Abstract

Diet and exercise before and during pregnancy affect the course of the pregnancy, the childʼs development and the short- and long-term health of mother and child. The Healthy Start – Young Family Network has updated the recommendations on nutrition in pregnancy that first appeared in 2012 and supplemented them with recommendations on a preconception lifestyle. The recommendations address body weight before conception, weight gain in pregnancy, energy and nutritional requirements and diet (including a vegetarian/vegan diet), the supplements folic acid/folate, iodine, iron and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), protection against food-borne illnesses, physical activity before and during pregnancy, alcohol, smoking, caffeinated drinks, oral and dental hygiene and the use of medicinal products. Preparation for breast-feeding is recommended already during pregnancy. Vaccination recommendations for women planning a pregnancy are also included. These practical recommendations of the Germany-wide Healthy Start – Young Family Network are intended to assist all professional groups that counsel women and couples wishing to have children and during pregnancy with uniform, scientifically-based and practical information.

Key words: pregnancy, lifestyle, preconception, nutrition, physical activity

Zusammenfassung

Ernährung und Bewegung vor und während der Schwangerschaft wirken sich auf den Schwangerschaftsverlauf, die Entwicklung des Kindes und die kurz- und langfristige Gesundheit von Mutter und Kind aus. Das Netzwerk Gesund ins Leben hat die 2012 erstmals erschienenen Empfehlungen zur Ernährung in der Schwangerschaft aktualisiert und um Empfehlungen zum präkonzeptionellen Lebensstil ergänzt. Die Empfehlungen adressieren das Körpergewicht vor der Konzeption, die Gewichtsentwicklung in der Schwangerschaft, Energie- und Nährstoffbedarf sowie Ernährungsweise (inklusive vegetarische/vegane Ernährung), die Supplemente Folsäure/Folat, Jod, Eisen und Docosahexaensäure (DHA), den Schutz vor Lebensmittelinfektionen, körperliche Aktivität vor und in der Schwangerschaft, Alkohol, Rauchen, koffeinhaltige Getränke, Mund- und Zahngesundheit und den Umgang mit Arzneimitteln. Die Vorbereitung auf das Stillen wird bereits in der Schwangerschaft empfohlen. Für Frauen, die eine Schwangerschaft planen, sind zudem Impfempfehlungen enthalten. Diese Handlungsempfehlungen des bundesweiten Netzwerks Gesund ins Leben sollen alle Berufsgruppen, die Frauen und Paare mit Kinderwunsch und in der Schwangerschaft beraten, mit harmonisierten, wissenschaftsbasierten und anwendungsorientierten Informationen unterstützen.

Schlüsselwörter: Schwangerschaft, Lebensstil, Präkonzeption, Ernährung, Bewegung

Introduction

The first 1000 days post conception are regarded as a sensitive window of time that can define the childʼs health and in which the risk of later non-transmissible diseases can be modified 1 . The importance of a healthy lifestyle with a balanced diet and exercise in this phase of life is an important building block for the prevention of these diseases and is underlined by, amongst others, the national health goal “Before and after birth” of 2017 2 .

In Germany, about a third of women of childbearing age are overweight or obese 5 . Obesity reduces the likelihood of conception 6 and is associated, amongst others, with a higher risk of pregnancy and birth complications, birth defects, premature births and miscarriages, a high infant birth weight and later obesity of the child 6 , 7 . In 2014/15 gestational diabetes was diagnosed in 13% of pregnant women during a screening programme 8 . About 11% of mothers of 0- to 6-year-old children reported in the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS) that they had smoked during pregnancy 11 . It is estimated that about 0.2 – 8 out of 1000 neonates in Germany are born annually with fetal alcohol syndrome. Far more children are affected by a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder 12 .

A healthy lifestyle prevents risks of pregnancy complications and helps maintain the health of mother and child. In this phase of life in particular expectant parents 1 are often highly motivated to optimise their lifestyle and are receptive to appropriate recommendations. Women and couples wishing to have children are less aware that their lifestyle affects fertility, the course of the pregnancy and also the childʼs later health.

The recommendations of the Healthy Start – Young Family Network (Netzwerk Gesund ins Leben) are intended to help contribute to a health-promoting lifestyle and thus to promote the health of mothers and children and prevent long-term overweight and its associated diseases. In 2012 the Germany-wide Practical Recommendations for Nutrition in Pregnancy of the Healthy Start – Young Family Network were first published 13 . The updated version presented here has been extended to include recommendations covering the period before pregnancy and around the time of conception.

They are intended to provide gynaecologists, midwives, paediatricians and members of other health professions with a basis for counselling a healthy lifestyle.

Healthy Start – Young Family is a network of institutions, learned societies and associations that are concerned with young families. The aim is to provide parents with uniform messages about nutrition and exercise so that they and their children live healthy lives and grow up healthy.

The Healthy Start – Young Family Network is part of the IN FORM initiative and is accommodated in the Federal Centre for Nutrition (BZfE), an institution that comes within the sphere of responsibility of the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL).

Methods

For the update of the recommendations on nutrition in pregnancy 13 and the extension to include recommendations for women wishing to have children, in 2017 the recommendations of national and international learned organisations and institutions were searched for statements on the diet, exercise, lifestyle and health of pregnant women and those wishing to have children and examined for their topicality.

In addition, literature searches were undertaken in PubMed, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar 2 and meta-analyses, systematic reviews, guidelines and relevant publications published between 2012 and mid-2017 were assessed by the members of the scientific council (cf. list of authors). In addition, aspects of lifestyle before conception, physical activity before and during pregnancy and weight recommendations for pregnancy were discussed in working groups with other acknowledged experts and practitioners (see page 1274) from the appropriate specialist disciplines. On this basis, the present recommendations were formulated by consensus by the scientific council. A more wide-ranging systematic literature search and evidence assessment was not undertaken because of the lack of financial resources for this. The key statements formulated correspond to the evidence level of an expert recommendation with particular regard to aggregated sources of evidence. Their wording is based on that used in guidelines. Thus, “must” refers to a strong recommendation (German “soll”), “should” to a moderately strong recommendation (German “sollte”) and “can” to an open recommendation (German “kann”). The respective “Bases of the recommendations” sections make it apparent how these were derived.

These practical recommendations have been reviewed and endorsed by the boards of the following associations: Professional Association of German Gynaecologists (BVF), the German Association of Midwives (DHV), the Professional Association of Paediatricians (BVKJ); and the following scientific societies: German Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine), German Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (DGGG), German Society for Sport Medicine and Prevention (DGSP), German Society of Midwifery Science (DGHWi) and German Society for Nutrition (DGE).

General Recommendation

Recommendation.

Professional groups who care for women of childbearing age, particularly women with a concrete wish to have children, as well as pregnant women must encourage and counsel them to follow a balanced diet, physical activity and a healthy lifestyle.

Women/couples wishing to have children and expectant parents are frequently unaware that they can exert a long-term effect not only on their own health but also on that of their children through their nutrition and their lifestyle 3 , 4 , 14 . The lifestyle of a future family is influenced by both partners. Professionals must inform women of childbearing age and their partners, women/couples wishing to have children and expectant parents of the long-term importance of a healthy lifestyle and know that a third of pregnancies are unplanned or are not planned for that particular time 15 .

Body Weight Before Conception and Weight Gain in Pregnancy

Recommendations.

Even before pregnancy, the optimal adjustment of body weight to a normal weight is desirable.

An appropriate weight gain in pregnancy is between about 10 and 16 kg for women of normal weight.

In the case of overweight and obese women, a lower weight gain in pregnancy is desirable.

In underweight women, it should be ensured that there is sufficient weight gain during pregnancy.

Bases of the recommendations

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews underline the fact that both women who are overweight and those who are underweight before conception have a higher health risk than those with normal weight 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 . The recommendation that women should adjust their body weight before pregnancy to that approaching a more normal weight is consistent with international 4 and national recommendations 21 , 22 .

A weight gain of between 10 and 16 kg is associated with a low risk of fetal and maternal complications in women of normal weight 25 , 26 , 27 . The risk increases with a higher weight gain 28 , particularly if the woman is overweight or obese when embarking on pregnancy 29 . Therefore a weight gain of about 10 kg is regarded as sufficient for overweight and obese women. A general recommendation for a minimum weight gain in underweight women cannot be given. Overall, the evidence is too inconsistent to define exact upper and lower limits for a desirable weight gain in pregnancy according to preconceptual body mass index (BMI). Internationally there is no consensus on the recommendations for weight gain in pregnancy, particularly for overweight and obese women 30 , 31 .

Background information

In Germany, 30% of 18- to 29-year-old women, 38% of 30- to 39-year-olds and 46% of 40- to 49-year-olds are overweight or obese (DEGS1) 5 . Only up to about 4.5% of women in these age groups are underweight 5 . Overweight/obesity before pregnancy and also high weight gain in pregnancy (frequently defined as weight gain above the recommendation of the Institute of Medicine [IOM], see below) were associated in observational studies with an increased occurrence of gestational diabetes, hypertension and birth complications 16 , 18 , 19 , fetal macrosomia 20 , large for gestational age (LGA) and later overweight of the child and associated complications 19 , 32 , 33 , 34 . Maternal overweight and obesity at the beginning of pregnancy are associated with a shorter life expectancy of the child 35 . Underweight in pregnancy was associated with more frequent premature births, miscarriages and low birth weight 17 , 36 , 37 , 38 . It is therefore desirable for both overweight and underweight women to approximate to normal weight before pregnancy. Weight gain in pregnancy is characterised by high variability 23 , 24 and has a lower predictive significance than BMI at the beginning of pregnancy.

For women who are obese, even a weight loss of 5 to 10% of the starting weight before pregnancy can have a significantly positive effect on health and also increase the chance of becoming pregnant 22 . The therapeutic measures (if necessary including bariatric surgery) that may be considered for weight reduction in severely obese women in preparation for a pregnancy must be decided individually in a medical consultation on the basis of current scientific findings and guidelines 39 , 40 , 41 .

Pronounced weight gain normally does not occur until the second trimester of pregnancy. Pregnant women should be informed of the causes of weight gain and the risks of obesity or excessive weight gain. Weight loss diets in pregnancy are not recommended because of safety concerns.

The American Institute of Medicine (IOM) 27 recommends a different weight gain for pregnant women according to BMI at the beginning of pregnancy 27 . These recommendations are based on epidemiological association studies in American and Danish women. The recommendations have been adopted by some countries such as Italy, Denmark and Switzerland, in some cases with slight adjustments. As the weight ranges recommended by the IOM could not be confirmed in other international 42 and national epidemiological studies 24 , 43 and could not be substantiated by the results of a few interventional studies on a change of lifestyle in normal and overweight/obese women 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , their use in everyday clinical practice is not recommended here and by other expert groups 13 , 22 (cf. also Suppl. Table S1 ).

The increased risk of later overweight in the child as a result of a high maternal weight gain in pregnancy is also discussed, but the weight gain during pregnancy has less effect on the risk of overweight and the childʼs health than the baseline weight of the mother in particular 48 , 49 , 50 .

Energy and Nutritional Requirements in Pregnancy

Recommendations.

Pregnant women should pay particular attention to the quality of their diet. Compared to the energy requirement, the requirement for individual vitamins and minerals/trace elements increases much more in pregnancy.

Energy requirements increase only slightly over the course of pregnancy. Pregnant women should increase their energy intake only slightly (up to about 10%) and not until the last few months of pregnancy.

Basis of the recommendations

The recommendations take account of the mathematically determined increase in energy requirements, which is the basis of international and national reference values 4 , 25 , 51 , 52 , and the usually markedly reduced physical activity, particularly in the third trimester 53 .

Background information

A high-calorie diet can have a detrimental effect on the course of pregnancy and on the childʼs health 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 . Pregnant women often overestimate their actual increase in energy requirement. Energy consumption increases in particular due to the energy requirement for tissue formation and fetal growth. Purely mathematically, there is an additional energy requirement of 76 530 kcal for a woman of normal weight and a weight gain in pregnancy of 12 kg 58 . From this is derived the guideline value of the German Nutrition Society (DGE) for an additional energy intake of 250 kg kcal/day in the second trimester and 500 kcal/day in the third trimester with unchanged physical activity 52 . However, physical activity usually declines considerably 59 , 60 , so that in many women an increased energy intake is not required.

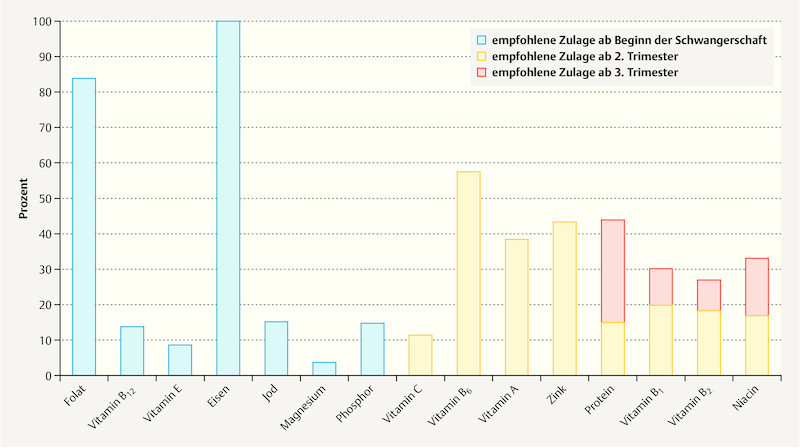

The requirement for a series of vitamins and minerals increases in pregnancy much more than the energy requirement, mainly from the 4th month onwards 61 . For the nutrients folate and iodine a markedly increased intake is recommended from the beginning or even before pregnancy 52 . Recommended additional intake of various nutrients are indicated in Fig. 1 . With the exception of folate and iodine 52 (see section Supplements), the increased requirement for vitamins and minerals can usually be covered by a suitable choice of food. The consumption of supplements cannot replace a balanced diet. During counselling the concept of “think for two but do not eat for two (do not eat double portions)” should be emphasised and illustrated by examples of foods with high nutrient densities (vegetables, fruit, wholegrain products, dairy products, etc.).

Fig. 1.

Reference nutrient values – Recommended additional intake in pregnancy according to German Nutrition Society (DGE), expressed as a percentage of the reference value 52 .

Nutrition

Recommendations.

The diet must be balanced and varied before and during pregnancy. It should be based on the general recommendations for healthy adults.

-

In a balanced diet, the food groups should be weighted differently:

Both calorie-free beverages and plant-based foods (vegetables, fruit, pulses, wholegrain products) should be consumed abundantly.

Animal-based foods (milk and dairy products, low-fat meat and low-fat meat products, oily sea fish and eggs) should be eaten moderately.

Sweets, sugar-containing beverages and snacks as well as fats with a high proportion of saturated fatty acids (in particular animal fats) and oils should be only consumed sparingly. Plant oils (e.g. rapeseed and olive oil) should be preferred as sources of fat.

Bases of the recommendations

International 4 , 19 and national 52 , 62 learned societies and institutions give recommendations for a balanced and varied diet before and during pregnancy that are based on the general recommendations for adults 52 , 63 . The data are insufficient to allow special nutritional recommendations to be formulated, e.g. for improving fertility 64 . There is no robust evidence for particular diets or for preferring certain macronutrients (proteins, carbohydrates, fats) for weight loss or for the avoidance of excessive weight gain in pregnancy 57 , 65 .

Background information

A balanced diet and regular physical activity before and during pregnancy not only have a positive short-term effect on the course of pregnancy and the development of the unborn child, but also have positive long-term effects on the health and well-being of mother and child 1 , 4 , 66 . A systematic review showed that weight gain and the risk of pre-eclampsia can be reduced by diet and lifestyle interventions in pregnancy (in normal-weight, overweight and obese women), in addition to which a non-significant trend to reduction of gestational diabetes, hypertension, premature births and intrauterine death was observed 67 . In an interventional study in overweight pregnant women with an increased risk of gestational diabetes, appropriate weight gain and a lesser decline in physical activity in early pregnancy was achieved through repeated healthy eating and physical activity messages 68 . No reduction in gestational diabetes was obtained with other lifestyle interventions in obese pregnant women 65 . Although the data are inconsistent, nutrition and exercise should be addressed repeatedly when counselling pregnant women.

In a meta-analysis of 11 randomised interventional studies (1985 pregnant women, mean BMI 21.5 – 32.4 kg/m 2 ), a diet with a low glycaemic index was associated with lower blood glucose concentrations in the women (fasting and 2 hours postprandially) and a lower risk of large for gestational age (LGA) infants than a diet with a higher glycaemic index 69 . A systematic review of observational studies showed a lower risk of gestational diabetes with a diet with a high intake of vegetables, fruit, wholegrain products, nuts, pulses and fish; by contrast, a diet rich in fat, a large amount of red meat and eggs was associated with a higher risk 9 .

Because of the physiological changes and the growth of the uterus (the stomach and intestine are compressed), smaller meals divided over the day can promote the well-being of the expectant mother.

With a balanced diet, the food groups can be divided according to the recommended frequencies and amounts of consumption into “abundant”, “moderate” and “sparing”. Foods with a high nutrient density (high content of essential nutrients relative to their energy content) are required for sufficient amounts of vitamins and minerals to be absorbed despite the only slight increase in energy requirement. With the nutrients folate and iodine, the increased requirement could theoretically be covered by a very specific choice of food 70 , although in practice this is rarely achieved (see section “Supplements”).

A guideline value for the daily amount of water for the general population and also during pregnancy is about 1.5 L 52 . In hot environments or during heavy physical activity, a larger amount of water is required.

The daily consumption of at least three portions of vegetables and two portions of fruit is desirable 63 . Cereal products, particularly from wholegrain cereals, and potatoes are rich in vitamins, minerals and fibre. Milk and dairy products, which provide protein, calcium and iodine, are important components of a balanced diet. Fish is an important source of vitamin B 12 , zinc and iron. A preference for certain types of meat is not necessary for an adequate iron intake, but low-fat meat and meat products should be chosen specifically.

Through the weekly consumption of fish, particularly one portion of oily sea fish (e.g. mackerel, herring or sardines), it is possible to achieve the additionally recommended quantity of the long-chain omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) of at least 200 mg/day in pregnancy (for fish/DHA in relation to allergy prevention, see section “Nutrition for the prevention of allergies in the child”). A high consumption of carnivorous fish (e.g. tuna, swordfish), which are at the end of the maritime food chain and may contain a high content of toxic substances, should be avoided for reasons of preventive health care in pregnancy 52 , 71 . The regular consumption of sea fish as well as iodised salt contributes to the supply of iodine. However, salt should be used sparingly.

Vegetarian and Vegan Diet in Pregnancy

Recommendations.

A balanced vegetarian diet with the consumption of milk, dairy products and eggs (ovo-lacto vegetarianism) can in principle cover most nutrient needs even during pregnancy. Specific counselling is recommended.

In the case of a purely plant-based (vegan) diet, the supply of critical nutrients must be checked by a physician and individual nutritional counselling given. As well as iodine and folic acid, additional micronutrient supplementation (particularly vitamin B 12 ) is required to prevent a nutrient deficiency and subsequent damage to the childʼs development.

Bases of the recommendations

The study data on vegetarian and vegan diets in pregnancy is sparse and in some cases contradictory 72 . The recommendations are therefore based on the general recommendations for an ovo-lacto vegetarian diet with due regard to the “critical” nutrients in pregnancy 62 , 73 . An undersupply of vitamin B 12 occurring after many years of a vegan diet without supplementation can lead to severe and long-lasting damage to the childʼs nervous system as well as haematological and neurological problems for the mother during pregnancy 74 , 75 , 76 .

Background information

Sufficient nutrient intake is possible in pregnancy with a balanced and consciously designed ovo-lacto vegetarian diet, with the exception of the nutrients folic acid and iodine (and in some cases DHA), which generally need to be supplemented during pregnancy.

Milk and dairy products, eggs, pulses and cereal products usually provide sufficient protein intake. The risk of insufficient iron intake is increased for ovo-lacto vegetarians 77 , 78 . Pulses, (wholegrain) cereal products and some types of vegetable contain reasonably large quantities of iron, although less readily available than iron from meat and fish. The concomitant consumption of vitamin C-rich foods (e.g. citrus fruits, peppers) can improve iron intake. Depending on the medically determined iron status, iron may be supplemented if necessary (see section “Supplements”). Critical nutrients for pregnant women following a vegetarian diet for a long time even before they became pregnant include vitamin B 12 , DHA and possibly zinc 74 , 77 , 79 , 80 .

With a purely plant-based (vegan) diet, intake of vitamin B 12 , DHA, zinc, protein, iron, calcium and iodine is critical. In particular, adequate intake of vitamin B 12 is not possible with a purely plant-based diet without nutritional supplements and fortified foods. Vegans who wish to keep to their diet in pregnancy should undergo qualified nutritional counselling as soon as they wish to have children in order to eliminate any nutritional deficiencies before conception. Vegans should have their intake of critical nutrients regularly checked medically during pregnancy as well, so that they can take specific supplements and where necessary consume fortified foods to cover their nutrient requirement 73 .

Supplements

Folic acid supplement

Recommendations.

In addition to a balanced diet, women planning a pregnancy must take 400 µg of folic acid daily or equivalent doses of other folates in the form of a supplement.

Supplementation must begin at least four weeks before conception and continue until the end of the first trimester of pregnancy.

Women who start folic acid supplementation less than 4 weeks before conception should use higher-dosed products.

Bases of the recommendations

It has been found in numerous epidemiological studies and meta-analyses based on these studies that periconceptual folic acid supplementation of 400 µg/day (alone or in combination with other micronutrients) can reduce the risk of birth defects of the nervous system (neural tube defects; NTD) (e.g. 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 ). In Germany and many other countries it has therefore been recommended since about the middle of the 1990s that, in addition to a folate-rich diet, women who want to or could become pregnant should take 400 µg of folic acid daily or equivalent doses of other folates (calcium L-methylfolate or 5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid glucosamine) in the form of supplements and continue the supplementation also in the first trimester of pregnancy 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 . In some countries the dose recommendation is somewhat higher, e.g. 500 µg daily in Australia 91 . If intake begins only shortly before or even after conception, supplements of 800 µg folic acid should be used 92 , 93 in order to reach the red blood cell folate concentrations recommended by the WHO more rapidly 94 .

Background information

Folate is important for cell division and growth processes, amongst others. Consumption of folate-rich plant nutrients such as greens, cabbages, pulses, wholegrain products, tomatoes or oranges can contribute to the supply of folate. According to the German National Nutrition Survey (NVS II), the median intake of folate equivalents in women of reproductive age is between 153 and 185 µg/day 95 and thus markedly below the German, Austrian and Swiss reference values for nutrient intake derived for adults (300 µg/day) and pregnant women (550 µg/day) 52 . In the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1), serum and red blood cell folate concentrations were for the first time measured representatively for the adult population. The results of this study give rise to the conclusion that 85% of the population reaches the target folate values for non-pregnant women 96 . However, fewer than 5% of women of reproductive age reach the red blood cell folate concentration of 400 ng/mL (906 nmol/L) recommended by the WHO for effective risk reduction of neural tube defects 94 , 96 .

As closure of the neural tube normally occurs within 3 to 4 weeks of conception, folic acid supplementation must be started prior even to conception for the greatest possible risk reduction of neural tube defects. The time interval until the recommended folate concentration is reached is dependent on the baseline concentration and the supplemented dose: thus, with a daily intake of 400 µg of folic acid, 6 to 8 weeks are needed to reach a red blood cell folate concentration of 906 nmol/L; with an intake of 800 µg/day, however, only about 4 weeks are required 92 , 93 , 97 . A daily intake of 1000 µg folic acid/day is considered safe (tolerable upper intake level) 98 , 99 .

Currently only a small proportion of women in Germany take a preventive folic acid supplement. Admittedly almost 90% of women take a folic acid supplement in pregnancy 100 , but only about 10 to 34% begin at the recommended time and use a dose of at least 400 µg/day 101 , 102 , 103 . In Germany, dosage forms in different doses are available. If women take a multivitamin product purely for NTD prevention, it should be ensured that this contains at least 400 µg of folic acid.

Iodine supplement

Recommendation.

In addition to a balanced diet, pregnant women must take a daily supplement of 100 (up to 150) µg iodine. Women with thyroid disorders must consult their physician before supplementation.

Bases of the recommendation

According to WHO criteria 104 , Germany is an area with a mild to moderate iodine deficiency. The median iodine intake in women of reproductive age (calculated from iodine excretion in the 24-hour urine) according to the DEGS study was about 125 µg/day 105 . Thus, the median value did not reach either the reference intake for adult women of 200 µg/day 52 or the higher recommended intake of the German Nutrition Society for pregnant women of 230 µg/day 52 . A supplement with a dose of 100 to 150 µg daily appears sufficient to achieve the recommended intake for pregnancy. The dose equates to the lower to middle end of the range for iodine supplementation in pregnancy mentioned in the maternity guidelines and regarded as safe (100 to 200 µg/day) 106 . It is comparable to the recommendations of international bodies 107 , 108 , 109 .

Background information

Women wishing to have children should be counselled about the importance of iodine even before pregnancy. Consideration should be given to an adequate iodine intake. The use of iodised cooking salt and the regular consumption of milk, dairy products and sea fish are worth recommending (see also section “Nutrition”). In terms of foodstuffs (e.g. bread), products with iodised table salt should be chosen out of preference. Women with thyroid disorders should be given medical advice and also avoid iodine deficiency. In women with Hashimotoʼs thyroiditis, the required level of iodine intake (through iodised salt, foods with added iodised salt, fish, etc.) is usually unproblematic.

In pregnancy, the iodine requirement increases due to the increased maternal production of thyroid hormones and increased renal excretion, but also due to the requirement for the unborn childʼs development (placental transfer). In total, an increased iodine requirement of about 30 to 50 µg/day is assumed 52 , 110 . Accordingly, the reference value derived by the German, Austrian and Swiss societies for iodine intake increases from 200 µg to 230 µg/day 52 . Based on an adequate intake value of 150 µg/day for non-pregnant women, the EFSA recommends an intake of 200 µg/day in pregnancy 110 . If products with 100 to 150 µg iodine are already being taken, additional iodine supplements should not be taken.

A series of epidemiological studies indicate that even a moderate undersupply of iodine, particularly in early pregnancy, or a deficiency of thyroid hormones (hypothyroxinaemia) during this period can have an unfavourable effect on the childʼs cognitive and psychomotor development 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 . The few studies in which the effects on pregnancy of iodine supplementation in moderate iodine deficiency have been investigated 114 , 116 , 118 , 119 , 120 indicate that the mother also benefits from iodine supplementation and has a lower risk of developing hypothyroidism after the birth.

The iodine content in sea algae, particularly in dried algae and seaweed products, can vary considerably and in some cases be very high. Thus, even with small dietary quantities of algae/products, as well as when taking several iodised nutritional supplements, there may be an increased iodine intake 121 , 122 . In addition, algae can be rich in arsenic and other contaminants 122 . The consumption of algae and algal products is therefore discouraged.

Other supplements

Recommendations.

Iron supplements in addition to a balanced diet should only be taken after a medically diagnosed deficiency.

Pregnant women who do not consume oily sea fish regularly are recommended to take DHA supplements.

Bases of the recommendations

Iron supplementation in pregnancy improves maternal status and protects against anaemia; however, as regards the benefit to the child of general supplementation of all pregnant women, the data are inconclusive 123 , 124 , 125 . In addition, there is evidence that additional iron intake in well-supplied pregnant women can increase the risk of premature births and low birth weight 126 , 127 . Against this background, general prophylactic iron supplementation is not recommended for pregnant women in Germany. This is consistent with recommendations of other European countries (e.g. UK 128 , France 129 and Ireland 130 . On the other hand, routine supplementation of iron in combination with folic acid is recommended internationally by the WHO in pregnancy since in some developing countries there is a considerable proportion of pregnant women who have iron deficiency anaemia 4 , 19 , 131 .

The omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is found in particular in oily sea fish. Pregnant women who abstain from these foods should take supplements with DHA to achieve the recommended intake amount in the German, Austrian and Swiss reference values of at least 200 mg DHA daily on average 52 or the additional intake recommended by the EFSA in pregnancy of 100 to 200 mg DHA, in addition to the recommended intake for non-pregnant women of 250 mg DHA daily plus eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) 132 , 133 .

Background information

Iron deficiency in pregnancy increases the risk of premature birth and low birth weight 126 , 134 , 135 . The iron requirement increases in pregnancy because more iron is required for the fetus, placenta and the 20% increase in red blood cells in the expectant mother. Pregnant women should therefore ensure a sufficient intake of iron-rich foodstuffs.

The reference value for iron intake in pregnancy in Germany of 30 mg/day is 100% higher than that for non-pregnant women 52 . According to NVS II, women of childbearing age (18 to 49 years) consume a median of 11 to 12 mg iron per day 95 . These data indicate that the generally recommended intake amount in the normal diet is not reached. However, menstrual blood loss ceases 52 and intestinal iron absorption increases in pregnancy. Therefore, the EFSA, for example 136 , assumes an equally high dietary iron requirement for pregnant women as for non-pregnant women. As well as determinations of Hb, the additional determination of serum ferritin 137 in the context of antenatal care is useful in obtaining evidence of insufficient or empty iron stores 106 .

Vegetarians have a small intake of DHA and have a lower DHA status than women who also consume fish, meat and eggs 138 . The alpha-linoleic acid (ALA) contained in some vegetable oils (e.g. rapeseed, walnut, linseed oil), nuts and seeds (e.g. walnuts) can provide a contribution to the supply of omega-3 fatty acid; however, endogenous synthesis of DHA from ALA is low 138 , 139 , 140 , 141 , 142 , 143 , 144 . Women who do not (regularly) consume oily sea fish should therefore take DHA as a supplement during pregnancy.

In randomised controlled trials, supplementation with fish oil or long-chain omega-3 fatty acids such as DHA resulted in a significant reduction in the risk for early premature births up to 34 weeks of pregnancy 145 , 146 , 147 . DHA is important for the development of visual function and brain in the fetus 148 . In some observational studies, the consumption of fish and the supply of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids in pregnancy were associated with a more favourable childhood development of cognitive and other abilities 149 , 150 , 151 , 152 , 153 . Other studies fail to confirm this 154 , 155 . Data on the benefit of DHA supplements in pregnancy for the childʼs cognitive development are inconsistent.

The vitamin D supplied to the expectant mother exerts an effect on fetal vitamin D supply and infant bone mineralisation 156 , 157 , 158 . Vitamin D is formed in particular in the skin during exposure to sunlight. Thus, a supply of vitamin D can be guaranteed by spending a regular amount of time outdoors. For light skin types, it is sufficient in the summer months in our latitudes to expose the unprotected face and arms to the sun for about 5 to 10 minutes daily in the midday period. Sunburn should be avoided at all costs. In the absence of endogenous vitamin D synthesis, i.e. in periods of low sunlight and with a predominantly indoor existence, the German Nutrition Society recommends a vitamin D intake of 20 µg (800 IU) daily for pregnant women (as for all other groups of people from infancy onwards) 52 . The average amount of vitamin D absorbed from the diet is only 2 to 4 µg daily 95 . This is insufficient to achieve a sufficient intake with limited exposure to sunlight and low endogenous vitamin D synthesis throughout the year. Pregnant women who rarely spend time in the sun or extensively cover their skin or use sunscreen lotions on exposure to the sun as well as women with dark skin types should therefore use a supplement with vitamin D 52 .

Protection against Food-Borne Illnesses During Pregnancy

Recommendations.

Pregnant women must avoid raw, animal-based foods. In addition, they should follow the recommendations to avoid listeriosis and toxoplasmosis in the choice, storage and preparation of foods.

Pregnant women must only eat eggs if the yolk and egg white are firm from being heated.

Bases of the recommendations

Recommendations on the choice, preparation and storage of foods are summarised in the information sheet published in 2017 “Listeriosis and toxoplasmosis. Safe eating during pregnancy” from the Federal Centre for Nutrition 161 (order no. 0346, www.ble-medienservice.de ). They are based on data from zoonosis monitoring and other communications from the Federal States on the presence of zoonosis pathogens in foodstuffs studied and study results of food-related disease outbreaks, literature analyses and expert opinions as well as from members of the Committee for Biological Hazards and Hygiene at the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment. As salmonellosis can be harmful to mother and child, eggs should be consumed only when cooked thoroughly.

Background information

The pathogens of listeriosis and toxoplasmosis can be transmitted to the placenta and the unborn child during pregnancy and cause severe illnesses as well as premature births and stillbirths 159 , 160 . Each year about 20 to 40 cases of neonatal listeriosis and about 5 to 40 cases of congenital toxoplasmosis in neonates 162 , 163 are reported to the Robert Koch Institute ( www.rki.de ), but the reporting system only covers laboratory-confirmed cases. A national seroprevalence study estimates there to be 345 cases of congenital toxoplasmosis annually in Germany 164 .

In the case of toxoplasmosis, the consumption of raw meat from pigs, lambs, sheep and game as well as of meat that is not fully cooked (including in the form of raw sausage meat such as salami or raw ham) is particularly problematical 160 , 165 , 166 .

Raw meat products, smoked fish and soft cheeses (including those made from heat-treated milk such as Gorgonzola) have a high risk of containing pathogenic listeria; raw milk and derived products as well as vegetables and salads may also be affected 159 , 167 , 168 , 169 , 170 . Listeria can also be found in heated foods. It can also proliferate at refrigerator temperatures as well as in products packaged under vacuum or in a controlled atmosphere.

Pregnant women should prepare their food as close as possible to the time of consumption and consume it rapidly. In restaurants and cafeterias they should where possible consume food that has been heated immediately prior to consumption. As well as choice of foods, hygiene in storage and preparation plays an important role in protecting against food-borne illnesses.

Exercise Before and During Pregnancy

Recommendations.

Women who are planning a pregnancy and pregnant women must follow the general exercise recommendations for adults.

Women must also be physically active in everyday life during pregnancy and must limit or regularly interrupt sedentary activities.

Pregnant women should be moderately physically active for at least 30 minutes at least 5 days a week and preferably daily. Moderately active means that conversation is still possible during sporting activity (talk test).

Women who engage in sport can also be more intensively physically active in pregnancy.

Bases of the recommendations

The recommendations are based on recommendations by other learned societies and expert groups such as the National Recommendations for Physical Activity and Physical Activity Promotion 53 , 171 , 172 , 173 , 174 , 175 .

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of randomised controlled interventional studies as well as observational studies suggest that moderate physical activity during pregnancy is not only safe for the pregnant woman and the child 176 , 177 , but also produces a variety of positive effects. Thus exercise/sport during pregnancy is associated with a reduced risk of LGA 178 , 179 , premature birth 177 , 180 , 181 , caesarean section 44 , 176 , 182 , 183 , gestational diabetes 10 , 47 , 176 , 177 , 178 , 184 , pregnancy-induced hypertension 176 , 183 , excessive weight gain 44 , 178 , 185 , 186 , incontinence 187 , 188 , back pain 189 , 190 and improved psychosocial well-being 53 . Data findings focused exclusively on overweight and obese pregnant women are not quite so extensive. In summary, in this respect a risk reduction has been demonstrated for premature birth, gestational diabetes and excessive weight gain by the practice of physical activity as part of a lifestyle intervention in pregnancy 44 , 177 .

Background information

The recommendations on the level of activity of 30 minutes of physical activity on at least 5 days a week are documented by the improvement in cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness and the prevention of noncommunicable diseases 191 . In terms of pregnancy-specific aspects, the evidence for certain levels and intensities of activity is limited; generally, however, in a complication-free pregnancy the positive effect of exercise on the course of the pregnancy and the health of mother and child is undisputed 192 .

For pregnant women, aerobic endurance activity is particularly recommended and should be undertaken at moderate intensity 193 and in exercise units of at least 10 minutes. Moderate intensity means the exercise is experienced as slightly strenuous and conversation is possible (talk test). Physical activity in everyday life is also desirable, e.g. walking quickly or climbing steps. The aim of 10 000 steps a day can serve as a guide for the level of daily activities 194 , 195 , which should be supplemented by sporting activities. Types of sports that draw upon large muscle groups are particularly suitable, including for beginners, and include walking, Nordic walking, bicycling at moderate speed, swimming/aqua fitness, cross-country skiing and low impact aerobic or pregnancy yoga. Women should not begin new types of sports with unaccustomed sequences of movement in pregnancy. Types of sports that are considered inappropriate are those with a high risk of falls and injury, e.g. team, contact or fighting sports or scuba-diving 53 . Healthy pregnant women can be physically active at elevations of up to 2000 to 2500 m, particularly if they are accustomed to these elevations 196 , 197 . Women who engage in sport can continue their previous sporting activity in a complication-free pregnancy and train somewhat more intensively than beginners 171 , 193 , 198 , 199 .

Possible warning signs are vaginal bleeding, labour, loss of amniotic fluid, dyspnoea, dizziness, headache, chest pain, muscular imbalance, calf pain and swelling 53 . Physical activity is contraindicated in haemodynamically relevant heart diseases, restrictive lung disease, cervical insufficiency, premature labour, persistent bleeding in the second and third trimester, placenta praevia after 26 weeks of pregnancy, ruptured amniotic sac, pre-eclampsia, pregnancy-induced hypertension or severe anaemia 53 .

In reality, the level of exercise frequently declines during pregnancy 53 , 60 . Reported barriers are lack of time, lack of motivation and above all fears and safety aspects 200 . Professionals should encourage pregnant women to arrange their everyday life and leisure time so as to be active and to limit or regularly interrupt sedentary activities. They should take the concerns and anxieties of pregnant women/expectant parents seriously and inform them that exercise is desirable in a normal healthy pregnancy and safe for mother and child.

Alcohol

Recommendation.

Women who are planning a pregnancy and pregnant women must avoid alcohol.

Bases of the recommendation

On the basis of the available evidence it is not possible to define a safe and risk-free amount of alcohol for the fetus or a time window in pregnancy when alcohol consumption does not present a risk 204 . National and international learned societies 4 , 52 , 205 and the Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA) therefore advise against drinking alcohol during pregnancy. It is also recommended to refrain from alcohol during the period of planning a pregnancy 3 , 4 , 206 , 207 .

Background information

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy can lead to birth defects, growth restriction, damage to tissue and nerve cells as well as to an irreversible reduction in the childʼs intelligence and can exert an effect on its behaviour (hyperactivity, impulsivity, distraction, risky behaviour, infantilism and disorders of social maturity) 201 , 202 , 203 . Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is the most common avoidable disability in neonates with an estimated incidence of 0.2 – 8 in 1000 neonates 12 . Substantially more children are affected by a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder 12 , 203 . The extent of the individual health risk to the child is difficult to predict and is affected by maternal and fetal characteristics. Although large systematic studies have demonstrated no negative long-term effect of mild to moderate alcohol consumption 208 , it is safest to avoid all alcohol consumption 209 . The recommendation “to avoid alcohol in pregnancy” could promote uncertainty or feelings of guilt in women who consumed alcohol early in pregnancy before they were aware of the pregnancy. For this reason, specialists should provide differentiated and sensitive advice.

Smoking

Recommendations.

Women/couples who are planning a pregnancy should not smoke.

Pregnant women must avoid smoking and stay in rooms where people are smoking or have smoked.

Bases of the recommendations

The recommendation to change smoking habits even during the phase of wishing to have a child and of not smoking in pregnancy meet the recommendations of the Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et dʼObstétrique (FIGO) 4 , other national specialist organisations 62 , 128 and the Federal Centre for Health Education 218 .

Background information

Smoking has a negative effect on fertility 64 and can increase the risk for premature births and miscarriages, birth defects, premature placental detachment and low birth weight, but also the later risk for obesity and allergies in the child 210 , 211 , 212 , 213 , 214 , 215 , 216 , 217 . In Germany, 26% of 18- to 25-year-old women and 34% of men of the same age smoke 11 ; in older age groups, the proportion is somewhat higher (30% of women, 35% of men) 219 . Of the mothers of 0- to 6-year-old children questioned in the KiGGS study, 11% had smoked in pregnancy. Pregnant women under 25 years of age at the time of their childʼs birth or belonging to a low socioeconomic group had smoked twice as often during pregnancy as older women or women with a high socioeconomic status 220 .

All professional groups who counsel women/couples wishing to have a child, pregnant women and expectant parents should discuss smoking and where necessary explicitly and repeatedly address the persons they are counselling about their cigarette consumption or their habits. They should motivate them to adopt weaning measures and point out that the wish to have children and pregnancy are good opportunities to stop smoking. To encourage smoking cessation, materials are also specifically available for pregnant women and for disseminators as well as advice lines ( www.rauchfrei-info.de ).

Nicotine is frequently contained in e-cigarettes. Even for e-cigarettes without nicotine, health concerns are raised 221 . Pregnant women are therefore recommended to avoid e-cigarettes.

Caffeinated Beverages During Pregnancy

Recommendation.

Pregnant women should drink caffeinated beverages only in moderate amounts.

Bases of the recommendation

The data are inadequate for assessing possible detrimental effects of caffeine on the mother and child and for quantifying amounts of caffeine that do not present a risk. A dose-dependent association between caffeine consumption in pregnancy and the risk of fetal growth retardation and negative effects on birth weight has been observed in studies 222 , 223 . The EFSA gives a safe caffeine dose for the period of pregnancy of 200 mg/day 224 .

Background information

Caffeine crosses the placenta rapidly but cannot be metabolised either by the fetus or in the placenta 224 . The relationship between maternal caffeine intake and pregnancy duration, birth weight, fetal growth retardation and small for gestational age (SGA) has been investigated in studies. According to a current meta-analysis of case-control and observational studies, there is a significantly increased risk of spontaneous abortion from 300 mg caffeine daily and above 225 . Another meta-analysis shows a linear association between caffeine consumption and miscarriage rate, although other possible confounding factors were not considered 226 . A Cochrane meta-analysis was unable to draw any conclusions about the effectiveness of abstention from caffeine on birth weight or other relevant endpoints because of limited data 227 .

Data on the mean caffeine content of beverages are shown in Table 1 . Energy drinks must not contain more than 320 mg caffeine/litre 228 and those containing 150 mg caffeine per litre and over must be labelled “Increased caffeine content. Not recommended for children and pregnant or breast-feeding women” 229 . Further typical ingredients of energy drinks are glucuronolactone, taurine and inositol, the interactions between which have not been fully established, as well as large amounts of sugar. Pregnant women should therefore avoid energy drinks.

| 200 ml filter coffee: | about 90 mg |

| 60 ml espresso: | about 80 mg |

| 200 ml black tea (1 cup): | about 45 mg |

| 200 ml green tea (1 cup): | about 30 mg |

| 250 ml cola drinks: | 25 mg/330 ml (can about 35 mg) |

| 250 ml energy drink (1 tin): | about 80 mg |

| 200 ml cocoa drink: | 8 to 35 mg |

Medication Use in Pregnancy

Recommendation.

In pregnancy medications must only be taken or stopped after consulting a physician.

Basis of the recommendations

Medications, whether prescription-only or over-the-counter, may affect the child. The overwhelming majority of medications have been insufficiently studied in terms of risks in pregnancy. In the consumption and prescription of medications, the individual risk to the mother from not receiving treatment must be weighed against the risks to the unborn child.

Background information

Substance-specific recommendations can be given in the course of a medical consultation. Where necessary, a dose adjustment or a switch of medication may be necessary even before conception. Necessary treatment must not be stopped because of wrong assumptions about harm to the unborn child.

Within the Pharmacovigilance Network of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM), the course of pregnancies for which the network has provided advice on medication use is documented and these data are evaluated jointly with similar centres in other European countries (ENTIS European Network of Territorial Information Services [ https://www.entis-org.eu ]). Information about the safety of medications in pregnancy and during breast-feeding is available via the website www.embryotox.de .

Women with chronic diseases who are planning a pregnancy require special medical counselling.

Preparation for Breast-Feeding

Recommendation.

Expectant parents must be informed and given advice about breast-feeding because breast-feeding is best for mother and child.

Bases of the recommendation

A Cochrane review article comes to the conclusion that all forms of additional support have a positive effect on the increased duration of breast-feeding and the duration of exclusive breast-feeding 231 . The recommendation is consistent with recommendations on the promotion of breast-feeding in Germany 239 and in other countries 249 .

Background information

Measures to support breast-feeding exert a positive effect on the initiation and duration of breast-feeding 231 . Since the motherʼs intention to breastfeed, an early latch and early initiation of breast-feeding are very important for successful breast-feeding and insecurities often lead to premature weaning 232 , 233 , 234 , 235 , 236 , women and their partners should obtain breast-feeding counselling even during pregnancy. A positive attitude on the part of the partner also has a positive effect on the initiation and duration of breast-feeding 237 , 238 . Professionals and trained lay people, personal (as opposed to telephone) support, four to eight contacts and settings with high initial breast-feeding rates can promote exclusive breast-feeding 241 .

Although different forms of support in pregnancy and during the post partum period show positive effects on the attitude to breast-feeding, it is not possible to provide more specific details, e.g. in terms of measures or times 231 , 240 , 241 , 242 , 243 , 244 . Counselling and support are more effective if they are offered not only for a short time, but where possible over the whole of the pregnancy until after the childʼs birth 245 and in an ambulatory as well as an inpatient setting 246 .

Nutrition in Pregnancy for the Prevention of Allergies in the Child

Recommendations.

Pregnant women must not exclude any foods from their diet to prevent allergies in the child. The avoidance of certain foods during pregnancy is not beneficial for the prevention of allergies in the child.

Pregnant women are recommended to consume oily fish regularly also with respect to allergy prevention.

Basis of the recommendations

The recommendations are based on current data and the German guidelines for allergy prevention of 2014 247 .

Background information

A low-allergen diet on the part of the mother during pregnancy does not lead to a reduced allergy risk in the child 248 , 249 . Dietary restrictions are therefore not meaningful and can also be associated with the risk of insufficient nutrient intake. However, foods to which the woman herself exhibits an allergic reaction should also be avoided in pregnancy.

There is evidence that the consumption of sea fish and the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids that they contain during pregnancy and/or while breast-feeding has a protective effect against the development of atopic diseases in the child 250 , 251 . Randomised controlled trials have shown that the risk of asthma is halved in children whose mothers had taken long-chain omega-3 fatty acids at doses greater than 2 g/day as a supplement during pregnancy 252 , 253 .

The consumption of prebiotics and probiotics during pregnancy does not offer any sufficiently proven benefits for allergy prevention in the child.

From the point of view of allergy prevention in the child as well, pregnant women should avoid smoking and areas where there is or has been smoking. In families with a medical history of allergies, the acquisition of cats should be avoided. Furthermore, pregnant women should avoid high exposure to air pollutants and mould accumulation in order to protect their health.

Oral and Dental Health

Recommendation.

Women who are planning a pregnancy should have a dental check-up and where necessary undergo specific treatment.

Bases of the recommendation

Untreated maternal periodontitis has been associated in studies with an increased risk of premature birth and low birth weight 255 , 256 , 257 , 258 ). Mothers with untreated caries pass on caries-associated bacteria to their child 259 , thus increasing the risk of caries in the child 256 , 260 . Appropriate oral hygiene and a healthy diet for teeth reduce the caries-associated microflora. Dentist-supported caries prevention of the mother in pregnancy has the potential to reduce the later degree of caries in the child 261 , 262 .

Background information

Regular appropriate oral hygiene is one of the general health care measures and is recommended for all adults 254 . Altered defence reactions in the gingiva and hormonal changes in pregnancy (increased oestrogen and progesterone levels) encourage the development of inflammation of the gums (gingivitis), characterised by increased sensitivity and a tendency to bleeding 263 . Existing periodontitis can be exacerbated 263 . Whether treatment of periodontitis reduces the risk of premature birth and low birth weight cannot be answered with certainty due to contradictory study results 257 , 258 , 264 .

Recommended dental and oral hygiene includes brushing the teeth with fluorinated toothpaste at least twice a day, carefully cleaning the gaps between the teeth with dental floss or interdental brushes once a day 254 , 265 and having the teeth cleaned professionally at the dentistʼs at individually defined intervals. The frequency depends among other factors on the individual risk for caries and periodontitis 266 . The German Society of Periodontology (DG PARO) recommends supporting oral hygiene by professional teeth cleaning with oral hygiene instruction at the beginning and end of pregnancy 263 .

Where diseases of the teeth and gums are present, the dentist should be consulted where possible even before the pregnancy. As well as preventive and diagnostic measures, preservative treatments can usually also be performed during pregnancy (such as the placement of fillings, fitting of individual crowns or treatment of periodontitis 255 , 267 . As a rule amalgam fillings should not be placed during pregnancy 268 . In specific indications, amalgam fillings can be removed and replaced by other filling material.

Vaccinations

Recommendation.

The vaccination status should be checked and vaccination gaps should be plugged in women who are planning a pregnancy.

Basis of the recommendation

Vaccine-preventable diseases during pregnancy increase the risk to the womanʼs health, can result in severe birth defects in the child and may be life-threatening for newborns. The Standing Committee on Vaccination at the Robert Koch Institute (STIKO) gives recommendations for women of childbearing age wishing to have a child, for women in pregnancy and for further contacts in the infantʼs immediate environment 269 .

Background information

Complete protection against measles, rubella, varicella (chickenpox) and pertussis (whooping cough) is of particular importance in the family planning phase. The STIKO recommends the appropriate vaccinations for women wishing to have children. While dead vaccines (inactivated vaccines: killed pathogens or their constituents) can in principle be administered even in pregnancy, live vaccines (such as those for measles, mumps, rubella and varicella) are contraindicated for pregnant women. After each vaccination with a live vaccine, reliable contraception must be recommended one month. However, even if this period is not observed and even in the event of inadvertent vaccination in early pregnancy, no fetal damage as a result of these vaccinations is known to date 270 .

Vaccinations not only protect the pregnant woman, who is more susceptible to infection due to hormonal changes than outside of pregnancy, but also the unborn or newborn child. Practically all viral infections in pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of abortions, birth defects, premature births and complications of pregnancy. In addition, pregnant women are themselves at increased risk, e.g. in the case of measles, of developing severe pneumonia.

There is a particularly high risk of severe disease courses in influenza infections in pregnancy. The STIKO has recommended vaccination against seasonal influenza for all pregnant women since 2010 271 , which also protects the neonate in the first few weeks of life against serious courses of diseases as a result of the maternal vaccine-induced antibodies, also known as “nest protection” 272 .

Conclusion

A balanced diet, regular exercise and a healthy lifestyle are particularly important before and during pregnancy. The time before conception and the first 1000 days of the childʼs life provide an opportunity to lay the foundations for the health of the child, the expectant mother and the family. This potential for prevention should be recognised and utilised on a broad basis. The revised recommendations presented here provide uniform, practical and up-to-date knowledge-based recommendations for pregnancy and also for women/couples wishing to have a child.

Acknowledgements

The Healthy Start – Young Family Network and the authors thank Uta Engels (University of Regensburg), Nina Ferrari (University Hospital Cologne), Thomas Kauth (Ludwigsburg), Lucilla Poston (Kings College London), Marion Sulprizio (German Sport University Cologne) and Janina Goletzke (Hamburg-Eppendorf University Hospital) for their technical support and their valuable contributions to the discussion.

Danksagung

Das Netzwerk Gesund ins Leben und die Autoren danken Uta Engels (Universität Regensburg), Nina Ferrari (Universitätsklinikum Köln), Thomas Kauth (Ludwigsburg), Lucilla Poston (Kings College London), Marion Sulprizio (Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln) und Janina Goletzke (Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf) für die fachliche Unterstützung und wertvolle Diskussionsbeiträge.

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt B. Koletzko, M. Cremer, M. Flothkötter, C. Graf, H. Hauner, C. Hellmers, M. Kersting, M. Krawinkel, M. Röbl-Mathieu, H. Przyrembel, U. Schiffner, K. Vetter, A. Weißenborn and A. Wöckel declare that there are no conflicts of interest under the terms of the guidelines of the Institute of Medicine. The work of BK was supported by grants from the Commission of the European Communities (FP5-QLRT-2001-00389 CHOPIN, FP5-QLAM-2001-00582 PIANO, FP6-007036QLRT-2001-00389 EARNEST, FP7-289346- EarlyNutrition), the European Research Council (Advanced Grant ERC-2012-AdG – no. 322605 META-GROWTH), the European Erasmus+ programme (Early Nutrition eAcademy Southeast Asia – 573651-EPP-1-2016-1-DE-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP and Capacity Building to Improve Early Nutrition and Health in South Africa – 598488-EPP-1-2018-1-DE-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP) and the European Interreg programme (Focus in CD – CE111). Additional funding came from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (No. 01 GI 0825), the German Research Foundation (KO912/10-1), the McHealth innovation initiative of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU) and the Centre for Advanced Studies of the LMU. The LMU and its employee BK have worked with pharmaceutical food companies on scientific and educational projects, the majority of which were state-supported research projects. None of these interactions had any influence on the contents of this manuscript./ B. Koletzko, M. Cremer, M. Flothkötter, C. Graf, H. Hauner, C. Hellmers, M. Kersting, M. Krawinkel, M. Röbl-Mathieu, H. Przyrembel, U. Schiffner, K. Vetter, A. Weißenborn und A. Wöckel erklären, dass kein Interessenkonflikt im Sinne der Richtlinien des Institute of Medicine besteht. Die Arbeit von BK wird durch finanzielle Förderung der Kommission der Europäischen Gemeinschaften (FP5-QLRT-2001-00389 CHOPIN, FP5-QLAM-2001-00582 PIANO, FP6-007036QLRT-2001-00389 EARNEST, FP7-289346- EarlyNutrition), das European Research Council (Advanced Grant ERC-2012-AdG – no. 322605 META-GROWTH), das europäische Erasmus+ Programm (Early Nutrition eAcademy Southeast Asia – 573651-EPP-1-2016-1-DE-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP und Capacity Building to Improve Early Nutrition and Health in South Africa – 598488-EPP-1-2018-1-DE-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP) und das europäische Interreg-Programm (Focus in CD – CE111) unterstützt. Zusätzliche Förderung erfolgte durch das Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Nr. 01 GI 0825), die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KO912/10-1), die Innovationsinitiative McHealth der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU) und das Center for Advanced Studies der LMU. Die LMU und ihr Mitarbeiter BK haben bei wissenschaftlichen und edukativen Projekten mit pharmazeutischen Nahrungsmittel-Unternehmen zusammengearbeitet, überwiegend als Teil öffentlich geförderter Forschungsprojekte. Keine dieser Interaktionen hat Einfluss auf den Inhalt dieses Manuskriptes genommen.

The term “parents” encompasses all forms of relationships in which there is a wish to have children or in which a woman is pregnant.

The following key words (Mesh terms and title/abstract) in various spellings and truncations were searched for in the databases: diet/nutrition, energy/nutrient requirement, reference value, exercise/physical activity/sports, body weight/gestational weight gain/body weight changes, alcohol/alcohol consumption AND childbearing/gestation/gravidity/pregnancy, reproductive planning/pregnancy planning/pre gestation. The search was confined to meta-analyses, systematic reviews and guidelines/consensus development conferences since 2012.

Der Begriff „Eltern“ umfasst alle Formen von Lebensgemeinschaften mit Kinderwunsch oder Lebensgemeinschaften, in denen eine Frau schwanger ist. Wird der Begriff „Partner“ verwendet, sind ausdrücklich auch Partnerinnen mit gemeint.

In den Datenbanken wurde mit folgenden Schlagworten (Mesh-Terms und Title/Abstract) in unterschiedlichen Schreibweisen und Trunkierungen recherchiert: diet/nutrition, energy/nutrient requirement, reference value, exercise/physical activity/sports, body weight/gestational weight gain/body weight changes, alcohol/alcohol consumption AND childbearing/gestation/gravidity/pregnangy, reproductive planning/pregnancy planning/pre gestation. Die Recherche wurde auf Metaanalysen, systematische Reviews und Guidelines/Consensus Development Conference ab 2012 eingeschränkt.

Supporting Information

Supplement Table 1 – Cohort studies related to IOM recommendations.

Ergänzendes Material

Supplement Tabelle 1 – Kohortenstudien, die im Kontext zu IOM Empfehlungen stehen.

References/Literatur

- 1.Koletzko B, Schiess S, Brands B. [Infant feeding practice and later obesity risk. Indications for early metabolic programming] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2010;53:666–673. doi: 10.1007/s00103-010-1079-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit Nationales Gesundheitsziel – Gesundheit rund um die GeburtOnline:https://www.bundesregierung.de/Content/Infomaterial/BMG/_3005.html?view=trackDownloadlast access: 31.07.2018

- 3.Röbl-Mathieu M. Preconception Counselling. Frauenarzt. 2013;54:966–972. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanson M A, Bardsley A, De-Regil L M. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) recommendations on adolescent, preconception, and maternal nutrition: “Think Nutrition First”. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131 04:S213–S253. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(15)30034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mensink G BM, Schienkiewitz A, Haftenberger M. Übergewicht und Adipositas in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1) Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2013;56:786–794. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stubert J, Reister F, Hartmann S. Risiken bei Adipositas in der Schwangerschaft. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:276–282. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies S C. London: Department of Health; 2015. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer, 2014, The Health of the 51 %: Women. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melchior H, Kurch-Bek D, Mund J. The prevalence of gestational diabetes. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114:412–418. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoenaker D A, Mishra G D, Callaway L K. The Role of Energy, Nutrients, Foods, and Dietary Patterns in the Development of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:16–23. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett C J, Walker R E, Blumfield M L. Interventions designed to reduce excessive gestational weight gain can reduce the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;141:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orth B, Töppich J.Rauchen bei Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen in Deutschland 2014. Ergebnisse einer aktuellen Repräsentativbefragung und TrendsOnline:https://www.bzga.de/forschung/studien-untersuchungen/studien/suchtpraevention/?sub=90last access: 29.12.2017

- 12.Die Drogenbeauftragte der Bundesregierung Bundesministerium für Gesundheit Drogen- und Suchtbericht Juni 2016Online:https://www.drogenbeauftragte.de/fileadmin/dateien-dba/Drogenbeauftragte/4_Presse/1_Pressemitteilungen/2016/2016_2/160928_Drogenbericht-2016_NEU_Sept.2016.pdflast access: 31.07.2018

- 13.Koletzko B, Bauer C P, Bung P. [Nutrition in pregnancy – Practice recommendations of the Network „Healthy Start – Young Family Network“] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2012;137:1366–1372. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1305076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephenson J, Heslehurst N, Hall J. Before the beginning: nutrition and lifestyle in the preconception period and its importance for future health. Lancet. 2018;391:1830–1841. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung . Köln: Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung; 2016. frauen leben 3. Familienplanung im Leben von Frauen. Schwerpunkt: Ungewollte Schwangerschaften. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang C, Wu Y, Li S. Maternal prepregnancy obesity and the risk of shoulder dystocia: a meta-analysis. BJOG. 2017 doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balsells M, Garcia-Patterson A, Corcoy R. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the association of prepregnancy underweight and miscarriage. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;207:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meehan S, Beck C R, Mair-Jenkins J. Maternal obesity and infant mortality: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;133:863–871. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe . Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2016. Good maternal Nutrition. The best Start in Life. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaudet L, Ferraro Z M, Wen S W. Maternal obesity and occurrence of fetal macrosomia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:640291. doi: 10.1155/2014/640291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nutrition Working Group . OʼConnor D L, Blake J, Bell R. Canadian Consensus on Female Nutrition: Adolescence, Reproduction, Menopause, and Beyond. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:508–5.54E20. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Weight management before, during and after pregnancyOnline:https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph27/resources/weight-management-before-during-and-after-pregnancy-pdf-1996242046405last access: 16.11.2017

- 23.Dudenhausen J W, Grunebaum A, Kirschner W. Prepregnancy body weight and gestational weight gain-recommendations and reality in the USA and in Germany. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:591–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beyerlein A, Lack N, von Kries R. Within-population average ranges compared with Institute of Medicine recommendations for gestational weight gain. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1111–1118. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f1ad8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization ; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, University UN . Rome: WHO; 2004. Human energy requirements. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation, Rome, Italy, 17 – 24 October 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldberg G R. Nutrition in pregnancy: the facts and fallacies. Nurs Stand. 2003;17:39–42. doi: 10.7748/ns.17.19.39.s57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen K M, Yaktin A L. Committee to reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines . Washington (DC): Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US); 2009. Weight Gain during Pregnancy: reexamining the Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein R F, Abell S K, Ranasinha S. Association of Gestational Weight Gain With Maternal and Infant Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;317:2207–2225. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margerison Zilko C E, Rehkopf D, Abrams B. Association of maternal gestational weight gain with short- and long-term maternal and child health outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:5740–5.74E10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott C, Andersen C T, Valdez N. No global consensus: a cross-sectional survey of maternal weight policies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alavi N, Haley S, Chow K. Comparison of national gestational weight gain guidelines and energy intake recommendations. Obes Rev. 2013;14:68–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blake-Lamb T L, Locks L M, Perkins M E. Interventions for Childhood Obesity in the First 1,000 Days A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:780–789. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicklas J M, Barbour L A. Optimizing Weight for Maternal and Infant Health – Tenable, or Too Late? Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2015;10:227–242. doi: 10.1586/17446651.2014.991102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boney C M, Verma A, Tucker R. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e290–e296. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds R M, Allan K M, Raja E A. Maternal obesity during pregnancy and premature mortality from cardiovascular event in adult offspring: follow-up of 1 323 275 person years. BMJ. 2013;347:f4539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vinturache A, McKeating A, Daly N. Maternal body mass index and the prevalence of spontaneous and elective preterm deliveries in an Irish obstetric population: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015258. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoellen F, Hornemann A, Haertel C. Does maternal underweight prior to conception influence pregnancy risks and outcome? In Vivo. 2014;28:1165–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin D, Song W O. Prepregnancy body mass index is an independent risk factor for gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, preterm labor, and small- and large-for-gestational-age infants. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1679–1686. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.964675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Busetto L, Dicker D, Azran C. Practical Recommendations of the Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of Obesity for the Post-Bariatric Surgery Medical Management. Obes Facts. 2017;10:597–632. doi: 10.1159/000481825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deutsche Adipositas-Gesellschaft (DAG) e.V. Deutsche Diabetes Gesellschaft (DDG) Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung (DGE) e.V. Interdisziplinäre Leitlinie der Qualität S3 zur „Prävention und Therapie der Adipositas“Online:http://www.adipositas-gesellschaft.de/fileadmin/PDF/Leitlinien/S3_Adipositas_Praevention_Therapie_2014.pdflast access: 28.05.2018

- 41.Kwong W, Tomlinson G, Feig D S. Maternal and neonatal outcomes after bariatric surgery; a systematic review and meta-analysis: do the benefits outweigh the risks? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaddoe V WV. Persönliche Mitteilung. 2018.

- 43.Beyerlein A, Schiessl B, Lack N. Optimal gestational weight gain ranges for the avoidance of adverse birth weight outcomes: a novel approach. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1552–1558. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogozinska E, Marlin N, Jackson L. Effects of antenatal diet and physical activity on maternal and fetal outcomes: individual patient data meta-analysis and health economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21:1–158. doi: 10.3310/hta21410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dodd J M, Turnbull D, McPhee A J. Antenatal lifestyle advice for women who are overweight or obese: LIMIT randomised trial. BMJ. 2014;348:g1285. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]