Abstract

Background Disadvantaged populations, including minorities and the elderly, use patient portals less often than relatively more advantaged populations. Limited access to and experience with technology contribute to these disparities. Free access to devices, the Internet, and technical assistance may eliminate disparities in portal use.

Objective To examine predictors of frequent versus infrequent portal use among hospitalized patients who received free access to an iPad, the Internet, and technical assistance.

Materials and Methods This subgroup analysis includes 146 intervention-arm participants from a pragmatic randomized controlled trial of an inpatient portal. The participants received free access to an iPad and inpatient portal while hospitalized on medical and surgical cardiac units, together with hands-on help using them. We used logistic regression to identify characteristics predictive of frequent use.

Results More technology experience (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 5.39, p = 0.049), less severe illness (adjusted OR = 2.07, p = 0.077), and private insurance (adjusted OR = 2.25, p = 0.043) predicted frequent use, with a predictive performance (area under the curve) of 65.6%. No significant differences in age, gender, race, ethnicity, level of education, employment status, or patient activation existed between the frequent and infrequent users in bivariate analyses. Significantly more frequent users noticed medical errors during their hospital stay.

Discussion and Conclusion Portal use was not associated with several sociodemographic characteristics previously found to limit use in the inpatient setting. However, limited technology experience and high illness severity were still barriers to frequent use. Future work should explore additional strategies, such as enrolling health care proxies and improving usability, to reduce potential disparities in portal use.

Keywords: health records, patient portals, informatics, patient engagement

Background and Significance

The percentage of health care organizations offering online patient portals rose from 43% in 2013 to 92% in 2015. 1 2 3 The rapid adoption of portals reflects health care organizations' increasing focus on patient engagement, person-centered care, and shared decision making. 4 5 In 2016, a national survey found that hospital leaders view portals as the most effective tool to engage patients with their health care. 6 The federal Meaningful Use program has driven portal adoption, by incentivizing organizations to provide patients with electronic access to their health information. 7 As portals become increasingly available, more patients use them. 8 9 10 11 In the United States, the rate of self-reported portal use rose from 17% in 2014 to 28% in 2017. 12 13

The increasing popularity of portals and their potential utility to hospitalized patients has motivated some organizations to adopt inpatient portals , or patient portals accessed in the hospital setting. 14 15 16 17 18 19 Vendors now offer portals intended specifically for in-hospital use, such as MyChart Bedside from Epic Systems Corporation. 20 Institutions use inpatient portals to address patients' information needs, engage patients in decision making, facilitate patient–provider communication, improve transparency, provide health education, increase patient safety, and enable transitions of care. 14 15 Research suggests that inpatient portals may improve patient safety and satisfaction. 21 22 23 24 25 26 Inpatient portals empower patients to report safety concerns, facilitate patient recognition of errors, improve patients' perceptions of safety and quality, and fulfill patients' information needs.

Many studies report that disadvantaged populations such as racial and ethnic minorities and low income, low literacy, elderly, and disabled persons use patient portals less often, in both outpatient and inpatient settings. 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Research suggests that limited access to and experience with technology, as well as limited assistance with the portal, contribute to disparities in portal use. 27 31 37 38 39 40 41 According to the Pew Research Center, in 2018, 23% of Americans do not own a smartphone, 42 and 11% never use the Internet. 43 Disadvantaged populations experience a higher burden of disease, and relatively low portal use among disadvantaged groups may worsen existing health disparities. 41 44 As portals gain in popularity, identifying strategies to reduce disparities in use is essential, to ensure portals benefit all populations. 41

To date, interventions designed to reduce disparities in portal use include universal access policies, 44 caregiver enrollment, 37 and computer literacy training. 45 46 Intervention success is hampered by (1) difficulty reaching disadvantaged populations for enrollment and training, (2) limited technology access in disadvantaged populations, and (3) difficulty achieving scale. The inpatient setting offers unique opportunities to overcome such limitations. Hospitalized patients may be more easily reached with hands-on interventions, and represent the sickest and most vulnerable population. Because portals improve access to information, engaging hospitalized patients with portals should have far-reaching consequences such as improved patient safety and trust. 21 47

We conducted a pragmatic randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a locally developed inpatient portal delivered to hospitalized patients. 16 48 In the trial, we implemented strategies to ensure every intervention-arm participant could use the portal. Specifically, portal users received (1) free access to hospital-provided iPads and the Internet, (2) assistance in establishing their portal account, (3) basic training on how to use the portal, and (4) regular troubleshooting. In this subgroup analysis, we examine characteristics associated with frequent and infrequent portal use in the intervention arm, specifically (1) health-equity-relevant characteristics such as age, gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, health literacy, technology experience, and illness severity, (2) engagement and satisfaction with health care, and (3) perceived usefulness and ease-of-use of both the iPad and portal.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The RCT is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01970852). The protocol and primary results have been published separately. 16 48 Between March 2014 and May 2017, patients at a large urban hospital were recruited and randomized into three arms: (1) usual care, (2) iPad with general Internet access, (3) iPad with inpatient portal. In the RCT, the primary outcome was change in patient activation from baseline. Patient activation is an individual's knowledge, skills, and confidence in managing their health and health care. Secondary outcomes included (1) potential medical errors that patients noticed during their hospital stay, (2) patient satisfaction and engagement with health care, (3) perceived usefulness and ease-of-use of the iPad and portal, and (4) medical record inaccuracies that patients identified using the portal. Participants completed a baseline questionnaire to assess demographics, socioeconomic status, health literacy, patient activation, and technology experience. Three to five days later, participants completed a follow-up questionnaire to assess primary and secondary outcomes. For this paper, we conducted a retrospective subgroup analysis of participants in the third arm, hereby called portal users. The Columbia University Institutional Review Board approved the trial and all patients provided informed consent.

Intervention

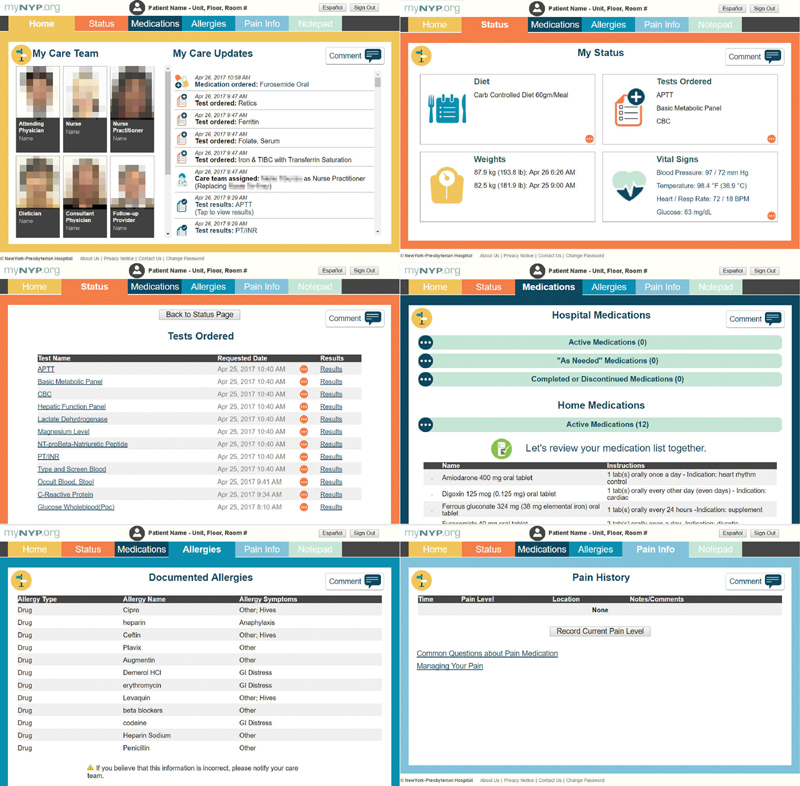

We designed and developed an inpatient portal that provides hospitalized patients with real-time access to their clinical data, sourced directly from the electronic health record. A comprehensive description of the portal has been published 16 and is summarized here. Portal features included (1) names, photos, and roles of care team members, (2) medications, (3) allergies, (4) diagnostic laboratory test orders and results, (5) current diet, (6) vital signs, (7) glucose levels, (8) weights, (9) patient-reported pain levels, (10) patient-generated messages to the portal team and hospital staff, (11) written and video educational materials on medications and tests, (12) portal navigation tutorials, and (13) Spanish translation ( Fig. 1 ). User actions were recorded in a detailed system use log.

Fig. 1.

Screenshots of the inpatient portal.

Participants

Participants included adult patients aged 18 years or older who spoke English or Spanish, admitted to one of two medical and surgical cardiac units at an urban academic medical center. We excluded patients with a Mini Mental Status Examination score less than 9, patients placed in contact isolation, patients involved in another research study, patients unable to provide written informed consent, and patients already admitted for more than 2 weeks. The exclusion criteria were limited to improve generalizability.

Recruitment

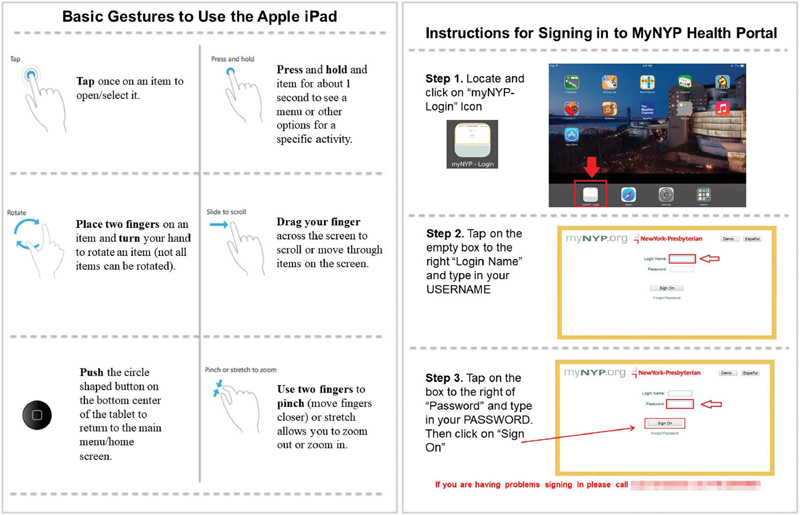

The research coordinators identified new admissions from the electronic health record, confirmed eligibility, obtained written informed consent, and administered the questionnaires. The coordinators enrolled users in the portal system, and provided their unique username and password. Each intervention-arm participant underwent a brief training session to familiarize them with the iPad and portal as appropriate to their level of technology experience. Training included basic iPad gestures (tapping, scrolling, and zooming), signing into the portal, and an overview of portal features. Portal users also received a handout with instructions ( Fig. 2 ). The coordinators visited participants daily to address potential issues with the iPad, Internet, or portal, such as difficulty signing in.

Fig. 2.

Technology assistance handout.

Measures and Data Sources

The baseline and follow-up questionnaires have been previously described. 16 To assess health literacy, we used Chew and colleagues' health literacy screening questions. 49 To assess patient activation, we used the 13-item Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13). 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 Our team has previously validated the PAM-13 in the inpatient setting. 57 To assess patient-identified medical errors, we asked patients to describe and categorize errors they noticed while enrolled in the trial. To assess patient satisfaction, patient engagement, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease-of-use, we adapted the Telemedicine Satisfaction and Usefulness Questionnaire. 58

We obtained information on unit and hospital demographics, insurance type, mailing address, diagnoses, length of hospital stay, All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group (APR-DRG) Severity of Illness, 59 and APR-DRG Risk of Mortality 60 from our institution's clinical data warehouse. APR-DRG Severity of Illness is defined as “the extent of organ system loss of function or physiologic decompensation,” and Risk of Mortality is defined as “the likelihood of dying.” The APR-DRG categorizes both Severity of Illness and Risk of Mortality as minor (level 1), moderate (level 2), major (level 3), or extreme (level 4). We used diagnosis information to calculate each participant's Charlson Comorbidity Index, 61 which predicts 10-year mortality. We geocoded participant mailing addresses to obtain their census tracts, which enabled linkage with the 2016 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Social Vulnerability Index, 62 an overall score for census tracts based on social determinants. We excluded post office boxes since these addresses may not reflect the actual residence.

Statistical Analyses

To categorize portal use as frequent or infrequent for each participant, a composite use variable was utilized. 63 We utilized the composite variable to capture multiple aspects of patients' portal use and provide the best overall assessment. Specifically, participants' portal use was classified as frequent if it exceeded thresholds in four out of four metrics: (1) total number of logins, (2) logins per day, (3) total minutes using the portal, and (4) minutes using the portal per day. The thresholds were (1) two or more logins total, (2) one or more logins per day on average, (3) 50 minutes using the portal total, and (4) 20 minutes using the portal per day on average. We determined thresholds based on logical breaks in the data, since descriptive analyses found bimodal or multimodal distributions for all four metrics.

After portal users were classified into subgroups, we conducted bivariate analyses to assess whether each baseline characteristic or outcome differed between frequent and infrequent users. Nominal variables were compared using chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests with Monte Carlo approximation, while ordinal and numerical variables were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

We further used multivariable binomial logistic regression to examine the relationship between baseline characteristics and portal use ( frequent vs. infrequent ). First, we constructed a preliminary main effect model using all independent variables where p < 0.25 in bivariate analyses. 64 Then, we used the R package glmulti 65 to perform exhaustive automated model selection using Akaike information criteria (AIC) for model comparison. glmulti builds all possible unique models and selects the highest quality one as per AIC to reward goodness-of-fit, penalize overfitting, and avoid collinearity. We performed preliminary experiments testing interaction terms and regularization approaches, but ultimately excluded them to prevent overfitting and support parsimony in model selection. We assessed predictive ability using area under the ROC curve (AUC), calculated by averaging results from 1,000 random five-fold cross-validation cycles to improve the metric's stability. All analyses were conducted in R version 3.3.3 and SAS version 9.4.

Results

Of the 478 individuals assessed for eligibility, 23 did not meet the inclusion criteria and 1 declined to participate. We enrolled the remaining 454 individuals, 155 of whom were randomized to the portal arm. Nine portal users did not complete the trial, including 4 who withdrew consent, 3 deceased, and 2 lost to follow-up. Of the 146 portal users who completed the trial, 93 (63.7%) met the criteria for frequent use of the inpatient portal, and the remaining 53 (36.3%) had infrequent use. Among infrequent users, 25 (47%) never used the portal. A comparison of baseline characteristics between frequent and infrequent user groups is presented in Table 1 . Overall, portal users had an average age of 56 years (range: 22–89). Portal users were 16.0% Black, 22.1% Latino, and 8.3% preferred Spanish as a primary language. Portal users were representative of our institution's hospitalized population based on gender, race, and ethnicity, but were slightly younger ( Supplementary Table 1 , available in the online version).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Variable | All users, n = 146 | Subgroup analysis | p -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrequent use, n = 53 | Frequent use, n = 93 | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (mean, SD) | 56.3 ± 15.2 | 58.6 ± 16.6 | 55.0 ± 14.3 | 0.140 |

| Female sex ( n , %) | 59 (40.4) | 18 (34.0) | 41 (44.1) | 0.231 |

| Race ( n , %) | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4 (2.8) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (2.2) | 0.064 |

| Black or African American | 23 (16.0) | 13 (24.5) | 10 (11.0) | |

| Multi-race | 4 (2.8) | 3 (5.7) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Other | 29 (20.1) | 8 (15.1) | 21 (23.1) | |

| White | 84 (58.3) | 27 (50.9) | 57 (62.6) | |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin ( n , %) | 32 (22.1) | 10 (18.9) | 22 (23.9) | 0.481 |

| Country of origin ( n , %) | ||||

| Dominican Republic or Puerto Rico | 10 (6.9) | 3 (5.7) | 7 (7.6) | 0.183 |

| United States | 108 (74.5) | 36 (67.9) | 72 (78.3) | |

| Other | 27 (18.6) | 14 (26.4) | 13 (14.1) | |

| Spanish as preferred language ( n , %) | 12 (8.3) | 5 (9.6) | 7 (7.6) | 0.757 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Social vulnerability index (mean, SD) | 0.54 ± 0.32 | 0.58 ± 0.33 | 0.51 ± 0.31 | 0.222 |

| Education ( n , %) | ||||

| < High school graduate or GED | 12 (8.3) | 4 (7.5) | 8 (8.7) | 0.419 |

| High school graduate or GED | 24 (16.6) | 8 (15.1) | 16 (17.4) | |

| Associate's degree, technical school, some college | 53 (36.6) | 24 (45.3) | 29 (31.5) | |

| College graduate or higher | 56 (38.6) | 17 (32.1) | 39 (42.4) | |

| Employment status ( n , %) | ||||

| Employed | 79 (55.6) | 23 (44.2) | 56 (62.2) | 0.054 |

| Unemployed | 29 (20.4) | 11 (21.2) | 18 (20.0) | |

| Retired | 34 (23.9) | 18 (34.6) | 16 (17.8) | |

| Insurance type ( n , %) | ||||

| Public (Medicare or Medicaid) only | 28 (19.3) | 13 (25.0) | 15 (16.1) | 0.013 a |

| Public plus private supplement | 51 (35.2) | 24 (46.2) | 27 (29.0) | |

| Private or commercial only | 54 (37.2) | 14 (26.9) | 40 (43.0) | |

| Self-pay b | 12 (8.3) | 1 (1.9) | 11 (11.8) | |

| Annual household income ( n , %) | ||||

| Less than 15,000 USD | 11 (14.5) | 2 (8.3) | 9 (17.3) | 0.010 a |

| 15,000–50,000 USD | 17 (22.4) | 11 (45.8) | 6 (11.5) | |

| 50,000–100,000 USD | 19 (25.0) | 5 (20.8%) | 14 (26.9) | |

| More than 100,000 USD | 29 (38.2) | 6 (25.0) | 23 (44.2) | |

| Inadequate health literacy ( n , %) | 55 (37.7) | 22 (41.5) | 33 (35.5) | 0.470 |

| Technology experience | ||||

| Can access desktop, laptop, or tablet at home ( n , %) | 136 (93.2) | 48 (90.6) | 88 (94.6) | 0.497 |

| Can access the Internet at home ( n , %) | 133 (91.1) | 42 (79.2) | 91 (97.8) | <0.001 a |

| Daily Internet use in past 30 days ( n , %) | ||||

| <1 hour | 41 (28.1) | 18 (34.0) | 23 (24.7) | 0.312 |

| 1–3 hours | 47 (32.2) | 18 (34.0) | 29 (31.2) | |

| >3 hours | 58 (39.7) | 17 (32.1) | 41 (44.1) | |

| Has email address ( n , %) | 128 (87.7) | 41 (77.4) | 87 (93.5) | 0.004 a |

| Looks up health information online ( n , %) | 121 (82.9) | 42 (79.2) | 79 (84.9) | 0.379 |

| Illness severity | ||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (mean, SD) | 2.4 ± 2.0 | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 2.1 ± 1.9 | 0.036 a |

| Severity of Illness level (mean, SD) | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 0.020 a |

| Risk of Mortality level (mean, SD) | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 0.028 a |

| Length of hospital stay, days (mean, SD) | 11.9 ± 14.7 | 14.7 ± 14.7 | 10.4 ± 14.5 | 0.005 a |

| Patient activation | ||||

| PAM score, pre (mean, SD) | 69.9 ± 14.6 | 71.7 ± 14.6 | 68.9 ± 14.7 | 0.306 |

Abbreviations: GED, General Education Diploma; n , number; PAM, Patient Activation Measure; SD, standard deviation; USD, United States dollars.

Note: Categorical variables reported as n (%), and p -values calculated using chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests with Monte Carlo approximation. Continuous variables reported as mean ± SD, and p -values calculated using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Percentages exclude missing data.

Significant at p = 0.05.

In this clinical setting, “self-pay” reflects high-income patients who pay out-of-pocket for elective care.

No significant differences in age, gender, race, ethnicity, level of education, employment status, or baseline patient activation existed between the frequent and infrequent users. As shown in Table 1 , frequent use was associated with more technology experience (indicated by Internet access at home and having an email address), higher socioeconomic status (indicated by insurance type and household income), and less severe illness (as measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index, Severity of Illness level, and Risk of Mortality level).

Insurance type, Internet access at home, and Severity of Illness level were included in the multivariable logistic regression model ( Table 2 ), reflecting portal users' socioeconomic status, technology experience, and illness severity, respectively. Predictive performance (AUC) for the model was 65.6%, indicating moderate predictive ability for frequent versus infrequent portal use.

Table 2. Predictors of frequent acute care portal use .

| Variable | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p -Value |

|---|---|---|

| Private insurance or self-pay (vs. public) | 2.25 (1.03–5.02) | 0.043 |

| Can access the Internet at home (vs. cannot) | 5.39 (1.15–38.94) | 0.049 |

| Severity of illness level 1 or 2 (vs. 3 or 4) | 2.07 (0.93–4.78) | 0.077 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Note: We included only complete cases in our analysis, meaning we excluded 15 out of 146 portal users due to missing data values ( n = 131, 47 infrequent users and 84 frequent users).

An exploratory analysis of outcomes from the RCT, comparing frequent and infrequent users, is presented in Table 3 . No significant differences in patient activation, satisfaction, and engagement existed between frequent and infrequent users. A significantly greater percentage of frequent users reported using the iPad to look up health information online (97 vs. 76%; p < 0.001).

Table 3. Outcomes.

| Variable | All users, n = 146 | Subgroup analysis | p -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrequent use, n = 53 | Frequent use, n = 93 | |||

| Patient activation | ||||

| PAM score, post | 74.3 ± 16.0 | 74.8 ± 16.5 | 74.0 ± 15.8 | 0.789 |

| PAM score, pre–post difference | 4.4 ± 14.4 | 3.2 ± 15.9 | 5.1 ± 13.6 | 0.977 |

| PAM score, pre–post difference > 3 a | 70 (48.3%) | 26 (50.0%) | 44 (47.3%) | 0.756 |

| Medical errors | ||||

| I noticed medical errors while hospitalized | 21 (15.9%) | 2 (4.4%) | 19 (21.8%) | 0.010 b |

| I noticed inaccurate information in my record | 20 (16.5%) | 3 (8.6%) | 17 (19.8%) | 0.133 |

| If yes, I reported the inaccuracy | 7 (41.2%) | 1 (50.0%) | 6 (40.0%) | 1.000 |

| If yes, the inaccuracy was amended | 3 (60.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 0.400 |

| Patient satisfaction and engagement with care | ||||

| Patient satisfaction and engagement with care | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | – |

| Perceived usefulness and ease-of-use of iPad | ||||

| I used the iPad to … | ||||

| access my email | 20 (14.8%) | 5 (11.1%) | 15 (16.7%) | 0.392 |

| entertain myself | 92 (68.1%) | 30 (66.7%) | 62 (68.9%) | 0.794 |

| look up health information online | 121 (89.6%) | 34 (75.6%) | 87 (96.7%) | <0.001 b |

| The iPad is easy to use | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | – |

| Perceived usefulness and ease-of-use of portal | ||||

| The portal is easy to use | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | – |

| The portal made it easier to contact my care team | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 3.2 ± 1.2 | 0.411 |

| I entered questions or comments into my portal | 32 (26.4%) | 7 (20.0%) | 25 (29.1%) | 0.305 |

Abbreviations: n , number; PAM, Patient Activation Measure.

Note: Categorical variables reported as n (%), and p -values calculated using chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests with Monte Carlo approximation. Continuous variables reported as mean ± SD, and p -values calculated using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Scores based on questionnaires with Likert-type rating scales (satisfaction, ease-of-use) reported as numbers between 1 and 5. Percentages exclude missing data.

Studies suggest a pre–post difference greater than 3 in the PAM score is clinically significant.

Significant at p = 0.05.

A greater percentage of frequent users noticed potential medical errors during their hospital stay (22 vs. 4%; p = 0.010). About half (51%) of potential medical errors related to medication dosage or administration. Other potential errors related to laboratory tests or procedures (21%), pain control (9%), diet (8%), allergies (6%), diagnosis (<2%), hospital-acquired infections (<2%), and sanitation (<2%). A greater percentage of frequent users noticed inaccurate information in their medical record (20 vs. 9%, p = 0.133), although the difference lacked statistical significance in this trial. Overall, only 41% of portal users who noticed inaccurate information reported it to their health care provider.

Discussion

Although hospitalized patients experience high information needs, illness severity and stress due to hospitalization may obstruct their use of an inpatient portal. On the other hand, the hospital setting offers unique opportunities to promote portal use. Hospitals can offer free devices and Internet to inpatients, help set up portal accounts, and teach patients to use the portal. Such interventions may offset the barriers that contribute to disparities in portal use, in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Under the technology access and assistance conditions of our pragmatic RCT, many expected disparities were not evident. Specifically, age, gender, race, ethnicity, level of education, employment status, and patient activation were not associated with frequent use. However, more severe illness, preexisting limited technology experience, and public insurance were significantly associated with infrequent use, despite technology access and assistance.

In the outpatient setting, research suggests that low technology literacy, alongside limited computer and Internet access, impacts outpatients' adoption of portals as well as their continued use. 31 38 39 40 Currently, many patients access inpatient portals through hospital-provided devices, as in this RCT. However, hospital-provided devices require maintenance and disinfection, prompting some organizations to consider “bring your own device” (BYOD) options. 14 Unfortunately, BYOD may exacerbate disparities in portal use, by adding the additional barriers of computer and Internet access. Therefore, organizations should consider maintaining hospital-provided device programs.

The relationship between illness severity and portal use is more complex. 31 Some studies suggest that having multiple comorbidities is associated with increased portal adoption, 66 67 while others indicate that poorer overall health is associated with decreased portal adoption. 67 One hypothesis is that patients use portals more as their health condition worsens, until they become too sick to use it. At that point, their use declines. We studied an overall sicker population, hospitalized patients, and found that use declines as illness severity increases. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that the relationship between illness severity and portal use is parabolic.

Since disparities in use of inpatient portals exist despite technology access and assistance, health care organizations must consider additional strategies that promote equal access. One possible strategy is enrolling caregivers, such as surrogate decision makers or health care proxies. Caregivers may help patients with low technology literacy or severe illness access their information. This strategy may be of limited use among the most severely socioeconomically disadvantaged patients, whose family and caregivers may themselves have limited technology literacy. An alternative strategy is additional in-hospital training on portal use. The hospital setting offers an opportunity for patients to develop familiarity with the portal software while assistance is available. New approaches to improving usability may help reduce training needs. 68 69

Despite the well-documented evidence for disparities in outpatient portal use, 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 fewer studies have investigated potential disparities in inpatient portal use. 34 35 36 However, this study and the existing literature indicate that disparities in use occur with inpatient portals as with outpatient ones. Given the development of products like MyChart Bedside and HealtheLife, both available in Spanish, inpatient portal availability is expected to increase rapidly in the coming years. Implementing strategies such as universal access policies, 44 hospital-provided device programs, and technical assistance alongside inpatient portals will be critical to reduce disparities in use. In this study, 93 (63.7%) patients demonstrated frequent use, meaning they logged on for over 20 minutes per day on average. These data suggest that many hospitalized patients will use portals given the opportunity, and organizations should explore strategies to ensure all populations receive and benefit from this opportunity.

Significantly more frequent users noticed medical errors during their hospital stay (22 vs. 4%; p = 0.01). It is unclear whether the portal helped users identify medical errors, or whether noticing errors prompted portal use, or whether a third variable explains both noticing medical errors and portal use. As with medical errors, frequent users were more likely to notice inaccuracies in their medical record (20 vs. 9%, p = 0.133), although the difference lacked statistical significance. Recent research from OpenNotes found that 23% of patients who reviewed their doctor's notes identified potential safety concerns. 70 Inpatient portal developers should explore methods to engage patients as partners in improving safety, and consider creating explicit protocols for reporting safety concerns through patient portals.

We did not find significant differences in patient activation between groups, although recent research suggests that standardized administration of the PAM is challenging, especially within our population. 71 Previous research on whether high patient activation correlates with portal use is mixed. 72 73 Hibbard and Greene, developers of the Patient Activation Measure, have reported that patients with high activation levels use portals more often. 73 However, a smaller study among outpatients at our center failed to find an association between PAM score and portal use, though it did find the expected associations with education and socioeconomic status. 72 Future research should further investigate how patient activation interacts with portal use.

Limitations

We conducted this trial at an urban academic medical center with an advanced informatics infrastructure, and findings may not generalize to other health care settings. Additional barriers to inpatient portal use could include (1) literacy factors such as numeracy or text literacy, (2) portal factors such as usability, utility, and cost, (3) attitudinal factors such as motivation or concerns about privacy, and (4) patient–provider relationship factors such as communication and trust. 31 Future work should explore these potential barriers and their impact on inpatient portal use. Our study excluded visually, physically, and cognitively impaired patients, despite evidence that these patient populations experience a higher burden of disease. Future work should explore strategies to engage persons with disabilities in inpatient portals. Finally, creating standardized methods to assess composite portal use remains an urgent problem, especially since individual metrics do not reflect actual usage well. Standardized methods could ensure better comparability between studies of portal use. This study relied on a simple, transparent, and binary composite use variable; however, innumerable different composite variables could be constructed.

Conclusion

We conducted a subgroup analysis of frequent versus i nfrequent inpatient portal users from an RCT. The trial provided free technology access and assistance, and subsequently many expected health-equity-related disparities were not observed. However, technology access and assistance did not eliminate disparities based on illness severity and preexisting technology experience. Future work should explore strategies, such as enrolling health care proxies and improving usability, to reduce potential disparities in use of inpatient portals.

Multiple Choice Questions

-

Free technology access and technical assistance may ameliorate which previously identified disparity in inpatient portal use?

Age.

Technology experience.

Illness severity.

Insurance status.

Correct Answer: The correct answer option is option a, age. In this study, we found evidence that free technology access and technical assistance may ameliorate disparities in inpatient portal use by age. However, disparities in preexisting technology experience, illness severity, and insurance status remained.

-

Which strategies may ameliorate health-equity-related disparities in patient portal use?

Free technology access and technical assistance.

Better access policies such as opt-out enrollment.

Enrollment of caregivers and health care proxies.

All of the above.

Correct Answer: The correct answer is option d, all of the above. In this study, we demonstrate that free technology access and technical assistance ameliorate health-equity-related disparities in patient portal use. Early evidence also indicates that opt-out enrollment policies, as well as deliberate efforts to engage caregivers, may reduce disparities in use.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Evan Sholle for providing geocoding expertise and code, as well as Abdul Tariq and Raymond Grossman for providing statistical expertise.

Funding Statement

Funding This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS21816, PI: Vawdrey), the National Library of Medicine (T15LM007079), and the National Institute of Nursing Research (K99NR016275, PI: Masterson Creber).

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Protection of Human and Animal Subjects

This study was performed in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, and was reviewed by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.American Hospital Association.Individuals' ability to electronically access their hospital medical records, perform key tasks is growing. 2016Available at:http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/16jul-tw-healthIT.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2018

- 2.Adler-Milstein J, DesRoches C M, Kralovec P et al. Electronic health record adoption in us hospitals: progress continues, but challenges persist. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(12):2174–2180. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler-Milstein J, DesRoches C M, Furukawa M F et al. More than half of US hospitals have at least a basic EHR, but stage 2 criteria remain challenging for most. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(09):1664–1671. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(05):681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berwick D M. Era 3 for medicine and health care. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1329–1330. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volpp K G, Mohta N S.Patient engagement survey: far to go to meaningful participation. NEJM Catal;2016. Available at:http://catalyst.nejm.org/patient-engagement-initiatives-survey-meaningful-participation/. Accessed December 12, 2018

- 7.2014 Edition EHR Certification Criteria Grid Mapped to Meaningful Use Stage 2. Available at:https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/2014editionehrcertificationcriteria_mustage2.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2018

- 8.Ancker J S, Silver M, Kaushal R. Rapid growth in use of personal health records in New York, 2012–2013. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(06):850–854. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2792-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Undem T.Consumers and health information technology: a national survey. Oakland, CA; 2010Available at:http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Consumers+and+Health+Information+Technology+:+A+National+Survey#0. Accessed December 12, 2018

- 10.Halamka J D, Mandl K D, Tang P C. Early experiences with personal health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(01):1–7. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ancker J S, Hafeez B, Kaushal R. Socioeconomic disparities in adoption of personal health records over time. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(08):539–540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel V, Barker W, Siminerio E.ONC Data Brief No. 30: trends in consumer access and use of electronic health information 2015. Available at:https://dashboard.healthit.gov/evaluations/data-briefs/trends-consumer-access-use-electronic-health-information.php. Accessed December 12, 2018

- 13.Patel V, Johnson C.ONC Data Brief No. 40: individuals' use of online medical records and technology for health needs. 2017Available at:https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/page/2018-03/HINTS-2017-Consumer-Data-Brief-3.21.18.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2018

- 14.Collins S A, Rozenblum R, Leung W Yet al. Acute care patient portals: a qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives on current practices J Am Med Inform Assoc 201724(e1):e9–e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman L V, Choi S W, Collins S et al. Implementation of acute care patient portals: recommendations on utility and use from six early adopters. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(04):370–379. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masterson Creber R, Prey J, Ryan B et al. Engaging hospitalized patients in clinical care: study protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;47:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Runaas L, Hanauer D, Maher M et al. BMT roadmap: a user-centered design health information technology tool to promote patient-centered care in pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(05):813–819. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.01.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAlearney A S, Sieck C J, Hefner J L et al. High touch and high tech (HT2) proposal: transforming patient engagement throughout the continuum of care by engaging patients with portal technology at the bedside. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(04):e221. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Leary K J, Lohman M E, Culver E, Killarney A, Randy Smith G, Jr, Liebovitz D M. The effect of tablet computers with a mobile patient portal application on hospitalized patients' knowledge and activation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(01):159–165. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winstanley E L, Burtchin M, Zhang Y et al. Inpatient experiences with MyChart Bedside. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23(08):691–693. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2016.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prey J E, Restaino S, Vawdrey D K. Providing hospital patients with access to their medical records. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:1884–1893. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vawdrey D K, Wilcox L G, Collins S A et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1428–1435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caligtan C A, Carroll D L, Hurley A C, Gersh-Zaremski R, Dykes P C. Bedside information technology to support patient-centered care. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(07):442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly M M, Hoonakker P LT, Dean S M. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(01):153–161. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larson C O, Nelson E C, Gustafson D, Batalden P B. The relationship between meeting patients' information needs and their satisfaction with hospital care and general health status outcomes. Int J Qual Heal Care. 1996;8(05):447–456. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/8.5.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skeels M, Tan D S. Identifying opportunities for inpatient-centric technology. Proc ACM IHI. 2010:580–589. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ancker J S, Barrón Y, Rockoff M L et al. Use of an electronic patient portal among disadvantaged populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1117–1123. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1749-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarkar U, Karter A J, Liu J Y et al. The literacy divide: health literacy and the use of an internet-based patient portal in an integrated health system-results from the diabetes study of northern California (DISTANCE) J Health Commun. 2010;15 02:183–196. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamin C K, Emani S, Williams D H et al. The digital divide in adoption and use of a personal health record. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(06):568–574. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goel M S, Brown T L, Williams A, Cooper A J, Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker D W. Patient reported barriers to enrolling in a patient portal. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18 01:i8–i12. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Showell C. Barriers to the use of personal health records by patients: a structured review. Peer J. 2017;5:e3268. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wildenbos G A, Peute L, Jaspers M. Facilitators and barriers of electronic health record patient portal adoption by older adults: a literature study. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;235:308–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran C R. Patient portals and patient engagement: a state of the science review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(06):e148. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson J R, Davis S E, Cronin R M, Jackson G P. Use of a patient portal during hospital admissions to surgical services. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2017;2016:1967–1976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aljabri D, Dumitrascu A, Burton M C et al. Patient portal adoption and use by hospitalized cancer patients: a retrospective study of its impact on adverse events, utilization, and patient satisfaction. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2018;18(01):70. doi: 10.1186/s12911-018-0644-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis S E, Osborn C Y, Kripalani S, Goggins K M, Jackson G P. Health literacy, education levels, and patient portal usage during hospitalizations. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2015;2015:1871–1880. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolff J L, Berger A, Clarke D et al. Patients, care partners, and shared access to the patient portal: online practices at an integrated health system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(06):1150–1158. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lober W B, Zierler B, Herbaugh A et al. Barriers to the use of a personal health record by an elderly population. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006;2006:514–518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hilton J F, Barkoff L, Chang O et al. A cross-sectional study of barriers to personal health record use among patients attending a safety-net clinic. PLoS One. 2012;7(02):e31888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butler J M, Carter M, Hayden C et al. Understanding adoption of a personal health record in rural health care clinics: revealing barriers and facilitators of adoption including attributions about potential patient portal users and self-reported characteristics of early adopting users. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2013;2013:152–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veinot T C, Mitchell H, Ancker J S. Good intentions are not enough: how informatics interventions can worsen inequality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(08):1080–1088. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pew Research Center. 2018 Mobile Fact Sheet. 2018Available at:http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed August 20, 2018

- 43.Pew Research Center. 2018 Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet.2018. Available at:http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/. Accessed July 20, 2018

- 44.Ancker J S, Nosal S, Hauser D, Way C, Calman N. Access policy and the digital divide in patient access to medical records. Health Policy Technol. 2017;6(01):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Casey I. The effect of education on portal personal health record use. Online J Nurs Inform. 2016;20(02):9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McInnes D K, Solomon J L, Shimada S L et al. Development and evaluation of an internet and personal health record training program for low-income patients with HIV or hepatitis C. Med Care. 2013;51(03) 01:S62–S66. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827808bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woollen J, Prey J, Wilcox L et al. Patient experiences using an inpatient personal health record. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(02):446–460. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2015-10-RA-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Masterson Creber R M, Grossman L V, Ryan Bet al. Engaging hospitalized patients with personalized health information: a randomized trial of an acute care patient portalJ Am Med Inform Assoc2018. Doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Chew L D, Bradley K A, Boyko E J. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(08):588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hibbard J H, Mahoney E R, Stock R, Tusler M. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(04):1443–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hibbard J H, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(02):207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hibbard J H, Mahoney E R, Stockard J, Tusler M.Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure Health Serv Res 200540(6, Pt 1):1918–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hibbard J H.Using systematic measurement to target consumer activation strategies Med Care Res Rev 200966(1, Suppl)9S–27S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fowles J B, Terry P, Xi M, Hibbard J, Bloom C T, Harvey L. Measuring self-management of patients' and employees' health: further validation of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) based on its relation to employee characteristics. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(01):116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greene J, Hibbard J H. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(05):520–526. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1931-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hibbard J H, Greene J, Tusler M. Improving the outcomes of disease management by tailoring care to the patient's level of activation. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(06):353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prey J E, Qian M, Restaino S et al. Reliability and validity of the patient activation measure in hospitalized patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):2026–2033. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bakken S, Grullon-Figueroa L, Izquierdo R et al. Development, validation, and use of English and Spanish versions of the telemedicine satisfaction and usefulness questionnaire. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(06):660–667. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Horn S D, Horn R A, Sharkey P D.The Severity of Illness Index as a severity adjustment to diagnosis-related groups Health Care Financ Rev 1984;(Suppl):33–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Averill R F, Goldfield N I, Muldoon J, Steinbeck B A, Grant T M. A closer look at all-patient refined DRGs. J AHIMA. 2002;73(01):46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Charlson M E, Pompei P, Ales K L, MacKenzie C R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(05):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.The Social Vulnerability Index (SVI): SVI Data and Tools Download. 2018Available at:https://svi.cdc.gov/data-and-tools-download.html. Accessed July 17, 2018

- 63.Song M-K, Lin F-C, Ward S E, Fine J P. Composite variables: when and how. Nurs Res. 2013;62(01):45–49. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182741948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bursac Z, Gauss C H, Williams D K, Hosmer D W. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Calcagno V, De Mazancourt C. glmulti : An R Package for Easy Automated Model Selection with (Generalized) Linear Models. J Stat Softw. 2010;34(12):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roblin D W, Houston T K, II, Allison J J, Joski P J, Becker E R. Disparities in use of a personal health record in a managed care organization. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(05):683–689. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Emani S, Yamin C K, Peters E et al. Patient perceptions of a personal health record: a test of the diffusion of innovation model. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(06):e150. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ali S B, Romero J, Morrison K, Hafeez B, Ancker J S. Focus section health IT usability: applying a task-technology fit model to adapt an electronic patient portal for patient work. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(01):174–184. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1632396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walker D M, Menser T, Yen P-Y, McAlearney A S. Optimizing the user experience: identifying opportunities to improve use of an inpatient portal. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(01):105–113. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1621732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bell S K, Mejilla R, Anselmo M et al. When doctors share visit notes with patients: a study of patient and doctor perceptions of documentation errors, safety opportunities and the patient-doctor relationship. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(04):262–270. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chew S, Brewster L, Tarrant C, Martin G, Armstrong N. Fidelity or flexibility: an ethnographic study of the implementation and use of the Patient Activation Measure. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(05):932–937. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ancker J S, Osorio S N, Cheriff A, Cole C L, Silver M, Kaushal R. Patient activation and use of an electronic patient portal. Inform Health Soc Care. 2015;40(03):254–266. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2014.908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hibbard J H, Greene J. Who are we reaching through the patient portal: engaging the already engaged? Int J Pers Cent Med. 2011;1(04):788–792. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.