Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cardiac sympathetic denervation (CSD) has been shown to reduce the burden of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shocks in a small series of patients with structural heart disease (SHD) and recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias (VT).

OBJECTIVE

We assessed the value of CSD and the characteristics associated with outcomes in this population.

METHODS

Patients with SHD who underwent CSD for refractory VT or VT storm in 5 international centers were analyzed by the International Cardiac Sympathetic Denervation Collaborative Group. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate freedom from ICD shock, transplantation, and death. Cox proportional hazards models were used to analyze variables associated with ICD shock recurrence and mortality after CSD.

RESULTS

Between 2009 and 2016, 121 patients (age 55 ± 13 years, 26% female, and an ejection fraction of 30 ± 13%) underwent left or bilateral CSD. One-year freedom from sustained VT/ICD shock and ICD shock-free survival were 58.2% and 50.4%, respectively. CSD reduced burden of ICD shocks from a mean of 18 ± 30 (median 10) in the year prior to study entry to 2.0 ± 4.3 (median 0) at a median follow-up of 1.1 years (p < 0.01). On multivariable analysis, pre-procedure New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III and IV heart failure and longer VT cycle lengths were associated with recurrent ICD shocks, while advanced NYHA class, longer VT cycle lengths, and a left-sided only procedure predicted the combined endpoint of sustained VT/ICD shock recurrence, death, and transplantation. Of the 120 patients on antiarrhythmic medication prior to CSD, 39 (32%) no longer required them at follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

CSD decreased sustained VT and ICD shock recurrence in patients with refractory VT. Characteristics independently associated with recurrence and mortality were advanced heart failure, VT cycle length, and a left-sided only procedure.

Keywords: antiarrhythmic drugs, autonomic nervous system, functional class, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, orthoptopic heart transplantation

The autonomic nervous system plays an important role in the genesis and maintenance of ventricular arrhythmias (1,2). Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) shocks for recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias (VT) are known to increase morbidity and mortality and decrease quality of life (3,4). Neuromodulation is emerging as a therapeutic option for patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias and ICD shocks (5,6). Cardiac sympathetic denervation (CSD) has been shown to reduce VT inducibility and ischemia-driven ventricular arrhythmias in animal models of myocardial infarction (7,8) and decrease the burden of VT and ICD shocks in small series of patients with cardiomyopathy and recurrent VT or VT storm (9–12). However, long-term outcomes in larger patient populations and predictors of VT recurrence and ICD shocks after CSD are unknown. This information is important for clinical decision making to identify patients who may derive the greatest benefit from the treatment. This study sought to evaluate the outcomes of recurrent ICD shock, death, and orthoptopic heart transplantation (OHT) after cardiac sympathetic denervation and to evaluate patient characteristics associated with recurrent ICD shock after the procedure using an international multicenter CSD database.

METHODS

The International Cardiac Sympathetic Denervation Collaboration (ICSDC) consists of 5 international sites with experience in performing CSD that have developed a shared database. Retrospective analysis of consecutive patients with structural heart disease (SHD) who underwent CSD for recurrent VT or VT storm was performed between 2009 and 2016. SHD was defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction <55%, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) was defined by history of myocardial infarction or myocardial perfusion defect with correlating obstructive disease on coronary angiography. VT storm was defined as at least 3 episodes of VT within 24 h. Study approval was obtained from the institutional review board of each participating center. Baseline characteristics used to predict post-procedural outcomes were obtained from medical records.

CSD PROCEDURE

All patients underwent left or bilateral CSD using a video-assisted thorascopic surgery approach as previously described (9,11,13). Investigator preference determine whether left or bilateral CSD was performed; however, left CSD was always performed first, in case right CSD would not be tolerated due to hemodynamic instability. All procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Single lung inflation was used in most patients, except for 18 patients who underwent the procedure with standard dual lung inflation. Three 1.5 cm incisions were made in the ipsilateral sub-axillary area. After the ipsilateral lung was deflated, the sympathetic chain behind the parietal pleura was identified and the lower one-half to one-third of the stellate ganglion, as well as the thoracic ganglia at T2 to T4, were transected and removed. Confirmation of neuronal cell bodies within the ganglia was obtained via histological analysis. Additionally, when present, the nerve of Kuntz was divided (14,15). Chest tubes were placed at the end of the procedure and removed within 24 h of confirmation of lung re-expansion and lack of pleural effusion.

Subsequently, patients were followed up clinically and by ICD interrogations at regular intervals. For patients not followed at an ICSDC center, the referring electrophysiologist or cardiologist was contacted and available ICD interrogations, clinic notes, and hospitalization records were obtained and reviewed. Telephone interviews were performed routinely with patients and family members. Every patient was contacted for follow-up. When a patient’s most recent ICD interrogation was not available, the date of the last ICD interrogation or clinical follow-up was used and patient data censored at that time. Recurrent VT was defined as documented sustained VT requiring hospitalization and/or clinic visit or ICD shock. Date of sustained VT or ICD shock, OHT, or death was noted in addition to the last follow-up date. Antiarrhythmic therapy after ablation was at the discretion of the treating investigator. Transplant-free survival was evaluated in patients with and without recurrent ICD shocks or sustained VT.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables were assessed as means with standard deviations (SDs) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) and categorical variables as percentages. A 2-sample Student t test was used to determine differences between groups. Comparison of ICD shock burden pre- and post-procedure was made using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to estimate freedom from recurrent ICD shock, OHT, and death. Log-rank test was used to compare Kaplan-Meier curves. For subgroup analysis, cumulative shock-free survival and cardiovascular mortality was calculated using Kaplan-Meier curves and tested by the log-rank test for trend. For Kaplan-Meier analysis of freedom from ICD shock, patients lost to long-term follow-up were censored at the time of last follow-up.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards frailty model was used to analyze variables independently associated with ICD shock or the combined endpoint of ICD shock, OHT, and death. Clinically relevant variables and variables with p values < 0.15 were included in the multivariable model as covariates. For VT or ICD shock recurrence, covariates included were age, sex, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, presence of polymorphic VT, number of VT morphologies, number of previous VT ablations, chronic kidney disease (CKD), multiple antiarrhythmic therapy, slowest VT cycle length, and a left-only procedure. For the combined endpoint of recurrent VT or ICD shock, death, and OHT, diabetes was also included in the model given its significance on univariable (unadjusted) analysis.

Except for creatinine and VT cycle length (which were available for 89 patients), complete variables were available for all patients. For incomplete variables, complete case analysis was used. To assess for bias with regards to these missing variables, incomplete variables were also handled and hazard ratios (HR) confirmed using a multiple imputation approach with 10 imputations; the imputations were based on an iterative Markov chain Monte Carlo method and initial values were generated by an expectation–maximization algorithm. P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Between April 2009 and April 2016, 121 patients (55 ± 13 years old, 26% female) with SHD underwent bilateral or left CSD for refractory VT or VT storm at 5 centers. Median follow-up was 1.1 years (IQR: 0.4 to 2.4) and the mean follow-up was 1.5 ± 1.4 years. The mean ejection fraction was 30 ± 13% with 11% in NYHA class I, 41% class II, 40% class III, and 8% class IV heart failure (HF). ICM was present in 33 patients (27%), nonischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM) in 86 patients (71%), and 2 patients had mixed cardiomyopathy (cardiomyopathy out of proportion to the degree of coronary artery disease noted on angiography). The etiology of NICM was idiopathic (n = 43), Chagasic cardiomyopathy (n = 12), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (n = 6), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (n = 7), myocarditis (n = 8), valvular heart disease (n = 6), drug abuse (n = 2), familial dilated cardiomyopathy (n = 1), and polymyositis/necrotizing myopathy (n = 1).

Of the 121 patients, 120 were on antiarrhythmic drug therapy, primarily amiodarone (99%), 50% were on multiple antiarrhythmic medications, and 92% were on beta-blocker therapy. A history of VT storm prior to the procedure was present in 91 patients (75%), and 64% had more than 1 VT morphology noted prior to CSD. VT ablation had been performed in 66% of patients (median number of VT ablations: 2; IQR: 1 to 2). CSD was offered to 34% of patients instead of VT ablation after failure of antiarrhythmic therapies because either the patients also suffered from polymorphic VT, thought to be unresponsive to VT ablation, or because of the high cost of VT ablation. CKD was present in 27% and diabetes mellitus in 19%. Twenty-three patients (19%) had removal of the left cervicothoracic chain only. Patient characteristics by ICD shock or sustained VT recurrence and cardiac transplantation and death are shown in Table 1. Five patients refused ICD placement, and in these patients, we noted episodes of sustained VT pre- and post-procedure requiring cardioversion or causing syncope or presyncope leading to hospitalization or clinic visits.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| ICD Shock Recurrence | Death/OHT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Yes (n = 57) |

No (n = 70) |

p Value * | Yes (n = 39) |

No (n = 82) |

p Value* | |

| Age, yrs | 57.2 ±12.8 | 53.8 ±13.5 | 0.22 | 61.0 ±11.7 | 52.4 ±13.1 | <0.001 |

| Female | 10 (19.6) | 21 (30) | 0.28 | 8 (20.5) | 23 (28.0) | 0.50 |

| Cardiomyopathy | ||||||

| ICM | 13 (25.5) | 20 (28.6) | 0.90 | 10 (25.6) | 23 (28.0) | 0.92 |

| NICM | 37 (72.5) | 49 (70.0) | 28 (71.8) | 58 (70.7) | ||

| Ejection fraction, % | 29.8 ± 12.6 | 29.6 ± 12.5 | 0.77 | 26.2 ± 12.3 | 31.3 ± 12.3 | 0.02 |

| NYHA class | 0.002 | |||||

| I | 2 (4.2) | 29.6 (12.5) | 4 (11.1) | 9 (11.1) | ||

| II | 22 (45.8) | 26 (37.7) | 0.08 | 11 (30.6) | 37 (45.7) | |

| III | 18 (37.5) | 29 (42.0) | 13 (36.1) | 34 (42.0) | ||

| IV | 6 (12.5) | 3 (4.3) | 8 (22.2) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Electrical storm | 36 (70.6) | 55 (78.6) | 0.43 | 26(66.7) | 65 (79.3) | 0.2 |

| >1 VT morphology | 36 (70.6) | 41 (58.6) | 0.24 | 29 (74.4) | 48 (58.5) | 0.14 |

| Polymorphic VT | 13 (27.7) | 22 (48.9) | 0.06 | 14 (40.0) | 68 (82.9) | 0.93 |

| VT cycle length, ms | 400 (309-480) | 290(273-356) | 0.001 | 400(300-483) | 333(280-400) | 0.046 |

| VT ablations, n | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.002 | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 0.06 |

| Prior cardiac surgery | 14 (27.5) | 17 (24.3) | 0.86 | 13 (33.3) | 18 (22.0) | 0.33 |

| Hypertension | 29 (56.9) | 39 (55.7) | 1.0 | 23 (59.0) | 45 (54.9) | 0.82 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 22 (43.1) | 31 (44.3) | 1.0 | 21 (53.8) | 32 (39.0) | 0.20 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 14 (27.5) | 16 (22.9) | 0.72 | 14 (35.9) | 16 (19.5) | 0.08 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (23.5) | 11 (15.7) | 0.4 | 14 (35.9) | 9 (11.0) | 0.003 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 16 (34.0) | 8 (19.0) | 0.18 | 18 (51.4) | 6 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| >1 antiarrhythmic drug | 31 (60.8) | 29 (41.4) | 0.055 | 25 (64.1) | 35 (42.7) | 0.045 |

| Left-sided procedure only | 12 (23.5) | 11 (15.7) | 0.3 | 14 (35.9) | 9 (11.0) | 0.003 |

Values are mean ± SD, n (%), or median (interquartile range).

Highlighted p values represent those where baseline comparisons yielded a value < 0.1.

ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; ICM = ischemic cardiomyopathy; NICM = non-ischemic cardiomyopathy; NYHA = New York Heart Association; OHT = orthotopic heart transplantation; VT = ventricular tachyarrhythmia.

Hemothorax occurred in 3 patients (2.4%), pneumothorax in 6 (5%), and ptosis or Horner’s syndrome in 5 (4%) acutely. Symptoms of Horner’s syndrome, including ptosis, were mild in all 5 patients and resolved completely in 4 of these patients by 6-month follow-up. Sixteen patients (13%) experienced hypotension requiring at least 24 h of vasopressor support after anesthesia. All patients were successfully weaned off vasopressor medications. Incisional cellulitis occurred in 2 patients (1.6%), and multifocal pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and nausea and vomiting after surgery that resolved within 24 h in 1 patient each.

EFFICACY OF CSD IN PREVENTING ICD SHOCKS

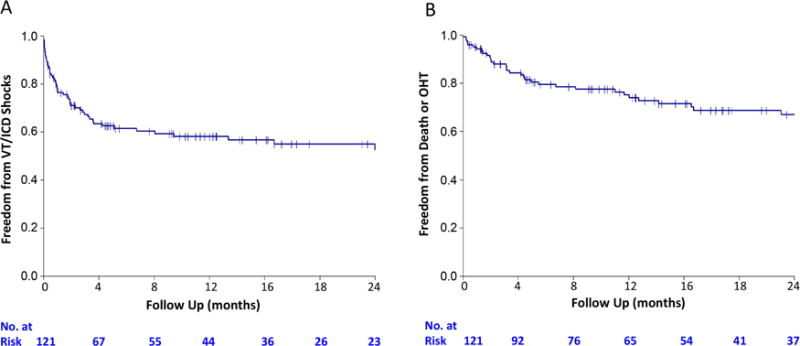

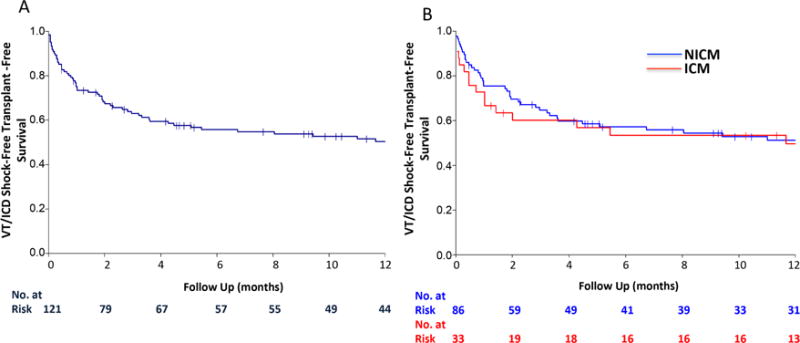

At 1 year, 58% of patients were free of ICD shocks or sustained VT (Figure 1). At the end of follow-up (mean 1.5 ± 1.4 years), the number had decreased to 49%. Twenty patients underwent a VT ablation procedure after CSD. Nineteen had experienced recurrent ICD shock(s) after CSD prior to ablation. One patient underwent ablation for symptomatic premature ventricular contractions after CSD but had not experienced recurrent ICD shocks or antitachycardia pacing (ATP) therapy. At the end of follow-up, 31 of 121 patients had died and 10 had undergone OHT. Freedom from transplantation or death at 1 year was 76.2% (Figure 1). Freedom from ICD shocks, sustained VT, death, and OHT was 50% at 1 year (Figure 2) and 39% at the end of follow-up. The median time to ICD shock was 1.2 years (IQR: 0.4 to 2.8). The number of ICD shocks or sustained VT episodes in the year prior to cardiac sympathetic denervation was mean 18 ± 30 and median of 10 (IQR: 4.5 to 18). At the end of follow-up, CSD significantly reduced the number of ICD shocks or sustained VT episodes (mean 2.0 ± 4.3; median: 0 [IQR: 0 to 2]; p < 0.01). Therefore, CSD reduced the number of ICD shocks by 88%.

FIGURE 1. Freedom from Individual Endpoints.

Freedom from (A) sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias (VT) or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shock as well as (B) freedom from death or orthoptopic heart transplantation (OHT) slowed after 1 year.

FIGURE 2. Sustained Survival.

Similar sustained VT/ICD shock-free, transplant-free survival is seen in (A) the overall population and (B) in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) compared to patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM). Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Occurrence of ATP has not been specifically associated with mortality and we could not often verify if ATP delivery (which was often asymptomatic) was appropriate or inappropriate based on available ICD logs and time from event to ICD interrogation. Nevertheless, available ATP data were analyzed and the freedom from sustained VT, ICD shocks, or ATP after CSD at 1 year was 54% (Online Figure 1). As noted earlier, pre-procedure, 99% of patients were on antiarrhythmic medications. At the end of follow-up, 39 (32%) had been taken off all antiarrhythmic medications and were only on beta-blocker therapy for their cardiomyopathy when indicated or tolerated.

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS ASSOCIATED WITH OUTCOMES

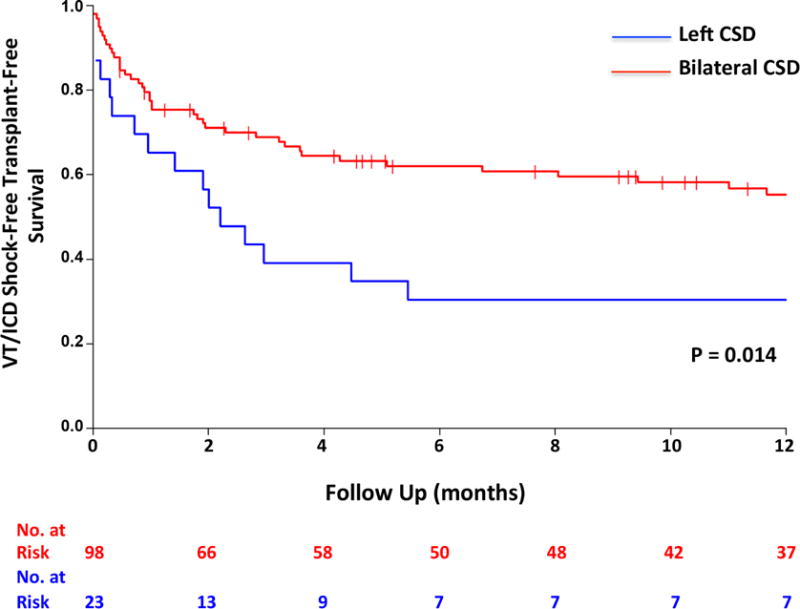

As noted by the Kaplan-Meier curves, ICD shock recurrence in the first year after CSD had a steep slope that seemed to stabilize after the first 6 months. Therefore, patient characteristics associated with sustained VT and ICD shock as well as the combined endpoint of sustained VT or ICD shock, death, and OHT were assessed after CSD to define whether certain populations were less likely to benefit from CSD. On Kaplan-Meier analysis, there was no difference in outcomes of patients with ICM or NICM with regards to sustained VT or ICD shock recurrence or the combined endpoint (Figure 2). However, patients with bilateral CSD had longer ICD-shock-free, transplant-free survival compared to patients who underwent a left-only procedure (p = 0.014) (Figure 3), although there was no difference in the outcome of sustained VT or ICD shock.

FIGURE 3. Bilateral Versus Left CSD.

There was a significant difference in the combined endpoint between bilateral and left cardiac sympathetic denervation (CSD). Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

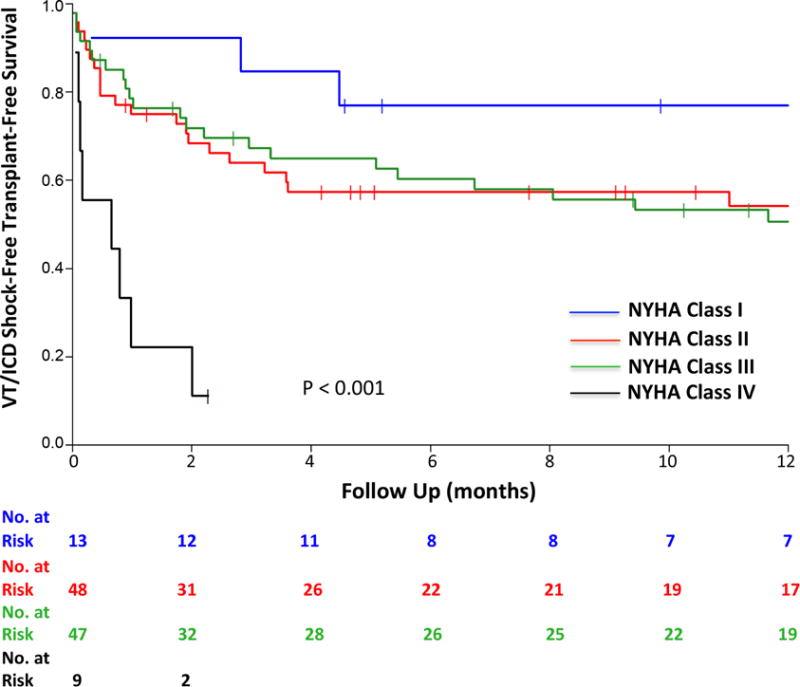

A VT cycle length >400 ms proved borderline statistically significant (p = 0.07) on unadjusted events analysis for arrhythmia recurrence. Unadjusted event analysis showed that patients with recurrent sustained VT or ICD shocks after CSD, as well as those with the combined endpoint were more likely to have advanced NYHA class (Figure 4). As noted on Kaplan-Meier analysis a longer VT cycle length, CKD, and having been treated with more than 1 antiarrhythmic therapy (Table 1), were also associated with statistically significant HRs (Online Table 1).

FIGURE 4. Effect of NYHA Class on Outcomes.

Worsening New York Heart Association (NYHA) class significantly diminished CSD effectiveness on outcomes. Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 3.

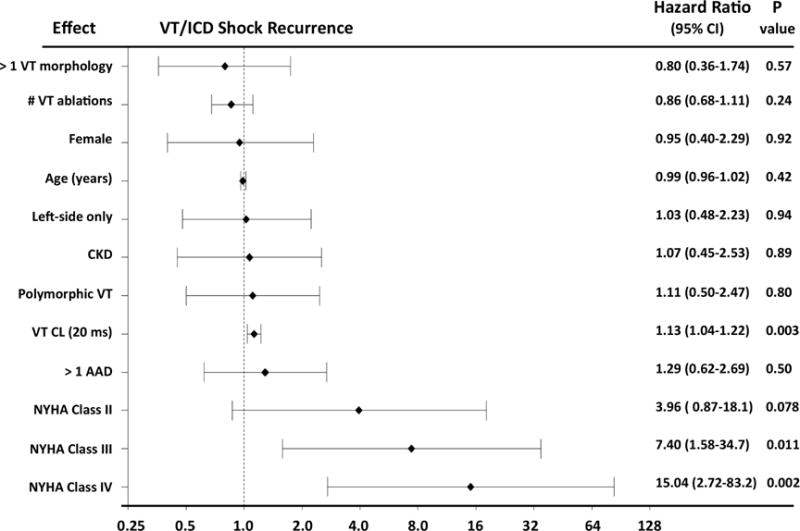

Cox multiple regression analysis showed that the risk factors associated with recurrent sustained VT or ICD shock were advanced NYHA class and a longer VT cycle length (Figure 5) using complete case analysis. A multivariable model generated from multiple imputation analysis for VT cycle length, confirmed effects of longer VT cycle length on VT or ICD shock recurrence (HR: 1.16; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.06 to 1.28; p < 0.002).

Figure 5. Pre-procedural Characteristics Associated with VT/ICD Shock Recurrence after CSD.

Advanced NYHA class and longer VT cycle length (CL) predicted recurrence of sustained VT and ICD shock. AAD = antiarrhythmic drug; CI = confidence interval; CKD = chronic kidney disease; other abbreviations as in Figures 1, 3, and 4.

In patients who reached the endpoint of OHT and death, older age, greater number of VT morphologies, longer VT cycle length, greater number of VT ablation procedures, presence of diabetes mellitus, CKD, >1 antiarrhythmic medication, and a left-sided only procedure had statistically significant HRs on unadjusted analysis (Online Table 2). On Cox multiple regression analysis, advanced NYHA class and a left-sided only procedure were independent variables associated with death or OHT after CSD (Online Table 2).

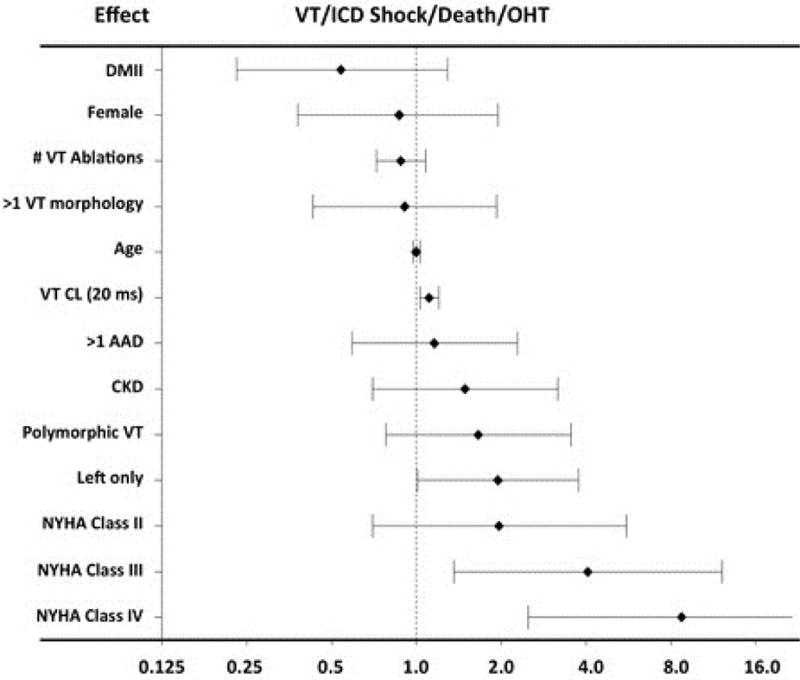

Finally, for the combined endpoint of ICD shock, OHT, and death, on univariable analysis, age, advanced NYHA class, a longer VT cycle length, diabetes mellitus, CKD, >1 anti-arrhythmic drug, and a left-only procedure proved statistically significant (Online Table 3). On Cox multiple regression analysis, advanced NYHA class had the highest hazard ratio: NYHA class III with an HR of 4.1 (95% CI: 1.36 to 12.2; p = 0.012) and NYHA class IV an HR of 8.8 (95% CI: 2.5 to 30.9; p < 0.001) (Central Illustration). Furthermore, every incremental increase in VT cycle length of 20 ms (HR: 1.11; 95% CI: 1.03 to 1.20; p = 0.005) and a left-sided only procedure (HR: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.01 to 3.76; p = 0.047) also were independent variables associated with recurrent ICD shocks, transplant, or death. Data from multiple imputation analysis for VT cycle length showed a significant effect on the combined outcome of sustained VT or ICD shock for every 20 m/sec increase in VT cycle length (HR: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.22; p < 0.004).

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Pre-procedural Variables Associated With VT-free Transplant-free Survival after CSD.

Patients with structural heart disease and recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias (VT) underwent cardiac sympathetic denervation (CSD) and were assessed for VT or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shock, death, or orthoptopic heart transplantation (OHT). On mulitvariable analysis, advanced New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, longer VT cycle lengths (CL), and a left-sided only procedure predicted the combined endpoint. AAD = antiarrhythmic drug; CI = confidence interval; CKD = chronic kidney disease; DMII = type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hazard ratio for VT CL refers to every 20 ms increase in cycle length.

To evaluate whether the hazard ratios of left CSD were driven by patient factors that may not have been assessed in the final multivariable model, a comparison of patient characteristics between bilateral versus left CSD patients was performed (Online Table 4). This analysis identified 2 additional variables that were statistically significant: left CSD patients: prior cardiac surgery and hyperlipidemia. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis was performed by adding these 2 variables into the final model and adjusting for their effects. This analysis showed that left CSD continued to be independently associated with poorer outcomes of recurrent VT or ICD shock, death, and heart transplantation (HR: 2.12; 95% CI: 1.09 to 4.12; p < 0.027) (Online Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

In the largest series of patients with refractory VT undergoing CSD, we showed an 88% reduction in ICD shocks along with an ICD shock-free survival of 50% at 1 year. These patients (75% presenting with VT storm), referred for CSD to one of several experienced centers, had a cardiac transplant/mortality rate of 25% at 1 year. The primary characteristics independently associated with sustained VT or ICD shock recurrence were NYHA class III or IV and longer VT cycle lengths. A left-sided only procedure independently predicted a poorer ICD shock-free survival compared to bilateral CSD in this population.

ICD shocks have been shown to increase morbidity and mortality and decrease quality of life (4,16). Furthermore, ICD shocks appear to shift the mode of death toward increased nonarrhythmic mortality, potentially by worsening HF (17), while freedom from VT and ICD shocks after successful catheter ablation has been associated with improved mortality (18). Therefore, the 88% reduction in ICD shocks in patients who underwent CSD at a mean follow-up of 1.5 ± 1.4 years compared to the year prior to the procedure is noteworthy. Furthermore, an ICD shock-free survival of 58% at 1 year and 50% at completion of follow-up was observed even though many study patients had been on multiple antiarrhythmic medications and had undergone a median of 1.3 VT ablation procedures, with 64% demonstrating multiple VT morphologies and 75% having a history of VT storm.

The autonomic nervous system plays a key role in both initiation and persistence of ventricular arrhythmias (1,2). Neuromodulatory therapies, including CSD, spinal cord stimulation (19,20), and renal denervation (21–23), are emerging as potential therapeutic options to treat ventricular arrhythmias that have proven refractory to antiarrhythmic medications and catheter ablation. Left-sided CSD has been shown to benefit patients with long QT syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic VT (13,24,25). A previous single-center study evaluated outcomes of CSD in a series of 41 patients with VT storm or refractory VT, and showed a >80% reduction in ICD shocks with a 48% ICD shock-free survival rate at 1 year for the combined outcomes of both left and bilateral procedures (11). This earlier study demonstrated a lower ICD shock-free survival in patients who had undergone a left-sided only procedure, but it was not powered to identify factors associated with outcomes. Our multicenter study was initiated to address these questions, and the 1-year ICD shock-free survival rate was similar at 50% for the combined outcome of left and bilateral procedures. The primary characteristics independently associated with ICD shock, OHT, and death were NYHA class III or IV HF, as well as longer VT cycle lengths, and left-side only CSD. The fact that NYHA class is an important predictor of recurrent VT and survival is not surprising, and has been shown to be true in other studies, including those of patients undergoing catheter ablation for VT (18,26,27). This study found that patients with advanced NYHA class, particularly class IV, might not derive the same benefit. It also demonstrated that CSD should be potentially considered earlier, rather than later, in the disease course in patients with VT and cardiomyopathy, before the development and progression of severe HF.

In this study, longer VT cycle lengths were also a predictor of ICD shock recurrence as well as death and cardiac transplantation. On multivariable analysis, every increase in cycle length of 20 ms increased the HR for sustained VT or ICD shock recurrence by 13%. The median cycle length of the VT observed in patients who recurred was 400 ms versus 300 ms in those with no recurrence. Therefore, in patients with VT cycle lengths >400 ms (<150 beats/min), the benefit of CSD is less clear. The lack of benefit in patients with very long VT cycle lengths is intriguing, but may be related to an underlying substrate with extensive scar or a metabolically compromised heart, where the autonomic-sympathetic nervous system is not the primary driver of arrhythmogenesis and could represent a subgroup that needs OHT or mechanical support as destination therapy or bridge to transplant.

In this population, there was no difference in outcomes for patients with ICM versus NICM. However, most patients in this study (63%) had NICM and these patients are known to have heterogeneous underlying etiologies. Consequently, patients with NICM traditionally present with a more challenging substrate for VT ablation, harboring epicardial, basal, and intramural scars, leading to less successful catheter ablation outcomes (28). Therefore, the fact that more patients with NICM were offered CSD is not unexpected and the procedure might be a more appealing option in this population.

The mechanism behind the benefit of CSD is likely related to both disruption of afferent as well as efferent sympathetic fibers (29–33). Direct sympathetic stimulation with isoproterenol and reflex sympathetic stimulation via infusion of nitroprusside in patients with ICM increased heterogeneity in action potential duration (34), worsening the substrate for reentry. Right, left, and bilateral stellate ganglia stimulation increased dispersion of repolarization and T-peak to T-end interval, a marker of sudden cardiac death (35–38). Stellate ganglia stimulation can cause early and late depolarizations (39,40). In infarcted porcine hearts, bilateral CSD mitigated dispersion of repolarization in the setting of sympathetic activation and decreased VT inducibility acutely (7). In this study, patients with bilateral CSD had longer sustained VT or ICD shock- and OHT-free survival compared to left CSD, although left CSD was not an independent characteristic associated with ICD shock recurrence alone. It is possible that patients with bilateral CSD derived an underlying disease-modifying benefit from the greater sympathetic efferent and afferent disruption that a bilateral procedure provides, similar to beta-blockers, altering the course of the underlying heart disease. It is known that both right and left stellate and thoracic ganglia provide significant innervation to both right and left ventricular myocardium (36,38,41–44). Furthermore, pathological neural remodeling due to myocardial infarction can occur in both stellate ganglia (45). Therefore, it is possible that, unlike patients with channelopathies who have structurally normal hearts and less neural remodeling, the traditional approach of left CSD may be inadequate in patients with significant SHD. The theoretical concerns of interrupting most of the sympathetic nerve fibers to the heart with bilateral CSD is mitigated by the finding that cardiac innervation is provided by neurons in the middle cervical ganglia, which remain intact after bilateral CSD (7,46).

STUDY LIMITATIONS

This study is retrospective and represented outcomes at specialized centers experienced in performing CSD. Therefore, the results may not be directly applicable to centers that do not perform this procedure frequently. Furthermore, although all patients underwent CSD using a video-assisted thorascopic approach, individual variability across centers might exist. Finally, ICD programming was not uniform across patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Cardiac sympathetic denervation decreased recurrence and burden of sustained VT and ICD shocks, with an ICD shock-free survival of 50% at 1 year in patients with refractory VT or VT storm. Approximately one-third of patients no longer took antiarrhythmic medication at follow-up. Major characteristics associated with less successful outcomes after CSD were advanced HF and longer VT cycle lengths, while patients with bilateral CSD had a better ICD shock-free survival compared to patients with left-only procedures. Given that ICD shocks have been strongly associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients with cardiomyopathy, and that worsened HF at the time of CSD portends a much worse prognosis, it is plausible that use of CSD earlier in the disease course can further improve outcomes. This study highlighted the need for prospective randomized clinical trials to examine the impact of CSD in this very high-risk group of patients.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN PATIENT CARE

In patient with structural heart disease and refractory ventricular arrhythmias the burden of sustained VT and frequency of ICD shocks are reduced by cardiac sympathetic denervation, but the response is influenced by the patient’s functional status and VT cycle length. Those with advanced HF symptoms and long VT cycle lengths derive less benefit from denervation.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK

Randomized trials are needed to better assess the efficacy of CSD in patients with structural heart disease and refractory VT.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Sitaram Vangala, MS and Chi-Hong Tseng, PhD at the UCLA Department of Medicine Statistics Core for their assistance and input in the statistical analysis of the data.

This study was supported by NIH1DP2HL132356 and AHA 11FTF755004 to MV and NHLBI R01HL084261 and NIHOT2OD023848 to KS. During the duration of the study, Dr. Shivkumar reports receiving grants from National Institutes of Health, Common Fund and NHLBI, grants from Glaxo Smith Kline. In addition, he has a patent related to neuroscience pending.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- ATP

antitachycardia pacing

- CSD

cardiac sympathetic denervation

- ICD

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- ICM

ischemic cardiomyopathy

- NICM

nonischemic cardiomyopathy

- OHT

orthoptopic heart transplantation

- SHD

structural heart disease

- VT

ventricular tachyarrhythmia

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: There are no other disclosures for any of the other authors related to this study.

References

- 1.Vaseghi M, Shivkumar K. The role of the autonomic nervous system in sudden cardiac death. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;50:404–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zipes DP, Rubart M. Neural modulation of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:108–13. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrmann C, von zur Muhen F, Schaumann A, et al. Standardized assessment of psychological well-being and quality-of-life in patients with implanted defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1997;20:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1997.tb04817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, et al. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1009–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S, Tedrow UB, Stevenson WG. Adjunctive Interventional Techniques When Percutaneous Catheter Ablation for Drug Refractory Ventricular Arrhythmias Fail: A Contemporary Review. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10:e003676. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.003676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shivkumar K, Ajijola OA, Anand I, et al. Clinical neurocardiology defining the value of neuroscience-based cardiovascular therapeutics. J Physiol. 2016;594:3911–54. doi: 10.1113/JP271870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irie T, Yamakawa K, Hamon D, Nakamura K, Shivkumar K, Vaseghi M. Cardiac sympathetic innervation via middle cervical and stellate ganglia and antiarrhythmic mechanism of bilateral stellectomy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312:H392–H405. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00644.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz PJ, Stone HL. Left stellectomy in the prevention of ventricular fibrillation caused by acute myocardial ischemia in conscious dogs with anterior myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1980;62:1256–65. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.62.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourke T, Vaseghi M, Michowitz Y, et al. Neuraxial modulation for refractory ventricular arrhythmias: value of thoracic epidural anesthesia and surgical left cardiac sympathetic denervation. Circulation. 2010;121:2255–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.929703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz PJ, Motolese M, Pollavini G, et al. Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death After a First Myocardial Infarction by Pharmacologic or Surgical Antiadrenergic Interventions. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1992;3:2–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaseghi M, Gima J, Kanaan C, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias or electrical storm: intermediate and long-term follow-up. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:360–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoonmaker FW, Carey T, Grow JB., Sr Treatment of tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias by cardiac sympathectomy and permanent ventricular pacing. Ann Thorac Surg. 1975;19:80–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)65737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collura CA, Johnson JN, Moir C, Ackerman MJ. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation for the treatment of long QT syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia using video-assisted thoracic surgery. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:752–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marhold F, Izay B, Zacherl J, Tschabitscher M, Neumayer C. Thoracoscopic and anatomic landmarks of Kuntz’s nerve: implications for sympathetic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1653–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramsaroop L, Partab P, Singh B, Satyapal KS. Thoracic origin of a sympathetic supply to the upper limb: the ‘nerve of Kuntz’ revisited. J Anat. 2001;199:675–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19960675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moss AJ, Schuger C, Beck CA, et al. Reduction in inappropriate therapy and mortality through ICD programming. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2275–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohnloser SH, Kuck KH, Dorian P, et al. Prophylactic use of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2481–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tung R, Vaseghi M, Frankel DS, et al. Freedom from recurrent ventricular tachycardia after catheter ablation is associated with improved survival in patients with structural heart disease: An International VT Ablation Center Collaborative Group study. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1997–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Issa ZF, Zhou X, Ujhelyi MR, et al. Thoracic spinal cord stimulation reduces the risk of ischemic ventricular arrhythmias in a postinfarction heart failure canine model. Circulation. 2005;111:3217–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.507897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopshire JC, Zhou X, Dusa C, et al. Spinal cord stimulation improves ventricular function and reduces ventricular arrhythmias in a canine postinfarction heart failure model. Circulation. 2009;120:286–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.812412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armaganijan LV, Staico R, Moreira DA, et al. 6-Month Outcomes in Patients With Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators Undergoing Renal Sympathetic Denervation for the Treatment of Refractory Ventricular Arrhythmias. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:984–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linz D, Wirth K, Ukena C, et al. Renal denervation suppresses ventricular arrhythmias during acute ventricular ischemia in pigs. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1525–30. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Remo BF, Preminger M, Bradfield J, et al. Safety and efficacy of renal denervation as a novel treatment of ventricular tachycardia storm in patients with cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:541–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Ferrari GM, Dusi V, Spazzolini C, et al. Clinical Management of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: The Role of Left Cardiac Sympathetic Denervation. Circulation. 2015;131:2185–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Cerrone M, et al. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation in the management of high-risk patients affected by the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2004;109:1826–33. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000125523.14403.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Della Bella P, Baratto F, Tsiachris D, et al. Management of ventricular tachycardia in the setting of a dedicated unit for the treatment of complex ventricular arrhythmias: long-term outcome after ablation. Circulation. 2013;127:1359–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevenson WG, Wilber DJ, Natale A, et al. Irrigated radiofrequency catheter ablation guided by electroanatomic mapping for recurrent ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction: the multicenter thermocool ventricular tachycardia ablation trial. Circulation. 2008;118:2773–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.788604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dinov B, Arya A, Bertagnolli L, et al. Early referral for ablation of scar-related ventricular tachycardia is associated with improved acute and long-term outcomes: results from the Heart Center of Leipzig ventricular tachycardia registry. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:1144–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irie T, Yamakawa K, Hamon D, Nakamura K, Shivkumar K, Vaseghi M. Cardiac sympathetic innervation via the middle cervical and stellate ganglia and anti-arrhythmic mechanism of bilateral stellectomy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312:H392–405. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00644.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalsa SS, Shahabi L, Ajijola OA, Bystritsky A, Naliboff BD, Shivkumar K. Synergistic application of cardiac sympathetic decentralization and comprehensive psychiatric treatment in the management of anxiety and electrical storm. Front Integr Neurosci. 2014;7:98. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malliani A, Lombardi F, Pagani M, Recordati G, Schwartz PJ. Spinal sympathetic reflexes in the cat and the pathogenesis of arterial hypertension. Clin Sci Mol Med Suppl. 1975;2:259s–60s. doi: 10.1042/cs048259s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malliani A, Recordati G, Schwartz PJ. Nervous activity of afferent cardiac sympathetic fibres with atrial and ventricular endings. J Physiol. 1973;229:457–69. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz PJ, Foreman RD, Stone HL, Brown AM. Effect of dorsal root section on the arrhythmias associated with coronary occlusion. Am J Physiol. 1976;231:923–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.3.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaseghi M, Lux RL, Mahajan A, Shivkumar K. Sympathetic stimulation increases dispersion of repolarization in humans with myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1838–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01106.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Opthof T, Coronel R, Vermeulen JT, Verberne HJ, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ. Dispersion of refractoriness in normal and ischaemic canine ventricle: effects of sympathetic stimulation. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:1954–60. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.11.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Opthof T, Misier AR, Coronel R, et al. Dispersion of refractoriness in canine ventricular myocardium. Effects of sympathetic stimulation. Circ Res. 1991;68:1204–15. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.5.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaseghi M, Yamakawa K, Sinha A, et al. Modulation of regional dispersion of repolarization and T-peak to T-end interval by the right and left stellate ganglia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H1020–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00056.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yagishita D, Chui RW, Yamakawa K, et al. Sympathetic nerve stimulation, not circulating norepinephrine, modulates T-peak to T-end interval by increasing global dispersion of repolarization. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:174–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ben-David J, Zipes DP. Differential response to right and left ansae subclaviae stimulation of early afterdepolarizations and ventricular tachycardia induced by cesium in dogs. Circulation. 1988;78:1241–50. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.5.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Priori SG, Mantica M, Schwartz PJ. Delayed afterdepolarizations elicited in vivo by left stellate ganglion stimulation. Circulation. 1988;78:178–85. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Opthof T, Dekker LR, Coronel R, Vermeulen JT, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ. Interaction of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system on ventricular refractoriness assessed by local fibrillation intervals in the canine heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:753–9. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.5.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaseghi M, Zhou W, Shi J, et al. Sympathetic innervation of the anterior left ventricular wall by the right and left stellate ganglia. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janes RD, Brandys JC, Hopkins DA, Johnstone DE, Murphy DA, Armour JA. Anatomy of human extrinsic cardiac nerves and ganglia. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:299–309. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90908-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawashima T. Anatomy of the cardiac nervous system with clinical and comparative morphological implications. Anat Sci Int. 2011;86:30–49. doi: 10.1007/s12565-010-0096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ajijola OA, Yagishita D, Reddy NK, et al. Remodeling of stellate ganglion neurons after spatially targeted myocardial infarction: Neuropeptide and morphologic changes. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1027–35. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armour JA. Activity of in situ middle cervical ganglion neurons in dogs, using extracellular recording techniques. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1985;63:704–16. doi: 10.1139/y85-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.