Abstract

Evidence indicates that lung cancer development is a complex process that involves interactions between tumor cells, stromal fibroblasts, and immune cells. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells play a significant role in the promotion or inhibition of tumor growth. As an integral component of the tumor microenvironment, tumor-infiltrating B lymphocytes (TIBs) exist in all stages of cancer and play important roles in shaping tumor development. Here, we review recent clinical and preclinical studies that outline the role of TIBs in lung cancer development, assess their prognostic significance, and explore the potential benefit of B cell-based immunotherapy for lung cancer treatment.

Keywords: lung cancer, B cells, tumor-infiltrating B cells, Bregs, immunotherapy

Introduction

Lung cancer is a heterogeneous malignant disease that is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.1 The growth, invasion and metastasis of lung cancer is a complex and dynamic process that involves both intrinsic genetic abnormalities of the tumor tissue and its interactions with immune cells within the local microenvironment.2 Approximately two-thirds of lung tumor-infiltrating immune cells are composed of T and B cells, with the remaining cells being composed of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and a small number of infiltrating dendritic cells and natural killer (NK) cells.3 These tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are involved in the anti-tumor response within the lung tumor niche.4

The multifaceted effects of lung cancer-associated T cells have been intensely studied. It has been noted that CD4+ Th1 cells, activated CD8+ T cells, and γδ-T cells are often involved in type I immune responses and associated with favorable prognosis in lung cancer patients,5,6 whereas Th2, Th17, and Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells are often associated with tumor progression and unfavorable prognosis.7 Further, clinical responses observed from immune checkpoint blockade therapies (inhibiting the immunological targets PD1/PD-L1 or CTLA4)8 and CAR-T cell therapies9 have spurred great interest in the field of anti-tumor immunotherapy. These T cell-targeted therapies have yielded promising clinical results; however, not all patients respond to these therapies, indicating the need for other therapeutic approaches.

B cells infiltrating lung cancer have their own unique roles in anti-tumor immunity. Recent studies have demonstrated that proliferating B cells can be observed in ~35% of lung cancers.10 Furthermore, tumor-infiltrating B lymphocytes (TIBs) can be observed in all stages of human lung cancer development,11 and their presence differs between stage and histological subtypes,12,13 suggesting a critical role for B cells during lung tumor progression. TIBs participate in both humoral and cellular immunity, but their roles in antitumor immunity remain controversial.14 Some studies show the capacity of B cells to induce and maintain beneficial antitumor activity, while others have found that B cells may exert protumor functions due to their various immunosuppressive subtypes. Here, we will review the role of TIBs in lung cancers and discuss their potential clinical applications.

The infiltration, location, and maintenance of TIBs in human lung cancer

The localization of TIBs is highly controlled by the signals or stimuli within the tumor microenvironment. Evidence has shown that B cell infiltration in human lung cancer is significantly higher than that in surrounding tissue or in distant non-tumoral tissue.15 The presence of high endothelial venule (HEV) may be critical for driving B cell homing and infiltration into the tumor niche via ligand/receptor interactions of PNAd/CD62L, adhesion molecules, and integrins.16,17 Importantly, the B cell chemoattractant CXCL13, secreted by tumor cells, follicular dendritic cells, and T follicular helper cells in human lung tumor lesions, was shown to be responsible for the influx of B cells into the tumor.16,18,19 Upon entering the local microenvironment, tumor antigens released from lung cancer cells aid in B cell aggregation and trigger B cell-mediated antigen presentation, which facilitate the maintenance of B cell activation and proliferation.19,20

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and flow cytometric analysis show that all major subsets of B cells can be found within TIB populations (Table 1).21 TIBs, including CD20+ B cells and CD138+ plasma cells, primarily localize to lymphoid aggregates within the lung tumor stroma, the typical model being termed a tertiary lymphoid structure (TLS).10,22 TLSs exhibit features of secondary lymphoid organs with an ongoing immune reaction and exacerbate the local immune responses in chronic inflammatory settings, including tumors.23 It has been verified that TLSs form an efficient and beneficial immune response in most solid tumors.24 Germain et al. described this structure in detail within lung cancer and showed compartmentalized B cell-rich (or follicular area) and T cell-rich zones. B cell-rich areas can be further divided into germinal center (GC) cores and mantle regions.21 Within the GC, TIBs have an increased GC (Bcl6+CD20+/Ki67+CD20+) phenotype,21,22 and B cells proliferate and differentiate into plasma cells. TLS-derived GC-B cells of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients expressed activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), the enzyme critical for immunoglobulin somatic hypermutation (SHM) and class-switch recombination (CSR).21,25 At the mantle, naive B cells (CD20+CD38−CD27−IgD+) can be observed surrounding GCs, with switched-memory B cells (CD20+CD38+/−CD27+IgD−) and non-switched-memory B cells (CD20+CD38+/−CD27+IgD+) found at the interface between the two zones. Plasma cells (CD20−CD38++/CD138+), primarily long-lived plasma cells, accumulate in the follicular periphery, tumor stroma and fibrotic areas, which is sustained by proliferation-inducing ligand+ (PRIL+) myeloid cells in the lung cancer stroma.13,26 These observations suggest that B cells can exist in a continuum of naive cells to differentiated plasma cells within the tumor microenvironment.

Table 1.

Characterization of TIB subsets in human lung cancer

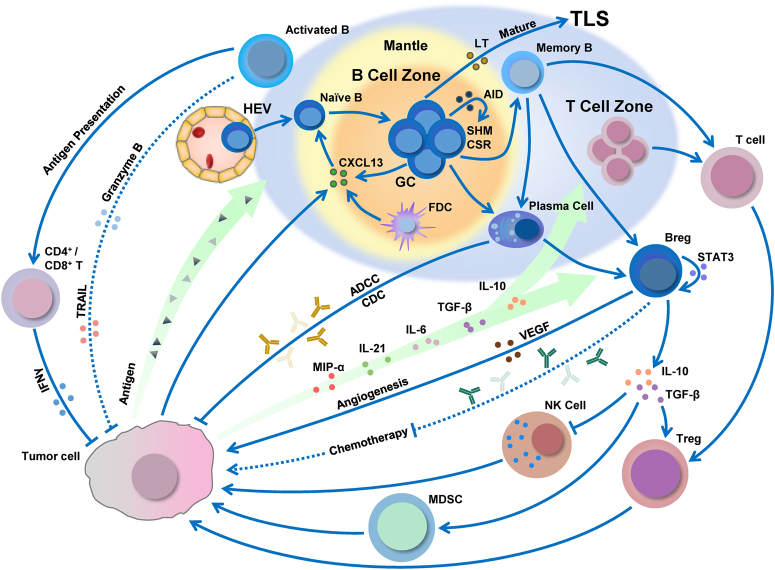

Importantly, TIBs maintain the structure and function of TLS within the lung tumor microenvironment by secreting cytokines and chemokines. Early studies using murine models have identified CXCL13 and lymphotoxin (LT)27,28 as two critical factors in the formation, development, and maturation of isolated lymphoid follicles of the gut.23 Similarly, in human inflamed lungs, such as in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer, B cells produce CXCL13 and LT via toll-like receptor 4 signaling, which positively correlates with the formation and high density of TLS.29,30 Analysis of the factors secreted by TIB, as shown in Fig. 1, provides evidence of ongoing B cell proliferation and induction of antitumor immunity of TLS. Of note, murine models have shown the presence of TLS and follicular B cells in melanoma and/or pulmonary metastasis via LT.31,32 However, some premalignant and malignant tissues in mice are poorly infiltrated by B cells.33,34 The difference in status of TLS-containing follicular B cells in particular experimental settings to some extent may explain why murine models do not recapitulate all clinical-pathological features of human disease.

Fig. 1.

The dynamic conversion processes and immunomodulatory effects of B cells in lung cancer. B cell infiltration, development, and polarization can be regulated by the tumor microenvironment. B cells not only inhibit tumor growth by secreting immunoglobulins, promoting T cell response, and potentially direct killing tumor cells but can also suppress antitumor immune response by Bregs, which produce immunosuppressive cytokines to regulate T cells, NK cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC); secrete pathological antibodies; or promote angiogenesis. The large blue area represents the TLS within the lung tumor. Solid lines and dashed lines depict the proved and potential effects of B cells, respectively. Arrows represent promotion effects, and the blunt ends are suppression effects

Protective effect of TIBs for anti-tumor immunity in lung cancer

The development of humoral immunity is the primary function of B cells. Within the lung, tumor-associated B cells can differentiate into plasma cells and produce tumor-specific antibodies that recognize and react against tumor-associated antigens, such as LAGE-1, TP53, and NY-ESO-1.21 Lung cancer patients with a higher proportion of tumor-associated antigen reactive immunoglobulin tend to have a higher density of follicular B cells.21 Moreover, both follicular B cells and tumor-infiltrating plasma cells are correlated with a better long-term survival of lung cancer patients, indicating the protective role of plasma cells and antibodies in antitumor immunity (see section below for detail).21,35 In accordance with this evidence, increased tumor B cell-derived IgG in the sera is associated with a significantly higher number of tumor regressors in murine xenograft models of human lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) tissue.36 Furthermore, immunoglobulins secreted by lung tumor-stimulated B cells can mediate tumor lysis by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC).37,38

In addition to the production of antibodies, B cells also promote tumoral T cell responses, such as regulation of T cell activation, expansion, and memory formation. Studies have demonstrated that increased levels of CD8+ and CD4+ TILs co-localizing with high CD20+ B cell infiltration are related to long-term survival in NSCLC.6,39 Further, studies by Eerola et al. showed a significant association between B cells and CD8+ TILs in large cell lung carcinoma (LCC).40 These data suggest the beneficial effect of TIBs on T cell-mediated antitumor immunity, possibly through antigen presentation by TIBs. Experimental data from studies in human/murine lung tumor models provide support for B cell interaction with T cells. Tumor-stimulated B cells can rapidly increase the expression of HLA class II and the costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and CD86.41–43 Tumor antigen can be presented by TIBs to tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells, which leads to CD4+ T cell differentiation and clonal expansion.41 Specifically, B cells with the CD69+HLA-DR+CD27+CD21+ phenotype in NSCLC patients correlated with an effector T cell response (IFN-γ+ CD4+ TILs).41 A similar ability of lung TIB cells to induce T cell secretion of IFN-γ has been reported in murine models of lung metastatic tumors.42 Consistently, evidence suggests that an increase in CD4+ and CD8+ TCR repertoire clonality is closely associated with a high density of follicular B cells within the lung tumor niche.44

Although likely not a major mechanism, evidence exists that the activated B cells can directly lyse tumor cells. TIBs have been shown to have cytotoxicity towards hepatoma cells via secretion of granzyme B and TRAIL,45 and human B cells stimulated with IFN-α or a toll-like receptor 9 agonist produce functional TRAIL that is cytotoxic towards melanoma cell lines.46 However, IL-21-induced granzyme B-expressing B cells are detrimental, as they can suppress antitumor T cell responses.47 Figure 1 summarizes the current understanding of the dynamic conversion processes and immunomodulatory effects of B cells in lung cancer. A better understanding of the functional properties of TIBs in lung cancer will help develop improved immunotherapies against lung cancer.

Inhibitory effect of Bregs on antitumor immunity in lung cancer

B cells with tumor-promoting effects have been defined as regulatory B cells (Bregs). Multiple subtypes of Bregs have been identified based on the expression of surface markers, production of soluble factors, and properties of promoting tumor growth in both human and animal tumors. Although diversity of phenotypic markers across different tumors has been reported,48 the canonical phenotypes in both humans and mice are concentrated in memory CD27+ and transitional CD38+ B cells and share phenotypes with plasma cells, such as IgA+CD138+ and IgM+CD147+.49,50 Similarly, in both human and mouse studies, Bregs display their characteristic immunosuppression by secreting cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β and/or upregulating immune regulatory ligands such as PD-L1 and CTLA-4, which attenuate T and NK cell responses and/or facilitate the protumor effects of Tregs, MDSCs, and TAMs.51

As part of a continuum of B cell phenotypes, Bregs likely acquire their regulatory phenotype within the lung tumor microenvironment.52 The polarization of B cells to high IL-10-secreting cells is associated with high expression of inflammatory signals either derived from the tumor directly or indirectly by other microenvironment constituents.53–56 In one model, LPS-stimulated lung cancer cells alone could polarize B cells to a Breg phenotype. Polarization was attributed to high secretion of RANTES, MIP-α, TNF-α, and TGF-β; thus, at least some differentiation factors could be directly attributed to epithelial tumor cells.57 Other signals, such as IL-21 and TGF-β, may be derived from other tumor-infiltrating or resident cells, as IL-21 is not known to be epithelial derived.58

Importantly, IL-10+ Bregs have been associated with tumor progression in experimental models33,48–51,59–63 with some evidence to suggest their inhibitory role in human lung cancer (Fig. 1).52,57 In murine preclinical models, data suggest that B cells may hamper chemotherapy. In an autochthonous transgenic murine model for prostate cancer, the presence of IgA/IL-10/PD-L1+ plasma cells reduced tumor response to oxaliplatin, which could be restored in B cell-deficient mice.59 Similarly, using a K14-HPV-induced squamous carcinoma model, Coussen’s group has shown that cancer development was dependent on B cell-mediated FcγR engagement and that depletion of B cells (by anti-CD20) was complementary to platinum-based and Taxol-based chemotherapy for carcinoma.33,60 Additionally, in murine models of lung metastasis, tumor angiogenesis is primarily dependent on B cell-mediated induction of VEGF, which requires Stat3 signaling in B cells.61 Lung metastasis was shown to require the participation of active Stat3-expressing Bregs that can promote TGF-β-mediated conversion of CD4+ TILs to Tregs, inhibit tumoricidal activity of NK cells, or directly activate MDSC.62,63

Data on the role of Bregs in human studies are more limited, with some indication of the presence of these cells in human lung cancer. For example, a high frequency of CD19+IL-10+ Bregs have been found within lung cancer patients,57 and CD24hiIL-10+ B cells that display a plasma cell-like gene signature are elevated in lung tumors but not found in normal lung tissue.52 Further, an increase in IL-10-producing Bregs is associated with an increased frequency of peripheral Tregs and MDSC in the advanced clinical stage of lung cancer,64 suggesting that together with murine models, IL-10+ Bregs may be detrimental to human disease. Breg activity has been found within Stat-regulated tumors, which together with NF-κB co-regulate numerous oncogenic and inflammatory genes.65 Stat3-driven Bregs are negatively associated with survival in ovarian cancer66 and have been identified in the tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLN) of lung cancer patients.67 These Bregs characterized by a CD19+CD5+ phenotype driven by Stat3 activation and IL-6-induced CD5 over-expression are thought to promote tumor progression by inducing tumor angiogenesis and immunosuppression through production of IL-10.67 Together, the published data suggest that the presence of human Breg phenotypes maybe associated with inflammation; however, it is unclear whether they are bystanders or actively promote cancer.

Thus, the capacity of Bregs for attenuation of immune responses has been clearly demonstrated in multiple experimental models of cancer.53 However, much remains to be understood regarding the biology of Bregs in human lung cancer. For example, the identification of a unique Breg signature, the mechanisms that control Breg differentiation, and a complete understanding of the interactions between Bregs and the tumor microenvironment will provide a clearer role of this population in lung cancer progression.

Predictive value of TIB for the prognosis of human lung cancer

The presence of B cells in human lung tumors has been correlated with patient prognosis, as summarized in Table 2. The number of intratumoral GCs and/or B cells was found to be inversely correlated with lung cancer stage.10 Generally, when identified by CD20 for total B cells, the presence of B cells infiltrating NSCLC tumor is overwhelmingly favorable for long-term overall survival (OS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), or disease-specific survival (DSS) of NSCLC,6,21, 39,40,68–70 with a few exceptions that did not identify any significant associations6,71,72 or negative associations with the disease.13 No significant association between TIBs and prognosis was observed for small cell lung cancer (SCLC).73 Among studies that show favorable TIB presence, no difference in prognostic outcome was observed between patients with early-stage or late-stage tumors,21 suggesting that the presence of B cells can affect outcome at all stages of disease. Further, the presence of common driver mutations such as EGFR, KRAS, and TP53 in lung adenocarcinoma (ADC) was found to have no effect on B cell infiltration or their prognostic values.52,74

Table 2.

Prognostic significance of TIB in human lung cancer

| Markers | Methods | Studied cases | Tumor subtypes | Stages of the disease | Therapy | Location (mean extent) of infiltration | Follow-up (months) | Outcomes | Conclusion | Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B cell antigen | BCL-6 CD21 | IHC | 91 | ADC, SCC, LCC, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, NSCLC-not specified | I to IV | Surgery | Intratumor or tumor margins | 34 | For all, stage, p = 0.02011 | There was a strongly negative correlation between stage and the presence of intratumoral germinal centres. | Gottlin et al.10 |

| CD20 | IHC | 38 | LCC only | I to III | Surgery | Intratumor | 60 | For all, OS, p = 0.05 | A high number of intratumoral B cells had a significantly better survival than those with a low number of intratumoral B cells. | Eerola et al.40 | |

| CD20 | IF | 202 (YTMA79) | ADC, SCC, other NSCLC | I to IV | ND | In the tumor or stromal tissue | 60 | For all, OS, HR = 0.523 (0.323–0.817), p = 0.004 | High CD20 was statistically significantly associated with longer survival of NSCLC. | Schalper et al.6 | |

| CD20 | IHC | 74 | ADC, SCC | I or II | Surgery only | Tumoral stroma, invasive margin, or between tumor nests | 60 | For all, DSS, p = 0.04 OS, HR = 11 (1.4–9), p = 0.02 | Low follicular B density correlated with poor survival of patients with NSCLC in both early-stage and advanced-stage. | Germain et al.21 | |

| 122 | ADC, SCC, other NSCLC | III A or B | Surgery, chemotherapy, Others | Tumoral stroma, invasive margin, or between tumor nests | 60 | for all, DSS, p = 0.06 OS, HR = 2.1 (1.2–3.7), p = 0.01 | |||||

| CD20 | IHC | 218 | ADC, non-ADC | I or III | Surgery, adjuvant treatment, chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy, radiotherapy | ND | 120 | for all, OS, HR = 1.71, p = 0.097 RFS, HR = 1.96, p = 0.004 for ADC, OS, HR = 2.45, p = 0.09 RFS, HR = 2.86, p < 0.01 for ADC non-smokers, OS, HR = 0.22, p = 0.03 RFS, HR = 0.34, p = 0.009 | A low accumulation of CD20+ B cells was identified as an independent worse prognostic factor in patients with NSCLC, particularly in ADC and non-smokers ADC. | Kinoshita et al.39 | |

| CD20 | IHC | 113 | ADC, SCC, LCC, adenosquamous carcinomas | I to IV | Surgery | Peritumoral tissue | 120 | for all, OS, HR = 0.16 (0.06–0.42), p = 0.04 for non-SCC, OS, p < 0.001 | The presence of B cells around the tumor margins was the only independent prognostic factor of NSCLC, and was relative to a significant survival advantage of non-SCC. | Pelletier et al.68 | |

| CD20 | IHC | 335 | ADC, SCC, LCC, bronchioloalveolar carcinorma | I to IIIA | Surgery, postoperative radiotherapy | Intraepithelial tissue | 60 | for all, DSS, p = 0.023 for SCC, DSS, p = 0.03 | Increasing numbers of epithelial CD20+ and stromal CD20+ lymphocytes correlated significantly with an improved DSS, limited to SCC. | Al-Shibli et al.69 | |

| Tumoral stroma | 60 | for all, DSS, p < 0.001 for SCC, DSS, p < 0.001 | |||||||||

|

CD20 CD79 |

IHC | 84 (training cohort) | ADC, SCC, LCC, adenosquamous carcinorma | I or II | Surgery only | Tumoral stroma | 24 | for all, RFS, HR = 1.99 (0.93–4.26), p = 0.05 RFS, HR = 1.47 (0.70–3.30), p = 0.08 | A weak presence of CD20+ B cells was confirmed in tumor microenvironment of the high-risk relapse subgroup of stage I/II NSCLC. | Hernandez-Prieto et al.70 | |

| CD20 | IHC | 111 | ADC only | I to IIIA | Surgery only | Stroma | 85 | for all, DFS, p < 0.001 for stage I, DFS, p < 0.001 | The infiltration of interfollicular B cells in cancer stroma was significantly associated with poorer prognosis when analyzed for all cases of lung ADC or for stage I cases alone. | Kurebayashi et al.13 | |

| CD20 | IF | 350 (YTMA140) | ADC, SCC, other NSCLC | I to IV | ND | In the tumor or stromal tissue | 60 | for all, OS, HR = 0.887 (0.643-1.236), p = 0.447 | Increased CD20 signal was not associated with better survival of NSCLC. | Schalper et al.6 | |

| CD20 | IHC | 371 | ADC, SCC, LCC | I to IIIA | Surgery, radiotherapy | Epithelial tissue | 60 | for all, DSS, p = 0.059 | Both epithelial and stromal CD20 expression was not a prognostic factor for survival in NSCLC. | Hald et al.71 | |

| Stromal tissue | for all, DSS, p = 0.419 | ||||||||||

| CD20 | IHC | 455 | ADC only | I A or B | Surgery only | Tumor | 60 | for all, RFP, p = 0.417 | Both tumoral and stromal CD20+ cells had no significant prognostic value for patients with stage I lung ADC. | Suzuki et al.72 | |

| Stroma | for all, RFP, p = 0.389 | ||||||||||

| CD20 | IHC | 56 | SCLC only | I to IV | Surgery | Intratumor | 60 | for all, OS, p = 0.634 | The number of intratumoral B cells was not significantly associated with survival. | Eerola et al.73 | |

| CD138 | IHC | 355 | ADC, SCC, LCC | I to IV | Surgery, adjuvant treatment | Tumoral stroma | 58.7 | for all, OS, HR = 0.74 (0.56–0.99), p = 0.041 for ADC, OS, HR = 0.54 (0.36–0.82), p = 0.004 | Higher CD138 expression revealed a comparable association with longer survival of NSCLC, particular in the ADC subgroup. | Lohr et al.35 | |

| CD138 | IHC | 371 | ADC, SCC, LCC | I to IIIA | Surgery, radiotherapy | Epithelial tissue | 60 | for all, DSS, p = 0.292 | Both epithelial and stromal CD138 expression was not a prognostic factor for survival in NSCLC. | Hald et al.71 | |

| Stromal tissue | for all, DSS, p = 0.165 | ||||||||||

| CD138 | IHC | 191 | ADC, SCC, LCC | I to IIIA | Surgery, radiotherapy | Epithelial tissue | 192 | for all, DSS, p = 0.847 | Both epithelial and stromal CD138+ cells showed no significant correlation with DSS. | Al-Shibli et al.77 | |

| Stromal tissue | for all, DSS, p = 0.121 | ||||||||||

| p63 CD138 | IHC | 111 | ADC only | I to IIIA | Surgery only | Stroma | 85 | for all, DFS, p < 0.001 for stage I, DFS, p < 0.001 for Papillary/Acinar Grade1/2 subtype, DFS, p = 0.006 for Papillary/Acinar Grade1/2 subtype (stage I) DFS, p = 0.008 | The infiltration of interfollicular/parafollicular plasma cells in cancer stroma was significantly associated with poorer prognosis when analyzed for all cases of lung ADC or for stage I cases alone. The plasma cell infiltration is the independent negative prognostic factor in Grade1/2 papillary/acinar ADC. | Kurebayashi et al.13 | |

| Immunoglobulin κC | IHC | 355 | ADC, SCC, LCC | I to IV | Surgery, adjuvant treatment | Tumoral stroma | 58.7 | for all, OS, HR = 0.72 (0.53–0.98), p = 0.035 for ADC, OS, HR = 0.57 (0.37–0.89), p = 0.013 RFS, p = 0.044 | High immunoglobulin κC protein expression was associated with longer survival of NSCLC, particular in the ADC subgroup. | Lohr et al.35 | |

| Immunoglobulin κC | qRT-PCR Microarray | 196 | ADC, SCC | I to IV | ND | Desmoplastic stroma in-between tumor cell nests | 120 | for all, OS, HR = 0.786 (0.722–0.856), p < 0.001 for ADC, OS, p = 0.002 | Single immunoglobulin κC mRNA expression was significantly associated with longer survival of NSCLC. This prognostic relevance was only restricted to ADC. | Schmidt et al.75 | |

| 1056 (validation dataset) | ND | for all, OS, HR = 0.91 (0.85–0.98), p = 0.011 | |||||||||

| IgG4 | IHC | 294 | ADC, SCC, LCC, sarcomatoid carcinomas, adenosquamous carcinoma | I to IV | Surgery only | Stroma | 60 | for stage I SCC, OS, p = 0.0409 for SCC, OR = 15.4307 (4.5863–71.6024), P < 0.0001 for grade3 ADC, OR = 8.5662 (2.5946–38.8643), P = 0.0013 | In patients with stage I SCC, IgG4-producing plasma cells was significantly associated with a favorable prognosis. | Fujimoto et al.76 | |

| CD19+CD20+CD69+ CD27–CD21– | Flow cytometry | 62 | ADC, SCC and other | pT1a–pT4 | Surgery, adjuvant treatment | ND | ND | ND | The survival of the small cohort of patients that had follow-up data were examined, which limited the assessment of predictive value of this Breg subset. | Bruno et al.41 | |

|

CD19+CD5+ Stat3+ |

IF IHC | 9 | Lung and prostate cancer | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | In lung tumor lymph nodes, p-STAT3 expression and CD5 positivity in CD19+ B cells strictly correlated. However, the limited number of patient specimens failed to support the evidence that CD19+CD5+ B cells was a contributing negative factor for patient survival. | Zhang et al.67 | |

| B-cell signature | 50-gene signature (mainly B/plasma cell immune genes) | Microarray | 162 (validation dataset) | ADC, SCC, LCC, Adenosquamous | I or II | Surgery only | Tumoral stroma | 24 | for all, RFS, HR = 3.44 (1.6–7.3), p = 0.001 | The predictor 50-gene was over-expressed in the low- compared to the high-risk relapse group of stage I/II NSCLC. | Hernandez-Prieto et al.70 |

| 60-gene signature (primarily humoral immunity related genes) | qRT-PCR Microarray | 196 | ADC, SCC | I to IV | ND | Desmoplastic stroma in-between tumor cell nests | 120 | for all, OS, HR = 0.786 (0.722–0.856), p < 0.001 for ADC, OS, p = 0.002 | The 60-gene signature was significantly associated with longer survival of NSCLC. This prognostic relevance was only restricted to ADC. | Schmidt et al.75 | |

| 60-gene signature (primarily humoral immunity related genes) | mRNA-seq | 504 | ADC, SCC | I to IV | ND | ND | ND | for ADC, OS, HR = 0.71 (0.58–0.87), p = 7.80E−04 | High expression of 60-gene signature predicted improved overall survival of ADC. | Iglesia et al.83 | |

| 24-gene signature (mainly B cell lineage-related genes) | Microarray | 130 | SCC only | I to III | Surgery, adjuvant treatment | ND | 72 | for stage I–II SCC, OS, p < 0.001 | B cell-related genes dominated the list of 24-gene signature in early stage SCC of the lung. | Mount et al.84 | |

| B cell specific signatures | mRNA-seq or Microarray | 933 | ADC, SCC | I to IV | ND | ND | ND | for ADC, OS, HR = 0.870 (0.719–1.053), p = 0.154 for bronchioid, OS, HR = 0.908 (0.616–1.337), p = 0.625 for magnoid, OS, HR = 0.930 (0.669–1.293), p = 0.666 for squamoid, OS, HR = 0.747 (0.549–1.015), p = 0.062 for SCC, OS, HR = 1.001 (0.831–1.206), p = 0.992 for basal, OS, HR = 1.038 (0.726–1.483), p = 0.840 for classical, OS, HR = 1.155 (0.832–1.603), p = 0.390 for secretory, OS, HR = 0.977 (0.690–1.384), p = 0.896 for primitive, OS, HR = 0.667 (0.330–1.349), p = 0.260 | B cell infiltration was associated with relatively better prognosis of squamoid subtype, but can not predict survival of four SCC subtypes. | Faruki et al.74 | |

| B cell specific signatures | mRNA-seq or Microarray | 1336 | ADC, SCC, LCC, SCLC | I to IV | Surgery only | Intratumor | 185 | for ADC, Naive B, outcome, z-score = −1.43, p > 0.05 Memory B, outcome, z-score = −1.40, p > 0.05 Plasma cell, outcome, z-score = −1.59, p > 0.05 for SCC, Memory B, outcome, z-score = 2.02, p < 0.04 for LCC, Plasma cell, outcome, z-score = 2.71, p < 0.04 | The three subgroups of B cell representation including naive, memory and plasma cells have a strong trend of favorable outcomes of lung ADC, whereas memory B cell and plasma cell signatures denoted adverse outcomes of SCC and LCC, respectively. | Gentles et al.82 | |

HR: hazard ratio, OR: odd ratio, ND: Not Determined.

Although most studies indicate a favorable outcome of TIBs in NSCLC, prognostic impact differs when analyzed with clinical correlates such as histological subtype and location. In studies with mixed tumor subtypes, most studies indicate that the prognostic relevance was restricted to ADC,39,68 with one study showing relevance in only SCC69 or LCC.40 Further, when the location of TIBs was analyzed for all NSCLC subtypes, most studies indicated that a stromal6,21,70 or marginal68 infiltrate, rather than an intraepithelial infiltrate, was associated with favorable prognosis. Interestingly, a favorable outcome for intraepithelial TIBs was only observed in samples that show SCC or LCC as the prognostic subtype,40,69 suggesting that mechanisms of B cell regulation of tumors may differ among lung cancer subtypes. The prognostic difference observed among studies may be due to the interpatient heterogeneity within the study cohorts or biological differences in TIB infiltration among the tumor subtypes. For example, a greater abundance of CD20+ B cell infiltration has been observed in ADC than in SCC or LCC.6,40 Interestingly, SCLC has a greater abundance of infiltrating T cells and TAMs but few TIBs, which may account for the low prognostic value of TIBs in SCLC.73

In addition to the beneficial prognostic value of total B cell infiltration, the role of tumor-infiltrating plasma cells, identified as CD138+ cells, has been explored. Unlike the overwhelming evidence for the prognostic benefit of total B cell infiltration, plasma cell analysis has yielded more conflicting results, with data correlating to favorable prognosis,35,75,76 no prognostic value,71,77 or adverse prognosis.13 Analysis of clinical correlates such as NSCLC subtype or location could not explain the differences observed among different studies, as both ADC or SCC subtypes with stromal infiltrating plasma cells were shown to have favorable outcomes in some reports35,75,76 but not by others when similar subtypes and locations were analyzed.71,77 One ADC study deviates from the others that indicate a favorable role of B cells in prognosis. Kurebayashi et al. show that when analyzed in the presence of other immune cells, high infiltrates of plasma cells may be indicative of poor outcomes, suggesting that the prognostic value of B cells may change in the context of other cells.13 Notably, four studies have performed additional analysis of immunoglobulin isotypes.13,35,75,76 IgG4-producing plasma cells were determined to be a positive prognostic factor in SCC.76 In contrast, subset analysis of an ADC cohort demonstrated that the presence of IgA+ rather than IgG4+ plasma cells trended towards an adverse prognosis; however, statistical significance was not reached.13 This observation is consistent with the known immunosuppressive effects of IgA+ plasma cells on chemotherapy models,59 as well as with IgG-positive cells (IGκC+ cells) as good predictors in ADC.35,75 Overall, given that class-switching and the role of immunoglobulins is considerably affected by different cytokine/chemokine milieus, such as Th2-biased conditions to support regulatory IgG4 or IgA production by plasma cells in the human melanoma microenvironment,78 differences in the presence or effects of each immunoglobulin may exist between each histological subtype of lung cancer.79 Further studies of isotype-specific plasma cells in different subtypes of lung cancer are required to determine this relationship.

Molecular characterization of NSCLC has revolutionized our understanding of lung cancer.80,81 Coupled with immune subset deconvolution algorithms,82 a more complete understanding of the role of immune infiltrates can be determined with the genomic data alone. Among genomic studies, several B cell-associated gene signatures have been found to correlate with lung cancer prognosis. Gene signatures consisting primarily of humoral immunity-related genes have been shown to predict improved OS in lung ADC.70,75,83 In addition, a 24-gene signature, dominated by B cell lineage-related genes, was identified to be predictive of clinical outcome of early-stage SCC.84 Finally, in a pan-cancer analysis of leukocyte gene signatures, analysis of B cell subgroup signatures, including naive, memory B cells and plasma cells, showed that all three B cell signatures have a strong trend of favorable outcomes of lung ADC, whereas memory B cell and plasma cell signatures significantly denoted adverse outcomes of SCC and LCC, respectively.82 Overall, similar to the histological identification of B cells, the genomic presence of B cells, including pan-B cells and B cell subtypes, generally shows different prognosis outcomes among subtypes.

Beyond standard histological classification of tumor subtypes, molecular characterization allows for additional stratification of NSCLC ADC or SCC. Differences among molecular subtypes and B cell signatures have been observed.74 In analyses considering the molecular subtypes of ADC or SCC, immune infiltrates have been associated with survival in NSCLC. For example, B cell signature is higher in the “squamoid” and “bronchioid” molecular subtypes of lung ADC, while the presence of TIBs is associated with relatively better prognosis of only the squamoid subtype.74 The analyses of the representation of the B cell subgroup and molecular subtype of lung cancer can optimize and improve the assessment of the prognostic impact of TIBs in lung cancer.

The lack of a universally accepted method for evaluating antitumor versus protumor B cells makes it difficult to evaluate the role of TIBs in cancer. In general, the presence of CD20+ B cells or IgG+ plasma cells identified by IHC or gene signature analysis indicates their presence to be beneficial. On the other hand, a few histological studies have demonstrated a detrimental role of B cells on prognosis and are possibly limited due to technical restraints. For example, the use of a single antigen, CD20+, would not differentiate between antitumor B cells and Bregs or between activated and exhausted B cells in TIBs.41 A similar problem can be observed in studies analyzing only CD138 expression. CD138+ B cells only represent a part of plasma cells82 and thus may underestimate the presence of anti-tumor antibody-generating cells or potentially overestimate plasma cells that generate non-tumor-recognizing antibodies, leading to the conclusion that CD138+ cells have no prognostic relevance in some studies.71,77 As discussed above, studies have described CD19+CD20+CD69+CD27−CD21− and CD19+CD5+ B cells as the pathogenic populations within lung tumors,41,67 but as Bregs share common markers with anti-tumor B cells, their contribution will be difficult to discern. Future research efforts should focus on investigating biomarkers that might differentiate anti-tumor B cells from Bregs and developing more robust analytical platforms that combine multiple techniques such as multi-chromatic flow cytometry, IHC, and/or gene sequencing studies together with data from clinical outcomes.

TIB-based immunotherapy in lung cancer

Despite advances in surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, lung cancer continues to have a low survival rate.1,85 Given the prognostic benefit of B cells, development of B cell-based immunotherapeutic strategies may be attractive.14 Targeted approaches for enhancing conventional B cells through stimulation with B cell ligands can effectively inhibit tumor growth and lung metastasis, as exhibited in several murine models (Table 3). After activation in vitro, CpG-activated B cells and TDLN-B cells have been shown to display immunoenhancing properties after adoptive transfer.86–88 Therapeutic efficacies of these B cells were associated with increased antitumor responses by antibody-specific recognition, lysis of tumor cells, reduction of the immunosuppressive environment, and/or tumoricidal-cell response via the Fas/FasL pathway. Additionally, B cells that are activated directly in vivo show effective tumor inhibition. For example, CXCR5-expressing B cells, stimulated by CXCL13-coupled CpG-ODN, can trigger the cytolytic effect of CD8+ TILs, leading to abrogation of lung metastases in 4T1.2 tumor-bearing mice.89 Further, natural compounds, such as Reishi polysaccharide fraction, can suppress tumor growth using CD138+ B cells via activating IgM-mediated cytotoxicity, as exhibited in a Lewis lung tumor mouse model.90

Table 3.

B cell-based immunotherapeutic strategies for lung cancer

| Therapeutic method | Phase/condition | Experimental arm(s) | Control arm(s) | Mechanism | Efficiency | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adoptive transfer B cells | B16-F10 pulmonary metastatic C57BL/6J mice model | CpG-activated B cells | Spleen-derived CD19+ B cells only or CpG only or no treatment | Reducing immunosuppressive environment by lowing recruitment of Tregs and MDSCs and decreasing release of IL-10 and TGF-β | Adoptive transfer of CpG-treated B cells facilitates tumor regression and reduces lung metastasis. | Sorrentino et al.86 |

| MCA 205 or D5 pulmonary metastatic C57BL/6 mice model | MCA 205 or D5G6 TDLN-B cellsa | MCA 205 or D5G6 TDLN-Ba + Tb cells or TDLN-T cellsb only or no treatment | Strong humoral responses to tumor, which displays that immunoglobulins specifically recognize and lyse tumor cells in the presence of complement | The activated TDLN-B cellsa mediate significantly greater reduction of tumor lung metastases upon adoptive transfer. | Li et al.87 | |

| 4T1 pulmonary metastatic BALB/c mice model | IL-10−/− 4T1 TDLN-B cellsa | WT 4T1 TDLN-B cellsa or IL-2 only or no treatment | Directing tumoricidal-cell response via the Fas/FasL pathway | Adoptively transferred B cells effectively reduce number of pulmonary metastatic nodules. | Tao et al.88 | |

| IL-10 antibody + WT 4T1 TDLN-B cellsa | WT 4T1 TDLN-B cellsa or WT 4T1 TDLN-B cellsa + IgG1 or IL-10 antibody only or no treatment | |||||

| 4T1.2 pulmonary metastatic BALB/c mice model | CXCL13-coupled CpG-ODN | CpG-control or mock | Rendering B cells stimulatory to induce cytolytic CD8+ T cell responses | In vivo-targeted delivery of CpG-ODN to B cells blocks lung metastasis. | Bodogai et al.89 | |

| In vivo sensitized B cells | Lewis lung carcinoma C57BL/6J mice model | FMS | DFMS or no treatment | Increasing antibody-mediated cytotoxicity involving the production of IgM against tumor-specific glycans by CD138+ B cells | Immunization of FMS stimulates anti-tumor activities of B cells to suppress lung tumor growth. | Liao et al.90 |

| 76-9 rhabdomyosarcoma pulmonary metastatic C57BL/6J mice model | B cell-deficient mice or B cell-deficient mice + CY or B cell-deficient mice + CY + IL-15 | C57BL/6J mice with NK cell impaired, both T and B cell-deficient, T cell-deficient, mutants deficient in αβ-T cells, γδ-T cells, both αβ-and γδ-T cells or these mice + CY or these mice + CY + IL-15 | Antagonizing NK and T cell-mediated effects | B cell-deficient mice with 76-9 tumor lung metastases show a significant improvement in the survival rate. | Chapoval et al.91 | |

| B cell depletion | TC1 and LKR C57BL/6J mice model | Anti-CD20 antibody (18B12) | Ad.E7 or combination 18B12 with Ad.E7 or no treatment | Increasing the number and activity of systemic and local tumor CD8+ T cells | B cell depletion using anti-CD20 retards lung tumor growth. B cell depletion in conjunction with an adenovirus vaccine markedly augments anti-tumor efficacy, resulting in lung tumor regression | Kim et al.92 |

| 4T1.2 pulmonary metastatic BALB/c mice model | Anti-CD20 antibody (5D2) /Rituximab | IgG control or mock | Enriching for CD20low Bregs, which mediates immunosuppression | Anti-CD20/rituximab enhances tumor progression and lung metastasis. | Bodogai et al.89 | |

| 4T1.2 pulmonary metastatic BALB/c mice model | CXCL13-coupled CpG-ODN | CpG-control or mock | Inactivating Bregs by reversing the expression of CD137L | In vivo-targeted delivery of CpG-ODN to B cells blocks lung metastasis. | Bodogai et al.89 | |

| Breg inactivation | 4T1 pulmonary metastatic BALB/c mice model | Resveratrol | Mock | Abrogating Breg generation and Breg-mediated Treg conversion through the inactivation of Stat3 | Resveratrol-induced inactivation of Bregs is sufficient to inhibit lung metastasis. | Lee-Chang et al.94 |

| 4T1 pulmonary metastatic BALB/c mice model | MK886 | Mock | Inactivating the 5-lipoxygenase/leukotriene/PPARα pathways in Bregs | MK886-triggered inhibition of Btrgs abrogates cancer escape and metastasis. | Wejksza et al.97 |

Experimental models of tumor pulmonary metastasis have been used as substitutes to study the lung cancer immune microenvironment and antitumor immune mechanism by B cells in orthotopic lung cancer86,91

FMS: a l-fucose (Fuc)-enriched Reishi polysaccharide fraction, Ad.E7: adenoviral tumor antigen vaccine

aActivated in vitro with LPS/anti-CD40

bActivated in vitro with anti-CD3/anti-CD28/IL-2

Alternatively, given the role of Bregs, strategies have been devised in experimental models that target depletion/reversal of pathological B cells (Table 3). Early tumor pulmonary metastasis models showed significant improvement in survival by depleting B cells with anti-CD20 antibodies, including rituximab.91,92 Unfortunately, there was no marked clinical benefit in some solid tumors, such as renal cell, colorectal carcinoma, and melanoma.14 Because CD20+ B cells have been shown to correlate with good outcomes in NSCLC,21 depletion of CD20+ B cells could be detrimental to lung cancer treatment.93 Indeed, it was subsequently found that anti-CD20 antibodies may deplete antitumor B cells and possibly enrich for CD20low Bregs, thus exacerbating tumor growth.89 Recently, several chemical modulators have been observed to selectively inhibit Bregs. For example, CpG-ODN significantly reduced CD20low Bregs while activating antitumor B cells, leading to inhibition of lung metastasis in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. Resveratrol efficiently prevented the generation and function of Bregs in a similar animal model.94 Other mediators, such as total glucosides of paeony and Lipoxin A4, also exerted an antitumor effect by inhibiting Bregs.95,96 These molecules attenuated the expansion of Bregs by inactivating Stat3 and/or ERK, leading to a reduction in IL-10 or TGF-β, which further decreases Breg-induced Treg generation.94,96 In addition, the inactivation of the 5-lipoxygenase/leukotriene/PPARα pathways in Bregs, for example, using MK886 is sufficient to abrogate cancer escape and metastasis through the loss of Tregs and the release of effector CD8+ T cells in lung metastasis.97 Overall, B cell-based therapies, except rituximab, are still in preclinical studies, which are classified into three major strategies, including adoptive transfer of stimulated effector B cells, antitumor B cell activation and Breg inhibition in vivo. These B cell-based strategies primarily promote cytotoxic T cells and/or inhibit downstream immunosuppressive pathways, resulting in antitumor immune responses. Future studies will be needed to develop approaches to effectively induce B cells to amplify antitumor responses by other immune cells.

Conclusion and perspective

Our current understanding indicates that tumor-infiltrating B cells are important regulators of lung cancer progression. Driven by signals within the tumor microenvironment, B cells infiltrate, proliferate, and develop in tumors. TIB exert anti-tumor immunity through secretion of tumor-specific antibodies, promoting T cell responses, and maintaining the structure and function of TLS, all of which are associated with beneficial outcomes for lung cancer. However, as multifaceted effectors, B cells can develop into IL-10-secreting immunosuppressive phenotypes, leading to tumor progression. Novel immunotherapeutic strategies targeting B cells will have to both promote antitumor B cells and inhibit Breg phenotypes. Further exploration of B cell function within the lung tumor microenvironment will allow for improved therapeutic strategies to target this important subset of immune cells.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant #81502202), the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (grant #704121), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant #2017M611329), and the Scientific Research Project in the Science and Technology Development Plan of Jilin Province (grant #20150520142JH).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Wei Liu, Phone: +86-431-81875308, Email: davidliuw@hotmail.com.

Li Zhang, Phone: +1-416-581-7521, Email: lzhang@uhnresearch.ca.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remark R, et al. The non-small cell lung cancer immune contexture. A major determinant of tumor characteristics and patient outcome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2015;191:377–390. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1671PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kataki A, et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and macrophages have a potential dual role in lung cancer by supporting both host-defense and tumor progression. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2002;140:320–328. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2002.128317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brambilla E, et al. Prognostic effect of tumor lymphocytic infiltration in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:1223–1230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bremnes RM, et al. The role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in development, progression, and prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016;11:789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schalper KA, et al. Objective measurement and clinical significance of TILs in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:dju435. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall EA, et al. Emerging roles of T helper 17 and regulatory T cells in lung cancer progression and metastasis. Mol. Cancer. 2016;15:67. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16:275–287. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeltsman M, Dozier J, McGee E, Ngai D, Adusumilli PS. CAR T-cell therapy for lung cancer and malignant pleural mesothelioma. Transl. Res. 2017;187:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottlin EB, et al. The association of intratumoral germinal centers with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011;6:1687–1690. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182217bec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieu-Nosjean MC, Goc J, Giraldo NA, Sautès-Fridman C, Fridman WH. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer and beyond. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banat GA, et al. Immune and inflammatory cell composition of human lung cancer stroma. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0139073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurebayashi Y, et al. Comprehensive immune profiling of lung adenocarcinomas reveals four immunosubtypes with plasma cell subtype a negative indicator. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016;4:234–247. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siliņa K, Rulle U, Kalniņa Z, Line A. Manipulation of tumour-infiltrating B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures: a novel anti-cancer treatment avenue? Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014;63:643–662. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1544-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Mar Valenzuela-Membrives M, et al. Progressive changes in composition of lymphocytes in lung tissues from patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:71608–71619. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Chaisemartin L, et al. Characterization of chemokines and adhesion molecules associated with T cell presence in tertiary lymphoid structures in human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6391–6399. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawamata N, et al. Expression of endothelia and lymphocyte adhesion molecules in bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) in adult human lung. Respir. Res. 2009;10:97. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang GZ, et al. The chemokine CXCL13 in lung cancers associated with environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons pollution. eLife. 2015;4:e09419. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campa MJ, et al. Interrogation of individual intratumoral B lymphocytes from lung cancer patients for molecular target discovery. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016;65:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1787-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitzalis C, Jones GW, Bombardieri M, Jones SA. Ectopic lymphoid-like structures in infection, cancer and autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:447–462. doi: 10.1038/nri3700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Germain C, et al. Presence of B cells in tertiary lymphoid structures is associated with a protective immunity in patients with lung cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2014;189:832–844. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1611OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dieu-Nosjean MC, et al. Long-term survival for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with intratumoral lymphoid structures. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:4410–4417. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neyt K, Perros F, GeurtsvanKessel CH, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Tertiary lymphoid organs in infection and autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sautès-Fridman C, et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancers: prognostic value, regulation, and manipulation for therapeutic intervention. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:407. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Longerich S, Basu U, Alt F, Storb U. AID in somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2006;18:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohr E, et al. Dendritic cells and monocyte/macrophages that create the IL-6/APRIL-rich lymph node microenvironments where plasmablasts mature. J. Immunol. 2009;182:2113–2123. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald KG, McDonough JS, Newberry RD. Adaptive immune responses are dispensable for isolated lymphoid follicle formation: antigen-naive, lymphotoxin-sufficient B lymphocytes drive the formation of mature isolated lymphoid follicles. J. Immunol. 2005;174:5720–5728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchesi F, et al. CXCL13 expression in the gut promotes accumulation of IL-22-producing lymphoid tissue-inducer cells, and formation of isolated lymphoid follicles. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:486–494. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litsiou E, et al. CXCL13 production in B cells via Toll-like receptor/lymphotoxin receptor signaling is involved in lymphoid neogenesis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2013;187:1194–1202. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1543OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sautès-Fridman C, et al. Tumor microenvironment is multifaceted. Cancer Metastas. Rev. 2011;30:13–25. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9279-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schrama D, et al. Targeting of lymphotoxin-alpha to the tumor elicits an efficient immune response associated with induction of peripheral lymphoid-like tissue. Immunity. 2001;14:111–121. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrama D, et al. Immunological tumor destruction in a murine melanoma model by targeted LTalpha independent of secondary lymphoid tissue. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2008;57:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0352-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andreu P, et al. FcRgamma activation regulates inflammation-associated squamous carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Visser KE, Korets LV, Coussens LM. De novo carcinogenesis promoted by chronic inflammation is B lymphocyte dependent. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:411–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lohr M, et al. The prognostic relevance of tumour-infiltrating plasma cells and immunoglobulin kappa C indicates an important role of the humoral immune response in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;333:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizukami M, et al. Effect of IgG produced by tumor-infiltrating B lymphocytes on lung tumor growth. Anticancer. Res. 2006;26:1827–1831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foy KC, et al. Peptide vaccines and peptidomimetics of EGFR (HER-1) ligand binding domain inhibit cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. J. Immunol. 2013;191:217–227. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizukami M, et al. Anti-tumor effect of antibody against a SEREX-defined antigen (UOEH-LC-1) on lung cancer xenotransplanted into severe combined immunodeficiency mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8351–8357. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kinoshita T, et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes differs depending on histological type and smoking habit in completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2016;27:2117–2123. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eerola AK, Soini Y, Pääkkö P. Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in relation to tumour angiogenesis, apoptosis and prognosis in patients with large cell lung carcinoma. Lung. Cancer. 1999;26:73–83. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(99)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruno TC, et al. Antigen-presenting intratumoral B cells affect CD4+TIL phenotypes in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017;5:898–907. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones HP, Wang YC, Aldridge B, Weiss JM. Lung and splenic B cells facilitate diverse effects on in vitro measures of anti-tumor immune responses. Cancer Immun. 2008;8:4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yasuda M, et al. Tumor-infiltrating B lymphocytes as a potential source of identifying tumor antigen in human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1751–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu W, et al. A high density of tertiary lymphoid structure B cells in lung tumors is associated with increased CD4+T cell receptor repertoire clonality. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1051922. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1051922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi JY, et al. Margin-infiltrating CD20(+) B cells display an atypical memory phenotype and correlate with favorable prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:5994–6005. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kemp TJ, Moore JM, Griffith TS. Human B cells express functional TRAIL/Apo-2 ligand after CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotide stimulation. J. Immunol. 2004;173:892–899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindner S, et al. Interleukin 21-induced granzyme B-expressing B cells infiltrate tumors and regulate T cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2468–2479. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balkwill F, Montfort A, Capasso M. B regulatory cells in cancer. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fremd C, Schuetz F, Sohn C, Beckhove P, Domschke C. B cell-regulated immune responses in tumor models and cancer patients. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e25443. doi: 10.4161/onci.25443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartz M, Zhang Y, Rosenblatt JD. B cell regulation of the anti-tumor response and role in carcinogenesis. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2016;4:40. doi: 10.1186/s40425-016-0145-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y, Gallastegui N, Rosenblatt JD. Regulatory B cells in anti-tumor immunity. Int. Immunol. 2015;27:521–530. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxv034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lizotte PH, et al. Multiparametric profiling of non-small-cell lung cancers reveals distinct immunophenotypes. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89014. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarvaria A, Madrigal JA, Saudemont A. B cell regulation in cancer and anti-tumor immunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2017;14:662–674. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mauri C, Bosma A. Immune regulatory function of B cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:221–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mion F, Tonon S, Valeri V, Pucillo CE. Message in a bottle from the tumor microenvironment: tumor-educated DCs instruct B cells to participate in immunosuppression. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2017;14:730–732. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cho KA, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate B-cell-mediated immune responses and increase IL-10-expressing regulatory B cells in an EBI3-dependent manner. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2017;14:895–908. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2016.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou J, et al. Enhanced frequency and potential mechanism of B regulatory cells in patients with lung cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2014;12:304. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0304-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amrouche K, Jamin C. Influence of drug molecules on regulatory B cells. Clin. Immunol. 2017;184:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shalapour S, et al. Immunosuppressive plasma cells impede T-cell-dependent immunogenic chemotherapy. Nature. 2015;521:94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature14395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Affara NI, et al. B cells regulate macrophage phenotype and response to chemotherapy in squamous carcinomas. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:809–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang C, et al. B cells promote tumor progression via STAT3 regulated-angiogenesis. PLoS. One. 2013;8:e64159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olkhanud PB, et al. Tumor-evoked regulatory B cells promote breast cancer metastasis by converting resting CD4+T cells to T-regulatory cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3505–3515. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bodogai M, et al. Immune suppressive and pro-metastatic functions of myeloid-derived suppressive cells rely upon education from tumor-associated B cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3456–3465. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu J, et al. Aberrant frequency of IL-10-producing B cells and its association with Treg and MDSC cells in non small cell lung carcinoma patients. Hum. Immunol. 2016;77:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang C, et al. Prognostic significance of B-cells and pSTAT3 in patients with ovarian cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang C, et al. CD5 binds to interleukin-6 and induces a feed-forward loop with the transcription factor STAT3 in B cells to promote cancer. Immunity. 2016;44:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pelletier MP, Edwardes MD, Michel RP, Halwani F, Morin JE. Prognostic markers in resectable non-small cell lung cancer: a multivariate analysis. Can. J. Surg. 2001;44:180–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al-Shibli KI, et al. Prognostic effect of epithelial and stromal lymphocyte infiltration in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:5220–5227. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hernández-Prieto S, et al. A 50-gene signature is a novel scoring system for tumor-infiltrating immune cells with strong correlation with clinical outcome of stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2015;17:330–338. doi: 10.1007/s12094-014-1235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hald SM, et al. CD4/CD8 co-expression shows independent prognostic impact in resected non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with adjuvant radiotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2013;80:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Suzuki K, et al. Clinical impact of immune microenvironment in stage I lung adenocarcinoma: tumor interleukin-12 receptor β2 (IL-12Rβ2), IL-7R, and stromal FoxP3/CD3 ratio are independent predictors of recurrence. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:490–498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eerola AK, Soini Y, Pääkkö P. A high number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are associated with a small tumor size, low tumor stage, and a favorable prognosis in operated small cell lung carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:1875–1881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Faruki H, et al. Lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma gene expression subtypes demonstrate significant differences in tumor immune landscape. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017;12:943–953. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmidt M, et al. A comprehensive analysis of human gene expression profiles identifies stromal immunoglobulin κ C as a compatible prognostic marker in human solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:2695–2703. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fujimoto M, et al. Stromal plasma cells expressing immunoglobulin G4 subclass in non-small cell lung cancer. Hum. Pathol. 2013;44:1569–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Al-Shibli K, et al. The prognostic value of intraepithelial and stromal CD3-, CD117- and CD138-positive cells in non-small cell lung carcinoma. APMIS. 2010;118:371–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chiaruttini G, et al. B cells and the humoral response in melanoma: the overlooked players of the tumor microenvironment. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1294296. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1294296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Klotz M, et al. Shift in the IgG subclass distribution in patients with lung cancer. Lung. Cancer. 1999;24:25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(99)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Collisson EA, et al. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hammerman PS, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gentles AJ, et al. The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat. Med. 2015;21:938–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Iglesia MD, et al. Genomic analysis of immune cell infiltrates across 11 tumor types. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djw144. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mount DW, et al. Using logistic regression to improve the prognostic value of microarray gene expression data sets: application to early-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the lung and triple negative breast carcinoma. BMC Med. Genom. 2014;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Lung cancer statistics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016;893:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24223-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sorrentino R, et al. B cells contribute to the anti-tumor activity of CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide in a mouse model of metastatic lung carcinoma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2011;183:1369–1379. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1738OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li Q, Teitz-Tennenbaum S, Donald EJ, Li M, Chang AE. In vivo sensitized and in vitro activated B cells mediate tumor regression in cancer adoptive immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 2009;183:3195–3203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tao H, et al. Antitumor effector B cells directly kill tumor cells via the Fas/FasL pathway and are regulated by IL-10. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015;45:999–1009. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bodogai M, et al. Anti-CD20 antibody promotes cancer escape via enrichment of tumor-evoked regulatory B cells expressing low levels of CD20 and CD137L. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2127–2138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liao SF, et al. Immunization of fucose-containing polysaccharides from Reishi mushroom induces antibodies to tumor-associated Globo H-series epitopes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:13809–13814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312457110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chapoval AI, Fuller JA, Kremlev SG, Kamdar SJ, Evans R. Combination chemotherapy and IL-15 administration induce permanent tumor regression in a mouse lung tumor model: NK and T cell-mediated effects antagonized by B cells. J. Immunol. 1998;161:6977–6984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim S, et al. B-cell depletion using an anti-CD20 antibody augments anti-tumor immune responses and immunotherapy in nonhematopoetic murine tumor models. J. Immunother. 2008;31:446–457. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31816d1d6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Joly-Battaglini A, et al. Rituximab efficiently depletes B cells in lung tumors and normal lung tissue. F1000Res. 2016;5:38. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7599.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee-Chang C, et al. Inhibition of breast cancer metastasis by resveratrol-mediated inactivation of tumor-evoked regulatory B cells. J. Immunol. 2013;191:4141–4151. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Song SS, et al. Protective effects of total glucosides of paeony on N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in rats via down-regulation of regulatory B cells. Immunol. Invest. 2015;44:521–535. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2015.1043668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang Z, et al. Lipid mediator lipoxin A4 inhibits tumor growth by targeting IL-10-producing regulatory B (Breg) cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;364:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wejksza K, et al. Cancer-produced metabolites of 5-lipoxygenase induce tumor-evoked regulatory B cells via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α. J. Immunol. 2013;190:2575–2584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]