Abstract

Context:

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex, chronic, and under-recognized disorder. Diagnosis experience may have lasting effects on well-being and self-management.

Objective:

To investigate PCOS diagnosis experiences, information provided, and concerns about PCOS.

Design:

Cross-sectional study using an online questionnaire.

Setting:

Recruitment via support group web sites in 2015 to 2016.

Participants:

There were 1385 women with a reported diagnosis of PCOS who were living in North America (53.0%), Europe (42.2%), or other world regions (4.9%); of these, 64.8% were 18 to 35 years of age.

Main Outcome Measures:

Satisfaction with PCOS diagnosis experience, satisfaction with PCOS information received at the time of diagnosis, and current concerns about PCOS.

Results:

One-third or more of women reported >2 years (33.6%) and ≥3 health professionals (47.1%) before a diagnosis was established. Few were satisfied with their diagnosis experience (35.2%) or with the information they received (15.6%). Satisfaction with information received was positively associated with diagnosis satisfaction [odds ratio (OR), 7.0; 95% confidence interval (CI), 4.9 to 9.9]; seeing ≥5 health professionals (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.8) and longer time to diagnosis (>2 years; OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.6) were negatively associated with diagnosis satisfaction (independent of time since diagnosis, age, and world region). Women’s most common concerns were difficulty losing weight (53.6%), irregular menstrual cycles (50.8%), and infertility (44.5%).

Conclusions:

In the largest study of PCOS diagnosis experiences, many women reported delayed diagnosis and inadequate information. These gaps in early diagnosis, education, and support are clear opportunities for improving patient experience.

In the largest international study of PCOS diagnosis experiences, delayed diagnosis and a lack of adequate consumer health information are common and associated with poor patient experience.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine condition affecting 9% to 18% of reproductive-aged women (1–3). Diagnosis commonly requires at least 2 of the 3 following features: polycystic ovaries on ultrasound, biochemical/clinical hyperandrogenism, and oligo/amenorrhea, with exclusion of other etiologies (4). Despite the high prevalence, PCOS is an underrecognized condition, and many women remain undiagnosed (1).

PCOS affects health and well-being over the life span (5, 6). It is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility (7), and women with PCOS have greater prevalence type 2 diabetes (8), risk factors for cardiovascular disease (8), and symptoms of anxiety and depression (9, 10). PCOS is exacerbated by obesity (11), and lifestyle management (weight management or loss, healthy diet, and exercise) and the oral contraceptive pill are first-line treatments (12, 13).

A previous Australian survey highlighted that PCOS diagnosis is often delayed, involves many health professionals, and leaves women with unmet information needs (14). These experiences may have long-term consequences, with a reported association between the length of time to receive a PCOS diagnosis and both anxiety and depression symptoms (15). Diagnosis experience could also affect self-management and the ability to improve lifestyle, the information sources that women access, and participation in regular screening for metabolic complications (16, 17). Despite these potential impacts, there have been few comprehensive studies investigating diagnosis experience. Information needs have been investigated in PCOS (16–19), but studies have been small or limited in scope.

This study aimed to investigate women’s diagnosis experiences, information provided, main concerns about PCOS, and support needs in a large group of women with PCOS, primarily in North America and Europe. The findings will inform an international initiative to improve diagnosis and education to better meet women’s needs and optimize early engagement with evidence-based management. This international approach builds on prior research about PCOS diagnosis experiences in Australia and investigates how women’s needs may differ in different regions.

Methods

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (protocol number: 822252). Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Completion of the survey was taken as consent to participate in the study.

Study design, setting, and participants

In this cross-sectional study, a community sample of women were asked to complete an online questionnaire in 2015 and 2016. The questionnaire was disseminated via the Web sites of the 2 largest PCOS support organizations worldwide: PCOS Challenge (United States) and Verity (United Kingdom). The link to the online questionnaire was accessible to Web site visitors, e-mailed to women on PCOS support organization mailing lists, and promoted through social media. Eligibility criteria included age ≥18 years and a prior diagnosis of PCOS made by a doctor.

Tools

This questionnaire was adapted from a PCOS questionnaire previously used in published research (14). The original questionnaire was developed with input from a multidisciplinary expert advisory group and piloted with women with PCOS (14). The results from the previous study, national forums with women, clinicians, and academics (20), and experiences of international experts informed the refined questionnaire used here. It included demographics, PCOS diagnosis experience, information provided at diagnosis, current concerns about PCOS features, and support needs (Supplemental File 1). No question was compulsory. Reponses were collected using SurveyMethods software (SurveyMethods, Inc., Allen, TX) and then exported and analyzed by the authors.

Variables and statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata software version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Categorical data are presented as count and proportions. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Logistic regression analyses: diagnosis experience

Univariable logistic regression analyses generated crude odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between world region of residence [North America (reference category), Europe, and other] and aspects of PCOS diagnosis experience. These included time since diagnosis, time from first seeing a health professional about PCOS symptoms to when a diagnosis was established, number of health professionals seen before receiving a diagnosis, satisfaction with their diagnosis experience, and satisfaction with the information received about PCOS at the time of diagnosis.

Univariable logistic regression analyses then tested for associations between overall satisfaction with diagnosis experience and potential contributors. These included number of health professionals seen [1 to 2 (reference category), 3 to 4, or ≥5], time to diagnosis [within 6 months (reference category), within 12 months, within 2 years, or >2 years], satisfaction with information provided [dissatisfied or indifferent (reference category) or satisfied], time since diagnosis [≤1 year (reference category), 1 to 5 years, 5 to 10 years, or >10 years], age [18 to 25 years, 26 to 35 years (reference category), 36 to 45 years, or >45 years], and world region of residence [North America (reference category), Europe, or other]. These 6 variables were then included in a multivariable logistic regression analysis of overall satisfaction with diagnosis experience.

Logistic regression analyses: information provision at diagnosis

Univariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to test for associations between world region of residence [North America (reference category), Europe, or other] and receiving information about particular topics at the time of diagnosis, and satisfaction with received information. Topics included lifestyle management, medical therapy, long-term complications, and emotional support and counseling. Multivariable logistic regression analyses then adjusted for age and time since diagnosis.

Logistic regression analyses: current concerns about PCOS

Univariable logistic regression analyses assessed associations between the leading current concerns (selected by ≥10% of participants) or preferred types of support, and age or world region.

Results

Participation and demographics

A total of 1550 questionnaire responses were received. Of these, 165 were excluded: 1 was <18 years of age, 67 had not been diagnosed with PCOS by a doctor, and 97 had completed less than one-half of the questionnaire. The remaining 1385 women were born in 48 different countries and lived in 32 different countries (Table 1). Approximately one-half of the participants were aged 26 to 35 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants: Women With PCOS

| Demographic characteristic | No. of Women (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y (n = 1381) | |

| 18–25 | 190 (13.8) |

| 26–35 | 705 (51.0) |

| 36–45 | 390 (28.2) |

| >45 | 96 (6.9) |

| World region of birth (n = 1382) | |

| North Americaa | 689 (49.9) |

| Europeb | 568 (41.1) |

| Oceaniac | 39 (2.8) |

| Asiad | 37 (2.7) |

| Central, Latin, and South America and Caribbeane | 32 (2.3) |

| Africaf | 17 (1.2) |

| World region of residence (n = 1382) | |

| North Americaa (United States: n = 693; Canada: n = 39) | 732 (53.0) |

| Europeg | 583 (42.2) |

| Otherh | 67 (4.8) |

United States of America and Canada.

Bosnia and Herzegovina, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, and United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Australia and New Zealand.

Azerbaijan, China, India, Iran, Japan, Jordan, Lebanon, Malaysia, Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela.

Algeria, Egypt, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, Somalia, South Africa, and Zambia.

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (n = 517), Southern Europe (n = 37), Northern Europe (n = 19), Western Europe (n = 8), and Eastern Europe (n = 2).

Australia (n = 35), Africa (n = 10), Southern Asia (n = 7), Western Asia (n = 6), Eastern and Southeastern Asia (n = 5), and Central, Latin, and South America and Caribbean (n = 4).

Diagnosis experience

Nearly one-half of the participants saw ≥3 health professionals before a PCOS diagnosis was established, and for one-third this took >2 years (Table 2). Only 35.2% were satisfied with their diagnosis experience, and only 15.6% were satisfied with the information about PCOS provided at the time of diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

PCOS Diagnosis Experience

| Perceptions of PCOS Diagnosis Experience | Overall | North America | Europe | Other Regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time since diagnosis, y | ||||

| ≤1.0 | 162 (11.8) | 103 (14.2) | 47 (8.1) | 11 (16.4) |

| 1.1–5.0 | 338 (24.6) | 183 (25.2) | 133 (23.0) | 22 (32.8) |

| 5.1–10.0 | 353 (25.7) | 181 (25.0) | 152 (26.3) | 20 (29.8) |

| >10.0 | 519 (37.8) | 258 (35.6) | 246 (42.6) | 14 (20.9) |

| Time until diagnosis | ||||

| Within 6 mo | 595 (43.4) | 294 (40.5) | 266 (45.9) | 34 (53.1) |

| Within 12 mo | 183 (13.3) | 86 (11.9) | 88 (15.2) | 9 (14.1) |

| Within 2 y | 133 (9.7) | 74 (10.2) | 55 (9.5) | 3 (4.7) |

| >2 y | 461 (33.6) | 271 (37.4) | 171 (29.5) | 18 (28.1) |

| No. of health professionals seen before diagnosis | ||||

| 1–2 | 727 (52.9) | 364 (50.0) | 327 (56.8) | 34 (51.5) |

| 3–4 | 476 (34.7) | 272 (37.4) | 178 (30.9) | 25 (37.9) |

| ≥5 | 170 (12.4) | 92 (12.6) | 71 (12.3) | 7 (10.6) |

| Satisfaction with diagnosis experience | ||||

| Dissatisfied | 585 (42.4) | 301 (41.2) | 255 (44.0) | 28 (41.8) |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 310 (22.4) | 172 (23.5) | 122 (21.0) | 14 (20.9) |

| Satisfied | 486 (35.2) | 258 (35.3) | 203 (35.0) | 25 (37.3) |

| Satisfaction with information given about PCOS | ||||

| Dissatisfied or indifferent | 1165 (84.4) | 606 (83.0) | 505 (86.9) | 51 (76.1) |

| Satisfied | 216 (15.6) | 124 (17.0) | 76 (13.1) | 16 (23.9) |

| Satisfaction with information given about lifestyle management | ||||

| Dissatisfied or indifferent | 594 (43.0) | 316 (43.2) | 250 (43.1) | 27 (40.3) |

| Satisfied | 164 (11.9) | 95 (13.0) | 55 (9.5) | 14 (20.9) |

| This information was not mentioned | 623 (45.1) | 320 (43.8) | 275 (47.4) | 26 (38.8) |

| Satisfaction with information given about medical therapy | ||||

| Dissatisfied or indifferent | 740 (53.7) | 406 (55.7) | 302 (52.2) | 31 (46.3) |

| Satisfied | 235 (17.0) | 141 (19.3) | 74 (12.8) | 19 (28.4) |

| This information was not mentioned | 403 (29.2) | 182 (25.0) | 203 (35.1) | 17 (25.4) |

| Satisfaction with information about long-term complications | ||||

| Dissatisfied or indifferent | 546 (39.6) | 299 (41.0) | 225 (38.3) | 20 (29.8) |

| Satisfied | 109 (7.9) | 68 (9.3) | 30 (5.2) | 11 (16.4) |

| This information was not mentioned | 723 (52.5) | 363 (49.7) | 323 (55.9) | 36 (53.7) |

| Satisfaction with emotional support and counseling after diagnosis | ||||

| Dissatisfied or indifferent | 478 (34.7) | 275 (37.6) | 184 (31.8) | 17 (25.8) |

| Satisfied | 47 (3.4) | 30 (4.1) | 10 (1.7) | 7 (10.6) |

| This information was not mentioned | 853 (61.9) | 426 (58.3) | 384 (66.4) | 42 (63.6) |

Values are n (%).

Univariable logistic regression analysis: diagnosis experience

There were statistically significant associations between world region and some diagnosis experience variables. Women in Europe were more likely to have been diagnosed with PCOS >5 years ago than women in North America (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1 to 1.8; P < 0.01). They were also less likely to have seen ≥3 health professionals before a diagnosis was established (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6 to 0.9; P = 0.02). No statistically significant associations were noted between world region of residence and overall satisfaction with diagnosis experience, time to diagnosis, or satisfaction with information provided about PCOS at diagnosis.

Overall, seeing ≥3 health professionals was negatively associated with diagnosis satisfaction (3 to 4 health professionals: OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.5 to 0.8; P < 0.01; ≥5 health professionals: OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.6; P < 0.01). A time to diagnosis of >6 months was also negatively associated with diagnosis satisfaction (12 months: OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.7; P < 0.01; 2 years: OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.7; P < 0.01; >2 years: OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.5; P < 0.01). Satisfaction with information received about PCOS was positively associated with diagnosis satisfaction (OR, 6.9; 95% CI, 5.0 to 9.6; P < 0.01).

Multivariable logistic regression analysis: diagnosis experience

The multivariable model for satisfaction with diagnosis experience included time to diagnosis, number of health professionals seen, satisfaction with information received, time since diagnosis, current age, and world region. In this model, satisfaction with information received was positively associated with diagnosis satisfaction (OR, 7.0; 95% CI, 4.9 to 9.9; P < 0.01). Seeing ≥5 health professionals (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.8; P = 0.01) and time to diagnosis >6 months (12 months: OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.9; P = 0.01; 2 years: OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.8; P = 0.01; >2 years: OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.6; P < 0.01) were negatively associated with diagnosis satisfaction. These associations were independent of age, world region, and time since diagnosis.

Information provision at diagnosis

Less than one-quarter were satisfied with PCOS-related information given at diagnosis about lifestyle management and medical therapy (Table 2). Over one-half reported not receiving any information about long-term PCOS complications or emotional support and counseling (Table 2).

Regression analysis: information provision at diagnosis

Univariable logistic regression analyses found that women in Europe were less likely to report receiving information about medical therapy (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.5 to 0.8; P < 0.01), long-term complications (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6 to 1.0; P = 0.03), and emotional support (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.6 to 0.9; P < 0.01) than women in North America. They were also less likely to be satisfied with information provided about medical therapy (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5 to 1.0; P = 0.03) and long-term complications (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.9; P = 0.02). Women in other world regions were more likely to be satisfied with information about long-term complications (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.1 to 5.3; P = 0.03) and emotional support (OR, 3.8; 95% CI, 1.4 to 9.8; P = 0.01) than women in North America.

After adjusting for current age and time since diagnosis, women in Europe were less likely to report receiving information about medical therapy (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.5 to 0.8; P < 0.01) or emotional support and counseling (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.6 to 0.9; P = 0.01) than women in North America. Women in Europe were also less likely to be satisfied with information about long-term complications (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4 to 1.0; P = 0.03). Women in other world regions were more likely to be satisfied with emotional support (OR, 3.8; 95% CI, 1.3 to 10.7; P = 0.01) than women in North America.

Key concerns about PCOS

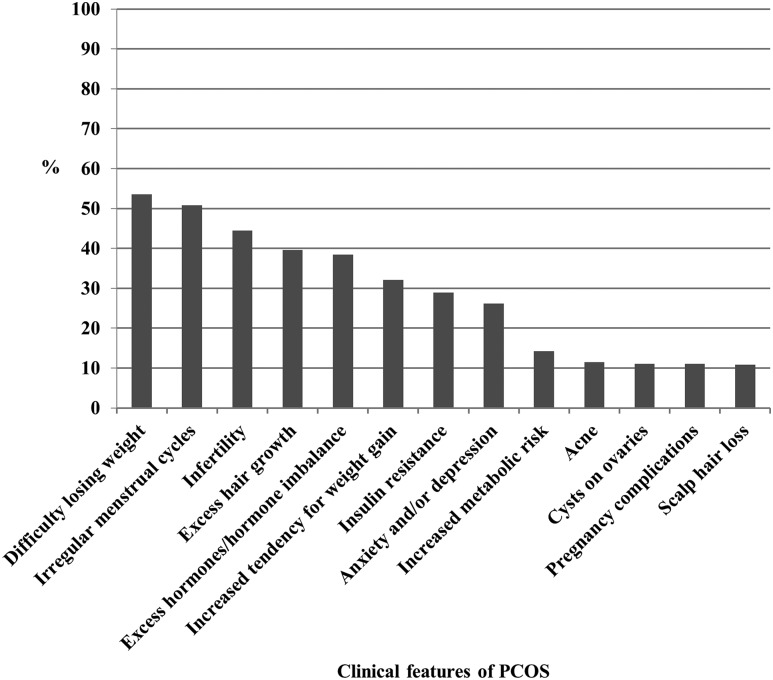

Women were asked to select “the four key clinical features of PCOS that are most important to you.” Overall, difficulty losing weight, irregular menstrual cycles, infertility, and excess hair growth were the most commonly selected features (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Key clinical features of PCOS of most importance to women (n = 1379). Increased metabolic risk included gestational diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Other answer options included body image dissatisfaction (8.3%), reduced quality of life (7.1%), premenstrual syndrome (3.4%), endometrial cancer (3.0%), sleep apnea and snoring (2.8%), fatty liver (2.8%), improvement of symptoms after weight loss (2.6%), and improvement of symptoms with exercise (1.0%).

Univariable logistic regression analysis: key concerns, age, and world region

Compared with women aged 26 to 35 years, women aged 18 to 25 years were more likely to identify irregular cycles and ovarian cysts as key concerns and less likely to identify insulin resistance (Table 3). Women aged 36 to 45 years were more likely to identify excess hair growth, increased weight gain, insulin resistance, and increased risk of metabolic complications as key concerns than women aged 26 to 35 years. They were also less likely to identify reproductive concerns (Table 3). Women aged >45 years were more likely to identify insulin resistance and increased risk of metabolic complications as key concerns and less likely to identify reproductive concerns or acne (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations Between Key Concerns About PCOS and Age or World Region

| Key Concern | Age 18–25 y | Age 36–45 y | Age >45 y | World Region: Europe | World Region: Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of women | 1375 | 1376 | |||

| Reference category | 26–35 y | North America | |||

| Difficulty losing weight | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 0.7a (0.6–0.9) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) |

| Irregular cycles | 1.5b (1.1–2.0) | 0.6a (0.5–0.8) | 0.2c (0.1–0.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 2.6a (1.5–4.5) |

| Infertility | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.6c (0.4–0.7) | 0.3c (0.2–0.4) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) |

| Excess hair growth | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.4a (1.1–1.8) | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 1.7c (1.3–2.1) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) |

| Hormone imbalance/excess male-type hormones | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | 1.0 (0.7–1.2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.6c (0.5–0.7) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) |

| Increased tendency for weight gain | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 1.3b (1.0–1.7) | 1.5 (0.9–2.3) | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) |

| Insulin resistance | 0.6b (0.4–0.9) | 1.4b (1.1–1.8) | 1.7b (1.1–2.6) | 0.4c (0.3–0.5) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) |

| Anxiety/depression | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 1.5c (1.2–2.0) | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) |

| Increased metabolic risk | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | 1.6b (1.1–2.2) | 3.6c (2.2–5.8) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) |

| Acne | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.4b (0.1–1.0) | 2.4c (1.7–3.5) | 2.2b (1.1–4.6) |

| Cysts on ovaries | 1.6b (1.0–2.5) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.9 (1.0–3.7) |

| Pregnancy complications | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.4c (0.3–0.7) | 0.3a (0.1–0.7) | 1.1 (0.7–1.5) | 1.1 (0.5–2.5) |

| Scalp hair loss | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 1.2 (0.6–2.3) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 1.3 (0.7–2.7) |

Data presented as ORs (95% CIs).

P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

Compared with women living in North America, women living in Europe were more likely to identify anxiety or depression and clinical hyperandrogenism as key concerns and less likely to identify difficulty losing weight, hormone imbalance/excess male-type hormones, and insulin resistance (Table 3).

Support needs

Participants were asked the following: “How can we best support women with PCOS?” Overall, 90.3% of women (1134/1256) selected “Provide broadly available educational materials,” 70.1% (881/1256) selected “Support and present at patient forums and workshops,” 65.0% (816/1256) selected “Maintain a consumer website,” and 59.9% (753/1256) selected “Send a regular email on PCOS.” Women in Europe were less likely to select broad education material (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.9; P = 0.01), presentations at patient forums (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.7; P < 0.01), or a consumer Web site (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.5 to 0.8; P < 0.01) than women in North America. Women aged 18 to 25 years were less likely to select a consumer Web site (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.8; P < 0.01) than women aged 26 to 35 years. Among the 14.1% (177/1256) that selected “other,” the most commonly suggested support was health professional education regarding PCOS.

Discussion

Summary of findings

In this large, international study of PCOS diagnosis experiences, women reported that receiving a diagnosis of PCOS required several months to years and consultations with multiple health professionals. In all world regions, very few women were satisfied with their diagnosis experience or with the information provided at the time of diagnosis. The leading concerns that women had about PCOS were difficulty losing weight, irregular menstrual cycles, infertility, and hirsutism. Differences were noted across age groups and world regions for some concerns. Overall, women were in favor of all suggested modes of support.

Diagnosis experience

Establishing the diagnosis of PCOS involved ≥3 health professionals and took at least a year for many women in each world region. Across different world regions, few women were satisfied with the diagnosis experience, confirming previous Australian findings (14). Our results are also consistent with qualitative research from the United Kingdom and Australia, reporting frustration at delayed PCOS diagnosis (17, 21). Here we present knowledge about contributors to poor diagnosis experience. Irrespective of world region and current age, a longer time to diagnosis and a greater number of health professionals seen were negatively associated with diagnosis satisfaction, whereas satisfaction with information provided was positively associated with diagnosis satisfaction. The significance for women’s well-being is suggested by the importance and relief that women attribute to receiving a diagnosis (16, 17) and by a negative association between time to diagnosis and psychological well-being (15).

There are many possible reasons for delayed diagnosis (22). There is no single diagnostic test, different sets of diagnostic criteria are still used, individual diagnostic criteria lack clarity, and exclusion of other etiologies is needed to establish the diagnosis of PCOS (4, 23, 24). Ovarian ultrasound examination may be a perceived barrier to patient evaluation for PCOS in the primary care community; however, an accurate diagnosis of PCOS can be made without ovarian ultrasound if hyperandrogenism and menstrual irregularity are present (4, 23). Variations in PCOS features because of ethnic origin, genetic factors, and environmental factors may also contribute to delayed diagnosis (25). PCOS is difficult to diagnose in adolescence because PCOS features can be similar to normal pubertal development (26). Adolescents and women may seek care for their presenting symptoms from different disciplines (e.g., dermatologist for hirsutism and acne, gynecologist for irregular menses, psychologist for depression), and if a woman’s care is not coordinated, the accurate diagnosis of PCOS may not be made (22). Given these challenges, comprehensive care for PCOS in a multidisciplinary setting is widely advocated, but not received by most women (12, 22, 27).

Timely diagnosis enables early interventions for acne, hirsutism, menstrual irregularity, anxiety, depression, and provision of counseling regarding future fertility. Because quality of life is linked to the clinical features of PCOS (28), early diagnosis and intervention are important. Timely diagnosis is also important for engaging women in lifestyle management early in the life course to prevent weight gain, obesity, and related metabolic complications. Prevention of weight gain is recommended in PCOS position statements and guidelines (12, 29) and is more feasible at the individual level than weight loss (30). At the systems level, weight gain prevention programs are likely to require fewer resources than weight loss programs (31). Also from a resource allocation perspective, the financial costs related to diagnosis of PCOS are only a small fraction (2%) of the total costs associated with comprehensive care for PCOS in the United States (32).

The reported delays in diagnosis suggest missed opportunities to optimize treatment, improve quality of life, and prevent weight gain. We suggest that greater community and clinician awareness about the full range of PCOS features is needed internationally to facilitate early diagnosis.

Information provision at diagnosis

Few women were satisfied with information about PCOS given at diagnosis, including on lifestyle management and medical therapy. Additionally, over one-half of the women reported not receiving information about long-term complications or emotional support/counseling. Women in Europe were particularly likely to report a lack of information provision. However, we report the desire for good-quality information regarding the full range of PCOS features and comorbidities at the time of diagnosis for women around the world. These findings are supported by previous research from the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia reporting women’s desire for more information across the full range of PCOS features (33). This desire for information at diagnosis suggests an opportune time to initiate behavior change, with enhanced knowledge of PCOS associated with increased engagement with lifestyle management (16) and better quality information about PCOS associated with better quality of life (19).

Women report gaining some or most of their information about PCOS from specialists and the Internet (18, 19, 33) and that the quality of available PCOS information varies (17, 19, 33). Professional societies in Australia, North America, and Europe produce freely available PCOS information sheets for patients; however, the findings presented here suggest these are underused by health professionals. Investigating health professional awareness of accessible resources and practices regarding PCOS consumer information could identify barriers to optimal information dissemination. Content or format of available resources may also not adequately address women’s concerns about PCOS. Clearly codeveloped information for women covering the diversity of PCOS features is needed internationally.

Key concerns about PCOS

Women identified difficulty losing weight, irregular menstrual cycles, infertility, and hirsutism as their 4 key concerns about PCOS. This finding is consistent with previous research (16, 18, 33) and with the domains of the PCOS health-related quality of life questionnaire (34). Our study is an international study in this area and reports associations between concerns, age, and world region. Concerns about weight management also once again highlight the need for health professionals to deal with lifestyle and excess weight management. Concerns with reproductive and metabolic features reflect the different clinical implications of PCOS across the life course and the importance of understanding PCOS as a long-term, multisystem condition. Clinicians need to ensure that personalized histories elicit individual concerns to guide comprehensive care.

Associations were also noted between world regions and concerns about PCOS. These observations may reflect differences in symptom experience in different cultures or ethnicities, differences in obesity prevalence, availability of local consumer education resources, or health professional knowledge of PCOS. For example, women in Europe were less likely to have concerns about difficulties losing weight and insulin resistance than women in North America, likely related to prevalent overweight, obesity, and diabetes in the United States (35, 36). Women in Europe were more likely to be concerned about clinical hyperandrogenism and anxiety or depression. This is in addition to reporting receiving less information about medical therapy and emotional support at diagnosis. Evidence-based PCOS resources for consumers and health professionals should be tailored to different geographic regions and should address the gaps previously identified.

Support needs

Women indicated that they wish to be supported in a range of ways: broadly available educational material, patient forums and workshops, and Internet-based information. Supporting women through a range of modalities is also likely to be beneficial for engagement in lifestyle management and preventive strategies. In particular, previous reports suggest that online support groups help women to build confidence in communicating with health professionals and improving self-management (37). Our findings support prior recommendations to provide women with a set of resources at the time of diagnosis that includes information on PCOS features and management, contact details of a PCOS support group, and a list of Web sites that contain good-quality, evidence-based information (17).

Limitations and strengths

The diagnosis of PCOS in our survey participants was based on self-reported medical diagnosis only, and we did not attempt to identify specific PCOS phenotypes. However, recent genetic analyses have found the same PCOS susceptibility loci in self-reported and rigorously diagnosed women with PCOS (38, 39). The questionnaire has not been validated against women’s medical records relating to diagnosis because it is designed to investigate the perceived experience and is not an audit tool. Recall bias is possible because women were asked about events that, for some participants, occurred a number of years ago. However, regression analyses relating to diagnosis experience were adjusted for time since diagnosis. Selection bias is possible, and the sample may not be representative of the general population of women with PCOS. The questionnaire was only available in English and on 2 English language Web sites. This will have limited the participation of women from non-English speaking backgrounds. Limited conclusions can be drawn regarding the other world regions group because it is a small and heterogeneous sample. The data are presented here for completeness, but we note it is largely consistent with the North American and European data and with previous research (14). Research using translated versions of the questionnaire is underway to better understand diagnosis experience in culturally and linguistically diverse groups of women. Despite these limitations, this is the largest and most comprehensive study to specifically explore the PCOS diagnosis experience and related issues. Additional strengths include its internationally recruited, community-based sample, which enabled multivariable regression analysis to somewhat take into account differences in health care system organization and cultural differences between North America and Europe. This broad investigation provides a foundation for further research to investigate the contributors to, and impact of, diagnosis experience in specific countries.

Conclusions

In the largest and only international study of PCOS diagnosis experiences, delayed diagnosis is common and associated with poor patient experience in women with PCOS worldwide. There are clear opportunities for improving awareness among women and health professionals to improve timely diagnosis. Current consumer information needs are not being met by existing educational resources, and lack of awareness, accessibility, and suitability of resources may all be contributors. Women’s concerns around PCOS vary across world regions and across the life span, highlighting the need to prioritize women’s individual concerns as part of PCOS management. Excess weight was the primary health concern, emphasizing the need to address lifestyle and weight management for women with PCOS. Overall, women are seeking information and support across a range of modalities. Taken together, these findings are concerning for both affected women and their health care providers. They also inform an initiative to develop international evidence-based guidelines, codesigned consumer and health professional resources, and international dissemination to improve diagnosis experience, education, management, and health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the women who participated in this research. The authors thank PCOS Challenge (United States) and Verity (United Kingdom) for assistance with survey dissemination. The authors also thank Sasha Ottey for advice on some of the questionnaire components.

This research received no direct funding. M.G.-H. and H.T. are National Health & Medical Research Council Research Fellows (1110701 and 1042516).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviations:

- CI

confidence interval

- OR

odds ratio

- PCOS

polycystic ovary syndrome

References

- 1. March WA, Moore VM, Willson KJ, Phillips DI, Norman RJ, Davies MJ. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(2):544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boyle JA, Cunningham J, O’Dea K, Dunbar T, Norman RJ. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a sample of Indigenous women in Darwin, Australia. Med J Aust. 2012;196(1):62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yildiz BO, Bozdag G, Yapici Z, Esinler I, Yarali H. Prevalence, phenotype and cardiometabolic risk of polycystic ovary syndrome under different diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(10):3067–3073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(1):19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Norman RJ, Dewailly D, Legro RS, Hickey TE. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet. 2007;370(9588):685–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Teede H, Deeks A, Moran L. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Med. 2010;8:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hull MG. Epidemiology of infertility and polycystic ovarian disease: endocrinological and demographic studies. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1987;1(3):235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, Norman RJ. Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4):347–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dokras A, Clifton S, Futterweit W, Wild R. Increased prevalence of anxiety symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(1):225–230.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dokras A, Clifton S, Futterweit W, Wild R. Increased risk for abnormal depression scores in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Teede HJ, Joham AE, Paul E, Moran LJ, Loxton D, Jolley D, Lombard C. Longitudinal weight gain in women identified with polycystic ovary syndrome: results of an observational study in young women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(8):1526–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Teede HJ, Misso ML, Deeks AA, Moran LJ, Stuckey BG, Wong JL, Norman RJ, Costello MF; Guideline Development Groups . Assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome: summary of an evidence-based guideline. Med J Aust. 2011;195(6):S65–S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, Hoeger KM, Murad MH, Pasquali R, Welt CK; Endocrine Society . Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(12):4565–4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gibson-Helm ME, Lucas IM, Boyle JA, Teede HJ. Women’s experiences of polycystic ovary syndrome diagnosis. Fam Pract. 2014;31(5):545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deeks AA, Gibson-Helm ME, Paul E, Teede HJ. Is having polycystic ovary syndrome a predictor of poor psychological function including anxiety and depression? Hum Reprod. 2011;26(6):1399–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Colwell K, Lujan ME, Lawson KL, Pierson RA, Chizen DR. Women’s perceptions of polycystic ovary syndrome following participation in a clinical research study: implications for knowledge, feelings, and daily health practices. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32(5):453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Avery JC, Braunack-Mayer AJ. The information needs of women diagnosed with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome--implications for treatment and health outcomes. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sills ES, Perloe M, Tucker MJ, Kaplan CR, Genton MG, Schattman GL. Diagnostic and treatment characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome: descriptive measurements of patient perception and awareness from 657 confidential self-reports. BMC Womens Health. 2001;1(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ching HL, Burke V, Stuckey BG. Quality of life and psychological morbidity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: body mass index, age and the provision of patient information are significant modifiers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;66(3):373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Misso M, Boyle J, Norman R, Teede H. Development of evidenced-based guidelines for PCOS and implications for community health. Semin Reprod Med. 2014;32(3):230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kitzinger C, Willmott J. ‘The thief of womanhood’: women’s experience of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(3):349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dokras A, Witchel SF. Are young adult women with polycystic ovary syndrome slipping through the healthcare cracks? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(5):1583–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zawadzki J, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens J, Haseltine F, Marrian G, eds. Current Issues in Endocrinology and Metabolism: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Boston, MA: Blackwell Scientific; 1992:377–384. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, Janssen OE, Legro RS, Norman RJ, Taylor AE, Witchel SF; Task Force on the Phenotype of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome of The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society . The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(2):456–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wijeyaratne CN, Dilini Udayangani SA, Balen AH. Ethnic-specific polycystic ovary syndrome: epidemiology, significance and implications. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2014;8:71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carmina E, Oberfield SE, Lobo RA. The diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(3):201.e1–201.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Institutes of Health Expert Panel Evidence-based Methodology Workshop on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Final Report. 2013. Available at: http://prevention.nih.gov/workshops/2012/pcos/docs/FinalReport.pdf. Accessed 12 September 2016.

- 28. Bazarganipour F, Taghavi SA, Montazeri A, Ahmadi F, Chaman R, Khosravi A. The impact of polycystic ovary syndrome on the health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Reprod Med. 2015;13(2):61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moran LJ, Pasquali R, Teede HJ, Hoeger KM, Norman RJ. Treatment of obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome: a position statement of the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(6):1966–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lombard C, Deeks A, Jolley D, Ball K, Teede H. A low intensity, community based lifestyle programme to prevent weight gain in women with young children: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lombard CB, Deeks AA, Teede HJ. A systematic review of interventions aimed at the prevention of weight gain in adults. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(11):2236–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Azziz R, Marin C, Hoq L, Badamgarav E, Song P. Health care-related economic burden of the polycystic ovary syndrome during the reproductive life span. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4650–4658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Humphreys L, Costarelli V. Implementation of dietary and general lifestyle advice among women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J R Soc Promot Health. 2008;128(4):190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cronin L, Guyatt G, Griffith L, Wong E, Azziz R, Futterweit W, Cook D, Dunaif A. Development of a health-related quality-of-life questionnaire (PCOSQ) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(6):1976–1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization Diabetes Country Profiles 2016. 2016. Available at: www.who.int/diabetes/country-profiles/en/#C. Accessed 28 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36. World Health Organization Prevalence of Overweight, Ages 18+, 2010–2014 (Age Standardized Estimate). 2015. Available at: http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/ncd/risk_factors/overweight/atlas.html. Accessed 28 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holbrey S, Coulson NS. A qualitative investigation of the impact of peer to peer online support for women living with polycystic ovary syndrome. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hayes MG, Urbanek M, Ehrmann DA, Armstrong LL, Lee JY, Sisk R, Karaderi T, Barber TM, McCarthy MI, Franks S, Lindgren CM, Welt CK, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Panidis D, Goodarzi MO, Azziz R, Zhang Y, James RG, Olivier M, Kissebah AH, Stener-Victorin E, Legro RS, Dunaif A, Alvero R, Barnhart HX, Baker V, Barnhart KT, Bates GW, Brzyski RG, Carr BR, Carson SA, Casson P, Cataldo NA, Christman G, Coutifaris C, Diamond MP, Eisenberg E, Gosman GG, Giudice LC, Haisenleder DJ, Huang H, Krawetz SA, Lucidi S, McGovern PG, Myers ER, Nestler JE, Ohl D, Santoro N, Schlaff WD, Snyder P, Steinkampf MP, Trussell JC, Usadi R, Yan Q, Zhang H; Reproductive Medicine Network . Genome-wide association of polycystic ovary syndrome implicates alterations in gonadotropin secretion in European ancestry populations. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Day FR, Hinds DA, Tung JY, Stolk L, Styrkarsdottir U, Saxena R, Bjonnes A, Broer L, Dunger DB, Halldorsson BV, Lawlor DA, Laval G, Mathieson I, McCardle WL, Louwers Y, Meun C, Ring S, Scott RA, Sulem P, Uitterlinden AG, Wareham NJ, Thorsteinsdottir U, Welt C, Stefansson K, Laven JSE, Ong KK, Perry JRB. Causal mechanisms and balancing selection inferred from genetic associations with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.