Abstract

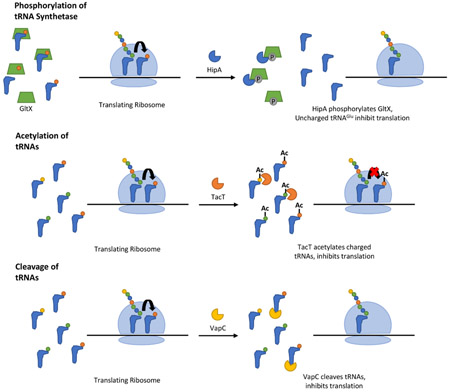

Prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin systems are composed of a protein toxin and its cognate antitoxin. These systems are abundant in bacteria and archaea and play an important role in growth regulation. During favourable growth conditions, the antitoxin neutralizes the toxin’s activity. However, during conditions of stress or starvation, the antitoxin is inactivated, freeing the toxin to inhibit growth and resulting in dormancy. One mechanism of growth inhibition used by several toxin-antitoxin systems results from targeting tRNAs, either through preventing aminoacylation, acetylating the primary amino group, or endonucleolytic cleavage. All of these mechanisms inhibit translation and result in growth arrest. Many of these toxins only act on a specific tRNA or a specific subset of tRNAs, however more work is necessary to understand the specificity determinants of these toxins. For the toxins whose specificity has been characterized, both sequence and structural components of the tRNA appear important for recognition by the toxin. Questions also remain regarding the mechanisms used by dormant bacteria to resume growth after toxin induction. Rescue of stalled ribosomes by tmRNAs, removal of acetylated amino groups from tRNAs, or ligation of cleaved RNA fragments have all been implicated as mechanisms for reversing toxin-induced dormancy. However, the mechanisms of resuming growth after induction of the majority of tRNA targeting toxins are not yet understood.

Graphical/Visual Abstract and Caption

Bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems use various mechanisms to inhibit translation and arrest growth by targeting tRNAs.

Introduction

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are widespread throughout bacteria and archaea. TA systems are composed of a protein toxin and its cognate antitoxin, which may be an RNA or a protein depending on the type. During favourable growth conditions, the antitoxin inhibits the toxin’s activity. However, during conditions of stress, the antitoxin is inactivated and the toxin is free to inhibit growth. This results in dormancy or cell death and has a number of different functions in the cell, such as plasmid maintenance, phage resistance, stress survival, and formation of persister cells. The mechanisms used by different families of TA systems to cause growth arrest are the subject of active research. The focus of this review is the TA systems that target tRNAs as their mechanism of growth inhibition.

Toxins that target tRNAs use a variety of activities to inhibit translation. The VapC toxins and MazF-mt9 toxin are endonucleases that cleave tRNAs. The TacT and AtaT toxins function as acetyltransferases that acetylate the amino group of tRNAs. Finally, the HipA toxin phosphorylates and inactivates glutamyl-tRNA synthetase, which prevents aminoacylation of tRNAGlu. Some of these toxins target a single tRNA isotype with high specificity, while others have a broader activity on multiple tRNAs. Studies of some VapC toxins and the MazF-mt9 toxin have identified the sequence and structural features necessary for efficient cleavage of their RNA targets (Schifano et al., 2016; Walling & Butler, 2018; K. S. Winther, Brodersen, Brown, & Gerdes, 2013). While the mechanisms of growth arrest by these toxins have been characterized, it is unclear how bacteria resume growth after toxin-induced dormancy for the majority of TA systems. A few characterized examples include tmRNAs rescuing stalled ribosomes, a peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase removing modified amino groups from aminoacyl-tRNAs, and an RNA ligase repairing cleaved 16S rRNA (Cheverton et al., 2016; Christensen & Gerdes, 2003; Christensen, Pedersen, Hansen, & Gerdes, 2003; Temmel et al., 2017). However, the mechanisms that repair toxin-induced RNA damage thereby allowing resumption of cell growth remain largely uncharacterized.

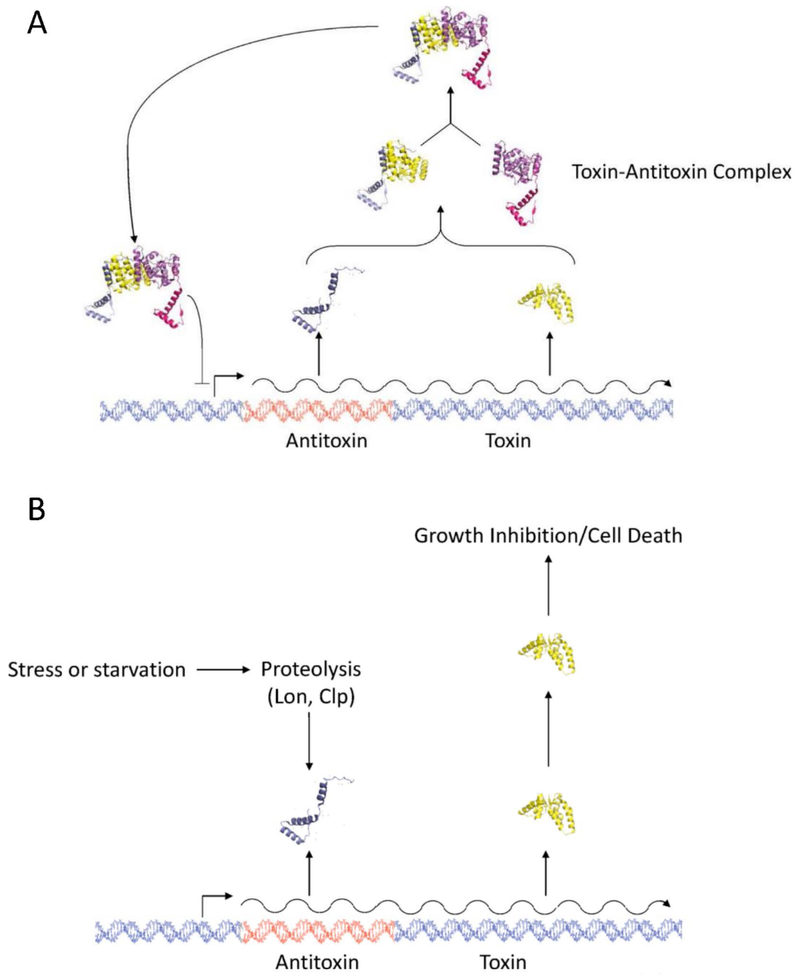

GENERAL MECHANISM AND REGULATION OF TOXIN-ANTITOXIN SYSTEMS

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems consist of a protein toxin and its cognate antitoxin, which are typically co-transcribed from a single operon (Figure 1). In most cases, the antitoxin is found upstream of the toxin and their expression is translationally coupled, allowing for equimolar production of the toxin and antitoxin. However, in a recent study of the 12 type II TA systems in E. coli, ribosome profiling suggests that the antitoxin is produced at greater levels compared to the toxin (G. W. Li, Burkhardt, Gross, & Weissman, 2014). When the antitoxin inhibits the toxin, the organism can grow normally. However, during conditions of stress or nutrient deprivation, the antitoxin is inactivated, allowing the toxin to inhibit growth, thereby promoting a non-replicating, dormant state. In type II systems (shown in Figure 1), degradation by Lon or Clp proteases causes antitoxin inactivation (Muthuramalingam, White, & Bourne, 2016). The antitoxin functions to neutralize the toxic effects of its cognate toxin through different mechanisms depending on antitoxin type, described in further detail below.

Figure 1 –

General mechanism of type II toxin-antitoxin systems. (A) Depiction of type II toxin-antitoxin operon, where the toxin and antitoxin are co-transcribed into a single mRNA. During normal growth, the antitoxin binds the toxin and neutralizes its activity. The toxin-antitoxin complex represses transcription of the operon. (B) During stress conditions, bacterial proteases degrade the antitoxin, leaving the toxin free to inhibit bacterial growth. Crystal structures of FitAB from Neisseria gonorrhoeae obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank, PDB ID: 2H1C (Mattison, Wilbur, So, & Brennan, 2006; Rose et al., 2016; Rose & Hildebrand, 2015).

In type II systems, transcription of the TA operon is negatively regulated by binding of the toxin-antitoxin complex to the promoter region. This binding is mediated by the antitoxin, which contains a conserved DNA binding domain; however, present evidence suggests that binding is stronger when the antitoxin is in complex with the toxin (G. Y. Li, Zhang, Inouye, & Ikura, 2008; Zorzini et al., 2015). Many TA operons are regulated by a phenomenon called conditional cooperativity, where the ratio of antitoxin to toxin mediates the level of gene expression (Page & Peti, 2016). When the antitoxin is present in excess of the toxin, the TA complex represses transcription of the operon. However, the repressor complex is destabilized when the amount of toxin exceeds that of the antitoxin (Overgaard, Borch, Jorgensen, & Gerdes, 2008; K. S. Winther & Gerdes, 2012). Structural studies of the RelBE toxin-antitoxin complex, where RelB is the antitoxin and RelE the toxin, demonstrate that a dimer of RelB antitoxin dimers binds the operator to repress transcription of the operon. This RelB tetramer is stabilized on the operator region when bound with RelE toxins (G. Y. Li et al., 2008). However, excess RelE destabilizes TA complex binding, resulting in increased expression of the operon (Boggild et al., 2012; Overgaard et al., 2008). Crystal structures and molecular modelling of the VapBC complex suggest a similar phenomenon, demonstrating how binding of excess VapC toxin disrupts toxin dimers, destabilizing complex binding to the promoter, and relieving repression of transcription (Dienemann, Boggild, Winther, Gerdes, & Brodersen, 2011; Mate et al., 2012; K. S. Winther & Gerdes, 2012). This regulatory mechanism provides tight control over transcription of the operon, which prevents accumulation of excess toxin and thereby prevents random activation of the toxin. Additionally, upon the return of favourable growth conditions when Lon protease no longer degrades the antitoxin, antitoxin will accumulate until the ratio again exceeds that of the toxin. This allows for a rapid inhibition of TA transcription (Cataudella, Sneppen, Gerdes, & Mitarai, 2013; Cataudella, Trusina, Sneppen, Gerdes, & Mitarai, 2012).

TYPES OF TOXIN-ANTITOXIN SYSTEMS

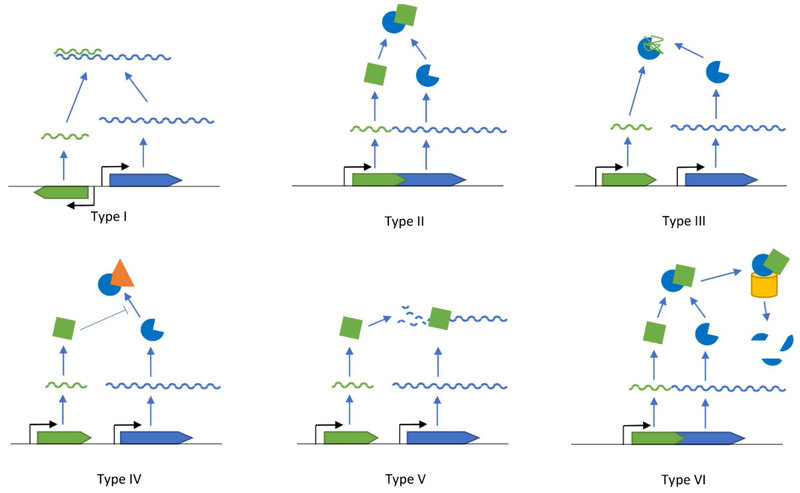

There are six types of TA systems, which are classified based on the antitoxin’s mechanism of action (Figure 2) (A. Harms, Brodersen, Mitarai, & Gerdes, 2018). The type I systems feature an RNA antitoxin, which binds to the toxin mRNA and prevents its translation. Examples of these systems include hok/sok, fst/RNAII, and tisB/IstR1 (Darfeuille, Unoson, Vogel, & Wagner, 2007; Gerdes, Bech, et al., 1986; Weaver & Tritle, 1994).

Figure 2 –

Types of toxin-antitoxin systems. Each of the six types of toxin-antitoxin systems are described in the text. Type I systems – the antitoxin (green) is an RNA that binds the toxin mRNA (blue), preventing its translation. Type II systems – the antitoxin is a protein that directly binds its cognate toxin to inhibit its activity. Type III systems – the antitoxin is an RNA that inactivates the toxin protein. Type IV systems – the antitoxin is a protein that protects the cellular target (orange) of the toxin. Type V systems – the antitoxin is a protein that degrades the toxin mRNA. Type VI systems – the antitoxin is a protein that acts as an adaptor between the toxin protein and ClpXP (yellow), which degrades the toxin.

Type II systems are the most abundant and best studied family of TA systems (Pandey & Gerdes, 2005). These systems utilize a protein antitoxin that directly binds to its cognate toxin, neutralizing its toxic activity. The most studied of these systems is the MazEF system, and the RelBE and HipBA systems have also been extensively researched (E. Germain, Castro-Roa, Zenkin, & Gerdes, 2013; Pedersen et al., 2003; Schifano et al., 2014; Vesper et al., 2011; Y. Zhang et al., 2003). The most abundant type II system is the VapBC system, which is described in further detail below (Pandey & Gerdes, 2005).

The type III systems utilize an RNA antitoxin that binds to the protein toxin to inactivate it (Goeders, Chai, Chen, Day, & Salmond, 2016). These systems include the ToxIN and CptIN systems, which contribute to phage resistance (Blower, Short, et al., 2012; P. C. Fineran et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2015; Short, Akusobi, Broadhurst, & Salmond, 2018; Short et al., 2013).

The type IV systems feature a protein antitoxin. These antitoxins protect the cellular targets of their cognate toxins (Brown & Shaw, 2003). YeeU/YeeV is an example of a type IV system, where the YeeV toxin prevents polymerization of the cytoskeletal proteins MreB and FtsZ. YeeU, the cognate antitoxin of YeeV, directly binds these proteins and enhances their bundling, preventing YeeV from acting on them (Masuda, Tan, Awano, Wu, & Inouye, 2012; Wen, Wang, Sun, Guo, & Wang, 2017).

The type V systems encode a protein antitoxin, which degrades the mRNA of its cognate toxin, preventing its translation. For example, the GhoT toxin damages the bacterial membrane leading to lysis. However, the GhoS antitoxin specifically degrades GhoT mRNA, preventing expression of its toxic activity (Wang et al., 2012).

Finally, the type VI systems utilize a protein antitoxin, which promotes degradation of the toxin by ClpXP. The SocAB system consists of a SocB toxin that inhibits replication by binding the β sliding clamp (Aakre, Phung, Huang, & Laub, 2013). However, the SocA antitoxin controls SocB activity by acting as an adaptor between ClpXP and SocB, resulting in ClpXP-mediated degradation of SocB (Aakre et al., 2013).

ROLES OF TOXIN-ANTITOXIN SYSTEMS IN BACTERIA

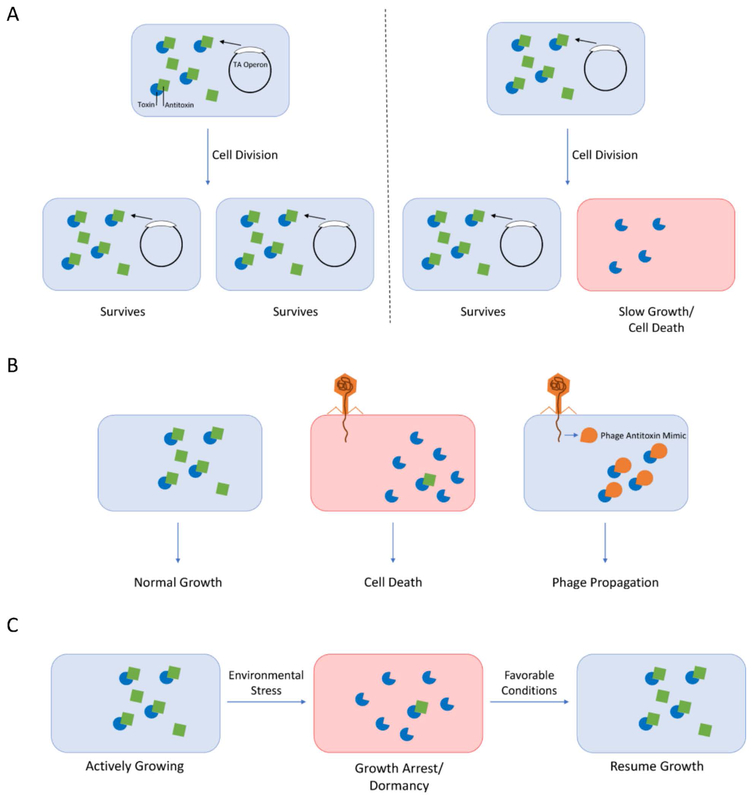

Post-segregational killing

TA systems can regulate plasmid stability in a bacterial population, also called post-segregational killing (PSK) (Figure 3A). In this role, the TA system is located on a plasmid in the cell. If the bacterial cell divides and the plasmid is maintained within each daughter cell, the plasmid will continue to produce both the toxin and the antitoxin, promoting cell survival. However, if one of the daughter cells does not inherit the plasmid during cell division, the labile antitoxin will be degraded more rapidly than the intrinsically more stable toxin (Gerdes, Thisted, & Martinussen, 1990). This leaves free toxin in the bacterium, which will kill or slow the growth of the cell, thereby favouring the growth of bacteria that contain the plasmid (Gerdes et al., 1990). It can be advantageous for bacteria to maintain these plasmids, as plasmids often contain virulence genes or antibiotic resistance cassettes. For example, the E. coli R1 plasmid contains genes conferring resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, and kanamycin (Blohm & Goebel, 1978). The R1 plasmid is maintained by a hok/sok type I TA system, in which the hok (host killing) toxin disrupts cell membrane potential leading to cell death, unless counteracted by the sok (suppressor of killing) antitoxin (Gerdes, Bech, et al., 1986; Gerdes, Rasmussen, & Molin, 1986).

Figure 3 –

Roles of TA systems in bacteria. (A) Post-segregational killing. During cell division, daughter cells that lose a plasmid encoding a TA system will enter a slow growing state or die due to activity of the toxin and loss of antitoxin. (B) Phage abortive infection. Phage infection triggers activation of the TA system, resulting in cell death and preventing phage propagation. However, some phage can mimic the antitoxin, preventing cell death and allowing for phage propagation. (C) Stress survival/antibiotic persistence. During conditions of stress, toxin activity arrests growth leading to a dormant state that can survive the stressful environment. Upon return to favorable conditions, the bacteria resume growth.

Some evidence suggests that TA systems on plasmids can play a role in competitive exclusion of other plasmids, during both horizontal and vertical transmission. In bacteria containing both a PSK+ plasmid containing a ParDE TA system and a PSK- plasmid, the efficiency of conjugative transfer of the PSK- plasmid was decreased compared to the rate of transmission when the PSK+ plasmid was absent (T. F. Cooper & Heinemann, 2000). In contrast, the transmission of the PSK+ plasmid was equally efficient in the presence or absence of the PSK- plasmid (T. F. Cooper & Heinemann, 2000). A similar phenomenon was seen in plasmids using a restriction-modification based system, rather than a TA based system. In these systems, plasmids lacking the restriction modification system will be destroyed by the restriction enzymes of the other plasmid (T. Naito, Kusano, & Kobayashi, 1995; Y. Naito, Naito, & Kobayashi, 1998).

Phage abortive infection

TA systems may also play a role in resistance to bacteriophage infection (Figure 3B) (Dy, Richter, Salmond, & Fineran, 2014). They function as abortive infection (Abi) systems, where the suicide of individually infected bacteria protects the population from phage infection. Several families of TA systems with Abi activity have been identified, including hok/sok (Type I), MazEF (Type II), AbiQ and ToxIN (Type III), and AbiE (Type IV) (Dy, Przybilski, Semeijn, Salmond, & Fineran, 2014; Peter C. Fineran et al., 2009; Hazan & Engelberg-Kulka, 2004; Pecota & Wood, 1996; Samson, Belanger, & Moineau, 2013). The ToxIN system is a type III TA system that acts as an Abi system in multiple bacterial genera to protect against a variety of different phages (Blower et al., 2009; P. C. Fineran et al., 2009). In uninfected bacteria, the ToxI antitoxin binds the ToxN toxin, neutralizing it. However, phage infection triggers release of ToxN, which is a ribonuclease that degrades cellular RNA, leading to bacterial cell death (Short et al., 2018).

However, bacteriophage can utilize molecular mimicry to avoid killing by Abi systems. The RNA antitoxin ToxI consists of 5.5 36 nucleotide repeats, which form pseudoknots that bind and neutralize ToxN (Blower et al., 2011). The bacteriophage ɸTE contains a short sequence similar to the ToxI repeat sequence. Mutant phages can expand the number of this repeat, allowing the phages to mimic the ToxI antitoxin (Blower, Evans, Przybilski, Fineran, & Salmond, 2012). These mutant phages are then able to replicate in the bacteria, unaffected by ToxIN (Blower, Evans, et al., 2012). Importantly, these mutants can then transfer that DNA to new hosts, allowing for spread of the phage infection (Blower, Evans, et al., 2012).

Stress survival

TA systems play an important role in stress survival (Figure 3C). Various studies suggest that TA systems enhance survival during the general responses to thermal stress, oxidative stress, and nitrogen limitation, among other stressors.

There are multiple mechanisms by which TA systems can contribute to the general stress response. One proposed mechanism features the production of a set of leaderless mRNAs that are translated by a modified ribosome, generated by MazF cleavage of mRNAs and the 3’ end of 16S rRNA containing the anti-Shine Dalgarno sequence (Schifano et al., 2014; Vesper et al., 2011). This would allow for the specific translation of a subset of leaderless mRNAs produced by MazF in the cell, which could potentially consist of stress responsive genes. However, recent evidence from Poly-seq (polysome fractionation followed by RNA-seq) compared changes in mRNA translation before and after MazF expression (Sauert et al., 2016). RNA sequencing identified alterations in mRNAs encoding gene products involved in a wide range of cellular processes, rather than those specific to stress response genes, suggesting general translational reprogramming induced by MazF (Sauert et al., 2016). Similarly, work from the Laub group demonstrated that E. coli MazF does not produce a large pool of leaderless mRNAs, but instead causes cleavage in the middle of transcripts, indicating that MazF induction rarely produces full-length, leaderless mRNAs (Culviner & Laub, 2018). Moreover, the authors did not detect cleavage of the anti-Shine Dalgarno sequence from 16S rRNA, but did see cleavage of rRNA precursors, which prevented rRNA maturation and ribosome biogenesis (Culviner & Laub, 2018). Ribosome profiling demonstrated general translational reprogramming, favouring a variety of transcripts that were not cleaved by MazF (Culviner & Laub, 2018). Upregulation of tmRNAs supports earlier studies demonstrating that ribosomes stalled on mRNAs cleaved by MazF are rescued by tmRNAs (Christensen et al., 2003; Culviner & Laub, 2018).

The MqsA antitoxin can also mediate the general stress response through repression of RpoS, an important regulator of stress (Wang et al., 2011). Under conditions of stress, Lon protease degrades MqsA, leading to induction of RpoS (Wang et al., 2011). This results in bacteria altering their physiology from a planktonic state to a biofilm state, which is more suited to stressful environments (Wang et al., 2011). The antitoxin DinJ also influences RpoS expression and thus the general stress response, but in an indirect manner (Hu, Benedik, & Wood, 2012). DinJ represses CspE, which is a cold-shock protein that enhances production of RpoS (Hu et al., 2012). By inactivating CspE, DinJ indirectly represses RpoS, until stress conditions lead to degradation of DinJ and thereby induction of RpoS (Hu et al., 2012).

TA systems can also play a role in responding to thermal stress, such as heat shock. Transcriptional analysis of the arachaea Sulfolobus solfataricus identified several VapBC systems that were upregulated during heat shock (C. R. Cooper, Daugherty, Tachdjian, Blum, & Kelly, 2009). Knocking out individual VapBC operons in this organism inhibited its ability to survive heat shock (C. R. Cooper et al., 2009). A plasmid-borne hok/sok system also conferred enhanced growth at high temperatures to E. coli (Chukwudi & Good, 2015). The toxin YoeB is activated in E. coli grown at high temperatures, though this does not result in growth arrest (Janssen, Garza-Sánchez, & Hayes, 2015). The authors suggest that this mRNase toxin may play a role in quality control during heat shock, rather than inhibiting growth (Janssen et al., 2015).

Pathogenenic bacteria are often exposed to oxidative stress, especially those that can survive within macrophages. Quantitative PCR determined that VapBC15 and HigBA were upregulated in M. tuberculosis during hypoxia, while VapBC11 and VapBC3 were transcriptionally activated during macrophage infection (Ramage, Connolly, & Cox, 2009). Similarly, the three RelBE systems from M. tuberculosis appear to play a role in responding to oxidative stress. All three were upregulated after exposure to oxidative stress or nitrogen-limiting environments (Korch, Malhotra, Contreras, & Clark-Curtiss, 2015). In Salmonella enterica subsp. Typhimurium (S. Typhimuriuim), expression of the RelBE, RelBE5, and VapBC systems was increased during macrophage infection (Silva-Herzog, McDonald, Crooks, & Detweiler, 2015). Another group demonstrated that all 14 type II TA systems in S. Typhimurium were upregulated within 30 minutes of infecting bone marrow-derived macrophages (Helaine et al., 2014).

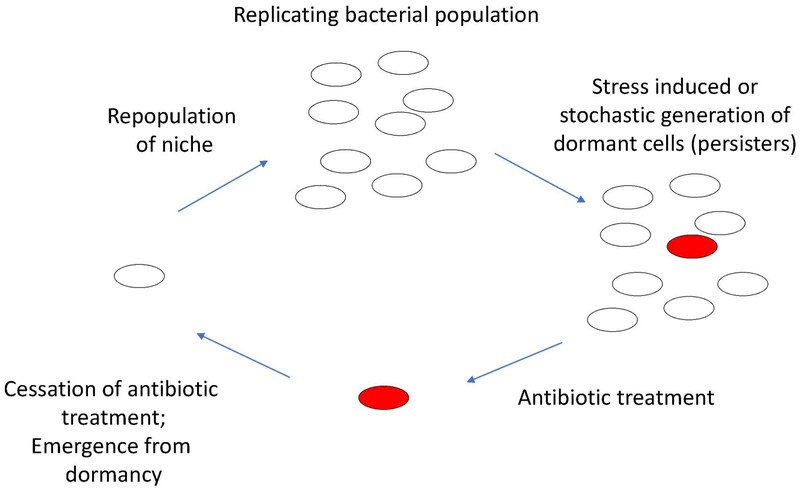

Bacterial persistence

Bacterial persistence is a phenomenon where bacteria enter into a dormant state, allowing non-replicating organisms to survive during stressful environmental conditions or treatment with antibiotics (Figure 4). This is of particular concern in pathogenic bacteria, as it may lead to antibiotic tolerance and recurrent infections (M. A. Schumacher et al., 2015). Antibiotic tolerance is attributed to the non-growing state of persister cells, as the cellular targets of most antibiotics are inactive during dormancy. A range of genetic pathways may contribute to the formation of persister cells, including metabolic flux, decreases in cellular ATP levels, upregulation of efflux pumps, and activation of TA systems (Amato, Orman, & Brynildsen, 2013; Maisonneuve, Castro-Camargo, & Gerdes, 2013; Maisonneuve, Shakespeare, Jorgensen, & Gerdes, 2011; Pu et al., 2016; Radzikowski et al., 2016; Shan et al., 2017).

Figure 4 –

Bacterial persistence. Persisters (red) develop within a replicating bacterial population through either stress induced or stochastically generated dormant cells, called persisters. These dormant bacteria are tolerant to antibiotic treatment, as most antibiotics target actively growing cells. Upon completion of antibiotic treatment, the dormant bacteria resume growth and repopulate the niche.

A variety of upstream signals regulate these bacterial persistence pathways. One well-studied mechanism is the stringent response and (p)ppGpp signalling, which is typically activated during nutrient deprivation. (p)ppGpp is an alarmone and second messenger of the stringent response that triggers a shift from active growth of the bacteria to metabolic inactivity and survival. Inability to produce (p)ppGpp leads to a decrease in bacterial persistence in many different bacterial species (Alexander Harms, Maisonneuve, & Gerdes, 2016; Maisonneuve et al., 2013; Maisonneuve et al., 2011). However, the mechanism of (p)ppGpp-induced persistence is not clear, and recent studies failed to find a specific role in persistence (Chowdhury, Kwan, & Wood, 2016; Shan et al., 2017). Additionally, RpoS and the general stress response can trigger bacterial persistence, typically in response to stress conditions during stationary phase (Hansen, Lewis, & Vulic, 2008; Hong, Wang, O’Connor, Benedik, & Wood, 2012; Stewart et al., 2015). Similarly, the SOS response and quorum sensing peptides have also been shown to influence bacterial persistence (Bernier et al., 2013; Dörr, Vulić, & Lewis, 2010; Hu, Kwan, Osbourne, Benedik, & Wood, 2015; Kolodkin-Gal, Hazan, Gaathon, Carmeli, & Engelberg-Kulka, 2007; Leung & Levesque, 2012; Völzing & Brynildsen, 2015). A caveat to many of these approaches is that any treatment that causes a reversible, non-replicating state will favour stress tolerance and bacterial survival in the face of treatments that only kill replicating cells. TA systems have been widely described as playing a role in dormancy, leading to bacterial persistence (Alexander Harms et al., 2016; Maisonneuve & Gerdes, 2014). The first evidence for toxin-induced persistence was identified in the HipAB system, as mutations in HipA led to increased persistence (Black, Irwin, & Moyed, 1994; Black, Kelly, Mardis, & Moyed, 1991; Korch, Henderson, & Hill, 2003; Moyed & Bertrand, 1983). Sequential deletion of 10 type II TA systems in E. coli decreased persister formation (Maisonneuve et al., 2011). In S. typhimurium, deletion of any one of the 14 type II TA systems decreased the percentage of persisters during macrophage infection (Helaine et al., 2014). Work from the Gerdes lab lent support to a model of TA-dependent persistence. They demonstrated that within a population of E. coli, a small population of cells enters stochastically into a dormant state due to the production of high levels of (p)ppGpp, which activates the Lon protease (Maisonneuve et al., 2013). Lon degrades the antitoxin component of TA systems, liberating the toxin, which induces dormancy and subsequent antibiotic tolerance (Maisonneuve et al., 2013). Later work demonstrated that activation of the HipA toxin increased production of (p)ppGpp, which stimulated induction of the other ten TA systems in E. coli, resulting in bacterial persistence (E. Germain et al., 2013; Elsa Germain, Roghanian, Gerdes, & Maisonneuve, 2015; Korch et al., 2003).

However, the role of TA systems in causing the persistence phenotype remains controversial. Other groups were not able to replicate the results described by Maisonneuve et al in 2011 suggesting TA systems lead to persistence. Some experiments using E. coli with 10 TA systems deleted demonstrated no change in persistence (Ramisetty, Ghosh, Roy Chowdhury, & Santhosh, 2016; Shan et al., 2017). Recently, the Gerdes lab published work demonstrating that their previous results were an artefact of the 10TA deletion strain carrying a ϕ80 bacteriophage lysogen (A. Harms, Fino, Sorensen, Semsey, & Gerdes, 2017). When experiments were repeated using a non-infected strain of E. coli, the TA systems appeared to play no role in persistence; however, (p)ppGpp and Lon protease still appeared important for persistence (A. Harms et al., 2017). Other work found that persistence of E. coli, S. aureus, and M. smegmatis following treatment with quinolone antibiotics was dependent on respiratory metabolism suggesting that the phenomena depends on the growth stage of the cells (Gutierrez et al., 2017).

MECHANISMS OF GROWTH INHIBITION BY TARGETING tRNAS

Of the six types of TA systems, the type II systems are the most prevalent (Pandey & Gerdes, 2005). For example, there are 88 type II TA systems in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) (Ramage et al., 2009). These systems primarily target translation as a means of inhibiting bacterial growth; however, some have been found to inhibit replication (E. Germain et al., 2013; Guglielmini & Van Melderen, 2011; Jiang, Pogliano, Helinski, & Konieczny, 2002; Maki, Takiguchi, Miki, & Horiuchi, 1992; K. S. Winther & Gerdes, 2011; Y. Zhang et al., 2003). Thus, type II system toxins are classified into families based on their mechanisms of activity (Table 1). Within these families, a number of toxins inhibit translation by either direct or indirect targeting of tRNAs.

Table 1 –

Type II toxin families. Type II toxin families classified by their mechanism of activity. The target of each toxin is listed, as well as the activity of the toxin on its target. Finally, the table lists the cellular process that is inhibited to cause growth arrest.

| Toxin | Target | Activity | Cellular Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| VapC | tRNA, rRNA | Endoribonuclease | Translation |

| TacT/AtaT | tRNA | Acetyltransferase | Translation |

| MazF | mRNA, rRNA, tRNA | Endoribonuclease | Translation |

| HipA | Glutamyl-tRNA synthetase | Protein kinase | Translation |

| Doc | EF-Tu | Protein Kinase | Translation |

| RelE | Translating ribosome | Induces mRNA cleavage | Translation |

| HicA | mRNA | Endoribonuclease | Translation |

| Kid | mRNA | Endoribonuclease | Translation |

| CcdB | DNA gyrase | Generates DS breaks | Replication |

| ParE | DNA gyrase | Generates DS breaks | Replication |

Phosphorylation of tRNA synthetase

The HipA family of toxins act as phosphoryltransferases. Studies in vitro suggested that HipA inhibits translation through phosphorylation of elongation factor (EF)-Tu (M. A. Schumacher et al., 2009). However, another lab employed a genetic screen using the E. coli ASKA library from the E. coli to search for suppressors of HipA toxicity and found that only overexpression of glutamyl-tRNA synthetase reversed HipA-induced growth inhibition (E. Germain et al., 2013; Kaspy et al., 2013). These studies further showed that HipA phosphorylates glutamyl-tRNA synthetase, resulting in uncharged tRNAs that prevent translation (E. Germain et al., 2013; Kaspy et al., 2013).

Acetylation of tRNA

The Gcn5 N-acetyltransferase (GNAT) family of toxins includes the TacT toxins, identified in S. Typhimurium, and the AtaT toxin from E. coli (Cheverton et al., 2016; Jurėnas et al., 2017; Rycroft et al., 2018). S. Typhimurium encodes three TacAT systems and single deletions of each of these systems resulted in a decrease in persistence during macrophage infection compared to wildtype (Helaine et al., 2014). The TacT toxins inhibit translation through acetylation of the primary amino groups on aminoacyl-tRNAs (Cheverton et al., 2016; Rycroft et al., 2018). The downstream mechanism of TacT-induced translation inhibition by tRNA acetylation was not investigated in these studies. However, acetylation likely prevents interaction of tRNAs with EF-Tu, as has been previously shown for chemically acetylated tRNAs (Janiak et al., 1990). Experiments in vitro suggest that acetylation by TacT toxins affects the majority of tRNA isotypes, with some preference for tRNAGly, tRNALeu, and tRNAIle (Rycroft et al., 2018). In contrast, AtaT from E. coli specifically acetylates the amino group of charged, but not yet formylated initiator tRNAfMet (Jurėnas et al., 2017). This acetylation prevents the interaction of tRNAfMet with initiation factor 2 (IF2), thereby disrupting translation initiation (Jurėnas et al., 2017).

tRNA cleavage

The MazF family of endoribonucleases was originally thought to inhibit translation through sequence-specific cleavage of mRNA at ACA sites (Park, Yoshizumi, Yamaguchi, Wu, & Inouye, 2013; Rothenbacher et al., 2012; J. Zhang, Zhang, Zhu, Suzuki, & Inouye, 2004; Y. Zhang et al., 2003). Work by Vesper et al later showed that this toxin can also cleave 16S rRNA removing the 3’ end containing the anti-Shine-Dalgarno sequence, which was proposed to allow translation of leaderless mRNAs resulting from MazF cleavage (Schifano et al., 2014; Vesper et al., 2011). However, recent findings suggest that E. coli MazF does not produce significant amounts of leaderless mRNAs, nor does it cleave the anti-Shine-Dalgarno sequence from 16S rRNA (Culviner & Laub, 2018). Rather, it appears that MazF primarily cleaves precursor rRNAs, preventing RNA maturation and ribosome biogenesis (Culviner & Laub, 2018). MazF-mt6 and -mt3 from M. tuberculosis appear to cleave 23S rRNA at the ribosomal A site, as well as mRNA (Schifano et al., 2013; Schifano et al., 2014). However, using a modified RNA-Seq method, Schifano et al identified that MazF-mt9 from M. tuberculosis cleaves two tRNAs, tRNAPro14 and tRNALys43 (Schifano et al., 2016). MazF-mt9 cleaves specifically at UUU sites, in the anticodon loop of tRNALys43 and the D-loop of tRNAPro14 respectively (Schifano et al., 2016). Apart from sequence specificity, cleavage by this toxin also depends on the stem-loop structure (Schifano et al., 2016).

Finally, the VapC toxin family members act as endoribonucleases that cleave either tRNAs or rRNAs (Cruz & Woychik, 2016). These systems are discussed in further detail below.

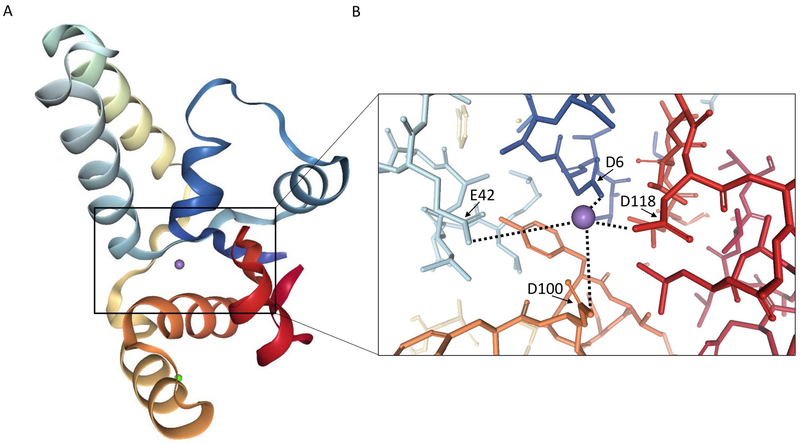

VAPBC SYSTEMS

Among type II systems, the VapBC system is the most abundant and consists of a VapB antitoxin and a VapC toxin (Pandey & Gerdes, 2005). The VapC toxin is a PIN (PilT N-terminus) domain endoribonuclease that inhibits translation through cleavage of RNAs (Figure 5) (Arcus, McKenzie, Robson, & Cook, 2011). PIN domain proteins are found in all domains of life and play a role in RNA processing, as well as RNA quality control and decay (Bleichert, Granneman, Osheim, Beyer, & Baserga, 2006; Huntzinger, Kashima, Fauser, Saulière, & Izaurralde, 2008; Lamanna & Karbstein, 2009; Schneider, Leung, Brown, & Tollervey, 2009). The PIN domain contains four highly conserved acidic amino acid residues, which coordinate a Mg2+ ion in the active site, allowing for hydrolytic cleavage of RNA (Figure 5).

Figure 5 –

VapC toxin structure and active site. (A) Crystal structure of VapC from Pyrobaculum aerophilum, including Mg2+ ion (purple) in the active site (Bunker, McKenzie, Baker, & Arcus, 2008). (B) View of the VapC active site containing a Mg2+ ion. Conserved PIN domain active site amino acid side chains are identified (arrows). Mg2+ ion is coordinated in the active site by the indicated carboxylate side chain oxygen atoms as well as water molecules. Images were produced using the RCSB Protein Data Bank, PDB ID: 2FE1 (Rose et al., 2016; Rose & Hildebrand, 2015).

The RNA targets of several VapC toxins have been identified from different organisms and these toxins typically cleave either tRNAs or rRNA (Table 2). The VapC toxins from Salmonella enterica, Shigella flexneri, and Leptospira interrogans all cleave initiator tRNAfMet in the anticodon loop (Lopes et al., 2014; K. S. Winther & Gerdes, 2011). Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae encodes two VapC toxins, VapC1 and VapC2, both of which also cleave tRNAfMet in the anticodon loop (Walling & Butler, 2018). In M. tuberculosis, there are 47 VapBC systems (Ramage et al., 2009). A large number of these toxins cleave several different tRNAs, such as tRNACys-GCA (VapC4), tRNALeu-CAG (VapC11, VapC15, and VapC32), tRNASer-TGA,CGA (VapC28, VapC30), and tRNATrp-CCA (VapC25, VapC33, VapC37, VapC29, and VapC39) (K. Winther, Tree, Tollervey, & Gerdes, 2016). On the other hand, VapC20 and VapC26 from M. tuberculosis both cleave 23S rRNA in the sarcin-ricin loop (K. Winther et al., 2016; K. S. Winther et al., 2013).

Table 2 –

Known targets of VapC toxins. VapC toxins from multiple organisms are listed, along with the RNA target that has been identified for each.

| Toxin | Organism | RNA Target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| VapC20,26 | M. tuberculosis | 23S rRNA |

Winther, Brodersen et al. 2013, Winther, Tree et al. 2016 |

| VapC4 | M. tuberculosis | tRNACys | Cruz, Sharp et al. 2015 |

| VapC11, 15,32 | M. tuberculosis | tRNALeu | Winther, Tree et al. 2016 |

| VapC28,30 | M. tuberculosis | tRNASer | Winther, Tree et al. 2016 |

| VapC25,29,33,37,39 | M. tuberculosis | tRNATrp | Winther, Tree et al. 2016 |

| VapCLT2 | S. enterica | tRNAfMet | Winther and Gerdes 2011 |

| VapC | S. flexneri | tRNAfMet | Winther and Gerdes 2011 |

| VapC | L. interrogans | tRNAfMet | Lopes, Lopes et al. 2014 |

| VapC1, C2 | NTHi | tRNAfMet | Walling and Butler 2018 |

TARGET SPECIFICITY OF tRNA TOXINS

Toxins that target tRNAs vary in their range of specificities, as some are very broad while others specifically target a single tRNA. The TacT toxin from S. Typhimurium has a relaxed specificity and acetylates the majority of tRNAs, with slight preferences for tRNAGly, tRNALeu, and tRNAIle (Cheverton et al., 2016; Rycroft et al., 2018). In contrast, another GNAT family toxin, AtaT, only acetylates initiator tRNAfMet (Jurėnas et al., 2017). It is not yet known how AtaT differentiates tRNAfMet from other tRNAs for acetylation. The HipA toxin phosphorylates glutamyl-tRNA synthetase and so is highly specific for tRNAGlu (E. Germain et al., 2013). The endoribonuclease toxin MazF-mt9 specifically cleaves tRNAPro14 in the D-loop and tRNALys43 in the anticodon loop at UUU sequences (Schifano et al., 2016). VapC toxins also cleave specific tRNAs, however, the tRNA that is cleaved varies depending on the organism and which VapC toxin is being studied (Cruz et al., 2015; Lopes et al., 2014; Walling & Butler, 2018; K. Winther et al., 2016; K. S. Winther & Gerdes, 2011).

For the majority of the toxins described above that target specific tRNAs, the manner in which they distinguish one tRNA from another is not well understood. However, in the case of endoribonuclease toxins, some work has been done to identify the specificity determinants that allow for recognition by the toxin (Masuda & Inouye, 2017). For example, in M. tuberculosis, VapC20 required both specific sequence and structural components in the sarcin-ricin loop to cleave 23S rRNA (K. S. Winther et al., 2013). Mutating certain nucleotides at the target site abolished cleavage, as did mutations that disrupted the stem-loop structure of the sarcin-ricin loop (K. S. Winther et al., 2013). The specificity of the MazF-mt9 toxin for cleavage of tRNALys43 also depends on both sequence and structural determinants (Schifano et al., 2016). Mutations of the UUU cleavage site or disrupting the stem-loop structure containing the anticodon, prevented cleavage of tRNALys43 by MazF-mt9 (Schifano et al., 2016).

Cleavage of tRNAfMet by VapC1 and VapC2 from nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae depends, in part, on the sequence of the anticodon stem (Walling & Butler, 2018). Mutating the G-C pair at the junction of the anticodon stem and loop resulted in a significant decrease in cleavage of tRNAfMet (Walling & Butler, 2018). Additionally, changing the anticodon stem of the non-substrate elongator tRNAMet to match that of tRNAfMet resulted in cleavage by VapC1 and VapC2 (Walling & Butler, 2018). This sequence specificity is unique when compared to that of VapC20 or MazF-mt9, which depend on specific sequences at the site of cleavage. This is not the case for VapC1 and VapC2 because they do not cleave elongator tRNAMet despite the exact match of its anticodon loop to that of tRNAfMet. In contrast, the NTHi VapCs cleavage of tRNAfMet in the anticodon loop requires a G-C pair located in the anticodon stem. However, mutation of the anticodon stem of elongator tRNAMet to match that of initiator tRNAfMet resulted in less efficient cleavage by the VapC toxins compared to initiator tRNAfMet (Walling & Butler, 2018). This suggests that additional sequence or structural elements are required for efficient VapC1 and VapC2 cleavage outside of the anticodon stem-loop (Walling & Butler, 2018).

REVERSAL OF DORMANCY

While the mechanisms of toxin-induced growth arrest by targeting tRNAs are well-studied for many bacterial TA systems, the mechanisms that promote emergence from dormancy are not well characterized (Hall, Gollan, & Helaine, 2017). For example, control of HipA activity has been studied, yet reversal of HipA-induced dormancy remains poorly understood. Evidence suggests that autophosphorylation of HipA inactivates its protein kinase activity (Maria A. Schumacher et al., 2012). Additionally, structural analysis indicates that sequestration of HipA in complex with HipB on the promoter region is required to prevent HipA toxicity (M. A. Schumacher et al., 2015).

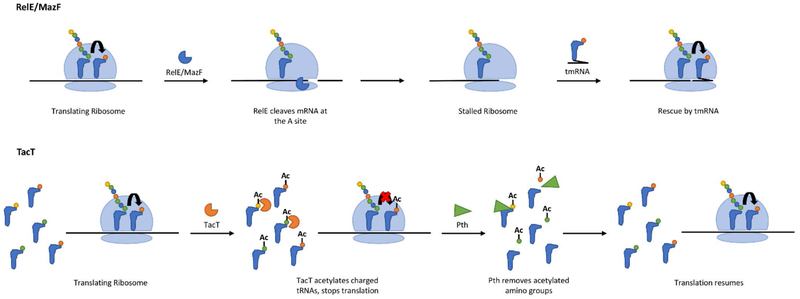

Both RelE and MazF toxins cleave mRNAs, leading to stalled ribosomes, which inhibits translation. Studies suggest that growth arrest by these toxins is reversed by tmRNA rescue of stalled ribosomes (Christensen & Gerdes, 2003; Christensen et al., 2003; Culviner & Laub, 2018). tmRNAs function as both an mRNA and a tRNA, which can insert into the A site of a stalled ribosome (Figure 6). After peptidyl transfer has occurred, translation resumes using the mRNA component of the tmRNA, which encodes a tag that targets the truncated peptide for proteolysis (Buskirk & Green, 2017; Himeno, Kurita, & Muto, 2014; Keiler, Waller, & Sauer, 1996; Moore & Sauer, 2007).

Figure 6 –

Reversal of toxin-induced dormancy. RelE and MazF – stalled ribosomes, caused by RelE/MazF cleavage of mRNA in the ribosomal A site, are rescued by tmRNA. TacT – the primary amino group of tRNA is acetylated by TacT, inhibiting translation. Peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase (Pth) removes the acetylated amino groups, allowing translation to resume.

The TacT toxins in S. Typhimurium, described above, are acetyltransferases that inhibit translation through the acetylation of the amino groups on charged tRNAs. This activity can be reversed by the activity of a peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase (Pth) in the bacteria, which detoxifies the tRNA pool by removing acetylated amino groups from the tRNA allowing cell growth to resume (Figure 6) (Cheverton et al., 2016; Rycroft et al., 2018).

The mechanisms of resuscitation after growth arrest caused by tRNA cleavage have not been identified to date. However, the RNA ligase RtcB can rescue growth arrest due to RNA cleavage by the MazF toxin in E. coli apparently by re-ligating the cleavage fragments of the 16S rRNA (Figure 6) (Temmel et al., 2017). Cleavage of mRNA and rRNA by MazF appears to reprogram the translational profile of E. coli, resulting in preferential translation of a subset of mRNAs that are not cleaved by MazF cleavage (Culviner & Laub, 2018; Vesper et al., 2011). It is possible that a similar phenomenon occurs in the case of toxins that specifically target tRNAfMet. Studies have demonstrated that when cellular levels of tRNAfMet are low, elongator tRNAs have the ability to initiate translation (Kapoor, Das, & Varshney, 2011; Samhita, Virumäe, Remme, & Varshney, 2013). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that by reducing the levels of tRNAfMet available to initiate translation, the toxin may shift the bacteria’s translational profile to favour translation of mRNAs that can be initiated using elongator tRNAs. This phenomenon may occur in E. coli expressing the VapC or VapCLT2 toxins from S. flexnerii or S. enterica, respectively. When either toxin was expressed, a plasmid-encoded transcript that initiated with tRNAfMet was not translated (K. S. Winther & Gerdes, 2011). However, toxin expression allowed for translation when the transcript initiated with an AAG codon rather than AUG (K. S. Winther & Gerdes, 2011). Further work will be required to determine whether this is a widespread mechanism of translational reprogramming of chromosomally encoded transcripts and whether this occurs with other TA systems targeting tRNAfMet.

Conclusion

Toxin-antitoxin systems clearly play an important role in the establishment and maintenance of bacterial dormancy. However, for many TA systems, the biological importance of this dormancy is not fully understood. While some systems clearly function in post-segregational killing, phage abortive infection systems, or stress responses, their role in bacterial persistence requires further investigation. The methods used to measure persistence need to be carefully re-evaluated, as studies have demonstrated that the number of persisters measured is affected by growth rate, metabolism, and the presence of lysogenic phage (Gutierrez et al., 2017; A. Harms et al., 2017).

While several TA systems target tRNAs to inhibit translation, they do so by a variety of mechanisms. The TacT and AtaT systems acetylate tRNAs, while the VapC toxins and MazF-mt9 cleave them. In contrast, the HipA toxins phosphorylate and inactivate glutamyl-tRNA synthetase. These toxins have varying specificities as well – VapC, HipA, and AtaT toxins target one specific tRNA, while MazF-mt9 targets two and TacT acetylates multiple tRNAs. Further studies will help us understand how these toxins specifically target their substrate tRNAs. Mutational analysis suggests that sequence and structural features are necessary for VapC20 from M. tuberculosis, VapC1 and VapC2 from NTHi, and MazF-mt9 to cleave their substrate tRNAs. However, the specificity determinants of most other toxins for their tRNA targets remain uncharacterized.

Many studies have elucidated the mechanisms used by TA systems to cause growth arrest and dormancy. For type II systems, these range from RNA cleavage and phosphorylation of factors important for translation, to inhibiting DNA gyrase activity. However, mechanisms for repairing toxin-induced damage and subsequent emergence from toxin-induced growth arrest have not been determined for the majority of TA systems. Studies suggest that toxicity due to the RelE and MazF toxins, which cleave mRNAs resulting in stalled ribosomes, may be rescued by tmRNAs, which recycle stalled ribosomes (Christensen & Gerdes, 2003; Christensen et al., 2003). The TacT toxins inhibit translation through acetylation of the amino group of tRNAs. Peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase (Pth) removes acetylated amino groups from these tRNAs, allowing translation to resume (Cheverton et al., 2016; Rycroft et al., 2018). However, for the majority of TA systems, the mechanisms of resuming growth are not well characterized and further studies should focus on understanding the reversal of toxin-induced dormancy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants GM099731 (J.S.B.), T32-GM068411 (L.R.W.), and T32-AI118689 (L.R.W.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Lauren R. Walling, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, USA, Lauren_Rice@urmc.rochester.edu

J. Scott Butler, Departments of Microbiology and Immunology, and Biochemistry and Biophysics, and Center for RNA Biology, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, USA, Scott_Butler@urmc.rochester.edu

References

- Aakre Christopher D., Phung Tuyen N., Huang D, & Laub Michael T. (2013). A Bacterial Toxin Inhibits DNA Replication Elongation through a Direct Interaction with the β Sliding Clamp. Mol Cell, 52(5), 617–628. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato Stephanie M., Orman Mehmet A., & Brynildsen Mark P. (2013). Metabolic Control of Persister Formation in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell, 50(4), 475–487. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcus VL, McKenzie JL, Robson J, & Cook GM (2011). The PIN-domain ribonucleases and the prokaryotic VapBC toxin–antitoxin array. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection, 24(1–2), 33–40. doi:10.1093/protein/gzq081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier SP, Lebeaux D, DeFrancesco AS, Valomon A, Soubigou G, Coppee JY, . . . Beloin C (2013). Starvation, together with the SOS response, mediates high biofilm-specific tolerance to the fluoroquinolone ofloxacin. PLoS Genet, 9(1), e1003144. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DS, Irwin B, & Moyed HS (1994). Autoregulation of hip, an operon that affects lethality due to inhibition of peptidoglycan or DNA synthesis. J Bacteriol, 176(13), 4081–4091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DS, Kelly AJ, Mardis MJ, & Moyed HS (1991). Structure and organization of hip, an operon that affects lethality due to inhibition of peptidoglycan or DNA synthesis. J Bacteriol, 173(18), 5732–5739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleichert F, Granneman S, Osheim YN, Beyer AL, & Baserga SJ (2006). The PINc domain protein Utp24, a putative nuclease, is required for the early cleavage steps in 18S rRNA maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103(25), 9464–9469. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603673103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blohm D, & Goebel W (1978). Restriction map of the antibiotic resistance plasmid R1drd-19 and its derivatives pKN102 (R1drd-19B2) and R1drd-16 for the enzymes BamHI, HindIII, EcoRI and SalI. Mol Gen Genet, 167(2), 119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blower TR, Evans TJ, Przybilski R, Fineran PC, & Salmond GP (2012). Viral evasion of a bacterial suicide system by RNA-based molecular mimicry enables infectious altruism. PLoS Genet, 8(10), e1003023. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blower TR, Fineran PC, Johnson MJ, Toth IK, Humphreys DP, & Salmond GP (2009). Mutagenesis and functional characterization of the RNA and protein components of the toxIN abortive infection and toxin-antitoxin locus of Erwinia. J Bacteriol, 191(19), 6029–6039. doi:10.1128/jb.00720-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blower TR, Pei XY, Short FL, Fineran PC, Humphreys DP, Luisi BF, & Salmond GP (2011). A processed noncoding RNA regulates an altruistic bacterial antiviral system. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 18(2), 185–190. doi:10.1038/nsmb.1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blower TR, Short FL, Rao F, Mizuguchi K, Pei XY, Fineran PC, . . . Salmond GP (2012). Identification and classification of bacterial Type III toxin-antitoxin systems encoded in chromosomal and plasmid genomes. Nucleic Acids Res, 40(13), 6158–6173. doi:10.1093/nar/gks231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggild A, Sofos N, Andersen KR, Feddersen A, Easter AD, Passmore LA, & Brodersen DE (2012). The crystal structure of the intact E. coli RelBE toxin-antitoxin complex provides the structural basis for conditional cooperativity. Structure, 20(10), 1641–1648. doi:10.1016/j.str.2012.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, & Shaw KJ (2003). A novel family of Escherichia coli toxin-antitoxin gene pairs. J Bacteriol, 185(22), 6600–6608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunker RD, McKenzie JL, Baker EN, & Arcus VL (2008). Crystal structure of PAE0151 from Pyrobaculum aerophilum, a PIN-domain (VapC) protein from a toxin-antitoxin operon. Proteins, 72(1), 510–518. doi:10.1002/prot.22048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buskirk AR, & Green R (2017). Ribosome pausing, arrest and rescue in bacteria and eukaryotes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 372(1716). doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataudella I, Sneppen K, Gerdes K, & Mitarai N (2013). Conditional cooperativity of toxin - antitoxin regulation can mediate bistability between growth and dormancy. PLoS Comput Biol, 9(8), e1003174. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataudella I, Trusina A, Sneppen K, Gerdes K, & Mitarai N (2012). Conditional cooperativity in toxin-antitoxin regulation prevents random toxin activation and promotes fast translational recovery. Nucleic Acids Res, 40(14), 6424–6434. doi:10.1093/nar/gks297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheverton Angela M., Gollan B, Przydacz M, Wong Chi T., Mylona A, Hare Stephen A., & Helaine S (2016). A Salmonella Toxin Promotes Persister Formation through Acetylation of tRNA. Mol Cell, 63(1), 86–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury N, Kwan BW, & Wood TK (2016). Persistence Increases in the Absence of the Alarmone Guanosine Tetraphosphate by Reducing Cell Growth. Sci Rep, 6, 20519. doi:10.1038/srep20519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK, & Gerdes K (2003). RelE toxins from bacteria and Archaea cleave mRNAs on translating ribosomes, which are rescued by tmRNA. Mol Microbiol, 48(5), 1389–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen SK, Pedersen K, Hansen FG, & Gerdes K (2003). Toxin-antitoxin loci as stress-response-elements: ChpAK/MazF and ChpBK cleave translated RNAs and are counteracted by tmRNA. J Mol Biol, 332(4), 809–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chukwudi CU, & Good L (2015). The role of the hok/sok locus in bacterial response to stressful growth conditions. Microbial Pathogenesis, 79, 70–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CR, Daugherty AJ, Tachdjian S, Blum PH, & Kelly RM (2009). Role of vapBC toxin-antitoxin loci in the thermal stress response of Sulfolobus solfataricus. Biochem Soc Trans, 37(Pt 1), 123–126. doi:10.1042/bst0370123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TF, & Heinemann JA (2000). Postsegregational killing does not increase plasmid stability but acts to mediate the exclusion of competing plasmids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(23), 12643–12648. doi:10.1073/pnas.220077897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JW, Sharp JD, Hoffer ED, Maehigashi T, Vvedenskaya IO, Konkimalla A, . . . Woychik NA (2015). Growth-regulating Mycobacterium tuberculosis VapC-mt4 toxin is an isoacceptor-specific tRNase. Nat Commun, 6, 7480. doi:10.1038/ncomms8480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JW, & Woychik NA (2016). tRNAs taking charge. Pathog Dis, 74(2). doi:10.1093/femspd/ftv117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culviner PH, & Laub MT (2018). Global Analysis of the E. coli Toxin MazF Reveals Widespread Cleavage of mRNA and the Inhibition of rRNA Maturation and Ribosome Biogenesis. Mol Cell. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2018.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darfeuille F, Unoson C, Vogel J, & Wagner EG (2007). An antisense RNA inhibits translation by competing with standby ribosomes. Mol Cell, 26(3), 381–392. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienemann C, Boggild A, Winther KS, Gerdes K, & Brodersen DE (2011). Crystal structure of the VapBC toxin-antitoxin complex from Shigella flexneri reveals a hetero-octameric DNA-binding assembly. J Mol Biol, 414(5), 713–722. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2011.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörr T, Vulić M, & Lewis K (2010). Ciprofloxacin Causes Persister Formation by Inducing the TisB toxin in Escherichia coli. PLOS Biology, 8(2), e1000317. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dy RL, Przybilski R, Semeijn K, Salmond GPC, & Fineran PC (2014). A widespread bacteriophage abortive infection system functions through a Type IV toxin–antitoxin mechanism. Nucleic Acids Research, 42(7), 4590–4605. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dy RL, Richter C, Salmond GPC, & Fineran PC (2014). Remarkable Mechanisms in Microbes to Resist Phage Infections. Annual Review of Virology, 1(1), 307–331. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineran PC, Blower TR, Foulds IJ, Humphreys DP, Lilley KS, & Salmond GP (2009). The phage abortive infection system, ToxIN, functions as a protein-RNA toxin-antitoxin pair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 106(3), 894–899. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808832106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineran PC, Blower TR, Foulds IJ, Humphreys DP, Lilley KS, & Salmond GPC (2009). The phage abortive infection system, ToxIN, functions as a protein–RNA toxin–antitoxin pair. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(3), 894–899. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808832106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K, Bech FW, Jørgensen ST, Løbner-Olesen A, Rasmussen PB, Atlung T, . . . von Meyenburg K (1986). Mechanism of postsegregational killing by the hok gene product of the parB system of plasmid R1 and its homology with the relF gene product of the E. coli relB operon. The EMBO Journal, 5(8), 2023–2029. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04459.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K, Rasmussen PB, & Molin S (1986). Unique type of plasmid maintenance function: postsegregational killing of plasmid-free cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 83(10), 3116–3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K, Thisted T, & Martinussen J (1990). Mechanism of post-segregational killing by the hoklsok system of plasmid R1: sok antisense RNA regulates formation of a hok mRNA species correlated with killing of plasmid-free cells. Molecular Microbiology, 4(11), 1807–1818. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain E, Castro-Roa D, Zenkin N, & Gerdes K (2013). Molecular mechanism of bacterial persistence by HipA. Mol Cell, 52(2), 248–254. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain E, Roghanian M, Gerdes K, & Maisonneuve E (2015). Stochastic induction of persister cells by HipA through (p)ppGpp-mediated activation of mRNA endonucleases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(16), 5171–5176. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423536112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Goeders N, Chai R, Chen B, Day A, & Salmond GP (2016). Structure, Evolution, and Functions of Bacterial Type III Toxin-Antitoxin Systems. Toxins (Basel), 8(10). doi:10.3390/toxins8100282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmini J, & Van Melderen L (2011). Bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems: Translation inhibitors everywhere. Mob Genet Elements, 1(4), 283–290. doi:10.4161/mge.18477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez A, Jain S, Bhargava P, Hamblin M, Lobritz MA, & Collins JJ (2017). Understanding and Sensitizing Density-Dependent Persistence to Quinolone Antibiotics. Mol Cell, 68(6), 1147–1154.e1143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2017.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AMJ, Gollan B, & Helaine S (2017). Toxin–antitoxin systems: reversible toxicity. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 36, 102–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S, Lewis K, & Vulic M (2008). Role of global regulators and nucleotide metabolism in antibiotic tolerance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 52(8), 2718–2726. doi:10.1128/aac.00144-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms A, Brodersen DE, Mitarai N, & Gerdes K (2018). Toxins, Targets, and Triggers: An Overview of Toxin-Antitoxin Biology. Mol Cell, 70(5), 768–784. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms A, Fino C, Sorensen MA, Semsey S, & Gerdes K (2017). Prophages and Growth Dynamics Confound Experimental Results with Antibiotic-Tolerant Persister Cells. MBio, 8(6). doi:10.1128/mBio.01964-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms A, Maisonneuve E, & Gerdes K (2016). Mechanisms of bacterial persistence during stress and antibiotic exposure. Science, 354(6318). doi:10.1126/science.aaf4268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan R, & Engelberg-Kulka H (2004). Escherichia coli mazEF-mediated cell death as a defense mechanism that inhibits the spread of phage P1. Mol Genet Genomics, 272(2), 227–234. doi:10.1007/s00438-004-1048-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helaine S, Cheverton AM, Watson KG, Faure LM, Matthews SA, & Holden DW (2014). Internalization of Salmonella by Macrophages Induces Formation of Nonreplicating Persisters. Science, 343(6167), 204–208. doi:10.1126/science.1244705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himeno H, Kurita D, & Muto A (2014). tmRNA-mediated trans-translation as the major ribosome rescue system in a bacterial cell. Front Genet, 5, 66. doi:10.3389/fgene.2014.00066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SH, Wang X, O’Connor HF, Benedik MJ, & Wood TK (2012). Bacterial persistence increases as environmental fitness decreases. Microb Biotechnol, 5(4), 509–522. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7915.2011.00327.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Benedik MJ, & Wood TK (2012). Antitoxin DinJ influences the general stress response through transcript stabilizer CspE. Environmental Microbiology, 14(3), 669–679. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02618.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Kwan BW, Osbourne DO, Benedik MJ, & Wood TK (2015). Toxin YafQ increases persister cell formation by reducing indole signalling. Environmental Microbiology, 17(4), 1275–1285. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger E, Kashima I, Fauser M, Saulière J, & Izaurralde E (2008). SMG6 is the catalytic endonuclease that cleaves mRNAs containing nonsense codons in metazoan. Rna, 14(12), 2609–2617. doi:10.1261/rna.1386208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiak F, Dell VA, Abrahamson JK, Watson BS, Miller DL, & Johnson AE (1990). Fluorescence characterization of the interaction of various transfer RNA species with elongation factor Tu.GTP: evidence for a new functional role for elongation factor Tu in protein biosynthesis. Biochemistry, 29(18), 4268–4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen BD, Garza-Sánchez F, & Hayes CS (2015). YoeB toxin is activated during thermal stress. MicrobiologyOpen, 4(4), 682–697. doi:10.1002/mbo3.272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Pogliano J, Helinski DR, & Konieczny I (2002). ParE toxin encoded by the broad-host-range plasmid RK2 is an inhibitor of Escherichia coli gyrase. Molecular Microbiology, 44(4), 971–979. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02921.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurėnas D, Chatterjee S, Konijnenberg A, Sobott F, Droogmans L, Garcia-Pino A, & Van Melderen L (2017). AtaT blocks translation initiation by N-acetylation of the initiator tRNAfMet. Nat Chem Biol, 13, 640. doi:10.1038/nchembio.234610.1038/nchembio.2346https://www.nature.com/articles/nchembio.2346#supplementary-informationhttps://www.nature.com/articles/nchembio.2346#supplementary-information [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor S, Das G, & Varshney U (2011). Crucial contribution of the multiple copies of the initiator tRNA genes in the fidelity of tRNA(fMet) selection on the ribosomal P-site in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res, 39(1), 202–212. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspy I, Rotem E, Weiss N, Ronin I, Balaban NQ, & Glaser G (2013). HipA-mediated antibiotic persistence via phosphorylation of the glutamyl-tRNA-synthetase. Nat Commun, 4, 3001. doi:10.1038/ncomms400110.1038/ncomms4001https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms4001#supplementary-informationhttps://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms4001#supplementary-information [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiler KC, Waller PR, & Sauer RT (1996). Role of a peptide tagging system in degradation of proteins synthesized from damaged messenger RNA. Science, 271(5251), 990–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodkin-Gal I, Hazan R, Gaathon A, Carmeli S, & Engelberg-Kulka H (2007). A linear pentapeptide is a quorum-sensing factor required for mazEF-mediated cell death in Escherichia coli. Science, 318(5850), 652–655. doi:10.1126/science.1147248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korch SB, Henderson TA, & Hill TM (2003). Characterization of the hipA7 allele of Escherichia coli and evidence that high persistence is governed by (p)ppGpp synthesis. Mol Microbiol, 50(4), 1199–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korch SB, Malhotra V, Contreras H, & Clark-Curtiss JE (2015). The Mycobacterium tuberculosis relBE toxin:antitoxin genes are stress-responsive modules that regulate growth through translation inhibition. J Microbiol, 53(11), 783–795. doi:10.1007/s12275-015-5333-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamanna AC, & Karbstein K (2009). Nob1 binds the single-stranded cleavage site D at the 3′-end of 18S rRNA with its PIN domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(34), 14259–14264. doi:10.1073/pnas.0905403106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung V, & Levesque CM (2012). A stress-inducible quorum-sensing peptide mediates the formation of persister cells with noninherited multidrug tolerance. J Bacteriol, 194(9), 2265–2274. doi:10.1128/jb.06707-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GW, Burkhardt D, Gross C, & Weissman JS (2014). Quantifying absolute protein synthesis rates reveals principles underlying allocation of cellular resources. Cell, 157(3), 624–635. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GY, Zhang Y, Inouye M, & Ikura M (2008). Structural mechanism of transcriptional autorepression of the Escherichia coli RelB/RelE antitoxin/toxin module. J Mol Biol, 380(1), 107–119. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes AP, Lopes LM, Fraga TR, Chura-Chambi RM, Sanson AL, Cheng E, . . . Martins EA (2014). VapC from the leptospiral VapBC toxin-antitoxin module displays ribonuclease activity on the initiator tRNA. PLoS One, 9(7), e101678. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E, Castro-Camargo M, & Gerdes K (2013). (p)ppGpp controls bacterial persistence by stochastic induction of toxin-antitoxin activity. Cell, 154(5), 1140–1150. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E, & Gerdes K (2014). Molecular mechanisms underlying bacterial persisters. Cell, 157(3), 539–548. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve E, Shakespeare LJ, Jorgensen MG, & Gerdes K (2011). Bacterial persistence by RNA endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108(32), 13206–13211. doi:10.1073/pnas.1100186108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Maki S, Takiguchi S, Miki T, & Horiuchi T (1992). Modulation of DNA supercoiling activity of Escherichia coli DNA gyrase by F plasmid proteins. Antagonistic actions of LetA (CcdA) and LetD (CcdB) proteins. J Biol Chem, 267(17), 12244–12251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H, & Inouye M (2017). Toxins of Prokaryotic Toxin-Antitoxin Systems with Sequence-Specific Endoribonuclease Activity. Toxins (Basel), 9(4). doi:10.3390/toxins9040140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H, Tan Q, Awano N, Wu KP, & Inouye M (2012). YeeU enhances the bundling of cytoskeletal polymers of MreB and FtsZ, antagonizing the CbtA (YeeV) toxicity in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol, 84(5), 979–989. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08068.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mate MJ, Vincentelli R, Foos N, Raoult D, Cambillau C, & Ortiz-Lombardia M (2012). Crystal structure of the DNA-bound VapBC2 antitoxin/toxin pair from Rickettsia felis. Nucleic Acids Res, 40(7), 3245–3258. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattison K, Wilbur JS, So M, & Brennan RG (2006). Structure of FitAB from Neisseria gonorrhoeae bound to DNA reveals a tetramer of toxin-antitoxin heterodimers containing pin domains and ribbon-helix-helix motifs. J Biol Chem, 281(49), 37942–37951. doi:10.1074/jbc.M605198200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SD, & Sauer RT (2007). The tmRNA system for translational surveillance and ribosome rescue. Annu Rev Biochem, 76, 101–124. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyed HS, & Bertrand KP (1983). hipA, a newly recognized gene of Escherichia coli K-12 that affects frequency of persistence after inhibition of murein synthesis. J Bacteriol, 155(2), 768–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuramalingam M, White JC, & Bourne CR (2016). Toxin-Antitoxin Modules Are Pliable Switches Activated by Multiple Protease Pathways. Toxins (Basel), 8(7). doi:10.3390/toxins8070214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito T, Kusano K, & Kobayashi I (1995). Selfish behavior of restriction-modification systems. Science, 267(5199), 897–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito Y, Naito T, & Kobayashi I (1998). Selfish restriction modification genes: resistance of a resident R/M plasmid to displacement by an incompatible plasmid mediated by host killing. Biol Chem, 379(4–5), 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overgaard M, Borch J, Jorgensen MG, & Gerdes K (2008). Messenger RNA interferase RelE controls relBE transcription by conditional cooperativity. Mol Microbiol, 69(4), 841–857. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page R, & Peti W (2016). Toxin-antitoxin systems in bacterial growth arrest and persistence. Nat Chem Biol, 12, 208. doi:10.1038/nchembio.2044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey DP, & Gerdes K (2005). Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res, 33(3), 966–976. doi:10.1093/nar/gki201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Yoshizumi S, Yamaguchi Y, Wu KP, & Inouye M (2013). ACA-specific RNA sequence recognition is acquired via the loop 2 region of MazF mRNA interferase. Proteins, 81(5), 874–883. doi:10.1002/prot.24246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecota DC, & Wood TK (1996). Exclusion of T4 phage by the hok/sok killer locus from plasmid R1. J Bacteriol, 178(7), 2044–2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K, Zavialov AV, Pavlov MY, Elf J, Gerdes K, & Ehrenberg M (2003). The bacterial toxin RelE displays codon-specific cleavage of mRNAs in the ribosomal A site. Cell, 112(1), 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu Y, Zhao Z, Li Y, Zou J, Ma Q, Zhao Y, . . . Bai F (2016). Enhanced Efflux Activity Facilitates Drug Tolerance in Dormant Bacterial Cells. Mol Cell, 62(2), 284–294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radzikowski JL, Vedelaar S, Siegel D, Ortega AD, Schmidt A, & Heinemann M (2016). Bacterial persistence is an active sigmaS stress response to metabolic flux limitation. Mol Syst Biol, 12(9), 882. doi:10.15252/msb.20166998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage HR, Connolly LE, & Cox JS (2009). Comprehensive Functional Analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Toxin-Antitoxin Systems: Implications for Pathogenesis, Stress Responses, and Evolution. PLOS Genetics, 5(12), e1000767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramisetty BCM, Ghosh D, Roy Chowdhury M, & Santhosh RS (2016). What Is the Link between Stringent Response, Endoribonuclease Encoding Type II Toxin–Antitoxin Systems and Persistence? Frontiers in Microbiology, 7(1882). doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao F, Short FL, Voss JE, Blower TR, Orme AL, Whittaker TE, . . . Salmond GP (2015). Co-evolution of quaternary organization and novel RNA tertiary interactions revealed in the crystal structure of a bacterial protein-RNA toxin-antitoxin system. Nucleic Acids Res, 43(19), 9529–9540. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AS, Bradley AR, Valasatava Y, Duarte JM, Prli A, #263, & Rose PW (2016). Web-based molecular graphics for large complexes. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Web3D Technology, Anaheim, California. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AS, & Hildebrand PW (2015). NGL Viewer: a web application for molecular visualization. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(W1), W576–W579. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenbacher FP, Suzuki M, Hurley JM, Montville TJ, Kirn TJ, Ouyang M, & Woychik NA (2012). Clostridium difficile MazF toxin exhibits selective, not global, mRNA cleavage. J Bacteriol, 194(13), 3464–3474. doi:10.1128/jb.00217-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rycroft JA, Gollan B, Grabe GJ, Hall A, Cheverton AM, Larrouy-Maumus G, . . . Helaine S (2018). Activity of acetyltransferase toxins involved in Salmonella persister formation during macrophage infection. Nat Commun, 9(1), 1993. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04472-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samhita L, Virumäe K, Remme J, & Varshney U (2013). Initiation with Elongator tRNAs. J Bacteriol, 195(18), 4202–4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson JE, Belanger M, & Moineau S (2013). Effect of the abortive infection mechanism and type III toxin/antitoxin system AbiQ on the lytic cycle of Lactococcus lactis phages. J Bacteriol, 195(17), 3947–3956. doi:10.1128/jb.00296-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauert M, Wolfinger MT, Vesper O, Muller C, Byrgazov K, & Moll I (2016). The MazF-regulon: a toolbox for the post-transcriptional stress response in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res, 44(14), 6660–6675. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano JM, Cruz JW, Vvedenskaya IO, Edifor R, Ouyang M, Husson RN, . . . Woychik NA (2016). tRNA is a new target for cleavage by a MazF toxin. Nucleic Acids Res, 44(3), 1256–1270. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano JM, Edifor R, Sharp JD, Ouyang M, Konkimalla A, Husson RN, & Woychik NA (2013). Mycobacterial toxin MazF-mt6 inhibits translation through cleavage of 23S rRNA at the ribosomal A site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110(21), 8501–8506. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222031110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano JM, Vvedenskaya IO, Knoblauch JG, Ouyang M, Nickels BE, & Woychik NA (2014). An RNA-seq method for defining endoribonuclease cleavage specificity identifies dual rRNA substrates for toxin MazF-mt3. Nat Commun, 5, 3538. doi:10.1038/ncomms4538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C, Leung E, Brown J, & Tollervey D (2009). The N-terminal PIN domain of the exosome subunit Rrp44 harbors endonuclease activity and tethers Rrp44 to the yeast core exosome. Nucleic Acids Research, 37(4), 1127–1140. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher MA, Balani P, Min J, Chinnam NB, Hansen S, Vulic M, . . . Brennan RG (2015). HipBA-promoter structures reveal the basis of heritable multidrug tolerance. Nature, 524(7563), 59–64. doi:10.1038/nature14662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher Maria A., Min J, Link Todd M., Guan Z, Xu W, Ahn Y-H, . . . Brennan Richard G. (2012). Role of Unusual P Loop Ejection and Autophosphorylation in HipA-Mediated Persistence and Multidrug Tolerance. Cell Reports, 2(3), 518–525. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher MA, Piro KM, Xu W, Hansen S, Lewis K, & Brennan RG (2009). Molecular mechanisms of HipA-mediated multidrug tolerance and its neutralization by HipB. Science, 323(5912), 396–401. doi:10.1126/science.1163806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan Y, Brown Gandt A, Rowe SE, Deisinger JP, Conlon BP, & Lewis K (2017). ATP-Dependent Persister Formation in Escherichia coli. MBio, 8(1). doi:10.1128/mBio.02267-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short FL, Akusobi C, Broadhurst WR, & Salmond GPC (2018). The bacterial Type III toxin-antitoxin system, ToxIN, is a dynamic protein-RNA complex with stability-dependent antiviral abortive infection activity. Sci Rep, 8(1), 1013. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-18696-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short FL, Pei XY, Blower TR, Ong SL, Fineran PC, Luisi BF, & Salmond GP (2013). Selectivity and self-assembly in the control of a bacterial toxin by an antitoxic noncoding RNA pseudoknot. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110(3), E241–249. doi:10.1073/pnas.1216039110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Herzog E, McDonald EM, Crooks AL, & Detweiler CS (2015). Physiologic Stresses Reveal a Salmonella Persister State and TA Family Toxins Modulate Tolerance to These Stresses. PLoS One, 10(12), e0141343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart PS, Franklin MJ, Williamson KS, Folsom JP, Boegli L, & James GA (2015). Contribution of stress responses to antibiotic tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 59(7), 3838–3847. doi:10.1128/aac.00433-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temmel H, Müller C, Sauert M, Vesper O, Reiss A, Popow J, . . . Moll I (2017). The RNA ligase RtcB reverses MazF-induced ribosome heterogeneity in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Research, 45(8), 4708–4721. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesper O, Amitai S, Belitsky M, Byrgazov K, Kaberdina AC, Engelberg-Kulka H, & Moll I (2011). Selective translation of leaderless mRNAs by specialized ribosomes generated by MazF in Escherichia coli. Cell, 147(1), 147–157. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Völzing KG, & Brynildsen MP (2015). Stationary-Phase Persisters to Ofloxacin Sustain DNA Damage and Require Repair Systems Only during Recovery. MBio, 6(5), e00731–00715. doi:10.1128/mBio.00731-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walling LR, & Butler JS (2018). Homologous VapC Toxins Inhibit Translation and Cell Growth by Sequence-Specific Cleavage of tRNA(fMet). J Bacteriol, 200(3). doi:10.1128/jb.00582-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Kim Y, Hong SH, Ma Q, Brown BL, Pu M, . . . Wood TK (2011). Antitoxin MqsA helps mediate the bacterial general stress response. Nat Chem Biol, 7(6), 359–366. doi:10.1038/nchembio.560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lord DM, Cheng HY, Osbourne DO, Hong SH, Sanchez-Torres V, . . . Wood TK (2012). A new type V toxin-antitoxin system where mRNA for toxin GhoT is cleaved by antitoxin GhoS. Nat Chem Biol, 8(10), 855–861. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver KE, & Tritle DJ (1994). Identification and characterization of an Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAD1-encoded stability determinant which produces two small RNA molecules necessary for its function. Plasmid, 32(2), 168–181. doi:10.1006/plas.1994.1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Wang P, Sun C, Guo Y, & Wang X (2017). Interaction of Type IV Toxin/Antitoxin Systems in Cryptic Prophages of Escherichia coli K-12. Toxins (Basel), 9(3). doi:10.3390/toxins9030077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther K, Tree JJ, Tollervey D, & Gerdes K (2016). VapCs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cleave RNAs essential for translation. Nucleic Acids Res, 44(20), 9860–9871. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther KS, Brodersen DE, Brown AK, & Gerdes K (2013). VapC20 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cleaves the sarcin-ricin loop of 23S rRNA. Nat Commun, 4, 2796. doi:10.1038/ncomms3796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther KS, & Gerdes K (2011). Enteric virulence associated protein VapC inhibits translation by cleavage of initiator tRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108(18), 7403–7407. doi:10.1073/pnas.1019587108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]