Abstract

Activation of c-Met plays a critical role in tumorigenesis, migration and invasion in lung cancer. Here, we explored the therapeutic efficacy of a novel small-molecule c-Met inhibitor (BPI-9016M) in lung adenocarcinoma and investigated the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Method: BPI-9016M, a c-Met tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor, was used to treat patient-derived xenografts (PDX) from lung adenocarcinoma in NOD/SCID mice. Immunohistochemistry and Western blot analysis were used to determine the expression of c-Met and its downstream signaling molecules. CCK8, wound healing, and trans-well assays were used to analyze cell proliferation, spreading, migration and invasion. RNA sequencing and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was used to screen and validate the expression of downstream genes in lung adenocarcinoma cells treated with BPI-9016M. Luciferase reporter assay was used to detect the interaction between miRNA and the targeted gene.

Results: BPI-9016M significantly suppressed growth in three out of four lung adenocarcinoma PDX models, particularly in the tumors with high expression of c-Met. In lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, BPI-9016M treatment resulted in increased miR203, which reduced migration and invasion and also repressed Dickkopf-related protein 1 (DKK1) expression. Forced overexpression of DKK1 or down-regulation of miR203 reversed the inhibitory effect of BPI-9016M on migration and invasion. C-Met was verified to positively and negatively associate with DKK1 and miR203, respectively. High expression of c-Met/DKK1 or low expression of miR203 related to poor outcome of lung adenocarcinoma patients. Furthermore, we observed significantly enhanced tumor cell growth inhibition upon combining BPI-9016M treatment with miR203 mimics or DKK1 siRNA.

Conclusion: Our data indicated that BPI-9016M is an effective agent against lung adenocarcinoma, particularly in tumors with c-Met activation, and likely functions through upregulation of miR203 leading to reduced DKK1 expression.

Keywords: lung adenocarcinoma, BPI-9016M, c-Met, miR203, Dickkopf-1 (DKK1)

Introduction

Lung cancer, one of the most malignant forms of human cancers, is a leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide. Lung adenocarcinoma is a common histological type, which accounts for 40% of all lung cancers 1. Recently, aberrant oncogenes and activated signaling pathways have been identified in lung adenocarcinoma, which are useful for developing targeted treatments. For example, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion and mutation, and mesenchymal epithelial transition receptor (c-Met) amplification and protein overexpression have been widely studied for targeting these genes in the treatment of lung cancer patients 2, 3.

C-Met belongs to a membrane tyrosine kinase receptor family and its dysregulation often occurs in various human malignant cancers 4-6. C-Met binding with its ligand, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), results in activation of multiple downstream signaling pathways including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt (PI3K-Akt) and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) 6, 7, triggering a series of pathological processes including proliferation, metastasis and resistance to therapy. Furthermore, c-Met can drive cancer invasion and metastasis by interacting with integrin β1 8 and alter the transcription of a panel of miRNAs that are involved in modulating tumorigenesis and drug resistance 9, 10. Thus, we hypothesized that the use of c-Met inhibitors combined with its downstream molecules might yield better response to targeted therapy for patients with malignant lung cancer.

BPI-9016M is a novel synthetic small-molecule inhibitor that was developed to target c-Met/AXL by Better Pharmaceuticals and has been explored to treat properly selected lung cancer patients 11-13. It has been applied to a phase Ib clinical trial in Chinese patients with advanced solid tumors. This drug has similar pharmacological targets as Cabozantinib, which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of metastatic medullary thyroid cancer 14 and advanced renal cell carcinoma 15.

In this study, we evaluated the role of the newly developed, highly selective small-molecule inhibitor of c-Met, BPI-9016M 16, in lung adenocarcinoma and explored its underlying regulatory mechanisms. We observed the antitumor effect of BPI-9016M on lung adenocarcinoma patient-derived xenografts (PDX) in NOD/SCID mice. Furthermore, we verified that BPI-9016M could inhibit proliferation, migration and invasion via miR203/DKK1 in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Combination of BPI-9016M and DKK1 siRNA or miR203 mimics strongly suppressed adenocarcinoma cell growth, suggesting that the use of c-Met inhibitor together with its downstream effector molecules might be a better strategy for lung adenocarcinoma treatment.

Methods

Cell lines, primary tumor cells and specimens

Human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines A549, H1299, H1650, H1975, HCC827, and PC-9 (American Type Culture Collection, ATCC) and primary tumor cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 g/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

165 frozen tumor tissues from lung adenocarcinoma patients who underwent radical surgery at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute were used in this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute, and all participants provided informed consent to participate in this research.

Reagents and cell transfection

BPI-9016M, which is a selective small-molecular c-Met inhibitor, was kindly provided by Better Pharmaceuticals (Zhejiang, China). BPI-9016M was dissolved in 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose sodium (CMC) for PDX treatment. For other experiments, the drug was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a stock concentration of 50 mM and stored at -80 °C. The DKK1 siRNA, miR103 mimic, miR203 mimic, miR103 inhibitor and miR203 inhibitor were constructed by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China) and the pENTER-DKK1 plasmid was purchased from Vigenebio (Maryland, USA). The transfections were performed according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (Lipo3000, Thermo Fisher, MA, USA).

Treatment for lung adenocarcinoma PDX

After validation of the histological type of adenocarcinoma, four lung adenocarcinoma PDX models were used in our study. We injected equal amounts of PDX tissues into NOD/SCID mice. When the tumors reached approximately 150-200 mm3 in volume, the mice were orally treated with 0.5% CMC as a vehicle or 60 mg/kg/day BPI-9016M. Tumors were measured every 2 days with fine calipers to calculate tumor growth inhibition (TGI) = (1 - RTVexperimental group) / RTVcontrol group) × 100%, where RTV is the relative tumor volume on the day mice were sacrificed with tumor volume calculated as length × width2 / 2. Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute.

Immunohistochemical staining

After treatment, the PDX tumor tissues were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded and stained using the primary antibodies against c-Met (1:400 dilution, #8198, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and Ki-67 (1:200 dilution, ZM-0167, ZSGB-BIO, China) followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated corresponding secondary antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, Dorset, UK). C-Met expression was evaluated by the H-score method 17. Scoring was independently reviewed in parallel by two experienced pathologists.

Western blot analysis

Tumor cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer (Cat No. CW2333S, CWBIO, Beijing, China) containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Cat No. 04693124001, Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Cat No. IPVH00010, Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). Subsequently, membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in TBST followed by addition of specific antibodies against phospho-c-Met (#3077), c-Met (#8198), phospho-AKT (#9271), AKT (#9272), phospho-ERK1/2 (#4370), ERK1/2 (#9102), β-actin (#3700), E-cadherin (#3195), N-cadherin (#13116), and vimentin (#5741) purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-human DKK1 antibody (CatNo.21112-1-AP) was obtained from Proteintech. Signals were visualized by chemiluminescence (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA).

Colony formation

Approximately 500 cells were plated on 6-well plates. Two weeks later, visible colonies were fixed and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. All experiments were performed in triplicate wells.

Cell cycle assay

Following treatment with BPI-9016M for 24 h, cells were collected and fixed in 70% cold ethanol overnight at 4 °C. Fixed cells were stained with 50 μg/mL propidium iodide (Cat No.550825, BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA) and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 min, then analyzed using a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer. Data were analyzed by ModFit 3.0 software.

Wound healing assay

Cell spreading was measured with a wound-healing assay. After the cells were attached in medium containing 1% serum, scratches were made using a 100 μL plastic pipette tip. The wound size was measured at 12, 24, and 36 h and the wound healing rate was calculated.

Transwell assay

Cells were seeded in transwell chambers (Cat NO. 3422, Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA) and treated with 12.5 μM BPI-9016M or vehicle to evaluate migration and invasion. For the invasion assay, Matrigel (Cat NO. 356234, BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA) was used for cell culture in the top chambers. After 12 h, the cells in the bottom chambers were fixed in paraformaldehyde (4%) and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 5 min at room temperature. The assay was performed in triplicate and representative images (×100) of migrated and invasive cells stained with crystal violet were recorded.

RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

A549 cells were treated with vehicle or 12.5 μM BPI-9016M for 48 h. Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. MRNA sequences were generated using NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit from Illumina® (NEB, USA) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. Index of the reference genome was built using Bowtie v2.2.3 and paired-end clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using TopHat v2.0.12. HTSeq v0.6.1 was used to count the reads numbers mapped to each gene. FPKM of each gene was calculated based on the length of the gene and the reads count mapped to that gene. Differential expression analysis of two conditions was performed using the DEGSeq R package (1.20.0). P values were adjusted using the Benjamini & Hochberg method. Corrected P-value of 0.005 and log2 (fold change) of 1 were set as the threshold for significant differential expression. Pathway analysis was used to identify the significant pathways of the differentially expressed genes according to the KEGG database.

Reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. 2 μg of total RNA was transcribed with TransScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Cat No. AE301-02, Transgene biotech, Bejing, China). For the microRNA analysis, a polyA tail was added to 0.1 μg of total RNA by polyA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA) followed by reverse transcription with oligo-dT adapter primers 18. Subsequently, qPCR was performed with Go Taq qPCR Master Mix (Cat No. A6001, Promega Corporation, Madison, USA). Cycling conditions were as follows: 5 min at 95 °C followed by 45 cycles each consisting of 10 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 60 °C and 30 s at 72 °C. The relative concentration of genes was normalized to β-actin. Fold change was calculated by the 2-△Ct method. The primers are listed in Table S1.

Luciferase reporter assay

TargetScan predicted the potential miR-203 binding sites in DKK1 3'UTR. Sequences containing wild-type or mutant seed region of DKK1 (Figure 6E) were synthesized and cloned into pGL3-control luciferase plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI). Cells in 24-well plates were co-transfected with miR-203 mimics and control, pGL3 constructions and renilla using Lipo3000. After transfection for 48 h, luciferase activity was measured using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system according to the manufacturer's instruction (Promega, Madison, WI).

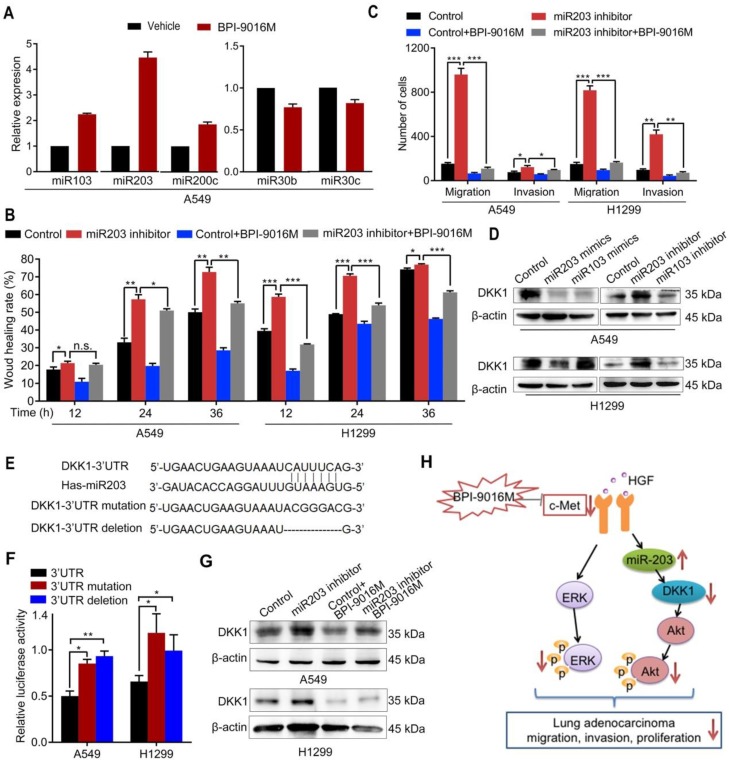

Figure 6.

BPI-9016M increases miR203 and decreases DKK1. (A) miR103, miR203, miR200c, miR30b and miR30c expression levels by qPCR in A549 cells treated with BPI-9016M. U6 was used as the internal control. (B) Wound healing analyses of spreading miR203 inhibitor-transfected A549 and 1299 cells with BPI-9016M treatment. (C) Transwell assays to assess cell migration and invasion in miR203 inhibitor-transfected A549 and H1299 cells with or without BPI-9016M treatment. (D) Western blotting analyses demonstrating DKK1 expression in A549 and H1299 cells with miR103 or mi203 mimics (50 nM) and miR103 or miR203 inhibitors (50 nM). (E) The binding site of miR203 in the DKK1 3'-UTR is shown. 3'-UTR wild-type; 3'-UTR mutation and deletion sequences of the DKK1 3'-UTR. (F) Firefly luciferase activity between miR203 and wild-type, mutated, and deleted constructs of DKK1 3'-UTR. (G) Western blotting analysis showing DKK1 expression in A549 and H1299 cells with or without BPI-9016M/miR203 inhibitor. (H) A schematic illustration showing that BPI-9016M-inhibited proliferation, migration and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma is associated with ERK activation and miR203-DKK1-AKT signaling. (B-C, F) * p<0.05, ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times and representative results are shown in the figures. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA was used to analyze the mean between different groups. Spearman's rho correlation test (two-tailed) was used to estimate the correlation between the expressions of genes in the lung adenocarcinoma tissues. Survival curves were established using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 software. P < 0.05 was considered a significant difference.

Results

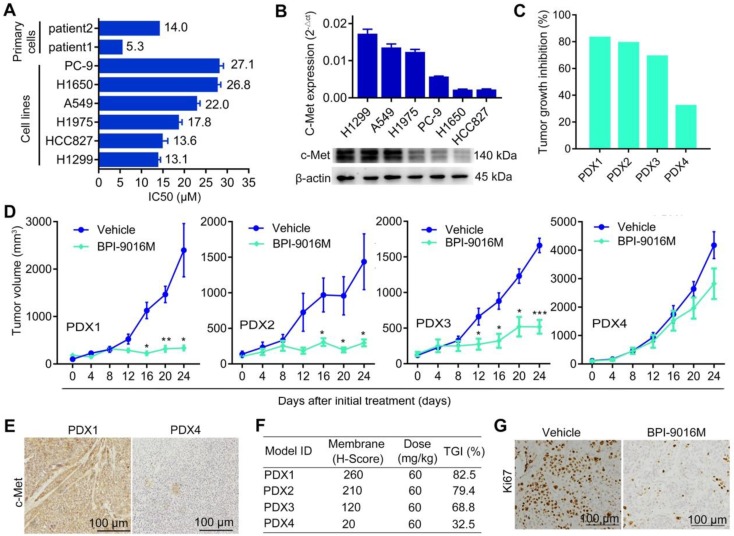

BPI-9016M suppresses lung adenocarcinoma growth

We first determined the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of BPI-9016M in several lung adenocarcinoma cell lines as well as in primary lung adenocarcinoma cells, which ranged from 5.3 μM to 27.1 μM (Figure 1A). Next, we examined c-Met expression in the cell lines and found relatively higher expression in the A549 and H1299 cells by qPCR and Western blot analyses (Figure 1B). We further assessed the therapeutic effect of BPI-9016M on four lung adenocarcinoma PDX models. NOD/SCID mice with appropriately sizes tumors were divided into two groups that received oral administration of 0.5% CMC (vehicle) or BPI-9016M treatment daily. Variable tumor growth inhibition (TGI) was obtained in the four PDX1-4 xenografts treated with BPI-9016M (Figure 1C). Compared to the vehicle treatment, BPI-9016M dramatically restrained tumor growth in PDX1, PDX2 and PDX3 xenografts after 16 or 12 days of treatment (Figure 1D). At the same dose, BPI-9016M suppressed PDX4 xenografts without statistical significance.

Figure 1.

BPI-9016M suppresses tumor growth in lung adenocarcinoma. (A) Two primary tumor cells and six cell lines of lung adenocarcinoma were treated with serially diluted BPI-9016M for 48 h and IC50 was calculated as shown in the bar graph. (B) QPCR (top panel) and Western blot (bottom panel) analyses show c-Met expression in lung adenocarcinoma cell lines including H1299, A549, H1975, PC-9, H1650 and HCC827. (C) Tumor growth inhibition in PDX1, PDX2, PDX3 and PDX4 models following BPI-9016M treatment. (D) Tumor volume in the PDX1, PDX2, PDX3 and PDX4 models with BPI-9016M or vehicle treatment. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 at indicated time point. (E) Representative images (×200 magnification) of c-Met by immunohistochemical staining of the BPI-9016M-treated PDX1 and PDX4 tissues. (F) H-score to evaluate c-Met expression and tumor growth inhibition (TGI) in the four PDX models after administration of BPI-9016M. (G) Representative images (×200 magnification) of Ki67 staining of the PDX1 tumors with vehicle or BPI-9016M treatment.

Based on previous data showing a correlation between c-Met expression level and antitumor efficacy 17, we determined c-Met expression in the PDX tissues following BPI-9016M treatment by H-score analysis. Dramatically stronger expression of c-Met and higher TGI were observed in the PDX1, PDX2 and PDX3 tumors compared to those in the PDX4 tumors with H-scores of 260, 210, 120 vs. 20 and TGI of 82.5%, 79.4%, 68.8% vs. 32.5%, respectively (Figure 1E-F). Furthermore, lower expression of ki-67 was observed in the BPI-9016M-treated PDX1 tumors (Figure 1G). These data showed that BPI-9016M significantly inhibited tumor growth of lung adenocarcinoma with overexpression of c-Met.

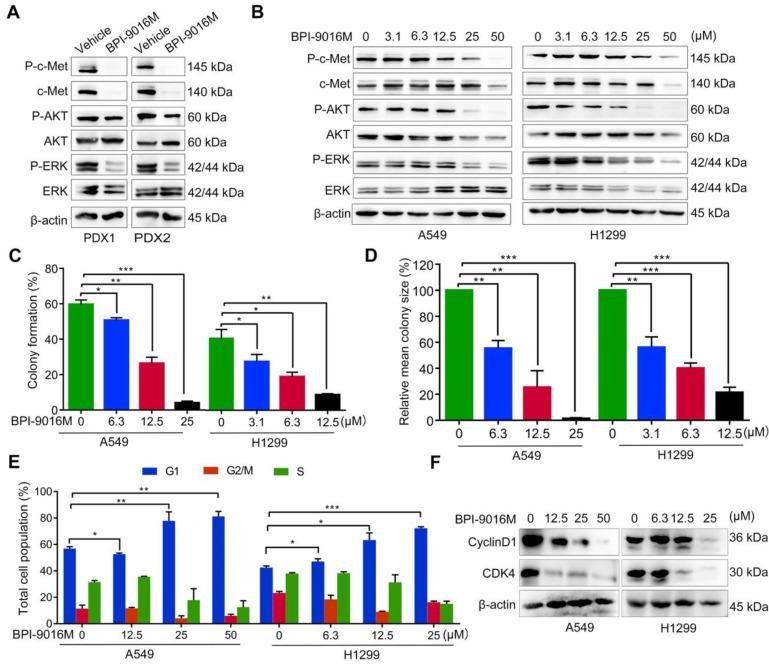

BPI-9016M inhibits AKT and ERK activation, reduces cell proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest

We further determined whether BPI-9016M influenced downstream signaling targets of c-Met, such as ERK and AKT. We detected inactivation of phosphorylated (p)-AKT and p-ERK in the BPI-9016M-treated PDX1 and PDX2 tumors (Figure 2A). Since c-Met is expressed at relatively high levels in the A549 and H1299 cells (Figure 1B), we treated these two cell lines with BPI-9016M. As shown in Figure 2B, expression of c-Met, p-c-Met, p-AKT and p-ERK was reduced in the BPI-9016M-treated H1299 and A549 cells in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 2.

BPI-9016M inhibits downstream signals of c-Met, colony formation and cell cycle. (A) C-Met, ERK, AKT, and phosphorylation of these protein were detected by Western blotting in the PDX tissues following vehicle or BPI-9016M treatment. (B) C-Met, ERK, AKT, and phosphorylation of these protein were detected by Western blotting in the A549 and H1299 cells after treatment with serial doses of BPI-9016M treatment. (C-D) Colony formation rate (C) and colony size (D) of A549 and H1299 cells treated with BPI-9016M. (E) Cell cycle distribution of A549 and H1299 cells treated with BPI-9016M. (F) Cyclin D1 and CDK4 were analyzed by Western blotting of cells after treatment with BPI-9016M. (C- E) * p<0.05, ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001.

Subsequently, we used a variable dose of BPI-9016M to detect the colony formation ability of A549 and H1299 cells. After 2 weeks of treatment, colony formation was significantly inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2C-D). We also explored the distribution of BPI-9016M-treated cells in various phases of cell cycle. As expected, BPI-9016M induced accumulation of more tumor cells in the G1 phase (Figure 2E and Figure S1A). The cell cycle phase G1-related proteins, cyclin D1 and CDK4, were also down-regulated (Figure 2F). We thus concluded that BPI-9016M inhibited cell proliferation and cell cycle progression of lung adenocarcinoma.

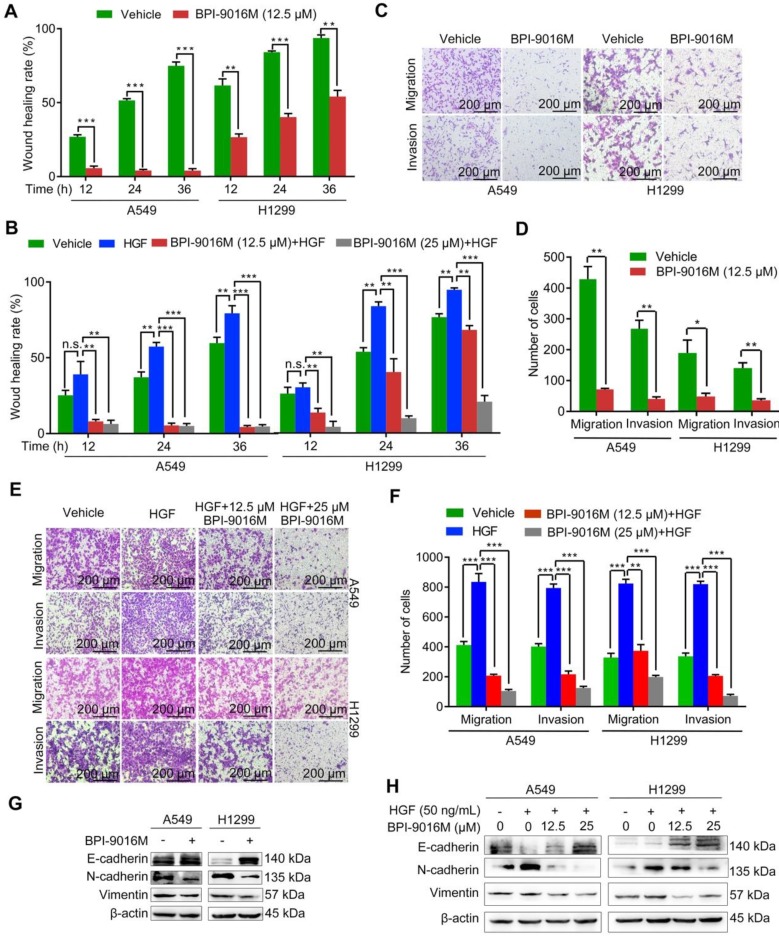

BPI-9016M inhibits migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

It has been reported that HGF/c-Met signaling plays a significant role in cellular motility and EMT 4, 19. The A549 and H1299 cells showed high potential for migration and invasion, which was consistent with the relatively elevated expression level of c-Met (Figure S1B). We then tested whether BPI-9016M could suppress the spreading, migration and invasion properties of these two cell lines. Compared to the control cells, slower spreading was observed in the A549 and H1299 cells treated with BPI-9016M for 12, 24, and 36 h (Figure 3A and Figure S2A). HGF promoted spreading of the A549 and H1299 cells and BPI-9016M inhibited spreading of the HGF-treated tumor cells (Figure 3B and Figure S2B), results that were further confirmed in cell migration and invasion assays showing significant suppression by BPI-9016M on the migration and invasion of A549 and H1299 cells (Figure 3C-D). Furthermore, BPI-9016M inhibited the HGF-induced enhanced migration and invasion in both cell lines (Figure 3E-F).

Figure 3.

BPI-9016M suppresses spreading, migration and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma. (A) Spreading ability assessed by the wound-healing assay of A549 and H1299 cells treated with BPI-9016M for 12, 24 and 36 h. (B) The spreading ability of A549 and 1299 cells treated with BPI-9016M, HGF or a combination of these two chemicals for 12, 24 and 36 h. (C) Representative images (×100 magnification) of migrated and invasive A549 and 1299 cells stained with crystal violet after treatment with vehicle or BPI-9016M. (D) The number of migrated and invasive cells treated with vehicle or BPI-9016M. (E) Representative images (×100 magnification) of migrated and invasive A549 and 1299 cells stained with crystal violet after treatment with HGF, BPI-9016M, or a combination of these two chemicals. (F) The number of migrated and invasive cells treated with HGF, BPI-9016M, or a combination of these two chemicals. (G) EMT-associated molecules including E-cadherin, N-cadherin and vimentin were assessed by Western blotting of A549 and 1299 cells after BPI-9016M treatment. (H) E-cadherin, N-cadherin and vimentin were detected by Western blotting in A549 and 1299 cells treated with HGF, BPI-9016M, or a combination of these two chemicals. (A-B, D, F) * p<0.05, ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001.

As has been amply shown previously, EMT is often involved in tumor migration and invasion. BPI-9016M led to up-regulation of E-cadherin (epithelial marker) and down-regulation of N-cadherin and vimentin (mesenchymal markers) in both A549 and H1299 cells by Western blot analysis (Figure 3G). In contrast, HGF decreased E-cadherin and increased N-cadherin and vimentin expression levels, effects that could be attenuated by BPI-9016M (Figure 3H). These data indicated that BPI-9016M significantly decreased the migration, invasion, and EMT of lung adenocarcinoma.

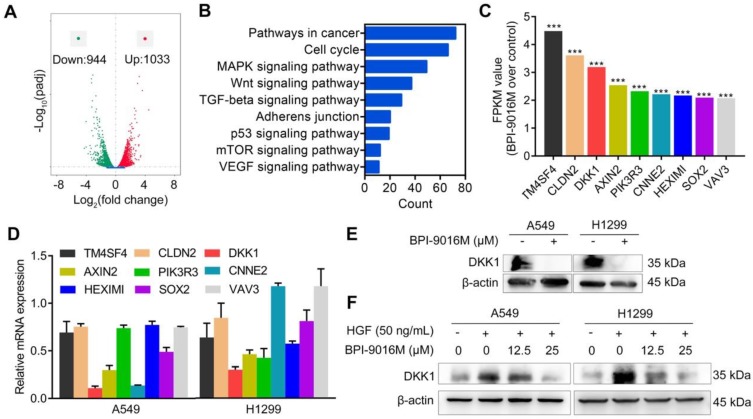

BPI-9016M restrains migration and invasion through DKK1

To get a better insight into the molecular mechanisms of BPI-9016M in migration and invasion, we performed RNA profiling in A549 cells treated with the drug. We observed down-regulation of 944 genes and up-regulation of 1033 genes in cells treated with BPI-9016M (|fold change| > 2, Figure 4A). As shown in Figure 4B and Figure S3A, numerous signaling pathways including cell cycle, MAPK, Wnt, TGF-beta, adherens junction, p53, mTOR, and VEGF were enriched in the BPI-9016M-treated A549 cells, highlighting the effect of BPI-9016M on various signaling pathways associated with malignancy. Based on the role described above of BPI-9016M in inhibiting the migration and invasion of tumor cells, nine genes associated with metastasis were identified from the top 70 down-regulated genes (Figure 4C and Table S2). Seven out of nine genes were down-regulated in BPI-9016M-treated A549 and H1299 cells by qPCR analysis (Figure 4D). Among these genes, BPI-9016M primarily suppressed DKK1 in both cell lines. We then confirmed the decreased expression of DKK1 by Western blotting of the cells treated with BPI-9016M (Figure 4E). As expected, HGF induced DKK1 expression and BPI-9016M abolished the increased DKK1 expression stimulated by HGF (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

BPI-9016M inhibits DKK1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma cells. (A) Volcano plot depicting a log transformation plot of the fold difference (x-axis) and the p value (y-axis) of indicated genes between BPI-9016M-treated cells and control cells (vehicle treatment). (B) Signaling pathways were enriched in the BPI-9016M-treated A549 cells over the vehicle control by KEGG analysis using RNA sequencing. (C) FPKM values of nine genes associated with metastasis in the BPI-9016M-treated A549 cells by RNA sequencing analysis. ***P<0.0001. (D) The nine genes were investigated in the BPI-9016M-treated A549 cells by qPCR analysis. (E) Western blotting analysis shows the DKK1 expression level in BPI-9016M-treated A549 and H1299 cells. (F) Western blotting analysis shows the DKK1 expression level in cells treated with HGF and BPI-9016M alone or in combination.

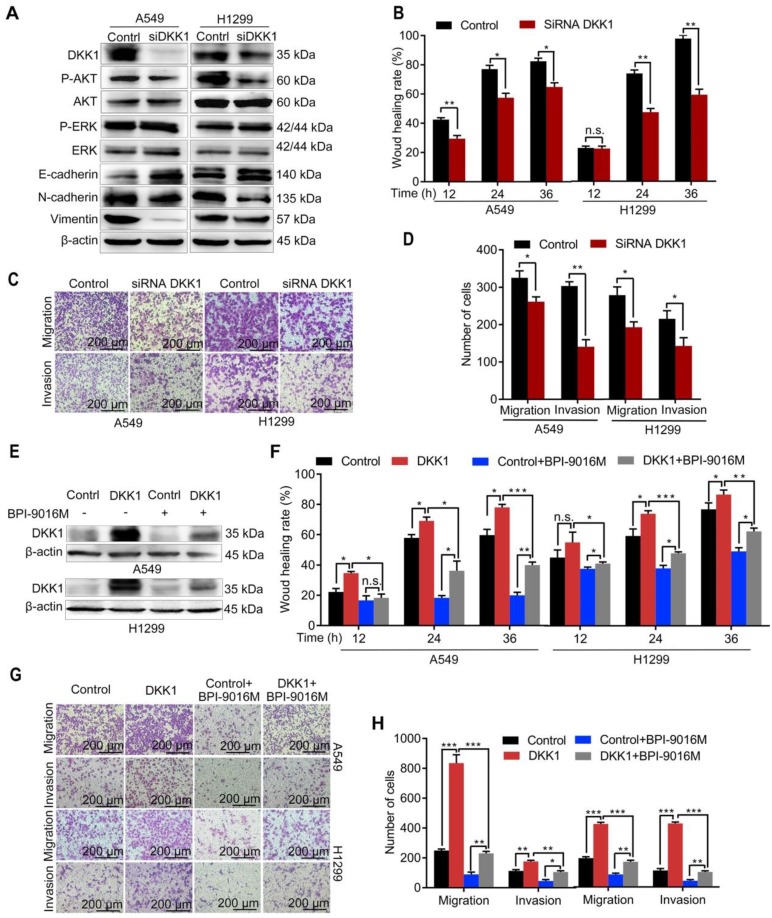

We further focused on DKK1 as it was reported to be up-regulated in several malignant tumors and is associated with metastasis 20, 21. When DKK1 was knocked down in A549 and H1299 cells, we observed decreased expression of p-Akt, N-cadherin, and vimentin and increased expression of E-cadherin (Figure 5A), while there was almost no change in p-ERK expression. Depletion of DKK1 also inhibited spreading, migration and invasion of A549 and H1299 cells (Figure 5B-D and Figure S4A). Also, BPI-9016M partially reversed DKK1 expression level in the A549 and H1299 cells with exogenously overexpressed DKK1 (Figure 5E). Moreover, DKK1 overexpression promoted cell spreading, migration and invasion and BPI-9016M treatment could partially overcome this effect (Figure 5F-H and Figure S4B). These findings strongly suggested that BPI-9016M controls cell migration and invasion by down-regulating DKK1.

Figure 5.

BPI-9016M inhibits tumor migration and invasion through DKK1. (A) Western blots showing DKK1, p-AKT, AKT, ERK, p-ERK, E-cadherin, N-cadherin and vimentin expressions in A549 and 1299 cells transfected with DKK1 siRNA. (B) Wound-healing analysis of spreading of A549 and 1299 cells transfected with DKK1 siRNA for 12, 24 and 36 h. (C) Representative images (×100 magnification) of migrated and invasive A549 and 1299 cells stained with crystal violet that were transfected with DKK1 siRNA. (D) The number of migrated and invasive cells transfected with DKK1 siRNA. (E) Western blots showing DKK1 expression in A549 and 1299 cells overexpressing DKK1 with or without BPI-9016M treatment. (F) Wound-healing analyses of DKK1-overexpressing A549 and 1299 cells treated with BPI-9016M for 12, 24 and 36 h. (G) Representative images (×100 magnification) of migrated and invasive DKK1-overexpressing A549 and 1299 cells with or without BPI-9016M treatment. (H) The number of migrated and invasive cells in DKK1-overexpressing A549 and 1299 cells with or without BPI-9016M treatment. (B, D, F, H) * p<0.05, ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001.

BPI-9016M regulates miR203/DKK1 signals

In a previous study, Garofalo et al. investigated global miRNA expression profiles in lung cancer cells with suppression of EGFR and c-Met 10. Based on their study, we tested whether BPI-9016M inhibited DKK1 through miRNAs that influence cell migration and invasion. Consistent with the above study, we found increased expression of miR103, miR200c, and miR203 and decreased expression of miR30b and miR30c in A549 cells following treatment with BPI-9016M (Figure 6A). Among these aberrant miRNAs, miR203 showed the highest elevation in the BPI-9016M-treated A549 cells. We also observed that miR203 inhibitor induced spreading, migration and invasion and that BPI-9016M abolished these effects (Figure 6B-C and Figure S5A-B).

We found that the miR203 mimics reduced DKK1 expression while DKK1 inhibitors induced its expression in A549 and H1299 cells (Figure 6D). As per TargetScan prediction (http://www.targetscan.org/), DKK1 3'-UTR contains binding sites for miR203 and miR103. To determine whether DKK1 is the target of miR203, we mutated and/or deleted the sequence within the binding site of miR203 on the DKK1 3'-UTR (Figure 6E). In both A549 and H1299 cells, luciferase activity was significantly inhibited in the wild-type 3'-UTR of DKK1 compared to its mutation and deletion constructs (Figure 6F). Furthermore, the miR203 inhibitor reversed the decreased expression of DKK1 by BPI-9016M in these two cell lines (Figure 6G). Thus, our data showed that BPI-9016M could suppress migration and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma cells via miR203-DKK1-p-Akt signaling (Figure 6H).

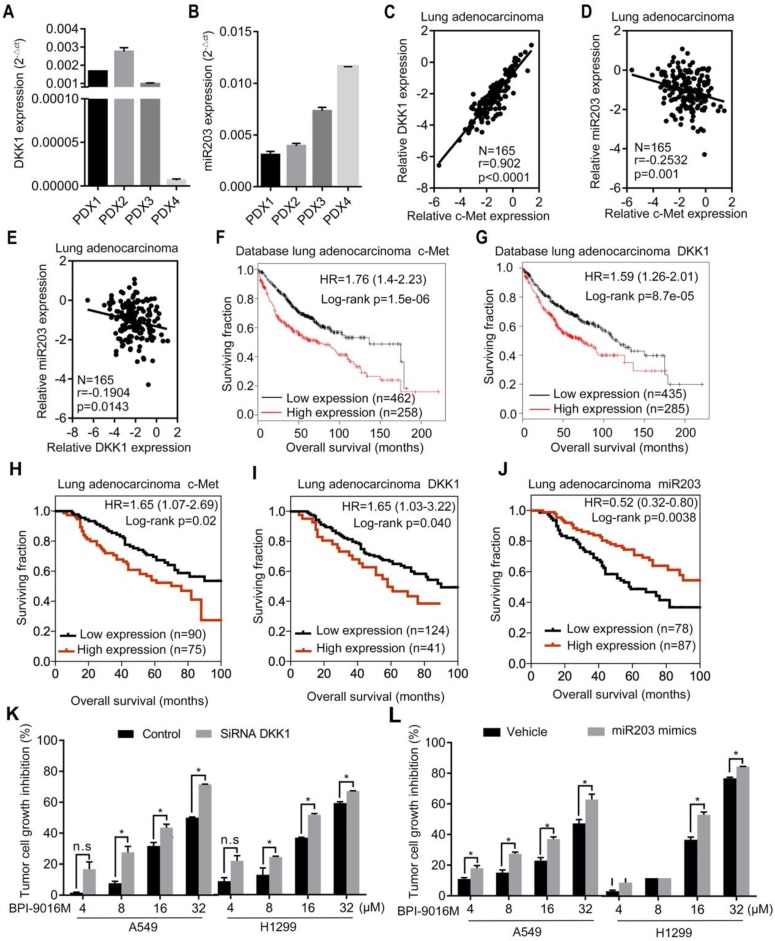

Clinical significance of BPI-9016M targeting of c-Met, miR203 and DKK1 in lung adenocarcinoma

We detected DKK1 and miR203 expression levels in four lung adenocarcinoma PDX models. The PDX1, PDX2, and PDX3 models exhibited relatively higher expression levels of DKK1 and lower expressions of miR203 than the PDX4 model (Figure 7A-B). Based upon the in vitro results, elevated expression of c-Met or DKK1 or reduced expression of miR203 may result in better therapeutic response to BPI-9016M.

Figure 7.

Clinical significance of BPI-9016M targeted to c-Met, DKK1 and miR203. (A-B) QPCR analyses showing DKK1 (A) and miR203 (B) expressions in the four cases of PDX tissues of lung adenocarcinoma. (C-E) Correlations between c-Met and DKK1 (C), c-Met and miR203 (D) and DKK1 and miR203 (E). (F-G) Kaplan-Meier plots showing overall survival of lung adenocarcinoma patients with high or low expression of c-Met (G) and DKK1 (H) from the database (http://www.kmplot.com). (H-J) Kaplan-Meier plots showing overall survival of lung adenocarcinoma patients from Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute with high or low expression of c-Met (H), DKK1 (I) and miR203 (J). (K) Tumor cell growth inhibition (%) of DKK1 siRNA-transfected cells treated with variable doses of BPI-9016M. (L) Tumor cell growth inhibition (%) of miR203 mimics-transfected cells treated with variable doses of BPI-9016M. (K-L) n.s.: no statistically significant difference; *p<0.05, ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001; HR: hazard ratio.

Next, by using qPCR, we analyzed the relationship between c-Met, DKK1 and miR203 in 165 lung adenocarcinoma tissues from Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. A positive correlation was observed between c-Met and DKK1, whereas a negative correlation was detected between miR203 and c-Met/DKK1 (Figure 7C-E). The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of the database (lung adenocarcinoma, http://www.kmplot.com) showed that high expression of either c-Met or DKK1 was associated with shorter overall survival of patients with lung adenocarcinoma (Figure 7F-G). We further assessed c-Met, DKK1 and miR203 expressions in specimens of the 165 lung adenocarcinomas mentioned above; the expression levels of these genes were categorized as low and high in relation to the Youden index. As shown in Figure 7H-J, high expression of c-Met/DKK1 or low expression of miR203 was associated with poor outcome of lung adenocarcinoma patients.

Furthermore, we investigated whether BPI-9016M in combination with DKK1 siRNA or miR203 mimics could increase antitumor growth efficacy. As expected, BPI-9016M and DKK1 siRNA significantly elevated TGI of A549 and H1299 cells (Figure 6K). Also, BPI-9016M combined with miR203 mimics further enhanced TGI of the two lung cancer cell lines (Figure 6L).

Discussion

Targeting receptor tyrosine kinases is considered an effective therapeutic approach for the treatment of lung adenocarcinoma 3, 22. C-Met is a tyrosine kinase receptor, and its aberrant status has frequently been found in various cancer types including lung adenocarcinoma 23-25. Herein, we explored the antitumor effect of a novel small-molecule, BPI-9016M, that targets c-Met tyrosine kinase receptor in lung adenocarcinoma. A better understanding of the complicated molecular details underlying the mechanism of this inhibitor might contribute to improvements in therapies targeting c-Met. Thus, we further explored the function of BPI-9016M and found that it may mediate the suppression, proliferation, migration and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma through increasing miR203, which drives DKK1 and p-Akt signaling activation.

A low frequency of c-Met amplification but high frequency of protein expression has been reported in lung adenocarcinoma 2, 26, 27. It was reported that the antitumor effect of c-Met inhibitor was not limited to amplification and genetic alterations in c-Met but depends on the overexpressed c-Met protein. We first administered BPI-9016M into lung adenocarcinoma PDX mice and obtained an antitumor effect that was proportional to the c-Met expression level. When we used H-score analysis for evaluating c-Met protein expression level 17, we found a better response to BPI-9016M treatment in the lung adenocarcinoma PDX with high H-score, suggesting a potential clinical application of the drug.

Binding of HGF ligand to its receptor, c-Met, induces receptor dimerization and activates downstream signal transduction. It is generally believed that HGF/c-Met functions to promote cell proliferation, tumor invasion and migration 28, 29. Consistent with previous reports, BPI-9016M has been demonstrated to suppress cell growth, migration and invasion, and to control these malignant features even after treatment with HGF. It has been shown that HGF/c-Met promoted EMT during the development and proliferation of cancer cells 23, 28, 29. BPI-9016M treatment up-regulated the epithelial marker E-cadherin and down-regulated the mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin even after HGF administration. These data suggested that BPI-9016M could mostly block proliferation, migration and invasion by an HGF-dependent c-Met pathway as well as influence the EMT process.

C-Met has been found to regulate downstream signaling pathways such as MAPK, PI3K/Akt, NF-κB and STAT3, which are regulated by several different tyrosine kinase receptors 30-32. These signaling pathways are known to drive cancer cell survival, motility and invasion. We identified that ERK, which is a terminal effector of the MAPK pathway, was suppressed in the lung adenocarcinoma cells treated with BPI-9016M. Furthermore, BPI-9016M treatment also resulted in inactivation of Akt signaling. Besides these widely studied signaling pathways, we screened molecules associated with tumor migration and invasion in the BPI-9016M-treated lung adenocarcinoma cells. Based on screening with RNA sequencing and qPCR validation, we found that BPI-9016M treatment primarily down-regulated DKK1 expression and a positive correlation was seen in the lung adenocarcinoma tissues between c-Met and DKK1. DKK1 was previously identified as a tumor suppressor that binds with Wnt co-receptor low density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 6 (LRP6) to suppress canonical β-catenin Wnt signaling 33. In contrast, DKK1 was found to be elevated in cancer tissues and associated with cancer aggressiveness 20, 21. The role of DKK1 in promoting cancer progression could be through a novel receptor cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 (CKAP4) 34. We overexpressed DKK1, which abolished the inhibitory effect of BPI-9016M on cell migration and invasion. Furthermore, knockdown of DKK1 suppressed p-AKT but not p-ERK. Our data suggested that BPI-9016M might be associated with activation of ERK and DKK1/AKT signals to control cellular aggression.

In a previous study by Garofalo et al., a panel of miRNAs (miR103, miR203, miR200c, miR30b and miR30c) was found to be altered in lung cancer cells when c-Met was knocked down 10. Among these, miR203 was reported to decrease cell migration and invasion in lung cancer cells 35, 36. Consistently, BPI-9016M treatment up-regulated miR103 and miR203 expression levels. Both miR103 and miR203 have binding sequences for the 3'-UTR of DKK1. In our current study, miR203 directly targeted DKK1 and had an inverse relationship with this gene. Furthermore, miR203 inhibitor could partially rescue BPI-9016M effects on enhanced spreading, migration, and invasion as well as increased DKK1 expression. DKK1 has been reported to bind with CKAP4 to activate p-Akt through PI3K 37. Taken together, BPI-9016M inhibited migration and invasion that might be associated with ERK signaling and induced miR203/reduced DKK1-Akt activation (Figure 6H).

C-Met is required for embryonic development, and overexpression of this oncogene is associated with poor outcome in numerous human cancers 4, 38. C-Met exhibited a positive correlation with DKK1 and a negative correlation with miR203. In tumor tissues, high expression of c-Met/DKK1 or low expression of miR203 was associated with poor outcome of lung adenocarcinoma patients. Furthermore, BPI-9016M combined with DKK1 siRNA or miR203 strongly inhibits tumor cell growth, indicating an increased therapeutic effect of combinational BPI-9016M and the downstream' inhibitor or analogue of c-Met. In summary, BPI-9016M is of therapeutic value in lung adenocarcinoma and inhibits cell growth, migration and invasion via miR203-DKK1 signaling. The combined use of three members of this axis may represent a better therapeutic strategy for lung adenocarcinoma treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 81772494 and 81502578), Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding (No. ZYLX201509) and Peking University (PKU) 985 Special Funding for Collaborative Research with PKU Hospitals. We thank Better Pharmaceuticals (Zhejiang, China) for providing BPI-9016M.

Author Contributions

Yue Yang and Yuanyuan Ma designed the study and acquired funding; Panpan Zhang and Shaolei Li mainly carried out the molecular biology experiments; Chao Lv did statistical analysis; Jiahui Si and Ying Xiong performed the cell culture and animal models experiments.

Abbreviations

- ALK

anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- CMC

carboxymethylcellulose sodium

- C-Met

mesenchymal-epithelial transition receptor

- DKK1

Dickkopf-related protein 1

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- PDX

patient-derived xenografts

- TGI

tumor growth inhibition.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–50. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denisenko TV, Budkevich IN, Zhivotovsky B. Cell death-based treatment of lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:117. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0063-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trusolino L, Bertotti A, Comoglio PM. MET signalling: principles and functions in development, organ regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:834–48. doi: 10.1038/nrm3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gherardi E, Birchmeier W, Birchmeier C, Vande Woude G. Targeting MET in cancer: rationale and progress. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:89–103. doi: 10.1038/nrc3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eder JP, Vande Woude GF, Boerner SA, LoRusso PM. Novel therapeutic inhibitors of the c-Met signaling pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2207–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Babic A. Regulation of the MET oncogene: molecular mechanisms. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37:345–55. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jahangiri A, Nguyen A, Chandra A, Sidorov MK, Yagnik G, Rick J. et al. Cross-activating c-Met/beta1 integrin complex drives metastasis and invasive resistance in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E8685–E94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701821114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acunzo M, Romano G, Palmieri D, Lagana A, Garofalo M, Balatti V. et al. Cross-talk between MET and EGFR in non-small cell lung cancer involves miR-27a and Sprouty2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8573–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302107110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garofalo M, Romano G, Di Leva G, Nuovo G, Jeon YJ, Ngankeu A. et al. EGFR and MET receptor tyrosine kinase-altered microRNA expression induces tumorigenesis and gefitinib resistance in lung cancers. Nat Med. 2011;18:74–82. doi: 10.1038/nm.2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Gozdzik-Spychalska J, Szyszka-Barth K, Spychalski L, Ramlau K, Wojtowicz J, Batura-Gabryel H. et al. C-MET inhibitors in the treatment of lung cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2014;15:670–82. doi: 10.1007/s11864-014-0313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto N, Murakami H, Hayashi H, Fujisaka Y, Hirashima T, Takeda K. et al. CYP2C19 genotype-based phase I studies of a c-Met inhibitor tivantinib in combination with erlotinib, in advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2803–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhardwaj V, Zhan Y, Cortez MA, Ang KK, Molkentine D, Munshi A. et al. C-Met inhibitor MK-8003 radiosensitizes c-Met-expressing non-small-cell lung cancer cells with radiation-induced c-Met-expression. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1211–7. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318257cc89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weitzman SP, Cabanillas ME. The treatment landscape in thyroid cancer: a focus on cabozantinib. Cancer Manag Res. 2015;7:265–78. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S68373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruiz-Morales JM, Heng DY. Cabozantinib in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: clinical trial evidence and experience. Ther Adv Urol. 2016;8:338–47. doi: 10.1177/1756287216663073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui X, Zheng X, Jiang J, Tan F, Ding L, Hu P. Simultaneous determination of a novel c-Met/AXL dual-target small-molecule inhibitor BPI-9016M and its metabolites in human plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: Application in a pharmacokinetic study in Chinese advanced solid tumor patients. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2017;1068-1069:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Anderson MG, Oleksijew A, Vaidya KS, Boghaert ER, Tucker L. et al. ABBV-399, a c-Met Antibody-Drug Conjugate that Targets Both MET-Amplified and c-Met-Overexpressing Tumors, Irrespective of MET Pathway Dependence. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:992–1000. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao B, Han H, Chen J, Zhang Z, Li S, Fang F. et al. MicroRNA let-7c inhibits migration and invasion of human non-small cell lung cancer by targeting ITGB3 and MAP4K3. Cancer Lett. 2014;342:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen QY, Jiao DM, Wu YQ, Chen J, Wang J, Tang XL. et al. MiR-206 inhibits HGF-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer via c-Met /PI3k/Akt/mTOR pathway. Oncotarget. 2016;7:18247–61. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall CL, Zhang H, Baile S, Ljungman M, Kuhstoss S, Keller ET. p21CIP-1/WAF-1 induction is required to inhibit prostate cancer growth elicited by deficient expression of the Wnt inhibitor Dickkopf-1. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9916–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fulciniti M, Tassone P, Hideshima T, Vallet S, Nanjappa P, Ettenberg SA. et al. Anti-DKK1 mAb (BHQ880) as a potential therapeutic agent for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2009;114:371–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-191577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito M, Shiraishi K, Kunitoh H, Takenoshita S, Yokota J, Kohno T. Gene aberrations for precision medicine against lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:713–20. doi: 10.1111/cas.12941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeon HM, Lee J. MET: roles in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:5. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.12.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu FF, Zhang Y, Liu YY, Hong XH, Liang JY, Tong F. et al. Lung adenocarcinoma harboring concomitant SPTBN1-ALK fusion, c-Met overexpression, and HER-2 amplification with inherent resistance to crizotinib, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:66. doi: 10.1186/s13045-016-0296-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura Y, Niki T, Goto A, Morikawa T, Miyazawa K, Nakajima J. et al. c-Met activation in lung adenocarcinoma tissues: an immunohistochemical analysis. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1006–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia N, An J, Jiang QQ, Li M, Tan J, Hu CP. Analysis of EGFR, EML4-ALK, KRAS, and c-MET mutations in Chinese lung adenocarcinoma patients. Exp Lung Res. 2013;39:328–35. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2013.819535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schildhaus HU, Schultheis AM, Ruschoff J, Binot E, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Fassunke J. et al. MET amplification status in therapy-naive adeno- and squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:907–15. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sattler M, Salgia R. c-Met and hepatocyte growth factor: potential as novel targets in cancer therapy. Current oncology reports. 2007;9:102–8. doi: 10.1007/s11912-007-0005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W, Gherardi E, Vande Woude GF. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:915–25. doi: 10.1038/nrm1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Syed ZA, Yin W, Hughes K, Gill JN, Shi R, Clifford JL. HGF/c-met/Stat3 signaling during skin tumor cell invasion: indications for a positive feedback loop. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller M, Morotti A, Ponzetto C. Activation of NF-kappaB is essential for hepatocyte growth factor-mediated proliferation and tubulogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1060–72. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1060-1072.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002;298:1911–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glinka A, Wu W, Delius H, Monaghan AP, Blumenstock C, Niehrs C. Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature. 1998;391:357–62. doi: 10.1038/34848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimura H, Fumoto K, Shojima K, Nojima S, Osugi Y, Tomihara H. et al. CKAP4 is a Dickkopf1 receptor and is involved in tumor progression. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:2689–705. doi: 10.1172/JCI84658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chi Y, Jin Q, Liu X, Xu L, He X, Shen Y. et al. miR-203 inhibits cell proliferation, invasion, and migration of non-small-cell lung cancer by downregulating RGS17. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:2366–72. doi: 10.1111/cas.13401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu H, Xu Z, Li C, Xu C, Lei Z, Zhang HT. et al. MiR-145 and miR-203 represses TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasion by inhibiting SMAD3 in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Lung Cancer. 2016;97:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kikuchi A, Fumoto K, Kimura H. The Dickkopf1-cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 axis creates a novel signalling pathway and may represent a molecular target for cancer therapy. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:4651–65. doi: 10.1111/bph.13863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sattler M, Salgia R. The MET axis as a therapeutic target. Update on cancer therapeutics. 2009;3:109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.uct.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.