Since siderophores have been widely exploited for agricultural, environmental, and medical applications, the identification and characterization of new siderophores from different habitats and organisms will have great beneficial applications. Here, we identified a novel siderophore-producing gene cluster in C. necator JMP134. This gene cluster produces a previously unknown carboxylate siderophore, cupriabactin. Physiological analyses revealed that the cupriabactin-mediated iron acquisition system influences swimming motility, biofilm formation, and oxidative stress resistance. Most notably, this system also plays important roles in increasing the resistance of C. necator JMP134 to stress caused by aromatic compounds, which provide a promising strategy to engineer more efficient approaches to degrade aromatic pollutants.

KEYWORDS: aromatic compound degradation, biofilm, Cupriavidus necator, Fur, oxidative stress, siderophore

ABSTRACT

Many bacteria secrete siderophores to enhance iron uptake under iron-restricted conditions. In this study, we found that Cupriavidus necator JMP134, a well-known aromatic pollutant-degrading bacterium, produces an unknown carboxylate-type siderophore named cupriabactin to overcome iron limitation. Using genome mining, targeted mutagenesis, and biochemical analysis, we discovered an operon containing six open reading frames (cubA–F) in the C. necator JMP134 genome that encodes proteins required for the biosynthesis and uptake of cupriabactin. As the dominant siderophore of C. necator JMP134, cupriabactin promotes the growth of C. necator JMP134 under iron-limited conditions via enhanced ferric iron uptake. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the iron concentration-dependent expression of the cub operon is mediated by the ferric uptake regulator (Fur). Physiological analyses revealed that the cupriabactin-mediated iron acquisition system influences swimming motility, biofilm formation, and resistance to oxidative and aromatic compound stress in C. necator JMP134. In conclusion, we identified a carboxylate-type siderophore named cupriabactin, which plays important roles in iron scavenging, bacterial motility, biofilm formation, and stress resistance.

IMPORTANCE Since siderophores have been widely exploited for agricultural, environmental, and medical applications, the identification and characterization of new siderophores from different habitats and organisms will have great beneficial applications. Here, we identified a novel siderophore-producing gene cluster in C. necator JMP134. This gene cluster produces a previously unknown carboxylate siderophore, cupriabactin. Physiological analyses revealed that the cupriabactin-mediated iron acquisition system influences swimming motility, biofilm formation, and oxidative stress resistance. Most notably, this system also plays important roles in increasing the resistance of C. necator JMP134 to stress caused by aromatic compounds, which provide a promising strategy to engineer more efficient approaches to degrade aromatic pollutants.

INTRODUCTION

Iron is an essential nutrient for almost all organisms by acting as a cofactor for enzymes and regulatory proteins involved in many cellular processes (1). Although iron is the fourth most abundant element in the Earth’s crust, the bioavailability of this element is severely restricted due to its low solubility under aerobic, aqueous, and neutral-pH conditions (2–5). To adapt to iron deprivation, many bacteria have evolved sophisticated strategies to scavenge iron from the environment. The most commonly used strategy is the synthesis and secretion of siderophores, which are low-molecular-weight compounds that bind iron with high affinity in the extracellular milieu and reenter cells via specific membrane transporters (3, 6). Siderophores are classified into different types, all belonging to a few structural classes, including catecholate, phenolate, carboxylate, hydroxamate, and mixed-ligand siderophores (3). The production of siderophore is strictly regulated in an iron concentration-dependent manner with the help of transcriptional regulators, such as Fur (ferric uptake regulator) (7–9).

Cupriavidus necator JMP134 (also known as Ralstonia eutropha JMP134) is a well-known aromatic pollutant-degrading Gram-negative bacterium that belongs to the order Burkholderiales, class Betaproteobacteria. C. necator JMP134 was originally isolated in Australia from an unspecified soil sample by selection for its ability to use 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) as the sole carbon and energy source (10). The C. necator JMP134 genome contains nearly 300 genes potentially involved in the catabolism of aromatic compounds and encodes almost all the central ring cleavage pathways (11). In addition to 2,4-D, this strain can also grow in the presence of more than 60 other aromatic substrates and is a model for chloroaromatic biodegradation (12, 13).

Although not reported in C. necator JMP134 so far, several specific siderophores have been characterized in the genus Cupriavidus, as well as in the closely related genera Ralstonia and Burkholderia. The plant-pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum was reported to secrete the natural product staphyloferrin B and micacocidin as siderophores when exposed to low-iron conditions (14). Additionally, staphyloferrin B is also found in Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 (sometimes referred to as Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34) (15). Recently, the genomics-inspired discovery of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)-derived siderophore, cupriachelin, from the freshwater bacterium Cupriavidus necator H16 was reported. Cupriachelin is unusual in that it exhibits structural and physicochemical features that are typically associated with siderophores from oceanic bacteria (16). Moreover, they identified a previously unknown lipopeptide siderophore, taiwachelin, in the nitrogen-fixing bacterium Cupriavidus taiwanensis LMG19424 (17).

Given the functional diversity of siderophores and their application in different fields, it is very important to identify new siderophores (18). Here, we identified a novel siderophore-producing gene cluster in C. necator JMP134, which produces a previously unknown carboxylate siderophore, cupriabactin. Further studies revealed that cupriabactin plays important physiological roles in iron scavenging, bacterial motility, biofilm formation, and oxidative stress resistance. Moreover, the results demonstrated that cupriabactin-mediated iron acquisition activity enhanced the tolerance of C. necator JMP134 cells to various aromatic compounds.

RESULTS

Presence of a carboxylate siderophore gene cluster in the C. necator JMP134 genome.

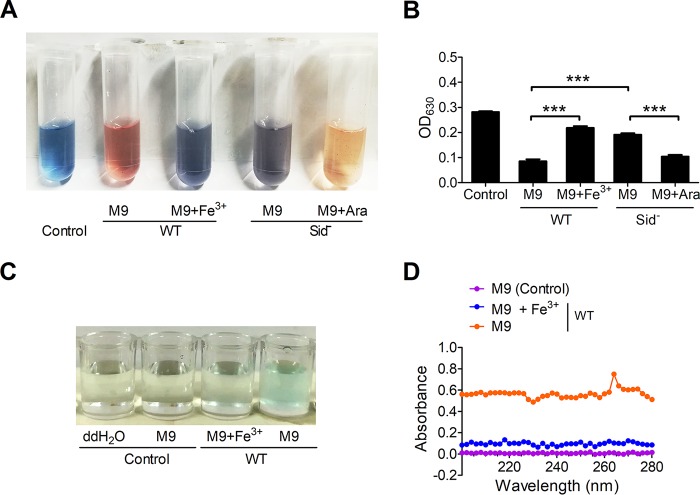

By using the liquid colorimetric chromeazurol S (CAS) test (19), C. necator JMP134 was found to produce siderophores under iron-limiting conditions, and the presence of 100 μM Fe3+ in the medium greatly reduced siderophore production (Fig. 1A and B). Consistently, the only operon encoding proteins necessary for siderophore biosynthesis was identified in the C. necator JMP134 genome by using antiSMASH, a web server to identify, annotate, and compare gene clusters that encode the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in bacterial and fungal genomes (20). To examine the role of this operon in siderophore production, we generated a Sid− mutant in which the native promoter of this putative siderophore operon was replaced by the PBAD promoter (a promoter that can be induced by arabinose). As expected, siderophore production was completely abolished in the Sid− mutant strain unless 0.2% arabinose was supplemented to the medium to induce the expression of the putative siderophore, as revealed by the CAS test (Fig. 1A and B). The result suggests that this operon is the dominant siderophore production operon in C. necator JMP134.

FIG 1.

Presence of a carboxylate siderophore in C. necator JMP134. (A and B) Detection of siderophore production in C. necator JMP134 wild type (WT) and the Sid− mutant cultured in M9 medium with or without Fe3+ (100 μM) using the CAS assay. (A) The CAS solution takes on blue, as CAS, HTDMA (hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide), and Fe(III) can form a triple FeDye3-x complex which has an adsorption at 630 nm. When siderophore removes Fe(III) from the complex, the color of the solution will turn to red or brown. Arabinose (Ara; 0.2%) was supplemented to the medium to induce the expression of the siderophore biosynthesis genes. (B) Quantification of blue FeDye3-x complex formation in panel A by determining the absorbance at 630 nm. The decreasing of absorbance indicates the production of siderophore. (C and D) Detection of carboxylate siderophore in C. necator JMP134 wild type cultured in M9 medium with or without Fe3+ (100 μM) by using the copper sulfate reagent. Siderophore can form a blue complex (C) with copper sulfate, and the absorbance was recorded at 264 nm (D). Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, each of which was performed in three technical replicates. ***, P < 0.001. ddH2O, double-distilled water.

Subsequently, we determined the siderophore type by several chemical tests. The siderophore produced by C. necator JMP134 seems to be a carboxylate-type siderophore, because it cannot react with the ferric chloride and Arnow reagents (see Fig. S1A to D in the supplemental material), which are used in the detection of hydroxamate and catecholate groups in siderophores, respectively (21, 22). Moreover, a negative reaction was also observed with the ferric chloride-ferricyanide reagent (Fig. S1E), which specifically detects phenolate groups in siderophores (23). However, this siderophore was able to form a blue complex with copper sulfate (Fig. 1C and D), which had a maximum absorption peak at 264 nm (24). The interaction of the siderophore with copper sulfate suggests that it is a carboxylate-type siderophore. We named the siderophore cupriabactin, identified in C. necator JMP 134 in this study.

Siderophore production from the cub operon in C. necator JMP134.

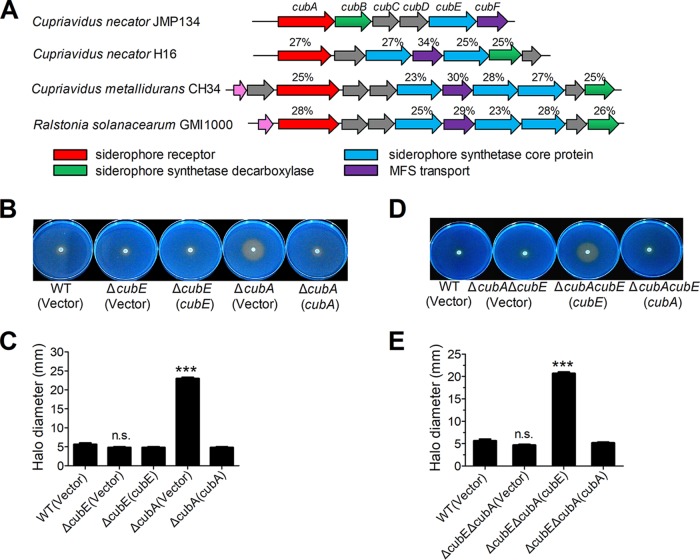

By analyzing the cupriabactin production gene cluster, we found it is similar to the staphyloferrin B biosynthesis gene cluster (Fig. 2A), a citrate siderophore, which has been identified in Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000 (14), Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 (15), and Cupriavidus necator H16 (16, 25), respectively. The cupriabactin-producing operon consists of six genes, which have been named cubA to cubF in this study (Fig. 2A). The first gene of the cub operon, cubA (reut_B3686), encodes a putative TonB-dependent siderophore receptor that is essential for the transport of ferric-siderophore complexes across the outer membrane (26). The CubA protein shares 43% and 25% amino acid sequence identities with the identified TonB-dependent siderophore receptors IutA in Escherichia coli (27) and AleB in Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 (15), respectively. The gene cubE (reut_B3682) encodes an IucA ortholog that shares homology with the E. coli IucA (GenBank accession no. CAA53707; 26% identity). In E. coli, IucA was identified as a siderophore synthetase core protein implicated in the aerobactin siderophore biosynthesis from N-hydroxylysine and citrate precursors (28). Downstream of cubA, putative cupriabactin biosynthesis genes cubB (reut_B3685), cubC (reut_B3684), cubD (reut_B3683), and cubF (reut_B3681) are present, which encode decarboxylase, pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent enzyme, dehydrogenase, and major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transport proteins, respectively.

FIG 2.

Siderophore production from the cub operon. (A) Comparison of the cupriabactin biosynthesis genes from C. necator JMP134 with the staphyloferrin B biosynthesis-related genes from indicated strains. Numbers above each ORF indicate the amino acid identity (expressed as a percentage) to the corresponding ORF of C. necator JMP134. The GenBank accession numbers are as follows: Cupriavidus pinatubonensis JMP134, AAZ63039.1 to AAZ63041.1; Cupriavidus necator H16, AAP85873.1 to AAP85879.1; Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34, ABF07996.1 to ABF08006.1; and Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000, CAD17566.1 to CAD17575.1. (B and C) Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition requires cubE and cubA. (B) The production of siderophore was detected using colorimetric CAS agar plates. For each strain, stationary-phase strains were taken from a single colony grown on nutrient agar, spotted onto the middle of the CAS plates, and photographed after incubation for 5 days at 30°C. (C) The diameter of the halo of color change was measured at its widest point from the edge of colony growth. The graph represents the mean halo diameter from three individual plates for each strain. (D and E) Comparison of the colored halos around C. necator JMP134 wild type, ΔcubE ΔcubA double mutant, and ΔcubE ΔcubA double mutant strains complemented with cubE or cubA, respectively. (E) The graph represents the mean halo diameter from three individual plates for each strain. The vector stands for the pBBR1MCS-2 plasmid. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, each of which was performed with three technical replicates. ***, P < 0.001; n.s., not significant.

Next, we created cubA and the key siderophore biosynthesis gene cubE deletion mutants to assess their roles in siderophore production and uptake, using the CAS plate assay according to the method of Schwyn and Neilands (19). Compared with the wild type, siderophore production of the ΔcubE mutant slightly decreased, and the mean halo diameter shrank from 5.67 ± 0.67 mm to 4.83 ± 0.33 mm, whereas the ΔcubA mutant had a conspicuous orange halo with a mean diameter of 23 ± 0.50 mm (Fig. 2B and C). The significant increase in siderophore production in the ΔcubA mutant may result from continually producing and secreting siderophores while failing to transport the ferric-siderophore complexes back into the cell (29). Consistent with this hypothesis, complementation of the cubA gene with the pBBR1MCS-2-cubA plasmid reduced the halo diameter to the wild-type level. Moreover, the ΔcubA ΔcubE double mutant failed to phenocopy the impressive orange halo produced by the ΔcubA mutant (Fig. 2D and E), suggesting that the cubE gene is essential for cupriabactin production in the ΔcubA mutant. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the cub operon encodes proteins necessary for cupriabactin biosynthesis and transport in C. necator JMP134.

Fur negatively regulates cub operon expression in C. necator JMP134.

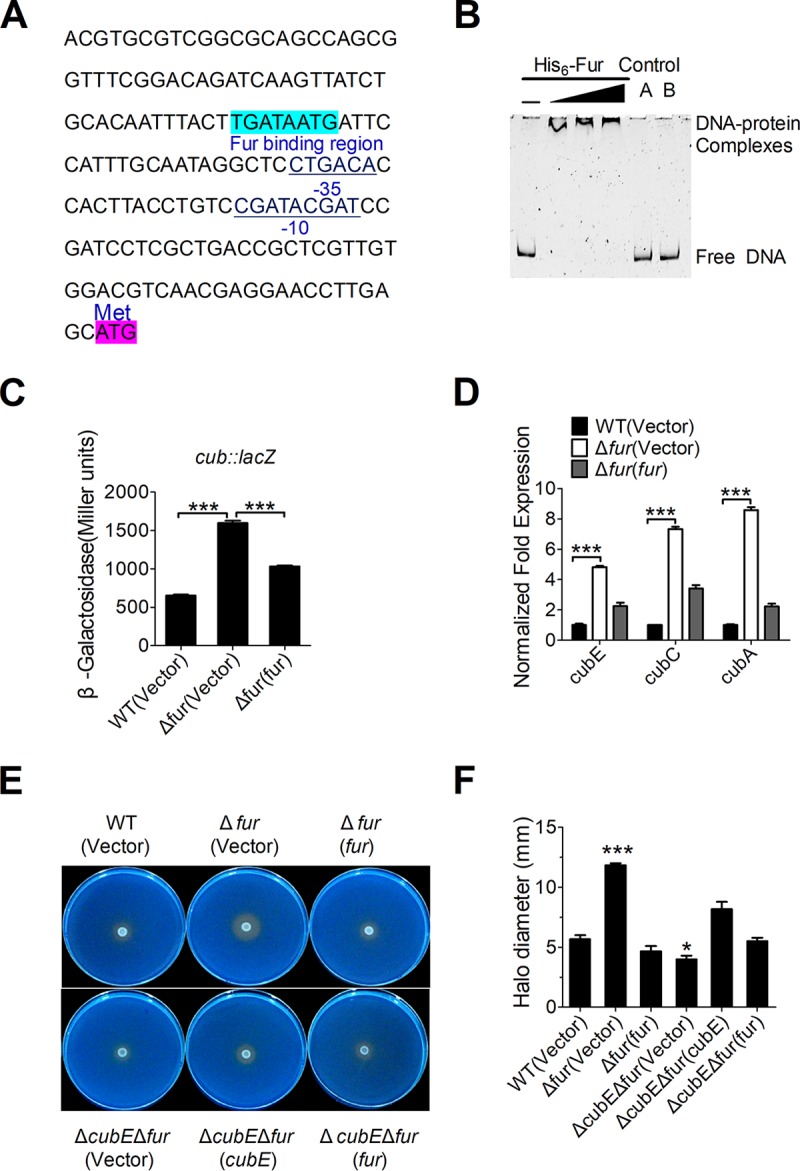

The reasons for low siderophore production by the C. necator JMP134 wild-type strain and the absence of a significant difference in siderophore production between the wild-type and ΔcubE mutant were unclear. A reasonable explanation is that the expression of cub in the wild-type strain was repressed by a specific repressor. It has been reported that the siderophore operons are directly regulated by the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) (30). Interestingly, analysis of the C. necator JMP134 cub promoter also revealed a putative Fur-binding site (Fig. 3A). This Fur-binding site (TGATAATG) is highly similar to the fur box identified in E. coli (31) (Fig. S2). Incubation of the cub promoter probe (Pcub, −73 to −147 bp, relative to the ATG start codon of the first open reading frame [ORF] of the cub operon) with His6-Fur led to retarded mobility of the probe in the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), indicating a direct interaction between the cub promoter and Fur. The interaction is specific, as a 75-bp control DNA did not show detectable Fur binding (Fig. 3B). Thus, Fur specifically recognizes an operator within the cub promoter, most likely influencing its activity.

FIG 3.

Fur negatively regulates cub expression. (A) Identification of a Fur-binding site in the promoter region of cub. The putative Fur-binding site identified by the online software Virtual Footprint is indicated by blue highlighting. The ATG start codon of the first ORF of the cub operon is shown. Putative −35 and −10 elements of the cub promoter are underlined. (B) EMSA was performed to analyze the interactions between His6-Fur and the promoter. Increasing amounts of Fur (0.38, 0.76, and 1.14 μM) and 0 to 1 nM the DNA fragment were used. As negative controls, a 75-bp unrelated DNA fragment (control A) and 1.14 μM BSA (control B) were included in this assay. (C) Fur represses the expression of cub. β-Galactosidase analyses of cub promoter activities were performed using the transcriptional Pcub::lacZ chromosomal fusion reporter expressed in the C. necator JMP134 wild-type, Δfur mutant, and complemented Δfur(fur) strains grown to stationary phase in NB medium. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of cub. Cells of relevant C. necator JMP134 strains were grown to mid-exponential phase in NB medium, and the expression of cubE, cubC, and cubA (the main components of cub) were measured by qRT-PCR. (E and F) Siderophore production is negatively regulated by Fur. (E) The production of siderophore was detected using colorimetric CAS agar plates to compare the colored halos around wild-type, Δfur mutant, the complemented Δfur(fur) mutant, ΔcubE Δfur double mutants, and the complemented ΔcubE Δfur(cubE) and ΔcubE Δfur(fur) mutants. (F) The graph represents the mean halo diameter from three individual plates for each strain after incubation for 5 days at 30°C. Vector stands for pBBR1MCS-5 (C) and pBBR1MCS-2 (D to F). Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, each of which was performed in three technical replicates. ***, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05.

To verify the role of Fur in the regulation of the cub operon, a single-copy Pcub::lacZ fusion reporter was introduced into the chromosomes of the wild-type, Δfur mutant, and complemented Δfur(fur) strains. The LacZ activity of the resulting strains was quantitatively measured (Fig. 3C). Compared to that in the wild-type strain, Pcub::lacZ activity was significantly increased in the Δfur mutant, and this increase could be fully restored to the wild-type level by introducing the complementary plasmid pBBR1MCS-5-fur, confirming that Fur negatively regulates cub expression. This difference is not attributed to the growth defect between wild-type and fur mutant strains, as they showed equal growth rates in Nutrient broth (NB) (Fig. S3A) and M9 (Fig. S3C) media. Negative regulation of the cub operon by Fur was further confirmed using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis, which indicated that the expression levels of cubA, cubC, and cubE were significantly increased in the Δfur mutant, and that such increases could be completely reversed by fur complementation (Fig. 3D).

The negative regulation of the cub operon by Fur was also confirmed at the siderophore production level. Compared with the wild-type and fur complemented strains, the Δfur mutant showed a significant increase in siderophore production on CAS plates, a phenotype consistent with the loss of repression of the siderophore biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 3E and F). However, further deletion of cubE abrogated the increase in siderophore production in the Δfur mutant, suggesting that the cub system is the major siderophore-producing system repressed by Fur in C. necator JMP134. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the cub operon is negatively and specifically regulated by Fur in C. necator JMP134.

Fur-mediated expression of cub responds to the intracellular iron concentration.

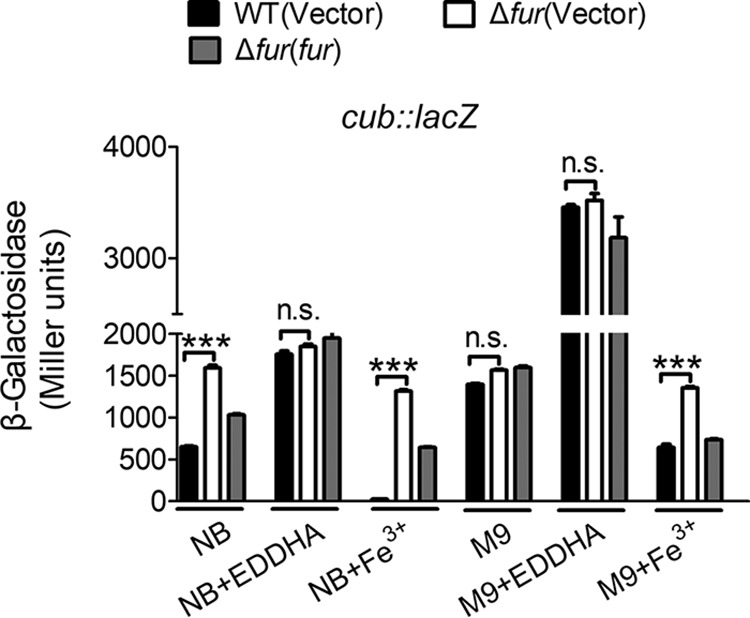

As discussed above, cub expression is negatively regulated by Fur. To determine whether such negative regulation responds to iron concentration, we investigated the expression of cub in C. necator JMP134 wild type by chromosomal Pcub::lacZ fusion reporter analysis at different iron concentrations. As shown in Fig. 4, the expression of cub was repressed in the iron-rich NB medium. The expression of cub was significantly induced by the addition of the specific iron chelator EDDHA [ethylenediamine-N,N′-bis(2-hydroxyphenylacetic acid)] but completely repressed by the addition of excessive Fe3+ to the NB medium. Similarly, the expression of cub was activated in the iron-limited M9 medium but repressed by supplementation of Fe3+. Surprisingly, the promoter activity of cub dramatically increased in M9 medium containing EDDHA (Fig. 4). These data suggest that the expression of the cub operon responds to iron concentration.

FIG 4.

Fur-mediated expression of cub responds to different iron concentrations. Relevant C. necator JMP134 wild-type, Δfur mutant, and the complemented Δfur(fur) mutant harboring Pcub::lacZ were grown in NB medium with 2.0 μM EDDHA and 20 μM Fe3+ and in M9 medium with 2.0 μM EDDHA and 20 μM Fe3+, and the expression of the reporter in each strain was measured. The vector stands for the pBBR1MCS-5 plasmid. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, each of which was performed in three technical replicates. ***, P < 0.001; n.s., not significant.

Next, we compared the expression of cub between the wild type and the Δfur mutant by using the same method. No expression difference was found to exist between these strains under iron-limited conditions (Fig. 4). However, under iron-rich conditions, the Δfur mutant showed a significantly increased promoter activity compared to the wild-type, and introducing a plasmid expressing fur (pBBR1MCS-5-fur) restored the promoter activity to the wild-type level, indicating that the iron-dependent expression of cub is mediated by Fur. These expression differences observed between the wild type and Δfur mutant are not attributed to a decrease in growth rate, since 2.0 μM EDDHA did not influence bacterial growth (Fig. S3B and D). These results suggest that the iron concentration-dependent expression of the cub operon is mediated by Fur.

The siderophore produced by the cub operon is crucial for iron acquisition in C. necator JMP134.

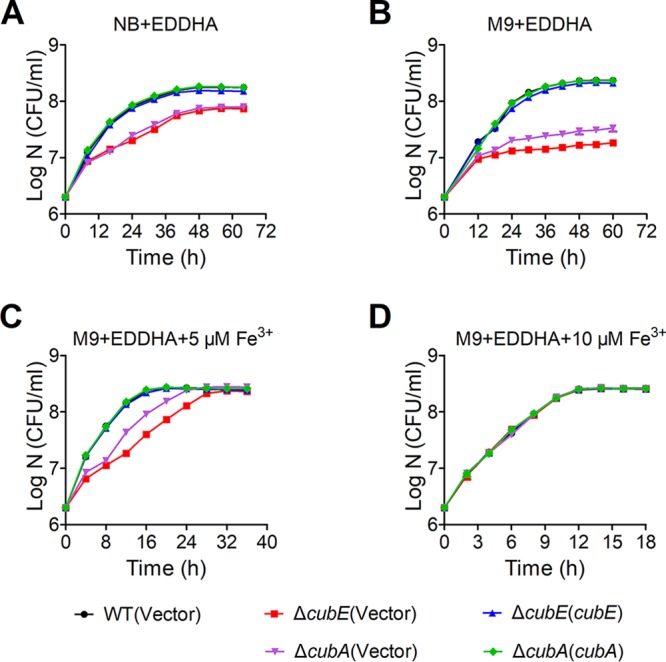

Most bacteria require 10−6 to 10−7 M levels of bioavailable iron for optimal growth (32). To investigate the role of the cub siderophore-producing system in bacterial growth, we examined the growth curves of C. necator JMP134 wild type and ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants under iron-limited conditions by adding EDDHA. Whereas ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants showed growth rates equal to that of the wild-type strain in NB and M9 media (Fig. S3E and F), their growth rates appeared to be severely influenced when 5 μM EDDHA was added to the NB medium (Fig. 5A). Similarly, the growth of the ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants was dramatically reduced by the addition of 5 μM EDDHA to M9 medium (Fig. 5B). However, the growth defect of the ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants could be restored by introducing a plasmid expressing cubE and cubA, respectively, or by supplying 5 μM or 10 μM Fe3+ to M9 medium containing 5 μM EDDHA (Fig. 5C and D).

FIG 5.

Growth curves of relevant C. necator JMP134 strains in NB and iron-limiting media at 30°C. (A to D) Relevant C. necator JMP134 wild-type, ΔcubE mutant, the complemented ΔcubE(cubE) mutant, ΔcubA mutant, and the complemented ΔcubA(cubA) mutant strains grown overnight in 3 ml of NB medium were harvested, washed, resuspended in M9 medium, and diluted 1:500 in fresh NB medium with 5 μM EDDHA (A), M9 medium with 5 μM EDDHA (B), M9 medium with 5 μM EDDHA and 5 μM Fe3+ (C), and M9 medium with 5 μM EDDHA and 10 μM Fe3+ (D). The growth of the cultures was monitored by measuring the OD600 at the indicated time points. IPTG (1 mM) was included in the medium for induction. Vector stands for the pBBR1MCS-2 plasmid. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, each of which was performed in three technical replicates.

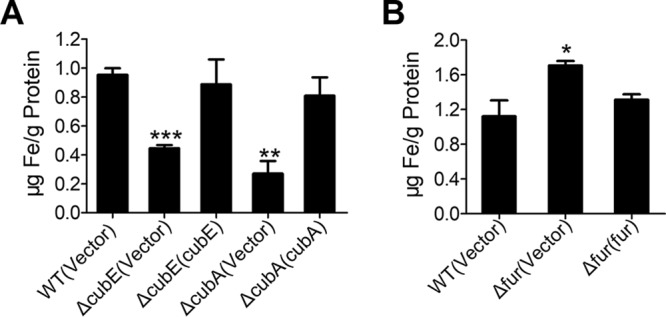

The role of the ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants in iron acquisition was further corroborated by directly determining the intracellular iron concentration by atomic absorption spectroscopy (33). The results showed that the ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants had low capacity for iron acquisition compared to the wild-type and complemented strains (Fig. 6A). Additionally, the Δfur mutant accumulated more intracellular iron than the wild-type and Δfur(fur) complemented strains (Fig. 6B). Notably, the intracellular concentrations of other detected ions (Na+, Mg2+, and Ca2+) were not affected (Fig. S4). Taken together, these results indicate that the cupriabactin-producing system plays a key role in helping bacteria obtain iron for growth under iron-limited conditions.

FIG 6.

Cupriabactin is involved in iron acquisition. (A) Iron uptake requires cupriabactin. Relevant C. necator JMP134 wild-type, ΔcubE mutant, the complemented ΔcubE(cubE) mutant, ΔcubA mutant, and the complemented ΔcubA(cubA) mutant were grown overnight in M9 medium, which was incubated to the end of logarithmic phase, harvested, and washed, and the intracellular iron associated with bacterial cells was measured by atomic absorption spectroscopy. (B) The Δfur mutant accumulates intracellular iron. Intracellular iron was measured in the C. necator JMP134 wild-type, Δfur mutant, and complemented Δfur(fur) mutant strains grown to the end of logarithmic phase in NB medium. The vector stands for the pBBR1MCS-2 plasmid. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, each of which was performed in three technical replicates. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Cupriabactin-mediated iron acquisition influences swimming motility and biofilm formation.

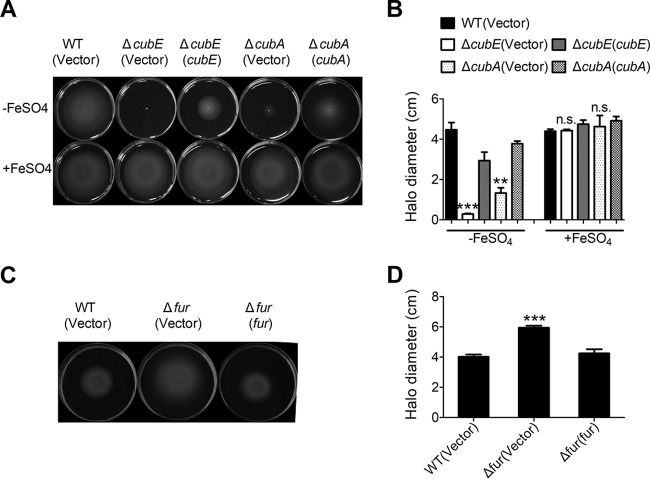

It was reported previously that bacterial motility can be influenced by intracellular iron levels (29). To investigate whether the motility of C. necator JMP134 can be affected by intracellular iron levels, we tested the swimming motility of C. necator JMP134 in different iron levels. The result clearly showed that the swimming motility of wild type on swimming medium containing 0.3% agar was severely reduced when EDDHA was supplemented to the medium (Fig. S5). This concentration of EDDHA used did not reduce the growth rate of the wild type in swimming medium, indicating that the defect in motility cannot be attributed to a decreased growth rate. To further investigate whether the cupriabactin-producing system influences the swimming motility of C. necator JMP134, we determined the swimming motility of the wild-type and ΔcubE, and ΔcubA mutant strains on swimming plates. While the wild-type strain migrated normally, the ΔcubA mutant showed markedly reduced motility, and the ΔcubE mutant was completely nonmotile and was retained in the center of the plate (Fig. 7A and B). Both the ΔcubE(cubE) and ΔcubA(cubA) complemented strains showed partially restored swimming motility (Fig. 7A and B). The deficiency in swimming motility is not due to a growth defect because both siderophore mutants had a growth rate equal to that of the wild type in NB and M9 media (Fig. S3E and F). Moreover, when the swimming motility medium was supplemented with 20 μM FeSO4, a readily available source of iron, motility was restored in both ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants (Fig. 7A and B). We also compared the swimming motility of the wild-type, Δfur mutant, and complemented strain Δfur(fur) strains. Stronger swimming motility was observed for the Δfur mutant, which produces more siderophore (Fig. 7C and D). Altogether, these data demonstrate that available iron is crucial for induction of the swimming behavior and that this process is dependent on the cub siderophore-producing system-mediated iron acquisition pathway; however, it can be overridden when sufficient bioavailable iron is supplied.

FIG 7.

Swimming motility is influenced by intracellular iron. (A and B). Iron supplementation restores motility in the ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants. A single colony of indicated C. necator JMP134 strains was touched slightly on swimming medium with or without 20 μM FeSO4. Photographs were taken (A), and halo diameters around the colonies were measured after 32 h of incubation at 30°C (B). Experiments were performed with at least three biological replicates in five technical replicates each. (C and D) Fur regulation influences surface motility. Motility of the C. necator wild-type, Δfur mutant, the complemented Δfur(fur) mutant strains is shown on swimming plates. Photographs were taken (C), and halo diameters around the colonies were measured after 16 h of incubation at 30°C (D). Experiments were conducted in at least three biological replicates in five technical replicates each. The vector stands for the pBBR1MCS-2 plasmid. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, each of which was performed in five technical replicates. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant.

Because the ability to become motile or translocate across a semisolid surface is an early and essential aspect of biofilm formation (34), we further determined the effects of the cub siderophore-producing system on biofilm formation with the crystal violet biofilm assay (35). No significant differences in biofilm formation were registered among wild-type and siderophore mutant strains in the NB medium; however, differences appeared when 2.0 μM EDDHA was supplemented to the NB medium (Fig. 8A and B). As the siderophore mutants did not show a growth defect at 30°C in NB (Fig. S3E) or NB supplied with 2.0 μM EDDHA, this suggests that the effect on biofilm formation was not due to an altered growth phenotype. Complementation with cubE or cubA increased biofilm formation to near-wild-type levels (Fig. 8A and B). These results reveal that the cupriabactin-mediated iron acquisition system influences swimming motility and biofilm formation in C. necator JMP134.

FIG 8.

Effect of cupriabactin on biofilm formation in iron-limiting media. (A and B) Overnight bacterial cultures were diluted 100-fold in fresh NB medium containing 1 mM IPTG and 50 µg ml−1 kanamycin, in the absence and presence of 2.0 μM EDDHA. After vertical incubation for 5 days with shaking at 140 rpm in 30°C, biofilm formation of the strains were determined by crystal violet staining (A) and quantified using optical density measurement (B). The vector stands for the pBBR1MCS-2 plasmid. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, each in three technical replicates. ***, P < 0.001; n.s., not significant.

Cupriabactin-mediated iron acquisition contributes to resistance to oxidative stress and aromatic compound toxicity.

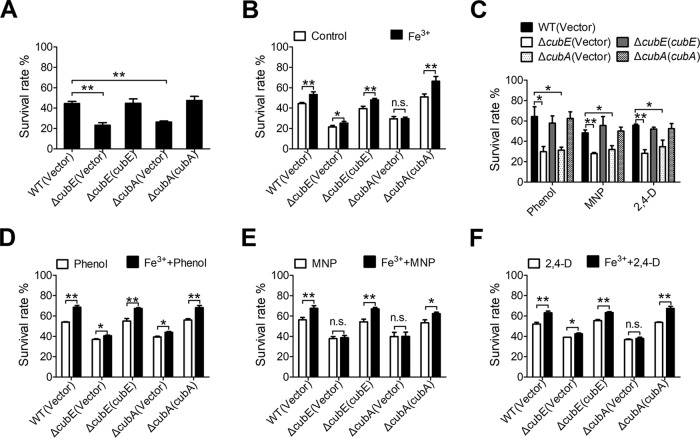

Siderophores can function as cytoprotective antioxidants by limiting the generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals produced via the Fenton reaction (36). Additionally, it has been reported that staphyloferrin B can increase resistance to oxidative stress (37). To investigate the effect of the cupriabactin-producing system in the resistance to oxidative stress, we compared the viability of ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants with that of the wild-type strain following exposure to H2O2 for 25 min (Fig. 9A). Both mutants showed much lower survival rates than the wild type after the H2O2 challenge, and the defects were restored to the wild-type level by complementation of the cubE and cubA genes (Fig. 9A). These data indicate that the cub siderophore-producing system contributes to the survival of C. necator JMP134 cells under oxidative stress conditions.

FIG 9.

Cupriabactin-mediated active iron acquisition contributes to stress resistance. (A) Alleviation of the sensitivity of C. necator JMP134 strains to H2O2 required the CubE and CubA proteins. The viability of mid-exponential-phase C. necator JMP134 strains was determined after exposure to H2O2 for 25 min. (B) Alleviation of the sensitivity of C. necator JMP134 strains to H2O2 by exogenous Fe3+ (1.5 μM). Indicated bacterial strains grown to mid-exponential phase were exposed to H2O2 with 1.5 μM Fe3+ for 25 min, and the viability of the cells was determined. (C) Alleviation of the sensitivity of C. necator JMP134 strains to phenol, MNP, and 2,4-D required the CubE and CubA proteins. Indicated bacterial strains grown to mid-exponential phase were exposed to phenol (30 mM), MNP (3 mM), or 2,4-D (20 mM) for 25 min, and the viability of the cells was determined. (D to F) Alleviation of the sensitivity of C. necator JMP134 strains to phenol, MNP and 2,4-D by exogenous Fe3+ (1.5 μM). Indicated bacterial strains grown to mid-exponential phase were exposed to phenol (D), MNP (E), or 2,4-D (F) with 1.5 μM Fe3+ for 25 min, and the viability of the cells was determined. The vector stands for the pBBR1MCS-2 plasmid. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, each of which was performed in three technical replicates. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; n.s., not significant.

To determine whether the resistance to oxidative stress is related to intracellular iron, a low concentration of Fe3+ was supplied during H2O2 treatment. Impressively, the survival rate of the wild-type strain significantly increased when supplied with iron, while that of both siderophore mutants remained unchanged or changed slightly (Fig. 9B). Complementation with cubE and cubA genes restored their survival rates to the wild-type level (Fig. 9B). Thus, in the presence of oxidative stress, a low concentration of iron can improve the viability of bacteria, indicating that ferric iron is an effective ion for bacteria to respond to oxidative stress and that the siderophore-mediated iron acquisition is important for bacteria to combat oxidative stress.

A significant number of aromatic compounds are toxic and resistant to biodegradation as a consequence of their chemical stability (38, 39). Although many organisms can use aromatic compounds as sole carbon and energy sources, these can also jeopardize bacteria when at high concentration and even cause death. C. necator JMP134 is well known for its ability to degrade many substituted aromatic pollutants. To investigate the role of the cub siderophore-producing system in the tolerance to aromatic compound toxicity, we determined the survival rates of C. necator JMP134 wild-type and ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutant strains treated with three representative aromatic compounds, phenol (30 mM), meta-nitrophenol (MNP; 3 mM), and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D, 20 mM), respectively. As shown in Fig. 9C, ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants showed markedly lower survival rates than with those of the wild-type and complemented strains for all three aromatic compounds (Fig. 9C). Consistently, supplementation with Fe3+ at a low concentration (1.5 μM) significantly increased the survival rate of the wild-type strain under aromatic compound stress but failed to enhance the survival rates of the ΔcubE and ΔcubA mutants, unless the corresponding cubE or cubA was complemented (Fig. 9D to F). These results demonstrate that the cupriabactin-mediated active iron acquisition pathway enhances bacterial resistance to oxidative and aromatic compound stress.

DISCUSSION

C. necator JMP134 is a nonpathogenic soil bacterium able to degrade a vast number of substituted aromatic pollutants. Here, we report the identification of cupriabactin, a novel carboxylate siderophore-producing gene cluster in C. necator JMP134. The cupriabactin-producing gene cluster is structurally similar to the staphyloferrin B biosynthesis gene cluster, which has been identified in some Ralstonia species (14, 15, 25). However, there still are some differences in gene composition (Fig. 2A). The cub cluster consists of six genes, while the staphyloferrin B biosynthesis gene cluster in Cupriavidus necator H16 contains seven genes, the one in Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000 contains 10 genes, and the one in Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 contains 11 genes (Fig. 2A). Also, the cub operon in C. necator JMP134 has only one iucA ortholog, while other strains have more than one iucA ortholog in their staphyloferrin B biosynthesis gene clusters. Thus, cupriabactin may represent a novel siderophore with unique functions.

Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition process has been linked to motility. In Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli K-12, genes involved in siderophore-mediated iron uptake and iron metabolism were upregulated during the initiation of swarming motility (1). Similarly, Pseudomonas putida siderophore biosynthetic and receptor gene mutants were compromised in surface motility (40). In the present study, we determined bacterial swimming motility and found that C. necator JMP134 was less motile when it was either deprived of iron or defective in the ability to actively uptake iron, indicating that motility is positively regulated by iron. Additionally, we found that the intracellular iron concentration can be influenced by the siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Swimming motility is an early and essential aspect of biofilm formation (34). Through determining the biofilm formation of C. necator JMP134, we further revealed a link between cupriabactin and biofilm formation (Fig. 8A and B). Similarly, the pyoverdine-mediated iron uptake in P. aeruginosa was reported to contribute to biofilm formation (41). Furthermore, a recent study showed that iron regulates the expression of alginate, a main exopolysaccharide of mucoid P. aeruginosa (42). However, the mechanisms by which siderophore control motility and biofilm development remain unclear.

Iron has been implicated in many oxidative stress-related pathways and conditions and is a primary cause of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation via Fenton reactions (43–45). Therefore, it is not surprising that siderophores may play a role in oxidative stress resistance. For example, E. coli enterobactin was observed to play an important role in mitigating the deleterious effects of oxidative stress, and the catecholate moieties of the siderophore are proposed to scavenge radicals (46). In Staphylococcus aureus, two citrate-based siderophores, staphyloferrin A and staphyloferrin B, were also reported to confer enhanced resistance to oxidative stress (37). In addition, salmochelins, a series of glucosylated enterobactin derivatives, protect Salmonella spp. from the oxidative stress encountered upon entering the macrophage (1). Consistent with these reports, we observed that the cupriabactin-mediated iron acquisition contributes to the resistance to oxidative stress in C. necator JMP134. As shown in Fig. 9B, a low concentration of iron can increase the survival rate of the C. necator JMP134 wild-type strain. Iron plays an irreplaceable role as a cofactor for more than 100 enzymes and many functional proteins (1). Catalases are important antioxidant enzymes that catalyze the dismutation of hydrogen peroxide to oxygen and water (47). Interestingly, the expression of catalase was significantly increased in response to iron in C. necator JMP134 (Fig. S6). Thus, we speculate that cupriabactin protects bacterial cells from oxidative stress by improving the activities of catalase and possibly other iron-dependent antioxidant enzymes. Although intracellular iron is necessary for activity of antioxidant enzymes, increased intracellular iron can directly increase oxidative stress in the cell via Fenton chemistry. In line with this idea, while cupriabactin protected C. necator JMP134 wild-type cells from oxidative stress under low iron concentrations (1 to 10 μM), its protection effect diminished under high iron concentrations (20 μM) (Fig. S7). However, whether cupriabactin plays a role in scavenging ROS, like enterobactin (46), still needs further investigation.

It is well established in literature that aromatic compounds are not easily biodegradable due to their chemical stability (48). They can even inhibit the growth of bacteria in higher concentrations. Interestingly, we revealed that cupriabactin plays important roles in resistance to aromatic compound toxicity (Fig. 9C). Since many enzymes involved in aromatic compound degradation need Fe2+ as their active center, cupriabactin may alleviate the toxicity of aromatic compounds by enhancing the activity of these iron-dependent degradation enzymes via importing adequate iron into the cytosol. For example, the ring cleavage enzyme catechol 1,2-dioxygenase is highly dependent on ferro and ferri ions (49). MnpC, the enzyme catalyzing the ring cleavage of hydroquinone to 4-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde, is also a Fe2+-dependent dioxygenase, which exhibits high specific activity against meta-nitrophenol (50). Another protective role of cupriabactin against aromatic compound toxicity is correlated with its ability to increase resistance to oxidative stress. Actually, much research has presented that the exposure of bacteria to aromatic compounds causes the formation of ROS and subsequently leads to oxidative stress (51). Therefore, the study of cupriabactin could be important in the optimization of bioremediation processes based on the resistance to aromatic compounds.

In conclusion, in this study, we revealed the function of cupriabactin in iron acquisition and aromatic compound degradation. Our results not only improved the knowledge on the physiological roles of siderophores but also provided a promising strategy to engineer efficient aromatic compound degraders in the future. However, it is worth noting that although interfering with iron homeostasis affects many traits, it does not necessarily mean that there is a direct regulatory link between siderophores and the trait in question. The physiological effect of cupriabactin could also be indirect, being mediated via many intermediate steps in the regulatory network.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with appropriate antibiotics at 37°C. C. necator JMP134 strains were grown in Nutrient broth or M9 minimal medium (Na2HPO4, 6 g liter−1; KH2PO4, 3 g liter−1; NaCl, 0.5 g liter−1; NH4Cl, 1 g liter−1; MgSO4, 1 mM; CaCl2, 0.1 mM; succinic acid, 20 mM [pH 7.0]) at 30°C with appropriate antibiotics when necessary. All chemicals were of analytical reagent-grade purity or higher. Antibiotics were added at the concentrations of kanamycin, 50 μg ml−1 and gentamicin, 10 μg ml−1; and for inducing, proper isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and arabinose were used.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| S17-1λpir | λ-pir lysogen of S17-1, thi pro hsdR hsdM+ recA RP4 -Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 | 61 |

| BL21(DE3) | Host for expression vector pET28a | Novagen |

| DH5α | FΦ80ΔlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 | Novagen |

| C. necator | ||

| JMP134 | Wild-type Cupriavidus necator JMP134 | DSMZ |

| Sid̄ mutant | Pcub was substituted with PBAD | This study |

| ΔcubE mutant | cubE gene deleted in C. necator JMP134 | This study |

| ΔcubA mutant | cubA gene deleted in C. necator JMP134 | This study |

| Δfur mutant | fur gene deleted in C. necator JMP134 | This study |

| ΔcubE(cubE) mutant | ΔcubE containing pBBR1MCS-2-cubE, Kmr | This study |

| ΔcubA(cubA) mutant | ΔcubA containing pBBR1MCS-2-cubA, Kmr | This study |

| ΔcubE ΔcubA mutant | cubE and cubA genes deleted in C. necator JMP134 | This study |

| ΔcubE ΔcubA(cubE) mutant | ΔcubE ΔcubA containing pBBR1MCS-2-cubE, Kmr | This study |

| ΔcubE ΔcubA(cubA) mutant | ΔcubE ΔcubA containing pBBR1MCS-2-cubA, Kmr | This study |

| ΔcubE Δfur mutant | cubE and fur genes deleted in C. necator JMP134 | This study |

| ΔcubE Δfur(cubE) mutant | ΔcubE Δfur containing pBBR1MCS-2-cubE, Kmr | This study |

| ΔcubE Δfur(fur) mutant | ΔcubE Δfur containing pBBR1MCS-2-fur, Kmr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pK18mobsacB | sacB-based gene replacement vector, Kmr | 62 |

| pK18-PBAD | Replacement of cub promoter to generate Sid¯ | This study |

| pK18-ΔcubE | Construct used for in-frame deletion of cubE, Kmr | This study |

| pK18-ΔcubA | Construct used for in-frame deletion of cubA, Kmr | This study |

| pK18-Δfur | Construct used for in-frame deletion of fur, Kmr | This study |

| pK18-lacZY | Construct used for promoter fusion, Kmr | This study |

| pK18-Pcub::lacZY | For cub promoter fusion to C. necator JMP134, Kmr | This study |

| pK18-PkatG::lacZY | For katG promoter fusion to C. necator JMP134, Kmr | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Broad-host-range vector, Kmr | 63 |

| pBBR1MCS-5 | Broad-host-range vector, Gmr | 63 |

| pBBR1MCS-2-cubE | cubE under the control of kanamycin resistance gene promoter in plasmid pBBR1MCS-2, Kmr | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-2-cubA | cubA under the control of kanamycin resistance gene promoter in plasmid pBBR1MCS-2, Kmr | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-2-fur | fur under the control of kanamycin resistance gene promoter in plasmid pBBR1MCS-2, Kmr | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-5-fur | fur under the control of kanamycin resistance gene promoter in plasmid pBBR1MCS-5, Gmr | This study |

| pET28a | Expression vector with N-terminal hexahistidine affinity tag, Kmr | Novagen |

| pET28a-fur | pET28a carrying fur coding region, Kmr | This study |

Kmr and Gmr represent resistance to kanamycin and gentamicin at 50 and 10 μg ml−1, respectively.

Plasmid construction.

The primers used in this study are listed in Table 2. Plasmid pK18-ΔcubE (reut_B3682) was used to construct the ΔcubE in-frame deletion mutant of C. necator JMP134. An 852-bp upstream fragment and an 835-bp downstream fragment of cubE were amplified by using the cubE-1F-HindIII/cubE-1R and cubE-2F/cubE-2R-XhoI primer pairs, respectively. The upstream and downstream PCR fragments were ligated by overlapping PCR (52). The resulting PCR products were digested with HindIII and XhoI and inserted into the HindIII/XhoI sites of pK18mobsacB to produce pK18-ΔcubE. To construct the promoter replacement plasmid pK18-PBAD, a 417-bp upstream fragment of cub promoter, a 412-bp downstream fragment of the cub promoter, and the PBAD promoter were amplified by using the primer pairs SPR-1F-EcoRI/SPR-1R, SPR-2F/SPR-2R-SalI, and PBAD-F/PBAD-R, respectively. These three fragments were ligated together by overlapping PCR referred to above. The resulting PCR products were digested with EcoRI and SalI and inserted into the EcoRI/SalI sites of pK18mobsacB to produce pK18-PBAD. The knockout plasmids pK18-ΔcubA (reut_B3686) and pK18-Δfur (reut_A2837) were constructed in similar manner by using the primers listed in Table 2. To complement the ΔcubE mutant, primers cubE-F-HindIII/cubE-R-BglII were used to amplify the cubE gene from C. necator JMP134 genomic DNA. The PCR product of cubE was digested with HindIII/BglII and inserted into the HindIII/BamHI sites of pBBR1MCS-2 to produce pBBR1MCS-2-cubE. The complementary plasmids pBBR1MCS-2-cubA, pBBR1MCS-2-fur, and pBBR1MCS-5-fur were constructed in a similar manner using the primers listed in Table 2. To express His6-tagged Fur, plasmid pET28a-fur was constructed. Briefly, primers fur-F-BamHI and fur-R-SalI were used to amplify the fur gene fragment from the C. necator JMP134 genomic DNA. The PCR products of fur were digested with BamHI/SalI and inserted into the BamHI/SalI sites of pET28a to generate pET28a-fur. The lacZY fusion reporter pK18-Pcub::lacZY was constructed by using primers lacZY-F-XbaI/lacZY-R-SphI to amplify the lacZY gene fragment. The PCR product of lacZY was digested with XbaI/SphI and inserted into the XbaI/SphI sites of pK18mobsacB to generate pK18-lacZY. The primers Pcub-F-BglII/Pcub-R-XbaI were used to amplify the 500-bp cub promoter fragment from the C. necator JMP134 genomic DNA. The PCR product was digested with BglII/XbaI and inserted into the similarly digested pK18-lacZY to produce pK18-Pcub::lacZY. The integrity of the insert in all constructs was verified by DNA sequencing.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | 5′–3′ sequencea | Function |

|---|---|---|

| cubE-1F-HindIII | CCCAAGCTTTGGCTGGCAGGGGCTTTACTTG | Generate pK18-ΔcubE |

| cubE-1R | TTCACCGTTGGCGGCAGGATC | |

| cubE-2F | GATCCTGCCGCCAACGGTGAACTGCAGCACGGGCTCACCAAC | |

| cubE-2R-XhoI | CCGCTCGAGCCGTAACACAGTCCCACCACCCAG | |

| cubA-1F-HindIII | CCCAAGCTTATTCGGTCGGTGTCCATCGGC | Generate pK18-ΔcubA |

| cubA-1R | TGGGAGGGTGCTTGTTGTCTGGA | |

| cubA-2F | TCCAGACAACAAGCACCCTCCCAACATCGTGGGGCGGCTTCTCG | |

| cubA-2R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACAATGCCTGTGCCCGGGTCTCC | |

| fur-1F-BamHI | CGCGGATCCTGCGGGGCAGCGGGTGTTG | Generate pK18-Δfur |

| fur-1R | ACGGTCGCCTTTAGGCCGATATTCTTG | |

| fur-2F | CAAGAATATCGGCCTAAAGGCGACCGTGTCGCTGTACGG | |

| fur-2R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACGAACTGCATATCAAGCTGGTCGAATCCC | |

| SPR-1F-EcoRI | CGGAATTCGAAGTGTCGGGTGCTCTTGTGCG | Generate pK18-PBAD |

| SPR-1R | ACGCACGTGTGGCCAGCCC | |

| PBAD-F | GGGCTGGCCACACGTGCGTTTGCCGTCACTGCGTCTTTTACTGG | |

| PBAD-R | CCAAAAAAACGGGTATGGAGAAACAGTAG | |

| SPR-2F | CTACTGTTTCTCCATACCCGTTTTTTTGGCCTTGAGCATGCCGGTCCCC | |

| SPR-2R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACCGTCAGCCAGCGTTGGAGATTG | |

| cubE-F-HindIII | CCCAAGCTTATGCTGAATCTACAGTCCGCAAGCC | Generate pBBR1MCS-2-cubE |

| cubE-R-BamHI | CGCGGATCCTCAGGCCTCTTTCCCTTGACGC | |

| cubA-F-HindIII | CCCAAGCTTATGCCGGTCCCCGGTCAGAC | Generate pBBR1MCS-2-cubA |

| cubA-R-BglII | GGAAGATCTTCAGAATTCAACGGTGGCGGAC | |

| fur-F-BamHI | CGCGGATCCATGCCGAGTCCGGCGGAGCTC |

Generate pBBR1MCS-2-fur pBBR1MCS-5-fur pET28a-fur |

| fur-R-SalI | ACGCGTCGACTTATCGTTTTGGTCTGTGGGGACAATCAG | |

| fur-F-HindIII | CCCAAGCTTATGCCGAGTCCGGCGGAGCTC | |

| fur-R-XbaI | TGCTCTAGATTATCGTTTTGGTCTGTGGGGACAATCAG | |

| QJMP 16S-F | GGGGAGTACGGTCGCAAGA | qRT-PCR |

| QJMP 16S-R | ATGTCAAGGGTAGGTAAGGTTT | |

| QcubE-F | TGGATGACCAGCGAGCAGC | |

| QcubE-R | AGCCGTCTTCCGTCTTGAGG | |

| QcubD-F | CATTGCCCACGCCCTTGT | |

| QcubD-R | GAGTGGCTTGACGGAAGACAGAT | |

| QcubC-F | GTGCTGTTGCTGAAGGTGGAGA | |

| QcubC-R | ATCACGCCGTTCGGTTGC | |

| QcubB-F | TGCAGGGCCTGAAGCACATT | |

| QcubB-R | GGGTCTCCCAGCCATAACCACTC | |

| QcubA-F | CGCGTTGACGATTTGTGGC | |

| QcubA-R | CTGACGAGTCCCTGCTGTTCC | |

| Pcub-F-BglII | GGAAGATCTCGCACGCAAATGCGCGCATCG | Generate pK18-Pcub::lacZY |

| Pcub-R-XbaI | TGCTCTAGAACCGGGGACCGGCATGCTCA | |

| PkatG-F-BamHI | CGGGATCCGGCAATCCTTCCTGCAGCGTGG | Generate pK18-PkatG::lacZY |

| PkatG-R-XbaI | GCTCTAGATGTTCCCTCCTTGCTTCGATTGCAT | |

| lacZY-F-XbaI | TGCTCTAGAATGACCATGATTACGGATTCAC | Generate pK18-lacZY |

| lacZY-R-SphI | GTGCGCATGCTTAAGCGACTTCATTCACCTGA | |

| cub-EMSA-F | CCAGCGGTTTCGGACAGATCAAG | EMSA |

| cub-EMSA-R | GTCAGGAGCCTATTGCAAATGCGA | |

| control-F | CCAGCGGTTTCGGACAGATCAAG | |

| control-R | GTCAGGAGCCTATTGCAAATGCGA |

Underlined sites indicate restriction enzyme cutting sites added for cloning. Letters in bold denote the annealing regions for overlap PCR.

In-frame deletion, promoter replacement, and complementation in C. necator JMP134.

For constructing in-frame deletion mutants, the pK18mobsacB derivatives were transformed into the relevant C. necator JMP134 strains through E. coli S17-1λ pir-mediated conjugational mating to carry out single crossover on NB plates at 30°C for 16 h. Cells were suspended in M9 medium, and the appropriate dilutions were spread on M9 minimal medium agar plates with 8 mM succinic acid as a carbon source containing 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) (to select against the donor strain) plus kanamycin (to select for the recipient with the nonreplicating plasmid integrated into its chromosome). Several colonies were transferred to NB medium and incubated at 30°C overnight before spreading the appropriate dilutions were spread on NB plates containing 20% sucrose for counterselection against single-crossover mutants. Double-crossover mutants resulting in the nonpolar deletion of cubE were verified by PCR, using the external primer pairs cubE-1F-HindIII/cubE-2R-XhoI and DNA sequencing. The same method was used for replacing the native cub promoter with the arabinose-inducible promoter PBAD by transforming the C. necator wild-type strain with the promoter replacement plasmid pK18-PBAD. For complementation, the pBBR1MCS derivatives were transformed into the relevant C. necator strains by electroporation, and the expression in C. necator was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG.

Construction of chromosomal fusion reporter strains and β-galactosidase assays.

The lacZY fusion reporter vector pK18-Pcub::lacZY was transformed into E. coli S17-1λpir, and this was mated with C. necator strains, as described previously (53). The lacZY fusion reporter strains were grown to stationary phase in NB or M9 medium at pH 7.0 and 30°C, unless otherwise specified, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed using o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) as the substrate (54). These assays were performed in triplicate at least three times.

Overexpression and purification of recombinant protein.

To express and purify recombinant His6-Fur protein, the pET28a-fur plasmid was transformed into a BL21(DE3) host strain. Bacteria were cultured at 37°C in LB medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5, shifted to 24°C, induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, and then cultivated for an additional 10 h at 24°C. Harvested cells were disrupted by sonication and purified using His Bind nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin (Novagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified recombinant proteins were dialyzed against the appropriate buffer overnight at 4°C and stored at −80°C until use. The purity of the purified protein was verified as >95% homogeneity based on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay.

Cultivation and characterization of the siderophore.

The promoter-replaced Sid− mutant was grown overnight in NB medium inoculated from a single colony from agar plates. After washing three times with M9 medium, the pellet was diluted 1:500 in fresh M9 medium, inoculated overnight to an OD600 of 0.1, and induced with 0.2% arabinose. After 72 h of cultivation, the culture was centrifuged for 20 min at 13,000 rpm. For wild-type strains, they were inoculated under iron-limiting conditions. Fe3+ was added to repress siderophore production. After a 10-fold concentration, the supernatant was mixed with CAS solution to detect the presence of siderophores. To determine the type of siderophore, different chemical tests were performed. The FeCl3 test (22) was used to determine hydroxamate groups, and the Arnow test (21) was used to determine catecholate groups with catechol as positive controls. Phenolate groups were detected by the ferric chloride ferricyanide reagent (23), with phenol as a positive control. Carboxylate groups were detected by the copper sulfate reagent, as they can form a blue complex with copper, with a maximum absorption peak at 190 to 280 nm (24).

The production of siderophore was detected by using colorimetric chromeazurol S (CAS) agar plates (19). For each strain, a 10-µl sample of an NB culture (OD600, 0.8) was spotted on CAS plates. The zone of color change was photographed after 5 days of incubation at 30°C. For quantitative determination of siderophore production, the zone of color change was measured after 5 days from the edge of colony growth to the edge of the orange halo.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

EMSA was performed as described by Zhang and colleagues (52), with minor modifications. Briefly, the cub promoter probe (75 bp) was amplified from the cub promoter region of the corresponding pK18-Pcub::lacZY reporter vector (Table 1) using primers cub-EMSA-F/cub-EMSA-R. Increasing concentrations of purified His6-Fur (0.38, 0.76, and 1.14 μM) were incubated with 10 nM DNA probes in EMSA buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 4 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol). After incubation for 20 min at room temperature, the binding reaction mixture was subjected to electrophoresis on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel containing 5% glycerol in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) electrophoresis buffer, and the DNA probe was detected using SYBR green. A 75-bp fragment amplified from the reut_A1723 coding region using primers control-F/control-R (Table 2) or bovine serum albumin (BSA) was included in the binding assay to serve as a negative control.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Bacteria were harvested during the mid-exponential phase, and RNA was extracted using the RNAprep Pure cell/bacteria kit and treated with RNase-free DNase (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The purity and concentration of the RNA were determined by gel electrophoresis and a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Thermo Scientific). First-strand cDNA was reverse transcribed from 2 µg of total RNA with the TransScript first-strand cDNA synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, USA) with TransStart green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech). For all primer sets (Table 2), the following cycling parameters were used: 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s and 55°C for 30 s. For standardization of results, the relative abundance of 16S rRNA was used as the internal standard. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the expression of target genes was calculated as relative fold values using the 2−ΔΔCT method. These assays were performed in triplicate at least three times.

Determination of intracellular ion content.

Intracellular ion content was determined as described previously (55, 56). Briefly, cells were grown in M9 medium or in NB medium until stationary phase. After harvesting 20 ml of the culture and washing twice with M9 medium, the pellets’ weights were measured, and bacteria were chemically lysed using BugBuster (Novagen, Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bacteria were resuspended in BugBuster solution by pipetting and incubation on a rotating mixer at a slow setting for 16 h. The total protein content for each sample was measured by using NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each sample was diluted 10-fold in 2% molecular-grade nitric acid to a total volume of 8 ml. Samples were analyzed by using atomic absorption spectroscopy (ZEEnit 650P; Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany), and the results were corrected using the appropriate buffers for reference and dilution factors. Triplicate cultures of each strain were analyzed during a single experiment, and the experiment was repeated at least three times.

Sensitivity assays.

Mid-exponential-phase C. necator JMP134 cells grown in NB medium were collected, washed, and diluted 50-fold into M9 medium containing Fe3+ (1.5 μM or as indicated), and then treated with H2O2 (0.1 mM), phenol (30 mM), meta-nitrophenol (MNP; 3 mM) or 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D, 20 mM) at 30°C for 25 min. After treatment, the cultures were serially diluted and plated onto NB agar plates, and colonies were counted after 36 h of growth at 30°C. The percent survival was calculated by dividing the number of CFU of stressed cells by the number of CFU of cells without stress (57, 58). All these assays were performed in triplicate at least three times.

Swimming motility.

Swimming motility assays were performed as previously described (59). Briefly, a single colony selected from NB plates was touched slightly on soft agar medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% NaCl, 0.3% Bacto agar [BD, USA]) and incubated for 1 or 2 days under 30°C before observation (60). Motility halos were measured after photographs were taken of representative plates for each strain after 8, 16, 24, and 32 h of incubation.

Biofilm formation assay.

Biofilm formation was determined according to the method of O’Toole and Kolter (35), with minor modifications. Briefly, overnight bacterial cultures were diluted 100-fold in fresh NB medium containing 1 mM IPTG and 50 µg ml−1 kanamycin. After vertical incubation for 5 days with shaking at 140 rpm in 30°C, the NB medium was removed, and the test tubes were washed twice with M9 medium. Cells that adhered to the test tubes were stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min and then washed twice with M9 medium. The cell-bound dye was eluted in 5 ml of 95% ethanol, and the absorbance at 590 nm of the eluted solution was measured using a microplate reader. The average and SEM values were calculated from eight wells for each sample.

Bioinformatics analyses.

Sequence alignment and database searches were carried out using the BLAST server of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and visualized by using BioEdit (www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html). antiSMASH analysis was performed using version 4.0.2, which provides direct information about known homologous genes (20).

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were performed at least in triplicate and repeated on two different occasions. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between frequencies were assessed by Student’s t test (bilateral and unpaired). Statistical analysis of results was conducted with GraphPad Prism version 5.00 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), using a P value of <0.05 as statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Ning-Yi Zhou at Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Luying Xun at Washington State University for providing valuable reagents.

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant 2017YFD0502105) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31671292 and 31370150).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01938-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miethke M, Marahiel MA. 2007. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71:413–451. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanabe T, Naka A, Aso H, Nakao H, Narimatsu S, Inoue Y, Ono T, Yamamoto S. 2005. A novel aerobactin utilization cluster in Vibrio vulnificus with a gene involved in the transcription regulation of the iutA homologue. Microbiol Immunol 49:823–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2005.tb03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hider RC, Kong X. 2010. Chemistry and biology of siderophores. Nat Prod Rep 27:637–657. doi: 10.1039/b906679a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurth C, Kage H, Nett M. 2016. Siderophores as molecular tools in medical and environmental applications. Org Biomol Chem 14:8212–8227. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01400c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaible UE, Kaufmann SH. 2004. Iron and microbial infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:946–953. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin J, Zhang W, Cheng J, Yang X, Zhu K, Wang Y, Wei G, Qian PY, Luo ZQ, Shen X. 2017. A Pseudomonas T6SS effector recruits PQS-containing outer membrane vesicles for iron acquisition. Nat Commun 8:14888. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visca P, Leoni L, Wilson MJ, Lamont IL. 2002. Iron transport and regulation, cell signalling and genomics: lessons from Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas. Mol Microbiol 45:1177–1190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun V. 2003. Iron uptake by Escherichia coli. Front Biosci 8:s1409–s1421. doi: 10.2741/1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schalk IJ, Yue WW, Buchanan SK. 2004. Recognition of iron-free siderophores by TonB-dependent iron transporters. Mol Microbiol 54:14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Don RH, Pemberton JM. 1985. Genetic and physical map of the 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degradative plasmid pJP4. J Bacteriol 161:466–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lykidis A, Pérez-Pantoja D, Ledger T, Mavromatis K, Anderson IJ, Ivanova NN, Hooper SD, Lapidus A, Lucas S, González B, Kyrpides NC. 2010. The complete multipartite genome sequence of Cupriavidus necator JMP134, a versatile pollutant degrader. PLoS One 5:e9729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu F, Jiang X, Zhang JJ, Zhou NY. 2014. Construction of an engineered strain capable of degrading two isomeric nitrophenols via a sacB- and gfp-based markerless integration system. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:4749–4756. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pérez-Pantoja D, De la Iglesia R, Pieper DH, González B. 2008. Metabolic reconstruction of aromatic compounds degradation from the genome of the amazing pollutant-degrading bacterium Cupriavidus necator JMP134. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:736–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatt G, Denny TP. 2004. Ralstonia solanacearum iron scavenging by the siderophore staphyloferrin B is controlled by PhcA, the global virulence regulator. J Bacteriol 186:7896–7904. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7896-7904.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilis A, Khan MA, Cornelis P, Meyer JM, Mergeay M, van der Lelie D. 1996. Siderophore-mediated iron uptake in Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 and identification of aleB encoding the ferric iron-alcaligin E receptor. J Bacteriol 178:5499–5507. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5499-5507.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreutzer MF, Kage H, Nett M. 2012. Structure and biosynthetic assembly of cupriachelin, a photoreactive siderophore from the bioplastic producer Cupriavidus necator H16. J Am Chem Soc 134:5415–5422. doi: 10.1021/ja300620z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreutzer MF, Nett M. 2012. Genomics-driven discovery of taiwachelin, a lipopeptide siderophore from Cupriavidus taiwanensis. Org Biomol Chem 10:9338–9343. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26296g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saha M, Sarkar S, Sarkar B, Sharma BK, Bhattacharjee S, Tribedi P. 2016. Microbial siderophores and their potential applications: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23:3984–3999. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwyn B, Neilands JB. 1987. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem 160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medema MH, Blin K, Cimermancic P, de Jager V, Zakrzewski P, Fischbach MA, Weber T, Takano E, Breitling R. 2011. antiSMASH: rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 39:W339–W346. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnow LE. 1937. Proposed chemical mechanisms for the production of skin erythema and pigmentation by radiant energy. Science 86:176. doi: 10.1126/science.86.2225.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neilands JB. 1981. Microbial iron compounds. Annu Rev Biochem 50:715–731. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hathway D. 1969. Plant phenols and tannins, p 390–436. In Smith I. (ed), Chromatography, 3rd ed Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shenker M, Oliver I, Helmann M, Hadar Y, Chen Y. 1992. Utilization by tomatoes of iron mediated by a siderophore produced by Rhizopus-Arrhizus. J Plant Nutr 15:2173–2182. doi: 10.1080/01904169209364466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Münzinger M, Taraz K, Budzikiewicz H. 1999. Staphyloferrin B, a citrate siderophore of Ralstonia eutropha. Z Naturforsch C 54:867–875. doi: 10.1515/znc-1999-1103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchler-Bauer A, Zheng C, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lanczycki CJ, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Bryant SH. 2012. CDD: conserved domains and protein three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D348–D352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peigne C, Bidet P, Mahjoub-Messai F, Plainvert C, Barbe V, Medigue C, Frapy E, Nassif X, Denamur E, Bingen E, Bonacorsi S. 2009. The plasmid of Escherichia coli strain S88 (O45:K1:H7) that causes neonatal meningitis is closely related to avian pathogenic E. coli plasmids and is associated with high-level bacteremia in a neonatal rat meningitis model. Infect Immun 77:2272–2284. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01333-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neilands JB. 1992. Mechanism and regulation of synthesis of aerobactin in Escherichia coli K12 (pColV-K30). Can J Microbiol 38:728–733. doi: 10.1139/m92-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burbank L, Mohammadi M, Roper MC. 2015. Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition influences motility and is required for full virulence of the xylem-dwelling bacterial phytopathogen Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:139–148. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02503-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bagg A, Neilands JB. 1987. Ferric uptake regulation protein acts as a repressor, employing iron (II) as a cofactor to bind the operator of an iron transport operon in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 26:5471–5477. doi: 10.1021/bi00391a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Lorenzo V, Giovannini F, Herrero M, Neilands JB. 1988. Metal ion regulation of gene expression. Fur repressor-operator interaction at the promoter region of the aerobactin system of pColV-K30. J Mol Biol 203:875–884. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones AM, Lindow SE, Wildermuth MC. 2007. Salicylic acid, yersiniabactin, and pyoverdin production by the model phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000: synthesis, regulation, and impact on tomato and Arabidopsis host plants. J Bacteriol 189:6773–6786. doi: 10.1128/JB.00827-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Si M, Zhao C, Burkinshaw B, Zhang B, Wei D, Wang Y, Dong TG, Shen X. 2017. Manganese scavenging and oxidative stress response mediated by type VI secretion system in Burkholderia thailandensis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:E2233–E2242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614902114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.López D, Vlamakis H, Kolter R. 2010. Biofilms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000398. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Toole GA, Kolter R. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol Microbiol 30:295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tindale AE, Mehrotra M, Ottem D, Page WJ. 2000. Dual regulation of catecholate siderophore biosynthesis in Azotobacter vinelandii by iron and oxidative stress. Microbiology 146:1617–1626. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-7-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nobre LS, Saraiva LM. 2014. Role of the siderophore transporter SirABC in the Staphylococcus aureus resistance to oxidative stress. Curr Microbiol 69:164–168. doi: 10.1007/s00284-014-0567-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaudhry GR, Chapalamadugu S. 1991. Biodegradation of halogenated organic compounds. Microbiol Rev 55:59–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Symons ZC, Bruce NC. 2006. Bacterial pathways for degradation of nitroaromatics. Nat Prod Rep 23:845–850. doi: 10.1039/b502796a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jurkevitch E, Hadar Y, Chen Y, Libman J, Shanzer A. 1992. Iron uptake and molecular recognition in Pseudomonas putida: receptor mapping with ferrichrome and its biomimetic analogs. J Bacteriol 174:78–83. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.78-83.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banin E, Vasil ML, Greenberg EP. 2005. Iron and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:11076–11081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504266102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai S, Tremblay J, Deziel E. 2009. Swarming motility: a multicellular behaviour conferring antimicrobial resistance. Environ Microbiol 11:126–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cotgreave IA, Orrenius S. 1999. Reactive oxygen species in biological systems–an interdisciplinary approach. Science 284:1935–1936. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adler V, Yin Z, Tew KD, Ronai Z. 1999. Role of redox potential and reactive oxygen species in stress signaling. Oncogene 18:6104–6111. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dröge W. 2002. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev 82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adler C, Corbalan NS, Seyedsayamdost MR, Pomares MF, de Cristobal RE, Clardy J, Kolter R, Vincent PA. 2012. Catecholate siderophores protect bacteria from pyochelin toxicity. PLoS One 7:e46754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicholls P. 2012. Classical catalase: ancient and modern. Arch Biochem Biophys 525:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu YB, Long MX, Yin YJ, Si MR, Zhang L, Lu ZQ, Wang Y, Shen XH. 2013. Physiological roles of mycothiol in detoxification and tolerance to multiple poisonous chemicals in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Arch Microbiol 195:419–429. doi: 10.1007/s00203-013-0889-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neujahr HY, Kjellen KG. 1978. Phenol hydroxylase from yeast. Reaction with phenol derivatives. J Biol Chem 253:8835–8841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin Y, Zhou NY. 2010. Characterization of MnpC, a hydroquinone dioxygenase likely involved in the meta-nitrophenol degradation by Cupriavidus necator JMP134. Curr Microbiol 61:471–476. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mols M, Abee T. 2011. Primary and secondary oxidative stress in Bacillus. Environ Microbiol 13:1387–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang W, Wang Y, Song Y, Wang T, Xu S, Peng Z, Lin X, Zhang L, Shen X. 2013. A type VI secretion system regulated by OmpR in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis functions to maintain intracellular pH homeostasis. Environ Microbiol 15:557–569. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song Y, Xiao X, Li C, Wang T, Zhao R, Zhang W, Zhang L, Wang Y, Shen X. 2015. The dual transcriptional regulator RovM regulates the expression of AR3- and T6SS4-dependent acid survival systems in response to nutritional status in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Environ Microbiol 17:4631–4645. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller JH. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puri S, Hohle TH, O’Brian MR. 2010. Control of bacterial iron homeostasis by manganese. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:10691–10695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002342107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Champion OL, Karlyshev A, Cooper IA, Ford DC, Wren BW, Duffield M, Oyston PC, Titball RW. 2011. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis mntH functions in intracellular manganese accumulation, which is essential for virulence and survival in cells expressing functional Nramp1. Microbiology 157:1115–1122. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.045807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Si M, Zhang L, Chaudhry MT, Ding W, Xu Y, Chen C, Akbar A, Shen X, Liu SJ. 2015. Corynebacterium glutamicum methionine sulfoxide reductase A uses both mycoredoxin and thioredoxin for regeneration and oxidative stress resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:2781–2796. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04221-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Si MR, Zhang L, Yang ZF, Xu YX, Liu YB, Jiang CY, Wang Y, Shen XH, Liu SJ. 2014. NrdH redoxin enhances resistance to multiple oxidative stresses by acting as a peroxidase cofactor in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:1750–1762. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03654-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Inoue T, Shingaki R, Fukui K. 2008. Inhibition of swarming motility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by branched-chain fatty acids. FEMS Microbiol Lett 281:81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Atkinson S, Throup JP, Stewart GS, Williams P. 2002. A hierarchical quorum-sensing system in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is involved in the regulation of motility and clumping. Mol Microbiol 33:1267–1277. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schafer A, Tauch A, Jager W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Puhler A. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM Jr, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.