Abstract

Inorganic-biological hybrid systems have potential to be sustainable, efficient, and versatile chemical synthesis platforms by integrating the light-harvesting properties of semiconductors with the synthetic potential of biological cells. We have developed a modular bioinorganic hybrid platform that consists of highly efficient light-harvesting indium phosphide nanoparticles and genetically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a workhorse microorganism in biomanufacturing. The yeast harvests photo-generated electrons from the illuminated nanoparticles and uses them for the cytosolic regeneration of redox cofactors. This enables the decoupling of biosynthesis and cofactor regeneration, facilitating a carbon- and energy-efficient production of the metabolite shikimic acid – a common precursor for several drugs and fine chemicals. Our work provides a platform for the rational design of biohybrids for efficient biomanufacturing processes with higher complexity and functionality.

One Sentence Summary:

Semiconductor nanoparticles assembled on genetically engineered yeast enables photochemical metabolite production via rationally designed metabolic pathways.

Inorganic-biological hybrid systems combine the light harvesting efficiency of inorganic systems with established biosynthetic pathways in live cells, thus promising a sustainable and efficient biochemical synthesis platform (1, 2). Comprehensive solar-to-chemical production has been investigated with bioinorganic hybrid systems including semiconductor-conjugated hydrogenases for biohydrogen production (3–5), long wavelength-absorbing nanomaterials integrated into plants for enhanced photosynthetic efficiency (6), and photoelectrodes coupled with whole cells for hydrogenation reactions (7), and atmospheric CO2 and N2 fixation (8–11).

Microorganisms are used in biomanufacturing because of their rapid proliferation and ability to convert renewable carbon sources into higher value chemicals through genetically programmable multi-step catalysis (12). In the context of inorganic-biological hybrids, autotrophic bacteria have been investigated intensively, with a focus on simple organic molecules (7–14). Interfacing heterotrophic organisms with light-harvesting inorganics may provide advantages, such as increased efficiency in the production of high-value chemicals (15–17). Common heterotrophs (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae) are already used widely in industrial settings because of the large catalog of target metabolites accessible through genetic manipulation tools (18). The well-studied biology of canonical model organisms may provide access to better genetic and analytical tools to unravel the mechanisms governing electron transport and metabolic flux in biohybrid systems (19).

Of particular interest is the regeneration of the redox cofactor NADPH because of its central role as a co-substrate in biosynthetic pathways (20). It is strongly intertwined with biomass production, and it is a common bottleneck in the production of metabolites through microbial cell factories (21). The primary source of NADPH in yeasts is the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), which oxidizes a hexose sugar with concomitant loss of two equivalents of CO2, decreasing theoretical carbon yields (22). Therefore, decoupling NADPH generation from central carbon metabolism may help maximize carbon flux for the production of desired metabolites (20).

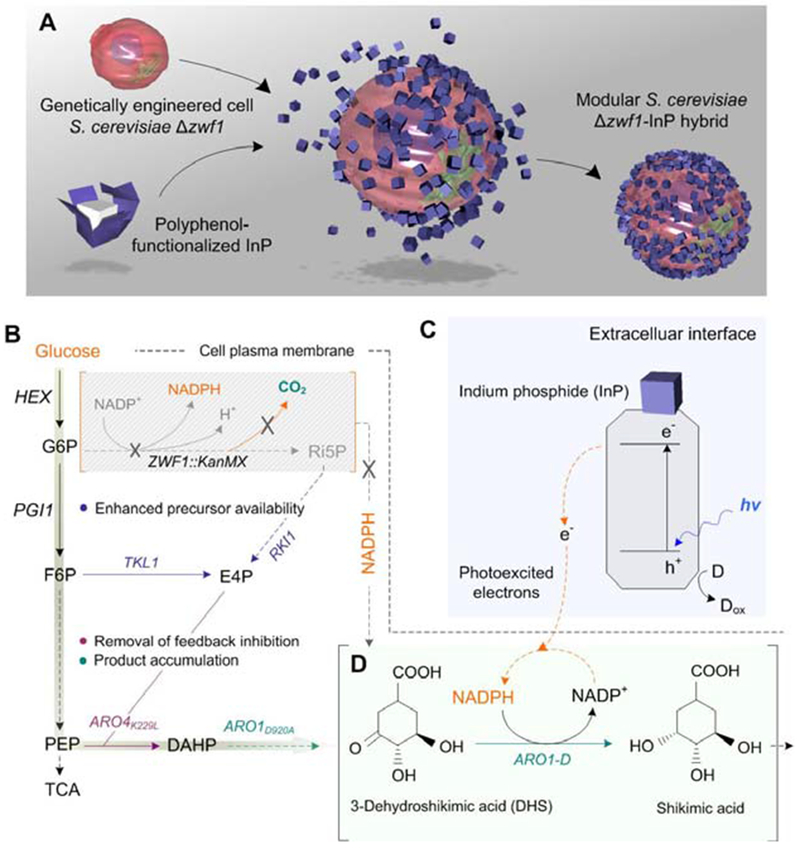

We developed a S. cerevisiae-indium phosphide (InP) hybrid system, which combines rationally designed metabolic pathways and the electron donation capabilities of illuminated semiconductors (Fig. 1, fig. S1). Indium phosphide (InP) was selected as a photosensitizer in this bioinorganic hybrid system (fig. S2) because its direct band gap (Eg = 1.34 eV) enables efficient absorption of a large fraction of the solar spectrum and it is positioned appropriately to accept electrons from various species in the culture medium (23). Additionally, its high stability under oxygenic conditions and biocompatibility suggest that InP is an ideal material choice for biological integration (24). InP nanoparticles were prepared independently (fig. S3) and subsequently assembled on genetically engineered yeast cells using a modified, biocompatible, polyphenol-based assembly method (25) (Fig. 1A, fig. S1). Yeast strain S. cerevisiae Δzwf1 was selected for the engineering of the bioinorganic hybrid. The deletion of the gene ZWF1, encoding the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase enzyme, disrupts the oxidative portion of the PPP (Fig. 1B) (22), causing a dramatic decrease in cytosolic NADPH generation capacity (Fig. 1C). We examined the integrated function of the biohybrid system to regenerate NADPH, which is essential for the biosynthesis of shikimic acid (SA), a precursor of aromatic amino acids (Fig. 1C,E). S. cerevisiae Δzwf1 was genetically engineered to overexpress four genes to enhance carbon flux through the SA pathway (Fig. 1C) (22). The pentafunctional protein Arol, which catalyzes the reduction of 3-dehydroshikimic acid (DHS) to SA, is selective for NADPH, and a low availability of cytosolic NADPH directly impacts the production of SA, leading to elevated accumulation of its precursor DHS. In previous examples of biohybrid systems, light harvesting semiconductor particles attached to the surface of bacteria were able to provide reducing equivalents to central metabolic processes (12). Herein, we rationalized that the S. cerevisiae Δzwf1-InP hybrid system (fig. S4) could operate similarly, with electrons flowing from the illuminated, surface-bound InP particles to the regeneration of NADPH from NADP+ inside the cell (Fig. 1C,D). This NADPH can fuel the ultimate conversion of DHS to SA (26). Therefore, the S. cerevisiae Δzwf1-InP hybrid both enables us to evaluate the efficiency of NADPH regeneration and leads to the enhanced biosynthesis of a highly sought-after molecule through photon energy conversion.

Fig. 1. Assembly of S. cerevisiae-InP hybrids and rationally designed metabolic pathways.

(A) InP nanoparticles were first functionalized with polyphenol moieties, then assembled on the surface of genetically engineered yeast to form modular inorganic-biological hybrids. (B) Metabolic engineering scheme for overproduction of SA. S. cerevisiae Δzwf1 has the oxidative PPP disrupted (ZWF1), leading to low cytosolic NADPH pools, which directly impacts the SA pathway. It also reduces carbon loss in the form of CO2, but leads to a smaller pool of cytosolic NADPH. (C,D) Schematic of cellular NADPH regeneration assisted by photogenerated electrons from InP nanoparticles. Abbreviations: G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; Ri5P, ribulose-5-phosphate; E4P, erythrose-4-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; DAHP, 3-deoxy-D-arabinoheptulosonate-7-phosphate; HEX, hexokinase; ZWF1, glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase; PGI1, phosphoglucose isomerase; RKI1, ribose-5-phosphate ketol-isomerase; TKL1, transketolase; ARO4K229L, feedback insensitive DAHP synthase; ARO1D920A, mutant pentafunctional aromatic enzyme.

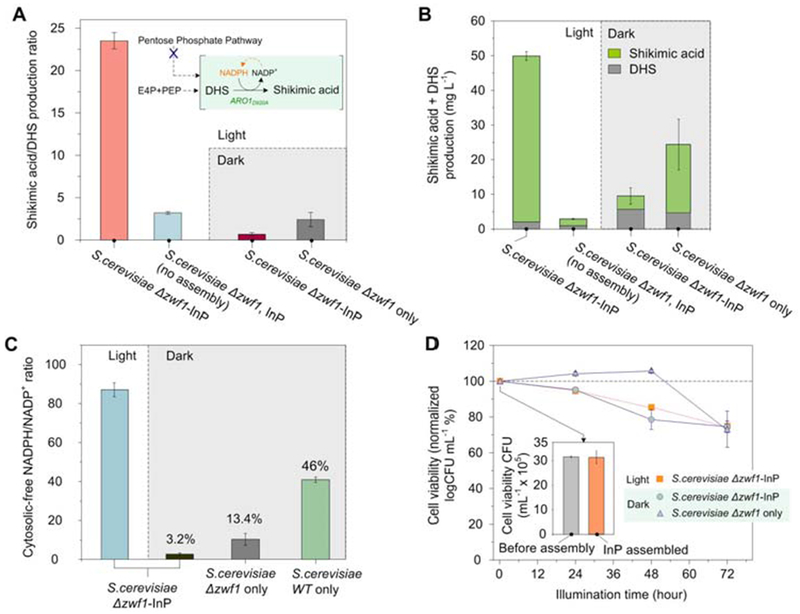

We designed a series of control experiments in which the presence of light and the InP nanoparticles was varied (fig. S5). After 72 hours of aerobic growth, S. cerevisiae Δzwf1-InP hybrids under illumination (5.6 mW cm−2, fig. S6) achieved the highest conversion rate of DHS to SA with a SA/DHS ratio of 23.5 ± 1.6 (Fig. 2A, fig. S7-S9). In contrast, a control experiment without illumination led to a ratio of only 0.67 ± 0.3 (fig. S10). Similarly, a low SA/DHS ratio was observed in the presence of InP nanoparticles that were not assembled on the cell surface, suggesting the importance of proximity in enabling photochemical synthesis. This is in line with recent reports describing the ability of cell wall-bound components in yeasts to contribute to extracellular electron transport through electron “hopping” mechanisms (27). S. cerevisiae Δzwf1 in the absence of InP also showed lower SA/DHS ratio, regardless of illumination scheme (fig. S11,S12). The total SA production of the illuminated biohybrid system was superior to all other conditions, with a final titer of 48.5 ± 2.1 mg L−1, showing an 11-fold increase compared to its counterpart with no illumination, and a 24-fold increase compared to engineered cells in the presence of unattached InP nanoparticles (Fig. 2B). SA conversion yield also increased with higher light intensities to a point, but decreased under the highest light intensity, possibly due to metabolic saturation or photodamage to the cells (fig. S13).

Fig. 2. >Physiological and metabolic characterization of the S. cerevisiae-InP hybrid system.

(A) Comparison of SA/DHS ratios in hybrids and in yeast-only fermentations with light and dark conditions. (B) Total accumulation of SA and DHS after 72 h of growth. (C) Estimation of cytosolic free NADPH/NADP+ ratio based on the conversion of DHS to SA. (D) Cell viability assay based on counting of colony forming units (CFU), performed on rich solid media. Insert shows that the preparation of the bioinorganic hybrids does not affect initial CFU amount. Variation is represented by standard error from three independent replicates for all data points.

The SA/DHS ratio has previously been shown to serve as a metabolic readout for cytosolic levels of NADPH/NADP+ (28). The highest NADPH/NADP+ ratio calculated for the illuminated biohybrid experiment reaches a value of 87.1 (Fig. 2C). Notably, this value was higher than even that measured for InP-free and -integrated wild-type S. cerevisiae, which possesses the fully functional machinery to produce NADPH through the oxidative PPP (fig. S14). S. cerevisiae Δzwf1 in darkness showed the lowest NADPH/NADP+ ratios regardless of the presence of InP. These results support the contention that irradiated, cell surface-assembled InP can drive the regeneration of cofactor NADPH, facilitating the conversion of DHS to SA. Cell viability based on colony-forming units (CFU) assays on nutrient-rich solid media showed no differences before and after the assembly of InP nanoparticles (Fig. 2D), confirming the biocompatibility of the particle assembly protocol. After the first 24 hours of culture, cell count was lower for the biohybrids, regardless of the illumination scheme, suggesting that nanoparticle attachment could cause cell stress during fermentations (see Supplementary Materials for further discussion).

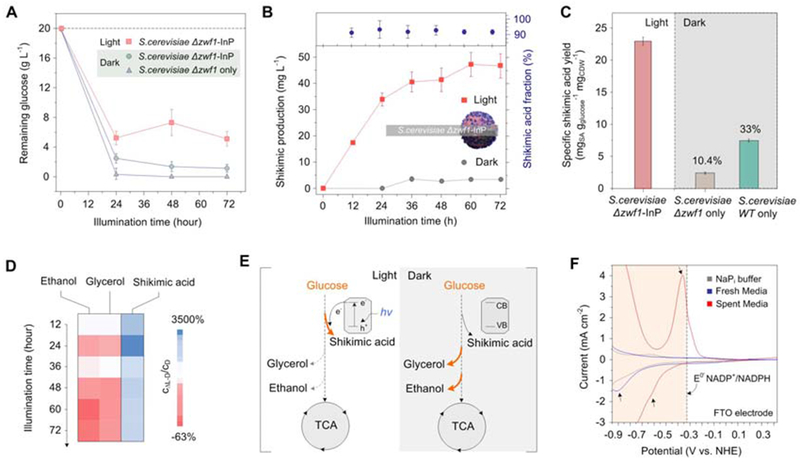

To further evaluate the metabolic performance of the biohybrid systems, we characterized their ability to consume glucose and variations in carbon flux. Glucose was fully consumed by the bare cells during the first 24 hours, while nearly 25% of the total initial glucose remained unused in the complete biohybrid scheme (Fig. 3A). The SA production kinetics in the S. cerevisiae-InP hybrids showed that the conversion of DHS to SA occurred throughout the entire illumination period (Fig. 3B), suggesting a continuous supply of NADPH and potential accumulation of biosynthetic intermediates along the SA pathway that lags behind glucose consumption (29). This was also supported by the consistently high mass fractions of SA (~90%). The specific SA yields of S. cerevisiae Δzwf1-InP hybrids surpassed those of the S. cerevisiae Δzwf1 and the wild-type bare cells cultured in darkness, respectively (Fig. 3C). The light-to-SA conversion efficiency reached a maximum of 1.58 ± 0.05 % at 12 hours after the start of fermentation and dropped as SA production plateaued (fig. S15). To unravel the variations in the central carbon metabolism caused by the illumination of InP in the biohybrids, we measured the production of secreted byproducts linked to other pathways, including ethanol and glycerol (fig. S13,S14). Fig. 3D shows that the production of these byproducts by the illuminated biohybrids (CL) was lower than its counterpart under dark conditions (CD). This implies that the surface-assembled, photoexcited InP shunts carbon in S. cerevisiae Δzwf1 towards the desired SA pathway, with less activity in alternative pathways for NADPH regeneration (e.g., aldehyde dehydrogenase, Ald6) (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3. Carbon utilization, cytosolic-free NADPH, and electron transfer in S. cerevisiae-InP hybrid system.

(A) Glucose consumption over the course of 72 hour culture. (B) SA production profiles in light and dark conditions. SA/DHS ratio, expressed as mass fraction (SA/(SA+DHS)). (C) Specific SA yield based on consumed glucose and cell dry weight (CDW). (D) Percent variation in SA and byproduct formation of the bioinorganic hybrids under light (CL) versus dark (CD) conditions over time. (E) Proposed metabolic flux distributions based on total SA plus DHS concentrations and byproduct formation (glycerol and ethanol). (F) DPV of culture medium before and after growth experiment. Arrows indicate electrochemical signatures from possible species with sufficient reducing potential to convert NADP+ to NADPH. Variation is represented by standard error from three independent replicates for all data points.

While membrane bound hydrogenases have been invoked to explain the ability of previously reported analogous bacterial systems to make use of photochemically generated electrons (29–31), S. cerevisiae is surrounded by a cell wall composed of extracellular polymeric substances that would prevent direct contact between membrane-bound proteins and the InP particles. The need for proximity between polyphenol-functionalized InP particles and the cells suggests that the cell wall might mediate electron transfer in our biohybrids (27). Differential pulse voltammety (DPV) performed on the spent medium after fermentation (Fig. 3F, fig. S15) exhibited peaks more negative of the thermodynamic potential for NADP+/NADPH (E° = −0.324 V vs. NHE @ pH 7). A higher redox activity can be seen in the spent media after S. cerevisiae Δzwf1 growth, suggesting that soluble redox-active species likely also play a role in electron transfer, as has been reported for yeast-based microbial fuel cells without exogenous mediators (32). The electron transfer mechanism in these S. cerevisiae Δzwf1-InP hybrids remains an active subject of investigation, as multiple possible mechanisms could exist in our biohybrid system, e.g., soluble mediators and cell wall-bound redox mediators.

The development of inorganic-biological hybrid system in yeast will enable expansion of this overall approach to the production of higher-value metabolites. For example, the production of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, which is already established in yeast, requires the activity of more than ten membrane-bound cytochrome P450 oxidoreductases that depend on NADPH as an electron donor (18). The technology presented in this work may thus elevate the production efficiency of alkaloid natural products and other drugs and nutraceuticals, though practical implementation will require the development of illumination sources that interface with scaled-up fermenters. Our synthetic scheme is highly modular enabling a mix-and-match approach, makes use of cheap components, and could be compatible with existing workhorse cellular chassis and a wide range of particle-cell combinations. A more thorough understanding of electron transport mechanisms and global changes to metabolic flux will undoubtedly help design and implement even better biohybrid systems. These would make use of alternative energy sources to streamline metabolic efficiency. With an ever-growing set of genetic tools, functional nanoparticles, and cell types, modular biohybrid platforms are likely to enable efficient and economical biochemical production of valuable and challenging targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Joseph Richardson, Guillermo Bazan, Chelsea Catania, Blaise Tardy and Yana Klyachina for helpful discussions. We thank the Shao group at Iowa State University for providing the shikimic acid constructs. We thank Elizabeth Benecchi and Maria Ericsson at Harvard Medical School electron microscopy facility for help on microtoming techniques. Work was performed in part at the Center for Nanoscale Systems at Harvard University and the NSF’s National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network (NNIN).

Funding: Work in the N.S.J. laboratory is supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01DK110770-01A1) and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University. J.G. acknowledges the C.H. Foundation Fellowship for support. K.K.S. acknowledges the Harvard University Center for the Environment Fellowship for support.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: Harvard University and the Wyss Institute have filed a patent on this work.

Data and Materials Availability: All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to N.S.J. The primary strain used in this study – S. cerevisiae BY4741 zwflΔ (MATa, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, zwf1Δ::KanMX) – was obtained under MTA from Iowa State University.

Supplementary Materials:

Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S19

References 1-35

References and Notes

- 1.Blankenship RE et al. , Science 332, 805 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakimoto KK, Kornienko N, Yang P, Acc. Chem. Res 50, 476 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Goff A et al. , Science 326, 1384 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reisner E, Powell DJ, Cavazza C, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Armstrong FA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 131, 18457 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown KA, Wilker MB, Boehm M, Dukovic G, King PW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 134, 5627 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giraldo JP et al. , Nat. Mater 13, 400 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowe SF et al. , ACS Catal. 7, 7558 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu C, Sakimoto KK, Colón BC, Silver PA, Nocera DG, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 114, 6450 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown KA et al. , Science 352, 448 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu C, Colón BC, Ziesack M, Silver PA, Nocera DG, Science 352, 1210 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichols EM et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 112, 11461 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakimoto KK, Wong AB, Yang P, Science 351, 74 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H et al. , Science 335, 1596 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei W et al. , Sci. Adv 4, eaap9253 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrgård MJ et al. , Nat. Biotech 26, 1155 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Förster J, Famili I, Fu P, Palsson BØ, Nielsen J, Genome Res 13, 244 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keasling JD, Science 330, 1355 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galanie S, Thodey K, Trenchard IJ, Interrante MF, Smolke CD, Science 349, 1095 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen J, Keasling JD, Cell 164, 1185 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X et al. , Chem 2, 621 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li S, Li Y, Smolke CD, Nat. Chem 10, 395 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suástegui M et al. , Metab. Eng 42, 134 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Wezemael A-M, Laflere W, Cardon F, Gomes W, J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem 87, 105 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakimoto KK et al. , J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 1978 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo J et al. , Nat. Nanotech 11, 1105 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suástegui M, Guo W, Feng X, Shao Z, Biotechnol. Bioeng 113, 2676 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao Y et al. , Sci. Adv 3, e1700623 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J et al. , Sci. Rep 5, 12846 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kornienko N et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 113, 11750 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilker MB et al. , J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 4316 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandey K, Islam ST, Happe T, Armstrong FA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 114, 3843 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hubenova Y, Mitov M, Bioelectrochemistry 106, 177 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.