Abstract

Radiotherapy is an extensively used treatment modality in the clinic and can kill malignant cells by generating cytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS). Unfortunately, excessive dosages of radiation are typically required because only a small proportion of the radiative energy is adsorbed by the soft tissues of a tumor, which results in the nonselective killing of normal cells and severe systemic side effects. An efficient nanosensitizer that makes cancer cells more sensitive to radiotherapy under a relatively low radiation dose would be highly desirable.

Methods: In this study, we developed a Gd-doped titania nanosensitizer that targets mitochondria to achieve efficient radiotherapy. Upon X-ray irradiation, the nanosensitizer triggers a “domino effect” of ROS accumulation in mitochondria. This overabundance of ROS leads to mitochondrial permeability transition and ultimately irreversible cell apoptosis. Confocal laser imaging, western blotting and flow cytometry analysis were used to explore the biological process of intrinsic apoptosis induced by the nanosensitizer. Clonogenic survival assay, cell migration and invasion experiments were employed to evaluate the radiosensitizing effect of the nanosensitizer in vitro. Finally, to evaluate the therapeutic outcome of the nanosensitizer in vivo, MCF-7 tumor model was used.

Results: Confocal laser images and western blotting data demonstrated that the nanosensitizer in conjunction with X-ray irradiation could induce cell apoptosis in ROS-mediated apoptotic signal pathways. A clonogenic survival assay revealed that cells treated with the prepared nanosensitizer exhibited a lower number of viable cell colonies than that of the nontargeted group under X-ray irradiation. Notably, with only a single dose of radiotherapy, the mitochondria-targeted nanosensitizer elicited the complete ablation of tumors in a mouse model.

Conclusion: The designed nanosensitizer in combination with X-ray radiation exposure could be used for radiotherapy against cancer in living cells and in vivo. Moreover, the nanosensitizer with mitochondria targeting played a pivotal role in triggering a “domino effect” of ROS and cell apoptosis. The current strategy could provide new opportunities in designing efficient radiosensitizers for future cancer therapy.

Keywords: nanosensitizer, mitochondria-targeting, reactive oxygen species, radiotherapy, cancer

Introduction

Radiotherapy is a first-line therapy for cancers; it involves the delivery of high-energy doses of ionizing radiation to the tumor site to induce the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can destroy cancer cells 1,2. ROS play an extremely important role in promoting radiation-induced cell apoptosis during radiotherapy because large augmentation of ROS not only cause DNA damage but also dramatically hinder DNA self-repair by cancer cells 3,4. However, radiotherapy is still subject to the limitations of insufficient ROS that typically arise in clinical cancer therapy due to the low radiation energy absorption coefficients of tumors themselves 5,6. To achieve a better therapeutic effect, excessive X-ray irradiation is commonly applied to maximize apoptosis of the tumor cells, but this leads to severe side effects in normal tissues. Therefore, to maximally reduce the dose of radiation for optimizing the efficiency of radiotherapy and minimizing side effects, the design of a radiosensitization system that causes the accumulation of substantial ROS in living cells upon X-ray irradiation is urgently needed.

Recently, tremendous efforts have been made to develop various nanomaterials containing high-Z elements 7,8, such as gold or rare earth nanoparticles, to enhance radiotherapy. High-Z nanomaterials deposit radiative energy within tumors and generate ROS free radicals by scattering γ- or X-rays while under irradiation 9-11. However, most high-Z nanomaterials function mainly in the cytoplasm to generate ROS, which significantly weakens their radiation-induced therapeutic effect 12,13. Mitochondria are susceptible to excessive ROS; their exposure leads to uncontrolled ROS formation and triggers the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis 14,15. Developing mitochondrion-targeted radiosensitizers could induce perturbations of ROS homeostasis and enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to ionizing radiation. Our group previously reported a nanocomposite based on a mitochondria-targeted agent with the goal of producing substantial ROS for cancer radiotherapy, but complex synthetic processes and uncontrollable morphologies limited clinical translation 16. Therefore, a nanosensitizer with excellent photoactivity and a simple preparation method that can activate the domino-like effect of ROS-induced bursting of living cells upon a single X-ray ionization event is urgently required for clinical radiotherapy.

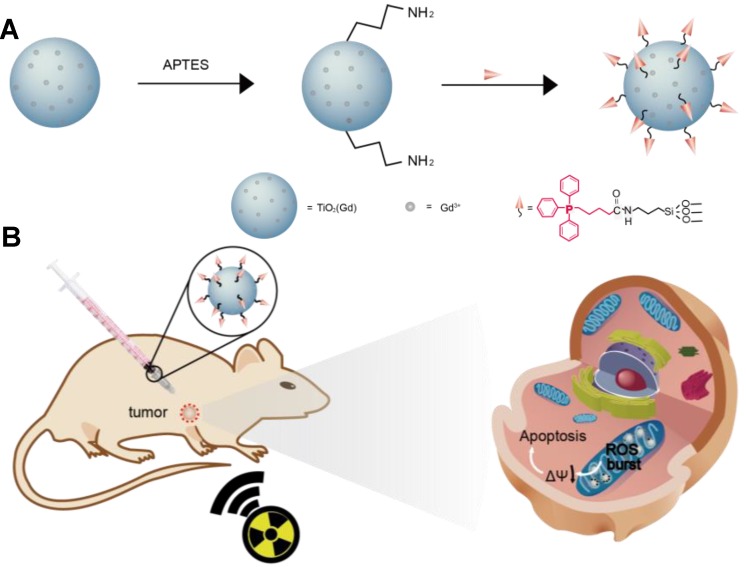

Herein, we report the use of Gd-doped titania nanoparticles (TiO2(Gd) NPs) as a nanosensitizer that features specific mitochondria targeting and a high efficacy of tumor ablation through excessive ROS production (Figure 1). TiO2(Gd) NPs prepared with a one-pot method can produce a flux of ROS following X-ray activation due to their enhanced photoelectric cross section with high-energy X-rays 17. The targeting moiety, 4-carboxybutyl triphenylphosphonium bromide (TPP), ensures that the nanosensitizer selectively enters mitochondria. In contrast to cytoplasm-generated ROS strategies, this mitochondria-targeted nanosensitizer can induce the successive accumulation of ROS in mitochondria under X-ray irradiation, which further leads to mitochondrial disorder and the nonreversible apoptosis of cancer cells. The nanosensitizer not only greatly amplifies the antitumor efficacy of radiotherapy and dramatically reduces the required X-ray irradiation dose but also offers a great potential for clinical applications.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of (A) the synthesis of the nanosensitizer (TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs). (B) Mitochondria-targeted nanosensitizer for radiotherapy to trigger mitochondrial ROS accumulation.

Methods

Synthesis of doped titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2(Gd) NPs)

The TiO2(Gd) NPs were synthesized according to the sol-gel method. Typically, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 3.0 mol% gadolinium (III) nitrate pentahydrate and 5 mL tetrabutyl titanate (TBOT) were resuspended in 20 mL dry ethanol. After stirring for 10 min, another mixture of 6 mL glacial acetic acid and 1.5 mL water was added in a dropwise manner to the first mixture solution. Subsequently, the solution was stored at 60 °C for 24 h in an oven to produce a colloidal solution. Following ageing 12 h at 80 °C, a yellowish solid product was calcined for 3 h at 700 °C to remove impurities.

Intracellular colocalization profile of the NPs in MCF-7 cells

MCF-7 cells were first cultured in confocal dishes for 24 h in 5% CO2 at 37 °C in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Biological Industries, Israel) culture medium. Next, TiO2(Gd)-TPP-IR806 or TiO2(Gd)-IR806 (0.1 mg/mL) in DMEM was added to the confocal dishes. After incubation for 8 h, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Biological Industries, Israel) buffer twice to remove residual NPs. Next, Mito-Tracker Green (Invitrogen, USA) (MTG, 25 nM) was used to label mitochondria by incubation with the cells for 15 min. Confocal images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). The MTG was excited by a 488-nm laser, and the green emission was collected with a bandpass filter over the range of 500-550 nm; the IR806 was excited by a 633-nm laser, and the red emission from the NPs was collected with a bandpass filter over the range of 750-800 nm. The colocalization ratio was quantified using Image-Pro Plus Imaging software (Media Cybernetics, America).

Real-time monitoring of the superoxide anion (O2• -) in vitro

MCF-7 cells were first cultured in confocal dishes for 24 h in 5% CO2 at 37 °C in DMEM culture medium. Then, TiO2(Gd)-TPP-HE or TiO2(Gd)-HE (0.1 mg/mL) in DMEM was added to the confocal dishes. After incubation for 8 h, the cells were washed with PBS buffer to remove residual NPs, and 2 mL fresh DMEM was added. Under X-ray irradiation at 4 Gy, confocal images were acquired over 12 h at 2-h intervals from the same area by CLSM (excitation = 488 nm, emission = 500-550 nm).

Cell proliferation assay

A colony formation assay was used to assess the clonogenic capacities of MCF-7 cells (clonogenic assay). Cells (8×102) were cultured in 60-mm dishes for 24 h and subjected to different treatments (i.e., control, TiO2(Gd)-TPP, X-ray, TiO2(Gd)+X-ray and TiO2(Gd)-TPP+X-ray); the concentrations of TiO2(Gd)-TPP and TiO2(Gd) were 0.1 mg/mL, and the X-ray dose was 4 Gy. The cells were further incubated for 10 days. Finally, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution and stained with 0.2% crystal violet, and the colony numbers were calculated when colonies comprised more than 50 cells. The surviving fraction was calculated as follows: (surviving colonies) / (cells seeded × plating efficiency). The mean surviving fraction was obtained from three replicates.

In addition to clonogenic assay, CFSE (carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester) proliferation assay was utilized. Cells were first stained with a CFSE cell tracing reagent (Beyotime, Beijing), as instructed by the manufacturer´s protocol, and then divided into five parallel groups by cell counting using hemocytometer. 1×103 trypsinized cells were added into in each Petri dishes and further incubated for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were exposed to different treatment conditions (control, TiO2(Gd)-TPP, X-ray, TiO2(Gd)+X-ray, TiO2(Gd)-TPP+X-ray). The concentration of NPs was 0.1 mg/mL and the X-ray dose was 4 Gy. Following incubation for 7 days, the cells were digested and washed three times with PBS. The fluorescence intensity of CFSE in the cells was analyzed using an Image Stream Mark II imaging flow cytometry tool (MERCK, Germany) with a 488-nm laser.

Five groups of MCF-7 cells were treated with the following conditions: control, TiO2(Gd)-TPP, X-ray, TiO2(Gd)+X-ray, and TiO2(Gd)-TPP+X-ray. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with cyclosporine A (CsA, 1 μM) for 30 min. After treatment with 4 Gy of X-ray irradiation, the cells were further incubated for 10 days. Finally, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution and stained with 0.2% crystal violet. The colony numbers were calculated according to the methods mentioned above. The mean surviving fraction was obtained from three replicates.

In vivo therapeutic efficacy tests

MCF-7 cells (1×106) in 100 µL of serum-free RPMI 1640 were subcutaneously injected into the right flank region of female nude mice (Nanjing University, Nanjing) (approximately 4-6 weeks old, ∼18 g). The experiments were initiated when the tumor volume was approximately 80-100 mm3.

For the in vivo radiation therapy, the mice were divided into the following 5 groups: (i) control, (ii) TiO2(Gd)-TPP, (iii) X-ray, (iv) TiO2(Gd)+X-ray, and (v) TiO2(Gd)-TPP+X-ray. NPs were intratumorally injected into the tumor-bearing mice. The NP dose was 3 mg·kg-1 and the X-ray dose was 6 Gy, irradiated 8 h after NP injection. The tumor sizes and body weights were recorded every other day for 14 days after treatment (tumor volume = W2 × L / 2, where W is width and L is length).

Twelve hours after the aforementioned treatments, the mice were sacrificed, and the tumors were harvested for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. H&E staining was also applied to five major organs (i.e., liver, lung, spleen, kidney, and heart). Seven days after the treatments, the mice were sacrificed and the aforementioned major organs were harvested for staining.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of the radiosensitizers

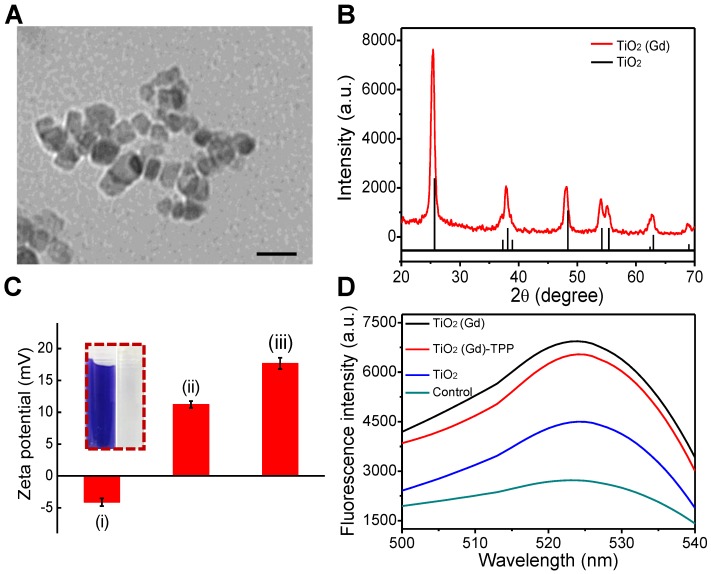

We synthesized titanium NPs doped with 1 mol% gadolinium (TiO2 (Gd) NPs) using a simple, one-pot method 18. The morphology of the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs were studied with transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Figure 2A), which revealed that the exhibited anomalistic sphericity, and the sizes were evaluated as suitable at approximately 20 nm. Energy dispersive spectra (EDX) disclosed that Gd was successfully doped in the TiO2 NPs (Figure S1) by showing significant peaks for Gd. Moreover, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra (Figure S2) 19 confirmed that the oxidation state Gd was trivalent. The crystalline phase of the TiO2 (Gd) NPs was determined using powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD; Figure 2B) and found to be a single-phase anatase, which entails a larger surface area of TiO2 (Gd) (the specific surface area was 119.4 m²/g, Figure S3) that can create additional free radicals. In addition, the PXRD results suggested that the synthetic procedure of the doped Gd in the fabricated TiO2 NPs did not cause any lattice distortions 20,21. Furthermore, due to the addition of Gd as a dopant, the NPs exhibited greatly enhanced X-ray radiation absorbance because their X-ray photon interaction cross section was significantly greater than that of pure TiO2 22,23. To improve the biocompatibility and further modify the NPs with TPP, the TiO2 (Gd) NPs were functionalized with amino groups by a treatment with (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES). The zeta potential of the TiO2 (Gd)-NH2 NPs changed to 11.2 ± 0.2 mV from -4.1 ± 0.1 mV after amino functionalization, which was attributed to the negatively charged hydroxyl group on the surface of the TiO2 (Gd) NPs 24,25. After the attachment of TPP onto the TiO2 (Gd)-NH2 NPs, the zeta potential reached 17.6 ± 0.1 mV. The changes of the NP surface charge demonstrated the successful completion of each synthesis step (Figure 2C). In addition, the fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) data of the TiO2 (Gd)-NH2 NPs confirmed that the amino groups were successfully modified on the surface of the TiO2 (Gd) NPs (Figure S4). Furthermore, the surface modification of TiO2 (Gd) NPs did not change its physicochemical properties according to the EDX and XPS spectra in Figure S5 and Figure S2B, respectively.

Figure 2.

Characterization and ROS generation of the nanosensitizer. (A) A TEM image of TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs; scale bar is 40 nm. (B) PXRD patterns of TiO2 (Gd) NPs. The vertical line represents anatase TiO2 (ICDD-PDF no. 21-1272). (C) Zeta potentials of each step modification: (i) TiO2 (Gd) NPs; (ii) TiO2 (Gd)-NH2 NPs; (iii) TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs; Insert: ninhydrine assay of TiO2 (Gd)-NH2-precipitation (right) and the supernatant solution (left) after centrifugation. (D) Detection of O2•- by DBZTC (λex = 490 nm, λem = 525 nm) after X-ray irradiation.

Next, the ability to produce the superoxide anion (O2• -) of the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs under X-ray activation was evaluated using 2-chloro-1,3-dibenzothiazolinecyclohexene (DBZTC) as a fluorescent probe 26. When DBZTC reacts with O2• -, the fluorescence intensity is enhanced. The influence of Gd content on the production of ROS by the TiO2 NPs was also studied. When increasing the content of Gd ions (0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 3.0 mol%), the fluorescence intensity of the DBZTC initially displayed an increase until the doping amount reached 1.0 mol% and then decreased upon further increases in the doping ion content (Figure S6). We identified a well-defined ratio between the number of Gd ions and the amount of titanium dioxide. A small amount of Gd ions doped into TiO2 improves its photocatalytic activity due to the formation of electron traps to enhance the separation of electron-hole pairs 19, 20. Once the content of Gd ions is excessively high (over 1.0 mol%), the photocatalytic activity decreases with increasing doping ion content, which is due to the narrowing of the space-charge region and the promotion of electron-hole pairs under photoactivation 27. Therefore, 1.0 mol% was chosen as the optimal doped amount. Moreover, the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs exhibited significantly enhanced fluorescence intensity relative to the pure TiO2 NPs under 4 Gy X-ray irradiation (Figure 2D), which indicated that TiO2 doped with 1.0 mol% Gd could facilitate O2• - production by effectively absorbing the irradiated X-ray photons. This process indicated the strong potential of these NPs to function as efficient radiosensitizers for enhanced radiotherapy.

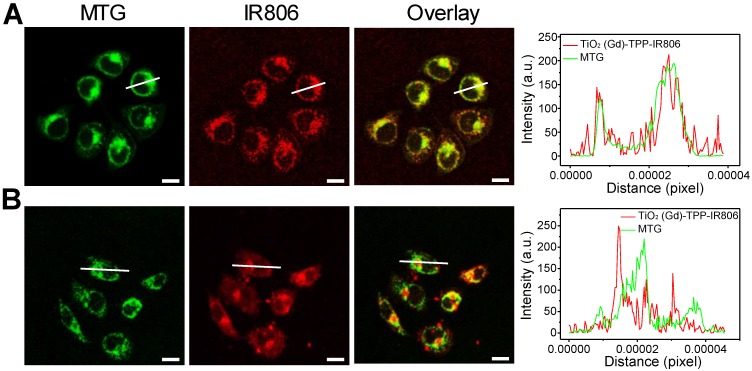

Optimization of the TPP concentration

The number of 4-carboxybutyl triphenylphosphonium bromide (TPP) groups was optimized based on the ability of the nanosensitizer to selectively target mitochondria 28,29. A series of TPP-linked TiO2 (Gd) NPs were prepared with various amounts of TPP (0, 16, 24, 32, and 40 μmol) added into 40-mL TiO2 (Gd) solution. The infrared dye IR806, which acts as a fluorescent label for NPs, was also modified on the surfaces of the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs. After incubating MCF-7 cells for 8 h at the same concentration (0.1 mg/mL), the fluorescence intensities of the cells were measured by CLSM followed by MTG labeling of mitochondria. As illustrated in Figure S7, the red fluorescence intensity of the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP-IR806 NPs was increased until the amount of TPP reached 32 μmol, and the red fluorescence overlapped the green fluorescence of MTG to create an orange-yellow signal. The results were also consistent with a monotonic improvement in the Pearson's correlation coefficient. Therefore, the actual TPP concentration associated with the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs in this group was confirmed to be 3.41 μmol/mg TiO2 (Gd) using UV-Vis spectra (Figure S8), and this concentration was chosen for the subsequent study. Moreover, Figure 3A further demonstrates that the radiosensitizers can be specifically localized in mitochondria based on fluorescence quantification of line scanning profiles between the radiosensitizers and MTG. In contrast, the intensity profiles of both the TiO2 (Gd)-IR806 NPs and MTG were quite different (Figure 3B). Moreover, the in vitro mitochondria-targeting ability of TiO2 (Gd)-TPP was determined by flow cytometry. MCF-7 cells were incubated with TiO2 (Gd)-IR806 or TiO2 (Gd)-TPP-IR806 for 8 h, and mitochondria were labeled with MTG before the imaging experiment. As shown in Figure S9, the bright detail similarity value when incubating with mitochondrial-targeted nanosensitizer was higher than that of the nontargeted groups, indicating that the nanosensitizer was indeed localized in mitochondria. These results demonstrated that the nanosensitizer selectively targeted mitochondria, which could aid future cancer therapy applications.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial targeting of the nanosensitizer under confocal imaging. Mitochondrial targeting of (A) TiO2 (Gd)-TPP-IR806 and (B) TiO2 (Gd)-IR806 under confocal imaging. Images of NPs (excitation = 633 nm, emission = 750-800 nm), Mito-Tracker Green (MTG) stained mitochondria (excitation = 488 nm, emission = 500-550 nm), the overlay channel of NPs and mitochondria (right). Scale bars are 15 µm; Quantification data of line scanning profiles in the corresponding confocal images (right).

The cellular uptake and internalization pathways were also investigated using two endocytosis inhibitors: chlorpromazine (10 μM), which is an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and ethylisopropylamiloride (EIPA) (50 μM), an inhibitor of macropinocytosis. As shown in Figure S10, relative to the control group, the fluorescence intensity was significantly decreased in cells treated with chlorpromazine, while no prominent changes were observed in cells treated with EIPA. These results demonstrated that the nanosensitizer might be mainly internalized via clathrin-mediated endocytic pathways.

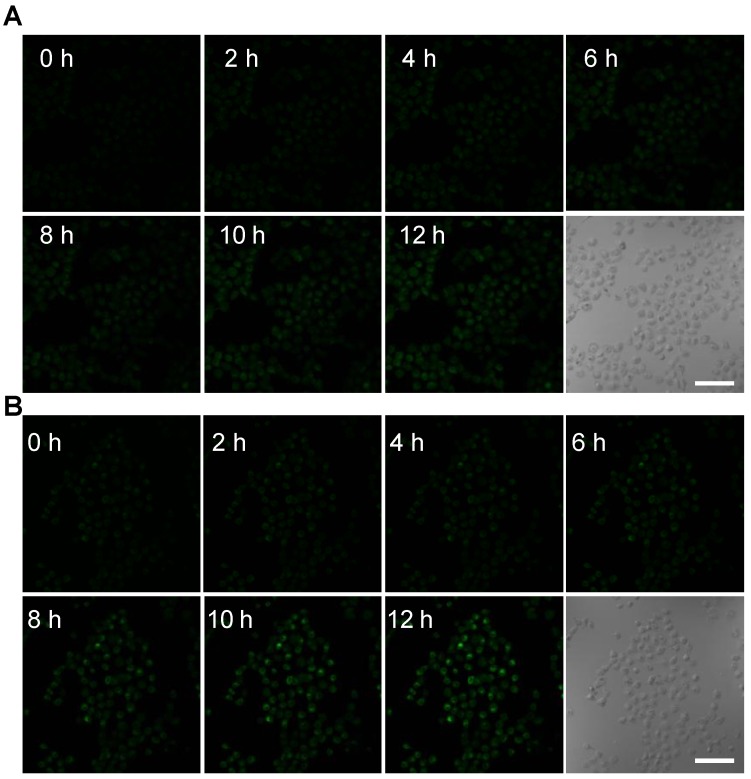

Real-time monitoring of intracellular O2• - burst

To further monitor the changes of ROS in real time at the subcellular level under X-ray irradiation, the mitochondrial O2• - levels were assessed using the common fluorescent probe hydroethidine (HE) 30. HE was anchored on the surfaces of the NPs (TiO2 (Gd)-HE and TiO2 (Gd)-TPP-HE NPs) by a covalent bond. After incubating with the NPs, MCF-7 cells were irradiated with a 4-Gy X-ray, and CLSM was immediately performed. The confocal images of the cells treated with TiO2 (Gd)-HE exhibited weak fluorescence signals at 12 h (Figure 4A and Figure S11), which demonstrated that the concentration of the generated O2• - did not reach the threshold of “mitochondrial criticality”. In contrast, a time-dependent increase in green fluorescence signals was obtained in the group of cells treated with TiO2 (Gd)-TPP-HE (Figure 4B and Figure S11), suggesting that ROS were continuously generated for up to several hours after only a single exposure to irradiation. Even after 12 h, a very bright fluorescence signal was still captured, which further proved that the ROS domino effect indeed occurred. Moreover, the in vitro intracellular O2• - generation was also quantitatively validated through flow cytometry analysis. As shown in Figure S12, the fluorescence intensity in cells increased over time, suggesting that ROS were continuously produced without further irradiation. In addition, after exposing cells to the various treatments, the •OH levels in mitochondria were also assessed by CLSM. Coumarin was chosen as a fluorescent indicator, which could readily react with •OH to generate the highly fluorescent product of 7-hydroxycoumarin. As shown in Figure S13, the fluorescence intensity significantly enhanced in the group of cells treated with TiO2 (Gd)-TPP under X-ray irradiation, suggesting successful •OH generation in tumor cells.

Figure 4.

Confocal images of nanosensitizer-treated MCF-7 cells for real-time detection of intracellular O2• - bursts under X-ray irradiation. MCF-7 cells were treated with (A) TiO2 (Gd)-HE or (B) TiO2 (Gd)-TPP-HE. Following X-ray irradiation, cell images were obtained at 2-h intervals for up to 12 h. Scale bars are 125 µm.

Cell proliferation assay

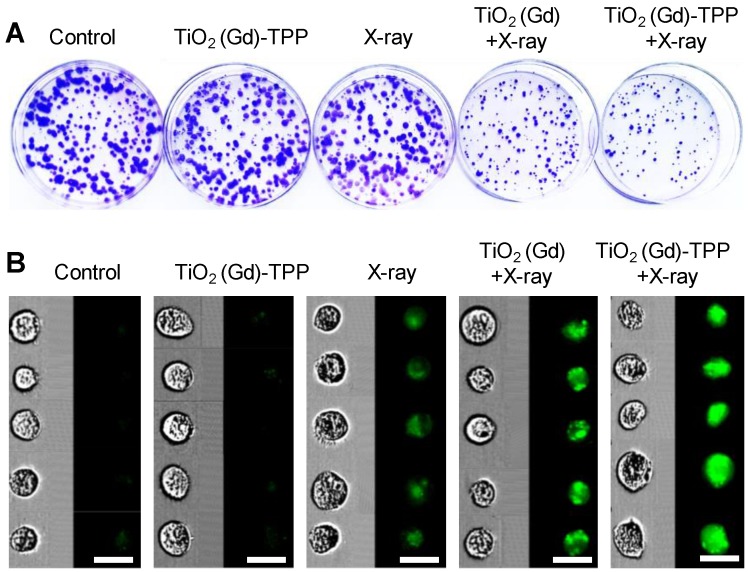

A clonogenic cell survival assay was subsequently employed to evaluate the radiosensitizing effect of the mitochondria-targeted radiosensitizers in vitro 31. Relative to cells unexposed to treatment, the cells treated with TiO2 (Gd)-TPP exhibited almost the same number of viable cell colonies, which indicated that the radiosensitizers had outstanding biocompatibility and did not affect cell proliferation (Figure 5A and S14A). Notably, the cells treated with TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray (4 Gy) exhibited a pronounced inhibition of cell colony formation, and the survival fraction was only 25.6%. The TiO2 (Gd)+X-ray (4 Gy) cells were also studied for comparison; their survival fraction was approximately 50%. Additionally, CFSE-based proliferation assays were applied to analyze cell proliferation under the different treatments 32. A conclusion similar to that obtained from the abovementioned clonogenic cell survival assay was reached (Figure 5B and S14B); the green fluorescence signal of the cells treated with TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray was much brighter than that of the cells in other groups, indicating that the inhibition of MCF-7 cells could be enhanced with the synergistic effect of TiO2 (Gd)-TPP and ionizing radiation. In addition, the sensitization enhancement ratios (SERs) of the treatments (i.e., X-ray, TiO2 (Gd)+X-ray and TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray) were characterized by the clonogenic assay. The SER corresponds to the ratio when 10% of the total cells are alive. As shown in Figure S15, “TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray” sensitized MCF-7 cells to ionizing radiation and achieved a higher SER value (1.7) than that of “TiO2 (Gd)+X-ray”, which was 1.1. These results suggested that ROS accumulation originating from mitochondria could cause cancer cells to self-destruct due to their increased radiosensitivity.

Figure 5.

Cell proliferation by clonogenic survival assay and CFSE staining. (A) Representative photographs of colony formation. Cells were treated with different conditions and then incubated for 10 days. Subsequently, cells were fixed, stained and imaged. The diameter of the culture dish is 60-mm. (B) Flow cytometry data of the cells labeled with CFSE. Cells were treated with different conditions and then incubated for 7 days. Subsequently, cells were digested and imaged using imaging flow cytometry (scale bars are 20 μm).

Verification of the biochemical mechanism of cell death

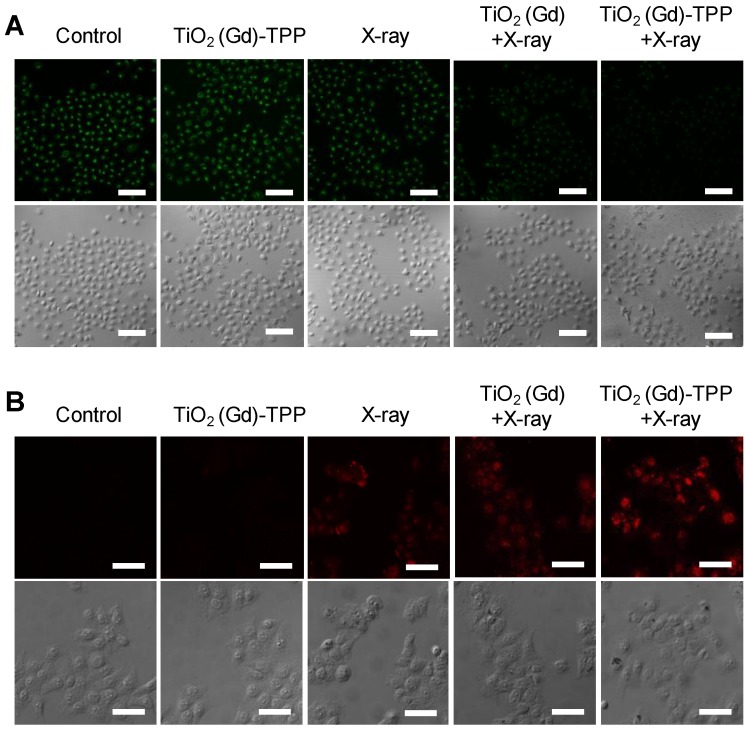

We performed experiments to explore the biological process of intrinsic apoptosis induced by the radiosensitizer. First, Rhodamine 123, a commercial indicator, was employed to monitor the changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) in living cells 33, 34. A decrease in Δψm occurs early in mitochondria-triggered apoptosis. As illustrated in Figure 6A and Figure S16, there were no prominent fluorescence signal changes in the control and TiO2 (Gd)-TPP groups and an approximately 30% decrease of fluorescence intensity in cells treated with X-ray irradiation. However, relative to cells in the TiO2 (Gd)+X-ray group, the fluorescence intensity of the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray group dramatically weaker (a decrease to ~ 51.5% vs. 25.2%, respectively), which suggested that the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs in combination with X-rays could induce apoptosis by damaging mitochondria. This process occurred because ROS accumulation in mitochondria activates an inner membrane anion channel (IMAC) and promotes the inner membrane permeability transition. Second, cyclosporine A (CsA), an agent that desensitizes the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), was used to clarify the apoptosis-related mechanism of mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization 35. The results of a clonogenic cell survival assay (Figure S17) revealed that the lowest number of viable cell colonies (20.2%) was formed in the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray group in the presence of CsA, which proved that the decrease of ∆ψm was induced by the synergistic effect of MPTP opening and IMAC activation. Third, immunofluorescent staining was applied to monitor the activity of caspase 3, which acts as a central regulator in cell apoptosis 36. As in Figure 6B, TiO2 (Gd)-TPP promoted the expression of caspase 3 more effectively in MCF-7 cells following a 4-Gy X-ray irradiation, which indicated that mitochondria played a key role in caspase-3-mediated apoptosis. To further understand the radiosensitization effect through the mitochondrial pathway, cytochrome C, caspase 8 and caspase 9 were also verified using an immunofluorescence staining method. As shown in Figure S18, the increased activity of cytochrome C, caspase 8 and caspase 9 were all detected when MCF-7 cells were loaded by TiO2 (Gd)-TPP and irradiated with 4-Gy X-rays. Moreover, as shown in Figure S19, cytochrome C in addition to caspase 3 and 9 were only minimally detectable from untreated cells. In contrast, the levels of cytochrome C as well as caspase 3 and 9 increased in the irradiated group with the treatment of the nanosensitizer. The results were consistent with the immunofluorescence results and further confirmed that the nanosensitizer in conjunction with X-ray irradiation could induce cell apoptosis in ROS-mediated apoptotic signal pathways.

Figure 6.

Detection of ∆ψm and imaging intracellular caspase 3. (A) Confocal images of ∆ψm by CLSM after cells were stained with Rhodamine 123 (λex = 488 nm, λem = 500-550 nm). Scale bars are 125 µm. (B) Images of immunofluorescence staining of caspase 3 by CLSM. Confocal images were acquired (λex = 633 nm, λem = 640-700 nm) after cells received different treatments (scale bars are 50 µm).

Combined with a previously reported research, the biochemical mechanism was well established. When cells loaded with TiO2 (Gd)-TPP are exposed to X-rays, the accumulation of ROS in mitochondria is enhanced. As the increase of ROS reaches a certain level, the “oxidative stress” that occurs in mitochondria can initiate a mitochondria-induced intrinsic apoptotic pathway, which is highly related with cascade reactions 37, including the following: (i) the transition of mitochondrial permeability, (ii) the decrease of ∆ψm, and (iii) the activation of caspase 3 38. Moreover, these caspases can impair the mitochondrial electron transport chain and induce an ongoing ROS accumulation, which further leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and an irreversible apoptosis of cells.

Cell migration and invasion experiments

The combined effects of TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs and X-ray (4 Gy) irradiation on the migration and invasion capabilities of MCF-7 cells were also studied using wound-healing assays and cell invasion assays 39. The scratched region in the group of TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray was wider than that in the cells treated with TiO2 (Gd)+X-ray or with X-ray at 36 h after the creation of the scratch (Figure S20A-B), which suggested that the migration ability was significantly influenced by the nanosensitizer under X-ray irradiation. Similar results were obtained in the cell invasion analyses (Figure S20C-D); the cells treated with TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray displayed the minimum quantity of invasive cells (33.0%). This finding demonstrated that the nanosensitizer sensitized MCF-7 cells to ionizing radiation and exhibited a substantial capability to inhibit cancer cell migration and invasion under X-ray irradiation.

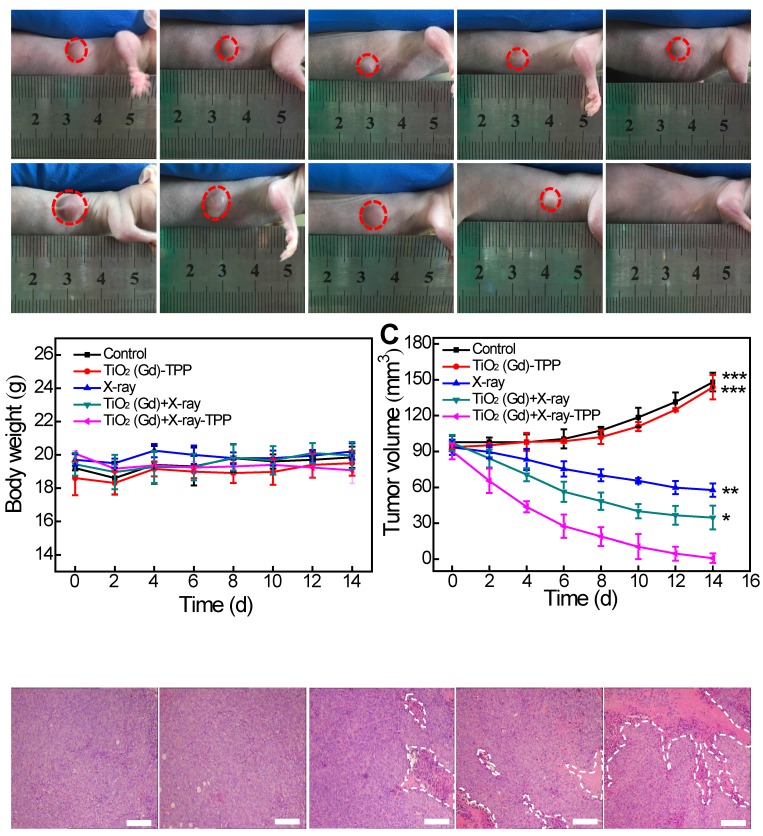

Therapeutic effects of the radiosensitizers in vivo

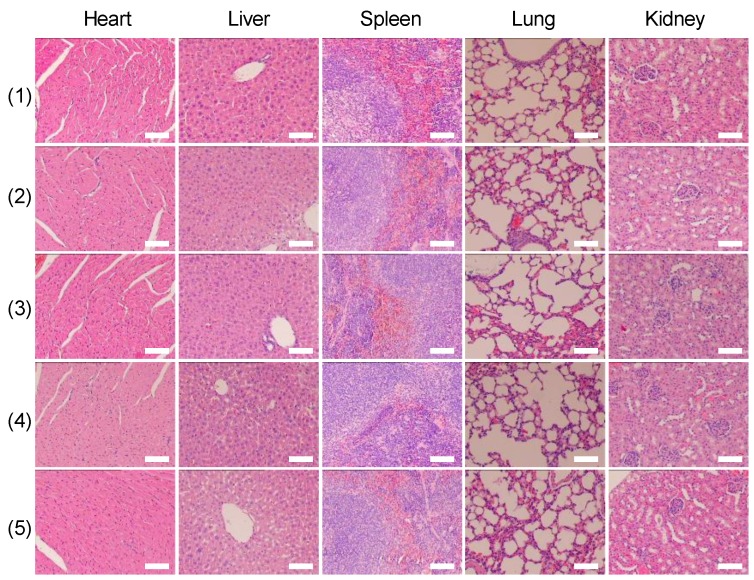

Finally, we investigated whether the strategy of using X-rays to trigger ROS accumulation in mitochondria would enhance radiotherapy-induced tumor cell killing in vivo. In our experiment, MCF-7 xenograft tumor-bearing mice were created in five groups: Group 1(control; PBS only), Group 2 (TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs without irradiation), Group 3 (X-ray irradiation alone), Group 4 (TiO2 (Gd)+X-ray), and Group 5 (TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray). NPs (3 mg·kg-1) were intratumorally injected into the mice before a 6-Gy X-ray radiation was applied for radiotherapy. As indicated in Figure 7A and 7C, relative to the mice that were treated with PBS or TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs alone, the mice that received only the 6-Gy dose of irradiation exhibited slower tumor growth due to the therapeutic efficacy of tumor irradiation. While receiving identical X-ray radiation doses, the mice that were injected with TiO2 (Gd) or TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs both exhibited tumor growth inhibition. Notably, radiotherapy was much more effective in the group of the mice that received TiO2 (Gd)-TPP NPs injection, and the tumors had completely disappeared at 14 days post-treatment. These results clearly illustrated that the nanosensitizer offered additional benefits that enhanced radiotherapy due to mitochondrial collapse via ROS accumulation under X-ray irradiation. Furthermore, the greatest number of necrotic tumor cells was found in the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP with X-ray group based on H&E staining of tumor slices, which further confirmed its therapeutic efficacy in vivo (Figure 7D). Body weight is an essential parameter for evaluating the toxicity of NPs to the body. The body weights of the groups exhibited no significant changes over 14 days, which implied that the treatments were free of side effects (Figure 7B). Additionally, H&E staining of five major excised organs (i.e., liver, lung, kidney, spleen, and heart) revealed no histopathological abnormalities in any group (Figure 8), which suggested that the nanosensitizer was biocompatible since it did not induce any systemic toxicity.

Figure 7.

In vivo anti-tumor efficacy study of the nanosensitizer in a mouse model. (A) Photographs of the mice before (Day 0) and after (Day 14) various indicated treatments. The dosage of NPs was 3 mg·kg-1, followed by X-ray irradiation (6 Gy). (B) Body weight changes of mice in various treatment groups. (C) Tumor volume changes of the treatment groups. (D) Tumor H&E staining for the treatment groups. Tumor slices were obtained after treatment for 12 h (scale bars are 200 μm). ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 relative to the TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray group.

Figure 8.

H&E-stained images of tissue slices of major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney). Mice received different treatments (1) control; (2) TiO2 (Gd)-TPP; (3) X-ray; (4) TiO2 (Gd)+X-ray; (5) TiO2 (Gd)-TPP+X-ray) and major organs were excised seven days after the treatments. Scale bars are 100 μm.

Conclusions

In summary, a nanosensitizer based on mitochondria-targeted, Gd-doped titania has been prepared and used for efficient radiotherapy. The nanosensitizer could effectively produce ROS due to the large photoelectric cross section for X-rays. Intracellular colocalization experiments indicated that the nanosensitizer could selectively target mitochondria. When irradiated with X-rays, the ROS generated in mitochondria led to a saturation of the antioxidant capacities of cancer cells, which triggered mitochondrial dysfunction and a ROS “domino effect”. A clonogenic survival assay revealed that cells treated with the prepared nanosensitizer exhibited a lower number of viable cell colonies than that of the nontargeted group under X-ray irradiation. Notably, the nanosensitizer in combination with a single X-ray radiation exposure achieved complete tumor ablation without side effects during treatment in a mouse model. The results demonstrated that the mitochondria-targeted nanosensitizer could dramatically decrease treatment doses and greatly amplify antitumor efficacy. This strategy could potentially provide a highly efficacious and universal approach to enhance tumor radiosensitivity in future clinical cancer therapies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21535004, 91753111, 21874086, 21390411) and the Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (2018YFJH0502).

Abbreviations

- APTES

(3- aminopropyl)triethoxysilane

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- CLSM

confocal laser scanning microscopy

- CsA

cyclosporine A

- DBZTC

2-chloro-1,3-dibenzothiazolinecyclohexene

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- EDX

energy dispersive spectra

- EIPA

ethylisopropylamiloride

- FTIR

the fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IMAC

inner membrane anion channel

- MTG

Mito-Tracker Green

- MPTP

mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- O2•-

superoxide anion

- PXRD

powder X-ray diffraction

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SERs

sensitization enhancement ratios

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- TPP

4-carboxybutyl triphenylphosphonium bromide

- TiO2 (Gd) NPs

Gd-doped titania nanoparticles

- TBOT

tetrabutyl titanate

- XPS

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

- Δψm

mitochondrial membrane potential.

References

- 1.Song GS, Liang C, Chao Y, Yang K, Liu Z. Emerging nanotechnology and advanced materials for cancer radiation therapy. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1700996–1022. doi: 10.1002/adma.201700996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delaney G, Jacob S, Featherstone C, Barton M. The role of radiotherapy in cancer treatment. Cancer. 2005;104:1129–37. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song GS, Chen YY, Liang C, Yi X, Liu JJ, Sun XQ. et al. Catalase-loaded TaOx nanoshells as bio-nanoreactors combining high-Z element and enzyme delivery for enhancing radiotherapy. Adv Mater. 2016;28:7143–8. doi: 10.1002/adma.201602111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mladenov E, Magin S, Soni A, Iliakis G. DNA double-strand break repair as determinant of cellular radiosensitivity to killing and target in radiation therapy. Front Oncol. 2013;3:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang YZ, He LZ, Zeng LL, Song ZH, Li PG, Chan L. et al. Designing core-shell gold and selenium nanocomposites for cancer radiochemotherapy. ACS Nano. 2017;11:4848–58. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang SW, Li X, Chen Y, Cai XJ, Yao HL, Gao W. et al. A facile one-pot synthesis of a two-dimensional MoS2/Bi2S3 composite theranostic nanosystem for multimodality tumor imaging and therapy. Adv Mater. 2015;27:2775–82. doi: 10.1002/adma.201500870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo Z, Zhu S, Yong Y, Zhang X, Dong XH, Du JF. et al. Synthesis of BSA-coated BiOI@Bi2S3 semiconductor heterojunction nanoparticles and their applications for radio/photodynamic/photothermal synergistic therapy of tumor. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1704136–48. doi: 10.1002/adma.201704136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulin AL, Truillet C, Chouikrat R, Lux F, Frochot C, Amans D. et al. X-ray-induced singlet oxygen activation with nanoscintillator coupled porphyrins. J Phys Chem C. 2013;117:21583–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamkaew A, Chen F, Zhan YH, Majewski RL, Cai WB. Scintillating nanoparticles as energy mediators for enhanced photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano. 2016;10:3918–35. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b01401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang C, Zhao KL, Bu WB, Ni DL, Liu YY, Feng JW. et al. Marriage of scintillator and semiconductor for synchronous radiotherapy and deep photodynamic therapy with diminished oxygen dependence. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;127:1790–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song GS, Liang C, Yi X, Zhao Q, Cheng L, Yang K. et al. Perfluorocarbon-loaded hollow Bi2Se3 nanoparticles for timely supply of oxygen under near-infrared light to enhance the radiotherapy of cancer. Adv Mater. 2016;28:2716–23. doi: 10.1002/adma.201504617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Townley HE, Rapa E, Wakefield G, Dobson PJ. Nanoparticle augmented radiation treatment decreases cancer cell proliferation. Nanomedicine. 2012;8:526–36. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Townley HE, Wakefield G. Rare earth doped titania nanoparticles upregulate cellular reactive oxygen species upon X-ray irradiation. Bionanoscience. 2014;4:307–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu CYY, Xu H, Ji SL, Kwok RTK, Lam JWY, Li XL. et al. Mitochondrion-anchoring photosensitizer with aggregation-induced emission characteristics synergistically boosts the radiosensitivity of cancer cells to ionizing radiation. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1606167–76. doi: 10.1002/adma.201606167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strom E, Sathe S, Komarov PG, Chernova OB, Pavlovska I, Shyshynova I. et al. Small-molecule inhibitor of p53 binding to mitochondria protects mice from gamma radiation. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;2:474–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li N, Yu LH, Wang JB, Gao XN, Chen YY, Pan W. et al. A mitochondria-targeted nanoradiosensitizer activating reactive oxygen species burst for enhanced radiation therapy. Chem Sci. 2018;9:3159–64. doi: 10.1039/c7sc04458e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villaraza AJL, Bumb A, Brechbiel MW. Macromolecules, dendrimers, and nanomaterials in magnetic resonance imaging: the interplay between size, function, and pharmacokinetics. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2921–59. doi: 10.1021/cr900232t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AkpanB UG, Hameed H. The advancements in sol-gel method of doped-TiO2 photocatalysts. Appl Catal A Gen. 2010;375:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen HM, Wang GD, Tang W, Todd T, Zhen ZP, Tsang C. et al. Gd-encapsulated carbonaceous dots with efficient renal clearance for magnetic resonance imaging. Adv Mater. 2014;26:6761–6. doi: 10.1002/adma.201402964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farbod M, Kajbafvala M. Effect of nanoparticle surface modification on the adsorption-enhanced photocatalysis of Gd/TiO2 nanocomposite. Powder Technol. 2013;239:434–40. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu DZ, Fang PF, Liu Y, Liu Z, Liu XZ, Gao YP. et al. A facile one-pot synthesis of gadolinium doped TiO2-based nanosheets with efficient visible light-driven photocatalytic performance. J Nanopart Res. 2014;16:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghaemi B, Mashinchian O, Mousavi T, Karimi R, Kharrazi S, Amani A. Harnessing the cancer radiation therapy by lanthanide-doped zinc oxide based theranostic nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:3123–34. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zalas M, Laniecki M. Photocatalytic hydrogen generation over lanthanides-doped titania. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells. 2005;89:287–96. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu F, Feng ND, Wang Q, Xu J, Qi GD, Wang C. et al. Transfer channel of photoinduced holes on a TiO2 surface as revealed by solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance and electron spin resonance spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:10020–8. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b04877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman GS, Dohna´lek Z, Ruzycki N, Diebold U. Experimental investigation of the interaction of water and methanol with anatase-TiO2(101) J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:2788–95. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li N, Wang H, Xue M, Chang CY, Chen ZZ, Zhuo LH. et al. A highly selective and sensitive nanoprobe for detection and imaging of the superoxide anion radical in living cells. Chem Commun. 2012;48:2507–9. doi: 10.1039/c2cc16376d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen XB, Mao SS. Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications. Chem Rev. 2007;107:2891–959. doi: 10.1021/cr0500535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pathak R K, Kolishetti N, Dhar S. Targeted nanoparticles in mitochondrial medicine. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2015;7:315–29. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang LM, Li N, Pan W, Yu ZZ, Tang B. Real-time imaging of mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide and pH fluctuations in living cells using a fluorescent nanosensor. Anal Chem. 2015;87:3678–84. doi: 10.1021/ac503975x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li N, Wang MM, Gao XN, Yu ZZ, Pan W, Wang HY, Tang B. A DNA tetrahedron nanoprobe with controlled distance of dyes for multiple detection in living cells and in vivo. Anal Chem. 2017;89:6670–7. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yong Y, Cheng XJ, Bao T, Zu M, Yan L, Yin WY. et al. Tungsten sulfide quantum dots as multifunctional nanotheranostics for in vivo dual-modal image-guided photothermal/radiotherapy synergistic therapy. ACS Nano. 2015;9:12451–63. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luan MM, Yu LH, Pan W, Gao XN, Wan XY, Li N, Tang B. Visualizing breast cancer cell proliferation and invasion for assessing drug efficacy with a fluorescent nanoprobe. Anal Chem. 2017;89:10601–7. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ly JD, Grubb DR, Lawen A. The mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) in apoptosis; an update. Apoptosis. 2003;8:115–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1022945107762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson LV, Walsh ML, Chen LB. Localization of mitochondria in living cells with rhodamine 123. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:990–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aon M.A.; Cortassa, S.; Maack, O'Rourke B. Sequential opening of mitochondrial ion channels as a function of glutathione redox thiol status. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21889–900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702841200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qian H, Li F, Liu XJ, Li WR, Shi W, Liu F.-F. et al. Caspase 3-mediated stimulation of tumor cell repopulation during cancer radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2011;17:860–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu ZZ, Sun QQ, Pan W, Li N, Tang B. A Near-infrared triggered nanophotosensitizer inducing domino effect on mitochondrial reactive oxygen species burst for cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2015;9:11064–74. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b04501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang DD, Wen LW, Huang R, Wang HH, Hu XL, Xing D. Mitochondrial specific photodynamic therapy by rare-earth nanoparticles mediated near-infrared graphene quantum dots. Biomaterials. 2018;153:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luan MM, Li N, Pan W, Yang LY, Yu ZZ, Tang B. Simultaneous detection of multiple targets involved in PI3K/AKT pathway for investigating cellular migration and invasion with a multicolor fluorescence nanoprobe. Chem Commun. 2017;53:356–9. doi: 10.1039/c6cc07605j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.