Abstract

Objective:

HIV-infected people who inject drugs (PWID) have a disproportionally low rate of access to antiretroviral therapy (ART). We aimed to assess the impact of ART on 12-month mortality and virological failure of HIV-infected PWID in China, stratified by methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) and active drug use status.

Methods:

HIV-infected PWID who initiated ART at 29 clinics in 2011 were enrolled and followed in this prospective cohort study. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to compare the survival probability. Risk factors for mortality and virological failure were evaluated by Cox proportional hazards models and logistic regression analyses.

Results:

A total of 1,633 participants initiated ART. At the time of initiation, 324 were on MMT, 625 were engaged in active drug use, and 684 had discontinued drug use but were not on MMT. At the 12-month follow-up, 80.3% remained on ART, 13.5% had discontinued ART, and 6.2% had died. Among the MMT group, active drug use group, and drug abstinent group, we observed all-cause mortality of 4.9%, 12.0%, and 1.5% and virological suppression of 51.9%, 41.1%, and 68.7%, respectively. Factors associated with both mortality and virological failure were drug use status, unemployment, and treatment facility type.

Conclusion:

For HIV-infected PWID receiving ART, engagement in MMT and discontinuation of drug use were more likely to be associated with lower mortality and virological failure compared with active drug use. In order to maximize the clinical impact of ART, HIV treatment programs in China should be further integrated with MMT and social services.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Antiretroviral therapy, People who inject drug, Mortality, Virological failure

1. Introduction

The introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has substantially reduced HIV-related morbidity and mortality worldwide. Nevertheless, for HIV-infected people who inject drugs (PWID), access to care and treatment is a persistent public health problem (Mathers et al., 2010; Petersen et al., 2013; Strathdee et al., 2012). Many studies have shown that PWID experience delays in HIV testing, low treatment coverage, high treatment discontinuation, and high rates of virological failure (Leng et al., 2014; Risher et al., 2015; Werb et al., 2013). Compared to other HIV-infected populations, HIV-infected PWID exhibit poorer response to ART and faster progression to AIDS and death, and as a result, rates of HIV-related and all-cause mortality among HIV-infected PWID remain high (Lappalainen et al., 2015; Parashar et al., 2016).

Many individual, social, and structural predictors of poor outcomes among HIV-infected PWID have been identified, including hepatitis C co-infection, late diagnosis, withholding of ART by providers, non-adherence to treatment, ongoing drug use, depression, stigma, incarceration, and unstable housing conditions (Parashar et al., 2016; Strathdee et al., 2012; Wolfe et al., 2010). The available data point to the dual combination of ART and opioid substitution treatment, such as methadone maintenance therapy (MMT), as the most effective strategy to improve the health outcomes of HIV-infected PWID. Engagement in MMT has been shown to increase ART initiation and adherence and to reduce mortality among PWID (Low et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2015).

The issue of providing care to HIV-infected PWID has taken on growing significance in China, which has the largest population of PWID in the world at 2.35 million people (Mathers et al., 2008). At the end of 2014, the reported HIV prevalence among PWID in China was 6.0% (National Health and Family Planning Commission, 2015). The Chinese government has implemented comprehensive strategies for the treatment of both HIV and opioid dependence through the National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program (NFATP) and the National Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) Program (Simard and Engels, 2010; Wu et al., 2007; Yin et al., 2010). However, progress towards providing universal ART access to HIV-infected individuals in China has lagged among PWID, and nationwide studies have suggested that ART coverage remains low among PWID (Zhang et al., 2011). This paper aims to investigate the clinical impact of ART for PWID in China, which has not been previously described, with 12-month mortality as the primary outcome. We also assess the relationship between active drug use and MMT engagement on mortality and virological failure after one year of ART.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

A prospective observational cohort was established, comprising patients of 29 ART clinics located in the provinces of Yunnan (13 clinics), Guangxi (7 clinics), Xinjiang (4 clinics), Guizhou (2 clinics), Chongqing (2 clinics), and Hunan (1 clinic). The 29 clinics were selected because they had previously treated high cumulative numbers of PWID among their patient population compared to clinics nationwide. Our criteria for enrollment were 1) having been identified as acquiring HIV infection through injecting drug use during the initial assessment at the time of diagnosis; 2) enrolled at one of the study ART clinics; 3) being ART-naive prior to study enrollment; and 4) meeting the 2011 NFATP entry criteria of a baseline CD4 cell count ≤350 cells/mm3. CD4 cell count results obtained within three months prior to ART initiation were considered baseline. We enrolled all HIV-infected PWID who met the study entry criteria and initiated ART between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011.

Since the establishment of the NFATP in 2004, ART has been provided free-of-charge for all eligible HIV-infected patients, including PWID. Over the study period, the NFATP eligibility criteria were CD4 cell count result ≤350 cells/mm3 or a World Health Organization clinical stage of 3 or 4. The first-line ART regimen options before 2012 were zidovudine (AZT)/stavudine (D4T), lamivudine (3TC), and nevirapine (NVP)/efavirenz (EFV).

Within the cohort, participants were classified into three subgroups based on their MMT and drug use status upon ART initiation. The MMT group was defined as the participants who were concurrently participating in MMT program, irrespective of active drug use. Enrollment into MMT was determined through the national MMT data system, which has been previously described (Zhao et al., 2015). The national ART data system is linked with the national MMT data system through participant identification numbers. MMT clients receive oral liquid methadone under daily directly observed treatment at MMT clinics. Program guidelines suggest an initial methadone dosage of 50mg/day for all MMT clients, which is subsequently adjusted as appropriate. Study participants who were not on MMT were categorized into the active drug use group or the drug abstinent group. Data on active drug use at the time of ART enrollment were reported by physicians based on clinical interviews. Abstinent drug users were defined as participants who had a negative urine morphine test and self-reported no ongoing drug use at the beginning of ART.

2.2. Data collection

The identification and demographic data for each participant were extracted from the online national ART data system managed by the Chinese National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention (NCAIDS). Clinical information on ART and health outcomes, including baseline CD4 cell count, ART regimen, viral load test results, drug use, MMT engagement, date and cause of death, date and cause of ART discontinuation, and prescribing ART facility type was collected through standardized study case reporting forms. Forms were completed by local ART-providing physicians and uploaded to the data system.

2.3. Follow-up and outcomes

For each participant, the duration of observation was the date of ART initiation to the date of death, withdrawal from treatment, or the 12-month follow-up point. The study follow-up intervals followed the NFATP standard-of-care schedule; routine follow-up visits during the first year of ART occur at 2 weeks, 1 month, 2 months, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months. After 12 months, routine follow-up visits are conducted every 3 months. Participants were designated as having withdrawn from treatment if they state a desire to leave treatment or if they stopped attending follow-up visits prior to the 12-month point.

The primary outcome of this study was mortality at 12 months after ART initiation. The observed study time of all participants was calculated from the ART initiation to the end of the study at 12-months follow-up, or until death that occurred before ending the study, or discontinuation of ART (including loss to follow-up) before the end of the study. Subjects were categorized as being lost to follow-up) if they missed all follow-up appointments for at least three months. The secondary outcome was virological failure, defined as a detectable plasma HIV-1 RNA test result (> 400 copies/mL) using the NucliSens EasyQ HIV-1 assay (bioMerieux). The NFATP provides free viral load testing once a year with the first viral load test occurring 6–18 months after ART initiation; thus, we accepted viral load results from the 6–18 month period for the study analysis. We adopted the last result if multiple viral load tests were conducted during the observational period. For cases on treatment, missing viral load tests were not considered indicative of loss to follow-up.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We used Pearson chi-square tests for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables to describe the study cohort. We calculated survival probabilities by Kaplan-Meier curves and assessed statistical significance between groups by using log-rank tests. Survival times were calculated as the time from ART initiation until death or the last follow-up (at which survival times were censored). All-cause mortality was calculated as the number of deaths divided by the number of group members. Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine risk factors for mortality, and logistic regression models were used to analysis the risk of virological failure. Adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs), adjusted odds ratios (AORs), and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by multivariable regression models. Two-sided p-values are presented, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Variables that were significant in univariate analysis were considered for the multivariable model. We also examined all variables for correlation and interaction, and excluded the variables that were highly correlated. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute Inc., USA).

2.5. Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of NCAIDS, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC). All participants signed an informed consent form for participating in this study. Study data were de-identified prior to analysis.

3. Results

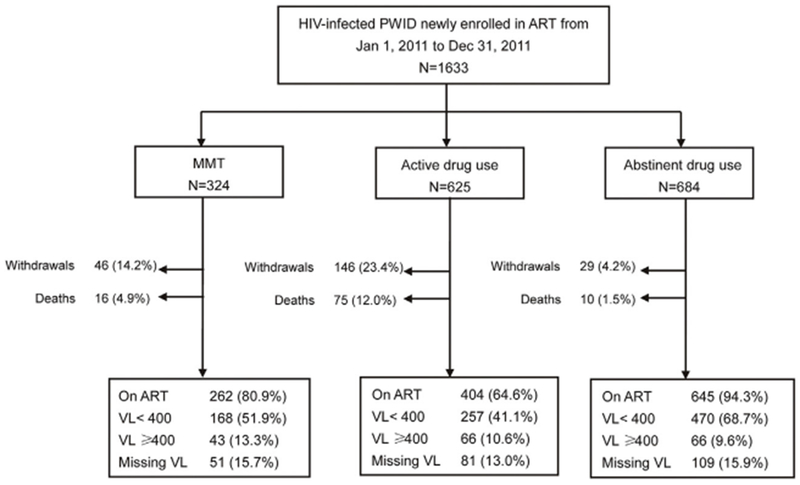

A total of 1,633 HIV-infected PWID were enrolled on ART from 29 clinics between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011. The geographical distribution of participants by province was: 792 in Yunnan, 378 in Xinjiang, 297 in Guangxi, 71 in Hunan, 64 in Guizhou, and 31 in Chongqing. At the time of ART initiation, there were 324 participants who were receiving MMT, 625 participants who were not on MMT and engaged in active drug use, and 684 participants who were not on MMT and had discontinued drug use. The study flowchart is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study–the number of participants by group and outcome.

PWID = people who inject drugs, ART = antiretroviral therapy, MMT = methadone maintenance treatment, VL = viral load.

Characteristics of the groups are described in Table 1. Participants had a median age of 38 years (interquartile range (IQR): 34–42), 84.2% were male, 62.5% had at least a middle school education, and 56.2% were of Han ethnicity. Most were unemployed (70.4%) and over half were married (56.2%). The groups differed significantly on the demographic characteristics of educational level (p = 0.021), ethnicity (p < 0.001), employment status (p < 0.001), and marital status (< 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of HIV-infected people who inject drugs at ART initiation in China.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 1633) | MMT (N = 324) | Active drug use (N = 625) | Abstinent Drug use (N = 684) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 38.0 (34.0–42.0) | 38.0 (34.0–41.0) | 38.0 (34.0–42.0) | 38.0 (34.0–42.0) | 0.560 |

| <40 | 1011 (61.9%) | 199 (61.4%) | 396 (63.4%) | 416 (60.8%) | 0.570 |

| ≥40 | 622 (38.1%) | 125 (38.6%) | 229 (36.6%) | 268 (39.2%) | |

| Gender | 0.082 | ||||

| Male | 1375 (84.2%) | 262 (80.9%) | 523 (83.7%) | 590 (86.3%) | |

| Female | 258 (15.8%) | 62 (19.1%) | 102 (16.3%) | 94 (13.7%) | |

| Education level | 0.021 | ||||

| ≤ Primary school | 529 (32.4%) | 93 (28.7%) | 189 (30.2%) | 247 (36.1%) | |

| ≥ Middle school | 1021 (62.5%) | 219 (67.6%) | 398 (63.7%) | 404 (59.1%) | |

| Missing | 83 (5.1%) | 12 (3.7%) | 38 (6.1%) | 33 (4.8%) | |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| Han | 918 (56.2%) | 222 (68.5%) | 338 (54.1%) | 358 (52.3%) | |

| Minority | 650 (39.8%) | 95 (29.3%) | 259 (41.4%) | 296 (43.3%) | |

| Missing | 65 (4.0%) | 7 (2.2%) | 28 (4.5%) | 30 (4.4%) | |

| Employment status | <0.001 | ||||

| Unemployed | 1150 (70.4%) | 250 (77.2%) | 477 (76.3%) | 423 (61.8%) | |

| Employed | 433 (26.5%) | 65 (20.1%) | 110 (17.6%) | 258 (37.7%) | |

| Missing | 50 (3.1%) | 9 (2.8%) | 38 (6.1%) | 3 (0.4%) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||

| Single/divorced/widowed | 705 (43.2%) | 155 (47.8%) | 314 (50.2%) | 236 (34.5%) | |

| Married/cohabitating | 917 (56.2%) | 167 (51.5%) | 306 (49.0%) | 444 (64.9%) | |

| Missing | 11 (0.7%) | 2 (0.6%) | 5 (0.8%) | 4 (0.6%) | |

| Structural and Behavioral Characteristics | |||||

| Level of treatment facility | 0.005 | ||||

| Provincial/city | 293 (17.9%) | 50 (15.4%) | 129 (20.6%) | 114 (16.7%) | |

| Prefecture | 735 (45.0%) | 138 (42.6%) | 257 (41.1%) | 340 (49.7%) | |

| County/district | 605 (37.0%) | 136 (42.0%) | 239 (38.2%) | 230 (33.6%) | |

| Type of treatment facility | <0.001 | ||||

| Infectious disease hospital | 570 (34.9%) | 86 (26.5%) | 205 (32.8%) | 279 (40.8%) | |

| General hospital | 821 (50.3%) | 188 (58.0%) | 285 (45.6%) | 348 (50.9%) | |

| CDC clinic | 242 (14.8%) | 50 (15.4%) | 135 (21.6%) | 57 (8.3%) | |

| History of drug use (years) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 14.0 (11.0–18.0) | 14.0 (11.0–17.0) | 14.0 (11.0–17.0) | 14.0 (11.0–18.0) | 0.282 |

| <10 | 228 (14.0%) | 44 (13.6%) | 73 (11.7%) | 111 (16.2%) | 0.294 |

| 10–15 | 486 (29.8%) | 116 (35.8%) | 143 (22.9%) | 227 (33.2%) | |

| ≥15 | 644 (39.4%) | 164 (50.6%) | 171 (27.4%) | 309 (45.2%) | |

| Missing | 275 (16.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 238 (38.1%) | 37 (5.4%) | |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| Baseline CD4 count (cells/μL) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 183(95–258) | 199(121–257) | 178(88–260) | 179(90–257) | 0.065 |

| <200 | 928 (56.8%) | 163 (50.3%) | 364 (58.2%) | 401 (58.6%) | 0.030 |

| 200–350 | 705 (43.2%) | 161 (49.7%) | 261 (41.8%) | 283 (41.4%) | |

| Baseline Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 135.0 (116.0–150.0) | 134.0 (118.0–147.0) | 129.0 (113.3–145.0) | 139.0 (119.0–154.0) | <0.001 |

| ≥120 | 472 (28.9%) | 84 (25.9%) | 215 (34.4%) | 173 (25.3%) | <0.001 |

| <120 | 1141 (69.9%) | 234 (72.2%) | 401 (64.2%) | 506 (74.0%) | |

| Missing | 20 (1.2%) | 6 (1.9%) | 9 (1.4%) | 5 (0.7%) | |

IQR = interquartile range.

Study participants were engaged in HIV care at different facility types. By descending level of facility, participants attended provincial/city- (17.9%), prefecture- (45.0%), and county/district-level (37.0%) facilities. Half of the participants (50.3%) received treatment at general hospitals, 34.9% at infectious disease hospitals, and 14.8% at clinics attached to the local CDC. We observed differences among study groups in both the level of facility (p = 0.005) and the type of treatment facility (p< 0.001). Study participants self-reported a median of 14 years of drug use prior to ART initiation (IQR: 11–18). The median baseline CD4 cell counts and hemoglobin levels were 183 cells/mm3 (IQR: 95–258) and 135g/DL (IQR: 116–150), respectively. The median hemoglobin was significantly different between groups (p < 0.001).

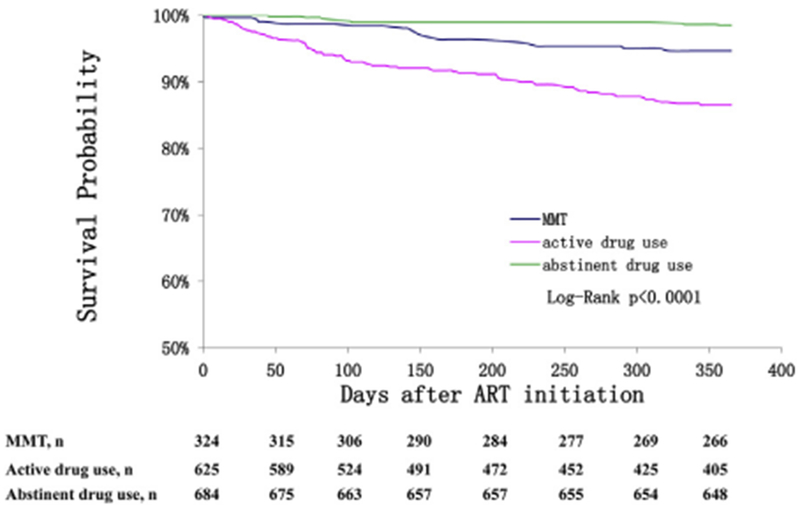

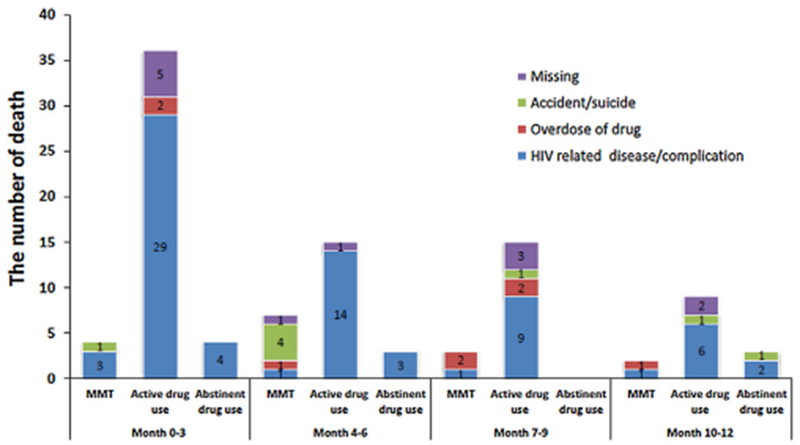

At the 12-month follow-up (Fig. 1), 80.3% were still on ART, 13.5% had discontinued ART, and 6.2% had died. The MMT group, active drug use group, and drug abstinent group reported ART discontinuation of 14.2%, 23.4%, and 4.2% and all-cause mortality of 4.9%, 12.0%, and 1.5%, respectively. Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig. 2) show significantly different (p < 0.001) 12-month survival probabilities at 94.7% among the MMT group, 86.6% among the active drug use group, and 98.5% among the drug abstinent group. Of the 101 participants who died by the 12-month follow-up, 43.6% of participants died in the first quarter (i.e., the first three months), 24.8% died during the second quarter, 17.8% died in the third quarter, and 13.9% died in the fourth quarter. Causes of death (Fig. 3) were reported as drug overdose (7.9%), HIV-related disease or complication (72.3%), accident or suicide (7.9%), or unknown (11.9%).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves by study group.

Comparison of survival curves from ART initiation to the 12-month follow-up for the MMT group, the active drug use group, and the abstinent drug use group.

Fig. 3.

Causes of death by study group and quarter of year.

Breakdown of reported causes of death per quarter for the MMT group, the active drug use group, and the abstinent group.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the AHRs for mortality (Table 2). Unemployment (AHR = 23.5, 95%CI: 3.3–170.4), ongoing drug use (AHR = 6.2, 95%CI: 3.1–12.3), MMT engagement (AHR = 2.7, 95%CI: 1.2–6.0), male (AHR = 2.2, 95%CI: 1.1–4.5), baseline CD4 < 200 cells/mm3 (AHR = 2.1,95% CI: 1.3–3.4), baseline hemoglobin < 120 g/L (AHR = 2.2, 95%CI: 1.4–3.3), and lower level of treatment facility (relative to provincial/city level: county level AHR = 6.2, 95% CI: 1.7–23.0; prefecture level AHR = 4.9, 95% CI: 1.3–17.9) were independently associated with mortality rates.

Table 2.

Mortality and its associated risk factors from Cox proportional hazards regression model.

| Characteristics | Total(N) | Death(N) | Mortality per 100 person-years | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <40 | 1011 | 50 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| ≥40 | 622 | 51 | 9.3 | 1.6(0.6–4.0) | 0.310 | 1.3 (0.5–3.4) | 0.563 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 258 | 9 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Male | 1375 | 92 | 7.6 | 2.0(1.0–4.0) | 0.045 | 2.2 (1.1–4.5) | 0.030 |

| Education level | |||||||

| ≥ Middle school | 1021 | 63 | 6.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| ≤ Primary school | 529 | 33 | 7.3 | 1.1(0.7–1.6) | 0.812 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 0.761 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Minority | 650 | 36 | 6.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Han | 918 | 61 | 7.4 | 1.2(0.8–1.8) | 0.445 | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 0.959 |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Employed | 433 | 1 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Unemployed | 1150 | 100 | 10.3 | 41.9(5.8–300.2) | <0.001 | 23.5 (3.3–170.4) | 0.002 |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married/cohabitating | 917 | 38 | 4.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Single/divorced/widowed | 705 | 61 | 9.9 | 2.1(1.4–3.2) | <0.001 | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 0.141 |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||||

| Baseline CD4 count (cells/μL) | |||||||

| 200–350 | 705 | 25 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| <200 | 928 | 76 | 9.3 | 2.3(1.5–3.7) | <0.001 | 2.1 (1.3–3.4) | 0.004 |

| Baseline Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |||||||

| ≥120 | 1141 | 50 | 4.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| <120 | 472 | 49 | 12.3 | 2.5(1.7–3.7) | <0.001 | 2.2 (1.4–3.3) | <0.001 |

| Treatment Regimen | |||||||

| Other | 316 | 15 | 5.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| AZT/D4T + 3TC + NVP | 388 | 31 | 9.0 | 1.6(0.9–3) | 0.127 | 1.4 (0.7–2.7) | 0.350 |

| AZT/D4T + 3TC + EFV | 929 | 55 | 6.6 | 1.2(0.7–2.1) | 0.559 | 1.4 (0.7–2.5) | 0.330 |

| Structural and Behavioral Characteristics | |||||||

| Level of treatment facility | |||||||

| Provincial/city | 293 | 3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Prefecture | 735 | 44 | 6.8 | 6.1 (1.9–19.6) | 0.002 | 4.9 (1.3–17.9) | 0.018 |

| County/district | 605 | 54 | 10.4 | 9.3(2.9–29.6) | <0.001 | 6.2 (1.7–23.0) | 0.007 |

| Type of treatment facility | |||||||

| Infectious disease hospital | 570 | 15 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| General hospital | 821 | 55 | 7.7 | 2.7(1.5–4.8) | 0.001 | 1.2 (0.6–2.3) | 0.623 |

| CDC clinic | 242 | 31 | 15.6 | 5.4(2.9–10.0) | <0.001 | 1.3 (0.7–2.7) | 0.441 |

| Drug use status | |||||||

| Abstinent drug use | 684 | 10 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| MMT | 324 | 16 | 5.5 | 3.6(1.6–7.9) | 0.002 | 2.7 (1.2–6.0) | 0.018 |

| Active drug use | 625 | 75 | 15.2 | 9.6(5.0–18.7) | <0.001 | 6.2 (3.1–12.3) | <0.001 |

HR: hazard ratio, CI: 95% confidence interval.

We had results from 1,329 viral load tests for the 1,070 participants who had a least one viral load test between 6 months and 18 months post-ART initiation. The median time to the baseline viral load test for all participants was 357 days (IQR: 277–399) following initiation. The median time to viral load test was similar across groups: 361 days (IQR: 303–394) in the MMT group, 354 days (IQR:271–393) in the active drug use group and 357 days (IQR: 275–411) in the drug abstinent group. Upon comparison, we did not find differences in baseline characteristics between participants with and without viral load testing. Over half of the participants (53.8%, 895/1633) achieved virological suppression (< 400 copies/mL). Virological suppression was highest among the drug abstinent group (68.7%) compared to the MMT group (51.95%) and the active drug use group (41.1%). In multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 3), being unmarried or divorced (AOR = 1.63; 95%CI: 1.13–2.35), unemployment (AOR = 1.64, 95%CI: 1.05–2.56), minority ethnicity (AOR = 1.95, 95%CI: 1.33–2.88), MMT (AOR = 1.65, 95%CI: 1.02–2.66), active drug use (AOR = 1.68, 95%CI: 1.10–2.57), and receiving ART at a CDC-affiliated facility (AOR = 2.53,95%CI: 1.30–4.94) were independently associated with virological failure rates.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression of risk factors for viroiogicai failure (viral load ≥ 400 copies/ml) after 12 months of ART.

| Characteristics | Total | Virological Failures n (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <40 | 673 | 109 (16.2%) | 0.96(0.69–1.36) | 0.833 | 0.99 (0.68–1.44) | 0.964 |

| ≥40 | 397 | 66 (16.6%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 189 | 28 (14.8%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Male | 881 | 147 (16.7%) | 1.15 (0.74–1.79) | 0.528 | 1.04 (0.62–1.75) | 0.886 |

| Education level | ||||||

| ≥ Middle school | 688 | 105 (15.3%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| ≤ Primary school | 336 | 65 (19.3%) | 1.33(0.95–1.87) | 0.100 | 1.14 (0.76–1.69) | 0.534 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Minority | 410 | 91 (22.2%) | 1.93(1.38–2.68) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.33–2.88) | 0.001 |

| Han | 620 | 80 (12.9%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 342 | 33 (9.6%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Unemployed | 692 | 137 (19.8%) | 2.31 (1.54–3.46) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.05–2.56) | 0.030 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/cohabitating | 626 | 84 (13.4%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Single/divorced/widowed | 436 | 90 (20.6%) | 1.68(1.21–2.33) | 0.002 | 1.63 (1.13–2.35) | 0.009 |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||||

| Baseline CD4 count (cells/μL) | ||||||

| 200–350 | 455 | 86 (18.9%) | 1.38(1.00–1.91) | 0.053 | 1.36 (0.94–1.95) | 0.103 |

| <200 | 615 | 89 (14.5%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Baseline Hemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||||

| ≥120 | 775 | 130 (16.8%) | 1.19(0.81–1.74) | 0.372 | 1.12 (0.72–1.74) | 0.630 |

| <120 | 283 | 41 (14.5%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Treatment Regimen | ||||||

| AZT/D4T + 3TC + EFV | 642 | 96 (15%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| AZT/D4T + 3TC + NVP | 238 | 40 (16.8%) | 1.15 (0.77–1.72) | 0.500 | 1.05 (0.66–1.66) | 0.830 |

| Other | 190 | 39 (20.5%) | 1.47(0.97–2.22) | 0.068 | 1.13 (0.71–1.80) | 0.601 |

| Structural and Behavioral Characteristics | ||||||

| Level of treatment facility | ||||||

| Provincial/city | 195 | 25 (12.8%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Prefecture | 493 | 101 (20.5%) | 1.75(1.09–2.81) | 0.020 | 1.19 (0.60–2.36) | 0.626 |

| County/district | 382 | 49 (12.8%) | 1.00(0.60–1.68) | 0.998 | 0.56 (0.26–1.19) | 0.130 |

| Type of treatment facility | ||||||

| Infectious disease hospital | 393 | 47 (12%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| General hospital | 551 | 93 (16.9%) | 1.49(1.02–2.18) | 0.037 | 1.31 (0.75–2.28) | 0.346 |

| CDC clinic | 126 | 35 (27.8%) | 2.83(1.73–4.64) | <0.001 | 2.53 (1.30–4.94) | 0.006 |

| Drug use status | ||||||

| Abstinent drug use | 536 | 66(12.3%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| MMT | 211 | 43 (20.4%) | 1.82(1.19–2.78) | 0.005 | 1.65 (1.02–2.66) | 0.040 |

| Active drug use | 323 | 66 (20.4%) | 1.83(1.26–2.66) | 0.002 | 1.68 (1.10–2.57) | 0.017 |

OR: odds ratio, CI: 95% confidence interval.

4. Discussion

It is valuable to evaluate the impact of ART on this population because China has the largest population of PWID among all countries (Mathers et al., 2008). The purpose of this observational study was to assess mortality and virological failure outcomes after one year of ART among a cohort of HIV-infected PWID in China. In our cohort, PWID who continued to actively use drugs experienced higher rates of interruptions in ART, mortality, and virological failure compared with the MMT group and the drug abstinent group. Concurrent MMT was associated with improved outcomes on ART, compared with active drug use.

While the World Health Organization guidelines specify that former or current substance abuse status should not be cause for exclusion from ART, some health providers continue to withhold treatment from HIV-infected PWID (Westergaard et al., 2012; WHO et al., 2012). This may be due to a perception that PWID are less likely to be adherent and thus, more likely to develop antiretroviral drug resistance. However, the existing research evidence has shown that PWID do not have higher rates of drug resistance than people who do not use drugs (Frentz et al., 2014; Werb et al., 2010). Our study provides further evidence that PWID with well ART compliance can achieve comparable viral suppression, even if engaged in active drug use, which supports the standard that health care providers should not consider former or present drug use to be exclusion criteria for ART initiation. Studies in North America and Europe have noted even higher virological suppression rates of 55–70% among PWID with active drug use (Kerr et al., 2012; Milloy et al., 2016).

Despite reductions in HIV-related mortality in China and worldwide, HIV-infected individuals with a history of injecting drug use continue to have an increased risk of death compared to other subgroups, due in part to the disproportionately low access to ART (Mathers et al., 2010; Wolfe et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011). Other factors that contribute to increased mortality risk among PWID are late ART initiation, lower adherence to treatment, co-infection with hepatitis C and tuberculosis, active drug use, and unstable social factors such as poverty, depression, negative life events, and discrimination (Dias et al., 2011; Milloy et al., 2012b). Our study found that among PWID, the one-year mortality (12.0%) among active drug users was 2.5 times the MMT group mortality rate and 8 times the drug abstinent group mortality rate. The majority of deaths among the participants were attributed to HIV-related complications, but we also observed a troublingly high rate of deaths due to drug overdose (7.9%) and accident or suicide (7.9%).

In our cohort, the primary predictor of mortality among HIV-infected PWID was a low CD4 cell count at the time of ART initiation. As in previous studies in China, our findings show that a low CD4 cell count at the time of ART initiation was a strong determinant of mortality among PWID (Liu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2011), which is the driver of the high proportion of HIV-related deaths. We also observed that deaths were most likely to occur in the first six months after ART initiation, followed by gradual reductions in the following quarters. This trend has been reported in our previous study as well as in other international publications (Braitstein et al., 2006; Severe et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2009).The high death rate at the early stage after ART initiation may be associated with low CD4 cell counts at ART initiation. Reasons for late HIV diagnosis among PWID include fear of detention, stigma, discrimination by health providers, and difficulty in reaching health facilities (Tang et al., 2014). The proportion of patients experiencing late ART initiation is still highly problematic (Kiertiburanakul et al., 2014), and late diagnosis of HIV infection remains a major challenge for China’s national ART program (Dou et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2011).

Adherence is the key barrier in achieving viral suppression, which is a well-known Achilles’ heel to capturing the clinical and public health benefits of ART. It has been shown that PWID can achieve high adherence rates with the support of opioid substitution treatment programs. MMT increases ART initiation and adherence through regular contact with the health care system and decreases in drug use behaviors, which promotes social reintegration (Wolfe et al., 2010); furthermore, concurrent engagement in ART and MMT improves rates of treatment retention and viral load suppression (Reddon et al., 2014; Roux et al., 2008). In our study, we found that participants who continued drug use had the lowest retention rate on treatment, and common reasons for dropout were unstable living conditions, continued dependence on illicit opioids, and entering compulsory detoxification centers.

In this study, we draw upon data from the world’s largest MMT network, and we found that MMT was associated with lower mortality compared to ongoing drug use, but no significant association was found between MMT and active drug users in virological suppression. We suspect that this may be due to a high proportion of missing viral load tests or concurrent active drug use among MMT clients. It may also be related to the high lost-to-follow rate among active drug users (23.4%) largely contributed to the low viral suppression rate (41%) and impact on the analysis of comparing of virological suppression between MMT and active drug use groups, which showed no significance. A sample of 178 Chinese MMT clients found that 44.9% reported active drug use or had a positive urine test within a 30-day period (Li et al., 2012). Active drug use may be counteracting the effect of MMT on improving ART adherence, which we were not able to track in our dataset. Moreover, drug-drug interactions between methadone and antiretroviral medications have been reported as a common complication. Some ART medications (e.g., NNRTIs) can decrease the blood concentration of methadone, leading to reduced effectiveness of methadone in preventing opioid withdrawal symptoms. Nevertheless, studies elsewhere have shown that PWID can experience the full benefit of ART if compliance to treatment regimens is present (Sangsari et al., 2012; Wisaksana et al., 2010). A study in Canada reported that among PWID who had ≥95% adherence, 81% achieved viral suppression in the first year of ART (Nolan et al., 2011). Another study in Indonesia found that there were not significant differences in adherence or mortality rates between PWID and people who do not use drugs (Wisaksana et al., 2010).

Interventions at the community and structural levels are also needed to reduce HIV-related and all-cause mortality among PWID (Jin et al., 2013; Parashar et al., 2016; Wolfe et al., 2010). For current and former PWID, unstable living conditions, poor social support, financial barriers, and irregular attendance at medical appointments frequently results in their loss from the care system (Mathers et al., 2010; Milloy et al., 2012a). Our study noted that being unmarried and being unemployed were strongly associated with increased mortality and virological failure rates, which highlights the important role of social support in maximizing treatment response. The relationship between social support and HIV treatment outcomes among PWID is mediated by adherence and depression (Batchelder et al., 2013; Garcia de la Hera et al., 2011; Krusi et al., 2010), and future research in China should explore these effects in-depth. Of note, participants in our cohort who were unemployed had 23.5 times the risk of death compared to employed participants. Although access to ART medications is free in China, patients need to bear the financial burdens of travelling to the clinic and exams for co-morbid conditions, and employment serves dual benefits in providing both social and financial stability. HIV treatment programs should be further integrated with social services, such as employment training programs.

Finally, due to the structure of China’s healthcare system, the national ART program delivers care through a variety of settings, including infectious disease specialty hospitals, general hospitals, and local CDC facilities. Our results showed significant associations between the type of treatment-providing facility and subsequent risks of virological failure and mortality, which is consistent with previous study results (Simard and Engels, 2010). Specialized infectious disease hospital and facilities at higher levels (e.g., provincial-level compared to prefecture-level) were more likely to produce better outcomes. The improved clinic results at these facilities may be due to greater numbers of providers with advanced training and experience in managing ART and more effective monitoring practices (Sangsari et al., 2012).

Our study was limited to the available observational data. Categorization of drug use was based on participant self-report at the time of ART initiation and is subject to misclassification; we did not have data on MMT clients who were engaged in ongoing drug use or ART and MMT adherence. We also did not have viral load results for approximately 13% of our participants, although we did not find significant baseline differences between participants who did or did not receive viral load testing. Furthermore, the timing of viral load tests varied from 6 to 18 months after ART initiation, and it is possible that the distribution of the viral load testing dates varied between groups, which would affect virological suppression rates. However, due to our large sample size across many facilities and the similar median times to VL testing, we believe that significant differences are unlikely. Furthermore, the international and national clinical guidelines now recommend initiation of ART as soon as possible. Although the policy at the time of the study was to initiate patients on ART after CD4 cell counts fell below ≤350 cells/mm3, we believe that our study findings would be similar under the present guidelines. Finally, although we attempted to reduce the role of confounding variables by using multivariable regression models, the risk of confounding remains due to the effects of other unmeasured variables. The most influential of these variables may be treatment adherence, hepatitis C infection, and depression (Parashar et al., 2016).

For HIV-infected PWID receiving ART in China, discontinuation of drug use was strongly associated with survival and virological suppression. Engagement in MMT was also associated with a significant decrease in mortality compared to active drug use. The findings suggest that in order to maximize the clinical impact of ART, HIV treatment programs should be further integrated with MMT as well as linked to social supportive services.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the healthcare providers from the 29 selected clinics for their dedication in providing treatment to their patients and in completing the data reporting that made this work possible.

Role of funding source

This study was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project on Prevention and Treatment of Major Infectious Diseases including AIDS and Viral Hepatitis (2012ZX10001-007) from the China National Health and Family Planning Commission, and by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the U.S. National Institutes ofHealth (China ICOHRTA2, NIH Research Grant number is U2RTW06918). CXS is supported by awards T32MH020031 and P30MH062294 from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health. The funding organizations had no role in the development of study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or the final decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

Publisher's Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein reflect the collective views ofthe co-authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Diseases Control and Prevention.

References

- Batchelder AW, Brisbane M, Litwin AH, Nahvi S, Berg KM, Arnsten JH, 2013. Damaging what wasn’t damaged already: psychological tension and antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected methadone-maintained drug users. AIDS Care 25,1370–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A, Miotti P, Wood R, Laurent C, Sprinz E, Seyler C, Bangsberg DR, Balestre E, Sterne JA, May M, Egger M, 2006. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet 367, 817–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias A, Araújo M, Dunn J, Sesso R, Castro V.d., Laranjeira R, 2011. Mortality rate among crack/cocaine-dependent patients: a 12-year prospective cohort study conducted in Brazil. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 41, 273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Z, Chen RY, Xu J, Ma Y, Jiao JH, Durako S, Zhao Y, Zhao D, Fang H, Zhang F, 2010. Changing baseline characteristics among patients in the China national free antiretroviral treatment program, 2002-09. Int. J. Epidemiol 39 (Supp. 1), ii56–ii64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frentz D, van de Vijver D, Abecasis A, Albert J, Hamouda O, Jorgensen L, Kucherer C, Struck D, Schmit JC, Vercauteren J, Asjo B, Balotta C, Bergin C, Beshkov D, Camacho R, Clotet B, Griskevicius A, Grossman Z, Horban A, Kolupajeva T, Korn K, Kostrikis L, Linka KL, Nielsen C, Otelea D, Paraskevis D, Paredes R, Poljak M, Puchhammer-Stockl E, Sonnerborg A, Stanekova D, Stanojevic M, Vandamme AM, Boucher C, Wensing A, 2014. Patterns of transmitted HIV drug resistance in Europe vary by risk group. PLoS One 9, e94495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia de la Hera M, Davo MC, Ballester-Añón R, Vioque J, 2011. The opinions of injecting drug user (IDUs) HIV patients and health professionals on access to antiretroviral treatment and health services in Valencia, Spain. Eval. Health Prof 34, 349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Atkinson JH, Duarte NA, Yu X, Shi C, Riggs PK, Li J, Gupta S, Wolfson T, Knight AF, Franklin D, Letendre S, Wu Z, Grant I, Heaton RK, 2013. Risks and predictors of current suicidality in HIV-infected heroin users in treatment in Yunnan, China: a controlled study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 62,311–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Marshall BD, Milloy MJ, Zhang R, Guillemi S, Montaner JS, Wood E, 2012. Patterns of heroin and cocaine injection and plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression among a long-term cohort of injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 124,108–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiertiburanakul S, Boettiger D, Lee MP, Omar SF, Tanuma J, Ng OT, Durier N, Phanuphak P, Ditangco R, Chaiwarith R, Kantipong P, Lee CK, Mustafa M, Saphonn V, Ratanasuwan W, Merati TP, Kumarasamy N, Wong WW, Zhang F, Pham TT, Pujari S, Choi JY, Yunihastuti E, Sungkanuparph S, 2014. Trends of CD4 cell count levels at the initiation of antiretroviral therapy overtime and factors associated with late initiation of antiretroviral therapy among Asian HIV-positive patients. J. Int. AIDS Soc 17,18804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusi A, Wood E, Montaner J, Kerr T, 2010. Social and structural determinants of HAART access and adherence among injection drug users. Int. J. Drug Policy 21,4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen L, Hayashi K, Dong H, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Wood E, 2015. Ongoing impact of HIV infection on mortality among people who inject drugs despite free antiretroviral therapy. Addiction 110,111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng X, Liang S, Ma Y, Dong Y, Kan W, Goan D, Hsi JH, Liao L, Wang J, He C, Zhang H, Xing H, Ruan Y, Shao Y, 2014. HIV virological failure and drug resistance among injecting drug users receiving first-line ART in China. BMJ Open 4, e005886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Lin C, Wan D, Zhang L, Lai W, 2012. Concurrent heroin use among methadone maintenance clients in China. Addict. Behav 37, 264–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu E, Rou K, McGoogan JM, Pang L, Cao X, Wang C, Luo W, Sullivan SG, Montaner JSG, Bulterys M, Detels R, Wu Z, 2013. Factors associated with mortality ofHIV-positive clients receiving methadone maintenance treatment in China. J. Infect. Dis 208, 442–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low AJ, Mburu G, Welton NJ, May MT, Davies CF, French C, Turner KM, Looker KJ, Christensen H, McLean S, Rhodes T, Platt L, Hickman M, Guise A, Vickerman P, 2016. Impact of opioid substitution therapy on antiretroviral therapy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis 63, 1094–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, Wodak A, Panda S, Tyndall M, Toufik A, Mattick RP, 2008. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet 372,1733–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Mattick RP, Myers B, Ambekar A, Strathdee SA, 2010. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet 375, 1014–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Bangsberg DR, Buxton J, Parashar S, Guillemi S, Montaner J, Wood E, 2012a. Homelessness as a structural barrier to effective antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive illicit drug users in a Canadian setting. Aids Patient Care STDS 26, 60–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Buxton J, Rhodes T, Krusi A, Guillemi S, Hogg R, Montaner J, Wood E, 2012. Social and environmental predictors of plasma HIV RNA rebound among injection drug users treated with antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir. Immune defic. Syndr 59, 393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milloy MJ, Wood E, Kerr T, Hogg B, Guillemi S, Harrigan PR, Montaner J, 2016. Increased prevalence of controlled viremia and decreased rates of HIV drug resistance among HIV-positive people who use illicit drugs during a community-wide treatment-as-prevention initiative. Clin. Infect. Dis 62, 640–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Family Planning Commission, 2015. China AIDS Response Progress Report, http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/CHN_narrative_report_2015.pdf (Accessed on 5 April 2016).

- Nolan S, Milloy MJ, Zhang R, Kerr T, Hogg RS, Montaner JSG, Wood E 2011, Adherence and plasma HIV RNA response to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive injection drug users in a Canadian setting. AIDS Care 23, 980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parashar S, Collins AB, Montaner JS, Hogg RS, Milloy MJ, 2016. Reducing rates of preventable HIV/AIDS-associated mortality among people living with HIV who inject drugs. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 11, 507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen Z, Myers B, van Hout MC, Pluddemann A, Parry C, 2013. Availability of HIV prevention and treatment services for people who inject drugs: findings from 21 countries. Harm Reduct. J 10,13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddon H, Milloy MJ, Simo A, Montaner J, Wood E, Kerr T, 2014. Methadone maintenance therapy decreases the rate of antiretroviral therapy discontinuation among HIV-positive illicit drug users. AIDS Behav. 18, 740–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risher K, Mayer KH, Beyrer C, 2015. HIV treatment cascade in MSM, people who inject drugs, and sex workers. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 10,420–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux P, Carrieri MP, Villes V, Dellamonica P, Poizot-martin I, Ravaux I, Spire B, 2008. The impact of methadone or buprenorphine treatment and ongoing injection on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) adherence: evidence from the MANIF2000 cohort study. Addiction 103,1828–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangsari S, Milloy MJ, Ibrahim A, Kerr T, Zhang R, Montaner J, Wood E, 2012. Physician experience and rates of plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression among illicit drug users: an observational study. BMC Infect. Dis 12, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severe P, Leger P, Charles M, Noel F, Bonhomme G, Bois G, George E, Kenel-Pierre S, Wright PF, Gulick R, Johnson, Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW, 2005. Antiretroviral therapy in a thousand patients with AIDS in Haiti. N. Engl. J. Med 353, 2325–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard EP, Engels EA, 2010. Cancer as a cause of death among people with AIDS in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis 51, 957–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Shoptaw S, Dyer TP, Quan VM, Aramrattana A, 2012. Towards combination HIV prevention for injection drug users: addressing addictophobia, apathy and inattention. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 7,320–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Mao Y, Shi CX, Han J, Wang L, Xu J, Qin Q, Detels R, Wu Z, 2014. Baseline CD4 cell counts of newly diagnosed HIV cases in China: 2006–2012. PLoS One 9, e96098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS, 2012. Technical Guide For Countries To Set Targets For Universal Access To HIV Prevention, Treatment And Care For Injecting Drug Users: 2012 Revision. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/targets_universal_access/en/. (Accessed on November 5 2014).

- Werb D, Mills EJ, Montaner JS, Wood E, 2010. Risk of resistance to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive injecting drug users: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis 10, 464–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werb D, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Zhang R, Montaner J, Wood E, 2013. Injection drug use and HIV antiretroviral therapy discontinuation in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav. 17, 68–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard RP, Ambrose BK, Mehta SH, Kirk GD, 2012. Provider and clinic-level correlates of deferring antiretroviral therapy for people who inject drugs: a survey of North American HIV providers.J. Int. AIDS Soc 15,10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisaksana R, Indrati AK, Fibriani A, Rogayah E, Sudjana P, Djajakusumah TS, Sumantri R, Alisjahbana B, van derVen A, van Crevel R, 2010. Response to first-line antiretroviral treatment among human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with and without a history of injecting drug use in Indonesia. Addiction 105, 1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D, 2010. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: a review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet 376, 355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Sullivan SG, Wang Y, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Detels R, 2007. Evolution of China’s response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet 369, 679–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W, Hao Y, Sun X, Gong X, Li F, Li J, Rou K, Sullivan SG, Wang C, Cao X, Luo W, Wu Z, 2010. Scaling up the national methadone maintenance treatment program in China: achievements and challenges. Int. J. Epidemiol 39 (Suppl. 2), ii29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Bulterys M, Chen RY, 2009. Five-year outcomes of the China national free antiretroviral treatment program. Ann. Intern. Med 151, 241–251, W-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Zhao D, Zhou S, Bulterys M, Zhu H, Chen RY, 2011. Effect of earlier initiation of antiretroviral treatment and increased treatment coverage on HIV-related mortality in China: a national observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis 11,516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Shi CX, McGoogan JM, Rou K, Zhang F, Wu Z, 2015. Predictors of accessing antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive drug users in China’s national methadone maintenance treatment programme. Addiction 110 (Suppl. 1), 40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]