Key Points

miR-22 knockout impairs megakaryocytic differentiation, whereas differentiation is promoted by miR-22 overexpression.

miR-22 is a driver of megakaryopoiesis through direct repression of GFI1, a repressive transcription factor antagonistic to this process.

Abstract

Precise control of microRNA expression contributes to development and the establishment of tissue identity, including in proper hematopoietic commitment and differentiation, whereas aberrant expression of various microRNAs has been implicated in malignant transformation. A small number of microRNAs are upregulated in megakaryocytes, among them is microRNA-22 (miR-22). Dysregulation of miR-22 leads to various hematologic malignancies and disorders, but its role in hematopoiesis is not yet well established. Here we show that upregulation of miR-22 is a critical step in megakaryocyte differentiation. Megakaryocytic differentiation in cell lines is promoted upon overexpression of miR-22, whereas differentiation is disrupted in CRISPR/Cas9-generated miR-22 knockout cell lines, confirming that miR-22 is an essential mediator of this process. RNA-sequencing reveals that miR-22 loss results in downregulation of megakaryocyte-associated genes. Mechanistically, we identify the repressive transcription factor, GFI1, as the direct target of miR-22, and upregulation of GFI1 in the absence of miR-22 inhibits megakaryocyte differentiation. Knocking down aberrant GFI1 expression restores megakaryocytic differentiation in miR-22 knockout cells. Furthermore, we have characterized hematopoiesis in miR-22 knockout animals and confirmed that megakaryocyte differentiation is similarly impaired in vivo and upon ex vivo megakaryocyte differentiation. Consistently, repression of Gfi1 is incomplete in the megakaryocyte lineage in miR-22 knockout mice and Gfi1 is aberrantly expressed upon forced megakaryocyte differentiation in explanted bone marrow from miR-22 knockout animals. This study identifies a positive role for miR-22 in hematopoiesis, specifically in promoting megakaryocyte differentiation through repression of GFI1, a target antagonistic to this process.

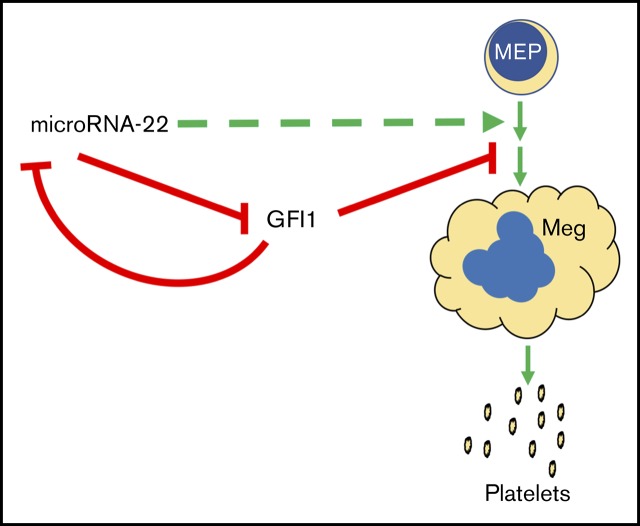

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Platelets are circulating, anucleate cellular fragments involved in clotting. Adult humans produce ∼1011 platelets from bone marrow megakaryocytes (MKs) daily.1 MKs are massive polyploid cells that undergo rounds of endomitosis, expansion of their cytoplasm, and extension of proplatelet membrane projections into bone marrow sinusoids.2,3 In addition to their role in platelet formation, platelet- and myeloid-biased hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)4 reside in close proximity to MKs, which regulate HSC quiescence through cytokine signaling, making them crucial components of the HSC niche.5-9 The hierarchical process by which HSCs yield MKs10-13 is the subject of debate due to new evidence from lineage-tracing and transplantation studies for direct differentiation from MK-biased HSCs and from unipotent MK progenitors.14-22 However, MK-promoting cytokine signaling and gene expression pathways are well characterized, and a number of transcription factors, such as GATA1, FOG1, GFI1B, FLI1, and RUNX1/AML1, have been shown to contribute to megakaryopoiesis.23-25

microRNAs (miRNAs) are small, ∼22 nucleotide, noncoding, single-stranded RNAs that participate in development, the establishment of tissue identity, and stem cell differentiation in the course of normal physiology26 and contribute to disease upon their dysregulation.27 In postembryonic cells, miRNAs repress targets posttranscriptionally through sequence-specific binding to messenger RNA (mRNA), primarily resulting in transcript degradation.28,29 Although numerous miRNAs have been implicated in hematopoietic differentiation and hematologic disease, and miRNA profiling studies have been carried out in MK differentiation in various systems,30-32 most differentially expressed miRNAs are downregulated upon MK differentiation. Only a small number of miRNAs have been shown to positively contribute to MK differentiation,33-36 such as the upregulation of miR-150, which promotes MK differentiation through repression of the MYB transcription factor, itself antagonistic to MK lineage choice.34 microRNA-22 (miR-22) is among those few miRNAs found to be upregulated in ex vivo differentiated MKs derived from murine fetal liver30 and is upregulated upon megakaryocytic differentiation of the bipotent human erythroleukemia cell line, K56237-40; however, its role in megakaryopoiesis has not been explored.

In humans, miR-22 is encoded in its own gene (MIR22HG) on chromosome 17.41 miR-22 is a protooncogene, and its upregulation has been shown to contribute to the development of myelodysplastic syndrome through repression of the epigenetic regulator Ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 2, which is frequently mutated in hematologic malignancy.42 Complicating matters, miR-22 has been implicated in promoting monocytic differentiation in various culture systems43 and is tumor suppressive in acute myeloid leukemia (AML),44 and recently, miR-22 has been shown to limit erythroid maturation and promote the interferon response in viral-challenge.45

Here, we show that miR-22 is dramatically upregulated upon megakaryocytic differentiation in adult mice. In cell lines, megakaryocytic differentiation is driven by overexpression of miR-22 and is inhibited by its loss. miR-22’s role in this process is mediated through direct targeting of the zinc-finger transcriptional repressor, GFI1, which is dysregulated in miR-22KO animals. This work expands the repertoire of miR-22’s functions in the hematopoietic system by establishing a new role for miR-22 in MK differentiation and expands the class of miRNAs that promote megakaryopoiesis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

K562 cells were cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher) was used for transient transfection of K562 for miR-22 overexpression and luciferase assays according to the recommended protocol.

CRISPR knockout of miR-22

miR-22 was knocked out in K562 cells using CRISPR-genome editing.46 Guide RNAs (gRNAs) were designed to flank the 85-bp pre–miR-22 hairpin (total length, ∼375 bp). gRNAs were expressed from pU6-sgRNA-EF1α-puro-T2A-BFP47 (Addgene). Oligos, sequencing primers, and genotyping primers are available in supplemental Table 1.

K562 cells were nucleofected with gRNA expression vectors and pL-CRISPR.SFFV.tRFP48 (Addgene). After 48 hours, bright BFP+RFP+ cells were fluorescence activated cell sorted (FACS) and deposited as single cells into 96-well U-bottom plates. After 14 days, gDNA (QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution; EpiCenter) was subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping, using forward and reverse primers external to the deletion, and a reverse primer internal to the deletion. Six wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous miR-22KO clones were assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for miR-22 expression.

qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using the microRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). For mRNA, reverse transcription (RT) was performed with the SuperScript III First-Strand cDNA Synthesis System using oligo(dT)20 primers (Thermo Fisher). For miRNA, RT was performed using the TaqMan microRNA RT Kit (Thermo Fisher). qPCR was carried out using TaqMan Universal Master Mix II, no UNG (Thermo Fisher), using the Applied Biosystems Viia 7 Real-Time PCR System, 384-well format. Relative quantitation was calculated in the Thermo Fisher Cloud, with values adjusted using GUSB, ActB, or sno202 controls. qPCR primers are found in supplemental Table 2.

RNA sequencing and computational analysis

Sample isolation.

Total RNA was extracted from the following samples: K562:CRISPR-Scramble, n = 3; and K562:miR-22KO, n = 3.

Sequencing.

mRNA-sequencing libraries were analyzed on Illumina HiSeq, Paired End, 150-bp configuration. Data sets are reposited in the Sequence Read Archive (#SRP149845).

Data analysis.

Sequences were aligned to the hg19 genome using STAR (2.5.2b) and converted to BAM files and indexed using Picard Tools (2.3.0). Sequencing duplicates were removed using Samtools (1.4.1).49 Gene expression and statistical analysis were conducted in R Studio (DESeq2).50 The top 30% of predicted targets from TargetScan51 of hsa-miR-22-3p were identified in R (multimiR).52

PMA-differentiation of K562

Megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells was achieved by treating with phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA; Sigma) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).53 Cells were seeded at 3 × 105 cells per milliliter with 75 nM PMA or vehicle for 48 to 72 hours, unless otherwise specified. Megakaryocytic differentiation was quantified by measuring CD61 surface marker expression and ploidy by flow cytometry.

CRISPRi knockdown of putative miR-22 targets

For highly efficient knockdown of putative miR-22 targets, we used CRISPR-inhibition (CRISPRi).47 K562 cells were transduced with pHR-SFFV-KRAB-dCas9-P2A-mCherry (Addgene) and were expanded and FACS 4 times to achieve a stable, pure, polyclonal population. gRNAs targeting promoters of specific genes were identified47 and expressed from pU6-sgRNA-EF1α-puro-T2A-BFP (supplemental Table 1), and transduced cells were puromycin selected. Knockdown of targets was confirmed by qPCR and by immunoblot in the case of GFI1.

Immunoblotting for GFI1

Total protein was isolated from K562 cells under various treatment conditions using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 1× Proteinase Inhibitor (Roche). GFI1 was stained with anti-GFI1 polyclonal antibody (Rabbit pAb-GFI1, abcam #ab21061), and specific binding was confirmed by GFI1 knockdown. Blots were visualized using secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorophores (LiCor IRDye) or to horseradish peroxidase using chemiluminescence (Western-Lighting Plus-ECL) on the LiCor Odyssey. Image analysis and quantitation were performed using Image Studio Lite (5.2.5).

Luciferase assay

For quantitation of miR-22 binding to the GFI1 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) in K562, we generated nanoLuciferase (nanoLuc) constructs harboring predicted miR-22 binding sites from the GFI1 3′-UTR or poly-T tract-nontargeted controls54 by ligating oligos (supplemental Table 1) into pNL1.1.TK[Nluc/TK] (Promega). nanoLuc reporters were cotransfected with pGL4.53[luc2/PGK] (Promega), as a transfection control, into K562:wildtype and K562:miR-22KO cells using Lipofectamine 2000. After 48 hours, transfected cells were analyzed using the Nano-Glo Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) on the SpectraMax M3 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices).

Mice

129S-Mir22tm1.1Arod/J mice55 were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Heterozygotes were bred to obtain wildtype, heterozygous, and homozygous miR-22KO. For all experiments, age- and sex-matched mice, aged 3 to 6 months, were euthanized, followed by immediate isolation of bone marrow from femurs and tibias. Littermates were preferred when available. Peripheral blood was collected from the tail vein for complete blood counts (Advia 120 System) and flow cytometric analysis. All animal experiments were approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Ex vivo differentiation assays

MegaCult assay.

For analysis of murine MKs (colony-forming unit [CFU]-MK) in collagen-based assays, 1000 sorted c-Kit+Sca1+Lineage− (KSL) were plated in MegaCult (Stem Cell Technologies), supplemented with collagen and cytokines (recombinant human thrombopoietin; 50 ng/mL; rmIL-3, 20 ng/mL; rmIL-6, 50 ng/mL; and rmIL-11, 10 ng/mL, PeproTech). After 7 days, cultures were dehydrated and stained for acetylcholinesterase. Cultures were scored for CFU-MK and non-MK colonies by a blinded counter on 2 separate days.

Liquid culture of MKs.

Bone marrow mononuclear cells were cultured for 5 days in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 50 ng/mL recombinant human thrombopoietin at 1 to 5 × 107 cells per milliliter. Ploidy was assessed by flow cytometry. For qPCR, MKs were isolated using a 2-step bovine serum albumin (Sigma) density gradient,56 and samples were subjected to cytospin (StatSpin Cytofuge 2; Beckman Coulter) and acetylcholinesterase staining. Unfractionated cultures were subjected to cytospin for assessment of MK frequency and size, and CD41 expression was assessed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Surface markers used to label various cell types are found in supplemental Table 3. Data collection was conducted on the LSR II (BD Biosciences). Cell sorting was conducted using the FACS Aria IIu (BD Biosciences). For nuclear content staining, live cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies). Otherwise, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) live/dead staining was used. For the analysis of apoptosis, K562 cells were stained with the Annexin V– allophycocyanin and propidium iodide (BioLegend), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Analysis was conducted in FlowJo, v10 (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise specified, the unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test was applied. Results equal to or above a 95% confidence interval (P ≤ .05) were considered statistically significant. Unless P values are specifically identified, they are notated as follows: not statistically significant (ns) ≥.05, *.01 to ≤.05, **.001 to <.01, ***.0001 to <.001, ****≤.0001. Unless otherwise specified, error bars represent standard deviation.

Results

miR-22 contributes to megakaryocytic maturation in an in vitro model of differentiation

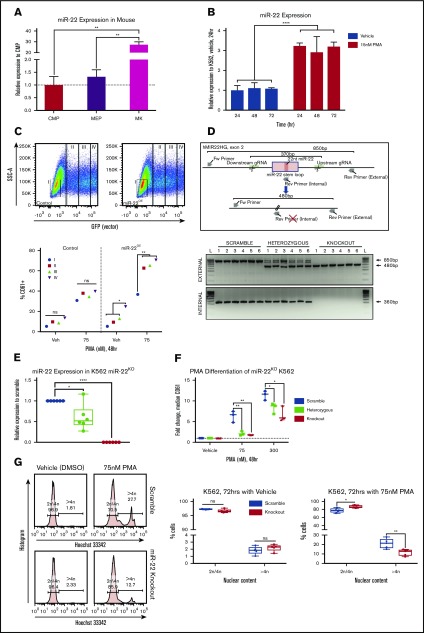

Upregulation of miR-22 has previously been demonstrated upon ex vivo MK differentiation from mouse fetal liver–derived cells.30 Previous sequencing studies57 demonstrate that miR-22-3p is the predominant miR-22 strand, which holds true in human K562 cells and in the mouse megakaryocytic lineage (supplemental Figure 1A). We demonstrated that miR-22-3p expression is upregulated ∼20-fold in terminally differentiated MKs as compared with megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) in vivo in adult 129SV mice (Figure 1A). To assess if miR-22 behaves similarly in human megakaryopoiesis and to establish a system for miR-22 modulation and mechanistic studies, we turned to a proven model of MK differentiation in the human erythroleukemia line, K562.37,38 K562 cells are bipotent undifferentiated cells capable of erythroid differentiation when treated with hemin, or megakaryocytic differentiation when treated with PMA. Furthermore, miR-22 expression has been shown to be upregulated in terminal differentiation of K562 and other hematopoietic cell lines after treatment with PMA.40 We confirmed this and observed a greater than threefold upregulation of miR-22 upon treatment of K562 cells with PMA over 72 hours (Figure 1B). Transfection with an miR-22 encoding plasmid results in increased miR-22 expression that is correlated with GFP expression (supplemental Figure 1B). Overexpression of miR-22 results in increased megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells, as measured by increased expression of the platelet glycoprotein CD61, in the presence and absence of PMA (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 1C), and a 20% increase in high-ploidy cells upon PMA differentiation (supplemental Figure 1D), suggesting that miR-22 is an important driver of megakaryocytic differentiation.

Figure 1.

miR-22 expression increases upon terminal MK maturation and drives the maturation process. (A) Bone marrow from individual wildtype 129SV mice was stained according to surface markers listed in supplemental Table 3 and DAPI for live/dead assessment. Common myeloid progenitor (CMP), MEP, and MK were sorted by FACS for analysis of miR-22-3p expression by qPCR. sno202 was used as a housekeeping gene to quantify relative expression. Expression is shown relative to CMP, with the dotted line showing Relative Expression = 1. Data represent 2 independent experiments, performed in triplicate. (B) Representative qPCR for miR-22 in K562 cells treated with 15 nM PMA over time. K562 cells are driven to megakaryocytic differentiation. sno202 was used as a housekeeping gene to quantify relative expression. Expression is shown relative to K562 treated with vehicle (Veh; DMSO) at 24 hours. For the statistical analysis, the time points were treated as replicates. (C) miR-22 overexpression promotes MK maturation. K562 cells were transiently transfected with an miR-22 overexpression vector (PIG/miR-2242) or a control (PIG/empty) and were subjected to PMA-driven megakaryocytic differentiation. GFP expression was used as a correlate for miR-22 overexpression and gated from I, no miR-22 overexpression, to IV, highest miR-22 overexpression (upper). Quantitation of percentages of CD61+ cells upon differentiation with 75 nM PMA or vehicle treatment and escalating empty vector or miR-22 expression (lower). (D) Utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 to knockout the miR-22 encoding stem loop from the MIR22HG in K562 cells. Schematic of the human MIR22HG on chromosome 17, specifically exon 2, which encodes the miR-22 stem loop (upper). Predicted schematics before and after locus excision and repair are shown, as well as gRNAs and genotyping primers. Agarose genotyping gel shows isolation of 6 clones each of scramble (ie, wildtype), miR-22 heterozygous, and miR-22 knockout (lower). Excision is identified by appearance of the truncated ∼480-bp band (external primers) and loss of the ∼360-bp band (internal primers). (E) qPCR for miR-22 expression in wildtype (ie, Scramble), miR-22 heterozygous, and miR-22 knockout K562 clones. sno202 was used as a housekeeping gene to quantify relative expression. Expression is shown relative to Scramble (n = 6). (F-G) K562:miR-22KO clones were subjected to PMA-driven megakaryocytic differentiation and assayed for differentiation by CD61 expression and nuclear content (ie, increased ploidy). (F) PMA-driven megakaryocytic differentiation over 48 hours in K562:miR-22KO clones was assessed by flow cytometry for CD61 expression and reported as fold change in median CD61 expression normalized per clone (n = 3). (G) PMA-driven megakaryocytic differentiation over 72 hours in K562:miR-22KO clones. Frequency of high-ploidy cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Gating strategy for identifying high-ploidy cells is shown (left) and is quantified in K562:Scramble and K562:miR-22KO clones (right) (n = 5). GFP, green fluorescent protein; SSC-A, side-scatter area. *P ≤ .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001.

In order to demonstrate that miR-22 contributes to megakaryocytic differentiation at its endogenous levels, we knocked out the pre-miR-22 containing stem-loop in the MIR22HG of K562 cells using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. miR-22 wildtype, heterozygous and homozygous knockout clones were identified by PCR and confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 1D). miR-22 heterozygous clones express an intermediate level of miR-22, which was undetectable in knockout clones (Figure 1E). miR-22 heterozygous and knockout K562 cells are impaired in PMA-driven megakaryocytic differentiation, as measured by CD61 expression, even at high concentrations of PMA (Figure 1F). Furthermore, miR-22 loss results in a twofold reduction of high-ploidy cells upon PMA treatment of K562:miR-22KO cells, indicating a defect in endoreplication consistent with disrupted differentiation (Figure 1G). K562:miR-22KO cells displayed accelerated growth kinetics as compared with wildtype, indicating a reduced rate of spontaneous differentiation in the absence of PMA treatment (supplemental Figure 1E). Neither overexpression nor knockout of miR-22 increased the susceptibility of K562 cells to apoptosis when treated with PMA (supplemental Figures 1F-G).

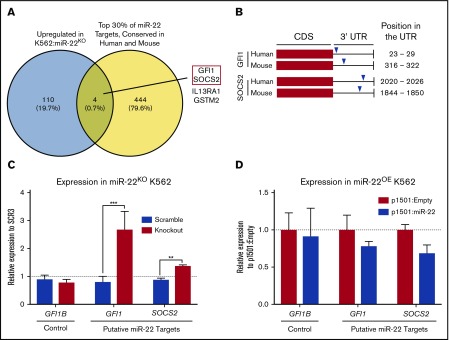

RNA-sequencing identifies putative targets of miR-22

To identify putative targets of miR-22 responsible for its effect on megakaryocytic differentiation, we subjected K562:miR-22KO cells to expression profiling by RNA sequencing. To restrict our analysis to likely direct targets of miR-22, we identified the top 30% of TargetScan51 predicted miR-22-3p targets conserved between human and mouse using multimiR.52 This analysis identified 4 genes suitable for further study (Figure 2A), from which we identified a transcription factor58 and an inhibitor of cytokine signaling,59 both of which have been implicated in hematopoietic or megakaryocytic differentiation, for assessment as miR-22 targets that might mediate its role in megakaryocytic differentiation (Figure 2A red box). These genes, GFI1 (Growth factor independent 1) and SOCS2 (Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2), have conserved miR-22-3p seed sequences in their 3′-UTRs, in human and mouse (Figure 2B). qPCR confirms upregulation of GFI1 and SOCS2 in K562:miR-22KO cells (Figure 2C) and downregulation of these putative targets in K562:miR-22OE cells (Figure 2D). We also examined expression of GFI1B, a paralog of GFI1 that does not contain an miR-22 seed sequence, as a nontargeted control. RNA-sequencing and qPCR in MEPs from miR-22 knockout animals also supported the further examination of these putative targets (not shown).

Figure 2.

Identification of putative targets of miR-22 that may mediate its effect on megakaryopoiesis. (A) Venn diagram showing the strategy for selecting putative targets of miR-22 from RNA-sequencing data. K562:scramble and K562:miR-22KO were subjected to total RNA isolation, library preparation, and RNA-sequencing and analysis. To identify putative direct targets of miR-22, all targets needed to contain miR-22 seed sequences conserved in human and mouse; the yellow circle represents the top 30% of predicted TargetScan51 targets from the multimiR package (R). The blue circle represents genes upregulated in K562:miR-22KO cells, as would be expected of direct targets of miR-22. Four putative miR-22 targets were identified. The 2 chosen for further study are outlined in red. (B) Schematic showing the locations of predicted miR-22 seed sequences in human and mouse in the 3′-UTRs of the genes chosen for further study. (C-D) qPCR to confirm dysregulation of putative miR-22 targets chosen for future study in K562:miR-22KO cells (n = 3) (C). Expression is shown relative to scramble clone SCR3. (D) qPCR to confirm dysregulation of putative miR-22 targets chosen for future study miR-22 overexpressing cells. Expression is shown relative to p1501:Empty. GUSB was used as a housekeeping gene to quantify relative expression. **P < .01; ***P < .001. CDS, coding sequence.

In addition, DAVID analysis60 of Gene Ontology in K562:miR-22KO cells revealed that platelet-associated genes are enriched among those genes downregulated upon miR-22KO, with platelet-derived growth factor signaling-associated genes being the most enriched in the set, consistent with the observed differentiation defect (supplemental Figure 2A). Functional annotation clustering across ontological databases also identified erythroid- and platelet-associated genes as enriched in downregulated genes in K562:miR-22KO (not shown).

GFI1 is a direct target of miR-22 during megakaryocytic differentiation

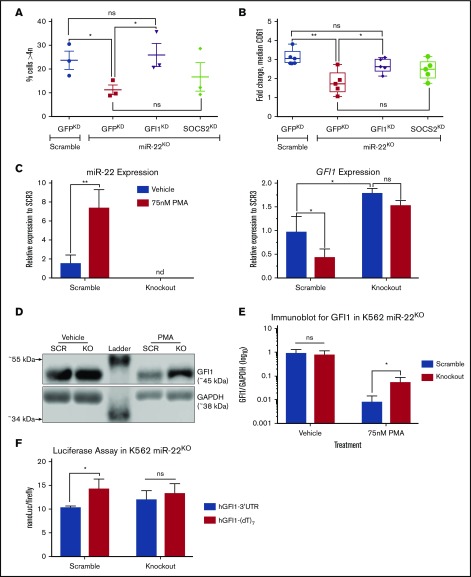

We used CRISPRi47 to knockdown the putative miR-22 targets in the context of miR-22KO to determine which might rescue megakaryocytic differentiation. We generated stable polyclonal K562:miR-22KO cells expressing the KRAB-dCas9 repressive protein, which were then transduced with specific gRNAs against putative targets. CRISPRi achieved >85% reduction of targets as measured by qPCR (supplemental Figure 3A) and >90% reduction as measured by immunoblot in the case of GFI1 (supplemental Figure 3B). In K562:miR-22KO cells, knockdown of GFI1 restored differentiation when measured by cell ploidy (Figure 3A) and as measured by CD61 expression (Figure 3B). However, knockdown of SOCS2 did not rescue differentiation; thus, we pursued the effect of miR-22 on GFI1.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of miR-22 targets rescues the MK differentiation defect that results from miR-22 loss. (A-B) We used the CRISPRi (CRISPR interference) approach for knockdown of putative miR-22 target genes in K562:miR-22KO. K562:scramble and K562:miR-22KO cell lines were transduced with lentivirus encoding KRAB:dCas9-P2A-mCherry. The KRAB-dCas9 fusion protein is a strong transcriptional repressor that can be targeted by gRNAs to specific sites in the genome. A GFP targeting gRNA was used as a control. Putative miR-22 targets were knocked down by CRISPRi in K562:scramble and K562:miR-22KO cells, and cells were driven toward megakaryocytic differentiation by treatment with PMA. Extent of differentiation is quantified by DNA content/ploidy (n = 3) (A), and median CD61 expression (n = 5) (B). (C-E) Megakaryocytic differentiation of K562:scramble and K562:miR-22KO cells by treatment with PMA and assayed for transcript and protein expression. (C) qPCR for miR-22 and GFI1 upon PMA-induced megakaryocytic differentiation. sno202 and GUSB were used as housekeeping genes to quantify relative expression, respectively. Expression is shown relative to scramble clone SCR3 (n = 3). (D) Representative immunoblot against GFI1 in K562:miR-22KO cells upon PMA-induced megakaryocytic differentiation and in vehicle-treated control. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an endogenous loading control. (E) Quantitation of immunoblot against GFI1 in K562:miR-22KO cells upon PMA-induced megakaryocytic differentiation and in vehicle treated control. GAPDH was used as an endogenous loading control to quantitate relative expression. Quantified blot is included in supplemental Figure 3C (n = 3). (F) The miR-22 seed sequence containing portion of the GFI1 3′-UTR or a nontargeted control in which the seed sequence was replaced with poly-T tract was cloned downstream of the nanoLuciferase (nanoLuc) gene. The nanoLuc expression vectors were transiently cotransfected with a firefly luciferase expression vector into K562:scramble and K562:miR-22KO cells, and luminescence was quantified after 48 hours using the Nano-Glo Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System. Quantitation is luminescence of nanoLuc (experimental vector) over luminescence of firefly luciferase (transfection control) (n = 3). (dT)7, poly-T tract; KO, knockout; SCR, scramble. *P ≤ .05; **P < .01.

Although GFI1 levels are reduced upon PMA-driven megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells, GFI1 expression persisted in PMA-treated K562:miR-22KO cells (Figure 3C right). Immunoblot confirmed that GFI1 protein expression is >6.5-fold higher in K562:miR-22KO cells upon differentiation (Figure 3D-E; supplemental Figure 3C).

To demonstrate direct interaction of miR-22 and the GFI1 3′-UTR, we developed a reporter with the miR-22 seed sequence-containing portion of the UTR downstream of nanoLuc, which was sensitive to treatment with miR-22 mimics (supplemental Figure 3D). As compared with the nontargeted control, nanoLuc activity is reduced in K562 cells expressing the GFI1 3′-UTR reporter at endogenous miR-22 levels, and this effect is abrogated in miR-22KO (Figure 3F). We could not detect any effect of miR-22 on the nanoLuc reporters harboring fragments of the SOCS2 3′-UTRs (not shown).

Previous reports suggest that GFI1 expression is modulated by miRNA targeting of its 3′-UTR in lymphocytes.61 Of the miR-22 targets identified from RNA-sequencing, only knockdown of GFI1 restored MK differentiation in the context of miR-22KO, and only the GFI1 3′-UTR responded to miR-22 levels.

miR-22 and GFI1 form an autoregulatory loop in K562 cells

GFI1 and its paralog GFI1B are transcription factors.58 The N-termini, common to both paralogs, contain a repressive SNAIL/GFI1 (SNAG) domain, which is responsible for recruiting histone-modifying enzymes.62,63 The C-termini, also common to both paralogs, contain 6 zinc-finger domains responsible for binding the GFI1/GFI1B AATC core recognition sequence.64 An intermediate domain is variable between the 2 paralogs and is thought to mediate additional protein-protein interactions. Both paralogs are critically important to hematopoiesis. Expression studies of GFI1 and GFI1B have revealed that they have largely nonoverlapping expression in the hematopoietic system, and knockout studies result in variable effects in different cell types. GFI1 maintains HSC quiescence,65,66 contributes to neutrophil differentiation,67,68 and has various effects on lymphoid development.58

Recently, Jiang et al identified a GFI1 recognition site in the promoter of MIR22HG and described downregulation of miR-22 through epigenetic silencing by GFI1-recruited TET1, putting GFI1 upstream of miR-22.44 We sought to disrupt the GFI1 recognition site in the MIR22HG promoter (supplemental Figure 4A). Using CRISPR-mediated homology-directed repair, we generated clones harboring minute, 2-base, disruptions to the GFI1 core-recognition motif (supplemental Figure 4B-C). miR-22 expression was increased ∼50% upon disruption of the GFI1 site (supplemental Figure 4D). Similarly, CRISPRi knockdown of GFI1 results in an ∼25% increase in miR-22 expression in K562:KRAB-mCherry+ cells (supplemental Figure 4E). The observation that miR-22 represses GFI1 and that disruption of the GFI1 recognition motif in the MIR22HG promoter results in increased miR-22 expression suggests that miR-22 and GFI1 participate in an autoregulatory loop whereby they increase their own expression through repression of their repressors.

miR-22 knockout mice exhibit a defect in megakaryopoiesis

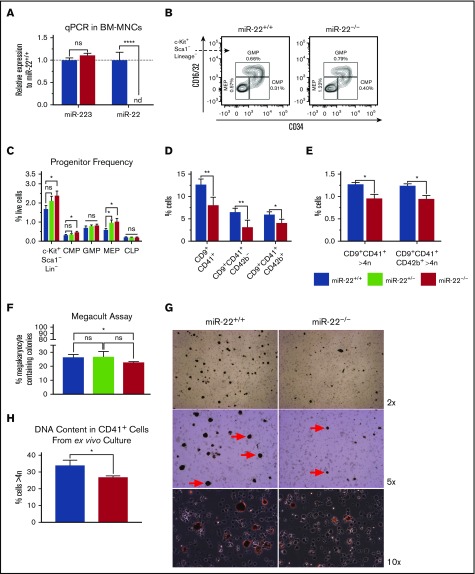

To determine if miR-22 plays a role in MK differentiation in mice, we assayed the bone marrow of miR-22KO animals55 for primary defects in megakaryopoiesis. As expected, miR-22 is not expressed in the bone marrow of miR-22KO animals (Figure 4A). Complete blood counts of miR-22KO animals at steady state did not reveal any changes in red blood cells, hematocrit or hemoglobin (supplemental Figure 5A), white blood cells (supplemental Figure 5B), or platelet number (supplemental Figure 5C). However, we did detect a decrease in mean platelet volume (supplemental Figure 5D), which has been associated with decreased ploidy of bone marrow MKs in human patients,69 consistent with an MK differentiation defect. There was no change to bone marrow cellularity (supplemental Figure 5E), mature cell types (supplemental Figure 5F), or hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, except for a slight increase in CD150+CD48−CD135−KSL cells (supplemental Figure 5G). Knowing that miR-22 expression increases in MK differentiation30 and having observed defective megakaryocytic differentiation upon knockout of miR-22 in human cell lines, we were intrigued by a 75% increase in the frequency of MEP in miR-22KO animals (Figure 4B-C). In addition, miR-22KO animals were found to have ∼30% fewer CD9+CD41+ MKs, attributable to a decrease in the number of immature MKs (CD9+CD41+CD42b−) and mature platelet-primed MKs (CD9+CD41+CD42b+) (Figure 4D).70 Both populations had ∼25% fewer high-ploidy cells, demonstrating an MK maturation defect (Figure 4E). Although we did not detect any changes to megakaryocyte progenitor or PreMegE frequency (supplemental Figure 5H), when explanted multipotent progenitors (MPP KSL) were subjected to the MegaCult assay, we detected a 15% decrease in MK-containing colonies in miR-22KO animals (Figure 4F), primarily due to a decrease in mixed MK-containing colonies (supplemental Figure 5I).

Figure 4.

miR-22 knockout mice exhibit an expansion of MK-erythrocyte progenitors and a defect in MK maturation. (A-C) Bone marrow from adult 129SV;miR-22 wildtype, heterozygous, and homozygous knockouts was isolated and subjected to analysis for gene expression, flow cytometric analysis, and ex vivo megakaryocytic differentiation. (A) Total RNA was isolated from bone marrow from wildtype and miR-22KO animals. RT was carried out using miRNA-specific primers. miR-223 was assayed as a control. sno202 was used as a housekeeping gene to quantify relative expression between samples (n = 3). (B) Bone marrow mononuclear cells from individual mice were stained for progenitors (CLP, CMP, GMP, and MEP) according to surface markers listed in supplemental Table 3, and DAPI for live/dead assessment. Shown are representative flow cytometry plots gated for myeloid progenitors from c-Kit+Sca1−Lineage− cells in wildtype and miR-22KO animals. (C) Quantitation of flow cytometric analysis of hematopoietic progenitor cells from wildtype, heterozygous, and miR-22KO animals (n = 6-9). (D-E) Bone marrow mononuclear cells from individual mice were stained for immature (CD9+CD41+CD42b−) and mature (CD9+CD41+CD42b+) MKs, and for DNA content. Quantitation of frequency of immature and mature MKs (D), and quantitation of the frequency of high-ploidy cells in mature MKs (n = 3) (E). (F) CFU-MK assays. One thousand KSL were isolated from individual wildtype, heterozygous, and miR-22KO animals by FACS and were plated in 1.7 mL MegaCult supplemented with collagen and cytokines and plated in covered chamber slides for culture. After 7 days, cultures were dehydrated in acetone and stained for acetylcholinesterase and counterstained with Harris’ hematoxylin. CFU-MK and non-MK were quantified by a blinded counter on 2 separate days, and counts were averaged (n = 3). (G-H) Ex vivo MK differentiation of primary miR-22KO bone marrow cells. Bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated from individual adult 129SV:miR-22 wildtype and miR-22KO and were subjected to ex vivo MK differentiation by treatment with TPO. Whole cultures were used for flow cytometry and acetylcholinesterase staining. (G) Representative microscopic images of acetylcholinesterase-stained cytospins from unfractionated ex vivo MK differentiation cultures. MKs are stained brown. Red arrows show MKs at 5× magnification. (H) Frequency of CD41+ cells with high DNA content (>4 n) in ex vivo differentiated MKs (n = 2-3). CFU-MK, colony forming unit–megakaryocyte; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte-monocyte progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor; nd, not detectable. *P ≤ .05; **P < .01; ****P < .0001.

Acetylcholinesterase staining of cytospins from ex vivo MK cultures derived from primary bone marrow reveals that miR-22KO-derived MKs are smaller and less abundant than in wild type (Figure 4G), consistent with the differentiation defect we had observed in K562 cells. Furthermore, ex vivo differentiated miR-22KO MKs exhibit a lower frequency of high-ploidy cells than controls, suggesting impaired differentiation upon miR-22 loss (Figure 4H).

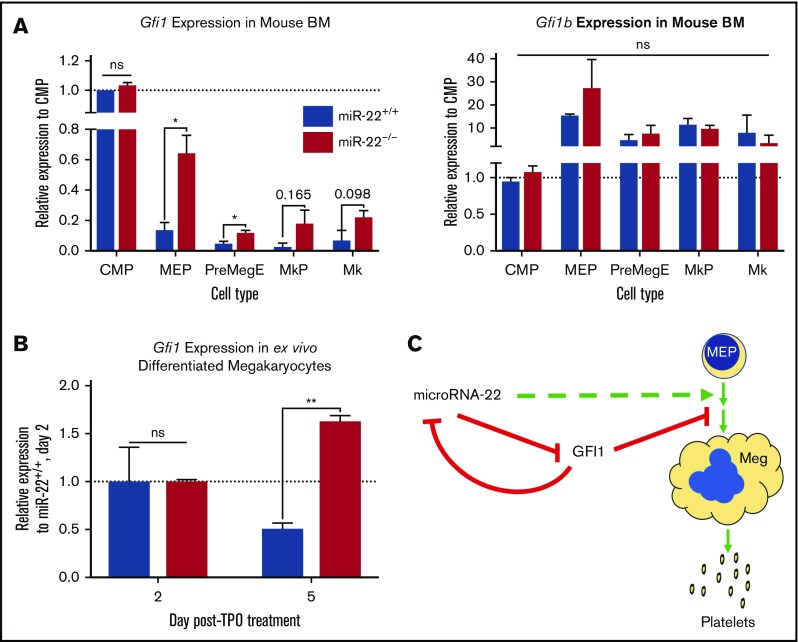

Loss of Gfi1 downregulation upon MK differentiation is observed in miR-22KO mice

Gfi1 is lowly expressed in MEPs66 and in K562 cells, and its expression diminishes further upon MK differentiation in mice (Figure 5A left). This is in contrast to Gfi1b, which is highly expressed in MK lineage25 (Figure 5A right) and in K562 cells and is a critical contributor to MK and erythrocyte differentiation.71-73 Interestingly, the 3′-UTR of GFI1 contains an miR-22 seed recognition sequence, whereas the 3′-UTR of GFI1B does not.

Figure 5.

Gfi1 expression persists in miR-22KOanimals throughout megakaryocytic differentiation. (A) Bone marrow from individual adult 129SV;miR-22 wildtype and miR-22 homozygous knockouts was stained according to surface markers listed in supplemental Table 3, DAPI for live/dead assessment, and sorted by FACS. Gene expression by qPCR for Gfi1 (left) and Gfi1b (right) in common myeloid progenitors through MK differentiation is shown. ActB was used as a housekeeping gene to quantify relative expression. Expression is shown relative to miR-22+/+ CMP, with the dotted line showing Relative Expression = 1 (n = 2-3). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. (B) Ex vivo MK differentiation of primary miR-22KO bone marrow cells. Bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated from individual adult 129SV:miR-22 wildtype and miR-22KO and were subjected to ex vivo MK differentiation by treatment with TPO. For gene expression analysis, MKs were enriched by 2-step bovine serum albumin gradient sedimentation. qPCR for Gfi1 in ex vivo differentiated MKs at 2 and 5 days after initiation of TPO treatment. ActB was used as a housekeeping gene to quantify relative expression. Expression is shown relative to day 2 miR-22+/+ MKs, with the dotted line showing Relative Expression = 1 (n = 2-3). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. (C) Proposed model whereby repression of GFI1 by miR-22 permits megakaryopoiesis. miR-22 promotes megakaryopoiesis (dotted green line) through direct repression of GFI1 (solid red line). GFI1 represses miR-22 expression by binding at the promoter of the MIR22HG. BM, bone marrow; MkP, megakaryocyte progenitor; PreMegE, megakaryocyte-erythrocyte precursor. *P ≤ .05; **P < .01.

To demonstrate that downregulation of Gfi1 is impaired upon miR-22 loss in vivo, consistent with the observation that GFI1 persists upon megakaryocytic differentiation of K562:miR-22KO cells, we performed qPCR on isolated cell types of increasing maturity in the MK lineage, from the CMP to the MK. Consistent with our data in K562 cells, Gfi1 expression is significantly elevated in miR-22KO MEP and PreMegE, and notably higher in the megakaryocyte progenitor and MK, as compared with controls (Figure 5A left), attributable to the loss of repression of Gfi1 expression by miR-22. Aberrant Gfi1 overexpression is restricted to the MK-erythroid lineages, because there is no increase in Gfi1 expression in the CMP, although there are similar levels of miR-22 in CMP and MEP (Figure 1A). In addition, we differentiated mature MKs ex vivo by culturing primary whole bone marrow in the presence of TPO. Similar to what was observed in vivo, loss of miR-22 derepresses Gfi1 expression in ex vivo differentiated MKs from miR-22KO (Figure 5B). Together, these data demonstrate that miR-22 represses Gfi1 during MK differentiation in vivo.

Discussion

Only a small number of miRNAs have been shown to positively regulate megakaryopoiesis.30-34 We used miR-22KO cell lines and animals to identify a role for miR-22 in MK differentiation, adding it to the short, but growing list of miRNAs that participate in this process. miR-22 expression is dramatically upregulated upon megakaryocytic differentiation of human K562 cells and during in vivo megakaryocytic differentiation in the adult mouse. Ectopic overexpression of miR-22 drives megakaryocytic differentiation in K562 cells and CRISPR-knockout of miR-22 impairs megakaryocytic differentiation, as measured by diminished expression of the platelet glycoprotein CD61 and the reduced capacity to yield high-ploidy cells. Similarly, in vivo and ex vivo MK differentiation is impaired in cells derived from miR-22KO animals. We have shown that GFI1 is a direct target of miR-22. GFI1 is aberrantly expressed in K562:miR-22KO cells upon differentiation, and Gfi1 expression persists throughout MK differentiation in miR-22KO animals. Furthermore, knockdown of GFI1 restores MK differentiation in K562:miR-22KO cells. Although our experimentation was limited to targets identified in undifferentiated K562:miR-22KO cells and we cannot rule out that further profiling of megakaryocytic differentiation could identify additional targets of miR-22, these data demonstrate that miR-22 is a critical positive regulator of MK differentiation through repression of its direct target GFI1 (Figure 5C).

Jiang et al observed downregulation of miR-22 in AML and explored its tumor-suppressive role through the targeting of known oncogenes.44 Although ours newly identified GFI1 as a downstream target of miR-22, they also described a relationship between these 2 factors. They identified conserved GFI1 recognition sites in the promoter region of MIR22HG and detailed how miR-22’s downregulation in AML is mediated through epigenetic silencing by TET1 recruited by GFI1, putting GFI1 as an upstream repressor of miR-22. We have also demonstrated that the promoter of the MIR22HG is derepressed upon disruption of a GFI1 core recognition motif. Together with the data presented by Jiang et al, this suggests that miR-22 participates in an autoregulatory loop whereby it drives its own expression through repression of its negative regulator, GFI1.

GFI1 is known to promote granulopoiesis and HSC maintenance. In our study, we have described a role for miR-22 in megakaryopoiesis through direct binding and repression of the GFI1 transcript. Interestingly, miR-22 is not predicted to bind to GFI1B. GFI1 and GFI1B exhibit mutually exclusive expression patterns. GFI1B is known to promote MK and erythroid differentiation,71,72,74-76 and mutations in GFI1B result in familial bleeding disorders.24,77 Consistent with their cell type specificity, a number of studies have demonstrated that GFI1 and GFI1B, which both exert their function by binding of the same AATC core recognition sequence, are capable of auto- and cross-regulation.78,79 We did not observe any changes to GFI1B expression that suggest that persistent GFI1 represses GFI1B transcription upon miR-22 loss, thus suppressing MK differentiation. Previous studies have observed direct competition between GATA-2/GFI1 and GATA-1/GFI1B for binding their shared motif.80 Perhaps aberrant persistent expression of GFI1 inhibits MK differentiation through competition with GFI1B. Overexpression of GFI1 has been shown to partially rescue megakaryocytic differentiation in GFI1B knockout animals76; however, this rescue was diminished compared with rescue with GFI1B or a fusion protein containing the GFI1B N-terminal region. Our observation that aberrant expression of GFI1 impairs megakaryocytic differentiation in the presence of endogenous GFI1B suggests they compete for DNA occupancy, and that GFI1-binding may negatively affect the GFI1B gene expression program because of failure to recruit the appropriate cofactors to the GFI1B N-terminal domain. Unfortunately, chromatin immunoprecipitation of GFI1/GFI1B in the hematopoietic system that might begin to address this question is not publicly available.

miR-22KO animals have fewer mature MKs with lower DNA content, and ex vivo derived miR-22KO MKs were smaller and with lower DNA content, suggesting a maturation defect upon miR-22 loss. There is mounting evidence that MKs contribute to the HSC niche, particularly for MK- and myeloid-biased HSCs.4,17 Although we did not explore any disruption to the HSC niche secondary to dysfunction of miR-22KO MKs, we did observe a slight increase in CD150+CD48−CD135−KSL cells in miR-22KO animals (supplemental Figure 5G), which may reflect disruption of the niche. Depletion of MKs results in HSC expansion due to loss of MK-derived cytokines.8,9 Likewise, the production of TPO, essential for HSC maintenance, increases with MK ploidy,81 suggesting that a disruption in MK size and maturation could disrupt the HSC niche.

Other recent studies have implicated miR-22 in terminal differentiation in the MK-erythrocyte lineage. Kadmon et al reported that miR-22 is an important positive regulator of the interferon response to viral infection, as evidenced by a blunted response in the context of miR-22KO in the C57BL/6 albino background, and as a brake to erythrocyte maturation, as evidenced by accumulation of late-stage erythrocytes.45 Although they did not observe an increase in MEP, as we did, nor did they observe any changes to circulating platelet levels, they reported an increase in CD41+CD34−Lineage− MK precursors in miR-22KO mice and suggest that this reflects an enhancement of MK differentiation. Although we did not assay that particular population, our results suggest that an increase in progenitors without a change in circulating platelet numbers does not suggest enhanced megakaryopoiesis. Rather, ex vivo differentiation of accumulated progenitors revealed a differentiation and maturation defect in our study.

It is emerging that miR-22 expression is a common and important regulator of terminal differentiation across the myeloid lineage. Our study has shown that miR-22 increases with and participates in megakaryopoiesis. In addition, Kadmon et al45 have shown that miR-22 acts as a break to erythrocyte maturation, consistent with previous studies of miR-22 overexpression.42 Other studies have demonstrated a role for miR-22 in promoting granulopoiesis.43,44 It is fascinating that in these very different cellular contexts, when cells are expressing specific repertoires of genes to exert highly specialized functions, that upregulation of miR-22 may participate in terminal differentiation across cell types. Cellular context and the transcriptome, particularly dilution of miRNA recognition elements, are critical in determining miRNA function,82-84 and surely miR-22 exerts its effects by targeting different transcripts in these diverse cell types. However, it is striking that the upregulation of miR-22 is a conserved feature across these different processes. The context-specific activity of miR-22 on a diverse array of potential targets must be considered in future studies of miR-22, the regulation of the miR-22 locus, and, particularly, in the development of miR-22-based therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Ito Laboratory, as well as members of Department of Cell Biology, especially Arthur Skoultchi, Charles Query, Paul Frenette, Britta Will, Michael Willcockson, Sean Healton, Varun Gupta, Brian Kosmyna, Susana Rodriguez-Santiago, Ali Zahalka, and Sandra Pinho for their stimulating scientific discussion and help with materials and reagents. They thank Jonathan Weissman (University of California, San Francisco) for providing the CRISPRi tools and library. In addition, the authors thank Teresa Bowman and Britta Will for their critical reading of the manuscript and the members of the Einstein Flow Cytometry core facility (National Institutes of Health [NIH], National Cancer Institute grant P30CA013330).

This work is supported by NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants F30DK108532 (C.N.W.), R01DK098263, R01DK100689, and R01DK115577 (K.I.), and the Leukemia Lymphoma Society and New York State Department of Health (NYSTEM Program). In addition, this work is supported by an NIH, National Institute of General Medical Sciences MSTP training grant T32GM007288 (C.N.W.; Myles Akabas, Program Director). K.I. is a Research Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Authorship

Contribution: C.N.W. and K.I. conceived the hypotheses and designed the experiments; C.N.W. performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; and K.I. edited and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Keisuke Ito, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1301 Morris Park Ave, Price 102, Bronx, NY 10461; e-mail: keisuke.ito@einstein.yu.edu.

References

- 1.Bluteau D, Lordier L, Di Stefano A, et al. Regulation of megakaryocyte maturation and platelet formation. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl 1):227-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaushansky K. Historical review: megakaryopoiesis and thrombopoiesis. Blood. 2008;111(3):981-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geddis AE. Megakaryopoiesis. Semin Hematol. 2010;47(3):212-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinho S, Marchand T, Yang E, Wei Q, Nerlov C, Frenette PS. Lineage-biased hematopoietic stem cells are regulated by distinct niches. Dev Cell. 2018;44(5):634-641.e634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulais PE, Frenette PS. Making sense of hematopoietic stem cell niches. Blood. 2015;125(17):2621-2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heazlewood SY, Neaves RJ, Williams B, Haylock DN, Adams TE, Nilsson SK. Megakaryocytes co-localise with hemopoietic stem cells and release cytokines that up-regulate stem cell proliferation. Stem Cell Res (Amst). 2013;11(2):782-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson TS, Caselli A, Otsuru S, et al. Megakaryocytes promote murine osteoblastic HSC niche expansion and stem cell engraftment after radioablative conditioning. Blood. 2013;121(26):5238-5249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruns I, Lucas D, Pinho S, et al. Megakaryocytes regulate hematopoietic stem cell quiescence through CXCL4 secretion. Nat Med. 2014;20(11):1315-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao M, Perry JM, Marshall H, et al. Megakaryocytes maintain homeostatic quiescence and promote post-injury regeneration of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2014;20(11):1321-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404(6774):193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debili N, Coulombel L, Croisille L, et al. Characterization of a bipotent erythro-megakaryocytic progenitor in human bone marrow. Blood. 1996;88(4):1284-1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakorn TN, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. Characterization of mouse clonogenic megakaryocyte progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(1):205-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pronk CJ, Rossi DJ, Månsson R, et al. Elucidation of the phenotypic, functional, and molecular topography of a myeloerythroid progenitor cell hierarchy. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(4):428-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forsberg EC, Serwold T, Kogan S, Weissman IL, Passegué E. New evidence supporting megakaryocyte-erythrocyte potential of flk2/flt3+ multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Cell. 2006;126(2):415-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer SW, Schroeder AV, Smith-Berdan S, Forsberg EC. All hematopoietic cells develop from hematopoietic stem cells through Flk2/Flt3-positive progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(1):64-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyer SW, Beaudin AE, Forsberg EC. Mapping differentiation pathways from hematopoietic stem cells using Flk2/Flt3 lineage tracing. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(17):3180-3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanjuan-Pla A, Macaulay IC, Jensen CT, et al. Platelet-biased stem cells reside at the apex of the haematopoietic stem-cell hierarchy. Nature. 2013;502(7470):232-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto R, Morita Y, Ooehara J, et al. Clonal analysis unveils self-renewing lineage-restricted progenitors generated directly from hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 2013;154(5):1112-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woolthuis CM, Park CY. Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell commitment to the megakaryocyte lineage. Blood. 2016;127(10):1242-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grinenko T, Arndt K, Portz M, et al. Clonal expansion capacity defines two consecutive developmental stages of long-term hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2014;211(2):209-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez-Fraticelli AE, Wolock SL, Weinreb CS, et al. Clonal analysis of lineage fate in native haematopoiesis. Nature. 2018;553(7687):212-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto R, Wilkinson AC, Ooehara J, et al. Large-scale clonal analysis resolves aging of the mouse hematopoietic stem cell compartment. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22(4):600-607.e604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tijssen MR, Ghevaert C. Transcription factors in late megakaryopoiesis and related platelet disorders. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(4):593-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevenson WS, Morel-Kopp MC, Chen Q, et al. GFI1B mutation causes a bleeding disorder with abnormal platelet function. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(11):2039-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vassen L, Okayama T, Möröy T. Gfi1b:green fluorescent protein knock-in mice reveal a dynamic expression pattern of Gfi1b during hematopoiesis that is largely complementary to Gfi1. Blood. 2007;109(6):2356-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bissels U, Bosio A, Wagner W. MicroRNAs are shaping the hematopoietic landscape. Haematologica. 2012;97(2):160-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss CN, Ito K. A macro view of microRNAs: the discovery of microRNAs and their role in hematopoiesis and hematologic disease. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2017;334:99-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eichhorn SW, Guo H, McGeary SE, et al. mRNA destabilization is the dominant effect of mammalian microRNAs by the time substantial repression ensues. Mol Cell. 2014;56(1):104-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartel DP. Metazoan microRNAs. Cell. 2018;173(1):20-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Opalinska JB, Bersenev A, Zhang Z, et al. MicroRNA expression in maturing murine megakaryocytes. Blood. 2010;116(23):e128-e138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garzon R, Pichiorri F, Palumbo T, et al. MicroRNA fingerprints during human megakaryocytopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(13):5078-5083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hussein K, Theophile K, Dralle W, Wiese B, Kreipe H, Bock O. MicroRNA expression profiling of megakaryocytes in primary myelofibrosis and essential thrombocythemia. Platelets. 2009;20(6):391-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ichimura A, Ruike Y, Terasawa K, Shimizu K, Tsujimoto G. MicroRNA-34a inhibits cell proliferation by repressing mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 during megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77(6):1016-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu J, Guo S, Ebert BL, et al. MicroRNA-mediated control of cell fate in megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors. Dev Cell. 2008;14(6):843-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emmrich S, Henke K, Hegermann J, Ochs M, Reinhardt D, Klusmann JH. miRNAs can increase the efficiency of ex vivo platelet generation. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(11):1673-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klusmann JH, Li Z, Böhmer K, et al. miR-125b-2 is a potential oncomiR on human chromosome 21 in megakaryoblastic leukemia. Genes Dev. 2010;24(5):478-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tetteroo PA, Massaro F, Mulder A, Schreuder-van Gelder R, von dem Borne AE. Megakaryoblastic differentiation of proerythroblastic K562 cell-line cells. Leuk Res. 1984;8(2):197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutherland JA, Turner AR, Mannoni P, McGann LE, Turc JM. Differentiation of K562 leukemia cells along erythroid, macrophage, and megakaryocyte lineages. J Biol Response Mod. 1986;5(3):250-262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmad HM, Muiwo P, Muthuswami R, Bhattacharya A. FosB regulates expression of miR-22 during PMA induced differentiation of K562 cells to megakaryocytes. Biochimie. 2017;133:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmad HM, Muiwo P, Ramachandran SS, et al. miR-22 regulates expression of oncogenic neuro-epithelial transforming gene 1, NET1. FEBS J. 2014;281(17):3904-3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):996-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song SJ, Ito K, Ala U, et al. The oncogenic microRNA miR-22 targets the TET2 tumor suppressor to promote hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and transformation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(1):87-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen C, Chen MT, Zhang XH, et al. The PU.1-modulated microRNA-22 is a regulator of monocyte/macrophage differentiation and acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(9):e1006259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang X, Hu C, Arnovitz S, et al. miR-22 has a potent anti-tumour role with therapeutic potential in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):11452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kadmon CS, Landers CT, Li HS, Watowich SS, Rodriguez A, King KY. MicroRNA-22 controls interferon alpha production and erythroid maturation in response to infectious stress in mice. Exp Hematol. 2017;56:7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bauer DE, Canver MC, Orkin SH. Generation of genomic deletions in mammalian cell lines via CRISPR/Cas9. J Vis Exp. 2015;(95):e52118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Adamson B, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-mediated control of gene repression and activation. Cell. 2014;159(3):647-661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heckl D, Kowalczyk MS, Yudovich D, et al. Generation of mouse models of myeloid malignancy with combinatorial genetic lesions using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(9):941-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. ; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. eLife. 2015;4:e05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ru Y, Kechris KJ, Tabakoff B, et al. The multiMiR R package and database: integration of microRNA-target interactions along with their disease and drug associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(17):e133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang R, Zhao L, Chen H, et al. Megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells induced by PMA reduced the activity of respiratory chain complex IV. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin Y, Chen Z, Liu X, Zhou X. Evaluating the microRNA targeting sites by luciferase reporter gene assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;936:117-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gurha P, Abreu-Goodger C, Wang T, et al. Targeted deletion of microRNA-22 promotes stress-induced cardiac dilation and contractile dysfunction. Circulation. 2012;125(22):2751-2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shivdasani RA, Schulze H. Culture, expansion, and differentiation of murine megakaryocytes. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2005;Chapter 22:Unit 22F.6. 10.1002/0471142735.im22f06s67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D68-D73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Meer LT, Jansen JH, van der Reijden BA. Gfi1 and Gfi1b: key regulators of hematopoiesis. Leukemia. 2010;24(11):1834-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vitali C, Bassani C, Chiodoni C, et al. SOCS2 Controls Proliferation and Stemness of Hematopoietic Cells under Stress Conditions and Its Deregulation Marks Unfavorable Acute Leukemias. Cancer Res. 2015;75(11):2387-2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dabrowska MJ, Dybkaer K, Johnsen HE, Wang B, Wabl M, Pedersen FS. Loss of MicroRNA targets in the 3′ untranslated region as a mechanism of retroviral insertional activation of growth factor independence 1. J Virol. 2009;83(16):8051-8061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grimes HL, Gilks CB, Chan TO, Porter S, Tsichlis PN. The Gfi-1 protooncoprotein represses Bax expression and inhibits T-cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(25):14569-14573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saleque S, Kim J, Rooke HM, Orkin SH. Epigenetic regulation of hematopoietic differentiation by Gfi-1 and Gfi-1b is mediated by the cofactors CoREST and LSD1. Mol Cell. 2007;27(4):562-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grimes HL, Chan TO, Zweidler-McKay PA, Tong B, Tsichlis PN. The Gfi-1 proto-oncoprotein contains a novel transcriptional repressor domain, SNAG, and inhibits G1 arrest induced by interleukin-2 withdrawal. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(11):6263-6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeng H, Yücel R, Kosan C, Klein-Hitpass L, Möröy T. Transcription factor Gfi1 regulates self-renewal and engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells. EMBO J. 2004;23(20):4116-4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hock H, Hamblen MJ, Rooke HM, et al. Gfi-1 restricts proliferation and preserves functional integrity of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2004;431(7011):1002-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Person RE, Li FQ, Duan Z, et al. Mutations in proto-oncogene GFI1 cause human neutropenia and target ELA2. Nat Genet. 2003;34(3):308-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karsunky H, Zeng H, Schmidt T, et al. Inflammatory reactions and severe neutropenia in mice lacking the transcriptional repressor Gfi1. Nat Genet. 2002;30(3):295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bessman JD. The relation of megakaryocyte ploidy to platelet volume. Am J Hematol. 1984;16(2):161-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang Z, Dore LC, Li Z, et al. GATA-2 reinforces megakaryocyte development in the absence of GATA-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(18):5168-5180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Randrianarison-Huetz V, Laurent B, Bardet V, Blobe GC, Huetz F, Duménil D. Gfi-1B controls human erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation by regulating TGF-beta signaling at the bipotent erythro-megakaryocytic progenitor stage. Blood. 2010;115(14):2784-2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Osawa M, Yamaguchi T, Nakamura Y, et al. Erythroid expansion mediated by the Gfi-1B zinc finger protein: role in normal hematopoiesis. Blood. 2002;100(8):2769-2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garçon L, Lacout C, Svinartchouk F, et al. Gfi-1B plays a critical role in terminal differentiation of normal and transformed erythroid progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;105(4):1448-1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saleque S, Cameron S, Orkin SH. The zinc-finger proto-oncogene Gfi-1b is essential for development of the erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages. Genes Dev. 2002;16(3):301-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Elmaagacli AH, Koldehoff M, Zakrzewski JL, Steckel NK, Ottinger H, Beelen DW. Growth factor-independent 1B gene (GFI1B) is overexpressed in erythropoietic and megakaryocytic malignancies and increases their proliferation rate. Br J Haematol. 2007;136(2):212-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Foudi A, Kramer DJ, Qin J, et al. Distinct, strict requirements for Gfi-1b in adult bone marrow red cell and platelet generation. J Exp Med. 2014;211(5):909-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Monteferrario D, Bolar NA, Marneth AE, et al. A dominant-negative GFI1B mutation in the gray platelet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(3):245-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Doan LL, Porter SD, Duan Z, et al. Targeted transcriptional repression of Gfi1 by GFI1 and GFI1B in lymphoid cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(8):2508-2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vassen L, Fiolka K, Mahlmann S, Möröy T. Direct transcriptional repression of the genes encoding the zinc-finger proteins Gfi1b and Gfi1 by Gfi1b. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(3):987-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Laurent B, Randrianarison-Huetz V, Kadri Z, Roméo PH, Porteu F, Duménil D. Gfi-1B promoter remains associated with active chromatin marks throughout erythroid differentiation of human primary progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27(9):2153-2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nakamura-Ishizu A, Takubo K, Fujioka M, Suda T. Megakaryocytes are essential for HSC quiescence through the production of thrombopoietin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;454(2):353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arvey A, Larsson E, Sander C, Leslie CS, Marks DS. Target mRNA abundance dilutes microRNA and siRNA activity. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Poliseno L, Salmena L, Zhang J, Carver B, Haveman WJ, Pandolfi PP. A coding-independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature. 2010;465(7301):1033-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tay Y, Kats L, Salmena L, et al. Coding-independent regulation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by competing endogenous mRNAs. Cell. 2011;147(2):344-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.