Abstract

Heterogeneous response to chemotherapy is a major issue for the treatment of cancer. For most gynecologic cancers including ovarian, cervical, and placental, the list of available small molecule therapies is relatively small compared to options for other cancers. While overall cancer mortality rates have decreased in the United States as early diagnoses and cancer therapies have become more effective, ovarian cancer still has low survival rates due to the lack of effective treatment options, drug resistance, and late diagnosis. To understand chemotherapeutic diversity in gynecologic cancers, we have screened 7914 approved drugs and bioactive compounds in 11 gynecologic cancer cell lines to profile their chemotherapeutic sensitivity. We identified two HDAC inhibitors, mocetinostat and entinostat, as pan-gynecologic cancer suppressors with IC50 values within an order of magnitude of their human plasma concentrations. In addition, many active compounds identified, including the non-anticancer drugs and other compounds, diversely inhibited the growth of three gynecologic cancer cell groups and individual cancer cell lines. These newly identified compounds are valuable for further studies of new therapeutics development, synergistic drug combinations, and new target identification for gynecologic cancers. The results also provide a rationale for the personalized chemotherapeutic testing of anticancer drugs in treatment of gynecologic cancer.

Introduction

The five main gynecologic cancers, including ovarian, cervical, uterine, vaginal, and vulvar, correspond to 12% (94,990) of new female cancer diagnoses annually in the United States [1]. Of those, uterine endometrial, ovarian, and cervical are the most prevalent, with ovarian being the fifth leading cause of death from cancer for females in the United States [2]. In 2018, it is estimated that there will be 22,240 new ovarian cancer cases (2.5% of all female cancer cases) and 14,070 ovarian cancer deaths (5% of all female cancer deaths) [2]. The high case-to-fatality ratio exhibited in ovarian cancer can be attributed to late-stage diagnosis, lack of effective drug therapies, and tumor heterogeneity. Thus, it is important to discover new therapeutics for ovarian cancers that can improve survival in late-stage ovarian cancer patients.

While ovarian cancer is usually diagnosed at later stages of disease, resulting in a low 5-year survival of 29% for distant-stage disease, cervical cancer is typically diagnosed at early stages and thus has more favorable outcomes [2]. However, in 2017, it was found that cervical cancer death rates have been underestimated due to the prior inclusion of women who have had hysterectomies [3]. Additionally, and importantly, this study identified a large disparity in race, where black women were dying at a 77% higher rate (10.1 in 100,000 vs. 5.4 in 100,000) while white women were dying at a 47% (4.7 in 100,000 vs. 3.2 in 100,000) higher rate than previously calculated without the hysterectomy exclusion criteria. Thus, cervical cancer remains a critical driver of mortality in women.

Placental cancers, or gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) choriocarcinomas, are another type of gynecologic cancer. Gestational carcinomas arise from the fetal-derived layer of cells called the trophoblast that surrounds an embryo [4] and are rare, with an incidence ranging from approximately 1 in 15,000 to 50,000 [4], [5]. A combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy is the common treatment modality for gynecologic cancers [6].

There is currently a set of standard anticancer drugs used in the clinic to treat gynecologic cancers. For ovarian and cervical cancer, these include chemotherapy agents gemcitabine, cisplatin, and doxorubicin as well as targeted therapeutics such as topotecan, a topoisomerase inhibitor, and bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth factor [7], [8]. While cisplatin is the most active and effective drug for ovarian cancer, resistance quickly develops, and many patients die with platinum-resistant cancer [9]. For placental cancer, methotrexate, a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor, or Actinomycin D, a transcription inhibitor, is often used [10]. Combination therapy is common with a platinum-based compound given along with paclitaxel, a tubulin inhibitor [11], [12]. In addition to the compounds above, vaccine, antibody, and cell-based immunotherapies are being considered as treatments for gynecologic and other solid tumor cancers [13]. Despite great progress in developing novel solutions to improve the therapeutic outcome for treatment of gynecologic cancers, more work needs to be done to understand the varied responses to different drugs in patients with different gynecologic cancers [14].

To understand the diversity in compound efficacy across gynecologic cancers within individual cancer groups and identify new active compounds, we have screened 7914 compounds consisting of approved drugs and bioactive compounds using a quantitative high-throughput screening (qHTS) method against 11 unique gynecologic cancer cell lines derived from ovarian, cervical, and placental cancers. The results were analyzed to profile the chemotherapeutic activities of compounds against these gynecologic cancer cell lines. Our data demonstrate the commonality and diversity in responses of gynecologic cancers to the anticancer agents. We have also identified a group of non-anticancer compounds with antigynecologic cancer activities that can be further studied for target identification and drug development.

Results

Assay Development

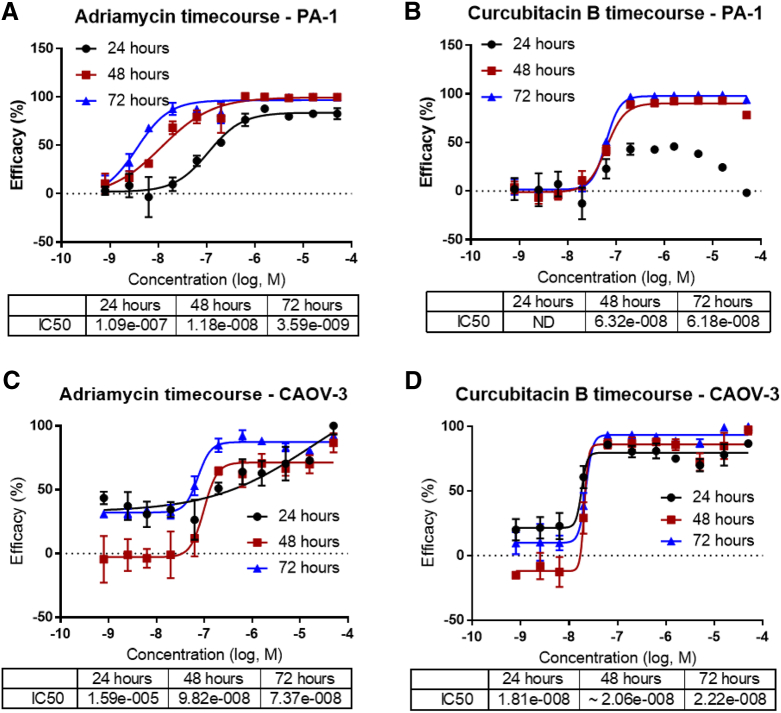

To determine the inhibitory effects of approved drugs and bioactive compounds on the common gynecologic cancer cell lines, 11 cell lines including 7 ovarian cancer lines (CAOV-3, SK-OV-3, SW 626, ES-2, PA-1, TOV-21G), 3 cervical cancer lines (HeLa, Ca Ski, and C-33 A), and 2 placental cancer lines (JAR, JEG-3) were used in the drug repurposing screen with HEK 293T cells as a control line to determine selectivity index of anticancer compounds (SI) [15], [16], [17] (Table 1; Supplementary Figure 1). The optimal assay conditions for the ATP content cell viability assay were determined in the ovarian PA-1 (Figure 1A, B and Supplementary Figure 2A-C) and CAOV-3 (Figure 1C, D and Supplementary Figure 2D-F) cell lines. Based on the assay optimization results, we used 1000 cells per well plated in 1536-well plates and a 48-hour incubation with compounds. The control compound activities (IC50) of adriamycin and curcubitacin B reached the steady state at this assay condition. Other standard-of-care (SOC) anticancer drugs examined during optimization included paclitaxel and topotecan [18] (Supplementary Figure 3A-F). Adriamycin and curcubitacin B were designated as the positive control compounds in the subsequent screens (Supplementary Figure 3G, H).

Table 1.

Cell Lines Used in the OBGYN Cancer Chemotherapeutic Profiling

| Cell Line | ATCC Catalog Number | Tissue Origin | Cancer Type or Cell Type | Mutations | Doubling time (+; days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAOV-3 | HTB-75 | Ovary | Adenocarcinoma | FAM123B, STK11, TP53 | ++ |

| SK-OV-3 | HTB-77 | Ovary | Adenocarcinoma | CDKN2A, MLH1, PIK3CA, TP53 | ++ |

| SW 626† | HTB-78 | Ovary | Grade III, adenocarcinoma | APC, KRAS, TP53 | ++ |

| ES-2 | CRL-1978 | Ovary | Clear cell carcinoma | B-RAF | ++ |

| PA1 | CRL-1572 | Ovary | Teratocarcinoma | NRAS | + |

| TOV-21G | CRL-11730 | Ovary | Grade 3, stage III, primary malignant adenocarcinoma; clear cell carcinoma | TP53 | + |

| TOV-112D* | CRL-11731 | Ovary | Grade 3, STAGE IIIC, primary malignant papillary serous adenocarcinoma; endometrioid carcinoma | CTNNB1 | ++ |

| OV-90* | CRL-11732 | Ovary | Grade 3, stage IIIC, malignant papillary serous adenocarcinoma; | BRAF | +++ |

| HeLa | CCL-2 | Cervix | Adenocarcinoma | STK11, CTNNB1 | + |

| Ca Ski | CRL-1550 | Cervix | Epidermoid Carcinoma | STAG2 | +++ |

| C-33 A | HTB-31 | Cervix | Carcinoma | RB1, PTEN, TP53 | + |

| JAR† | HTB-144 | Placenta | Choriocarcinoma | NA | +++ |

| JEG-3 | HTB-36 | Placenta | Choriocarcinoma | NA | +++ |

| HEK 293 T | CRL-3216 | Embryonic kidney | Epithelial, noncancerous | NA | ++ |

These cell lines were used only in the primary screen.

These cell lines were added for the confirmation screen.

Figure 1.

Assay development for qHTS screening of chemotherapeutic compounds. (A) Adriamycin time course dose-response curves for PA-1 cells from A, B, and C with IC50 determinations in the inset. (B) Curcubitacin B time course dose-response curves for PA-1 cells from A, B, and C with IC50 determinations in the inset. (C) Doxorubicin time course dose-response curve for CAOV-3 cells from A, B, and C with IC50 determinations in the inset. (D) Curcubitacin B time course dose-response curves for CAOV-3 cells from A, B, and C with IC50 determinations in the inset. Data points representing normalized mean ± S.D. (n = 4 wells per data point). Data were normalized to DMSO control (100% cell viability and lowest luminescence value among the 6 compounds (0% cell viability). Curves represent nonlinear regression curve fit with variable slope.

High-Throughput Compound Screening and Hit Confirmation

Following optimization, we next screened a collection of 7914 compounds including the FDA-approved drugs and bioactive compounds in 11 cancer cell lines shown in Table 1 (Supplementary Figure 1; Pubchem AID 1345084). From the primary screen, 256 hits were identified with the criteria of IC50 less than 10 μM, efficacy greater than 50%, and three-fold greater selectivity over the HEK 293T cells. From the primary screen, the signal-to-basal ratio was 9.30, coefficient of variation was 13.2% and Z' factor was 0.69 in the PA-1 cell line. For the CAOV-3 cell line, the signal-to-basal ratio was 9.86, coefficient of variation was 11.3%, and Z' factor was 0.71.

Among the primary hits tested in a follow-up screen (Pubchem AID 1345085), 205 compounds were confirmed using criteria of IC50 less than 30 μM, efficacy greater than 70%, and five-fold greater selectivity over HEK cells. A group of hits that were toxic to both cancer cells and HEK 293T cells was designated as the pan-toxic compounds (Supplementary Figure 4 and Table 2). The pan-cytotoxic compounds included panobinostat [19], givinostat [20], irestatin 9389 [21], NVP-BGT226 [22], vorinostat [23], TG-46 [24], NVP-TAE684 [25], and ponantinib [26]. The concentration-response curves for panobinostat (IC50 = 0.355 ± 0.268 μM; SI = 0.92 ± 0.57) and givinostat (IC50 = 3.50 ± 3.88 μM; SI = 1.74 ± 1.25), two HDAC inhibitors, are used as examples to illustrate the toxicity (Supplementary Figure 4).

Table 2.

Hits with HEK293T Toxicity >50%, IC50 <30 μM, and CCL Efficacy >70%.

| Toxic Compounds | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Name | FDA Approved | Compound Class | Target | Average SI | Average IC50 (μM) | ||

| Panobinostat | Yes; 2015 | Antineoplastic; hydroxamate | Pan-HDAC | 0.92 ± 0.57 | 0.355 ± 0.268 | ||

| Givinostat | No; in clinical trials | Antineoplastic; hydroxymate | Class I and II HDAC | 1.74 ± 1.25 | 3.50 ± 3.88 | ||

| Irestatin 9389 | No | Antineoplastic; diazole | IRE1 endonuclease | 0.51 ± 0.20 | 3.52 ± 3.12 | ||

| NVP-BGT226 | No; in clinical trials | Antineoplastic; imidazole quinoline | PI3K/mTOR | 0.20 ± 0.26 | 5.34 ± 6.56 | ||

| Vorinostat | Yes; 2006 | Antineoplastic; hydroxymate | HDAC | 3.72 ± 2.24 | 5.50 ± 4.17 | ||

| TG-46 | No | Antineoplastic | JAK2 | 10.5 ± 22.1 | 9.59 ± 6.87 | ||

| NVP-TAE684 | No | Antineoplastic | ALK | 4.87 ± 7.61 | 15.7 ± 10.0 | ||

| Ponantinib | Yes; 2012 | Antineoplastic; pyridazine | Bcr-Abl | 3.56 ± 4.85 | 15.9 ± 9.07 | ||

| Confirmation of HEK 293T toxicity Using an Independent Screen [84] | |||||||

| Compound Name | IC50 | Efficacy (%) | Curve Class | Independent Screen | IC50 | Efficacy (%) | Curve Class |

| Panobinostat | 0.21 | 82.6 | −1.17 | Confirmed toxic | 0.162 | 85.5 | −1.1 |

| Givinostat | 2.91 | 65.6 | −1.17 | Confirmed toxic | 1.11 | 112 | −1.1 |

| Irestatin 9389 | 1.34 | 102 | −1.1 | Not toxic | |||

| NVP-BGT226 | 0.258 | 106 | −1.1 | Confirmed toxic | 0.0145 | 115 | −1.1 |

| Vorinostat | 11.3 | 64.7 | −1.93 | Confirmed toxic | 4.09 | 80.2 | −1.2 |

| TG-46 | 19.4 | 75.6 | −2.1 | Confirmed toxic | 8.44 | 89.7 | −2.15 |

| NVP-TAE684 | 23.4 | 91.8 | −2.1 | Confirmed toxic | 3.65 | 126 | −2.1 |

| Ponantinib | 19.9 | 92 | −2.1 | Confirmed toxic | 0.811 | 92.6 | −1.1 |

Table depicting compounds that are toxic (EFFIC2ACY >70%) to all cell lines including HEK293T. Table shows compound name, FDA approval status, compound class, target, average selectivity, and average IC50 (μM).

Chemotherapeutic Diversity Among 11 Gynecologic Cancer Cell Lines

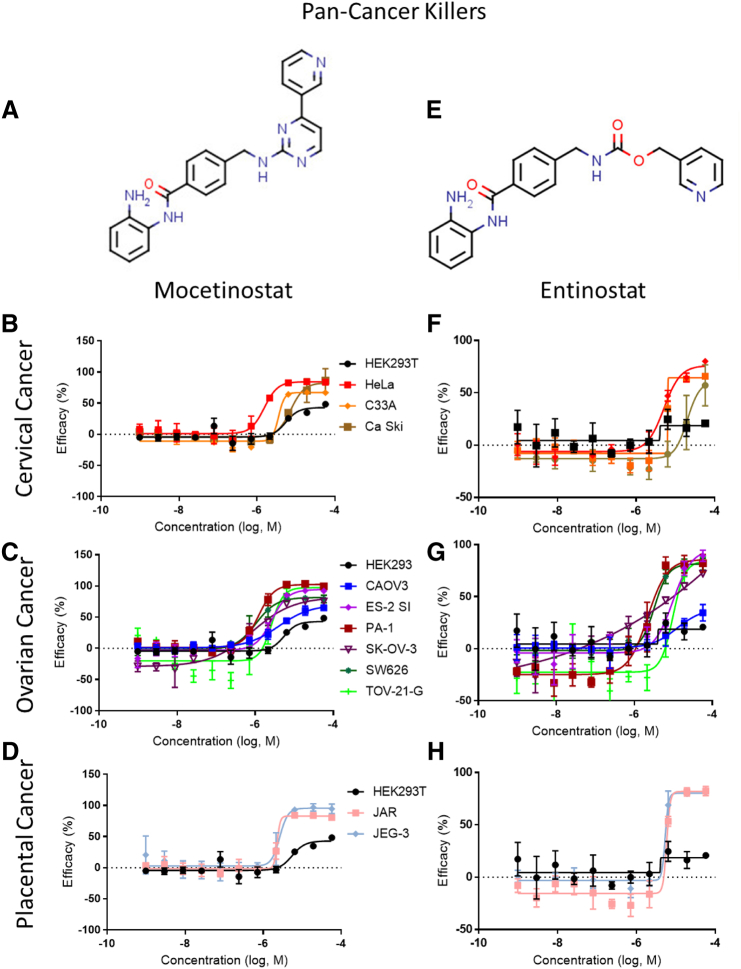

To further evaluate the 205 confirmed compounds in the 11 gynecologic cancer cell lines, we focused on the tissue types of these cancer cell lines to analyze the selectivity and diversity of compound activity. This analysis revealed two compounds, mocetinostat [27], [28], [29] (IC50 = 2.76 ± 1.98 μM; SI >100) and entinostat [30], [31] (IC50 = 7.11 ± 6.62 μM; SI >100), both class I HDAC inhibitors and in clinical trials, as pan-killers of all three cancer cell groups (Figures 2A, 3, and Table 3). The ovarian and placental cancer cell line selective inhibitors included actinomycin D [32] (IC50 = 0.78 ± 0.222 μM; SI >100), a DNA intercalator and common drug for GTD, and fedratinib [33] (IC50 = 13.1 ± 7.51 μM; SI >100), a JAK2 inhibitor (Supplementary Figure 6 and Table 3). The ovarian and cervical cancer cell line selective inhibitors included TG-89 [24] (IC50 = 11.2 ± 7.28 μM; SI >100), a JAK2 inhibitor, and CCT137690 [34] (IC50 = 20.0 ± 7.02 μM; SI >100), an Aurora kinase inhibitor (Supplementary Figure 7 and Table 3). For the individual cancer types, the top ovarian cancer cell selective inhibitor was fostamatinib [35] (IC50 = 6.24 ± 4.06 μM; SI >100), a Syk kinase inhibitor (Supplementary Figure 8A-D and Table 3). The top placental cancer line inhibitor was berberine [36], [37] (IC50 = 4.41 ± 0.662 μM; SI >100), an anti-parasitic alkaloid targeting Complex I of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and AP-1 machinery (Supplementary Figure 8E-H and Table 3). The cervical cancer selective inhibitory compounds found in our study were also active for the ovarian cancer cells.

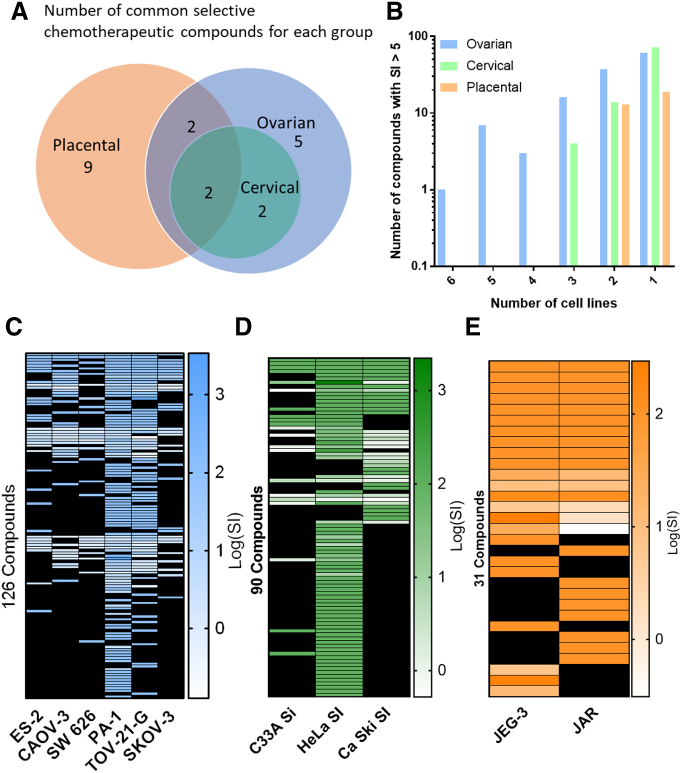

Figure 2.

Chemotherapeutic diversity in cell line killing. (A) Venn diagram illustrating the number of selective compounds (efficacy >70%, IC50 <30 μM, SI >5) in each cancer group. Overlapping circles and number inset indicate number of compounds which are shared between the groups. Compound must be active in at least four of the six ovarian cancer cell lines to be considered ovarian cancer cell line selective. (B) Log scale bar graph depicting the number of compounds which had an SI >5 for each cancer line panel. Heat maps depicting the Log (SI) value for compounds active in at least one cell line with selectivity greater than five-fold for ovarian (C), cervical (D), and placental (E) cancer panels. Black boxes indicate no selectivity could be determined for that cell line.

Figure 3.

Pan-cancer killers. Chemical structures and dose-response curves for (A) mocetinostat and (E) entinostat, respectively, for (B, F) cervical, (C, G) ovarian, and (D, H) placental cancer cell lines. See Table 4 for the full list of the best compounds from the confirmation screen.

Table 3.

Diversity List of the Most Effective Compounds with IC50 <30 μM and CCL Efficacy >70%

| Compound Name | FDA Approved | Compound Class | Target | Average SI | Average IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-GYN Cancer Cell Line Killer | |||||

| Mocetinostat | No; in clinical trials | Antineoplastic; 2-aminobenzamide | Class 1 HDAC | >100 | 2.76 ± 1.98 |

| Entinostat | No; in clinical trial | Antineoplastic; 2-aminobenzamide | Class 1 HDAC | >100 | 7.11 ± 6.62 |

| Ovarian + Placental Cancer Cell Line Killer | |||||

| Actinomycin D | Yes; 1964 | Antibiotic; antineoplastic; multiple cancers | DNA intercalater | >100 | 0.78 ± 0.222 |

| Fedratinib | No; in clinical trials | Antineoplastic | JAK2 | >100 | 13.1 ± 7.51 |

| Ovarian + Cervical Cancer Cell Line Killer | |||||

| TG-89 | No | Antineoplastic | JAK2 | >100 | 11.2 ± 7.28 |

| CCT137690 | No | Antineoplastic | Aurora kinase | >100 | 20.0 ± 7.02 |

| Ovarian Cell Line Killer | |||||

| Fostamitinib | No; in clinical trials | Prodrug; Antineoplastic | Syk | >100 | 6.24 ± 4.06 |

| AZ-960 | No | NA | JAK2 | >100 | 12.0 ± 7.75 |

| WZ3146 | No | NA | EGFR | >100 | 12.3 ± 8.52 |

| AMG-Tie2-1 | No | RTK inhibitor | Tie2 | >100 | 15.9 ± 9.71 |

| TAE226 | No | NA | FAK | 8.76 ± 2.40 | 5.32 ± 1.42 |

| Placental Cancer Cell Line Killer | |||||

| Berberine | No | Antiparasitic/antifungal; benzylisoquinoline alkaloids | Complex I of mitochondrial respiratory chain | >100 | 4.41 ± 0.662 |

| Nebupent | Yes; 1989 | Antifungal | Topoisomerase II | >100 | 4.90 ± 1.02 |

| PF-3845 | No | NA | Fatty acid amide hydrolase | >100 | 9.31 ± 1.15 |

| Cyclosporin A | Yes; 2000 | Cyclic undecapeptide; immunosuppressant | Calcineurin | >100 | 16.7 ± 5.85 |

| i-Bet-151 | No | Pyrimidoindole | BET Bromodomain | >100 | 19.3 ± 9.13 |

| WEHI-539 | No | Benzothiazole-hydrazone | BCL-X(L) | >100 | 19.3 ± 5.11 |

| Volasertib | No; in clinical trials | Dihydropteridinone | Plk1 | 131 ± 13.5 | 0.0709 ± 0.00735 |

| Rotenone | No | Rotenoid | Complex I of mitochondrial respiratory chain | 19.5 ± 6.26 | 0.0418 ± 0.0134 |

| GSK461364 | No; in clinical trials | Benzene sulfonamide thiazole | Plk1 | 8.81 ± 0.333 | 3.52 ± 0.133 |

Table shows compound name, FDA approval status, compound class, target, average selectivity, and average IC50 (μM). IC50 values are the mean of all cell lines that fulfill all criteria in the cancer grouping. Selectivity >100 indicates drug was “inactive” in HEK293T cells with efficacy <50%. No compounds were solely selective in cervical cancer.

Given that we included different numbers of cell lines for each of three gynecologic cancer groups, we assessed the number of compounds whose SI was greater than five (Figure 2B) in each group. Interestingly, while there were only 2 placental lines included in the study, 13 compounds reached an SI of 5 or greater in this group. Four compounds killed all three cervical cancer lines selectively, and only one compound, fedratinib, selectivity killed all six ovarian cancer lines. Fedratinib, one of the ovarian and cervical CCL selective inhibitors, has completed two Phase I clinical trials for solid tumors (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01836705; NCT01585623) but is not an FDA-approved drug. The heat maps for each cancer tissue group provided a high-level view of the SI for each compound that fulfilled the criteria (Figure 2C-E). These maps reveal that PA-1, TOV-21-G, and HeLa cells, the faster growing lines (Table 1), were more sensitive for qHTS as the compounds exhibited higher inhibitory activities.

Single Cancer Cell Line Selective Compounds

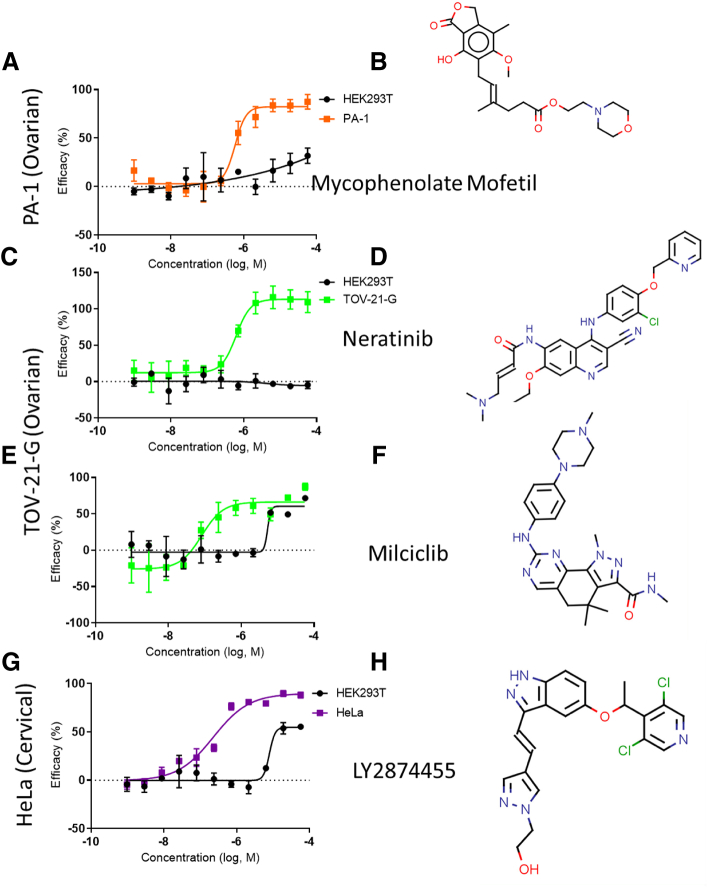

In addition to finding compounds with general antineoplastic activity, the selective inhibitory activities of compounds to individual cell lines were evaluated. We identified five compounds with selective inhibitory activities for PA-1, two compounds for TOV-21-G, and four compounds for HeLa (Figure 4 and Table 4). As mentioned above, these cell lines were the most susceptible to anticancer compounds because of their fast cell growth rates. We did not find selective compounds that only exhibited inhibitory activities to any of the eight remaining cancer cell lines individually. Since we performed a detailed analysis of the compounds' concentration-response curves, it helps to illustrate the significant differences in efficacy and potency between these lines and the control HEK 293T line. For PA-1, mycophenolate mofetil [38], an antifungal, was the most potent PA-1 suppressor (IC50 = 0.631 μM; SI >100). Neratinib [39] (IC50 = 0.619 μM; SI >100), an FDA-approved epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor, and milciclib [40] (IC50 = 0.0897 μM (SI = 50.1), a CDK inhibitor, were the two most potent TOV-21-G inhibitors. The top HeLa suppressor was LY2874455 [41] (IC50 = 0.240; SI = 38.8) μM, a pan-FGFR inhibitor.

Figure 4.

Representative compounds with selective toxicity and nanomolar potency in a single cell line. Chemical structure and dose-response curves for (A, B) mycophenolate mofetil in PA-1 cells, (C, D) neritinib in TOV-21-G cells, (E, F) milciclib in TOV-21-G cells, and (G, H) LY2974455 in HeLa cells. See Table 4 for the full list of the most effective compounds for a single cell line.

Table 4.

Single Cell Line Selective Compounds with Nanomolar Potency

| Compound Name | FDA Approved | Compound Class | Target | Avg SI | Avg IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA-1 | |||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil | Yes; 2008 | Immunosuppressant; prodrug | Inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase | >100 | 0.631 |

| Pirarubicin | No; in clinical trials | Antineoplastic; anthracycline | DNA intercalater | 14.6 | 0.839 |

| Gimatecan | No; in clinical trials | Antineoplastic; quinolone akaloid | Topoisomerase I | 12.5 | 0.0337 |

| PHA-793887 | No; in clinical trials | Antineoplastic | CDK2/1/4/9; GSK3β | 12.3 | 0.194 |

| Doxorubicin | Yes; 1993 | Antineoplastic; anthracycline | DNA intercalater | 7.02 | 0.576 |

| TOV-21-G | |||||

| Neratinib | Yes; 2017 | Antineoplastic | EGFR/Her2/Her4; P-glycoprotein | >100 | 0.619 |

| Milciclib | No; in clinical trials | Antineoplastic | CDK; tropomyosin receptor kinase | 50.1 | 0.0897 |

| HeLa | |||||

| LY2874455 | No; in clinical trials | Antineoplastic | Pan-FGFR | 38.8 | 0.240 |

| AZD3463 | No | Antineoplastic | ALK/IGFR | 30.3 | 0.638 |

| NVP-TAE684 | No | Antineoplastic | ALK | 28.0 | 0.835 |

| TAK 901 | No; completed clinical trials | Antineoplastic | Aurora Kinase | 12.6 | 0.699 |

Table shows compound name, FDA approval status, compound class, target, average selectivity, and average IC50 (μM). IC50 values are the mean of the cell line shown. Selectivity >100 indicates drug was “inactive” in HEK293T cells with efficacy <50%.

Top Clinically Relevant Compounds

The results from our qHTS gynecologic cancer profiling revealed a diverse set of compounds with potencies ranging from the nanomolar to micromolar and different selectivity among three types of cancer tissues. We wanted to highlight these nanomolar compounds which may be useful to researchers and clinicians alike as these are the ones with anticancer activity to likely be far below their blood plasma concentrations, Cmax, in patients. We analyzed our data to uncover the number of compounds with less than 1 μM potency and greater than 70% efficacy regardless of selectivity. The data correspond with the similar trend for cytotoxic susceptibility in PA-1 (43 compounds), TOV-21-G (19 compounds), and HeLa (33 compounds) cells (Supplementary Figure 9A). We arranged the data to reflect how many cell lines have a number of compounds with a potency less than 1 μM. These data show that only one compound, the multitargeted HDAC inhibitor panobinostat (IC50 = 0.355 ± 0.268 μM; SI = 0.92 ± 0.57), exhibited sub-μM potency in every cancer cell line among 11 cancer cell lines tested (Supplementary Figure 9B).

To provide useful information with clinical relevance, we have analyzed the IC90s, the concentration needed to inhibit 90% of growth, of these potent compounds and correlated it to the relevant human plasma concentration of the drug. The most potent and effective drug we identified without taking selectivity into account was panobinostat. In one clinical trial, panobinostat's median Cmax human plasma concentration after oral administration was measured to be 0.061 μM (range 0.038-0.119 μM) [42]. In an independent study, intravenous administration of panobinostat at doses from 1.20 to 20.0 mg/m2 resulted in a Cmax of 0.107 to 2.24 μM [43]. The IC50 of panobinostat for the ovarian, cervical, and placental lines in our study is 0.343, 0.224, and 0.516 μM, respectively. The IC90 average for all cell lines is 0.719 μM, within the range of the intravenous, but not oral, Cmax values.

Bortezomib, a 20S proteasome inhibitor, exhibited an average IC50 of 0.150 μM with good efficacy in 8 of the 11 cancer cell lines excluding SKOV-3, HeLa, and JAR. Its average IC90 was 0.218 μM, well within the intravenous dose Cmax of 580 nM [44]. Elesclomol, a ROS inducer, was active in six cell lines with an IC50 of 0.173 μM and an IC90 of 0.283 μM. The Cmax of elesclomol in a clinical trial ranged from 1.32 to 12.84 μM with doses of 44 to 438 mg/m2 [45]. Thus, elesclomol is a good clinically relevant candidate for gynecologic cancers. Actinomycin D, mentioned previously as an FDA-approved drug for multiple cancers, exhibited nanomolar potency against six cell lines as well while maintaining high selectivity for cancer cell lines. The average IC90 for Actinomycin D in our study against ES-2, CAOV3, PA-1, TOV-21-G, SK-OV-3, and Ca Ski was 512 nM, while the Cmax in a pediatric population can range from 4 to 97.2 nM after 15 minutes of exposure to the drug [46]. Another trial measured a Cmax ranging from 2.5 to 79 nM, indicating that the IC90 identified in our study is several-fold above what can be achieved in human blood plasma [47]. The extended comparison of IC90 to Cmax values for the most promising clinical candidates from Supplementary Figure 9 is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

IC90 and Cmax Values for Nanomolar Potent Compounds

| Compound Name | FDA Approval | IC90 (μM) | Cmax (μM) | Cell Lines Active | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panobinostat (LBH589) | Yes; 2015 | 0.719 | 0.107-2.24 | 11 | [42], [43] |

| Bortezomib | Yes; 2003 | 0.218 | 0.580 | 8 | [44] |

| Elesclomol (STA-4783) | No; in clinical trials | 0.283 | 1.32-12.84 | 6 | [45] |

| CEP-18770 (Delanzomib) | No; in clinical trials | 0.391 | 0.214-1.35 | 6 | [85] |

| BI-2536 | No; in clinical trials | 0.0397 | 1.61 | 4 | [86] |

| SN-38 | No; in clinical trials | 0.592 | 0.086 | 4 | [87] |

| Gedatolisib | No; in clinical trials | 6.80 | 16.2 | 4 | [88] |

| Gimatecan | No; clinical trials completed | 0.275 ± 0.028 | 0.103 -0.349 | 4 | [89] |

| Volasertib | No; in clinical trials | 0.090 | 1.60-2.26 | 4 | [90] |

Table shows compound name, FDA approval status, average IC90 (μM), Cmax, and the number of cell lines for which each compound is active.

Discussion

Heterogeneous responses in gynecologic cancers to chemotherapeutic drugs make it challenging to predict the drug's clinical effectiveness. This heterogeneity arises from differences in patient genetic background, patient age, tumor microenvironment, treatment regimen, and intrinsic resistance to drug therapy. In general, overall cancer incidence and death rates for women have been falling since the 1930s [2], [48]. Ovarian cancer death rates peaked in 1970 at 10.6 deaths per 100,000 women and in 2015 stood at 7.1 deaths per 100,000 women [48]. Uterine cancer, including cervix and corpus, however, killed 37.6 women per 100,000 in 1932 and now stands at 7.1 deaths per 100,000 women [48]. The last few years have seen a slight rise in death rates for uterine cancers from 6.5 in 2009 to 7.1 in 2015 [48]. Ovarian cancer’s 5-year survival rates remain among the lowest survival rates of all female cancer types, rising slowly from 1975 (36% survival) to 2013 (47% survival) [49]. Furthermore, the development of selective chemotherapeutics that are selectively toxic to cancer cells is an ongoing mission in the cancer therapeutic research field. Understanding the differences and similarities in the chemotherapeutic responses of different gynecologic cancer cell types through chemotherapeutic profiling can aid in the development of safer, more effective therapies for these types of cancers. In this work, we have utilized a qHTS approach to profile the chemotherapeutic responses and selectivity of 11 gynecologic cancer cell lines to known chemotherapeutic molecules as well as other approved drugs and biologically active compounds.

We assessed the cytotoxicity of 7914 compounds consisting of approved drugs, drug candidates tested in clinical trials, and bioactive compounds in six ovarian, three cervical, and two placental cancer cell lines. Two Class I HDACIs, mocetinostat and entinostat, were identified and confirmed as pan-gynecologic cancer inhibitors with high degrees of efficacy and selectivity (SI >100) in all three cancer groups. Interestingly, we did not find other HDACIs to be as selective except for these two. Indeed, panobinostat, givinostat, and vorinostat, three other HDAC inhibitors, were found to be equally toxic to HEK 293T cells in our screens in addition to suppressing the 11 gynecologic cancer cell lines. HDACIs prevent the removal of acetyl groups on histone lysines and, in effect, open chromatin structure to modulate gene expression [50]. Generally, epigenetic pathways are modified by HDACIs to cause changes in the expression of genes which can induce cell-cycle arrest or apoptosis [51]. In addition to regulating histone acetylation, HDACIs can inhibit the function of nonhistone effectors such as transcription factors to modulate gene expression.

In order to advance the compounds identified from a drug repurposing screen to potential clinical trials, the blood plasma concentration of the drug should be a few-fold higher than its IC50 value or similar to or below its IC90 value in the cells of the newly identified indication. We researched the human Cmax values of our most broadly potent compounds and compared them to the experimental IC90 values in this study. In most cases, our experimental IC90 is at or below the human plasma concentration, indicating that the effective drug concentration against the new indication is achievable in patients. Mocetinostat has a Cmax of approximately 21.4 μM at 10 mg/kg and 75.7 μM at 40 mg/kg in humans [52], while entinostat in humans reached a Cmax of 0.46 μM with 15 mg [53]. For mocetinostat, whose IC50 in our work was found to be 2.76 ± 1.98 μM, this indicates that the Cmax is well above its anticancer activity. For entinostat, however, although the patient Cmax is significantly lower than the average IC50 achieved in our study (7.11 ± 6.62 μM) for gynecologic cancers, its in vivo activity could possibly be achieved in higher doses or with compound structure-activity optimization. It is possible that the low toxicity of mocetinostat and entinostat is due to their specific HDAC isotype selectivity for certain HDACs. Both are class I HDAC inhibitors but exhibit varying IC50s for specific HDACs. For example, mocetinostat was found to inhibit only HDAC 1/2/3/11 at low micromolar potency or below [54]. On the other hand, entinostat exhibited submicromolar potency against HDAC 1/2/3 only [55]. Their similar isotype selectivity profiles correlate with their similar in vitro effects against gynecologic cancers in our study. This HDAC isotype selectivity may be related to the drugs' activity against the gynecologic cancer cell lines as HDAC 1/2/3 have been implicated in ovarian tumor malignancy and growth [56], while HDAC2 is overexpressed in cervical cancer carcinogenesis [57].

We also identified single cell line selective compounds with submicromolar potency and high selectivity for PA-1 (ovarian), TOV-21-G (ovarian), and HeLa (cervical), which could be due to their faster growth rates compared to other cancer cell lines and the cell cycle–interrupting nature of many compounds. Empirically, cells which cycle faster are more susceptible to interruptions of cell growth at different cycle stages [58]. However, certain drugs may act by disrupting specific cycle stage progression, i.e., G0 to G1 [59]. It is known that certain drugs are specific to certain phases. For example, 5-fluorouracil interrupts S phase by reducing thymidylate content for DNA synthesis [60], docetaxel interrupts M phase by preventing microtubule polymerization [61], [62], and seliciclib interrupts G1 phase by inhibiting CDKs 2/7/9 [63]. In this screen, PHA-793887 [64], a CDK2/1/4/9 inhibitor, was found to be potently toxic to PA-1 specifically, while milciclib [65], another CDK2 selective inhibitor, was specifically toxic to TOV-21-G with nanomolar potency. Both of these two CDK inhibitors suppress the cell growth phase.

The control cell line in this study, HEK 293T, is a normal human cell line originating from human embryonic kidney cells that is typically used as control cell line. The selectivity values determined in this study were relevant to the cytotoxicity of the compounds in HEK 293T cells. Given a different control line, the resulting selectivity may be different. The in vivo toxicity of compounds may also be different from the in vitro SI data. The selectivity reported here is for reference, and it should be noted that it cannot replace the data obtained from in vivo drug safety experiments and in clinical trials. We acknowledge the unequal numbers of lines for each cancer group (ovarian, cervical, and placental). Having fewer lines in one group will potentially increase the number of compounds that are pan-killers for that particular group. This is evident in the larger number of compounds that killed both placental lines as compared to the number of compounds that killed all six ovarian lines.

The results of this study warrant further investigation into the different responses cancers have to similar classes of compounds. Here, different HDAC inhibitors exhibit differential selectivity. This could possibly be due to differences in HDAC class specificity, with some inhibitors targeting class I HDACs preferentially to class II HDACs, for example [66]. Of the 19 compounds found to be pan-killers for all or some of the cancer groups, only three are FDA-approved drugs including Actinomycin D, nebupent [67], and cyclosporin A [68]. Of these, only Actinomycin D is an FDA-approved antineoplastic, while nebupent is an antifungal targeting Topoisomerase II and cyclosporin A is an immunosuppressant targeting calcineurin. Actinomycin D has been used as an alternative chemotherapeutic regimen for ovarian cancer [69] and GTD (placental cancer) [12]. As nebupent disrupts mitotic activities, it has been researched as an antineoplastic agent in vivo against adenocarcinomic human alveolar basal epithelial (A549 cells) and colorectal carcinoma (HCT116 cells) xenografts in combination with chlorpromazine [70] but is not used as an anticancer therapy in the clinic nor has it been used in the study of gynecologic cancer. Lastly, cyclosporin A showed no efficacy for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer in one Phase II trial [71]. In another trial studying drug-resistant gynecologic cancer, however, patients had an overall response rate of 29% after cyclosporin A treatment, and it was well tolerated [72]. Future work will seek to understand chemotherapeutic selectivity in more advanced models such as tumor spheroids, organoids, and in vivo xenograft models that could provide more physiologically relevant data on tumor killing.

Drug resistance to chemotherapy is a common cause for relapse and recurrence of many different types of cancers [73], [74]. Platinum resistance is a common form of drug resistance in ovarian cancer with several suspected underlying causes including CDK expression, Akt signaling, and EGFR expression [75], [76], [77]. Our group recently published a set of compounds that were able to overcome cisplatin resistance in several platinum-resistant ovarian cancer cell lines when given alone and in combination with cisplatin [78]. The newly identified compounds in this study against gynecologic cancers can be used to further study the drugs' synergistic effects with the SOC anticancer drugs. Therefore, some of our hits may be of interest in studying how to overcome drug resistance in ovarian, cervical, and placental cancers using the synergistic drug combination with the SOC anticancer drugs.

In conclusion, the compounds identified and confirmed in this drug repurposing screen and profiling can be used to further investigate their utility in the treatment of gynecological cancer, especially for multidrug-resistant cancer patients. We demonstrate here the variability and heterogeneous responses of gynecologic cancer cells to anticancer drugs that may be related to patient genetic background, age, intrinsic drug resistance, and cancer aggressiveness. Two HDAC inhibitors identified in this study, mocetinostat and entinostat, may have high clinical relevance and can be moved to clinical trials as bona fide gynecologic cancer therapeutics. Indeed, entinostat in combination with avelumab is already in Phase I/II clinical trials for epithelial ovarian cancer, peritoneal cancer, and fallopian tube cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02915523). Likewise, despite its toxicity to HEK 293T cells, panobinostat may be further studied in in vivo experiments due to its extremely high potency in gynecologic cancers. In conclusion, the chemotherapeutic profiling in individual cancer cells is an effective method to reveal the best anticancer therapeutics that might be particularly useful for those cancers with multidrug resistance, poor prognosis, and survival rates.

Methods

Reagents

DMEM (11965092), penicillin/streptomycin (15140163), and TrypLE (12605010) were purchased from Life Technologies. FBS (SH30071.03) was purchased from HyClone (SH30071.03). ATPlite (6016739) was purchased from Perkin Elmer.

Cell Lines

The following cell lines were purchased from ATCC: CAOV-3 (ovarian adenocarcinoma; HTB-75), SK-OV-3 (ovarian adenocarcinoma; HTB-77), SW 626 (ovarian adenocarcinoma; HTB-78), ES-2 (ovarian clear cell carcinoma; CRL-1978), PA-1 (ovarian teratocarcinoma; CRL-1572), TOV-21G (ovarian clear cell carcinoma; CRL-11730), HeLa (cervical adenocarcinoma; CCL-2), Ca ski (cervical epidermoid carcinoma; CRL-1550), C-33 A (cervical carcinoma; HTB-31), JAR (placental choriocarcinoma; HTB-144), JEG-3 (placental choriocarcinoma; HTB-36), and HEK 293T (embryonic kidney fibroblast; CRL-3216).

Cell Culture

Cells were kept in cryovials frozen at −150°C and thawed quickly in a 37°C water bath. A total of 1.5 million cells were seeded into T-225 flasks and subcultured once using TrypLE before freezing down for future experiments. For all assays, cells were seeded at 1000 cells per well into white, solid-bottom 1536-well plates using a Thermo Fisher Multidrop Combi reagent dispenser.

ATP Content Assay for Cell Viability, Growth Rate, and Positive Control Determination

The ATPlite luminescence assay system assay kit was used to determine cell viability. The reagent was reconstituted and prepared as described by the manufacturer. To measure the cell death caused by the compounds, cells were cultured in 4 μl of media for 16 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2 in assay plates, followed by the addition of DMSO or 16 SOC chemotherapeutic compounds dissolved in DMSO. SOC compounds were dosed at 11 concentrations (1:3 dilution) in quadruplicate from 57.5 μM to 0.977 nM using the automated Wako 1536 Pin Tool workstation and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24, 48, or 72 hours. Four microliters of ATPlite, the ATP monitoring reagent, was then added to each well of the assay plates using the Multidrop Combi reagent dispenser followed by incubation for 15 minutes at room temperature. The resulting luminescence was measured using the ViewLux plate reader. Data were normalized for each drug using the largest luminescence value as 100% full cell viability (0% cell killing) and to the smallest luminescence value 0% viability (100% cell killing).

Large-Scale Compound Screening and Follow-Up

A qHTS [79], in which each compound was assayed in five concentrations (0.092, 0.46, 2.3, 11.5, and 57.5 μM), was performed for the primary compound screen using the NPC [80] and NPACT drug libraries at NCATS. The OBGYN cancer and HEK 293T control cells were seeded into 1536-well assay plates at 1000 cells per 4 μl/well and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 hours. The ATPlite assay to determine the IC50 values for each compound was conducted as described above. Plates were processed on the fully integrated Kalypsys robotic system. Hits were selected from the primary screen for follow-up confirmation, dosed in triplicate at 11 concentrations (1:3 dilution) from 57.5 μM to 0.977 nM, and incubated for 48 hours, and the ATPlite assay was used to determine the IC50 values.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel, and figures were generated using Prism Graphpad 7.0. In-house qHTS data normalization, correction, curve fitting, and classification were performed using custom programs developed at NCATS [81], [82], [83]. All data presented as mean ± S.D. unless otherwise stated.

Data Availability Statement

Data have been submitted to Pubchem. Primary Screen AID: 1345084. Confirmatory Screen AID: 1345085.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Matt Hall and colleagues at NCATS for their contribution of the independent HEK 293T toxicity confirmation data. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (W.Z.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest or competing financial interests.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2018.11.016.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Figure 1. Assay development for qHTS screening of chemotherapeutic compounds. ATPlite luminescence from PA-1 ovarian teratocarcinoma cells treated with 10 compounds for 24 (A), 48 (B), and 72 hours (C) in dose-response format including SOC drugs used in the clinic. ATPlite luminescence from CAOV-3 ovarian adenocarcinoma cells treated with 16 compounds for 24 (D), 48 (E), and 72 hours (F) in dose-response format including SOC drugs used in the clinic. Data points representing normalized mean ± S.D. (n=4 wells per data point). Data were normalized to DMSO control (100% cell viability and lowest luminescence value among the 6 compounds (0% cell viability). Curves represent non-linear regression curve fit with variable slope.

Supplementary Figure 2. qHTS Assay Workflow for chemotherapeutic profiling of OBGYN cancer cell lines.

Supplementary Figure 3. HEK 293T control assay development. ATPlite luminescence from HEK 293T embryonic kidney fibroblasts cells treated with 10 compounds for 24 (A), 48 (B), and 72 hours (C) in dose-response format including SOC drugs used in the clinic. (D) Doxorubicin time course dose-response cell viability curves for PA-1 cells from A, B, and C with IC50 determinations in the inset. (E) Curcubitacin B time course dose-response curves for PA-1 cells from A, B, and C with IC50 determinations in the inset. (F) Log (selectivity index) heat map calculated using the 48-hour time point IC50 values for HEK 293T cells divided by the IC50 values for PA1 and CAOV-3 cells. Table is organized according to the most selective to the least selective compounds. Black panels indicate that no IC50 could be determined from the linear regression curve fit. (G) Chemical structure of doxorubicin. (H) Chemical structure of curcubitacin B. Data points representing normalized mean ± S.D. (n=4 wells per data point). Data were normalized to DMSO control (100% cell viability and lowest luminescence value among the 16 compounds (0% cell viability). Curves represent nonlinear regression curve fit with variable slope.

Supplementary Figure 3. Comparison of IC50 and efficacy values for eight toxic compounds. The eight compounds in this dataset were filtered with the following dose-response parameters: efficacy >70% and IC50 <30 μM in all of the cell lines in addition to having toxicity in HEK293T >50%. (A) Comparison of CCL (circles) and HEK293T (triangles) average IC50 (μM) vs. average efficacy (%) along with linear regression curves and the 95% CI. (B) Efficacy values of eight toxic compounds for each cancer cell line shown as box and whisker plots, with the box representing the upper 25% and lower 75%, the middle line representing the median, the “+” representing the mean, and the whiskers representing the 5 and 95 percentiles. Outliers above 95 and below 5 percentile range shown as circles. (C) IC50 (log, M) of eight toxic compounds for each cancer cell line shown as box and whisker plots, with the box representing the upper 25% and lower 75%, the middle line representing the median, the “+” representing the mean, and the whiskers representing the 5 and 95 percentiles. Outliers above 95 and below 5 percentile range shown as circles. (d) The IC50 (μM) (red circles) and efficacy (%) (black circles) shown for each compound sorted from the largest to smallest response.

Supplementary Figure 4. Two representative compounds with toxicity in all cell lines. Chemical structures and dose-response curves for (A) panobinostat and (E) givinostat, respectively, for (B, F) cervical, (C, G) ovarian, and (D, H) placental cancer cell lines. See Table 2 for the full list of effective compounds toxic to all cell lines.

Supplementary Figure 5. Confirmation of compound toxicity in HEK293T. (A) Comparison of IC50 (log, M) and (B) efficacy (%) values for compounds toxic to all cell lines between two independent screens. Primary and secondary assays used ATPlite. Confirmation assay used CellTiterGlo. Missing values in A were compounds not present in the CellTiter Glo confirmation screen drug library.

Supplementary Figure 6. Ovarian and placental cancer killers. Chemical structures and dose-response curves for (A) actinomycin D and (E) TG-101348, respectively, for (B, F) cervical, (C, G) ovarian, and (D, H) placental cancer cell lines. See Table 4 for the full list of the best compounds from the confirmation screen.

Supplementary Figure 7. Ovarian and cervical cancer killers. Chemical structures and dose-response curves for (A) TG-89 and (E) CCT137690, respectively, for (B, F) cervical, (C, G) ovarian, and (D, H) placental cancer cell lines. See Table 4 for the full list of the best compounds from the confirmation screen.

Supplementary Figure 8. Cancer group selective cancer killers. Chemical structure and dose-response curves for representative ovarian cancer killer (A) fostamitinib and placental cancer killer (E) nebupent for (B, F) cervical, (C, G) ovarian, and (D, H) placental cancer cell lines. See Table 4 for the full list of the best compounds from the confirmation screen.

Supplementary Figure 9. Subnanomolar compound diversity among different cancer types. (A) Bar graph depicting each cell line with the number of nanomolar compounds with greater than 70% efficacy. (B) Bar graph depicting the number of cell lines killed by compounds with <1 nM IC50.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller K, Jamal A. American Cancer Society; 2018. Cancer Facts and Figures 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123(6):1044–1050. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J, Naumann RW, Seckl MJ, Schink J. 15 years of progress in gestational trophoblastic disease: Scoring, standardization, and salvage. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144(1):200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.08.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seckl MJ, Sebire NJ, Berkowitz RS. Gestational trophoblastic disease. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):717–729. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sablinska B, Kietlinska Z, Zielinski J. Chemotherapy combined with surgery in the treatment of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1993;14(Suppl):146–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murai J. Targeting DNA repair and replication stress in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017;22(4):619–628. doi: 10.1007/s10147-017-1145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monk BJ, Minion LE, Coleman RL. Anti-angiogenic agents in ovarian cancer: past, present, and future. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl_1):i33–i39. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helm CW, States JC. Enhancing the efficacy of cisplatin in ovarian cancer treatment - could arsenic have a role. J Ovarian Res. 2009;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan F, Everard J, Ahmed S, Coleman RE, Aitken M, Hancock BW. Low-risk persistent gestational trophoblastic disease treated with low-dose methotrexate: efficacy, acute and long-term effects. J Cancer. 2003;89(12):2197–2201. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alazzam M, Tidy J, Osborne R, Coleman R, Hancock BW, Lawrie TA. Chemotherapy for resistant or recurrent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008891.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng L, Zhang J, T Wu, Lawrie TA. Combination chemotherapy for primary treatment of high-risk gestational trophoblastic tumour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005196.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pakish JB, Jazaeri AA. Immunotherapy in gynecologic cancers: are we there yet? Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18(10):59. doi: 10.1007/s11864-017-0504-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sjoquist KM, Martyn J, Edmondson RJ, Friedlander ML. The role of hormonal therapy in gynecological cancers-current status and future directions. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(7):1328–1333. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821d6021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badisa RB, Darling-Reed SF, Joseph P, Cooperwood JS, Latinwo LM, Goodman CB. Selective cytotoxic activities of two novel synthetic drugs on human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(8):2993–2996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Naggar NE-A, Deraz SF, Soliman HM, El-Deeb NM, El-Ewasy SM. Purification, characterization, cytotoxicity and anticancer activities of L-asparaginase, anti-colon cancer protein, from the newly isolated alkaliphilic Streptomyces fradiae NEAE-82. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32926. doi: 10.1038/srep32926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Lazaro M. Two preclinical tests to evaluate anticancer activity and to help validate drug candidates for clinical trials. Oncoscience. 2015;2(2):91–98. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaushik U, Aeri V, Mir SR. Cucurbitacins — an insight into medicinal leads from nature. Pharmacognosy Rev. 2015;9(17):12–18. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.156314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Veggel M, Westerman E, Hamberg P. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of panobinostat. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;57(1):21–29. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0565-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganai SA. Histone deacetylase inhibitor givinostat: the small-molecule with promising activity against therapeutically challenging haematological malignancies. J Chemother. 2016;28(4):247–254. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2016.1145375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldman D, Koong AC. Irestatin, a potent inhibitor of IRE1α and the unfolded protein response, is a hypoxia-selective cytotoxin and impairs tumor growth. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18_suppl):3514. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baumann P, Schneider L, Mandl-Weber S, Oduncu F, Schmidmaier R. Simultaneous targeting of PI3K and mTOR with NVP-BGT226 is highly effective in multiple myeloma. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2012;23(1):131–138. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32834c8683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwamoto M, Friedman EJ, Sandhu P, Agrawal NG, Rubin EH, Wagner JA. Clinical pharmacology profile of vorinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;72(3):493–508. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2220-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pardanani A, Hood J, Lasho T, Levine RL, Martin MB, Noronha G, Finke C, Mak CC, Mesa R, Zhu H. TG101209, a small molecule JAK2-selective kinase inhibitor potently inhibits myeloproliferative disorder-associated JAK2V617F and MPLW515L/K mutations. Leukemia. 2007;21(8):1658–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye S, Zhang J, Shen J, Gao Y, Li Y, Choy E, Cote G, Harmon D, Mankin H, Gray NS. NVP-TAE684 reverses multidrug resistance (MDR) in human osteosarcoma by inhibiting P-glycoprotein (PGP1) function. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(3):613–626. doi: 10.1111/bph.13395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wehrle J, von Bubnoff N. Ponatinib: a third-generation inhibitor for the treatment of CML. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2018;212:109–118. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-91439-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boumber Y, Younes A, Garcia-Manero G. Mocetinostat (MGCD0103): a review of an isotype-specific histone deacetylase inhibitor. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20(6):823–829. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.577737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briere D, Sudhakar N, Woods DM, Hallin J, Engstrom LD, Aranda R, Chiang H, Sodre AL, Olson P, Weber JS. The class I/IV HDAC inhibitor mocetinostat increases tumor antigen presentation, decreases immune suppressive cell types and augments checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67(3):381–392. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2091-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Batlevi CL, Crump M, Andreadis C, Rizzieri D, Assouline SE, Fox S, van der Jagt RHC, Copeland A, Potvin D, Chao R. A phase 2 study of mocetinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2017;178(3):434–441. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trapani D, Esposito A, Criscitiello C, Mazzarella L, Locatelli M, Minchella I, Minucci S, Curigliano G. Entinostat for the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26(8):965–971. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1353077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connolly RM, Rudek MA, Piekarz R. Entinostat: a promising treatment option for patients with advanced breast cancer. Future Oncol. 2017;13(13):1137–1148. doi: 10.2217/fon-2016-0526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawrie TA, Alazzam M, Tidy J, Hancock BW, Osborne R. First-line chemotherapy in low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007102.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison CN, Schaap N, Vannucchi AM, Kiladjian JJ, Tiu RV, Zachee P, Jourdan E, Winton E, Silver RT, Schouten HC. Janus kinase-2 inhibitor fedratinib in patients with myelofibrosis previously treated with ruxolitinib (JAKARTA-2): a single-arm, open-label, non-randomised, phase 2, multicentre study. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(7):e317–e324. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30088-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.X Wu, Liu W, Cao Q, Chen C, Chen Z, Xu Z, Li W, Liu F, Yao X. Inhibition of Aurora B by CCT137690 sensitizes colorectal cells to radiotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2014;33:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-33-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bussel J, Arnold DM, Grossbard E, Mayer J, Trelinski J, Homenda W, Hellmann A, Windyga J, Sivcheva L, Khalafallah AA. Fostamatinib for the treatment of adult persistent and chronic immune thrombocytopenia: results of two phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(7):921–930. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeong Y, You D, Kang HG, Yu J, Kim SW, Nam SJ, Lee JE, Kim S. Berberine suppresses fibronectin expression through inhibition of c-Jun phosphorylation in breast cancer cells. J Breast Cancer. 2018;21(1):21–27. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2018.21.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong H, Wang N, Zhao L, Lu F. Berberine in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:591654. doi: 10.1155/2012/591654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aghazadeh S, Yazdanparast R. Mycophenolic acid potentiates HER2-overexpressing SKBR3 breast cancer cell line to induce apoptosis: involvement of AKT/FOXO1 and JAK2/STAT3 pathways. Apoptosis. 2016;21(11):1302–1314. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh H, Walker AJ, Amiri-Kordestani L, Cheng J, Tang S, Balcazar P, Barnett-Ringgold K, Palmby TR, Cao X, Zheng N. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval: neratinib for the extended adjuvant treatment of early stage HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(15):3486–3491. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss GJ, Hidalgo M, Borad MJ, Laheru D, Tibes R, Ramanathan RK, Blaydorn L, Jameson G, Jimeno A, Isaacs JD. Phase I study of the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of PHA-848125AC, a dual tropomyosin receptor kinase A and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Investig New Drugs. 2012;30(6):2334–2343. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9774-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michael M, Bang YJ, Park YS, Kang YK, Kim TM, Hamid O, Thornton D, Tate SC, Raddad E, Tie J. A phase 1 study of LY2874455, an oral selective pan-FGFR Inhibitor, in patients with advanced cancer. Target Oncol. 2017;12(4):463–474. doi: 10.1007/s11523-017-0502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clive S, Woo MM, Nydam T, Kelly L, Squier M, Kagan M. Characterizing the disposition, metabolism, and excretion of an orally active pan-deacetylase inhibitor, panobinostat, via trace radiolabeled 14C material in advanced cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;70(4):513–522. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1940-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma S, Beck J, Mita M, Paul S, Woo MM, Squier M, Gadbaw B, Prince HM. A phase I dose-escalation study of intravenous panobinostat in patients with lymphoma and solid tumors. Investig New Drugs. 2013;31(4):974–985. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-9930-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moreau P, Karamanesht II, Domnikova N, Kyselyova MY, Vilchevska KV, Doronin VA, Schmidt A, Hulin C, Leleu X, Esseltine D-L. Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and covariate analysis of subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012;51(12):823–829. doi: 10.1007/s40262-012-0010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berkenblit A, Eder JP, Ryan DP, Seiden MV, Tatsuta N, Sherman ML, Dahl TA, Dezube BJ, Supko JG. Phase I clinical trial of STA-4783 in combination with paclitaxel in patients with refractory solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(2):584–590. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hill CR, Cole M, Errington J, Malik G, Boddy AV, Veal GJ. Characterisation of the clinical pharmacokinetics of actinomycin D and the influence of ABCB1 pharmacogenetic variation on actinomycin D disposition in children with cancer. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53(8):741–751. doi: 10.1007/s40262-014-0153-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veal GJ, Cole M, Errington J, Parry A, Hale J, Pearson AD, Howe K, Chisholm JC, Beane C, Brennan B. Pharmacokinetics of dactinomycin in a pediatric patient population: a United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(16):5893–5899. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), C.f.D.C.a.P Trends in death rates, 1930-2015. 2017 https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/?_ga=2.252081025.961278796.1525193503-1241373617.1524667388#!/data-analysis/module/5UNvg1gE?type=lineGraph Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 49.Institute, N.C . 2017. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 9 registries. [cited 2018 05–02] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suraweera A, O'Byrne KJ, Richard DJ. Combination therapy with histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) for the treatment of cancer: achieving the full therapeutic potential of HDACi. Front Oncol. 2018;8:92. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feinberg AP. The key role of epigenetics in human disease prevention and mitigation. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(14):1323–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spence S, Deurinck M, H Ju, Traebert M, McLean L, Marlowe J, Emotte C, Tritto E, Tseng M, Shultz M. Histone deacetylase inhibitors prolong cardiac repolarization through transcriptional mechanisms. Toxicol Sci. 2016;153(1):39–54. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Batlevi CL, Kasamon Y, Bociek RG, Lee P, Gore L, Copeland A, Sorensen R, Ordentlich P, Cruickshank S, Kunkel L. ENGAGE- 501: phase 2 study of entinostat (SNDX-275) in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Haematologica. 2016;101(8):968–975. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.142406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fournel M, Bonfils C, Hou Y, Yan PT, Trachy-Bourget M-C, Kalita A, Liu J, Lu A-H, Zhou NZ, Robert M-F. MGCD0103, a novel isotype-selective histone deacetylase inhibitor, has broad spectrum antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(4):759. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lauffer BE, Mintzer R, Fong R, Mukund S, Tam C, Zilberleyb I, Flicke B, Ritscher A, Fedorowicz G, Vallero R. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor kinetic rate constants correlate with cellular histone acetylation but not transcription and cell viability. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(37):26926–26943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.490706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayashi A, Horiuchi A, Kikuchi N, Hayashi T, Fuseya C, Suzuki A, Konishi I, Shiozawa T. Type-specific roles of histone deacetylase (HDAC) overexpression in ovarian carcinoma: HDAC1 enhances cell proliferation and HDAC3 stimulates cell migration with downregulation of E-cadherin. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(6):1332–1346. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang BH, Laban M, Leung CHW, Lee L, Lee CK, Salto-Tellez M, Raju GC, Hooi SC. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 2 increases apoptosis and p21Cip1/WAF1 expression, independent of histone deacetylase 1. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:395. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.West J, Newton PK. Optimizing chemo-scheduling based on tumor growth rates. bioRxiv. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Otto T, Sicinski P. Cell cycle proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(2):93–115. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Focaccetti C, Bruno A, Magnani E, Bartolini D, Principi E, Dallaglio K, Bucci EO, Finzi G, Sessa F, Noonan DM. Effects of 5-fluorouracil on morphology, cell cycle, proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy and ROS production in endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2015;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115686. 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hennequin C, Giocanti N, Favaudon V. S-phase specificity of cell killing by docetaxel (Taxotere) in synchronised HeLa cells. Br J Cancer. 1995;71(6):1194–1198. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hernandez-Vargas H, Palacios J, Moreno-Bueno G. Telling cells how to die: docetaxel therapy in cancer cell lines. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(7):780–783. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.7.4050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khalil HS, Mitev V, Vlaykova T, Cavicchi L, Zhelev N. Discovery and development of seliciclib. How systems biology approaches can lead to better drug performance. J Biotechnol. 2015;202:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brasca MG, Albanese C, Alzani R, Amici R, Avanzi N, Ballinari D, Bischoff J, Borghi D, Casale E, Croci V. Optimization of 6,6-dimethyl pyrrolo[3,4-c]pyrazoles: Identification of PHA-793887, a potent CDK inhibitor suitable for intravenous dosing. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18(5):1844–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brasca MG, Amboldi N, Ballinari D, Cameron A, Casale E, Cervi G, Colombo M, Colotta F, Croci V, D'Alessio R. Identification of N,1,4,4-tetramethyl-8-{[4-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl]amino}-4,5-dihydro-1H-py razolo[4,3-h]quinazoline-3-carboxamide (PHA-848125), a potent, orally available cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2009;52(16):5152–5163. doi: 10.1021/jm9006559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roche J, Bertrand P. Inside HDACs with more selective HDAC inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2016;121:451–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sweiss K, Anderson J, Wirth S, Oh A, Quigley JG, Khan I, Saraf S, Haaf Mactal- C, Rondelli D, Patel P. A prospective study of intravenous pentamidine for PJP prophylaxis in adult patients undergoing intensive chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(3):300–306. doi: 10.1038/s41409-017-0024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beauchesne PR, Chung NS, Wasan KM. Cyclosporine A: a review of current oral and intravenous delivery systems. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2007;33(3):211–220. doi: 10.1080/03639040601155665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ray-Coquard I, Morice P, Lorusso D, Prat J, Oaknin A, Pautier P. Non-epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;23(7):20–26. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee MS, Johansen L, Zhang Y, Wilson A, Keegan M, Avery W, Elliott P, Borisy AA, Keith CT. The novel combination of chlorpromazine and pentamidine exerts synergistic antiproliferative effects through dual mitotic action. Cancer Res. 2007;67(23) doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manetta A, Blessing JA, Hurteau JA. Evaluation of cisplatin and cyclosporin A in recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer: a phase II study of the gynecologic oncology group. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;68(1):45–46. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sood AK, Sorosky JI, Squatrito RC, Skilling JS, Anderson B, Buller RE. Cyclosporin A reverses chemoresistance in patients with gynecologic malignancies. Neoplasia. 1999;1(2):118–122. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Housman G, Byler S, Heerboth S, Lapinska K, Longacre M, Snyder N, Sarkar S. Drug resistance in cancer: an overview. Cancer. 2014;6(3):1769–1792. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gottesman MM. Mechanisms of cancer drug resistance. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:615–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guffanti F, Fratelli M, Ganzinelli M, Bolis M, Ricci F, Bizzaro F, Chila R, Sina FP, Fruscio R, Lupia M. Platinum sensitivity and DNA repair in a recently established panel of patient-derived ovarian carcinoma xenografts. Oncotarget. 2018;9(37):24707–24717. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kawaguchi H, Terai Y, Tanabe A, Sasaki H, Takai M, Fujiwara S, Ashihara K, Tanaka Y, Tanaka T, Tsunetoh S. Gemcitabine as a molecular targeting agent that blocks the Akt cascade in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2014;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Satpathy M, Mezencev R, Wang L, McDonald JF. Targeted in vivo delivery of EGFR siRNA inhibits ovarian cancer growth and enhances drug sensitivity. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep36518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sima N, Sun W, Gorshkov K, Shen M, Huang W, Zhu W, Xie X, Zheng W, Cheng X. Small molecules identified from a quantitative drug combinational screen resensitize cisplatin's response in drug-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Transl Oncol. 2018;11(4):1053–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Inglese J, Auld DS, Jadhav A, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, Yasgar A, Zheng W, Austin CP. Quantitative high-throughput screening: a titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(31):11473–11478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang BH, Laban M, Leung CHW, Lee L, Lee CK, Salto-Tellez M, Raju GC, Hooi SC. The NCGC pharmaceutical collection: a comprehensive resource of clinically approved drugs enabling repurposing and chemical genomics. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(80) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Southall NT. In: Enabling the large scale analysis of quantitative high throughput screening data, in Handbook of Drug Screening. Seethala R, Zhang L, editors. Taylor and Francis; New York: 2009. pp. 442–463. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang Y, Huang R. In: Correction of microplate data from high throughput screening, in High-Throughput Screening Assays in Toxicology. Zhu H, Xia M, editors. Humana Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang Y, Jadhav A, Southall N, Huang R, Nguyen D-T. A grid algorithm for high throughput fitting of dose-response curve data. Curr Chem Genomics. 2010;4:57–66. doi: 10.2174/1875397301004010057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee OW, Austin SM, Gamma MR, Cheff DM, Lee DT, Wilson KM, Johnson JM, Travers JC, Braisted JC, Guha R. bioRxiv; 2018. Cytotoxic Profiling of Annotated and Diverse Chemical Libraries Using Quantitative High-Throughput Screening. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gallerani E, Zucchetti M, Brunelli D, Marangon E, Noberasco C, Hess D, Delmonte A, Martinelli G, Bohm S, Driessen C. A first in human phase I study of the proteasome inhibitor CEP-18770 in patients with advanced solid tumours and multiple myeloma. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(2):290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mross K, Frost A, Steinbild S, Hedbom S, Rentschler J, Kaiser R, Rouyrre N, Trommeshauser D, Hoesl CE, Munzert G. Phase I Dose escalation and pharmacokinetic study of BI 2536, a novel polo-like kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(34):5511–5517. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Satoh T, Yasui H, Muro K, Komatsu Y, Sameshima S, Yamaguchi K, Sugihara K. Pharmacokinetic assessment of irinotecan, SN-38, and SN-38-glucuronide: a substudy of the FIRIS Study. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(9):3845–3853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shapiro GI, Bell-McGuinn KM, Molina JR, Bendell J, Spicer J, Kwak EL, Pandya SS, Millham R, Borzillo G, Pierce KJ. First-in-human study of PF-05212384 (PKI-587), a small-molecule, intravenous, dual inhibitor of PI3K and mTOR in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(8):1888–1895. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Frapolli R, Zucchetti M, Sessa C, Marsoni S, Viganò L, Locatelli A, Rulli E, Compagnoni A, Bello E, Pisano C. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the new oral camptothecin gimatecan: the inter-patient variability is related to alpha1-acid glycoprotein plasma levels. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(3):505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kobayashi Y, Yamauchi T, Kiyoi H, Sakura T, Hata T, Ando K, Watabe A, Harada A, Taube T, Miyazaki Y. Phase I trial of volasertib, a Polo-like kinase inhibitor, in Japanese patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Sci. 2015;106(11):1590–1595. doi: 10.1111/cas.12814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Assay development for qHTS screening of chemotherapeutic compounds. ATPlite luminescence from PA-1 ovarian teratocarcinoma cells treated with 10 compounds for 24 (A), 48 (B), and 72 hours (C) in dose-response format including SOC drugs used in the clinic. ATPlite luminescence from CAOV-3 ovarian adenocarcinoma cells treated with 16 compounds for 24 (D), 48 (E), and 72 hours (F) in dose-response format including SOC drugs used in the clinic. Data points representing normalized mean ± S.D. (n=4 wells per data point). Data were normalized to DMSO control (100% cell viability and lowest luminescence value among the 6 compounds (0% cell viability). Curves represent non-linear regression curve fit with variable slope.

Supplementary Figure 2. qHTS Assay Workflow for chemotherapeutic profiling of OBGYN cancer cell lines.

Supplementary Figure 3. HEK 293T control assay development. ATPlite luminescence from HEK 293T embryonic kidney fibroblasts cells treated with 10 compounds for 24 (A), 48 (B), and 72 hours (C) in dose-response format including SOC drugs used in the clinic. (D) Doxorubicin time course dose-response cell viability curves for PA-1 cells from A, B, and C with IC50 determinations in the inset. (E) Curcubitacin B time course dose-response curves for PA-1 cells from A, B, and C with IC50 determinations in the inset. (F) Log (selectivity index) heat map calculated using the 48-hour time point IC50 values for HEK 293T cells divided by the IC50 values for PA1 and CAOV-3 cells. Table is organized according to the most selective to the least selective compounds. Black panels indicate that no IC50 could be determined from the linear regression curve fit. (G) Chemical structure of doxorubicin. (H) Chemical structure of curcubitacin B. Data points representing normalized mean ± S.D. (n=4 wells per data point). Data were normalized to DMSO control (100% cell viability and lowest luminescence value among the 16 compounds (0% cell viability). Curves represent nonlinear regression curve fit with variable slope.

Supplementary Figure 3. Comparison of IC50 and efficacy values for eight toxic compounds. The eight compounds in this dataset were filtered with the following dose-response parameters: efficacy >70% and IC50 <30 μM in all of the cell lines in addition to having toxicity in HEK293T >50%. (A) Comparison of CCL (circles) and HEK293T (triangles) average IC50 (μM) vs. average efficacy (%) along with linear regression curves and the 95% CI. (B) Efficacy values of eight toxic compounds for each cancer cell line shown as box and whisker plots, with the box representing the upper 25% and lower 75%, the middle line representing the median, the “+” representing the mean, and the whiskers representing the 5 and 95 percentiles. Outliers above 95 and below 5 percentile range shown as circles. (C) IC50 (log, M) of eight toxic compounds for each cancer cell line shown as box and whisker plots, with the box representing the upper 25% and lower 75%, the middle line representing the median, the “+” representing the mean, and the whiskers representing the 5 and 95 percentiles. Outliers above 95 and below 5 percentile range shown as circles. (d) The IC50 (μM) (red circles) and efficacy (%) (black circles) shown for each compound sorted from the largest to smallest response.

Supplementary Figure 4. Two representative compounds with toxicity in all cell lines. Chemical structures and dose-response curves for (A) panobinostat and (E) givinostat, respectively, for (B, F) cervical, (C, G) ovarian, and (D, H) placental cancer cell lines. See Table 2 for the full list of effective compounds toxic to all cell lines.

Supplementary Figure 5. Confirmation of compound toxicity in HEK293T. (A) Comparison of IC50 (log, M) and (B) efficacy (%) values for compounds toxic to all cell lines between two independent screens. Primary and secondary assays used ATPlite. Confirmation assay used CellTiterGlo. Missing values in A were compounds not present in the CellTiter Glo confirmation screen drug library.

Supplementary Figure 6. Ovarian and placental cancer killers. Chemical structures and dose-response curves for (A) actinomycin D and (E) TG-101348, respectively, for (B, F) cervical, (C, G) ovarian, and (D, H) placental cancer cell lines. See Table 4 for the full list of the best compounds from the confirmation screen.

Supplementary Figure 7. Ovarian and cervical cancer killers. Chemical structures and dose-response curves for (A) TG-89 and (E) CCT137690, respectively, for (B, F) cervical, (C, G) ovarian, and (D, H) placental cancer cell lines. See Table 4 for the full list of the best compounds from the confirmation screen.

Supplementary Figure 8. Cancer group selective cancer killers. Chemical structure and dose-response curves for representative ovarian cancer killer (A) fostamitinib and placental cancer killer (E) nebupent for (B, F) cervical, (C, G) ovarian, and (D, H) placental cancer cell lines. See Table 4 for the full list of the best compounds from the confirmation screen.

Supplementary Figure 9. Subnanomolar compound diversity among different cancer types. (A) Bar graph depicting each cell line with the number of nanomolar compounds with greater than 70% efficacy. (B) Bar graph depicting the number of cell lines killed by compounds with <1 nM IC50.

Data Availability Statement

Data have been submitted to Pubchem. Primary Screen AID: 1345084. Confirmatory Screen AID: 1345085.