Zoliflodacin is a novel spiropyrimidinetrione with activity against bacterial type II topoisomerases that inhibits DNA biosynthesis and results in accumulation of double-strand cleavages in bacteria. We report results from two phase 1 studies that investigated the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics (PK) of zoliflodacin and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) after single doses in healthy volunteers.

KEYWORDS: ADME, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, healthy volunteers, single dose, zoliflodacin

ABSTRACT

Zoliflodacin is a novel spiropyrimidinetrione with activity against bacterial type II topoisomerases that inhibits DNA biosynthesis and results in accumulation of double-strand cleavages in bacteria. We report results from two phase 1 studies that investigated the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics (PK) of zoliflodacin and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) after single doses in healthy volunteers. In the single ascending dose study, zoliflodacin was rapidly absorbed, with a time to maximum concentration of drug in serum (Tmax) between 1.5 and 2.3 h. Exposure increased dose proportionally up to 800 mg and less than dose proportionally between 800 and 4,000 mg. Urinary excretion of unchanged zoliflodacin was <5.0% of the total dose. In the fed state, absorption was delayed (Tmax, 4 h), accompanied by an increase in the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) at 1,500- and 3,000-mg doses. In the ADME study (3,000 mg orally), the PK profile of zoliflodacin had exposure (AUC and maximum concentration of drug in serum [Cmax]) similar to that of the ascending dose study and a median Tmax of 2.5 h. A total of 97.8% of the administered radioactivity was recovered in excreta, with urine and fecal elimination accounting for approximately 18.2% and 79.6% of the dose, respectively. The major clearance pathway was via metabolism and elimination in feces with low urinary recovery of unchanged drug (approximately 2.5%) and metabolites accounting for 56% of the dose excreted in the feces. Zoliflodacin represented 72.3% and metabolite M3 accounted for 16.4% of total circulating radioactivity in human plasma. Along with the results from these studies and based upon safety, PK, and PK/pharmacodynamics targets, a dosage regimen was selected for evaluation in a phase 2 study in urogenital gonorrhea. (The studies discussed in this paper have been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under identifiers NCT01929629 and NCT02298920.)

INTRODUCTION

Uncomplicated gonococcal (GC) infection due to Neisseria gonorrhoeae is one of the leading causes of sexually transmitted diseases worldwide (1, 2). Untreated GC infection leads to serious morbidity, including pelvic inflammatory disease, septic arthritis, meningitis, and endocarditis (3, 4). The number of cases of GC infection continues to increase worldwide, accompanied by increasing resistance to antimicrobial therapy (1, 2). The World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have classified GC infection as one of the infections for which we have an urgent need for new and novel antimicrobial agents to overcome bacterial resistance (3, 4).

Zoliflodacin is a novel spiropyrimidinetrione with activity against bacterial type II topoisomerases; it inhibits DNA biosynthesis and causes accumulation of double-strand cleavages in bacteria, where it stabilizes and arrests the cleaved covalent complex of gyrase with double-strand broken DNA (5–7). These effects are similar to those of fluoroquinolones; however, zoliflodacin prevents relaxation of this cleaved complex at permissive conditions and, thus, blocks ligation of the double-strand cleaved DNA to form fused circular DNA (6–8).

Zoliflodacin antibacterial activity has been extensively evaluated in preclinical studies (5, 7, 9, 10). In vitro studies have shown that resistant Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, including fluoroquinolone- and vancomycin-resistant staphylococci and ciprofloxacin-, ceftriaxone-, and penicillin-resistant N. gonorrhoeae, remain sensitive to zoliflodacin (6, 8, 11, 12). Zoliflodacin demonstrated in vitro activity against bacterial strains that often are resistant to ceftriaxone or azithromycin, which are recommended as first-line therapies for treating GC infections (13, 14).

We report results from two phase 1 clinical studies. One study investigated the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics (PK) of zoliflodacin after single ascending oral doses (SAD) and during fed and fasted states (ClinicalTrials registration no. NCT01929629). The other study evaluated the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of a single oral dose of [14C]zoliflodacin in healthy volunteers (ClinicalTrials registration no. NCT02298920).

RESULTS

SAD study.

Forty-eight healthy subjects (46 males) were randomized in part A, of which 36 received active treatment. The 10 males and 2 females were in the placebo treatment arm. In part B, 18 subjects (all males) were randomized and all received treatment. In part A, 1 subject in the 800-mg zoliflodacin group was lost to follow-up, and in part B, all subjects completed the study. Baseline characteristics were comparable across dose groups for both parts A and B (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics across clinical studies

| Variable | Value for: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAD |

ADME study (3,000 mg, n = 6) | ||||

| Part A |

Part B |

||||

| Placebo (n = 12) | All doses (n = 36) | 1,500 mg (n = 8) | 3,000 mg (n = 10) | ||

| Age, yra | 32 ± 13 | 31 ± 11 | 29 ± 6 | 31 ± 9 | 34 |

| Age range, yr | 20–55 | 19–53 | 22–40 | 23–48 | 21–53 |

| Males, n (%) | 10 (83.3) | 36 (100) | 8 (100) | 10 (100) | 6 (100) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White | 5 (41.7) | 17 (47.2) | 3 (37.5) | 8 (80.0) | 5 (83.3) |

| Black or African American | 5 (41.7) | 17 (47.2) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0 |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 1 (8.3) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| Asian | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (8.3) | 3 (8.3) | 2 (25.0) | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| Weight, kga | 78.5 ± 11.3 | 77.0 ± 10.8 | 75.8 ± 10.9 | 78.7 ± 11.9 | 83.6 |

| BMI, kg/m2a | 26.0 ± 3.1 | 25.2 ± 2.9 | 24.1 ± 3.1 | 25.9 ± 3.1 | 27.0 |

Means ± standard deviations.

(i) SAD pharmacokinetics (part A). After single ascending oral doses of 200 to 4,000 mg, zoliflodacin demonstrated rapid absorption with a monophasic decline in plasma concentrations thereafter at all doses (Fig. 1). Exposure (area under the concentration-time curve [AUC] and maximum concentration of drug in serum [Cmax]) generally increased in a dose-proportional manner (Table 2). Median time to maximum concentration of drug in serum (Tmax) ranged from 1.5 to 2.3 h, and mean terminal elimination half-life (t1/2) was relatively consistent across all doses, ranging from 5.3 to 6.3 h. The dose proportionality relationships, as assessed by a linear model across doses of zoliflodacin from 200 to 4,000 mg, had a slope estimate of 0.89 (90% confidence interval [CI], 0.82, 0.95) for AUC and 0.81 (90% CI, 0.73, 0.88) for Cmax.

FIG 1.

Geometric mean plasma concentrations of zoliflodacin (logarithmic scale) versus time curves (pharmacokinetic analysis set, n = 6).

TABLE 2.

Geometric mean (standard deviation) plasma pharmacokinetic parameters for zoliflodacin after single doses

| Parameter | Value for part: |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A |

B |

|||||||||

| 200 mg (n = 6) | 400 mg (n = 6) | 800 mg (n = 6) |

1,600 mg (n = 6) |

3,000 mg (n = 6) |

4,000 mg (n = 6) |

1,500 mg fed (n = 8) |

1,500 mg fasted (n = 8) |

3,000 mg fed (n = 10) |

3,000 mg fasted (n = 10) |

|

| AUC0-t, ng·h/ml | 14,500 (1.1) | 31,200 (1.2) | 68,200 (1.3) | 108,000 (1.3) | 183,000 (1.2) | 209,000 (1.5) | 129,000 (1.2) | 109,000 (1.2) | 281,000 (1.3) | 195,000 (1.4) |

| Cmax, ng/ml | 2,010 (1.1) | 4,870 (1.2) | 10,000 (1.2) | 13,400 (1.4) | 20,200 (1.2) | 26,100 (1.6 | 12,100 (1.2) | 15,100 (1.2) | 24,000 (1.3) | 22,900 (1.4) |

| Tmax, ha | 2.3 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.5 (1.0–6.0) | 2.3 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.5–4.0) | 4.0 (4.0–4.0) | 2.5 (2.0–4.0) | 4.0 (1.5–8.0) | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) |

| t1/2, h | 5.6 (0.6) | 5.3 (1.0) | 6.3 (1.0) | 5.9 (1.1) | 6.2 (0.4) | 6.1 (1.0) | 5.6 (1.0) | 5.5 (1.1) | 6.2 (0.4) | 6.2 (0.4) |

| CL/F, liters/h | 13.7 (1.1) | 12.8 (1.2) | 11.7 (1.3) | 14.8 (1.3) | 16.4 (1.2) | 19.1 (1.5) | 11.6 (1.2) | 13.8 (1.2) | 10.7 (1.3) | 15.4 (1.4) |

| Vz/F, liters | 110.0 (1.1) | 96.5 (1.3) | 106.0 (1.2) | 124.0 (1.4) | 145.0 (1.2) | 165.0 (1.4) | 92.5 (1.2) | 107.0 (1.2) | 94.8 (1.3) | 136.0 (1.4) |

| CLR | 0.63 (1.19) | 0.53 (1.28) | 0.47 (1.56) | 0.43 (1.35) | 0.58 (1.14) | 0.50 (1.12) | 0.59 (1.27) | 0.48 (1.43) | 0.56 (1.26) | 0.55 (1.31) |

Median (range).

(ii) Food effect pharmacokinetics (part B). Following oral doses of 1,500 and 3,000 mg zoliflodacin, a slight increase in geometric mean AUC (17% at 1,500 mg and 40% at 3,000 mg) was observed in the fed state compared to the fasted state (Table 3). In contrast, a decrease of 20% in geometric mean Cmax was observed with the 1,500-mg dose for the fasted versus fed state, while an increase of 5% was observed at the 3,000-mg dose. At both doses, median Tmax was 2.5 h for fasted subjects and 4.0 h for fed subjects, indicating delayed absorption in the fed state.

TABLE 3.

Statistical comparison of PK parameters for zoliflodacin under fed and fasting conditions

| Dose and parameter | Treatmenta | N | Geometric LS mean | 95% CI | Comparison of treatments |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fed/fasted ratio (%) | 90% CI | |||||

| 1,500 mg | ||||||

| AUC, ng·h/ml | A | 8 | 129,300 | 109,600, 152,500 | 118.8 | 111.4, 126.6 |

| B | 8 | 108,900 | 92,310, 128,400 | |||

| Cmax, ng/ml | A | 8 | 12,080 | 10,620, 13,740 | 80.1 | 70.6, 90.9 |

| B | 8 | 15,080 | 13,260, 17,150 | |||

| 3,000 mg | ||||||

| AUC, ng·h/ml | A | 10 | 281,400 | 235,800, 336,000 | 144.6 | 122.3, 170.9 |

| B | 10 | 194,700 | 163,100, 232,400 | |||

| Cmax, ng/ml | A | 10 | 23,960 | 19,910, 28,840 | 104.7 | 86.3, 127.1 |

| B | 10 | 22,870 | 19,010, 27,530 | |||

Treatment A, single dose in fed state; treatment B, single dose in fasted state.

(iii) Safety and tolerability. For both parts A and B, no serious adverse effects (AEs), discontinuation for AEs, or deaths were reported, and no clinically significant changes were observed for vital signs, electrocardiogram (ECG), or clinical laboratory evaluations. In part A, 28 (58.3%) subjects reported an AE, all of mild intensity. Upper respiratory infection (2 subjects, 5.6%), dysgeusia (19 subjects, 52.8%), and headache (5 subjects, 13.9%) were the only AEs that occurred in more than 1 subject. Eleven of 19 subjects with dysgeusia received the 3,000- or 4,000-mg dose. In part B, 16 (88.9%) subjects reported an AE, all of mild intensity. Dysgeusia (12 subjects, 66.7%) and headache (7 subjects, 38.9%) were the most common AEs.

Mass balance/ADME study.

Six male subjects were enrolled and completed the study. Mean age was 34 years, and mean body mass index (BMI) was 27.0 kg/m2.

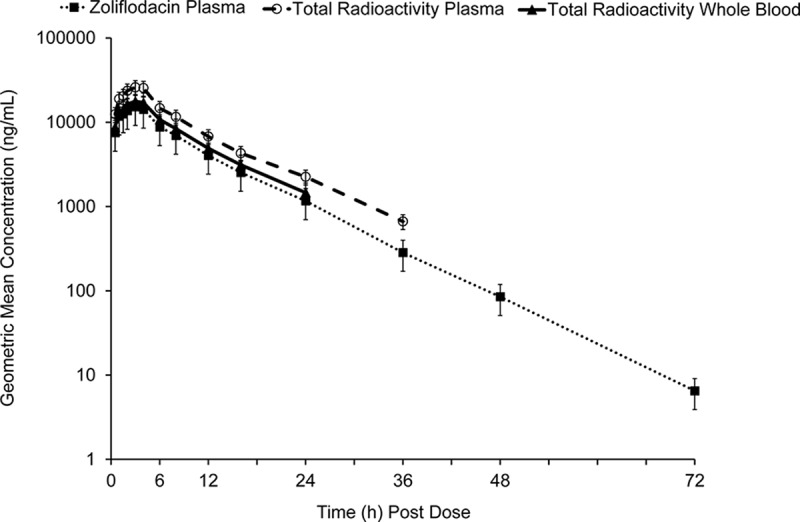

(i) Pharmacokinetics. Following administration of 3,000 mg [14C]zoliflodacin, plasma zoliflodacin levels and total radioactivity in plasma and whole blood appeared to have similar concentration-time profiles; however, plasma zoliflodacin was detectable longer than total radioactivity (Fig. 2). After reaching Cmax, plasma concentrations declined in a monoexponential manner, with mean t1/2 values for zoliflodacin and total radioactivity in plasma of approximately 6.5 and 7.5 h, respectively. Median Tmax for zoliflodacin total radioactivity in plasma and in whole blood ranged from 1.5 to 4.0 h (Table 4). AUC, apparent total clearance (CL/F), and apparent volume of distribution (Vz/F) results were consistent with those of the SAD study. Zoliflodacin represented approximately 72.3% and metabolite M3 accounted for 16.7% of total radioactivity in plasma (as assessed by AUC), with five metabolites accounting for <5% of the circulating radioactivity. M3 was also detected in rat studies (∼7% of circulating [14C]zoliflodacin) (15). While disproportionate exposure to M3 was observed in rats versus humans, an estimate of its exposure by AUC at a NOAEL (no observed adverse event level) for a zoliflodacin dose of 200 mg/kg of body weight in rats was approximately 75 µg·h/ml, exceeding an estimated exposure of 41 µg·h/ml in humans by nearly 2-fold. Mean blood-to-plasma concentration ratios ranged from 0.63 to 0.73 through 36 h postdose, and the mean percent radioactivity ranged from 16.3 to 27.8% after accounting for predose hematocrit values. These findings indicate low association of radioactivity with red blood cells.

FIG 2.

Arithmetic mean (SD) zoliflodacin plasma concentration-time profiles and total radioactivity concentration-time profiles in plasma and whole blood (PK population). Assay range was 1.00 ng/ml (LLOQ) to 5,000 ng/ml.

TABLE 4.

Summary of PK parameters for zoliflodacin in plasma and total radioactivity in plasma and whole blood

| Parameter | Value for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Zoliflodacin in plasma (n = 6) |

[14C]Zoliflodacin total radioactivity |

||

| Plasma (n = 6) | Whole blood (n = 6) | ||

| Cmax, ng/ml | 16,370 (26.1) | 27,540 (22.6) | 18,870 (21.9) |

| AUC0-t, h·ng/ml | 148,400 (20.5) | 252,600 (16.8) | 167,600 (17.1) |

| AUC0-∞, h·ng/ml | 148,400 (20.5) | 257,900 (16.8) | 177,900 (16.5) |

| t1/2, h | 6.5 (5.3–8.4) | 7.5 (6.1–10.1) | 6.4 (5.3–9.3) |

| Tmax, ha | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | 2.5 (2.0–4.0) | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) |

| CL/F, liters/h | 20.2 (20.5) | NC | NC |

| Vz/F, liters | 188.2 (21.5) | NC | NC |

| Ratio | 0.576b | NC | 0.690c |

Values are geometric means (%CV or range) unless otherwise specified. Units for Cmax and AUC for total radioactivity are nanogram equivalents per gram and nanogram equivalents per hour per gram, respectively. Values for Tmax are medians (ranges). NC, not calculated.

Ratio of zoliflodacin AUC0-∞ in plasma to total radioactivity in plasma.

Ratio of zoliflodacin AUC0-∞ for total radioactivity in whole blood to plasma.

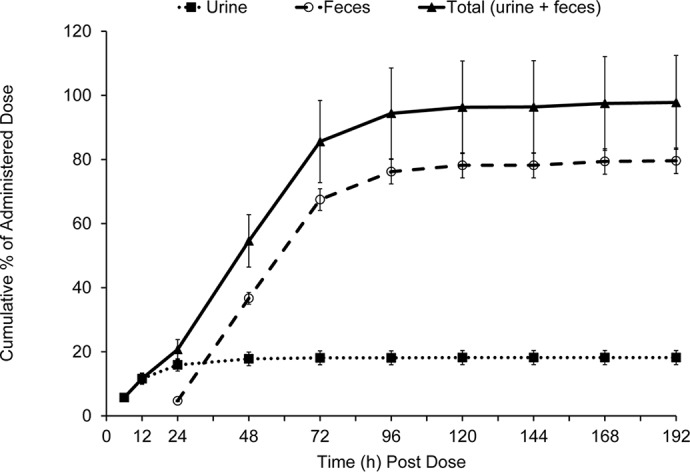

The overall mean recovery of radioactivity in urine and feces samples was approximately 97.8% over the 192-h study, with urine and feces accounting for approximately 18.2% and 79.6%, respectively (Table 5 and Fig. 3). The recovery in individual subjects ranged from 96.7% to 99.0%. Nearly all of the radioactivity was recovered within the first 96 h of dose administration (94.4% recovered collectively in urine and feces). In urine, approximately 2.5% and 18.2% of the dose was recovered as zoliflodacin and total radioactivity, respectively, with the majority of zoliflodacin being excreted in the first 24 h.

TABLE 5.

Arithmetic mean (standard deviation) cumulative percentage of dose recovered as total radioactivity

| Analyte | Cumulative Aea (mg) | Cumulative %Feb |

|---|---|---|

| Zoliflodacin, urine | 74.7 (18.64) | 2.49 (0.62) |

| Total radioactivity, urine | 548.8 (78.66) | 18.15 (2.56) |

| Total radioactivity, feces | 2,405.0 (65.04) | 79.60 (2.44) |

| Total radioactivity, urine + feces | 29,538 | 97.75 (0.75) |

Ae, amount of drug excreted in urine or feces. Aeu is presented for urine; Aef is presented for feces. Units for Ae for total radioactivity are mg equivalents/g.

%Fe is the percentage of drug excreted in urine or feces. %Feu is presented for urine; %Fef is presented for feces.

FIG 3.

Arithmetic mean (±SD) cumulative percentage of dose recovered as total radioactivity in urine and feces (PK population).

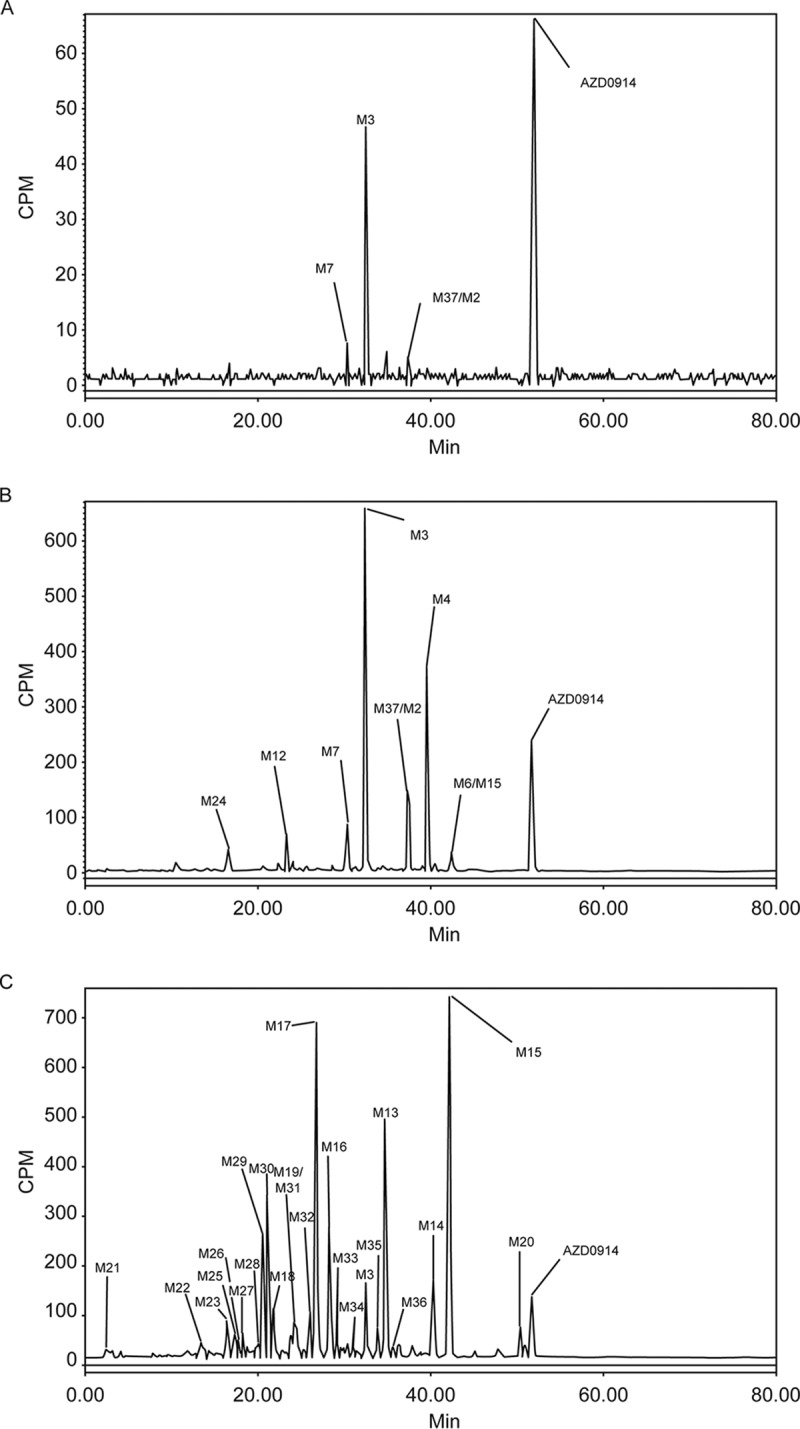

(ii) Metabolite profiles. Relative percentages of each metabolite were determined by peak areas in radiochromatograms of the pooled samples of plasma (% AUC), urine, and feces (% dose) and are summarized in Table 6. Extraction recoveries for metabolite profiling ranged from 91.4% to 95.5% in plasma. Extraction recoveries of fecal homogenates for profiling ranged from 82.7% to 97.3%. Urine was centrifuged to remove insoluble material prior to analysis. Mass spectral data utilized in support of structural assignments are shown in Table 7. Metabolites were identified numerically and were consistent with previous characterization of nonclinical species (15), and there were no unique metabolites identified in humans.

TABLE 6.

Metabolite profiling and identification in plasma, urine, and feces following oral administration of [14C]zoliflodacin (3,000 mg/500 µCi)d

| Metabolite designation | Retention time (min) | Proposed identification | % AUC0-t |

% Dose |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Urine | Feces | Total | |||

| M21 | 2.33–3.00 | Unknown | 0.590 | 0.590 | ||

| M22 | 13.33–13.67 | MP/THP/ISZ/OZD ring-open | 0.935 | 0.935 | ||

| M23 | 16.33–16.50 | MP/THP/ISZ/OZD ring-open | 1.31 | 1.31 | ||

| M24 | 16.50 | Unknown | 0.149 | 0.149 | ||

| M25 | 17.17–17.33 | MP/THP/ISZ/OZD ring-open | 0.926 | 0.926 | ||

| M26 | 17.67 | Unknown | 0.575 | 0.575 | ||

| M27 | 18.17–18.33 | Unknown | 0.675 | 0.675 | ||

| M28 | 19.83–20.00 | MP/ISZ/OZD ring-open | 0.774 | 0.774 | ||

| M29 | 20.33–20.50 | ISZ/OZD ring-open | 6.12 | 6.12 | ||

| M30 | 21.00–21.33 | ISZ/OZD ring-open | 5.27 | 5.27 | ||

| M18 | 21.67–21.83 | ISZ/OZD ring-open | 2.06 | 2.06 | ||

| M12 | 23.33 | MP/THP ring-open | 0.431 | 0.431 | ||

| M19 | 24.17–24.50 | MP/THP/ISZ/OZD ring-open | 2.14a | 2.14a | ||

| M31 | 24.17–24.50 | MP/THP/ISZ ring-open | 2.14a | 2.14a | ||

| M32 | 25.83–26.00 | MP/THP/ISZ ring-open | 1.50 | 1.50 | ||

| M17 | 26.67–26.83 | ISZ/OZD ring-open | 10.7 | 10.7 | ||

| M16 | 28.17–28.33 | MP/THP/ISZ ring-open | 4.89 | 4.89 | ||

| M33 | 29.17 | OZD ring-open | 0.837 | 0.837 | ||

| M7 | 30.33 | MP/THP ring-open | 1.39 | 0.523 | 0.523 | |

| M34 | 31.00 | Unknown | 0.638 | 0.638 | ||

| M3 | 32.33–32.83 | MP/THP ring-open | 16.4 | 8.24 | 0.444 | 8.68 |

| M35 | 33.83–34.00 | ISZ/OZD ring-open | 1.16 | 1.16 | ||

| M13 | 34.67–34.83 | ISZ/OZD ring-open | 6.77 | 6.77 | ||

| M36 | 36.17–36.33 | Unknown | 0.540 | 0.540 | ||

| M37 | 37.33 | OZD ring-open | 1.20b | 1.35b | 1.35b | |

| M2 | 37.33 | OZD ring-open | 1.20b | 1.35b | 1.35b | |

| M4 | 39.50–39.67 | MP ring-open | 0.655 | 2.58 | 2.58 | |

| M14 | 40.33 | ISZ ring-open | 0.694 | 0.694 | ||

| M6 | 42.17–42.50 | Oxy-AZD0914 | 0.258c | 0.258c | ||

| M15 | 42.00–42.50 | ISZ ring-open | 0.258c | 7.07 | 7.33c | |

| M20 | 50.33–50.50 | ISZ/OZD ring-open | 0.669 | 0.669 | ||

| AZD0914 | 51.67–51.83 | AZD0914 | 72.3 | 2.43 | 1.50 | 3.93 |

Coelution of M19 and M31 in feces. Values represent maximum percentage of individual metabolite.

Coelution of M2 and M37 in plasma and urine. Values represent maximum percentage of individual metabolite.

Coelution of M6 and M15 in urine. Values represent maximum percentage of individual metabolite.

Urine collections were obtained and pooled at 0 to 6, 6 to 12, 12 to 24, and 24 to 48 h postdose. Feces were collected and pooled at 0 to 24, 24 to 48, 48 to 72, 72 to 96, 96 to 120, 120 to 144, and 144 to 168 h postdose. MP, morpholine; THP, tetrahydropyridine; OZD, oxazolidinone; ISZ, isoxazole.

TABLE 7.

Accurate mass and MSn data summary for zoliflodacin and identified metabolites

| Metabolite | Measured mass | Theoretical mass | Proposed formula | ▵mDaa | ▵ppma | Characteristic product ions (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M22 | 440.1569 | 440.1577 | C18H23FN5O7+ | −0.70 | −1.6 | 423, 368, 300, 283, 228, 193 |

| M23 | 428.1457 | 428.1464 | C18H23FN3O8+ | −0.70 | −1.6 | 352, 288, 224, 212, 194, 141 |

| M25 | 484.2190 | 484.2202 | C21H31FN5O7+ | −1.20 | −2.5 | 467, 391, 344, 327, 251, 193, 76 |

| M28 | 454.1247 | 454.1256 | C19H21FN3O9+ | −0.90 | −2.0 | 436, 364, 346 |

| M29 | 406.1512 | 406.1521 | C18H21FN5O5+ | −0.90 | −2.2 | 389, 266, 249, 224, 141 |

| M30 | 478.1722 | 478.1733 | C21H25FN5O7+ | −1.10 | −2.3 | 461, 389, 338, 321, 249, 141, 90 |

| M18 | 464.1930 | 464.1940 | C21H27FN5O6+ | −1.00 | −2.2 | 447, 422, 389, 324, 307, 249, 76 |

| M12 | 392.0995 | 392.1001 | C16H15FN5O6+ | −0.60 | −1.5 | 264, 252, 220, 208, 141 |

| M19 | 485.2032 | 485.2042 | C21H30FN4O8+ | −1.00 | −2.1 | 410, 345, 334, 270, 194, 76 |

| M31 | 511.1821 | 511.1835 | C22H28FN4O9+ | −1.40 | −2.7 | 435, 410, 371, 334, 270, 194 |

| M32 | 525.1615 | 525.1627 | C22H26FN4O10+ | −1.20 | −2.3 | 435, 424, 385, 334, 284, 194, 141 |

| M17 | 408.1195 | 408.1202 | C18H19FN3O7+ | −0.70 | −1.7 | 390, 268, 250, 141 |

| M16 | 511.1820 | 511.1835 | C22H28FN4O9+ | −1.50 | −2.9 | 435, 417, 410, 371, 334, 295, 270, 194, 141 |

| M33 | 432.1306 | 432.1314 | C19H19FN5O6+ | −0.80 | −1.9 | 414, 389, 374, 292, 141 |

| M7 | 522.1617 | 522.1631 | C22H25FN5O9+ | −1.40 | −2.7 | 504, 432, 382, 372, 304, 292, 141, 102 |

| M3 | 508.1823 | 508.1838 | C22H27FN5O8+ | −1.50 | −3.0 | 432, 372, 368, 304, 292, 248, 141, 102 |

| M35 | 407.1353 | 407.1361 | C18H20FN4O6+ | −0.80 | −2.0 | 390, 267, 250, 141 |

| M13 | 465.1768 | 465.1780 | C21H26FN4O7+ | −1.20 | −2.6 | 390, 362, 325, 304, 277, 250 |

| M37 | 404.1357 | 404.1365 | C18H19FN5O5+ | −0.80 | −2.0 | 376, 346, 264, 141 |

| M2 | 462.1772 | 462.1783 | C21H25FN5O6+ | −1.10 | −2.4 | 444, 405, 322, 264, 141, 74 |

| M4 | 506.1666 | 506.1682 | C22H25FN5O8+ | −1.60 | −3.2 | 488, 448, 430, 404, 376, 264, 141 |

| M14 | 491.1559 | 491.1573 | C22H24FN4O8+ | −1.40 | −2.9 | 390, 362, 351, 304, 277, 250 |

| M6 | 504.1513 | 504.1525 | C22H23FN5O8+ | −1.20 | −2.4 | 486, 430, 402, 388, 290, 141 |

| M15 | 491.1562 | 491.1573 | C22H24FN4O8+ | −1.10 | −2.2 | 473, 390, 362, 351, 277, 250 |

| M20 | 422.1351 | 422.1358 | C19H21FN3O7+ | −0.70 | −1.7 | 390, 282, 141 |

| AZD0914 | 488.1563 | 488.1576 | C22H23FN5O7+ | −1.30 | −2.7 | 470, 430, 388, 348, 304, 249, 141, 102 |

▵mDa = (measured mass – theoretical mass) × 1,000. ▵ppm = (▵mDa/theoretical mass) × 1,000.

The empirical formula of protonated zoliflodacin (C22H23FN5O7+) was confirmed by accurate mass (Table 7). Inspection of the presence, absence, and modification of these zoliflodacin product ions in metabolites was used as a basis for structural characterization. Metabolite structure assignments were based upon accurate mass and product ion spectra obtained in MSn (number of mass spectrometry) experiments (Fig. 4). Key product ions are summarized in Table 7. The collision-induced dissociation product ion spectra of the zoliflodacin standard match that of the compound found in plasma, urine, and feces. For zoliflodacin (Fig. 5) the mass spectra showed product ions at m/z 470 (loss of water), 430 (loss of C3H6O), 388 (radical, loss of methyloxazolidinone), 348 (loss of methylbarbiturate), 304 (loss of carbon dioxide from m/z 348), 249 (loss of methyloxazolidinone from m/z 348), 141 (loss of methylbarbiturate), and 102 (loss of methyloxazolidinone).

FIG 4.

Representative radioactivity profiles in pooled plasma at 0 to 24 h (A), urine at 0 to 48 h (B), and feces at 24 to 96 h (C). Urine collections were obtained and pooled at 0 to 6, 6 to 12, 12 to 24, and 24 to 48 h postdose. Feces were collected and pooled at 0 to 24, 24 to 48, 48 to 72, 72 to 96, 96 to 120, 120 to 144, and 144 to 168 h postdose.

FIG 5.

Collision-induced dissociation product ion spectra of zoliflodacin ([M+H]+ = 488).

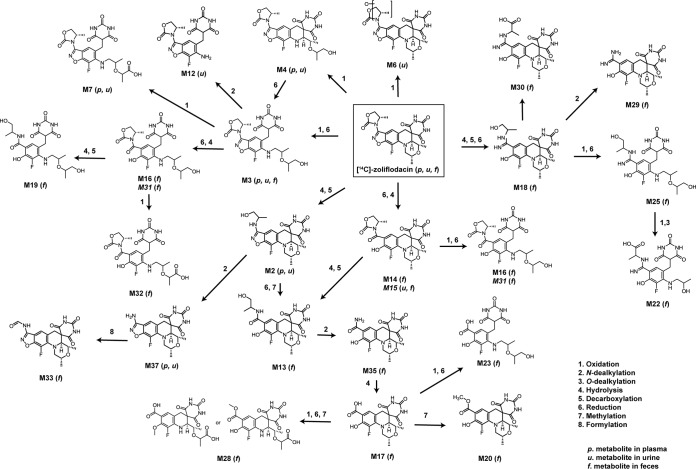

Similar to nonclinical evaluation of [14C]zoliflodacin in rats, parent compounds underwent extensive metabolism, which was the predominant clearance mechanism. A proposed metabolic scheme of zoliflodacin is presented in Fig. 6. Zoliflodacin was the major circulating radioactive component, accounting for 72.3% of total 14C drug-related plasma exposure (AUC). Oxidation of the morpholine ring and cleavage of the tetrahydropyridine ring produced the main plasma and urinary metabolite M3 (16.4% of plasma AUC). Oxidation of M3 produced the corresponding acid M7 (1.39% of plasma exposure). Hydrolysis of the oxazolidinone ring on zoliflodacin with subsequent decarboxylation or N-dealkylation produced coeluting metabolite M2 or M37, respectively (1.2% of plasma AUC). Metabolites identified in the feces accounted for 56% of the administered dose; major metabolites (>5% of dose) included M17, M15, M13, M29, and M30.

FIG 6.

Proposed metabolic scheme of [14C]zoliflodacin following oral administration to humans.

(iii) Safety and tolerability. Three of six subjects experienced an AE consisting of vessel puncture site bruise, back pain, and contact dermatitis. All were of mild intensity, and none were considered related to zoliflodacin treatment. No serious AEs, discontinuation for AEs, or deaths were reported. No clinically significant changes were observed for vital signs, physical examination, ECG, or clinical laboratory evaluations.

DISCUSSION

In the SAD study, exposure generally increased in a dose-proportional manner up to 800 mg, followed by a slightly less than dose-proportional increase up to 4,000 mg. Urinary excretion following single oral doses was <5.0% of the total dose, indicating that renal clearance was a minor route of elimination of zoliflodacin. Zoliflodacin was rapidly absorbed across all doses, and the mean half-life of 5 to 6 h was consistent regardless of dose.

Consistent with the single ascending dose phase, urinary excretion of zoliflodacin at 1,500- and 3,000-mg doses was minimal and appeared to be independent of fed or fasted treatment. Comparison of the effect of fed versus fasted states on PK parameters suggested an increased least-squares (LS) mean ratio for AUC due to food at both doses and a variable effect for Cmax with 1,500- and 3,000-mg doses.

In the ADME study, the PK profile of zoliflodacin at 3,000 mg was consistent with the SAD study, with similar exposure (AUC and Cmax) and absorption characteristics (median Tmax of 2.5 h). Overall, almost complete recovery (∼98% of dose) was obtained in this study, of which 79.6% of the dose was recovered in feces and 18.2% in urine over 192 h. The major elimination pathway was metabolism and elimination by the fecal route, with metabolism contributing 98% of the fecal radioactivity (unchanged zoliflodacin accounts for <2% of the radioactivity in feces). Urinary elimination was low, with only 18% of the dose being excreted through urine and with unchanged zoliflodacin accounting for approximately 2.5% of the dose, indicating that elimination of unchanged compound is a very minor pathway of clearance of zoliflodacin. Both oxidative and reductive metabolism plays a role in the elimination of zoliflodacin. This was first disclosed in nonclinical studies in rodents (15), where pretreatment of mice with aminobenzotriazole (ABT) had no effect on the formation of metabolites M3, M13, M14, M15, and M23, whereas metabolites M1, M2, M4, M6, and M12 were no longer present. This occurred presumably through inhibition of cytochrome P450-mediated oxidation. In addition to oxidation, the human ADME study suggested additional biotransformations included reduction and hydrolysis as well as N- and O-dealkylations. In urine, oxidation of the morpholine ring to open ring metabolites was a common pathway. Further cleavage of the tetrahydropyridine ring resulted in the major urinary metabolite M3. Further oxidation and N-dealkylation resulted in M7. Hydrolysis of the oxazolidinone with decarboxylation or N-dealkylation produced M2 or M37, respectively.

Unlike urine, the vast majority of metabolites in feces were produced via reduction of isoxazole and hydrolysis of the oxazolidinone ring forming the base biotransformations of metabolites M13, M14, M18, M20, M29, M30, and M35. Morpholine and tetrahydropyridine ring open metabolites also underwent similar reductive and hydrolytic modification of their respective isoxazole and oxazolidinone moieties, accounting for metabolites M16, M19, M22, M23, and M25. Nonclinical studies utilizing bile duct cannulated rats suggested efflux of zoliflodacin and/or metabolites accounts for nearly 24% of an intravenously administered dose (15%, 55%, and 24% of the dose recovered in the urine, bile, and feces, respectively) (15). Furthermore, human metabolites characterized in feces were also found to be generated in fecal homogenate of rats. Given the similarity of the fecal metabolite profile of zoliflodacin following oral administration to humans to that of intravenously administered bile duct cannulated rats, it is plausible that efflux and/or gut metabolism of zoliflodacin occurs clinically as well.

In plasma, the parent compound represented 72.3% of total circulating radioactivity, with metabolite M3 as the most abundant circulating component (16.4%). This metabolite was also found to be the most abundant circulating metabolite in rodents (15). Metabolites in humans not previously characterized in rodents were low in abundance and not deemed to be clinically significant. Throughout all investigations in urine, feces, and plasma there was no evidence for metabolic alteration of the barbituric acid moiety of zoliflodacin.

Zoliflodacin is a low-to-moderate clearance compound in preclinical studies. In vitro and in vivo metabolism across species indicates that the compound is extensively metabolized via cytochrome P450- and non-P450-mediated pathways. Single doses of zoliflodacin in the dose range of 2 to 3 g demonstrate low to moderate interactions in simulated trials with CYP3A4 inhibitors. Zoliflodacin is predicted to increase the AUC of either pravastatin or rosuvastatin by <2-fold, primarily through inhibition of hepatic transporters involved in the uptake of these statin drugs.

A PK/pharmacodynamics (PD) driver of AUC/MIC for zoliflodacin has been established using in vitro and in vivo models of infection (8). In these studies, an unbound AUC/MIC of 66 was established as an exposure target for clinical efficacy and, thus, a threshold for determining the probability of target attainment (PTA). Using a MIC90 target of 0.25 mg/liter, an unbound AUC (fraction unbound [fu] = 0.17) in fasted subjects of 27.7 μl·h/ml (lower CI bound) for a 3,000-mg dose would equate to an AUC/MIC of 111, well in excess of a target of 66. While administration of 3,000 mg of zoliflodacin in the fed state results in an approximately 45% increase in AUC, reliance on having to administer zoliflodacin with food is currently not being considered due to higher potential variability. Thus, dose recommendations for advanced clinical trials will likely be based upon PK data obtained from fasted individuals.

In summary, [14C]zoliflodacin undergoes extensive metabolism in humans, and metabolism was the major route of elimination. N. gonorrhoeae rapidly develops resistance to antimicrobials used to treat uncomplicated gonorrhea and is considered an urgent threat by the CDC and WHO because of resistance (3, 4), and many classes of antimicrobial agents are no longer recommended as monotherapy (16). Current treatment guidelines for GC recommend a combination of intramuscular ceftriaxone and oral azithromycin (4), although resistance to both macrolides and cephalosporins has been reported recently (17, 18).

The availability of an effective, well-tolerated oral agent that can be administered alone or in combination to treat uncomplicated gonococcal infection caused by isolates resistant to currently available first-line agents would satisfy an unmet need and potentially reduce the dissemination of multidrug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (4). Results from the two studies reported here and PK/PD-driven exposure targets established in preclinical infection models (8) provide support for the dosage regimen. The early clinical development studies support advancing zoliflodacin into clinical studies to assess its efficacy and safety in patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The phase 1 SAD and ADME studies were conducted at a single study center in Overland Park, Kansas (Quintiles Phase 1 Services), and Madison, Wisconsin (Covance Clinical Research Unit), respectively. Studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices. Study protocols and amendments were approved by an Institutional Review Board, and all subjects provided written informed consent prior to any study procedure.

Single-dose pharmacokinetic study (SAD study).

The primary objective of this phase 1, randomized, placebo-controlled study was to assess (i) the safety, tolerability, and PK of single ascending oral doses of zoliflodacin and (ii) the effects of the fed and fasted states on zoliflodacin PK in healthy subjects.

(i) Study design. The study was organized into 2 parts. Part A was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single ascending dose study. Part B was an open-label food effect study. All subjects attended the Clinical Pharmacology Unit (CPU) on 3 occasions over a period of approximately 7 weeks. Visit 1 was a screening visit within 28 days from the first administration of the investigational product when eligibility to participate in the study was assessed. For visit 2, subjects were admitted to the CPU for 4 days in part A and for 9 days in part B. Subjects were admitted on day −1 and remained in the CPU under clinical supervision after administration of the investigational product on day 1 (part A and part B) and day 5 (part B) and were discharged after completion of the assessments on day 4 (part A) and day 9 (part B). Subjects returned to the CPU for follow-up assessments 7 to 10 days after the administration of the investigational product (part A) and the last dose of administration of the investigational product (part B).

(ii) Study treatments. In part A, each subject received a single oral dose as an oral suspension of zoliflodacin at 200, 400, 800, 1,600, 3,000, or 4,000 mg or a placebo in the fasted state (at least 10 h before the dose until 4 h after the dose). Within each dose cohort, six subjects received zoliflodacin and two subjects received placebo. In part B, eight subjects were included in cohort 1 (zoliflodacin at 1,500 mg) and 10 subjects in cohort 2 (zoliflodacin at 3,000 mg). All subjects received two single oral doses of zoliflodacin either in a fasted or fed state separated by a washout period of 4 days. In the fed state, subjects were dosed 30 min after the start of a high-fat breakfast (800 to 1,000 cal, with approximately 50% of total caloric content from fat). In the fasted state, subjects fasted at least 10 h before the dose and until 4 h after the dose.

(iii) Study assessments. During the inpatient period, subjects were asked to refrain from alcohol and consumption of foods known to enhance or limit metabolism to reduce the potential for PK interactions. In addition, subjects underwent routine assessments of blood pressure and heart rate, body temperature, physical examination, ECG, safety laboratory testing (hematology, chemistry, urinalysis), and blood (time points) and urine (time points) sampling for PK analysis. Urine collection intervals were −12 to 0 h and 0 to 4, 4 to 8, 8 to 12, 12 to 24, 24 to 48, and 48 to 72 h.

(iv) LC-MS/MS determination of zoliflodacin in plasma and urine. Concentrations of zoliflodacin in plasma and urine samples obtained in parts A and B of the phase 1 study were determined by a validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) assay following liquid-liquid extraction. Briefly, 50 μl of plasma or urine was added to 25 µl of zoliflodacin-stable label (internal standard; lot ETX-016359-01-02) solution (500 ng/ml in 50:50 methanol-water) in a 96-well plate. Fifty microliters of 0.2% formic acid in water was added and the 96-well plate covered and vortexed for 1 min. A 700-µl aliquot of tert-butylmethyl ether was added and mixed thoroughly. Phase separation was achieved by leaving plates undisturbed for 2 min, and 500 µl of the organic phase was transferred to another 96-well plate, evaporated to dryness at 40°C, and reconstituted in 100 μl of 50:50 methanol-water containing 0.2% formic acid and mixed thoroughly prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. Zoliflodacin and IS were analyzed on a Phenomenex Gemini C18 column (50 by 2.0 mm, 5 µm) using a gradient consisting of 0.2% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.2% formic acid in methanol-acetonitrile (50:50, vol/vol; solvent B). The gradient was initiated at 55% solvent B and ramped to 85% in 0.2 min. The eluent from the LC was split onto a Sciex API 5500 Q-Trap mass spectrometer operated in the positive ion mode. Multiple reaction monitoring transitions were 488.2→348.2 and 492.2→348.2 for zoliflodacin and internal standard, respectively. The assay had a dynamic range of 1.00 ng/ml (lower limit of quantification [LLOQ]) to 5,000 ng/ml for both plasma and urine. Analytical runs were considered acceptable if standards and fortified quality controls were within 15% accuracy (20% at the LLOQ) and incurred sample reproducibility (ISR) was within 20% upon reassay for two-thirds of samples added to each run.

For plasma, the mean accuracy for the assay ranged from 99.7 to 102.3% and the precision (percent relative standard deviation [%RSD]) ranged from 2.9 to 8.2%. For urine, the mean accuracy for the assay ranged from 94.5 to 104.0% and the precision (%RSD) ranged from 2.2 to 6.9%. All samples were analyzed within the stability window established for zoliflodacin (91 days).

(v) Noncompartmental PK analysis. Analysis for the PK parameters was performed using Phoenix WinNonlin v6.2.1 (Certara). PK parameters determined included AUC(0-∞), or area under plasma concentration-time curve from time zero extrapolated to infinity, AUC(0-last), or AUC from time zero to time of last quantifiable zoliflodacin concentration, AUC(0–24), or AUC from time zero to 24 h after dosing, Ae(0-t), or cumulative amount of the investigation product excreted unchanged into urine from zero to time t, CL/F, or apparent plasma clearance, CLR, or renal clearance, Cmax, Fe, or fraction of dose excreted unchanged into urine, Tmax, t1/2, Vz/F, or apparent terminal phase volume of distribution, and Vss/F, or apparent steady-state volume of distribution.

No formal statistical hypothesis testing was performed. CIs were calculated for descriptive purposes. Continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics (n, means, standard deviations [SD], minimum, median, and maximum). Categorical variables were summarized by actual dose group; data for placebo subjects were pooled across dose administration cohorts. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS, version 9.4.

For part B and at each dose level, a linear mixed-effects analysis of variance model using the natural logarithm of AUC and Cmax as the response variables, fixed effects for sequence, period, and treatment, and a random effect for subject nested within sequence was performed. The least-squares mean plus 95% CIs for each treatment and the difference between the treatments plus 90% CIs were estimated.

Mass balance study.

(i) Study design. This was an open-label, nonrandomized study to evaluate the mass balance, metabolite profiles, and rates and routes of elimination of zoliflodacin in six healthy adult volunteers. After an overnight fast of at least 8 h, a single 3,000-mg oral dose suspension of [14C]zoliflodacin (AZD0914) containing approximately 500 μCi (6.25 mrem) was administered (Selcia Limited, Essex, United Kingdom). The radiolabel dose was selected based upon rodent dosimetry studies and the need for sufficient sensitivity to support extensive metabolite profiling in excreta. The 6.25-mrem dose falls well below the 3,000-mrem limit established for humans by the FDA (https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM163892.pdf). Subjects were required to fast for at least 8 h prior to dosing until 4 h postdose.

(ii) Study assessments. Following single oral administration of [14C]zoliflodacin as an oral suspension, urine and feces were collected out to 168 h postdose. Urine collections were obtained and pooled at 0 to 6, 6 to 12, 12 to 24, and 24 to 48 h postdose. Feces were collected and pooled at 0 to 24, 24 to 48, 48 to 72, 72 to 96, 96 to 120, 120 to 144, and 144 to 168 h postdose. Radioactivity at each collection interval was assessed by liquid scintillation counting (LSC) of urine samples directly (50 μl) and through combustion of fecal samples prepared as a uniform homogenate in water. Radioactive counts were assessed in duplicate determinations and normalized to total radioactivity collected per interval, accounting for total weight. The total recovery of radioactivity (Fetot; percentage or fraction of administered radioactive dose recovered in urine and feces overall) was computed as the sum of the cumulative excretion in urine and feces across all collection periods.

(iii) Metabolite profiling of plasma, urine, and feces. Plasma samples obtained at 0.5, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h postdose were pooled across subjects evenly (0.5 ml) at each individual time point and then used to quantify metabolites at these individual time points. These data were used to calculate AUCs for [14C]zoliflodacin and individual metabolites. Briefly, 0.5 ml of pooled plasma was extracted with two 6-ml aliquots of acetonitrile, evaporated to dryness, and reconstituted in 5 ml of water prior to loading onto solid-phase extraction (SPE) columns (Dionex Solex C8, 6-ml barrel). Retained radioactivity on SPE columns was eluted with 5 ml of methanol and evaporated to dryness. Residues were reconstituted in 300 µl of 20 mM ammonium formate, pH 4.0, and acetonitrile (90:10), and recovery was assessed by liquid scintillation counting. Reconstituted residues were profiled by LC-MS/MS with eluent fraction collections made at 10-s intervals on a 96-well plate containing solid scintillant and counted via TopCount analysis. Urine was pooled to measure radioactivity excreted in that matrix. Pooled urine samples (∼2.0 g) were centrifuged at 18,000 × g prior to LC-MS/MS profiling and TopCount analysis. Fecal homogenates were pooled to recover >98% of radioactivity, a 2-g sample was extracted with 6 ml of methanol and centrifuged at 2,800 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in another 6 ml of methanol containing 0.2% (vol/vol) formic acid and centrifuged again. The supernatants were combined, evaporated to dryness, and reconstituted in 750 μl of 20 mM ammonium formate, pH 4.0, and methanol (70:30) prior to LC-MS/MS profiling and TopCount analysis.

(iv) Metabolite identification. Metabolites in urine, feces, and plasma extracts were profiled by LC-MS/MS using an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer. LC separation of metabolites was achieved on a Thermo Aquasil C18 (4.6 by 250 mm, 5 μm) column in line with a Phenomenex C18, 3- by 4-mm guard column utilizing a binary gradient of 20 mM ammonium formate, pH 4.0 (solvent A), and acetonitrile (solvent B). The gradient schedule was programmed at 90:10 (A:B) for 0 to 3 min; 80:20 for 17 min, 50:50 for 58 min, 10:90 for 82 min, 90:10 for 82.5 min, and 90:10 for 90 min. The LC flow rate was 1 ml/min. Simultaneous acquisition of radiochromatogram and high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry of [14C]zoliflodacin-related metabolites was performed as detailed in rodents (15). Product ion scans were acquired in the positive ion mode based upon isotopic pattern recognition and/or signal intensity in a total ion (Q1) scan. Source and capillary voltages were 5 kV and 44 V, respectively. Metabolite assignments followed the same numbering established in rodents and was verified by retention time and protonated mass.

(v) Additional analysis in mass balance/ADME study. Descriptive statistics (mean, median, SD, % coefficient of variation [CV], minimum, maximum, n, geometric mean, geometric %CV, and geometric n) were calculated for all concentration data. Safety was assessed from AEs, physical examinations, laboratory safety tests (hematology, coagulation, clinical chemistry, and urinalysis), vital signs, ECGs, and body weight. Phoenix WinNonlin, version 6.2.1, was used for PK analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the contributions of the AstraZeneca zoliflodacin early clinical development team, Michael E. Fitzsimmons and Mark R. Hoffman (Covance ADME profiling and bioanalysis), and the editorial assistance of Richard S. Perry in the development of the manuscript, which was supported by Entasis Therapeutics, Inc., Waltham, MA. This study was supported by Entasis Therapeutics, Inc., Waltham, MA. All authors performed data analysis and interpretation, as well as manuscript review and approval. All authors were paid employees of Entasis Therapeutics, Inc., Waltham, MA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Unemo M, Nicholas RA. 2012. Emergence of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and untreatable gonorrhea. Future Microbiol 7:1401–1422. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbee LA, Dombrowski JC. 2013. Control of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the era of evolving antimicrobial resistance. Infect Dis Clin North Am 27:723–737. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. CDC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. 2016. Guidelines for the treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basarab GS, Doig P, Galullo V, Kern G, Kimzey A, Kutschke A, Newman JP, Morningstar M, Mueller J, Otterson L, Vishwanathan K, Zhou F, Gowravaram M. 2015. Discovery of novel DNA gyrase inhibiting spiropyrimidinetriones: benzisoxazole fusion with N-linked oxazolidinone substituents leading to a clinical candidate (ETX0914). J Med Chem 58:6264–6282. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huband MD, Bradford PA, Otterson LG, Basarab GS, Kutschke AC, Giacobbe RA, Patey SA, Alm RA, Johnstone MR, Potter ME, Miller PF, Mueller JP. 2015. In vitro antibacterial activity of AZD0914, a new spiropyrimidinetrione DNA gyrase/topoisomerase inhibitor with potent activity against Gram-positive, fastidious Gram-negative, and atypical bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:467–474. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04124-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kern G, Palmer T, Ehmann DE, Shapiro AB, Andrews B, Basarab GS, Doig P, Fan J, Gao N, Mills SD, Mueller J, Sriram S, Thresher J, Walkup GK. 2015. Inhibition of Neisseria gonorrhoeae type II topoisomerases by the novel spiropyrimidinetrione AZD0914. J Biol Chem 290:20984–20994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.663534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basarab GS, Kern GH, McNulty J, Mueller JP, Lawrence K, Vishwanathan K, Alm RA, Barvian K, Doig P, Galullo V, Gardner H, Gowravaram M, Huband M, Kimzey A, Morningstar M, Kutschke A, Lahiri SD, Perros M, Singh R, Schuck VJ, Tommasi R, Walkup G, Newman JV. 2015. Responding to the challenge of untreatable gonorrhea: ETX0914, a first-in-class agent with a distinct mechanism-of-action against bacterial type II topoisomerases. Sci Rep 5:11827. doi: 10.1038/srep11827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foerster S, Golparian D, Jacobsson S, Hathaway LJ, Low N, Shafer WM, Althaus CL, Unemo M. 2015. Genetic resistance determinants, in vitro time-kill curve analysis and pharmacodynamic functions for the novel topoisomerase II inhibitor ETX0914 (AZD0914) in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Front Microbiol 6:1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papp JR, Lawrence K, Sharpe S, Mueller J, Kirkcaldy RD. 2016. In vitro growth of multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates is inhibited by ETX0914, a novel spiropyrimidinetrione. Int J Antimicrob Agents 48:328–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biedenbach DJ, Huband MD, Hackel M, de Jonge BL, Sahm DF, Bradford PA. 2015. In vitro activity of AZD0914, a novel bacterial DNA gyrase/topoisomerase IV inhibitor, against clinically relevant Gram-positive and fastidious Gram-negative pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6053–6063. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01016-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Alm RA, Huband M, Mueller J, Jensen JS, Ohnishi M, Unemo M. 2014. High in vitro activity of the novel spiropyrimidinetrione AZD0914, a DNA gyrase inhibitor, against multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates suggests a new effective option for oral treatment of gonorrhea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:5585–5588. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03090-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alm RA, Lahiri SD, Kutschke A, Otterson LG, McLaughlin RE, Whiteaker JD, Lewis LA, Su X, Huband MD, Gardner H, Mueller JP. 2015. Characterization of the novel DNA gyrase inhibitor AZD0914: low resistance potential and lack of cross-resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1478–1486. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04456-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unemo M, Ringlander J, Wiggins C, Fredlund H, Jacobsson S, Cole M. 2015. High in vitro susceptibility to the novel spiropyrimidinetrione ETX0914 (AZD0914) among 873 contemporary clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from 21 European countries from 2012 to 2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:5220–5225. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00786-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo J, Joubran C, Luzietti RA Jr, Basarab GS, Grimm SW, Vishwanathan K. 2017. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination of 14C-ETX0914, a novel inhibitor of bacterial type-II topoisomerases in rodents. Xenobiotica 47:31–49. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2016.1156186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unemo M, Del Rio C, Shafer WM. 2016. Antimicrobial resistance expressed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a major global public health problem in the 21st century. Microbiol Spectr 4:EI10-0009-2015. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.EI10-0009-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefebvre B, Martin I, Demczuk W, Deshaies L, Michaud S, Labbé A-C, Beaudoin M-C, Longtin J. 2018. Ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Canada, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis 24:eid2402.171756. doi: 10.3201/eid2402.171756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkcaldy RD, Harvey A, Papp JR, Del Rio C, Soge OO, Holmes KK, Hook EW, Kubin G, Riedel S, Zenilman J, Pettus K, Sanders T, Sharpe S, Torrone E. 2016. Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance–the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, 27 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 65:1–19. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6507a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]