Key Points

Question

What is the Legionnaires disease burden in the US Department of Veterans Affairs medical facilities, a health care system that has prioritized Legionnaires disease prevention with policy?

Findings

In this cohort study, the number of Legionnaires disease cases was low (n = 491) and 91% of cases had no VA exposure or only outpatient VA exposure. Total rates of Legionnaires disease significantly increased from 2014 to 2016, but rates in cases with overnight health care system exposure significantly decreased.

Meaning

Although total Legionnaires disease rates increased, health care system–associated (overnight stay) rates decreased significantly, suggesting that prevention efforts may have contributed to improved patient safety in these settings.

Abstract

Importance

Legionnaires disease (LD) incidence is increasing in the United States. Health care facilities are a high-risk setting for transmission of Legionella bacteria from building water systems to occupants. However, the contribution of LD in health care facilities to national LD rates is not well characterized.

Objectives

To determine the burden of LD in US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patients and to assess the amount of LD with VA exposure.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study of reported LD data in VA medical facilities in a national VA LD surveillance system from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016. The study population included total veteran enrollees and enrollees who used the VA health care system.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was assessment of annual LD rates, categorized by VA and non-VA exposure. Legionnaires disease rates for cases with VA exposure were determined on both population and exposure potential levels. Rates by VA exposure potential were calculated using inpatient bed days of care, long-term care resident days, or outpatient encounters. In addition, types and amounts of LD diagnostic testing were calculated. Case and testing data were analyzed nationally and regionally.

Results

There were 491 LD cases in the case report surveillance system from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016. Most cases (447 [91%]) had no VA exposure or only outpatient VA exposure. The remaining 44 cases had VA exposure from overnight stays. Total LD rates from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016, increased for all VA enrollees (from 1.5 to 2.0 per 100 000 enrollees; P = .04) and for users of VA health care (2.3 to 3.0 per 100 000 enrollees; P = .04). The LD rate for the subset who had no VA exposure also increased (0.90 to 1.47 per 100 000 enrollees; P < .001). In contrast, the LD rate for patients with VA overnight stay decreased on a population level (5.0 to 2.3 per 100 000 enrollees; P < .001) and an exposure level (0.31 to 0.15 per 100 000 enrollees; P < .001). Regionally, the eastern United States had the highest LD rates. The urine antigen test was the most used LD diagnostic method; 49 805 tests were performed in 2015-2016 with 335 positive results (0.67%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Data in the VA LD databases showed an increase in overall LD rates over the 3 years, driven by increases in rates of non-VA LD. Inpatient VA-associated LD rates decreased, suggesting that the VA’s LD prevention efforts have contributed to improved patient safety.

This infection epidemiology study describes the number of reports of Legionnaires disease in VA facilities between 2014 and 2016 and the proportion of cases associated with VA health care facility vs community exposure.

Introduction

Legionnaires disease (LD) is an acute pneumonia caused by Legionella species, primarily L pneumophila serogroup 1 in the United States.1 The bacteria are naturally present in water,1 and infection is associated with exposure from engineered water systems that allow Legionella to proliferate. Several prominent outbreaks have increased attention on LD in the United States recently.2,3,4,5,6 Legionellosis (including LD and the milder Pontiac fever) is reportable to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 6079 cases were reported in 2015.7 Rates of reported legionellosis have been increasing for decades.8,9,10 However, the incidence of LD in the United States and the sources of infection are not well characterized. Underdiagnosis, underreporting, and unknown follow-up of sporadic cases complicate the ability to ascertain a true national picture. The result is an underappreciation for the burden of LD in the United States and missed opportunities for prevention. This is particularly important for health care settings, which have occupants at risk for Legionella infection11 and for which numerous outbreaks have been described.2 The CDC recently reported health care–associated (HCA) LD surveillance data from 21 jurisdictions.11 Of the 2809 confirmed LD cases reported in 2015, 3% were classified as definite HCA LD and 17% were classified as possible HCA LD, substantiating health care as a source for exposure. However, national data over multiple years were not reported, categorization of possible HCA LD by inpatient or outpatient exposure was not stated, and data completeness was not known. Furthermore, many hospitals do not perform whole-house surveillance for HCA pneumonia, and guidelines12,13 do not specifically indicate Legionella diagnostic testing in many patients with HCA pneumonia when it is identified. Therefore, the general burden of HCA LD in the United States may not be well represented by passive surveillance systems.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States, with more than 1200 sites of care, serving about 6 million veterans annually.14 In federal fiscal year (FY) 2016, 91% of veterans using VA benefits were male with a median age of 64 years15 and with higher morbidity than in the rest of the United States,16,17 which are population factors with higher LD risk.1,18 Accordingly, VHA has a Legionella prevention policy required at medical facilities to limit Legionella growth in water distribution systems and validation of effectiveness using both environmental and clinical surveillance.19 The policy promotes LD testing of symptomatic patients and requires heightened awareness for LD when facility water has tested positive for Legionella. Concomitant to publication of the policy in 2014, the VHA Central Office implemented a national standardized LD reporting system. This article presents an analysis of data in the system from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016, and with no such comparable surveillance database in the United States, provides a unique insight into the rate of LD—both community-associated and HCA—on a national scale.

Methods

Setting

Veterans Affairs medical facilities offer a range of services to enrolled veterans across the country and US territories.20 During this analysis, VA medical facilities were administratively arranged into 142 health care systems (HCSs), with 170 medical centers20 and 132 long-term care sites.21

Dissemination of findings that result from review of national VHA operational data sets beyond programmatic needs has been reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the University of Cincinnati, the institutional review board of record for the Cincinnati VA Medical Center. In this retrospective review of data in an operational surveillance system, there was no greater than minimal risk to patients included in the system, the rights and welfare of patients in the system were not adversely affected, and patient medical records were not altered as a result of this work; these criteria determined that patient consent was not required. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Beginning October 15, 2014, LD data were reported into 2 databases prospectively by personnel at each VA HCS, centrally maintained at the VHA Inpatient Evaluation Center (IPEC).22 Legionnaires disease data reporting was required.

Legionella Case Report Module

The Legionella Case Report Module database is used for ad hoc reporting of laboratory-confirmed, community- and VA-associated cases (eAppendix 1 and eTable 1 in the Supplement). Determination of case reporting information provided to this central surveillance system is made at the local facility level. In addition to prospective reporting, retrospective reporting of cases was also required from October 1, 2013, to October 14, 2014.

Legionnaires disease case reports included whether there was exposure to a VA building within the 10 days prior to LD symptom onset. Classification of cases as definitely or possibly associated with VA exposure followed surveillance definitions on the 2014 CDC legionellosis case report form,23 with the additional detail of the type of exposure (inpatient, outpatient, or both) if the case was possibly associated with VA. For this article, we assessed VA exposure using the current23 and previous24 CDC definitions for HCA legionellosis to determine the association of outpatient exposure, a new criterion for the current definitions, with attribution of cases to health care. Definite VA-associated LD cases reported to the database received extensive review and often follow-up with the facility to confirm the diagnosis and classification, and to provide consultative assistance for prevention.

Legionella Clinical Information Module

The Legionella Clinical Information Module database collects monthly reporting of aggregate LD diagnostic information at VA medical facilities, including the number of various LD diagnostic tests performed (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Retrospective reporting of data prior to October 1, 2014, was not required.

Case Reporting Validation

Data entered into both IPEC databases for each HCS were centrally reviewed monthly to determine if information was complete and consistent across related data elements. Facilities were contacted to update data if necessary. In addition to this routine monthly assessment, system validation was undertaken annually to determine if LD cases were being reported in the Legionella Case Report Module as expected (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement).

Data Analysis

Case Surveillance

Cases from January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2016, were reviewed to determine the number of cases reported and the percentage of LD cases associated with the VA. For cases classified as definitely VA associated and possibly VA associated with inpatient stay, the patients’ electronic medical records were reviewed to determine type of exposure (acute care and long-term care) (eAppendix 3 in the Supplement). Of note, cases were assessed for classification as VA associated rather than HCA because we could only reliably ascertain health care contact in the VHA system.

Total LD rates in the VHA patient population for each year were determined using the most recently available VA data on total veteran enrollees in25 and enrollees who were users of25 the VHA system as population denominators; the first denominator category is comparable with use of the US population by the CDC to determine national rates, while the second denominator category reflects a subset veteran population more likely to have been diagnosed at a VA facility.

Annual rates of community- and VA-associated LD were also calculated. The VA-associated LD rates were assessed separately for patients with overnight stays (inpatient or residential) and patients with only outpatient encounters in the 10 days before symptom onset. For each of these 2 categories, rates were calculated in 2 different ways to account for population-based rates (using unique inpatients or unique outpatients in the patient treatment file data sets and unique residents in the extended care records, as appropriate, for denominator data)26 and exposure potential rates (using outpatient encounters in the patient treatment file,26 or inpatient bed days of care and long-term care resident days in IPEC,27,28 as appropriate, for denominator data). The exposure potential denominators were selected to account for length of stay or amount of contact with health care buildings in a similar manner as is done for other HCA infections.29 The numbers of cases, classifications, and rates were also assessed on a regional level for prospectively reported case data (2015 and 2016) using US Census Bureau divisions to delineate US regions30 (eAppendix 4 in the Supplement). Denominators for regional rate calculations were derived from state-level VHA data for veteran enrollees who used the VHA system in FY 2015 and FY 2016.31,32

Diagnostic Testing

Monthly diagnostic tests performed and test results for Legionella urine antigen tests (UATs) and clinical cultures were extracted from the IPEC Legionella Clinical Information Module for 2015 and 2016. Regional percentage of positivity for each method was calculated using the same US Census Bureau division categories described earlier.

Statistical Analysis

National LD rate trends were assessed using Poisson regression analysis. A log-linear regression model was calculated with enrollees, inpatients, outpatients, or bed days of care used as an offset variable. Overdispersion was accounted for using a quasi-likelihood method approach to estimate a dispersion parameter. Pairwise comparisons of regional LD rates were done by χ2 analyses (.01 level of significance). The exact results for each pairwise comparison are provided to allow for assessment of the strength of the differences in the presence of multiple comparisons. Legionella UAT positivity rates were assessed by χ2 analyses for regional and monthly pairwise comparisons. Case fatality rates were compared using the Fisher exact test.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Inc). All analyses were 2-sided and a P value of less than .05 was considered significant unless otherwise noted.

Results

LD Cases

There were 491 LD cases in the case report surveillance system from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016, and the number of cases increased each year (Table 1). Most cases (447 [91%]) had no VA exposure or only outpatient VA exposure in the 10 days prior to symptom onset and the remaining cases (n = 44) had VA exposure with overnight stay. Total LD rates from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016, increased for all VA enrollees (from 1.5 to 2.0 per 100 000 enrollees; P = .04) and for users of VA health care (2.3 to 3.0 per 100 000 enrollees; P = .04). The LD rate for the subset who had no VA exposure also increased (0.90 to 1.47 per 100 000 enrollees; P < .001). In contrast, the LD rate for patients with VA overnight stay decreased on a population level (5.0 to 2.3 per 100 000 enrollees; P < .001) and an exposure level (0.31 to 0.15 per 100 000 enrollees; P < .001). One-third of the cases (163 of 491) had some VA exposure in the 10 days prior to symptom onset. Thirteen of the 491 LD cases (3%) were definitely associated with a VA facility. Most VA-associated cases were in the possible HCA category (150 of 163 [92%]), the majority (119 of 150 [79%]) with only outpatient exposure in the 10 days prior to symptom onset. Definite VA-associated LD cases primarily had exposure in long-term care settings (11 of 13 [85%]) and possible VA-associated cases with overnight stay primarily had acute care exposure (26 of 31 [84%]) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Five facilities had clusters of LD cases with VA overnight exposure, occurring primarily in 2014 (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Distribution of Legionnaires Disease Cases Reported to the Veterans Health Administration Reporting System by VA Association, 2014 to 2016.

| Case Classification | Cases, No. (%) by Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 (n = 136) | 2015 (n = 174) | 2016 (n = 181) | Total (N = 491) | |

| No VA exposure | 82 (60) | 113 (65) | 133 (73) | 328 (67) |

| Definite VA exposure | 7 (5) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 13 (3) |

| Possible VA exposure | 47 (35) | 56 (32) | 47 (26) | 150 (31) |

| Inpatient | 5 (4) | 5 (3) | 2 (1) | 12 (2) |

| Inpatient and outpatient | 8 (6) | 5 (3) | 6 (3) | 19 (4) |

| Outpatient | 34 (25) | 46 (26) | 39 (22) | 119 (24) |

Abbreviation: VA, Department of Veterans Affairs.

The unadjusted 30-day fatality rate for cases with possible inpatient VA association was higher (8 of 31 [25.8%]; P = .004) than the fatality rate for patients with LD with definite VA association (1 of 13 [7.8%]), possible outpatient VA association (8 of 119 [6.7%]), or no VA association (18 of 327 [5.5%]; no death data for 1 patient). Grouped together, the fatality rate for VA patients with overnight stay exposure (definite or possible inpatient) was higher (9 of 44 [20.5%]; P = .002) than the fatality rate for patients with outpatient or no VA exposure (26 of 446 [5.5%]; no death data for 1 patient).

Because inclusion of outpatient exposure was new in the 2014 CDC definitions for HCA LD,23,24 we examined the impact of the change on attribution of LD cases in the VA data set (Table 2). Including outpatient encounters in the new definition shifted the number of VA-associated cases from 31 to 150, a 384% increase in epidemiologic case attribution. The additional 119 cases classified as possibly VA associated from outpatient-only exposure corresponded with the 27% decrease in classification of cases as community associated.

Table 2. Impact of the Change to the CDC Legionellosis Surveillance Definition on the Classification of Cases Reported in the Veterans Health Administration Reporting System From 2014 to 2016.

| Classification | Previous CDC Definition | Revised CDC Definition | Change in Case Attribution, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely HCA | Patient hospitalized continuously for ≥10 d before onset of Legionella infection | Patient was hospitalized or a resident of a long-term care facility for the entire 10 d prior to onset | |

| LD cases, No. | 13 | 13 | 0 |

| Possibly HCA | Patient hospitalized 2-9 d before onset of Legionella infection | Patient had exposure to a health care facility for a portion of the 10 d prior to onset | |

| LD cases, No. | 31 | 150a | +384 |

| Community-associated | No inpatient or outpatient hospital visits in the 10 d prior to onset of symptoms | No exposure to a health care facility in the 10 d prior to onset | |

| LD cases, No. | 447 | 328b | −27 |

| Total LD cases, No. | 491 | 491 |

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HCA, health care–associated; LD, Legionnaires disease.

This increase in the number of possibly HCA LD cases is a result of the inclusion of 119 cases in the Veterans Health Administration reporting system with only outpatient exposure in the 10 days prior to symptom onset. These 119 cases would have been considered community associated using the previous definition. The remaining 31 cases had inpatient-only (n = 12) or inpatient and outpatient (n = 19) exposure and are the same 31 cases counted using the previous definition for possibly HCA.

This decrease in the number of community-associated LD cases in the Veterans Health Administration reporting system is a result of 119 cases with outpatient-only exposure in the 10 days prior to symptom onset being considered as possibly HCA under the revised definition.

LD Rates

Total LD rates significantly increased between 2014 and 2016 when calculated using either denominator type (Table 3). Most LD cases were not associated with VA exposure, and the rates significantly increased over the review period (Table 3). In contrast, the rates for the subset of LD cases with inpatient VA exposure significantly decreased when calculated for population level and accounting for exposure potential (Table 3). Outpatient-only VA-associated LD rates were low, and the change over time was not significant regardless of calculation on a population or encounter level (Table 3).

Table 3. Legionnaires Disease Cases and Rates in the Veterans Health Administration Health Care System, 2014 to 2016.

| LD Case Category | Denominator Category | No. of LD Cases/Denominator Value, No. | Rate of LD (per 100 000 Denominator Category) | P Value for Poisson Regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |||

| Total and non-VA-associated LD cases | ||||||||

| All reported LD cases (non-VA-associated and VA-associated)a | Total enrollees in VA HCS | 136/9 106 480 | 174/8 965 923 | 181/9 046 663 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.0 | .04 |

| Enrollees who used the VA HCS in the year | 136/5 843 375 | 174/5 927 103 | 181/5 995 048 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 3.0 | .04 | |

| Non-VA-associated LD casesa | Total enrollees in VA HCS | 82/9 106 480 | 113/8 965 923 | 133/9 046 663 | 0.90 | 1.26 | 1.47 | <.001 |

| VA-associated LD cases | ||||||||

| LD cases with inpatient and/or LTC VA exposure (includes definite and possible HCA LD) | Unique inpatients and residents per yearb | 20/397 319 | 15/385 662 | 9/394 033 | 5.0 | 3.9 | 2.3 | <.001 |

| BDOC (inpatient) and resident days (LTC)c | 20/6 437 769 | 15/6 268 381 | 9/5 998 084 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.15 | <.001 | |

| LD cases with only outpatient VA exposure | Unique outpatients/yb | 34/5 996 775 | 46/6 076 638 | 39/6 142 871 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 0.63 | .71 |

| Outpatient encountersc | 34/74 214 643 | 46/76 428 670 | 39/78 067 260 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | .78 | |

Abbreviations: BDOC, bed days of care; HCA, health care–associated; HCS, health care system; LD, Legionnaires disease; LTC, long-term care; VA, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Non-VA-associated cases are patients with LD who did not have contact with a VA health care building in the 10 days prior to symptom onset. It is not possible to reliably know if there was contact with non-VA health care buildings in that period, so this category is not called “community-associated” to avoid potential assumptions of no contact with any health care settings.

Pertains to population-level calculations.

Pertains to exposure-level calculations.

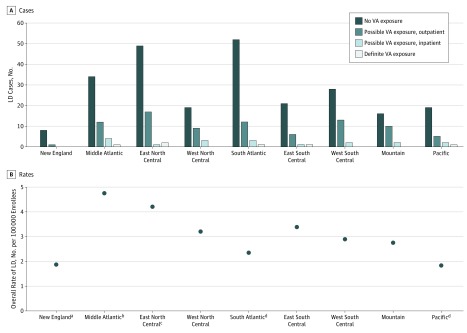

Regional differences in LD incidence in the United States have been reported.9 We categorized the 355 LD cases reported to the IPEC system in 2015 and 2016 by region using US census divisions and we also found differences (Figure). In all regions, non-VA cases were in the majority. The East North Central (ENC) region reported the most LD cases (including the most definite VA-associated cases) and had the second highest rate (Figure). While the South Atlantic (SA) region had almost the same number of total cases as the ENC region, it had one of the lowest total rates of LD and this rate was significantly lower than the ENC rate (eTable 5 in the Supplement). The Middle Atlantic had the highest rate among the regions, and this rate was significantly higher than 3 other regions (New England, SA, and Pacific) (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Figure. Legionnaires Disease (LD) Cases and Rates for 2015 and 2016, by US Regions.

A, Numbers of LD cases reported to the Veterans Health Administration tracking system are shown, categorized by type of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care facility exposure, if any. B, Total LD rates were calculated for each region using the number of enrolled veterans in the regions who used the VHA system in the 2-year period as denominator. The results for each pairwise χ2 test are provided in eAppendix 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement to allow for assessment of the strength of the differences in the presence of multiple comparisons.

aRate was significantly different (P < .01) compared with the rate for the Middle Atlantic region by pairwise χ2 test.

bRate was significantly different (P < .01) compared with the rates for the New England, South Atlantic, and Pacific regions by pairwise χ2 test.

cRate was significantly different (P < .01) compared with the rates for the South Atlantic and Pacific regions by pairwise χ2 test.

dRate was significantly different (P < .01) compared with the rates for the Middle Atlantic and East North Central regions by pairwise χ2 test.

Diagnostic Testing

The case reports from 2014 to 2016 indicated that 482 of 491 cases (98%) had a UAT performed, with the majority having a positive result (463 of 482 [96.1%]). For 338 of 491 cases (68.8%), the only Legionella diagnostic test performed was the UAT. Clinical culture was done for 109 of 491 cases (22%), and 39 (36%) were positive. Many of the 39 cases with a positive clinical culture result also had a positive UAT result (28 of 39 [72%]); the other cases either had a negative UAT result (6 of 11) or did not have a UAT performed (5 of 11). The few cases without a positive UAT or culture (n = 17) were diagnosed using serology, immunochemistry, or nucleic acid testing.

The Clinical Information Module data set was examined to assess the amount of Legionella diagnostic testing performed by VA medical facilities in 2015 and 2016, and these data were categorized by US region and month. In total, 49 805 UATs (Table 4; eTable 6 in the Supplement) and 12 004 clinical Legionella cultures were performed nationally in the 2 years with positivity rates of 0.67% (335 positive results) and 0.23% (28 positive results), respectively. All regions had more than 2900 Legionella UATs performed except New England (Table 4). Two regions, Middle Atlantic and SA, performed more than 10 000 UATs each (eAppendix 5 in the Supplement), but the UAT positivity rates for these regions were some of the lowest in the country. The highest UAT positivity rate was in the ENC region. See eTable 7 in the Supplement for pairwise χ2 analyses of regional UAT positivity. Analysis of UAT data by month showed significantly higher positivity rates in warmer months (Table 4; eTable 8 in the Supplement), despite more UATs performed in cooler months. Clinical culture positivity was low for all regions (eTable 9 in the Supplement).

Table 4. Legionella Urinary Antigen Testing in Veterans Affairs Medical Facilities in 2015 and 2016a.

| Variable | Positive Tests, No./Tests Performed, No. (%)b |

|---|---|

| US region | |

| New England | 7/1381 (0.51) |

| Middle Atlantic | 41/10 482 (0.39) |

| East North Central | 65/5840 (1.11) |

| West North Central | 32/2991 (1.07) |

| South Atlanticc | 70/11 651 (0.60) |

| East South Central | 26/3539 (0.73) |

| West South Central | 43/6034 (0.71) |

| Mountain | 27/4326 (0.62) |

| Pacific | 24/3561 (0.67) |

| Month | |

| January | 18/5099 (0.35) |

| February | 15/4457 (0.34) |

| March | 20/4876 (0.41) |

| April | 23/4447 (0.52) |

| May | 27/3985 (0.68) |

| June | 32/3545 (0.90) |

| July | 39/3380 (1.15) |

| August | 41/3555 (1.15) |

| September | 43/3714 (1.16) |

| October | 33/3921 (0.84) |

| November | 20/4046 (0.49) |

| December | 24/4780 (0.50) |

| Total | 335/49 805 (0.67) |

See the eAppendix 5 and eTable 6 in the Supplement for a full breakdown of regional testing by month.

The χ2 pairwise comparison results are available for both regional (eTable 7 in the Supplement) and monthly (eTable 8 in the Supplement) data.

The South Atlantic division includes data from Veterans Health Administration facilities in Puerto Rico. This territory is not included in the US Census Bureau delineation of regions and divisions.29

Discussion

The VHA LD reporting database is unique for collecting information on LD in a nationally distributed US health care system. Reporting indicated that LD was a very infrequent diagnosis regardless of exposure classification. Nonetheless, the overall LD rate in VHA patients significantly increased during the review period, corresponding with the significant increase in the subset of LD cases that had no VA exposure and in alignment with increasing LD rates in the United States.9,10 In contrast, the number of LD cases with VA overnight exposure was very low, with significantly decreasing rates over the 3 years. Taken together, these data strongly support that community sources contribute to most of the LD infections in the United States.10 The decrease in the LD rate in patients and/or residents with an overnight stay may be a result of intense efforts at VA facilities after publication of the most recent policy in 201419 to prevent Legionella growth in building water distributions systems (eAppendix 6 in the Supplement), a supposition similar to a previous review of LD and VHA policy.33 While determining a direct correlation between current policy implementation and the decrease in reported cases is beyond the scope of this article, the reduction in case clusters over the 3-year period further suggests improved prevention practices. The results also indicate the particular importance of Legionella prevention programs, including LD diagnostic testing, in long-term care settings where high-risk occupants may have prolonged exposure to facility water sources.

The 2015 total LD rate in the VHA enrollee population in this study (1.9 cases per 100 000 persons) was comparable to the 2015 LD rate in the US population for all ages (1.89 cases per 100 000 persons).7 To our knowledge, this is the first report of national active surveillance of HCA LD cases in the United States and the first estimation of national HCA LD rates. While there is no known comparator in the US population for HCA LD rates, it is notable that the 2015 rate for VA LD with overnight stay (3.9 cases per 100 000 patients and/or residents) is similar to that in the general population for persons aged 40 to 64 years (2.73 cases per 100 000 persons),7 the age range that corresponds with the median age of female (age 46 years) and male (age 64 years) users of VA benefits.34 Furthermore, the percentage of LD cases that were definitely VA associated (3%) was similar to recent CDC reporting of definite HCA LD in 21 US jurisdictions.11

We did not calculate an overall rate of VA-associated cases because of the variability in the extent and types of exposure to facility water sources between inpatient and/or residential contact and outpatient contact. Furthermore, inclusion of outpatient contact in the possible HCA LD CDC definition is relatively new. This work demonstrates that the definition change, while not affecting the overall number of LD cases, shifted the classification of cases and resulted in an increase in attribution of possible HCA LD with a compensatory decrease in community-associated cases. While perhaps helpful for surveillance, the actual contribution of outpatient and/or transient contact with a health care building to transmission of Legionella is uncharacterized.

It has been surmised that the number of LD cases is underdiagnosed in the United States in part because pneumonia cases are often empirically treated with antibiotics. We assessed LD diagnostic testing in the context of Legionella prevention policy19 that promotes testing beyond guidelines.12,13 Increased use of Legionella UAT and clinical culture by VA facilities in 2015 and 2016 compared with previously reported testing levels in FY 2012 (15 169 UATs and 3091 clinical cultures)35 did not result in the detection of large numbers of LD cases or a marked increase from previously reported numbers of HCA LD in VA.33,35 Regions where more than 10 000 UATs were performed in 2015 and 2016 had significantly lower UAT positivity rates in general than other regions that performed less testing. Nonetheless, the data substantiated regional differences in LD rates reported by others9 with higher LD rates in general in the eastern part of the United States. While extensive use of UAT did not result in increased UAT positivity rates, the regions that did the most testing in 2015 to 2016 corresponded to regions with the most numbers of LD cases in those same years (compare Table 4 and Figure). The ranking of the regional LD rates in VA are consistent with CDC reporting of regional rates for 20099 for regions with the highest (Middle Atlantic and ENC) and lowest (Pacific) rates. A notable exception is the SA region, which had one of the highest rates in the CDC report for 2009 but one of the lowest rates in the VA.

Increased LD testing occurred in cooler months, perhaps reflecting the higher incidence of respiratory infections in those months. However, as observed by others,8,9 the UAT positivity rate for LD was significantly higher in the summer months. Overall, the testing data suggest that heightened awareness for LD in patients with pneumonia may be important on an individual case level for optimal treatment and in regions of the country known to have higher incidence of LD,36 but oversensitivity for diagnosis uses resources without necessarily increasing case identification.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, facilities may have missed identifying patients for Legionella testing. However, because heightened awareness for LD is established by policy and extensive testing is occurring nationally across the system, it is unlikely that a large number of cases were missed. Overall, the VHA requirement for reporting LD cases, the system validation review, and educational outreach provide confidence in the general completeness of the data. Second, patients with LD who were not diagnosed or subsequently cared for at VA medical facilities and had no VA exposure in the 10 days prior to symptom onset are not captured by the reporting system. It is unknown how many cases this represents, and this report focuses on those cases with VA contact and/or care. Third, this work uses facility-reported data from Legionella surveillance systems; we did not conduct routine medical record reviews of all reported cases to assess accuracy of the LD diagnosis or to confirm that patients had signs or symptoms of pneumonia. Future work is planned to examine patient demographic characteristics and symptoms as a detailed review of the spectrum of LD. Finally, similar to other surveillance systems, the VHA LD reporting modules did not collect information on implementation of interventions to prevent cases; a comparison of actions at facilities that did and did not have HCA LD cases to determine effective prevention practices was outside the scope of this work.

Conclusions

This study provides insight into HCA LD in the United States. Perhaps most importantly, these findings from a novel, rigorous reporting program add to the body of knowledge about HCA LD that was previously largely gleaned from local outbreak reports or limited passive surveillance. The number of VA-associated LD cases with overnight exposure was low, with decreasing rates in this category over the study period despite increasing overall rates. This finding sets the stage for additional reviews to assess the contribution of VHA’s proactive Legionella prevention policy, including analysis of national environmental Legionella data, on the observed improvement in patient safety. Generalization of the results in this study to HCA LD in the United States may be affected by VA population biases. Nonetheless, this study is informative to other health care facilities that are considering implementation of Legionella prevention policies. This is particularly relevant because regulatory,37 accreditation,38 and standards39 organizations have recently prioritized water safety in health care.

eTable 1. Data Elements in the VHA Ad Hoc Legionella Case Report Database

eTable 2. VHA Monthly Legionella Clinical Information Database Elements for Collection of Aggregate Data on Legionella Diagnostic Testing

eTable 3. Association of Definite Healthcare-Associated Legionnaires Disease (HCA LD) Cases and Possible HCA LD Cases (with inpatient stay) With Acute Care and/or Long Term Care Exposure in the 10 Days Prior to Symptom Onset

eTable 4. Occurrences of Clusters of LD Cases Reported by VA Medical Facilities in the IPEC Legionella Case Report Database

eTable 5. Pairwise Chi-Square Comparisons of LD Rates Between Regions

eTable 6. Legionella Urinary Antigen Testing in VA Medical Facilities in 2015 and 2016, by Region

eTable 7. Pairwise Chi-Square Comparisons of Legionella Urine Antigen Test Positivity Rates Between Regions

eTable 8. Pairwise Chi-Square Comparisons of Legionella Urine Antigen Test Positivity Rate Between Months

eTable 9. Legionella Clinical Culture in VHA Facilities In 2015 and 2016, by Region

eAppendix 1. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Legionnaires Disease (LD) Reporting Databases

eAppendix 2. Validation That Legionella Cases Were Reported by VA Medical Facilities

eAppendix 3. Additional Epidemiologic Information for Reported Legionnaires Disease (LD) Cases

eAppendix 4. Analysis of Legionnaires Disease Rates by US Regions

eAppendix 5. Legionella Diagnostic Testing

eAppendix 6. VHA Legionella Prevention Policy

References

- 1.Mercante JW, Winchell JM. Current and emerging Legionella diagnostics for laboratory and outbreak investigations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(1):-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gamage SD, Ambrose M, Kralovic SM, Roselle GA. Water safety and Legionella in healthcare: priorities, policy, and practice. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30(3):689-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demirjian A, Lucas CE, Garrison LE, et al. . The importance of clinical surveillance in detecting Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks: a large outbreak in a hospital with a Legionella disinfection system—Pennsylvania, 2011-2012. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(11):1596-1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lapierre P, Nazarian E, Zhu Y, et al. . Legionnaires’ disease outbreak caused by endemic strain of Legionella pneumophila, New York, New York, USA, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(11):1784-1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhoads WJ, Garner E, Ji P, et al. . Distribution system operational deficiencies coincide with reported Legionnaires’ disease clusters in Flint, Michigan. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51(20):11986-11995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinn C, Demirjian A, Watkins LF, et al. . Legionnaires’ disease outbreak at a long-term care facility caused by a cooling tower using an automated disinfection system—Ohio, 2013. J Environ Health. 2015;78(5):8-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams DA, Thomas KR, Jajosky RA, et al. ; Nationally Notifiable Infectious Conditions Group . Summary of notifiable infectious diseases and conditions—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;64(53):1-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neil K, Berkelman R. Increasing incidence of legionellosis in the United States, 1990-2005: changing epidemiologic trends. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(5):591-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hicks LA, Garrison LE, Nelson GE, Hampton LM; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Legionellosis—United States, 2000-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(32):1083-1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrison LE, Kunz JM, Cooley LA, et al. . Vital signs: deficiencies in environmental control identified in outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease—North America, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(22):576-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soda EA, Barskey AE, Shah PP, et al. . Vital signs: healthcare-associated Legionnaires’ disease surveillance data from 20 states and a large metropolitan area—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(22):584-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America . Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. . Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):e61-e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veterans Health Administration VHA expenditures, enrollees, and patients. November 3, 2017. http://vaww.va.gov/VHAOPP/enroll01/VitalSignsNational/FY17/Table_A_NATIONAL_Aug17.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- 15.National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics VA utilization profile. November 2017. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Quickfacts/VA_Utilization_Profile.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- 16.Wilson NJ, Kizer KW. The VA health care system: an unrecognized national safety net. Health Aff (Millwood). 1997;16(4):200-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Veterans Affairs Blueprint for Excellence. Veterans Health Administration, 2014. http://www.va.gov/HEALTH/docs/VHA_Blueprint_for_Excellence.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2018.

- 18.Hung TL, Li MC, Wang LR, et al. . Legionnaires’ disease at a medical center in southern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;pii: S1684-1182(16):30141-30144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veterans Health Administration VHA directive 1061: prevention of healthcare-associated Legionella disease and scald injury from potable water distribution systems. August 13, 2014. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=3033. Accessed November 19, 2017.

- 20.Department of Veterans Affairs About Veterans Health Administration. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutVHA.asp. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- 21.Department of Veterans Affairs Geriatrics and extended care. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/Guide/LongTermCare/VA_Community_Living_Centers.asp#. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- 22.Jain R, Kralovic SM, Evans ME, et al. . Veterans Affairs initiative to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1419-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Legionellosis case report form. January 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/downloads/case-report-form.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2017.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Legionellosis case report form. February 2003. https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/downloads/case-report-form.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- 25.Veterans Health Administration, Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health Policy and Planning VHA expenditures, enrollees, and patient trends for federal fiscal year (FY) 2014, FY2015 and FY2016. Dates prepared: December 2, 2014, December 2, 2015, and December 8, 2016. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Expenditures.asp. Accessed November 2, 2017.

- 26.Veterans Health Administration, Austin Information Technology Center Patient treatment files (PTF). https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/patient-treatment-file-ptf. Accessed August 2, 2016 and September 7, 2017.

- 27.Veterans Health Administration Inpatient Evaluation Center Data reporting by VA medical facilities [database online]. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration Inpatient Evaluation Center; 2016. Accessed February 5, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veterans Health Administration Inpatient Evaluation Center Data reporting by VA medical facilities [database online]. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration Inpatient Evaluation Center; 2017. Accessed September 7, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tokars JI. Modern quantitative epidemiology in the healthcare setting In: Mayhall CG, ed. Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control. 4th ed Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012:20-48. [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Census Bureau Geographic terms and concepts—census divisions and census regions. https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html. Accessed November 19, 2017.

- 31.National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. State/territories summary reports https://www.va.gov/vetdata/stateSummaries.asp. Accessed October 19, 2016.

- 32.National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. State/territories summary reports https://www.va.gov/vetdata/stateSummaries.asp. Accessed October 31, 2017.

- 33.Kelly AA, Danko LH, Kralovic SM, Simbartl LA, Roselle GA. Legionella in the Veterans Healthcare system: report of an eight-year survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;131(2):835-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics VA utilization profile, FY 2016. November 2017. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Quickfacts/VA_Utilization_Profile.pdf. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- 35.Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General Healthcare inspection: prevention of Legionnaires’ disease in VHA facilities. August 1, 2013. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-13-01189-267.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2017.

- 36.Decker BK, Harris PL, Muder RR, et al. . Improving the diagnosis of Legionella pneumonia within a healthcare system through a systematic consultation and testing program. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1289-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Requirement to reduce Legionella risk in healthcare facility water systems to prevent cases and outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease (LD). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-17-30.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2017.

- 38.Joint Commission Patient safety: fight back: learn ways to mitigate legionnaire’s disease in your organization. September 27, 2017. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/23/JC_Online_Sept._27.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2017.

- 39.American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers ANSI/ASHRAE standard 188-2015. Legionellosis: risk management for building water systems. 2015. https://www.ashrae.org/. Accessed December 28, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Data Elements in the VHA Ad Hoc Legionella Case Report Database

eTable 2. VHA Monthly Legionella Clinical Information Database Elements for Collection of Aggregate Data on Legionella Diagnostic Testing

eTable 3. Association of Definite Healthcare-Associated Legionnaires Disease (HCA LD) Cases and Possible HCA LD Cases (with inpatient stay) With Acute Care and/or Long Term Care Exposure in the 10 Days Prior to Symptom Onset

eTable 4. Occurrences of Clusters of LD Cases Reported by VA Medical Facilities in the IPEC Legionella Case Report Database

eTable 5. Pairwise Chi-Square Comparisons of LD Rates Between Regions

eTable 6. Legionella Urinary Antigen Testing in VA Medical Facilities in 2015 and 2016, by Region

eTable 7. Pairwise Chi-Square Comparisons of Legionella Urine Antigen Test Positivity Rates Between Regions

eTable 8. Pairwise Chi-Square Comparisons of Legionella Urine Antigen Test Positivity Rate Between Months

eTable 9. Legionella Clinical Culture in VHA Facilities In 2015 and 2016, by Region

eAppendix 1. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Legionnaires Disease (LD) Reporting Databases

eAppendix 2. Validation That Legionella Cases Were Reported by VA Medical Facilities

eAppendix 3. Additional Epidemiologic Information for Reported Legionnaires Disease (LD) Cases

eAppendix 4. Analysis of Legionnaires Disease Rates by US Regions

eAppendix 5. Legionella Diagnostic Testing

eAppendix 6. VHA Legionella Prevention Policy