Abstract

Background

The ATLAS trial compared axitinib versus placebo in patients with locoregional renal cell carcinoma (RCC) at risk of recurrence after nephrectomy.

Patients and methods

In a phase III, randomized, double-blind trial, patients had >50% clear-cell RCC, had undergone nephrectomy, and had no evidence of macroscopic residual or metastatic disease [independent review committee (IRC) confirmed]. The intent-to-treat population included all randomized patients [≥pT2 and/or N+, any Fuhrman grade (FG), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status 0/1]. Patients (stratified by risk group/country) received (1 : 1) oral twice-daily axitinib 5 mg or placebo for ≤3 years, with a 1-year minimum unless recurrence, occurrence of second primary malignancy, significant toxicity, or consent withdrawal. The primary end point was disease-free survival (DFS) per IRC. A prespecified DFS analysis in the highest-risk subpopulation (pT3, FG ≥ 3 or pT4 and/or N+, any T, any FG) was conducted.

Results

A total of 724 patients (363 versus 361, axitinib versus placebo) were randomized from 8 May 2012, to 1 July 2016. The trial was stopped due to futility at a preplanned interim analysis at 203 DFS events. There was no significant difference in DFS per IRC [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.870; 95% confidence interval (CI) : 0.660–1.147; P = 0.3211). In the highest-risk subpopulation, a 36% and 27% reduction in risk of a DFS event (HR; 95% CI) was observed per investigator (0.641; 0.468–0.879; P = 0.0051), and by IRC (0.735; 0.525–1.028; P = 0.0704), respectively. Overall survival data were not mature. Similar adverse events (AEs; 99% versus 92%) and serious AEs (19% versus 14%), but more grade 3/4 AEs (61% versus 30%) were reported for axitinib versus placebo.

Conclusions

ATLAS did not meet its primary end point; however, improvement in DFS per investigator was seen in the highest-risk subpopulation. No new safety signals were reported.

Trial registration number

Keywords: adjuvant, axitinib, disease-free survival, overall survival, renal cell carcinoma, safety

Key Message

The ATLAS trial compared axitinib versus placebo in patients with locoregional renal cell carcinoma at risk of recurrence after nephrectomy. The trial was stopped due to futility at a preplanned interim analysis. There was no significant difference in disease-free survival (DFS) per independent review committee (IRC) assessment. Prespecified subgroup analysis showed that in patients at the highest risk of recurrence, a 36% and 27% reduction in risk of a DFS event was seen by both IRC and investigator assessments.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common form of kidney cancer; approximately 80% of RCCs are clear-cell tumors [1]. The 5-year survival rates by American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor, lymph nodes, and metastasis (TNM) staging system are 81%, 74%, 53%, and 8% for stages I, II, III, and IV, respectively [2]. Some patients with locoregional RCC have a relapse risk of up to 40%, increasing to up to 80% in patients considered to be at high risk for recurrence, and could therefore benefit from adjuvant treatment [3, 4]. The success of targeted therapies in the metastatic RCC setting led to increased interest in testing these agents in the adjuvant setting. Overall five additional trials assessed the utility of targeted therapy in the adjuvant RCC setting. Of the three completed trials (ASSURE, S-TRAC, and PROTECT) [5–7], only S-TRAC met its primary end point.

S-TRAC included patients with resected ≥T3 and/or N+ clear-cell RCC at high risk for tumor recurrence after nephrectomy. Results showed that disease-free survival (DFS) was significantly longer with sunitinib treatment versus placebo: hazard ratio (HR) = 0.76; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.59–0.98; P = 0.03; medians, 6.8 and 5.6 years, respectively [7]. Based on S-TRAC outcomes, the US Food and Drug Administration extended sunitinib’s indication to include the treatment of patients at high risk for recurrence after nephrectomy.

Axitinib is an oral, potent, and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1, 2, and 3. In the phase III AXIS trial in the second-line setting of metastatic RCC, significantly longer progression-free survival and higher objective response rate were reported for axitinib versus sorafenib; however, the safety profiles were similar and manageable [8]. Consequently, axitinib is approved for the treatment of advanced RCC after failure of one prior systemic therapy. Additionally, in various clinical trials, antitumor activity was observed with axitinib, both as a single agent and in combination with immunotherapy, in the first-line treatment of metastatic RCC [9–11]. Here, we report the efficacy and safety of adjuvant axitinib versus placebo in patients with ≥pT2 and/or N+ RCC from the Adjuvant Axitinib Therapy of Renal Cell Cancer in High Risk Patients (ATLAS) trial.

Methods

Study design

ATLAS was a phase III, randomized, double-blind trial (NCT01599754). Patients were enrolled at 137 centers in 8 countries [China (mainland and Hong Kong), France, India, Japan, Korea, Spain, Taiwan, USA] from 8 May 2012 to 1 July 2016.

A summary of the key amendments that had an impact on the conduct of the trial and planned analyses are described in the supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online. The trial was approved by local institutional review boards and conducted in accordance with the protocol, International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable local regulatory requirements and laws. All patients provided written informed consent. An independent data and safety monitoring committee regularly reviewed patient safety and efficacy data.

Patients

Patients aged ≥18 years (≥20 years in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan and ≥18 to ≤65 years in India) had newly diagnosed RCC [≥pT2 and/or N+, any Fuhrman grade (FG), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0/1] and prior nephrectomy (complete or partial; supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online). Previous antiangiogenic treatment or systemic treatment of RCC was not permitted. Patient eligibility was confirmed by independent review committee (IRC) assessment of imaging before randomization.

Patients were randomized (stratified by country and/or risk group) in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive twice-daily oral axitinib 5 mg or placebo tablets (supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online). At that time, the optimal duration for adjuvant treatment was unknown; based on research in other tumors it was estimated to be between 1 and 3 years [12]. Depending on the patient’s/investigator’s decision, patients were treated for up to 3 years and for a minimum of 1 year unless there was recurrence, occurrence of a second primary malignancy, significant toxicity, or withdrawal of consent. Details on dose modifications and tumor assessments are reported in the supplementary materials, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Outcomes

The primary end point was DFS according to IRC assessment. DFS was defined as the time from randomization to the first date of distant or local recurrence of RCC or occurrence of a second primary malignancy or death. Secondary end points were overall survival (OS) and safety. OS was defined as the time from randomization to death due to any cause. Safety was assessed throughout the trial and included the type, incidence, severity (graded by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, v4.0), timing, seriousness, and relatedness of adverse events (AEs); laboratory abnormalities; physical examination; vital signs; and ECOG PS.

Statistical analyses

Details on sample size determination are reported in the supplementary materials, available at Annals of Oncology online. Efficacy end points and patient characteristics were evaluated in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which included all randomized patients, regardless of whether they received study drug. Safety end points were evaluated in the ‘as-treated’ population, i.e. all patients who received at least one dose of study drug as reported in patient diaries. Additional prespecified efficacy analyses included subgroup analysis of DFS in the highest-risk subpopulation (pT3 with FG ≥3 or pT4 and/or N+, any T, any FG) and lower-risk subpopulation (pT2 or pT3 with FG ≤2), and sensitivity analysis of DFS as assessed by the investigator.

For the primary end point, median DFS and corresponding 95% CI were estimated for each arm using Kaplan–Meier methods. Treatment arms were compared using a two-sided log-rank test stratified by risk group. Country was not used as a stratification factor due to the limited number of patients enrolled in some countries. The HR and 95% CI were estimated by proportional hazard regression stratified by risk group. OS was analyzed in the same manner as the primary end point. Safety was summarized descriptively.

Statistical analysis was carried out using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The cutoff date for these analyses was 10 October 2017. The interim analysis was carried out at 203 events; futility stopping boundary: P ≤ 0.1352 (two-sided); HR = 0.81 (supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Results

Patients

From 8 May 2012 to 1 July 2016, 960 patients with RCC were screened; 222 patients were considered screen failures, and 14 patients were not assigned (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Overall, 724 patients (n = 363 and n = 361, axitinib and placebo arms, respectively) from 128 centers were randomized and included in the ITT population. Of these, 356 and 359 patients received at least one dose of axitinib and placebo, respectively (i.e. as-treated population). Permanent treatment discontinuations occurred in 204 (57%) axitinib-treated and 176 (49%) placebo-treated patients. Reasons for treatment discontinuation in axitinib and placebo arms included recurrence/secondary malignancy (15% and 23%), AEs (19% and 5%), and withdrawal of patient consent (13% and 10%). The trial was stopped due to futility at a preplanned interim analysis at 203 of the required 245 DFS (IRC assessment) events for the final analysis.

A high percentage of the overall study population (n = 724) were Asian (73%) and at highest risk (56%; pT3 with FG ≥3 or pT4 and/or N+, any T, any FG); median age was 58.0 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics: ITT population

| Characteristic, n (%) | Axitinib (n = 363) | Placebo (n = 361) | Total (N = 724) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 280 (77) | 250 (69) | 530 (73) |

| Median (interquartile range) age, years | 58.0 (51–66) | 58.0 (51–66) | 58.0 (51–66) |

| Race | |||

| White | 91 (25) | 90 (25) | 181 (25) |

| Black | 3 (1) | 1 (<1) | 4 (1) |

| Asian | 264 (73) | 267 (74) | 531 (73) |

| Other | 5 (1) | 3 (1) | 8 (1) |

| ECOG PSa | |||

| 0 | 313/356 (88) | 314/358 (88) | 627/714 (88) |

| 1 | 43/356 (12) | 44/358 (12) | 87/714 (12) |

| Risk groupb | |||

| pT2, pN0 or pNx, M0, and ECOG PS 0/1 | 43 (12) | 37 (10) | 80 (11) |

| pT3, pN0 or pNx, M0, and ECOG PS 0/1 | 296 (82) | 297 (82) | 593 (82) |

| pT4, pN0 or pNx, M0, and ECOG PS 0/1 | 7 (2) | 8 (2) | 15 (2) |

| Any pT, pN+, M0, and ECOG PS 0/1 | 17 (5) | 19 (5) | 36 (5) |

| Highest riskc | 209 (58) | 200 (55) | 409 (56) |

| Lower riskd | 146 (40) | 149 (41) | 295 (41) |

As-treated population, all patients who received at least one dose of study drug as reported in patient diaries; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ITT population, intent-to-treat population includes all patients who were randomized, regardless of whether they received study drug.

As-treated population.

Highest-risk and lower-risk of recurrent RCC subpopulations do not equal 100%, as 20 patients from Japan did not have Fuhrman grade (FG) reported.

The highest-risk subpopulation had pT3 with FG ≥3 or pT4 and/or N+, any T, any FG.

The lower-risk subpopulation had pT2 or pT3 with FG ≤2.

Efficacy

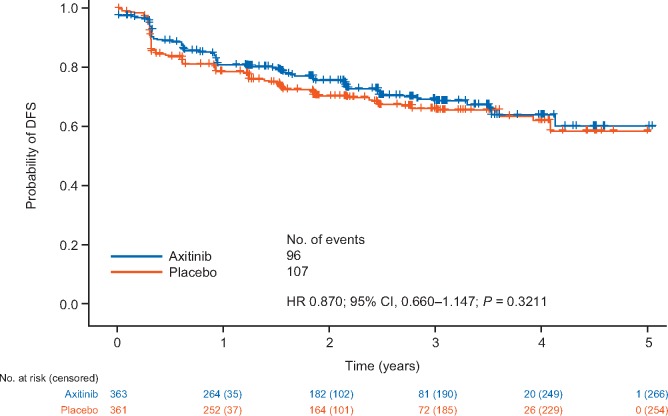

The primary end point of DFS per IRC assessment in the ITT population (HR = 0.870; 95% CI = 0.660–1.147; P = 0.3211) crossed the futility-stopping boundary at 203 events (83% of the required 245 events for the final analyses; n = 96 treated with axitinib and n = 107 with placebo; Figure 1). DFS per investigator showed a larger reduction in risk of an event in the ITT population, although it was not statistically significant (HR = 0.776; 95% CI = 0.599–1.005; P = 0.0536) (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plot of disease-free survival (DFS) in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population according to independent review committee (IRC) assessment. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ITT population, intent-to-treat population includes all patients who were randomized, regardless of whether they received study drug.

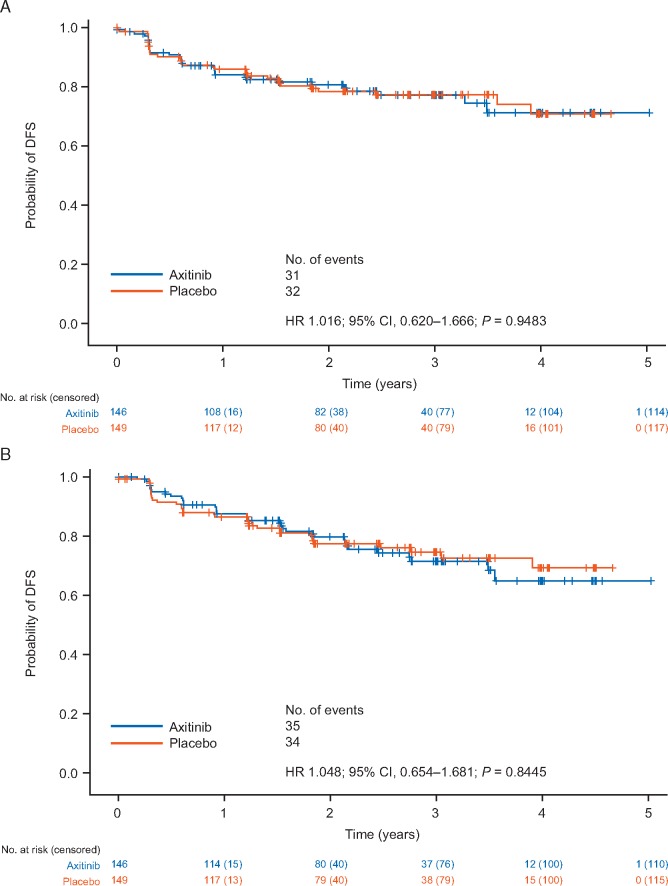

In prespecified subgroup analyses, patients were classified into subpopulations of highest risk (pT3 with FG ≥3 or pT4 and/or N+, any T, any FG) and lower risk (pT2 or pT3 with FG ≤2) of recurrence. No reduction in risk of a DFS event [HR (95% CI)] was observed in the lower-risk subgroup based on IRC [1.016 (0.620–1.666); P = 0.9483] or investigator [1.048 (0.654–1.681); P = 0.8445] assessments (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot of DFS in the lower-risk subpopulation according to (A) IRC assessment and (B) investigator assessment. The subpopulation with lower risk of RCC recurrence had pT2 or pT3 with Fuhrman grade (FG) ≤2. RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

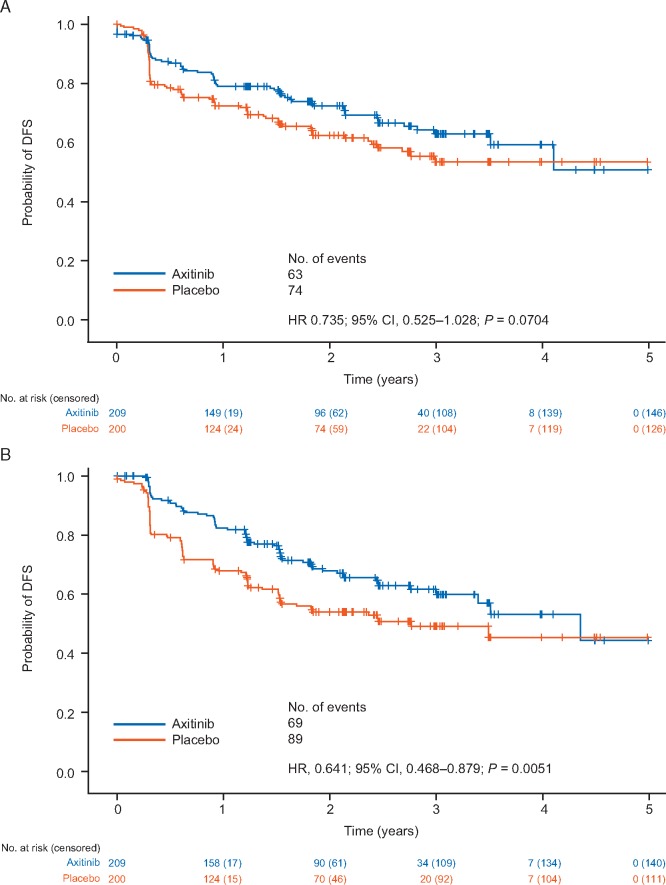

In the subgroup of patients at highest risk of recurrence, a reduction in risk of a DFS event [HR (95% CI)] per IRC [0.735 (95% CI = 0.525–1.028); P = 0.0704] and investigator [0.641 (95% CI = 0.468–0.879); P = 0.0051] was observed (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot of DFS in the higher-risk subpopulation according to (A) IRC assessment and (B) investigator assessment. The subpopulation at highest risk of RCC recurrence had pT3 with FG ≥3 or pT4 and/or N+, any T, any FG.

OS data were not mature at the time of the interim analyses. A total of 28 of 363 (8%) and 26 of 361 (7%) deaths were reported for axitinib and placebo, respectively, in the ITT population [HR = 1.026 (95% CI = 0.600–1.756); P = 0.9246].

Safety

In the axitinib and placebo arms, respectively, 111 (31.2%) and 99 (27.6%) patients were treated for <1 year, 96 (27.0%) and 100 (27.9%) were treated for 1–2 years, 77 (21.6%) and 84 (23.4%) were treated for 2–3 years, and 72 (20.2%) and 76 (21.2%) completed 3 years of treatment.

In axitinib- versus placebo-treated patients, the incidence of AEs (99% versus 92%) and serious AEs (19% versus 14%) were similar; however, more grade 3/4 AEs (61% versus 30%) and discontinuations due to AEs (23% versus 11%) were reported for axitinib. The most common AEs (all-causality) were hypertension (64%) and diarrhea (47%) with axitinib, and hypertension (25%) and nasopharyngitis (18%) with placebo (Table 2). Two (1%) axitinib-treated patients had grade 5 AEs (acute coronary syndrome and suicide). Three (1%) placebo-treated patients had grade 5 AEs: one cardiac arrest, one disease progression, and one gastric cancer. Overall, death occurred in 28 (8%) versus 25 (7%) axitinib-treated versus placebo-treated patients, in the as-treated population; the most common reason was renal cancer (57% versus 52%). One death (acute coronary syndrome) was assessed as related to study treatment.

Table 2.

Summary of most common AEs (all-causality) reported in >10% patients in any treatment group: as-treated population

| AE, n (%) | Axitinib (n = 356) | Placebo (n = 359) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 229 (64) | 88 (25) |

| Diarrhea | 169 (47) | 51 (14) |

| Dysphonia | 150 (42) | 21 (6) |

| Hand-foot syndrome | 115 (32) | 17 (5) |

| Proteinuria | 83 (23) | 24 (7) |

| Fatigue | 75 (21) | 42 (12) |

| Hypothyroidisma | 73 (21) | 19 (5) |

| Arthralgia | 58 (16) | 36 (10) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 57 (16) | 63 (18) |

| Headache | 47 (13) | 41 (11) |

| Increased blood TSHa | 47 (13) | 5 (1) |

| Rash | 46 (13) | 15 (4) |

| Stomatitis | 46 (13) | 9 (3) |

| Back pain | 45 (13) | 54 (15) |

| Decreased appetite | 44 (12) | 7 (2) |

| Asthenia | 41 (12) | 22 (6) |

| Dizziness | 41 (12) | 34 (10) |

Not all patients with an AE of increased blood TSH had a clear diagnosis of hypothyroidism, i.e. presenting other clinical signs.

AE, adverse event; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

More patients treated with axitinib versus placebo reported treatment-related AEs (91% versus 56%), treatment-related serious AEs (7% versus 3%), and treatment-related grade 3 or 4 AEs (49% versus 12%). The most common treatment-related AEs were hypertension (60%) and dysphonia (38%) with axitinib, and hypertension (21%) and diarrhea (8%) with placebo (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The number of patients with AEs leading to dose reductions (56% versus 8%), dose interruptions (51% versus 22%), and permanent discontinuations (23% versus 11%) was greater with axitinib (n = 356) versus placebo (n = 359). The most frequent AEs leading to discontinuation were hypertension (4%), proteinuria (3%), and hand-foot syndrome (2%) in axitinib-treated patients, and increased levels of alanine aminotransferase (1%), arthralgia (1%), and malignant lung neoplasm (1%) in placebo-treated patients.

Discussion

ATLAS was stopped due to futility at a preplanned interim analysis; there was no significant difference in DFS per IRC assessment in the ITT population. In the S-TRAC trial, patients with clear-cell RCC at high risk (≥T3 and/or N+) for tumor recurrence after nephrectomy had significantly longer DFS per IRC with sunitinib versus placebo [7]. ATLAS was designed and initiated before the results from S-TRAC were known; hence, it included patients at lower risk for recurrence. However, prespecified subgroup analyses across risk categories for RCC recurrence were conducted, and in the highest-risk subpopulation, a reduction in risk of a DFS event was seen by both IRC and investigator assessments. Taken together, these results support that patients at highest risk for RCC recurrence benefit from adjuvant treatment.

In contradistinction to S-TRAC, the trials ASSURE [5], PROTECT [6], and other adjuvant-therapy trials in RCC [13] were not successful. Key differences among adjuvant trials must be taken into consideration when comparing results. ASSURE enrolled patients with any histologic subtype of RCC versus patients with clear-cell RCC in PROTECT, S-TRAC, and ATLAS. ASSURE enrolled a higher percentage of patients with ≥T1b tumors, whereas the majority of patients in ATLAS and PROTECT had ≥pT3 tumors, and S-TRAC enrollment was restricted to ≥pT3 tumors, i.e. patients considered to be at highest risk of recurrent RCC. Additionally, ATLAS and PROTECT used TNM and FG risk criteria versus the modified UCLA Integrated Staging System risk criteria of ASSURE and S-TRAC [5–7]. These differences highlight the need for more standardized definitions of ‘risk of recurrence,’ and utilizing those that incorporate molecular features, such as ClearCode34 and the 16-gene recurrence score [14, 15].

Other important aspects of these adjuvant RCC trials are starting dose, drug exposure, and dose maintenance. There were a greater number of axitinib dose reductions due to AEs in ATLAS (56%) in adjuvant RCC versus patients with metastatic RCC in AXIS (27%); however, the number of axitinib dose interruptions due to AEs was similar between the two trials (51% versus 55%) [8]. The starting doses of sunitinib/sorafenib (ASSURE) and pazopanib (PROTECT) were reduced midtrial. Additionally, sunitinib dose reductions to 25 mg were permitted in ASSURE versus 37.5 mg in S-TRAC; thus, patients in S-TRAC had a greater median cumulative dose of sunitinib [5–7]. The relationship between exposure and efficacy was evident in PROTECT, wherein patients treated with pazopanib 800 mg/day had a greater risk reduction in DFS versus 600-mg/day treatment: 31% versus 14% [6]. A recent analysis of PROTECT demonstrated that pazopanib exposure (Ctrough), rather than prescribing dose, was crucial for improved DFS in adjuvant RCC, i.e. patients with higher pazopanib Ctrough derived more clinical benefit from adjuvant pazopanib therapy [16]. In the metastatic RCC setting, a relationship between increased exposure and improved clinical outcomes was demonstrated with pazopanib and sunitinib [17, 18]. No pharmacokinetic analysis was carried out in ATLAS, S-TRAC, or ASSURE; however, it is unresolved as to whether potential benefit of adjuvant therapy is driven by a pharmacodynamic benefit, by drug exposure measured by pharmacokinetics and/or by dosage. Given the unique dosing regimen for axitinib, which allows for titrating of dose up and down, further exploration of dosage parameters as a determinant of DFS is necessary.

In the current ATLAS trial, a greater number of AEs, serious AEs, grade 3/4 AEs, and discontinuations due to AEs were reported in the axitinib group versus placebo. However, AEs were largely managed through dose reductions and interruptions. The ATLAS trial consisted of 73% Asian patients, and as with other studies of axitinib in Asian patients with metastatic RCC [19, 20], the type of AEs was similar, but incidence rate was slightly different versus non-Asian patients. Further potential analyses include assessment of outcome and toxicity in Asian patients compared with other groups in this trial. Overall, 23% of patients treated with axitinib discontinued treatment due to AEs, most frequently due to hypertension, proteinuria, and hand-foot syndrome. In comparison, treatment discontinuation due to AEs occurred in 28% of patients treated with sunitinib (S-TRAC) [7], 44% with sunitinib and 45% with sorafenib (ASSURE) [5], and 35% with pazopanib 600 mg/day and 39% with 800 mg/day (PROTECT) [6]. The axitinib safety profile in ATLAS was consistent with previous trials, and no new safety signals were detected.

A potential limitation of the ATLAS trial is the limited follow-up duration. Of note, the majority of patients were Asian, thus the efficacy and safety outcomes observed in this trial may not be generalized to other ethnic populations. The results from ATLAS, S-TRAC, ASSURE, and PROTECT highlight that it is important to identify, based on clinical or genetic features, those patients who are most likely to benefit from treatment in the adjuvant RCC setting. Additionally, the impact of exposure, treatment duration, and dose modifications on clinical outcomes should be considered during adjuvant therapy. Ongoing trials are assessing the utility of sorafenib (SORCE), everolimus (EVEREST), and immune checkpoint inhibitors (PROSPER, IMmotion010, KEYNOTE-564, and CheckMate 914). Results from these trials may provide clarification on the future of adjuvant treatment of RCC and whether angiogenesis inhibition is the key mechanism to obtain a reduction in risk of relapse after nephrectomy.

Conclusions

The ATLAS trial was stopped due to futility at a preplanned interim analysis. There was no significant difference in DFS per IRC. Subgroup results based on risk groups were explored wherein reduction in risk of event was observed in the subpopulation at highest risk of recurrent RCC, but not in the lower-risk subpopulation. No new safety signals were seen in patients at high risk of recurrent RCC treated with adjuvant axitinib.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Mahgull Thakur (Safety Risk Lead, Pfizer) for her support in the interpretation of the safety findings and for critically reviewing the manuscript. Medical writing support was provided by Anne Marie McGonigal, PhD, and Vardit Dror, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions, and funded by Pfizer.

Data sharing statement: Upon request, and subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions (see https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information), Pfizer will provide access to individual de-identified participant data from Pfizer-sponsored global interventional clinical studies conducted for medicines, vaccines, and medical devices (1) for indications that have been approved in the United States and/or Europe or (2) in programs that have been terminated (i.e. development for all indications has been discontinued). Pfizer will also consider requests for the protocol, data dictionary, and statistical analysis plan. Data from Pfizer trials may be requested 24 months after study completion. The de-identified participant data will be made available via a secure portal to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, and for which an exception does not apply. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Pfizer.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc and SFJ Pharmaceuticals.

Disclosure

MG-G received honoraria from and provided advisory board services to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ipsen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. ME has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Novartis, and Ono Pharmaceuticals. VM has provided advisory board services to Argos, Janssen, Merck, and Pfizer. RDB and RL are employees of SFJ Pharmaceuticals. MC, BR, ML, and OV are employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc. EG has received honoraria for ad boards, meetings and/or lectures from Pfizer, BMS, IPSEN, Roche, Eisai, Eusa Pharma, MSD, Sanofi-Genzyme, Adacap, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Lexicon and Celgene; and received unrestricted research grants from Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, MTEM/Threshold, Roche, IPSEN and Lexicon. DIQ has provided advisory board services for Pfizer, Bayer, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Exelixis, Genentech, Roche, AstraZeneca, and Astellas. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Note: Abstract and oral presentation at ESMO 2018.

References

- 1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: kidney cancer. 2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf (19 June 2018, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. American Cancer Society. Survival rates for kidney cancer by stage. 2018. https://www.cancer.org/content/cancer/en/cancer/kidney-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html (23 April 2018, date last accessed).

- 3. Janzen NK, Kim HL, Figlin RA, Belldegrun AS.. Surveillance after radical or partial nephrectomy for localized renal cell carcinoma and management of recurrent disease. Urol Clin North Am 2003; 30(4): 843–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lam JS, Shvarts O, Leppert JT. et al. Postoperative surveillance protocol for patients with localized and locally advanced renal cell carcinoma based on a validated prognostic nomogram and risk group stratification system. J Urol 2005; 174(2): 466–472; discussion 472; quiz 801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haas NB, Manola J, Uzzo RG. et al. Adjuvant sunitinib or sorafenib for high-risk, non-metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (ECOG-ACRIN E2805): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016; 387(10032): 2008–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Motzer RJ, Haas NB, Donskov F. et al. Randomized phase III trial of adjuvant pazopanib versus placebo after nephrectomy in patients with localized or locally advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(35): 3916–3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ravaud A, Motzer RJ, Pandha HS. et al. Adjuvant sunitinib in high-risk renal-cell carcinoma after nephrectomy. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(23): 2246–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P. et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011; 378(9807): 1931–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hutson TE, Lesovoy V, Al-Shukri S. et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(13): 1287–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rini BI, Melichar B, Ueda T. et al. Axitinib with or without dose titration for first-line metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised double-blind phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(12): 1233–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Atkins MB, Plimack ER, Puzanov I. et al. Axitinib in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced renal cell cancer: a non-randomised, open-label, dose-finding, and dose-expansion phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19(3): 405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K. et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA 2012; 307(12): 1265–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Janowitz T, Welsh SJ, Zaki K. et al. Adjuvant therapy in renal cell carcinoma-past, present, and future. Semin Oncol 2013; 40(4): 482–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rini B, Goddard A, Knezevic D. et al. A 16-gene assay to predict recurrence after surgery in localised renal cell carcinoma: development and validation studies. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(6): 676–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brooks SA, Brannon AR, Parker JS. et al. ClearCode34: a prognostic risk predictor for localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2014; 66(1): 77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sternberg C, Donskov F, Haas NB. et al. Pazopanib exposure relationship with clinical efficacy and safety in the adjuvant treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2018; 24(13): 3005–3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suttle AB, Ball HA, Molimard M. et al. Relationships between pazopanib exposure and clinical safety and efficacy in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2014; 111(10): 1909–1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Houk BE, Bello CL, Poland B. et al. Relationship between exposure to sunitinib and efficacy and tolerability endpoints in patients with cancer: results of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic meta-analysis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2010; 66(2): 357–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sheng X, Bi F, Ren X. et al. First-line axitinib versus sorafenib in Asian patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: exploratory subgroup analyses of Phase III data. Future Oncol 2018. Jul 30 [epub ahead of print], doi:10.2217/fon-2018-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomita Y, Fukasawa S, Oya M. et al. Key predictive factors for efficacy of axitinib in first-line metastatic renal cell carcinoma: subgroup analysis in Japanese patients from a randomized, double-blind phase II study. Japanese J Clin Oncol 2016; 46(11): 1031–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.