Abstract

Introduction

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) guidelines integrate evidence-based practices into multimodal care pathways designed to optimise patient recovery following surgery. The objective of this project is to create an ERAS protocol for neonatal abdominal surgery. The protocol will identify and attempt to bridge the gaps between current practices and best evidence. Our study is the first paediatric ERAS protocol endorsed by the International ERAS Society.

Methods

A research team consisting of international clinical and family stakeholders as well as methodological experts have iteratively defined the scope of the protocol in addition to individual topic areas. A modified Delphi method was used to reach consensus. The second phase will include a series of knowledge syntheses involving a rapid review coupled with expert opinion. Potential protocol elements supported by synthesised evidence will be identified. The Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system will be used to determine strength of recommendations and the quality of evidence. The third phase will involve creation of the protocol using a modified RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Group consensus will be used to rate each element in relation to the quality of evidence supporting the recommendation and the appropriateness for guideline inclusion. This protocol will form the basis of a future implementation study.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been registered with the ERAS Society. Human ethics approval (REB 18–0579) is in place to engage patient families within protocol development. This research is to be published in peer-reviewed journals and will form the care standard for neonatal intestinal surgery.

Keywords: paediatric surgery, eras

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This protocol outlines the development of the first paediatric Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) guideline with unique areas of topic development, for example, parental involvement.

The aims and targets of this study were developed by an international panel of experts and stakeholders including parents.

The methods include systematic literature reviews and evaluation, offering a potential standard for future ERAS guideline generation informed by robust methodology.

This study has integrated knowledge translation through endorsement and ongoing engagement with the International ERAS Society.

Several care pathway elements will have little evidence or evidence of low quality.

Introduction

Background

The care of children undergoing surgery presents physiological and sociological challenges that are different from those encountered in the care of adults. Neonates constitute a particularly complex patient population due to small blood volume, temperature instability, immature immune systems, nutritional needs for growth and healing and the inability to verbally communicate among others.1 Furthermore, there is considerable variability in perioperative care in neonatal surgery, which is believed to contribute to adverse outcomes.2 3

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) guidelines are innovative tools differing from other evidence-based guidelines as they encompass multiple aspects of patient care in the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative periods, are used by a multidisciplinary care team and have strong implementation frameworks. The holistic approach of ERAS protocols in multiple subspecialties such as colorectal and other intra-abdominal surgical specialties have been shown to improve health outcomes by decreasing complications and length of stay (LOS), translating to a reduction in healthcare costs.1 4–8

There have been few attempts to introduce ERAS into the paediatric surgical setting, none of which have been designed for the neonatal population.9 10

Audit is an important component of any ERAS programme. Using a tailored database (eg, RedCap) or the ERAS Interactive Audit System, teams review their compliance to the ERAS guideline recommendations during the preimplementation phase and then iterate towards improved compliance. This iterative cycle translates to improved clinical outcomes.11

The ERAS Society adopts evidence-based practices by integrating perioperative interventions for optimal patient recovery following a surgical procedure. We have developed our approach in partnership with the ERAS Society as well as family and clinician stakeholders.

Relevance

Intestinal obstruction in a newborn is a frequent indication for surgical intervention with an estimated incidence of neonatal intestinal obstruction of 1:1500 live births. Neonatal patients undergoing surgery are at high risk of surgical site infections (SSIs), with an observed SSI incidence rate of 4% in clean surgeries and a rate as high as 19% in dirty surgeries.12 Complications such as SSIs lead to increased length of stay and impairment of growth and development.13 In addition, two-thirds of neonatal patients undergoing intestinal resection are likely to require unanticipated reoperation within a year of their initial surgery.14 Our team has recognised that these adverse outcomes likely represent a knowledge-to-action gap in the surgical care of these newborns. This study will address the gap by synthesising the current evidence on best practices surrounding neonatal abdominal surgery and devise a comprehensive ERAS guideline that is designed to reduce the need for reoperation and enhance the overall quality, efficiency and safety of care for this fragile patient population while increasing parent satisfaction.

Anticipated impact

The development of an ERAS guideline has the potential to translate the benefits of protocolised care seen in the adult population to the vulnerable neonatal population as well as identify key knowledge gaps that must be addressed to further improve care. The evidence-based guideline resulting from this research will be implemented in a pilot study in the care of neonatal patients undergoing abdominal surgery at the Alberta Children’s Hospital in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Roughly 10% of neonatal surgical patients suffer at least one postoperative adverse event in Canada.15 Compliance with ERAS guideline elements will be measured prospectively and attitudes and acceptability of the guideline will be measured through clinician and parent surveys and interviews. Secondary measures will include clinical outcomes, such as nutritional outcomes, complication rates and length of stay, that will be compared within a time series analysis during ERAS guideline implementation. Data derived from the pilot study will be used to refine the neonatal ERAS guideline and develop an international trial to evaluate the impact of this guideline on clinical outcomes and measures of resource utilisation.

Objectives

This project aims to create an ERAS guideline that will reduce adverse events, enhance quality of care, increase parent satisfaction and improve the efficiency of neonatal surgical healthcare delivery.

Methods and analysis

Establishment of a multidisciplinary team

This research represents a collaborative effort between a core research team, an international guideline committee and a group of subject matter experts. Dr Mary Brindle, director of the Efficiency, Quality, Innovation and Safety (EQuIS) research platform, supports this project in partnership with Dr Gregg Nelson, secretary of the International ERAS Society. The EQuIS research group is dedicated to improving the quality of care delivered to paediatric surgical patients in Calgary, in Canada and internationally.

The international guideline committee consists of a multidisciplinary international panel of individuals involved in the surgical care of neonates, with representation from Canada, USA, Sweden, UK and China. Panel selections were based on clinical expertise, expertise in knowledge synthesis and expertise in ERAS methods. The international guideline committee is composed of the following: Megan A Brockel, MD, Paediatric Anesthesiologist, USA; David DeBeer, Consultant Paediatric Anaesthetist, UK; Martin Offringa, MD, PhD, Neonatologist, Canada; Mehul V Raval, MD, MS, Paediatric Surgeon, USA; Erik Skarsgard, MD, MSc, Paediatric Surgeon, Canada; Paul Wales, MD, MSc, Paediatric Surgeon, Canada; Tomas Wester, MD, PhD, Paediatric Surgeon, Sweden; and Kenneth Wong, MD, PhD, Paediatric Surgeon, China. Subject matter experts represent the areas of nutritional care, physiotherapy/occupational therapy and nursing. Parent representatives will be involved in the framing of recommendations and the design of implementation strategies post tool development.

Study design

This study involves knowledge synthesis, quality assessment and expert consensus to generate an international ERAS guideline. Knowledge synthesis will be performed using rapid literature review and snowballing to synthesise the current evidence base supporting various elements of neonatal perioperative care. The most relevant research evidence will be summarised, and the quality of the evidence will be evaluated. The resulting synthesis will be used to generate evidence-supported recommendations. These recommendations will be assessed for ERAS guideline inclusion through group consensus including broad stakeholder involvement and following clearly established principles. These final recommendations will take the form of an ERAS guideline. This ERAS guideline and its implementation strategy will be assessed for clinical effectiveness within a future pilot trial at Alberta Children’s Hospital (ACH). The results from this trial will be used to further adapt the care pathway and implementation strategy for an ERAS Society supported international trial.

Scope determination

The international panel was invited to attend as many as three International ERAS Neonatal Teleconferences to define the scope and topics for the guideline. All members attended at least one teleconference. Two of these teleconferences occurred in June of 2017 and one in July of 2017. Teleconferences were moderated by the senior leader (MEB). The opinion of all participants was obtained. The three areas for discussion included the scope of the target population, the scope of the conditions for inclusion and the general list of topics for consideration as ERAS elements. Final decisions on scope and topics were made in an iterative fashion based on majority consensus and total group agreement. Detailed field notes were compiled for each session.

A modified Delphi method was used to reach consensus for topic inclusion within each area of inquiry by10n panellists. Each panellist was sent an email survey regarding target population, conditions and topics and was asked to rate the ‘Agreement of Inclusion into Guideline’ based on a nine-point scale where nine was completely agree and one was completely disagree. ERAS topics that had an overall median panel score of greater or equal to seven were included. Topics with a score of 1–3 were excluded. Topics with a score between 4 and 6 were further discussed within the group and decision for inclusion was based on group consensus.

The final target population determined was the term neonate defined as an infant born at or after 37 weeks without major comorbidity undergoing intestinal surgery within the first 4 weeks of life. All 10 panellists agreed on this definition (eight rating 9/9, one rating 8/9 and one rating 7/9). Residual areas for further consideration included the definition of major comorbidity. The final decision of the group was that intestinal resections including stomas in term neonates would be considered for inclusion. All 10 panellists agreed on this (seven rating 9/9, two rating 8/9 and one rating 7/9).

Based on previous ERAS literature supplemented with expert opinion, a working list of perioperative topics was generated. Topics were selected that could generate potential recommendations for inclusion within the guidelines. Proposed topics were emailed to the international panel. Panel members were also invited to provide other topics that could be included. An environmental scan of the evidence surrounding each topic was provided to all participants to supplement discussion about the necessity of each topic. Each panellist discussed their perspective on the relevance of the topic for inclusion, and the list of topics were once again sent to panellists for review to achieve consensus. Each rater provided a rating of necessity for inclusion for each topic on a nine-point scale.

The final topics identified for recommendation development were: parental involvement (especially discharge planning), antimicrobial prophylaxis and skin preparation, perioperative communication and team structure, standard anaesthetic protocol and perioperative fluid management, postoperative vomiting/nasogastric intubation, preventing intraoperative hypothermia/temperature control, urinary drainage, postoperative nutritional care, the role of physiotherapy/occupational therapy, surgical practices, optimal haemoglobin levels, postoperative analgesia, management of transitional circulation and postoperative skin care/stoma care. The topics that were eliminated were those of antenatal management and location of surgery. Overall, inter-rater reliability across topics was excellent for absolute agreement with an interclass correlation of 0.95 (95% CI 0.91 to 0.98)

Literature search

Evidence searching within each topic area was performed using a modification of the systematic review process described within Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols checklist showing modifications to the process included in online supplementary material). Depending on expertise and preference, each topic was assigned to one or two members to perform a literature search. Within each topic, potential ERAS elements or target questions were selected following a predetermined (deductive) consensus, as well as a literature screen (inductive) to identify unanticipated areas of inquiry. A targeted search strategy for each topic was developed in collaboration with a research librarian. Target databases included MEDLINE and CINAHL for select topics. The structured search was supplemented by the members pursuing each topic with further focused literature searches, citation searching, a review of personal archives, as well through contact with experts to obtain important published and unpublished information. Each topic produced between 200 and 500 abstracts. Titles were catalogued using EndNote software. The search strategies aimed to obtain the most relevant and important studies but not necessarily generate a completely comprehensive review of the literature. Table 1 provides a sample of the root terms and topics used to create a specific search for nutritional care.

Table 1.

Planned search strategy for postoperative nutritional care topic

| Population | Procedure | Topic |

| Neonatal | Intestinal resection surgery | Reinitiating feeds |

| Neonate | Intestinal resections | Introduction of feeds |

| Neonates | Colon resection | Advancing feeds |

| Neonatology | Bowel resection | Feed progression |

| Infant | Laparoscopic resection | Feeding methods |

| Infants | Small bowel resection | Enteral nutrition |

| Newborn | Colectomy | Enteral feeding |

| Newborns | Partial colectomy | Oral feeding versus tube feeding |

| Infant and newborn | Anastomoses and surgical | Elemental formula versus semielemental |

| 37 weeks | Intestinal repair | Continuous feeds |

| Term birth | Digestive system surgical procedures | Bolus feeds |

| Gestational age | Ileostomy | Nutrition assessment |

| Bowel surgery | Optimal growth | |

| Surgical stoma | Optimal nutrition | |

| Stoma | Adequate nutrition | |

| Ostomy | Nutritional intake |

bmjopen-2018-023651supp001.pdf (167.2KB, pdf)

Study selection

The library of titles and abstracts for each topic were screened using Rayyan QCRI, a web-based systematic review application,16 by international guideline committee members and their respective teams to identify potentially relevant articles. Discrepancies in judgement were resolved by a third reviewer. Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomised controlled studies, non-randomised controlled studies, reviews and case series were all considered for each individual topic (eligibility criteria outlined in table 2). Studies were primarily restricted to those in the English language; however, important papers written in a language understood by other members of the team were also considered.

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Study design | Meta-analyses, OR systematic reviews, OR published guidelines or protocols, OR randomised control studies, OR non-randomised control studies OR reviews, OR case series. |

| Population | Term neonate patients, gestational age (≥37 weeks). Population without any major multicomorbidities. Excluded are: population with abdominal wall defects (gastroschisis and omphalocele); population with necrotising enterocolitis. |

| Type of surgery | Surgery performed in the first 4 weeks of life. For appropriate subtopics (eg, nutrition), studies will be restricted to intestinal resection procedures (intestinal repair, colon resection, bowel resection, laparoscopic resection, small bowel resection, colectomy and partial colectomy), OR stoma/ostomy, OR anastomoses. |

| Intervention (for ERAS Recommendation) |

Satisfies the following ERAS elements:

|

ERAS, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery.

Study quality assessment and data synthesis

Subtopics were identified deductively and inductively within each topic by each team and were catalogued along with a summary of the evidence supporting proposed ERAS recommendations. For example, within the topic area of prevention of intraoperative hypothermia, predetermined areas for inquiry included: target temperature range for neonates undergoing surgery, recommended environmental interventions to reduce hypothermia and recommended direct and indirect therapies to maintain normothermia.

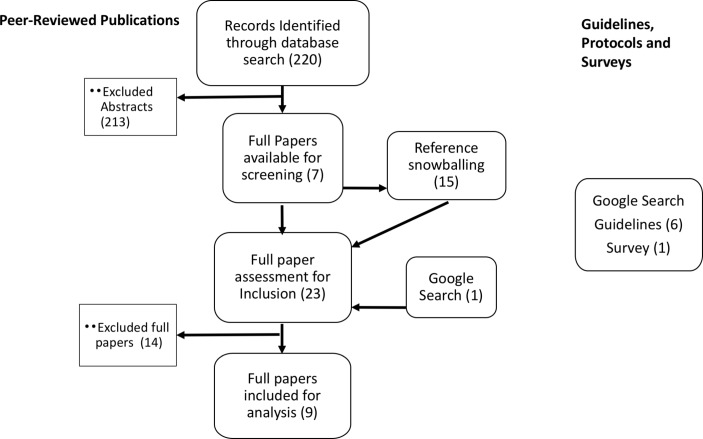

Initial systematic searches of MEDLINE and CINAHL were performed on 17 December 2017. Subsequent targeted searches of the peer-reviewed literature were performed within each topic based on the development of subtopics. Additional searches of the grey literature were also performed. The dates of these subsequent searches will accompany the search strategies for all recommendation when the ERAS guideline is published. Screening of titles and abstracts and full texts was performed by each group exploring each topic (paired screening was not required). An example of the screening flow diagram for the perioperative antibiotics topic is provided in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study screening (perioperative antibiotics).

Within each topic, one or more recommendation was developed meeting the criteria for intervention (table 2). For each recommendation, teams created tables summarising the supporting studies (online supplementary table S1) and the level of evidence for each study according to the Oxford Level of Evidence Guidelines.17

Consensus of evidence

The study will be performed according to the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method by conducting a two-round consensus process.18 Round one was completed through electronic surveys. In this round, panel members were asked to consider each recommendation on its own merits using the corresponding summarised evidence tables as well as their own experience and knowledge. Our panel included an expanded working group of 17 members including additional experts across specialties (surgery, neonatology and anaesthesiology).

We asked panellists to rate the clarity or lack of ambiguity of each recommendation statement, as well as the necessity of including it in the ERAS guideline. These ratings were performed on a nine-point rating scale. In addition, panellists were asked to provide comments or suggestions regarding the wording, the necessity of the recommendation or general comments.

Round two consisted of a full-day workshop in August 2018, moderated by the senior investigator. Attendees were, once again, provided with a summary of the peer-reviewed evidence including the level of evidence for each study as well as relevant guidelines. Each working group presented their recommendations to the panel and reviewed the screening flow chart, a table of the evidence and the results of the ratings including distribution and median, and comments from round one. Each recommendation was discussed in terms of potential measurable outcomes resulting from implementation of the recommendation. Recommendations were revised through group discussion or identified for further development. Recommendations were voted on for necessity for inclusion using the nine-point scale. Those recommendations with consensus for inclusion (a median panel score greater or equal to 7) were assessed for aggregate data quality and strength of recommendation (see below). Those recommendations that required further development will be reviewed after revision for consensus on necessity for inclusion, group assessment of aggregate quality and strength of recommendation.

The ratings for the recommendations at each stage will be reported including an interclass correlation to provide a measure of rater agreement.

Assessment of aggregate data quality and strength of recommendations

The aggregate quality of evidence for each topic will be rated by the respective guideline committee member and their team and discussed and voted on by the ERAS team. The GRADE system will be used, and evidence will be rated as either ‘high’, ‘moderate’, ‘low’, or ‘very low’ (table 3A).19 The ERAS team will decide on the strength of the recommendations based on the quality of data and the balance of potential desirable/undesirable effects through discussion and consensus. Any accompanying recommendations will be given a value of ‘strong’ or ‘weak’ (table 3B).20

Table 3A.

GRADE system for rating quality of evidence

| Quality | Definition |

| High | We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. |

| Moderate | We are moderately confident in the effect of the estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. |

| Low | Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. |

| Very low | We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. |

Table 3B.

GRADE system for rating strength of recommendations

| Strength | Definition |

| Strong | When desirable effects of intervention clearly outweigh the undesirable effects or clearly do not. |

| Weak | When the trade-offs are less certain—either because of low quality evidence or because evidence suggests desirable and undesirable effects are closely balanced. |

The creation of the finalised guideline will occur in October 2018 in partnership with the ERAS Society, with publication sought.

Patient and public involvement

Parents’ expectation of engagement in paediatric surgical and neonatal care pathways is demonstrated in systematic reviews of the literature and qualitative studies of parents’ attitudes in the neonatal intensive care unit.21–24 Our approach has been informed by this published data.

We engaged parent stakeholders in identifying neonatal surgical care as a key priority for an ERAS guideline. Once topics were selected for development by our ERAS guideline committee, we formally reviewed each of these topics with our ERAS parent advisor to identify subtopics for exploration and key areas that required parental involvement. Discharge planning was identified as a major theme to address within many key ERAS topics. In addition, parental psychological support was identified as a priority within the topic of parental involvement.

The initial proposal was developed with feedback from parent advocates. Two additional parent focus groups are engaged in this project. The first focus group provided input to the stakeholder group at the time of the face-to-face workshop to review recommendations. This group will meet again before the final refinement of the ERAS tool to discuss proposed ERAS recommendations, highlighting areas where and how parental needs can be better addressed. The second group will engage with the ERAS committee to aid in the development of feasible and acceptable implementation strategies for the completed guideline.

Future work: guideline implementation

Guidelines are to be implemented in a multistep process and evaluated within two separate studies. Stakeholder involvement in developing an implementation strategy will ensure appropriate engagement and context-sensitive adaption. The ERAS guideline will be integrated with existing surgical safety tools such as the Surgical Safety Checklist, a tool that performs optimally within larger quality and safety initiatives.25 Integration will occur in a manner that will avoid duplication, assist in appropriate tailoring and strengthen the implementation around both the surgical safety tool (ie, the checklist) and the ERAS guideline through a common protocol.

Implementation fidelity and impact on outcomes will both be assessed in this multimodal approach. Implementation fidelity will be determined through measures of compliance with ERAS elements and with other integrated surgical safety tools. Guidelines will be piloted in a large tertiary paediatric centre in Canada for 3 months. A focused assessment of acceptability and compliance will be performed through audits as well as surveys and targeted interviews. The content of these surveys and interviews will depend on the final elements included within the guideline but will be developed using survey creation methods including team item generation, question development, piloting and revision. We will use previously published surveys reviewing acceptability of clinical guidelines as a starting point. Based on this feedback, further revisions of the guideline will be performed.

The results of the initial implementation pilot will be reviewed by the international panel as well as the ERAS Society, and an international multicentre implementation study for clinical effectiveness will be designed. Clinical and process measure outcomes will be measured before and during implementation. Outcomes of interest will be determined by the eventual ERAS recommendations and may include: length of stay, SSI incidence, mortality, sepsis, postoperative vomiting, weight gain and parent and staff satisfaction. As per ERAS Society regulations, the guideline is to be considered for revision by the Scientific and Executive ERAS committee every 3 years or earlier if deemed appropriate.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been registered with the ERAS Society. Human ethics approval (REB 18–0579) is in place to engage patient families for guideline implementation development. This research will contribute to a consistent standard of care for neonatal abdominal surgery. This ERAS guideline development represents the first phase of a larger quality improvement project aimed at improving neonatal abdominal surgery.

bmjopen-2018-023651supp002.pdf (225.2KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ACNG: created tools, performed surveys, developed initial searches, analysed data and completed the first draft of the paper as well as critically revising the paper. MAC: performed surveys, aided in searches, aided in analysis, as well as critically revising the paper. CM: created tools, performed additional searches and surveys, aided in screening, consolidated and analysed data, developed summary tables as well as critically revising the paper. DU: aided in creating timeline and tools performed searches and screening, as well as critically revising the paper. JYKL, PWW, MB, MR, MO, EDS, TW, KW and DdB: helped determine initial scope and population as well as topics, performed screening, developed evidence tables, provided feedback on approach as well as critically revising the paper. GN: aided in concept development with ERAS, provided feedback on approach as well as critically revising the paper. MEB: developed the initial concept and approach, led the development of research methods, organized consensus development, provided final review of data and performed and reviewed analyses and provided first critical revision of draft and subsequent revision. All authors approve the final version.

Funding: The work in this study is supported by the Brian and Brenda MacNeill Chair in Pediatric Surgery.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002;183:630–41. 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)00866-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Le Compte AJ, Chase JG, Lynn A, et al. Development of blood glucose control for extremely premature infants. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2011;102:181–91. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Dejong CH, et al. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing major elective open colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr 2010;29:434–40. 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cerantola Y, Valerio M, Persson B, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(®)) society recommendations. Clin Nutr 2013;32:879–87. 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coyle MJ, Main B, Hughes C, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) for head and neck oncology patients. Clin Otolaryngol 2016;41:118–26. 10.1111/coa.12482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tracy ET, Mears SE, Smith PB, et al. Protocolized approach to the management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: benefits of reducing variability in care. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:1343–8. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery. JAMA Surg 2017;152:292–8. 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ljungqvist O, Thanh NX, Nelson G. ERAS-Value based surgery. J Surg Oncol 2017;116:608–12. 10.1002/jso.24820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leeds IL, Boss EF, George JA, et al. Preparing enhanced recovery after surgery for implementation in pediatric populations. J Pediatr Surg 2016;51:2126–9. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Short HL, Heiss KF, Burch K, et al. Implementation of an enhanced recovery protocol in pediatric colorectal surgery. J Pediatr Surg 2018;53 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. ERAS Compliance Group. The impact of enhanced recovery protocol compliance on elective colorectal cancer resection: results from an international registry. Ann Surg 2015;261:1153–9. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Segal I, Kang C, Albersheim SG, et al. Surgical site infections in infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr Surg 2014;49:381–4. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, et al. Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA 2004;292:2357–65. 10.1001/jama.292.19.2357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Young JY, Kim DS, Muratore CS, et al. High incidence of postoperative bowel obstruction in newborns and infants. J Pediatr Surg 2007;42:962–5. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matlow AG, Baker GR, Flintoft V, et al. Adverse events among children in Canadian hospitals: the Canadian Paediatric Adverse Events Study. CMAJ 2012;184:E709–18. 10.1503/cmaj.112153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Olofsson H, Brolund A, Hellberg C, et al. Can abstract screening workload be reduced using text mining? User experiences of the tool Rayyan. Res Synth Methods 2017;8:275–80. 10.1002/jrsm.1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. OCEBM Table of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence. 2011. http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653

- 18. Fitch K. European Commission. Directorate-General XII Science Research and Development., Rand Corporation. The Rand/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Santa Monica: Rand, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:401–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Obeidat HM, Bond EA, Callister LC. The parental experience of having an infant in the newborn intensive care unit. J Perinat Educ 2009;18:23–9. 10.1624/105812409X461199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reis MD, Rempel GR, Scott SD, et al. Developing nurse/parent relationships in the NICU through negotiated partnership. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2010;39:675–83. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ward K. Perceived needs of parents of critically ill infants in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Pediatr Nurs 2001;27:281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lagoo J, Lopushinsky SR, Haynes AB, et al. Effectiveness and meaningful use of paediatric surgical safety checklists and their implementation strategies: a systematic review with narrative synthesis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016298 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brindle ME, Henrich N, Foster A, et al. Implementation of surgical debriefing programs in large health systems: an exploratory qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:210 10.1186/s12913-018-3003-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023651supp001.pdf (167.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023651supp002.pdf (225.2KB, pdf)