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(380):eaag0339. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mok TS, Wu YL, Yu CJ, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II study of sequential erlotinib and chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(30):5080–5087. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aerts JG, Codrington H, Lankheet NA, et al. A randomized phase II study comparing erlotinib versus erlotinib with alternating chemotherapy in relapsed non-small-cell lung cancer patients: the NVALT-10 study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(11):2860–2865. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen P, Wang L, Liu B, Zhang HZ, Liu HC, Zou Z. EGFR-targeted therapies combined with chemotherapy for treating advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(3):235–243. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0965-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pawel J, Papai-Szekely Z, Vinolas N, et al. A randomized phase II study of pemetrexed plus erlotinib in second-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic, nonsquamous NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2011:297526abstr. [Google Scholar]

- 28.La Salvia A, Rossi A, Galetta D, et al. Intercalated chemotherapy and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18(1):23–33.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An C, Zhang J, Chu H, et al. Study of gefitinib and pemetrexed as first-line treatment in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR mutation. Pathol Oncol Res. 2016;22(4):763–768. doi: 10.1007/s12253-016-0067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan H, Li Q, Wang W, Zhen H, Cao B. Systems assessment of intercalated combination of chemotherapy and EGFR TKIs versus chemotherapy or EGFR TKIs alone in advanced NSCLC patients. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15355. doi: 10.1038/srep15355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee DH, Lee JS, Wang J, et al. Pemetrexed-Erlotinib, Pemetrexed Alone, or Erlotinib Alone as Second-Line Treatment for East Asian and Non-East Asian Never-Smokers with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Nonsquamous Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: Exploratory Subgroup Analysis of a Phase II Trial. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47(4):616–629. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng Y, Murakami H, Yang PC, et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Gefitinib With and Without Pemetrexed as First-Line Therapy in Patients With Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With Activating Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(27):3258–3266. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.9218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]