Abstract

Objectives

In Madagascar, plague (Yersinia pestis infection) is endemic in the central highlands, maintained by the couple Rattus rattus/flea. The rat is assumed to die shortly after infection inducing migration of the fleas. However we previously reported that black rats from endemic areas can survive the infection whereas those from non-endemic areas remained susceptible. We investigate the hypothesis that lineages of rats can acquire resistance to plague and that previous contacts with the bacteria will affect their survival, allowing maintenance of infected fleas. For this purpose, laboratory-born rats were obtained from wild black rats originating either from plague-endemic or plague-free zones, and were challenged with Y. pestis. Survival rate and antibody immune responses were analyzed.

Results

Inoculation of low doses of Y. pestis greatly increase survival of rats to subsequent challenge with a lethal dose. During challenge, cytokine profiles support activation of specific immune response associated with the bacteria control. In addition, F1 rats from endemic areas exhibited higher survival rates than those from non-endemic ones, suggesting a selection of a resistant lineage. In Madagascar, these results support the role of black rat as long term reservoir of infected fleas supporting maintenance of plague transmission.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13104-018-3984-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Plague, Rattus rattus, F1 antigen, Madagascar, Outbreak

Introduction

Plague, a flea-borne zoonosis, is caused by Yersinia pestis and is mainly associated with rodents [1]. Host resistance to plague is influenced by many factors including rodent species, genetic factors, and prior immunity. Few studies have demonstrated differences in plague resistance in wild rodents originated or not from separate field populations as reported in Western United States [2–4], in South Africa [5] and in Madagascar [6, 7]. Madagascar is the country worst affected by plague in the world with an average of 500 human cases annually especially in the central highlands [8, 9]. The black rat, Rattus rattus, is its main reservoir in rural areas. As reported in Antananarivo for both R. rattus and Rattus norvegicus, a higher resistance to the disease is observed in rats from endemic areas compared to those from plague-free zones [6, 7]. Genetic background, like CCR5 gene and Class I Major Histocompatibility Complex polymorphisms, seems important for this resistance l [10, 11].

Survival of Y. pestis within its host depends on evasion of the host’s innate immune system [12], and on circumventing phagocytosis and antimicrobial effectors [13]. In a mouse model, humoral and cellular immunity seem to be able to control the pathogen despite a down regulation of the major pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α [14, 15]. Anti-F1 antibodies are also associated with protection against plague in vaccinated mice [16, 17]. In wild populations, co-infection with other pathogens could also play a major role in resistance to plague as during latent murine herpes virus infection. This cross protection is due to a secretion of IFN-γ along with macrophage activation in response to viral infection [18]. In addition, lipopolysaccharide produced by other pathogens during co- or previous infections may suppress Y. pestis virulence mechanisms by providing early recognition and initiation of immune signalling [19].

To address the questions regarding resistance in black rats, first generation (F1) of rats were obtained from wild black rats from plague-endemic and plague-free areas, and bred in the laboratory. The goals of this study were (i) to find out if pre-inoculation of Y. pestis can be protective following a second challenge, and (ii) to determine if genetic background influences resistance of rats to Y. pestis.

Main text

Methods

Establishment of F1 rat populations

F1 generations (born and bred in a laboratory) were obtained from wild R. rattus parents collected in the field, either from a plague endemic area (EA, Betafo) or from plague non-endemic areas (NEA, Miandrivazo and Toamasina) (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Wild rats were kept for 2 weeks for observation and only seronegative individuals for Y. pestis anti-F1 IgG were selected.

Plague challenge experiments

A Y. pestis 40/09B strain isolated from bubo was used throughout this study. The bacterial concentration was estimated (i) before inoculation by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm after 48 h of culture, and (ii) after injection by seeding serial dilutions of the solution on selective Cefsulodin Irgasan Novobiocin agar plates. Inoculated doses were chosen in accordance to previous results [6, 7]. Bacterial suspension (100 µl) was injected subcutaneously in the thigh. Rats were housed in a ventilated cabinet with food and water ad libitum, and were examined four times daily.

The effect of inoculation of a low dose of Y. pestis on response to a second lethal dose was investigated using 45 F1 rats from the EA divided into three groups (n = 15 each). Two groups were inoculated with 15 and 150 colony forming units (cfu) of Y. pestis respectively, whereas the control group was injected with Brain Heart Infusion (BHI). On day 29 after the first inoculation, all animals received a lethal dose of 15,000 cfu of the same strain.

Comparison of the difference in survival between F1 rats from EA and NEA parents was performed twice with two different NEAs: (i) with F1 rats originating from Miandrivazo (NEA) and Betafo (EA) (15 rats each), and (ii) a second time with F1 rats obtained from Toamasina (NEA) and Betafo (EA) (16 rats each).

To confirm that death was caused by plague, a F1 antigen diagnostic test [20] was used on spleen tissue of dead rats.

Detection of anti-F1 antibodies

For each experiment, plasma samples (diluted 1/100) were assayed in duplicate by ELISA for the presence of anti-F1 IgM [21] and anti-F1 IgG [22]. Results were expressed as the ratio of OD of the sample to the OD of negative sera +3 SD. Plasma samples with an OD ratio ≥ 2 were considered as positive [21].

Cytokine measurement

Cytokines were measured in plasma of F1 rats collected at day 5 after inoculation of 150 cfu of Y pestis, using a Novex Rat Cytokine Magnetic 10-Plex Panel run on a Magpix Luminex.

Statistical analyses

Survival curves were compared by Log Rank test and at end point by Mann–Whitney test. Comparisons of percentages and means were performed using Yates’ Chi squared test and Kruskal–Wallis test respectively. Groups were compared by Mann–Whitney or Wilcoxon paired or independent test depending on the variables.

Results

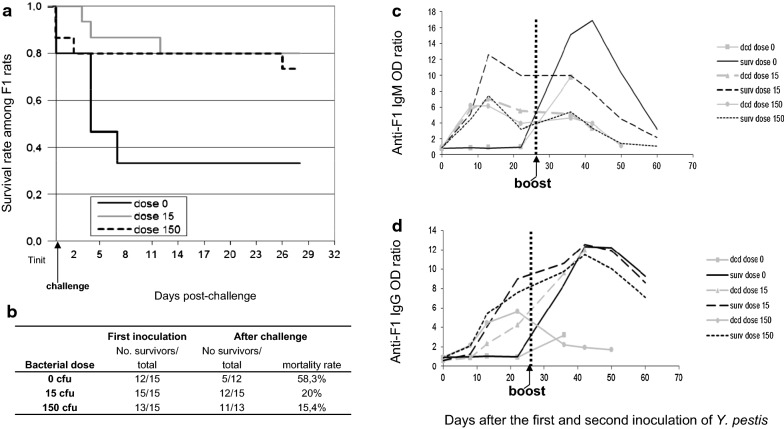

Effect of pre-inoculation of F1 rats with Y. pestis after a lethal challenge

After the first inoculation of Y. pestis, mortality was stable whatever the dose (3 rats for control group, 0 rats for 15 cfu, 2 rats for 150 cfu). After challenge with 15,000 cfu (Fig. 1a), mortality rates decreased with previous inoculation (58.3%, 20% and 15.4% mortality for 0, 15 and 150 cfu respectively, Fig. 1b). For those that died, survival time after challenge increased depending on the dose pre-injected (4.8 ± 1.4, 7.3 ± 4.9 and 15 ± 17 days for 0, 15 and 150 cfu respectively) with significantly different survival curves (P < 0.0364; Log Rank test). More females died compared to males after the second inoculation (17.5% vs. 12.5%), but the difference was not significant.

Fig. 1.

Effect of pre-inoculation of Y. pestis on survival of rats after challenge with a lethal dose of bacteria. Three groups of F1 rats originating from plague-endemic area were first inoculated with 0, 15 or 150 cfu of Y. pestis (strain 40/09B) and followed over 29 days (Tinit = time of initial inoculations). Survivors were then challenged with 15,000 cfu of the same strain and followed over 29 days. Blood samples were collected on day 0, 8, 13 and 21 after both the first and lethal inoculations of Y. pestis. Male/Female repartition was: 0 cfu (7/8); 15 cfu (8/7); 150 cfu (10/5). a Survival data is represented following Kaplan–Meier representation; b Data related to the curve; c Kinetics of anti-F1 IgM and d Kinetics of anti-F1 IgG antibodies from the three groups of F1 rats first inoculated with 0, 15 or 150 cfu of Y. pestis and challenged with 15,000 cfu are presented separately for rats surviving to the challenge (surv) and those that deceased (dcd)

After the first inoculation (15 and 150 cfu) anti-F1 IgM increase between day 0 and day 8, peaked at day 13 and decreased progressively until day 22 (final mean ratio of 6.5) (Fig. 1c). Regardless of the dose injected, anti-F1 IgG appeared between day 8 and day 13 and increased up to day 22. Some surviving rats were found without anti-F1 IgG after this first inoculation (Fig. 1d).

Following the challenge, in the control group (surviving rats) a high level of anti-F1 IgM was induced (maximum at day 13 and rapid decrease before day 31 post-challenge, Fig. 1c), whereas for rats pre-inoculated with 15 cfu, IgM remained constant and declined to day 31 post-challenge. For rats previously inoculated with 150 cfu only a transitory increase in anti-F1 IgM was observed at day 7 post-challenge, rapidly declining to undetectable levels. Accordingly, anti-F1 IgG increase was faster for control group (significant increase at all days after challenge compared to day 22 after pre inoculation) than for rats pre-sensitized with 15 and 150 cfu (increase only significant at day 13 and day 31 respectively, Additional file 2: Table S1). However, more importantly for all surviving rats including controls, the same IgG pattern was observed with a maximum at day 13 (mean ratio of 12), and a slow decay until day 31 (mean ratio of 8) (Fig. 1d). These variations were significant for both IgM and IgG compared to antibodies at day 0 (P < 0.002 for all). In the same line, for surviving rats, a highly significant increase of anti-F1 IgM and IgG at day 21 after first challenge was observed compared to those that died (i.e. P < 0.0016, P < 0.0029 Mann–Whitney test).

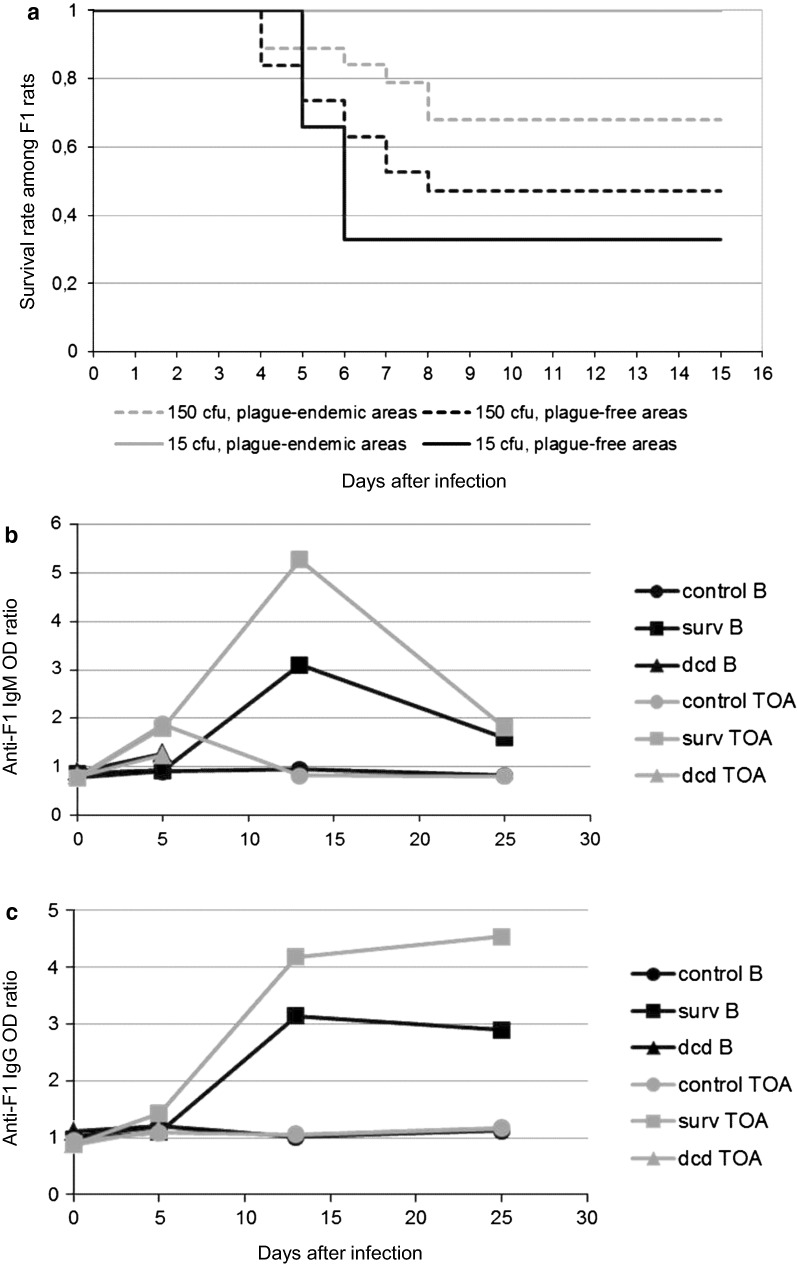

Differential response of F1 rats from endemic and non-endemic areas after a single Y. pestis inoculation

After single inoculation of 15 cfu, mortality was low but with a significant difference between EA and NEA (0/6 versus 4/6, P unilateral = 0.03). After inoculation with 150 cfu, survival rate at day 15 was higher for rats from the EA compared to others (68.4% vs. 47.3%; P = 0.1; Chi squared test, Fig. 2a). Most deaths occurred between day 4 and day 8 post-infection, without significant difference in the mean time to death for NEA and EA rats (5.6 ± 1.4 and 6.1 ± 1.8 days respectively).

Fig. 2.

Effect of origin of rats on the survival rate following inoculation of Y. pestis. In the first experiment, F1 rats from plague-endemic area (Betafo) or from plague-free areas (Miandrivazo) (15 rats each) were inoculated once with 15 cfu (6 rats) or 150 cfu of Y. pestis (6 rats) or with BHI as a control (3 rats). In the second experiment, F1 rats from Toamasina (NEA) and Betafo (16 rats each) were inoculated once with 150 cfu of Y. pestis (13 rats) or with BHI as control (3 rats). Animals were blood sampled post-inoculation at day 0, 5, and 18 (Miandrivazo vs. Betafo) and 0, 5, 13 and 25 (Toamasina vs. Betafo). a The Kaplan–Meier survival curves are represented for each lineage: plague-endemic area (grey) and plague-free areas (black). b Kinetics of IgM and c Kinetics of anti-F1 IgG antibodies after inoculation are presented separately for surviving (surv) and deceased rats (dcd)

Whatever the lineage, after single inoculation with 150 cfu, anti-F1 IgM appeared between day 5 to day 13, increased up to day 13 and then rapidly declined to a low level (Fig. 2b) without significant difference between rats (P = 0.38; Fisher’s exact test at day 13).

For anti-F1 IgG, a plateau was reached after day 13 (Fig. 2c), without significant difference between lineages at day 25. In the same line, for rats which died before day 8, no difference was found for anti-F1 IgM and IgG between lineages.

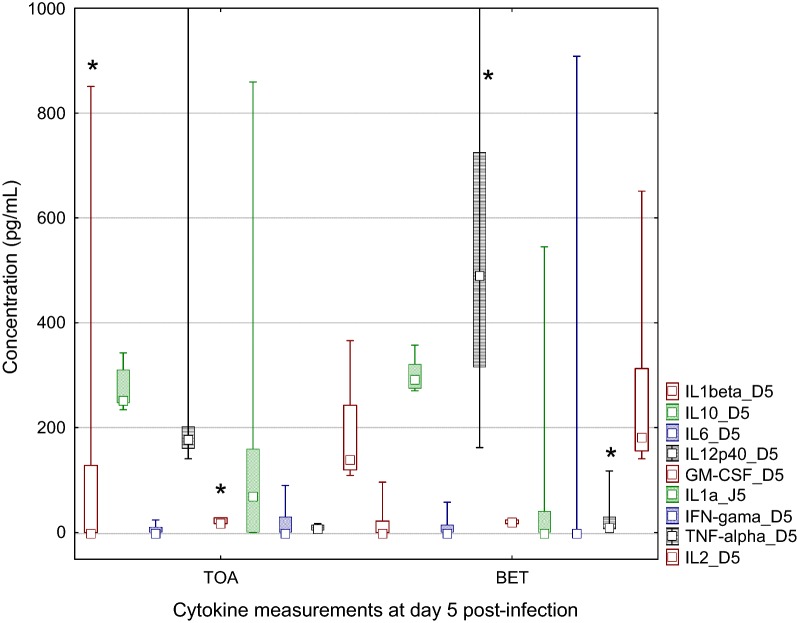

Cytokine measurement

Cytokine measurement was obtained for eight and nine plasma samples from Toamasina (NEA) and Betafo (EA) respectively (Fig. 3). At day 0 for EA lineage, cytokine concentrations were significantly higher for IL-10, IL-6 and IL-2 (P < 0.07, P < 0.04 and P < 0.003 respectively), which was surprising for F1 rats housed in the same conditions. At day 5, plasma levels of IFN-γ, IL-12 were also significantly higher in rats from Betafo (EA) (P < 0.0001, P < 0.036 respectively), whereas IL-1β was higher in rats from Toamasina (NEA) lineage (P < 0.0001). GM-CSF significantly decreases from day 0 to day 5 in the NEA group compared to EA ones.

Fig. 3.

Cytokine measurements in plasma of rats after inoculation of Y. pestis. Cytokines measurement using a Novex Rat Cytokine Magnetic 10-Plex Panel for simultaneous quantitative determination of GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 (p40/p70) and TNF-α. Cytokine concentrations (in pg/mL) measured in plasma at day 5 post-inoculation with 150 cfu of Y. pestis are presented (F1 rats as in Fig. 2). Lineage Betafo and lineage Toamasina are presented separately (Plot: median/box 25–75%/min–max, *significant difference)

Discussion

Previous studies demonstrated that rats from plague endemic area were more resistant to plague than others [6, 7] prolonging at the same time fleas survival [23]. However these local differences in resistance, could be due to co-infections by other pathogens [21]. To overcome this issue, F1-generation of rats were obtained in the laboratory from wild rats trapped in endemic and non-endemic areas.

Following inoculation of a first low dose of bacteria most of these F1 rats produced antibodies whatever the lineage. After the second lethal inoculation of Y. pestis both the survival rates and the time to death increased with the priming dose. It confirmed that previous contact with as few as 15 cfu of Y. pestis can greatly improve the survival of rats. After challenge, anti-F1 IgG antibodies increase in surviving non-inoculated rats at the same level as in pre-inoculated ones, which supports a role of IgG in the protection against Y. pestis. However, as previously reported with rock and ground squirrels [2] and wild rats [6, 7, 21, 24], part of them survived without any antibody production.

This study also reports a resistance of F1 rats from plague-endemic lineage compared to those from plague-free zones. This genetic hypothesis was previously evocated for rats from Antananarivo [6], in California voles [4] and in F1 progeny of grasshopper mice [3]. In grasshopper mice [4], anti-F1 titers were not linked to the origin of rats and not clearly associated with resistance. Conversely, higher concentration of IFN-γ, IL-12 and TNF-α were found in F1 rats lineage from endemic area in agreement with previous studies in susceptible mice, where down regulation of IFN-γ and TNF-α has been reported [14, 25]. Following infection of macrophages, an increase of IL-1 was also related to activation of neutrophil polynuclear cells and replication of Y. pestis within cells [26]. The role of TNF/TNFR1 in apoptosis related resistance to Y. pestis was as well recently highlighted [27]. The limited infection in resistant rats could be thus related to a lower inhibition of the innate and adaptive immune responses [28, 29], especially with a changes in phagocytic activity [4]. As for prairie dogs surviving to plague blood coagulation and inflammation may also explain this difference [30].

Overall these results confirm the potential resistance of R. rattus against plague and support a role of antibodies in this resistance.

Conclusions

This study highlights two mechanisms that may support maintenance of plague in Madagascar, (i) a better heritable resistance of lineages from EA against plague and (ii) an acquired resistance against a lethal dose of Y. pestis initiated by pre-inoculation of a very low amount of bacteria, likely conferred by anti-F1 IgG. This suggests that rats could sustain infected flea populations and therefore making them important reservoirs of the disease [31].

Limitations

This study was limited by a restricted number of F1 black rats obtained from wild rat lineage. More investigation are needed on a larger batch of F1 rats to address the role of genetic background in the resistance of rats from plague endemic areas.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Location of field collection of F1 rats’ parents. Betafo represents the plague-endemic area, whereas Toamasina and Miandrivazo are considered as plague-free areas. Dashed line: limits of the main plague-endemic area in the central highlands of Madagascar.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Wilcoxon paired test analysis of anti-F1 IgM and IgG variations during challenge experiment. *(pc) post challenge.

Authors’ contributions

VA performed the experiments and drafted the manuscript; MR organized field work and analyzed data; RJ supervised the study, analyzed the data and worked on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Michel Ranjalahy for supervising animal experiments and to the staff of the Immunology Unit for technical assistance.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study has been conducted in accordance with the directive 2010/63/EU (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/Lex-UriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2010:276:0033:0079:EN:PDF) and was approved by a local “Ad-Hoc” committee including the University, the Veterinarian School of Antananarivo and the Ministry of livestock of the Malagasy Government (“Pasteur Institut Pasteur of Madagascar institutional committee for animal ethic”).

Funding

This work was funded by an internal grant from the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- EA

endemic area

- NEA

non-endemic areas

- OD

optical density

- Cfu

colony forming units

- BHI

Brain Heart Infusion

- IgG

immunoglobin G

- IgM

immunoglobin M

Contributor Information

Voahangy Andrianaivoarimanana, Email: kekely@pasteur.mg.

Minoarisoa Rajerison, Email: mino@pasteur.mg.

Ronan Jambou, Email: rjambou@pasteur.fr.

References

- 1.Gage KL, Kosoy MY. Natural history of plague: perspectives from more than a century of research. Annu Rev Entomol. 2005;50:505–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quan TJ, Barnes AM, Carter LG, Tsuchiya KR. Experimental plague in rock squirrels, Spermophilus variegatus (Erxleben) J Wildl Dis. 1985;21:205–210. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-21.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas RE, Barnes AM, Quan TJ, Beard ML, Carter LG, Hopla CE. Susceptibility to Yersinia pestis in the northern grasshopper mouse (Onychomys leucogaster) J Wildl Dis. 1988;24:327–333. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-24.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubbert WT, Goldenberg MI. Natural resistance to plague: genetic basis in the vole (Microtus californicus) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970;19:1015–1019. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shepherd AJ, Leman PA, Hummitzsch DE. Experimental plague infection in South African wild rodents. J Hyg (Lond). 1986;96:171–183. doi: 10.1017/S0022172400065943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahalison L, Ranjalahy M, Duplantier JM, Duchemin JB, Ravelosaona J, Ratsifasoamanana L, et al. Susceptibility to plague of the rodents in Antananarivo, Madagascar. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;529:439–442. doi: 10.1007/0-306-48416-1_87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tollenaere C, Rahalison L, Ranjalahy M, Duplantier JM, Rahelinirina S, Telfer S, et al. Susceptibility to Yersinia pestis experimental infection in wild Rattus rattus, reservoir of plague in Madagascar. Eco Health. 2010;7:242–247. doi: 10.1007/s10393-010-0312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brygoo ER. Epidémiologie de la peste à Madagascar. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 1966;35:9–147. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization Plague around the world, 2010–2015. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2016;91:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tollenaere C, Rahalison L, Ranjalahy M, Rahelinirina S, Duplantier JM, Brouat C. CCR5 polymorphism and plague resistance in natural populations of the black rat in Madagascar. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:891–897. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tollenaere C, Ivanova S, Duplantier JM, Loiseau A, Rahalison L, Rahelinirina S, et al. Contrasted patterns of selection on MHC-linked microsatellites in natural populations of the Malagasy plague reservoir. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li B, Yang R. Interaction between Yersinia pestis and the host immune system. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1804–1811. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01517-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sebbane F, Lemaître N, Sturdevant DE, Rebeil R, Virtaneva K, Porcella SF, et al. Adaptive response of Yersinia pestis to extracellular effectors of innate immunity during bubonic plague. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11766–11771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601182103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakajima R, Brubaker RR. Association between virulence of Yersinia pestis and suppression of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect Immun. 1993;61:23–31. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.23-31.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sebbane F, Gardner D, Long D, Gowen BB, Hinnebusch BJ. Kinetics of disease progression and host response in a rat model of bubonic plague. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1427–1439. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62360-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson GW, Jr, Worsham PL, Bolt CR, Andrews GP, Welkos SL, Friedlander AM, et al. Protection of mice from fatal bubonic and pneumonic plague by passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies against the F1 protein of Yersinia pestis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:471–473. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, D’Souza AJ, Alarcon JB, Mikszta JA, Ford BM, Ferriter MS, et al. Protective immunity in mice achieved with dry powder formulation and alternative delivery of plague F1-V vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:719–725. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00447-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton ES, White DW, Cathelyn JS, Brett-McClellan KA, Engle M, Diamond MS, et al. Herpesvirus latency confers symbiotic protection from bacterial infection. Nature. 2007;447:326–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montminy SW, Khan N, McGrath S, Walkowicz MJ, Sharp F, Conlon JE, et al. Virulence factors of Yersinia pestis are overcome by a strong lipopolysaccharide response. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1066–1073. doi: 10.1038/ni1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chanteau S, Rahalison L, Ralafiarisoa L, Foulon J, Ratsitorahina M, Ratsifasoamanana L, et al. Development and testing of a rapid diagnostic test for bubonic and pneumonic plague. Lancet. 2003;361:211–216. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrianaivoarimanana V, Telfer S, Rajerison M, Ranjalahy MA, Andriamiarimanana F, Rahaingosoamamitiana C, et al. Immune responses to plague infection in wild Rattus rattus, in Madagascar: a role in foci persistence? PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dromigny JA, Ralafiarisoa L, Raharimanana C, Randriananja N, Chanteau S. La sérologie anti-F1 chez la souris OF1, test complémentaire pour le diagnostic de la peste humaine. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 1998;64:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham CB, Woods ME, Vetter SM, Petersen JM, Montenieri JA, Holmes JL, et al. Evaluation of the effect of host immune status on short-term Yersinia pestis infection in fleas with implications for the enzootic host model for maintenance of Y. pestis during interepizootic periods. J Med Entomol. 2014;51:1079–1086. doi: 10.1603/ME14080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen TH, Meyer KF. Susceptibility and antibody response of Rattus species to experimental plague. J Infect Dis. 1974;129(Suppl):S62–S71. doi: 10.1093/infdis/129.Supplement_1.S62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakajima R, Motin VL, Brubaker RR. Suppression of cytokines in mice by protein A–V antigen fusion peptide and restoration of synthesis by active immunization. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3021–3029. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3021-3029.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spinner JL, Winfree S, Starr T, Shannon JG, Nair V, Steele-Mortimer O, et al. Yersinia pestis survival and replication within human neutrophil phagosomes and uptake of infected neutrophils by macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:389–398. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1112551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson LW, Philip NH, Dillon CP, Bertin J, Gough PJ, Green DR, et al. Cell-extrinsic TNF collaborates with TRIF signaling to promote yersinia-induced apoptosis. J Immunol. 2016;197:4110–4117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H, Wang T, Tian G, Zhang Q, Wu X, Xin Y, et al. Host transcriptomic responses to pneumonic plague reveal that Yersinia pestis inhibits both the initial adaptive and innate immune responses in mice. Int J Med Microbiol. 2017;307:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philip NH, DeLaney A, Peterson LW, Santos-Marrero M, Grier JT, Sun Y, et al. Activity of uncleaved caspase-8 controls anti-bacterial immune defense and TLR-induced cytokine production independent of cell death. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005910. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Busch JD, Van Andel R, Cordova J, Colman RE, Keim P, Rocke TE, et al. Population differences in host immune factors may influence survival of Gunnison’s prairie dogs (Cynomys gunnisoni) during plague outbreaks. J Wildl Dis. 2011;47:968–973. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-47.4.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisen RJ, Gage KL. Adaptive strategies of Yersinia pestis to persist during inter-epizootic and epizootic periods. Vet Res. 2009;40:1. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2008039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Location of field collection of F1 rats’ parents. Betafo represents the plague-endemic area, whereas Toamasina and Miandrivazo are considered as plague-free areas. Dashed line: limits of the main plague-endemic area in the central highlands of Madagascar.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Wilcoxon paired test analysis of anti-F1 IgM and IgG variations during challenge experiment. *(pc) post challenge.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.