Abstract

Introduction

In the past decade, messenger RNA (mRNA) has been extensively explored in a wide variety of biomedical applications. However, efficient delivery of mRNA is still one of the key challenges for its broad applications in the clinic. Recently, lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPNs) are evolving as a promising class of biomaterials for RNA delivery, which integrate the physicochemical properties of both lipids and polymers. We previously developed an N1,N3,N5-tris(2-aminoethyl)benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide (TT) derived lipid-like nanomaterial (TT3-LLN) which was capable of effectively delivering multiple types of mRNA. In order to further improve the delivery efficiency of TT3-LLN, in this study, we focused on studying the effects of incorporating different polymers on establishing LPNs and aimed to develop an optimized lipid polymer hybrid nanomaterial for efficient mRNA delivery.

Methods

We incorporated a series of biodegradable and biocompatible polymer materials into the formulation of TT3-LLNs to develop LPNs. mRNA delivery efficiency of different LPNs were evaluated and a systematic orthogonal optimization was further carried out.

Results

Our data indicated that PLGA4 (MW 24,000–38,000 g/mol) dramatically increased delivery efficiency of TT3-LLNs in comparison to other polymers. Further optimization identified PLGA4-7 LPNs (PLGA:mRNA = 9:1, mass ratio; TT3:DOPE:Cholesterol:DMG-PEG2000 = 25:25:45:0.75, molar ratio) as a lead formulation, which displayed significantly enhanced delivery of two types of mRNA in three different human cell lines as compared with TT3-LLNs.

Conclusions

Results from this study potentially provide new insights into developing LPNs for mRNA based therapeutics.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12195-018-0536-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPNs), mRNA therapeutics, Lipids, Polymers, Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) or PLGA, Orthogonal experiment design

Introduction

Messenger RNA (mRNA)-based therapeutics has been rapidly developed for a number of biomedical applications, such as vaccines for infectious diseases and cancers, protein replacement therapy, and genome editing.12,18,21,22,25,26,35 mRNA-based therapy possesses advantages over other nucleic acid-based approaches due to its endogenous translation process in the cytosol and no potential risk of genome mutagenesis.15,28,32 However, the instability and insufficient translatability of mRNA remain a limitation to achieving maximized therapeutic windows.27 Therefore, new types of nanomaterials are needed to improve mRNA delivery and the corresponding protein expression.

Biomaterial-based nanoparticles, as non-viral delivery vehicles, have shown great potential for effective delivery of mRNA.10,15,22,29 For example, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) or lipid-like nanoparticles (LLNs) were reported for a wide variety of mRNA delivery.16,21,23,25,36 Meanwhile, polymeric nanoparticles, constructed with biodegradable polymers such as poly(d,l-lactic acid) (PLA), poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA), dextran, and hyaluronic acid (HA), are also widely applied for RNA delivery since polymeric components are able to form stable nanoparticles and controlled release the cargos.1,3–6,8,13,14,19,30,33,34 In addition, lipid conjugated poly(b-amino esters) (PBAEs) and poly(glycoamidoamine) were reported for effective delivery of mRNA.7,17 Recently, lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPNs), by integrating the complementary properties of lipid and polymeric nanomaterials, are emerging as a class of nanomaterials for RNA delivery.2,11,31,37 Although various combinations of lipids and polymers were applied in establishing LPNs for siRNA delivery, little is known about the effects of different polymers on lipid based nanomaterials for mRNA delivery.

We previously developed a series of N1,N3,N5-tris(2-aminoethyl)benzene-1,3,5 tricarboxamide (TT) derived lipid-like nanomaterials for mRNA delivery.21 Among these TT-LLNs, TT3 LLN was found as a lead nanomaterial, which demonstrated capability of effectively delivering multiple types of mRNA.16,21 With TT3 as a significant lipid derived material for the development of LPNs, herein, we aimed to integrate an appropriate polymer material in establishing LPNs together with TT3 lipids for improving mRNA delivery. Therefore, we studied the effects of incorporating different biodegradable and biocompatible polymer materials into the TT3-LLNs on their delivery efficiency. A lead LPN was identified after initial screenings and an orthogonal optimization of the LPNs. Our findings indicated that PLGA4 (MW 24,000–38,000 g/mol) was a polymer component significantly superior to other polymer materials when formulating TT3-LPNs. Through further orthogonal optimization on the formulation of PLGA4 incorporated TT3-LPNs, we identified a lead LPNs formulation, PLGA4-7 LPNs, which demonstrated significantly enhanced mRNAs delivery efficiency than TT3-LLNs in vitro.

Methods and Materials

Materials

Firefly luciferase mRNAs (FLuc mRNAs) and enhanced green fluorescent protein mRNA (eGFP mRNAs) were purchased from TriLink Biotechnologies, Inc. (San Diego, CA). DOPE was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc (Alabaster, AL). Ribogreen reagent and fetal bovine serum were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Polymers (Table 1) and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used without further purification.

Table 1.

Properties of polymers applied in establishing LPNs.

| Polymers | Properties | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilicity | Molecular weight/viscosity | Other | |

| PLGA1 | Hydrophobic | MW 24,000–38,000 g/mol, viscosity 0.32–0.44 dL/g | Ester terminated |

| PLGA2 | Hydrophobic | MW 7000–17,000 g/mol, viscosity 0.16–0.24 dL/g | Ester terminated |

| PLGA3 | Hydrophobic | MW 38,000–54,000 g/mol, viscosity 0.45–0.60 dL/g | Ester terminated |

| PLGA4 | Hydrophobic | MW 24,000–38,000 g/mol, viscosity 0.32–0.44 dL/g | Acid terminated |

| PLA | Hydrophobic | MW 18,000–28,000 g/mol, viscosity 0.25–0.35 dL/g | Ester terminated |

| Dextran | Hydrophilic | MW 15,000–25,000 g/mol | – |

| HA | Hydrophilic | MW 1.5–2.2 million g/mol | – |

Note All the information regarding the properties of polymer materials listed in the table are provided by Sigma-Aldrich. Viscosity data are given based on the condition: 0.1% (w/v) in chloroform (25 °C, Ubbelohde) (size 0c glass capillary viscometer)

Cell Culture

Human hepatoma Hep3B cell line, human embryonic kidney 293T cell line, and human acute monocytic leukemia THP-1 cell line were all purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Hep3B cells were cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM, Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY); HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY); and THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 Medium (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY). All the cells were maintained in media supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS at 37 °C incubator with an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Formulation and Characterization of mRNA-Loaded LPNs

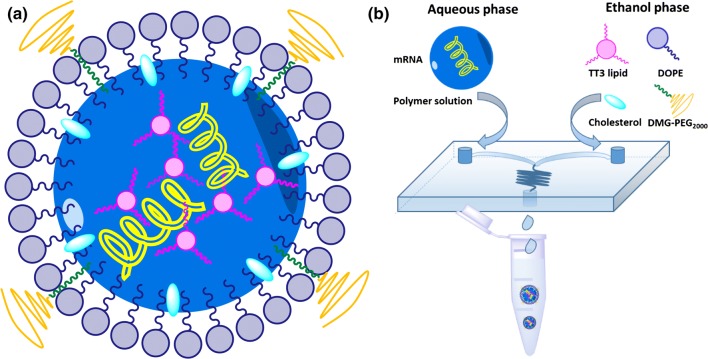

To prepare LPNs formulations for the initial screening, TT3 was formulated with DOPE, cholesterol, DMG-PEG2000 at the molar ratio of 20/30/40/0.75 in ethanol phase.21 Polymer solutions were prepared by dissolving polymers in acetone (hydrophobic polymers) or citrate acid buffer (hydrophilic polymers). For initial screenings and orthogonal optimization studies, each of the polymer solutions was added respectively to the FLuc mRNA or eGFP mRNA solution in the aqueous phase, and then the aqueous phase was mixed with ethanol phase by pipetting. For cryo-TEM imaging and stability studies, LPNs formulations were obtained by mixing aqueous and ethanol phases via a microfluidic device (Precision NanoSystems, Vancouver, BC, Canada) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrations of (a) structure of LPNs and (b) the process of formulating LPNs through a microfluidic device.

Particle size and zeta potential of LPNs were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using NanoZS Zetasizer (Malvern, Worcestershire, U.K.) at 25 °C with a scattering angle of 173°. Entrapment efficiency of LPNs was determined using the Ribogreen assay as reported previously.20,21

LPNs Luciferase Expression Assay

Hep3B cells were seeded in white 96-well plates at the density of 2 × 104 cells per well, allowed to attach to plates for overnight, and then treated with FLuc mRNA encapsulated LPNs at the dose of 50 ng mRNA/well. Each sample was tested in triplicate. Culture medium containing LPNs was carefully discarded 6, 12 or 24 h after transfection, followed by addition of a mixture of 50 μL luciferase substrate (Bright-Glo reagent, Promega, Madison, WI) and 50 μL of serum-free EMEM to each well. Five minutes later, the relative luminescence intensity was measured with the SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC., Sunnyvale, CA). Free FLuc mRNA was used as a control.

LPNs eGFP Expression Assay

Hep3B cells were seeded in 24-well plates at the density of 8 × 104 cells per well. After overnight incubation, the cells were treated with eGFP mRNA encapsulated LPNs at the dose of 125 ng mRNA/well. After 24 h of treatment, the cells were collected, washed, and suspended in 400 µL PBS. Relative green fluorescence intensity was then quantified using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Orthogonal Array Experimental Design

In order to identify an optimal composition ratio of the formulation components in PLGA4 LPNs, an orthogonal array study was carried out as previously reported.21 Three formulation components (TT3, DOPE and cholesterol) at each three different levels were assigned in the orthogonal experiments with a fixed TT3: mRNA ratio (10:1). A series of eGFP mRNA encapsulated PLGA4-LPNs (PLGA4-1 to PLGA4-9) were prepared according to the orthogonal array design table L9 (33) and used to transfect Hep3B cells at the dose of 50 ng mRNA/well. Green fluorescence intensity of Hep3B cells from each formulation groups was quantified 24 h after treatment using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The average eGFP intensity (Kn) of each component (factor) at the same molar ratio (level) was calculated and used to depict the impact of the levels and factors on delivery efficiency. The best formulation ratio was predicted and validated by the impact trend curve.

Cryo-Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM) and Stability

Cryo-TEM specimens were prepared by using plunge-freezing in a FEI Vitrobot (Mark IV).9,36 Low-dose cryo-TEM imaging was carried out in a FEI Tecnai G2 F20 200 kV microscope equipped with an UltraScan 4 K CCD camera and a Gatan twin-blade anticontaminator.9

For stability studies, the freshly prepared PLGA4-7 LPNs were dialyzed in PBS buffer using Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes (3.5 K MWCO, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and stored at 4 °C. Particle size of PLGA4-7 LLNs were monitored on 0, 1, 3, 5, 7 and 14 days post preparation using a NanoZS Zetasizer (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) at 25 °C with a scattering angle of 173°.

Dose Dependency and Delivery Efficiency of PLGA4-7 LPNs in Different Cell Lines

For dose dependency study, Hep3B cells were seeded in 24-well plates at the density of 8 × 104 cells per well. After overnight incubation, the cells were treated with eGFP mRNA encapsulated TT3-LLNs or PLGA4-7 LPNs at the dose of 25, 50 and 100 ng mRNA/well, respectively. After 24 h of treatment, the cells were collected, washed, and suspended in 400 µL PBS. Relative green fluorescence intensity was then quantified using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

For delivery efficiency study, 293T cells or THP-1 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at the density of 8 × 104 cells per well. After overnight incubation, the cells were treated with eGFP mRNA encapsulated LPNs at the dose of 50 ng mRNA/well. After 24 h of treatment, the cells were collected, washed, and suspended in 400 µL PBS. Green fluorescence intensity was then quantified using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). All the experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Results

Construction of Lipid Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles (LPNs)

In order to study the effects of incorporating different polymer materials on the delivery efficiency of the previously reported TT3-LLNs, four types of polymers (PLGA, PLA, dextran and HA, Table 1) were used to develop TT3-derived LPNs (Fig. 1a). Among these polymers, PLGA and PLA are hydrophobic polymers while dextran and HA are hydrophilic polymers. PLGA1 to PLGA4 are four different PLGA polymers with either different molecular weight/viscosity or different terminus (Table 1).

As illustrated in Fig. 1b, TT3, DOPE, cholesterol, and DMG-PEG2000 were mixed in the ethanol phase using the previously optimized formulation ratio (TT3/DOPE/Cholesterol/DMG-PEG2000 = 20/30/40/0.75, molar ratio).21 Each of the polymers was incorporated into previously reported TT3-LLN formulation by adding the polymer solution to the mRNA solution in aqueous phase at three different polymer to mRNA mass ratios, which were 9:1 (A), 3:1 (B), and 1:1 (C). TT3-derived LPNs were then afforded by mixing the aqueous phase with the ethanol phase.

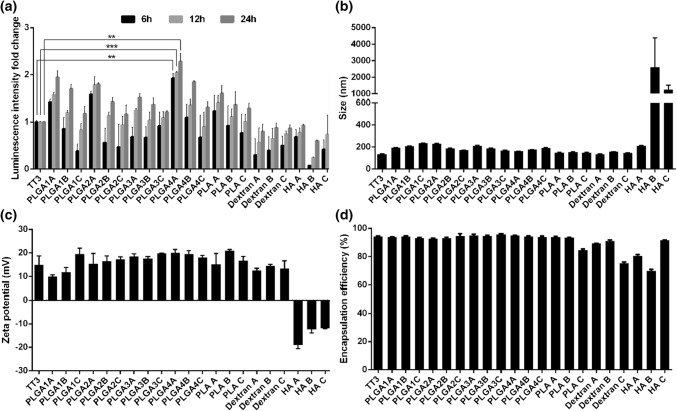

Evaluation of LPNs Through a Luciferase Expression Assay

In order to investigate mRNA delivery efficiency of the newly formulated LPNs with different polymers, we utilized a luciferase expression assay in human hepatoma Hep3B cell line for an initial screening. Cells were treated with different LPNs encapsulated with firefly luciferase mRNAs (FLuc mRNAs) and bioluminescence intensity of each group was subsequently quantified at the following time points 6, 12 and 24 h (Fig. 2a). Luciferase expression assay revealed the following trends: (i) PLGA4A LPNs group showed the highest bioluminescence intensity as compared with TT3-LLNs and other LPNs at all time points; (ii) Generally, hydrophobic polymer incorporated LPNs showed better transfection efficiency than TT3-LLNs and hydrophilic polymer incorporated LPNs, especially at prolonged time points (12 and 24 h); (iii) Regarding PLGA and PLA LPNs at 24 h, LPNs in group A (polymer: mRNA = 9:1, mass ratio) generally are better than LPNs in groups B and C (polymer: mRNA = 3:1 and 1:1, mass ratio). Results indicated that the incorporation of polymer material into TT3-LLNs had significant effects on mRNA delivery efficiency. Hydrophobic polymers potentially led to increased mRNA delivery efficiency. Moreover, the 9:1 polymer-to-mRNA mass ratio was better than 3:1 and 1:1 for LPNs development. This ratio was selected as a representative of each LPNs group for further studies.

Figure 2.

Characterizations of LPNs for mRNA delivery using a luciferase assay. (a) Fold changes of luciferase expression levels using different polymer incorporated LPNs as compared to TT3 LLNs; (b) size, (c) zeta potential, and (d) encapsulation efficiency of different FLuc mRNA encapsulated LPNs. Note A, B and C represents the mass ratio of polymer to mRNA equal to 9:1, 3:1 and 1:1, respectively. (n = 3; two-tailed t test; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

Meanwhile, the size, zeta potential and encapsulation efficiency of each LPNs were also characterized (Figs. 2b–2d and Supplementary Information Table S1). The size of LPNs were in the range of 100–250 nm, except the HA groups. Most LPNs showed positive zeta potential and within the range of 10–20 mV, while HA-LPNs were negative in zeta potential. For the encapsulation efficiency, hydrophobic polymers LPNs exhibited similar encapsulation efficiency (> 90%) as TT3-LLNs, which were better than most of hydrophilic polymers LPNs (around 80%).

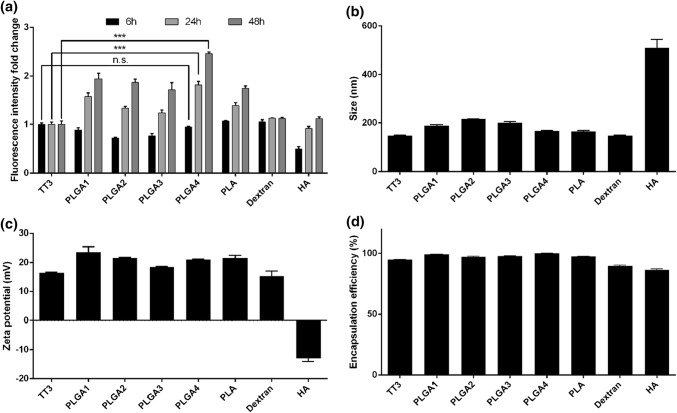

Delivery Efficiency of LPNs Encapsulating eGFP mRNAs

In order to further verify the effects of polymers on the delivery efficiency of TT3-LLNs, another reporter mRNA, enhanced green fluorescent protein mRNA (eGFP mRNA), was used to conduct eGFP expression assay in Hep3B cells. In this assay, the 9:1 polymer-to-mRNA mass ratio was selected as a representative of each LPNs group. According to results collected from flow cytometry (Fig. 3a), a similar trend was observed in different LPNs. All hydrophobic polymer LPNs showed prolonged and increased transfection efficiency as compared with TT3-LLNs and hydrophilic polymer LPNs. PLGA4 LPNs group showed the highest eGFP intensity at 24 h and 48 h time points among all the groups. Moreover, all the physicochemical properties of eGFP mRNA encapsulated LPNs were similar to that of FLuc mRNA encapsulated LPNs (Figs. 3b–3d and Supplementary Information Table S2). Based on the in vitro screening results from luciferase and eGFP expression assays, PLGA4 LPNs significantly increased the delivery efficiency of TT3-LLNs by over two fold. Therefore, PLGA4 LPNs were selected as the lead LPNs for further studies.

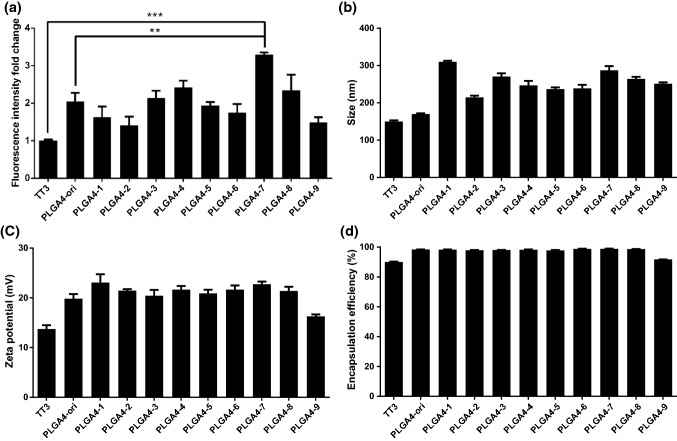

Figure 3.

Evaluation of LPNs to deliver eGFP mRNA. (a) Fold changes of eGFP expression levels using different polymer incorporated LPNs as compared to TT3 LLNs; (b) size, (c) zeta potential, and (d) encapsulation efficiency of different eGFP encapsulated LPNs. (n = 3; two-tailed t-test; n.s. not significant; ***p < 0.001).

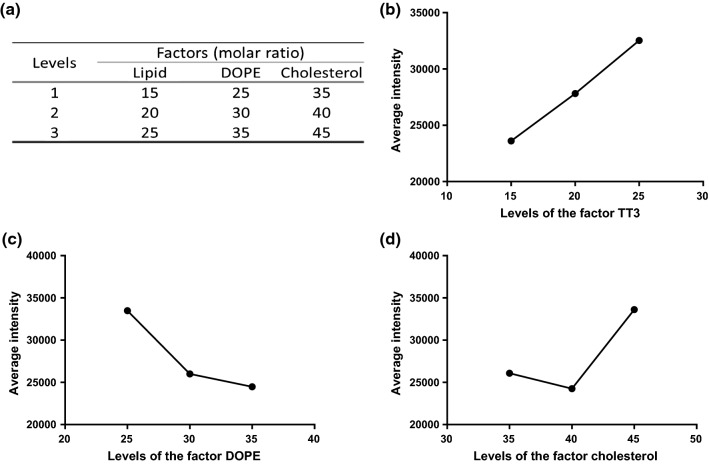

Optimization of PLGA4 LPNs Formulation Through an Orthogonal Experiment Design

In order to identify an optimal molar ratio of the formulation components in the currently selected PLGA4 LPNs, an orthogonal array design was applied in the optimization as previously reported.21 Three out of four formulation components (TT3, DOPE and cholesterol; Fig. 4a) were assigned in the following orthogonal experiments with a fixed TT3: mRNA molar ratio (10:1) and the selected polymer: mRNA mass ratio (9:1). A series of PLGA4 LPNs (PLGA4-1 to PLGA4-9) were prepared according to the orthogonal array design table L9 (33) and used to transfect Hep3B cells with eGFP mRNA. Results collected from flow cytometry at 24 h (Fig. 5a) showed that PLGA4-7 LPNs group produced the highest eGFP intensity. Besides, all the LPNs in the orthogonal array showed similar physicochemical properties (Figs. 5b–5d and Supplementary Information Table S3). To further predict the best ratio of these formulation components, an analysis of orthogonal array was carried out. The average eGFP intensity of each component (factor) at the same molar ratio (level) was calculated and used to measure the impact of the levels and factors on delivery efficiency (Figs. 4b–4d). According to the trend analysis results, PLGA4-7 LPNs (TT3/DOPE/Cholesterol/DMG-PEG2000 = 25/25/45/0.75, molar ratio) was predicted as the optimal formulation ratio based on the orthogonal assay and selected as an optimized formulation for further studies.

Figure 4.

An orthogonal array analysis of PLGA4-LPNs. (a) Three levels for each formulation component: TT3, DOPE and cholesterol; the impact trend of TT3 (b), DOPE (c), and cholesterol (d) on delivery efficiency.

Figure 5.

An orthogonal array optimization of PLGA4-LPNs. (a) Fold changes of eGFP expression levels of different PLGA4-LPNs in the orthogonal array as compared to TT3 LLNs; (b) size, (c) zeta potential, and (d) encapsulation efficiency of different PLGA4-LPNs. (n = 3; two-tailed t-test; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

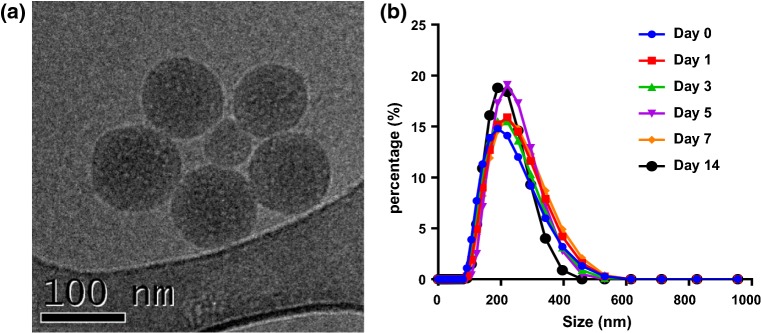

We also performed further characterizations on the optimized PLGA4-7 LPNs to ensure optimal physicochemical properties. Based on the Cryo-TEM imaging data, PLGA4-7 LPNs were spherical nanoparticles with the size of around 100 nm in diameter (Fig. 6a). A stability assay further indicated that particle size of PLGA4-7 LPNs remained stable for a minimum of 2 weeks when kept at 4 °C (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

Characterizations of PLGA4-7 LPNs. (a) A representative cryo-TEM image of PLGA4-7 LPNs revealing a spherical morphology (Scale bar = 100 nm); (b) Particle size of PLGA4-7 LPNs were stable for at least 2 weeks at 4 °C.

Dose Dependency and Delivery Efficiency of PLGA4-7 LPNs in Different Cell Lines

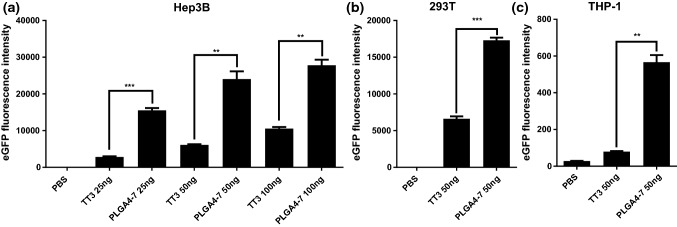

To further study the delivery capability of PLGA4-7 LPNs, a dose dependency assay was carried out. Hep3B cells were transfected with PLGA4-7 LPNs at different doses of eGFP mRNA (25, 50 or 100 ng/well). Fluorescence intensity was examined by flow cytometry after 24 h. Results showed that PLGA4-7 LPNs enabled significantly higher eGFP expression level than that of previously reported TT3-LLNs at every dose level (Fig. 7a). While eGFP expression level of TT3-LLNs increased proportionally with dose, eGFP expression of PLGA4-7 LPNs increased with dose as well but not proportionally. At lower doses, PLGA4-7 LPNs demonstrated a more significant fold increase of eGFP expression over TT3-LLNs.

Figure 7.

(a) Dose dependency of PLGA4-7 LPNs in Hep3B cells. Delivery efficiency of PLGA4-7 LPNs in HEK293T (b) and THP-1 (c) cells. (n = 3; two-tailed t-test; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

Next, two additional cell lines, 293T and THP-1, were used to examine the delivery efficiency of PLGA4-7 LPNs. We observed significantly increased mRNA delivery efficiency of PLGA4-7 LPNs in both cell lines as compared with TT3-LLNs (Figs. 7b and 7c).

Discussions and Conclusions

In summary, we incorporated a series of biodegradable and biocompatible polymer materials into TT3-LLNs to develop lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPNs). Most of hydrophobic polymer incorporated LPNs showed better transfection efficiency than TT3-LLNs and hydrophilic polymer incorporated LPNs, especially at prolonged time points. Through in vitro screenings and orthogonal optimization, an optimized LPNs formulation, PLGA4-7 LPNs, was obtained with significantly enhanced mRNA delivery efficiency and prolonged protein expression. In the optimized PLGA4-7 LPNs, polymer material PLGA4 is an acid-terminated PLGA with the molecular weight around 24,000–38,000 g/mol and viscosity of 0.32–0.44 dL/g. When incorporated into TT3-LLNs, PLGA4 showed the highest improvement of mRNA delivery efficiency as compared with TT3-LLNs and other LPNs tested. After analyzing the results, we found that PLGA4 incorporated LPNs showed slightly enhanced zeta potential and encapsulation efficiency as compared to TT3 LLNs, which may facilitate mRNA packaging by PLGA4 incorporation.2,3,24 Moreover, PLGA4 LPNs displayed significantly improved delivery efficiency at prolonged time points, which indicates that PLGA4 polymer material may enable a sustained release of mRNA from nanoparticles.3,24 Consequently, these new LPNs formulations merit further study and development for mRNA delivery and potential therapeutic applications.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgment

The cryo-TEM imaging was carried out at the Liquid Crystal Institute Characterization Facility of Kent State University.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Awards from the National PKU Alliance, New Investigator Grant from the AAPS Foundation, Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award 1R35GM119679 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences as well as the start-up fund from the College of Pharmacy at The Ohio State University.

Conflict of interest

W. Z., C. Z., B. L., X. Z., X. L., C. Z., W. L., M. G., and Y. D. declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards

No human or animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Abbreviations

- mRNA

Messenger RNA

- TT

N1,N3,N5-tris (2-aminoethyl) benzene-1, 3, 5 tricarboxamide

- LLNs

Lipid-like nanoparticles

- LPNs

Lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles

- DOPE

1,2-dioleoylsn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- DMG-PEG2000

1, 2-dimyristoyl-snglycerol, methoxypolyethylene glycol

- PLGA

Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- PLA

Poly (d,l-lactic acid)

- HA

Hyaluronic acid

Footnotes

Yizhou Dong is an Associate Professor in the College of Pharmacy at The Ohio State University. He received his B.S. from Peking University, Health Science Center (2002) and M.S. from Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry (2005). In 2009, he received his Ph.D. degree in pharmaceutical sciences from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill under the supervision of Professor K.-H. Lee. From 2010 to 2014, he was a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Professors Robert Langer and Daniel Anderson at MIT. Dr. Dong joined OSU as an Assistant Professor in 2014, and was promoted to Associate Professor in 2018. His research focuses on the design and development of biotechnology platforms for treating genetic disorders, infectious diseases, and cancers. Dr. Dong has authored over fifty papers and patents. Several of his inventions have been licensed and are currently under development as drug candidates for clinical trials. He is the recipient of numerous honors, including Early Career Investigator Award from the Bayer Hemophilia Awards Program, Research Awards from the National PKU Alliance, New Investigator Grant from the AAPS Foundation, Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and 2017 Ohio State Early Career Innovator of the Year.

This article is part of the 2018 CMBE Young Innovators special issue.

References

- 1.Amreddy N, Babu A, Muralidharan R, Munshi A, Ramesh R. Polymeric nanoparticle-mediated gene delivery for lung cancer treatment. Top. Curr. Chem. 2017;375:35. doi: 10.1007/s41061-017-0128-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball RL, Hajj KA, Vizelman J, Bajaj P, Whitehead KA. Lipid nanoparticle formulations for enhanced co-delivery of siRNA and mRNA. Nano Lett. 2018;18:3814–3822. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bose RJ, Lee S-H, Park H. Lipid-based surface engineering of plga nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery applications. Biomater. Res. 2016;20:34. doi: 10.1186/s40824-016-0081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen B, Miller RJ, Dhal PK. Hyaluronic acid-based drug conjugates: State-of-the-art and perspectives. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2014;10:4–16. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2014.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlman JE, Barnes C, Khan O, Thiriot A, Jhunjunwala S, Shaw TE, Xing Y, Sager HB, Sahay G, Speciner L, Bader A, Bogorad RL, Yin H, Racie T, Dong Y, Jiang S, Seedorf D, Dave A, Sandu KS, Webber MJ, Novobrantseva T, Ruda VM, Lytton-Jean AKR, Levins CG, Kalish B, Mudge DK, Perez M, Abezgauz L, Dutta P, Smith L, Charisse K, Kieran MW, Fitzgerald K, Nahrendorf M, Danino D, Tuder RM, von Andrian UH, Akinc A, Schroeder A, Panigrahy D, Kotelianski V, Langer R, Anderson DG. In vivo endothelial sirna delivery using polymeric nanoparticles with low molecular weight. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014;9:648–655. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danhier F, Ansorena E, Silva JM, Coco R, Breton A, Préat V. Plga-based nanoparticles: an overview of biomedical applications. J. Control. Release. 2012;161:505–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong Y, Dorkin JR, Wang W, Chang PH, Webber MJ, Tang BC, Yang J, Abutbul-Ionita I, Danino D, DeRosa F, Heartlein M, Langer R, Anderson DG. Poly(glycoamidoamine) brushes formulated nanomaterials for systemic siRNA and mRNA delivery in vivo. Nano Lett. 2016;16:842–848. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dosio F, Arpicco S, Stella B, Fattal E. Hyaluronic acid for anticancer drug and nucleic acid delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016;97:204–236. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao M, Kim Y-K, Zhang C, Borshch V, Zhou S, Park H-S, Jákli A, Lavrentovich OD, Tamba M-G, Kohlmeier A, Mehl GH, Weissflog W, Studer D, Zuber B, Gnägi H, Lin F. Direct observation of liquid crystals using cryo-tem: specimen preparation and low-dose imaging. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2014;77:754–772. doi: 10.1002/jemt.22397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan S, Rosenecker J. Nanotechnologies in delivery of mRNA therapeutics using nonviral vector-based delivery systems. Gene Ther. 2017;24:133–143. doi: 10.1038/gt.2017.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadinoto K, Sundaresan A, Cheow WS. Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles as a new generation therapeutic delivery platform: a review. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013;85:427–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hajj KA, Whitehead KA. Tools for translation: non-viral materials for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017;2:17056. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.56. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harguindey A, Domaille DW, Fairbanks BD, Wagner J, Bowman CN, Cha JN. Synthesis and assembly of click-nucleic-acid-containing PEG–PLGA nanoparticles for DNA delivery. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1700743. doi: 10.1002/adma.201700743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasan W, Chu K, Gullapalli A, Dunn SS, Enlow EM, Luft JC, Tian S, Napier ME, Pohlhaus PD, Rolland JP. Delivery of multiple siRNAs using lipid-coated PLGA nanoparticles for treatment of prostate cancer. Nano Lett. 2011;12:287–292. doi: 10.1021/nl2035354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Islam MA, Reesor EKG, Xu Y, Zope HR, Zetter BR, Shi J. Biomaterials for mRNA delivery. Biomater. Sci. 2015;3:1519–1533. doi: 10.1039/C5BM00198F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang C, Mei M, Li B, Zhu X, Zu W, Tian Y, Wang Q, Guo Y, Dong Y, Tan X. A non-viral CRISPR/Cas9 delivery system for therapeutically targeting HBV DNA and pcsk9 in vivo. Cell Res. 2017;27:440–443. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaczmarek JC, Patel AK, Kauffman KJ, Fenton OS, Webber MJ, Heartlein MW, DeRosa F, Anderson DG. Polymer-lipid nanoparticles for systemic delivery of mRNA to the lungs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016;55:13808–13812. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kranz LM, Diken M, Haas H, Kreiter S, Loquai C, Reuter KC, Meng M, Fritz D, Vascotto F, Hefesha H, Grunwitz C, Vormehr M, Husemann Y, Selmi A, Kuhn AN, Buck J, Derhovanessian E, Rae R, Attig S, Diekmann J, Jabulowsky RA, Heesch S, Hassel J, Langguth P, Grabbe S, Huber C, Tureci O, Sahin U. Systemic RNA delivery to dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2016;534:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature18300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee BK, Yun Y, Park K. PLA micro- and nano-particles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016;107:176–191. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li B, Dong Y. Preparation and optimization of lipid-like nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1632:207–217. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7138-1_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li B, Luo X, Deng B, Wang J, McComb DW, Shi Y, Gaensler KM, Tan X, Dunn AL, Kerlin BA, Dong Y. An orthogonal array optimization of lipid-like nanoparticles for mRNA delivery in vivo. Nano Lett. 2015;15:8099–8107. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b03528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li B, Zhang X, Dong Y. Nanoscale platforms for messenger rna delivery. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. 2018;6:e1530. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo X, Li B, Zhang X, Zhao W, Bratasz A, Deng B, McComb DW, Dong Y. Dual-functional lipid-like nanoparticles for delivery of mRNA and MRI contrast agents. Nanoscale. 2017;9:1575–1579. doi: 10.1039/C6NR08496F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makadia HK, Siegel SJ. Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) as biodegradable controlled drug delivery carrier. Polymers (Basel) 2011;3:1377–1397. doi: 10.3390/polym3031377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller JB, Zhang S, Kos P, Xiong H, Zhou K, Perelman SS, Zhu H, Siegwart DJ. Non-viral CRISPR/Cas gene editing in vitro and in vivo enabled by synthetic nanoparticle co-delivery of Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017;56:1059–1063. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richner JM, Himansu S, Dowd KA, Butler SL, Salazar V, Fox JM, Julander JG, Tang WW, Shresta S, Pierson TC, Ciaramella G, Diamond MS. Modified mRNA vaccines protect against zika virus infection. Cell. 2017;168:1114–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahin U, Kariko K, Tureci O. mRNA-based therapeutics–developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:759–780. doi: 10.1038/nrd4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sergeeva OV, Koteliansky VE, Zatsepin TS. mRNA-based therapeutics-advances and perspectives. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2016;81:709–722. doi: 10.1134/S0006297916070075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart MP, Lorenz A, Dahlman J, Sahay G. Challenges in carrier-mediated intracellular delivery: moving beyond endosomal barriers. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. 2016;8:465–478. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swierczewska M, Han HS, Kim K, Park JH, Lee S. Polysaccharide-based nanoparticles for theranostic nanomedicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016;99:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Griffel B, Xu X. Synthesis of PLGA-lipid hybrid nanoparticles for siRNA delivery using the emulsion method PLGA-PEG-lipid nanoparticles for siRNA delivery. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1632:231–240. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7138-1_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wroblewska L, Kitada T, Endo K, Siciliano V, Stillo B, Saito H, Weiss R. Mammalian synthetic circuits with rna binding proteins for RNA-only delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:839. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu B, Xia S, Wang F, Jin Q, Yu T, He L, Chen Y, Liu Y, Li S, Tan X, Ren K, Yao S, Zeng J, Song X. Polymeric nanomedicine for combined gene/chemotherapy elicits enhanced tumor suppression. Mol. Pharm. 2016;13:663–676. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan Y, Xiong H, Zhang X, Cheng Q, Siegwart DJ. Systemic mRNA delivery to the lungs by functional polyester-based carriers. Biomacromol. 2017;18:4307–4315. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b01356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zangi L, Lui KO, von Gise A, Ma Q, Ebina W, Ptaszek LM, Spater D, Xu H, Tabebordbar M, Gorbatov R, Sena B, Nahrendorf M, Briscoe DM, Li RA, Wagers AJ, Rossi DJ, Pu WT, Chien KR. Modified mRNA directs the fate of heart progenitor cells and induces vascular regeneration after myocardial infarction. Nat. Biotech. 2013;31:898–907. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Li B, Luo X, Zhao W, Jiang J, Zhang C, Gao M, Chen X, Dong Y. Biodegradable amino-ester nanomaterials for Cas9 mRNA delivery in vitro and in vivo. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:25481–25487. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b08163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu X, Xu Y, Solis LM, Tao W, Wang L, Behrens C, Xu X, Zhao L, Liu D, Wu J, Zhang N, Wistuba, Farokhzad OC, Zetter BR, Shi J. Long-circulating siRNA nanoparticles for validating Prohibitin1-targeted non-small cell lung cancer treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015;112:7779–7784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505629112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.