Abstract

Background:

Accumulating evidence indicates that the failure to recover from the effects of proactive semantic interference [frPSI] represents an early cognitive manifestation of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. A limitation of this novel paradigm has been a singular focus on the number of targets correctly recalled, without examining co-occurring semantic intrusions [SI] that may highlight specific breakdowns in memory.

Objectives:

We focused on SI and their relationship to amyloid load and regional cortical thickness among persons with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI).

Methods:

Thirty-three elders diagnosed with aMCI underwent F-18 florbetaben amyloid PET scanning with MRI scans of the brain. We measured the correlation of SI elicited on cued recall trials of the Loewenstein-Acevedo Scales for Semantic Interference and Learning [LASSI-L] with mean cortical amyloid load and regional cortical thickness in AD prone regions.

Results:

SI on measures sensitive to frPSI was related to greater total amyloid load and lower overall cortical thickness [CTh]. In particular, SI were highly associated with reduced CTh in the left entorhinal cortex [r=−.71; p<.001] and left medial orbital frontal lobe [r=−.64; p<.001]; together accounting for 66% of the explained variability in regression models.

Conclusion.

Semantic intrusions on measures susceptible to frPSI related to greater brain amyloid load and lower cortical thickness. These findings further support the hypothesis that frPSI, as expressed by the percentage of intrusions, may be a cognitive marker of initial neurodegeneration and may serve as an early and distinguishing test for preclinical AD that may be used in primary care or clinical trial settings.

Keywords: Semantic intrusions, Alzheimer’s, MCI, amyloid imaging, preclinical, mild cognitive impairment

1. INTRODUCTION

As the population ages, it becomes imperative to find disease-modifying treatments for [AD] [1]. Such targeted interventions likely will be most effective in the initial stages of the disease, before significant multi-system degeneration has occurred [2, 3]. This has highlighted the need for cognitive assessment instruments that are sensitive to the earliest stages of AD [3, 4].

A major limitation of most existing memory measurement paradigms, such as list-learning tests, is that learning is relatively passive as these assessments do not employ controlled learning paradigms during initial acquisition [such as category cues]. Such controlled learning minimizes individual differences in initial learning strategies and the effects of cognitive reserve [5, 6]. Further, specific deficits in episodic and source memory for competing targets that are semantically related are typical features of AD [4]. While some traditional list-learning measures tap proactive interference effects, most do not emphasize proactive semantic interference [PSI; which is when old semantic learning interferes with the acquisition of new semantic learning] and more importantly, none investigates recovery from PSI [4].

A growing body of evidence indicates that failure to recover from proactive semantic interference [frPSI] on competing word lists of the LASSI-L [7] may be an early marker of AD in adults diagnosed with amnestic mild cognitive impairment [aMCI] and may also relate to volume reductions in selectively vulnerable brain regions [8–10]. Even among cognitively normal community-dwelling elders, frPSI has been related to increased amyloid load in the precuneus, posterior cingulate and other AD prone regions [11].

Prior research focused on the accuracy of cued recall from two competing lists of semantically related targets in order to assess proactive semantic interference [PSI] or failure to recover from semantic interference [frPSI] [9]; however, semantic intrusions on measures sensitive to PSI and frPSI have not been previously investigated, even though intrusion errors in memory tasks have been found to be an important feature in AD [12] and may occur in persons who exhibit normal performance on cued recall tasks. Such errors are thought to reflect deficits in source monitoring or in filtering previously encoded information [13] and in the strategic retrieval of such information [14].

In this study, we assessed the occurrence of semantic intrusions, as a percentage of total responses on trials related to PSI and frPSI. We reasoned that expressing intrusion errors as a function of total responses on cued recall trials would highlight deficits in semantic interference that relate to the pathology of AD, including amyloid load and cortical thickness in AD-prone regions [15] in older adults diagnosed with aMCI. The specificity of such a finding might be used to aid in the determination of MCI-AD from MCI of other etiologies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We recruited 33 participants diagnosed with aMCI [56% female] in the 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center cohort for this IRB approved study. Mean age of the participants was 71.9 years [SD=6.9; range 59–85]; the average educational attainment was 15.4 years [SD=3.3; range 6–22]. The mean MMSE score was 26.9 [SD=1.8; Range=23–39]. Participants were tested in their native language, which was 47% Spanish and 53% English.

All participants were administered a common clinical assessment, the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale [CDR; 16], and the Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE; 17]. Memory and other cognitive complaints were assessed by an experienced geriatric psychiatrist [MG] who was blind to the neuropsychological test results and had formal training in administering the CDR. The 33 participants were all community-dwelling older adults who were independent in their activities of daily living, had knowledgeable collateral informants, and did not meet DSM-5 criteria for Major Neurocognitive Disorder current major depressive episode [18] or any other neuropsychiatric disorder. Where there was evidence of cognitive decline by history and/or clinical examination, the clinician scored the Global CDR as 0.5 and considered a diagnosis of MCI based on their examination, pending the results of formal neuropsychological testing. Subsequently, we administered a standard neuropsychological battery independent of the clinical evaluation. This protocol included the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised [HVLT-R; 19], delayed recall from the Logical Memory subtest of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Dataset Neuropsychological Battery [20], Category Fluency [21], the Block Design subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales-Fourth Edition [22], and Parts A and B of the Trail Making Test [23].

2.1. Diagnostic Criteria for Amnestic MCI [aMCI] Participants [n=33]

Individuals were classified as aMCI if they evidenced: a] subjective memory complaints reported by the participant and/or collateral informant; b] evidence by clinical evaluation or history of memory decline; c] Global CDR score of 0.5; and d] one or more memory measures 1.5 SD below normal limits relative to age and education related norms as described in previous studies [4].

2.2. Loewenstein-Acevedo Scales for Semantic Interference and Learning [LASSI-L]

This novel cognitive stress test uses controlled learning and cued recall to maximize storage of an initial list of to-be-remembered targets that represent three semantic categories. The LASSI-L has been validated in Spanish [7, 8]. What is unique about the LASSI-L is the presentation of a different list of to-be-remembered words that shares the same semantic categories, which are fruits, musical instruments and articles of clothing. Shared semantic categories elicit a considerable amount of proactive semantic interference [4, 9]. Unlike other memory paradigms, the individual is administered this second list of words twice, to measure recovery from proactive semantic interference effects. Retroactive semantic interference and delayed recall are also assessed. The specific elements of the test are described below.

The participant is first instructed to read 15 individually presented target words aloud that are fruits, musical instruments and articles of clothing [five words per category]. In the unlikely event that the person cannot correctly read the word, the word is read by the examiner and the person is asked to repeat the word. If a person does not know one of the words [also unlikely], the examiner tells the person the category to which the word belongs [e.g., “Lime is a fruit.”], and the person is asked to repeat the word. After reading all 15 words, the person is asked to recall the words in any order. Following the free recall trial, the participant is presented with each category cue [e.g., clothing] and is asked to recall the words that belonged to that category [LASSI-L A1]. The participant is then presented with the target stimuli for a second learning trial with a subsequent cued recall to strengthen the acquisition and recall of the List A targets, providing maximum storage of the to-be-remembered information [LASSI-L A2]. Following this trial, the participant is presented with a semantically related list [i.e., List B], in the same manner as List A. List B consists of 15 words that are different from List A, but belong to each of the three categories used in List A [i.e., fruits, musical instruments, and articles of clothing]. Following the presentation of the List B words, the person is asked to freely recall the List B words; this assesses proactive interference effects [LASSI-L B1]. Then, each category cue is given, and the participant is asked to recall each of the List B words that belonged to each of the three categories. Importantly, List B words are presented once again, followed by a second category-cued recall trial, which allows the assessment of the ability to recover from the initial proactive semantic interference effects [LASSI-L B2]. Recovery from proactive semantic interference is a feature of the LASSI-L that is not assessed by any existing list-learning measure [4]. Test-retest reliabilities of the LASSI-L have been shown to be high in previous studies, and the accuracy of classification of aMCI patients versus cognitively normal elderly exceeded 90% [7, 24].

2.3. MRI Imaging

Participants diagnosed with aMCI underwent a brain MRI scan using a Siemens Skyra 3T MRI at Mount Sinai Medical Center. Brain parcellation was obtained using the 3D T1 sequence [MPRAGE] with isotropic resolution of 1.0 mm. After visual inspection to ensure that there were no segmentation issues, FreeSurfer 5.3 software [http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu] was employed to assess regional cortical thickness in AD and non-AD prone regions within the brain and applied to the MRI scans using the cen-tos4_x86_64 Linux system. The original MRI scan was first mapped to the standard MNI 305 space, yielding the image referred to as T1.mgz, which was used as the reference image following the registration procedure.

Based on the T1 image, the corresponding image file [termed as aparc+aseg.mgz] provided the FreeSurfer parcellated and segmented cortical regions. We assessed overall cortical thicknesses in both the left and right hemispheres. However, due to the high levels of association between homologous regions in both hemispheres and the fact that the LASSI-L is a verbal test, we examined cortical thickness in only the following left hemisphere regions: entorhinal cortex [ERC]; fusiform, parahippocampus, precuneus, posterior cingulate, rostral anterior cingulate, rostral middle frontal, superior frontal, lateral orbital frontal, medial orbital frontal, caudal middle frontal, inferior temporal, superior temporal, middle temporal, temporal pole, banks of the superior temporal sulcus, inferior parietal, superior parietal, supramarginal, cuneus, precentral, post central, insula, pericalcarine and lateral occipital regions. We corrected for false discovery rate employing procedures described below [25].

2.4. Amyloid Imaging

All participants were scanned on a Siemens Biograph 16 PET/CT scanner, operating in 3D mode [55 slices/frame, 3mm slice thickness 128 X128 matrix] for a duration of 20 minutes, beginning 90 minutes after injection of Neuraceq [[F-18] Florbetaben] 300 MBQ. Images were obtained from the top of the head to the top of the neck and CT data was employed for initial attenuation correction as well as reconstruction of images in the sagittal, axial and coronal planes. To quantify Aβ load from the PET/CT scan images the FMRIB Software Library [FSL; 26] was employed to co-register the PET/CT image to the aforementioned MRI T1 image. The Florbetaben PET/CT scan, including the outline of the skull, was co-registered linearly [i.e., trilinear interpolation] with 12 degrees of freedom, onto the T1 image from the MRI scan. This registration process ensured that the Florbetaben PET/CT image had the same accurate segmentation and parcellation as in the MRI. Thus, mean uptake in counts for each of the FreeSurfer-defined regions was calculated and a global Standard Uptake Value Ratio [SUVR] was calculated by averaging cortical uptake in the frontal, parietal, lateral temporal, occipital, and anterior and posterior cingulate regions, normalized to mean gray matter counts in the cerebellum. The typical mean SUVR cut-off for amyloid positivity for Florbetaban is 1.4 [27]. In our subject sample, mean SUVR ranged from .9159 to 1.5764, with 8 individuals at or above the threshold of 1.4. In the analyses in this investigation, we avoided use of absolute thresholds for amyloid positivity by the use of measures of association only (Table 1).

Table 1.

Thirty-three aMCI participants with florbetaben (18-F), cortical thickness measures and different LASSI-L cued recall and intrusion measures.

| LASSI-L A2 Recall (Maximum Recall of Original Targets) | LASSI-L Cued B1 Recall (Proactive Semantic Interference: PSI) | LASSI-L Cued B2 Recall (Failure to Recover from Proactive Semantic Interference: frPSI) | LASSI-L Cued B1 Semantic Intrusion (PSI) | LASSI-L Cued B1 Semantic Intrusion (PSI) as a Percentage of Total Cued B1 Responses | LASSI-L Cued B2 Semantic Intrusion (frPSI) | LASSI-L Cued B2 Semantic Intrusions (frPSI) as a Percentage of Total Cued B2 Responses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Amyloid Load | r=−.24 (p=.187) | r=−.02 p=.863 | r=−.22 p=.228 | r=.41 (p=.018) | r=−.32 (p=.073) | r=−.33 (p=.063) | r=.39 (p=.024) |

| Center Total Cortical Thickness | r=.22 (p=.237) | r=.10 (p=.582) | r=−.37 (p=.038) | r=−.25 p=.175 | r=−.27 p=.130 | r=.39 (p=.026) | r=−.50 (p=.003) |

| Right Total Cortical Thickness | r=.19 (p=.288) | r=.02 (p=.905) | r=−.39 (p=.029) | r=−.25 p=. 161 | r=−.26 p=.147 | r=−.36 (p=.045) | r=−.48 (p=.007) |

Note: There were 33 participants with Amyloid Scans and 32 Participants with Available MRI Scans.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

The ratio of intrusions on Cued B1 and Cued B2 trials to the number of correct responses on these trials expressed as a percentage [% intrusions] were examined by the formula [semantic intrusion/total responses [correct + semantic intrusions] on cued recall.

We examined the associations between amyloid load, cortical thickness measures and LASSI-L measures, including % intrusions, using a series of Pearson Product Moment correlation coefficients. Because of the large number of left hemisphere cortical thickness measures being related to percentage of Cued Recall B1 measures and Cued Recall B2 measures, the significance of p-values for correlation coefficients [Pearson Product Moment] between LASSI-L and CTh measures were adjusted using the correction for False Discovery Rate [FDR] [25]. Those regions of cortical thickness that survived FDR correction were then entered into step-wise regression equations to determine the combination of biological measures that were most predictive of the percentage of semantic intrusion errors for both Cued B1 and Cued B2 recall of the LASSI-L.

3. RESULTS

Of all measures, higher LASSI-B2 intrusion ratios were most strongly related to decreased total left hemisphere Cth [r=−.50; p=.003] and total right hemisphere Cth [r=−.48; p=.007] (Table 1). Higher total amyloid load was also related to higher LASSI-B2 intrusion rates [r=.39; p=.024] and higher absolute LASSI-B1 intrusion rates [r=.41; p=.018]. The B1 intrusion ratio was not statistically associated with amyloid load. Further, maximum performance on LASSI-L A2 Cued Recall and Cued B1 recall were not related to total amyloid load or cortical thickness in the right and left hemispheres, although Cued B2 Cued Recall and absolute number of Cued B2 intrusions were related to total cortical thickness in both left and right hemispheres. The correlation between total amyloid load and total left hemisphere cortical thickness in our aMCI participants was non-significant [r=−.01; p=.965 as was amyloid load with total left hemisphere cortical thickness [r=−.13; p=.489].

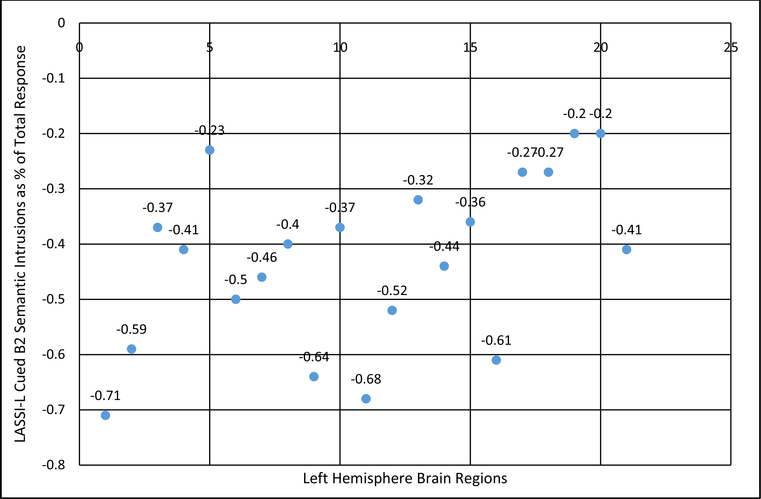

The percentage of semantic intrusion errors was related to decreases in cortical thickness in left hemisphere AD prone regions as well as other brain regions; however, after studying all 26 regions in the left hemisphere, only the bolded correlation coefficients survived correction for false discovery rate (Table 2). While the percentage of Cued B1 percentage intrusion errors was not related consistently to measures of cortical thickness, after correction for FDR, B2 percentage intrusion errors were related strongly to cortical depth in the ERC [r=−.71]; inferior temporal [r=−.68], medial orbital frontal [r=−.64], and middle temporal [r=−.61] cortex, and fusiform gyrus [r=−.59], but less so in other AD prone regions including areas such as rostral middle frontal, superior frontal, and superior temporal cortex and the temporal pole.

Table 2.

Cortical thickness measures and percentage of semantic intrusion errors.

| Center Hemisphere Measures | LASSI-L Cued B1 Semantic Intrusions (frPSI) as a Percentage of Total Responses | LASSI-L Cued B2 Semantic Intrusions (frPSI) as a Percentage of Total Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Entorhinal Cortex (ERC) | r=−.43 (p=.013) | r=−.71 (p<.001) |

| Fusiform | r=−.26 (p=.157) | r=−.59 (p<.001) |

| Parahippocampus | r=−.27 (p=.140) | r=−.37 (p=.038) |

| Precuneus | r=−.41 (p=.018) | r=−.41 (p=.021) |

| Posterior Cingulate | r=−.13 (p=.494) | r=−.23 (p=.213) |

| Rostral Top Frontal | r=−.12 (p=.510) | r=−.50 (p<.004) |

| Superior Frontal | r=−.15 (p=.425) | r=−.46 (p<.009) |

| Lateral Orbital Frontal | r=−.12 (p=.425) | r=−.40 (p<.023 |

| Medial Orbital Frontal | r=−.11 (p=.718) | r=−.64 (p<.001) |

| Caudal Top Frontal | r=−.15 (p=.402) | r=−.37 (p=.038) |

| Inferior Temporal | r=−.36 (p=.044) | r=−.68 (p<.001) |

| Superior Temporal | r=−.38 (p=.031) | r=−.52 (p<.002) |

| Frontal Pole | r=−.23 (p=.200) | r=−.32 (p=.079) |

| Temporal Pole | r=−.25 (p=.174) | r=−.44 (p<.011) |

| Banks Superior Temporal Sulcus | r=−.07 (p=.707) | r=−.36 (p<.043) |

| Top Temporal | r=−.40 (p=.023) | r=−.61 (p<.001) |

| Inferior Parietal | r=−.04 (p=.809) | r=−.27 (p=. 135) |

| Superior Parietal | r=−. 16 (p=.389) | r=−.27 (p=.164) |

| Supramarginal | r=−. 18 (p=.331) | r=−.20 (p=.266) |

| Rostral Anterior Cingulate | r=−.29 (p=. 114) | r=−.20 (p=.179) |

| Insula | r=−.13 (p=.496) | r=−.41 (p<.022) |

| Precentral | r=.02 (p=.934) | r=−.09 (p=.610) |

| Pericalcrine | r=−.25 (p=.176) | r=−.12 (p=.501) |

| Post-Central | r=.02 (p=.936) | r=−.10 (p=.571) |

| Cuneus | r=.07 (p=.688) | r=−.06 (p=.759) |

| Lateral Occipital | r=−.12 (p=.524) | r=−.30 (p=.096) |

Note: T Bolded Correlation Coefficients For Each LASSI-L Measure Are Statistically Significant After Correction for False Discovery Rate for Multiple MRI measures of at p<.05.

When amyloid load was entered along with cortical thickness in all of the statistically significant regions that demonstrated statistically significant relationships with percentage of Cued B2 semantic intrusions, the association with decreased cortical thickness in the left ERC and left medial orbital frontal regions accounted for a total multiple R of .812, explaining 66 percent of the variability in percentage of Cued b2 intrusions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of percentage of intrusion errors on cued 2 recall (vulnerable to frPSI).

| Predictor | Beta | Standardized Beta | t-value | Cumulative R | Cumulative R2 | Cumulative Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center Entorhinal Cortex (ERC) Thickness | −.19 (SE=.04) | −.55 | −4.68*** | .710 | .505 | .488 |

| Center Medial Orbital Thickness | −.48(SE=.13) | −.43 | −3.63*** | .812 | .660 | .636 |

p<.001

4. DISCUSSION

Presentation of a semantically related word list on the LASSI-L, employing the same three categories that are presented at target acquisition and cued recall of the original list of 15 targets across free and cued recall trials maximizes the effects of proactive semantic interference [PSI]. A unique aspect of the LASSI-L [unlike current measures of learning and memory], is that it provides a second opportunity to learn the competing List B targets, and performance deficits may reflect a failure to recover from the initial effects of PSI [frPSI]. We have previously shown that performance on the LASSI-L, particularly those vulnerable to frPSI, is highly discriminative between aMCI and cognitively normal groups [7, 9, 24] and is strongly related to loss of volume in several AD-prone brain regions among older adults with aMCI [9]. Gardini and colleagues [28] examined an MCI cohort with deficient performance on various semantic tasks, and found grey matter reductions in the parahippocampus, frontal and cingulate cortices and the amygdala compared to controls with no cognitive impairment. We have also reported that frPSI is strongly and uniquely related to amyloid load in the brains of community-dwelling elders who performed well on traditional neuropsychological measures [11]. However, our clinical experience indicates that a number of individuals who would be classified as cognitively unimpaired if only correct responses were taken into account, nonetheless generate a significant number of semantic intrusions on List B2 trials. In the present study, relative to correct items recalled on List B2 cued recall, the percentage of Cued B2 semantic intrusions [as a percentage of total responses] were uniquely related to amyloid load and exhibited higher correlation coefficients with measures of cortical thickness [CTh]. Moreover, decreased cortical thickness in the left entorhinal cortex [ERC] and left medial frontal lobe regions accounted for 66% of the total variability in percentage of B2 errors in regression models. The majority of these semantic intrusions [typically 75–80 percent] on List B2 trials represented actual semantically related targets from List A. The other intrusions belonged to the same semantic categories elicited on cued recall, but were not either List A or List B targets. The absolute number of intrusions in tests vulnerable on cued recall tests sensitive to PSI rather than correct number of responses has also not been reported previously, and clearly represents impairment of inhibition of semantically related responses. This highlights the potential importance of the use semantic intrusions or the semantic interference to total response ratios employed in the current investigation.

The strong association of left ERC and medial orbital frontal regions and a higher percentage of B2 cued recall intrusions likely reflect the inability to recover from PSI among our aMCI participants. We propose that it is not the initial failure of semantic interference, or merely impairments in strategic retrieval [29], but a deficiency in brain plasticity or functional connectivity in brain regions hindering the learning of semantically similar information over repeated trials. Simons and Spiers [30] postulated that the medial temporal and medial orbital frontal regions are responsible for discrete and elaborate representations of to-be-remembered targets involved in the learning process. These areas work in concert to reactivate and monitor different semantic associations and representations. In particular, deficits within this system may interfere with source memory that leads to semantic intrusion errors [29], particularly when using identical semantic cues employed to learn competing word lists [4]. Duarte et al. [31] have presented a compelling argument that connections between medial orbital frontal regions, and medial temporal cortex, are of vital importance in successful memory formation. This is consistent with the strong associations of the observed between left hemisphere ERC and medial orbital frontal regions with Cued B2 recall semantic intrusions.

A strength of this study was the use of elaborate, well- established and standardized operational criteria in the evaluation and diagnosis of aMCI patients and the availability of both amyloid load and cortical thickness data in these participants. We also controlled for spurious errors of interference using FDR procedures. Limitations include a modest sample of participants diagnosed with aMCI.

CONCLUSION

It is clear that measures such as percentage of intrusions on indices that measure frPSI, from LASSI-L recall trials, a novel cognitive stress test, shows promise in investigating early detection and tracking of individuals at risk for AD. Ongoing longitudinal studies will further elucidate the predictive utility of these types of measures with regards to progression, disease specificity, and response to emerging treatments.

Fig. (1).

Cortical Thickness Measures and Percentage of Semantic Intrusions on LASSI-L Cued B2 (measure of frPSI).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institute of Aging Grant number 5 P50 AG047726602 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (Todd Golde, PI) and 1 R01 AG047649–01A1 (David Loewenstein, PI). National Science Foundation awarded to Malek Adjouadi under NSF grants CNS-1532061, CNS-0959985, CNS-1551221 and HRD- 0833093.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the Internal Review Board of Mt. Sinai Medical Center.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All humans research procedures followed were in accordance with the standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki principles of 1975, as revised in 2008 (http://www.wma.net/en/20activities/10ethics/10helsinki/).

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All participants provided their informed consent to participate in the study and have their de-identified results published.

REFERENCES

- [1].Perry D, Sperling R, Katz R, Berry D, Dilts D, Hanna D. Building a roadmap for developing combination therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Rev Neurotherap 15(3): 327–33 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Brooks LG, Loewenstein DA. Assessing the progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: Current trends and future directions. Alzheimers Res Ther 2(5): 28 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rentz DM, Parra Rodriguez MA, Amariglio R, Stern Y, Sperling R, Ferris S. Promising developments in neuropsychological approaches for the detection of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: a selective review. Alzheimers Res Ther 5: 58 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Loewenstein DA, Curiel RE, Buschke H, Duara R. Novel cognitive paradigms for the detection of memory impairment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Assessment 25(3): 348–59 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Stern Y Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 47: 2015–28 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Buschke H [2014]. Rationale of the Memory Binding Test In Nilsson L-G & Ohta N [Eds.], Dementia and Memory [pp. 55–68]. Hove, England: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Crocco E, Curiel RE, Acevedo A, Czaja SJ, Loewenstein DA. An evaluation of deficits in semantic cueing and proactive and retroactive interference as early features of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatric Psychiat 22: 889–97 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Matias-Guiu JA, Curiel RE, Rognoni T, Valles-Salgado M, Fernández-Matarrubia M, Hariramani R, et al. Validation of the spanish version of the LASSI-L for diagnosing mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis 56(2): 733–42 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Loewenstein DA, Curiel RE, Wright C, Sun X, Alperin N, Crocco E, et al. Recovery from proactive semantic interference in mild cognitive impairment and normal aging: relationship atrophy in brain regions vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis 56(3): 1119–26 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Loewenstein DA, Curiel RE, DeKosky S, Rossell M, Bauer R, Grieg-Custo M, et al. Recovery from proactive semantic interference and MRI volume: a replication and extension study. J Alzheimer’s Dis 59(1): 131–39 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Loewenstein DA, Curiel RE, Greig MT, Bauer RM, Rosado M, Bowers D, et al. A novel cognitive stress test for the detection of preclinical Alzheimer disease: discriminative properties and relation to amyloid load. Am J Geriatr Psychiat 24(10): 804–13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].De Anna F, Attali F, Freynet L, Foubert L, Laurent A, Bubois B, et al. Intrusions in story recall: when overlearned information interferes with episodic memory recall. Cortex 44(3): 305–11 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Schnider A, Ptak R. Spontaneous confabulators fail to suppress currently irrelevant memory traces. Nat Neurosci 2: 677–81 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Moscovitch M, Melo B. Strategic retrieval and the frontal lobes: evidence from confabulation and amnesia. Neuropsychologia 35: 1017–34 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dickerson BC, Stoub TR, Shah RC, Sperling RA, Killiany RJ, Albert MS, et al. Alzheimer-signature MRI biomarker predicts AD dementia in cognitively normal adults. J Neurol 76: 1395–1402 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating [CDR]: current version and scoring rules. J Neurol 43: 2412–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res 12: 189–98 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].American Psychiatric Association. [2013]. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Benedict RHB, Schretlen D, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hopkins verbal learning test - revised: normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. Clin Neuropsychol 12: 43–55 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- [20].Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, Deitrich WD, Jacka ME, Wu J, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center [NACC] database: The Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 21: 249–58 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lucas JA, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Bohac DL, Tangalos EG, Graff- Radford NR, et al. Mayo’s older Americans normative studies: Category fluency norms. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 20: 194–200 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wechsler D [2008]. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition. Pearson, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual Motor Skills 8: 271–76 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- [24].Curiel RE, Crocco E, Acevedo A, Duara R, Agron J, Loewenstein DA. A new scale for the evaluation of proactive and retroactive interference in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Sci 1: 1 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- [25].Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B 57: 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. “Fsl,” Neuroimage 6: 782–90 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Villemagne VL, Pike KE, Chetelat G, Ellis KA, Mulligan RS, Bourgeat P, et al. Longitudinal assessment of Abeta and cognition in aging and Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 69: 181–92 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gardini S, Cuetos F, Fasano F, Ferrari Pellegrini F, Marchi M, Venneri A, et al. Brain structural substrates of semantic memory decline in mild cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res 10(4): 373–89 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Johnson MK. Source monitoring and memory distortion. Philosophical transactions of the royal society of London series B. Biol Sci 2: 1733–45 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Simons JS, Spiers HJ. Prefrontal and medial temporal lobe interactions in long-term memory. Nat Rev Neurosci 4: 637–48 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Duarte A, Henson RN, Knight RT, Emery T, Graham KS. Orbito-frontal cortex is necessary for temporal context memory. J Cogn Neurosci 22(8): 1819–31 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]