Abstract

Circadian clocks control daily rhythms in physiology, metabolism, and behavior in most organisms. Proteome-wide analysis of protein oscillations is still lacking in Drosophila. In this study, the total protein and phosphorylated protein in Drosophila heads in a 24-hour daily time-course were assayed by using the iTRAQ (Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation) method, and 10 and 7 oscillating proteins as well as 19 and 22 oscillating phosphoproteins in the w1118 wild type and ClkJrk mutant strains were separately identified. Lastly, we performed a mini screen to investigate the functions of some oscillating proteins in circadian locomotion rhythms. This study provides the first proteomic profiling of diurnally oscillating proteins in fly heads, thereby providing a basis for further mechanistic studies of these proteins in circadian rhythm.

Keywords: Circadian rhythm, clock, proteomics, Drosophila

Introduction

Daily rhythms are a universal phenomenon in many species. These rhythms are regulated by the circadian clock, a molecular machinery that involves a conserved transcriptional-translational feedback loop. In Drosophila, two transcriptional activators, CLOCK (CLK) and CYCLE (CYC), form a heterodimeric complex and activate rhythmic transcription of clock-controlled genes [1]. PERIOD (PER) and TIMELESS (TIM) are the main repressors, which first accumulate in the cytoplasm and then enter the nucleus to repress CLK/CYC activity [2]. Post-translational regulation, such as phosphorylation events, is also critical in circadian regulation. A series of kinases and phosphatases regulate the stability of pacemaker proteins and their nuclear localization. Nuclear localization or stability of PER and TIM is regulated by phosphorylation events mediated by DOUBLETIME (DBT), casein kinase II (CK2), or glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) [3–11]. Phosphorylation of PER by Nemo (NMO) controls its stability [12–13]. Another type of post-translational modification, glycosylation, regulates PER nuclear accumulation [14–15].

Many circadian related genes in Drosophila have been identified at the genome wide level using microarrays or RNA sequencing [16–19]. Furthermore, clock-controlled genes from different groups of clock neurons have been also identified by RNA-seq [20–22]. As CLK is a critical circadian trans-activator, targets of CLK have been characterized by chromatin immunoprecipitation [23]. Although these studies provide insights into circadian transcriptional regulation, much less is known about oscillations at the proteome level. Recently, proteomics and phospho-proteomics have been used to identify circadian changes in proteins in mouse and rat [24–25, 40–46]; however, a proteomic profile of oscillating proteins in the nervous system in Drosophila is still lacking.

In order to identify oscillating proteins that may play a role in regulation of circadian rhythms, we performed quantitative proteomics analysis of fly heads using a previously described approach named iTRAQ (Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation) [26]. Compared to other quantitative mass spectrometry (MS) methods, such as isotope-coded affinity tags (ICAT) and metabolic labeling or stable isotope labeling of amino acids in culture (SILAC), the design of this method enables more confident peptide identifications and processing of eight samples at the same time, thereby greatly reducing technical error [26].

The Drosophila CLK protein is at the center of multiple regulatory loops involved in circadian rhythm [27–31]. In this study, we identified total proteins as well as phosphorylated proteins that oscillate across the 24-hour day in both wild-type (w1118) and ClkJrk mutant fly heads by using iTRAQ, and further identified their differentially expressed proteins and phosphoproteins. Lastly, we analyzed the behavior of flies with mutations in genes encoding several of the oscillating proteins identified in the screen and revealed potential roles for α-catenin in circadian rhythms.

Results

Ontological features of proteins expressed in the fly head

ClkJrk is a clock gene mutant that abolishes fly circadian rhythms [28]. Here we first verified that our ClkJrk mutant line exhibited arrhythmic locomotor behavior and lack of full length CLK protein. Results showed that the locomotor rhythm of the ClkJrk mutant in light: dark (LD) and constant darkness (DD) was disrupted compared to a w1118 control (Figure S1A), and the abundance of CLOCK protein was decreased in the ClkJrk mutant in an immunoblot experiment (Figure S1B). Thus, the ClkJrk and w1118 control lines were used for this study.

In order to identify diurnally oscillating proteins, total proteins from whole head in both wild-type (w1118) and ClkJrk mutant flies were sampled at Zeitgeiber time (ZT) ZT2 (2 hours after lights on), ZT8, ZT14, ZT20 and analyzed using the iTRAQ-MS method (Figure S1C), in which 3,270 proteins in total were identified, of which 3,154 (96.5%) were detected in all three replicates.

Protein expression profiles in w1118 and ClkJrk

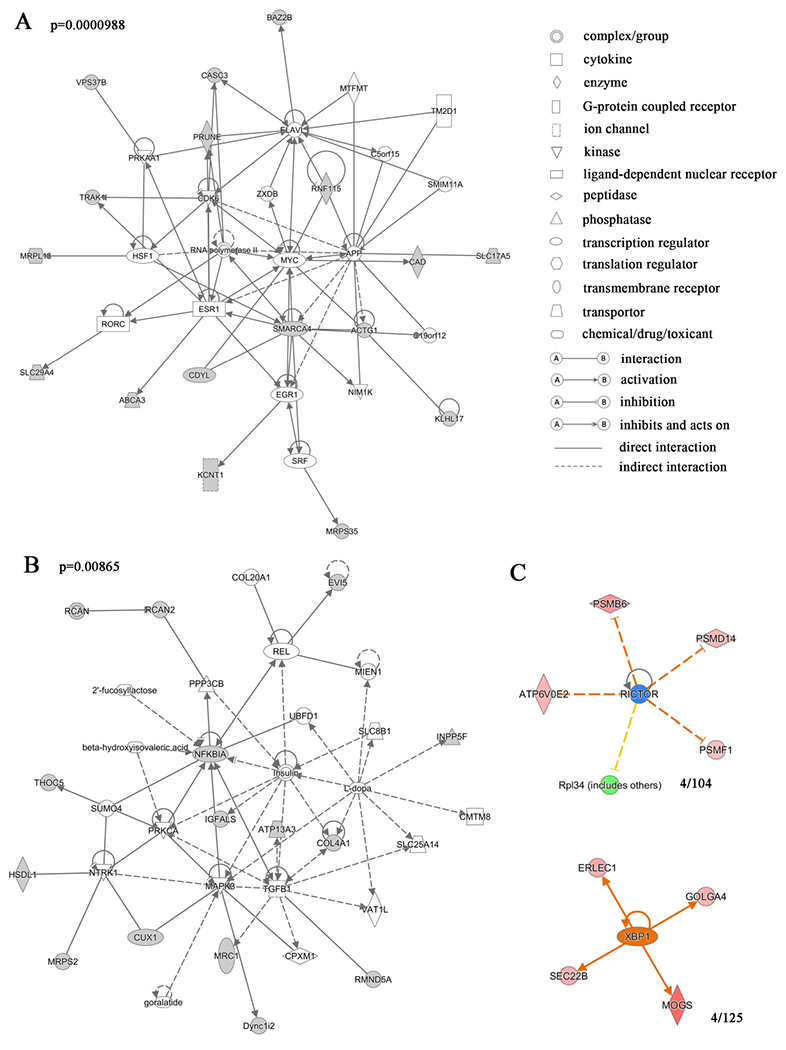

In this study, the total protein profiles at ZT2, ZT8, ZT14, and ZT20 between w1118 and ClkJrk lines were compared using Scaffold Q+ Quantitation Module. With coefficient greater than 0.6 (fold change>1.5 as log21.5=0.6) and p < 0.05, there were 45 differentially expressed proteins (Table 1). Pathway clustering revealed that the differentially expressed proteins were most often involved in cancer and organismal injury (Table S1). These proteins function in uridine-5’-phosphate biosynthesis and L-glutamine biosynthesis, PI3K/AKT signaling, RNA polymerase II processes, transcription activator BRG1 and MYC-centered gene expression and transcriptional regulation network, and mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 (MAPK3) and insulin-like receptor-centered network of tissue development and metabolism (Figure 1A, B).

Table 1.

Differential expressed total proteins in w1118 and ClkIrk

| Accession Number | Molecular Weight | Protein Grouping Ambiguity | P-Value | Symbol | Feature type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBpp0086494 | 25 kDa | TRUE | < 0.0001 | Dmel\igl-PA | myosin light chain binding |

| FBpp0086695 (+2) | 96 kDa | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG8485-PA | ATP binding; protein serine/threonine kinase activity; SAP kinase activity | |

| FBpp0081636 (+1) | 4 kDa | 0.00055 | Dmel\MtnA-PA | metal ion binding | |

| FBpp0087193 (+2) | 322 kDa | TRUE | 0.0011 | Dmel\tou-PA | chromatin binding; DNA binding; zinc ion binding |

| FBpp0070136 | 25 kDa | 0.0024 | Dmel\Sec22-PA | SNAP receptor activity phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 4-phosphatase activity | |

| FBpp0076085 (+2) | 29 kDa | 0.0029 | Dmel\CG6707-PA | ||

| FBpp0083464 | 59 kDa | TRUE | 0.0033 | Dmel\mod(mdg4)-PF | phosphatidate phosphatase activity |

| FBpp0070743 (+1) | 62 kDa | 0.022 | Dmel\CG15784-PA | unknown | |

| FBpp0289513 | 33 kDa | TRUE | 0.027 | Dmel\Eb1-PF | microtubule binding |

| FBpp0291330 | 73 kDa | TRUE | 0.029 | Dmel\drongo-PF | GTPase activator activity |

| FBpp0085710 (+1) | 98 kDa | TRUE | 0.03 | Dmel\CG10062-PA | unknown |

| FBpp0076837 (+2) | 70 kDa | 0.031 | Dmel\Msr-110-PA | unknown | |

| FBpp0088293 (+3) | 114 kDa | TRUE | < 0.0001 | Dmel\4E-T-PB | unknown |

| FBpp0078708 (+1) | 15 kDa | < 0.0001 | Dmel\TotM-PA | unknown | |

| FBpp0070468 | 76 kDa | < 0.0001 | Dmel\w-PA | ATP binding; ATPase activity, coupled to transmembrane movement of substances; eye pigment precursor transporter activity; transmembrane signaling receptor activity | |

| FBpp0078534 (+2) | 46 kDa | 0.00012 | Dmel\CG9775-PA | ubiquitin-protein transferase activity; zinc ion binding | |

| FBpp0081445 | 40 kDa | 0.00025 | Dmel\CG11982-PA | ubiquitin-protein transferase activity; zinc ion binding | |

| FBpp0079168 (+1) | 13 kDa | 0.00028 | Dmel\RpL36A-PA | structural constituent of ribosome | |

| FBpp0081192 | 21 kDa | TRUE | 0.00028 | Dmel\Ccp84Ae-PA | structural constituent of chitin-based cuticle; structural constituent of chitin-based larval cuticle |

| FBpp0291858 | 51 kDa | 0.00044 | Dmel\Cpr47Ef-PC | structural constituent of chitin-based cuticle; structural constituent of chitin-based larval cuticle | |

| FBpp0071423 (+3) | 58 kDa | 0.00054 | Dmel\ras-PC | IMP dehydrogenase activity | |

| FBpp0073330 | 10 kDa | 0.00078 | Dmel\ssp7-PA | unknown | |

| FBpp0112233 | 59 kDa | TRUE | 0.00079 | Dmel\Ugt86Dd-PB | glucuronosyltransferase activity |

| FBpp0292247 | 157 kDa | TRUE | 0.00084 | Dmel\Ptp99A-PF | protein tyrosine phosphatase activity; transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase activity |

| FBpp0080757 (+3) | 77 kDa | 0.0023 | Dmel\CG17544-PA | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase activity; acyl-CoA oxidase activity; flavin adenine dinucleotide binding; pristanoyl-CoA oxidase activity | |

| FBpp0290840 | 38 kDa | TRUE | 0.0025 | Dmel\mRpS35-PA | structural constituent of ribosome |

| FBpp0072560 | 41 kDa | 0.0052 | Dmel\CG9149-PA | acetyl-CoA C-acyltransferase activity | |

| FBpp0081187 | 19 kDa | 0.013 | Dmel\Ccp84Ag-PA | structural constituent of chitin-based cuticle; structural constituent of chitin-based larval cuticle | |

| FBpp0082709 (+1) | 31 kDa | 0.017 | Dmel\sra-PA | protein binding kinesin-associated | |

| FBpp0297341 (+1) | 135 kDa | TRUE | 0.017 | Dmel\milt-PD | mitochondrial adaptor activity |

| FBpp0081725 | 26 kDa | TRUE | 0.019 | Dmel\Rrp46-PA | 3′-5′-exoribonuclease activity |

| FBpp0071590 (+3) | 13 kDa | TRUE | 0.022 | Dmel\HmgZ-PB | DNA binding |

| FBpp0073789 (+3) | 66 kDa | 0.032 | Dmel\pdgy-PA | long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase activity | |

| FBpp0078071 (+1) | 31 kDa | 0.036 | Dmel\CG9391-PA | inositol monophosphate 1-phosphatase activity | |

| FBpp0077099 | 30 kDa | 0.05 | Dmel\mRpS2-PA | structural constituent of ribosome | |

| FBpp0297622 | 28 kDa | TRUE | 0.051 | Dmel\CG8757-PB | oxidoreductase activity, acting on CH-OH group of donors |

| FBpp0072365 | 93 kDa | TRUE | < 0.0001 | Dmel\Lsp1γ-PA | nutrient reservoir activity ATP binding; ATPase activity, coupled to transmembrane movement of substances; transporter activity |

| FBpp0290160 | 190 kDa | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG1801-PC | ||

| FBpp0086581 (+1) | 58 kDa | TRUE | 0.00017 | Dmel\Cyp6a17-PA | electron carrier activity; heme binding; iron ion binding; oxidoreductase activity, acting on paired donors, with incorporation or reduction of molecular oxygen |

| FBpp0070533 (+1) | 26 kDa | 0.00024 | Dmel\CG3603-PA | oxidoreductase activity, acting on CH-OH group of donors | |

| FBpp0079279 (+3) | 79 kDa | TRUE | 0.00074 | Dmel\Akap200-PA | protein kinase A binding |

| FBpp0081851 | 58 kDa | TRUE | 0.0014 | Dmel\Ugt35b-PA | transferase activity, transferring hexosyl groups; UDP-glycosyltransferase activity |

| FBpp0078854 (+1) | 70 kDa | TRUE | 0.0016 | Dmel\mtm-PA | protein tyrosine phosphatase activity; protein tyrosine/ serine/ threonine phosphatase activity |

| FBpp0071095 (+1) | 43 kDa | TRUE | 0.0017 | Dmel\CG10932-PA | acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase activity |

| FBpp0080957 (+1) | 16 kDa | 0.028 | Dmel\CG9338-PA | unknown |

Figure 1.

(A, B) Gene network analysis of the proteins differentially expressed in w1118 and ClkJrk flies revealed that these proteins are involved in the RNA polymerase II complex, transcription activator BRG1 and MYC-centered gene expression and transcriptional regulation network, and MAPK3 and insulin-like receptor-centered network of tissue development and metabolism. Variation coefficient > 0.6 and p value <0.05. The proteins shaded were presented in the differentially expressed proteins. The p value of the gene network was 0.0000988 for figure 1A and 0.00865 for figure 1B. The statistical information for the other gene networks identified is in Table S1. (C) Transcription factors that may regulate expression of differentially expressed proteins. 4/104 and 4/125 proteins were found to have common upstream factors XBP1 and RICTOR, respectively. The red to pink colors indicate up-regulation, and greens indicate downregulation. Darker colors indicate more extreme up or down regulation. Yellow indicates predicted activation, and blue predicted inhibition with darker hue indicative of more confidence in the prediction. Gray line indicates that effects are not predicted. Different types of the molecules are indicated by shapes as shown.

In order to get a global view of the regulatory mechanisms involved in the differential protein expression in the ClkJrk line, we searched for the possible upstream regulatory factors that might regulate these differentially expressed proteins (Figure 1C). Results showed that three upstream regulatory factors were possibly involved in regulation of expression of these proteins at ZT8 and ZT20. At ZT8, four of one hundred and four downstream targets of X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) were enriched in the ClkJrk -specific differentially expressed proteins. At ZT20, four of one hundred and twenty-five downstream targets of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NFE2L2) and rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (RICTOR) were enriched in ClkJrk -specific differentially expressed proteins. These results suggest that the activity of these upstream regulatory factors may be altered more in ClkJrk than in w1118 flies.

Oscillating proteins in w1118 and ClkJrk mutants

To comprehensively look for the oscillating total proteins in w1118 and ClkJrk mutant flies, we applied both a JTK cycle for assay of the expression data [32] and assay of differential proteins at different time points. Results from JTK assay showed 10 and 7 oscillating proteins in w1118 and ClkJrk mutants, respectively, by applying criteria of ADJ (P<0.05). AMP (amplitude) and LAG (phase) were indicated for these detected oscillating proteins (Table 2). Interestingly, a transcription factor UPF1 was identified as an oscillating protein in both w1118 and ClkJrk (Table 2). Moreover, some proteins identified as oscillating proteins in both genotypes were ribosome structural components.

Table 2.

Oscillating total proteins in w1118 and ClkIrk

| Accession Number | Gene Name | Biological Process | ADJ.P | PER | LAG | AMP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w1118 | FBpp0073433 (+1) | Upf1 | ATP binding; DNA binding; helicase activity; zinc ion binding | 0.005595 | 24 | 12 | 0.307591 |

| FBpp0081815 (+1) | CG4757 | carboxylic ester hydrolase activity | 0.005595 | 24 | 9 | 0.143189 | |

| FBpp0075445 | CG17839 | Unknown | 0.005595 | 24 | 12 | 0.077782 | |

| FBpp0078854 (+1) | mtm | phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphatase activity; phorsphortase activity | 0.005595 | 24 | 12 | 0.070711 | |

| FBpp0080049 | CG9302 | protein disulfide isomerase activity | 0.007424 | 24 | 12 | 0.106066 | |

| FBpp0086965 | mRpL18 | structural constituent of ribosome | 0.01368 | 24 | 12 | 0.091924 | |

| FBpp0079790 | hgo | homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase activity | 0.018788 | 24 | 15 | 0.116673 | |

| FBpp0289679 (+1) | CG31205 | serine-type endopeptidase activity | 0.018788 | 24 | 12 | 0.067175 | |

| FBpp0078424 (+2) | Vps37B | ESCRT assembly domain | 0.023896 | 24 | 12 | 0.144957 | |

| FBpp0084730 | CG11841 | serine-type endopeptidase activity | 0.039848 | 24 | 12 | 0.152028 | |

| ClkJrk | FBpp0079614 | CG5188 | Proteolysis | 0.003766 | 24 | 9 | 0.258094 |

| FBpp0073433 (+1) | Upf1 | ATP binding; DNA binding; helicase activity; zinc ion binding | 0.010552 | 24 | 9 | 0.212132 | |

| FBpp0083560 (+3) | CASK | ATP binding; protein kinase activity | 0.018788 | 24 | 6 | 0.13435 | |

| FBpp0075743 (+1) | Pbgs | porphobilinogen synthase activity; zinc ion binding | 0.018788 | 24 | 9 | 0.120208 | |

| FBpp0072925 | Drsl4 | antifungus | 0.031872 | 24 | 3 | 0.26163 | |

| FBpp0072056 | thoc5 | mRNA binding | 0.031872 | 24 | 6 | 0.219203 | |

| FBpp0077099 | mRpS2 | structural constituent of ribosome | 0.031872 | 24 | 6 | 0.127279 | |

Phosphorylated proteins with altered expression in the ClkJrk mutant

As phosphoproteins play important roles in circadian regulation, we concentrated phosphorylated peptides using the TiO2 method [33] and analyzed the phosphorylated peptides profiles of both w1118 and ClkJrk at ZT2, ZT8, ZT14, and ZT20. Totally, we identified 5961 phosphorylated peptides, of which 1345 were found in all three replicates. A full list of identified phosphorylated peptides was shown in Table S2.

In this study, 1,275 phosphorylated proteins were detected, of which 649 (51%) were found in all three replicates at ZT2, ZT8, ZT14 and ZT20 in both w1118 and ClkJrk mutant flies. Analysis in phosphorylated protein profiles at these four time points between the two genotypes, by using One-way ANOVA analysis with coefficient greater than 0.6 and p < 0.05, we found that there were totally 55 differentially phosphorylated proteins (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differential phosphorylated proteins in w1118 and ClkJrk

| Accession Number | MW (kDa) | Protein Grouping Ambiguity | P-Value | Symbol | Feature type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBpp0292500 | 6 | 0.002 | Dmel\CG31808-PC | ||

| FBpp0080074 | 11 | 0.005 | Dmel\CG9928-PA | ||

| FBpp0077716 | 12 | 0.024 | Dmel\RpLP1-PA | structural constituent of ribosome | |

| FBpp0088837 | 12 | 0.001 | Dmel\SC35-PA | mRNA binding; nucleotide binding | |

| FBpp0071590 | 13 | TRUE | 0.00096 | Dmel\HmgZ-PB | DNA binding |

| FBpp0071308 | 23 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG32700-PA | ||

| FBpp0088688 | 24 | 0.00025 | Dmel\Mlc2-PA | calcium ion binding; microfilament motor activity | |

| FBpp0086860 | 25 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG4716-PA | methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase [NAD(P)+] activity | |

| FBpp0082724 | 28 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\SF2-PA | mRNA binding; nucleotide binding | |

| FBpp0082987 | 30 | TRUE | < 0.0001 | Dmel\14-3-3ε-PA | protein domain specific binding; protein kinase C inhibitor activity |

| FBpp0071307 | 33 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\l(1)G0320-PA | signal sequence binding | |

| FBpp0074056 | 35 | 0.001 | Dmel\Rbp2-PB | mRNA binding; nucleic acid binding; nucleotide binding; translation initiation factor activity | |

| FBpp0074530 | 35 | 0.002 | Dmel\CG12237-PA | phosphatase activity; pyrophosphatase activity | |

| FBpp0077186 | 37 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\Reph-PA | ||

| FBpp0076552 | 40 | 0.057 | Dmel\lark-PA | mRNA binding; nucleic acid binding; nucleotide binding; RNA binding; zinc ion binding | |

| FBpp0078321 | 40 | 0.0016 | Dmel\CG2082-PC | ||

| FBpp0073344 | 41 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\Gs2-PB | glutamate-ammonia ligase activity | |

| FBpp0083266 | 41 | 0.042 | Dmel\ninaE-PA | G-protein coupled photoreceptor activity; G-protein coupled receptor activity | |

| FBpp0084457 | 41 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG6330-PA | uridine phosphorylase activity | |

| FBpp0070787 | 42 | TRUE | < 0.0001 | Dmel\Act5C-PA | structural constituent of cytoskeleton |

| FBpp0081544 | 42 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\RnpS1-PA | Rab GTPase binding; transporter activity | |

| FBpp0076326 | 45 | TRUE | < 0.0001 | Dmel\Arr2-PA | opsin binding |

| FBpp0078393 | 49 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\kra-PA | protein binding; ribosome binding; translation initiation factor binding | |

| FBpp0077367 | 51 | 0.019 | Dmel\NTPase-PA | guanosine-diphosphatase activity; nucleoside-diphosphatase activity; nucleoside-triphosphatase activity | |

| FBpp0080277 | 53 | TRUE | 0.031 | Dmel\vig-PD | mRNA binding |

| FBpp0087631 | 56 | 0.0001 | Dmel\ced-6-PB | PTB/PI domain; Pleckstrin-homology domain (PH domain)/Phosphotyrosine-binding domain (PTB) | |

| FBpp0077872 | 57 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG4825-PA | CDP-diacylglycerol-serine O-phosphatidyltransferase activity | |

| FBpp0073173 | 58 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\HDAC1-PA | histone deacetylase activity; transcription corepressor activity | |

| FBpp0079471 | 58 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\Srp54-PA | mRNA binding; nucleotide binding | |

| FBpp0078561 | 60 | 0.00083 | Dmel\lost-PA | RNA binding | |

| FBpp0112089 | 62 | 0.024 | Dmel\Cpr73D-PB | structural constituent of chitin-based cuticle; structural constituent of chitin-based larval cuticle | |

| FBpp0081881 | 64 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG6723-PA | sodium:iodide symporter activity | |

| FBpp0088565 | 64 | 0.003 | Dmel\eIF-3p66-PB | translation initiation factor activity | |

| FBpp0086941 | 66 | 0.0003 | Dmel\Amph-PA | phospholipid binding | |

| FBpp0079999 | 68 | TRUE | < 0.0001 | Dmel\Vha68-2-PA | ATP binding; proton-transporting ATPase activity, rotational mechanism; contributes_to proton-transporting ATPase activity, rotational mechanism |

| FBpp0070336 | 75 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\eIF2B-ε-PA | nucleotidyltransferase activity; translation initiation factor activity | |

| FBpp0307811 | 76 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG44195-PA | ATP binding; calcium-dependent protein kinase C | |

| FBpp0086196 | 80 | 0.023 | Dmel\inaC-PA | activity; diacylglycerol binding; protein kinase C activity; protein serine/threonine kinase activity; zinc ion binding | |

| FBpp0074557 | 88 | 0.028 | Dmel\CG12531-PA | amino acid transmembrane transporter activity; basic amino acid transmembrane transporter activity | |

| FBpp0087933 | 89 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\nito-PA | mRNA binding; nucleic acid binding; nucleotide binding G-protein coupled receptor activity; receptor | |

| FBpp0084323 | 100 | 0.045 | Dmel\boss-PA | binding; sevenless binding; transmembrane signaling receptor activity | |

| FBpp0075617 | 108 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\SRm160-PA | ||

| FBpp0088653 | 109 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG1677-PA | metal ion binding | |

| FBpp0084655 | 113 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\Moca-cyp-PA | peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity | |

| FBpp0290385 | 122 | 0.00098 | Dmel\CG5549-PB | glycine:sodium symporter activity; neurotransmitter transporter activity; neurotransmitter:sodium symporter activity | |

| FBpp0289455 | 134 | 0.001 | Dmel\CG42450-PA | signal transducer activity | |

| FBpp0078930 | 135 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\Liprin-α-PA | protein binding | |

| FBpp0080638 | 152 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\ncm-PA | RNA binding ATP binding; platelet-derived growth factor-activated receptor activity; protein tyrosine kinase activity; transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase activity; vascular endothelial growth factor-activated receptor activity | |

| FBpp0079244 | 170 | 0.001 | Dmel\Pvr-PA | ||

| FBpp0079064 | 174 | TRUE | < 0.0001 | Dmel\ninaC-PB | ATP binding; ATPase activity, coupled; calmodulin binding; motor activity; protein kinase activity; protein serine/threonine kinase activity; receptor signaling protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

| FBpp0074228 | 266 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\β-Spec-PA | actin binding; actin filament binding; calmodulin binding; cytoskeletal protein binding; structural constituent of cytoskeleton | |

| FBpp0304412 | 311 | 0.00011 | Dmel\E(bx)-PH | DNA binding; contributes_to nucleosome-dependent ATPase activity; zinc ion binding | |

| FBpp0311334 | 367 | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG45186-PAB | actin binding | |

| FBpp0111616 | 380 | TRUE | < 0.0001 | Dmel\CG34417-PD | actin binding; structural constituent of cytoskeleton |

| FBpp0306407 | 405 | 0.011 | Dmel\btsz-PI | Rab GTPase binding; transporter activity |

Phosphorylated oscillating peptides in w1118 and ClkJrk mutants

To comprehensively look for the oscillating phosphorylated proteins in w1118 and ClkJrk mutant flies, we applied the JTK cycle for both assay of the expression data and assay of differentially phosphorylated proteins at different time points. Results from the JTK assay showed that there were 19 and 22 phosphorylated oscillating proteins in w1118 and ClkJrk, respectively, by applying criteria of ADJ (P<0.05) (Table 4). Besides, for the oscillating phosphorylated proteins identified in this study, there were no significant changes in correspondence with total protein abundance at different time points, and JTK cycle analysis for these proteins also did not show significant oscillating. These data suggested that the oscillating phosphorylated protein only reflected changes in phosphorylation.

Table 4.

Oscillating phosphorylated proteins

| Accession Number | Gene Name | Biological Process | ADJ.P | PER | LAG | AMP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w1118 | FBpp0099563 (+3) | Dop2R | Dopamine receptor | 0.001775 | 24 | 0 | 0.208597 |

| FBpp0099855 (+2) | Dek | chromatin binding | 0.003766 | 24 | 0 | 0.144957 | |

| FBpp0071590 (+3) | HMG protein Z | sequence-specific DNA binding proteins | 0.005595 | 24 | 0 | 0.254558 | |

| FBpp0075278 (+4) | brahma | chromatin-remodeling | 0.005595 | 24 | 0 | 0.144957 | |

| FBpp0071448 | Actin 57B | structural constituent of cytoskeleton | 0.005595 | 24 | 3 | 0.083085 | |

| FBpp0076320 (+1) | Paramyosin | Myosin tail | 0.007424 | 24 | 3 | 0.152028 | |

| FBpp0078393 (+6) | krasavietz | translational regulator | 0.010552 | 24 | 0 | 0.19799 | |

| FBpp0088690 (+2) | Hrs | endocytosis | 0.010552 | 24 | 3 | 0.10253 | |

| FBpp0288578 | CG42235 | Sodium/solute symporter | 0.01368 | 24 | 15 | 0.137886 | |

| FBpp0072338 (+2) | Eps-15 | calcium ion binding | 0.023896 | 24 | 0 | 0.084853 | |

| FBpp0078674 (+1) | Reticulon-like1 | endoplasmic reticulum organization; endoplasmic reticulum tubular network membrane organization | 0.031872 | 24 | 3 | 0.123744 | |

| FBpp0087678 (+3) | DNA fragmentation factor-related protein 2 | regulation of apoptotic process; negative regulation of neuron death | 0.031872 | 24 | 0 | 0.070711 | |

| FBpp0086860 (+1) | CG4716 | methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase [NAD(P)+] activity | 0.039848 | 24 | 0 | 0.275772 | |

| FBpp0089041 | Proteasome α7 subunit | Proteasome alpha-type subunit | 0.039848 | 24 | 0 | 0.171473 | |

| FBpp0081539 | CG8149 | SAP domain superfamily | 0.039848 | 24 | 21 | 0.164402 | |

| FBpp0085043 (+1) | jdp | protein folding | 0.039848 | 24 | 0 | 0.146725 | |

| FBpp0082687-DECOY (+1) | Myosin heavy chain-like | Class XVIII myosin | 0.039848 | 24 | 12 | 0.137886 | |

| FBpp0082692 | moira | DNA binding; protein binding | 0.039848 | 24 | 18 | 0.109602 | |

| FBpp0080825 (+1) | Topoisomerase 2 | DNA topoisomerase | 0.039848 | 24 | 0 | 0.106066 | |

| ClkJrk | FBpp0086013 (+1) | eIF3c | Proteasome component | 0.000519 | 24 | 9 | 0.127279 |

| FBpp0070618 (+5) | norpA | phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C activity | 0.000758 | 24 | 9 | 0.279307 | |

| FBpp0084566 (+1) | Myosin alkali light chain 1 | microfilament motor activity; calcium ion binding | 0.003766 | 24 | 6 | 0.127279 | |

| FBpp0292500 | CG31808 | unknown | 0.007424 | 24 | 9 | 0.309359 | |

| FBpp0309308 (+4) | radish | GTPase activator activity | 0.007424 | 24 | 15 | 0.176777 | |

| FBpp0079420 (+1) | numb | Notch binding | 0.010552 | 24 | 15 | 0.183848 | |

| FBpp0085139 (+4) | chaoptin | unknown | 0.010552 | 24 | 15 | 0.084853 | |

| FBpp0086252 | Ribosomal protein LP2 | structural constituent of ribosome | 0.01368 | 24 | 9 | 0.38007 | |

| FBpp0074415 (+1) | CG32544 | unknown | 0.018788 | 24 | 15 | 0.160867 | |

| FBpp0082514 (+6) | Heat shock protein cognate 4 | chaperone binding; unfolded protein binding | 0.018788 | 24 | 12 | 0.084853 | |

| FBpp0078775 | blue cheese | metal ion binding | 0.018788 | 24 | 12 | 0.042426 | |

| FBpp0081881 | CG6723 | transmembrane transporter activity | 0.023896 | 24 | 6 | 0.387141 | |

| FBpp0073309 (+2) | CG1737 | unknown | 0.031872 | 24 | 15 | 0.139654 | |

| FBpp0075023 (+5) | Nc73EF | thiamine pyrophosphate binding; oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (succinyl-transferring) activity | 0.031872 | 24 | 9 | 0.083085 | |

| FBpp0074825 | Catalase | antioxidant activity; heme binding; catalase activity | 0.031872 | 24 | 12 | 0.06364 | |

| FBpp0112048 | ensconsin | structural molecule activity; microtubule binding | 0.039848 | 24 | 6 | 2.506694 | |

| FBpp0081470 (+4) | pumilio | mRNA 3′-UTR binding; translation repressor activity, nucleic acid binding; RNA binding | 0.039848 | 24 | 9 | 0.228042 | |

| FBpp0099901 | Synapsin | unknown | 0.039848 | 24 | 18 | 0.16617 | |

| FBpp0087502 (+4) | 14-3-3ζ | protein kinase C inhibitor activity | 0.039848 | 24 | 12 | 0.127279 | |

| FBpp0071757 (+4) | Liprin-γ | protein binding | 0.039848 | 24 | 21 | 0.120208 | |

| FBpp0293740 (+2) | rhea | integrin binding; actin binding; protein binding; structural constituent of cytoskeleton; actin filament binding | 0.039848 | 24 | 15 | 0.106066 | |

| FBpp0076320 (+1) | Paramyosin | motor activity | 0.039848 | 24 | 12 | 0.095459 | |

Functional analysis of proteins in oscillatory expression patterns

Importantly, many identified proteins in this study are known to be involved in circadian regulation such as SLMB, Brm, and ATX2 [34–36]. Here we focused on some proteins that have not been linked to circadian rhythms, so 15 proteins that showed oscillations or differences in expression between w1118 and ClkJrk were selected for further functional analysis (Table 5).

Table 5.

Behavior results for circadian locomotion screen.

| Gene | Genotype | Period (h) | Rhythmicity | N number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD2/+ | 24.3±0.21 | 82.50% | 32 | |

| alpha-cat | TD2/BL38987 | 25.1±0.20 | 87.50% | 32 |

| alpha-cat | TD2/BL38197 | 25.1±0.12 | 86.70% | 30 |

| Tps1 | TD2/BL57488 | 24.4±0.13 | 30.40% | 23 |

| Dsor1 | TD2/VDRC107276 | 25.0±0.17 | 93.80% | 16 |

| Dsor1 | TD2/VDRC40026 | 24.9±0.15 | 100% | 8 |

| CG13117 | TD2/BL51678 | 25.2±0.22 | 100% | 15 |

| PD2/+ | 24.5±0.22 | 93.80% | 16 | |

| alpha-cat | PD2/BL38987 | 25.6±0.12 | 88.00% | 25 |

| alpha-cat | PD2/BL38197 | 25.5±0.08 | 100% | 26 |

| Tps1 | PD2/BL57488 | 24.8±0.05 | 93.80% | 16 |

| Dsor1 | PD2/VDRC107276 | 24.7±0.15 | 100% | 8 |

| Dsor1 | PD2/VDRC40026 | 25.0±0.13 | 100% | 8 |

| HmgZ | TD2/BL26219 | 23.8±0.13 | 59.10% | 22 |

| SLO2 | TD2/BL32034 | 24.4±0.20 | 87.50% | 24 |

| CG5641 | TD2/BL56895 | 24.7±0.32 | 69.20% | 13 |

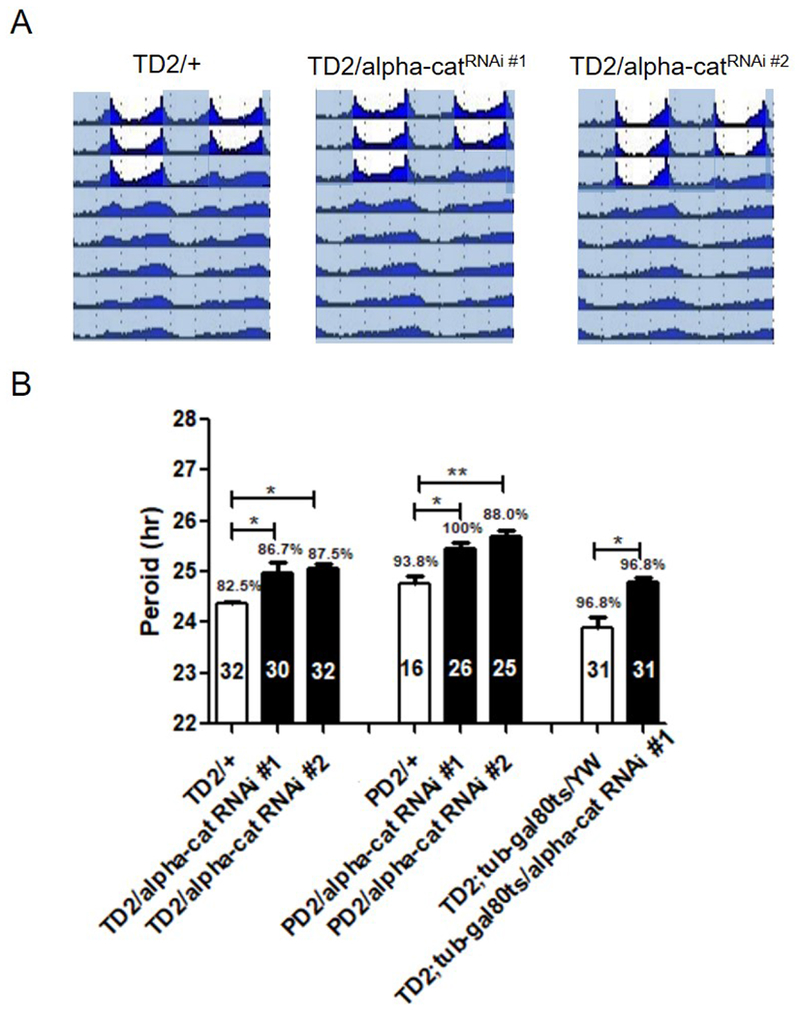

For most of these proteins, no mutants were available, so we used tim-GAL4 to express double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) targeting these genes in all circadian neurons, in which Dicer2 was introduced to enhance the RNAi efficiency [36, 37]. For most of the dsRNAs tested, there were no obvious defects in circadian behavior (Table 5), indicating that these genes are not involved in locomotor circadian behavior. However, expression of dsRNA designed to target the mRNA that encodes α-catenin (α-Cat) lengthened the period by about 1 hour (Figure 2). To determine which neuron requires α-Cat expression, we used pdf-GAL4 to restrict the dsRNA expression to pacemaker neurons. This caused a phenotype similar to that of flies in which dsRNA expression was driven by tim-GAL4, indicating that α-Cat is required in pacemaker neurons for circadian behavior. To exclude the potential developmental defects of depletion of α-Cat, we restricted dsRNA expression only in adulthood, by using a temperature sensitive gal80 (gal80ts). A significant lengthened circadian period was still observed while knocking down α-Cat only during the adult stages (Figure 2). Together, these data indicate that α-Cat may play a role in regulation of circadian rhythms.

Figure 2.

α-Cat is potentially required for circadian locomotor rhythm. (A) Locomotion behavior under light dark (LD) cycles and constant darkness (DD). Representative double plotted actograms showing last 3 days of LD and 5 days of DD for controls, flies that express dsRNA targeting α-Cat (TD2/+; α-Cat RNAi#2/+flies). White indicates the light phase, and gray indicates the dark phase. (B) Effects of α-Cat downregulation in circadian neurons on period length of circadian locomotion behavior. Bar graph showing period length (y axis), percentage of rhythmic flies, and number of flies tested (in the bars). Error bars indicate SEM. Each genotype was compared to appropriate genotype control or driver control. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; n.s., not significant at the 0.05 level, tested using Student’s t test.

Materials and methods

Fly rears and strains

Fly lines used in this study were w1118 (Bloomington No. 5905) and ClkJrk (a gift from Michael Rosbash, Brandeis University). Flies were raised on standard Drosophila food. ZT (Zeitgeber time) was the time of collection relative to the light:dark cycle used in the experiments. ZT0 was defined as the time point of lights on, while ZT12 was the time point of lights off. The incubator conditions were: 25 °C, 60% humidity, 350 Lux light intensity, and a 24-hour photoperiod (12L:12D; ZT0 was 6:30, ZT12 was 18:30). Newly eclosed male and female virgin flies were synchronized and collected at different time points after aging for 2 days.

Fly strains used to verify the proteins in this screen including tim-Gal4, UAS-Dicer (TD2-Gal4), pdf-Gal4, UAS-Dicer (PD2-Gal4), BL38987, BL38197, BL57488, BL51678, BL38987, BL38197, BL57488, BL26219, BL32034, BL56895, BL58353, BL6832, BL57695, BL20805, BL31957, BL51406, and BL53868 were from the Bloomington stock center. VDRC107276, VDRC40026, VDRC107276, and VDRC40026 were from Vienna Drosophila Resource center.

Experiment Design and Statistical Rationale

In order to determine the protein oscillation at different time points, we collected head tissue samples at ZT2, ZT8, ZT14, ZT20 of w1118 and ClkJrk flies. Eight samples were employed for each experiment, and the data from w1118 were used as controls. Three biological replicates were carried out for each sample. Eighty fly heads were collected for each sample. Statistical analysis was performed using Spss11.5.

T-test or one-way ANOVA was used for all variation analysis in which p<0.05 was regarded as significant, and p<0.01 was regarded as very significant. After aging for 2 days, flies from ZT2, ZT8, ZT14, and ZT20 were anesthetized with CO2 and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Fly heads were cut off and lysed in STD buffer (2% SDS, 5 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM DTT, pH 6.8) with phosphatase inhibitor complex from Sangon Biotech (No. C500019) and protease inhibitor from Roche (No. 04693132001). After grinding, boiling, sonicating (80 w, 10-s 15 times with 15-s intervals), and centrifuging (13000 rpm 4 °C for 25 min), the protein solution in the central layer was collected and stored at −80 °C. Concentration of the protein solution was determined by BCA assay. 200 μg protein was digested using a modified FASP method as described previously [38]. In short, the protein solution was loaded onto an ultrafltration device (30 K MWCO, 500 μL, Sartorius), washed with 50 mM NH4HCO3 (ABC), reduced with 200 mM DCEP at 56 °C, and alkylated with 200 mM MMTS in the dark. The protein was digested with trypsin at 37 °C overnight (enzyme: protein ratio, 1: 50). The digested peptides were desalted and lyophilized for iTRAQ labeling with iTRAQ 8-plex reagent (Sigma 4381663 and 4381664) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Protein samples from w1118 flies were labeled with isobaric tags 113, 114, 115, 116 (ZT2, ZT8, ZT14 and ZT20), protein samples from ClkJrk were labeled with 117, 118, 119, 121 (ZT2, ZT8, ZT14 and ZT20). Three biological replicates were performed.

For phosphopeptide enrichment, the labeled peptides were dissolved in 100 μL loading buffer (1 mL lactic acid, 2 mL 80% ACN, 0.4% TFA), and phosphopeptides were enriched using the Titansphere Phos-TiO kit (GL Sciences, No. 5010-21514) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Labeled peptides were fractionated with strong cation exchange on an Acquity HPLC system (Waters) using SCX column (Protein-Pak Hi Res SP, 7 μm, 4.6×100 mm, non-porous; Waters). Fifteen fractions were collected and analyzed using a Q-Exactive high-resolution mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled with Acquity nano-HPLC system (Waters). Peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 0.2 μl/min with a 95-min gradient on a 75 μm×100 mm column filled with 3 μm C18 stationary phase (AQ C18, Phenomenex). The mass resolutions of the mass analyzer were set at 70,000 and 17,500 for full MS and MS/MS analyses, respectively, and the scan range was 300 to 1800 m/z. The 10 most intensive precursor ions were selected for MS/MS fragmentation with NCE at 30. Phosphopeptides were analyzed with a 120-min nano-LC gradient without SCX fractionation.

Data analysis and quality control

Raw data were processed with Mascot Distiller 2.5 for peak picking and searched using Mascot 2.5.1 software (Matrix Science) against flybase protein database r5.4 (30362 entries) with the following parameters: enzyme, trypsin, 2 missed cleavages. Methylthio (C) was set as fixed modification and phospho (STY) was set as variable modification. Mass tolerance for precursor ions was 20ppm. Mass tolerance for fragment ions was 0.02Da. Known contaminants was excluded. The search results were imported into Scaffold (version 4.4.5, Proteome Software Inc.) for further analysis. The peptides were filtered with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 1.0%. We required that at least two peptides be identified for each protein and a Mascot ion score ≥ 20. Quantification of the peptides was performed using Scaffold Q+ (version Scaffold_4.4.5, Proteome Software Inc.). Normalization was performed iteratively (across samples and spectra) on intensities, as described in Statistical Analysis of Relative Labeled Mass Spectrometry Data from Complex Samples Using ANOVA. Medians were used for averaging. Spectra data were log-transformed, pruned of those matched to multiple proteins, and weighted by an adaptive intensity weighting algorithm. We identified 96.5% (3154/3270) of proteins in all three replicates. To ensure accuracy of quantitative results, coefficient of variation (CV) < 20% were applied.

For analysis of the proteins differentially expressed in w1118 and ClkJrk, we used Scaffold Q+ Quantitation Module. We used the Log2 Fold Change method to measure differential abundance of proteins between two genotypes (detailed method described scaffold Q+ USERS GUIDE P58-59 from http://www.proteomesoftware.com/). We chose the proteins as significantly changed between w1118 and ClkJrk with a mean value fold change greater than 1.5 (coefficient >log21.5 = 0.6) for further analysis.

Bioinformatics analysis

The original data was uploaded to website http://www.iprox.org/page/DSV021.html;?url=1506131721592IQ9Y with password XOCS. The Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed at http://www.geneontology.org and http://www.pantherdb.org/. The pathway analysis was done using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis according to a detailed protocol on website: https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis/ and http://celldesigner.org/.

Behavior experiments and analysis

Adult male flies (2-5 days old) were used for testing circadian locomotor activity. Flies were entrained for 3 days to LD cycles at 25 °C and then released into DD for at least 6 days. Locomotor activity was recorded with Drosophila Activity Monitors from Trikenetics in Percival I36-LL incubators. Data analysis was performed with the FAAS-X software provided by the F. Rouyer lab [34]. For actograms, a signal-processing toolbox implemented in MATLAB (MathWorks) was used [39].

Discussion

There are advantages and disadvantages of the proteomic approach applied in this study. The advantage of this study was that capacity to show a number of novel oscillating proteins and phosphorylated proteins, and the locomotion behavior analysis was used to confirm any roles of these in circadian rhythm. But one of the potential caveats for this proteomic analysis is that proteomic methods may miss some specific proteins due to low abundance. This may explain why we were not able to get differential signal for PER or TIM in this study. In this study, a significant number of differentially expressed proteins was acquired. However, another limitation of this study was that any spatial resolution of these differentially expressed proteins was not determined because we used head samples, in which the potential change in phase in one brain area was not captured. Further studies with more spatial resolutions are needed in the future.

The phosphorylated proteins are very important for maintaining function of protein activity. Although studies of core clock proteins have demonstrated the importance of phosphorylated proteins in circadian and sleep regulation [1, 2], a systematic study of protein phosphorylation in circadian regulation has not been performed. This study provides a proteome-wide view of phosphorylated proteins that are potentially important in circadian regulation. Most of the oscillatory phosphorylated proteins in w1118 are not disrupted by mutation of a critical clock gene, indicating that these time-dependent expressions of phosphorylated proteins may be independent of clock.

Importantly, some oscillatory phosphorylated proteins found in ClkJrk flies do not show the same pattern in w1118 flies. These phosphoproteins in ClkJrk flies might be involved in daily rhythmic loss. The oscillatory phosphorylated proteins identified also do not overlap with the total oscillatory proteins (both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated proteins), thereby implying that some proteins have an oscillation only in a phosphorylated form. Thus, further investigation into the role of post-translational regulation in the circadian rhythm may lead to new insights into how the daily rhythms are regulated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Dr. Jeffrey Price (University of Missouri at Kansas City) for editing the syntax of this manuscript. The work was supported by the grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers 31730076 and 31572317) to Z.Z., the National Institutes of Health (COBRE Grant P20 GM103650) to Y.Z. and The Chinese Universities Scientific Fund to J.D. (No.2017ZB002).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Hardin PE, Panda S. Circadian timekeeping and output mechanisms in animals. (2013) Curr Opin Neurobiol. 23:724–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Crane BR, Young MW. (2014) Interactive features of proteins composing eukaryotic circadian clocks. Annu Rev Biochem 83:191–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Price JL, Blau J, Rothenfluh A, Abodeely M, Kloss B, Young MW. (1998) Double-time is a novel Drosophila clock gene that regulates PERIOD protein accumulation. Cell 94:83–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kloss B, Price JL, Saez L, Blau J, Rothenfluh A, et al. (1998) The Drosophila clock gene Double-time encodes a protein closely related to human casein kinase Iε. Cell 94:97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cyran SA, Yiannoulos G, Buchsbaum AM, Saez L, Young MW, Blau J. (2005) The Double-time protein kinase regulates the subcellular localization of the Drosophila clock protein Period. J. Neurosci 25:5430–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lin JM, Kilman VL, Keegan K, Paddock B, Emery-Le M, et al. (2002) A role for casein kinase 2α in the Drosophila circadian clock. Nature 420:816–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Akten B, Jauch E, Genova GK, Kim EY, Edery I, Raabe T, Jackson FR.(2003) A role for CK2 in the Drosophila circadian oscillator. Nat. Neurosci 6:251–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nawathean P, Rosbash M. (2004) The Doubletime and CKII kinases collaborate to potentiate Drosophila PER transcriptional repressor activity. Mol. Cell 13:213–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hara T, Koh K, Combs DJ, Sehgal A. (2011) Post-translational regulation and nuclear entry of TIMELESS and PERIOD are affected in new timeless mutant. J. Neurosci 31:9982–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Martinek S, Inonog S, Manoukian AS, Young MW. (2001) A role for the segment polarity gene shaggy/GSK-3 in the Drosophila circadian clock. Cell 105:769–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ko HW, Kim EY, Chiu J, Vanselow JT, Kramer A, Edery I. (2010) A hierarchical phosphorylation cascade that regulates the timing of PERIOD nuclear entry reveals novel roles for proline-directed kinases and GSK-3β/SGG in circadian clocks. J. Neurosci 30:12664–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chiu JC, Ko HW, Edery I. (2011) NEMO/NLK phosphorylates PERIOD to initiate a time-delay phosphorylation circuit that sets circadian clock speed. Cell. 145:357–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yu W, Houl JH, Hardin PE. (2011) NEMO kinase contributes to core period determination by slowing the pace of the Drosophila circadian oscillator. Curr Biol. 21:756–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kim EY, Jeong EH, Park S, Jeong HJ, Edery I, Cho JW. (2012) A role for O-GlcNAcylation in setting circadian clock speed. Genes Dev. 26:490–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kaasik K, Kivim¨ae S, Allen JJ, Chalkley RJ, Huang Y, et al. (2013) Glucose sensor O-GlcNAcylation coordinates with phosphorylation to regulate circadian clock. Cell Metab. 17:291–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Claridge-Chang A, Wijnen H, Naef F, Boothroyd C, Rajewsky N, Young MW. (2001) Circadian regulation of gene expression systems in the Drosophila head. Neuron. 32:657–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McDonald MJ, Rosbash M. (2001) Microarray analysis and organization of circadian gene expression in Drosophila. Cell 107:567–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hughes ME, Grant GR, Paquin C, Qian J, Nitabach MN. (2012) Deep sequencing the circadian and diurnal transcriptome of Drosophila brain. Genome Res. 22:1266–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rodriguez J, Tang CH, Khodor YL, Vodala S, Menet JS, Rosbash M. (2013) Nascent-Seq analysis of Drosophila cycling gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110: E275–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kula-Eversole E, Nagoshi E, Shang Y, Rodriguez J, Allada R, Rosbash M. (2010) Surprising gene expression patterns within and between PDF-containing circadian neurons in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:13497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Nagoshi E, Sugino K, Kula E, Okazaki E, Tachibana T, Nelson S, Rosbash M. (2010) Dissecting differential gene expression within the circadian neuronal circuit of Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 13:60–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Abruzzi KC, Zadina A, Luo W, Wiyanto E, Rahman R, Guo F, Shafer O, Rosbash M. (2017) RNA-seq analysis of Drosophila clock and non-clock neurons reveals neuron-specific cycling and novel candidate neuropeptides. PLoS Genet. 13: e1006613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Abruzzi KC, Rodriguez J, Menet JS, Desrochers J, Zadina A, Luo W, Tkachev S, Rosbash M. (2011). Drosophila CLOCK target gene characterization: implications for circadian tissue-specific gene expression. Genes Dev. 25:2374–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang J, Mauvoisin D, Martin E, Atger F, Galindo AN, Dayon L, Sizzano F, Palini A, Kussmann M, Waridel P, Quadroni M, Dulić V, Naef F, Gachon F. (2017) Nuclear Proteomics Uncovers Diurnal Regulatory Landscapes in Mouse Liver. Cell Metab. 25:102–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Robles MS, Humphrey SJ, Mann M. (2017) Phosphorylation Is a Central Mechanism for Circadian Control of Metabolism and Physiology. Cell Metab. 25:118–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ross PL, Huang YLN, Marchese JN, Williamson B, Parker K, Hattan S, Khainovski N, Pillai S, Dey S, Daniels S, Purkayastha S, Juhasz P, Martin S, Bartlet-Jones M, He F, Jacobson A, Pappin DJ. (2004) Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 3: 1154–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Plautz JD, Kaneko M, Hall JC, Kay SA.(1997) Independent photoreceptive circadian clocks throughout Drosophila. Science 278:1632–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Allada R, White NE, So WV, Hall JC, Rosbash M.(1998) A mutant Drosophila homolog of mammalian Clock disrupts circadian rhythms and transcription of period and timeless. Cell. 93:791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kadener S, Stoleru D, McDonald M, Nawathean P, Rosbash M. (2007) Clockwork Orange is a transcriptional repressor and a new Drosophila circadian pacemaker component. Genes Dev. 21:1675–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lim C, Chung BY, Pitman JL, McGill JJ, Pradhan S, Lee J, Keegan KP, Choe J, Allada R. (2007) Clockwork orange encodes a transcriptional repressor important for circadian-clock amplitude in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 17:1082–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Matsumoto A, Ukai-Tadenuma M, Yamada RG, Houl J, Uno KD, Kasukawa T, Dauwalder B, Itoh TQ, Takahashi K, Ueda R, Hardin PE, Tanimura T, Ueda HR. (2007) A functional genomics strategy reveals clockwork orange as a transcriptional regulator in the Drosophila circadian clock. Genes Dev. 21:1687–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB, Kornacker K. (2010) JTK_CYCLE: an efficient nonparametric algorithm for detecting rhythmic components in genome-scale data sets. J Biol Rhythms. 25:372–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Liang SS, Makamba H, Huang SY, Chen SH. (2006) Nano-titanium dioxide composites for the enrichment of phosphopeptides. J Chromatogr A. 1116:38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Grima B, Lamouroux A, Chélot E, Papin C, Limbourg-Bouchon B, Rouyer F. (2002) The F-box protein slimb controls the levels of clock proteins period and timeless. Nature. 420:178–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kwok RS, Li YH, Lei AJ, Edery I, Chiu JC. (2015) The Catalytic and Non-catalytic Functions of the Brahma Chromatin-Remodeling Protein Collaborate to Fine-Tune Circadian Transcription in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhang Y, Ling J, Yuan C, Dubruille R, Emery P. (2013) A role for Drosophila ATX2 in activation of PER translation and circadian behavior. Science 340: 879–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su KC, Barinova Y, Fellner M, Gasser B, Kinsey K, Oppel S, Scheiblauer S, Couto A, Marra V, Keleman K, Dickson BJ. (2007) A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 448:151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. (2009) Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods. 6:359–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Levine JD, Funes P, Dowse HB, Hall JC (2002) Signal analysis of behavioral and molecular cycles. BMC Neurosci. 3:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mauvoisin D, Wang J, Jouffe C, Martin E, Atger F, Waridel P, Quadroni M, Gachon F, Naef F. Circadian clock-dependent and -independent rhythmic proteomes implement distinct diurnal functions in mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(1):167–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Robles MS, Cox J, Mann M. In-vivo quantitative proteomics reveals a key contribution of post-transcriptional mechanisms to the circadian regulation of liver metabolism. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(1): e1004047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Deery MJ, Maywood ES, Chesham JE, Sládek M, Karp NA, Green EW, Charles PD, Reddy AB, Kyriacou CP, Lilley KS, Hastings MH. Proteomic analysis reveals the role of synaptic vesicle cycling in sustaining the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Curr Biol. 2009. December 15;19(23):2031–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Tian R, Alvarez-Saavedra M, Cheng HY, Figeys D. Uncovering the proteome response of the master circadian clock to light using an AutoProteome system. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011, 10(11):M110.007252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chiang CK, Mehta N, Patel A, Zhang P, Ning Z, Mayne J, Sun WY, Cheng HY, Figeys D. The proteomic landscape of the suprachiasmatic nucleus clock reveals large-scale coordination of key biological processes. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10(10):e1004695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yu NK, Uhm H, Shim J, Choi JH, Bae S, Sacktor TC, Hohng S, Kaang BK. Increased PKMζ activity impedes lateral movement of GluA2-containing AMPA receptors. Mol Brain. 2017,10(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Møller M, Sparre T, Bache N, Roepstorff P, Vorum H. Proteomic analysis of day-night variations in protein levels in the rat pineal gland. Proteomics, 7(12):2009–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.