Abstract

Objective

To review the association between hypertension and frailty in observational studies.

Design

A systematic review of the PubMed, Web of Science and Embase databases was performed. A meta-analysis was performed if at least three studies used the same definition of frailty and a dichotomous definition of hypertension.

Setting, participants and measures

Studies providing information on the association between frailty and hypertension in adult persons, regardless of the study setting, study design or definition of hypertension and frailty were included.

Results

Among the initial 964 articles identified, 27 were included in the review. Four longitudinal studies examined the incidence of frailty according to baseline hypertension status, providing conflicting results. Twenty-three studies assessed the cross-sectional association between frailty and hypertension: 13 of them reported a significantly higher prevalence of frailty in hypertensive participants and 10 found no significant association. The pooled prevalence of hypertension in frail individuals was 72% (95% CI 66% to 79%) and the pooled prevalence of frailty in individuals with hypertension was 14% (95% CI 12% to 17%). Five studies, including a total of 7656 participants, reported estimates for the association between frailty and hypertension (pooled OR 1.33; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.89).

Conclusions

Frailty is common in persons with hypertension. Given the possible influence of frailty on the risk–benefit ratio of treatment for hypertension and its high prevalence, it is important to assess the presence of this condition in persons with hypertension.

Trial registration number

CRD42017058303.

Keywords: frailty, Hypertension

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A greater number of potentially eligible articles were screened and included in the review.

Absence of evident publication bias and low-to-moderate risk of methodological bias increase the reliability of our findings.

Heterogeneity in the definitions of frailty and hypertension across studies.

Cross-sectional design of most studies included in the review which limits the opportunity of generating hypotheses regarding a causal link between the conditions of interest.

Introduction

Frailty is a condition characterised by the accumulation of biological deficits and dysfunctions which occurs with age and impairs the homeostatic balance of organisms.1 Frailty confers extreme vulnerability to stressors and increases the risk of negative health outcomes, including mortality, disability, poor quality of life, hospitalisation and institutionalisation.2 This condition has a high prevalence, ranging from 8% to 16% in community-dwelling older adults.3 4 Frailty has been shown to be correlated with morbidity and mortality in persons suffering from cardiovascular disease, and it was suggested that the recognition of frailty status can help physicians in establishing prognosis, determining procedural risks and guiding treatments.5 In some cases, the assessment of frailty may be critical in guiding the patient towards a certain therapeutic choice.6

Several studies have assessed the association of frailty with hypertension. In older adults, it has been suggested that frailty can explain the paradoxical relationship between lower blood pressure (BP) and increased mortality documented in several studies.7–10 For example, data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey demonstrated an effect modification of hypertension according to frailty level in terms of walking speed11; in fit persons, elevated BP was associated with greater mortality, while in frail participants higher BP was associated with lower mortality risk. The SPRINT trial showed that compared with standard BP control intensive control reduces the incidence of cardiovascular events both in frail and non-frail persons, but this study did not show any effects of intensive BP control on risk of frailty-related outcomes, such as gait speed and mobility limitation.12 13 Notably, the hypertension clinical practice guidelines released in 2017 precisely point out that BP-lowering therapy is one of the few interventions shown to reduce mortality risk in frail older individuals.14

Assessing the association of frailty and hypertension may be the first step for understanding their complex interplay and might ultimately lead to optimise the treatment of hypertension and to set therapeutic goals in persons with frailty. However, the evidence on the association between these conditions has never been comprehensively summarised. The aim of the present study is to systematically review the literature and provide pooled estimations of evidence regarding the association of frailty and hypertension.

Methods

We reviewed studies providing information on the association between frailty and hypertension in adult persons (ie, 18 years or older), regardless of the study setting, study design or definition of hypertension and frailty. The protocol of the present study was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (registration number CRD42017058303). This systematic review was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations.

Data sources and searching

We searched three databases for relevant articles published from 1 January 2002 to 26 October 2017: (1) PubMed electronic database of the National Library of Medicine, (2) Web of Science and (3) Embase. The detailed search queries are reported in the online supplementary appendix. References from the selected papers and from other relevant articles were screened for potential additional studies.

bmjopen-2018-024406supp001.pdf (450.1KB, pdf)

Study selection and data extraction

Two assessors independently screened the title and abstract of the selected studies. The inclusion criteria were (1) articles reporting information on the association of frailty with hypertension or BP values; (2) articles in English or another European language; and (3) study design: cross-sectional, case–control or cohort studies. Articles were excluded if they (1) did not investigate the aims of the review; (2) included persons younger than 18 years; (3) did not report original data (eg, editorial, review or congress abstract); (4) did not provide an explicit definition of frailty; (5) if frailty was assessed only with a single symptom/measure (eg, only gait speed or grip strength) and (6) were not in English or another European language. The full text of the articles selected by one or both of the assessors was retrieved for full evaluation. Two assessors read the full texts and independently extracted the information from the selected studies. A third assessor reviewed the data extraction, and any disagreement was resolved through consensus. Articles that were written in another European language than English were sent for translation by a native speaker who conducted the data extraction.

Assessment of risk of bias

Quality of the studies was evaluated independently by the two assessors with the qualitative evaluation of observational studies Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS). Any disagreement in quality assessment was resolved through consensus. Studies scoring >7 were considered at low risk of bias, scores of 5–7 indicated moderate risk of bias and scores of <5 indicated high risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

For each measure of interest (ie, proportions and association estimates), a meta-analysis was performed if at least three studies used the same definition of frailty and a dichotomous definition of hypertension (rather than using continuous BP values). Considering the observational design of the retrieved studies, and the methodological differences potentially responsible for a significant share of the variance within the measures of interest, the pooled estimates were obtained through random-effect models and Mantel-Haenszel weighting. Lack of homogeneity within the pooled studies was tested through the I2 statistics (significant if ≥50%). Additional analyses were performed selecting (1) studies with NOS ≥5 in order to exclude studies with high risk of methodological bias and (2) studies with a sample size ≥500 participants. Publication bias was assessed by mean of the Egger’s and the Begg’s tests. All statistical analyses were performed using the metan and metaprop packages included in STATA V.14.0. Metan was used to provide pooled estimations of the association between frailty and hypertension, Metaprop was used to provide pooled measures of prevalence of frailty and hypertension.15 16 A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in this study.

Results

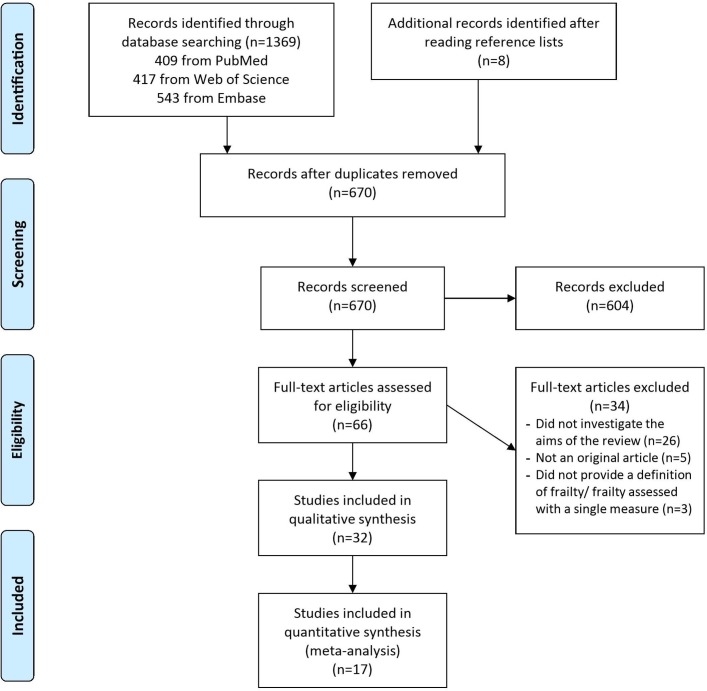

Through the literature search, we retrieved 1369 articles (figure 1). An additional eight articles were identified after reading references from the selected papers. Out of 1369 articles, 670 (48.9%) were screened after duplicates removal. Of these, 604 were excluded after screening and 34 after full-text reading. Thirty-two articles were part of the final qualitative and/or quantitative assessment17–48 (see table e1 in the online supplementary appendix).

Figure 1.

Systematic review and meta-analysis flow chart.

Study description

The studies’ sample size ranged from 56 to 144 403 participants, with a mean age ranging from 60 to 81 years. Only four studies had a longitudinal design.17–20 Most studies included community-dwelling participants, and only three studies included in-hospital participants.43 47 48 Most of the studies were carried out in Asia (n=10), Europe (n=9) and South America (n=9), and fewer in North America (n=4).

Frailty and hypertension definitions

Most of the studies (n=23) defined frailty according to the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) criteria.17–19 21 22 24 25 27–30 34 36–39 41–47 The rest of the studies evaluated frailty based on a frailty index (n=6),20 23 26 32 38 40 by a composite score (n=3)31 33 35 or using the Clinical Frailty Scale (n=1).48 One study assessed frailty adopting both CHS criteria and Frailty Index (FI).38

In the longitudinal studies, frailty incidence ranged from 3% to 16%, in cross-sectional studies, and frailty prevalence ranged from 3% to 68%. A diagnosis of hypertension was reported in 28 studies,17–23 25–38 41–47 while three studies analysed BP as a continuous variable24 38 48 and one classified BP in four groups.40 Diagnosis of hypertension was based on a BP cut-point in 12 studies,17 18 22 28 29 31–34 36 39 41 assessed only by self-reported in 5 studies,21 25 43 45 46 based on evaluation of medical records in 1 study35 and on pharmacological treatment in 1 study.21 In nine studies, hypertension diagnosis was not defined.19 20 26 27 30 37 42 44 47 Prevalence of hypertension ranged from 28% to 100%.

Assessment of risk of bias

The majority of the studies presented a moderate risk of bias (n=25), and six studies presented a high risk, according to the NOS. In most of the cases, the self-reported nature of information was responsible for a lower score. However, according to the Egger’s and the Begg’s tests, no strong evidence of publication bias was detected in our meta-analyses (p=0.150 and 0.987, respectively).

Association between hypertension and frailty

Longitudinal studies

Four longitudinal studies examined the risk of incidence of frailty according to baseline hypertension status. Two studies found that baseline hypertension did not significantly predict incidence of frailty,17 20 but Boullion et al found that hypertension was associated with an increased incidence of the combined outcome prefrailty/frailty (p=0.009).18 However, data from this study were not adjusted for possible confounders. Similarly, Castrejon Perez et al 19 found that hypertension was associated with incident frailty at univariate analysis (HR 2.11, 95% CI 1.03 to 4.31), but this association was not confirmed in the multivariate analysis (HR 1.58, 95% CI 0.83 to 3.01).

Cross-sectional studies

Twenty-three studies assessed the cross-sectional association between frailty and hypertension.21 22 25–37 39 41–47 Results were very different across studies, with 13 studies reporting a significantly higher prevalence of frailty in hypertensive participants(22,26–28,31,32,33,34,36,37,39,44,45 and 10 finding no significant association.21 25 29 30 35 41–43 46 47

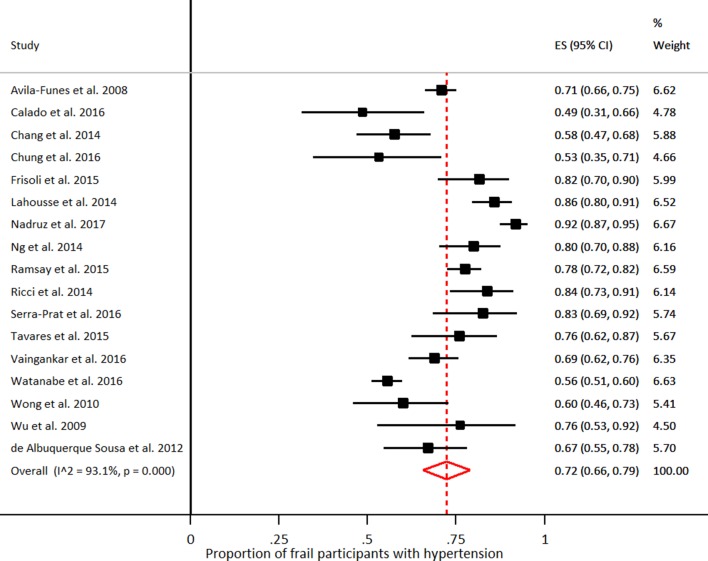

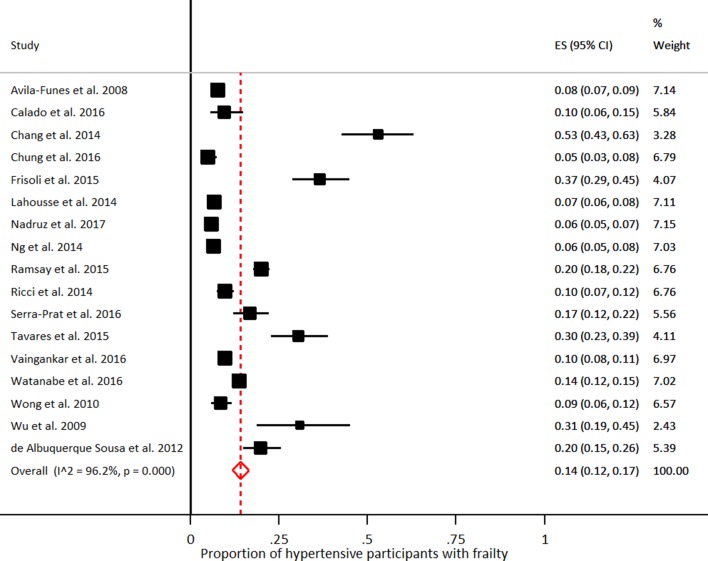

Seventeen of these studies assessed frailty by the use of CHS criteria, for a total sample of 23 304 individuals.21 22 25 27 28 30 34 36 37 39 41–47 Analysing data from these studies, the pooled prevalence of hypertension in frail individuals was 72% (95% CI 66% to 79%; I2=93.1%; figure 2) and the pooled prevalence of frailty in individuals with hypertension was 14% (95% CI 12% to 17%; I2=96.2%; figure 3). When the analyses were limited to 13 studies enrolling participants with a mean age ≥70 years,21 22 25 27 30 34 36 39 41 42 45–47 the pooled prevalence of hypertension in frail individuals was 71% (95% CI 62% to 80%; I2=95.4%) and the pooled prevalence of frailty in individuals with hypertension was 14% (95% CI 11% to 17%; I2=97.0%).

Figure 2.

Proportion of participants presenting with hypertension among those with frailty. Frailty was defined according to the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria.

Figure 3.

Proportion of participants presenting with frailty among those with hypertension. Frailty was defined according to the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria.

Three studies assessed BP as a continuous variable, finding conflicting results: one study showed significantly higher systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) values in frail participants,24 while in two other studies frailty was associated with significantly lower BP values.38 48 A small study including only participants receiving pharmacological treatment for hypertension showed an inverse association between BP levels and frailty.23 Finally, a large study performed in >140 000 community-dwelling older adults aged ≥80 years classified SBP in five groups, showing that frailty was associated with lower SBP.40

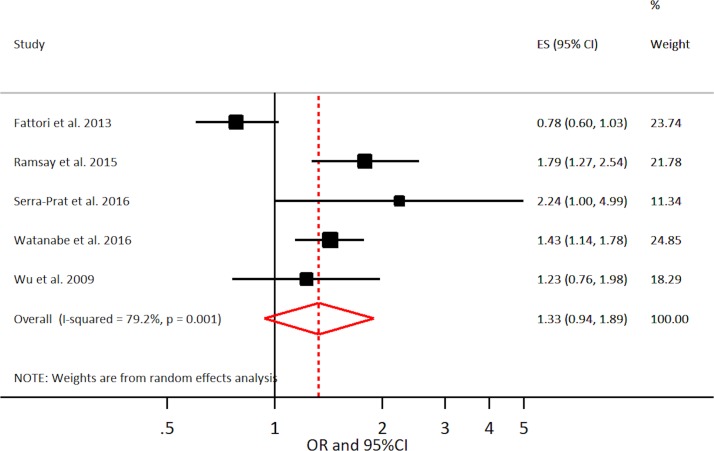

Among studies adopting the CHS definition of frailty and a dichotomous definition of hypertension, five reported estimates (ORs) for the association between frailty and hypertension, for a total sample of 7656 individuals.29 39 42 45 47 All five studies enrolled a sample with a mean age ≥70 years. The pooled estimate for the association of frailty and hypertension based on these studies was 1.33 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.89; I2=79.2%; figure 4). These results were confirmed when only studies with NOS ≥5 (OR 1.39; 95% CI 0.70 to 2.75; I2=88.1%) or studies with a sample size ≥500 participants (OR 1.25; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.99; I2=88.4%) were analysed.

Figure 4.

Cross-sectional association of frailty with hypertension. Frailty was defined according to the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis shows that 7 out of 10 frail adults have hypertension, while about 1 out of 7 hypertensive adults present with frailty. In addition, this study shows that the association between frailty and hypertension is uncertain: few longitudinal studies have assessed the impact of hypertension on incident frailty, providing conflicting results. Further, no studies have been performed to examine whether frailty predicts incident hypertension. Finally, the meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies failed to find a significant association between these conditions.

Frailty has become a high-priority theme in cardiovascular medicine due to the ageing and the increasingly complex nature of patients suffering from cardiovascular conditions.5 6 This is confirmed by the observation that 14% of persons with hypertension are frail. Frailty might indeed influence the therapeutic choices for many cardiovascular diseases. For example, assessment of frailty is considered important for determining which patients are likely to benefit from the treatment of aortic stenosis or left ventricular assist device therapy, in terms of both survival and improved quality of life.49 50

Similarly, therapeutic choices in hypertension might be influenced by presence of frailty. First, frail older people are almost always excluded from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of treatments of cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension. Logistic barriers limiting the retention in the study, the higher propensity to present adverse effects from the treatments and the higher drop out for mortality of frail individuals are the main causes for exclusion from RCTs.51 This limits the generalisability of RCTs' findings and makes difficult estimating the efficacy and safety of treatments for chronic diseases in persons with frailty. This is extremely important if we consider that according to our results 70% of frail individuals present also with hypertension. In this context, the SPRINT trial showed that intensive control leads to a reduction in cardiovascular events both in frail persons,12 but this trial excludes most complex older adults, such as those presenting with cognitive impairment or psychiatric disorders, and those institutionalised. The lack of evidence regarding the treatment of hypertension in frail older people has been highlighted in the recently issued guidelines for the management of hypertension that recognise the role of BP-lowering therapy as one of the few interventions to reduce mortality risk in frail older individuals, but did not make any specific recommendations regarding treatment of hypertension in frailty individuals.14

Second, frailty is associated with limited life expectancy; as described by results of the SHARE study, life expectancy for frail individuals at age of 70 years ranges between 0.1 and 1.8 years in men and between 0.4 and 5.5 years in women.52 Therefore, in frail individuals the time-until-benefit of a given treatment might exceed the life expectancy and this might modify the risk–benefit ratio of preventive treatments for chronic diseases, including hypertension, which may require several years before showing a beneficial effect.

Third, frail individuals have an increased risk of iatrogenic illness. Cullian et al showed among hospitalised older adults frailty doubles the risk of developing an adverse drug reaction.53 Finally, frailty might be associated with poor medication adherence to antihypertensive medications.54

These data underline the importance of assessing frailty when treating hypertension and possibly to set individual targets of BP control for persons with frailty. Interestingly, in the SPRINT trial frail participants in the intensive BP control group experienced a significantly lower reduction of SBP compared with non-frail participants (10.8 vs 13.5 mm Hg, p=0.01), underling possible difficulties in lowering BP in frail persons.12

The meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies did not show any significant association between frailty and hypertension. Chronic diseases, including hypertension, are considered to be major determinants of frailty in theoretical models, and the negative effect of hypertension on cardiovascular outcomes can lead to frailty.55 However, our findings might be explained by the fact that cross-sectional data assess a single time point and are unable to evaluate the role of hypertension at differing stages of the frailty process.

Only four longitudinal studies assessed the impact of hypertension on incident frailty, providing conflicting results. This observation is in line with results of RCTs that were not able to show any impact of treatment of hypertension on onset of frailty.13 56 A possible explanation for this lack of effect could be that that persons developing frailty might be more likely to be lost to follow-up, and this selective drop out makes it difficult to draw any firm conclusions about the effect of the treatment on these frailty-related outcomes.57

Strengths and limitations

We performed a comprehensive literature search and a careful study selection and quality assessment, providing a reliable overview of the evidence in the field of hypertension and frailty. In addition, selected studies enrolled mainly community-dwelling samples and this enhances the generalisability of our findings. However, our findings present some limitations. First, we detected a significant heterogeneity among the studies which can be explained by the different definitions of frailty and hypertension and the demographic differences across studies. This heterogeneity is partially buffered by the absence of evident publication bias, and the reliability of our findings is increased by the low-to-moderate risk of methodological bias. Second, the cross-sectional design of 28 out of 32 studies limits the opportunity of assessing a cause–effect association between frailty and hypertension. In addition, the four longitudinal studies retrieved by our literature search provided conflicting evidence on the association between frailty and hypertension. Third, the meta-analyses included only studies that defined frailty based on the CHS criteria. Therefore, we cannot exclude that the described association of frailty with hypertension varies if different criteria for frailty definition are adopted. Finally, most of the studies included in the review were not aimed to assess hypertension and its relationship with frailty. For this reason, hypertension was poorly defined in most studies and this might lead to possible concerns about the methodology used to assess this condition.

Conclusion

The present study shows that frailty is common in persons with hypertension. Given the possible influence of frailty on risk–benefit ratio of treatment for hypertension and its high prevalence, it is important to assess the presence of this condition in persons with hypertension. In addition, limited studies assessing the association of these conditions are available. Further research, including a more rigorous and standardised assessment of frailty, and based on longitudinal designs, is needed to untangle the relationship between frailty and hypertension and to allow for the identification of pros and the cons of the pharmacological treatment, and possible targets for therapy in this population, leading ultimately to the development of specific recommendations for the treatment of hypertension in frail people.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

DLV and KMP contributed equally.

Contributors: Conception of the work: DLV, KMP and GO. Article evaluation: DLV and KMP. Data analysis: DLV. Results interpretation: DLV, KMP, GO and AM. Drafting the article: DLV and GO. Critical revision of the manuscript: RB, SG, LG, AM and KMP. Final approval of the manuscript: all the authors. All the authors fulfill the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Funding: The work reported in this publication was co-funded by the European Commission through the 3rd Health Programme, under the Grant Agreement n° 724099. The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Disclaimer: The authors declare no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data are available within the appendices.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. . Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, et al. . Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1487–92. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Santos-Eggimann B, Cuénoud P, Spagnoli J, et al. . Prevalence of frailty in middle-aged and older community-dwelling Europeans living in 10 countries. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64:675–81. 10.1093/gerona/glp012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Onder G, Vetrano DL, Marengoni A, et al. . Accounting for frailty when treating chronic diseases. Eur J Intern Med 2018;56:49–52. 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Afilalo J, Alexander KP, Mack MJ, et al. . Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:747–62. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Molander L, Lövheim H, Norman T, et al. . Lower systolic blood pressure is associated with greater mortality in people aged 85 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1853–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01948.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hakala SM, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE. Blood pressure and mortality in an older population. A 5-year follow-up of the Helsinki Ageing Study. Eur Heart J 1997;18:1019–23. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Satish S, Freeman DH, Ray L, et al. . The relationship between blood pressure and mortality in the oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:367–74. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49078.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Bemmel T, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG, et al. . In a population-based prospective study, no association between high blood pressure and mortality after age 85 years. J Hypertens 2006;24:287–92. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000200513.48441.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Odden MC, Peralta CA, Haan MN, et al. . Rethinking the association of high blood pressure with mortality in elderly adults: the impact of frailty. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1162–8. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al. . Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315:2673–82. 10.1001/jama.2016.7050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Odden MC, Peralta CA, Berlowitz DR, et al. . Effect of intensive blood pressure control on gait speed and mobility limitation in adults 75 years or older: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:500–7. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. . 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018;71:1269–324. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harris R, Bradburn M, Deeks J, et al. . Metan: fixed-and random-effects meta-analysis. Stata J 2008;8:3. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health 2014;72:39 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barzilay JI, Blaum C, Moore T, et al. . Insulin resistance and inflammation as precursors of frailty: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:635–41. 10.1001/archinte.167.7.635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bouillon K, Kivimäki M, Hamer M, et al. . Diabetes risk factors, diabetes risk algorithms, and the prediction of future frailty: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:851.e1–e6. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Castrejón-Pérez RC, Jiménez-Corona A, Bernabé E, et al. . Oral disease and 3-year incidence of frailty in Mexican older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017;72:951–7. 10.1093/gerona/glw201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Doba N, Tokuda Y, Goldstein NE, et al. . A pilot trial to predict frailty syndrome: the Japanese Health Research Volunteer Study. Exp Gerontol 2012;47:638–43. 10.1016/j.exger.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sousa AC, Dias RC, Maciel ÁC, et al. . Frailty syndrome and associated factors in community-dwelling elderly in Northeast Brazil. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012;54:e95–e101. 10.1016/j.archger.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Avila-Funes JA, Helmer C, Amieva H, et al. . Frailty among community-dwelling elderly people in France: the three-city study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63:1089–96. 10.1093/gerona/63.10.1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Basile G, Catalano A, Mandraffino G, et al. . Relationship between blood pressure and frailty in older hypertensive outpatients. Aging Clin Exp Res 2017;29 10.1007/s40520-016-0684-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bastos-Barbosa RG, Ferriolli E, Coelho EB, et al. . Association of frailty syndrome in the elderly with higher blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Hypertens 2012;25:1156–61. 10.1038/ajh.2012.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Calado LB, Ferriolli E, Moriguti JC, et al. . Frailty syndrome in an independent urban population in Brazil (FIBRA study): a cross-sectional populational study. Sao Paulo Med J 2016;134:385–92. 10.1590/1516-3180.2016.0078180516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Castrejón-Pérez RC, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Cesari M, et al. . Diabetes mellitus, hypertension and frailty: A population-based, cross-sectional study of Mexican older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2017;17:925–30. 10.1111/ggi.12805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chang SF, Yang RS, Lin TC, et al. . The discrimination of using the short physical performance battery to screen frailty for community-dwelling elderly people. J Nurs Scholarsh 2014;46:207–15. 10.1111/jnu.12068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chung CP, Chou KH, Chen WT, et al. . Cerebral microbleeds are associated with physical frailty: a community-based study. Neurobiol Aging 2016;44:143–50. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fattori A, Santimaria MR, Alves RM, et al. . Influence of blood pressure profile on frailty phenotype in community-dwelling elders in Brazil - FIBRA study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013;56:343–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Frisoli A, Ingham SJ, Paes ÂT, et al. . Frailty predictors and outcomes among older patients with cardiovascular disease: Data from Fragicor. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015;61:1–7. 10.1016/j.archger.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guessous I, Luthi JC, Bowling CB, et al. . Prevalence of frailty indicators and association with socioeconomic status in middle-aged and older adults in a swiss region with universal health insurance coverage: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Aging Res 2014;2014:1–8. 10.1155/2014/198603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kang MG, Kim SW, Yoon SJ, et al. . Association between frailty and hypertension prevalence, treatment, and control in the elderly Korean Population. Sci Rep 2017;7:7542 10.1038/s41598-017-07449-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Klein BE, Klein R, Knudtson MD, et al. . Frailty, morbidity and survival. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2005;41:141–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2005.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lahousse L, Maes B, Ziere G, et al. . Adverse outcomes of frailty in the elderly: the Rotterdam Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:419–27. 10.1007/s10654-014-9924-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee JS, Auyeung TW, Leung J, et al. . Physical frailty in older adults is associated with metabolic and atherosclerotic risk factors and cognitive impairment independent of muscle mass. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:857–62. 10.1007/s12603-011-0134-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nadruz W, Kitzman D, Windham BG, et al. . Cardiovascular dysfunction and frailty among older adults in the community: the ARIC study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017;72:958–64. 10.1093/gerona/glw199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ng TP, Feng L, Nyunt MS, et al. . Frailty in older persons: multisystem risk factors and the Frailty Risk Index (FRI). J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:635–42. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O’Connell MD, Savva GM, Fan CW, et al. . Orthostatic hypotension, orthostatic intolerance and frailty: the irish longitudinal study on aging-TILDA. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015;60:507–13. 10.1016/j.archger.2015.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ramsay SE, Arianayagam DS, Whincup PH, et al. . Cardiovascular risk profile and frailty in a population-based study of older British men. Heart 2015;101:616–22. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ravindrarajah R, Hazra NC, Hamada S, et al. . Systolic blood pressure trajectory, frailty, and all-cause mortality >80 years of age: cohort study using electronic health records. Circulation 2017;135:2357–68. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ricci NA, Pessoa GS, Ferriolli E, et al. . Frailty and cardiovascular risk in community-dwelling elderly: a population-based study. Clin Interv Aging 2014;9:1677–85. 10.2147/CIA.S68642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Serra-Prat M, Papiol M, Vico J, et al. . Factors associated with frailty in community-dwelling elderly population. A cross-sectional study. Eur Geriatr Med 2016;7:531–7. 10.1016/j.eurger.2016.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tavares DM, Colamego CG, Pegorari MS, et al. . Cardiovascular risk factors associated with frailty syndrome among hospitalized elderly people: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J 2016;134:393–9. 10.1590/1516-3180.2016.0028010616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vaingankar JA, Chong SA, Abdin E, et al. . Prevalence of frailty and its association with sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and resource utilization in a population of Singaporean older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2017;17 10.1111/ggi.12891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Watanabe Y, Hirano H, Arai H, et al. . Relationship Between Frailty and Oral Function in Community-Dwelling Elderly Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:66–76. 10.1111/jgs.14355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wong CH, Weiss D, Sourial N, et al. . Frailty and its association with disability and comorbidity in a community-dwelling sample of seniors in Montreal: a cross-sectional study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2010;22:54–62. 10.1007/BF03324816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wu IC, Shiesh SC, Kuo PH, et al. . High oxidative stress is correlated with frailty in elderly chinese. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1666–71. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02392.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yanagita I, Fujihara Y, Eda T, et al. . Low glycated hemoglobin level is associated with severity of frailty in Japanese elderly diabetes patients. J Diabetes Investig 2018;9 10.1111/jdi.12698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mack MJ, Stoler R. Intervention for aortic stenosis: the measurement of frailty matters. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:701–3. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Joseph SM, Manghelli JL, Vader JM, et al. . Prospective Assessment of Frailty Using the Fried Criteria in Patients Undergoing Left Ventricular Assist Device Therapy. Am J Cardiol 2017;120:1349–54. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Van Spall HG, Toren A, Kiss A, et al. . Eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials published in high-impact general medical journals: a systematic sampling review. JAMA 2007;297:1233–40. 10.1001/jama.297.11.1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Romero-Ortuno R, Fouweather T, Jagger C. Cross-national disparities in sex differences in life expectancy with and without frailty. Age Ageing 2014;43:222–8. 10.1093/ageing/aft115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cullinan S, O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, et al. . Use of a frailty index to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing and adverse drug reaction risks in older patients. Age Ageing 2016;45:115–20. 10.1093/ageing/afv166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chudiak A, Jankowska-Polańska B, Uchmanowicz I. Effect of frailty syndrome on treatment compliance in older hypertensive patients. Clin Interv Aging 2017;12:805–14. 10.2147/CIA.S126526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–56. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Applegate WB, Pressel S, Wittes J, et al. . Impact of the treatment of isolated systolic hypertension on behavioral variables. Results from the systolic hypertension in the elderly program. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:2154–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Di Bari M, Pahor M, Franse LV, et al. . Dementia and disability outcomes in large hypertension trials: lessons learned from the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP) trial. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:72–8. 10.1093/aje/153.1.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024406supp001.pdf (450.1KB, pdf)