Abstract

Individuals acting as surrogate decision makers for critically ill patients frequently struggle in this role and experience high levels of long-term psychological distress. Prior interventions designed to improve the sharing of information by the clinical team with surrogate decision makers have demonstrated little effect on surrogates’ outcomes or clinical decisions. In this report, we describe the study protocol and corresponding intervention fidelity monitoring plan for a multicenter randomized clinical trial testing the impact of a multifaceted surrogate support intervention (Four Supports) on surrogates’ psychological distress, the quality of decisions about goals of care, and healthcare use. We will randomize the surrogates of 300 incapacitated critically ill patients at high risk of death and/or severe long-term functional impairment to receive the Four Supports intervention or an education control. The Four Supports intervention adds to the intensive care unit (ICU) team a trained interventionist (family support specialist) who delivers four types of protocolized support—emotional support; communication support; decisional support; and, if indicated, anticipatory grief support—to surrogates through daily interactions during the ICU stay. The primary outcome is surrogates’ symptoms of anxiety and depression at 6-month follow-up, measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Prespecified secondary outcome measures are the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness Scale (modified for use with surrogates) and Impact of Event Scale scores at 3- and 6-month follow-up, respectively, together with ICU and hospital lengths of stay and total hospital cost among decedents. The fidelity monitoring plan entails establishing and measuring adherence to the intervention using multiple measurement methods, including daily checklists and coding of audiorecorded encounters. This approach to intervention fidelity may benefit others designing and testing behavioral interventions in the ICU setting.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01982877).

Keywords: patient-centered, intervention research, surrogate decision-making, intensive care, clinical trial

Annually, the short- and long-term health of millions of patients is threatened by critical illness (1). Most intensive care unit (ICU) patients at high risk of death or severe disability are incapacitated by their illness, and therefore clinicians turn to patients’ family members or other loved ones to participate in making decisions about goals of care (2). However, there are two well-documented problems with surrogate decision-making in ICUs. First, family members often experience high levels of psychological distress during the ICU experience, and these symptoms of anxiety and depression become persistent for a large subgroup of surrogates (3–5). Second, inadequate discussion of prognosis, patient values, and treatment options often leads to poorly informed decisions that do not reflect the patient’s values or preferences (6–9) and frequently results in overtreatment that contributes to the high costs of medical care at the end of life.

Despite the scope of the problems affecting surrogates in ICUs, there is little evidence from randomized trials about how to mitigate surrogates’ psychological distress or how to improve the quality of decision-making about goals of care in ICUs. Prior studies of interventions that focused on better information sharing with surrogates found no effect on end-of-life decisions; these studies did not assess the intervention’s impact on psychological distress (10, 11). A growing body of research suggests that improving outcomes may require going beyond providing better information to surrogates to also attend to the emotional and psychological difficulty of the experience (10–12). We therefore developed and pilot tested the Four Supports intervention (13).

The intervention uses trained interventionists, working as members of the ICU clinical team, to deliver communication support, decision support, and emotional support, together with anticipatory grief support to the surrogates of critically ill adults. We hypothesize that by addressing both their emotional and informational needs, surrogates’ long-term psychological distress will be lessened while the quality and patient centeredness of their decision-making will be improved.

In this article, we outline the study protocol for the Four Supports Trial following the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) framework for trials of nonpharmacological treatments (14). We provide a detailed description of the intervention, the study protocol, our program to monitor and maintain intervention fidelity, strategies we use in trial conduct, and a brief discussion of several key design decisions. This level of detail will enable others to reproduce the intervention should the trial results be positive.

Methods

Trial Design

This study is a patient-level, equally randomized, parallel-group superiority trial comparing the Four Supports intervention with an education control. Our primary outcome for the trial, on which we based our sample size and power calculations, is the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (15) score among surrogates at 6-month follow-up. The HADS was chosen for its reliability, its ecological and face validity, and the low level of respondent burden it imposes. In addition to mitigating surrogates’ psychological symptom burden, we designed the intervention to improve the quality of decisions in the setting of advanced critical illness. We therefore measure secondary outcomes that assess dimensions of decision-making quality, patient outcomes, and healthcare use.

Study Setting

We recruit patients from six ICUs in two hospitals within the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center health system, one a 735-bed quaternary care regional referral center that serves as the university’s primary teaching hospital and the other a 495-bed academically affiliated tertiary care center, serving a local urban population with a strong charity focus. Among the ICUs selected at the regional referral center are the neuroscience ICU, neurotrauma ICU, and surgical trauma ICU, all of which follow a model of comanagement by the intensivist and the surgical/subspecialist team. At the tertiary care center, we enroll in the trauma burn ICU, cardiovascular ICU, and medical ICU. The trauma burn and cardiovascular ICUs use a comanagement model with care provided by the intensivist and surgical/subspecialist team. The medical ICU employs two models: A closed staffing model is used for medical patients, and comanagement by the intensivist and surgical/subspecialist team is used for neurosurgical and stroke patients. We chose this diversity of ICU types because it is representative of the various clinical contexts in which surrogate decision-making typically takes place, thereby enhancing the generalizability of study findings. Approval for this study was granted by the University of Pittsburgh Human Research Protection Office (approval PRO13060415).

Study Sample and Eligibility Criteria

Patients

Patients are eligible if they are 21 years of age or older, lack decisional capacity as judged by the treating physician, and are judged by the treating physician to have a greater than 40% risk of dying and/or a greater than 40% risk of new long-term functional impairment, defined as being “dependent upon others for more than 2 activities of daily living” 6 months from the time of screening. Patients are ineligible if they lack a surrogate decision maker, have been listed for organ transplant, are incarcerated, or have had a decision for comfort-focused care made before the time of screening.

Surrogates

We enroll one primary surrogate and up to three additional surrogates per patient. The primary surrogate is determined by the patient’s advance directive or, in the absence of a directive, by using the hierarchy delineated by Pennsylvania state law. Additional surrogates are identified by asking the primary surrogate to identify those who would be included in decision-making for the patient. We chose to allow multiple surrogates per patient to capture the clinical reality that multiple individuals often share the responsibility of surrogate decision-making (16–18). Exclusion criteria are being younger than 18 years of age, being non–English speaking, and having physical or cognitive deficits that prevent the individual from completing questionnaires.

Physicians

We enroll the eligible patient’s attending physician. If the attending physician rotates off service while the patient is still in the ICU, we enroll the attending physician who takes over care. We exclude physicians who are study investigators.

Participant Screening and Recruitment

Research staff perform daily screening in the electronic medical record for patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale (19) score less than 14 to identify those most likely to be lacking decision-making capacity. Next, research staff review each of these patients with the attending physician to identify whether patients meet study enrollment criteria. If there is uncertainty about the risk of in-hospital mortality, staff calculate the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II (20) score to assist in the determination of mortality risk. We use a threshold APACHE II score greater than or equal to 22 for mortality risk because an APACHE II score of 20–24 corresponds to an approximate 40% risk of in-hospital mortality for the nonoperative ICU patient population (20).

Using a standardized script, the bedside nurse requests permission for the research staff to describe the study to eligible surrogates. All surrogates and physicians who agree to participate provide written informed consent.

Compensation

Enrolled surrogates are compensated $20 for completing the baseline questionnaire, $40 for completing the 3-month follow-up phone interview, and $40 for completing the 6-month follow-up phone interview. Enrolled physicians are compensated $10 for completing the baseline assessment.

Randomization

We randomize enrolled patients to the intervention or control arm with equal allocation using a computer-aided permuted block design, stratified by study site. Each member of the study staff who enrolls participants has a unique login to our automated randomization system. Allocation concealment is ensured because the system assigns patient participants to a study arm and provides a study identification number only after enrollment. Double blinding is not possible, given the nature of the intervention; however, all study staff who collect outcome data during long-term follow-up are blinded to allocation. In addition, only the study statistician and members of the data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) have access to unblinded data before study completion.

Intervention

The intervention is conceptually grounded in the Cognitive Emotional Decision Making framework and the Ottawa Decision Support Framework (12, 21). The Cognitive Emotional Decision Making framework posits that medical decisions are influenced not only by cognitive and informational considerations but also by the emotional issues that arise from the health threat and from the requirement to make difficult, highly consequential decisions for a family member. The Ottawa Decision Support Framework is an evidence-based theory positing that better patient/family decision-making can be achieved by 1) identifying decision support needs, 2) providing tailored decision support, and 3) evaluating the decision-making process and outcomes (21, 22). The development and pilot testing of the Four Supports intervention have been described previously (13).

The Four Supports intervention adds to the ICU team a trained interventionist (introduced as the family support specialist) to deliver four types of protocolized support—emotional support; communication support; decisional support; and, if indicated, anticipatory grief support—to surrogates through daily interactions during the ICU stay. (See section entitled Interventionist Training and Certification) The interventionist functions in a full-time capacity as an integrated member of the ICU team and interacts with both the clinical team and surrogates daily, either in person or by telephone. In Table 1, we describe the activities undertaken by the interventionist to achieve the four types of support. Support is delivered through daily, protocol-driven interactions with surrogates and with the clinical team; sessions are conducted in a prescribed sequence, with each having defined objectives (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Interventionist activities in the Four Supports intervention

| Type of Support | Interventionist Actions |

|---|---|

| Emotional support | • Establish rapport |

| • Express empathy | |

| • Elicit concerns | |

| • Acknowledge the difficulty of the situation | |

| • Convey active listening | |

| • Use touch as appropriate | |

| • Provide contact information and maintain availability in person or by phone | |

| Communication support | • Elicit family questions |

| • Facilitate clinician–family conferences | |

| • Share information with clinicians about family stressors, structure, questions, and concerns in advance of clinician–family conferences | |

| • Assist the family to ask questions during conferences | |

| • Listen for key misunderstandings and concerns after interactions with clinicians and address misunderstandings | |

| • Ensure understanding of the daily plan and next steps after each encounter | |

| Decision support | • Explain principles of surrogate decision-making |

| • Engage in values elicitation | |

| • Ensure discussion of treatment options, prognosis, and patient values during family conferences | |

| • Help family synthesize key information from clinicians | |

| • Maintain focus on the patient as a person | |

| Anticipatory grief support | • Elicit spiritual needs and involve spiritual care as needed |

| • Offer the opportunity for the family to gather at the bedside | |

| • Facilitate life review | |

| • Create a space for family members to say goodbye | |

| • Offer to discuss what might happen during the dying process |

Table 2.

Summary of intervention sessions

| Session Type | Session Timing | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention arm | ||

|

Sessions with surrogates | ||

| First interaction with surrogates | Within 24 h of enrollment* |

|

| Preconference meeting with surrogates | Before any clinician–family conference (same day) |

|

| Clinician–family conference | Within 48 h of enrollment and weekly* |

|

| Postconference with surrogates | After any clinician–family conference (same day) |

|

| Daily check-in with surrogates | Daily after first interaction† |

|

| Anticipatory grief session | Upon decision to withdraw life support/when death is imminent |

|

|

Sessions with the physician | ||

| First conversation with the physician | Within 24 h of enrollment* |

|

| Preconference meeting with the physician | Before any clinician–family conference (same day) |

|

| Postconference with the physician | After any clinician–family conference (same day) |

|

| Daily check-in with the physician | Daily after the first conversation with the physician† |

|

| Control arm | ||

| Control education session 1 | Day 2 of enrollment* |

|

| Control education session 2 | Day 5 of enrollment* | |

In the event a session falls on a weekend or holiday, the session may be held a day earlier or later than prescribed in the protocol.

Daily check-in sessions are not required if a clinician–family meeting is held on that day. If the family is not present in the hospital, the daily check-in with the family may be completed by phone.

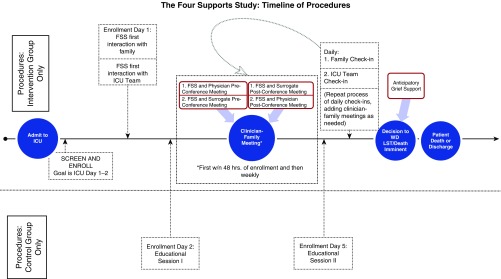

Key tasks of the interventionist are to facilitate the conduct of a clinician–family conference within 48 hours of study enrollment and to provide protocolized support and information to surrogates and the physician before, during, and after the conference. In advance of the conference, the interventionist reviews a list of common questions with surrogates to understand what their questions are. The interventionist then shares this information with the physician in advance of the conference (together with other information, such as family structure and dynamics, surrogates’ expectations about recovery, and patients’ advance directives) in the form of a one-page summary (see Appendix E1 in the online supplement). A timeline of intervention and education control procedures is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline for delivery of intervention and control procedures. FSS = family support specialist; ICU = intensive care unit; LST = life-sustaining treatment; WD = withdraw.

Education Control

The control arm consists of usual care plus education because this emulates standardized best practice for high-quality patient-centered care. This choice of a robust control condition ensures that positive results can be attributed to the effectiveness of the intervention and not merely to the amelioration of poor care. The education control arm involves two education sessions delivered by the interventionist on Day 2 and Day 5 of enrollment. The first control session entails a detailed review, by the interventionist, of the family information brochure that is given to families as part of usual care in each ICU. The brochure consists of information about the unit’s visiting policy, the rounding schedule, and information about how to contact the unit. In the second control session, the interventionist reviews a published patient/family education brochure that describes common ICU care (e.g., mechanical ventilation, sedation, tubes and lines, monitoring) (23) and offers clarifications of this information in response to questions. During the education control sessions, interventionists convey a kind demeanor but refrain from providing explicit emotional support. If families ask questions about the patient’s status or treatments, they are advised to discuss those questions with the clinical team.

Interventionist Training and Certification

To enhance the scalability of the intervention, we designed it to be feasibly deployed by nurses or social workers with experience in the inpatient setting but no other advanced training in patient counseling or coaching. The interventionists are nurses or medical social workers with clinical experience in the ICU setting.

Training

Our approach to training the interventionists is grounded in self-efficacy theory and principles of adult learning (24). Training used three methods: directed reading, didactic teaching from investigators, and supervised skills practice. At the start of training, each interventionist receives a training manual containing a detailed description of each intervention and control session, together with sample language for each component of the intervention and control conditions. The manual also contains supplementary readings on key intervention principles, such as surrogate decision-making, communicating empathetically, preparing families for the death of a loved one, and enhancing patient dignity at the end of life.

After completing the readings, the interventionist completes didactic training sessions with the investigators in which they review the purpose of each session and discuss common pitfalls, key goals, and key skills particular to each session (8 h total). This is followed by supervised skills practice in which the investigator models the interaction and the interventionist practices via role-play simulation with trained medical actors, using standardized cases. The investigators provide direct observation and feedback, allowing the interventionist to iteratively refine the language and delivery for each session (12 h total).

Certification

At the conclusion of training, each interventionist is required to pass a certification examination before beginning participant enrollment. For the certification examination, the interventionist takes part in a simulation of each intervention session using trained medical actors and standardized vignettes, with direct observation by three members of the research team, including the principal investigator. Interventionists must demonstrate greater than or equal to 90% adherence to the core skills of the intervention to be certified.

Monitoring and Maintaining Intervention Fidelity

Intervention fidelity monitoring

Our approach to monitoring and maintaining intervention fidelity was guided by recommendations of the National Institutes of Health Behavior Change Consortium (25). It involves structured training of interventionists, multimodal assessment of the fidelity with which the interventionists deliver the intervention and control protocols, and ongoing support and education of the interventionists. The assessment methods include 1) daily completion of a checklist by the interventionist documenting their activity and 2) analysis by the study team of a random sample of audiorecorded sessions to determine the extent to which each protocol-based objective is achieved.

Written documentation

Each day, the interventionist completes a written checklist to record which intervention sessions (e.g., first meeting with surrogates, daily check-in) occur for each enrolled patient (Appendix E2). The tool also allows interventionists to record protocol deviations that are beyond the control of the interventionist—, such as surrogates canceling a meeting or the need to reschedule a meeting owing to a physician emergency.

Trained research staff review all cases (using the daily checklist as a source document) to evaluate the overall adherence to the sequence and timing of protocolized sessions with surrogates and clinical staff. Overall adherence is scored using a customized scoring sheet (Appendix E3), and the threshold for compliance is set at 90%.

Audiorecorded encounters

All sessions (sessions with physicians, sessions with surrogates, and clinician–family conferences) are audiorecorded. Session-specific intervention fidelity monitoring forms were created and tested for each of the intervention and control sessions (an example is shown in Appendix E4). Trained research staff randomly sample 20% of each interventionist’s recorded sessions for evaluation. We use a sampling frame, stratified by session, and sample without replacement to ensure equal sampling across session types. Using the appropriate intervention fidelity monitoring form for guidance, the rater listens to the selected audiorecording, integrates information found in the field notes, then determines and records a rating for each content and quality element required for the session. The threshold for adherence to content and quality of intervention delivery are set at 90% and greater than or equal to 2 (on a scale of 1–3), respectively. Raters also monitor for the delivery of problematic content, such as offering pure opinion, engaging in unilateral decision-making, displaying impatience, or disrespecting patient/surrogate values.

Because the interventionists deliver both the intervention and education control sessions, there is particular vigilance to monitor for any “bleed over” of intervention elements, such as rapport building or emotional support during the conduct of education control sessions. We made the decision to have the interventionist deliver the education control sessions in response to funding limitations that precluded the ability to hire separate study personnel for control session delivery. However, we took a number of steps to ensure that the control sessions did not contain any key components of the intervention. First, we developed very prescribed content for the control sessions. Second, we provided in-depth training about the need to avoid delivering intervention content. Third, the monitoring of audiorecorded control sessions offers the opportunity to ensure there is no “bleed over” of intervention content into the control sessions.

Intervention fidelity maintenance

Intervention fidelity maintenance is achieved by the following means:

-

1.

Enactment of the monitoring plan;

-

2.

Completion of field notes by interventionists after each intervention session;

-

3.

Weekly supervision sessions with the investigators, with opportunity to discuss concerns noted in the field notes and review of monthly intervention fidelity monitoring reports;

-

4.

Quarterly booster sessions for the interventionists to maintain delivery skill and identify potential drift; and

-

5.

Remediation and retesting in response to identified deficiencies or drift in quality of intervention delivery.

A report containing monthly and cumulative overall adherence statistics is generated for the principal investigator and study staff, summarizing the content and quality of intervention or control condition delivery by interventionist or by session. This level of detail permits the team to identify areas where full implementation is not being achieved, and they can undertake corrective actions to better implement the intervention. If any potentially problematic content is noted, it is flagged for review during a supervision meeting. The integration of intervention fidelity monitoring and supervision is shown in Appendix E5.

Outcomes

Table 3 contains a summary of all outcome measures, data sources, and time points for collection.

Table 3.

Primary and secondary outcomes, associated measures, and data collection time points

| Instrument | Data Source | Time Point Collected |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)* | Surrogate(s) | 6-mo follow-up |

| Prespecified secondary outcomes | ||

| Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale† | Surrogate(s) | 3-mo follow-up |

| Impact of Event Scale (IES)‡ | Surrogate(s) | 6-mo follow-up |

| Total hospital cost | Charge data | At hospital discharge |

| ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay | Registration data/chart abstraction | At hospital discharge |

| Additional measures | ||

| Concordance between clinicians and surrogates about patient’s prognosis (CSCS)§ | Surrogate(s) and physician | Baseline, Day 5, and weekly |

| Quality of Communication Questionnaire (QOC)‖ | Surrogates(s) | Day 5 |

| Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS)¶ | Surrogate(s) | Baseline, Day 5 |

| Impact of Event Scale (IES)‡ | Surrogate(s) | 3-mo follow-up |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)* | Surrogate(s) | 3-mo follow-up |

| Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) scale** | Surrogate(s) | 3- and 6-mo follow-up |

| Discharge disposition | Registration data/chart abstraction | Postdischarge |

| Code status change, decision to withhold/withdraw mechanical ventilation, and additional treatments | Chart abstraction | Postdischarge |

| Vital status | Surrogate(s) | 3- and 6-mo follow-up |

| Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living†† | Surrogate(s) | 3- and 6-mo follow-up |

| Discharge disposition | Registration data/chart abstraction | Postdischarge |

Definition of abbreviations: CSCS = Clinician-Surrogate Concordance Scale; DCS = Decisional Conflict Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICG = Inventory of Complicated Grief; ICU = intensive care unit; IES = Impact of Event Scale; QOC = Quality of Communication Questionnaire; PPPC = Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness scale.

HADS is a 14-item assessment with subscales for anxiety and depression. Each domain has a score range of 0–21 with the following interpretation: 0–7 = normal; 8–10 = borderline abnormal; and 11–21 = abnormal.

PPPC is a 12-item instrument that measures the patient-centeredness of care with modifications for use by surrogates. It has demonstrated validity and reliability when used by surrogates (Cronbach’s α = 0.71).

IES is a 15-item tool measuring total stress (score range, 0–75) with subscales for intrusiveness (score range, 0–35) and avoidance (score range, 0–40). Total stress score is interpreted as follows: 0–8 = subclinical range; 9–25 = mild range; 26–43 = moderate range; and 44+ = severe range. A score greater than or equal to 30 indicates a high risk of post-traumatic stress disorder.

CSCS is the absolute difference between surrogate and physician/nurse responses to the question of perceived likelihood of survival, with responses recorded on a probability scale with qualitative anchors (e.g., no chance of surviving) to aid in comprehension for low-numeracy individuals. The CSCS has a range of values between 0 and 100%. Scores range from 0 (no decisional conflict) to 100 (extremely high decisional conflict) (Cronbach’s α = 0.92)

QOC is a 13-item instrument measuring the quality of communication about end of life. It has a six-item subscale for general communication skills and a seven-item scale for communication about end of life (Cronbach’s α = 0.79).

DCS is a 16-point instrument measuring individuals’ perceptions of uncertainty in choosing options and modifiable factors contributing to uncertainty, such as feeling uninformed, unclear about personal values, and unsupported in decision-making.

Prigerson ICG is a 19-item tool used to discriminate pathological grieving from normal bereavement. Scores greater than or equal to 30 at 6 months postbereavement are considered clinically significant.

The Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (Katz ADL) is an instrument measuring functional status in the domains of bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring continence and feeding. Scores range from 0 to 6; 6 = indicates full function, 4 = moderate impairment, and ≤2 = severe functional impairment.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome on which we base our sample size and power calculations is surrogate decision makers’ symptoms of anxiety and depression at 6 months posthospitalization as measured by the HADS (15). The HADS has established reliability and validity among ICU surrogates and has been used in other trials of biobehavioral interventions (26, 27). Specifically, responsiveness of the HADS score to change has been documented with multiple psychosocial and communication interventions (28–30).

Prespecified secondary outcomes

Our prespecified secondary outcomes correspond to other key hypotheses we pose regarding the effect of the intervention on the patient centeredness of care, as well as on healthcare use. Thus, our secondary outcomes include the modified Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale (31) score at 3 months, the Impact of Event Scale (IES) (32) score at 6 months, and measures of healthcare use among decedents—ICU and hospital lengths of stay (LOSs) and hospital costs during the index hospitalization.

Other Measures

We assess decision-making and quality of communication using the Clinician-Surrogate Concordance Scale score (baseline, Day 5, weekly), the Quality of Communication Scale (33) (Day 5), and the Decisional Conflict Scale (34) (baseline, Day 5). We also assess surrogates’ symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder using the IES (32) (3 mo); the HADS (3 mo); and, among patients who died, bereavement symptoms using the Prigerson Inventory of Complicated Grief (35) (3 and 6 mo).

We collect patient outcome data, including in-hospital mortality, decisions to change code status or withdraw/withhold mechanical ventilation or other life-sustaining treatments, and discharge disposition and resource use (cost and LOS) among survivors. In addition, during 3- and 6-month postdischarge follow-up calls with surrogates, we collect patient vital status; patient functional status, measured using the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (36); and surrogates’ use of mental health treatment.

Mixed Methods Substudy

In addition to the outcome measures described in Table 3, we will conduct a mixed methods assessment of surrogates’ and physicians’ experiences with the intervention after intervention delivery is completed. The quantitative portion of the assessment will involve questions assessing the degree to which participants perceive the intervention changed different domains of care processes. The qualitative portion will consist of semistructured interviews exploring the impact of the intervention on aspects the ICU experience, such as communication and decision-making. To avoid biasing the interpretation, these data will be collected and analyzed before the results of the trial are known.

Analysis Plan

We will conduct an intention-to-treat analysis with a two-sided α = 0.05. There are potentially several levels of nesting (e.g., surrogates within patient, patients within physician, and physicians within ICU). For the primary analysis, we will use linear mixed effects models for scale-ordered outcomes testing the effect of the intervention on HADS scores at 6 months postdischarge. Physicians and study sites will be treated as random effects in the model to adjust for the correlation within a physician and within a study site. To obtain a more parsimonious model, we will determine which levels of nesting to keep on the basis of statistical significance (α < 0.05) of the likelihood ratio test used to compare models with various nesting levels. We will use the same linear mixed effects modeling techniques for all other surrogate psychological health outcomes. If there are baseline differences in characteristics of participants in the intervention and control arms, we will incorporate these potential confounders into the model.

In the prespecified secondary analyses, we will first limit the cohort to patients’ primary surrogates. We will also analyze the impact of Four Supports on the prespecified secondary outcomes using models appropriate to the types of data: 1) linear mixed effects modeling for PPPC at 3 months and the IES at 6 months and 2) generalized linear modeling with γ-distribution and inverse link for costs and ICU and hospital LOS outcomes among decedents, to account for the nonnegative and skewed nature of these outcomes.

Finally, using the appropriate procedure, we will model the impact of the intervention on the remaining outcome measures. We will use linear mixed effects modeling for the Clinician-Surrogate Concordance Scale, Decisional Conflict Scale, and Quality of Communication Scale at Day 5; the IES and HADS at 3 months; and the Prigerson Inventory of Complicated Grief at 3 and 6 months. We will use generalized linear mixed effects modeling with binomial distribution and logit link to test the effect of the intervention on decisions to withdraw/withhold mechanical ventilation, decisions to change code status, and vital status at hospital discharge and at 6-month follow-up.

Sample size is based on two-sided α = 0.05 tests and conservative estimates of surrogate intraclass correlation coefficient (0.25) and surrogate dropout or loss to follow-up (20%). With 300 patients and 450 surrogates, our study has 80% power to detect small mean differences in HADS as small as 1.7 (SD, 5), whereas the minimal clinically significant difference in HADS among ICU patients is in the 1.5–2.3 range (37–39). With this sample size, our study will have 80% power to detect small to moderate effect size differences (d = 0.36) in PPPC score. Finally, the study will have 80% power to detect a difference as small as 5 days in ICU LOS among decedents.

We initially planned to increase the sample size from the needed 300 to 400 patients to increase the precision of the estimates of healthcare costs across arms. However, in the interim, new data were published indicating that cost analyses in this context would require an even larger sample size based on effect modification related to whether the patient lived or died (40). In light of this, and in consultation with the DSMB, the decision was made to target a sample size of 300 patients.

Missing Data

If any of the outcome or predicting variables are missing, we will examine the frequency (percent) of missing variables and subsequently conduct two different analyses: 1) complete case analysis by including only individuals with nonmissing data and 2) multiple imputed analysis by using the multivariate imputation by chained equations method with five complete datasets. Rubin’s method will be used to combine the results from the five imputed datasets. Differences between the two methods will be discussed.

Ethics

Approval for this study was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh Human Subjects Protection Office. The study is registered with the National Institutes of Health clinical trials registry (NCT01982877) and is overseen by a DSMB that meets annually. At its initial meeting, the DSMB recommended against planned interim analyses, given the low-risk nature of the intervention. The DSMB therefore will focus on monitoring trial progress and adverse events, if any occur.

Strategies for Trial Conduct

Conducting clinical research in the ICU setting presents challenges, including enrolling distressed surrogates, preventing burnout among interventionists, and promoting long-term follow-up among enrolled surrogates. In Table 4, we list strategies we employ to overcome these challenges.

Table 4.

Selected strategies for trial conduct

| Issue in Trial Conduct | Strategies Employed |

|---|---|

| Enhancing enrollment among distressed surrogates | • Interventionists network with ICU staff to build rapport. |

| • Unit staff are provided with a script to use when asking permission for the study staff to introduce the study—this minimizes variation and potential misinformation in descriptions of the study. | |

| • If study staff detect reluctance on the part of surrogates to enroll, they offer the opportunity for surrogates to think about it and ask if they may return the next day. | |

| • The study staff notify the PI of these “soft declines,” and the PI follows up with a phone call if able. | |

| Addressing potential distress and burnout among interventionists | • Interventionists are encouraged to use the “field notes” section of the daily checklist to record distressing events. |

| • Time is set aside each week during supervision sessions for interventionists to reflect on their experiences with a trained psychologist. | |

| Promoting long-term follow-up among enrolled surrogates | • Study staff send all participants a thank-you note and a notification of the approaching follow-up, indicating the window during which they will be contacted for 3- or 6-mo follow-up. |

| • If study staff are unable to contact the participant to complete either of the follow-up calls, they notify the PI. | |

| • The PI calls and speaks to the participant or leaves a message, conveying the participant’s importance to the study. |

Definition of abbreviations: ICU = intensive care unit; PI = principal investigator.

Discussion

We faced several key design decisions while planning the trial. Below we discuss the rationale for our level of randomization, required qualifications of individuals to be interventionists, and our strategy for robust assessment of the intervention.

Level of Randomization

An early design decision we faced was whether to randomize at the patient or ICU level. We considered ICU-level randomization as opposed to patient-level randomization to exclude any possibility of contamination arising through improvements in clinicians’ communication skills, but we opted against this approach for two reasons. First, a cluster-randomized trial of this type of intervention would require 15–20 centers for the study to be adequately powered and would more than triple the budget. Second, we believe the risk of contamination is low. The intervention consists primarily of one-to-one contact between the interventionist and the surrogates, and there are no elements of the intervention that attempt to improve clinicians’ communication skills. Intervention activities involving clinicians are limited to facilitating frequent family meetings and conveying to physicians information about the specific needs of individual families. Findings from our pilot study support the claim that the risk of contamination is low (13). We conducted in-depth interviews with physicians to elicit their experiences with the intervention. Physicians conveyed that the intervention changed the care provided to those in the intervention group by overcoming system-level barriers and did not impact the care provided to nonintervention patients. Finally, when evaluating the staffing patterns of study ICUs, we estimate that participating physicians will typically care for fewer than four patients during the enrollment period, which is unlikely to be adequate to change physicians’ communication skills. Nevertheless, our analysis plan permits us to assess for the occurrence of contamination by evaluating whether there are changes over time in the control arm related to care processes, such as the frequency of family meetings.

Qualifications of Interventionists

A second decision we faced was determining the optimal clinical background for those selected for the role of interventionist. The primary qualification we chose for interventionists is a background in ICU nursing or clinical social work. Interventionists could not be doctoral-level trained psychologists or counselors, nor could they be physicians. Our rationale for this choice is that we seek to test an intervention that uses staff already present in ICUs, rather than testing the impact of adding a trained psychologist to the care team. Individuals with more advanced training in counseling methods are costly to employ and not widely available in U.S. hospitals, and therefore creating an intervention with this staffing model would substantially limit the disseminability and public health impact of the intervention. We also considered restricting eligibility to advanced practice registered nurses, but again, this could limit the disseminability of the intervention, and our pilot study confirmed that it is feasible for a bedside nurse to acquire the skills for the interventionist role.

Strategy for Robust Assessment of the Intervention

A third issue we faced is, in the event of a negative trial, how to best understand the causes. As described in this protocol paper, we put in place a detailed strategy to assess and maintain intervention fidelity in order to minimize the chance that a negative trial result would arise from poor execution of the intervention. In addition, our analysis of the qualitative substudy data will offer insight into surrogates’ and clinicians’ experiences of the intervention.

Conclusions

This paper describes the Four Supports intervention and the detailed protocolization and intervention fidelity monitoring and maintenance plan we developed to test it. This methodology provides a template that may be of value to other trialists developing and testing complex behavioral interventions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health via National Institute on Aging grant R01AG045176 (D.B.W., principal investigator), a departmental T32 postdoctoral scholarship (T32-HL007820 [J.B.S.]), and a Cambia Health Foundation Sojourns Scholar Leadership Program award (J.B.S.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson RS, Rickert T, et al. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICU End-Of-Life Peer Group. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAdam JL, Dracup KA, White DB, Fontaine DK, Puntillo KA. Symptom experiences of family members of intensive care unit patients at high risk for dying. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1078–1085. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cf6d94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAdam JL, Fontaine DK, White DB, Dracup KA, Puntillo KA. Psychological symptoms of family members of high-risk intensive care unit patients. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21:386–393, quiz 394. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2012582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:336–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynn J, Teno JM, Phillips RS, Wu AW, Desbiens N, Harrold J, et al. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Perceptions by family members of the dying experience of older and seriously ill patients. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:97–106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-2-199701150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santilli S, Kemp AW, Tenner S, Kreling B, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients’ preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:545–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402243300807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prendergast TJ, Claessens MT, Luce JM. A national survey of end-of-life care for critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1163–1167. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.4.9801108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, Peterson LM, Wenger N, Reding D, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279:1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daly BJ, Douglas SL, O’Toole E, Gordon NH, Hejal R, Peerless J, et al. Effectiveness trial of an intensive communication structure for families of long-stay ICU patients. Chest. 2010;138:1340–1348. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Writing Group for the SUPPORT Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT) JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Power TE, Swartzman LC, Robinson JW. Cognitive-emotional decision making (CEDM): a framework of patient medical decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White DB, Cua SM, Walk R, Pollice L, Weissfeld L, Hong S, et al. Nurse-led intervention to improve surrogate decision making for patients with advanced critical illness. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21:396–409. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2012223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P CONSORT Group. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frey R, Hertwig R, Herzog SM. Surrogate decision making: do we have to trade off accuracy and procedural satisfaction? Med Decis Making. 2014;34:258–269. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12471729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vig EK, Taylor JS, Starks H, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Beyond substituted judgment: how surrogates navigate end-of-life decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1688–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White DB, Ernecoff N, Buddadhumaruk P, Hong S, Weissfeld L, Curtis JR, et al. Prevalence of and factors related to discordance about prognosis between physicians and surrogate decision makers of critically ill patients. JAMA. 2016;315:2086–2094. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Légaré F, O’Connor AC, Graham I, Saucier D, Côté L, Cauchon M, et al. Supporting patients facing difficult health care decisions: use of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:476–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray MA, Miller T, Fiset V, O’Connor A, Jacobsen MJ. Decision support: helping patients and families to find a balance at the end of life. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2004;10:270–277. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.6.13268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mount Prospect, IL: Society of Critical Care Medicine; 2000. Why patients look that way. [accessed 2017 Apr 21]. Available from: http://www.sccm.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/UNDERSTAND_Download.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glanz K, Rimer B. Theory at a glance: a guide for health promotion practice. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, et al. Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol. 2004;23:443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, Lemaire F, Hubert P, Canoui P, et al. French FAMIREA Group. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:17–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cameron IM, Crawford JR, Lawton K, Reid IC. Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:32–36. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X263794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinz A, Zweynert U, Kittel J, Igl W, Schwarz R. Measurement of change with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): sensitivity and reliability of change [in German] Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2009;59:394–400. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundin EC, Horowitz MJ. Impact of Event Scale: psychometric properties. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:205–209. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1086–1098. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, III, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, et al. Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59:65–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz S, Akpom CA. A measure of primary sociobiological functions. Int J Health Serv. 1976;6:493–508. doi: 10.2190/UURL-2RYU-WRYD-EY3K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cox CE, Hough CL, Carson SS, White DB, Kahn JM, Olsen MK, et al. Effects of a telephone- and web-based coping skills training program compared with an education program for survivors of critical illness and their family members: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:66–78. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201704-0720OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan KS, Aronson Friedman L, Bienvenu OJ, Dinglas VD, Cuthbertson BH, Porter R, et al. Distribution-based estimates of minimal important difference for Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Impact of Event Scale–Revised in survivors of acute respiratory failure. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;42:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puhan MA, Frey M, Büchi S, Schünemann HJ. The minimal important difference of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, Gold J, Ciechanowski PS, Shannon SE, et al. Randomized trial of communication facilitators to reduce family distress and intensity of end-of-life care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:154–162. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0900OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.