Abstract

Histone posttranslational modifications (PTMs) are associated with epigenetic states that form the basis for cell type specific gene expression1,2. Once established, histone PTMs can be maintained by positive feedback involving enzymes that recognize and catalyze the same modification on newly deposited histones. Recent studies suggest that in wild-type cells, histone PTM-based positive feedback is too weak to mediate epigenetic inheritance in the absence of other inputs3–7. RNAi-mediated histone H3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me) and heterochromatin formation define a potential epigenetic inheritance mechanism in which positive feedback involving small interfering RNA (siRNA) amplification can be directly coupled to histone PTM positive feedback8–14. However, it remains unknown whether such a coupling of two feedback loops can maintain epigenetic silencing independently of DNA sequence and in the absence of enabling mutations that disrupt genome-wide chromatin structure or transcription15–17. Here using fission yeast S. pombe, we show that siRNA-induced H3K9me and silencing of a euchromatic gene can be epigenetically inherited in cis during multiple mitotic and meiotic cell divisions in wild-type cells. This inheritance involves the spreading of secondary siRNAs and H3K9me3 to the targeted gene and surrounding areas and requires both RNAi and H3K9me, suggesting that siRNA and H3K9me positive feedback loops act synergistically to maintain silencing. In contrast, when maintained solely by histone PTM positive feedback, silencing is erased by H3K9 demethylation promoted by Epe1, or by interallelic interactions following mating to cells containing an expressed epiallele even in the absence of Epe1. These findings demonstrate that the RNAi machinery can mediate transgenerational epigenetic inheritance independently of DNA sequence or enabling mutations and reveal a role for the coupling of siRNA and H3K9me positive feedback loops in protection of epigenetic alleles from erasure.

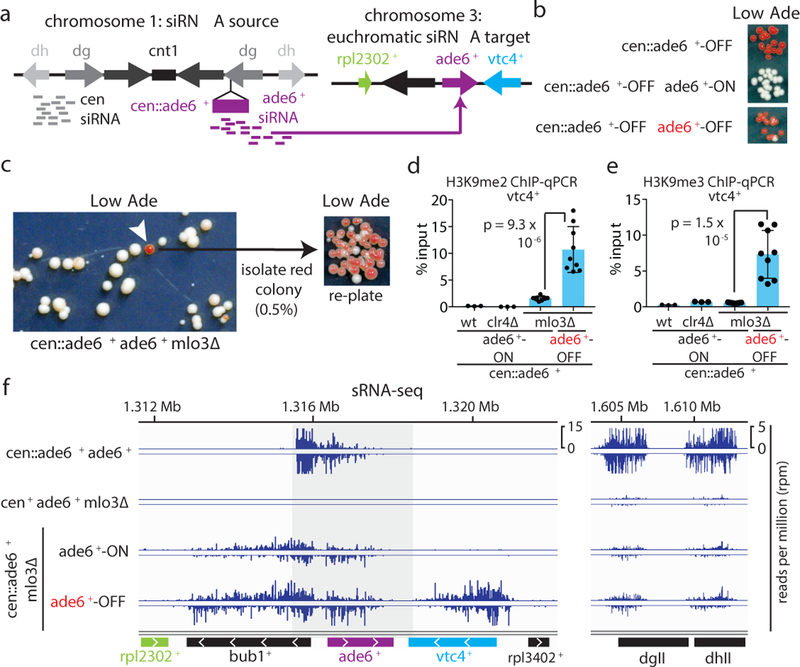

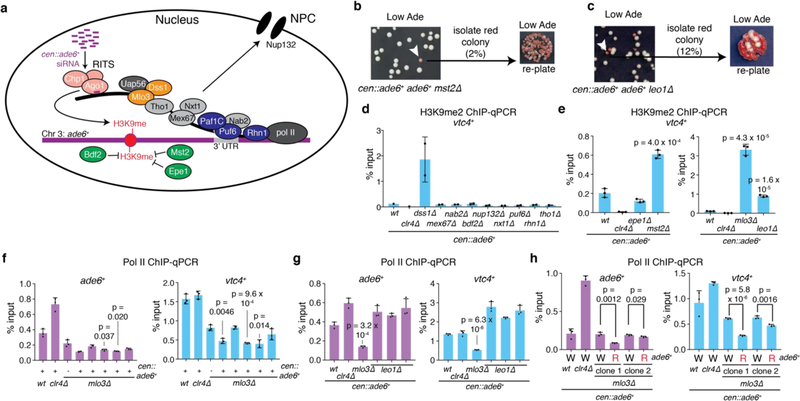

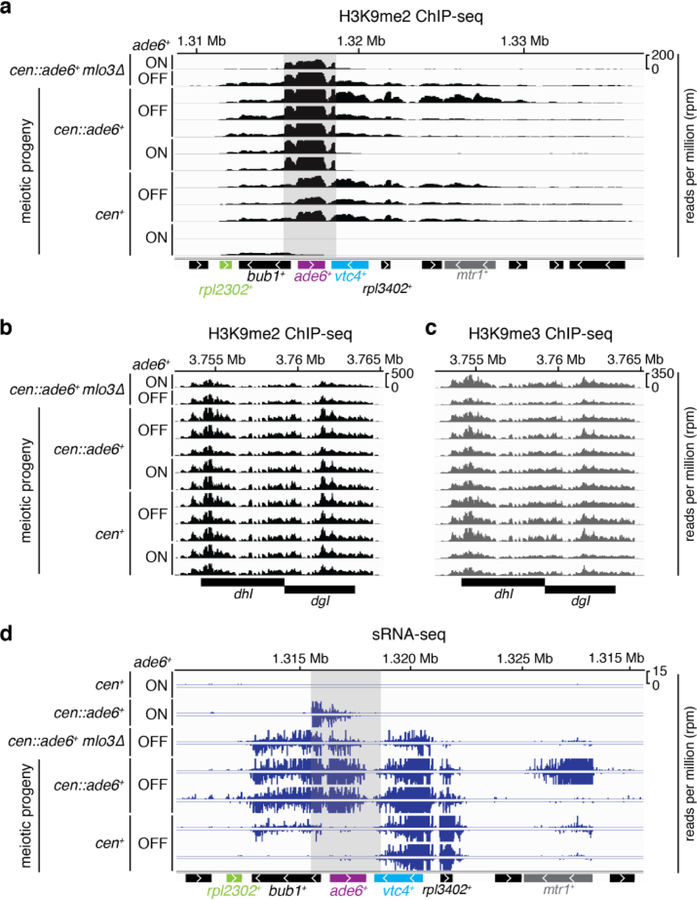

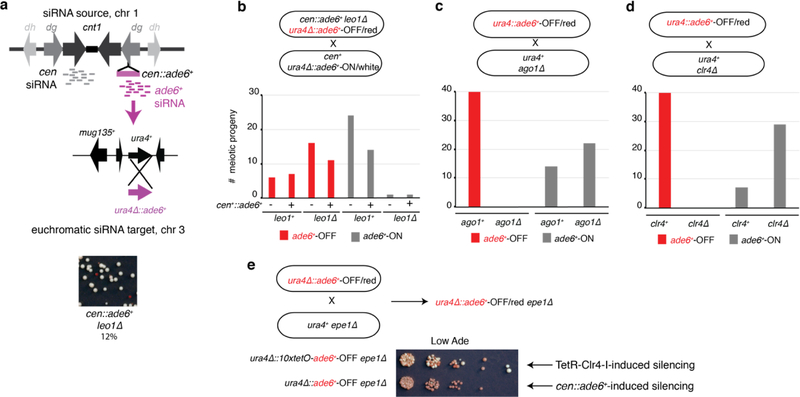

To determine whether siRNA positive feedback loops participate in allele-specific inheritance of epigenetic states, we used a cen::ade6+ transgene, which is epigenetically silenced and produces abundant ade6+ siRNAs (Fig. 1a)10,18. Silencing of ade6+ causes cells to grow red on medium with limiting adenine (Low Ade) (Fig. 1b, top), providing a visual assay for silencing. Previous studies have shown that the ability of siRNAs to mediate de novo silencing in trans is antagonized by mRNA 3’UTR processing pathways16,17. Consistently, we found that a second copy of ade6+ located at its native euchromatic locus (hereafter referred to as ‘endogenous ade6+’) remained refractory to silencing by siRNAs produced from the cen::ade6+ transgene, as cells with both copies of ade6+ always formed white colonies (Fig. 1b, middle). However, deletion of a subset of genes that influence mRNA transcription, 3’ end processing, or export resulted in the appearance of red colonies at a frequency of 0.5–12%, indicating establishment of silencing at the endogenous ade6+ allele (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 1a-c, white arrows). These included deletions of mlo3+ and dss1+, subunits of the conserved UAP56 mRNA export complex19, histone acetyltranferase mst2+, and leo1+, a member of the Paf1 complex that negatively regulates RNAi-mediated silencing17. When isolated and re-plated, these red colonies produced mostly red colonies (~85%, Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig 1b-c), indicating that the silent state was stably inherited. Silencing was accompanied by spreading of H3K9me at the endogenous ade6+ locus into the adjacent vtc4+ gene (Fig. 1d-e; Extended Data Fig. 1d-e). Furthermore, as expected for H3K9me3-mediated transcriptional gene silencing, we observed reduced RNA pol II occupancy at vtc4+ that was specifically associated with ade6+-OFF/red cells relative to non-silenced white control cells (Extended Data Fig. 1f-h).

Figure 1 |. Establishment of siRNA-mediated silencing at the euchromatic ade6+ locus is associated with local siRNA generation and H3K9 methylation.

a, Schematic of the cen::ade6+ siRNA driver (left) and euchromatic ade6+ target (right) loci.

b, Expected phenotypes of cells containing the silenced cen::ade6+ locus alone or in combination with the euchromatic ade6+ in either expressed (ON/red) or silenced (OFF/red) states.

c, cen::ade6+ mlo3∆ cells were plated on low adenine medium. ~0.5% of cells formed red or pink colonies, indicating silencing of euchromatic ade6+ (white arrow). Repeated three times with similar results.

d-e, ChIP-qPCR assays showing H3K9me2 (d) or H3K9me3 (e) in ade6+-OFF (red) compared to ade6+-ON (white) cells at vtc4+. Sample means +/− SD from 3 (wt, clr4∆) or 9 (mlo3∆) biological replicates (reflecting 3 independent clones); p values resulting from a 2-tailed Student’s t-test.

f, Left, siRNA-sequencing showing increased secondary siRNA generation in ade6+-OFF compared to ade6+-ON cells. Note that for the ade6+ gene itself and the immediately flanking sequences, the siRNA and H3K9me signals at the euchromatic and centromeric copies cannot be distinguished (shaded area represent sequence identity). Right, siRNAs mapping to the pericentromeric repeats (dgII and dhII) of chromosome 2 shown as controls. Sequencing was performed once but see Fig. 3e, ED Fig. 3d, and ED Fig 8d for related results.

To further investigate the mechanism of ade6+ silencing, we determined whether trigger cen::ade6+ siRNAs induced the generation of secondary siRNAs at endogenous ade6+ by small RNA sequencing (sRNA-seq) in cen::ade6+ ade6+ mlo3∆ cells that expressed (ON/white) or silenced (OFF/red) ade6+. As shown in Fig. 1f, we observed spreading of siRNAs outside the region of homology with cen::ade6+ (denoted by the grey shaded area) for both the ON and OFF epigenetic states, but siRNAs only spread to adjacent vtc4+ in ade6+-OFF cells. We observed no siRNA spreading in cen::ade6+ ade6+ or cen+ ade6+ mlo3∆ cells, indicating that the biogenesis of secondary siRNAs required trigger centromeric ade6+ siRNAs and mlo3∆ (Fig. 1f, top 2 tracks). siRNA spreading correlated with the spreading of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 into vtc4+ only in ade6+-OFF cells (Fig. 1d-e). These results indicate that in mlo3∆ cells, siRNAs produced from a centromeric transgene can act in trans to silence a euchromatic copy of the gene, and that this silencing is accompanied by the generation of euchromatic secondary siRNA and H3K9me. Furthermore, even though silencing is established at a low frequency, it is maintained at a high frequency, suggesting that maintenance of silencing involves epigenetic memory.

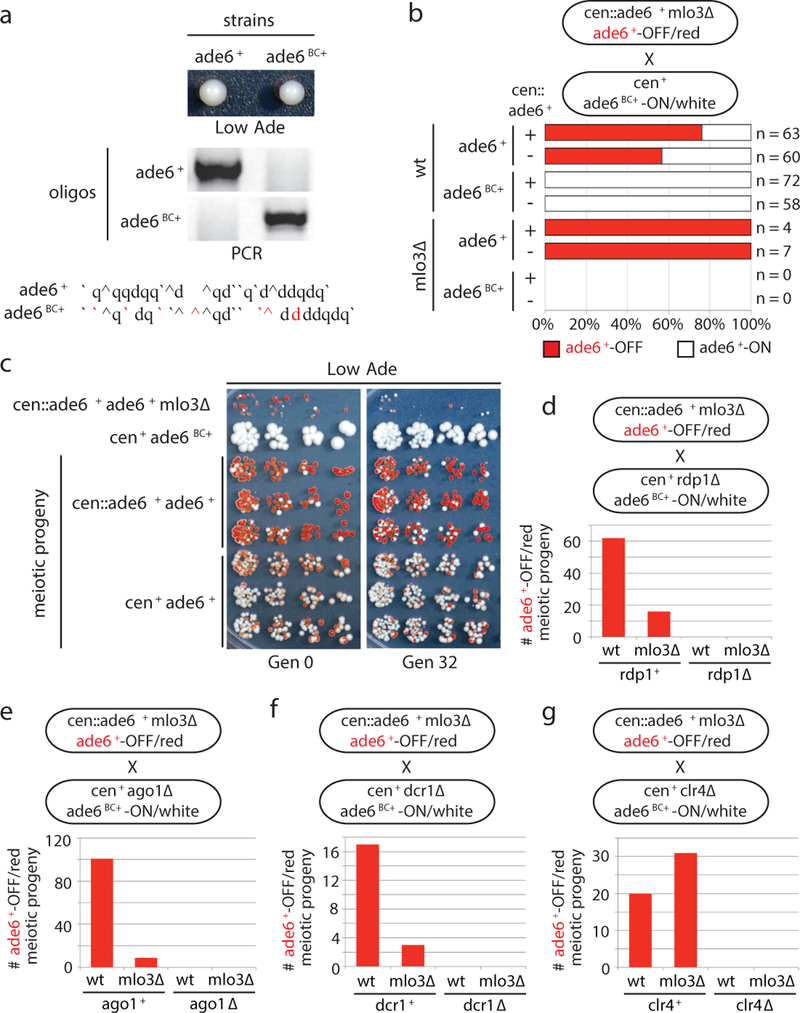

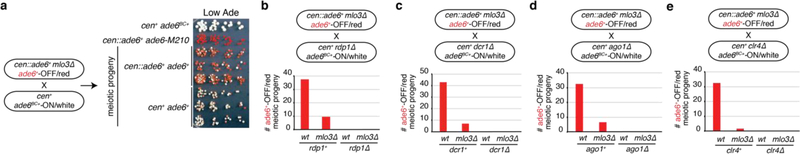

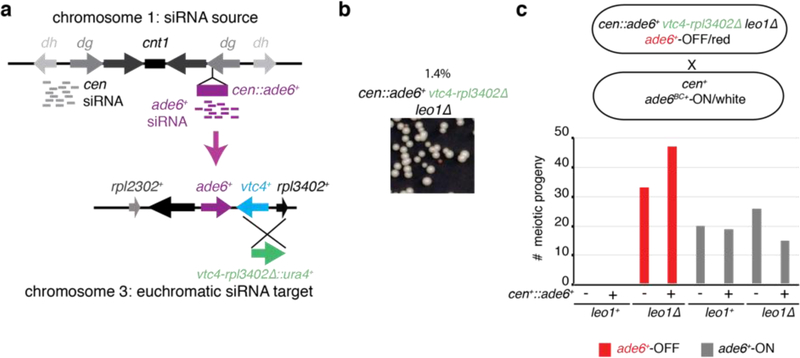

To investigate whether epigenetic memory at the endogenous ade6+ locus could be maintained in the absence of the mlo3∆ enabling mutation or cen::ade6+ siRNAs, we introduced silent mutations into the endogenous ade6+ allele (ade6BC+, barcoded allele) so that it could be distinguished from cen::ade6+ or ade6+ by PCR (Fig. 2a). We crossed cen::ade6+ mlo3∆ ade6+-OFF/red to cen+ ade6BC+-ON/white cells and analyzed the haploid meiotic progeny. As shown in Fig. 2b-c and Extended Data Fig. 2a, the OFF state was stably transmitted to wild-type progeny, whether cen::ade6+ was present or not. Furthermore, the acquired silent state was remarkably stable, as nearly 50% of the cen+ ade6+ cells remained red after 32 generations (Fig. 2c, right). Importantly, analysis of the red and white progeny by allele-specific PCR showed that all OFF/red progeny of the cross contained the parental ade6+-OFF allele, indicating that the silent state was transmitted in an allele-specific manner (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2 |. Maintenance of acquired silencing in wild-type cells and its dependence on RNAi and Clr4.

a, Top, the barcoded ade6BC+ allele was functional as shown by formation of a white colony on Low Ade medium; ade6+ served as a control. Bottom, sequences of the ade6+ and ade6BC+ alleles, base changes indicated in red. Allele-specific PCRs distinguish barcoded and wild-type alleles. Repeated >10 times with similar results.

b, cen::ade6+ ade6+-OFF mlo3∆ cells were crossed to cen+ ade6BC+-ON cells followed by random spore analysis (RSA). The frequency with which silencing in the progeny with the indicated genotypes was maintained is shown. n, number of progeny analyzed. Repeated 3 times.

c, The progeny from the cross in panel b were grown for 0 or 32 generations and plated on Low Ade medium. Heritable silencing, as indicated by the growth of red/pink colonies, for both cen+ and cen::ade6+ progeny is apparent for 32 generations. Performed once, see ED Fig. 2a for related results.

d-g, cen::ade6+ mlo3∆ ade6+-OFF cells were crossed to cen+ mlo3+ ade6BC+-ON cells with deletions of key RNAi components (d-f), or H3K9 methyltransferase clr4+ (g), followed by RSA. All ade6+-OFF progeny were RNAi+ and clr4+. Bars indicate number of ade6+-OFF meiotic progeny for each genotype. Repeated in ED Fig. 2b-e with similar results.

To determine the genetic requirements for maintenance of the silent allele, we performed the above cross with cells lacking key RNAi genes (ago1∆, dcr1∆, rdp1∆) or the H3K9 methyltransferase (clr4∆). The results indicated that silencing of endogenous ade6+ required both the RNAi pathway and Clr4 (Fig. 2d-g and Extended Data Fig 2b-e, no red ago1∆, dcr1∆, rdp1∆ or clr4∆ progeny). Thus cis silencing of ade6+ is maintained epigenetically by an RNAi- and H3K9 methylation-dependent mechanism, independently of the initial cen::ade6+ siRNA trigger or any mutation that disrupts normal RNA processing.

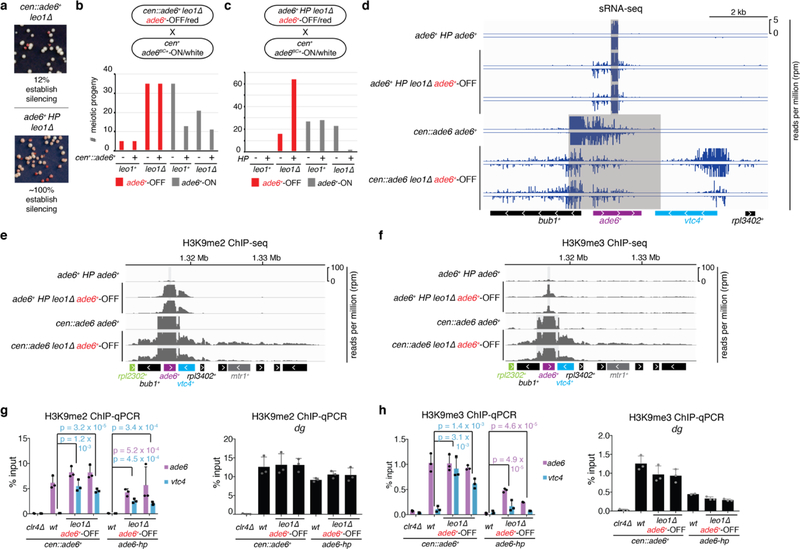

Epigenetic inheritance of a trp1+::ade6+ transgene, induced by hairpin siRNAs targeting ade6+, has been previously observed in the absence of the hairpin trigger, but remained strictly dependent on enabling mutations in leo1+ or other Paf1 subunits17. In contrast, here we observed epigenetic inheritance of ade6+ silencing in the absence of both an enabling mutation and trigger siRNAs (Fig. 2). To investigate whether differences in the siRNA trigger or the enabling mutation account for the difference in heritability, we compared maintenance of silencing at the endogenous ade6+ locus using either cen::ade6+ or hairpin ade6+ trigger siRNAs in leo1∆ cells. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 3a, both siRNA triggers induced endogenous ade6+ silencing. We crossed cells with the above silent ade6+ alleles to cells lacking both the siRNA trigger and the enabling leo1∆ mutation and examined silencing in the meiotic progeny. In contrast to cen::ade6+-triggered silencing, hairpin-triggered ade6+ silencing was lost in the leo1+ segregants (Extended Data Fig. 3b-c). Furthermore, unlike cen::ade6+, which induced a broad domain of secondary siRNAs, the hairpin triggered very low levels of secondary siRNAs that were restricted to the ade6+ coding region (Extended Data Fig. 3d). ChIP-seq and ChIP-qPCR experiments showed that unlike the cen::ade6+ trigger, which induced broad domains of H3K9 methylation at the ade6+ locus, the hairpin trigger induced more restricted domains (Extended Data Fig. 3e-h). In particular, H3K9me3 levels were very low when silencing was induced by the hairpin and did not extend significantly beyond ade6+ (Extended Data Fig. 3f, h). In this regard, we recently demonstrated that H3K9me3 is required for transcriptional gene silencing and epigenetic inheritance, while H3K9me2 is sufficient for RNAi-mediated co-transcriptional gene silencing20. We therefore conclude that the nature of the siRNA trigger, but not the enabling mutation, plays a critical role in spreading of secondary siRNAs and H3K9me that determines heritability of the epiallele.

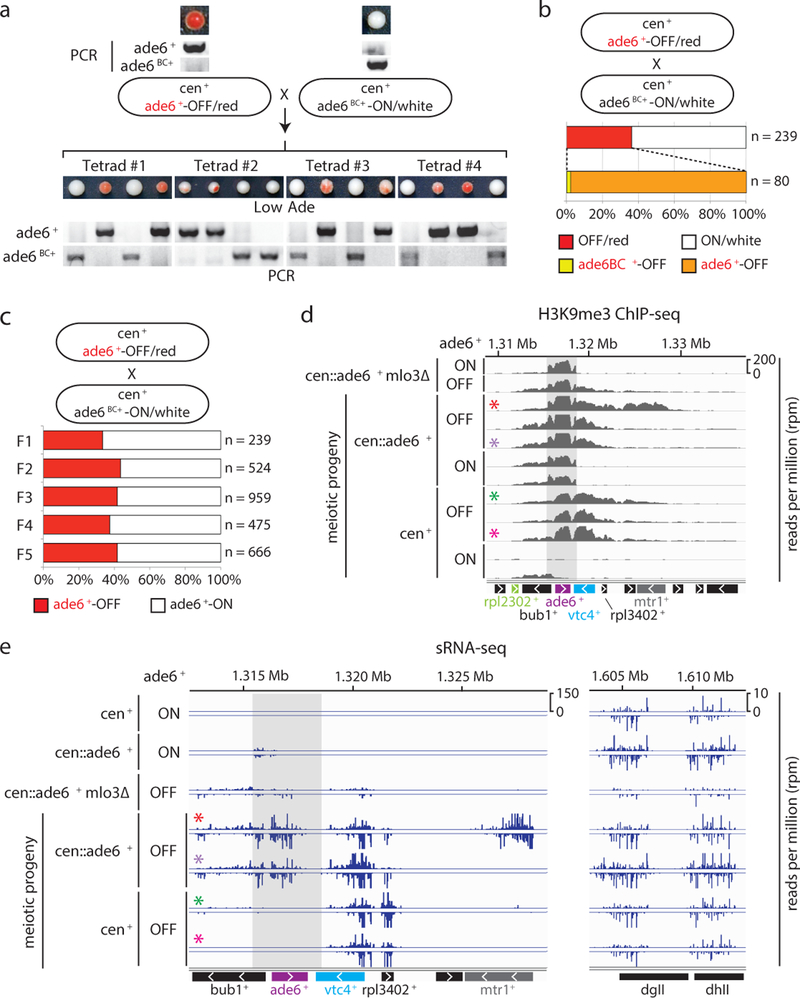

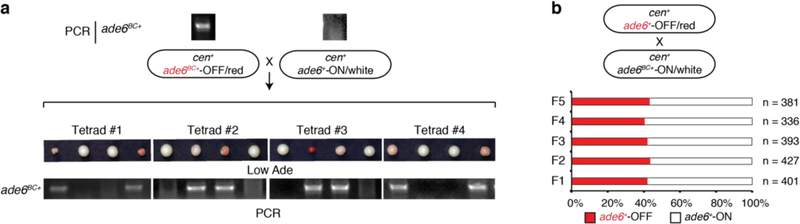

Epigenetic states in yeast and animal cells can be transmitted in cis during cell division21,22. To address whether the siRNA positive feedback loop, which generates high levels of siRNA that can potentially act globally, could discriminate between identical target sequences to mediate cis (allele-specific) inheritance of epigenetic states, we took advantage of the ade6BC+ allele, which is genetically identical to ade6+ except for a few silent nucleotide substitutions (Figure 2a). We crossed wild-type cells carrying the siRNA-dependent ade6+-OFF allele to wild-type cells carrying the ade6BC+-ON allele (Fig. 2d-g, Fig. 3a), analyzing the meiotic progeny to determine whether silencing was inherited in an allele-specific manner. As shown in Fig. 3a, the OFF/red and ON/white expression states segregated with a 2:2 Mendelian ratio. Moreover, allele-specific PCR showed that the OFF/red progeny contained the parental ade6+-OFF allele and the ON/white progeny contained the parental ade6BC+-ON allele, indicating that each state was stably and independently transmitted following meiosis. To rule out any role for the ade6BC+ nucleotide substitutions, we performed the reciprocal cross and observed the same 2:2 segregation phenotype with faithful maintenance of the parental OFF allele (Extended Data Fig. 4a). In agreement with the tetrad dissection data, random spore analysis showed that 97.5% of OFF/red progeny contained the parental OFF allele (Fig. 3b). These results therefore demonstrate that an acquired silent state can be preferentially propagated in cis as an epiallele by an siRNA-dependent mechanism. The acquired silent state was furthermore stable through multiple meiotic cell divisions (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig 4b). This, together with the continuous dependence of silencing on RNAi (Fig. 2d-f), suggests that maintenance of silencing and heterochromatin relies on a continuous RNAi-dependent amplification mechanism.

Figure 3 |. Cis inheritance of the silent ade6+ epiallele and its association with H3K9me3 and secondary siRNA generation.

a, ade6+-OFF cells crossed to ade6BC+-ON cells, followed by tetrad dissection on Low Ade medium (top) and genotyping using allele-specific PCRs (bottom), showed the 2:2 segregation of the OFF and ON states and cis transmission of each state. See ED Fig. 4a for the reciprocal cross showing similar results.

b, ade6+-OFF cells were crossed to ade6BC+-ON cells, followed by random spore analysis. 80 out of 220 haploid meiotic progeny (36%) maintained silencing of ade6+, largely in cis (78 out of 80 cells). Repeated 3 times with similar results.

c, ade6+-OFF progeny of repeated ade6+-OFF x ade6BC+-ON crosses were selected and crossed again, showing stability of the ade6+-OFF allele over five meiotic generations. n, number of meiotic progeny analyzed. Repeated with similar results in ED Fig 4b.

d, H3K9me3 ChIP-seq reads mapping to the euchromatic ade6+ locus in cells with the indicated genotypes and expression states. Colored asterisks indicate ChIP- and sRNA- sequencing (shown in panel e) of the same clones. Shaded area, region of sequence identity with cen::ade6+. 2–3 independent clones were analyzed for each ON and OFF meiotic progeny.

e, sRNA-seq reads mapping to the ade6+ locus in cells with the indicated genotypes and expression states at the euchromatic ade6+ locus (left) and the pericentromeric repeats of chromosome 2 (dgII and dhII) (right). Shaded area and colored asterisks as described in panel d legend. 2 independent clones were analyzed for each OFF progeny.

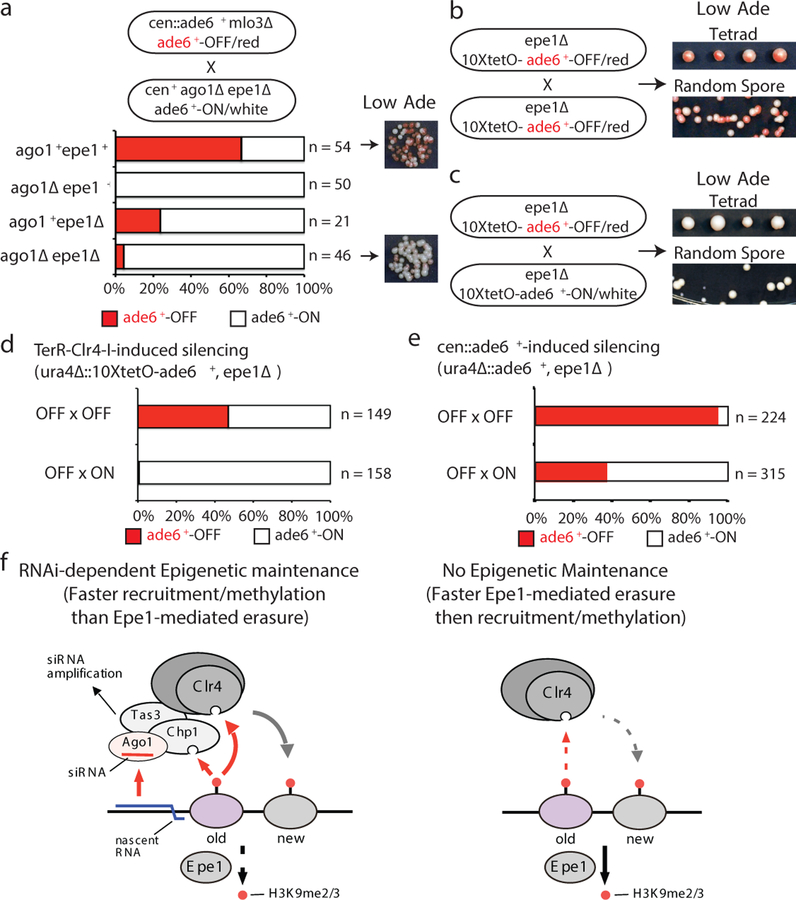

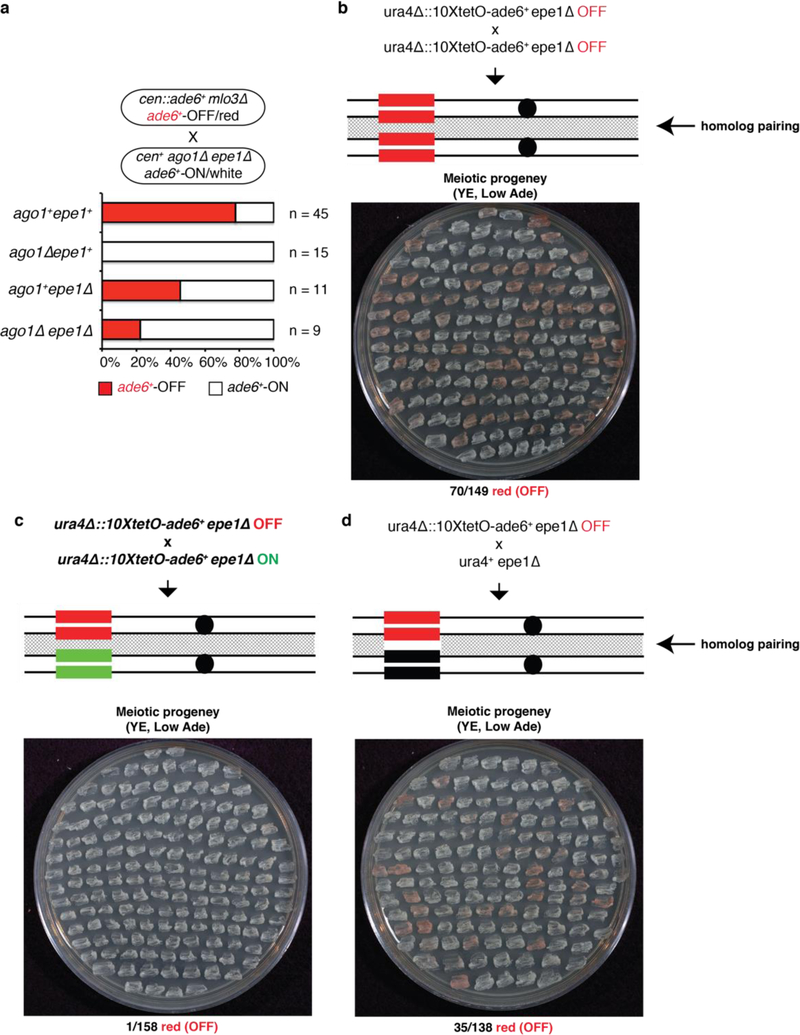

Figure 4 |. RNAi protects an acquired silent state against erasure by Epe1 or activation by an expressed homologous allele.

a, cen::ade6+ mlo3∆ ade6+-OFF cells were crossed to cen+ ago1∆ epe1∆ ade6+-ON cells, followed by random spore analysis. Number and phenotype of mlo3+ progeny with the indicated genotypes and phenotypes are shown. mlo3∆ progeny were excluded. On the right, growth on Low Ade medium indicated meiotic progeny showing maintenance of the ade6+-OFF state in ago1∆ epe11∆ cells. All ago1∆ epe1+ progeny formed white colonies indicating loss of the silent state. n, number of meiotic progeny analyzed.

b-d, epe1∆ ura4∆::10xtetO-ade6+-OFF cells were crossed to either epe1∆ ura4∆::10xtetO-ade6+-OFF (b) or epe1∆ ura4∆::10xtetO-ade6+-ON (c) cells, followed by tetrad dissection (top) or random spore analysis (bottom). Quantification of ON and OFF states in the progeny is shown in d. Silencing was initiated by siRNA-independent TetR-Clr4-I. n, total progeny.

e, Mating of a ura4∆::ade6+-OFF epe1∆ allele with either an OFF or ON allele, followed by diploid formation and sporulation (meiosis), showing that when silencing is established in an siRNA-dependent manner (cen::ade6+ leo1∆), the OFF state is protected from pairing-induced erasure. n, total progeny.

f, Model for the role of RNAi in allele-specific epigenetic inheritance. Left, the siRNA-programmed RITS complex, containing Ago1, Tas3, and Chp1, serves as an epigenetic sensor that maintains allele-specific gene silencing. When both H3K9me and local complementary siRNAs are present, RITS associates with the target locus and recruits the Clr4 methyltransferase complex to methylate histone H3K9 on newly deposited nucleosomes. RITS also promotes local siRNA amplification. Right, in the absence of local RNAi, H3K9me cannot be epigenetically maintained in epe1+ cells.

We next investigated how siRNAs and H3K9me work together to maintain silencing at the ade6+ epiallele. ChIP-seq analysis showed that silencing correlated with high levels of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 at ade6+ and the immediately downstream vtc4+ and rpl3402+ genes (Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 5a, compare OFF and ON tracks for cen+ cells). As controls, centromeric levels of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 were comparable between samples (Extended Data Fig. 5b-c). Thus, consistent with the requirement for the Clr4 H3K9 methyltransferase, the silent ade6+ epiallele was associated with high levels of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3. Sequencing of siRNAs showed that silencing in ade6+-OFF cells correlated with accumulation of vtc4+ and rpl3402+ siRNAs (Fig. 3e, rows 4–7). In cells containing cen::ade6+, we also observed secondary siRNA accumulation upstream of ade6+, to tandem gene bub1+, and about 10kb downstream of ade6+ (Fig. 3e, rows 4–5), which correlated with increased spreading of H3K9me3 (Fig. 3d-e, colored asterisks highlight regions where H3K9me3 and siRNA reads correlate). Surprisingly, in cells lacking cen::ade6+, we observed very few siRNA reads that mapped to ade6+-OFF (Fig. 3e, rows 6–7 and Extended Data Fig. 5d, rows 6–7), and the vast majority of siRNA detected were produced from the adjacent vtc4+ and rpl3402+ genes. We therefore tested whether vtc4+ and rpl3402+ were required for maintenance of the ade6+-OFF state, and found that ade6+ silencing in vtc4-rpl3402∆ cells was only maintained in cells carrying the leo1∆ enabling mutation (Extended Data Fig. 6). These results indicate that an siRNA positive feedback loop, which forms at the adjacent vtc4+ and rpl3402+ genes, is required for epigenetic inheritance of the silent ade6+ epiallele in wild-type cells. Consistent with a requirement for vtc4+ in epigenetic inheritance of ade6+ silencing, secondary siRNAs and H3K9me3 associated with non-heritable hairpin-induced silencing did not spread to the vtc4+ gene (Extended Data Fig. 3). Together with the observation that the silencing activity of siRNAs is restricted to the epiallele that already possesses H3K9me (Fig. 3a, b), these results suggest that the mutual dependence of H3K9me and siRNA generation on each other underlies the mechanism of cis epigenetic inheritance.

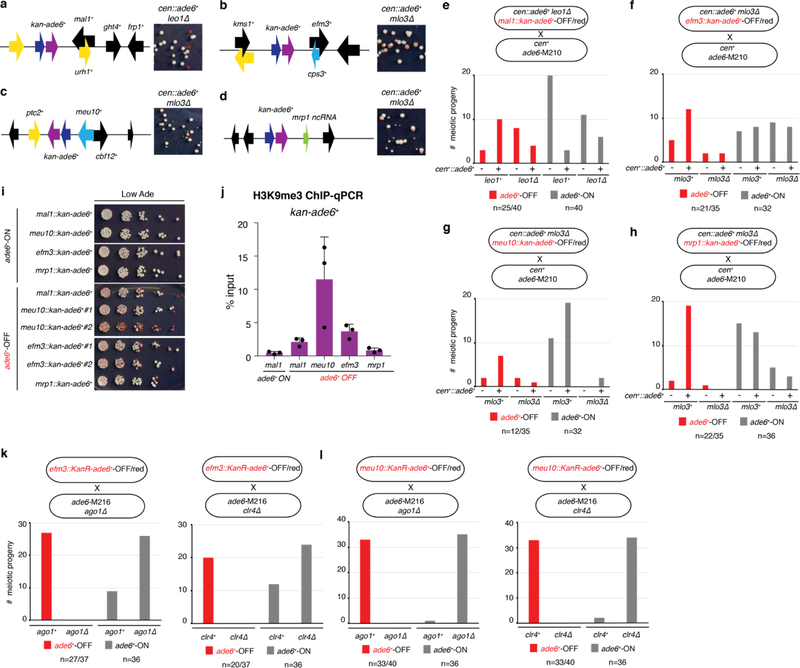

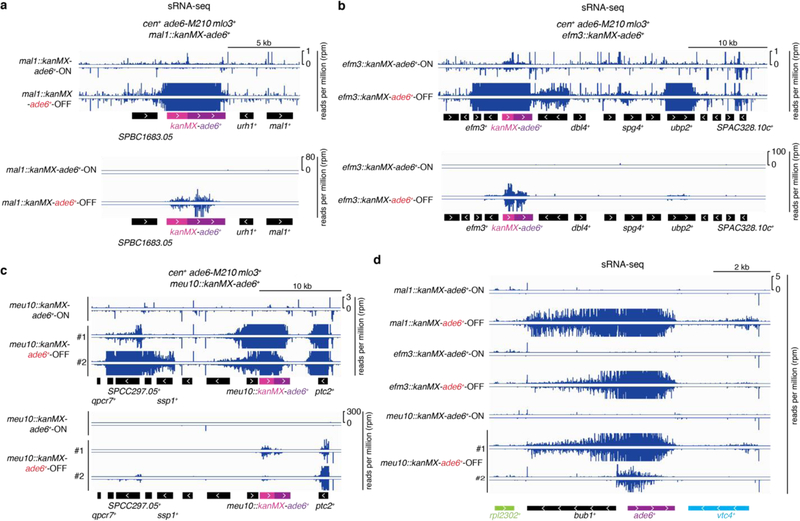

To test possible effects of genomic context on siRNA-triggered silencing and its epigenetic inheritance, we inserted the ade6+ gene together with a selectable marker (KanR-ade6+) at different euchromatic loci in cells containing the cen::ade6+ siRNA trigger and an enabling mutation. We observed silencing at 4 transgene insertions (mal1+::KanR-ade6+, efm3+::KanR-ade6+, meu10+::KanR-ade6+, and mrp1+::KanR-ade6+), indicated by growth of red colonies on low adenine medium (Extended Data Fig. 7a-d). Furthermore, after diploid formation and sporulation, we observed epigenetic maintenance of the OFF state at each locus in meiotic progeny lacking both the siRNA trigger and the enabling mutation (extended Data Fig. 7e-h). The resulting OFF epialleles were stably maintained upon further mitotic propagation (Extended Data Fig. 7i), were associated with H3K9me3 (Extended Data Fig. 7j), and required Ago1 and Clr4 for epigenetic inheritance (efm3+::KanR-ade6+ and meu10+::KanR-ade6+ OFF/red epialleles) (Extended Data Fig. 7k-l). Furthermore, like the euchromatic endogenous ade6+ locus (Fig. 1f), secondary siRNA generation extended to surrounding transcription units specifically in the OFF state (Extended Data Fig. 8). Therefore, the ability of siRNA-coupled H3K9me to mediate epigenetic inheritance is not restricted to a particular locus.

We previously demonstrated that artificial tethering of TetR-Clr4 upstream of an ade6+ gene inserted at the ura4+ locus (ura4∆::10XtetO-ade6+) results in H3K9me and silencing3. This RNAi-independent silencing can be inherited epigenetically after deletion of the TetR-Clr4 initiator, but only when H3K9 demethylation is decreased by deletion of epe1+, which encodes a JmjC domain demethylase family member3,23. We therefore investigated whether deletion of epe1+ could suppress the requirement for RNAi machinery in epigenetic maintenance of the ade6+-OFF state. Crossing cen::ade6+ mlo3∆ ade6+-OFF cells to cen+ ago1∆ epe1∆ ade6+-ON cells produced 46 ago1∆ epe1∆ haploid progeny, 2 of which formed pink or red colonies (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 9a). Upon re-plating, these red colonies formed a mixture of red and white colonies, indicating that deletion of epe1+ partially suppressed the requirement for RNAi in maintenance of the silent ade6+ epiallele (Fig. 4a, right side). In contrast, all ago1∆ epe1+ progeny lost ade6+ silencing, demonstrating that RNAi counteracts Epe1-mediated erasure of the silent ade6+ epiallele.

We next investigated whether the RNAi-independent OFF state of the ura4∆::10XtetO-ade6+ epiallele could be transmitted in cis in cells lacking the TetR-Clr4-I initiator3, as is the case with the RNAi-dependent ade6+-OFF allele (Fig. 3a). Consistent with previous findings3, crossing an epe1∆ ura4∆::10XtetO-ade6+-OFF/red allele to another OFF/red allele produced haploid progeny that retained the OFF/red state at a high frequency (48%, Fig. 4b). However, when we crossed an epe1∆ ura4∆::10XtetO-ade6+-OFF/red allele to a genetically identical epe1∆ ura4∆::10XtetO-ade6+-ON/white allele, the resulting haploid progeny were mostly white, indicating that they had lost the silent state (0.01% ade6+-OFF/red, Fig. 4c, d). Since the OFF x OFF ura4∆::10XtetO-ade6+ cross produces many (48%) ade6+-OFF/red progeny, the epigenetic erasure event in the OFF x ON cross is not caused by a general change in chromatin structure during meiosis and is likely due to the proximity of the OFF and ON alleles during homolog pairing prior to or during meiosis. Consistent with this hypothesis, ura4∆::10XtetO-ade6+ silencing was maintained, although at a lower frequency than in an OFF x OFF cross, in a cross in which we disrupted homolog pairing by replacing 10XtetO-ade6+ with the non-homologous ura4+ gene (Extended Data Fig. 9b-d). To determine whether siRNAs could protect a silent epiallele from homolog-induced erasure, as suggested in OFF x ON crosses involving the RNAi-dependent endogenous ade6+ locus (Fig. 2 and 3), we induced silencing at the ura4∆::ade6+ locus using cen::ade6+ siRNAs instead of TetR-Clr4-I (Extended Data Fig. 10). In contrast to the RNAi-independent TetR-Clr4-I induced ura4∆::10X-tetO-ade6+ silent epiallele, which was erased in the progeny of the OFF x ON cross (Fig. 4d), the siRNA-induced ura4∆::ade6+ silent epiallele was maintained in nearly 40% of the meiotic progeny of the OFF x ON cross (Fig. 4e). Therefore, in addition to protection against Epe1-dependent erasure (Fig. 4a), siRNAs protect a silent epiallele against erasure by an expressed epiallele during homolog pairing.

In summary, our findings reveal that coupling of RNAi and H3K9me can mediate epigenetic inheritance of gene silencing. The role of siRNAs in allele-specific cis maintenance of an epigenetic state in S. pombe can be explained by the dual requirement for both siRNAs and histone H3K9me in recruitment of the RNAi-induced transcriptional silencing (RITS) complex, which in turn recruits Clr4 (Fig. 4f). Recently, a role for site-specific DNA binding proteins in epigenetic maintenance of silent chromatin was also described5–7. In contrast to site-specific DNA binding proteins, the siRNA-dependent epigenetic inheritance mechanism described here acts in a less sequence-dependent manner and can potentially transmit epigenetic silencing at any locus that allows autonomous siRNA amplification. Furthermore, the coupling of siRNA- and H3K9me-dependent recruitment protects the epigenetic state from erasure mechanisms, which may involve either removal of H3K9me by demethylases such as Epe1 or signals from an expressed allele during the pairing of homologous chromosomes. The latter is reminiscent of transvection in Drosophila, in which homolog pairing in diploid somatic cells allows positive regulatory elements on one homolog to activate gene expression on the other24,25. Based on their general requirement for epigenetic inheritance in S. pombe, we propose that specificity factors such as DNA-binding proteins and small or large noncoding RNAs act as important components of most epigenetic inheritance mechanisms.

Methods

Strain Constructions.

S. pombe strains used in this study are described in SI Table 1.

ChIP-qPCR.

ChIP experiments were performed as previously described16, using anti-H3K9me2 (Abcam, ab1220), anti-H3K9me3 (Diagenode, C15500003), and anti-RNA Polymerase II (Covance, 8WG16) antibodies.

Sample preparation for multiplex ChIP-seq.

Libraries for Illumina sequencing were constructed following the manufacturer’s protocols, starting with ~5 ng of immune-precipitated DNA fragments. Each library was generated with custom-made adapters carrying unique barcode sequence at the ligating end26. Barcoded libraries were mixed and sequenced with Illumina HiSeq2000. Raw reads were separated according to their barcodes and mapped to the S. pombe genome using Bowtie. Mapped reads were normalized to reads per million and visualized in IGV.

sRNA-seq.

To purify total sRNAs, cells were grown in 20 ml YES27 to a concentration of ~2×107 cells/ml. Pellets were processed using the mirVana™ miRNA Isolation kit (Ambion), and the resulting RNA used for library construction. Total small RNA libraries were constructed as previously described28. Briefly, 21–30nt RNA was size-selected on a 17.5% polyacrylamide/7M urea gel and ligated to a 3’ adapter. The ligated species were size-selected on a 17.5% polyacrylamide/7M urea gel and ligated to a 5’ adapter. RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA and PCR-amplified in a two-step process. Amplified cDNA was gel-purified and sequenced on an Illumina High-Seq platform. Reads with maximum 1 nt mismatch were aligned to the S. pombe genome using Novoalign (http://www.novocraft.com/products/novoalign/), normalized for reads per million using a Python script, and visualized using IGV (http://www.broad.mit.edu/igv/). Reads mapping to more than one location were randomly assigned.

Code availability.

The Python script for converting Novoalign output to IGV-viewable files is included in Supplementary Information.

Quantitative PCR.

DNA or cDNA was amplified with the Taq polymerase using primers described in SI Table 2 in the presence of SYBR Green. For ChIP-qPCR, reported values are % of input using the ∆CT method. Error bars in all figures indicate mean +/− standard deviation.

Spotting ade6+ silencing assays.

Cells were either grown in 2 ml of rich medium (YEA, yeast extract plus adenine) at 30°C or picked from fresh plates. Cells were washed with water, then resuspended in water to a concentration of 2×104 or 2×105 cells/ml. 5 ul serial dilutions (between 5-fold and 2-fold) were then spotted on YE medium containing low adenine (Low Ade) for 3 to 5 days and photographed.

Random spore analysis and tetrad dissection.

Fresh colonies of each parental strain were mixed in 50 µl water, plated on low-nitrogen medium (ME), and incubated at 30°C for 2–3 days. For random spore analysis, one loopful of crossed cells was resuspended in 1 ml water and checked under a microscope for the presence of tetrads. The cell suspension was then incubated at room temperature overnight with 5 μl glusalase (Perkin Elmer) to kill non-spore cells, then diluted such that ~100–200 cells were spread onto each plate of yeast extract Low Ade medium. For tetrad dissection, cells were struck onto a Low Ade plate, and tetrads were separated using a Singer Instrument MSM System 400. Tetrads were incubated at 32°C for 3–6 hours, and individual spores were separated on the plate. Plates were then incubated at 32°C for 4–5 days and photographed.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1 |. siRNA-induced H3K9me3 at the euchromatic ade6+ locus and flanking region.

a, Summary of pathways and factors involved in mRNA 3’end processing and its coupling to nuclear export. Chp1 and Ago1 are subunits of the RNAi-induced transcriptional silencing complex (RITS). Uap56 and Mlo3 are TREX (transcription-export) complex subunits, and associate with Dss1 to mediate mRNA export. Tho1 is a subunit of the THO/TREX complex, which is responsible for recruiting other subunits of the TREX complex to mRNA. Mex67 is an ortholog of human NXF1, a critical mRNA export receptor, and associates with Nxt1, another mRNA export factor. Puf6 is an mRNA 3’-UTR-binding protein that has been shown to associate with Mlo3. Rhn1 is involved in RNA Pol II transcriptional termination. Nab2 is a poly(A)-binding protein. The Paf1 complex is required for transcriptional elongation and 3’ end processing, and mutations in Paf1 subunits allow siRNA-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of euchromatic genes. Nup132 is a component of the nuclear pore complex (NPC) that has been linked to mRNA export factors. Bdf2 is a histone binding protein that has been shown to inhibit the spreading of centromeric heterochromatin. Epe1 is a jmjC-domain containing putative demethylase that also promotes spreading of heterochromatin. Mst2 is a histone aceyltransferase. See main text for references.

b-c, Around 1000 cen::ade6+ mst2∆ (b) or cen::ade6+ leo1∆ (c) cells were plated on low adenine medium (Low Ade). Most cells formed white colonies, indicating expression of endogenous ade6+, while ~2% of mst2∆ (b) and 12% of leo1∆ (c) cells formed red or pink colonies, indicating silencing of endogenous ade6+ (white arrow). Upon replating, the resulting red colonies formed mostly red colonies, indicating efficient maintenance of the silent state. Repeated once with similar results for each.

d-e, ChIP-qPCR assays showing mean +/− SD H3K9me2 levels at the vtc4+ locus, which is located next to the ade6+ gene, in the indicated mutant cells based on 2 (d) or 3 (e) independent clones. p values are based on a 2-tailed Student’s t-test comparing the indicated mutants to wild-type cells.

f-h, ChIP-qPCR assays showing mean +/− SD Pol II occupancy at the ade6+ (purple) or vtc4+ (blue) locus in mlo3∆ or leo1∆ clones that have not been selected for silencing (99.5% and 88% white, respectively); p values are based on a 2-tailed Student’s t-test comparing the indicated mutants to wildtype cells (f-g). In (h), either an ade6+-ON (W) or ade6+-OFF (R) colony from each of two clones was picked for analysis. p values based on a 2-tailed Student’s t-test comparing the indicated red to white cells for each clone. 3 biological replicates were used per sample.

Extended Data Figure 2 |. The acquired ade6+ silent allele is stable in the absence of the cen::ade6+ siRNA trigger and the mlo3∆ enabling mutation.

a, ade6+-OFF progeny of the cross in Fig. 2b with the indicated genotypes were plated on Low Ade medium. See Fig 2c for related results.

b-e, Biological replicates of the crosses shown in Fig. 2d-g. cen::ade6+ mlo3∆ ade6+-OFF cells were crossed to cen+ mlo3+ ade6BC+-ON cells with deletions of key RNAi components (b-d) or H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4 (e) followed by RSA. All ade6+-OFF progeny were RNAi+ and clr4+. Bars indicate number of ade6+-OFF meiotic progeny for each genotype.

Extended Data Figure 3 |. The siRNA driver locus is critical for establishing a heritable silent epiallele.

a, cen::ade6+ leo1∆ (left) or ade6+ hairpin (HP) leo1∆ (right) cells were plated on low adenine medium. ~12% of cen::ade6+ leo1∆ (left) and 100% of ade6+ HP leo1∆ (right) cells formed red or pink colonies, indicating silencing of endogenous ade6+. Repeated twice.

b-c, cen::ade6+ ade6+-OFF leo1∆ cells (b) or ade6+ HP ade6+-OFF leo1∆ (c) cells were crossed to cen+ ade6BC+-ON cells followed by random spore analysis (RSA). Number of progeny matching each indicated genotype and phenotype is shown. 80 red and 80 white colonies were genotyped by PCR. Results reflect two independent crosses.

d, siRNA-sequencing showing limited secondary siRNA generation in ade6+ HP leo1∆ ade6+-OFF cells, compared with more extensive secondary siRNA spreading to neighboring genes bub1+ and vtc4+ in cen::ade6+ leo1∆ ade6+-OFF cells. Shaded areas represent sequence identity to ade6+ HP (top 3 rows) or cen::ade6+ (bottom 3 rows). Two independent clones shown for each experimental sample.

e-f, H3K9me2 (e) and H3K9me3 (f) ChIP-seq reads mapping to the endogenous ade6+ locus in cells with the indicated genotypes and expression states. Shaded areas represent sequence identity to ade6+ HP (top 3 rows) or cen::ade6+ (bottom 3 rows). Two independent clones shown for each experimental sample.

g-h, ChIP-qPCR assays showing differences in H3K9me2 (g) or H3K9me3 (h) levels in cen::ade6+ leo1∆ ade6+-OFF and ade6+ HP leo1∆ ade6+-OFF cells at ade6+ (purple) and vtc4+ (blue). Bars reflect mean +/− SD from 3 biological replicates. p values are based on 2-tailed Student’s t-test comparing leo1∆ cells to appropriate wild-type cells. On the right, control ChIP-qPCR at dg repeats.

Extended Data Figure 4 |. cis inheritance of the acquired ade6+ silencing and its stable propagation over multiple meiotic generations.

a, ade6BC-OFF cells crossed to ade6+-ON cells, followed by tetrad dissection on Low Ade medium (top) and genotyping using allele-specific PCRs (bottom), showed the 2:2 segregation of the OFF and ON states and cis transmission of each state. Performed once, but see Fig. 3a for reciprocal cross. b, ade6+-OFF progeny of repeated ade6+-OFF x ade6BC+-ON crosses were selected and crossed again, showing stability of the ade6+-OFF allele over five meiotic generations. n, number of meiotic progeny analyzed. Independent replicate of cross in Fig. 3c.

Extended Data Figure 5 |. Induction of H3K9me and siRNAs at the endogenous ade6+ locus.

a, H3K9me2 ChIP-seq reads mapping to the endogenous ade6+ locus in cells with the indicated genotypes and expression states. Shaded area indicates the region of sequence identify with cen::ade6+. b-c, H3K9me2 (b) and H3K9me3 (c) ChIP-seq reads mapping to the dg and dh repeats of centromere 1 (dg1 and dh1, respectively) in cells with the indicated genotypes and phenotypes. d, Zoomed in view of sRNA-seq reads at the endogenous ade6+ locus shown in Fig. 3e. Shaded area indicates cen::ade6+ homology. 2–3 independent clones were sequenced each for ON and OFF meiotic progeny.

Extended Data Figure 6 |. vtc4+ and rpl3402+ are critical for inheritance of silencing at the endogenous ade6+ locus.

a, Schematic of the siRNA driver cen::ade6+ locus on chromosome 1 (upper) and the endogenous ade6+ locus (lower) in which the vt4+ and rpl3402+ genes were replaced with the ura4+ gene ( vtc4-rpl3402∆::ura4+). b, Frequency of silencing establishment at endogenous ade6+ in cen::ade6+ leo1∆ vtc4-rpl3402∆ cells. Repeated twice. c, cen::ade6+ leo1∆ vtc4-rpl3402∆ ade6+-OFF cells were crossed to cen+ leo1+ ade6BC+-ON cells followed by random spore analysis (RSA) to test the epigenetic maintenance of the OFF state in the absence of the cen::ade6+ siRNA driver and the leo1∆ enabling mutation. The number of progeny matching each genotype and phenotype are shown. 80 white and 80 red progeny were genotyped. Results reflect two independent crosses.

Extended Data Figure 7 |. Heritable silencing of a KanR-ade6+ transgene inserted at 4 different genomic loci.

a-d, Schematic diagrams of kan-ade6+ insertions at the mal1+ (a), efm3+ (b), meu10+ (c), and mrp1+ (d) loci. e-h, KanR-ade6+-OFF cells of the indicated genotypes were crossed to cen1+ ade6-M210 cells followed by random spore analysis. The number of progeny matching each genotype and phenotype are shown. Total red or white colonies genotyped are indicated for each cross. For red cells, the first number indicates kanamycin-resistant colonies (indicating presence of the KanR-ade6+-OFF transgene) and second number indicates total red colonies (the remainder of which possess the endogenous ade6-M210 mutant allele). i, cen+ KanR-ade6+ mlo3+ leo+ progeny of the crosses in (e)-(h) were plated on media containing low adenine to test for stability of each epiallele during mitotic growth. Performed once. j, ChIP-qPCR assay showing enrichment of H3K9me3 at KanR-ade6+ epialleles in the cen+ mlo3+ leo1+ progeny of the crosses in (e)-(h). Sample mean +/− SD from 3 biological replicates. k-l, efm3::KanR-ade6+-OFF (k) or meu10::KanR-ade6+-OFF (l) cells were crossed to ade6-M216 ago1∆ (left) or clr4∆ (right), followed by RSA. All ade6+-OFF progeny were ago1+ and clr4+. Bars indicate the number of ade6+-OFF meiotic progeny for each genotype. Total red or white colonies genotyped are indicated for each cross. For red cells, the first number indicates kanamycin-resistant colonies (reflecting the presence of the KanR-ade6+-OFF transgene) and the second number indicates the total red colonies (the remainder of which possess only the ade6-M210 allele).

Extended Data Figure 8 |. Heritable silencing of KanR-ade6+ transgenes correlates with local secondary siRNA generation.

a-c, Zoomed in (upper) or zoomed out (lower) sRNA-seq reads mapping to the indicated KanR-ade6+ transgenes in cen+ mlo3+ leo1+ meiotic progeny of the crosses in Extended Data Fig. 7e-g. In (c), two different red clones are shown, corresponding to clone #1 (upper) and clone #2 (lower) in Extended Data Fig. 7i. In these clones, the magnitude of locally hopped siRNAs (not mapping to KanR-ade6+) correlates with the magnitude and efficiency of inherited silencing. d, Zoomed in view of sRNA-seq reads mapping to the endogenous ade6+ locus. Sequencing was performed once, but for ade6+-OFF meu10::kanMX, which represented a strong silent epiallele, small RNAs from 2 independent clones (#1 and #2) were analyzed.

Extended Data Figure 9 |. Erasure of the silent state during diploid formation and meiosis requires interallelic pairing.

a, Biological replicate of the cross shown in Fig. 4a. cen::ade6+ mlo3∆ ade6+-OFF cells were crossed to cen+ ago1∆ epe1∆ ade6+-ON cells, followed by random spore analysis. Number and phenotype of mlo3+ progeny with the indicated genotypes and phenotypes (red = OFF, white = ON) are shown. mlo3∆ progeny were excluded. n, number of meiotic progeny analyzed. b, Mating of a ura4∆::10XtetO-ade6+ epe1∆ OFF allele with an identical OFF allele, followed by diploid formation and sporulation (meiosis) produces progeny in which the OFF state is maintained at a high frequency (47%). Repeated twice. c, Mating of the ura4∆::10XtetO-ade6+ epe1∆ OFF allele with a genetically identical ON allele results in erasure of the OFF state in nearly all of the resulting meiotic progeny. Repeated twice. d, Partial disruption of pairing by replacement of ura4∆::10XtetO-ade6+ with ura4+ partially restores the epigenetic maintenance of the OFF state. Repeated once.

Extended Data Figure 10 |. Strategy for siRNA-induced silencing at the ura4Δ::ade6+ locus.

a. The ura4+ coding sequence was replaced with ade6+ to generate a ura4Δ::ade6+ allele in cen::ade6+ leo1Δ ade6-M210 cells. Formation of red colonies on low adenine medium indicated ura4Δ::ade6+ silencing. b, cen::ade6+ leo1Δ ura4Δ::ade6+-OFF cells were crossed to cen+ ura4Δ::ade6+-ON cells to demonstrate that the resulting ura4Δ::ade6+-OFF state is stable in the absence of the cen::ade6+ siRNA trigger or the leo1Δ enabling mutation. c, d. Crosses showing that the ura4Δ::ade6+-OFF epigenetic state depends on Ago1 (c) and Clr4 (d). e, Cross for generating an epe1Δ ura4Δ::ade6+-OFF epiallele (top) and comparison of RNAi-independent (TetR-Clr4-I-induced) and RNAi-dependent (cen::ade6+-induced) ade6+-OFF epialleles. Same results were obtained with independent clones.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Moazed lab for helpful discussions, and Keith Connolly, Nahid Iglesias, Gloria Jih, and Gergana Shipkovenska for comments on the manuscript. R.Y. was partially supported by an NIH training grant (T32, GM96911). This work was supported by a grant from the NIH to D.M. (GM072805). D.M. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data availability. Genome-wide data sets are deposited at GEO under the accession number GSE111859.

References

- 1.Margueron R & Reinberg D Chromatin structure and the inheritance of epigenetic information. Nat Rev Genet 11, 285–296, doi:nrg2752 [pii] 10.1038/nrg2752 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moazed D Mechanisms for the inheritance of chromatin states. Cell 146, 510–518, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.013 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ragunathan K, Jih G & Moazed D Epigenetics. Epigenetic inheritance uncoupled from sequence-specific recruitment. Science 348, 1258699, doi: 10.1126/science.1258699 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Audergon PN et al. Epigenetics. Restricted epigenetic inheritance of H3K9 methylation. Science 348, 132–135, doi: 10.1126/science.1260638 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X & Moazed D DNA sequence-dependent epigenetic inheritance of gene silencing and histone H3K9 methylation. Science 356, 88–91, doi: 10.1126/science.aaj2114 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laprell F, Finkl K & Muller J Propagation of Polycomb-repressed chromatin requires sequence-specific recruitment to DNA. Science, doi: 10.1126/science.aai8266 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman RT & Struhl G Causal role for inheritance of H3K27me3 in maintaining the OFF state of a Drosophila HOX gene. Science, doi: 10.1126/science.aai8236 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verdel A et al. RNAi-mediated targeting of heterochromatin by the RITS complex. Science 303, 672–676, doi: 10.1126/science.1093686,1093686[pii] (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motamedi MR et al. Two RNAi complexes, RITS and RDRC, physically interact and localize to noncoding centromeric RNAs. Cell 119, 789–802, doi:S009286740401102X [pii] 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.034 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volpe TA et al. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science 297, 1833–1837 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sienski G et al. Silencio/CG9754 connects the Piwi-piRNA complex to the cellular heterochromatin machinery. Genes Dev 29, 2258–2271, doi: 10.1101/gad.271908.115 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu Y et al. Panoramix enforces piRNA-dependent cotranscriptional silencing. Science 350, 339–342, doi: 10.1126/science.aab0700 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law JA & Jacobsen SE Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat Rev Genet 11, 204–220, doi: 10.1038/nrg2719 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luteijn MJ & Ketting RF PIWI-interacting RNAs: from generation to transgenerational epigenetics. Nat Rev Genet 14, 523–534, doi: 10.1038/nrg3495 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iida T, Nakayama J & Moazed D siRNA-mediated heterochromatin establishment requires HP1 and is associated with antisense transcription. Mol Cell 31, 178–189, doi:S1097-2765(08)00464-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.003 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu R, Jih G, Iglesias N & Moazed D Determinants of heterochromatic siRNA biogenesis and function. Mol Cell 53, 262–276, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.11.014 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kowalik KM et al. The Paf1 complex represses small-RNA-mediated epigenetic gene silencing. Nature 520, 248–252, doi: 10.1038/nature14337 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allshire RC, Javerzat JP, Redhead NJ & Cranston G Position effect variegation at fission yeast centromeres. Cell 76, 157–169. (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thakurta AG, Gopal G, Yoon JH, Kozak L & Dhar R Homolog of BRCA2-interacting Dss1p and Uap56p link Mlo3p and Rae1p for mRNA export in fission yeast. EMBO J 24, 2512–2523, doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600713 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jih G et al. Unique roles for histone H3K9me states in RNAi and heritable silencing of transcription. Nature 547, 463–467, doi: 10.1038/nature23267 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grewal SI & Klar AJ Chromosomal inheritance of epigenetic states in fission yeast during mitosis and meiosis. Cell 86, 95–101 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaydos LJ, Wang W & Strome S Gene repression. H3K27me and PRC2 transmit a memory of repression across generations and during development. Science 345, 1515–1518, doi: 10.1126/science.1255023 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trewick SC, McLaughlin PJ & Allshire RC Methylation: lost in hydroxylation? EMBO Rep 6, 315–320, doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400379 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronshaugen M & Levine M Visualization of trans-homolog enhancer-promoter interactions at the Abd-B Hox locus in the Drosophila embryo. Dev Cell 7, 925–932, doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.11.001 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JL et al. Enhancer action in trans is permitted throughout the Drosophila genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 3723–3728, doi: 10.1073/pnas.062447999 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong KH & Struhl K The Cyc8-Tup1 complex inhibits transcription primarily by masking the activation domain of the recruiting protein. Genes Dev 25, 2525–2539, doi: 10.1101/gad.179275.111 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreno S, Klar A & Nurse P Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods in enzymology 194, 795–823 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halic M & Moazed D Dicer-independent primal RNAs trigger RNAi and heterochromatin formation. Cell 140, 504–516, doi:S0092-8674(10)00020-6 [pii] 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.019 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.