Abstract

Investigators have for decades used mouse voiding patterns as end points for studying behavioral biology. It is only recently that mouse voiding patterns were adopted for study of lower urinary tract physiology. The spontaneous void spot assay (VSA), a popular micturition assessment tool, involves placing a mouse in an enclosure lined by filter paper and quantifying the resulting urine spot pattern. The VSA has advantages of being inexpensive and noninvasive, but some investigators challenge its ability to distinguish lower urinary tract function from behavioral voiding. A consensus group of investigators who regularly use the VSA was established by the National Institutes of Health in 2015 to address the strengths and weaknesses of the assay, determine whether it can be standardized across laboratories, and determine whether it can be used as a surrogate for evaluating urinary function. Here we leverage experience from the consensus group to review the history of the VSA and its uses, summarize experiments to optimize assay design for urinary physiology assessment, and make best practice recommendations for performing the assay and analyzing its results.

Keywords: urinary dysfunction, void spot assay, voiding behavior

INTRODUCTION

There is a rich history of using mouse urination as a proxy for complex neural and behavioral phenomena (19, 28–32). Volatile and nonvolatile urinary solutes form chemical signatures denoting sex, species, and individual identity, and urine marking patterns are a manifestation of social dominance, sexual arousal, hormonal status, chronic or acute anxiety, and cortical function (4, 17). Olfactory cues signaling the presence of mates or competitors influence mouse micturition patterns. For example, socially dominant males promiscuously urinate small volumes, dispersing urine throughout the entire enclosure area, whereas subservient males and females urinate in a spatially restricted manner (11). Mice with surgically excised vomeronasal organs exhibit greater passivity in the presence of other males and alter their urine marking patterns accordingly (33), attesting to the importance of olfactory signaling in controlling urinary behavior.

Scientists recently began evaluating spontaneous urination patterns in unrestrained mice for a new purpose: to interrogate how urinary function changes in response to aging, diet, obesity, environmental chemicals, genetic mutations, and sex hormones (14, 25, 26, 31, 32, 35–37). In this regard, mouse voiding patterns are used to assess lower urinary tract dysfunction and serve as a proxy to model factors that give rise to lower urinary tract symptoms in humans. While this practice offers many advantages (assays of spontaneous urination are noninvasive and can be performed repeatedly on the same mouse, among others), concerns have been raised about whether experimentally induced changes in urinary physiology can be extricated from manifested urinary “behaviors” (e.g., stress from a new enclosure or environment). The National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disorders formed a consensus group in 2015 to explore the strengths and weaknesses of using spontaneous voiding patterns to evaluate mouse urinary physiology. This article is the culmination of the consensus group’s efforts to optimize and standardize the assay for this purpose. We are firmly of the view that spontaneous voiding behaviors offer important insight into urinary physiology and that sufficient literature now exists to justify its use for this purpose.

This article has three goals. The first is to review historical uses and interpretations of mouse voiding patterns. The second is to consolidate evidence that mouse voiding patterns accurately convey physiological changes in response to genetics, environment, age, and other factors. The third objective is to leverage consensus group experience and to make recommendations on void spot assay performance and interpretation. The contributing authors are aware that this paper does not represent the final word but hope that the information will provide guidance, context, and evidence of utility to members of the urology research community.

DEFINITION OF THE VOID SPOT ASSAY

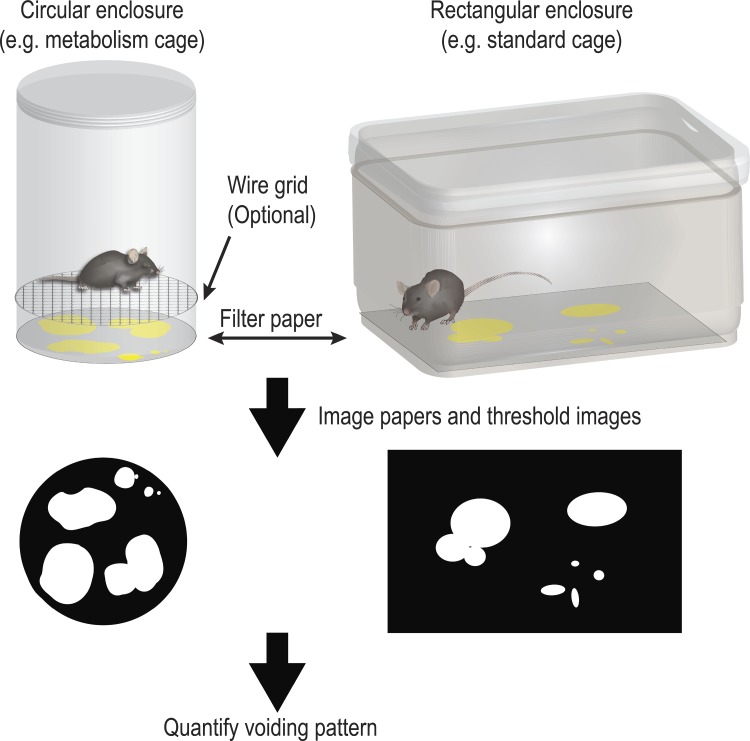

The void spot assay (VSA), also known as voiding spot on paper (VSOP) assay, is performed by placing a single mouse in an enclosure lined with absorbent filter paper and allowing the mouse to move freely for a defined period, during which micturition events are captured and retained as void spots on paper. The assay environment, including enclosure shape and whether mice directly contact filter paper or are elevated on a wire grid above it, varies across studies. Prototypical assay formats are illustrated in Fig. 1. The VSA is noninvasive and mice can be returned to normal housing after testing. Urine spots are either stained with ninhydrin, illuminated with ultraviolet (UV) light, or visualized with infrared or bright-field light and imaged, and voiding patterns are objectively or subjectively quantified. The VSA provides information about cumulative voiding behaviors over time, approximating the information provided by a voiding diary in human medicine. Mouse micturition is spontaneous and influenced by perception of bladder fullness and social behavior. The goal of many recent studies was to characterize assay design parameters to minimize the behavioral influence on voiding while extracting information about urinary physiology.

Fig. 1.

Prototypical void spot assay (VSA) assay designs. Enclosure size and shape vary across laboratories but the basic design is the same: the enclosure is lined with filter/chromatography paper and the mouse is introduced in direct contact with the paper or elevated above it on a wire mesh cage bottom. The mouse is maintained in the cage for a fixed time interval, the paper is removed, dried, imaged and spot number, size and distribution are determined using custom methods or existing image analysis software (46).

WHAT INFORMATION DOES THE VSA PROVIDE?

Voided volume and urine spot area are related. One study reported a linear range up to 700 µl (44), although VSA filter paper type and urinary solute concentration are likely to influence linear range. VSA end point data include total spot number, total voided volume, average void volume, and spatial distribution. A caveat to these measurements is that multiple urinary events can occur in a single location, creating concentric or nonconcentric overlapping spots that confound downstream analyses. Furthermore, experimental setup and other factors detailed below influence void spot spatial distribution.

The approach for quantifying VSA images and deriving biological meaning from them is to some degree determined by the investigator and tailored to the mouse model under investigation. For example, the distribution of void spot sizes is rarely normal and several studies have reported a bimodal distribution consisting of a high frequency of small volume voids and a low frequency of large volume voids (25, 49). In a polyuric model with large urine volumes, an investigator might decide that spots below a threshold value (e.g., <10 μl) may be excluded because they represent a very small fraction of total volume. In contrast, an investigator who hypothesizes the presence of an overactive bladder, urinary tract infection, incontinence, or obstruction in their model is likely to be very interested in the number of small spots. Each investigator will likely define spot size discrimination (i.e., cutoffs or sorting into discrete groups), as required to appropriately test the relevant hypotheses. As long as the assumptions are clearly stated and the assay experimental details are clearly outlined, the approach can be critiqued and reproduced by others. To facilitate critical evaluation and increase rigor and reproducibility, we recommend that all studies using the VSA report the minimal information listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recommendation on minimal experimental design information for void spot assay studies

| Design Details |

|---|

| 1. Gender and age |

| 2. Mouse strain |

| 3. Assay duration |

| 4. Time of day |

| 5. Whether acclimation was performed |

| 6. Access to food and water during the assay |

| 7. How assay papers were imaged |

| 8. Spot size exclusion (if any) |

| 9. How overlapping spots were analyzed |

| 10. How data were quantitated |

Mice exhibit thigmotaxis, a behavior described as “wall seeking,” which is related to anxiety, fear, and learning (27). It is an inherited and modifiable property (12, 18, 40). Thigmotaxis probably explains why healthy mice, with the exception of aggressive dominant males (11, 39), almost always urinate at the edge of their cage. As a result, we have found that one useful way to evaluate spatial distribution is to evaluate the ratio of edge voiding to center voiding. Mice will often void several times in the same area as if to define a localized, safe voiding location. Therefore, center voiding can indicate abnormal micturition. Normal female C57BL/6J mice tested in circular metabolic cages also exhibited an edge preference for micturition suggesting thigmotactic behavior regardless of the shape of enclosure (7).

CORRELATION WITH URODYNAMICS

Hodges et al. (16) were the first to evaluate the potential of using the VSA as a surrogate for cystometric evaluation. They tested control animals and uroplakin II knockout mice by performing VSA and cystometry. Void patterns were graded from 1 to 5 on the basis of size and frequency by observers blinded to the genotype. They concluded that the degree of urine spot “dispersion” is highly correlated with cystometric baseline pressure, threshold pressure, and average intermicturition pressure. VSA end points did not correlate with other cystometry end points (i.e., peak pressures, bladder capacity, and spontaneous contractile activity). They concluded that VSA can provide a simple method for evaluating bladder function that correlates well with some cystometric parameters.

In a similar fashion, several studies testing bladder function in knockout or hormone-treated mice showed consistent correlations between abnormal VSA patterns and abnormal cystometric profiles (13, 15, 22, 26). As an example of a study demonstrating internal consistency between VSA and cystometry, Rajandram et al. (36) investigated ketamine cystitis in mice. VSA analysis showed ketamine-treated mice had a higher number of primary voids (voids >20 µl) but a smaller volume/void, indicating smaller, but more frequent, micturition events. Cystometry data were confirmatory of the VSA data, as ketamine-treated mice also showed significantly reduced intercontractile intervals. In contrast, Ritter et al. (38) reported that Htr3a mutant mice void more frequently than controls based on VSA analysis, but voiding frequency was not different between genotypes when assessed by cystometry.

It is the consensus group’s opinion that VSA and cystometry are distinct assays measuring discrete parameters that may or may not be complementary given they are designed to measure different physiological readouts. Cystometry, for example, is often performed under anesthesia, thus removing higher cortical control of micturition, while VSA is performed in conscious, nonrestrained mice. Mouse cystometry is also typically performed using infusion rates, which greatly exceed mouse physiological urine output (estimated at 0.4 to 1.3 ml·20 g body wt−1·day−1) (41).

TECHNICAL ASPECTS FOR PERFORMING VSA

Mice are intelligent, sensitive, and social animals. Therefore, as with any experiment relying on live mouse behavior, many variables influence assay outcomes. When conditions are carefully controlled however, the VSA has many advantages and, in the opinion of the consensus group, these outweigh the disadvantages. Table 2 provides a detailed list of VSA advantages and disadvantages. We and others have rigorously investigated how several assay variables influence outcomes (6, 7, 25, 44, 46, 48). Table 3 summarized technical parameters known to influence VSA outcomes.

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of the VSA

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Noninvasive (mice can be followed longitudinally and it does not cause bladder instrumentation injury) | Pathophysiology can be difficult to interpret (e.g., disperse spotting might indicate overactivity and frequency, or sphincter dysfunction). |

| Can be repeated on the same mouse several times on consecutive days to establish its “mean” voiding behavior; this can reduce experimental noise | Semiquantitative (overlapping urine spots are difficult or impossible to resolve using standard approaches, resulting in data loss. This disadvantage is counteracted in part by newly available software that can objectively separate nonconcentric overlapping urine spots and by procedural modifications such as reducing the testing time to reduce concentric overlapping spots) (46). |

| Inexpensive | Bladder fullness at the beginning of the assay is usually not controlled (although in our experience, 4-h filter papers are rarely unstained and when they occur represent <5% of assayed mice). Repeating assays on the same mice can overcome this limitation, or alternatively, empty filters can be removed from the analysis if they appear not representative of group behavior. |

| No specialized equipment required | Some male mice can exhibit territorial marking behavior with extensive volitional spot voiding over large areas of the filter and can skew results (in our experience most group housed males do not exhibit this behavior) (25). |

| Easy to perform | Results can be subtly influenced by multiple variables including time of day, experimental setup, choice of filter paper, age of mice, diet cage type, etc. This reinforces our recommendation for fuller description of assay conditions when reporting data and for laboratories to standardize assay conditions. |

| Rapid screening, particularly for new models | Filters are sometimes damaged by chewing. It is usually possible to identify urine spot borders even if chewed and repair the image by outlining and filling the area before quantitation with an image processing software such as ImageJ. |

| Reproducible | |

| Amenable to high throughput testing | |

| Can by multiplexed with other assessments (cystometry, uroflowmetry, contrast-enhanced ultrasound, others) | |

| New software automates and reduces bias in data analysis |

VSA, void spot assay.

Table 3.

Influence of VSA procedural parameters on voiding behaviors

| Procedural Modification | Primary Influence on Voiding Behavior | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Acclimatize mouse to testing cage | Primary void area | (25, 34, 48) |

| Mouse age | Spot number, primary void | (25, 44, 48) |

| Size and shape of cage | Total void area, primary void size | (7) |

| Duration of assay | Total void area | (46) |

| Access to water | Primary void size in females, no effect in males | (7, 46) |

| Presence of grid between mouse and paper | Spot number, volume/void | (7, 46) |

| Time of day | No effect in females, but primary void and total void area affected in males | (25, 34, 48) |

| Number of mice evaluated concurrently | Spot number | (7) |

The VSA has been used by many groups and across many mouse models in the last 15 yr and methodology is as varied as the purposes for which it has been used. Wu et al. (47) used the VSA as a readout of gender-specific behavior to examine the influence of sex hormones on neural circuit development. They performed the VSA for 1 h on filter paper with spot numbers and center versus edge voiding a key discriminator between groups. Daly et al. (10) examined age-related changes to male mouse urothelial function. Their assays were performed on filter paper for 4 h with free access to food and water. Kanasaki et al. (22) tested a urothelial-specific knockout mouse lacking β1-integrin and concluded that mechanosensory defects led to bladder overactivity and incontinence. Their assay was also 4 h on filter paper, but water access was restricted during that time. Using a similar VSA duration and water restriction, Keil et al. (26) showed that dietary folic acid enrichment reduces progression of an obstructive voiding phenotype in mice treated with testosterone and estradiol implants. Gevaert et al. (13) acclimated transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 knockout mice for 48 h on filter paper before performing their VSA for 24 h. Guo et al. (15) ran their mouse model of urofacial syndrome lacking the gene for heparinase 2 on filter paper as well but for 3 h. Cornelissen et al. (9) were interested in the effect of genetic background and gender on voiding function as were Yu et al. (48). In the former study, mice were acclimated for 2 h and then had fresh filter paper for a 1-h test period. Yu et al. did 4 h with no acclimation. Biallosterski et al. (4) ran experiments on their Alzheimers’ mouse model using mice placed on metal grids elevated above filter paper. Their mice were acclimated for 5 h a day earlier and then tested for 5 h with no access to water. Gharaee-Kermani et al. (14) also used elevated metal grids to examine voiding behaviors in control and obese diabetic mice with a 5-h assay duration. Other investigators (34, 42, 43) described a method for continuous recording of voiding by placing slowly moving paper below a grid and recording voiding events for 24 h. Ritter et al. (38) tested Htr3a knockout mice using a 4-h testing period without access to water. Wegner et al. (46) compared voiding behaviors in control and obese diabetic mice for assay durations from 1 to 4 h with mice placed directly on the filter paper compared with mice placed on a grid elevated above the paper. Thus many variations exist and have provided useful information on a range of mouse models and experimental interventions designed to interrogate lower urinary tract function.

The VSA has been used to accurately predict increased frequency with chemical cystitis and with age (44). It has been used to identify the impact of sex hormones on voiding function (1, 35). It has been used to identify a diet-induced physiological change in voiding behaviors (confirmed by cystometry) (26, 48). It has been used to validate genetically induced changes in voiding (5, 22, 38). It successfully distinguishes the impact of drugs on voiding function (20, 36, 44) and signals bladder irritation from transient urothelial damage due to protamine sulfate instillation (48). This selection of studies is intended as a sampling of the literature to illustrate the numerous ways in which the VSA is performed.

Another experimental variable is the filter paper used. Whatman #1 is a popular choice, but Benchkote, Whatman 470, Blicks Cosmos blotting paper, and Bio-Rad filter papers have all been used. Some studies did not specify the paper used. Since filter paper generally derives from the same materials regardless of make or manufacture, one could observe that it does not matter, as long as the absorbent properties of the paper are determined and reported. However, the paper may be a significant variable if mice react differently to various papers or patterns of urination are altered by smell, color, or texture. To our knowledge this has not been investigated.

Most, if not all, published reports omitted some detail or details that would be important for other investigators wishing to replicate the experiment. Essential details that are often neglected include age and gender of mice, assay duration, time of day, filter paper make and manufacturer, enclosure size and shape, whether replicates were performed, and whether food and/or water were provided during testing. It has now been shown by members of this group that these variables do alter outcomes (7, 25, 46). The consensus group has concluded that it is essential that investigators who use the VSA and report their results include all of these details, and Table 1 lists minimally required information; complete reporting of additional details will facilitate future improvements and increase investigator confidence in the assay.

VALIDATION STUDIES

Several studies have examined the validity and reproducibility of the VSA. In 2008, Sugino et al. (44) characterized their “voided stain on paper” method involving mice placed on wire grids elevated above filter paper for 2 h. The mice were hydrated with 50 µl/g distilled water before the assay, although the administration route for water was not specified. They concluded that the spot area:volume ratio was linear (using defined volumes of saline) up to 700 µl. They also showed that voided volumes increased with age and that males voided significantly more than females after 10 wk. The investigators alluded to one difficulty in the use of the wire grid: “When the entrapment of the voided urine by wire-net occurred, the dew on the wire was retrieved up by the filter paper at the corresponding stain point as soon as possible.” Presumably this required someone to watch each enclosure continuously and to “lift’ the filter paper to the grid before much evaporation occurred.

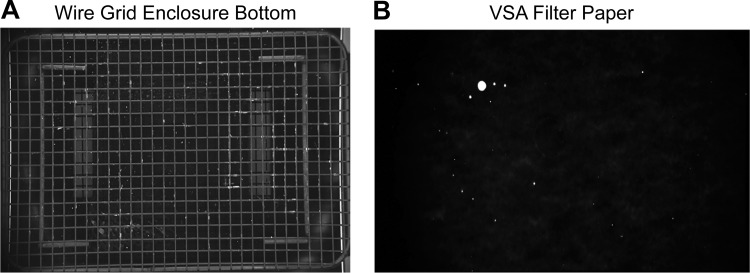

Wire grids placed above filter paper are often used as a way of preventing mice from damaging the paper and for this purpose has been shown effective (46). The wire mesh also potentially alleviates artifacts from the mice being in contact with urine-soaked paper, although these artifacts are far less frequent than some have suggested (46). There are two main drawbacks to the use of grids. First, urine can adhere to the wire and this will affect quantitation and potentially spot numbers. Figure 2 illustrates UV imaging of a grid (Fig. 2A) and the paper from a VSA performed with the mouse placed on the grid and thus elevated above the filter paper. Note in Fig. 2A urine clinging to the grid. A recent study demonstrated that treating the grid with a hydrophobic spray to reduce urinary adhesion did not significantly change urine spotting patterns (46). An additional problem associated with using grids as part of the VSA design is that grids induce stress by creating an unfamiliar environment as well as footing underneath. Chen et al. (7) convincingly showed that C57BL6/J female mice exhibited altered micturition behavior on metal grids in circular metabolic cages/enclosures with fewer voids of larger volumes/void and overall a reduced volume of urine, and Wegner et al. (46) observed similar responses to the grid using BTBR control and obese diabetic mice. These findings are consistent with typical stress-related alterations. We report these findings so that investigators are aware of the impact of assay design parameters. Models can be compared or interventions tested with grids fitted over the filter paper, but it has been speculated that elevating mice over the cage bottom introduces an environmental variable to which mice cannot acclimatize (21, 45), adding a confounding behavioral variable to assessments of urinary function.

Fig. 2.

Evidence of urine residue on wire grid elevated above the enclosure bottom. A single 12-wk-old female C57BL/6 mouse was housed for 4 h in an enclosure containing a wire grid elevated over filter paper. A: the grid was illuminated with UV light and imaged. Note multiple white spots that indicate urine residue on the grid. B: the filter paper was illuminated by UV light and imaged. The grid and filter paper images are shown in the same orientation (i.e., left side of the grid corresponds to the left side of filter paper).

Yu et al. (48) were interested in VSA reproducibility at the level of individual animals and genetic strain. Using females, they tested eight different strains of mice and found that each strain had a characteristic voiding pattern and that individual mice produced very similar results when tested over 5 consecutive days at the same time of day. Their assays were performed on filter paper for 4 h and mice had access to food but no water. Bjorling et al. (6) extended these observations to male mice and addressed whether the data of Yu et al. (48) were reproducible when performed in comparable fashion on the same strains, but in a different laboratory and geographical location. The results were consistent, demonstrating that different investigators in different locations can generate comparable data using VSA under well-defined conditions.

Keil et al. (25) used an identical protocol to perform an in-depth assessment of voiding behavior in male C57BL/6J mice, one of the most commonly used strains in biomedical research. They assessed cage density effects, time of day effects, aging for up to 9 wk, and impact of mating. They found voiding was not different in single housed versus group housed males and in virgin versus. mated males. However, age, time of day, and repeated testing each induced change. They concluded that typical housing and animal husbandry practices can influence voiding patterns.

DATA ANALYSIS

Urine-stained papers can be imaged in several ways. Dried mouse urine is fairly visible on many types of white filter paper and can be directly photographed. However, this method does not provide enough color contrast to threshold the image into a binary format for quantitation using image analysis software such as ImageJ. Urine spots can be highlighted by drawing around the spots either on the paper itself or with the freehand tool on the digital image. This approach is not so feasible if large numbers of filters require analysis or if the mouse model in question generates high numbers of very small spots. Urine spots can also be stained using ninhydrin to enhance contrast before bright-field imaging (34, 38). The most popular maneuver is to visualize urine spots with UV illumination, causing urine to fluoresce brightly. Contrast is much improved for subsequent image analysis.

Automated image analysis allows investigators to focus on micturition patterns most relevant to their model. In general, most will quantitate spot number and total spot area/volume as two key parameters. In addition, spots of different sizes can be grouped or binned. Binning is performed on the basis of size, with bin sizes determined by investigators. Mice will void several times in the same corner or area near the edge. This may reflect both sanitary behavior as well as thigmotaxis. Corner/edge voiding may also be related to urinating in the safest location to avoid predation. Overall, this suggests that center voiding should be considered aberrant, either from a behavioral (psychological) or a physiological standpoint. Regardless, many studies draw attention to and quantitate voiding location as a useful parameter in various models of disease or aging.

A step-by-step guide to image analysis using the freely available Fiji version of ImageJ (http://fiji.sc/) is described by Ackert-Bicknell et al. (2). This is one method for performing the thresholding and particle analysis functions that enable spot detection and area quantitation. However, the newly developed Void Whizzard plugin from University of Wisconsin-Madison is an advanced tool for automated analysis of VSA images with several major advantages (46). First, it has been independently validated by several different laboratories; second, it is able in most cases to automatically separate nonconcentric overlapping urine spots thus increasing data resolution and accuracy; and third, it is freely available as an ImageJ plugin subscription with instruction manual (https://imagej.net/Void_Whizzard).

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PERFORMING VSA

This consensus group is unanimous in its belief that available evidence supports the conclusion that the VSA offers reliable physiologically relevant data on bladder and lower urinary tract function. In addition, the assay appears to be robust enough to tolerate a range of experimental conditions. No doubt some produce greater stress for the mice than others (e.g., grids versus solid flooring). However, when an intervention is tested against appropriate control animals, as long as the setting and conditions are the same for both groups, and the procedural details are fully reported as part of the methods, differences between groups can be regarded as meaningful. Having stated this however, we believe there are “preferred” options for reducing psychological stress and allowing more normal urodynamic function to occur.

Grid Versus No Grid

The main reason for including a grid is to separate mice from the filter paper to reduce chewing of the paper and potential artifacts (tail drags, footprints) created from mice tracking through urine spots. We showed recently that elevating mice on a grid does little to reduce small spots on the paper, suggesting these are not artifacts but rather true voids (46). Our reservations regarding placing mice on a grid above the paper revolve around two issues. One is the physical retention of urine on the grid (Fig. 2A). Hydrophobic treatment of the grid, at least in one study, did little to alleviate this concern (46). The second is the novel environmental stress arising from uncertain footing. Kalliokoski et al. (21) showed that metabolic cage environments with typical metal grid flooring are so stressful that BALB/c male mice excreted 10 times higher amounts of corticosterone metabolites in feces. Urinary biomarkers indicated elevated levels of oxidative stress, and increased creatinine excretion suggested increased muscle catabolism. Stress was chronic with no adaptation even up to 3 wk. They conclude that data obtained from mice in metabolic cage type environments requires cautious interpretation “as their condition cannot be considered representative of normal physiology” (21). Therefore, our recommendation is to place mice directly on filter paper. This system is also more easily scalable. If paper destruction is a problem, alternative material can be investigated. Each type of filter substrate will require a separate standard curve to establish the area:volume relationship.

Assay Duration

It appears useful information can be derived anywhere from 1 to 24 h. Duration of testing should not exceed 4 h if water is restricted since mice can become dehydrated relatively quickly (3). In addition, in cages with nothing but filter paper, there are likely to be psychological impacts from lack of enrichment. The balance for the investigator is to test mice for a sufficient length of time to obtain a “phenotype.” In our opinion 2–4 h is optimal.

Time of Day

As mice are nocturnal, it is reasonable to assume greater metabolic and behavioral activity will occur at night. This is supported by several studies (34, 48). It is possible that day time voiding assays during a normally somnolent time may reveal more about the physiology of the lower urinary tract and less about behavior. Of course, in the real world, it is not practical for most laboratories to run assays at night, particularly due to 12-h light-dark cycles used in animal facilities, which require the handler to place mice in assay cages in the dark. Our conclusion is that virtually all published VSA data have been gathered during normal laboratory hours and have been shown to be informative for studies of genetics, disease, diet, aging, and drugs. The time of day should necessarily be specified in any description of the experimental methods.

Food and Water

Ideally both should be provided throughout the period of the assay. In practice, water is often withheld, particularly if the mouse is being tested in a standard mouse cage, due to the deleterious effects of dripping water onto the filter paper. Water that gets on the filter paper dilutes and spreads any urine spots that it encounters. It has also been the anecdotal evidence of some among us that tap water provided to mice can leave ‘ghosting’ rings that fluoresce under UV light and confound image analysis and quantitation. Since food is dry, it can usually be provided without affecting results. It is possible to design a testing apparatus that would allow mice access to water that did not have the potential to drip onto the filter paper. However, Chen et al. (7) examined the question of water provision directly in 4-h VSAs. They showed that water versus no water in regular cages did not change any voiding parameters. However, changing the location of the water bottle in a custom-designed cage was sufficient to reduce void number and increase volume/void, suggesting an environmental stress (7). Wegner et al. (46) also found no practical effect of water restriction on voiding. It appears that limited water restriction does not place a physiological constraint on the number of voids or volume. In practice, the simplicity of placing a mouse in a standard cage lined with filter paper usually trumps the desire to design a special apparatus with water provision.

Acclimation

The evidence on the need for acclimation to the cage and surroundings where VSA will be performed is mixed. In female mice of eight different strains, Yu et al. (48) did not find any change in female mouse voiding patterns on 5 consecutive days with no prior acclimation period. However, Keil et al. (25) found that male C57BL/6J mice did significantly alter their voiding over 3 consecutive days. Evidence from behavioral studies in wild male mice also suggests a tendency to alter voiding with increasing environmental familiarity (32). Gender and genetics are therefore likely to influence the response of mice to the VSA environment. Since one of the tremendous advantages of the VSA is simplicity and ease of performance, we suggest that investigators repeat the VSA over several days to assess the tendency of their model to acclimate. A pilot trial could answer the question, and if it proves necessary, these procedures can be incorporated into the experimental protocol.

Replicates/Sample Size

The answer to this question relies to some degree the effects of treatment or genetic manipulations. If there is a reasonably robust effect of treatment or genetic alteration on lower urinary tract function, 8–10 mice/group will likely provide sufficient power to get a clear answer based on a single assay round. However, it may be necessary to assess results in preliminary studies to determine appropriate group sizes. Note that technical and biological factors influence group size. The technical factor’s impact can be minimized by automating analysis. In a multi-institutional study (46), four individuals were given the same set of images to evaluate and the number and area of urine spots varied considerably among them and substantial differences among investigators were reported. We recommend having the same investigator analyze all results for a given experiment or that all members of the laboratory use the same automated analysis software to reduce variability and minimize mouse usage.

Archiving

A final recommendation is for investigators to retain and store their void spot filter paper data as high-quality digital images. With appropriate annotation, these would then be available as a data resource that others could use to potentially reanalyze in different ways. At a time of increased awareness of the need for transparency and for creating shared scientific resources, we think that the raw data from these assays should be retained after the original experiments are concluded.

GRANTS

The study was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants P20-DK-097818, P20-DK-108276, R01-DK-078158, and U54-DK-104310 and National Institute of Environmental Sciences Grant R01-ES-001332. We also acknowledge the Aikens Center for Neurology Research for their support.

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.M.V. prepared figures; W.G.H., D.E.B., and C.M.V. drafted manuscript; W.G.H., M.L.Z., D.E.B., and C.M.V. edited and revised manuscript; W.G.H., M.L.Z., D.E.B., and C.M.V. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kyle A. Wegner for constructive comments in preparation of this article and Zunyi Wang for assistance with figures. We also thank the following Consensus meeting participants who by thoughtful discussion and criticism contributed to many of the ideas presented here: Richard Baldock, Maryanne Martone, Caroline Best, Matthew Fraser, Rosalyn Adam, Toby Chai, Maryrose Sullivan, Michelle Southard-Smith and Uzoma Anele. Special thanks also to the NIH program officers Deborah Hoshizaki, Ziya Kirkali, and Tamara Bavendam for organizing and convening the meeting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acevedo-Alvarez M, Yeh J, Alvarez-Lugo L, Lu M, Sukumar N, Hill WG, Chai TC. Mouse urothelial genes associated with voiding behavior changes after ovariectomy and bladder lipopolysaccharide exposure. Neurourol Urodyn In press. doi: 10.1002/nau.23592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackert-Bicknell CL, Anderson LC, Sheehan S, Hill WG, Chang B, Churchill GA, Chesler EJ, Korstanje R, Peters LL. Aging research using mouse models. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol 5: 95–133, 2015. doi: 10.1002/9780470942390.mo140195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bekkevold CM, Robertson KL, Reinhard MK, Battles AH, Rowland NE. Dehydration parameters and standards for laboratory mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 52: 233–239, 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biallosterski BT, Prickaerts J, Rahnama’i MS, de Wachter S, van Koeveringe GA, Meriaux C. Changes in voiding behavior in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 7: 160, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birder LA, Nakamura Y, Kiss S, Nealen ML, Barrick S, Kanai AJ, Wang E, Ruiz G, De Groat WC, Apodaca G, Watkins S, Caterina MJ. Altered urinary bladder function in mice lacking the vanilloid receptor TRPV1. Nat Neurosci 5: 856–860, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nn902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorling DE, Wang Z, Vezina CM, Ricke WA, Keil KP, Yu W, Guo L, Zeidel ML, Hill WG. Evaluation of voiding assays in mice: impact of genetic strains and sex. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F1369–F1378, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00072.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Zhang L, Hill WG, Yu W. Evaluating the voiding spot assay in mice: a simple method with complex environmental interactions. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 313: F1274–F1280, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00318.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornelissen LL, Misajet B, Brooks DP, Hicks A. Influence of genetic background and gender on bladder function in the mouse. Auton Neurosci 140: 53–58, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daly DM, Nocchi L, Liaskos M, McKay NG, Chapple C, Grundy D. Age-related changes in afferent pathways and urothelial function in the male mouse bladder. J Physiol 592: 537–549, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.262634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desjardins C, Maruniak JA, Bronson FH. Social rank in house mice: differentiation revealed by ultraviolet visualization of urinary marking patterns. Science 182: 939–941, 1973. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4115.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gershenfeld HK, Paul SM. Mapping quantitative trait loci for fear-like behaviors in mice. Genomics 46: 1–8, 1997. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gevaert T, Vriens J, Segal A, Everaerts W, Roskams T, Talavera K, Owsianik G, Liedtke W, Daelemans D, Dewachter I, Van Leuven F, Voets T, De Ridder D, Nilius B. Deletion of the transient receptor potential cation channel TRPV4 impairs murine bladder voiding. J Clin Invest 117: 3453–3462, 2007. doi: 10.1172/JCI31766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gharaee-Kermani M, Rodriguez-Nieves JA, Mehra R, Vezina CA, Sarma AV, Macoska JA. Obesity-induced diabetes and lower urinary tract fibrosis promote urinary voiding dysfunction in a mouse model. Prostate 73: 1123–1133, 2013. doi: 10.1002/pros.22662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo C, Kaneko S, Sun Y, Huang Y, Vlodavsky I, Li X, Li ZR, Li X. A mouse model of urofacial syndrome with dysfunctional urination. Hum Mol Genet 24: 1991–1999, 2015. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodges SJ, Zhou G, Deng FM, Aboushwareb T, Turner C, Andersson KE, Santago P, Case D, Sun TT, Christ GJ. Voiding pattern analysis as a surrogate for cystometric evaluation in uroplakin II knockout mice. J Urol 179: 2046–2051, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou XH, Hyun M, Taranda J, Huang KW, Todd E, Feng D, Atwater E, Croney D, Zeidel ML, Osten P, Sabatini BL. Central control circuit for context-dependent micturition. Cell 167: 73–86, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Y, Zhou W, Zhang Y. Bright lighting conditions during testing increase thigmotaxis and impair water maze performance in BALB/c mice. Behav Brain Res 226: 26–31, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurst JL. The functions of urine marking in a free-living population of house mice, Mus domesticus Rutty. Anim Behav 35: 1433–1442, 1987. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(87)80016-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iguchi N, Dönmez MI, Malykhina AP, Carrasco A Jr, Wilcox DT. Preventative effects of a HIF inhibitor, 17-DMAG, on partial bladder outlet obstruction-induced bladder dysfunction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 313: F1149–F1160, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00240.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalliokoski O, Jacobsen KR, Darusman HS, Henriksen T, Weimann A, Poulsen HE, Hau J, Abelson KS. Mice do not habituate to metabolism cage housing–a three week study of male BALB/c mice. PLoS One 8: e58460, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanasaki K, Yu W, von Bodungen M, Larigakis JD, Kanasaki M, Ayala de la Pena F, Kalluri R, Hill WG. Loss of β1-integrin from urothelium results in overactive bladder and incontinence in mice: a mechanosensory rather than structural phenotype. FASEB J 27: 1950–1961, 2013. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-223404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keil KP, Abler LL, Altmann HM, Bushman W, Marker PC, Li L, Ricke WA, Bjorling DE, Vezina CM. Influence of animal husbandry practices on void spot assay outcomes in C57BL/6J male mice. Neurourol Urodyn 35: 192–198, 2016. doi: 10.1002/nau.22692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keil KP, Abler LL, Altmann HM, Wang Z, Wang P, Ricke WA, Bjorling DE, Vezina CM. Impact of a folic acid-enriched diet on urinary tract function in mice treated with testosterone and estradiol. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F1431–F1443, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00674.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kvist SB, Selander RK. Maze-running and thigmotaxis in mice: applicability of models across the sexes. Scand J Psychol 33: 378–384, 1992. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1992.tb00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lehmann ML, Geddes CE, Lee JL, Herkenham M. Urine scent marking (USM): a novel test for depressive-like behavior and a predictor of stress resiliency in mice. PLoS One 8: e69822, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lumley LA, Sipos ML, Charles RC, Charles RF, Meyerhoff JL. Social stress effects on territorial marking and ultrasonic vocalizations in mice. Physiol Behav 67: 769–775, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(99)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mann EA, Alam Z, Hufgard JR, Mogle M, Williams MT, Vorhees CV, Reddy P. Chronic social defeat, but not restraint stress, alters bladder function in mice. Physiol Behav 150: 83–92, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maruniak JA, Owen K, Bronson FH, Desjardins C. Urinary marking in female house mice: effects of ovarian steroids, sex experience, and type of stimulus. Behav Biol 13: 211–217, 1975. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6773(75)91920-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maruniak JA, Owen K, Bronson FH, Desjardins C. Urinary marking in male house mice: responses to novel environmental and social stimuli. Physiol Behav 12: 1035–1039, 1974. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(74)90151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maruniak JA, Wysocki CJ, Taylor JA. Mediation of male mouse urine marking and aggression by the vomeronasal organ. Physiol Behav 37: 655–657, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Negoro H, Kanematsu A, Doi M, Suadicani SO, Matsuo M, Imamura M, Okinami T, Nishikawa N, Oura T, Matsui S, Seo K, Tainaka M, Urabe S, Kiyokage E, Todo T, Okamura H, Tabata Y, Ogawa O. Involvement of urinary bladder Connexin43 and the circadian clock in coordination of diurnal micturition rhythm. Nat Commun 3: 809, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicholson TM, Moses MA, Uchtmann KS, Keil KP, Bjorling DE, Vezina CM, Wood RW, Ricke WA. Estrogen receptor-α is a key mediator and therapeutic target for bladder complications of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 193: 722–729, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.08.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajandram R, Ong TA, Razack AH, MacIver B, Zeidel M, Yu W. Intact urothelial barrier function in a mouse model of ketamine-induced voiding dysfunction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F885–F894, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00483.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ricke WA, Lee CW, Clapper TR, Schneider AJ, Moore RW, Keil KP, Abler LL, Wynder JL, López Alvarado A, Beaubrun I, Vo J, Bauman TM, Ricke EA, Peterson RE, Vezina CM. In Utero and Lactational TCDD Exposure Increases Susceptibility to Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction in Adulthood. Toxicol Sci 150: 429–440, 2016. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ritter KE, Wang Z, Vezina CM, Bjorling DE, Southard-Smith EM. Serotonin receptor 5-HT3A affects development of bladder innervation and urinary bladder function. Front Neurosci 11: 690, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selander RK, Kvist SB. Open-field parameters and maze learning in aggressive and nonaggressive male mice. Percept Mot Skills 73: 811–824, 1991. doi: 10.2466/pms.1991.73.3.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simon P, Dupuis R, Costentin J. Thigmotaxis as an index of anxiety in mice. Influence of dopaminergic transmissions. Behav Brain Res 61: 59–64, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stechman MJ, Ahmad BN, Loh NY, Reed AA, Stewart M, Wells S, Hough T, Bentley L, Cox RD, Brown SD, Thakker RV. Establishing normal plasma and 24-hour urinary biochemistry ranges in C3H, BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice following acclimatization in metabolic cages. Lab Anim 44: 218–225, 2010. doi: 10.1258/la.2010.009128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart FA, Lundbeck F, Oussoren Y, Luts A. Acute and late radiation damage in mouse bladder: a comparison of urination frequency and cystometry. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 21: 1211–1219, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90278-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart FA, Michael BD, Denekamp J. Late radiation damage in the mouse bladder as measured by increased urination frequency. Radiat Res 75: 649–659, 1978. doi: 10.2307/3574851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugino Y, Kanematsu A, Hayashi Y, Haga H, Yoshimura N, Yoshimura K, Ogawa O. Voided stain on paper method for analysis of mouse urination. Neurourol Urodyn 27: 548–552, 2008. doi: 10.1002/nau.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walf AA, Frye CA. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nat Protoc 2: 322–328, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wegner KA, Abler LL, Oakes SR, Mehta GS, Ritter KE, Hill WG, Zwaans BM, Lamb LE, Wang Z, Bjorling DE, Ricke WA, Macoska J, Marker PC, Southard-Smith EM, Eliceiri KW, Vezina CM. Void spot assay procedural optimization and software for rapid and objective quantification of rodent voiding function, including overlapping urine spots. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F1067–F1080, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00245.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu MV, Manoli DS, Fraser EJ, Coats JK, Tollkuhn J, Honda S, Harada N, Shah NM. Estrogen masculinizes neural pathways and sex-specific behaviors. Cell 139: 61–72, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu W, Ackert-Bicknell C, Larigakis JD, MacIver B, Steers WD, Churchill GA, Hill WG, Zeidel ML. Spontaneous voiding by mice reveals strain-specific lower urinary tract function to be a quantitative genetic trait. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F1296–F1307, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00074.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu W, Hill WG, Robson SC, Zeidel ML. Role of P2X4 receptor in mouse voiding function. Sci Rep 8: 1838, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20216-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]