Abstract

Context:

Citrus fragrances have been attributed with mood-enhancing properties by aromatherapists. Leaves of this plant have been reported to exert anti-anxiety activity. Till date, no specific phytoconstituent responsible for this has been identified.

Objective:

Isolation of anxiolytic constituent of Citrus paradisi using bioactivity-guided fractionation.

Materials and Methods:

Leaf extracts of four varieties of C. paradisi in petroleum ether, chloroform, methanol and water were evaluated for anti-anxiety activity in mice using elevated plus-maze apparatus. Because of activity in methanol extract, it was used for safety evaluation/acute toxicity studies in animals. Bioactive fraction of methanol extract was subjected to column chromatography and structure of the isolated compound was elucidated by melting point, ultraviolet, infrared, nuclear mass reactor and mass spectroscopy. The isolated constituents were further evaluated for anti-anxiety activity using light/dark model and hole-board model of anxiety.

Results:

Results showed no mortality at a dose up to 2000 mg/kg body weight that indirectly reflects the safety profile of the leaf extracts. Fractionation of methanol extract led to the isolation of four flavonoids (rutin, quercetin, kaempferol and myricetin). The isolated compounds exhibited significant anxiolytic activity in different animal models.

Conclusion:

The study confirms the presence of four flavonoids responsible for anti-anxiety activity.

Keywords: Anti-anxiety, bioactivity, Citrus paradisi, flavonoids

Introduction

Stress and anxiety disorders are one of the most common mental disorders of modern world experienced by children and adolescents. In some circumstances, stress and anxiety are beneficial as they can motivate and help one to become more productive, but when it becomes excessive, it impairs day-to-day life and leads to physical or psychological illnesses. Anxiety is a central nervous system disorder with emotional state, unpleasant in nature, associated with uneasiness, discomfort and concern or fear about some defined or undefined future threat.[1,2] Studies showed that a lifetime prevalence rate of anxiety is between 13.6% and 28.8% in Western countries and in 4.5% of the world population. It has been reported that the prevalence of anxiety in adult males in India is 24.4%.[3,4] Conventional pharmacotherapy is associated with side effects such as psychomotor impairment, sexual dysfunction and dependence liability. A number of studies have been done on anti-anxiety activity of medicinal plants, but none of isolated compound has been conceived in the form of a medicine due to lack of marker compound responsible for anti-anxiety activity and nonavailability of plant materials. Hence, this study has been planned to isolate a biomarker having anti-anxiety activity.

Citrus plants belonging to Rutaceae originated in Asia and are now cultivated all over the world. Citrus fruits are rich sources of bioactive compounds which show pharmacological activities such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, antitumor and anti-inflammatory activity[5] and thus Citrus family is one of the most commercially important horticultural plants. The volatile oils obtained from genus Citrus have been recommended and used for the treatment of anxiety. A quantum of literature reflects that Citrus paradisi has been widely employed in herbal medicine as well as aromatherapy and a significant preliminary work has already been carried out by authors and other researchers on the anxiolytic effects of the plant extracts.[6,7,8,9,10,11]

In this study, the authors intended to select four varieties of plant C. paradisi available worldwide and test the anti-anxiety activity of leaf extracts. This particular species has been selected because a negligible amount of work has been done on this species as compared to other species. Leaf has been selected for isolation of compounds because it can be made available at commercial scale. Hence, the present study was designed to isolate the biomarker compound responsible for anti-anxiety activity from leaves of different varieties of C. paradisi.

Materials and Methods

Collection and identification of plant material

The leaves of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby were procured and identified from cultivated source of Punjab Agricultural University Regional Centre, Abohar (Punjab, India) in the month of March 2012 and March 2013. The plant material was dried in shade.

Solvents

Chloroform, methanol, toluene, ethyl acetate and formic acid (Merck specialties limited, Mumbai) were employed for thin-layer chromatography. All solvents were of guaranteed reagent grade except chloroform and methanol (laboratory reagents grade) which were used for column chromatography after distilling under normal atmospheric pressure. Petroleum ether (60°C–80°C), chloroform and methanol (Merck specialties limited) all of LR grade, were employed for the extraction of plant material. Diazepam (Ranbaxy) was used as standard drug.

Animals

The experimental 216 animals (Swiss albino mice (20–25 gm) of either sex were procured from the Central Animal House, Akal College of Pharmacy and Technical Education, Sangrur. The animals were given standard laboratory feed and water ad libitum, both being withdrawn 12 h before experimentation. The experiments were performed between 6.00 am and 12.00 noon h. The experiments were conducted in a semi-soundproof laboratory. The biological studies were carried out as per the guidelines of Institutional animal ethical committee. The approval from the Institutional animal ethical committee was taken before carrying out biological studies vide letter number ATRC/05/13 dated 04/05/13.

Acute toxicity study

The acute toxicity studies were performed according to the OECD guidelines.[12] The selected animals were given methanol extract orally at a dose of 400, 800, 1200, 1600 and 2000 mg/kg body weight after overnight fast. The animals were observed for 7 days for morbidity and presentation of toxicity.

Preparation of extracts and fractions

Leaves of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby were dried in shade and powdered. One kilogram of powdered leaves were subjected to successive Soxhlet extraction by solvents in increasing order of polarity, namely, petroleum ether (60°C–80°C), chloroform, methanol and water. Before each extraction, the powdered material was dried in hot air-oven below 50°C. Each extract was concentrated by distilling off the solvent using rotary evaporator and then evaporating to dryness on water-bath and the dried extracts were preserved in vacuum desiccator.

Group I (vehicle)

Syrup + carboxymethyl cellouse (2%) was used as a vehicle for preparation of suspensions of various test doses of different extracts, fractions and bioactive constituents of all varieties.

Group II (standard drug)

Diazepam (2 mg/kg orally).

Group III–VI (test solutions)

The dried plant extracts of all varieties were separately suspended in the vehicle. Different doses, namely 50, 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg of each extract (petroleum ether, chloroform, methanol and water) were administered for 5-day per oral (p. o.) once daily and the last dose was given on the 5th day, 60 min prior to start the experiment. A similar protocol was followed for standard and control groups. The isolated compounds at the dose of 2, 5 and 10 mg/kg were tested using hole-board model and light dark model.

Preparation of ethyl acetate fraction and the residual methanol fraction

The active methanol extract of leaves of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby were suspended in water, placed in three-necked round bottom flask connected with Teflon stirrer and partitioned with ethyl acetate by heating (50°C) for 30 min with continuous stirring. The procedure was repeated five times. All ethyl acetate fractions (EAFs) were pooled and solvent was recovered using Buchi 461 rotary vacuum evaporator. Thus, two fractions were obtained – EAF and the residual methanol fraction (RMF) and each fraction was evaluated for anxiolytic activity using elevated plus maze (EPM).

Fractionation of ethyl acetate fraction and anti-anxiety activity of fractions

The bioactive EAF (35 g) of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby was loaded on a column packed with silica gel (#60–120) and eluted using chloroform/chloroform-methanol/methanol as the mobile phase. A total of 189, 201, 187 and 211 fractions of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby respectively, 200 ml each were collected. These were pooled based on similar thin-layer chromatograms, to get 8 (EAF1F–EAF8F), 9 (EAF1D–EAF9D), 12 (EAF1M–EAF12M) and 10 (EAF1S–EAF10S) subfractions which were evaluated for antianxiety activity at various doses (5, 10 and 20 mg/kg PO) using EPM apparatus.

Bioactive EAF5F (6 g), EAF5D (6 g), EAF5M (6 g) and EAF5S (6 g) of foster, duncan, marsh seedles and star ruby fractions were subjected to column chromatography using silica gel (#230–400) and elution was done with petroleum ether, chloroform, and chloroform-methanol to get a total of 53, 65, 57, 63 fractions of EAF5 of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby, respectively, 200 ml each were collected. These were pooled based on similar thin-layer chromatograms, to get 3, 4, 3 and 3 subfractions which were evaluated for anti-anxiety activity at various doses (5, 10 and 20 mg/kg PO) using EPM apparatus.

Bioactive fractions EAF5F.3 (3 g), EAF5D.3 (3 g), EAF5M.3 (3 g), and EAF5S.3 (3 g) of foster, duncan, marsh seedles and star ruby were again column chromatographed over silica gel (#230–400). Elution was done with petroleum ether, chloroform and chloroform-methanol. A total of 121, 103, 153 and 93 fractions of EAF5.3 of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby, respectively, 100 ml each were collected. These were pooled based on similar thin-layer chromatograms, to get 3, 3, 2, 2 subfractions which were evaluated for anti-anxiety activity at various doses (2, 5 and 10 mg/kg PO) using EPM apparatus.

EAF5F.3.2, EAF5D.3.2, EAF5M.3.2, and EAF5S.3.2 of C. paradisi foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby were subjected to flash column chromatography and isolated the pure compound (Z1, Z2, Z3 and Z4) from all the varieties which was further evaluated for anxiolytic effect using hole-board model and light-dark model.

Characterization of isolated compounds

The melting point of Z1, Z2, Z3 and Z4 was determined and they were then subjected to spectroscopic analysis (ultraviolet [UV], infrared [IR], 1H nuclear mass reactor [NMR] and mass spectroscopy) for structural elucidation. UV spectra were obtained on Perkin Elmer Hitachi 330 (lambda 15 UV/visible spectroscopy) spectroscopy. IR spectra of test sample as neat film was obtained on an IR spectrophotometer (multispoke fourier transform IR synthesis monitoring system, Perkin Elmer, Germany). 1HNMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker spectrometer (Avane, Germany). Mass spectra was acquired in the positive ion mode on a mass spectrometer (Finnigan, USA) equipped with a pneumatically assisted atmospheric pressure chemical ionization.

Statistics

The anxiolytic activities of the fractions, diazepam and control were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple range test/Dunnett’s test. Difference was considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Acute toxicity study

Acute oral toxicity studies revealed the nontoxic nature of different extracts of different varieties of C. paradisi. There was no morbidity observed or any profound toxic reactions found at a dose of up to 2000 mg/kg body weight, which indirectly reflects the safety profile of the plant extract.

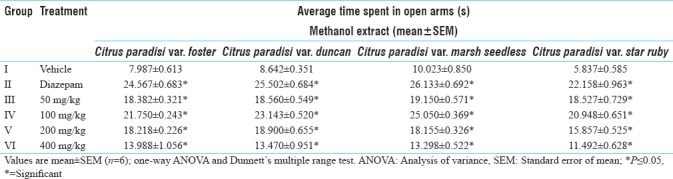

Anti-anxiety activity of various extracts

The anxiolytic activity of various leaf extracts was evaluated using elevated plus maze model. Extracts of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby were screened for anxiolytic potential using EPM. Methanol extract of all the four varieties exhibited significant anxiolytic activity in mice at the dose of 100 mg/kg PO and the activity was comparable to that of diazepam. There was marked increased in time spent in open arms of the EPM with the administration of 100 mg/kg PO methanolic leaves extract of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby [Table 1].

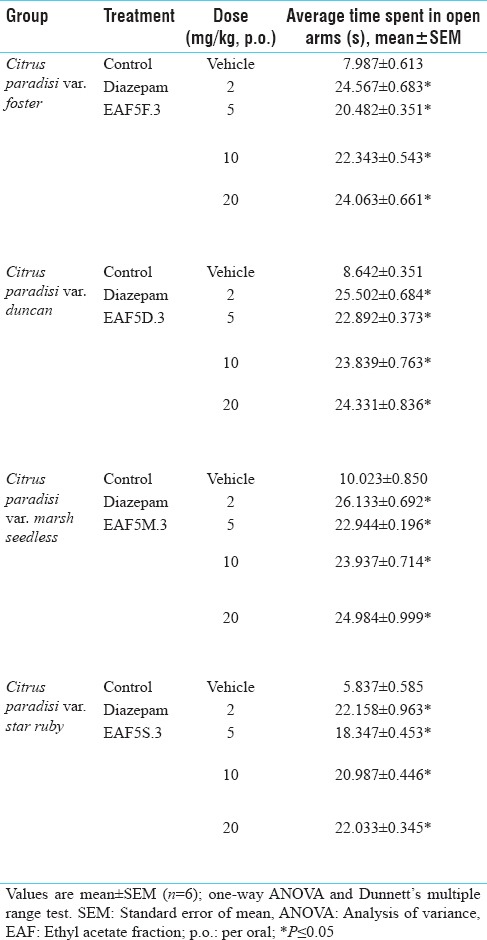

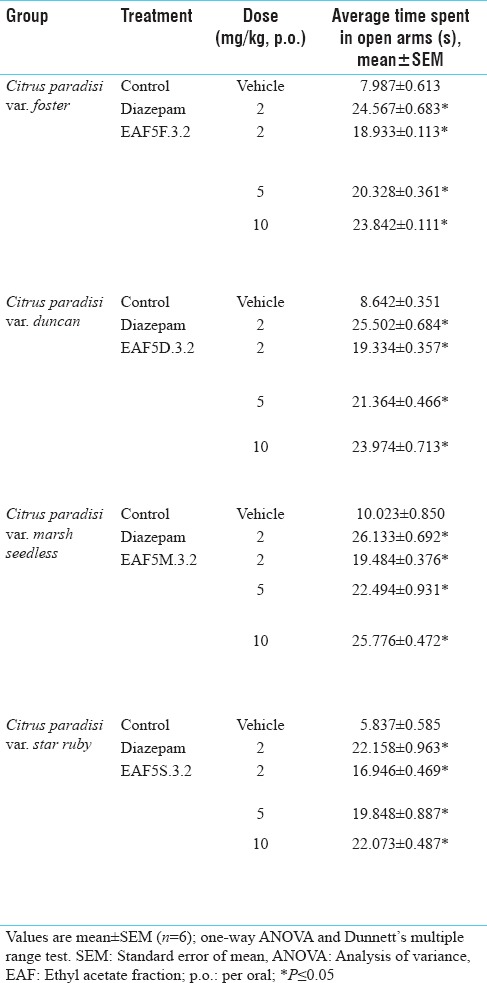

Table 4.

Anti-anxiety activity profile on elevated plus maze apparatus of various subfractions obtained after column chromatography of ethyl acetate fraction

Table 1.

Anti-anxiety activity of various extracts of leaves of Citrus paradisi using elevated plus maze apparatus

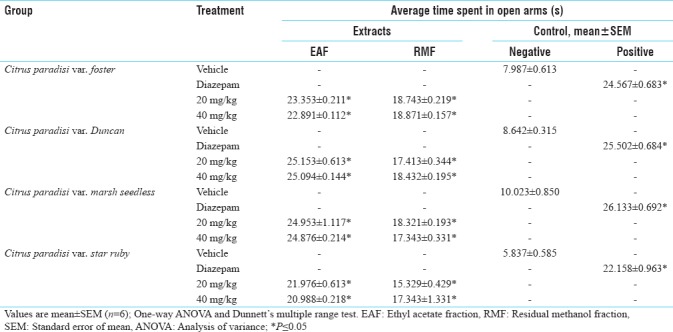

The methanolic extract of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby was selected for bioactivity-guided fractionation in view to isolate anxiolytic compound(s). The fractionation of bioactive methanol extract of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby leaves yielded two fractions, that is, EAF and RMF which were further evaluated for anti-anxiety activity in mice using EPM apparatus. EAF of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, star ruby and marsh seedless at the dose of 20 mg/kg PO using EPM showed anxiolytic activity comparable to diazepam [Table 2].

Table 2.

Anti-anxiety activity of ethyl acetate fraction and residual methanol fraction of different species of Citrus paradisi using elevated plus-maze

Column chromatography of ethyl acetate fraction

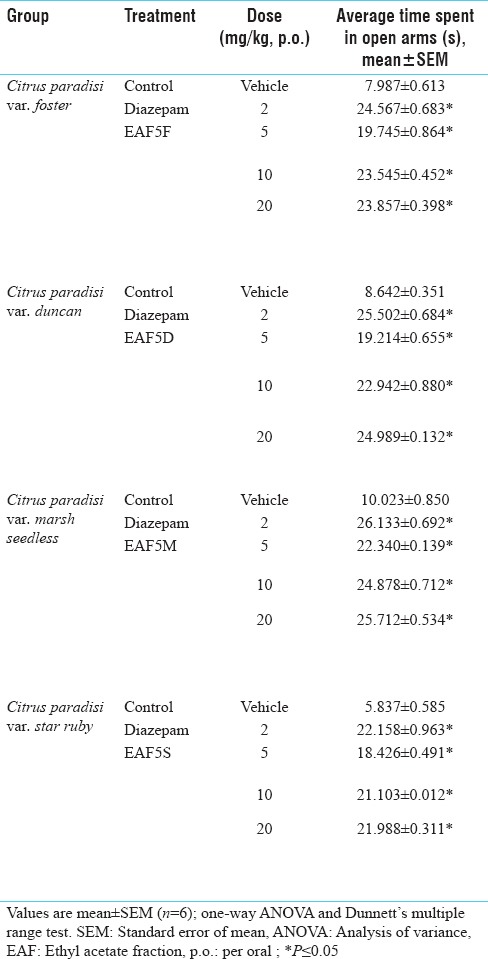

Bioactive EAF5F, EAF5D, EAF5M and EAF5S of foster, duncan, marsh seedles and star ruby at the dose of 20 mg/kg PO showed anxiolytic activity using EPM as comparable to diazepam [Table 3].

Table 3.

Antianxiety activity profile on elevated plus-maze apparatus of various subfractions obtained after column chromatography of ethyl acetate fraction

Bioactive fraction EAF5F.3, EAF5D.3, EAF5M.3 and EAF5S.3 of C. paradisi foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby at the dose of 20 mg/kg PO showed anxiolytic activity using EPM as comparable to diazepam [Table 4].

Bioactive fractions EAF5F.3.2, EAF5D.3.2, EAF5M.3.2, and EAF5S.3.2 of C. paradisi foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby at the dose of 10 mg/kg PO at the dose of 10 mg/kg PO showed anxiolytic activity using EPM as comparable to diazepam [Table 5].

Table 5.

Anti-anxiety activity profile on elevated plus maze apparatus of various subfractions obtained through column chromatography of ethyl acetate fraction

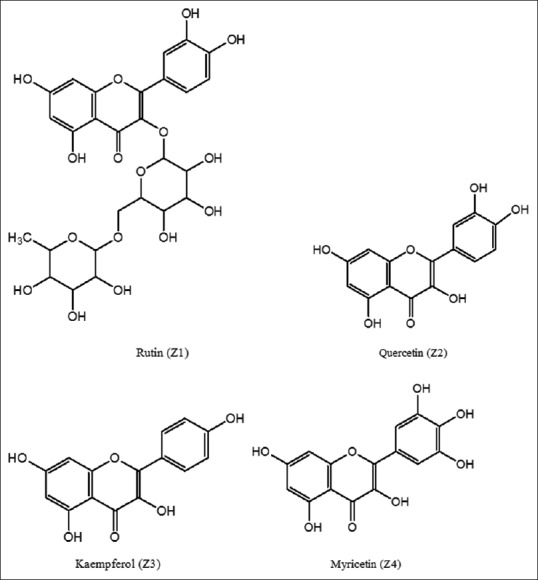

EAF5F.3.2, EAF5D.3.2, EAF5M.3.2, and EAF5S.3.2 of C. paradisi foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby were subjected to flash column chromatography. This resulted in separation of 4 fractions which were then analyzed by TLC using chloroform: methanol (7:3). All four fractions were having different Rf values (F1, F2, F3, F4 of C. paradisi foster; D1, D2, D3, D4 of C. paradisi Duncan; M1, M2, M3, M4 of C. paradisi marsh seedless; and S1, S2, S3, S4 of C. paradisi star ruby). It was found out that F1, D1, M1, and S1 were having same Rf values, therefore, they were pooled together. Similarly F2, D2, M2, S2; F3, D3, M3, S3; and F4, D4, M4, S4 were pooled together. All fractions were run again in five random mobile phases and gave single spot, so they were deemed to be pure compounds and named as Z1, Z2, Z3 and Z4.

Characterization of isolated compounds

Z1: Color: Pale yellow powder; Melting Point: 241°C–242°C; Yield: 252 mg; UVmax (MeOH): 359 nm; IR: 3483 (O-H stretch), 2931 cm−1 (C-H stretch), 1669 cm−1 (C = O), 1504 cm−1 (C = C aromatic stretch), 1348 cm−1, 1141 cm−1 (C-O-C); 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO solvent): δ 12.5 (C5-OH), 10.9 (C7-OH), 6.4 (d, 1H, J = 1.4, C8-H), 6.2 (m, 1H, J = 1.4, C6-H), 5.3 (s, 1H, J = 7.0, C1”-H), 4.3 (brs, 1H, C1’’’-H), 3.0–3.7 (m, sugar protons), 1.0 (s, 3H, J = 6.0, C6’’’-H); MS: [M + H] +=611, [M + H] +-Rhamnose=465, [M + H] +-Rhamnose-Glucose=303. This corresponds to C27H30O16. The compound in fraction F1, D1, M1, S1 is identified as rutin and named as Z1.

Z2: Colour: Yellow powder; Melting Point: 314°C–315°C; Yield: 330 mg; UVmax (MeOH): 375 nm; IR: 3349 cm−1 (O-H stretch), 2899 cm−1 (C-H stretch), 1673 cm−1 (C = O), 1489 cm−1 (C = C stretch); 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO solvent): δ 6.85 (s, 1H, OH), δ 6.79 (s, 1H, OH), δ 6.54 (s, 1H, OH); MS: [M + H] +=302, [M + H-H2O] +=285, [M + H-CO] +=275, [M + H-H2O-CO] +=257.[M + H-H2O-2CO] +=229. This corresponds to C15H10O7. The compound in fraction F2, D2, M2, S2 is identified as quercetin and named as Z2.

Z3: Colour: Yellow powder; Melting Point: 272°C–274°C; Yield: 267 mg; UVmax (MeOH): 260 nm; IR: 3467 cm−1 (O-H stretch), 2835 cm−1 (C-H stretch), 1679 cm−1 (C = O), 1573 and 1412 cm−1 (Aromatic ring); 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO solvent): 10.76 (s, 1H, 7-OH), 7.78 (s, 2H, H-2’), 7.45 (d, 1H, H-8), 7.24 (d, 2H, H-3’ and H-5’), 5.35 (s, 1H, H-6); MS: [M + H] +=286. This corresponds to C15H10O6. The compound in fraction F3, D3, M3, S3 is identified as Kaempferol and named as Z3.

Z4: Colour: Yellow crystals; Melting Point: 353°C–355°C; Yield: 264 mg; UVmax (MeOH): 375 nm; IR: 3384 cm−1 (O-H stretch), 1678 and 1631 cm−1 (C-O stretch), 1593 cm−1 (C-C stretch), 1536 cm−1 (Aromatic ring), 1359 and 1165 cm−1 (C-O-C stretch); 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO solvent): 6.3 (s, 2H, H-2′, 6′), 5.8 (s, 2H, H-8), 4.98 (m, 5H, H); MS: M+=318, [M + H-H2O] =301, [M + H-H2O-CO] +=273. This corresponds to C15H10O8. The compound in fraction F4, D4, M4, S4 is identified as Myricetin and named as Z4 [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Structure of the isolated compounds

Confirmation of anti-anxiety activity of isolated compounds

The anti-anxiety activity of isolated compounds was further confirmed using hole-board model and light dark test.

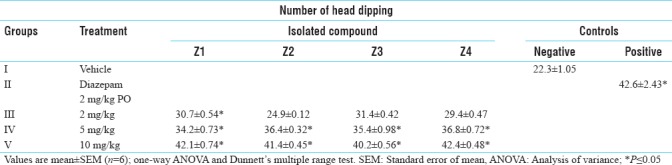

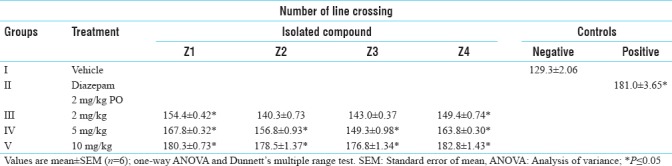

Hole-board model

The number of line crossing and head dipping was increased significantly in case of diazepam-treated animals as compared to the control animals. All the isolated compounds Z1, Z2, Z3 and Z4 showed an increase in the number of line crossing and head dipping significantly and the result were similar as that of standard drug [Tables 6 and 7].

Table 6.

Anti-anxiety activity of isolated compounds in hole-board model (head dipping)

Table 7.

Anti-anxiety activity of isolated compounds in hole-board model (line crossing)

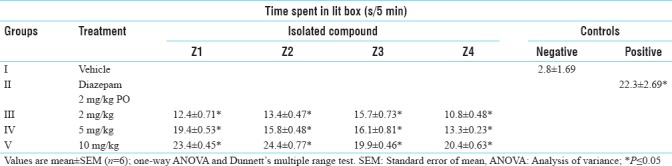

Light-dark model

The time spent in lit box was increased significantly in case of 2, 5 and 10 mg/kg dose of isolated compounds Z1, Z2, Z3 and Z4 and the result was comparable to the standard drug, diazepam [Table 8].

Table 8.

Anti-anxiety activity of isolated compounds in light-dark model

Discussion

Anxiety disorders are serious medical illnesses that have affected one-eighth of the total population worldwide irrespective of gender, age, religion, nationality and profession.[13] Mental disorder has attracted the attention of researchers toward various pharmacotherapeutic approaches.[14] Benzodiazepines (BZDS) are used as a first line of treatment. Today, at least 20 million people worldwide are prescribed these “minor tranquilizers.” Regular use of BZDs causes deterioration of cognitive functioning, addiction, physical dependence and tolerance.[15] Due to adverse effects associated with the synthetic drugs, researchers have been exploring natural resources based on traditional systems of medicine to come across safer and effective drugs.[16]

Selection of plants, that is, C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby have a long history of use in alternative and traditional system of medicine and similar species in Ayurvedic pharmaco-therapeutics for the treatment of mental disorders. Leaves of different varieties of C. paradisi have never been evaluated for their anti-anxiety potential using standard protocols. Hence, it was considered worthwhile to investigate anti-anxiety potential of the C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby and to isolate the components responsible for this activity.

Various extracts of leaves of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby were obtained by successive exhaustive extraction of the plant material using solvents in increasing order of polarity, namely, petroleum ether, chloroform, methanol and water. The rationale for using these solvents was to separate plant constituents on the basis of polarity.

The EPM is a novel, effective, cheap and simple method, requires no preliminary training of experimental animals and does not cause much discomfort to them while handling. The fear due to height (acrophobia) induces anxiety, measured by time spent by mice in open arms of the EPM. Anxiolytic compounds, by decreasing anxiety, increasing the open-arm exploration time; anxiogenic compounds have the opposite effect.[17] Mice constitute an invaluable tool for modeling human anxiety in its various forms as these display remarkable similarities on anatomical, physiological, biochemical, molecular and behavioral levels.[18] In the study, standard values, for mean time spent in open arms of EPM, of the control (vehicle) and the standard (diazepam) groups of mice were initially generated using 12 mice in each group – a number of two times the number (6 mice) used for the test group. These values were then used as reference in all the subsequent anti-anxiety evaluations of the test samples. It is also observed that even at the dose of 2000 mg/kg, PO, no apparent toxic/adverse effect was observed with any of the leaves extracts in the study. Methanol extract of C. paradisi exhibited significant anxiolytic activity in mice at the dose of 100 mg/kg PO and the activity was comparable to that of diazepam. However, the activity decreased at higher dose which might be due to mild sedation. The methanol extract of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby was selected for bioactivity-guided fractionation with a view to isolate anxiolytic compound(s).

In an attempt to separate the contents of bioactive methanol extract of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby exhibiting significant anxiolytic activity, it was fractionated by shaking with ethyl acetate. Among the two fractions, namely, EAF and the RMF, only EAF of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby at a dose of 20 mg/kg PO exhibited significant anxiolytic activity using EPM model.

The bioactive EAF of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby was subjected to column chromatography which yielded different fractions. EAF5F.3.2, EAF5D.3.2, EAF5M.3.2 and EAF5S.3.2 of C. paradisi foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby were subjected to flash column chromatography using chloroform: methanol (80:20) yielded four pure isolates Z1, Z2, Z3 and Z4 named rutin, quercetin, kaempferol, and myricetin, respectively. The anti-anxiety activity of isolated compounds Z1, Z2, Z3 and Z4 was further confirmed using hole-board model and light-dark test.

Flavonoids and terpenoids act as antianxiety agents by modulating the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors similar to that of benzodiazepines, thereby increasing the frequency of chloride channel opening and resulting in the neuronal hyperpolarization.[19,20,21] In addition to the receptor modulating activity, flavonoids also act as antioxidant agents because of their hydrogen donating ability, which ultimately result in neuroprotective role.[22,23] As the phytochemical, chromatographic and spectroscopic investigation has shown the presence of various flavonoids in different varieties of C. paradisi, therefore, they are potential candidates for the treatment of anxiety disorders, as justified by the results of various animal models of anxiety.

Conclusion

In light of the above findings, it is concluded that rutin, quercetin, kaempferol and myricetin are responsible for the antianxiety activity of leaves of C. paradisi var. foster, duncan, marsh seedless and star ruby. However, further studies are needed to determine the exact mechanism by which these phytochemical constituents isolated from C. paradisi interact with GABA or other receptors to exert the antianxiety activity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, Golden RN, Gorman JM, Krishnan KR, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill:Scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:175–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being:A World health organization study in primary care. JAMA. 1998;280:147–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raakhee AS, Aparna N. A study on the prevalence of anxiety disorders among higher secondary students. GESJ Educ Sci Psychol. 2011;1:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahoo S, Khess CR. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among young male adults in India:A dimensional and categorical diagnoses-based study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:901–4. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181fe75dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mabberley DJ. Citrus (Rutaceae): A review of recent advances in etymology, systematics and medical applications. Blumea. 2004;49:481–98. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta V, Bansal P, Kumar P, Shri R. Anxiolytic and antidepressant activities of different extracts from Citrus paradisi var. foster. J Pharm Res. 2009;2:1864–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta V, Bansal P, Kumar P, Shri R. Anxiolytic and antidepressant activities of different extracts from Citrus paradisi var. duncan. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2010;3:98–100. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta V, Bansal P, Kumar P, Kaur G. Pharmacopoeial standards and pharmacognostical studies of leaves of Citrus paradisi var. foster. Res J Pharmacognosy Phytochem. 2010;2:140–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta V, Bansal P, Niazi J, Kaur G. Anti-anxiety activity of Citrus paradisi var. star ruby extracts. Int J Pharm Tech Res. 2011;2:1655–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta V, Ghaiye P, Bansal P, Shri R. Pharmacopoeial standards and pharmacognostical studies of leaves of Citrus paradisi var. duncan. J Pharm Res. 2011;4:1084–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta V, Bansal P, Kohli K, Ghaiye P. Development of economic herbal based drug substitute from Citrus paradisi (Grape fruit) for existing anti-anxiety drug modules. Nat Prod Chem Res. 2014:S1–001. [doi:10.4172/2329-6836.S1-001] [Google Scholar]

- 12.France: OECD Publishing; 2006. OECD. OECD Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals. Health effects: Test No. 425: Acute Oral Toxicity: Up and Down Procedure. Sec. 4. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 25] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bethesda, Maryland: National Institute of Mental Health, Office of Communications and Public Liaison; 2011. [[Last accessed on 2016 Jun 25]]. NIMH. Statistics. Available from:http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/index.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riaza Bermudo-Soriano C, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Vaquero-Lorenzo C, Baca-Garcia E. New perspectives in glutamate and anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2012;100:752–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnani P, Conforti A, Zanolin E, Marzotto M, Bellavite P. Dose-effect study of Gelsemium sempervirens in high dilutions on anxiety-related responses in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210:533–45. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1855-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhawan BN. Centrally acting agents from Indian plants. In: Koslow SH, Murthy RS, Coelho GV, editors. Decade of the Brain. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1995. pp. 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogel HG. 2 ed. Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2002. Drug Discovery and Evaluation Pharmacological Assays. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohoff C. Anxiety in mice and men:A comparison. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2009;116:679–87. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0215-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanrahan JR, Chebib M, Johnston GA. Flavonoid modulation of GABA(A) receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:234–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston GA. GABA(A) receptor channel pharmacology. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:1867–85. doi: 10.2174/1381612054021024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edewor-Kuponiyi TI. Plant-derived compounds with potential sedative and anxiolytic activities. Int J Basic Appl Sci. 2013;2:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandhar HK, Kumar B, Prasher S, Tiwari P, Salhan M, Sharma P. A review of phytochemistry and pharmacology of flavonoids. Int Pharm Sci. 2011;1:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sen S, Chakraborty R. Revival, modernization and integration of Indian traditional herbal medicine in clinical practice:Importance, challenges and future. J Tradit Complement Med. 2017;7:234–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]