Abstract

Human lysyl oxidase (LOX) is a hypoxia-responsive gene whose product catalyzes collagen crosslinking and is thought to be important in cancer metastasis and osteoarthritis. We previously demonstrated that LOX was upregulated by hypoxia inducible factor 2 (HIF-2) more strongly than hypoxia inducible 1 (HIF-1). We further investigated the response of the LOX gene and LOX promoter to HIFs. LOX mRNA, measured by real time reverse transcriptase-PCR, was strongly up-regulated (almost 40-fold), by transfection of HEK-293T cells with a plasmid encoding the HIF-2α subunit of HIF-2, but only three-fold by a plasmid encoding HIF-1α. LOX protein was detectable by Western blot of cells transfected with HIF-2α, but not HIF-1α. Analysis of a 1487 bp promoter sequence upstream of the human LOX gene revealed 9 potential hypoxia response elements (HREs). Promoter truncation allowed the mapping of two previously unidentified functional HREs, called here HRE8 and HRE7; −455 to −451 and −382 to −386 bp, respectively upstream of the start codon for LOX. Removal or mutation of these HRE’s led to a substantial reduction in both HIF-1α and HIF-2α responsiveness. Also, expression of LOX was significantly inhibited by a small molecule specific HIF-2 inhibitor. In conclusion, LOX is highly responsive to HIF-2α and this is largely mediated by two previously unidentified HREs. These observations enhance our understanding of the regulation of this important gene involved in cancer and osteoarthritis, and suggest that these conditions may be targeted by HIF-2 inhibitors.

Keywords: Lysyl oxidase, hypoxia, hypoxia inducible factor 2 alpha, HIF, promoter, hypoxia response element

Introduction

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) is one of a family of copper-dependent amine oxidases important in the intermolecular crosslinking of collagen and elastin in the extracellular matrix. LOX, encoded by the LOX gene, is synthesized in fibrogenic cells as a pre-pro-enzyme that is cleaved and glycosylated before secretion. Once secreted, the proenzyme is proteolytically processed by procollagen C-proteinase, releasing a 32-kDa active mature form (for review see [1]). More recently, it was shown that LOX is essential for endothelial cell stimulation and important in angiogenesis [2].

There is an emerging appreciation that LOX also plays a role in diseases including cancer and osteoarthritis [3–8]. LOX is associated with tumor metastases [4] and has recently drawn interest as a potential target for cancer therapy when it was demonstrated it was responsive to hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) [5, 6]. LOX expression is increased in tumor cells exposed to hypoxia and is associated with metastasis and poor survival in patients with breast, head and neck cancer [6]. Studies suggests LOX may provide a useful target for treatment of certain cancers (for review see [9]). LOX is implicated in SRC-dependent proliferation in colorectal cancer [10] and its enzymatic activity is required for effects on cellular proliferation and invasion in colorectal cancer models [11]. Finally, there is evidence that LOX plays an important role in collagen crosslinking involved in development of osteoarthritis [8] and therefore it could be an important target for prevention and therapy of osteoarthritis.

Cells mediate much of their adaption to hypoxia through upregulation of hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) [12–14]. HIF-1, the principle HIF, is a heterodimer of HIF-1α and HIF-1β. HIF-1β is constitutively produced but destroyed under normoxic conditions; however, this process is inhibited under hypoxia. The other major HIF, HIF-2, is comprised of HIF-2α plus HIF-1β. HIF-2 is only present in certain cell types, such as endothelial cells [14, 15]. Also, while most hypoxia sensitive genes are upregulated by HIF-1 and HIF-2, some genes are preferentially upregulated by HIF-1, while others (such as PTPRZ1) are preferentially upregulated by HIF-2 [15–18].

We showed LOX was upregulated in response to hypoxia and was preferentially responsive to HIF-2α; it was upregulated 6.5 fold by hypoxia, 4 fold by HIF-1α transfection, and almost 22 fold by HIF-2α [16]. LOX mRNA expression in Hep3B cells induced by hypoxia mimetics is reduced by knockdown of HIF-1 or HIF-2, and a weak HRE responsive to hypoxia and HIF-1α is present in the first 200 bp upstream of LOX [6, 19]. A subsequent study confirmed the HIF-1-responsive HRE in the first 200 bp of the LOX promoter but demonstrated that this HRE was only partially responsible for the hypoxia-responsiveness of LOX expression [20]. Deletion experiments revealed that a region from −821 to −405 also contributed to HIF-1-responsiveness of LOX, but was not characterized further [20]. We examined an approximately 1500 nucleotide LOX promoter to investigate its upregulation by HIFs, particularly HIF-2. Using truncation and mutational analysis, we identified two hypoxia response elements in the LOX promoter between −473 and −381 that mediate much of the responsiveness to HIF-2. This data reveals a previously unrecognized role for HIF-2 in upregulation of human LOX, thus furthering our understanding of this important gene involved in cancer and metastasis.

Material and Methods

Cell culture and Reagents

The HEK293T cell line was obtained from ATCC. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, Utah) and penstrep/glutamine (Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were incubated in 95% air and 5% CO2 (normoxia) at 37°C. HIF-2 antagonist-2 ((N-(3-chloro-5-fluorophenyl)-4 nitrobenzo [c] (1,2,5) oxadiazol-5-amine, henceforth called CFNOA) Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Cells (5×105) were plated in 6-well plates Corning (Kennebunk, ME) and 24 hrs later the cells were either treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or the inhibitor at 1, 10, 30, and 50 µM. Following incubation with inhibitor for 2 hours, cells were placed in normoxia or hypoxia (1%O2) extracted for mRNA after 16 hours.

Plasmid DNA construction, site-directed mutagenesis, and sequence analysis

An expression plasmid encoding degradation-resistant HIF-1α (drHIF-1α) was from Dr. Eric Huang (NCI, NIH) [21]. A plasmid encoding degradation-resistant HIF-2α (drHIF-2α) was created by mutating prolines 405 and 531 of HIF-2α, as reported [18]. Plasmids were purified with a Qiagen Maxiprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and inserts verified. LOX gene promoter luciferase reporter constructs were created containing regions spanning nucleotides −1487bp, −1079bp, −630bp, −473bp, −403bp, −381bp, and −333bp upstream of the start codon (ATG) (see Fig. 2). DNA fragments were amplified from human genomic DNA (Cat#G304A Promega Madison WI) by PCR with 5’primers LOXF6, LOXF7, LOXF8, LOXF11, LOXF12, LOXF13 and LOXF14 5’-AGTCATGCTAGCGTCTGGACAATAGCCCA -3’, 5’-AGTCATGCTAGCGCATATGTGAAGATGCC-3’, 5’-AGTCATGCTAGCGGCTGGTGACCTAATAGC-3’, 5’-AGTCATGCTAGCCTTAACGCTCCCTGTGCA-3’, 5’-AGTCATGCTAGCAGGAGCTGTCCGCCTT-3’, 5’-AGTCATGCTAGCCGGCTTGTGTAACTTTGC-3’, 5’-AGTCATGCTAGCTTCCAATCGCATTACGTG-3’ and 3’primer LOXR1(5’-AGCTGCAAGCTTCACTCCTTTTGCCAG -3’) which contain NheI/HindIII sites. PCR fragments were cloned into corresponding sites of the luciferase reporter vector pGL3basic (Promega).

Fig 2. LOX luciferase promoter and truncated promoter constructs and location of potential hypoxia response elements (HRE) in the LOX promoter, and HIF-2α and HIF-1α activation of the full length (1487) and truncated LOX promoter constructs.

(A) The full length (1487bp) and truncated promoter constructs (1079bp, 630bp, 473bp, 403bp, and 381bp) are indicated. Each potential HRE is denoted as a square, HRE9 in grey contains only the core sequence. The arrow above each HRE indicates direction (5’ or 3’) of the HRE. The ATG start site is indicated in the promoter as a down arrow sign and the CAAT box is denoted as a star.

(B) Cells were transfected with drHIF-2α or drHIF-1α (250 ng), 300ng each of full-length or truncated LOX promoters, and 50ng of an internal β-gal control plasmid. Results presented (luciferase activity fold induction) are the average +/− standard deviation of 3 separate experiments in triplicate (except for pLOX1487 and pLOX381, two experiments in triplicate, the range is shown).

In silico analysis of potential HREs was undertaken using MacVector software. The promoter region was searched for core HRE sequence CGTG and potential HREs were identified: HRE9; −603–599, HRE8; −455–451, HRE7; −382–386, HRE6; −368–364, HRE5; −313–309, HRE4; 191–195, HRE3; −111–115, HRE2; −73–69, and HRE1; −33–37. Plasmid DNAs LOX-473 and LOX-403 expressing two different mutant forms of HRE7 were prepared using PCR-based QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Primers containing the mutated HRE7 sequences for Mut1 5’ primer: (5’-AGGAGCTGTCCGCCTTGCATA TTTCCAATCGCATTA-3’) and Mut2 primer: (5’-AGGAGCTGTCCGCCTTGCGCATTCCAATCGCATTA -3’). The mutant plasmids contained a 2 nucleotide substitution in HRE7, (HRE7 from CACGT to CATAT for Mut1 and CGCAT for Mut2, underlined). Reactions were performed for 16 cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 1 min and 68°C for 7min. PCR products were incubated with DpnI enzyme at 37°C for 2 hours. DNA was used to transform XL1-Blue competent cells. Constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Transfection and luciferase reporter assays

Cells were transfected as described [16] using Fugene6 transfection reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). For luciferase reporter experiments, 1.5×105 of cells/well were plated in a 12-well plate and the following day were co-transfected with 300 ng/well of reporter plasmid DNA and 250 ng/well of drHIF or control (pcDNA3.1) plasmid with 50 ng of internal control plasmid DNA, pSV-b-gal (Promega). Cells were incubated in normoxia for 48 hours, washed with PBS, lysed with 250 µ L per well of 1× reporter lysis buffer (Promega), and freeze-thawed. After samples were centrifuged at 13,000g for 8 min, 20 µL and 50 µL of lysate was used to determine luciferase and β-gal activity. The expression vector pcDNA3.1 was set at unity and values for different promoters plotted as fold induction over the control.

Immunoblotting

Lysates prepared from untransfected cells and cells transfected with plasmids (48 h) encoding drHIF-1α or drHIF-2α were electrophoresed (40 µg) on precast 4% to 12% Tris-Bis NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen), transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, blocked overnight at 4°C with 5% w/v nonfat dry milk in 1× TBST [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20. Blots were incubated with antibodies to LOX Abcam (Cambridge, MA), HIF-1α BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) HIF-2α (Novus Biological, Inc., Littleton, CO) or β-actin (Sigma) and a secondary antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase. Bands were visualized with stabilized Western Blue substrate (Promega).

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was extracted from cells 48 hours post transfection with RNAeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and RNA (5µg) was treated with RNase-free DNaseI (Ambion). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 820 ng of RNA using Roche First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche Applied Science). For real-time PCR experiments, 41 ng of RNA (start) was amplified in 2×SYBR PCR master mix using TF-Stepone RT PCR System (PE applied Biosystems, Branchburg, NJ) with the following primers (shown in 5’ to 3’ direction): for Actin, CCTTCCTGGGCATGGAGT and CAGGGCAGTGATCTCCTTCT; for LOX, TCAGATTTCTTACCCAGCCGA and GGCAGTCTATGTCTGCACCA; for MAP2K5, TACTCTTCAGGGATGTGCTG and CTTCAGGCCATGTATGTTCC; for VEGF, CCTTGCTGCTCTACCTCCAC and AGCTGCGCTGATAGACATCC; for PGK1, TTAAAGGGAAGCGGGTCGTTA and TCCATTGTCCAAGCAGAATTTGA. Samples were incubated at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles, each consisting of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. Melting curves were generated after each run to confirm amplification of specific transcripts. All quantifications were normalized to human β-actin. Real time PCR reactions were performed in triplicate.

Results

Induction of LOX mRNA and protein expression in HEK-293T cells transfected with drHIF-1α or drHIF-2α

We previously investigated the upregulation of cellular genes in HEK-293T cells transfected with HIF-1α, HIF-2α, or cells exposed to hypoxia by microarray. LOX was upregulated by hypoxia and HIFs, and was noteworthy for being most selectively and substantially upregulated by HIF-2 [16]. To investigate the activation of LOX by HIFs, we verified upregulation of LOX mRNA expression by real time PCR following transfection of HEK-293T cells with drHIF-1α or drHIF-2α. Since HIF’s are readily degraded in normoxia, we used degradation-resistant forms of HIF-1α and HIF-2α to maintain HIF expression in cells transfected in normoxia. Transfection of cells with drHIF-1α caused a 3-fold upregulation of LOX mRNA, while transfection of cells with drHIF-2α caused a >35 fold upregulation of LOX mRNA (Fig. 1A). By contrast, expression of MAP2K5, a gene with increased expression in rats exposed to hypoxia [22], was upregulated almost 8-fold by HIF-1α yet only 3-fold by drHIF-2α (Fig. 1B). Western blot confirmed expression of drHIF-1α and drHIF-2α in transfected cells (Fig. 1C). However, while unprocessed LOX protein (PreProLOX) was not detected in control or HIF-1α transfected cells, it was clearly detected in cells transfected with HIF-2α (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that HIF-2α plays a major role in regulating LOX expression in cells able to express HIF-2α.

Fig 1. LOX and MAP2K5 mRNA and protein expression in HEK293T cells transfected with HIF-1α or HIF-2α.

A and B) Fold increase in LOX and MAP2K5 mRNA expression following transfection with drHIF-1α or drHIF-2α. Cells were transfected for 48 hrs with drHIF-1α or drHIF-2α (1 µg each, 6 well plate). Total RNA was analyzed for LOX, MAP2K5 and β-actin expression. Values are normalized to β-actin expression and represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate determinations. C) Western blot for HIF-1α, HIF-2α, LOX, and β-actin (40 µg) from cells transfected with control plasmid in 10 cm dishes with drHIF-1α or drHIF-2α (5 µg each, 48 hrs). β-actin as a loading control. Data represents at least three independent experiments.

Identification of the functional HREs in the LOX promoter responsive to HIF-2α

LOX contains an HRE within the first 200 base pairs upstream of the LOX start codon [6]. However, this promoter was only induced 2-fold by a degradation-resistant form of HIF-1α [6]. Since hypoxia-responsive promoters can have multiple HRE and require more than one for full activation [23], we analyzed the LOX promoter region in more detail by examining the sequence further upstream of the LOX start site. Sequence analysis of a 1487 bp promoter sequence for the HRE core sequence [24] identified nine potential HREs (Fig 2A). HRE 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 and 9 are encoded in 5’>3’ direction on the sense strand while the other three, HRE 1, 4, and 7, are encoded in the 5’>3’ direction on the antisense strand. HREs 1–8 all contain an HRE consensus sequence A/GCGTG while HRE 9 contains only the core CGTG.

In addition to the 1487 bp promoter, truncated forms were prepared (−1079bp, −630bp, −473bp, −403bp, −381bp, and −333bp) (Fig. 2A). LOX promoters were transiently transfected into cells along with a plasmid encoding drHIF-2α or drHIF-1α. Co-transfection with drHIF-2α increased the 1487 bp LOX activity by an average of 46 fold in cells. Strong activation by drHIF-2α was observed for the 3 longer truncated promoters (−1079p, 56 fold; −603p, 60 fold; −473p, 48 fold) (Fig. 2B). However, there was a significant loss of HIF-2α activation following truncation of the −473 promoter to generate the −403 promoter (48 fold to 13 fold). The −403 promoter no longer contains HRE8 suggesting HRE8 may be a HIF-2α functional HRE in the LOX promoter. Further truncation to generate the −381 promoter led to substantial loss in activity to HIF-2α (from 13 fold to only 3 fold) also suggesting a potential role for HRE7 in HIF-2α inducing activity (Fig. 2B). Response of the different LOX promoters toward HIF-1α paralleled that for HIF-2α, however the response was generally 60–70% less than for HIF-2α. The data from the experiments on the truncated promoters suggest both HRE8 and HRE7 of the human LOX promoter are particularly important and work together to provide strong HIF-2α and less HIF-1α responsiveness. The remaining low HIF-induced activity of the shorter promoters (−381 and −333) is consistent with a previous report identifying a weak functional HRE within the first 200 base pairs upstream of the LOX start site and this HRE is consistent with HRE2 in our human LOX promoter [6].

Mutational Analysis of HRE7 of the LOX-473 and LOX-403 promoter

We wanted to explore HRE7 further, as deletion of this HRE (to produce the −381 promoter) abrogated almost all the responsiveness to HIF-1α and HIF2α. To confirm HRE7 in the −473 and −403 promoter was acting as a functional HRE, we performed site-directed mutational analysis. Two different two-base substitutions were made in HRE7 of the −473 and −403 promoters to generate LOX-473Mut1, LOX-473Mut2, LOX-403Mut1 and LOX-403Mut2 (Fig. 3A). Mutation Mut1 and Mut2 of HRE7 decreased drHIF-2α-induced up-regulation of LOX-473 promoter by about 50% (Fig. 3B) consistent with loss of activity from HRE7 but activity still being provided through HRE8 present in LOX-473 but not in LOX-403. Also, the Mut1 or Mut2 mutation of HRE7 decreased HIF-2α induced up-regulation of LOX-403 promoter by more than 80% (Fig. 3B) suggesting a substantial portion of the HIF-responsive activity in LOX-403 resides in HRE7. These results indicate HRE7 is a functional HRE to HIF-2α in the LOX promoter and strongly suggests HRE8 also plays a major role in HIF responsiveness.

Fig 3. Mutational analysis of HRE7 of pLOX-473 and pLOX-403 promoter and the response to HIF-2α.

(A) DNA sequences for WT and mutant constructs of HRE7 and surrounding promoter region of LOX. The underlined region indicates the location of the putative HRE7, and bold letters indicate the mutations from WT for each mutation construct. (B) Cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding drHIF-2α (250 ng) and either the WT −473 promoter (WT), the HRE7Mut1 −473 promoter (M1), or the HRE7Mut2 −473 promoter (M2) (300 ng each). (C) Cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding drHIF-2α (250 ng) and either the WT −403 promoter (WT), the HRE7Mut1 −403 promoter (M1), or the HRE7Mut2 −403 promoter (M2) (300 ng each). The data plotted is the average +/− standard deviation from 3 separate experiments.

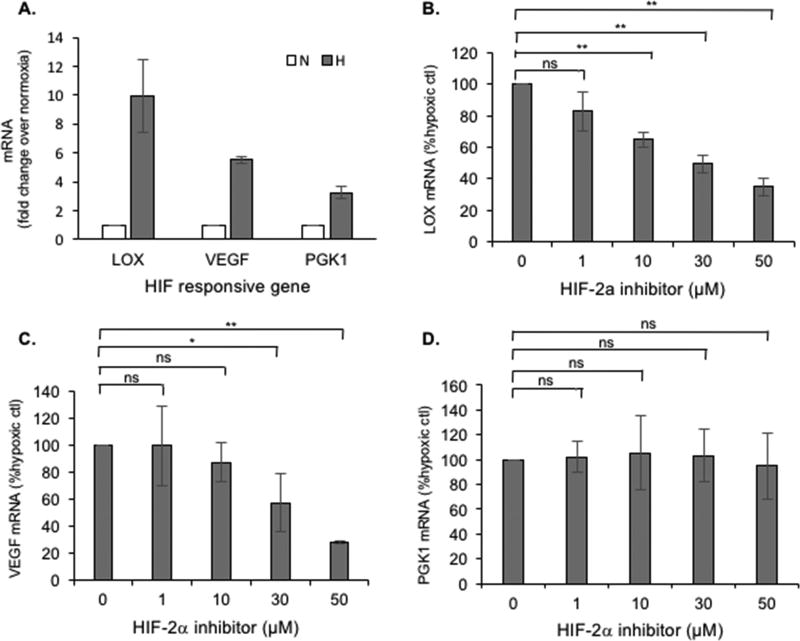

Inhibition of LOX mRNA expression using a HIF-2α specific inhibitor CFNOA

We next explored if upregulation of LOX mRNA production in hypoxia could be blocked using a specific allosteric inhibitor of HIF-2, CFNOA, that does not affect HIF-1 function [25]. Cells were incubated in normoxia or hypoxia with different concentrations of CFNOA. The expression of three hypoxia-responsive genes were analyzed including LOX, VEGF, and PGK1. VEGF is activated by HIF2 and to lesser extent by HIF-1 and inhibited by CFNOA, while PGK1 is almost exclusively a HIF-1 responsive gene and is not responsive to CFNOA [25]. Hypoxia upregulated the LOX, VEGF and PGK1 mRNA expression by approximately 10, 6, and 4-fold, respectively (Fig. 4A). Treatment with CFNOA led to a dose dependent decrease in LOX mRNA (Fig. 4B) and VEGF mRNA (Fig. 4C) upregulation in hypoxia but had no appreciable effect on PGK1 mRNA (Fig. 4D). At 50 µM CFNOA, LOX mRNA and VEGF mRNA expression was reduced by 65% and 72%, respectively. These studies suggest HIF-2α plays a significant role upregulation of LOX mRNA and protein expression in cells exposed to hypoxia.

Fig. 4. Inhibition of LOX mRNA upregultion by hypoxia with a HIF-2 specific inhibitor.

(A) Hypoxic upregulation of three hypoxia responsive genes, LOX, VEGF, and PGK1. Effect of the HIF-2 inhibitor CFNOA on (B) LOX, (C) VEGF and (D) PGK1 mRNA in hypoxia. In (A) data for each gene are the mean of 5 experiments and the error bars represent ± SD. In (B–D) data are the mean of three or more independent experiments (5 for LOX, 3 for VEGF, and 4 for PGK1). Differences between paired values with 3–5 experiments that are statistically significant as determined by t-test are denoted as follows: * = p < 0.01; ** = p < 0.001

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that LOX is a hypoxia-responsive gene important in collagen crosslinking, in cancer biology, and in other diseases such as osteoarthritis [7, 8, 26–30]. Previous analysis of the first 200 bp of the upstream promoter identified a weak HIF-1α-responsive HRE (2-fold response) [6]. Further studies by Guadall et al. verified the HIF responsiveness of the HRE within the first 200 bp and described a region upstream (−821 to −405) that was responsive to hypoxia. However, they did not identify any HRE’s in this region and suggested it might be independent of HIF-1α [20]. We previously showed LOX is preferentially responsive to HIF-2 [16], and further investigated the responsiveness of the LOX promoter to HIF-1 and HIF-2. We identified two novel HREs in the 1487 promoter (HRE7 and HRE8) that mediate much of the response to HIF-2 and HIF-1. One of these, HRE7, was shown by mutational analysis to play a major role in HIF responsiveness. Interestingly, the other HRE (HRE8, 455-451) is located in the previously identified hypoxia responsive region identified by Guadall et al. [20].

Some hypoxia-responsive genes respond relatively equally to both HIF-1α and HIF-2α while other genes are preferentially up-regulated by only one factor or the other [15, 16]. No matter what the HIF preference, the promoter regions analyzed require a consensus HRE, and the preferential responsiveness to HIF-1 or HIF-2 has not been linked to sequence variation within the HRE. Instead, the specificity of activation appears to lie with other associated factors that participate in the hypoxia response such as ETS transcription factors [17, 18, 31]. Also, promoters for hypoxia responsive genes often contain more than one HRE and together they function to provide a strong hypoxic response (for review see [32]). Here, LOX also appears to be upregulated through multiple HREs within the upstream promoter region. We have identified additional HREs in the 1487 base pairs upstream of the LOX gene that contribute the majority of the strong HIF-responsiveness. Together our data suggest at least three HREs in the LOX promoter are involved in HIF up-regulation and include HRE8, HRE7, and HRE2 as diagrammed in Fig. 2.

While both HIF-1α and HIF-2α can mediate the cellular response to hypoxia, they differ in their responsiveness to other cellular signals and cell types in which they are expressed [7, 16]. HIF-2α expression and LOX are important in oncogenesis and especially the process of metastases [33]. Also, HIF-2α is induced in cells involved with collagen modeling, such as chondrocytes, and recent studies indicate HIF-2α and LOX play an important role in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis [7, 8]. Several specific small-molecule inhibitors of HIF-2α have been described [25], and it is possible that these may be useful in the prevention or treatment of cancer metastases, osteoarthritis, or other diseases in which upregulation of LOX is involved. A potential advantage of specific HIF-2 inhibitors is that they would not block the general response of cells to hypoxia mediated by HIF-1. We found that a HIF-2α specific allosteric inhibitor significantly inhibited LOX mRNA expression induced by hypoxia while having no significant effect on PGK1, a gene upregulated specifically by HIF-1α. Therefore, this will be a potentially exciting area of future research.

LOX, a hypoxia-responsive gene that encodes lysyl oxidase, is activated by HIF-2 more than HIF-1.

Two new hypoxia response elements identified in the LOX promoter mediate most HIF responsiveness.

The two hypoxia response elements of LOX are more responsive to HIF-2 than HIF-1.

Hypoxic upregulation of LOX mRNA is inhibited by a specific HIF-2 inhibitor.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Molnar J, Fong KS, He QP, et al. Structural and functional diversity of lysyl oxidase and the LOX-like proteins. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2003;1647:220–224. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(03)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker AM, Bird D, Welti JC, et al. Lysyl oxidase plays a critical role in endothelial cell stimulation to drive tumor angiogenesis. Cancer research. 2013;73:583–594. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payne SL, Hendrix MJ, Kirschmann DA. Paradoxical roles for lysyl oxidases in cancer--a prospect. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:1338–1354. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirschmann DA, Seftor EA, Nieva DR, et al. Differentially expressed genes associated with the metastatic phenotype in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;55:127–136. doi: 10.1023/a:1006188129423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erler JT, Giaccia AJ. Lysyl oxidase mediates hypoxic control of metastasis. Cancer research. 2006;66:10238–10241. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Nicolau M, et al. Lysyl oxidase is essential for hypoxia-induced metastasis. Nature. 2006;440:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/nature04695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husa M, Liu-Bryan R, Terkeltaub R. Shifting HIFs in osteoarthritis. Nature medicine. 2010;16:641–644. doi: 10.1038/nm0610-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JH, Lee G, Won Y, et al. Matrix cross-linking-mediated mechanotransduction promotes posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:9424–9429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505700112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox TR, Gartland A, Erler JT. Lysyl Oxidase, a Targetable Secreted Molecule Involved in Cancer Metastasis. Cancer research. 2016;76:188–192. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker AM, Cox TR, Bird D, et al. The role of lysyl oxidase in SRC-dependent proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:407–424. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker AM, Bird D, Lang G, et al. Lysyl oxidase enzymatic function increases stiffness to drive colorectal cancer progression through FAK. Oncogene. 2013;32:1863–1868. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang GL, Semenza GL. Characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and regulation of DNA binding activity by hypoxia. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1993;268:21513–21518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: master regulator of O2 homeostasis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:588–594. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian H, McKnight SL, Russell DW. Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes & development. 1997;11:72–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu CJ, Wang LY, Chodosh LA, et al. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9361–9374. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang V, Davis DA, Haque M, et al. Differential gene up-regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha in HEK293T cells. Cancer research. 2005;65:3299–3306. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aprelikova O, Wood M, Tackett S, et al. Role of ETS transcription factors in the hypoxia-inducible factor-2 target gene selection. Cancer research. 2006;66:5641–5647. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang V, Davis DA, Veeranna RP, et al. Characterization of the activation of protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor-type, Z polypeptide 1 (PTPRZ1) by hypoxia inducible factor-2 alpha. PloS one. 2010;5:e9641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schietke R, Warnecke C, Wacker I, et al. The lysyl oxidases LOX and LOXL2 are necessary and sufficient to repress E-cadherin in hypoxia: insights into cellular transformation processes mediated by HIF-1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:6658–6669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guadall A, Orriols M, Alcudia JF, et al. Hypoxia-induced ROS signaling is required for LOX up-regulation in endothelial cells. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2011;3:955–967. doi: 10.2741/e301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang LE, Gu J, Schau M, et al. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is mediated by an O2-dependent degradation domain via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:7987–7992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen LM, Kuo WW, Yang JJ, et al. Eccentric cardiac hypertrophy was induced by long-term intermittent hypoxia in rats. Exp Physiol. 2007;92:409–416. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.036590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kietzmann T, Samoylenko A, Roth U, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and hypoxia response elements mediate the induction of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene expression by insulin in primary rat hepatocytes. Blood. 2003;101:907–914. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wenger RH, Gassmann M. Oxygen(es) and the hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Biological chemistry. 1997;378:609–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheuermann TH, Li Q, Ma HW, et al. Allosteric inhibition of hypoxia inducible factor-2 with small molecules. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:271–276. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishioka T, Eustace A, West C. Lysyl oxidase: from basic science to future cancer treatment. Cell Struct Funct. 2012;37:75–80. doi: 10.1247/csf.11015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bar EE, Lin A, Mahairaki V, et al. Hypoxia increases the expression of stem-cell markers and promotes clonogenicity in glioblastoma neurospheres. The American journal of pathology. 2010;177:1491–1502. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart GD, Gray K, Pennington CJ, et al. Analysis of hypoxia-associated gene expression in prostate cancer: lysyl oxidase and glucose transporter-1 expression correlate with Gleason score. Oncol Rep. 2008;20:1561–1567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Postovit LM, Abbott DE, Payne SL, et al. Hypoxia/reoxygenation: a dynamic regulator of lysyl oxidase-facilitated breast cancer migration. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:1369–1378. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sorensen BS, Alsner J, Overgaard J, et al. Hypoxia induced expression of endogenous markers in vitro is highly influenced by pH. Radiother Oncol. 2007;83:362–366. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlot C, Dubois-Pot H, Serchov T, et al. A review of post-translational modifications and subcellular localization of Ets transcription factors: possible connection with cancer and involvement in the hypoxic response. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;647:3–30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-738-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marignol L, Lawler M, Coffey M, et al. Achieving hypoxia-inducible gene expression in tumors. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:359–364. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.4.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rankin EB, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxic control of metastasis. Science (New York, N.Y. 2016;352:175–180. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]