Abstract

Sulfate radical (SO4•−) is a strong, short-lived oxidant that is produced when persulfate (S2O82−) reacts with transition metal oxides during in situ chemical oxidation (ISCO) of contaminated groundwater. Although engineers are aware of the ability of transition metal oxides to activate persulfate, the operation of ISCO remediation systems is hampered by an inadequate understanding of the factors that control SO4•− production and the overall efficiency of the process. To address these shortcomings, the stoichiometric efficiency and products of transition metal-catalyzed persulfate oxidation of benzene were assessed with pure iron- and manganese-containing minerals, clays and aquifer solids. For most metal-containing solids, the stoichiometric efficiency, as determined by the loss of benzene relative to the loss of persulfate, approached the theoretical maximum. Rates of production of SO4•− or hydroxyl radical (HO•) generated from radical chain reactions were affected by the concentration of benzene, with rates of S2O82− decomposition increasing as the benzene concentration increased. Under conditions selected to minimize loss of initial transformation products through reaction with radicals, the production of phenol only accounted for 30%-60% of the benzene lost in the presence of O2. The remaining products included a ring cleavage product that appeared to contain an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde functional group. In the absence of O2, the concentration of the ring-cleavage product increased relative to phenol. The formation of the ring-cleavage product warrants further studies of its toxicity and persistence in the subsurface.

Introduction

In situ chemical oxidation (ISCO) has been used for several decades for the remediation of contaminated groundwater and aquifer solids.1 Recently, persulfate (S2O82−) has become popular as an oxidant in ISCO systems due to its ability to oxidize a variety of contaminants.2-3 When persulfate is injected into the subsurface without any other additives, it is activated by Fe(III)- and Mn(IV)-containing oxides to produce sulfate radical (SO4•−),4-5 an oxidant that reacts with a variety of contaminants.6-16 SO4•− also can be converted to hydroxyl radical (HO•) under alkaline conditions,17-19 or in the presence of chloride. 10,20-21 The effectiveness of ISCO depends on the rate of S2O82− activation and the yield of SO4•− and other reactive radicals. S2O82− activation rates and oxidant yields appear to be affected by the nature of the minerals and aquifer solids, the groundwater composition and the presence of organic contaminants that can initiate radical chain reactions that convert S2O82− into SO4•− and other reactive radicals. 2-3,5,22

To characterize the mechanism through which oxidants are activated in ISCO systems, it is important to understand the stoichiometric efficiency of the reaction (i.e., the number of moles of benzene transformed per mole of oxidant activated). For example, measurement of the yield of HO• in Fenton-like reactions catalyzed by metal oxides and aquifer solids indicated that less than 2% of the H2O2 was converted into HO•, and that aquifer solids with the highest ratios of Fe(III) oxides to Mn(IV) oxides exhibited the highest HO• yield.23-24 This type of information can be useful in the selection and the deployment of ISCO oxidants, and the development of approaches to increase oxidant yields for ex situ treatment systems.

Quantification of the stoichiometric efficiency in S2O82−-based ISCO systems is complicated by the slow rate of S2O82− loss and the complex radical chain reactions that occur in groundwater. To provide insight into the factors controlling persulfate activation and the mechanisms through which organic contaminants are transformed, experiments were conducted in which persulfate was activated by Fe(III) oxides, Mn(IV) oxides, clays and aquifer solids under conditions comparable to those in the groundwater, with benzene serving as a representative organic contaminant. By measuring the rates at which benzene and persulfate disappeared, as well as the rate of formation of oxidation products, it was possible to gain insight into the mechanism of persulfate activation by metal-containing solids and the complex nature of reactions initiated by SO4•− when organic contaminants are present.

Materials and Methods

A detailed description of the experimental setup and materials was presented previously.5 A brief summary is included below with specific details included as Text S1 in the Supporting Information (SI). Four types of pure minerals were studied: amorphous ferrihydrite (Fe(OH)3(s)), goethite (α-FeOOH(s)), pyrolusite (β-MnO2(s)) and silica (SiO2(s)). Two clay materials (nontronite and montmorillonite) and five aquifer solids collected from relatively uncontaminated locations at sites undergoing remediation were also studied. Details on the minerals, clays and aquifer solids and their characteristics are provided in Table S1 and text S1 in the SI. For SO4•− generation experiments, a 1 mM benzene solution was freshly prepared from anhydrous benzene (purity ≥ 99.8%, Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) in a 1-L glass volumetric flask filled with deionized (DI) water without headspace. The dissolved O2 concentration in all solutions was adjusted by purging with air, N2, or pure O2. Details on the control of dissolved O2 are provided as Text S2 in SI. The 1-L solution was buffered at pH 8.0 with 50 mM borate. In some experiments, synthetic groundwater was used to assess benzene oxidation by persulfate activation. The chemical composition of the synthetic groundwater was reported previously and reported as Table S2 in the SI5

To start an experiment, 250 mL of the benzene solution was quickly mixed with a pre-determined amount of solids in a 300-mL beaker, and persulfate was added to yield an initial concentration of 1 mM using aliquots of a freshly prepared 100 mM K2S2O8. After mixing, the suspension was immediately transferred to multiple sealed glass tubes with no headspace and placed on a rotating mixer (Labquake Tube Rotators, Thermo Scientific Inc.). At pre-determined sampling intervals, each sealed sacrificial tube reactor was centrifuged and a sample was taken.

Persulfate was measured using the KI colorimetric method25 with a Lambda-14 UV spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer Inc., Waltham, MA). Benzene and its oxidation products were analyzed on a Waters Alliance 2695 HPLC (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) equipped with a diode array detector and a Waters Symmetry-C18 column. Dissolved O2 concentrations were measured as the reaction proceeded using a YSI Model 58 oxygen probe (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH).

The unknown oxidation product was characterized by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), which was conducted using an Agilent 6520 Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (Q-TOF) instrument coupled to an Agilent 1200 HPLC. Details of the chromatography and its operating conditions were included as Text S3 in SI. The chemical structure of the unknown product was further characterized by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). To prepare the sample, solid-phase extraction (SPE) was used to separate the unknown compound from benzene and phenol and to concentrate the sample. Details of the SPE procedure were included as Text S4 in SI. This procedure was repeated several times to achieve an overall enrichment factor of 200. The final sample was subjected once more to the SPE procedure using D2O (pH 2) for washing of the cartridge and CH3CN-d3 for elution of the unknown. NMR analysis (1H-NMR, 1H,1H-COSY, 1H,1H-NOESY, 1H,13C-HSQC) was performed within 1 day to minimize degradation of the unknown compound. NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance 600 MHz instrument. To assess the formation of aldehyde oxidation products, experiments were carried out by mixing 10 mM bisulfite with the SPE-enriched unknown product. The formation of an aldehyde-bisulfite adduct was monitored by LC/MS using an Agilent 1200 series HPLC coupled with an Agilent 6410 Triple Quad LC/MS over 2 hours.

Results and Discussion

Persulfate activation

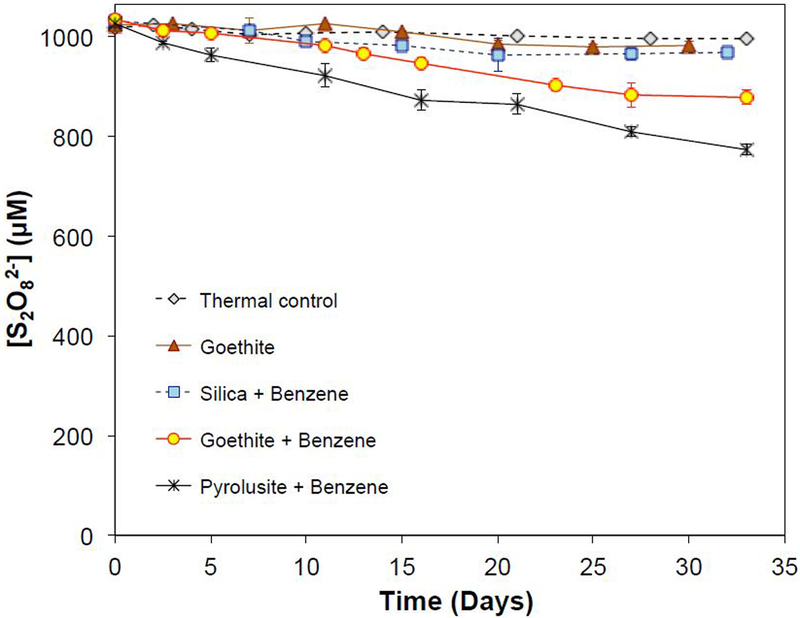

Persulfate concentrations decreased slowly over the course of the experiments (Figure 1). In thermal controls without minerals, the persulfate concentration decreased by less than 3% over 32 days, which was consistent with previously published data on thermal activation.5,26 Persulfate loss in the presence of goethite was slow, with approximately 5% of persulfate lost after 32 days. However, when 50 g/L of goethite and 1 mM of benzene were both present, 15% of the persulfate disappeared during the experiment. Similarly, 25% of the persulfate disappeared in the presence of pyrolusite and benzene after 32 days (Figure 1). The presence of silica had a negligible effect on persulfate loss rate when benzene was present compared to the thermal control.

Figure 1.

Changes of persulfate concentrations during mineral-catalyzed activation. Minerals were present at 50 g/L, and pH was buffered at 8.0 with 50 mM borate. When present, benzene was 1000 μM.

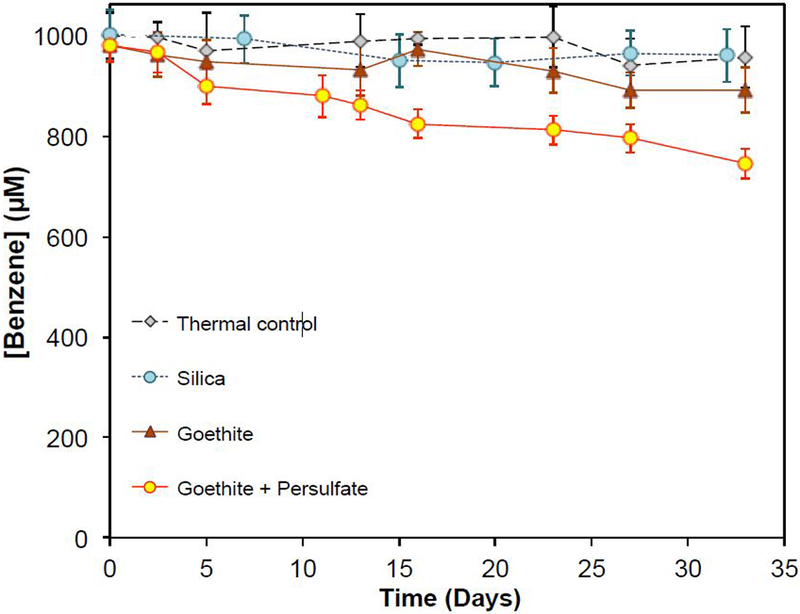

The decrease of persulfate concentration was accompanied by a loss of benzene (Figure 2). In thermal controls containing only benzene, the benzene concentration was constant over the 32-day experiment, indicating no volatilization of benzene from the sealed reactors. In goethite controls containing only goethite and benzene but no persulfate, complete recovery of adsorbed benzene from the goethite was achieved. Particle-associated benzene (i.e., the adsorbed fraction recovered by acetonitrile extraction) accounted for approximately 10-20% of the added benzene in the goethite control, and 5-10% in adsorption control experiments with other solids. Full recovery of adsorbed benzene by acetonitrile extraction was also achieved with ferrihydrite, pyrolusite and the aquifer solids (Figure S1). When 1 mM of persulfate was added in the presence of 50 g/L goethite, the benzene concentration decreased from 1000 μM to approximately 750 μM during the 32-day experiment (Figure 2). Similar results were observed for all other Fe(III)- and Mn(IV)-containing minerals and all aquifer solids except silica (Figure S2 to S10 in SI).

Figure 2.

Changes of total benzene concentration during persulfate activation in the presence of 50 g/L of goethite. pH was buffered at 8.0 with 50 mM borate. Benzene concentration includes aqueous and adsorbed benzene recovered by extraction. Initial persulfate was 1000 μM.

The acceleration of the rate of persulfate loss in the presence of benzene was most likely caused by a series of chain reactions that produced intermediate organic radicals. Experiments conducted in the absence of benzene were consistent with a mechanism in which persulfate was activated by Fe(III)- and Mn(IV)-containing minerals (denoted as ≡ Mn+) to generate SO4•− and S2O8•−:2,5

| (R1) |

| (R2) |

S2O8•−, the product of the reaction between Fe(III) and S2O82, can be involved in radical chain reactions that lead to the generation of additional SO4•− or other radicals,7,29 as summarized in Text S5 of SI. Other mechanisms of persulfate activation by Fe(III)- and Mn(IV)”Containing minerals also are possible. Additional research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of this process.

In the absence of benzene, SO4•− can react with persulfate to generate additional S2O8•− radicals:27-28

| (R3) |

SO4•− can also react with water or OH− to generate HO•:29-31

| (R4) |

| (R5) |

Under the condition studied here (i.e., [S2O82−]=1 mM; pH=8]), Reactions 3 and 4 each accounted for approximately half of the SO4•− loss and Reaction 5 was unimportant. In addition, three reactions can act as sinks for HO•:16,28,32

| (R6) |

| (R7) |

| (R8) |

Considering the low steady-state concentrations of HO• and SO4•− relative to S2O82−, Reaction 8 was the main sink for HO• Under these conditions, the steady-state concentration of SO4•− should have been approximately 20 times higher than that of HO• (see Text S6 for details).

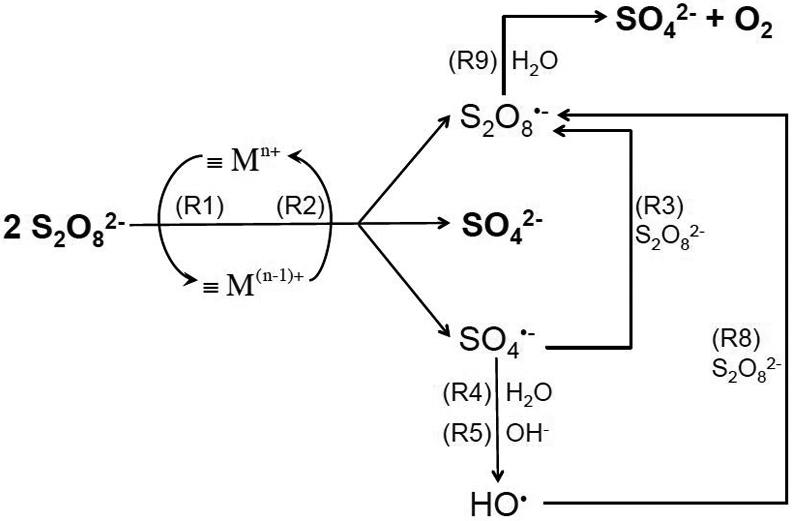

The overall pathways of radical generation in the absence of benzene are illustrated in Scheme 1. Experimental data indicate that SO42− and O2 were always the final products of S2O82− activation.5 In the absence of benzene, metal-catalyzed activation of S2O82− resulted in oxidation of water and production of sulfuric acid:30,33

| (R9) |

Scheme 1.

Illustration of major radical chain reactions when persulfate is activated by transition metal oxide in the absence of benzene or other contaminants. Sulfate and oxygen are the final products of persulfate activation.

The overall reaction can be described as follows:

| (R10) |

Benzene Oxidation Mechanism and Product Distribution

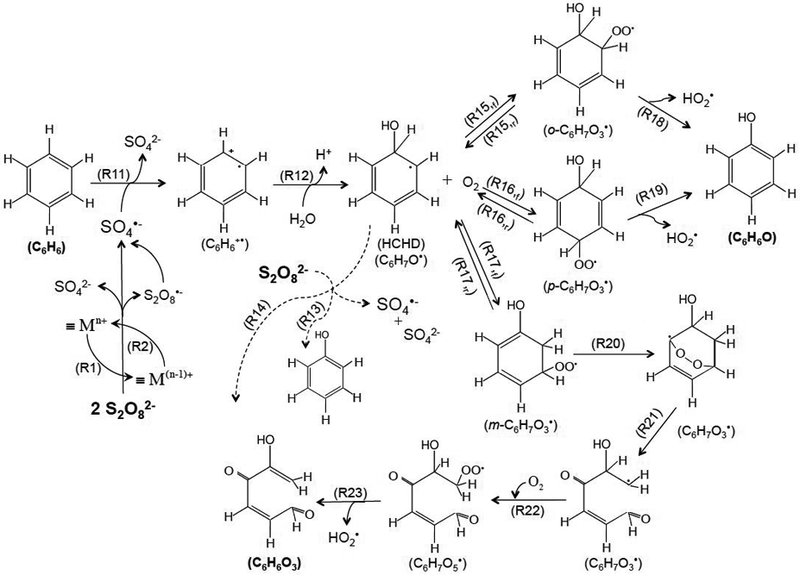

Although it is difficult to ascertain the mechanism through which benzene is oxidized in this complex system, it is possible to propose pathways that account for the observed products by considering previous studies involving benzene, SO4•− and other reactive species (Scheme 2). Other reaction pathways also could account for these products and should be considered in future research. When it reacts with benzene, SO4•− abstracts an electron from benzene to produce a short-lived cation radical (C6H6•+)7,13,34-35 (Reaction 11 in Scheme 2; k10=3×109 M−1s−1). Under conditions employed in this study (i.e., initial [benzene]=1 mM and [persulfate]=1 mM), k11[benzene] >> k3[S2O82−]), the majority of the SO4•− produced during S2O82− activation is consumed by benzene. C6H6•+ can react with H2O to form an intermediate, known as hydroxylcyclohexadienyl (HCHD) radical (i.e., C6H7O•, Reaction 12 in Scheme 2).34 HCHD radical was also observed during the oxidation of benzene by HO• via the OH-addition.15,36 Further consumption of S2O82− by its reaction with HCHD and other radical species may have been partially responsible for the faster loss of persulfate when benzene was present (Figure 1), as illustrated by Reactions 13 and 14 in Scheme 2. These reactions act as chain propagation reactions that accelerate the consumption of persulfate in the presence of benzene (Figure 1A).

Scheme 2.

Proposed radical chain reactions involving S2O82− activation, SO4•− generation, chain propagation with benzene and organic peroxy radical, and formation of phenol and the aldehyde product. The aldehyde shown is one possible product that is consistent with the NMR analysis. Dashed lines indicate pathways in oxygen-free conditions. The phenol and aldehyde are not the terminal oxidation products and can be further oxidized.

HCHD radical can react with O2 either in the ortho-, para- or meta-position to produce three isomers of organic peroxy radicals, i.e., o-C6H7O3• and m-C6H7O3• (Reactions 15-17 in Scheme 2),36 which subsequently eliminate hydroperoxy radical (HO2•) to produce phenol (Reactions 18-19 in Scheme 2).36-37 At circumneutral pH values, HO2• dissociates into O2•−, which undergoes bimolecular dismutation or metal-catalyzed dismutation to produce H2O2.5,38 Only a small fraction of H2O2 formed in this process (i.e., < 2%) produced HO• through Fenton-like reactions at iron and manganese-containing solid surfaces. Most of H2O2 is converted to H2O and O2 through non-radical pathways.24,39,40 Therefore, H2O2 produced through dismutation had a negligible effect on benzene degradation or persulfate activation.

The mechanism described above indicates that phenol should be the primary product of benzene oxidation.36-37,41 After phenol was produced, further reaction with oxidants could result in the formation of poly-hydroxylated compounds, followed by the eventual production of ring-cleavage products.3,37-42 However, under conditions employed in these experiments (i.e., conversion of less than 35% of the benzene), a significant production of these later products was not expected. Oxygen addition at the ortho- and para-position (Reaction 15) was the mechanism36 through which phenol was formed (see Text S7 in the SI).

Simultaneous quantification of benzene loss and phenol production indicated that phenol accounted for approximately 30% to 60% of the benzene loss under air-saturated conditions (Table 1). Loss of phenol due to reaction with HO• or SO4•− after it was formed could not account for the discrepancy between benzene loss and phenol formation (Text S8 in SI). Inspection of the chromatogram of samples obtained after persulfate was activated by minerals in the presence of benzene indicated the presence of an unknown product in addition to phenol (Figure S11-A). The UV spectrum of this product exhibited absorption maxima at 276 and 361 nm (Figure S11-B), which is similar to the reported spectra of a six-carbon aldehyde compound (i.e., hydroxylmucondialdehyde) detected when benzene was oxidized by HO• produced by continuous radiolysis in the presence of O2 36,41,43-44

Table 1.

Production of phenol as a primary oxidation product from benzene oxidation by persulfate activation and the impact of dissolved O2.

| Solids | Product Distribution | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [O2]=3 μM | [O2]=250 μM | [O2]=410 μM | ||

| Silica | 24% ± 2% | 45% ± 4% | – | |

| Goethite | 18% ± 8% | 30% ± 11% | 62% ± 11% | |

| Minerals | Ferrihydrite | 32% ± 13% | 57% ± 16% | – |

| Pyrolousite | 27% ± 11% | 34% ± 9% | – | |

| Nontronite | – | 38% ± 13% | ||

| Clays | ||||

| Montmorillonite | – | 28% ± 2% | – | |

| AWBPH | – | 73% ± 7% | – | |

| AFTCS | – | 100% ± 5% | – | |

|

Aquifer Solids | ||||

| CAROL | – | 73% ± 4% | ||

| CADOU | – | 15% ± 6% | – | |

| AMTAL | – | 25% ± 2% | – | |

Analysis of the unknown ring-cleavage product by Q-TOF LC/MS revealed an exact mass of m/z 125.0246, corresponding to the sum formula C6H5O3 (Figure S11-C). MS/MS experiments further revealed the cleavage of CO (fragments: m/z of 97.0296, C5H5O2; m/z of 69.0250, C4H5O), indicating the presence of two −C=O moieties.45 Increasing the collision energy yielded an additional fragment at m/z 79.0180 (C5H3O), suggesting cleavage of H2O from fragment C5H5O2. Q-TOF analysis suggests the presence of two −C=O functional groups with one having a hydroxyl group in the α-position.

1H-NMR results confirmed the presence of an aldehyde group as evidenced by the presence of a characteristic shift at 9.32 ppm (Figure S12). Results from the NOESY experiments further indicated coupling of the aldehyde proton to two protons with chemical shifts of 7.44 and 6.93 ppm, thus suggesting the presence of an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde moiety.46 The identity of the remaining part of the molecule could not be further elucidated as the results were inconclusive. Although the signal at 8.63 ppm in the 1H-NMR spectrum might suggest the presence of an additional aldehyde moiety,46 as indicated by high-resolution MS analysis, integration of the signals in the 1H-NMR spectrum revealed the presence of two protons for chemical shift 8.63 ppm, thus excluding an aldehyde moiety. Rather, the results suggested a terminal sp2 carbon was adjacent to an electron withdrawing environment, possibly a hydroxylated carbon bonded to a carbonyl, which might explain the untypically far downfield shift of 8.63 ppm and the weak coupling with the enal fragment of the molecule seen in the NOESY spectrum (Figure S12).

The presence of a single aldehyde functional group was further supported by the reaction of the unknown compound with bisulfite (10 mM), which yielded a product with m/z of 207 (Figure S13). This observation was consistent with previous reports on the detection of aldehyde.47–49

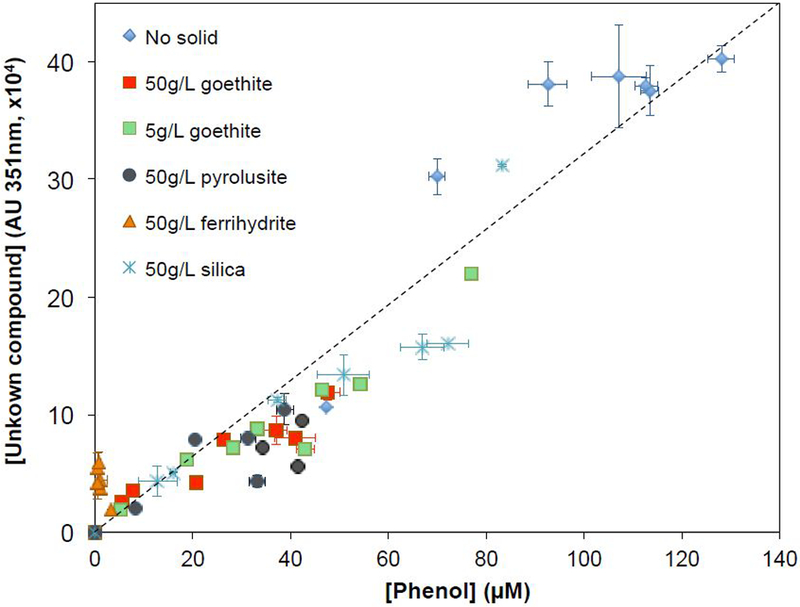

The peak area of the aldehyde product, as determined by HPLC-UV analysis at 361 nm, was always proportional to the concentration of phenol produced (Figure 3). This behavior indicated that this compound was not an oxidation product of phenol. Furthermore, the unknown compound was not the product of direct reaction between phenol and persulfate, because oxidation of phenol by excess persulfate was too slow and the small loss of phenol that occurred did not result in the formation of the unknown (data not shown). Therefore, it is likely that the aldehyde-like compound was a primary product of the reaction of SO4•− and benzene. Additional activated persulfate transformation experiments with benzoquinone, hydroquinone, catechol, and 1,2,4-benzenetriol did not produce the same benzene transformation product, indicating that none of these compounds are intermediates in the formation of the ring-cleavage product from the oxidation of benzene.

Figure 3.

Relationship between phenol concentration and the UV peak intensity of the unknown oxidation product. Samples were collected at different reaction times during benzene oxidation in the presence of persulfate and different concentrations of solids. Initial [benzene]=1000 μM, initial [S2O82−]=1000 μM, and pH was buffered at 8.0 with 50 mM borate.

Previous researchers have described alternative pathways through which aldehyde-like ring cleavage products can be produced directly from HO• attack on benzene.36,41,50,51 One possibility is the formation of a meta-position isomer of C6H7O3• produced from the HCHD radical and its rearrangement to an intramolecular endoperoxide with a dioxygen bond (Reaction 20 in Scheme 2), which subsequently decomposes to a carbon-centered aldehyde radical (Reaction 21).41-44,50 The aldehyde radical can react with O2 and produce an aldehyde-like peroxy radical (Reaction 22), followed by the elimination of HO2• to produce a six-carbon aldehyde product (Reaction 23).41 The proposed aldehyde chemical structure shown in Scheme 2 is one possible product that is consistent with the NMR analysis.

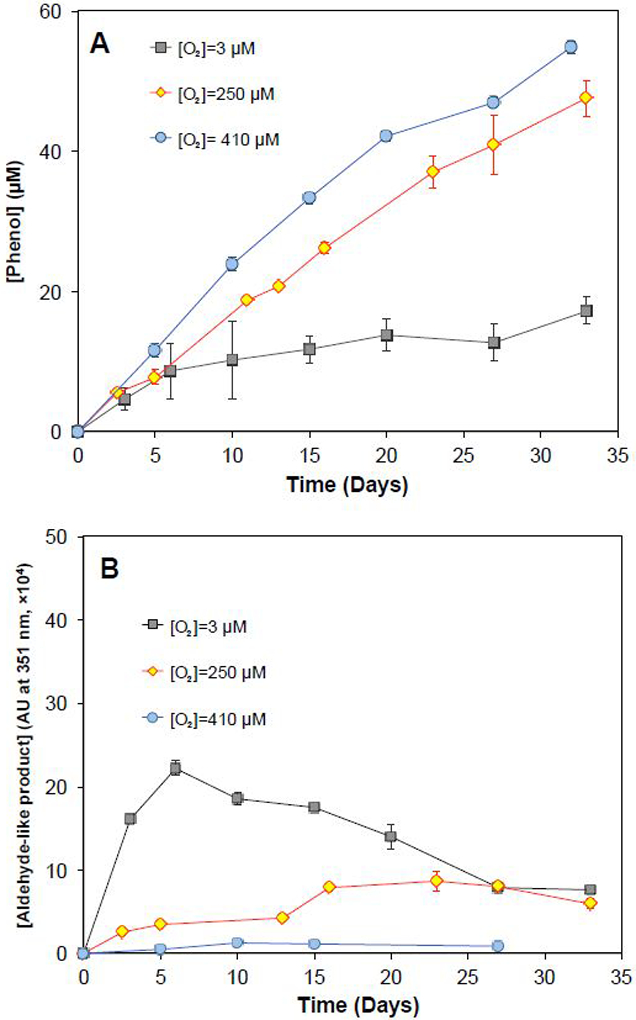

The distribution of products was affected by the dissolved O2 concentration. Higher concentrations of O2 favored phenol formation (Figure 4A and Table 1). The N2-purged solutions (i.e., [O2] = 3 μM) resulted in the formation of phenol at concentrations that were approximately 30% of those observed under air-saturated conditions (i.e., [O2] = 250 μM), or 10% of those observed under O2-supersaturated conditions (i.e., [O2] = 410 μM). In the absence of O2, it is possible that HCHD radical was oxidized by S2O82− to generate phenol (Reaction 13) and the ring-cleavage product (Reaction 14) at different ratios than those observed in the presence of O2.34,52 Such a process would serve as a chain propagation reaction, producing one mole of SO4• for every mole of S2O82− decomposed (Reactions 13-14 in Scheme 2). In the goethite-activated persulfate system, the concentration of the unknown compound was approximately 10 times higher in the N2-purged solution ([O2]=3 μM) than that in O2-supersaturated solution ([O2]=410 μM) after 5 days of reaction (Figure 4B). A similar trend was observed in ferrihydrite and pyrolusite activated persulfate system (Figure S14). The decrease of the concentration of aldehyde-like product after 10 days of reaction in the N2-purged solution might due to the acceleration of reaction when dissolved oxygen was accumulated from persulfate activation.

Figure 4.

Impacts of dissolved O2 concentration on oxidation product distribution in the presence of persulfate and solids. (A) Phenol formation; (B) aldehyde-like product. Goethite=50 g/L, Initial [benzene]=1000 μM, initial [S2O82−]=1000 μM, and pH was buffered at 8.0 with 50 mM borate.

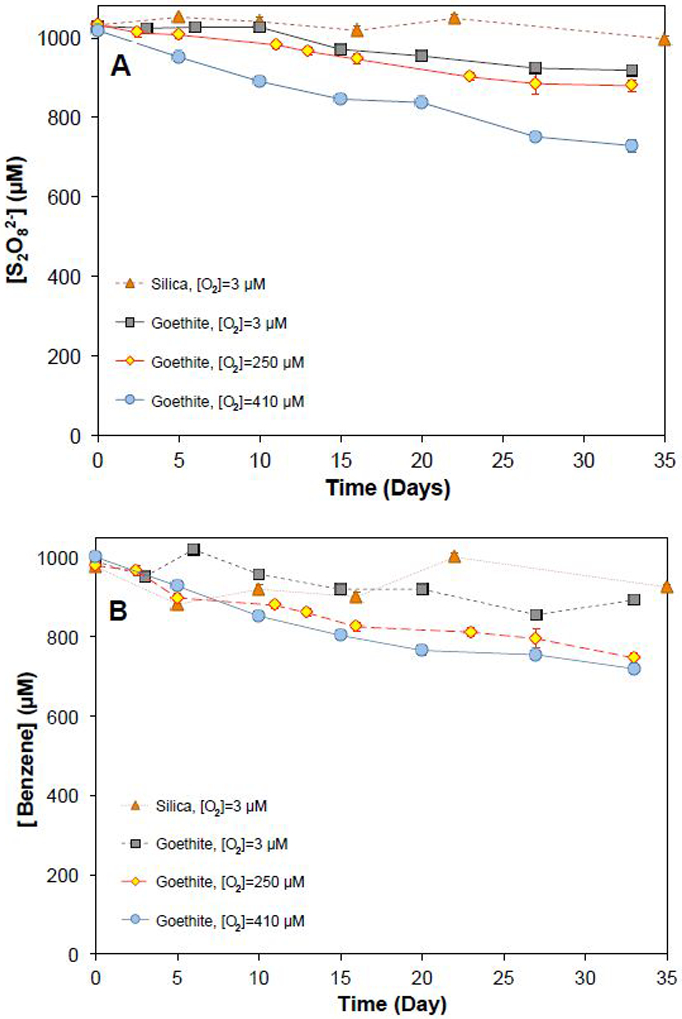

The rate of persulfate activation also decreased at lower dissolved O2 concentrations when benzene was present (Figure 5A). In the presence of 1 mM benzene and 50 g/L goethite, the amount of persulfate activated decreased from 300 μM to less than 100 μM after 32 days when the initial dissolved O2 concentration decreased from 410 μM to 3 μM. The same trend was observed for benzene transformation (Figure 5B). These data suggest that as the O2 concentration decreased, the radical chain reactions slowed down. The results indicated that benzene oxidation and persulfate activation in the absence of oxygen proceeded through different chain reactions (e.g., Reactions 13-14 in Scheme 2). While it is unlikely that ISCO treatment of groundwater would be completely free of dissolved oxygen, these data strongly suggest that radical chain reactions can be affected by oxygen concentration. The mechanism through which this occurred requires future investigation.

Figure 5.

Impacts of dissolved oxygen concentration on the rate of (A) persulfate activation and (B) benzene degradation in the presence of persulfate and solids. Goethite=50 g/L, initial [benzene]=1000 μM, initial [S2O82−]=1000 μM, and pH was buffered at 8.0 with 50 mM borate.

The aldehyde-like compound also was detected when H2O2 was activated by minerals and aquifer solids (i.e., the Fenton-like reaction system). Because the amount of benzene that disappeared in presence of H2O2 was much smaller than that observed when S2O82− served as the oxidant (the former was only approximately 10% of the latter), the relative ratio of aldehyde-like compound to phenol concentration was used to compare the product distribution in the two systems. Results indicated that the aldehyde-like compound production decreased dramatically when H2O2 was employed as the oxidant compared to when S2O82− was employed as the oxidant (Table S1). For example, in the presence of 50 g/L pyrolusite or ferrihydrite and 1 mM H2O2, the aldehyde-like compound was not detected, while a small amount of the product was observed when goethite was used for H2O2 activation. The difference in product distribution from benzene oxidation between S2O82− and H2O2 activation systems suggests that HO• and SO4•− propagate different radical chain reaction pathways.

Oxidant yield in the persulfate system

Because benzene is the major sink for SO4•− under all conditions (Reaction 11 in Scheme 2), the disappearance of benzene can be used to identify pathways through which S2O82− decomposes without producing SO4•−. The stoichiometric efficiency is defined as the number of moles of benzene oxidized for every mole of persulfate activated:

| (E1) |

Under air-saturated conditions ([O2]=250 μM), the stoichiometric efficiency of persulfate activation by different solids ranged from 26% to 145% (Table 2). Most minerals exhibited efficiencies between 83% and 145%. Similar results were observed in synthetic groundwater matrix (Table S2). If S2O8•− reacts to produce two additional sulfate radicals (SI Text 5) the maximum stoichiometric efficiency of the system would be 150%. If S2O8•− does not generate additional sulfate radicals, the maximum stoichiometric efficiency could be as low as 50%. Additional research is needed to assess the formation and fate of S2O8•0 and other species in this system.

Table 2.

Stoichiometric efficiency (η) in metal-catalyzed system with S2O82− and H2O2, respectively.

|

ηH2O2 |

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [O2]=250 μM | [O2]=3 μM | [O2]=250 μM | [O2]=410 μM | ||

| Silica | 0.02% ± 0.5% | 45% ± 18% | 135% ± 71% | – | |

| Goethite | 1.02% ± 0.06% | 103% ± 18% | 145% ± 49% | 143% ± 28% | |

| Minerals | Ferrihydrite | 0.01% ± 0.001% | 29% ± 11% | 26% ± 8% | – |

| Pyrolousite | 0.30% ± 0.02% | 28% ± 12% | 64% ± 11% | – | |

| Nontronite | 0.22% ± 0.02% | – | 116% ± 17% | – | |

| Clays | |||||

| Montmorillonite | 0.12% ± 0.01% | – | 138% ± 23% | – | |

| AWBPH | 0.03% ± 0.01% | – | 83% ± 25% | – | |

| AFTCS | 0.02% ± 0.01% | – | 76% ± 7% | – | |

| Aquifer Solids | CAROL | 0.18% ± 0.04% | – | 127% ± 45% | – |

| CADOU | 0.04% ± 0.01% | – | 131% ± 31% | – | |

| AMTAL | 0.02% ± 0.01% | – | 106% ± 6% | – | |

There are three possible pathways through which the HCHD radical could be oxidized. First, S2O82− can serve as the oxidant for the HCHD radical (Reactions 13-14). Previous studies found S2O82− reacts quickly with a variety of carbon-centered radicals, including aromatic, aliphatic and semiquinone anion radicals, to generate oxidized products and SO4•−.2,22,34,52-53 This would lower the stoichiometric efficiency because it only produces one mole of SO4•− for each mole of S2O82− that decomposes.

Second, the types of mineral surfaces and their surface areas could affect the fate of SO4• The oxidant yields for pyrolusite and ferrihydrite were considerably lower (i.e., 26% and 64%, respectively) than other minerals and aquifer solids. Pyrolusite has large structural Mn(IV) content that is known to favor non-radical pathway for H2O2 decomposition.24 Ferrihydrite has a very large surface area (two orders of magnitude larger than other minerals)5 that could favor SO4•− scavenging reactions:

| (R24) |

Third, the HCHD radical is quickly oxidized by O2 (k=1.5×108 M−1s−1).36–37 Higher dissolved O2 concentrations should have decreased the importance of the reaction between HCHD radical and S2O82−, resulting in an increase of efficiency. The impact of dissolved O2 on the stoichiometric efficiency was significant (Table 2). In general, the yield was similar in air- and oxygen-saturation conditions ([O2]=250 and 410 μM), but dropped under N2-purged conditions ([O2]=3 μM). For example, the yield dropped by 40% for goethite and pyrolusite when O2 concentration decreased from 410 μM to 3 μM.

Although the stoichiometric efficiency in the S2O82− system did not reach the theoretical maximum value, it was always one to two orders of magnitude higher than that observed in the H2O2 system (Table 2). This suggest that ISCO systems that employ S2O82• require significantly smaller amounts of oxidant relative to those that use H2O2. The inherent inefficiency of H2O2-based ISCO is attributed to reactions that result in loss of the peroxide without production of HO•. Such mechanisms appear to be much less important in the S2O82− system. The inherent disadvantage of the persulfate system – slower activation kinetics than the H2O2 system – could be beneficial for remediation because it allows the oxidant to migrate further from the injection point.

The detection of an aldehyde-like product from metal-oxide catalyzed persulfate and peroxide activation suggests a need for caution in the application of ISCO, because aldehyde degradation products such as muconaldehyde have been shown to be responsible for observed benzene toxicity in vivo.54,55 The potential for generating toxic transformation products during oxidative remediation is already recognized as problematic in drinking water treatment, but it has received less attention in ISCO research. Further studies are needed to understand the formation of the transformation products in ISCO-based remediation systems, to characterize their toxicity, and to assess the potential of these compounds to undergo biotransformation in the subsurface.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This research was partially supported by grants to D.L.S. from the U.S. National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Superfund Research Program (Grant P42 ES004705) at UC Berkeley, to H.L. from the UC Riverside Faculty Initial Complement Research Fund, and to W.L. from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. We thank Dan Borchardt at UC Riverside and Christopher Hill at UC Berkeley for assistance on NMR, and Urs Jans at the City College of New York and Manfred Wagner at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Germany for participation in the project.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Section

Additional description of iron and manganese mineral preparation, interpretations of radical chain reactions, two tables on experimental materials and fifteen figures on the rate of persulfate activation and product formation in different conditions are provided in the Supporting Information Section.

References

- 1.Siegrist RL; Crimi M; Simpkin TJ In situ chemical oxidation: technology, description and status In situ chemical oxidation for groundwater remediation. Springer Media, LLC: New York City, NY, 2011; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sra KS; Thomson NR; Barker JF Persistence of persulfate in uncontaminated aquifer materials. Environ. Sci. Technol 2010, 44, 3098–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsitonaki A; Petri B; Crimi M; Mosbaek H; Siegrist RL; Bjerg PL In Situ Chemical Oxidation of Contaminated Soil and Groundwater Using Persulfate: A Review. Crit. Rev. in Environ. Sci. and Technol 2010, 40, 55–91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmad M; Teel AL; Watts RJ Persulfate activation by subsurface minerals. J. Contam. Hydrol 2010, 115, 34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu H; Bruton TA; Doyle FM; Sedlak DL In situ chemical oxidation of contaminanted groundwater by persulfate: activation by Fe(III)- and Mn(IV)-containing oxides and aquifer materials. Environ. Sci. Technol 2014, 48, 10330–10336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antoniou MG; De La Cruz AA; Dionysiou DD Intermediates and reaction pathways from the degradation of microcystin-LR with sulfate radicals. Environ. Sci. Technol 2010, 37, 7238–7244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anipsitakis GP; Dionysiou DD; Gonzalez MA Cobalt-mediated activation of peroxymonosulfate and sulfate radical attack on phenolic compounds. Implications of chloride ions. Environ. Sci. Technol 2006, 40, 1000–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antoniou MG; De La Cruz AA; Dionysiou DD Degradation of microcystin-LR using sulfate radicals generated through photolysis, thermolysis and e− transfer mechanisms. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 2010, 96, 290–298. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan YH; Ma J; Ren YM; Liu YL; Xiao JY; Lin LQ; Zhang C Efficient degradation of atrazine by magnetic porous copper ferrite catalyzed peroxymonosulfate oxidation via the formation of hydroxyl and sulfate radicals. Water. Res 2013, 47, 5431–5438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ying Y; Pignatello JJ; Ma J; Mitch WA Comparison of halide impacts on the efficiency of contaminant degradation by sulfate and hydroxyl radical-based advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). Environ. Sci. Technol 2014, 48, 2344–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drzewicz P; Perez-Estrada L; Alpatova A; Martin JW; El-Din MG Impact of peroxydisulfate in the presence of zero valent iron on the oxidation of cyclohexanoic acid and naphthenic acids from oil sands process-affected water intermediates and reaction pathways from the degradation of microcystin-LR with sulfate radicals. Environ. Sci. Technol 2012, 46, 8984–8991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan S; Liao P; Alshawabkeh AN Electrolytic manipulation of persulfate reactivity by iron electrodes for trichloroethylene degradation in groundwater. Environ. Sci. Technol 2014, 48, 656–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huie RE; Neta P Chemical behavior of SO3•− and SO5•− radicals in aqueous solutions. J. Phys. Chem 1984, 88, 5665–5669. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wardman P Reduction potentials of one-electron couples involving free radicals in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1989, 18, 1637–1657. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neta P; Huie RE; Ross AB Rate constants for reactions of inorganic radicals in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1988, 17, 1027–1284. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buxton GV; Greenstock CL; Helman WP; Ross AB Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (•OH/•O−) in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1988, 17, 513–886. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houtz EF; Sedlak DL Oxidative conversion as a means of detecting precursors to perfluoroalkyl acids in urban runoff. Environ. Sci. Technol 2012, 46, 9342–9349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furman OS; Teel AL; Watts RJ Mechanism of base activation of persulfate. Environ. Sci. Technol 2010, 44, 6423–6428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guan YH; Ma J; Li XC; Fang JY; Chen LW Influence of pH on the formation of sulfate and hydroxyl radicals in the UV/peroxymonosulfate system. Environ. Sci. Technol 2011, 45, 9308–9314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lutze HV; Kerlin N; Schmidt TC Sulfate radical-based water treatment in presence of chloride: Formation of chlorate, inter-conversion of sulfate radicals into hydroxyl radicals and influence of bicarbonate. Water. Res 2015, 72, 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang R; Sun P; Boyer TH; Zhao L; Huang C Degradation of pharmaceuticals and metabolite in synthetic human urine by UV, UV/H2O2, and UV/PDS. Environ. Sci. Technol 2015, 49, 3056–3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang G; Gao J; Dionysiou DD; Liu C; Zhou D Activation of persulfate by quinones: free radical reactions and implication for the degradation of PCBs. Environ. Sci. Technol 2013, 47, 4605–4611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petigara BR; Blough NV; Mignerey AC Mechanisms of hydrogen peroxide decomposition in soils. Environ. Sci. Technol 2002, 36, 639–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pham AL; Doyle FM; Sedlak DL Kinetics and efficiency of H2O2 activation by iron-containing minerals and aquifer materials. Water Res 2012, 46, 6454–6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang C; Huang CF; Mohanty N; Kurakalva RM A rapid spectrophotometric determination of persulfate anion in ISCO. Chemosphere. 2008, 73, 1540–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson RL; Tratnyek PG; Johnson RO Persulfate persistence under thermal activation conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol 2008, 42, 9350–9356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu XY; Bao ZC; Barker JR Free radical reactions involving Cl•, Cl2•−, and SO4•− in the 248 nm photolysis of aqueous solutions containing S2O82− and Cl−. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das TN Reactivity and role of SO5•− radical in aqueous medium chain oxidation of sulfite to sulfate and atmospheric sulfuric acid generation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 9142–9155. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolthoff IM; Miller IK The chemistry of persulfate. I. The kinetics and mechanism of the decomposition of the persulfate ion in aqueous medium. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1951, 73, 3055–3059. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrmann H; Reese A; Zellner R Time-resolved UV/VIS diode-array absorption spectroscopy of SOx− (x=3, 4, 5) radical anions in aqueous solution. J. Mol. Struct 1995, 348, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peyton GR The free-radical chemistry of persulfate-based total organic carbon analyzer. Mar. Chem 1993, 41, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang T; Zhu H; Croué JP Production of sulfate radical from peroxymonosulfate induced by a magnetically separable CuFe2O4 spinel in water: efficiency, stability and mechanism. Environ. Sci. Technol 2013, 47, 2784–2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neta P; Huie RE; Ross AB Rate constants for reactions of inorganic radicals in aqueous solution. J Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1988, 17, 1027–1284. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norman ROC; Storey PM; West PR Electron spin resonance studies. Part XXV. Reactions of the sulphate radical anion with organic compounds. J. Chem. Soc. B 1970, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aravindakumar CT; Schuchmann MN; Rao BSM; Von Sonntag J; Von Sonntag C The reactions of cytidine and 2′-deoxycytidine with SO4•− radical revisited. Pulse radiolysis and product studies. Org. Biomol. Chem 2003, 1, 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan XM; Schuchmann MN; von Sonntag C Oxidation of benzene by the OH radical: a product and pulse radiolysis study in oxygenated aqueous solution. J. Chem. Soc Perkin Trans. II. 1993, 3, 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Von Sonntag C; Dowideit P; Fang X; Mertens R; Pan X; Schuchmann MN; Schuchmann H The fate of peroxyl radicals in aqueous solution. Wat. Sci. Tech 1997, 35, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sedlak DL; Hoigne J The role of copper and oxalate in the redox cycling of iron in atmospheric waters. Atmosph. Env. Part A. Gen. Top 1993, 27, 2173–2185. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwan W; Voelker BM Rates of hydroxyl radical generation and organic compound oxidation in mineral-catalyzed Fenton-like systems. Environ. Sci. Technol 2003, 37, 3270–3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keenan CK; Sedlak DL Factors affecting the yield of oxidant from the reaction of nanoparticulate zero-valent iron and oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol 2008, 42, 1262–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srinivasan TKK; Balakrishman I; Reddy MP On the nature of the products of γ-radiolysis of aerated aqueous solution of benzene. J. Phys. Chem 1969, 73, 2071–2073. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lemaire J; Croze V; Maier J; Simonnot M Is it possible to remediate a BTEX contaminated chalky aquifer by in situ chemical oxidation? Chemosphere. 2011, 84, 1181–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balakrishman I; Reddy MP The effect of temperature on the γ-radiolysis of aqueous solutions. J. Phys. Chem 1972, 76, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacob N; Balakrishnan I; Reddy MP Characterization of the hydroxyl radical in some photochemical reactions. J. Phys. Chem 1977, 81, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levsen K; Schiebel H; Terlouw JK; Jobst KJ; Elend M; Preiß A; Thiele H; Ingendoh, A. Even-electron ions: a systematic study of the neutral species lost in the dissociation of quasi-molecular ions. J. Mass Spectrometry 2007, 42, 1024–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bertz SH; Dabbagh G Chemistry under physiological conditions. Part 8. NMR spectroscopy of malondialdehyde. J. Org. Chem 1990, 55, 5161–5165. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donnally LH Quantitative determination of formaldehyde and benzaldehyde and their bisulfite addition products. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry-Analytical Edition. 1933, 5, 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ragan JA; Ende DJA; Brenek SJ; Eisenbeis SA; Singer RA; Tickner DL; Teixeira JJ; Vanderplas BC; Weston N Safe execution of a large-scale ozonolysis: Preparation of the bisulfite adduct of 2-hydroxyindan-2-carboxaldehyde and its utility in a reductive amination. Organic Process Research & Development. 2003, 7, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kissane MG; Frank SA; Rener GA; Ley CP; Alt CA; Stroud PA; Vaid RK; Boini SK; McKee LA; Vicenzi JT; Stephenson GA Counterion effects in the preparation of aldehyde-bisulfite adducts. Tetrahedron Letters. 2013, 54, 6587–6591. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan XM; Schuchmann MN; von Sonntag C Hydroxyl-radical-induced oxidation of cyclohexa-1,4-diene by O2 in aqueous solution. A pulse radiolysis and product study. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. II. 1993, 6, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fang X; Pan X; Rahmann A; Schuchmann H; von Sonntag C Reversibility in the reaction of cyclohexadienyl radicals with oxygen in aqueous solution. Chem. Eur. J 1995, 1, 423–429. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beylerian NM; Khachatrian AG The mechanism of the oxidation of alcohols and aldehydes with peroxydisulphate ion. J. Chem. Sci. Perkin Tran. II 1984, 12, 1937–1941. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lau TK; Chu W; Graham NJD The aqueous degradation of butylated hydroxyanisole by UV/S2O82−: study of reaction mechanisms via dimerization and mineralization. Environ. Sci. Technol 2007, 41, 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Latriano L; Goldstein SD; Witz G Formation of muconaldehyde, an open-ring metabolite of benzene, in mouse liver microsomes: an additional pathway for toxic metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 8356–8360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Short DM; Lyon R; Watson DG; Barski OA; McGarvie G; Ellis EA Metabolism of trans, trans-muconaldehyde, a cytotoxic metabolite of benzene, in mouse liver by alcohol dehydrogenase Adh1 and aldehyde reductase AKR1A4. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2006, 210, 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.