Abstract

This study tested whether the strength of the mediational pathway involving interparental conflict, adolescent emotional insecurity, and their psychological problems depended on the quality of their sibling relationships. Using a multi-method approach, 236 adolescents (Mean age = 12.6 years) and their parents participated in three annual measurement occasions. Tests of moderated mediation revealed that indirect paths among interparental conflict, insecurity, and psychological problems were significant for teens with low, but not high, quality bonds with siblings. High quality (i.e., strong) sibling relationships conferred protection by neutralizing interparental conflict as a precursor of increases in adolescent insecurity. Results did not vary as a function of the valence of sibling relationship properties, adolescent sex, or gender and age compositions of the dyad.

Children who witness recurrent destructive interparental conflict characterized by hostility, negative escalation, and difficulties resolving disagreements are at increased risk for experiencing externalizing, internalizing, and attention difficulties (Jouriles, McDonald, & Kouros, 2016). However, it is also the case that most children exposed to high levels of acrimony between parents do not experience clinically significant levels of psychopathology at any one time (Cummings & Davies, 2011; Ghazarian & Buehler, 2010). Therefore, documentation of the scope and magnitude of risk associated with interparental conflict has increasingly been supplanted by a second generation of research designed to identify the sources of resilience for children exposed to discord between parents (Cummings & Davies, 2011; Grych & Fincham, 2001). Despite evidence indicating that children’s vulnerability to interparental conflict may be buffered by several family characteristics (e.g., parenting, parent-child attachment, family cohesion), little is known about the potential operation of sibling relationship processes as protective factors in the face of discord between parents (Davies & Cummings, 2006). To address this significant gap in the literature, the goal of the present investigation was to examine sibling relationship quality as a protective factor that interrupts the pathogenic processes underpinning children’s vulnerability to interparental conflict.

Sibling relationships are an important family context for child development (Feinberg, Solmeyer, & McHale, 2012). Not only do the vast majority of children grow up with a sibling, but they also spend more time interacting with siblings than they do with any other family member (Buist, Dekovic, & Prinzie, 2013). Moreover, higher sibling relationship quality characterized by warmth, closeness, problem-solving, and low levels of antagonism, conflict, and detachment are predictors of better psychological adjustment in childhood and adolescence (e.g., Buist et al., 2013; Dirks, Pesram, Recchia, & Howe, 2015; McHale, Updegraff, & Whiteman, 2013). In highlighting the possibility that siblings may buffer children from the risk posed by interparental conflict, other research indicates that siblings can serve as sources of protection, support, and companionship under stressful conditions. For example, empirical findings indicate that most children report seeking contact with a sibling as a means of coping with interparental quarrels (Jenkins, Smith, & Graham, 1989). Likewise, another study identified sibling affection as a protective factor in the prospective association between stressful life events and children’s emotional problems (Gass, Jenkins, & Dunn, 2007).

Despite some preliminary support for the role of sibling characteristics as protective factors, research directly examining sibling relationship quality as a moderator of associations between interparental conflict and children’s psychological functioning is limited. To our knowledge, only two cross-sectional studies have examined the multiplicative interplay between interparental conflict and sibling relationships (Grych, Raynor, & Fosco, 2004; Jenkins & Smith, 1990). Moreover, these investigations yielded inconsistent support for the moderating role of sibling relationship quality. Whereas one study indicated that the link between interparental discord and child psychological problems was reduced for children who experienced good sibling relationships (Jenkins & Smith, 1990), another investigation failed to identify any significant interactions between interparental conflict and sibling relationship quality in predicting adolescent psychological adjustment (Grych et al., 2004). Although these earlier studies provide a valuable first step in integrating the study of interparental conflict and sibling relationships, the exclusive use of cross-sectional designs may have diluted the sensitivity to identify sibling relationships as moderators of the cascading sequelae of interparental conflict over time. Family process models share the premise that the stressfulness of witnessing interparental conflict gradually increases children’s vulnerability to psychopathology by progressively altering how they respond to subsequent difficulties between parents (e.g., Davies, Martin, & Sturge-Apple, 2016; Grych & Fincham, 1990; Repetti, Robles, & Reynolds, 2011).

Accordingly, our study is designed to provide a first test of whether mediational pathways involving interparental conflict, children’s processing and reactivity to parental difficulties, and their psychological problems vary as a function of sibling relationship quality. Guided by emotional security theory (EST; Davies & Cummings, 1994), we specifically examine whether sibling relationship processes moderate the mediational role of children’s emotional insecurity in the prospective association between interparental conflict and children’s psychopathology. As a prevailing explanatory model, EST proposes that children’s insecurity in the interparental relationship mediates the risk interparental conflict poses for them (Davies & Cummings, 1994). That is, recurring exposure to angry, escalating, and unresolved conflicts between parents is proposed to increase children’s psychological problems by directly sensitizing their reactivity to threat in the interparental relationship.

In the first link in the mediational chain, the emotionally arousing and threatening nature of repeatedly observing interparental conflict is hypothesized to progressively undermine children’s goal of preserving a sense of safety and security in subsequent interparental interactions. Signs of insecurity are manifested in three domains of children’s responding to interparental conflict: (a) intense, prolonged fear and distress reactions; (b) active attempts to regulate exposure to parental interactions through involvement in and avoidance of the conflicts; and (c) negative internal representations of the implications conflict has for themselves and their family. In the second link in the mediational chain, difficulties preserving emotional security are proposed to intensify and proliferate to increase children’s vulnerability to poor adjustment and psychopathology. Supporting the value of EST, longitudinal studies have consistently supported the mediational role of children’s insecurity in prospective associations between interparental conflict and a wide array of psychological symptoms characterized by internalizing, externalizing, and attention problems (see Cummings & Miller-Graff, 2015).

In integrating protective models of sibling relationships with EST, having a supportive relationship with a sibling may specifically offset the unfolding vulnerability conferred by interparental conflict at two developmental points in the mediational cascade (Conger & Conger, 2002; Cummings & Davies, 2011; McHale, Updegraff, & Whiteman, 2012). In the first part of the proposed mediational process of EST, sibling relationships may impede the process whereby interparental conflict sensitizes children to experience insecurity in the face of interparental conflict. For example, siblings have long been regarded as having the capacity to serve as protective and supportive figures to children in ways that are similar to the roles played by attachment figures (Dunn & Kendrick, 1982; McHale et al., 2012). In support of this thesis, research has shown that siblings effectively reduced the distress of young children during stressful separation and reunion episodes in the Strange Situation (Stewart, 1983; Stewart & Marvin, 1984). Likewise, observational findings indicate that sibling positive affect and prosocial behavior increase during and following exposure to anger between adults (Cummings & Smith, 1993). Taken together, it is possible that siblings may attempt to buffer each other from the stressfulness of witnessing interparental conflict, thereby reducing signs of insecurity in the form of lower levels of emotional reactivity, avoidance, involvement, and negative representations in the face of subsequent disagreements between parents.

At the latter part of the mediational cascade, high quality sibling relationships might reduce or offset the tendency for children’s prolonged concerns about security in the interparental relationship to proliferate into broader psychological problems. According to EST (Davies, Martin, & Sturge-Apple 2016), children’s insecurity in the interparental relationship reflects the heightened saliency of processing and defending against social threat over approach-oriented goals that facilitate the intrinsic motivation to acquire social skills (e.g., cooperation, mutuality, reciprocal altruism in peer relationships), caregiving capacities (e.g., empathy, sympathy, prosocial behavior, perspective-taking), and mastery of the physical world (e.g., problem-solving, autonomous learning). Difficulties in achieving these goals, in turn, increase children’s risk for psychological difficulties. Conceptualizations of the developmental functions of sibling relationships support the notion that healthy sibling processes may counteract this pathogenic cascade. For example, strong sibling bonds may increase the resilience of insecure children by serving as role models, mentors, and guides to effectively negotiating approach-oriented challenges in interpersonal (e.g., peer) and exploratory (e.g., academic) domains (Jacobs & Sillars, 2012; Kramer & Conger, 2009; McHale et al., 2012).

To test these theoretically guided hypotheses, we examined whether sibling relationship quality moderated the mediational cascade of interparental conflict, children’s emotional insecurity, and their psychological problems during early adolescence. We focused on early adolescence because it is a key developmental period for understanding the downstream implications of the interplay between interparental processes and sibling relationship qualities. According to developmental models (Cummings & Davies, 2011; Grych, Raynor, & Fosco, 2004), early adolescence ushers in emerging patterns of functioning that may sensitize children to interparental conflict. Relative to younger children, adolescent concerns about security in high conflict homes may be amplified by their increased sensitivity to adult problems, longer histories of exposure to interparental conflict, and stronger dispositions to mediate conflict (Cummings & Davies, 2011; Fosco & Grych, 2010; Vu, Jouriles, McDonald, & Rosenfield, 2016). Consistent with this premise, the prospective relation between interparental conflict and emotional insecurity was significantly stronger for adolescents than it was for preadolescent children (Cummings, Schermerhorn, Davies, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2006). By the same token, sibling relationships are highly salient socialization contexts for children during early adolescence. Within this developmental period, increases in both positive (e.g., nurturance, attachment) and negative (e.g., antagonism, conflict) characteristics in these relationships are highly prevalent as adolescents seek to negotiate a balance between autonomy and relatedness within the changing parameters of their sibling relationships (Buhrmester & Furman, 1990; Campione-Barr & Smetana, 2010). Moreover, individual differences in the quality of sibling relationships during adolescence are potent predictors of subsequent changes in psychological adjustment even after controlling for a wide range of family and child covariates (e.g., Solmeyer, McHale, & Crouter, 2014; Whiteman, Solmeyer, & McHale, 2015).

In summary, the current investigation is designed to break new ground by examining sibling relationship quality as a protective factor in each of the links in the mediational pathway involving adolescents’ experiences with interparental conflict, emotional insecurity, and psychological problems. As the first prospective analysis of the protective role of sibling relationship quality in models of interparental conflict, we employed a multi-method (i.e., observational, semi-structured interview, and surveys), longitudinal design with three annual measurement occasions to authoritatively test our hypotheses. Following rigorous quantitative guidelines for examining moderated mediation (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Maxwell & Cole, 2007), we instituted repeated measures of adolescent insecurity and psychological problems to permit a full prospective analysis of whether change at each part of the mediational chain was moderated by sibling relationship quality. To complement the predominant reliance on questionnaire assessments of sibling relationships, we utilized rich, coded narrative descriptions of the quality of children’s relationships with their closest-aged sibling from a semi-structured interview with mothers. Consistent with previous research (Buist, 2010; Richmond, Stocker, & Rienks, 2005; Volling & Blandon, 2005), our assessment of sibling relationship quality consisted of a broad, parsimonious composite indexing both higher levels of positive (i.e., warmth, problem-solving, conflict resolution) attributes and lower levels of negative (i.e., destructive conflict, disengagement) characteristics in the dyad. However, some research suggests that constructive (e.g., warmth) and destructive (e.g., conflict) relationship characteristics may differ in their developmental implications during adolescence (e.g., Buist et al., 2013). Therefore, we conducted follow up analyses to examine whether any significant protective effects of sibling relationship quality in the mediational cascade are primarily attributable to adolescents’ exposure to positive relational characteristics, their diminished experiences with negative dyadic processes, or both.

Moreover, given that the nature and sequelae of sibling relationship qualities may vary across the sex of the adolescent, the sex composition of a sibling dyad, the developmental status of siblings (i.e., older versus younger), and the constellation of age and sex characteristics of the pairs, we also examine whether any identified protective effects of sibling relationship quality are moderated by these structural characteristics. These characteristics were selected based on some, albeit inconsistent, empirical and theoretical support for the possibility that the developmental meaning and consequences of the sibling relationship quality may vary by gender, age, and the combination of gender and age (e.g., Buist, 2010; Buist et al., 2013; Solmeyer et al., 2014). For example, Buist (2010) found that sibling relationship quality was only a significant predictor of greater delinquency for older sister/younger brother pairs. Likewise, some conceptual models (e.g., social learning theory) have proposed that the impact of sibling relationship quality on children’s psychological functioning will be greatest for younger and same-sex sibling dyads, given the greater salience of vicarious learning (Whiteman et al., 2011). Finally, to ensure that any significant moderated-mediation effects were not simply byproducts of the operation of demographic factors, we also included several family socioeconomic (e.g., parent educational attainment, household income) and structural (e.g., genetic relatedness of siblings) characteristics as covariates in analyses (e.g., Buist et al., 2013; Davies, Martin, Coe, & Cummings, 2016).

METHOD

Participants

Data for this study were drawn from a longitudinal project on family relationship processes and adolescent development. Participants in the larger study consisted of 280 families with adolescents who were recruited through local school districts and community centers in a moderately sized metropolitan area in the Northeastern US and a small city in the Midwestern US. Families were only included in this paper if: (1) mothers, fathers, and adolescents had regular contact with each other (defined as maintaining contact for an average of 2 to 3 days per week during the year); and (2) adolescents had at least one sibling who was not a twin. These inclusionary criteria resulted in the exclusion of 44 families (i.e., 17 failed to meet the first condition; 27 failed to meet the second requirement), yielding a sample of 236 families.

Adolescents were in seventh grade at Wave 1 and, on average, 12.59 years (SD = .57; range 11 to 14). Girls comprised 49% of the sample. Median household income of the families was between $55,000 and $74,999 per year. Median education level of mothers and fathers was between some college education and an Associate’s degree. Most parents (i.e., 89%) were married at the outset of the study. For racial background, 74% of adolescents identified as White, followed by smaller percentages of African American (17%), multi-racial (8%), and other races (1%). In terms of US ethnicity designations, 6% of youth identified as Latino. Adolescents lived with their biological mother in most cases (93%), with the remainder living with an adoptive or stepmother (4%), or a female guardian (3%). Children also lived with their biological father in most cases (79%), with the remainder of the sample living with either an adoptive or stepfather (16%), or a male guardian (5%). The longitudinal design of the study consisted of three annual measurement occasions. Data were collected between 2007 and 2011. Retention rates were 93% across each of the two contiguous waves of data collection, with 85% of the families completing all three waves of data collection.

For adolescents with more than one sibling, the sibling closest in age to the adolescent was selected to assess sibling relationship quality. The mean age of siblings was 12.63 years (SD = 3.87, range = 2–27 years old). Despite the wide age range of the siblings, 87% of adolescents and their siblings were no more than 5 years apart, with the average span being 3.32 years (SD = 2.29). The developmental status of target adolescents in relation to their siblings was relatively evenly distributed, with target adolescents being: (1) older than siblings in 53% of the dyads, and (2) younger than siblings in 47% of the dyads. Sibling dyads were divided fairly evenly with regard to distribution of child sex: 52% were same-sex dyads (26% brothers; 26% sisters) and 48% were opposite-sex pairs (25% target brother-sibling sister; 23% target sister-sibling brother). Finally, within the subsample of opposite-sex pairs of siblings, 56% were older brother/younger sister dyads, and 44% were older sister/younger brother pairs. Most dyads were full biological siblings (88%), followed by smaller percentages of half-siblings (6%), step-siblings (2%), adopted (2%), and other (2%). Most adolescents lived with the target sibling (90%).

Procedures and Measures

At each of three waves of data collection, families visited the laboratory twice at one of two data collection sites. Laboratories at each site were designed to be comparable to each other in size and quality and included: (a) an observation room that was designed to resemble a living room and equipped with audiovisual equipment to capture family interactions, and (b) interview rooms for completing confidential interview and survey measures. Teachers also completed survey measures of adolescent psychological adjustment at the first and third waves. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each research site. Families and teachers were compensated monetarily for their participation. Families were paid between $125 and $155 per visit depending on the wave. Teachers were paid $25 at each wave.

Interparental conflict

At Wave 1, mothers and fathers participated in an interparental interaction task in which they discussed two common, intense interparental disagreements that they viewed as problematic in their relationship. Following similar procedures in previous research (Du Rocher Schudlich, Papp, & Cummings, 2004), each parent was asked to independently select the three most problematic topics of disagreement in their relationship that they felt comfortable discussing. Couples were provided with a list of common disagreements to use as a guide in the selection process. After this procedure, partners conferred to select two topics from their lists that they both felt comfortable discussing. The couples subsequently discussed each topic for seven minutes while they were alone in the laboratory room. Trained coders rated videotaped records of the interparental interactions using five dimensional scales from the System for Coding Interactions in Dyads (SCID; Malik & Lindahl, 2004). Raters separately coded mothers and fathers for: Verbal Aggression, defined as the level of hostile or aggressive behaviors and verbalizations displayed by each individual; and Poor Problem Solving (reverse score of the SCID Problem Solving Communication code), defined as uncooperative behaviors that hinder progress in addressing the conflict. At a dyadic level of analysis, coders also rated Negative Escalation, reflecting the degree to which the couple as a unit escalates expressions of anger, hostility, and negativity. Each code is rated on a five-point scale ranging from: 1 (very low) to 5 (high). Interrater reliability, based on the intraclass correlation coefficients of coders’ independent ratings on 19% of the interactions, ranged from .72 to .90 across five codes (Mean ICC = .83). The five observational ratings were summed together to form a single composite of interparental conflict (α = .85).

Sibling relationship quality

At Wave 1, a trained experimenter administered the Sibling Interview for Mothers (SIM), a semi-structured interview with the mother, designed to assess the quality of sibling relationships in childhood (Bascoe, Davies, & Cummings, 2012). The timing of our Wave 1 sibling measure was guided by quantitative calls in the literature to obtain moderator assessments that temporally correspond with or precede the proposed predictors (i.e., Wave 1 interparental conflict and Wave 2 adolescent emotional insecurity; Goodnight, Bates, Newman, Dodge, & Pettit, 2006). We followed conventional procedures for assessing sibling relationships in this study by focusing the interview on the quality of adolescents’ relationships with their closest aged sibling (e.g., Kim, McHale, Crouter, & Osgood, 2007; Volling & Blandon, 2005; Whiteman, et al., 2015). The multi-component interview contains questions on the social and emotional characteristics of the target sibling dyad. In the first part of the interview, mothers rated the level of closeness in the sibling dyad on a 5-point scale (1 = not close at all; 5 = extremely close). In the middle portion of the interview, mothers responded to more specific questions about the nature of sibling interactions (e.g., “What does a typical interaction between them look like?” “What sorts of things do they typically talk about when they’re together?”). In the concluding section of the interview, the focus was on understanding the frequency and nature of challenges and disagreements in the sibling relationship. Mothers first provided ratings of conflict frequency on a seven-point scale (0 = never; 7 = several times a day). Ratings were followed by specific questions designed to characterize key parameters of conflicts, including onset (e.g., “How do conflicts typically start?”), course (e.g., “Describe what happens next.” “Is there anything else that typically happens before the conflict ends?”), and endings (e.g., “How do conflicts typically end?”). Additional probes were used by interviewers to clarify vague or underdeveloped responses.

Trained coders rated audiotaped records of the interview using five dimensional scales, each ranging from 0 (None) to 3 (High). Three constructive features of sibling relationship quality consisted of: (1) Warmth, defined by the degree of closeness and intimacy in the sibling dyad (e.g., verbal expressions of fondness, physical affection, conversations about intimate issues, sharing of common interests, prosocial behavior, plans to maintain and strengthen the relationship); (2) Conflict Resolution, characterized by resolving disagreements in ways that allow siblings to quickly resume friendly interactions; and (3) Problem-Solving, as reflected in the ability to utilize constructive conflict tactics that are likely to be effective in resolving differences (e.g., efforts to understand the other’s perspective, compromising, apologizing, and generating constructive solutions). Two destructive relationship dimensions included: (1) Destructive Conflict, assessing the degree to which the sibling relationship is characterized by frequent, escalating, and intense hostility; and (2) Disengagement, defined by high levels of indifference, emotional detachment, and unresponsiveness in the dyad. Interrater reliability, which reflected intraclass correlation coefficients calculated from coders’ independent ratings of 21% of the interviews, were as follows: Warmth = .86; Conflict Resolution = .88, Problem-Solving = .67; Destructive Conflict = .92; and Disengagement = .83. To determine the factor structure of the sibling measures, we submitted the five codes to a principal components analysis with varimax rotation. Analysis of the eigenvalues (i.e., ≥ 1) and scree plot of the factors supported a one-factor solution. Therefore, a single, parsimonious composite of sibling relationship quality was created by summing the five sibling ratings after reverse-scoring Disengagement and Conflict so that higher scores reflected higher quality sibling relationships (α = .78).

Adolescent insecurity in the interparental relationship

Adolescents completed five subscales of the Security in Interparental Subsystem (SIS) Scales to assess their emotional insecurity at Waves 1 and 2 (Davies, Forman, Rasi, & Stevens, 2002). First, the SIS Emotional Reactivity subscale consists of nine items that assess multiple, prolonged experiences of fear and distress in response to conflict (e.g., “When my parents argue, I feel scared.”). Second, the SIS Avoidance subscale indexes adolescent endorsement of strategies to reduce their exposure to interparental conflict (e.g., “I keep really still, almost as if I was frozen.”). Third, the SIS Involvement subscale is designed to assess children’s efforts to directly regulate and intervene in the conflicts between their parents (6 items; e.g., “I try to solve the problem for them.”). Finally, consistent with previous studies (e.g., Davies, Harold, Goeke-Morey, Cummings, & Shelton, 2002), we utilized the Negative Representations scale consisting of the sum of two subscales: the SIS Destructive Family Representations, which assesses appraisals of the deleterious consequences of interparental conflict for the family (4 items; e.g., “When my parents have an argument, I wonder if they will divorce or separate.”); and the SIS Conflict Spillover Representations, defined as children’s evaluation that interparental conflict proliferates to negatively impact their welfare and relations with parents (4 items; e.g., “When my parents have an argument, I feel like they are upset at me.”). Previous research has supported the validity of this measurement approach (Davies et al., 2002). Internal consistencies for Waves 1 and 2 respectively were .89 and .88 for Emotional Reactivity, .82 and .85 for Avoidance, .73 and .77 for Involvement, and .87 and .87 for Insecure Representations.

Adolescent psychological problems

To obtain a comprehensive assessment of adolescent psychological problems at Waves 1 and 3, mothers, teens, and teachers each completed assessments of adolescent problems across three domains: externalizing, internalizing, and attentional difficulties. Mothers completed three scales from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach), including: (1) the Externalizing Symptoms Scale (e.g., “lying or cheating,” “gets in many fights”); (2) the Internalizing Symptoms Scale, consisting of the Anxious/Depressed and Withdrawn subscales (e.g., “fears certain animals, situations, or places,” “unhappy, sad, or depressed”); and (3) the Attention Problems scale (e.g., “can’t sit still, restless, or hyperactive,” “can’t concentrate, can’t pay attention for long,”). Previous studies have provided consistent evidence for the reliability and convergent and discriminant validity of these three CBCL scales (e.g., Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2003). Alpha coefficients for the three measures across the two waves ranged from .74 to .90 (Mean α = .82 at Wave 1 and .83 and Wave 3). To form a parsimonious indicator of maternal reports of adolescent psychological problems, the three measures were standardized and averaged together at each of the waves. Internal consistency coefficients of the scales in the composites were .71 at Wave 1 and .75 at Wave 3.

To obtain comparable measures of externalizing and attentional symptoms, adolescents completed the Conduct Problems (five items; e.g., “I fight a lot,” “I am often accused of lying or cheating”) and Hyperactivity/Inattention (five items; e.g., “I am restless, I cannot stay still for long,” “I am easily distracted, I find it difficult to concentrate”) subscales from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman & Scott, 1999). For the assessment of internalizing problems, children completed the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), a 20-item measure indexing emotional problems in the form of both depressive and anxiety symptoms (e.g., “I felt fearful,” “I felt sad”). Reliability and validity are well-established for both the SDQ (e.g., Goodman, 2001) and the CES-D (e.g., Crockett, Randall, Shen, Russell, & Driscoll, 2005). Alpha coefficients for the four scales at each of the waves ranged from .64 to .89 (Mean α = .74 at Wave 1 and .76 at Wave 3). The three scales were standardized and averaged together to obtain a single child report measure of their psychological difficulties at Waves 1 (scale-level α = .69) and 3 (scale-level α = .69).

The final indicator was comprised of three teacher report measures within three domains of adolescent psychological problems. Teachers completed the Conduct Problems (“Often fights with other youth or bullies them,” “Often lies and cheats”), Hyperactivity/Inattention (e.g., “Restless, overactive, cannot stay still for long,” “Easily distracted, concentration wanders”), and Emotional Symptoms (e.g., “Many fears, easily scared,” “Often unhappy, depressed, or tearful”) subscales from the teacher version of the SDQ (Goodman, 2001). Internal consistencies for each of the five-item scales ranged from .68 to .82 (Mean α = .75 at Wave 1 and Wave 3). Consistent with the child- and parent-report measures, we created a single composite of teacher-reported adolescent problems at each wave. The three scales were standardized and averaged together at each wave. Scale-level alpha coefficients for each composite were .66 and .65 at Waves 1 and 3, respectively.

Demographic covariates

Seven covariates were derived from parent reports of demographic characteristics at Wave 1 including: (1) sex of the target adolescent (1 = boy; 2 = girl); (2) sex of the target sibling (1 = boy; 2 = girl); (3) Wave 1 parental educational level, calculated as the average of maternal and paternal years of education; (4) total annual household income based on a 13-point ordinal scale ranging from 1 (less than $6,000) to 13 ($125,000 or more); (5) co-residency status of siblings (i.e., living together versus living part); (6) age difference between target adolescent and sibling, and (7) genetic relationship between siblings (i.e., 1 = step, adopted, or other; 2 = half sibling; 3 = biological sibling).

RESULTS

Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 provides the means, standard deviations, and correlations for the variables used in the primary analyses. As denoted by the bolded coefficients in the table, correlations among the indicators of the higher order constructs of adolescent emotional insecurity and psychological problems within each wave were generally moderate to strong in magnitude (Mean r = .45). Prior to conducting our primary analyses, we also examined whether rates of missingness in our data set were associated with any of the 16 primary variables, seven possible covariates, and nine additional sociodemographic variables (e.g., parental age, marital status). Two of the 32 analyses were significant, with greater rates of missingness associated with higher levels of interparental conflict (r = .17, p = .01) and negative child representations of interparental conflict (r = .14, p = .03) at Wave 1. Full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) methods for estimating data successfully minimize bias in regression and standard error estimates for all types of missing data (i.e., MCAR, MAR, NMAR) when the amount of missing data is under 20% (Schlomer, Bauman, & Card, 2010). Therefore, given that data in our sample were missing for 6% of the values, we used FIML to retain the full sample for primary analyses (Enders, 2001). We tested the moderating role of sibling relationship quality in mediational associations involving interparental conflict and adolescent emotional insecurity and psychological problems using a two-stage structural equation modeling approach with Amos 25.0 software (Arbuckle, 2017).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among the Primary Variables in the Study.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 Family Predictors | |||||||||||||||||

| 1. Interparental Conflict | 9.60 | 3.62 | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Sibling Relationship Quality | 8.63 | 3.00 | −.07 | -- | |||||||||||||

| Wave 1 Child Emotional Insecurity | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. Emotional Reactivity | 14.89 | 5.79 | .10 | −.10 | -- | ||||||||||||

| 4. Negative Representations | 11.01 | 4.27 | .16* | −.12 | .71* | -- | |||||||||||

| 5. Avoidance | 15.35 | 5.37 | .09 | −.09 | .63* | .50* | -- | ||||||||||

| 6. Involvement | 12.65 | 3.98 | .05 | .07 | .32* | .31* | .31* | -- | |||||||||

| Wave 2 Child Emotional Insecurity | |||||||||||||||||

| 7. Emotional Reactivity | 13.97 | 5.39 | .23* | −.11 | .49* | .48* | .36* | .29* | -- | ||||||||

| 8. Negative Representations | 10.60 | 4.11 | .17* | −.07 | .29* | .38* | .14* | .07 | .70* | -- | |||||||

| 9. Avoidance | 14.78 | 5.32 | .14* | −.03 | .42* | .36* | .44* | .22* | .69* | .52* | -- | ||||||

| 10. Involvement | 12.09 | 4.12 | .13 | .04 | .34* | .28* | .22* | .57* | .46* | .33* | .48* | -- | |||||

| Wave 2 Child Psychological Problems | |||||||||||||||||

| 11. Mother Report | 0.01 | 0.80 | −.01 | −.28* | .13 | .11 | .02 | −.17* | .06 | .09 | .01 | −.15* | -- | ||||

| 12. Teacher Report | −0.01 | 0.76 | .28* | −.15* | .16* | .27* | .05 | .01 | .03 | .04 | −.04 | −.14 | .36* | ||||

| 13. Child Report | 0.02 | 0.81 | .16* | −.13 | .33* | .37* | .27* | −.03 | .18* | .22* | .22* | .02 | .38* | .32* | -- | ||

| Wave 3 Child Psychological Problems | |||||||||||||||||

| 14. Mother Report | 0.00 | 0.80 | .12 | −.24* | .13 | .24* | .05 | −.08 | .18* | .18* | .05 | −.08 | .71* | .32* | .36* | -- | |

| 15. Teacher Report | −0.01 | 0.76 | .10 | −.03 | .16* | .27* | .06 | .11 | .18* | .16* | .04 | −.07 | .27* | .46* | .28* | .35* | -- |

| 16. Child Report | 0.00 | 0.75 | .10 | −.11 | .27* | .32* | .22* | .07 | .23* | .21* | .24* | .03 | .25* | .11* | .47* | .42* | .29* |

Note.

p < .05.

Correlations among indicators of latent constructs are in boldface.

Primary Analyses: Sibling Relationship Quality as a Moderator of Security Pathways

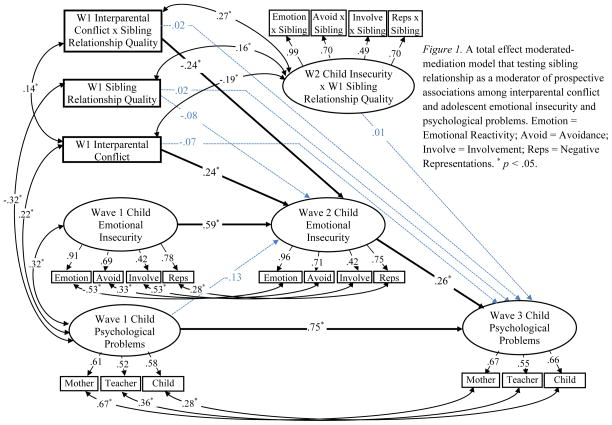

To test whether the mediational pathways involving interparental conflict and adolescent emotional insecurity and psychological problems varied as a function of sibling relationship quality, we specified a total effect moderated-mediation model that simultaneously specifies sibling relationship quality as a moderator of associations between: (1) Wave 1 interparental conflict and Wave 3 adolescent psychological problems; (2) Wave 1 interparental conflict and Wave 2 adolescent emotional insecurity; and (3) Wave 2 adolescent emotional insecurity and their psychological problems (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). To test the first two components of the model, we examined whether the cross-product of the centered interparental conflict and sibling relationship quality variables at Wave 1 predicted adolescent insecurity in the interparental relationship at Wave 2 and psychological problems at Wave 3 after controlling for interparental conflict, sibling relationship quality, and comparable measures of insecurity and psychological difficulties at Wave 1. As the proposed mediator, adolescent insecurity at Wave 2, in turn, was specified as a predictor of their Wave 3 psychological problems. In the final part of the moderation analyses, we specified the cross products of each of the four emotional insecurity indicators at Wave 2 with the Wave 1 sibling relationship composite as manifest indicators of a latent variable reflecting the multiplicative interaction between sibling relationship quality and emotional insecurity (see Marsh, Wen, & Hau, 2004). All the predictors were centered prior to the creation of the interaction term. The latent interaction term, in turn, was examined as a predictor of Wave 3 psychological problems.

Multiple measures of adolescent emotional insecurity and multiple informant reports of their psychological problems were specified as indicators of latent constructs. To maximize measurement equivalence, loadings of each of the indicators of insecurity and psychological problems were constrained to be equal across measurement occasions. Correlations were also specified among all Wave 1 variables in the model and between residual errors of the same manifest indicators of adolescent emotional insecurity and psychological problems across time to account for stability in measurement error for each indicator. However, for clarity of presentation, only significant correlations are depicted in the figure. In preliminary model estimations, the seven demographic covariates (i.e., sex of target adolescent, sex of target sibling, parent education level, family income, co-residency status of siblings, age difference between siblings, genetic relationship between siblings) were also initially examined as predictors of the two endogenous (i.e., adolescent insecurity at Wave 2 and their psychological problems at Wave 3) variables. However, because none of the covariates significantly predicted the endogenous variables in the model, they were dropped from the analyses to maximize statistical parsimony.

The resulting moderated mediational model, which is depicted in Figure 1, provided an adequate fit with the data, χ2 (88, N = 240) = 289.92, p < .001, RMSEA = .06, CFI = .92, and χ2/df ratio = 1.77. Consistent with previous research on the mediational role of insecurity, interparental conflict at Wave 1 predicted greater adolescent insecurity at Wave 2 even after controlling for adolescent insecurity and psychological problems at Wave 1, β = .24, p < .001. Adolescents’ insecurity in the interparental relationship at Wave 2, in turn, predicted their psychological problems at Wave 3, β = .26, p < .001, with the inclusion of Wave 1 predictors. In contrast, sibling relationship quality at Wave 1 was not significantly associated with adolescent insecurity at Wave 2, β = −.08, p = .22, or their psychological problems at Wave 3, β = .02, p = .80. However, of more direct relevance to our aims, sibling relationship quality evidenced specificity in its role as a moderator. Sibling relationship quality did not moderate associations between: (1) Wave 1 interparental conflict and adolescent psychological problems at Wave 3, β = .02, p = .75; or (2) Wave 2 adolescent emotional insecurity and psychological problems at Wave 3, β = .02, p = .88. However, the interaction between interparental conflict and sibling relationship quality at Wave 1 was a significant predictor of adolescent insecurity at Wave 2, β = −.24, p < .001.

Figure 1.

A total effect moderated-mediation model that testing sibling relationship as a moderator of prospective associations among interparental conflict and adolescent emotional insecurity and psychological problems. Emotion = Emotional Reactivity; Avoid = Avoidance; Involve = Involvement; Reps = Negative Representations. * p < .05.

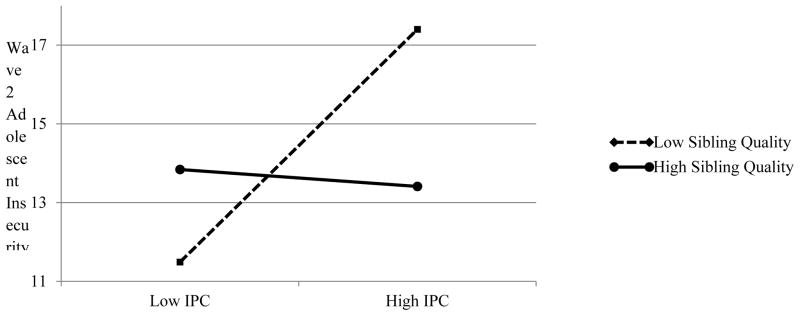

Consistent with statistical recommendations (e.g., Aiken & West, 1991), the moderating role of sibling relationship quality was first clarified by graphically plotting and calculating the simple slopes of interparental conflict at high- (1 SD above the mean) and low- (1 SD below the mean) level values of sibling relationship quality. Low and high values of interparental conflict were respectively demarcated at −1 SD and +1 SD from the mean for the simple slope plots and analyses. The graphical plot of the interaction is depicted in Figure 2. Simple slope analyses revealed that Wave 1 interparental conflict significantly predicted Wave 2 adolescent insecurity at low, b = 3.65, p < .001, but not high, b = −0.26, p = .66, levels of sibling relationship quality. In further illustrating moderated mediation, bootstrapping tests indicated that the indirect path involving interparental conflict, adolescent emotional insecurity, and psychological problems was significantly different from 0 at low (−1 SD), 95% CI [.04 to .16], and medium (0 SD), 95% CI [.02 to .08], but not high (+ 1 SD), 95% CI [−.04 to .02] levels of sibling relationship quality.

Figure 2.

A graphical plot of the interaction between interparental conflict and sibling relationship quality at Wave 1 in predicting subsequent change in adolescent insecurity from Waves 1 to 2.

Follow Up Analyses of Generalizability and Specificity of Sibling Moderating Effects

To further characterize the nature of the interaction, we also conducted two more sets of exploratory tests. First, we examined whether the strength of the sibling relationship quality as a moderator of interparental conflict varied as a function of several structural characteristics of the sibling relationship: (1) developmental status of the target adolescent in the dyad (i.e., older versus younger/same age), (2) sex of the adolescent, (3) the gender composition of the dyad (i.e., same-sex versus opposite-sex), and (4) the configuration of gender and age with each of the four structural characteristics (i.e., brothers, sisters, older sister-younger brother pairs, and older brother-younger sister dyads) successively contrasted with the larger sample of dyads. To increase the parsimony, statistical power, and stability of the analytic solutions, we excluded adolescent psychological problems and the latent interaction between emotional insecurity and sibling relationship quality from the analyses. In the seven resulting models, we specifically examined whether the interaction involving interparental conflict, sibling relationship quality, and each structural characteristic at Wave 1 predicted greater adolescent insecurity at Wave 2 after controlling for Wave 1 insecurity, each of the predictors (i.e., interparental conflict, sibling relationship quality, and the focal structural characteristic), and the two-way interactions among the predictors. The models fit the data well, χ2/df ratio ≤ 1.71, CFI ≥ .95, RMSEA ≤ .05. However, none of the three-way interactions were significant (all ps ≥ .09): interparental conflict x sibling relationship quality x developmental status, β = .11; interparental conflict x sibling relationship quality x sex of adolescent, β = .08, interparental conflict x sibling relationship quality x gender composition of dyad, β = −.10; interparental conflict x sibling relationship quality x brothers, β = .09; interparental conflict x sibling relationship quality x sisters, β = .02; interparental conflict x sibling relationship quality x older sister-younger brother dyads, β = −.07; and interparental conflict x sibling relationship quality x older brother-younger sister dyads, β = −.01.

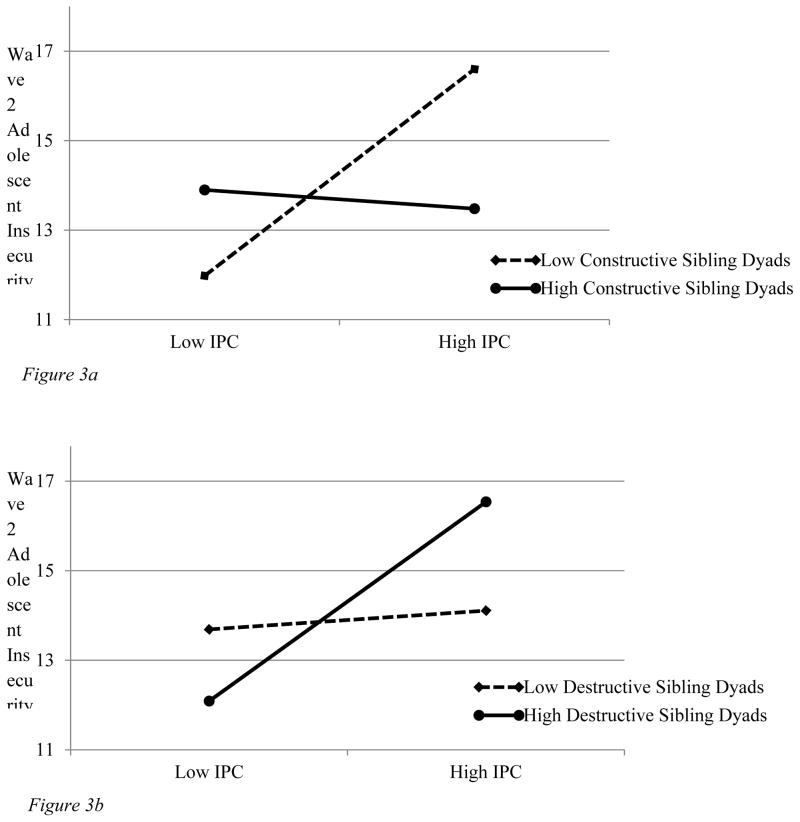

Second, because our sibling relationship quality measure consists of an amalgamation of constructive and destructive dyadic properties, it is unclear whether the source of moderation in sibling relationships is rooted in the presence of greater resources, the relative absence of adversity, or both. Thus, we examined whether constructive (i.e., mean of warmth, problem-solving, and conflict resolution) and destructive (i.e., mean of measures of destructive conflict and disengagement) properties of the sibling relationship moderated the link between interparental conflict and adolescent emotional insecurity in separate SEM models. For the two models, we specifically tested whether the interaction involving interparental conflict and each sibling relationship parameter at Wave 1 predicted greater adolescent insecurity at Wave 2 after controlling for Wave 1 insecurity and each of the centered predictors (i.e., interparental conflict, the specific sibling relationship parameter). The moderating role of the sibling relationship dynamics in the association between interparental conflict and emotional insecurity was significant for both constructive, β = −.21, p < .001; and destructive, β = .14, p = .02, dyadic characteristics. As shown in Figures 3a and 3b, the graphical plots demonstrate that the association between interparental conflict and insecurity is not evident for adolescents with high constructive and low destructive sibling relationships. Simple slope analyses further confirmed the protective nature of these sibling properties. Wave 1 interparental conflict was a significant predictor of Wave 2 insecurity when adolescents experienced low, b = 2.85, p < .001, but not high, b = −0.29, p = .63, levels of constructive sibling relationship processes. Likewise, interparental conflict was only prospectively associated with adolescent insecurity under high, b = 2.59, p < .001, but not low, b = 0.26, p = .67, destructive sibling contexts.

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. A graphical plot of the interaction between interparental conflict and constructive sibling relationship properties at Wave 1 in predicting subsequent change in adolescent insecurity from Waves 1 to 2.

Figure 3b. A graphical plot of the interaction between interparental conflict and destructive sibling relationship quality at Wave 1 in predicting subsequent change in adolescent insecurity from Waves 1 to 2.

DISCUSSION

Toward advancing an understanding of sibling relationship quality as a source of resilience in children exposed to interparental conflict, our paper was designed to be the first study to examine sibling relationship quality as a moderator of the cascading sequelae of interparental conflict over time. Guided by EST (Cummings & Davies, 2011), we tested the hypothesis that having a strong sibling relationship may disrupt a process whereby interparental conflict increases children’s risk for psychopathology by undermining their sense of security in the interparental relationship. Consistent with calls for a third generation of interparental conflict research that integrates the study of moderating conditions with mediating mechanisms (Davies & Cummings, 2006), we used a moderated-mediation approach within a fully-lagged prospective design to examine the protective effects of sibling relationships. In supporting predictions, the findings indicated that youth emotional insecurity mediated associations between interparental conflict and their psychological problems for children with below average or average quality sibling relationships. Conversely, the mediational pathway involving interparental conflict, insecurity, and psychological problems was not significant for teens with strong sibling relationships. Analyses of the locus of the moderating effect further revealed that sibling relationship quality specifically conferred a protective effect at the first part of the risk cascade of insecurity. Sibling relationship quality characterized by warmth, closeness, and effective management of conflict specifically moderated the prospective association between interparental conflict and adolescent emotional insecurity in the interparental relationship. By contrast, in the latter part of the cascade, high quality sibling relations failed to alter the magnitude of adolescent insecurity as an ensuing predictor of their subsequent psychological problems.

In further characterizing the nature of the moderating effect, simple slope and graphical plot analyses indicated that sibling relationship quality altered the link between interparental conflict and subsequent change in adolescent insecurity in a form that corresponded with a “protective-stabilizing” effect (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000). Interparental conflict was unrelated to adolescent insecurity for teens with strong sibling relationships. The “stabilizing” nature of protective effect was specifically evident in the low levels of insecurity exhibited by children with strong sibling relationships across all levels of exposure to interparental conflict. Thus, these findings suggest that having a strong sibling relationship may neutralize or offset adolescent vulnerability to insecurity in the aftermath of exposure to interparental conflict.

Why might sibling relationships offset the tendency for adolescents to become progressively more insecure following exposure to interparental conflict? Building on a common interpretative theme in the sibling literature (e.g., Buist et al., 2013; Jacobs & Sillars, 2012; McHale et al., 2012), having a strong sibling relationship may provide teens with protection and emotional support under adverse social conditions. As subsidiary attachment figures (Stewart & Marvin, 1984; Whiteman, McHale, & Soli, 2011), siblings may inhibit the intensification of children’s insecurity by shielding teens from interparental disagreements or helping them to process and regulate in the aftermath of their exposure to the conflicts. However, our exploratory analyses suggest that accessing the sibling relationship as a source of support and protection may not be the primary process underlying the protective role of a strong sibling relationship. If security in the sibling relationship is the active mechanism of protection (Nixon & Cummings, 1999; Whiteman et al., 2011), then we might expect that compensatory effects would be stronger for adolescents who have older siblings that are more likely to provide, rather than require, caregiving support. However, our additional analyses did not support this pattern. The buffering role of sibling relationship quality, in our sample, did not vary as a function of the developmental spacing (i.e., older vs. younger/same age), gender composition, or age by gender constellation of the dyad.

Although these findings require replication within a larger sample that can more powerfully test the specificity and generalizability of effects across structural and process characteristics of the sibling relationship, it does raise questions about what other processes may be underlying the protective effects of sibling relationships. Siblings are unique by virtue of their capacity to act as both parental figures and peers (Dirks, et al. 2015; McHale et al., 2012). Thus, beyond their possible role as a source of security, sibling relationships may also have important peer-like functions that buffer children from interparental adversity. For example, the shared intimacy and warmth in strong sibling relationships may lay the foundation for a sense of solidarity, and may facilitate disclosure and validation of perceptions of the self and family that ultimately reduce concerns about security and safety (Jacobs & Sillars, 2012; Kramer & Conger, 2009). Likewise, through participation in shared activities (e.g., sports, hobbies) and mutual exposure to new extrafamilial (e.g., peer) settings (Jacobs & Sillars, 2012; McHale et al., 2012), siblings may also divert children’s attention away from the threatening nature of interparental conflicts. Consistent with this possibility, some research shows that the use of distraction predicts subsequent decreases in anxiety and depressive symptoms for children who experience uncontrollable family and interpersonal stressors (see review by Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, 2016).

Although the interpretation up to this point has centered on the protective nature of constructive attributes in sibling relationships, our findings also highlight how lower levels of destructive characteristics in the dyad may also be a source of resilience for children. More specifically, our follow up analyses indicated that lower levels of negative relationship properties conferred the same protective effects as positive sibling relationship processes. Therefore, these findings suggest that having a civil, but not necessarily close, bond with siblings may be sufficient to counteract interparental conflict as a risk factor. Several pathogenic processes have been theorized to develop in the wake of destructive sibling relationships including negative family representations, proclivity to experience emotional distress, and hopelessness (Buist et al, 2013; Dirks et al., 2015). By extension, it is possible that low levels of sibling conflict and disengagement may confer protection by limiting the development of these emotional and appraisal diatheses. That is, lower levels of destructive characteristics in the sibling relationship may keep negative expectations about the interparental relationship from generalizing into broader concerns about the implications parental conflict has for the welfare of the broader family unit and themselves.

Questions remain as to why a comparable protective effect for sibling relationships was not found for the prospective link between adolescent insecurity and psychological problems. Guided by canalization models (e.g., Davies, Martin, & Sturge-Apple, 2016; Sroufe, 1997), one possible explanation is that the increasing stability and potency of insecurity as a precursor of psychopathology becomes so intractable during adolescence that many factors are no longer effective as buffers. Consistent with this interpretation, some empirical evidence suggests that the differential stability of insecurity increases during the early and middle adolescence period (Davies, Martin, Coe, et al., 2016). Moreover, meta-analytic findings indicated that proxies of emotional insecurity (e.g., negative emotional reactivity) more strongly predicted psychological problems for adolescents than for children within the age range of 5 to 19 years (Rhoades, 2008). Alternatively, it is possible that our assessment did not sensitively capture the operative sibling relationship properties that buffer highly insecure adolescents from developing psychological problems. For example, observational and guided learning experiences in strong sibling dyads may be particularly salient in limiting the risk associated with insecurity by providing children with a wider repertoire of coping strategies, corrective feedback on misunderstandings about causes (e.g., blaming self for parental problems) of interparental conflict, and a more nuanced perspective on the differences between interparental problems and the nature of relationships in the broader social world (Kramer & Conger, 2009; Whiteman et al., 2011).

Limitations of our study also warrant discussion for a balanced interpretation of our findings. First, because our community sample consisted of predominantly White families who were, on average, from middle class backgrounds, caution should be exercised in generalizing our findings to other samples. Second, our decision to assess sibling relationship quality through coder ratings of maternal narratives from a semi-structured interview was guided by our emphasis on limiting the operation of common method and informant variance with other key constructs (e.g., adolescent survey reports of insecurity) in our model. However, given that mothers may not be privy to all important properties of the sibling relationship, future research would benefit from incorporating observational and child report measures of sibling dyadic properties. Third, although our multi-dimensional composite of sibling relationship quality was based on previous assessments and recommendations in the literature (e.g., Buist, 2010; Richmond et al., 2005; Volling & Blandon, 2005), the development of new approaches to capturing relationship properties is an important next step in identifying the protective mechanisms conferred by strong sibling bonds. For example, assessing the degree to which sibling relationships fulfill specific functions or provisions (e.g., safe haven, secure base, instrumental support, guided learning, observational learning, affiliative solidarity, distraction from stress) may increase precision in identifying the specific ways sibling relationships may buffer children from the stress of observing interparental conflict (Jacobs & Sillars, 2012; Kramer & Conger, 2009; Whiteman et al., 2011). Finally, our analyses of sibling relationship quality as a moderator of the mediational role of emotional insecurity constitutes a subset of the possible ways sibling bonds may interrupt the pathogenic cascades resulting from exposure to interparental conflict. Thus, examining how sibling relationships might enhance children’s resiliency by diluting the salience of other interparental risk mechanisms (e.g., children’s social-cognitive appraisals, Grych & Fincham, 1990; neurobiological reactivity to stress; El-Sheikh & Erath, 2011) is an important direction for future research.

In conclusion, as the first longitudinal test of the moderating role of sibling relationships in models of interparental conflict, our study was designed to break new ground by examining why strong sibling bonds may serve as a source of resilience for adolescents exposed to elevated interparental conflict. Guided by EST (Davies & Cummings, 1994), we specifically examined whether high quality sibling relationships interrupt the pathogenic cascade whereby interparental conflict poses a risk for adolescent psychological problems by increasing their insecurity in the interparental relationship. Results of moderated mediation tests indicated that the mediational role of emotional insecurity in the link between interparental conflict and adolescent psychological problems was only significant for teens with poor or average sibling relationships. Analyses further revealed that the compensatory effect of having a strong (i.e., high quality) sibling relationship operated by neutralizing the prospective association between interparental conflict and subsequent increases in adolescent insecurity. Although formulating authoritative translational recommendations from our findings is premature at this early stage of research, a potentially hopeful message for practitioners is that strengthening sibling relationships may not only directly foster children’s psychological adjustment, but also offer new approaches to counteracting risks associated with experiencing aggressive, unresolved conflicts between parents. For example, if our findings are replicated, adapting and implementing after school group interventions (e.g., Siblings Are Special Program) may provide more cost-effective and feasible ways of enhancing the resilience of children who witness interparental conflict (Dirks et al., 2015; Feinberg, Solmeyer, Hostetler, Sakuma, Jones, & McHale, 2013).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (2R01 MH57318). We are grateful to the children, parents, school staff who participated in the project and to the project personnel at the University of Rochester and University of Notre Dame.

Contributor Information

Patrick T. Davies, University of Rochester

Lucia Q. Parry, University of Rochester

Sonnette M. Bascoe, University of Rochester

Meredith J. Martin, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

E. Mark Cummings, University of Notre Dame.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist: 4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. DSM-oriented and empirically based approaches to constructing scales from the same item pools. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology. 2003;32(3):328–340. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS (Version 25.0) [Computer Program] Chicago: IBM SPSS; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bascoe SM, Davies PT, Cummings EM. Beyond warmth and conflict: The developmental utility of a boundary conceptualization of sibling relationship processes. Child Development. 2012;83:2121–2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist KL. Sibling relationship quality and adolescent delinquency: A latent growth curve approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:400–410. doi: 10.1037/a0020351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist KL, Deković M, Prinzie P. Sibling relationship quality and psychopathology of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. Perceptions of sibling relationships during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61:1387–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campione-Barr N, Smetana JG. “Who said you could wear my sweater?” Adolescent siblings’ conflicts and associations with relationship quality. Child Development. 2010;81:464–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ. Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:361–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Randall BA, Shen YL, Russell ST, Driscoll AK. Measurement equivalence of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale for Latino and Anglo adolescents: a national study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:47–58. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York: Guilford; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Miller-Graff LE. Emotional security theory: An emerging theoretical model for youths’ psychological and physiological responses across multiple developmental contexts. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2015;24:208–213. doi: 10.1177/0963721414561510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Schermerhorn AC, Davies PT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings JS. Interparental discord and child adjustment: Prospective investigations of emotional security as an explanatory mechanism. Child Development. 2006;77:132–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Smith D. The impact of anger between adults on siblings’ emotions and social behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34:1425–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Forman EM, Rasi JA, Stevens KI. Assessing children’s emotional security in the interparental relationship: The security in the interparental subsystem scales. Child Development. 2002;73:544–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, Shelton K, Rasi JA. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67:1–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3181513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Martin MJ, Coe JL, Cummings EM. Transactional cascades of destructive interparental conflict, children’s emotional insecurity, and psychological problems across childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2016;28:653–671. doi: 10.1017/S0954579416000237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Martin MJ, Sturge-Apple ML. Emotional security theory and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental Psychopathology: Vol. 1. Theory and Methods. 3. New York: Wiley; 2016. pp. 199–264. [Google Scholar]

- Dirks MA, Persram R, Recchia HE, Howe N. Sibling relationships as sources of risk and resilience in the development and maintenance of internalizing and externalizing problems during childhood and adolescence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;42:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JR, Lambert LS. Methods of integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytic framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:1–22. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:352–370. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Buckhalt JA, Mark Cummings E, Keller P. Sleep disruptions and emotional insecurity are pathways of risk for children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Erath SA. Family conflict, autonomic nervous system functioning, and child adaptation: State of the science and future directions. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:703–721. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Solmeyer AR, Hostetler ML, Sakuma KL, Jones D, McHale SM. Siblings are special: Initial test of a new approach for preventing youth behavior problems. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Solmeyer AR, McHale SM. The third rail of family systems: Sibling relationships, mental and behavioral health, and preventive intervention in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2012;15:43–57. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0104-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Grych JH. Adolescent triangulation into parental conflicts: longitudinal implications for appraisals and adolescent-parent relations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:254–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00697.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gass K, Jenkins J, Dunn J. Are sibling relationships protective? A longitudinal study. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2007;48:167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazarian SR, Buehler C. Interparental conflict and academic achievement: An examination of mediating and moderating factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:23–35. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnight JA, Bates JE, Newman JP, Dodge KA, Pettit GS. The interactive influences of friend deviance and reward dominance on the development of externalizing behavior during middle adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:573–583. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:267–290. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research and applications. New York: Cambridge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Raynor SR, Fosco GM. Family processes that shape the impact of interparental conflict on adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:649–665. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404004717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The Self-Perception Profile for Children: Revision of the Perceived Competence Scale for Children. Department of Psychology, University of Denver; Colorado, US: 1985. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs K, Sillars A. Sibling support during post-divorce adjustment: An idiographic analysis of support forms, functions, and relationship types. Journal of Family Communication. 2012;12:167–187. doi: 10.1080/15267431.2011.584056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JM, Smith MA. Factors protecting children living in disharmonious homes: Maternal reports. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:60–69. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199001000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JM, Smith MA, Graham PJ. Coping with parental quarrels. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28:182–189. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Kouros CD. Interparental conflict and child adjustment. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 4: Risk, resilience, and intervention. New York: Wiley; 2016. pp. 608–659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Osgood DW. Longitudinal linkages between sibling relationships and adjustment from middle childhood through adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;4:960–973. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer L, Conger KJ. What we learn from our sisters and brothers: For better or for worse. New directions for child and adolescent development. 2009;2009:1–12. doi: 10.1002/cd.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik NM, Lindahl Km. System for Coding Interactions in Dyads (SCID) In: Kerig PK, Baucom DH, editors. Couple observational coding systems. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Updegraff KA, Whiteman SD. Sibling relationships and influences in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2012;74:913–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon CL, Cummings EM. Sibling disability and children’s reactivity to conflicts involving family members. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:274–285. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.13.2.274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Robles TF, Reynolds B. Allostatic processes in the family. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:921–938. doi: 10.1017/S095457941100040X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades KA. Children’s responses to interparental conflict: A meta-analysis of their associations with child adjustment. Child Development. 2008;79:1942–1956. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond MK, Stocker CM, Rienks SL. Longitudinal associations between sibling relationship quality, parental differential treatment, and children’s adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:550–559. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmeyer AR, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Longitudinal associations between sibling relationship qualities and risky behavior across adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:600–610. doi: 10.1037/a0033207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Emotional development: The organization of emotional life in the early years. New York: Cambridge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RB. Sibling attachment relationships: Child–infant interaction in the strange situation. Developmental Psychology. 1983;19:192–199. doi: 10.1037/00121649.19.2.192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RB, Marvin RS. Sibling relations: The role of conceptual perspective-taking in the ontogeny of sibling caregiving. Child Development. 1984;55:1322–1332. doi: 10.2307/1130002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlomer GL, Bauman S, Card NA. Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0018082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volling B, Blandon A. Positive indicators of sibling relationship quality: The sibling inventory of behavior. In: Moore KA, Lippman LA, editors. What do children need to flourish? New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Vu NL, Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Rosenfield D. Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: A meta-analysis of longitudinal associations with child adjustment problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016;46:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Soli A. Theoretical perspectives on sibling relationships. Journal of Family theory & Review. 2011;3:124–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2011.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Skinner EA. The development of coping: Implications for psychopathology and resilience. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental Psychopathology: Vol. 4. Risk, Resilience, and Intervention. 3. New York: Wiley; 2016. pp. 485–545. [Google Scholar]